Abstract

Polymer-ceramic composite electrolytes enable safe implementation of Li metal batteries with potentially transformative energy density. Nevertheless, the formation of Li-dendrites and its complex interplay with the Li-metal solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) remain a substantial obstacle which is poorly understood. Here we tackle this issue by a combination of solid-state NMR spectroscopy and Overhauser dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) which boosts NMR interfacial sensitivity through polarization transfer from the metal conduction electrons. We achieve detailed molecular-level insight into dendrites formation and propagation within the composites and determine the composition and properties of their SEI. We find that the dendrite’s quantity and growth path depend on the ceramic content and correlated with battery’s lifetime. We show that the enhancement of Li resonances in the SEI occurs through Li/Li+ charge transfer in Overhauser DNP, allowing us to correlate DNP enhancements and Li transport and directly determine the SEI lithium permeability. These findings have promising implications for SEI design and dendrites management which are essential for the realization of Li metal batteries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rechargeable lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are essential in the transition to sustainable energy utilization, yet they require increase in energy density, safety and longevity1,2,3. Li-metal anodes offer tenfold increase in energy density, but their surface reactivity leads to a complex interplay between electrolyte degradation and non-uniform lithium deposition which in liquid electrolytes poses a safety concern when it results in short-circuiting the cell. Electrolyte degradation results in formation of organic and inorganic interphases, referred to as the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI), when these phases provide surface passivation while allowing Li ion transport4. In practice, the beneficial properties of the SEI are not readily obtained, and the heterogeneity in surface conductivity results in formation of ‘hot spots’ for Li deposition in the form of dendritic microstructures4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Transitioning to solid electrolytes could mitigate the safety issues11, with polymer-ceramic composite electrolytes (PCE) being beneficial as they combine the high ion-conductivity of ceramic electrolytes with the mechanical flexibility of polymeric materials15,16,17,18. Nevertheless, dendrites formation and cell longevity remain a major concern19,20.

It was shown that the presence of ceramic particles suppresses dendrite formation to some extent compared to the polymer counterparts, yet the mechanism responsible for this suppression is not well-understood21,22,23. Clearly the electrolyte composition dictates the SEI content and in-turn the SEI properties, namely its ionic transport, which then dictates the propensity of dendrites in the cell24. As such, controlling charge transport properties of the SEI is crucial for achieving long-lasting batteries. This makes detection of the SEI and its properties of outmost importance for developing viable battery chemistries, yet gaining insight into the functionality of the SEI is extremely challenging due to the scarcity and limitation of analytical techniques25. While X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and electron microscopy (EM) offer insights into SEI chemistry26,27,28, solid-state NMR (ssNMR) spectroscopy29 can potentially be used to determine SEI composition and to directly probe the ion permeability of SEI phases30,31,32,33. Magic Angle Spinning Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (MAS-DNP), a process in which the high polarization of electron spins is transferred to surrounding nuclear spins, provides increased sensitivity for efficient charchterization of the sample34,35,36,37. Typically, MAS-DNP is obtained by utilizing nitroxide biradicals, which routinely results in 4 orders of magnitude increase in surface sensitivity and enables detection of the outer layers of the SEI30,38,39,40.

Endogenous DNP methods, where the polarizing agents come from within the material, are advantageous as they enable selective detection of buried interphases without adding any external reagent38,41. In the case of metallic lithium, the most suitable route for DNP is to utilize the conduction electrons of the metal itself for polarization via the Overhauser Effect (OE)42,43. This approach was effectively demonstrated in the pioneering DNP experiment on Li metal and more recently by Hope et al. as a path for enhancing NMR sensitivity to the SEI formed on dendrites in liquid electrolytes44. It was shown that in addition to the metallic 7Li resonance, multinuclear resonances of environments specific to the SEI were also enhanced. Yet the generality and mechanisms of polarization transfer from the dendrites to the SEI remains to be explored.

Here we perform a detailed atomic-level investigation of dendrites formation and propagation in different PCEs in association with their SEI. We focus our study on common PCE systems, incorporating polyethylene oxide (PEO, labelled PE), lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI), with variable content of Li1.5Al0.5Ge1.5(PO4)3 (LAGP, labelled LGPC in the composite) and Li6.4Al0.2La3Zr2O12 (LLZO, labelled LZPC in the composite) ceramics, chosen due to their conductivity, stability and common usage45. We employ ssNMR for quantitatively correlating between the ceramic content in the PCE, dendrites amount and the lifetime of the cells. OE-DNP is used for sensitive and selective detection of the SEI formed in different PCEs, which with support from EM studies allows us to track the path of dendrites propagation and rationalize the effect of PCEs composition on cell lifetime. Furthermore, we identify Li/Li+ charge transfer as the main route for SEI signal enhancement in OE-DNP. This allows us to uniquely utilize OE-DNP coupled with Li-chemical exchange saturation transfer (Li-CEST) to selectively probe Li+ dynamics across the inner SEI layers31. Overall, by utilizing OE-DNP and ssNMR we obtain in-depth understanding of (i) the composition of the SEI, (ii) the Li+ permeability of the SEI as well as (iii) the amount and propagation path of Li dendrites formed in state-of-the-art PCEs in correlation with the cell lifetime.

