Abstract

Liquid crystal networks (LCN) have attracted surging interest as extraordinary energy-dissipation materials owning to their unique dissipation mechanism based on the re-orientation of mesogens. However, how to integrate high Young’s modulus, good dissipation efficiency and wide effective damping temperature range in energy-dissipation LCN remains a challenge. Here, we report a strategy to resolve this challenge by fabricating robust energy-dissipation liquid crystal semi-interpenetrating polymer network (LC-semi-IPN) consisting crystalline LC polymers (c-LCP). LC-semi-IPN demonstrates a superior synergistic performance in both mechanical and energy-dissipation properties, surpassing all currently reported LCNs. The crystallinity of c-LCP endows LC-semi-IPN with a substantial leap in Young’s modulus (1800% higher than single network). The chain reptation of c-LCP also promotes an enhanced dissipation efficiency of LC-semi-IPN by 200%. Moreover, its effective damping temperature reaches up to 130 °C, which is the widest reported for LCNs. By leveraging its exceptional synergistic performance, LC-semi-IPN can be further utilized as a functional architected structure with exceptional energy-dissipation density and deformation-resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Developing high-performance energy-dissipation materials has always been a research hotspot for absorbing impacts and eliminating unwanted vibration, especially in the fields suffering from the damage of impacts and vibration, such as vehicles, aerospace, electronic devices, and safety equipment1,2,3,4,5. Liquid crystal network (LCN) is a kind of crosslinked polymer network in combination with anisotropic order of liquid crystals and elastic properties of polymer network6,7,8. Its unique “soft elasticity” property endows LCN with distinctive energy-dissipation mechanism (Fig. 1a), which enables the applied strain energy to be dissipated at a relatively constant stress through the re-orientation of its molecular order9,10,11,12. Moreover, distinct from other ordinary polymers, LCN demonstrates not one but two phase transition, the glass transition and the LC-isotropic phase transition, both of which would lead to significant critical fluctuations and enable LCNs with a effective damping temperature range (the loss factor tan δ > 0.3) between glass transition and LC-isotropic phase transition9,11. Compared with other ordinary polymers, LCN also exhibits extraordinary rate-dependent mechanical and energy-dissipation behaviors via the relaxation dynamics of network chains, indicating its enhanced dissipation performance over a wide range of loading rates9,13,14,15.

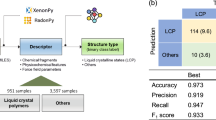

a Schematic illustrating structure of single liquid crystal network and its soft elasticity, which could dissipate energy by the re-orientation of mesogens. b Schematic illustrating structure of LC-semi-IPN, which could dissipate energy by synergistic effect of soft elasticity and chain reptation. c Schematic illustrating the synergistic optimisation of energy-dissipation ability and mechanical performance in LC-semi-IPN, as well as its stability due to π-π interaction. d The Young’s modulus and effettive temperature range (the loss factor tan δ > 0.3) of LC-semi-IPN, compared with other reported LCNs (see Supplementary Table 3 for data).

Owing to its remarkable energy-dissipation performance, LCN has attracted surging interest. The pioneering researches about the energy-dissipation behaviors of LCNs were conducted by Terentjev et al., who firstly reported the siloxane backbone-based side-chain LCNs as potential dissipation materials and demonstrated the power law dependence of modulus and frequency within side-chain LCN materials11,12. In 2015, a feasible main-chain LCN fabrication method based on thiol-acrylate Michael addition was developed by Bowman et al. and researches about the main-chain LCN system have become a hotspot subsequently16,17,18,19,20,21. The main-chain LCNs showed a superior performance in attenuating vibration and damping impact than commercial damping materials10,22,23. Utilizing 3D printing technology, a series of LCN forms and bulk LCN were fabricated, all of which exhibited superior energy-dissipation ability compared with non-LC materials9,24,25. To explore light-weight and high energy-dissipation metamaterials, researchers also constructed LCN-based architected materials with rate-dependent nonlinear energy-dissipation behaviors13. Coupled with viscoelastic dissipation of LCN and snap buckling of multistable structures, these architected materials exhibited a higher energy-absorption density than the poly(dimethylsiloxane)-based (PDMS-based) structure at higher strain rates.

However, it remains a critical challenge to synergistically optimize their energy-dissipation abilities and mechanical performance. Generally, apart from a remarkable energy-dissipation ability, ideal energy-dissipation materials also require favorable mechanical properties, including high modulus, strength and toughness26,27,28. Whereas, previously reported energy-dissipation LCNs are very soft materials, and thus the poor mechanical performance of LCNs hinders their bearing capacity and lifespan during usage, restricting their practical applications10,15,21,29,30. In fact, the similar conflict exists among almost all energy-dissipation materials26,31,32. Even though few approaches have been proposed to develop materials with both improved dissipation and mechanical performance26,33,34,35,36,37, effective strategies to resolve the conflict in LCNs still remain blank. In addition, little research has been done to broaden the effective damping temperature range of LCNs, which is vital for their valid performance in diverse practical conditions.

Here, we bring forth a solution by properly designed liquid crystal semi-interpenetrating polymer network (LC-semi-IPN) containing crystalline linear LC polymers (Figs. 1b and 1c). Semi-IPN is the network composed of one linear polymer and another crosslinked network, where intermolecular entanglement and interpenetration facilitate enforced miscibility among two components, thereby enabling it with combined benefits of these two individual polymer components38,39,40,41,42,43. Semi-IPNs also have shown superiority in the damping field, as the increased internal chain friction between linear polymers and crosslinked network via chain repation would promote to dissipate more energy39,40,44,45,46. However, the damping abilities of LC-semi-IPN have not been explored yet, even a few approaches based on LC-IPNs for mechanical enhancement were previously reported47,48. To take advantages of the promising damping abilities of semi-IPN in the field of LCN, appropriate design is essential. In consideration of intercomponent compatibility and stability of LC-semi-IPN, we recommend the linear polymers ought to be liquid crystal polymers (LCP) with similar mesogens to LCN matrix, instead of conventional non-LC linear polymers. Even though reported semi-IPNs demonstrate enhanced damping abilities, their mechanical properties have usually not been significantly improved. To achieve synergistic enhancement of Young’s modulus, we propose to utilize crystalline LCP (c-LCP) instead of viscous LCP without crystallization, attribute to its high modulus relative to non-crystalline conventional LCPs49,50,51,52.

