Abstract

Tropical marine low cloud feedback is key to the uncertainty in climate sensitivity, and it depends on the warming pattern of sea surface temperatures (SSTs). Here, we empirically constrain this feedback in two major low cloud regions, the tropical Pacific and Atlantic, using interannual variability. Low cloud sensitivities to local SST and to remote SST, represented by lower-troposphere temperature, are poorly captured in many models of the latest global climate model ensemble, especially in the less-studied tropical Atlantic. The Atlantic favors large positive cloud feedback that appears difficult to reconcile with the Pacific—we apply a Pareto optimization approach to elucidate trade-offs between the conflicting observational constraints. Examining ~200,000 possible combinations of model subensembles, this multi-objective observational constraint narrows the cloud feedback uncertainty among climate models, nearly eliminates the possibility of a negative tropical shortwave cloud feedback in CO2-induced warming, and suggests a 71% increase in the tropical shortwave cloud feedback.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tropical marine low clouds cool the Earth by reflecting ~ 100 Wm−2 of insolation locally1. They have also been a long-standing major contributor to the uncertainty in climate feedbacks and climate sensitivity2,3,4,5. One approach to narrowing the uncertainty in the marine low cloud feedback is through emergent constraints which associate the long-term cloud feedback with some observable variables across a model ensemble6. However, emergent constraints depend on the relationships of future projection and current climate in a specific model ensemble7. For instance, some cloud-feedback emergent constraints developed from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) fail in the latest phase, i.e., CMIP68. Here we instead develop a priori constraints that do not rely on a specific model ensemble.

Recent observational and modeling studies show a clear dependence of tropical marine low cloud feedback on the warming pattern of sea surface temperatures (SSTs), i.e., the pattern effect9,10,11,12,13. The underlying physics is associated with the weak horizontal temperature gradient (WTG) effects in the tropical free troposphere14,15,16. When SST in the ascent area rises, the tropical free troposphere warms over large regions through deep convection and gravity wave propagation17. The free-tropospheric warming tends to strengthen the capping inversion of the stratocumulus layer over cold ocean regions, which favors increases in low cloud fraction (LCF)18,19,20. By contrast, when the SST rises locally in the marine low cloud region, LCF decreases because of a weakened inversion and additional moisture21,22,23,24. This dependence leads to a varying feedback parameter during long-term CO2-induced warming16,25,26,27.

The SST pattern effect has been explicitly or implicitly considered in some cloud feedback constraints via cloud controlling factors (CCF) measuring lower-tropospheric stability (LTS28,) or the estimated inversion strength (EIS21,28,29,30,31,). However, EIS blends the signal of local SST and the free-troposphere temperature controlled by ascent areas, which complicates the attribution of local versus remote cloud feedbacks.

In this study, we aim to exploit regional information in climate model simulation of the two major stratocumulus regions — the tropical Pacific and Atlantic — compared to observations. We examine some well-known CCFs, including SST, EIS, humidity, subsidence, and free-troposphere temperature from satellite observations, atmospheric reanalysis and CMIP6 historic experiments, and find substantial differences between the physics in two regions. Instead of assigning arbitrary weighting to the two regions, we apply a multi-objective optimization approach based on Pareto optimality to assess the model performance against the observed sensitivity of shortwave cloud radiative effect (SWCRE) to selected CCFs. This approach allows us to objectively down-weight models that do poorly against observations in both regions while retaining those that perform well in a Pareto-optimal sense among multiple observational constraints. We combine this evaluation with a Bayesian approach to derive an a priori constraint of the long-term tropical shortwave cloud feedback (SWCF) that does not rely on a specific model ensemble from the models’ quadrupled CO2 warming experiments. Finally, we compare results to traditional emergent constraints that tend to encounter incompatibility among multiple objectives.

Results

Identification of cloud controlling factors related to local and remote warming

Satellite observations show that the tropical Southeastern Pacific (SEPac) and the tropical Southeastern Atlantic (SEAtl) are the two largest marine stratocumulus regions on Earth (Supplementary Fig. 132). In both regions, the LCF decreases when the local SST rises while it increases when the tropical ascent area SST (defined in Methods) rises. As marine stratocumulus clouds strongly reflect sunlight, SWCRE changes accordingly with these respective SST measures, i.e., a greater cooling effect when LCF is greater.

We decompose the observed interannual cloud sensitivities to local and ascent area SST into different CCFs: local SST, lower-troposphere temperature at 700 mb (T700), subsidence rate at 500 mb (\({\omega }_{500}\)) and relative humidity of the boundary layer (925 mb, RH925) and the lower free troposphere (700 mb, RH700). Although we do not explicitly include EIS as an independent CCF in the multivariate linear regression analysis, the relevant information can be derived from the temperature and humidity variables. Despite the differences in the magnitudes, both stratocumulus regions show similar contributions from the selected CCFs (Fig. 1). Obviously, the cloud sensitivity to local SST is predominantly contributed by local SST as a CCF. Regarding the sensitivity to ascent area SST, the contribution from T700 accounts for the majority while RH700 plays the second largest yet statistically insignificant role and partially compensates for the T700 effect. This result is consistent with a positive correlation in T700 anomalies between the two stratocumulus regions and the ascent area mean SST (Fig. 1c), and a higher T700 tends to favor more low clouds by strengthening the capping inversion. Therefore, local SST and T700 can be chosen as a minimal set of CCFs that represent the low cloud changes due to a patterned SST variation in cold marine stratocumulus regions and warm ascent regions.