Results

Electrochemical performance and dendrites formation in PCEs

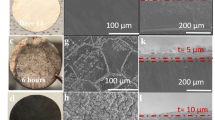

The PCEs were first tested in a Li symmetric cell using a standard current density of 0.05 mA/cm2 (Fig. 1a, b, S1, S2, supporting text) providing 150–170 mV over potential and stability for up to 140 h. Higher current densities were employed to determine the effect of PCE composition on dendrites formation and the amounts of dendrites formed was determined by ssNMR29,46,47. Here we assume that the NMR excitation is uniform across the dendrites microstructure as discussed by Bhattacharyya et al. 29,46,47 and confirmed here with lithium nutation and electron microscopy experiments (see below and supporting information). We analyzed composites with varying LAGP and LLZO levels (0 to 60 wt%) cycled under the same conditions (0.125 mA/cm² for up to 100 h at 30 °C). By integrating the 7Li ssNMR resonance of metallic lithium acquired under static conditions (see Fig. S3, supporting text and methods for more details) we identified that dendrite formation increased with ceramic content up to 40 wt%, then decreased at 60 wt% (Fig. 1c, d, averaged from more than 3 samples per composition). Analysis of the cumulative cycle time vs. cycle number revealed significant differences with PCE composition (Fig. S4). As expected, cells without ceramics showed early failure, highlighting that polymer-only PCE is not effective at dendrite suppression. Interestingly, cells with ceramic content exhibited increasingly superior durability and longer average cycle times (Fig. S4) up to 40% with the trend reversed at 60% ceramics. This finding suggests that despite the significantly higher formation of dendrites observed with increased ceramic content, somehow cells with 40% ceramics have higher durability. We hypothesize that this trend may be linked to changes in ion conduction pathways in the PCEs and variations in the dendrites propagation path and their interactions with the ceramic particles. Determining the dendrites path within the PCEs is a challenging task. Here we propose that determining the chemical components of the SEI could shed light on dendrite interactions within the PCE, as well as their pathways of growth, whether via the polymer or the ceramic components and potentially clarifying the nature of the interactions involved.

Top row: Galvanostatic cycling profile of the PCE using Li|PCE|Li configuration at 30 °C for (a) 40LGPC and b) 40LZPC cycled at current density of 0.05 mA/cm2. The inset shows a representative image of the 16 mm diameter PCE used for preparing the symmetric cells. Quantification of the dendrites conducted on different PCEs based on static 7Li ssNMR measured as a function of ceramic content for (c) LAGP and (d) LLZO. Error bars represent the standard deviation of at least three independent measurements. The inset shows representative 7Li spectra of cycled 40LGPC and 40LZPC which were acquired under static conditions. Bottom left: 6Li MAS-NMR spectra acquired for (e) PE with 100 s recycle delay, at 298 K and 30 KHz MAS; f LAGP powder with a 120 s recycle delay, at 298 K, and 30 kHz MAS; g LAGP powder measured with a 1000 s recycle delay, at 100 K, and 9 kHz MAS; h 40LGPC with 4000 s recycle delay, at 100 K, and 9 kHz MAS; i LLZO powder with 80 s recycle delay, at 298 K, and 20 kHz MAS; j 30LZPC composite with 400 s recycle delay, at 298 K and 20 kHz MAS. Bottom right: 6Li ssNMR spectra acquired at 100 K for PCEs cycled using 6Li metal in symmetrical Li|PCE|Li cell configurations, highlighting the enrichment of SEI and ceramic components for (k) 40LGPC (recycle delay of 4500 s, at 100 K, and 9 KHz MAS), l 60LGPC (recycle delay of 4800 s, at 100 K, and 9 KHz MAS), m 40LZPC (recycle delay of 500 s, at 100 K, and 8.5 KHz MAS), and n 60LZPC (recycle delay of 2000 s, at 100 K, and 8.5 KHz MAS). The ratio of moles specified on each spectrum represents the expected 6Li isotope ratios based on the PCE composition (in brackets) against the experimentally determined ratios post-cycling.

ssNMR investigation of the PCEs

In order to determine the composition of the SEI formed in different PCEs we first identified the spectral fingerprints of the PCEs and their components by 6Li ssNMR. To support the assignment and overcome some of the spectral overlap between different phases we employed heteronuclear NMR experiments, namely rotational echo double resonance (REDOR) which provides insight into spatial proximity (a few Angstroms) of nuclei30. In Fig. 1e–j the 6Li ssNMR spectra are plotted for uncycled PCEs and their components. All samples were measured at natural isotopic abundance (7% for 6Li) at different temperatures which results in some variation in the spectral broadening. Despite the relatively narrow range of chemical shifts, we can identify differences: The spectrum of the pure polymer electrolyte contains only the dissociated LiTFSI salt, resonating at −1.4 ppm. The LAGP powder contains two main resonances broad and narrow resonating at −0.7 and −1.4 ppm, respectively, assigned to disordered and ordered sites, respectively, in LAGP48. At low temperature (100 K for DNP experiments) these resonances broaden and shift due to the slower Li dynamics at this temperature (Fig. 1g, h). In LGPC, the LAGP resonances overlap with that of the Li+ ions in PEO (which has extremely long relaxation at 100 K). However, under microwave irradiation used for DNP we found that the resonance of the Li+ ions in PEO dominates the −1.4 ppm region (likely due to increased mobility of these ions). This was verified by 6Li{31P} REDOR experiment (Fig. S5) which showed no dephasing in this spectral region suggesting negligible contribution of the LAGP resonance under these conditions. In the case of pure LLZO, a distinct resonance is observed at 0.9 ppm, a feature that is also observed in LZPC49.

In cycled composites, detecting and differentiating the components of the SEI is even more challenging due to the limited chemical shift range, small quantities as well as the low natural abundance of 6Li nuclei50. While 7Li has higher abundance its spectra have lower resolution due to strong (compared to 6Li) dipolar and quadrupolar interactions. To overcome these challenges the electrolytes were cycled with 6Li-enriched metal which leads to the formation of 6Li-enriched dendrites and more importantly, 6Li enriched phases in the SEI formed on these dendrites. Moreover, examining the distribution of isotopes in the electrolytes post cycling can already (prior to analysis of the SEI) provide valuable insights into dendrite formation and propagation as well as ion transport paths in the cells45,50,51. This is based on the reasonable assumption that the interaction (physical contact with or without chemical reduction) of 6Li-enriched dendrites with different components of the PCEs will lead to their 6Li enrichment. We employed this approach on 40-60LGPC and 40-60LZPC. 6Li NMR spectra of the four PCEs after cycling vs. 6Li enriched metal are shown in Fig. 1k–n. In the spectra of LGPC samples an additional resonance can be seen at 1 ppm assigned to the SEI component LiOH52. The spectra were deconvoluted and the 6Li contribution in the ceramic particles vs. in PEO was compared. Notably, the 6Li spectra of LGPC and LZPC cycled with 6Li enriched metal exhibited significant deviations from the expected mole ratio of the components in the PCEs. In all samples the resonance of the ceramic particles was the most dominant, far above the contribution of Li ions in the PEO. This was particularly evident in the 40LGPC sample which showed pronounced enrichment of the LAGP resonance. In contrast, in 60LGPC the Li-PEO could be detected, suggesting this environment was also enriched but to a lesser extent. A consistent enrichment of the LLZO phase over Li-PEO was observed in both the 40 wt% and 60 wt% PCEs.

