Abstract

The intricate hydrogen-bonded network of water gives rise to various structures with anomalous properties at different thermodynamic conditions. Nanoconfinement can further modify the water structure and properties, and induce specific water motifs, which are instrumental for technological applications such as atmospheric water harvesting. However, so far, a causal relationship between nanoconfinement and the presence of specific hydrophilic adsorption sites is lacking, hampering the further design of nanostructured materials for water templating. Therefore, this work investigates the organisation of water in zirconium-based metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) with varying topologies, pore sizes, and chemical composition, to extract design rules to shape water. The highly tuneable pores and hydrophilicity of MOFs makes them ideally suited for this purpose. We find that small nanopores favour orderly water clusters that nucleate at hydrophilic adsorption sites. Favourably positioning the secondary adsorption sites, hydrogen-bonded to the primary adsorption sites, allows larger clusters to form at moderate adsorption conditions. To disentangle the importance of nanoconfinement and hydrophilic nucleation sites in this process, we introduce an analytical model with precise control of the adsorption sites. This sheds a new light on design parameters to induce specific water clusters and hydrogen-bonded networks, thus rationalising the application space of water in nanoconfinement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liquid water is well-known for its anomalous behaviour in comparison with other liquids, including a density maximum at 4 ∘C—resulting in the famous expansion upon freezing—and a high surface tension1. These anomalies are linked with the unusual structure of water, which is determined by an intricate network of hydrogen bonds2,3. At lower temperatures, the hydrogen bond networks manifest most orderly in ice crystals4 or in clathrate hydrates, which are ice-like cage structures that encapsulate clean energy vectors such as methane or hydrogen5,6. When confining water molecules to nanosized pores or channels, the hydrogen bond network can be heavily disrupted, thereby significantly altering the physical properties of nanoconfined water compared to bulk water. A reduced dielectric constant can for instance persist in water layers up to 100 nm before recovering bulk behaviour7. A thorough understanding of the different factors that influence the nanoconfined water’s intricate hydrogen bond network is critical to exploit these unusual properties towards practical applications such as water harvesting8,9,10 or shock absorbers11. Herein, we further contribute to such understanding by systematically investigating the origins of different hydrogen bond motifs in structurally nanoconfined water.

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) were one of the first materials investigated in the context of water confinement. Depending on the nanotube diameter and thermodynamic conditions, water molecules in CNTs were reported to form one-dimensional hydrogen-bonded chains along the hydrophobic nanotubes12,13, as well as shell-chain structures with a cylindrical square-ice shell surrounding the water chain14, or structured stackings of n-membered water rings15,16. The one-dimensional cylindrical confinement of water thus induces the formation of ice-like phases which are unstable in a bulk phase and possess altered properties such as an enhanced diffusion rate. In the case of two-dimensional water confinement, for instance between two graphene sheets, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurements showed the existence of a square-ice phase, which deviates from the tetrahedral hydrogen bond coordination of bulk ice17. For the specific case of a monolayer of nanoconfined water, Kapil et al.18 demonstrated that the phase diagram also contains other stable polymorphs of ice, such as hexagonal, pentagonal, and hexatic ice.

Over the past few years, water confined in three-dimensional nanostructures has systematically gained more attention in view of several applications. To exploit the extraordinary properties of three-dimensionally confined water, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are ideal host materials, thanks to their highly tunable nature19,20,21. Their modular composition of metal nodes and organic linkers gives rise to a wide variation in water-confining environments so that they can be tailored for various applications. Just as in the case of one- and two-dimensional confinement of water, also three-dimensionally confined water in the pores of MOFs behaves differently from bulk water. In flexible MOFs, such as MIL-53(Ga), water adsorption can induce new phases besides the narrow- and large-pore phases known for the empty framework22. Furthermore, the confinement of water in MOFs is also known to slow down the water reorientation dynamics and affect the hydrogen bond network, along with the related tetrahedral order22,23.

The most notable opportunities three-dimensional water confinement in MOFs offers are atmospheric water harvesting8,9,10, water purification24,25,26, shock absorption11, and adsorbent-based heat pumps and chillers with water as a green working fluid27,28,29. Some frameworks with a hydrophobic character, such as the zeolitic imidazolate framework ZIF-8, possess the ability to function as shock absorbers due to their resistance to water intrusion. In ZIF-8, the spontaneous intrusion of water requires the formation of water clusters with a critical number of molecules to start filling one of the nanopores. If the strain rate of the water intrusion exceeds the intrinsic rate for the nucleation of critical-sized water clusters, the high-rate mechanical impact is attenuated as a consequence of the energy dissipated in the forced intrusion process11.