As we had envisioned, the designed LC-semi-IPN shows tremendous improvements in mechanical performance and energy-dissipation ability. The c-LCP induces the crystallization, and thus endows LC-semi-IPN with an 18-fold higher Young’s modulus (~16 MPa) than that of original LCN. Compared with single liquid crystal network, energy-dissipation efficiency of LC-semi-IPN is 200% higher in compress tests. Notably, LC-semi-IPN exhibits the widest effective damping temperature range (the loss factor tan δ > 0.3, about 130 °C) in the field of LCNs. Its overall performance of temperature range and Young’s modulus is superior to all currently LCNs (Fig. 1d). Moreover, over a wide range of strain rates, LC-semi-IPN has an enhanced Young’s modulus and dissipates much more energy than LCN. The falling steel ball test also verifies its practical abilities in absorbing shock energy and protecting fragile items from impact. Furthermore, the architected material based on LC-semi-IPN, in contrast to the LCN-based structure which fails to recover its original shape, could recover its original shape and exhibit great energy-dissipation performance after repeated tests, indicating its favorable energy-dissipation ability, deformation-resistance and reusability.

Results

Design and fabrication of LC-semi-IPNs

We synthesize the crystalline linear liquid crystal polymer based on facile thiol-acrylate Michael addition. Akyl spacers have been demonstrated as an efficient component to provide polymer chains with improved crystallization ability and increase the modulus of polymers53. Herein, we synthesized the c-LCP based on 1, 3-dimercaptopropane (dithiol spacers), and a commercial diacrylate mesogen with longer alkyl spacers (RM82) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1). In case of the possible intermolecular reaction between the c-LCP and LCN matrix, the c-LCP polymer chains should not be reactive. We first synthesized thiol-ended c-LCP by using RM82 and excess 1, 3-dimercaptopropane. Then, we utilized methyl methacrylate (MMA) to react with the thiol-ended c-LCP polymer chain, avoiding its possible reaction with the LCN matrix.

a The components to fabricate c-LCP, (i) the first step is to synthesize thiol-ended c-LCP, and (ii) the second step is reacting c-LCP with MMA to avoid the reaction between c-LCP and LCN matrix. b The components to fabricate the LCN matrix. c XRD curves of LCN, LC-semi-IPN, and c-LCP. d XRD curves of LC-semi-IPN re-crystalized at different days after reheating. e DSC curves of LCN, LC-semi-IPN, and c-LCP. f tan δ curve plotted against temperature for LC-semi-IPN and LCN, tested at 1 Hz.

We chose the main-chain LCN based on thiol-acrylate Michael addition as the soft LCN matrix, which has been widely used as energy-dissipation materials in a number of researches16,21,30. In consideration of the compatibility between c-LCP and LCN, the mesogenic moieties of c-LCP and LCN should be similar. The LCN matrix was fabricated by commercial diacrylate mesogens (RM257) whose mesogenic structure is similar to that of RM82, dithiol spacers (EDDET), and tetrathiol crosslinkers (PETMP) (Fig. 2b). Previous research demonstrated that LCN with lower crosslinking density shows a higher energy-dissipation efficiency (manifested as dissipated coefficient, the area under the load-unload curves divided by the area under the load curves1)10,29, and thus we chose an LCN matrix with low crosslinking density (the ratio of tetrathiol crosslinker to the sum of dithiol spacer and tetrathiol crosslinker is 5%).

To prepare LC-semi-IPN with a large size and exclude the influence of solvent, we chose a bulk polymerization-based method: blending c-LCP with the reagents of LCN matrix with equal weight and curing the mixture in one pot, referred from previous research10. Previously reported LCNs were mostly fabricated by solution polymerization, hot pressing, or 3D printing methods9,54,55, all of which face great challenges when it comes to mass production of LCN or preparing LCN with large size and weight. Besides, the residual solvent from the fabrication process would affect the energy-dissipation performance of LCN samples32. Herein, the bulk polymerization-based method could exclude the influence of solvent as no solvent was utilized. The swelling experiments of LC-semi-IPN (Supplementary Table 1) also demonstrated that the gel content of LC-semi-IPN (52%) was almost consistent with the mass content of infused c-LCP (50%), indicating c-LCP had not reacted with the LCN matrix and could be almost removed by the swelling experiment. In comparison, we also prepared single liquid crystal network to investigate the difference in energy-dissipation and mechanical properties between LC-semi-IPN and single LCN.

Crystalline characterization of LC-semi-IPN

We found c-LCP in LC-semi-IPN induced the crystalline behaviors of the network, demonstrated by wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS). The WAXS results showed LCN exhibited no crystallization peak, whereas c-LCP and LC-semi-IPN showed very similar WAXS curves (Fig. 2c), Both of which had apparent crystallization peaks around 10°, 20°, and 25°, indicating c-LCP induced the crystallization behavior LC-semi-IPN. Also, the 2D-WAXS results showed apparent diffraction rings of c-LCP and LC-semi-IPN, while no diffraction ring was observed in the LCN sample (Supplementary Fig. 6).

