Abstract

Time crystals are a dynamical phase of periodically driven quantum many-body systems where discrete time-translation symmetry is broken spontaneously. Time-crystallinity however subtly requires also spatial order, ordinarily related to further symmetries, such as spin-flip symmetry when the spatial order is ferromagnetic. Here we define topologically ordered time crystals, a time-crystalline phase borne out of intrinsic topological order—a particularly robust form of spatial order that requires no symmetry. We show that many-body localization can stabilize this phase against generic perturbations and establish some of its key features and signatures, including a dynamical, time-crystal form of the perimeter law for topological order. We link topologically ordered and ordinary time crystals through three complementary perspectives: higher-form symmetries, quantum error-correcting codes, and a holographic correspondence. Topologically ordered time crystals may be realized in programmable quantum devices, as we illustrate for the Google Sycamore processor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Time Crystals (TCs)1,2,3 are periodically driven (i.e., Floquet) systems that spontaneously break discrete time-translation symmetry and a global internal symmetry G (such as the spin-flip symmetry of an Ising ferromagnet)4,5,6,7,8,9,10. To form a phase of matter, TCs must be protected from the drive-induced heating. A route is via many-body localization11,12,13 (MBL): with strong disorder, local degrees of freedom emerge that remain inert if their energies are much below the driving frequency 2π/T4,5,6,7,8,9,10. TCs display long-range spatiotemporal order7,8. That is, local order parameters Oj (i.e., operators at position j that transform nontrivially under G) exist such that, for large ∣j − k∣ and for any eigenstate \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\) of the time-evolution operator, the time-dependent expectation \(\left\langle \psi \right\vert {O}_{j}(mT){O}_{k}(0)\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\) has period greater than one as the function of the integer m.

Many-body systems can however display orders other than symmetry breaking. A key example is topological order (TO), with anyonic quasiparticles or ground-state degeneracy depending only on the topology of the configuration space14,15,16. These striking phenomena motivated numerous advances (e.g., symmetry-protected or -enriched topological phases17,18,19) and applications [e.g., quantum error correcting (QEC) codes14,20,21]. Studies of topological matter (although mainly with topology distinct from TO) also include dynamical quenches22,23 or driven systems 24,25,26,27,28.

In this work, we ask: how may TCs emerge from TO as the underlying spatial quantum fabric? TO has no global symmetry G in the usual sense, has no local order parameters, and its nonlocal features may seem in tension with MBL. Hence the resulting topologically ordered TCs (TTCs) would be fundamentally distinct from TCs (or Floquet symmetry-protected topological phases25,26,27,28), but even their definition seems challenging.

A fruitful analogy to TCs does however arise7,8 if we generalize G to higher-form symmetries29,30,31: TO appears as the spontaneous breaking of these, and this does have—albeit nonlocal—order parameters. Here we define TTCs based on these ingredients.

We also show that TTCs form a phase of matter: they do not need fine-tuning and have observable signatures. We establish this by invoking MBL. As TO requires two dimensions (2D) or higher, TTCs require MBL in 2D or above, and a form of TO compatible with MBL: so-called nonchiral Abelian TO14,15,16,32,33,34,35. In 2D, MBL may arise as a long-lived pre-thermal phase persisting beyond current experimental time-scales36,37,38,39. Focusing on this pre-thermal regime, we show that TTCs are robust against perturbations, and we establish some key TTC features. These include a dynamical, time-crystal form of the perimeter law, a TO signature—via nonlocal order parameters—of the same status as long-range correlations for spontaneous symmetry breaking32,33,40,41. A recent experiment realizing our proposed TTC on an intermediate scale quantum processor supports the predictions accessible at that scale42.

To establish our results, we formulate TTCs as Floquet-MBL versions of TO systems related to QEC codes. On the technical level, this allows us to use a topological variant35 of local integrals of motion (LIOMs)43,44,45,46,47, an MBL framework that has been key for ordinary TCs5,7,8. Such topological LIOMs (tLIOMs) will give a similarly useful framework for TTCs. Conceptually, our approach highlights QEC codes as another unifying perspective bridging TCs and TTCs. We illustrate our findings, including both the QEC and the higher-form symmetry perspectives, on the surface code14,20,21 (the simplest TO); using these systems we also highlight yet another unifying view: a holographic TTC–to–TC correspondence. We also explain how these surface-code-based (pre-thermal) TTCs can be created in the Google Sycamore processor48,49 from available ingredients.

Results

TTCs via QEC codes and generalized symmetries

We seek TTCs in Floquet systems. Over a driving period T, the time evolution is generated by the Floquet unitary \({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\equiv {{\mathcal{T}}}\exp [-i\int_{0}^{T}H(t)dt]\), where \({{\mathcal{T}}}\) is time ordering and H(t) is a local Hamiltonian (i.e., a sum of finite-range bounded-norm terms50) at time t. In particular, \(O(mT)={U}_{\,{\mbox{F}}}^{m{\dagger} }O(0){U}_{{\mbox{F}}\,}^{m}\) for any operator O = O(0). We mostly focus on two-step drives, i.e., H(t) = H0/t0 for 0 ⩽ t < t0 and H(t) = H1/t1 for t0 ⩽ t < t0 + t1 ≡ T. This gives \({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=\exp (-i{H}_{1})\exp (-i{H}_{0})\).

For simplicity, we consider lattice systems of N qubits, but the ideas are more general, as we shall discuss. To explain how TTCs arise, we first describe UF for ordinary TCs, focusing on 1D systems with \(G={{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\) (i.e., spin-flip) symmetry4,5,7,8,25. The symmetry operator is P = ∏jXj and, by P†ZjP = − Zj, we can use Zj as a local order parameter (Xj and Zj are Pauli X and Z operators at site j, respectively). The key TC features originate from the unperturbed limit where H0 = ∑jJjZjZj+1, with Jj real, and \({H}_{1}=\frac{\pi }{2}{\sum }_{j}{X}_{j}\). In this limit, the Floquet unitary is, up to a phase,

The operators Sj ≡ ZjZj+1 (j = 1, …N − 1) and P provide a complete set of integrals of motion; their eigenvalues sj, p ∈ { − 1, 1} fully specify the eigenbasis \(\left\vert {{\bf{s}}},p\right\rangle\) of \({U}_{\,{\mbox{F}}0}^{({\mbox{TC}})}\), i.e., the Floquet eigenstates. These are spin-glass eigenstates (sj = − 1 marks a domain wall between sites j and j + 1); since \(\left\langle {{\bf{s}}},p\right\vert {Z}_{j}{Z}_{k}\left\vert {{\bf{s}}},p\right\rangle\) is long-ranged, \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\) symmetry is spontaneously broken. The role of H0 in Eq. (1) is to imprint this symmetry breaking. The prefactor P, in turn, introduces period-doubling: by P†ZjP = − Zj and [Zj, H0] = 0, we have Zj(mT) = (−1)mZj(0) and thus the system has long-range spatiotemporal order.