In many MOFs, however, both hydrophilic and hydrophobic sites are present, which determine the specific adsorption behaviour of the material. The aromatic linkers are typically hydrophobic, while open metal sites and μ-OH groups are hydrophilic and act as nucleation sites in the formation of water clusters30,31. This initial step in the water adsorption process was labelled the seeding stage by Hanikel et al.32 in the analysis of water adsorption in MOF-303, a MOF that is exceptionally well suited for atmospheric water harvesting. After the seeding stage, water adsorption in MOF-303 continues through a clustering and networking stage, during which the first adsorbed water molecules grow into clusters and eventually unite into an extended hydrogen-bonded water network. This adsorption mechanism occurs in many MOFs (e.g. CAU-10-H31, MOF-80127,33,34, MIL-10135, Co2Cl2BTDD23), as well as in the purely covalently bonded equivalent of MOFs, known as covalent organic frameworks (COFs)36.

During the seeding stage, the hydrophilic sites in the framework play a decisive role, which can be easily demonstrated by the addition or removal of such sites. When pyrazole is substituted by less hydrophilic furan32 or thiophene37 in MOF-303, the primary water adsorption sites of the framework are altered, which diminishes the water uptake at low relative humidities. Similarly, the incorporation of hydrophilic linker functionalities for UiO-66 enhances the water uptake at low pressures, whereas incorporating hydrophobic linker functionalities has the opposite effect38,39.

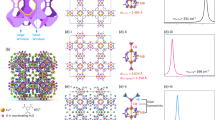

In this work, we present a systematic investigation of how the meticulous tuning of nanoconfinement, hydrophobic, and hydrophilic sites may induce the formation of particular water clusters. To this end, a series of zirconium MOFs with different topologies but similar building units are considered, including UiO-66, UiO-67, UiO-68, MOF-801, MOF-808, MOF-841, and NU-1000, as shown in Fig. 1. This specific choice of materials allows to evaluate the influence of varying pore sizes (see Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1) and degrees of hydrophilicity on the water organisation in highly similar frameworks. MOF-801, UiO-66, UiO-67, and UiO-68 share for instance the same topology and metal nodes, which are connected by linkers of different lengths, leading to various degrees of confinement. The selected systems can thus be seen as model systems for highly tunable nanostructures, which enable a systematic investigation of the features affecting the organisation of nanoconfined water.

The pores of each framework are indicated with coloured spheres and the corresponding pore diameters are listed below the figure. Note that the structure of NU-1000 is rescaled with a factor of 0.65 compared to the other structures. Hydrogen atoms are depicted in white, carbon in grey, oxygen in red, and zirconium in cyan.

Using different structural identifiers, water confined in the smaller MOFs is shown to deviate substantially from bulk water, as the structural organisation of water is strongly templated by the host framework. To disentangle the role of confinement and the importance of hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions within the framework, an analytical model is constructed to rationalise the observed behaviour in the MOFs. This model provides a more fundamental insight into the strong interplay between primary and secondary adsorption sites in MOF-801 and UiO-66, which can significantly influence the clustering and networking stages during water adsorption and thus shape the water adsorption isotherms. This understanding can be used to further guide the design of tunable nanostructures for applications that involve water confinement.

Results

For each of the zirconium MOFs in Fig. 1 different water loadings are investigated, with a maximal loading determined from grand canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulations at 1 bar and 300 K. As explained in more detail in the Methods section, path integral molecular dynamics (PIMD) simulations are performed to determine the structural properties of the confined water. The computationally more expensive path integral formalism is used as water molecules are prone to nuclear quantum effects (NQEs), which can significantly affect the description of hydrogen bonds40. When introducing water molecules in the nanoporous frameworks, each MOF exhibits a cell volume contraction (see Supplementary Fig. 2). Initially, this contraction increases with the number of water molecules until a relative volume reduction of about 2% is reached. When more guests are added to the framework, the material starts to expand again and can exceed the unit cell volume of the empty framework.

To capture the structural organisation of a network of water molecules, one can consider the number of hydrogen bonds in which each molecule participates. In Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3 the probability of different hydrogen bond connectivities is shown for the different frameworks with various water loadings alongside the reference distribution of bulk water. For bulk liquid water, every molecule tends to partake on average in 2.7 hydrogen bonds, as configurations with 2 to 4 hydrogen bonds are most likely. For confined water, the hydrogen bond network can be heavily disrupted by the confining framework depending on the size of the pores. When few water molecules are present, the hydrogen bond distribution is skewed towards 0 or 1, as only a limited number of hydrogen bonds can be formed. For higher water loadings, the influence of the framework becomes apparent for smaller frameworks such as UiO-66, MOF-801, and MOF-841, as their hydrogen bond distribution does not converge to the one of bulk water. The materials with larger nanopores, such as UiO-67, UiO-68, MOF-808, and NU-1000, do show hydrogen bond distributions similar to liquid water.