The melting and re-crystallizing procedures also implied that LC-semi-IPN had the reversible crystallization properties. To investigate its crystallization procedure, we reheated the LC-semi-IPN sample to eliminate their crystallization behaviors and performed WAXS tests at different hours after reheating. The results indicated that their crystallization behaviors were observed after 1 day, and the crystallization process could be mostly completed in 5 days as almost no difference in WAXS curves is observed after 5 days (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 7). We furthermore investigated the phase transition behaviors of LC-semi-IPN by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). The DSC results revealed that LCN without c-LCP had no melting peak (Fig. 2e). Whereas, c-LCP and LC-semi-IPN had apparent melting peaks (melting temperature, Tm) at about 58 °C and 56 °C, respectively, demonstrating the crystallization behaviors of both c-LCP and LC-semi-IPN. Compared with the LC-isotropic temperature (Ti) of LCN (about 64 °C), Ti of LC-semi-IPN reached up to 103 °C, close to that of c-LCP (107 °C). The differences in Tm and Ti indicated the infused c-LCP could change the thermal properties of the original LCN. We also investigated the crystallization procedure of LC-semi-IPN by DSC tests of LC-semi-IPN at different days after reheating (Supplementary Fig. 8). The DSC curves showed the melting peak disappeared after reheated, while a weak melting peak showed up again after about 3 h, and an apparent peak was observed after 12 h, indicating the crystallization behavior occurred after 12 h.

Superior dynamic responsive properties of LC-semi-IPN

LC-semi-IPN demonstrated superior dynamic responsive properties, whose effective damping temperature range is more than 130 °C (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 9). The tests about its dynamic responsive properties were conducted by utilizing an oscillatory strain rheometer. Figure 2f revealed that the tan \({{{\boldsymbol{\delta }}}}\)-temperature curve of LC-semi-IPN featured two transition peaks around 54°C and 104°C (melting temperature and LC-isotropic temperature), in corresponding to the results of DSC tests. According to the DSC tests, Ti of LC-semi-IPN leaped from 64 °C to 103 °C due to the incorporation of c-LCP, and thus the temperature range between Tg and Ti was enormously expanded. Compared with LCN whose upper threshold of effective damping temperature is about 47 °C, LC-semi-IPN showed effective loss factor even at 155 °C and its effective damping temperature range is wider than 130 °C. In fact, none of previously reported LCN demonstrated satisfactory performance over 100 °C, and the effective damping temperature range of them fail to exceed 75 °C. At elevated temperature over Ti, LCN would transit into isotropic and its damping performance has almost no difference from ordinary network10. In contrast, LC-semi-IPN still perform effective energy-dissipation at the temperature higher than its Ti. That is because interpenetrated linear polymers move forth and back in the network, which facilitates dissipating energy56.

The molecular weight of c-LCP also plays a role in its damping performance, and LC-semi-IPN with proper molecular weight exhibits outstanding energy-dissipation ability. We prepare c-LCP with different molecular weights: c-LCP-1, c-LCP-2, c-LCP-3 (from the lowest to the highest, Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4), and correspondingly LC-semi-IPNs: LC-semi-IPN-1, LC-semi-IPN-2, LC-semi-IPN-3. The tan δ-temperature curves of LC-semi-IPNs demonstrate that LC-semi-IPN-2 exhibits wide effective damping temperature range and high loss factor at the same time (Supplementary Fig. 10), and thus we choose LC-semi-IPN-2 as LC-semi-IPN energy-dissipation material in subsequent experiments. The difference in damping performance of LC-semi-IPNs might originate from the difference in the internal chain friction and the chain reputation of c-LCPs. Although LC-semi-IPN-1 (with the lowest molecular weights of c-LCP) has high loss factor at its melting temperature, its effective damping temperature range is much narrower than that of the others. This may due to the weak internal chain friction between c-LCP-1 and LCN matrix at high temperature. While, in contrast, although LC-semi-IPN-3 (with the highest molecular weights of c-LCP) has wide effective damping temperature range, its loss factor is much lower than that of LC-semi-IPN-2 at melting temperature and LC-isotropic temperature. The internal chain friction between c-LCP-3 and LCN matrix might hinder the re-orientation of mesogens, resulting in the decrease of its loss factor. In consideration of both wide effective damping temperature range and high loss factor, LC-semi-IPN-2 stands out among the others.

Robust mechanical performance and enhanced energy-dissipation efficiency of LC-semi-IPN

Compared with single liquid crystal network, LC-semi-IPN exhibited a remarkable enhancement in mechanical performance. We conducted the uniaxial tension test to investigate the difference in mechanical performance between LC-semi-IPN and the single LCN. The stress-strain curves illustrated a giant leap in the mechanical performance of LC-semi-IPN than that of LCN (Fig. 3a). The results showed that Young’s modulus of LC-semi-IPN leaped by a factor of 18 (LCN: 0.86 MPa; LC-semi-IPN: 15.64 MPa) and the toughness also leaped more than 4 times (LCN: 1.56 MJ/m3; LC-semi-IPN: 6.28 MJ/m3) (Fig. 3b). Young’s modulus of LCN is remarkably influenced by the strain of the calculation point14, thus all of Young’s modulus is calculated based on the slope of stress-strain curves at the strain range from 0 to 10%, where the “plateau area” has slightly influence on the calculation of Young’s modulus. The wide plateau area in the stress-strain curve of LCN arises from the internal re-orientation of mesogenic moieties in LCN upon stretching, where the stress nearly has no change with the increase of strain. In comparison, we conducted the uniaxial tension test on the c-LCP, which has a high Young’s modulus of about 58.6 MPa whereas its elongation at break is about 15%, resulting in a low toughness of about 0.5 MJ/m3 (Supplementary Fig. 11).

a The stress-strain curves of LC-semi-IPN and LCN. b The comparison in Young’s modulus and toughness between LCN and LC-semi-IPN. c The load-unload curves of LC-semi-IPN and LCN at different normalized tensile strains. d The comparison in the dissipated energy and dissipated coefficient between LCN and LC-semi-IPN at different normalized tensile strains. e The comparison in the dissipated energy between LCN and LC-semi-IPN at different tensile strain rates. f The comparison in Young’s modulus between LCN and LC-semi-IPN at different tensile strain rates.