Contributions from CCFs to the sensitivities of (a) low cloud fraction (LCF) or (b) shortwave cloud radiative effect (SWCRE) in the Southeastern Pacific (SEPac) and Southeastern Atlantic (SEAtl) stratocumulus regions. Error bars representing one standard error in ordinary-least-square linear regression are only shown for major CCF components, i.e., SST (red) for local temperature and air temperature at 700 mb (T700, orange) and relative humidity at 700 mb (RH700, blue) for ascent area temperature. Other CCFs include relative humidity at 925 mb (RH925, purple) and subsidence rate at 500 mb (\({\omega }_{500}\), brown). c Locations of stratocumulus regions (gray contours) and the correlation map between T700 anomalies of each grid box (T700local) and average T700 anomalies of ascent areas (T700ascent). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Negative linear relationship between SWCRE sensitivities to SST and T700

In the following analysis, we focus on a simple bivariate linear regression model of SWCRE variations with local SST and T700 anomalies:

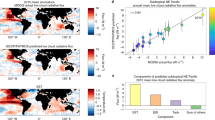

\(\xi\) is a random error. For simplicity, we omit the subscript of SSTlocal in this linear regression hereafter. The SWCRE sensitivities to SST and T700 are estimated for both observations (best estimates and one standard error computed from the ordinary-least-square (OLS) linear regression in horizontal and vertical orange bars) and CMIP6 models (colored dots) in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1. Broadly speaking, models with a high equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS > 4.5 K, in stars) often have a higher SWCRE sensitivity to warming, while low-ECS models (ECS < 3 K, in diamonds) tend to have a lower SWCRE sensitivity. Because multi-model averages often outperform individual models33,34, we also generate all possible 5-member model subensembles allowing repetitions (gray dots; n = 201,376) to explore the variable space of weighted multi-model averages in place of assumptions of normal distributions like in ref. 35. Here the subensemble size, 5, is chosen to be sufficiently large (Supplementary Fig. 2) and computationally reasonable for the Pareto optimization approach in the next section, following36,37.

a Southeastern Pacific (SEPac), and (b) Southeastern Atlantic (SEAtl) stratocumulus regions are defined in Fig. 1c. Best estimates and one standard error of observational sensitivities from ordinary-least-square linear regression is shown in horizontal and vertical orange bars. CMIP6 models are plotted in colored dots (stars for models with high equilibrium climate sensitivity, a.k.a., ECS, squares for medium-ECS models, and diamonds for low-ECS models; ECS values given in parenthesis in legends). Gray dots represent all possible 5-member model subensembles generated from the 28 CMIP6 models, and the darkness of each dot represents the likelihood with respect to the observations (Methods). Additional lines include the best linear fit of original models passing through the origin (solid), and the theoretical lines derived from the estimated cloud-top entrainment index (ECTEI, dashed) and estimated inversion strength (EIS, dotted) as cloud controlling factors.

Subensembles in Fig. 2 are shaded based on their likelihood with respect to observations (Methods), and this likelihood is later used as weighting to update the probability distribution of long-term tropical SWCF constrained by individual stratocumulus regions. The darker a subensemble dot is, the better it agrees with observations in this regional-average measure. In both stratocumulus regions, there is a significant negative linear relationship between dSWCRE/dSST and dSWCRE/dT700 among the CMIP6 models, and we fit it with a solid line passing through the origin.

EIS38 and the estimated cloud-top entrainment index (ECTEI39,) are two widely-used CCFs that condense multiple meteorological parameters and link the LTS with low cloud amount. Both metrics are primarily built upon the potential temperature difference between the surface and the lower free troposphere, and ECTEI further includes the effect of the specific humidity gradient between the boundary layer and the free troposphere. They can be both linearized as functions of local SST, T700 and other secondary parameters (see Methods):

Here \(f\) and \(g\) are functions of secondary parameters, such as relative humidity, and are independent of the variations in local SST and T700. The ratios of the SST coefficient to the T700 coefficient in the linearized formula are also plotted in Fig. 2 in dashed lines. These lines are equivalent to linear regression lines if the corresponding CCFs are linear to SWCRE and the secondary factors can be approximated as random errors.

In SEPac, the negative linear relationship among CMIP6 models is strong (r = −0.82), and is consistent with the observational estimates. The linear fitting line is also close to the ECTEI line. Because EIS does not account for the specific humidity effect which further destabilizes the lower troposphere when the surface is warm39,40, the ratio of dSWCRE/dSST to dSWCRE/dT700 along the EIS line is underestimated compared with other estimates. Regarding the exact magnitudes of the SWCRE sensitivities to SST and T700, BCC-CSM2-MR and MPI-ESM1.2-HR show best performance compared with the observation. The CESM2 family and E3SM-1.0 are the only models that overestimate the SWCRE sensitivities, while many more models underestimate the sensitivities. IITM-ESM and MIROC6 even have signs opposite to the observation and other models. The best subensembles can lie within the error bars of the observations for these regional-average measures.

A weaker yet significant (\(\alpha\) = 0.01) negative relationship exists among CMIP6 models in SEAtl (r = −0.47). The linear fitting line for the models is again consistent with observations. However, both the ECTEI and EIS lines underestimate the ratio of dSWCRE/dSST to dSWCRE/dT700, which means that the low clouds there are more sensitive to local warming relative to ascent area warming than theories due to neglected processes, e.g., latent heat flux and wind speed (Supplementary Note 122,41). Hence, SEAtl is likely to be less sensitive to the SST warming pattern as the low cloud changes are dominated by local surface conditions. This inter-basin difference between SEPac and SEAtl may be associated with the spatial pattern of the WTG approximation suggested by the T700 correlation map (Fig. 1c). Almost all models except CESM2 systematically underestimate the magnitudes of the SWCRE sensitivity to local SST in the Atlantic, leading to limited improvement from subensembles. By contrast, CESM2 agrees well with the observations.