Structural information beyond the first solvation shell around every water molecule can be obtained from radial distribution functions (RDFs) of the oxygen atoms (see Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4). The first peak of the RDF represents neighbouring water molecules and thus provides similar information as the hydrogen bond distributions. In comparison with ordinary liquid water, this peak is mainly modulated in intensity, whereas its shape and position are only minorly different. The first minimum, on the contrary, does show an appreciable shift for the smaller UiO-66 and MOF-801 frameworks of respectively, 0.2 Å and 0.4 Å towards larger interatomic distances. As MOF-801 has the smallest pores, the structural perturbation is clearly most pronounced for this framework, yielding a broader and flatter minimum. This perturbation also pervades the second solvation shell represented by the second RDF peak, which becomes sharper than in bulk water and is shifted to larger distances by 0.4–0.5 Å. For frameworks containing larger pores, such as UiO-67 and MOF-808, the RDF is observed to closely approach the bulk equivalent for larger water loadings, with only small shifts in the peak positions of about 0.15 Å.

For each framework, a gradient colour scale is used to indicate the water loading in the unit cell. The O--O RDF of bulk water is indicated with a grey dashed line. The insets for UiO-66 and MOF-801 (labelled 1--3) show the contributions of representative O--O pairs to the second peak of the RDF. The inset for UiO-67 shows the bulk-like shell structure in the octahedral pore.

The origin of the deviating structural organisation of water in the MOF’s nanopores can be traced back to the formation of clusters that nucleate at hydrophilic sites. Particular contributions of the clusters to the RDFs of UiO-66 and MOF-801 are shown in the insets of Fig. 3 and in Supplementary Fig. 5. To visualise the preferential adsorption sites and the structures that emerge from it, the water density in the MOFs is shown for different slabs in Fig. 4a and Supplementary Figs. 6–9. A schematic representation of the MOFs with an fcu topology is also depicted in Fig. 4a, with the tetrahedral pores indicated in green and pink, whereas the octahedral pore of the framework is filled with an orange sphere. Two types of tetrahedral pores are present, with respectively μ-OH groups (green pores, labelled T1) or μ-O groups (pink pores, labelled T2) on the cornering metal clusters. For MOF-801, distinct geometrical water patterns can be discerned, which closely reflect the framework’s structure. In the tetrahedral T1 pores, the cornering μ-OH groups serve as anchor points for the formation of a cubic structure that was also resolved experimentally by Furukawa et al. through X-ray diffraction33. Starting from the adsorbed water molecules at the four μ-OH groups within the pore (site 1 in Fig. 4a), the cube is completed by additional water molecules that hydrogen bond to these anchor points (site 2 in Fig. 4a). Furthermore, these additional water molecules, in their turn, can engage in a hydrogen bond that connects the tetrahedral pore with the neighbouring octahedral pore (site 3 in Fig. 4a). At lower water loadings, the tetrahedral pore of MOF-801 can also accommodate a square cluster instead of a cubic cluster, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7.

a considers the water density in different MOFs, whereras b considers a repulsive cubic box (see "Methods" section). a also contains a schematic representation of a water-filled MOF, with examples of the water clusters present in the T1 and T2 pores. The different adsorption sites are labelled as follows: (1) adsorbed at a μ-OH group of the metal node, (2) hydrogen-bonded to sites 1, (3) connecting tetrahedral and octahedral pores, and (4) adsorbed at a μ-O group of the metal node (see also Supplementary Fig. 10). Densities lower than 0.001 g/cm3 are attributed the colour black. The densities of the MOFs are symmetrized using the space group of the framework (see Supplementary Note 8) so that only four slabs of one half of the framework are shown. The densities of the repulsive cubic boxes are symmetrised using the P\(\overline{4}\)3m space group so that only the density in the top half of the box is shown. The box has a side L = 8 Å and adsorption sites with a strength of K = 20 kJ/mol. Results for different box parameters are reported in Supplementary Note 10.

When increasing the pore size by going from MOF-801 to UiO-66, thus increasing the diameter of the tetrahedral pore by about 2 Å (by changing the fumarate linkers by benzenedicarboxylate linkers), two different density profiles appear within the T1- and T2-type tetrahedral pores (in Fig. 4a). The T1-type pore still accommodates cubic water clusters that nucleate at the μ-OH groups located in the corners of the pore. The T2-type pore, on the contrary, has μ-O instead of μ-OH groups in its corners, which displaces the primary adsorption sites. In the T2-type pores, the primary adsorption sites are located closer to the corners (site 4 in Fig. 4a), which misaligns the nucleation points for a pore-filling cubic water cluster. The absence of an optimal water cluster to fill the pore results in more freedom for the hydrogen bonds formed with the adsorption sites, which is reflected in the reduced and dispersed density surrounding these sites. For MOF-801, by contrast, the smaller size of the tetrahedral pores allows to also stabilise the cubic water cluster in the T2-type pore, as the adsorption sites are located closer to the centre of the pore and thus provide the required hydrogen bonds to complete the cube (just as in the T1-type pore). Note that a distinction in adsorption sites between the tetrahedral pores was also experimentally observed by Furukawa et al.33, but the difference in adsorption sites was not resolved atomically with respect to the patterns induced by the specific terminations of the metal nodes.