Compared with single LCN, LC-semi-IPN also exhibited a much superior energy-dissipation efficiency than that of LCN samples in the tensile load-unload tests. We chose 40%, 60%, and 80% of elongation at break as the maximum strain during the test. In this way, we could compare the energy-dissipation performance of samples under different extents of deformation. The LC-semi-IPN samples showed a larger hysteresis loop as illustrated by load-unload curves, symbolizing it could dissipate more energy during the test (Fig. 3c). Based on the original stress-strain curves, we calculated the area of the hysteresis loop as dissipated energy during the test and defined the area of the hysteresis loop divided by the area under the loading curve as dissipated coefficient (Supplementary Fig. 12). The dissipated energy (manifested as the area under the load curves1) of LC-semi-IPN is significantly superior to that of LCN, exhibiting an almost 19-fold enhancement at the 40% normalized strain (20-fold enhancement at 60%, and 12-fold enhancement at 80%) (Fig. 3d). Notably, as the maximum strain increases, the dissipated coefficient of LCN is remarkably decreased from 84% to 57%, as mesogenic moieties are gradually aligned along the tensile axis and the network exhibited elastic deformation, demonstrating the suppression of hysteresis behaviors in LCN at large extension. In contrast, the dissipated coefficient of LC-semi-IPN maintains a high value and increases from 81% to 88%, which is 1.54 times higher than that of LCN at the 80% normalized strain (the dissipated coefficient of LCN is 57%). This might be attributed to the π-π interactions between c-LCP and LCN matrix, which promoted the energy-dissipation behaviors of LC-semi-IPN. Furthermore, due to the re-crystallization ability of LC-semi-IPN, the sample after reheating can be reused, and the load-unload curves of the reheated LC-semi-IPN samples show almost no difference between the sample before reheated and after re-crystallizing for 7 days (Supplementary Fig. 13), indicating LC-semi-IPN could be reused after the reheating and recrystallization. To verify the long-life performance of LC-semi-IPN, we compared the energy-dissipation and mechanical performance between new samples and the samples kept for over 2 months (Supplementary Fig. 14). The results showed that the LC-semi-IPN sample kept for over 2 months had little difference in dissipated coefficient with the new sample.

Over a wide range of strain rates, LC-semi-IPN also has significantly enhanced mechanical performance and energy-dissipation efficiency. Ideal high-performance damping materials should be capable of absorbing energy efficiently over a range of strain rates. However, it is a challenge to realize rate dependency in most current energy-dissipation materials57. Recent research revealed that LCN exhibits a unique mechanical property, rate-dependent behavior. The feature means Young’s modulus and the dissipated energy of LCN could increase by orders of magnitude with a power-law relationship as the strain rate increases9,13,14. To investigate the rate-dependent energy dissipation behavior of LC-semi-IPN and LCN, we conducted the load-unload test in different strain rates (0.002/s, 0.008/s, 0.032/s, 0.128/s), and chose 40% of elongation at break as the maximum strain (Supplementary Fig. 15). The results show that both LC-semi-IPN and LCN have an increasing dissipated energy and Young’s modulus as the strain rate increases (Figs. 3e and 3f). Moreover, compared with LCN, LC-semi-IPN dissipates more energy and has a higher Young’ modulus by more than a factor of 10 over the entire range of strain rate from 0.002/s to 0.128/s, suggesting the superior performance of LC-semi-IPN than that of LCN under a wide variety of loading conditions.

Consistent with the results of the tensile load-unload tests, the compressive load-unload tests also confirmed superior Young’s modulus and energy-dissipation efficiency of LC-semi-IPN, signifying its enhanced performance in various practical conditions. Previously, limited by the preparation method, it is a challenge to fabricate bulk LCN samples and thus compressive studies on LCN were seldom reported9. Based on the bulk polymerization method, we could fabricate bulk LCN and LC-semi-IPN samples in a larger size and conduct the compressive test to investigate the mechanical performance and energy-dissipation ability of LC-semi-IPN under compression. The results of compressive tests showed that Young’s modulus of LC-semi-IPN leaped by a factor of 16 (LCN: 0.62 MPa; LC-semi-IPN: 10.06 MPa), and Young’s modulus is calculated based on the slope of stress-strain curves at the strain range from 0 to 10%, consistent with the calculation method of Young’s modulus at tensile tests (Figs. 4a and 4b). Compared with LCN, the LC-semi-IPN sample dissipated more energy over the whole strain range from 40% to 80%, whose dissipated energy was enhanced by 24-fold at 40% (by 18-fold at 60%, by 8-fold at 80%) (Fig. 4c). Moreover, the dissipated coefficient of LC-semi-IPN is nearly 3 times higher than that of LCN over the whole range of compressive strain, demonstrating that LC-semi-IPN performs a superior energy-dissipation efficiency under compression (Fig. 4d). The energy dissipation result measured in the tensile tests and in the compressive test is different. We suppose there could be two main reasons: the different modes of force application and different alignment degree of mesogens (as mesogens of LCN might be fully aligned in tensile test but not in the compressive test). In the compressive test, the bulk LC-semi-IPN sample can recover its original shape after reheating at 120 °C, and thus it can be reused (Supplementary Fig. 16).

a The compressive load-unload curves of LC-semi-IPN. b The compressive load-unload curves of LC-semi-IPN. c The comparison in the dissipated energy between LCN and LC-semi-IPN at different compressive strains. d The compressive load-unload curves of LCN at different strain rates. e The comparison in the dissipated energy between LCN and LC-semi-IPN at different compressive strain rates. f The comparison in Young’s modulus between LCN and LC-semi-IPN at different compressive strain rates.