Strong disorder in Jj makes \({U}_{\,{\mbox{F}}0}^{({\mbox{TC}})}\) MBL. This allows one to argue that the TC is robust against perturbing \({U}_{\,{\mbox{F}}0}^{({\mbox{TC}})}\) by local terms in H0,17,8. Remarkably, this holds even for \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\) symmetry breaking terms, a feature dubbed absolute stability7. TTCs will enjoy a similarly enhanced robustness, even compared to TO.

To prepare for constructing TTCs, we re-interpret \({U}_{\,{\mbox{F}}0}^{({\mbox{TC}})}\) via QEC51,52 (see also Ref. 53). In this language, Sj are the check operators for the N-qubit repetition code: measuring them allows detecting a change in s to detect if bit-flips (effected by Xi) have occurred. P and Zj, in turn, are conjugate logical Pauli operators: each preserves s, but they anticommute and enact nontrivial operations within the doublet \(\left\vert {{\bf{s}}},p\right\rangle\), i.e., the logical qubit. (Any of the Zj is an equally valid logical operator choice since Zi ∝ Zj∏k∈VSk for some set V.)

We now use this QEC perspective to construct TTCs. The key observation is that the unperturbed limit of a broad family of TO states—namely, nonchiral, Abelian TOs—also arise as common eigenspaces of suitable mutually commuting and local check operators SP14,15,16. For simplicity, we will mostly assume that, similarly to the TC example, the SP and the logical operators are Pauli strings (tensor products of Pauli operators on qubits); while this captures only a subset of TOs, it already conveys the essential ideas.

The simplest example is the surface code14,20,21, cf. Fig. 1. Here SP are Pauli strings around plaquettes P. For simplicity, we focus on systems furnishing a single logical qubit (i.e., two-fold spectral degeneracies). We choose \(\overline{X}={{{\mathcal{X}}}}_{{\gamma }_{X}}\) for the logical Pauli X with \({{{\mathcal{X}}}}_{{\gamma }_{X}}={\prod }_{j\in {\gamma }_{X}}{X}_{j}\) along path γX. By multiplying \({{{\mathcal{X}}}}_{{\gamma }_{X}}\) with adjacent SP = ∏j∈PXj, one may deform \({{{\mathcal{X}}}}_{{\gamma }_{X}}\) into an equally valid \(\overline{X}\) choice \({{{\mathcal{X}}}}_{\gamma {{\prime} }_{X}}\) along path \({\gamma }_{X}^{{\prime} }\); as deformations cannot detach these paths from their respective surface-code boundaries, the paths are noncontractible. Similar observations hold for \(\overline{Z}={{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}={\prod }_{j\in {\gamma }_{Z}}{Z}_{j}\).

In both a and b, qubits are at the vertices and the check operators are SP = ∏i∈POi, with O = X, Z, depending on the plaquette P, cf. c The logical operators \(\overline{O}={{{\mathcal{O}}}}_{{\gamma }_{O}}={\prod }_{i\in {\gamma }_{O}}{O}_{i}\) (with O = X, Z) are Pauli strings along noncontractible paths γO, connecting boundaries with O-type SP (a) and/or encircling one with opposite type SP (b). By \({O}^{2}={\mathbb{1}}\), \({{{\mathcal{O}}}}_{{\gamma }_{O}}\) can be deformed into \({{{\mathcal{O}}}}_{\gamma {{\prime} }_{O}}\) via O-type checks (cf. a, dashed).

The above illustrate key features that we shall use. They hold for any nonchiral Abelian TO14,15,16 where again logical operators commute with all SP, run along noncontractible paths that are deformable by check-operator products, and paths for conjugate pairs (such as \(\overline{X}\) and \(\overline{Z}\)) can be chosen to intersect only once. These all have their anyon interpretation14,15,16: the SP eigenvalues label anyon configurations, a logical operator \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }\) drags a corresponding anyon along its path γ, and its algebra \({\overline{O}}^{{\dagger} }{{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }\overline{O}={e}^{2i{\theta }_{OW}}{{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }\) with its conjugate \(\overline{O}\) encodes mutual statistics through the angle θOW.

The surface code drive

with JP real, has structure identical to Eq. (1), suggesting that it exemplifies TTCs in their unperturbed limit. (See also Refs. 7,8,54 for similar constructions.) The Floquet eigenstates \(\left\vert {{\bf{s}}},o\right\rangle\) now form doublets labeled by the \(\overline{O}\) eigenvalue o. By its role being akin to P in TCs, we view \(\overline{O}\) as a generalized symmetry29,30,31. Taking \(\overline{O}={{{\mathcal{X}}}}_{{\gamma }_{X}}\) for concreteness, by \({\overline{O}}^{{\dagger} }{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\overline{O}=-{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\) we can then view the conjugate logical \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\) as order parameter. Unlike Zj for the TC, \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\) is not local, but has 1D support. (Hence \(\overline{O}\), acting on 1D charged objects, is a 1-form symmetry30,31.) \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\) is however local transversally to γZ. It is thus meaningful to consider \(\left\langle {{\bf{s}}},o\right\vert {{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{\gamma ^{{\prime} }_{Z}}\left\vert {{\bf{s}}},o\right\rangle\) at large separation \(d({\gamma }_{Z},{\gamma }_{Z}^{{\prime} })\gg 1\). In this sense, the TO states \(\left\vert {{\bf{s}}},o\right\rangle\) are long-range ordered. By \({\overline{O}}^{{\dagger} }{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\overline{O}=-{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\) and \([{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}},{H}_{0}]=0\), we have

The drive UF0 thus has spatiotemporal features similar to a TC, but generalized to TO via 1-form symmetries. [Drives with symmetry \(\overline{O}={{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\) or \(\overline{O}=i{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}{{{\mathcal{X}}}}_{{\gamma }_{X}}\), with order parameter \({{{\mathcal{X}}}}_{{\gamma }_{X}}\), would be equally valid.] Arising from \({\overline{O}}^{{\dagger} }{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\overline{O}={e}^{2i{\theta }_{OZ}}{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}=-{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\), Eq. (3) originates in surface-code anyons’ mutual semion statistics.

The path choice in \(\overline{O}={{{\mathcal{X}}}}_{{\gamma }_{X}}\), or \({H}_{1}=\frac{\pi }{2}{\sum }_{j\in {\gamma }_{X}}{X}_{j}\), is arbitrary: any of γX’s deformations gives a valid UF0. One may also use a product over paths, \(\overline{O}={\prod }_{{\gamma }_{X}\in {{\Gamma }}}{{{\mathcal{X}}}}_{{\gamma }_{X}}\) with any Γ of odd cardinality; then \(\overline{O}\) anticommutes with \(\overline{Z}\) (and commutes with each SP) hence is a valid \(\overline{X}\). If, as in Fig. 1a, (i) the SP are purely X- or Z-strings (they form a Calderbank-Shor-Steane code52), (ii) each Z-check features an even number of Zj, and (iii) the code has \(\overline{Z}={{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\) with odd-length γZ, then the uniform, and thus path-choice-free, \({H}_{1}=\frac{\pi }{2}{\sum }_{j}{X}_{j}\) translates to such \(\overline{O}\) because \(\exp (-i{H}_{1})\propto {\prod }_{j}{X}_{j}\) commutes with each SP but anticommutes with \(\overline{Z}\).