To rationalise the adsorption behaviour in a confined environment such as MOF-801 or UiO-66, an analytical potential was used to separate the effects of geometrical confinement from the presence of hydrophilic adsorption sites. To this end, a repulsive cubic box with different side lengths was used, which contains either no adsorption sites, tetrahedrally arranged adsorption sites, or cubically arranged adsorption sites (see Fig. 4b, Supplementary Note 10, and the Methods Section). In the absence of hydrophilic sites (Supplementary Fig. 18), a collection of eight water molecules only takes on a cubic shape for very small box lengths (smaller than 6 Å). As the water molecules are located closely near the edges of the box, attempting to escape the box, it is rather unlikely that this number of water molecules would be present in a realistic pore. In the presence of tetrahedrally arranged hydrophilic sites, the adsorption patterns observed in UiO-66 can be reproduced with an appropriate placement of the adsorption sites (Supplementary Figs. 19–26). For box lengths varying from 6 to 10 Å, a cubic water cluster is formed when the tetrahedral adsorption sites outline a cube with a side of about 3 Å. In this case, the corners of the cube which do not contain an adsorption site are located at a hydrogen bond distance from the tetrahedral adsorption sites, thus favouring the formation of a cubic water cluster. If the adsorption sites are further apart and define a cube with a side of about 4 Å, the tetrahedral arrangement of the T2-type pores in UiO-66 is retrieved. When the tetrahedrally arranged hydrophilic sites are replaced by a cubical arrangement, the cubic water clusters can be stabilised at lower adsorption energies and over a wider range of distances (i.e. a cube with a side of about 3–4 Å). This analytical model therefore not only demonstrates the importance of hydrophilic sites in the formation of water clusters, but also a possible design principle in which a set of primary adsorption sites outlines a larger cluster with secondary adsorption sites located at hydrogen bond distances from the primary sites. By exploiting this principle, it is also possible to construct larger clusters as shown in Supplementary Figs. 28–29.

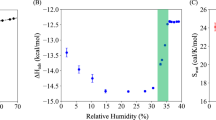

The interplay between primary and secondary adsorption sites also strongly influences the water adsorption behaviour. In the context of atmospheric water harvesting, the ideal adsorption behaviour is characterised by a step-shaped isotherm with a steep uptake at a relative pressure between 0.1 and 0.3, to allow for an easy adsorption at low pressures while retaining moderate regeneration conditions8,41. In Fig. 5, water adsorption isotherms are shown for a virtual cubic pore with a side of 6 Å and tetrahedrally arranged adsorption sites at different positions. With the aid of secondary adsorption sites, the desired adsorption behaviour for atmospheric water harvesting can be retrieved for primary adsorption sites with a moderate strength of 35 kJ/mol. In the absence of secondary adsorption sites, a larger spacing between the adsorption sites is observed to flatten the isotherm, whereas a closer spacing of the sites shifts the isotherm to lower relative pressures. Both mechanisms significantly reduce the working capacity of the virtual pore. A more elaborate discussion of the influence of different parameters on the adsorption isotherms, including the adsorption strength, is given in Supplementary Note 10.2.

A further increase of the pore size by going from UiO-66 to UiO-67 yields a more attenuated image of the water density (Fig. 4a). The μ-OH groups in the T1-type pores remain preferential adsorption sites that can branch out cubically, thus preserving a specific order within the additional spatial freedom of the larger pore. A unique cubic cluster as in the T1-type pores of UiO-66 is however no longer present. In the T2-type pores, the spatial freedom further thins the water density, although the adsorption sites near the corners of the pore are still clearly visible. For UiO-68, the trend associated with increasing pore sizes continues, with a more diluted density in the pores that remain pierced by the adsorption sites (Supplementary Fig. 6). Alternatively, the pore size of UiO-66 can also be increased by introducing defects in the framework. By removing one or two linkers in the model of UiO-66, along with the protons on the connected zirconium bricks for charge balance, some primary adsorption sites change from μ-OH to μ-O, so that together with the increase in pore size the preferential secondary adsorption sites disappear (Supplementary Fig. 9). A specific organisation of water in clusters is therefore only to be expected for MOFs with appropriately tuned pore sizes and favourably located hydrophilic sites, which are key features in the design and performance of atmospheric MOF water harvesters.