We also compared the mechanical and energy-dissipation performance of LCN and LC-semi-IPN at different compressive strain rates to verify the rate-dependent behavior of the samples in compressive rest (Supplementary Fig. 17). The results demonstrated that both dissipated energy and Young’s modulus were improved by a factor of 10 over the whole range of compressive strain rates (Fig. 4e and 4f).

Impact resistance of LC-semi-IPN

In the practical falling steel ball experiment, LC-semi-IPN showed superior impact resistance performance and protected brittle items from shock. We covered a LC-semi-IPN film with a thickness of about 1 mm on a glass slide and dropped a 50 g steel ball above the samples from the same height of about 1 m to mimic the impact process (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 18). The glass slide without any protection was broken into pieces (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Movie 1), while the glass slide covered with LC-semi-IPN was undamaged (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Movie 2). In contrast, commercial poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) (Supplementary Movie 3) and LCN (Supplementary Movie 4) samples failed to protect the glass slide from the impact, and the glass slide was also broken in pieces. In addition, both LCN and PDMS samples were deformed after the falling steel ball experiment, whereas LC-semi-IPN samples had almost no change (Supplementary Fig. 19).

a Schematic illustrating the equipment of the falling steel ball test. b Photographs of the glass slide after the impact of a falling steel ball from the same height. These glass slides were covered by the PDMS, LCN, and LC-semi-IPN films used as the protection materials, and a glass slide was used as a blank sample. Scale bar: 2.5 mm. c Schematic illustrating the equipment to verify the deformation resistance ability of PDMS, LCN, and LC-semi-IPN samples. d Photographs of PDMS, LCN, and LC-semi-IPN samples after the impact of a falling ball. These samples were originally covered on a hollow square column.

Furthermore, LC-semi-IPN demonstrates enhanced resistance to impact, whereas LCN and PDMS were deformed to different extents following impact. The samples with a thickness of about 2 mm were covered on a hollow square column, and a steel ball was dropped on the samples from the same height (Fig. 5c). The PDMS film was cracked and the LCN film was largely deformed upon the impact of the steel ball (Fig. 5d). Whereas, the LC-semi-IPN film maintained its original shape and showed no deformation, indicating LC-semi-IPN has both ideal impact-resistance and excellent energy-dissipation abilities.

Energy-dissipation ability of architected material based on LC-semi-IPN

To explore its promising application as light-weight efficient energy-dissipation metamaterials, LC-semi-IPN can be utilized as high-performance architected structure. Recently, a unique multistable architected material based on LCN was reported to trap energy by the deformation of bistable LCN beams13,57. Whereas, due to the low modulus of LCN, the reported architected LCN materials only show an unsatisfying energy absorption density of about 7 × 104 Nm/m3 at the highest strain rate of 2.38 × 10−1 /s (Its energy absorption density increased as the strain rate increased)13. Herein, we fabricated a similar architected material based on LC-semi-IPN and calculated its energy absorption density in a compressive test (Fig. 6a). The LC-semi-IPN-based structure exhibited an improved energy absorption density by a factor of 10 (LC-semi-IPN: 12.62 × 105 Nm/m3; LCN: 1.84 × 105 Nm/m3) than that of the LCN-based structure at the strain rate of 8.3 × 10−4 /s (Fig. 6b), which was 18 times higher than the highest energy absorption density of the reported structure even at a lower strain rate. Notably, the bistable LCN-based structure could not recover its original shape even after the imposed compress was removed for 1 h and the upper layer still maintained buckled (Supplementary Fig. 21), while the shape of the bistable LC-semi-IPN-based structure was almost recovered after 1 h. That is because the enhanced modulus and stiffness of LC-semi-IPN promote its deformation resistance ability against the imposed compress. We further repeated the compressive experiment after the LC-semi-IPN-based structure recovered its original shape and investigated the energy-dissipation behaviors of the LC-semi-IPN-based structure when repeatedly used without the reheating procedure (Fig. 6c). The results showed that the energy absorption density of the LC-semi-IPN structure is slightly declined but still significantly higher than that of the LCN-based structure and the reported structure.

a Photographs of the LC-semi-IPN-based structure when the external compress was imposed and then released. (i, ii) The LC-semi-IPN-based structure was deformed as it was applied with a compress. (iii) When the compress was released, the upper layer was buckled, while the lower layer recovered its original shape mostly. (iv) After the compress was released for 1 h, the entire structure almost recovered its initial shape. b The force-displacement curves of LC-semi-IPN and LCN. c The force-displacement curves of LC-semi-IPN in the repeated compressive tests.

Discussion

Herein, we developed LC-semi-IPN materials made of a crystalline linear polymer and a crosslinked liquid crystal network, which exhibit superior mechanical properties and energy-dissipation performance than other ordinary damping LCNs, demonstrating its potential practical application in the field of impact damping. In addition to its “soft elasticity” property, the chain reptation of c-LCP also endows LC-semi-IPN with effective energy-dissipation performance at the widest temperature range among all reported LCNs. In this work, we utilized the feasible and scalable bulk polymerization-based fabrication method, which endows LC-semi-IPN with the possibility to become efficient damping materials that can be mass-produced industrially.

LC-semi-IPN could be further improved through various optimization approaches, including molecular design, structure design and fabrication technique, which demonstrates its giant potential in energy-dissipation. For example, c-LCP with high Ti could increase the temperature difference between glass transition and LC-isotropic phase transition of two components in LC-semi-IPN, and further broaden the effective damping temperature range of LC-semi-IPN. Also, to optimize the energy-dissipation performance of LC-semi-IPN, other LCN systems except from the LCN based on thiol-acrylate Michael addition in this work could be further explored. Moreover, by integrating nanoparticles, LC-semi-IPN might exhibit extraordinary properties. To explore its promising application as light-weight efficient energy-dissipation metamaterials, we could utilize advanced 3D printing technology to fabricate LC-semi-IPN as complex energy-dissipation metamaterials such as materials with negative Poisson’s ratio.