The features of UF0 motivate the following:

Definition 1

\({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=\exp (-i{H}_{1})\exp (-i{H}_{0})\) is a TTC if (1) it has TO in all its eigenstates \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\); (2) a (smeared) logical operator \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\), along path γ, exists such that, for any \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\) and up to corrections exponentially small in the linear system size, \(\left\langle \psi \right\vert {\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }(mT){\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }(0)\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\) has finite period greater than one as the function of the integer m; (3) these features are robust against local perturbations in H0,1.

As we shall explain, perturbations smear logical operators (and the SP) of TO MBL systems over a lengthscale set by the localization length ξ35. The anyon interpretation, above Eq. (2), now holds for these smeared operators, and it is this smearing that we allow (and indicate by tilde) in the definition. (We have ξ = 0 for UF0.) As TO eigenstates imply that \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\) is deformable to \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma {^\prime} }\), the definition replaces (generalized) long-range order by single-path expectations and the separate requirement of eigenstate TO. By the TO in \(\left\vert {{\bf{s}}},o\right\rangle\) and the period doubling in Eq. (3), properties (1) and (2) are satisfied by UF0 in Eq. (2) for \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }={{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\) and \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle=\left\vert {{\bf{s}}},o\right\rangle\). We require (3) to capture a phase of matter.

Robustness of TTCs via MBL

We next show that the robustness of TO MBL implies that UF0, and its generalizations to other nonchiral Abelian TO (upon suitably replacing SP and \(\overline{O}\)), satisfy (3) in Definition 1. We use the QEC language to treat conventional and TO MBL on the same footing35. A key concept is that of a local unitary \(\widetilde{U}\), i.e., a finite-time evolution with a local Hamiltonian17,50. If Oi is local to site i, then \({\widetilde{O}}_{i}=\widetilde{U}{O}_{i}{\widetilde{U}}^{{\dagger} }\) is quasilocal: in its Pauli-string expansion, operators supported at distance ℓ from i have coefficients decaying exponentially with ℓ.

A system is MBL if the following holds robustly against local perturbations35,43,44,45,46,47: the eigenbasis \(\left\vert {\psi }_{{{\bf{s}}},{{\bf{o}}}}\right\rangle\) of UF satisfies \(\left\vert {\psi }_{{{\bf{s}}},{{\bf{o}}}}\right\rangle=\widetilde{U}\left\vert {{\bf{s}}},{{\bf{o}}}\right\rangle\) where \(\left\vert {{\bf{s}}},{{\bf{o}}}\right\rangle\) are eigenstates of N − k local operators SP (with eigenvalues in vector s) and k logical operators \({\overline{O}}_{j}({{\bf{s}}})\) [with eigenvalues in o, j ∈ {1, …, k}, and k being N-independent] and \(\widetilde{U}\) is a local unitary (set by the details of UF). The s dependence in \({\overline{O}}_{j}({{\bf{s}}})\) arises when it is perturbations that split the logical-subspace degeneracies. As in our examples above, we shall mostly focus on k = 1.

For \({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=\exp (-iH)\) with static 2D Hamiltonian H = ∑PJPSP + δH, with SP for a TO and JP disordered with distribution of width δJ, (pre-thermal) TO MBL is expected for any δH with local terms with couplings of order g ≪ δJ32,33,34,35. (See also Ref. 55 for numerics.) TO MBL is robust in this sense. It is pre-thermal because perturbative arguments39, adapted to TO, suggest that its MBL has thermalization timescale tth longer than exponential in δJ/g. Beyond tth, MBL breaks down via rare regions with nearly uniform JP37. Such regions are unlikely in intermediate-scale systems and may also be eliminated in programmable devices, potentially yielding tth → ∞. Below we focus on times below tth.

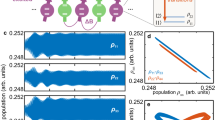

For \({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=\exp (-i{H}_{1})\exp (-i{H}_{0})\) arising upon perturbing UF0 [Eq. (2)], the robustness of TO MBL does not directly follow especially since H1, via \(\frac{\pi }{2}{\sum }_{j\in {\gamma }_{X}}{X}_{j}\), has couplings comparable to δJ. However, akin to TCs9,10,56, by \({\overline{O}}^{2}={\mathbb{1}}\) we have \({U}_{\,{\mbox{F}}\,}^{2}\approx \exp [-i({\sum }_{P}2{J}_{P}{S}_{P}+\delta H)]\) with δH as above, with terms set by those in H0,1. Based on this, we expect TO MBL to be robust also for UF. In Supplementary Notes 1, 2, 3, we corroborate this expectation using numerical simulations.

MBL implies that \(\left\vert {\psi }_{{{\bf{s}}},{{\bf{o}}}}\right\rangle\) are simultaneous eigenstates of UF and \({T}_{P}=\widetilde{U}{S}_{P}{\widetilde{U}}^{{\dagger} }\); these are hence mutually commuting operators. In particular, the TP are (quasi)local integrals of motion. When SP corresponds to TO, these TP are the tLIOMs35. When \(\left\vert {{\bf{s}}},{{\bf{o}}}\right\rangle\) are TO states, then since this cannot change under a local unitary17,50, so are \(\left\vert {\psi }_{{{\bf{s}}},{{\bf{o}}}}\right\rangle\); equivalently, tLIOMs imply TO in all eigenstates, which are all still labeled by anyon configurations s35. (Conversely, LIOMs43,44,45,46,47, e.g., via Sj = Zj or Sj = ZjZj+1, give topologically trivial states.)

A key extra feature in UF0 of Eq. (2) is that \(\overline{O}\) specifies the unperturbed eigenbasis in logical space. Hence, not only is UF0 TO MBL by the disorder in JP, but the eigenbasis for UF arising from UF0 with local perturbations is formed by eigenstates \(\left\vert {\psi }_{{{\bf{s}}},o}\right\rangle\) of the s-independent \(\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}=\widetilde{U}\overline{O}{\widetilde{U}}^{{\dagger} }\). Since the TP and \(\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\) form a complete set of integrals of motion, UF can be expressed using these. The following result implies that this \({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}(\{{T}_{P}\},\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}})\) is a TTC, i.e., that UF0 of Eq. (2) (and its deformations by local perturbations) satisfies (3) in Definition 1:

Proposition 1

If a TO MBL Floquet unitary factorizes as \({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}{e}^{-if(\{{T}_{P}\})}\) with a (smeared) logical operator \(\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\) and an exponentially local function f of tLIOMs TP, then such a factorization is robust and the system is a TTC with \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\) in Definition 1 conjugate to \(\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\). Here, exponentially local f means that in

the cPQR… decay exponentially with the largest distance between the centers of the supports of TQ, TP, TR, ….

The proof is given under Methods. Akin to TCs, the structure \({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}{e}^{-if(\{{T}_{P}\})}\) implies that the Floquet spectrum is organized into eigenstate multiplets with rigid phase patterns5,7,8. Specifically, by o ∈ { − 1, 1}, the spectrum \({e}^{-i{\varepsilon }_{{{\bf{s}}},o}}=o{e}^{-if({{\bf{s}}})}\) displays robust π splitting for each s, i.e., within each doublet.