Similarly to MOF-801 and UiO-66, other framework-induced water motifs can be observed in zirconium MOFs with a different topology. In the tetrahedral MOF-841 crystal, the μ-O and μ-OH adsorption sites are again surrounded by a second layer of adsorbed water molecules, but are no longer enclosed in a cubical pore (Supplementary Fig. 6). In MOF-808, the μ-O(H) adsorption sites are located both in the smaller tetrahedral pores and in the large adamantane cages, which yields a layer of water molecules that envelops the framework. In the larger pores, just as for UiO-68, the spatial freedom of the molecules dilutes the density. Also in NU-1000 (Supplementary Fig. 8), a specific clustered water organisation is absent in the large pores, but in the space confined between the linkers, ring-like structures can be discerned.

As illustrated by this selection of zirconium MOFs, structured water clusters can be formed within MOFs in the presence of hydrophilic adsorption sites. If the confining pore is sufficiently small, it fully templates the hydrogen-bonded network of water molecules it contains. Another example of this behaviour is for instance given by the one-dimensional water wires that are present in the narrow-pore phase of MIL-5342,43. However, when the volume of the framework increases and the material transitions to the large-pore phase, the larger pores can adsorb more water molecules and a more disordered water network replaces the water wires. Also in Co2Cl2BTDD water wires are formed, which nucleate at the open metal sites of the framework and instigate the subsequent pore-filling process23. In PCP-1, an ordered stacking of two-dimensional square water structures was revealed with single-crystal X-ray diffraction44, which demonstrates once more the possibility to form ice-like ordered structures at room temperature. In CAU-10-H, a water cluster is built around a double pentamer, which cannot be hosted in CAU-10-CH3 due to the presence of the methyl groups31.

Additional information about the substructure of the hydrogen-bonded network can be obtained by means of a graph search for specific structures. More particularly, one can scan the network for square, pentagonal, and hexagonal ring structures, which are the constituents of clathrate hydrates or ice4,5. In bulk water, the pentagonal and hexagonal rings are more prevalent than the square ones, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 14–16. In confinement, the pore size and shape determine the relative occurrence of the different ring structures. The small tetrahedral pores in UiO-66 and MOF-801 result in a larger amount of square rings, which makes them equally or more prevalent than the larger pentagonal and hexagonal rings. When the pore size of the framework increases, the bulk-like behaviour re-emerges for high water loadings and the pentagonal and hexagonal rings are again most numerously present.

Discussion

Using a diverse set of zirconium MOFs, with similar building units but varying topologies and pore sizes, the organisation of water in different nanoconfining environments was systematically investigated to unravel to which extent water can be templated by the host framework. Only for large pores, the bulk-like behaviour of water can be retrieved. In the smaller pores, the network of water molecules—and the resulting properties—are shaped by the pore that hosts them. To form orderly water clusters in a pore, hydrophilic adsorption sites play a pivotal role, as demonstrated by the analytical model that was devised in this work. Besides the importance of hydrophilic sites in the nucleation of water clusters, they may also induce secondary adsorption sites through hydrogen bonding, which allows for the construction of larger orderly water clusters with a limited number of hydrophilic sites. The cubic water cluster observed in the tetrahedral pores of MOF-801 and UiO-66 is an example of such an interplay of primary and secondary adsorption sites, as rationalised by the analytical model. Given the decisive role of water clusters in the adsorption behaviour of nanoporous materials, secondary adsorption sites can assist in shaping the water adsorption isotherms by improving the adsorption capacity of the material while maintaining modest desorption energies, as required for instance in atmospheric water harvesting.

Methods

Force fields

For each MOF considered in this work, a flexible force field was derived from first-principles data using the QuickFF protocol45. By relying on the equilibrium structure and the Hessian of isolated clusters distilled from the framework, the potential energy surface of the framework can be cast into an analytical representation. The first-principles calculations of the clusters were performed with Gaussian 1646, using a B3LYP level of theory47, a LanL2DZ basis set and effective core potential for the zirconium atoms48, and a 6-311g(d,p) basis set49 for the hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen atoms. The framework charges were obtained from MBIS partitioning50 of the electron density calculated with GPAW51, whereas the van der Waals interactions were described with Dreiding Lennard-Jones parameters52. For the water molecules, the q-TIP4P/f force field was used to avoid a double counting of the nuclear quantum effects (NQEs) when using path integral molecular dynamics (PIMD)53. More details regarding the energy expression of the force fields are provided in Supplementary Note 2.1.

For MOF-801, the force field simulations were also compared with PIMD simulations performed with a machine learning potential (MLP), to assess the robustness of the results. In the MLP, the atomic interactions are represented by a neural network with a MACE54 architecture that is trained on PBE-D3(BJ)55,56 energies and forces of configurations generated with the Psiflow57 methodology, as detailed in Supplementary Note 2.2. Both descriptions of water in MOF-801 are observed to yield similar results, as demonstrated in Supplementary Note 8.