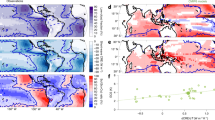

Multi-objective observational constraint on tropical low cloud feedback using Pareto optimization

The combined performance of a model or a subensemble in simulating the cloud sensitivities to SST and T700 can be measured by the distance between the model and observations in Fig. 2 (or more accurately, the RMSE defined in Methods). These RMSE measures are summarized in Fig. 3. The objective is to minimize the model errors in both basins. However, it is notable that the best models or subensembles in SEPac are different from the best ones in SEAtl. In order to objectively weigh the trade-off between the model performance in the two basins, we apply a Pareto optimization approach developed in refs. 36,37 which is suitable for two or more independent objectives (Methods). The concept of Pareto optimality means that the measure of one objective cannot be further improved without degrading another objective. In Fig. 3b, the red dots in the lower left corner are those subensembles forming the Pareto-optimal set, i.e., the set for which no further error reduction can be achieved simultaneously in both basins. Relative to the original multi-model mean, the Pareto-optimal mean SWCRE sensitivities to local SST and T700 not only agree better with observations but also have smaller standard deviations (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 3). This Pareto optimization approach is thus capable of reducing the model bias and narrowing the model spread. The orange hatching in Fig. 3b extends the Pareto-optimal set by including uncertainty in observational estimates (95% confidence interval, illustrated by the fan shapes in Fig. 3a). All 28 models are located outside the hatched area, but low-ECS models (in diamonds) usually have higher RMSEs than medium- and high-ECS models (in squares and stars). SAM0-UNICON, CanESM5, MRI-ESM2.0 and CMCC-CM2-SR5 are the models closest to the hatched area, i.e., close to being within the observational uncertainty. Overall, the spread of the points yields a trade-off between models and subensembles that perform better in one basin and those that perform better in the other.

Model-observation root mean squared errors (RMSE) with respect to the shortwave cloud radiative effect (SWCRE) sensitivities to local sea surface temperature and air temperature at 700 mb (Methods) for 28 CMIP6 models (colored dots; stars for models with high equilibrium climate sensitivity, a.k.a., ECS, squares for medium-ECS models, and diamonds for low-ECS models) and 5-member model subensembles (gray dots). a Schematic illustrating the generation of subensembles and propagation of confidence interval (CI) from the Pareto-optimal set (red dots). Dark gray dots represent subensembles based on four randomly chosen models (marked by a curly brace in the legend) to illustrate subensemble construction. Fan shapes schematically indicate observational uncertainty of individual points in the Pareto-optimal set. The orange hatched region indicates subensembles within the observational uncertainty (95% confidence interval) of the Pareto-optimal set, which is also the envelope of all fan shapes. In (b), all the 28 CMIP6 models and the 95% CI of the Pareto-optimal set (orange hatching) are plotted, similar to (a). In (c), all subensembles are colored based on their multi-objective Pareto probability density function (PDF). The inset shows a cross-section (solid blue line) of the Pareto PDF.

Model-observation root mean squared error (a, c) caused by the SWCRE sensitivity to local SST (Methods) and its standard deviation (b, d) for the simple multi-model mean (a, b) and the Pareto-optimal set (c, d) defined in Fig. 3. For a fair comparison, the standard deviations (SD) in (b) are scaled by the square root of subensemble size (n = 5) following the central limit theorem.

Based on the concept of Pareto optimality, we assign weights to every subensemble and every model (Fig. 3c and Methods). This weight is associated with the probability density function (PDF) computed from the closest point within the Pareto-optimal set which considers observational uncertainty. Points near the Pareto-optimal set have a higher PDF and hence weight, illustrated with a cross-section in the inset. The weighting is also consistent with the observational CI in Fig. 3b. The weights will be used to update the probability distribution of long-term tropical SWCF with a Bayesian approach (Methods).

The tropical SWCF of each subensemble is estimated using the ratio of tropical SWCRE change to the global mean surface temperature rise in the first 150 years of the abrupt-4xCO2 experiment. This simple estimate agrees reasonably well with the tropical SWCF estimated from a radiative kernel (Supplementary Fig. 45). The probability distribution of the feedback among original models (blue in Fig. 5) appears relatively uniform across the range of −0.4 ~ 0.8 Wm−2K−1. By contrast, the subensembles have a Gaussian probability distribution with a peak at 0.21 Wm−2K−1 (purple).

The probability distribution is updated with observational constraints in multiple ways, including two multi-objective Pareto constraints and two single-basin constraints. For the first one, hereinafter referred to as the Pareto-PDF constraint, we use the PDF-based weights in Fig. 3c for each subensemble (orange). Additionally, we adjust the weights by assuming a uniform prior probability distribution in the 2-D phase space in Fig. 3 so that the similarity among subensembles is properly accounted for (Methods). For the second one, hereinafter referred to as the Pareto-set constraint (brown), we simply exclude any subensemble outside the 95% CI of the Pareto-optimal set. These two methods provide very similar results: the peak becomes 71% higher at 0.36 Wm−2K−1, and the variance decreases compared with original subensembles. Both multi-objective Pareto constraints more than triple the probability of a large positive tropical SWCF (>0.5 Wm−2K−1) from 5% to 18%. Although the CESM2 model family tends to occupy a particular part of Fig. 3 (high Pacific error, medium Atlantic error), excluding all CESM2-family models has little effect on the Pareto-optimal set and thus on overall conclusions (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6).

The last two observational constraints are single-basin constraints assuming a uniform prior probability distribution in the 2-D phase space in Fig. 2 and using the PDFs from the same figure as weights. The SEPac constraint leads to a smaller yet positive shift in the SWCF distribution (green). The SEAtl constraint results in the largest positive shift in the probability distribution. Therefore, the multi-objective constraints effectively mediate the different results of single-basin constraints, but the variance is greater than any single-basin constraint. All four observational constraints nearly eliminate the probability of a negative tropical SWCF, similar to the conclusion from refs. 22,31.