These results indicate that for 40LGPC the dendrite form close contact with LAGP particles while in 60LGPC there is also some interaction with the polymeric regions. In LZPC the LLZO phase is predominantly enriched. We note, however, that isotope tracing has limitations since Li exchange is occurring between all Li-containing components in the PCEs at different time scales which can lead to changes in the distribution of isotopes with time. To minimize this effect samples must be measured right after dissembling the battery cells (as was done here). To gain deeper insights into the interactions of the dendrites with the PCEs, we investigated the composition of the SEI layers.

Understanding SEI composition of PE, LGPC, and LZPC

As described above, we hypothesized that the dendrites propagation pathways could be revealed by examining the composition of their SEI. Figure 1k–n shows limited sensitivity for SEI detection due to the dominant signals from ceramics and Li-PEO. To overcome this and gain selectivity in detecting the SEI, we use the conduction electrons of the dendrites trapped within the composite (Fig. S3) as a polarization source in DNP44. This will result in selective polarization transfer and signal enhancement of nuclear spins in the SEI through the OE-DNP mechanism. For DNP experiments, the PCEs were carefully extracted from the cell and packed (along with the dendrites) into the DNP rotor (see experimental description for more details). This approach was first applied to a PEO-LiTFSI electrolyte (PE) without ceramics for determining the SEI formed from dendrite interactions with the polymer and salt.

Figure 2a, b demonstrates the effect of microwave irradiation of 6Li resonances in cycled PE, under optimal OE-DNP conditions. Significant amplification of the dendrites (~260 ppm) and diamagnetic (~0 ppm) resonances is observed with enhancement factors of 18 and 8, respectively.

a Microwave on/off OE-DNP spectra of cycled PE for the dendrite (left) and diamagnetic 6Li resonances which includes SEI and Li-PEO (right). b Microwave on/off OE-DNP spectra of the diamagnetic resonances (containing SEI, Li-PEO), highlighting the individual enhancement of each detected chemical species in parenthesis. The dendrite spectra were recorded with a recycle delay of 30 s for both microwave on and off conditions, while the diamagnetic 6Li spectra were obtained with 500 s and 2000 s recycle delay for microwave on and off, respectively. c DNP enhanced 6Li{1H} REDOR curve measured using recycle delay of 60 s and d DNP enhanced 6Li-6Li spin diffusion 2D measurements of the diamagnetic resonances in PE measured using mixing time of 2 s and recycle delay of 20 s. Errors were estimated based on the signal-to-noise ratio from the NMR spectra.

We note that the dendrites resonance without microwaves is much narrower than the spectra shown in the insets of Fig. 1c, d. The narrowing is due to the detection of pure dendrites (separated from the metal), the use of MAS, which removes anisotropies and susceptibility effects, as well as use of 6Li rather than 7Li which has weaker dipolar and quadrupolar couplings. Interestingly, upon microwave irradiation the dendrites resonance is significantly broadened. Hope et al. 44 attributed this broadening to the saturation of the conduction electrons spin resonance which results in partial decrease in the nuclear Knight shift. In addition, we expect that heterogeneity in the microwave power and in the dendrites properties (conductivity, morphology and distribution) would all lead to variability in the extent of microwave saturation which would result in a broad distribution of nuclear resonance frequencies across the sample. The enhancements were further confirmed by DNP field sweep experiments (Fig. S6) which highlight the efficiency of OE-DNP in distinguishing SEI components in the diamagnetic region (Fig. 2b). With the markedly improved sensitivity from OE-DNP we were able to clearly identify the SEI species, Li2O resonating at 2.6 ppm and LiOH at 1 ppm, in a few hours instead of days.

6Li{1H} REDOR experiments confirmed the assignment of SEI components (Fig. 2c), in particular of LiOH resonating at 1 ppm, which completely dephases due to close proximity between 1H and 6Li nuclei. Li-PEO exhibited lower REDOR effect, attributed to its high mobility, in particular under microwave irradiation (as indicated by the significant decrease in longitudinal relaxation and the line narrowing observed for this resonance upon microwave irradiation). Surprisingly, Li2O also showed significant dephasing, indicating a mixed SEI structure where Li2O and LiOH have a mutual and substantial interface formed between them, which would require nanometric domain sizes, leading to the observed REDOR effect (Fig. S7). This was supported by DNP-enhanced 6Li-6Li 2D homonuclear correlation experiment (Fig. 2d), revealing strong correlations between oxide and hydroxide phases.

Next, we employed this approach to PCEs with 40 wt% and 60 wt% LAGP. Under microwave irradiation at the optimal OE-DNP conditions, 40LGPC showed significant dendrite and diamagnetic Li enhancement factors of 80 and 19, respectively, exceeding those in the PE samples (Fig. 3a, S8). In contrast, 60LGPC composites had lower enhancements of 40 for dendrites and 8 for diamagnetic resonances (Fig. 3b). These trends in enhancement factors were consistent between compositions with some variation between PCEs with the same composition, likely due to variability in dendrite amounts and distributions (Fig. S9). Deconvolution of spectra revealed enhancement of the SEI components. As in the PE, for both 40-60LGPC samples, the Li2O resonance is hardly visible without DNP (Fig. 3c, d). Additionally, resonances in the 1.2–1.4 ppm region were also enhanced but compared with PE, 6Li{1H} REDOR experiments revealed notable differences in this range (Fig. 3e, f). While in PE and 60LGPC this resonance dephased completely within 1 ms of recoupling pulses, in 40LGPC it plateaued at 70% within the same time. This suggests the presence of additional 6Li environment which is not LiOH and is likely unprotonated, the assignment of which will be discussed shortly. This effect can be seen more clearly in Fig. 4a–c where the slices of the REDOR experiments are compared. Meanwhile, the Li2O REDOR curve is consistent in the three electrolyte compositions measured, PE and 40-60LGPC. Overall, 60LGPC displayed very similar REDOR curves as the PE sample, suggesting the SEI formed in these samples is very similar (Figs. 3e, 4c). To uncover the additional phase contributing to the SEI in 40LGPC, 31P NMR spectra were recorded before and after cycling, revealing bulk 31P LAGP environments53 and formation of a new resonance at 10 ppm post-cycling (Fig. 4d–f, S10–11). This is indicative of a chemical reaction between LAGP and dendrites which was confirmed by solid state reaction between 6Li metal with LAGP powder (Fig. 4 d–i). This 10 ppm resonance is assigned to formation of amorphous Li3PO4 at the Li-LAGP interface, as was further supported by 31P{6Li} REDOR experiments in both solid reaction product and cycled LGPC (Fig. S11)54. The chemical interaction between the dendrites and LAGP was also confirmed in a detailed EM study (Fig. 4j, S12–14, supporting text).