PIMD simulations

To generate initial configurations with different water loadings for each MOF, grand canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulations at 300 K and 1 bar were performed with RASPA58, using equal translation, rotation, and insertion probabilities. Subsequently, the GCMC snapshots were used as initial configurations for path integral molecular dynamics (PIMD) simulations performed with i-PI59. PIMD was used instead of regular MD as nuclear quantum effects (NQEs) can play an important role in the description of water40. A brief outline of PIMD is provided in Supplementary Note 3. The temperature of the PIMD simulations was set to 300 K and controlled by a Langevin thermostat60 with a time constant of 100 fs. The pressure was set to 1 bar and controlled by a Raiteri-Gale-Bussi barostat61 with a time constant of 1 ps. For every atom, 32 beads were used to evaluate the short-range interactions, whereas the long-range interactions were evaluated on a contracted ring-polymer of 8 beads. The force evaluation in i-PI was delegated to Yaff62 in combination with LAMMPS63 to speed up the calculation of the non-covalent interactions. Every simulation was run with a time step of 0.25 fs and had a total simulation time of 250 ps. The reference simulation for bulk water used a box with 216 water molecules with a density of 997 kg/m3. This simulation was run for 200 ps with a constant volume.

Analytical model

As a toy model, three artificial confining environments were considered (see Fig. 4). A first environment consists of a repulsive cubic box in which water molecules can move freely and are restrained by repulsive walls modelled by the following potential:

with \({{{\mathcal{H}}}}\) the Heaviside function, κ the strength of the repulsive walls, and \(2\left\Vert {{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{0}\right\Vert\) the length of a side of the repulsive cube. For all simulations, a κ value of 100 kJ/(mol Å2) was used. The second and third confining environments closely mimic the tetrahedral pores of UiO-66 by introducing local adsorption sites in the above-mentioned repulsive cubic box with the following analytical potential:

with K, w, and r0,i respectively the strength, width, and position of the adsorption sites. Both a tetrahedral and a cubic arrangement of the adsorption sites were considered, as illustrated in Fig. 4, with \({{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{0,i}=\left[\pm \left(\frac{L}{2}-\varepsilon \right),\pm \left(\frac{L}{2}-\varepsilon \right),\pm \left(\frac{L}{2}-\varepsilon \right)\right]\) and L the box edge length. The width w of the adsorption sites was set to 3 Å.

To construct water adsorption isotherms for the analytical models with adsorption sites, the transition matrix Monte Carlo methodology (TMMC) was used64. After an initial canonical Monte Carlo equilibration of 105 steps at 300 K, a classical MD simulation of 500 ps is performed with a virtual Widom insertion and deletion after every MD step. By performing these simulations for different water loadings, the water adsorption isotherm can be determined. A more elaborate discussion of the water adsorption isotherms for the analytical models, using both the q-TIP4P/f force field and the MB-pol water model65, can be found in Supplementary Note 10.

Data availability

The structure and force field input files are available from the online GitHub repository at https://github.com/AranLamaire/Supporting_Information. Any additional data is available from the authors upon request.

Code availability

YAFF (https://github.com/molmod/yaff), i-PI (https://github.com/i-pi/i-pi), Psiflow (https://github.com/molmod/psiflow), MACE (https://github.com/acesuit/mace), and CP2K (https://github.com/cp2k/cp2k) are open source codes which are freely available at the provided links.

References

Pettersson, L. G. M., Henchman, R. H. & Nilsson, A. Water—the most anomalous liquid. Chem. Rev. 116, 7459–7462 (2016).

Breynaert, E. et al. Water as a tuneable solvent: a perspective. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 2557–2569 (2020).

Seki, T. et al. The bending mode of water: a powerful probe for hydrogen bond structure of aqueous systems. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 8459–8469 (2020).

Cui, B. et al. Low-dimensional and confined ice. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 53, 371–397 (2023).

Gupta, A. et al. Hydrogen clathrates: next generation hydrogen storage materials. Energy Storage Mater. 41, 69–107 (2021).

Wang, P. et al. Review on the synergistic effect between metal-organic frameworks and gas hydrates for CH4 storage and CO2 separation applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 167, 112807 (2022).

Fumagalli, L. et al. Anomalously low dielectric constant of confined water. Science 360, 1339–1342 (2018).

Hanikel, N., Prévot, M. S. & Yaghi, O. M. MOF water harvesters. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 348–355 (2020).

Yilmaz, G. et al. Autonomous atmospheric water seeping MOF matrix. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc8605 (2020).

Almassad, H. A., Abaza, R. I., Siwwan, L., Al-Maythalony, B. & Cordova, K. E. Environmentally adaptive MOF-based device enables continuous self-optimizing atmospheric water harvesting. Nat. Commun. 13, 4873 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. High-rate nanofluidic energy absorption in porous zeolitic frameworks. Nat. Mater. 20, 1015–1023 (2021).

Hummer, G., Rasaiah, J. C. & Noworyta, J. P. Water conduction through the hydrophobic channel of a carbon nanotube. Nature 414, 188–190 (2001).