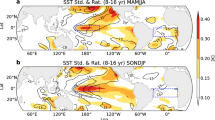

For a brief comparison with traditional emergent constraints based on a significant linear relationship between the interannual SWCRE sensitivity and the long-term SWCF, we make Fig. 6. Significant positive correlations are found between the interannual sensitivity of SWCRE to local SSTs and T700 in each basin and the long-term tropical SWCF across the 28 CMIP6 models, which justifies our observational constraint purely based on these two regions. However, traditional emergent constraints suggest an even stronger tropical SWCF than the constraints described in Fig. 5, especially when considering the SEAtl constraint. This difference is partly due to the fact that subensemble averages used in the multi-objective constraint cannot extrapolate outside the variable range, such as the SWCRE sensitivity (Fig. 2).

Individual CMIP6 models are plotted in scatter points and linear regression lines (significant at the level of 0.01) are drawn. The horizontal bars indicate the best estimates and one standard error from the bivariate linear model (Eq. 1) using observational data. Blue and orange represent the regression coefficients for Southeastern Pacific (SEPac) and Southeastern Atlantic (SEAtl) stratocumulus regions, respectively. The emergent constraint on tropical SWCF can be visually derived from the intersection of the regression line and the observational estimate on the y-axis. For comparison, the probability density function (PDF) of tropical SWCF updated using the multi-objective Pareto constraint (orange curve in Fig. 5) is plotted on the right axis.

Implications for equilibrium climate sensitivity

Given a radiative forcing (e.g., doubling atmospheric CO2 concentration), the equilibrium surface air temperature change is inversely proportional to the net negative feedback of the Earth system (e.g., ref. 42). With the multi-objective observational constraints (Fig. 5), we derive a more positive tropical SWCF in CMIP6 abrupt-4xCO2 experiments compared with the original value. This result implies a possibly less negative net climate feedback and a higher ECS, if the effective radiative forcing and all other feedbacks are held constant. Furthermore, an observational constraint favoring more positive tropical SWCF may potentially increase the multi-model extratropical SWCF simultaneously, because of a positive correlation between tropical and extratropical cloud feedbacks among the CMIP6 models43.

In this study, we focus on constraints for the marine stratocumulus feedback which is underestimated and contributes to a source of negative ECS bias in CMIP6 models. However, we underline that other processes beyond the scope of this study may cause a positive ECS bias44,45,46, such as the cumulus feedback30 or other components of the Earth system including vegetation47 and cryosphere48.

In addition, the high tropical cloud feedback in our results rely on the reduction of the Pacific zonal SST gradient simulated by CMIP6 models. However, ref. 31 pointed out that this expected SST gradient reduction did not occur over the past few decades, implying possible overestimation of the SST warming pattern change. If warming is more uniform between cold stratocumulus regions and warm ascent areas, our estimates (Fig. 1) would suggest a much lower or even negative tropical low cloud feedback.

Discussion

Compared with previous studies which also utilized observations to constrain the marine low cloud feedback (e.g., refs. 30,31), one significant difference in our work is the choice of CCFs (local SST and T700) that explicitly consider the influence of the surface warming pattern. Instead of EIS which blends the local warming and free-tropospheric warming (Supplementary Fig. 7), T700 is weakly related to local surface temperature changes but mainly determined by remote ascent area through deep convection and the WTG. This clear separation between surface and free-tropospheric influence over low clouds helps identify model deficiencies in a 2-D phase space (Fig. 2), which is more relevant in the context of an evolving SST warming pattern during anthropogenic climate change. Nonetheless, when used as a regressor in a bivariate linear regression model together with SST (Eq. 1), EIS and T700 generate similar reconstructed time series of interannual SWCRE anomalies as the response variable (Supplementary Fig. 8). This is because T700 accounts for most of the EIS variability when SST is held constant.

Observational constraints of climate feedbacks and ECS can be done in various ways, from directly extrapolating physical parameters from interannual variations to long-term warming (e.g., ref. 30) to finding a specific linear relationship across a multi-model ensemble for an emergent constraint. Noticing the regional difference in the low cloud dynamics (Fig. 2) and the trade-off between model errors in SEPac and SEAtl (Fig. 3), we apply the Pareto multi-objective optimization approach for an objective weighting between the two marine stratocumulus regions. This approach retains the spatial information and reduces both the model error and its standard deviation relative to the original CMIP6 model ensemble (Fig. 4). Subensembles used in this approach provides additional advantages, as they are able to perform better than individual models (closer to the Pareto-optimal set in Fig. 3b) and the similarity between subensembles can be easily accounted for. These advantages enable more robust estimates of the multi-model SWCF when the observational constraint is applied. In future studies, this approach can be easily extended to include other independent observational constraints, e.g., cumulus feedback which climate models are known to overestimate30,31.

Previous SST pattern effect studies usually focus on SEPac while overlook the contributions from SEAtl (e.g., refs. 17,23,25,). Here we disclose a clear inconsistency among observations, climate models and theories in SEAtl regarding the low cloud sensitivities to surface and tropospheric warming (Fig. 2). As theories, both EIS and ECTEI attempt to account for the influence of the boundary layer and the lower free troposphere over low clouds based on specific hypotheses, but these hypotheses may not work well everywhere. In particular, ECTEI agrees well with the observation and models in SEPac while it underestimates the local SST influence relative to the T700 influence in SEAtl. We expect some modifications in the ECTEI formula when the low cloud processes in the Atlantic are better understood in the future. Although CMIP6 models are consistent with the observation in SEAtl with respect to the ensemble linear fit, they systematically underestimate the cloud sensitivities to local SST.