Proposition 1 takes infinite system size L⊥ transversally to the path γ; otherwise f includes terms proportional to \(\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\) with coefficients decaying exponentially with L⊥/ξ. It is, however, agnostic to the length L∥ of the shortest γ. The TTC, and its π-paired spectrum, thus emerges exactly even for moderate L∥ as long as L⊥/ξ → ∞. (See also Supplementary Note 1.) At the core of this robustness is \({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}(\{{T}_{P}\},\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}})\) not featuring \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\). This is unlike static TO, with \({U}_{{\mbox{F}}0}={e}^{-{H}_{0}}\) whose logical eigenbasis is arbitrary; here MBL implies only \({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}(\{{T}_{P}\},\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}},{\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma })\), where \(\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\) and \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\) enter with coefficients decaying exponentially with L⊥ and L∥, respectively, and thus split spectral degeneracies. TTCs are hence, in a sense, even more robust than static TO: they have their own absolute stability.

Some generalizations

Our TTC construction has a number of immediate generalizations. Firstly, UF0 of Eq. (2) can also be defined for systems with k > 1 logical qubits (e.g., planar surface codes with multiple holes and/or boundaries alternating several segments with X- and Z-type boundary checks). We can then choose \(\overline{O}={\overline{O}}_{1}{\overline{O}}_{2}\ldots {\overline{O}}_{p}\), with logical operators \({\overline{O}}_{j}\), for any subset of p ⩽ k logical qubits. In this case, we find TTC signature in each logical operator conjugate to \(\overline{O}\) and that each 2k-fold multiplet of H0 is π-split into groups of 2k−1 levels. Under MBL, the π splitting is again absolutely stable, while the 2k−1-fold degeneracies are as robust as in static TO MBL.

By suitably generalizing the SP and \(\overline{O}\), the TTCs also generalize to any nonchiral Abelian TO14,15,16; these precisely exhaust the TOs compatible with MBL32,33,34,35. In this way, we can get, e.g., TTC counterparts of ordinary TCs based on any finite Abelian group G6,8.

Holographic TTC–to–TC correspondence

TTCs also illustrate a dynamical generalization of TO with gapped boundaries: TO with MBL boundaries. Gapped boundaries of (clean) 2D TO have been shown to holographically describe (clean) gapped 1D systems, including symmetry broken and symmetry-protected topological phases57,58,59,60,61,62. While the adjective gapped refers to low energies, the correspondence is between operators. It should, therefore, also capture MBL and TCs.

To illustrate this, consider the surface code boundary B in Fig. 2. We start with Eq. (2), with \(\overline{O}=\overline{X}\), and add perturbations, first requiring that they commute with \(\overline{X}\) and with all SP except for the Z-type checks Sj = Z2j−1Z2j along B. Hence, for each bulk s, we can focus on the physics at B. The allowed perturbations are \({\tau }_{1}^{x}={X}_{1}\) and \({\tau }_{j+1}^{x}={X}_{2j}{X}_{2j+1}\) along B, and their products with each other and with the SP. To keep perturbations local, we focus on the \({\tau }_{j}^{x}\) and include them in H1. It is suggestive to denote Sj, already in H0, as \({\tau }_{j}^{z}{\tau }_{j+1}^{z}\) because the \({\tau }_{j}^{z}{\tau }_{j+1}^{z}\) and the \({\tau }_{l}^{x}\) satisfy the same relations as if \({\tau }_{j}^{O}\) were Pauli-O operators at site j58. The \({\tau }_{j}^{z}{\tau }_{j+1}^{z}\) and \({\tau }_{l}^{x}\) are precisely the operators for constructing the \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\) TC UF via Pauli operators \({\tau }_{j}^{O}\). With the \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\) symmetry \({P}_{\tau }={\prod }_{j}{\tau }_{j}^{x}={\prod }_{j\in B}{X}_{j}\) being a valid \(\overline{X}\) for the TO, and mapping order parameters by identifying \({\tau }_{j}^{z}\) with \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\) ending with Z2j−1 at B, we find that the TTC UF, at boundary B, realizes the 1D \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\) TC. In particular, \({T}_{j}=\widetilde{U}{\tau }_{j}^{z}{\tau }_{j+1}^{z}{\widetilde{U}}^{{\dagger} }\) are the LIOMs of the boundary TC. The construction applies also with bulk perturbations, just now with the bulk SP, \(\overline{O}\), and \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\) replaced by TP, \(\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\) and \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\). This holographic correspondence is another unifying perspective on TTCs and TCs.

The boundary checks Sj = Z2j−1Z2j (shown also as red segments) and perturbations X1 (blue dot) and X2jX2j+1 (blue segments) become \({\tau }_{j}^{z}{\tau }_{j+1}^{z}\) and \({\tau }_{l}^{x}\). The symmetry \({P}_{\tau }={\prod }_{j}{\tau }_{j}^{x}\) is a logical \(\overline{X}\) of the TO. Also shown is the assignment \({\tau }_{j+1}^{z}\) to \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_{{\gamma }_{Z}}\) with γZ ending on qubit 2j (dashed) or 2j + 1 (solid vertical line); the two choices differ by a deformation (cf. Fig. 1).

Generalizing this construction, one can also design TO MBL drives that holographically realize other 1D MBL Floquet phases. With suitable nonchiral Abelian TOs, we expect that all 1D symmetry-broken and symmetry-protected topological phases6,25,26,27 can arise this way. It will be interesting to see what insights this perspective offers about these 1D Floquet systems.

Comparisons to some other topological TCs

As mentioned in the Introduction, by their intrinsic 2D TO, which requires no symmetry and supports anyons, our TTCs are distinct from symmetry-protected topological TCs25,26,27,28; their signatures, via \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\) (and \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }\), see below), are robust to arbitrary (not only symmetry-preserving) perturbations, and originate directly from anyonic statistics. TTCs are also distinct from 1D, including Majorana-based, topological TCs25,63,64 as these exist a dimension lower and if they have anyon-like particles, these are bound to defects or boundaries.

The closest relation is to intrinsic 2D TO drives that permute anyon species65,66. As anyon species are distinguished by the type of SP (e.g., X- and Z-type SP in the surface code), the unperturbed form of such drives replaces \(\overline{O}\) in Eq. (2) by a local unitary \({{\mathcal{A}}}\) that permutes nearby SP65,66. Hence, \({{\mathcal{A}}}\) does not commute with the SP, thus the Floquet eigenstates are not \(\left\vert {{\bf{s}}},{{\bf{o}}}\right\rangle\) but their superpositions65,66. Therefore, while such phases may be robust to local perturbations65,66, if they are MBL they do not have the tLIOMs TP we discussed.