Wang, D., Tian, Y. & Jiang, L. Abnormal properties of low-dimensional confined water. Small 17, 2100788 (2021).

Kolesnikov, A. I. et al. Anomalously soft dynamics of water in a nanotube: a revelation of nanoscale confinement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 035503 (2004).

Koga, K., Gao, G. T., Tanaka, H. & Zeng, X. C. Formation of ordered ice nanotubes inside carbon nanotubes. Nature 412, 802–805 (2001).

Takaiwa, D., Hatano, I., Koga, K. & Tanaka, H. Phase diagram of water in carbon nanotubes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 105, 39–43 (2008).

Algara-Siller, G. et al. Square ice in graphene nanocapillaries. Nature 519, 443–445 (2015).

Kapil, V. et al. The first-principles phase diagram of monolayer nanoconfined water. Nature 609, 512–516 (2022).

Freund, R. et al. 25 years of reticular chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 23946–23974 (2021).

Mouchaham, G. et al. Metal-organic frameworks and water: ‘from old enemies to friends’. Trends Chem. 2, 990–1003 (2020).

Zhang, B., Zhu, Z., Wang, X., Liu, X. & Kapteijn, F. Water adsorption in MOFs: structures and applications. Adv. Func. Mater. 34, 2304788 (2024).

Coudert, F.-X. Water adsorption in soft and heterogeneous nanopores. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1342–1350 (2020).

Rieth, A. J., Hunter, K. M., Dincă, M. & Paesani, F. Hydrogen bonding structure of confined water templated by a metal-organic framework with open metal sites. Nat. Commun. 10, 4771 (2019).

Drout, R. J., Robison, L., Chen, Z., Islamoglu, T. & Farha, O. K. Zirconium metal-organic frameworks for organic pollutant adsorption. Trends Chem. 1, 304–317 (2019).

Rojas, S. & Horcajada, P. Metal-organic frameworks for the removal of emerging organic contaminants in water. Chem. Rev. 120, 8378–8415 (2020).

Jun, B.-M. et al. Applications of metal-organic framework based membranes in water purification: a review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 247, 116947 (2020).

Canivet, J., Fateeva, A., Guo, Y., Coasne, B. & Farrusseng, D. Water adsorption in MOFs: fundamentals and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 5594–5617 (2014).

Wang, S. et al. A robust large-pore zirconium carboxylate metal–organic framework for energy-efficient water-sorption-driven refrigeration. Nat. Energy 3, 985–993 (2018).

Lenzen, D. et al. A metal–organic framework for efficient water-based ultra-low-temperature-driven cooling. Nat. Commun. 10, 3025 (2019).

Liu, X., Wang, X. & Kapteijn, F. Water and metal-organic frameworks: from interaction toward utilization. Chem. Rev. 120, 8303–8377 (2020).

van der Veen, M. A. et al. Confined water cluster formation in water harvesting by metal-organic frameworks: CAU-10-H versus CAU-10-CH3. Adv. Mater. 36, 2210050 (2024).

Hanikel, N. et al. Evolution of water structures in metal-organic frameworks for improved atmospheric water harvesting. Science 374, 454–459 (2021).

Furukawa, H. et al. Water adsorption in porous metal-organic frameworks and related materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 4369–4381 (2014).

Fuchs, A. et al. Water harvesting at the single-crystal level. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 14324–14334 (2023).

Yanagita, K. et al. Kinetics of water vapor adsorption and desorption in MIL-101 metal-organic frameworks. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 387–398 (2019).

Tan, K. T., Tao, S., Huang, N. & Jiang, D. Water cluster in hydrophobic crystalline porous covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 12, 6747 (2021).

Zheng, Z., Hanikel, N., Lyu, H. & Yaghi, O. M. Broadly tunable atmospheric water harvesting in multivariate metal-organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 22669–22675 (2022).

Lu, F.-F., Gu, X.-W., Wu, E., Li, B. & Qian, G. Systematic evaluation of water adsorption in isoreticular UiO-type metal-organic frameworks. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 1246–1255 (2023).

Zhang, J., Paesani, F. & Lessio, M. Computational insights into the interaction of water with the UiO-66 metal-organic framework and its functionalized derivatives. J. Mater. Chem. C 11, 10247–10258 (2023).

Ceriotti, M. et al. Nuclear quantum effects in water and aqueous systems: experiment, theory, and current challenges. Chem. Rev. 116, 7529–7550 (2016).

Kalmutzki, M. J., Diercks, C. S. & Yaghi, O. M. Metal-organic frameworks for water harvesting from air. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704304 (2018).

Paesani, F. Water in metal-organic frameworks: structure and diffusion of H2O in MIL-53(Cr) from quantum simulations. Mol. Simul. 38, 631–641 (2012).

Lamaire, A., Wieme, J., Hoffman, A. E. J. & Van Speybroeck, V. Atomistic insight in the flexibility and heat transport properties of the stimuli-responsive metal-organic framework MIL-53(Al) for water-adsorption applications using molecular simulations. Faraday Discuss. 225, 301–323 (2021).