Methods

Observational dataset

Observational low cloud fraction (LCF) and shortwave cloud radiative effect (SWCRE) are derived from the Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System (CERES) SYN1deg-Month Ed4.1 product49,50 during 2001–2014. These top-of-atmosphere (TOA) radiative fluxes and cloud properties are collected by the sensors CERES and MODIS onboard two polar-orbiting satellites, Terra and Aqua. Data are downloaded as monthly time series on a 1°x1° geographic grid. SWCRE is computed as the difference between all-sky and clear-sky TOA shortwave fluxes.

Observational cloud controlling factors (CCFs), including sea surface temperature, air temperature, relative humidity, and vertical velocity at specific pressure levels, are extracted from the fifth generation of the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecast (ECMWF) reanalysis (ERA5)51 as monthly time series on a 0.25°x0.25° geographic grid during the same period. These meteorological fields are re-interpolated to match the CERES 1°x1° grid.

The climatology is subtracted to get monthly anomalies of all observational variables.

Global climate models

Monthly outputs from 28 CMIP6 models (listed in Supplementary Table 2) are analyzed. In addition to sea surface temperature and air temperature, SWCRE is computed as the difference between all-sky and clear-sky TOA upwelling shortwave radiation. For the historical period during 1979–2014 and the CO2-induced long-term warming, single realizations from AMIP and abrupt4xCO2 experiments are used, respectively.

For AMIP experiments, only the period overlapping with observations are analyzed, and the climatology is subtracted to get monthly anomalies of all variables, similar to the treatment of observational data. For abrupt4xCO2 experiments, tropical or global SWCF is simply estimated as the ratio of SWCRE change to global mean sea surface temperature change from the first 30 years (Year 1–30) to the last 30 years (Year 121–150). This simple estimate of global SWCF agrees reasonably well (Supplementary Fig. 4) with more accurate results that apply a radiative kernel to the anomalies in abrupt4xCO2 experiments relative to their corresponding preindustrial control (piControl) simulations5. ECS values of all the models are given in ref. 46 as “ECS150.” We usually use different symbols when plotting models with different ECS levels (stars for ECS > 4.5 K, squares for 3 K < ECS < 4.5 K, and diamonds for ECS < 3 K).

Tropical marine stratocumulus region and ascent region

For the analyses of both observations and model outputs, the tropical (30°N − 30°S) marine stratocumulus regions are defined as locations where the stratocumulus fraction is over 50% in the CloudSat-CALIPSO CASCCAD dataset32. We focus on the two largest contiguous stratocumulus regions identified using this criterion, namely the Southeastern Pacific (SEPac), and the Southeastern Atlantic (SEAtl). Both regions are located off the western coast of continents (Fig. 1c).

We define the tropical ascent region by a negative climatological \({\omega }_{250}\), i.e., a climatological ascent at 250 mb.

Contribution from CCFs to the low cloud sensitivity to local and ascent area SSTs

The contribution is computed from the observed interannual variability of low cloud and CCFs. First, regional mean monthly LCF and SWCRE anomalies are regressed on local mean and remote ascent area mean SST anomalies.

Here C is the cloud variable, either LCF or SWCRE. In order to eliminate the correlation between local and ascent area SST on the interannual scale, the ascent area SST in Eq. 4 is replaced by the orthogonal component of ascent area SST anomalies (\(\triangle {{{{\rm{SST}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ascent}}}}}^{\perp }\)) after regressing against \(\triangle {{{{\rm{SST}}}}}_{{{{\rm{local}}}}}\) (i.e., \(\triangle {{{{\rm{SST}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ascent}}}}}-\triangle {{{{\rm{SST}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ascent}}}}}^{\perp }\propto \triangle {{{{\rm{SST}}}}}_{{{{\rm{local}}}}}\)). This treatment effectively assumes that the collinear component between \(\triangle {{{{\rm{SST}}}}}_{{{{\rm{local}}}}}\) and \(\triangle {{{{\rm{SST}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ascent}}}}}\) is all due to the local effect, so the remote SST effect may be underestimated.

The amount of marine low clouds can be well predicted by a set of CCFs (e.g., ref. 21). In this study, we chose five CCFs: local SST, lower-troposphere temperature at 700 mb, subsidence rate at 500 mb (\({\omega }_{500}\)) and relative humidity of the boundary layer (925 mb) and the lower free troposphere (700 mb), respectively. Hence, the low cloud anomalies can be written in a linear equation, assuming the linear coefficients are insensitive to the climate state.

By computing the derivative of Eq. 5 with respect to \({{{{\rm{SST}}}}}_{{{{\rm{local}}}}}\) or \({{{{\rm{SST}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ascent}}}}}^{\perp }\), the cloud sensitivity to \({{{{\rm{SST}}}}}_{{{{\rm{local}}}}}\) or \({{{{\rm{SST}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ascent}}}}}^{\perp }\) is linearly decomposed into contributions from different CCFs.

Each term on the right-hand side represents the net contribution of a specific CCF to the cloud sensitivity to local or ascent area SST anomalies, and is plotted in Fig. 1. Because LCF and SWCRE anomalies vary in opposite signs, the decomposition results are also expected to be in opposite signs. When using the ordinary least square method to solve the regressions, it can be shown that there are no residual terms in these two decomposition equations.