Microwave on/off OE-DNP spectra of 6Li cycled a 40LGPC and b 60LGPC for the dendrite (left) and diamagnetic 6Li resonances which include SEI, LAGP and Li-PEO (right). The dendrite spectra were recorded with a recycle delay of 30 s for both microwave on and off conditions, while the diamagnetic resonances were obtained at a 3000 s and 4500 s recycle delay for microwave on and off, respectively, in 40LGPC, while both spectra were measured with 4800 s recycle delay for 60LGPC. c, d Deconvoluted microwave on/off OE-DNP spectra of 40LGPC and 60LGPC, respectively. The enhancement factors for the individual components are mentioned in the parenthesis, alongside the total SEI enhancements, which omits the ceramic and Li-PEO contributions. e, f DNP enhanced 6Li{1H} REDOR curves separated for different components in 40LGPC and 60LGPC and compared with similar profiles for PE. Errors were estimated based on the signal-to-noise ratio from the NMR spectra.

DNP enhanced spectra extracted from 6Li{1H} REDOR experiment performed on a PE, b 40LGPC, and c 60LGPC acquired with a recoupling time of 1.1 ms and a recycle delay of 60 s. The spectrum on the left was acquired without applying pulses at the 1H resonances, while the one on the right was obtained with 1H pulses. d–f 31P ssNMR spectra of pristine 40LGPC (recycle delay 200 s, 298 K), cycled 40LGPC (recycle delay 1000 s, 100 K) and 6Li metal reacted with LAGP powder (recycle delay 5 s, 298 K), respectively. g–i 6Li NMR spectra of LAGP powder (recycle delay 120 s, 298 K), cycled 40LGPC (recycle delay 60 s, 100 K and microwave on) and LAGP powder reacted with 6Li-metal (recycle delay 20 s, 298 K). j HAADF STEM-EDX elemental map of a dendrite formed in cycled 40LGPC, showing O, Ge, and P distribution and k schematic representation of the dendrite propagation pathway in PE and LGPC systems.

Based on the results obtained from dendrite quantification, isotopic enrichment and SEI analysis via OE-DNP, we propose a dendrite propagation model in PCEs and PE (Fig. 4k). In samples with up to 40 wt% LAGP, the ceramic particles disperse uniformly in the PEO matrix (“ceramic in polymer”), serving both as a physical and chemical barrier against dendrites48,55. These compositions physically restrict dendrite growth towards the opposite electrode, enhancing battery lifespan, as well as chemically blocking dendrites propagation through Li3PO4 formation within the SEI. At 60 wt% LAGP, the PCE shifts to “polymer in ceramic,” where the polymer embeds within LAGP clusters, resembling the less effective PE matrix and facilitating dendrite growth through the polymer regions. This shift is evidenced by the similar SEI characteristics observed in OE-DNP studies. Our results suggest that optimal dendrite suppression occurs at 40 wt% LAGP (Fig. 1c, d), balancing physical barriers with chemical interactions for improved battery performance.

Our OE-DNP investigation of LZPC systems revealed distinct behavior compared to LAGP, showing lower enhancement levels and an SEI made of mostly LiOH and Li2O (Figs. S15–22, supporting text). The LLZO’s interaction with the dendrites produces fewer decomposition products, suggesting its role in impeding dendrite growth in LZPC is mainly by acting as a physical barrier rather than chemical one. The higher chemical inertness of LLZO compared to LAGP is in agreement with ref. 56 This mechanism effectively prevents dendrites from short-circuiting the cell, contributing to the increased dendrite accumulation and improved cycle life and efficiency. The decreased dendrite formation observed in 60LZPC could again relate to a transition from “ceramic in polymer” to “polymer in ceramic” configurations, even though 6Li enrichment indicates significant LLZO phase enrichment.

In all electrolytes, we find that the SEI predominantly comprises Li2O and LiOH, with LGPC showing formation of Li3PO4 from LAGP decomposition. Despite similar compositions, OE-DNP enhancements of the SEI components vary significantly and consistently across PCE compositions. These differences may be related to the SEI and the dendrites properties which can vary between different PCEs and result in variation in the efficiency of OE-DNP. In the following section, we explore the process of polarization transfer from the conduction electrons to the SEI with an aim to understand the difference in SEI and dendrites properties.