LC-semi-IPN in this work is only a demonstration about the striking properties of semi-IPN in the field of damping LCNs. This synergistic design concept is applicable to other non-LC materials and provides a general approach to developing efficient energy-dissipation materials where both robust mechanical performance and superior energy-dissipation abilities are required.

Methods

Materials

All reagents, including 1,4-bis-[4-(6-acryloyloxypropyloxy)-benzoyloxy]−2-methylbenzene (RM82, 98%, Hunan Chemfish Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.), 1,4-bis-[4-(3-acryloyloxypropyloxy)-benzoyloxy]−2-methylbenzene (RM257, 97%, Hunan Chemfish Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.), methyl methacrylate (MMA, 99.5%, Macklin), 1,3-dimercaptopropane (98%, Energy Chemical), 3,6-dioxa-1,8-octanedithiol (EDDET, 97%, TCI), pentaerythritol tetrakis(3-mercaptopropionate) (PETMP, 95%, Energy Chemical), butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT, 98.5%, J&K Scientific) triethylamine (TEA, J&K Scientific) dipropylamine (DPA, Amethyst Chemicals), methanol (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd.), dichloromethane (DCM, Beijing Tong Guang Fine Chemicals Company) were purchased from commercially available suppliers and directly used without further purification.

Synthesis of c-LCP

C-LCP was prepared based on the thiol-acrylate Michael addition. Firstly, diacrylate mesogenic monomer (RM82, 10 mmol), dithiol spacer (1,3-dimercaptopropane, 11 mmol), and DPA (4 wt% of the total reagents) were dissolved in DCM and stirred homogenously at room temperature for 18 h. The MMA (4 mmol) was added into the mixture and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for another 18 h to react with residual sulfhydryl. Then, the viscous liquid crystal polymer mixture was precipitated in methanol for 5 times and dried under vacuum at 40 °C for 2 days. 1H NMR spectrum of c-LCP was shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.18 – 8.09 (m, 2H), 7.19 – 7.03 (m, 2H), 7.00 – 6.92 (m, 2H), 4.11 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 4.04 (td, J = 6.4, 2.1 Hz, 2H), 2.61 (dt, J = 12.4, 7.2 Hz, 10H), 2.23 (s, 1H). The molecular weight of c-LCP can be calculated by 1H NMR. Degree of Polymerization (Xn) was calculated by the phenyl peak at 8.13 ppm (named as “a” peak) and the peak at 2.16 ppm, which is the carbon next to sulfur (named as “d” peak),

Thus, Xn was calculated as 13 (close to its feeding ratio), and the Mn of c-LCP was calculated as 10500 g mol−1 (Supplementary Table 2).

To investigate the energy-dissipation performance of LC-semi-IPN with different molecular weights of c-LCP, we synthesized c-LCPs with different molecular weights: c-LCP-1, c-LCP-2, c-LCP-3 (from the lowest molecular weights to the highest molecular weights) (Supplementary Table 2). Correspondingly, LC-semi-IPNs with different c-LCPs are rename as LC-semi-IPN-1, LC-semi-IPN-2, LC-semi-IPN-3. It should be note that in the paper LC-semi-IPN refers to LC-semi-IPN-2 unless specific notations.

Synthesis of LCN

Diacrylate mesogenic monomer (RM257, 2 mmol), dithiol spacer (EDDET, 1.8 mmol), multi-functional crosslink reagent (PETMP, 1 mmol) and polymerization inhibitor (BHT, 0.5 wt% of the total reagents) were weighted in a Teflon mold. The mixture was heated at 90 °C for 10 min and stirred vigorously until homogenous. When the mixture cooled down to the room temperature, TEA (1 wt% of the total reagents) was added into the mixture and the mixture was stirred vigorously until homogeneous. The mixture was processed at 40 °C in vacuum for 5 min to remove the air bubbles. Finally, the mixture was cured at 80 °C for 2 days to obtain the LCN sample.

Synthesis of LC-semi-IPN

Based on the before-mentioned method, we prepared LC-semi-IPN samples. Firstly, Diacrylate mesogenic monomer (RM257, 1 mmol), dithiol spacer (EDDET, 0.9 mmol), multi-functional crosslink reagent (PETMP, 0.05 mmol) and polymerization inhibitor (BHT, 0.5 wt% of the total reagents) were weighted in a Teflon mold. The mixture was heated at 90 °C for 10 min and stirred vigorously until homogenous. Then c-LCP (the same mass as the total mass of weighted reagents in the first step) was added into the mixture and heated at 120 °C for another 10 min and the mixture was stirred vigorously until homogenous. When the mixture cooled down to the room temperature, TEA (1 wt% of the total mass of weighted reagents in the first step) was added into the mixture and the mixture was stirred vigorously until homogeneous. The mixture was processed at 40 °C in vacuum for 5 min to remove the air bubbles. Finally, the mixture was cured at 80 °C for 2 days to obtain the LC-semi-IPN sample. All the samples performed in the mentioned tests were kept for over 2 months to demonstrate the long-life performance of LC-semi-IPN.

Fabrication of architected structure

The thickness of LCN and LC-semi-IPN beams were about 1 mm. The Polymethyl Methacrylate-based (PMMA-based) support structures were fabricated by a laser cutting machine (KT-4060). Supplementary Fig. 20 schematically illustrates the size map of the architected structure. We cut the architected structure from commercial PMMA sheet (with the thickness of 6 mm) by the laser cutting machine. Then, the LCN and LC-semi-IPN beams were fixed to the cut PMMA-based support structures.