Signatures of TTCs

While \({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}{e}^{-if(\{{T}_{P}\})}\) implies a TTC, the observable \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }=\widetilde{U}{{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }{\widetilde{U}}^{{\dagger} }\) in Definition 1 depends on \(\widetilde{U}\), hence is difficult to access experimentally. It is easier to access its bare counterpart \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }\). We next discuss two signatures in terms of this \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }\):

Proposition 2

If UF is an MBL TTC, then (i) in any of its eigenstates \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\), and for \(d(\gamma,\gamma {^\prime} )\gg \xi\) separation, \(\left\langle \psi \right\vert {{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }(mT){{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma {^\prime} }(0)\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\) has finite period greater than one as the function of the integer m and decays exponentially with the sum \(| \gamma |+| \gamma {^\prime} |\) of the lengths of γ and \(\gamma {^\prime}\), but it does not decay with \(d(\gamma,\gamma {^\prime} )\). Furthermore, (ii), this TTC signal emerges also for \(\gamma {^\prime}=\gamma\) with m ≫ 1 and upon averaging over eigenstates and/or disorder.

We support this claim in Methods using analytic arguments and further substantiate it numerically in Supplementary Notes 2 and 3. This result is a dynamical, time-crystalline, form of the perimeter law, a fundamental feature of TO MBL32,33, originating in lattice gauge theories40,41. In TO MBL, Wilson loops \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\partial A}\) (e.g., a Pauli-Z string equal to the product of all Z-type SP in an area A, thus running along the perimeter ∂A) have eigenstate expectation \(\left\langle \psi \right\vert {{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\partial A}\left\vert \psi \right\rangle \propto \exp (-\lambda | \partial A| )\) with λ ∝ ξ (with all lengths in units of lattice spacing). By contrast, in a topologically trivial phase the expectation decays much faster, exponentially with the area ∣A∣. In Proposition 2, A is in spacetime, with γ (at time mT) and \(\gamma {^\prime}\) (at time zero) being its boundaries. The perimeter law has the same status for TO as long-range correlations do for spontaneous symmetry breaking. Hence the TTC perimeter law in Proposition 2 is the TO counterpart of the signatures of TCs’ spatiotemporal order.

For the \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }\) to give TTC signal of appreciable magnitude as N → ∞, one needs γ to have N-independent minimal length L∥. While this can be achieved via quasi-1D N → ∞ limits, a 2D N → ∞ limit is also possible, e.g., in systems topologically equivalent to a cylinder (such as the example in Fig. 1b). We emphasize that keeping L∥ finite does not spoil TTC features, as follows from the TTCs’ absolute stability.

To detect the TTC perimeter law one must also bypass not having experimental access to eigenstates \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\). For \(\gamma {^\prime}=\gamma\), one may use quantum typicality67,68: using experimentally accessible highly-entangled states56, one may probe, up to errors exponentially small in N, \(\left\langle \psi \right\vert {{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }(mT){{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }(0)\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\) averaged over all eigenstates. One may also use that, for strong MBL (i.e., small ξ), \(\left\vert {\psi }_{{{\bf{s}}},{{\bf{o}}}}\right\rangle\) deviates only slightly from the experimentally accessible \(\left\vert {{\bf{s}}},{{\bf{o}}}\right\rangle\), and thus the desired expectation is approximated by \(\left\langle {{\bf{s}}},{{\bf{o}}}\right\vert {{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }[(m+n)T]{{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma {^\prime} }(nT)\left\vert {{\bf{s}}},{{\bf{o}}}\right\rangle\) for sufficiently large n. Supplementary Notes 2 and 3 include further details and numerics on both approaches. Recent experimental results on our proposed TTCs42 are promising for the feasibility of detecting the TTC perimeter law.

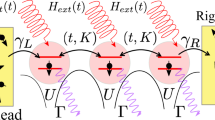

TTC in Google Sycamore

The surface code ground states, anyons, and logical operators have seen recent Google Sycamore realizations49,69 and the same platform has been also used for realizing TCs56. (See also Ref. 70 for an IBM realization.) We now describe how Sycamore can be used to create and detect a TTC. We divide Sycamore’s square grid of qubits into data qubits and measure qubits (Fig. 3a)21,49. Data qubits are to be evolved under UF; measure qubits facilitate the desired multi-qubit gates. To generate \({e}^{-i{J}_{P}{S}_{P}}\) with Z-type SP, one may use the standard approach (Fig. 3b)52. For X-type SP, one conjugates the above by \(\sqrt{Y}\) on data qubits, using \(\sqrt{Y}Z\sqrt{{Y}^{{\dagger} }}=X\). For \(\exp (-i{H}_{1})\), one applies suitable single-qubit rotations on data qubits; e.g., using \({H}_{1}={\sum }_{j}[\pi /2+{g}_{j}^{(X)}]{X}_{j}+{g}_{j}^{(Y)}{Y}_{j}+{g}_{j}^{(Z)}{Z}_{j}\), with \({g}_{j}^{(\alpha )}\ll \delta J\) one may study the robustness of TTCs and the TTC perimeter law, as illustrated in Supplementary Notes 2 and 3. All the ingredients, namely the single-qubit rotations, \(\sqrt{Y}\), and CNOT are available in Sycamore48,56. Detecting TTCs can proceed, e.g., via the interferometric protocol demonstrated in Ref. 69. The decoherence rates are also compatible with TCs56 and we expect the same for TTCs.

a A Sycamore device, with N = 25 data qubits (gold), can realize a system akin to Fig. 1a. (Measure qubits are in blue; the figure is redrawn based on Ref. 49.) Dark (light) blue shaded areas mark Z-type (X-type) checks SP. b The evolution \({U}_{{S}_{P}}^{(Z)}=\exp (-i{J}_{P}{\prod }_{j\in P}{Z}_{j})\) on four data qubits. The surrounded measure qubit starts in \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\); the CNOTs couple to the data qubits. The \({U}_{{S}_{P}}^{(X)}\) evolution arises via conjugating by \(\sqrt{Y}\) on the data qubits.

Discussion

We have defined TTCs and showed that, combined with MBL, they form a (pre-thermal) dynamical phase. Higher-form symmetries and QEC codes offer complementary ways to link ordinary TCs to TTCs, while the holographic correspondence between TTCs and their MBL boundaries offers a reverse link to ordinary TCs. Logical operators serve both as symmetries and as order parameters for TTCs. This leads to interesting interplay, both between spectral pairing patterns and topological degeneracies, and also between MBL and the nonlocality of these operators, the latter manifested in the TTC perimeter law.

The most favorable settings for realizing TTCs feature MBL with short localization lengths (strong MBL). This allows the suppression of finite-size corrections already in moderate-sized systems, and the detection of the TTC perimeter law for an appreciable range of order parameter path lengths. Studying these settings is particularly well suited for programmable quantum processors, such as those featured in the recent, intermediate-scale, demonstration of our proposed TTCs42, or the Google Sycamore device48 which also has all the ingredients for creating such a TTC.

Methods

Robustness of the TTC drive structure

Here we prove Proposition 1, using considerations analogous to those for establishing TCs’ absolute stability7. The operator \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\) below is the one in Definition 1, taken to be conjugate to \(\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\), i.e., \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}=-\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}{\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\). The proof hinges on the following: (i) the object \({\theta }_{\gamma }={U}_{\,{\mbox{F}}\,}^{{\dagger} }{\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }{U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}{\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\), illustrated in Fig. 4, is quasilocal transversally to γ; and (ii) it is independent of the choice of γ among the paths deformable into each other.