Sensitivities of SWCRE, EIS and ECTEI to SST and T700

In the main text, we have shown a bivariate linear regression model that treats the SWCRE variation as a function of SST and T700 anomalies. For a low cloud index like EIS and ECTEI, it can also be written as a function of these two variables, assuming other factors play a minor role. Then we can linearize the formula of the index, I (EIS or ECTEI):

The two linear coefficients can be approximated using the definitions of EIS and ECTEI together with a few typical meteorological parameters (relative humidity \(r\) and saturation specific humidity \({q}^{*}\) near the surface and at 700 mb) in SEPac and SEAtl.

If the low cloud index, I, is proportional to SWCRE, we will get:

Therefore, if a straight line defined by the linear coefficients of \(I\) passes through the model points defined by the linear coefficients of SWCRE in Fig. 2, it would indicate a good linear relationship between the low cloud index, \(I\), and SWCRE variations. This type of agreement between the theory and CMIP6 models is seen for ECTEI in SEPac (Fig. 2a).

The uncertainty in observational linear coefficients is estimated using bootstrapping. Samples (n = 1000) are generated by randomly sampling (with replacement) months from the observational monthly anomaly time series, and the linear regression is repeated for each bootstrap sample. A bivariate joint normal distribution of the SST and T700 coefficients is constructed in this way, and then the probability density of all models and model subensembles in Fig. 2 can be computed from this joint normal distribution. This probability density is used as weighting to update the tropical shortwave cloud feedback in the next sections.

Measurement of the model-observation difference in SWCRE sensitivities

We define the model error in SWCRE sensitivities by a combined root-mean-square error:

Here each data point from the space-time matrix is treated as independent sample points and then averaged, and \(m\) and \(n\) represent the number of data points along the space and time dimensions, respectively. The formula of the RMSE shows that it is the root mean square of the standard deviations of SST and T700 scaled by the model-observation differences in the SWCRE sensitivities across all spatial points within a stratocumulus region, which are plotted in Fig. 4 as a spatial map. One way to conceptualize this error measure is the Euclidean distance between the model and the observation in Fig. 2 weighted by the respective amplitudes of interannual variations in SST and T700, although the spatial information is omitted in Fig. 2 which uses the regional mean anomalies instead.

We further consider the uncertainty of the RMSE measures resulting from the uncertainty in observational sensitivities due to the linear regression. Bootstrap samples (n = 1000) are generated by randomly shuffling the time steps of the monthly anomaly time series, and the RMSE computation is repeated for each bootstrap sample. The probability distribution of the RMSE estimates from these bootstrap samples is approximated with a joint normal distribution, and then the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the RMSE value for each subensemble can be computed.

Constructing the Pareto-optimal set from subensembles

The RMSE defined in the last section measures the model performance in simulating the dependence of SWCRE on local SST and T700 in a single stratocumulus region. In Fig. 3, we clearly see a trade-off between a better simulated SEPac and a better simulated SEAtl. Hence, we apply a Pareto optimization approach following refs. 36,37 to handle this multi-objective optimization problem.

We make full use of the ~200,000 5-member subensembles generated from the 28 CMIP6 models. We repeat the RMSE computation to evaluate the performance of each subensemble in Fig. 3. There is a higher density of data points near the center of the data cloud and a lower density towards the boundary (Supplementary Fig. 9).

The concept of Pareto optimization means that the error in one dimension cannot be further reduced without lowering the performance in another dimension. Therefore, the Pareto-optimal set, consisting of red points near the lower left corner in Fig. 3 represent the best we can do by linearly combining different models. As explained in the previous section, the observational uncertainty of each point within the Pareto-optimal set can be approximated by a joint normal distribution. Therefore, the 95% CI of each point is represented by an ellipse, and the selected wedges drawn in Fig. 3a help illustrate the part of these confidence ellipses that contains other subensembles. The union of all these wedges along the Pareto-optimal set forms the entire 95% CI of the Pareto-optimal set.

Weighting of every subensemble

Subensembles in Fig. 3 are weighted based on their best proximity to any points within the Pareto-optimal set in a probabilistic sense. Specifically, we define the weight in two ways. The first solution is a simple two-value weighting based on whether the subensemble falls within the 95% CI of the Pareto-optimal set. This solution is associated with the “Pareto-set constraint” in Fig. 5, and is given by the following equation.

In the second solution, we again use the estimated bivariate joint normal distribution of individual Pareto-optimal subensembles described in previous sections. For every other subensemble, its weight is chosen as the maximum probability density among all the normal distributions derived from the Pareto-optimal set. In other words, we first compute the probability density of any subensemble \(i\) with respect to one Pareto-optimal subensemble j. Then the weight of the subensemble \(i\) is the maximum probability density among all Pareto-optimal subensembles.

These two solutions provide similar results in Figs. 3 and 5.

Bayesian updates of SWCF using observational constraints

The probability distribution of long-term SWCF among all subensembles is updated using different observational constraints (Fig. 5). Similar to ref. 35, the posterior probability distribution of the SWCF is approximated with a weighted mean across all subensembles:

However, our approach combines Bayesian methods and Pareto optimization, which objectively handles the trade-off between multiple observational constraints and down-weights models that perform poorly in every aspect. The weight of each subensemble represents the degree to which it agrees with observations and the Pareto-optimal subensembles, as described in the section “Weighting of every subensemble”.

We also account for the similarities among subensembles by choosing reasonable prior probability distribution. For the single-basin constraints using SEPac and SEAtl observations, we assume a uniform prior probability distribution in the 2-D phase space in Fig. 2. Then, the contribution of each subensemble to the weighted mean is divided by the local density of data points, computed using small search neighborhoods. Here, we use a search radius of 5% of the range of the data points as measured by the longest line segment that fits within the cloud of points. This step prevents over-counting of subensembles with similar SWCRE sensitivities to both SST and T700. For the multi-objective Pareto constraints, we assume a uniform prior probability distribution in the 2-D phase space in Fig. 3. Similarly, the contribution of each subensemble to the weighted mean is divided by the local density of data points.