Mechanistic understanding of OE-DNP within the PCEs

In OE-DNP, the transfer of electron polarization to nearby nuclei depends on effective electron-nuclear cross-relaxation processes dominated either by isotropic hyperfine or through space dipolar interactions, but not both as they lead to signal enhancement with opposite sign57. Following electron spin saturation via microwaves, cross-relaxation redistribute the spin populations, potentially increasing the NMR polarization (Figs. S23, S24). Specifically, in metals, OE-DNP occurs through isotropic hyperfine interactions (Li Knight shift, ~260 ppm) which leads to positive NMR signal enhancement42,44. The nuclei in the SEI have no isotropic hyperfine interactions and weak dipolar interactions with the conduction electrons, especially for low gamma nuclei such as 6Li. The observed positive enhancement of the SEI resonances in all cases (Figs. 2, 3 and S16, S17) rules out DNP via the dipolar mechanism and suggests indirect polarization transfer from the polarized metal nuclei, possibly through 6Li-6Li spin diffusion or Li↔Li+ charge transfer. Furthermore, heteronuclear spins (non-6,7Li) showed no OE-DNP enhancement (Figs. S25–27). To conclude whether Li-spin diffusion or Li/Li+ exchange is the main mechanism of polarization transfer, we compared the enhancement of 6Li and 7Li. If Li/Li+ exchange is predominant, the ratios between dendrite and SEI enhancements for both isotopes should be similar. Conversely, if spin diffusion governs, we expect the ratio to be lower for 7Li due to its higher dipolar coupling and spectral overlap which would facilitate efficient spin diffusion between the metal and the SEI. Notably, the enhancement ratios (εden/εsei) for 6Li and 7Li were comparable (Fig. 5a, b), supporting the predominant role of the Li/Li+ exchange in polarization transfer over spin diffusion. The slight differences in the enhancement ratios can be expected for the two isotopes due to their distinct relaxation properties in metal and SEI environments (Figs. S28, S29). These results do not rule out a minor role of direct polarization from the dendrites, which might influence the overall enhancement alongside the dominant exchange mechanism. Finally, considering the large frequency difference (15 kHz), the low magnetic moment of 6Li and use of MAS, all suggest that 6Li spin diffusion between the dendrites and SEI resonances is unlikely. This leads to the conclusion that 6Li SEI enhancement in OE-DNP mainly occurs through Li↔Li+ charge transfer. This finding is crucial for applying OE-DNP in SEI studies and importantly it suggests that the SEI enhancement in OE-DNP can be used as a proxy for the SEI Li permeability.

a 6Li (left) and b 7Li (right) microwave on /off spectra of 40LGPC cycled with 6Li metal electrodes and a comparison of the enhancement factors obtained through OE-DNP. For 6Li, dendrite spectra were acquired with a 30 s recycle delay and the SEI spectra acquired with recycle delay of 3000 s (microwave on) and 4500 s (microwave off). For 7Li, dendrite measurements were performed with 2 s recycle delay and the SEI resonances were recorded at 60 s (microwave on) and 150 s (microwave off) recycle delay. c Comparison of the CEST effect on 40LGPC and 40LZPC. d CEST effect as a function of saturation pulse length with 500 Hz RF amplitude at MAS rate of 9 KHz for LGPC and 8.5 KHz for LZPC. Error bars were estimated based on the signal-to-noise ratio from the NMR spectra. e Comparison between εsei/εden and the CEST effect (%, acquired with 60 s recycle delay) in PE, 40LGPC and 40LZPC. The dendrite enhancements for the samples are presented in the inset.

The Li-ion permeability of the SEI from DNP and Li-CEST

CEST measurements performed between Li-dendrite and SEI can offer valuable insights into the interactions (dipolar or Li/Li+ exchange) occurring between these components and provide critical insight into the mechanisms governing polarization transfer. We have recently utilized CEST (without DNP and under static conditions) to determine the rate of charge transfer across the metal-SEI interface at room temperature31. Here we keep the microwave irradiation on, so that both dendrites and SEI resonances are enhanced, followed by selective saturation of the dendrites resonance while monitoring the SEI and electrolyte signal (under MAS conditions). In the absence of spin diffusion, a reduction in the intensity of the SEI signal is attributed to Li/Li+ ion exchange between the dendrites and the SEI. Heating effects due to microwaves and radio frequency irradiation are accounted for by performing a control experiment with off-resonance saturation pulse. The resultant CEST effect is defined by the drop in SEI signal intensity upon saturating the dendrites resonance with respect to the control.

In Fig. (5c, d) significant CEST effects were observed, particularly in 40LGPC samples which showed greater effects than 40LZPC. The CEST effect increased with temperature (achieved with higher microwave power) which confirms Li/Li+ exchange, rather than spin-diffusion, as the primary polarization transfer mechanism (Figs. S30, S31). The magnitude of the CEST effect correlated nicely with the SEI enhancement (and more accurately, the ratio εsei/εden), with PE and 40LGPC showing the highest CEST effects (10–15%) and enhancement ratios (εsei/εden > 0.7) in contrast to 40LZPC with CEST effect of only 3% and low εsei/εden ratio of only 0.13 (Figs. 5e and S31, supporting text). An in-depth analysis of the variability in the enhancement factors for dendrites across different PCEs is included in the supplementary text, revealing intriguing links to dendrites morphology which will be explored in detail in future work (Fig. S32). These results confirm that the SEI Li permeability is a source of OE-DNP SEI enhancement.

Elucidating the mechanism of SEI enhancement in 6Li OE-DNP has two important implications: first, OE-DNP enhancements are predominantly observed in SEI’s inner phases that are in direct contact with dendrites, indicating high selectivity. Second, by analyzing the signal enhancement of SEI phases in 6Li OE-DNP, we can determine the SEI’s functionality as an ion conductor. We observed that the inner SEI layers formed in PE, LGPC, and LZPC exhibit similar compositions. However, their lithium-ion permeability, as deduced from OE-DNP studies, varies significantly. The SEI on PE and LGPC shows higher Li-ion permeability compared to LZPC, which is the least permeable. We also note that the presence of exchange between phases, between LiOH and the dendrites and possibly between SEI phases, can affect the REDOR curves reported above. Exchange between SEI phases would also support our conclusion regarding mosaic formation of Li2O and LiOH phases with nanometric domain sizes. In Fig. 6 we provide a summary of our findings regarding the different SEI compositions and their permeability in difference PCEs. The differences in permeability are intriguing since they suggest that while the composition of the inner SEI layers is similar, predominantly Li2O and LiOH, the formed SEI is very different in its properties, likely due to having different source for their formation (polymer or ceramics).

In summary, we performed an in-depth analysis of PCE systems, highlighting the critical link between ceramic content (LAGP and LLZO), dendrite formation and cell longevity. Combining ssNMR and enhanced sensitivity via OE-DNP allowed us to thoroughly examine the SEI formed on dendrites. This revealed their propagation path through the PCE and allowed us to uncover differences in how LAGP and LLZO mitigate dendrite growth, with LAGP chemically interacting with dendrites while LLZO primarily serving as a physical barrier. Our results suggest that 40% ceramic content is optimal for sustaining dendrites growth. By correlating 6,7Li SEI enhancements and CEST experiments, we concluded that OE-DNP facilitates effective polarization transfer in the SEI for 6,7Li isotopes via Li/Li+ exchange as the key mechanism. Importantly, this allowed us to employ OE-DNP not only for determinizing SEI composition but also to conclude about its Li permeability properties, offering a new approach to determine SEI functionality in the nano-scale.