The operators are smeared around the paths γ (solid line) and \(\gamma {^\prime}\) (dashed line), respectively. The relation \({\theta }_{\gamma }={\theta }_{\gamma {^\prime} }\) that we establish implies \({\theta }_{\gamma }\propto {\mathbb{1}}\), which in turn is shown to imply \({\theta }_{\gamma }=\pm {\mathbb{1}}\).

The transversal quasilocality of θγ follows from UF being a local unitary [it is a finite-time evolution with a local H(t)] and from \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\) being quasilocal transversally to γ. To show \({\theta }_{\gamma }={\theta }_{\gamma {^\prime} }\), we recall that \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }\) (along path γ) can be deformed into \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma {^\prime} }\) (along path \(\gamma {^\prime}\)) by multiplying with a suitable SP product (cf. Fig. 1). Hence \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\) can similarly be deformed into \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma {^\prime} }\) using a suitable TP product. Now using the commutation \([{T}_{P},{U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}]=[{T}_{P},{{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }]=0\) and \({T}_{P}^{2}={\mathbb{1}}\), we find \({\theta }_{\gamma }={\theta }_{\gamma {^\prime} }\).

For separations \(d(\gamma,\gamma {^\prime} )\gg \xi\), the path γ features in the support of \({\theta }_{\gamma {^\prime} }\) only through Pauli strings that contribute to \({\theta }_{\gamma {^\prime} }\) with coefficients exponentially small in \(d(\gamma,\gamma {^\prime} )/\xi\), and vice versa for \(\gamma {^\prime}\) and θγ. For this to be consistent with \({\theta }_{\gamma }={\theta }_{\gamma {^\prime} }\) we must have \({\theta }_{\gamma }=c{\mathbb{1}}\) (with c a phase, by θγ being unitary) up to corrections exponentially small in L⊥/ξ, with L⊥ the system size transversally to γ. (All our statements below hold up to such corrections.) By \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }^{2}={\mathbb{1}}\), we have \({\theta }_{\gamma }{\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }={U}_{\,{\mbox{F}}\,}^{{\dagger} }{\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }{U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\), and thus \({\theta }_{\gamma }^{2}={({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}^{{\dagger} }{\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }{U}_{{{\rm{F}}}})}^{2}={\mathbb{1}}\). Hence \({\theta }_{\gamma }=\pm {\mathbb{1}}\). This holds for any \({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}(\{{T}_{P}\},\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}})\). As perturbations change θγ continuously, if \({\theta }_{\gamma }=-{\mathbb{1}}\) then this persists throughout the MBL phase.

The result \({\theta }_{\gamma }=\pm {\mathbb{1}}\) implies that \({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}(\{{T}_{P}\},\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}})\) either commutes with \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\) or anticommutes with it. By \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}=-\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}{\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\), \([{\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma },{T}_{P}]=0\), and \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}}^{2}={\mathbb{1}}\), we thus find that UF is either proportional to \(\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\) or independent of \(\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\). The form \({U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}{e}^{-if(\{{T}_{P}\})}\) is the generic structure for UF proportional to \(\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\), where the exponentially local nature of f follows from the local unitarity of UF. This factorization is thus robust throughout the MBL phase.

For \({\theta }_{\gamma }=-{\mathbb{1}}\), we have \({U}_{\,{\mbox{F}}\,}^{{\dagger} }{\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }{U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=-{\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\) and hence \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }(mT)= {(-1)}^{m}{\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\), and thus \(\left\langle \psi \right\vert {\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }(mT){\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }(0)\left\vert \psi \right\rangle={(-1)}^{m}\). Considering also the TO the tLIOMs TP imply in all eigenstates, the system is a TTC.

TTC perimeter law

We consider, in eigenstate \(\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\), the correlator

where we inserted a Floquet eigenbasis \(\left\vert \beta \right\rangle\) with eigenvalues \({e}^{-i{\varepsilon }_{\beta }}\). We first focus on \(d(\gamma,\gamma ^{\prime} )\gg \xi\) and show that, analogously to TCs7, in this limit only \(\left\vert \beta \right\rangle=\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert \beta \right\rangle={\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma }\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle \sim {\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma ^{\prime} }\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\) can contribute. To this end, we expand \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\) in terms of operators \({T}_{P},{T}_{P}^{x},{\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma },\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\), where \({T}_{P}^{x}\) anticommutes with TP (and hence flips its eigenvalue in \(\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\)). As \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\) is local transversally to \({\gamma }^{({\prime} )}\), the operator \(\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\) cannot contribute for L⊥ ≫ ξ (the limit we assume henceforth). Similarly, \({T}_{P}^{(x)}\) can contribute appreciably only if their bare counterparts \({S}_{P}^{(x)}\) have their entire support within ~ ξ from \({\gamma }^{({\prime} )}\).

We write \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}={{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{0{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}+{{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{1{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}+{{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{x{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\), where \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{0{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\) is a linear combination of various ∏PTP, \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{1{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\) is that of various \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}{\prod }_{P}{T}_{P}\), and \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{x{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\) is similar but with the product featuring at least one \({T}_{P}^{x}\). By the above locality considerations, \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{{\gamma }^{({\prime}) }}\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\) have the same TP eigenvalues for \(d(P,{\gamma }^{({\prime} )})\gg \xi\), up to corrections exponentially small in \(d(P,\gamma^{(\prime)} )/\xi\) (which we neglect henceforth). Hence, \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{x\gamma }\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\) is orthogonal to \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{{\gamma }^{{\prime} }}\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\) and vice versa, thus \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{x{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\) can be neglected in Eq. (5).

The only appreciable contributions are via \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{0{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\) and \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{1{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\). Since \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\) flips the \(\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\) eigenvalue in \(\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\), there are no cross-terms between \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{0{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\) and \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{1{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\). By \({U}_{\,{\mbox{F}}\,}^{{\dagger} }{{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{0{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}{U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}={{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{0{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\) and \({U}_{\,{\mbox{F}}\,}^{{\dagger} }{{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{1\gamma }{U}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=-{{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{1\gamma }\), we thus get

with \({c}_{j{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}^{(\alpha )}=\left\langle \alpha \right\vert {\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}^{\,\,j}{{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{j{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\), where we used \({\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}^{2}={\mathbb{1}}\). The period doubling, in the second term in Eq. (6), is the claimed time-crystalline signature.