Data availability

Observational cloud and radiation data are available from the Clouds and Earth’s Radiant Energy System (CERES) SYN1deg-Month Ed4.1 product49,50 and the website (https://ceres-tool.larc.nasa.gov/ord-tool/jsp/SYN1degEd41Selection.jsp). Sea surface temperature, air temperature, relative humidity, and vertical velocity at specific pressure levels, are available from ERA5 reanalysis51 and the website (https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/dataset/ecmwf-reanalysis-v5). Stratocumulus fraction is available from the CloudSat-CALIPSO CASCCAD dataset32 and the website (https://data.giss.nasa.gov/clouds/casccad/). CMIP6 model outputs for the historical period during 1979–2014 and the CO2-induced long-term warming are available from Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison (PCMDI/LLNL) portal (https://pcmdi.llnl.gov/CMIP6/). ECS values of all the models are given in ref. 46 as “ECS150.”. Source Data for Fig. 1a, b are provided with this paper. All necessary data to reproduce the rest of the figures are provided in Code Ocean: https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.4283391.v152. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code for this paper is available in Code Ocean: https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.4283391.v152.

Change history

25 February 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56840-8

References

Hartmann, D. L., Ockert-Bell, M. E. & Michelsen, M. L. The effect of cloud type on Earth’s energy balance: Global analysis. J. Clim. 5, 1281–1304 (1992).

Andrews, T., Gregory, J. M., Webb, M. J. & Taylor, K. E. Forcing, feedbacks and climate sensitivity in CMIP5 coupled atmosphere‐ocean climate models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L09712 (2012).

Bony, S. & Dufresne, J. L. Marine boundary layer clouds at the heart of tropical cloud feedback uncertainties in climate models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L20806 (2005).

Cess, R. D. et al. Intercomparison and interpretation of climate feedback processes in 19 atmospheric general circulation models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 95, 16601–16615 (1990).

Zelinka, M. D. et al. Causes of higher climate sensitivity in CMIP6 models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL085782 (2020).

Klein, S. A. & Hall, A. Emergent constraints for cloud feedbacks. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 1, 276–287 (2015).

Caldwell, P. M., Zelinka, M. D. & Klein, S. A. Evaluating emergent constraints on equilibrium climate sensitivity. J. Clim. 31, 3921–3942 (2018).

Schlund, M., Lauer, A., Gentine, P. & Sherwood, S. Emergent constraints on equilibrium climate sensitivity in CMIP5: do they hold for CMIP6?. Earth Syst. Dyn. 11, 1233–1258 (2020).

Bloch-Johnson, J., Rugenstein, M. & Abbot, D. S. Spatial radiative feedbacks from internal variability using multiple regression. J. Clim. 33, 4121–4140 (2020).

Dong, Y., Proistosescu, C., Armour, K. C. & Battisti, D. S. Attributing historical and future evolution of radiative feedbacks to regional warming patterns using a Green’s function approach: the preeminence of the western Pacific. J. Clim. 32, 5471–5491 (2019).

Fueglistaler, S. Observational evidence for two modes of coupling between sea surface temperatures, tropospheric temperature profile, and shortwave cloud radiative effect in the tropics. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 9890–9898 (2019).

Zhou, C., Zelinka, M. D. & Klein, S. A. Impact of decadal cloud variations on the Earth’s energy budget. Nat. Geosci. 9, 871–874 (2016).

Zhou, C., Zelinka, M. D. & Klein, S. A. Analyzing the dependence of global cloud feedback on the spatial pattern of sea surface temperature change with a G reen’s function approach. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 9, 2174–2189 (2017).

Sobel, A. H. & Bretherton, C. S. Modeling tropical precipitation in a single column. J. Clim. 13, 4378–4392 (2000).

Sobel, A. H., Nilsson, J. & Polvani, L. M. The weak temperature gradient approximation and balanced tropical moisture waves. J. Atmos. Sci. 58, 3650–3665 (2001).

Marvel, K., Pincus, R., Schmidt, G. A. & Miller, R. L. Internal variability and disequilibrium confound estimates of climate sensitivity from observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1595–1601 (2018).

Andrews, T. & Webb, M. J. The dependence of global cloud and lapse rate feedbacks on the spatial structure of tropical Pacific warming. J. Clim. 31, 641–654 (2018).

Miller, R. L. Tropical thermostats and low cloud cover. J. Clim. 10, 409–440 (1997).

Silvers, L. G., Paynter, D. & Zhao, M. The diversity of cloud responses to twentieth century sea surface temperatures. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 391–400 (2018).

Mackie, A., Brindley, H. E. & Palmer, P. I. Contrasting observed atmospheric responses to tropical sea surface temperature warming patterns. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2020JD033564 (2021).

Qu, X., Hall, A., Klein, S. A. & Caldwell, P. M. On the spread of changes in marine low cloud cover in climate model simulations of the 21st century. Clim. Dyn. 42, 2603–2626 (2014).

Qu, X., Hall, A., Klein, S. A. & DeAngelis, A. M. Positive tropical marine low-cloud cover feedback inferred from cloud-controlling factors. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 7767–7775 (2015).

Ceppi, P. & Gregory, J. M. Relationship of tropospheric stability to climate sensitivity and Earth’s observed radiation budget. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 13126–13131 (2017).

Yuan, T., Oreopoulos, L., Platnick, S. E. & Meyer, K. Observations of local positive low cloud feedback patterns and their role in internal variability and climate sensitivity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 4438–4445 (2018).

Andrews, T., Gregory, J. M. & Webb, M. J. The dependence of radiative forcing and feedback on evolving patterns of surface temperature change in climate models. J. Clim. 28, 1630–1648 (2015).