Our research presents significant advancements in the characterization of battery technology and development of NMR methodology. We expect this methodology and results will have implications for the development of beneficial SEI layers for lithium metal-based storage systems and in guiding the design of solid electrolytes. Finally, the presented understanding of dendrites growth and mitigation may lead to enhanced performance and safety in next-generation batteries, contributing to the overall evolution of energy storage technologies.

Methods

Synthesis of Li6.4Al0.2La3Zr2O12 (LLZO)

LLZO particles were synthesized through solid-state synthesis. Li2CO3, La2O3, ZrO2, and Al2O3 were used as precursors. These precursors were dissolved in isopropanol and mixed in stoichiometric quantities by ball milling for 3 h. To account for Li evaporation during the synthesis, an excess of 4 wt% Li2CO3 was added. The resulting mixture was dried overnight in an oven at 80 °C. Next, the powder was heated at 950 °C for 10 h (heating rate 5 °C/min) in air. After the synthesis, the LLZO powder was dried at 100 °C for 12 h in a vacuum oven and was stored in an Ar-filled glovebox for further use in subsequent experiments.

Synthesis of Li1.5Al0.5Ge1.5(PO4)3 (LAGP)

In a standard synthesis procedure, stoichiometric quantities of Li2CO3 (with an additional 10 wt% to account for Li evaporation), Al2O3, GeO2, and (NH4)H2PO4 were combined and subjected to ball milling for 2 h. Subsequently, the mixture was heated sequentially: first, at a heating rate of 5 °C/min, it was heated to 600 °C for 1 h in an air atmosphere, followed by further heating to 900 °C and for 9 h. After completion of the heating steps, the sample was ball milled for 3 h and then dried at 100 °C for 12 h in a vacuum oven and subsequently stored in an argon-filled glovebox.

Preparation of polymeric composite electrolyte (PCE)

The polymer-ceramic electrolytes (PCEs) were prepared using a solution-based casting method within a glovebox environment. The components involved in the preparation were PEO (Mw ~ 600,000), LiTFSI, and ceramic particles (LLZO or LAGP). Dry acetonitrile served as the solvent during the mixing process. The resulting gel was cast into a Teflon mold and subsequently dried under vacuum at 50 °C to remove any trace amount of acetonitrile. In all experiments, the molar ratio of [EO] (ethylene oxide units) to [Li+] was maintained at 18:1. The dried PCEs were directly utilized for fabricating Li-metal symmetric cells.

Electrochemistry of the PCEs

For the galvanostatic cycling study, symmetric coin cells of type 2032 were prepared. These cells consisted of two 7Li-metal electrodes with a thickness of approximately 400 µm, purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (purity 99.9%). Before assembling the symmetric cells, the surface of the Li metal was brushed with a clean toothbrush until it became clean and shiny. Following the cleaning process, the Li metal foil was punched into a circular shape with a diameter of 11 mm, which was directly used for making the symmetric cells. This entire process was conducted within an argon-filled glove box. After assembly, the batteries underwent a thermal treatment at 80 °C for 3 h, followed by a resting period of 1 h at 30 °C to stabilize. The electrochemical energy storage tests were performed in a closed cabinet at a temperature range of 28–30 °C. Subsequently, the cells were subjected to galvanostatic cycling tests at a current density of 0.05 mA/cm2 using a Neware BTS-4000 Series tester. All the cycling experiments were conducted at a temperature of 30 °C. The charge and discharge durations were set to 1 h, and a cut-off voltage of 1 V was implemented. For higher current densities of 0.125 mA/cm² and 0.25 mA/cm², the cut-off limits were extended to 4 V. All the cells were assembled without a separate separator, as the solid polymer electrolyte served a dual purpose, functioning both as the electrolyte and the separator.

Dendrite quantification measurements

In the sample preparation process, the symmetric cells containing the composites were subjected to cycling at a current density of 0.125 mA/cm2, with a cut-off voltage of 4 V. The cycling was performed continuously for a duration of 100 h. After completing the cycling procedure, the coin cells were opened in the glove box, and the entire cell including the Li-metal electrodes was transferred to a closed in-situ NMR cell. For Li-dendrite quantification, the in-situ cells containing the samples were directly placed inside the NMR probe. The 7Li solid-state NMR measurements were conducted under static conditions using a 9.4T Bruker Avance Neo 400 MHz wide bore spectrometer at a temperature of 25 °C. The chemical shift scale and π/2 pulse (nutation frequency of 25 kHz) for 7Li were calibrated on LiF powder as a reference.

The6,7Li ssNMR spectra of cycled cells contain the electrolyte region at 0 ppm and a metallic/dendritic region at 260 ppm (Fig. S3). For quantification the signal at 260 ppm, which includes both the formed dendrites and the partially excited Li-metal electrode surface, was integrated. The Li metal surface area contributing to the signal stays consistent across samples due to the constant RF penetration depth46,47, whereas the changes in the integrated intensity are attributed to the addition of dendrites. The dendrites contribution is quantitative as their low thickness enables their full excitation by the radio frequency pulses.

Sample preparation for MAS-DNP

In the DNP experiments, the PCEs were subjected to cycling at a current density of 0.250 mA/cm2 for approximately 50 h at 30 °C. Subsequently, the cycled PCEs were carefully extracted after opening the battery cell. The extracted PCE samples were directly packed in an argon glove box into the sealed 3.2 mm sapphire rotor for further analysis. This resulted in only dendritic lithium microstructures included in the DNP measurements in contrast to the quantification experiments.

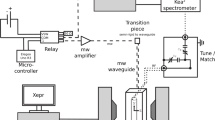

Magic angle spinning (MAS) DNP ssNMR measurements

DNP experiments were conducted on a Bruker 9.4 T Avance-Neo spectrometer equipped with a sweep coil and a 263 GHz gyrotron system. For the experiments, 3.2 mm triple and double resonance low-temperature DNP probes were utilized. The experiments were carried out with sample temperature reaching ~98 K and 109 K without and with microwave irradiation, respectively.