As the contributions from \({\gamma }^{({\prime} )}\) factorize in each term, the signal does not decay with \(d(\gamma,\gamma {^\prime} )\), as claimed. The perimeter law follows from estimating \(| {c}_{1{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}^{(\alpha )}|\). To this end, we view the expansion of \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\) in \({T}_{P},{T}_{P}^{x},{\widetilde{{{\mathcal{W}}}}}_{\gamma },\widetilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\), as one in an orthogonal basis under the scalar product Tr(A†B)/DH where DH is the Hilbert space dimension. As MBL provides no structure below the scale ξ, all the \(\sim {4}^{| {\gamma }^{({\prime} )}| \xi }\) terms (with \(| {\gamma }^{({\prime} )}|\), ξ measured in units of lattice spacing) that contribute appreciably to \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\) have expansion coefficient ai with roughly the same ∣ai∣2, with ∑i∣ai∣2 = 1 by \({{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}^{2}={\mathbb{1}}\). Hence \(| {a}_{i}{| }^{2} \sim {4}^{-| {\gamma }^{({\prime} )}| \xi }\). By the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, \(| {c}_{1{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}^{(\alpha )}{| }^{2}\leqslant \left\langle \alpha \right\vert {{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{1{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}^{2}\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\). Due to MBL, no eigenstate \(\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\) is special; hence we can estimate \(| {c}_{1{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}^{(\alpha )}{| }^{2}\lesssim \,{\mbox{Tr}}\,\,{{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{1{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}^{2}/{D}_{H}={\sum}^{{\prime} }_{i}| {a}_{i}| ^{2}\), where \(\sum {^\prime}\) sums over the \(\sim {2}^{| {\gamma }^{({\prime} )}| \xi }\) terms that contribute appreciably to \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{1{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}\). Using \(| {a}_{i}{| }^{2} \sim {4}^{-| {\gamma }^{({\prime} )}| \xi }\), we thus find \(| {c}_{1{\gamma }^{({\prime} )}}^{(\alpha )}| \lesssim {2}^{-| {\gamma }^{({\prime} )}| \xi /2}\). The time-crystalline signal thus decays as \(\sim {2}^{-\xi (| \gamma |+| {\gamma }^{{\prime} }| )/2}\).

We next consider \(\gamma=\gamma {^\prime}\). Now \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}_{x\gamma }\) does not cancel and leads to terms \(\sim {e}^{i({\varepsilon }_{\alpha }-{\varepsilon }_{\beta })m}\), with \(\left\vert \beta \right\rangle\) via the \({T}_{P}^{x}\) that can appreciably contribute. For a given \(\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\), these are Dγ ~ 2∣γ∣ξ random phases, each with coefficient \(| \left\langle \alpha \right\vert {{{\mathcal{W}}}}_{\gamma }\left\vert \beta \right\rangle {| }^{2} \sim 1/{D}_{\gamma }\), dephasing into a background \(\sim 1/\sqrt{{D}_{\gamma }}\). For a given \(\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\), this increasingly dominates the ~ (−1)m/Dγ time-crystal signal upon increasing ∣γ∣ξ.

The eigenstate average

however, has the time-crystal signal [arising from the \(\left\vert \beta \right\rangle\) in Eq. (5) with \({e}^{i({\varepsilon }_{\alpha }-{\varepsilon }_{\beta })m}={(-1)}^{m}\), present for each \(\left\vert \alpha \right\rangle\) by the π spectral pairing] preserved at strength ~ 1/Dγ, but has an increasing number of random phases upon increasing m (i.e., upon resolving splittings from increasingly distant LIOMs’ interactions). This leads to a power-law decay47 of the background towards its long-time magnitude \(\sim 1/\sqrt{{D}_{H}}={2}^{-N/2}\), well below the ~ 1/Dγ time-crystal signal strength. This emergence of the time-crystal signal for m ≫ 1 is limited by the timescale for resolving exponentially small (in L⊥/ξ) corrections to the π spectral pairing and by the thermalization time. The number of random phases can be further increased, and hence the background suppression can be further enhanced, by averaging over disorder.

Data availability

The datasets for the plots in the Supplementary Information are available upon request.

Code availability

The codes for our simulations in the Supplementary Information are available upon request.

References

Wilczek, F. Quantum time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 160401 (2012).

Shapere, A. & Wilczek, F. Classical time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 160402 (2012).

Watanabe, H. & Oshikawa, M. Absence of quantum time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 251603 (2015).

Else, D. V., Bauer, B. & Nayak, C. Floquet time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 090402 (2016).

Khemani, V., Lazarides, A., Moessner, R. & Sondhi, S. L. Phase structure of driven quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 250401 (2016).

von Keyserlingk, C. W. & Sondhi, S. L. Phase structure of one-dimensional interacting Floquet systems. II. Symmetry-broken phases. Phys. Rev. B 93, 245146 (2016).

von Keyserlingk, C. W., Khemani, V. & Sondhi, S. L. Absolute stability and spatiotemporal long-range order in Floquet systems. Phys. Rev. B 94, 085112 (2016).

Khemani, V., von Keyserlingk, C. W. & Sondhi, S. L. Defining time crystals via representation theory. Phys. Rev. B 96, 115127 (2017).

Yao, N. Y., Potter, A. C., Potirniche, I.-D. & Vishwanath, A. Discrete time crystals: Rigidity, criticality, and realizations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 030401 (2017).

Else, D. V., Bauer, B. & Nayak, C. Prethermal phases of matter protected by time-translation symmetry. Phys. Rev. X 7, 011026 (2017).

Fleishman, L. & Anderson, P. W. Interactions and the Anderson transition. Phys. Rev. B 21, 2366–2377 (1980).

Gornyi, I. V., Mirlin, A. D. & Polyakov, D. G. Interacting electrons in disordered wires: Anderson localization and low-t transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 206603 (2005).

Basko, D. M., Aleiner, I. L. & Altshuler, B. L. Metal–insulator transition in a weakly interacting many-electron system with localized single-particle states. Ann. Phys. 321, 1126–1205 (2006).

Kitaev, A. Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. 303, 2–30 (2003).

Kitaev, A. Anyons in an exactly solved model and beyond. Ann. Phys. 321, 2–111 (2006).

Levin, M. A. & Wen, X.-G. String-net condensation:a physical mechanism for topological phases. Phys. Rev. B 71, 045110 (2005).

Chen, X., Gu, Z.-C. & Wen, X.-G. Local unitary transformation, long-range quantum entanglement, wave function renormalization, and topological order. Phys. Rev. B 82, 155138 (2010).

Chen, X., Gu, Z.-C., Liu, Z.-X. & Wen, X.-G. Symmetry protected topological orders and the group cohomology of their symmetry group. Phys. Rev. B 87, 155114 (2013).

Mesaros, A. & Ran, Y. Classification of symmetry enriched topological phases with exactly solvable models. Phys. Rev. B 87, 155115 (2013).

Dennis, E., Kitaev, A., Landahl, A. & Preskill, J. Topological quantum memory. J. Math. Phys. 43, 4452–4505 (2002).

Fowler, A. G., Mariantoni, M., Martinis, J. M. & Cleland, A. N. Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 86, 032324 (2012).

Caio, M. D., Cooper, N. R. & Bhaseen, M. J. Quantum quenches in Chern insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 236403 (2015).

Wilson, J. H., Song, J. C. & Refael, G. Remnant geometric hall response in a quantum quench. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 235302 (2016).

Kitagawa, T., Berg, E., Rudner, M. & Demler, E. Topological characterization of periodically driven quantum systems. Phys. Rev. B 82, 235114 (2010).

von Keyserlingk, C. W. & Sondhi, S. L. Phase structure of one-dimensional interacting Floquet systems. I. Abelian symmetry-protected topological phases. Phys. Rev. B 93, 245145 (2016).

Roy, R. & Harper, F. Abelian Floquet symmetry-protected topological phases in one dimension. Phys. Rev. B 94, 125105 (2016).