Dong, Y. et al. Intermodel spread in the pattern effect and its contribution to climate sensitivity in CMIP5 and CMIP6 models. J. Clim. 33, 7755–7775 (2020).

Gregory, J. M. & Andrews, T. Variation in climate sensitivity and feedback parameters during the historical period. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 3911–3920 (2016).

Klein, S. A. & Hartmann, D. L. The seasonal cycle of low stratiform clouds. J. Clim. 6, 1587–1606 (1993).

Zhou, C., Zelinka, M. D., Dessler, A. E. & Klein, S. A. The relationship between interannual and long‐term cloud feedbacks. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 10–463 (2015).

Myers, T. A. et al. Observational constraints on low cloud feedback reduce uncertainty of climate sensitivity. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 501–507 (2021).

Cesana, G. V. & Del Genio, A. D. Observational constraint on cloud feedbacks suggests moderate climate sensitivity. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 213–218 (2021).

Cesana, G., Del Genio, A. D. & Chepfer, H. The cumulus and stratocumulus cloudsat-calipso dataset (casccad). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 1745–1764 (2019).

Knutti, R., Furrer, R., Tebaldi, C., Cermak, J. & Meehl, G. A. Challenges in combining projections from multiple climate models. J. Clim. 23, 2739–2758 (2010).

Jiang, J. H., Su, H., Wu, L., Zhai, C. & Schiro, K. A. Improvements in cloud and water vapor simulations over the tropical oceans in CMIP6 compared to CMIP5. Earth Space Sci. 8, e2020EA001520 (2021).

Lutsko, N. J., Popp, M., Nazarian, R. H. & Albright, A. L. Emergent constraints on regional cloud feedbacks. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL092934 (2021).

Langenbrunner, B. & Neelin, J. D. Multiobjective constraints for climate model parameter choices: pragmatic Pareto fronts in CESM1. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 9, 2008–2026 (2017).

Langenbrunner, B. & Neelin, J. D. Pareto‐optimal estimates of California precipitation change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 12–436 (2017).

Wood, R. & Bretherton, C. S. On the relationship between stratiform low cloud cover and lower-tropospheric stability. J. Clim. 19, 6425–6432 (2006).

Kawai, H., Koshiro, T. & Webb, M. J. Interpretation of factors controlling low cloud cover and low cloud feedback using a unified predictive index. J. Clim. 30, 9119–9131 (2017).

Koshiro, T., Kawai, H. & Noda, A. T. Estimated cloud-top entrainment index explains positive low-cloud-cover feedback. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2200635119 (2022).

Naud, C. M., Elsaesser, G. S. & Booth, J. F. Dominant cloud controlling factors for low-level cloud fraction: subtropical versus extratropical oceans. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL104496 (2023).

Gregory J. et al. A new method for diagnosing radiative forcing and climate sensitivity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L03205 (2004).

Zelinka, M. D., Klein, S. A., Qin, Y. & Myers, T. Evaluating climate models’ cloud feedbacks against expert judgment. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127, e2021JD035198 (2022).

Sherwood, S. C. et al. An assessment of Earth’s climate sensitivity using multiple lines of evidence. Rev. Geophys. 58, e2019RG000678 (2020).

Massoud, E. C., Lee, H. K., Terando, A. & Wehner, M. Bayesian weighting of climate models based on climate sensitivity. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 365 (2023).

Hausfather, Z., Marvel, K., Schmidt, G. A., Nielsen-Gammon, J. W. & Zelinka, M. Climate simulations: recognize the ‘hot model’ problem. Nature 605, 26–29 (2022).

Song, X., Wang, D. Y., Li, F. & Zeng, X. D. Evaluating the performance of CMIP6 Earth system models in simulating global vegetation structure and distribution. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 12, 584–595 (2021).

Thackeray, C. W., Hall, A., Zelinka, M. D. & Fletcher, C. G. Assessing prior emergent constraints on surface albedo feedback in CMIP6. J. Clim. 34, 3889–3905 (2021).

Doelling, D. R. et al. Geostationary enhanced temporal interpolation for CERES flux products. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 30, 1072–1090 (2013).

Doelling, D. R. et al. Advances in geostationary-derived longwave fluxes for the CERES synoptic (SYN1deg) product. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 33, 503–521 (2016).

Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), ERA5: Fifth generation of ECMWF atmospheric reanalyses of the global climate, Copernicus Climate Change Service Climate Data Store (CDS) (2017).

Wu, M., Su, H. & Neelin, J. D. Codes for Multi-objective observational constraint of tropical Atlantic and Pacific low-cloud feedbacks mediates conflicting regional climate-sensitivity contributions. https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.4283391.v1 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NOAA NA20OAR431 (M.W., H.S., J.D.N.), U.S. Department of Energy DE-SC0021312 (M.W., H.S., J.D.N.), Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust FA123 and Research Grants Council General Research Fund 16300823 (M.W., H.S.), and National Science Foundation AGS-1936810, AGS-2414576 (J.D.N.). We thank Ni Dai for her help with the computation of estimated inversion strength, Haitong Sun for his comments on the methodology, Joyce Meyerson and Biying Zhu for graphical assistance with Fig. 3, and Leo Donner, Seman Charles and Kathleen Schiro for their scientific comments on the entire project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.W., H.S. and J.D.N. designed the project and developed the methodology. M.W. conducted the analyses and prepared the display items. M.W. drafted the paper with significant contributions from H.S. and J.D.N.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, M., Su, H. & Neelin, J.D. Multi-objective observational constraint of tropical Atlantic and Pacific low-cloud variability narrows uncertainty in cloud feedback. Nat Commun 16, 218 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53985-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53985-w