General characterization

Wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) analyses were performed by Ganesha 300 XL SAXS system (SAXSLAB). Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiments were conducted on TA instruments Q2000 with a scanning rate of 5 °C min−1 from −50 to 150 °C. The tensile and compressive tests were conducted by Universal Testing System (MTS CMT6503). The rheology analyses were performed on a TA-AR200ex rheometer with parallel plate geometry (diameter: 8 mm), and the test frequency is 1 Hz. 1H NMR spectroscopy tests were performed by a JEOL JNM-ECA400 (400 MHz) spectrometer (JEOL Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in CDCl3. Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) tests were conducted by Shimadzu LC-20AD pump system and using N, N-dimethyl formamide (DMF) containing 50 mM LiBr as the eluent.

Data availability

All data is available in the main text or supplementary materials. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

References

Xiang, H. et al. Highly damping and self-healable ionic elastomer from dynamic phase separation of sticky fluorinated polymers. Adv. Mater. 35, e2209581 (2023).

Park, B. et al. Cuticular pad–inspired selective frequency damper for nearly dynamic noise–free bioelectronics. Science 376, 624–629 (2022).

Liu, K. et al. Biomimetic impact protective supramolecular polymeric materials enabled by quadruple H-Bonding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 1162–1170 (2021).

Dong, M. et al. Digital light processing 3D printing of tough supramolecular hydrogels with sophisticated architectures as impact-absorption elements. Adv. Mater. 34, e2204333 (2022).

Liang, X. et al. Impact-Resistant Hydrogels by Harnessing 2D Hierarchical Structures. Adv. Mater. 35, e2207587 (2023).

Herbert, K. M. et al. Synthesis and alignment of liquid crystalline elastomers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 23–38 (2021).

Ohm, C., Brehmer, M. & Zentel, R. Liquid crystalline elastomers as actuators and sensors. Adv. Mater. 22, 3366–3387 (2010).

Warner, M. & Terentjev, E. M. Nematic elastomers—A new state of matter? Prog. Polym. Sci. 21, 853–891 (1996).

Mistry, D. et al. Soft elasticity optimises dissipation in 3D-printed liquid crystal elastomers. Nat. Commum. 12, 6677 (2021).

Saed, M. O. et al. Impact damping and vibration attenuation in nematic liquid crystal elastomers. Nat. Commum. 12, 6676 (2021).

Clarke, S. M. et al. Soft elasticity and mechanical damping in liquid crystalline elastomers. J. Appl. Phys. 89, 6530–6535 (2001).

Hotta, A. & Terentjev, E. M. Dynamic soft elasticity in monodomain nematic elastomers. Eur. Phys. J. E 10, 291–301 (2003).

Jeon, S. Y. et al. Synergistic energy absorption mechanisms of architected liquid crystal elastomers. Adv. Mater. 34, e2200272 (2022).

Martin Linares, C. P. et al. The effect of alignment on the rate-dependent behavior of a main-chain liquid crystal elastomer. Soft Matter 16, 8782–8798 (2020).

Ohzono, T. et al. Internal constraints and arrested relaxation in main-chain nematic elastomers. Nat. Commum. 12, 787 (2021).

Liang, H. et al. Elastomers grow into actuators. Adv. Mater. 35, e2209853 (2023).

Jin, B. et al. Solvent-assisted 4D programming and reprogramming of liquid crystalline organogels. Adv. Mater. 34, e2107855 (2022).

Xia, Y., Zhang, X. & Yang, S. Instant locking of molecular ordering in liquid crystal elastomers by oxygen-mediated thiol–acrylate click reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 5665–5668 (2018).

Qian, X. et al. Untethered Recyclable Tubular Actuators with Versatile Locomotion for Soft Continuum Robots. Adv. Mater. 30, e1801103 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Seamless multimaterial 3D liquid-crystalline elastomer actuators for next-generation entirely soft robots. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay8606 (2020).

Yakacki, C. M. et al. Tailorable and programmable liquid-crystalline elastomers using a two-stage thiol–acrylate reaction. RSC Adv. 5, 18997–19001 (2015).

Azoug, A. et al. Viscoelasticity of the polydomain-monodomain transition in main-chain liquid crystal elastomers. Polymer 98, 165–171 (2016).

Guo, H., Terentjev, A., Saed, M. O. & Terentjev, E. M. Momentum transfer on impact damping by liquid crystalline elastomers. Sci. Rep. 13, 10035 (2023).

Luo, C. et al. 3D printing of liquid crystal elastomer foams for enhanced energy dissipation under mechanical insult. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 13, 12698–12708 (2021).

Traugutt, N. A. et al. Liquid-crystal-elastomer-based dissipative structures by digital light processing 3D printing. Adv. Mater. 32, e2000797 (2020).

Unwin, A. P. et al. Escaping the Ashby limit for mechanical damping/stiffness trade-off using a constrained high internal friction interfacial layer. Sci. Rep. 8, 2454 (2018).

Shaid Sujon, M. A., Islam, A. & Nadimpalli, V. K. Damping and sound absorption properties of polymer matrix composites: A review. Polym. Test. 104, 107388 (2021).

Li, Q. et al. Poly(Ionic Liquid) double-network elastomers with high-impact resistance enhanced by cation-pi Interactions. Adv. Mater. 36, e2311214 (2023).

Merkel, D. R. et al. Thermomechanical properties of monodomain nematic main-chain liquid crystal elastomers. Soft Matter 14, 6024–6036 (2018).

Merkel, D. R., Shaha, R. K., Yakacki, C. M. & Frick, C. P. Mechanical energy dissipation in polydomain nematic liquid crystal elastomers in response to oscillating loading. Polymer 166, 148–154 (2019).