Potter, A. C., Morimoto, T. & Vishwanath, A. Classification of interacting topological Floquet phases in one dimension. Phys. Rev. X 6, 041001 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Digital quantum simulation of Floquet symmetry-protected topological phases. Nature 607, 468–473 (2022).

Nussinov, Z. & Ortiz, G. A symmetry principle for topological quantum order. Ann. Phys. 324, 977–1057 (2009).

Gaiotto, D., Kapustin, A., Seiberg, N. & Willett, B. Generalized global symmetries. JHEP 2015, 172 (2015).

McGreevy, J. Generalized symmetries in condensed matter. Annu. Rev. Cond. Mat. Phys. 14, 57–82 (2023).

Huse, D. A., Nandkishore, R., Oganesyan, V., Pal, A. & Sondhi, S. L. Localization-protected quantum order. Phys. Rev. B 88, 014206 (2013).

Bauer, B. & Nayak, C. Area laws in a many-body localized state and its implications for topological order. J. Stat. Mech. 2013, P09005 (2013).

Potter, A. C. & Vishwanath, A. Protection of topological order by symmetry and many-body localization, http://arxiv.org/abs/1506.00592 arXiv:1506.00592.

Wahl, T. B. & Béri, B. Local integrals of motion for topologically ordered many-body localized systems. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033099 (2020).

Chandran, A., Pal, A., Laumann, C. R. & Scardicchio, A. Many-body localization beyond eigenstates in all dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 94, 144203 (2016).

Roeck, W. D. & Imbrie, J. Z. Many-body localization: stability and instability. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 375, 20160422 (2017).

Potirniche, I.-D., Banerjee, S. & Altman, E. Exploration of the stability of many-body localization in d > 1. Phys. Rev. B 99, 205149 (2019).

Gopalakrishnan, S. & Huse, D. A. Instability of many-body localized systems as a phase transition in a nonstandard thermodynamic limit. Phys. Rev. B 99, 134305 (2019).

Wilson, K. G. Confinement of quarks. Phys. Rev. D 10, 2445 (1974).

Kogut, J. B. An introduction to lattice gauge theory and spin systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 51, 659 (1979).

Xiang, L. et al. Long-lived topological time-crystalline order on a quantum processor, Nat. Commun. 15, 8963 (2024).

Serbyn, M., Papić, Z. & Abanin, D. A. Local conservation laws and the structure of the many-body localized states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 127201 (2013).

Huse, D. A., Nandkishore, R. & Oganesyan, V. Phenomenology of fully many-body-localized systems. Phys. Rev. B 90, 174202 (2014).

Chandran, A., Kim, I. H., Vidal, G. & Abanin, D. A. Constructing local integrals of motion in the many-body localized phase. Phys. Rev. B 91, 085425 (2015).

Ros, V., Mueller, M. & Scardicchio, A. Integrals of motion in the many-body localized phase. Nucl. Phys. B 891, 420–465 (2015).

Serbyn, M., Papić, Z. & Abanin, D. A. Quantum quenches in the many-body localized phase. Phys. Rev. B 90, 174302 (2014).

Arute, F. et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 574, 505–510 (2019).

Google Quantum AI Suppressing quantum errors by scaling a surface code logical qubit. Nature 614, 676–681 (2023).

Bravyi, S., Hastings, M. B. & Verstraete, F. Lieb-Robinson bounds and the generation of correlations and topological quantum order. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 050401 (2006).

Gottesman, D. Stabilizer codes and quantum error correction, Ph.D. thesis, California Institute of Technology (1997).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information: 10th Anniversary Edition, 10th ed. (Cambridge University Press, USA, 2011).

Bomantara, R. W. Quantum repetition codes as building blocks of large-period discrete time crystals. Phys. Rev. B 104, L180304 (2021).

Bomantara, R. W. Nonlocal discrete time crystals in periodically driven surface codes. Phys. Rev. B 104, 064302 (2021).

Venn, F., Wahl, T. B. & Béri, B. Many-body-localization protection of eigenstate topological order in two dimensions, Phys. Rev. B 110, 165150 (2024).

Mi, X. et al. Time-crystalline eigenstate order on a quantum processor. Nature 601, 531–536 (2022).

Severa, P. (Non-)Abelian Kramers-Wannier duality and topological field theory. JHEP 2002, 049–049 (2002).

Ho, W. W., Cincio, L., Moradi, H., Gaiotto, D. & Vidal, G. Edge-entanglement spectrum correspondence in a nonchiral topological phase and Kramers-Wannier duality. Phys. Rev. B 91, 125119 (2015).

Aasen, D., Mong, R. S. K. & Fendley, P. Topological defects on the lattice: I. The Ising model. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 49, 354001 (2016).

Ji, W. & Wen, X.-G. Categorical symmetry and noninvertible anomaly in symmetry-breaking and topological phase transitions. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033417 (2020).

Lichtman, T., Thorngren, R., Lindner, N. H., Stern, A. & Berg, E. Bulk anyons as edge symmetries: Boundary phase diagrams of topologically ordered states. Phys. Rev. B 104, 075141 (2021).

Moradi, H., Moosavian, S. F. & Tiwari, A. Topological holography: Towards a unification of Landau and beyond-Landau physics. SciPost Phys. Core 6, 066 (2023).

Giergiel, K., Dauphin, A., Lewenstein, M., Zakrzewski, J. & Sacha, K. Topological time crystals. New J. Phys. 21, 052003 (2019).

Chew, A., Mross, D. F. & Alicea, J. Time-crystalline topological superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 096802 (2020).

Po, H. C., Fidkowski, L., Vishwanath, A. & Potter, A. C. Radical chiral Floquet phases in a periodically driven Kitaev model and beyond. Phys. Rev. B 96, 245116 (2017).

Potter, A. C. & Morimoto, T. Dynamically enriched topological orders in driven two-dimensional systems. Phys. Rev. B 95, 155126 (2017).

Popescu, S., Short, A. J. & Winter, A. Entanglement and the foundations of statistical mechanics. Nat. Phys. 2, 754–758 (2006).

Goldstein, S., Lebowitz, J. L., Tumulka, R. & Zanghì, N. Canonical typicality. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 050403 (2006).

Satzinger, K. J. et al. Realizing topologically ordered states on a quantum processor. Science 374, 1237–1241 (2021).

Frey, P. & Rachel, S. Realization of a discrete time crystal on 57 qubits of a quantum computer. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm7652 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the ERC Starting Grant No. 678795 TopInSy. We also acknowledge support through the Royal Society Research Fellows Enhanced Research Expenses 2021 RF\ERE\210299 and EPSRC ERC underwrite grant EP/X025829/1 (TBW), the Koshland Fellowship at the Weizmann Institute of Science (BH), and the EPSRC grant EP/V062654/1 (BB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BB originated the project and conceptualized the QEC, higher-form symmetry, and holographic perspectives. BH and BB developed the unperturbed examples; TBW and BB developed the definitions, propositions, and proofs. TBW performed all numerical work. BB wrote the manuscript with input from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks David Long, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wahl, T.B., Han, B. & Béri, B. Topologically ordered time crystals. Nat Commun 15, 9845 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54086-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54086-4