Ichii, T. et al. Observation of an exotic state of water in the hydrophilic nanospace of porous coordination polymers. Commun. Chem. 3, 16 (2020).

Vanduyfhuys, L. et al. Extension of the QuickFF force field protocol for an improved accuracy of structural, vibrational, mechanical and thermal properties of metal-organic frameworks. J. Comput. Chem. 39, 999–1011 (2018).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16 Revision C.01. (Gaussian Inc. Wallingford CT, 2016).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 38, 3098–3100 (1988).

Hay, P. J. & Wadt, W. R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for the transition metal atoms Sc to Hg. J. Chem. Phys. 82, 270–283 (1985).

Krishnan, R., Binkley, J. S., Seeger, R. & Pople, J. A. Self–consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 72, 650–654 (1980).

Verstraelen, T. et al. Minimal basis iterative stockholder: atoms in molecules for force-field development. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 3894–3912 (2016).

Enkovaara, J. et al. Electronic structure calculations with GPAW: a real-space implementation of the projector augmented-wave method. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 22, 253202 (2010).

Mayo, S. L., Olafson, B. D. & Goddard, W. A. DREIDING: a generic force field for molecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. 94, 8897–8909 (1990).

Habershon, S., Markland, T. E. & Manolopoulos, D. E. Competing quantum effects in the dynamics of a flexible water model. J. Chem. Phys. 131, 024501 (2009).

Batatia, I., Kovacs, D. P., Simm, G., Ortner, C. & Csanyi, G. MACE: Higher order equivariant message passing neural networks for fast and accurate force fields. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 pp 11423–11436 (NeurIPS 2022).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Vandenhaute, S., Cools-Ceuppens, M., DeKeyser, S., Verstraelen, T. & Van Speybroeck, V. Machine learning potentials for metal-organic frameworks using an incremental learning approach. NPJ Comput. Mater. 9, 19 (2023).

Dubbeldam, D., Calero, S., Ellis, D. E. & Snurr, R. Q. RASPA: molecular simulation software for adsorption and diffusion in flexible nanoporous materials. Mol. Simula. 42, 81–101 (2016).

Kapil, V. et al. i-PI 2.0: A universal force engine for advanced molecular simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 236, 214–223 (2018).

Ceriotti, M., Parrinello, M., Markland, T. E. & Manolopoulos, D. E. Efficient stochastic thermostatting of path integral molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 133, 124104 (2010).

Raiteri, P., Gale, J. D. & Bussi, G. Reactive force field simulation of proton diffusion in BaZrO3 using an empirical valence bond approach. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 23, 334213 (2011).

Verstraelen, T., Vanduyfhuys, L. & Vandenbrande, S. Yaff, yet another force field. https://github.com/molmod/yaff.

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Witman, M., Mahynski, N. A. & Smit, B. Flat-histogram monte carlo as an efficient tool to evaluate adsorption processes involving rigid and deformable molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 14, 6149–6158 (2018).

Riera, M. et al. MBX: a many-body energy and force calculator for data-driven many-body simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 054802 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO, grant nos. 11D2220N (A.L.), 12T3522N (S.M.J.R.), and 11H6821N (S.V.)), Flanders Industry Innovation Moonshot (ARCLATH II, No. HBC.2021.0254 and MOONRISE, No. HBC.2020.2612), and the Research Board of Ghent University (BOF). The main computational resources (Stevin Supercomputer Infrastructure) and services used in this work were provided by the VSC (Flemish Supercomputer Center), funded by Ghent University, FWO, and the Flemish Government—department EWI. A part of the simulations was performed on the Luxembourg national supercomputer MeluXina. The authors gratefully acknowledge the Lux-Provide teams for their expert support. We also acknowledge the EuroHPC Joint Undertaking for awarding this project access to the EuroHPC supercomputer LUMI, hosted by CSC (Finland) and the LUMI consortium through a EuroHPC Regular Access call. Finally, we would also like to thank Venkat Kapil and Ben Clifford for their help with Psiflow implementations regarding i-PI and Parsl, respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.L., S.M.J.R., J.W., and V.V.S. designed the research. A.L. performed all the simulations and analysed the results, which were discussed among all authors. Under the supervision of V.V.S., the methodology was developed by A.L., J.W., S.M.J.R, S.V., and R.G. J.W. derived the MOF force fields. S.V. trained the MLP of MOF-801. R.G. provided the required expertise to calculate the water adsorption isotherms using TMMC simulations. A.L. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lamaire, A., Wieme, J., Vandenhaute, S. et al. Water motifs in zirconium metal-organic frameworks induced by nanoconfinement and hydrophilic adsorption sites. Nat Commun 15, 9997 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54358-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54358-z