Huang, W. et al. A natural impact-resistant bicontinuous composite nanoparticle coating. Nat. Mater. 19, 1236–1243 (2020).

Wu, Y. et al. Molecular clogging organogels with excellent solvent maintenance, adjustable modulus, and advanced mechanics for impact protection. Adv. Mater. 35, 2306882 (2023).

Jaglinski, T., Kochmann, D., Stone, D. & Lakes, R. S. Composite materials with viscoelastic stiffness greater than diamond. Science 315, 620–622 (2007).

Lakes, R. S., Lee, T., Bersie, A. & Wang, Y. C. Extreme damping in composite materials with negative-stiffness inclusions. Nature 410, 565–567 (2001).

Hussein, M. I. & Frazier, M. J. Metadamping: An emergent phenomenon in dissipative metamaterials. J. Sound Vib. 332, 4767–4774 (2013).

Chung, D. D. L. Review: Materials for vibration damping. J. Mater. Sci. 36, 5733–5737 (2001).

Moore, J. A., Ma, R., Domel, A. G. & Liu, W. K. An efficient multiscale model of damping properties for filled elastomers with complex microstructures. Compos. Part B: Eng. 62, 262–270 (2014).

Wei, Z. et al. Design of sustainable self-healing phase change materials by dynamic semi-interpenetrating network structure. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2312019 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Semi-interpenetrating polymer networks prepared from castor oil-based waterborne polyurethanes and carboxymethyl chitosan. Carbohydr. Polym. 256, 117507 (2021).

Li, Y., Li, G., Li, J. & Luo, Y. Preparation and properties of semi-interpenetrating networks combined by thermoplastic polyurethane and a thermosetting elastomer. N. J. Chem. 42, 3087–3096 (2018).

Samui, A. B. et al. Interpenetrating polymer networks based on nitrile rubber and metal methacrylates. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 99, 2542–2548 (2006).

Qi, X., Zhang, J., Zhang, L. & Yue, D. Bio-based, robust, shape memory, self-healing and recyclable elastomers based on a semi-interpenetrating dynamic network. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 25399–25407 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Semi-interpenetrating polymer networks based on cyanate ester and highly soluble thermoplastic polyimide. Polymers 11, 862 (2019).

Qu, C. et al. Damping, thermal, and mechanical performances of a novel semi-interpenetrating polymer networks based on polyimide/epoxy. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 136, 48032 (2019).

Shi, W. et al. Dynamic-bond-mediated chain reptation enhances. Energy Dissipation Elastomers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. n/a, e202401845 (2024).

Samui, A. et al. Studies on semi-interpenetrating polymer network based on nitrile rubber and poly(methyl methacrylate). J. APPL. POLYM. SCI. - J. APPL POLYM SCI 91, 354–360 (2004).

Lu, H.-F. et al. Interpenetrating Liquid-Crystal Polyurethane/Polyacrylate Elastomer with Ultrastrong Mechanical Property. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 14364–14369 (2019).

Zhao, Y. & Yuan, G. Interpenetrating Liquid Crystalline Polymer Networks. Macromolecules 29, 1067–1069 (1996).

Xu, S., Zhou, J. & Pan, P. Strain-induced multiscale structural evolutions of crystallized polymers: From fundamental studies to recent progresses. Prog. Polym. Sci. 140, 101676 (2023).

Kato, S. et al. Crystallization-induced mechanofluorescence for visualization of polymer crystallization. Nat. Commum. 12, 126 (2021).

Xu, D. et al. Graft copolymer elastomers with polar polyacrylonitrile as semicrystalline side chains: excellent toughness and healability. Macromolecules 53, 8928–8939 (2020).

Burns, A. B. & Register, R. A. Mechanical properties of star block polymer thermoplastic elastomers with glassy and crystalline end blocks. Macromolecules 49, 9521–9530 (2016).

Saed, M. O. et al. High strain actuation liquid crystal elastomers via modulation of mesophase structure. Soft Matter 13, 7537–7547 (2017).

Javed, M. et al. Programmable shape change in semicrystalline liquid crystal elastomers. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 14, 35087–35096 (2022).

Liang, H. et al. Merging the interfaces of different shape-shifting polymers using hybrid exchange reactions. Adv. Mater. 35, e2202462 (2022).

Huang, J. et al. Ultrahigh energy-dissipation elastomers by precisely tailoring the relaxation of confined polymer fluids. Nat. Commum. 12, 3610 (2021).

Shan, S. et al. Multistable architected materials for trapping elastic strain energy. Adv. Mater. Process. 27, 4296–4301 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22375114 and 21788102, Y.J.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.J. and Z.Y. conceived the central idea. Z.Y. performed the main experiments. Z.Y. and Y.J. wrote the manuscript draft. E.H., H.X., Y.L. and Y.W. participated in the discussion of the results. Y.Y. and H.L. reviewed and edited the manuscript. Y.J. and Y.W. arranged the funding and infrastructure for the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Hong Yang, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Z., Yang, Y., Liang, H. et al. Robust liquid crystal semi-interpenetrating polymer network with superior energy-dissipation performance. Nat Commun 15, 9902 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54233-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54233-x

This article is cited by

-

Hierarchically semi-interpenetrating polymer nanofilms for high-performance seawater desalination

Nature Water (2026)

-

High Energy Dissipation Polymer Gels by Regulating Relaxation of Confined Chains

Chinese Journal of Polymer Science (2026)

-

Buprestidae metamorphosis-inspired stiffening photonic elastomers for shape-color integrated memory and information encryption

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Manipulating mechanical strength of isoreticular two-dimensional polyamide materials via multiple interactions

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Fabrication and Characterization of Piezoelectric Nanogenerator Based on ZnO and PVP for Harvesting Energy System Applications

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2025)