The longitudinal relaxation time (T1) and the polarization buildup time with microwave irradiation (Tbu) were determined using a saturation recovery pulse sequence with 40 saturation pulses separated by 0.2 ms delays.1H experiments were acquired using a rotor synchronized Hahn echo sequence.

NMR data processing

All NMR data analysis, deconvolution, and fitting were carried out using Bruker TopSpin and DMfit software58. The deconvolution analysis in DMfit was performed using the Gaussian-Lorentzian model.

SEM analysis

SEM imaging and EDX mapping of the PCEs were conducted on Zeiss-Sigma FESEM instrument. After the cycling process, the samples were transferred to an argon filled airlock box and subsequently swiftly transferred to the SEM holder, minimizing exposure to air.

TEM Analysis

HRTEM and STEM-HAADF EDX studies were performed on Talos F200X G2 model. The TEM grids (Lacey carbon 400 Mesh copper) were placed inside the battery, allowing the PCEs to cycle alongside them. After disassembling the battery, the TEM grids were carefully retrieved and utilized for the subsequent TEM analysis. Here also the samples were carried to the facility using argon filled airlock box and quickly transferred to the instrument with minimal exposure to the air.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. The raw data are available in WIS Works, the Weizmann Institutional Repository at https://doi.org/10.34933/3cb6420a-347e-459c-99cb-d095f2f2df80.

References

Winter, M., Barnett, B. & Xu, K. Before Li ion batteries. Chem. Rev. 118, 11433–11456 (2018).

Manthiram, A. An outlook on lithium ion battery technology. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 1063–1069 (2017).

Grey, C. P. & Hall, D. S. Prospects for lithium-ion batteries and beyond—a 2030 vision. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–4 (2020).

Peled, E. & Menkin, S. Review—SEI: past, present and future. J. Electrochem Soc. 164, A1703–A1719 (2017).

Horstmann, B. et al. Strategies towards enabling lithium metal in batteries: interphases and electrodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 5289–5314 (2021).

Hobold, G. M. & Gallant, B. M. Quantifying capacity loss mechanisms of Li metal anodes beyond inactive Li0. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 3458–3466 (2022).

Wood, K. N., Noked, M. & Dasgupta, N. P. Lithium metal anodes: toward an improved understanding of coupled morphological, electrochemical, and mechanical behavior. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 664–672 (2017).

Cheng, X. B., Zhang, R., Zhao, C. Z. & Zhang, Q. Toward safe lithium metal anode in rechargeable batteries: a review. Chem. Rev. 117, 10403–10473 (2017).

Choi, J. W. & Aurbach, D. Promise and reality of post-lithium-ion batteries with high energy densities. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 1–16 (2016). 2016 1:4.

Thenuwara, A. C., Shetty, P. P. & McDowell, M. T. Distinct nanoscale interphases and morphology of lithium metal electrodes operating at low temperatures. Nano Lett. 19, 8664–8672 (2019).

Zhang, S. S. Problem, status, and possible solutions for lithium metal anode of rechargeable batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 1, 910–920 (2018).

Lin, D., Liu, Y. & Cui, Y. Reviving the lithium metal anode for high-energy batteries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 194–206 (2017).

Wood, K. N. et al. Dendrites and pits: untangling the complex behavior of lithium metal anodes through operando video microscopy. ACS Cent. Sci. 2, 790–801 (2016).

Xu, W. et al. Lithium metal anodes for rechargeable batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 513–537 (2014).

Fenton, D. E., Parker, J. M. & Wright, P. V. Complexes of alkali metal ions with poly(ethylene oxide). Polymer 14, 589 (1973).

Kelly, I. E., Owen, J. R. & Steele, B. C. H. Poly(ethylene oxide) electrolytes for operation at near room temperature. J. Power Sources 14, 13–21 (1985).

Zhao, Y. et al. Solid polymer electrolytes with high conductivity and transference number of Li Ions for Li-based rechargeable batteries. Adv. Sci. 8, 2003675 (2021).

Yu, X. & Manthiram, A. A review of composite polymer-ceramic electrolytes for lithium batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 34, 282–300 (2021).

Tamainato, S., Mori, D., Takeda, Y., Yamamoto, O. & Imanishi, N. Composite polymer electrolytes for lithium batteries. ChemistrySelect 7, e202201667 (2022).

Ge, X., Zhang, F., Wu, L., Yang, Z. & Xu, T. Current challenges and perspectives of polymer electrolyte membranes. Macromolecules 55, 3773–3787 (2022).

Zhou, D. et al. Performance and behavior of LLZO-based composite polymer electrolyte for lithium metal electrode with high capacity utilization. Nano Energy 77, 105196 (2020).

Ren, Y., Zhou, Y. & Cao, Y. Inhibit of lithium dendrite growth in solid composite electrolyte by phase-field modeling. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 12195–12204 (2020).

Zagórski, J. et al. Garnet-polymer composite electrolytes: new insights on local Li-ion dynamics and electrodeposition stability with Li metal anodes. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2, 1734–1746 (2019).

Wu, B., Lochala, J., Taverne, T. & Xiao, J. The interplay between solid electrolyte interface (SEI) and dendritic lithium growth. Nano Energy 40, 34–41 (2017).

Xu, K. Interfaces and interphases in batteries. J. Power Sources 559, 232652 (2023).

Wood, K. N. & Teeter, G. XPS on Li-battery-related compounds: analysis of inorganic SEI phases and a methodology for charge correction. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 1, 4493–4504 (2018).

Wi, T. U. et al. Revealing the dual-layered solid electrolyte interphase on lithium metal anodes via cryogenic electron microscopy. ACS Energy Lett. 3, 2193–2200 (2023).

Zhai, W. et al. Microstructure of lithium dendrites revealed by room-temperature electron microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 4124–4132 (2022).

Bhattacharyya, R. et al. In situ NMR observation of the formation of metallic lithium microstructures in lithium batteries. Nat. Mater. 9, 504–510 (2010).

Haber, S. & Leskes, M. Dynamic nuclear polarization in battery materials. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson 117, 101763 (2022).

Columbus, D. et al. Direct detection of lithium exchange across the solid electrolyte interphase by 7Li chemical exchange saturation transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 9836–9844 (2022).

Gunnarsdóttir, A. B., Vema, S., Menkin, S., Marbella, L. E. & Grey, C. P. Investigating the effect of a fluoroethylene carbonate additive on lithium deposition and the solid electrolyte interphase in lithium metal batteries using in situ NMR spectroscopy. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 8, 14975–14992 (2020).

Ilott, A. J. & Jerschow, A. Probing solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) growth and ion permeability at undriven electrolyte-metal interfaces using 7Li NMR. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 12598–12604 (2018).

Rossini, A. J. et al. Dynamic nuclear polarization surface enhanced NMR spectroscopy. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 1942–1951 (2013).

Maly, T. et al. Dynamic nuclear polarization at high magnetic fields. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 52211 (2008).

Lilly Thankamony, A. S., Wittmann, J. J., Kaushik, M. & Corzilius, B. Dynamic nuclear polarization for sensitivity enhancement in modern solid-state NMR. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 102–103, 120–195 (2017).

Moroz, I. B. & Leskes, M. Dynamic nuclear polarization solid-state nmr spectroscopy for materials research. Annu Rev. Mater. Res 52, 25–55 (2022).

Haber, S. et al. Structure and functionality of an alkylated LixSiyOz interphase for high-energy cathodes from DNP-ssNMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 4694–4704 (2021).

Leskes, M. et al. Surface-sensitive NMR detection of the solid electrolyte interphase layer on reduced graphene oxide. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 1078–1085 (2017).

Jin, Y. et al. Understanding fluoroethylene carbonate and vinylene carbonate based electrolytes for Si anodes in lithium ion batteries with NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 9854–9867 (2018).

Wolf, T. et al. Endogenous dynamic nuclear polarization for natural abundance 17 O and lithium NMR in the bulk of inorganic solids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 451–462 (2019).

Overhauser, A. W. Polarization of nuclei in metals. Phys. Rev. 92, 411 (1953).

Carver, T. R. & Slichter, C. P. Experimental verification of the overhauser nuclear polarization effect. Phys. Rev. 102, 975 (1956).

Hope, M. A. et al. Selective NMR observation of the SEI–metal interface by dynamic nuclear polarisation from lithium metal. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–8 (2020).

Zheng, J., Tang, M. & Hu, Y. Y. Lithium ion pathway within Li7La3Zr2O12-polyethylene oxide composite electrolytes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 12538–12542 (2016).

Ilott, A. J. et al. Visualizing skin effects in conductors with MRI: 7Li MRI experiments and calculations. J. Magn. Reson. 245, 143–149 (2014).

Trease, N. M., Zhou, L., Chang, H. J., Zhu, B. Y. & Grey, C. P. In situ NMR of lithium-ion batteries: bulk susceptibility effects and practical considerations. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 42, 62–70 (2012).

Liu, M. et al. Tandem interface and bulk Li-ion transport in a hybrid solid electrolyte with microsized active filler. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 2336–2342 (2019).

Fritsch, C. et al. Garnet to hydrogarnet: effect of post synthesis treatment on cation substituted LLZO solid electrolyte and its effect on Li ion conductivity. RSC Adv. 11, 30283–30294 (2021).

Meyer, T., Gutel, T., Manzanarez, H., Bardet, M. & De Vito, E. Lithium self-diffusion in a polymer electrolyte for solid-state batteries: ToF-SIMS/ssNMR correlative characterization and modeling based on lithium isotopic labeling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 44268–44279 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Investigation of polymer/ceramic composite solid electrolyte system: the case of PEO/LGPS composite electrolytes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 11314–11322 (2021).

Leskes, M., Moore, A. J., Goward, G. R. & Grey, C. P. Monitoring the electrochemical processes in the lithium-air battery by solid state NMR spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117, 26929–26939 (2013).

Pershina, S. V., Dzuba, M. Y., Vlasova, S. G. & Baklanova, Y. V. Structural investigations of Li1.5Al0.5Ge1.5(PO4)3 glass-ceramics by solid-state NMR. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. vol. 1347 (Institute of Physics Publishing, 2019).

Marple, M. A. T. et al. Local structure of glassy lithium phosphorus oxynitride thin films: a combined experimental and ab initio approach. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22185–22193 (2020).

Chen, L. et al. PEO/garnet composite electrolytes for solid-state lithium batteries: from “ceramic-in-polymer” to “polymer-in-ceramic. Nano Energy 46, 176–184 (2018).

Chen, R. et al. The thermal stability of lithium solid electrolytes with metallic lithium. Joule 4, 812–821 (2020).

Bennati, M. & Orlando, T. Overhauser DNP in liquids on 13C nuclei. eMagRes 8, 11–18 (2019).

Massiot, D. et al. Modelling one- and two-dimensional solid-state NMR spectra. Magn. Reson. Chem. 40, 70–76 (2002).

Acknowledgements

A.M. is supported by the Israel academy of Sciences and Humanities and by an excellence fellowship from the Weizmann institute of science. This research was funded by the European Research Council (SEISPY), the Israel Science Foundation (ISF) grant number 2331/22 and by the Minerva foundation with funding from the Federal German Ministry for Education and Research. We also acknowledge the generous support by a research grant from the Adolfo Eric Labi Fund for Research on High-Energy Storage Systems, Henri Gutwirth Fund for Research and Sagol Weizmann-MIT Bridge Program. The work was made possible in part by the historic generosity of the Harold Perlman family.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L., A.M. and A.S.A conceived the experiments. A.M. performed all the experiments and analyzed the data, A.S.A performed the initial OE-DNP experiments and wrote the first draft. C.O. and Y.B. performed preliminary experiments and contributed to the design of the materials. M.L. and A.M. wrote the manuscript, with input and approval from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Kuizhi Chen and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maity, A., Svirinovsky-Arbeli, A., Buganim, Y. et al. Tracking dendrites and solid electrolyte interphase formation with dynamic nuclear polarization—NMR spectroscopy. Nat Commun 15, 9956 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54315-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54315-w