Abstract

Molecular detection is important in biosensing, food safety, and environmental surveillance. The high biocompatibility, superior mechanical stability, and low cost make plasmon-free surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) a promising sensing technique, the ultrahigh sensitivity of which is urgently pursued for realistic applications. As a proof of concept, we report a mechanochemical strategy, which combines the wrinkling and chemical functionalization, to fabricate a plasmon-free SERS platform based on 2D MnPS3 with a sub-attomolar detection limit. In detail, the formation of wrinkles in 2D MnPS3 enables a SERS substrate of the material to detect trace methylene blue molecules. The mechanism is experimentally revealed that the wrinkled structures contribute to the improvement of light-matter coupling. On this basis, decorating a wrinkled MnPS3 which has absorbed methylene blue with histamine dihydrochloride further lowers the detection limit to 10−19 M. Because the amino groups in histamine dihydrochloride molecules are crosslinkers that create more pathways to promote charge transfer between these substances. This work provides a guidance for the design of SERS sensors with single-molecule-level sensitivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Small-molecule sensing is vital for biological, diagnostic, and therapeutical applications1,2, the global market of which is valued at billions of US dollars or more in 2024. The tactics that include field effect3, electrochemistry4, circular dichroism1, and fluorescence5,6 have been developed to achieve the trace detection of small molecules. Based on quantum sensing technology, the detection sensitivity can be increased to the molecular level7,8. Besides, surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) is a versatile and high-speed detection technique with molecule-level detection limit for medical diagnosis, biological monitoring, and residues detection9,10,11,12. In comparison to SERS sensors based on noble metal plasmonics, plasmon-free ones have drawn dramatic attention due to their superior biocompatibility, high stability, and low cost in the above applications13. Taking advantage of edges, defects, and boundaries to absorb molecules, two-dimensional (2D) materials present an opportunity in plasmon-free SERS for ultrasensitive sensing. Their operation relies on a chemical enhancement (CE) mechanism, which is the result of charge transfer between 2D materials and analytes14. The promotion of charge transfer intensively depends on changing the bandgap of 2D materials by controlling their chemical composition or using heterostructures15. 2D MnPS3, a typical member of thiophosphites with a wide bandgap of 3.1 eV and antiferromagnetism16, is found to have plasmonic edges17. Because of the edge plasmons, SERS is observed in it to indicate its great potential as a fundamental material for molecular sensing18,19. However, engineering the energy band structure of 2D MnPS3 by composition control make related SERS substrates just capable of detecting 10−9 M molecules, which is inadequate for biomarker detection in medical diagnostics9 and recognition of contaminants in food20. Therefore, methods to activate 2D MnPS3 for SERS with molecular sensitivity are urgently needed.

In the light of the SERS mechanism, charge transfer and light-matter interaction are dominant factors to be considered when designing a plasmon-free SERS platform based on 2D MnPS3. Chemical functionalization with organic molecules is widely used to finely modify the electronic structures of 2D materials including graphene21, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs)22, antimonene23, etc. It is found that charge transfer effects between 2D materials and molecular fragments play an important role in these processes in a covalent or noncovalent way24. In other words, chemical decoration can increase charge transfer. Wrinkled structures with strain gradients in 2D TMDCs are also important in improving its interaction with light25, which has been verified using a photoinduced force microscope26. A similar increase in light-matter coupling is also observed in wrinkled 2D CuInP2S6, which is another typical thiophosphite27. As a result, the combination of chemical decoration and strain engineering will become a new way to functionalize 2D materials. Preliminary attempts have been made to clarify the mechanism by which graphene wrinkles impact the resonance states of absorbed molecules28 and create binding energy gradient to induce the migration of molecules in the chemical-mechanical coupling regime29. However, this approach is still missing the sensitivity of SERS based on 2D materials.

Herein, we report a mechanochemical approach for the design and manufacture of flexible plasmon-free SERS platform based on 2D MnPS3, which is capable of single-molecule-level detection. Abundant vacancies in the 2D MnPS3 that act as sites to capture analytes and generate charge transfer is the prerequisite for SERS detection. Furthermore, the fabrication of wrinkles in 2D MnPS3 significantly increases the performance of its SERS substrate, which can detect trace methylene blue (MB) analytes. In-situ SERS results of 2D MnPS3 under strains not only experimentally confirm the light-matter interaction mechanism on SERS promotion, but also claim its high operating stability under mechanical deformation. Additional chemical functionalization with histamine dihydrochloride (HD) molecules reduces the detection limit to 10−19 M, i.e., one molecule in hundreds of microliters of solutions, at the wrinkled locations of the SERS substrate. The mechanism for this is that HD molecules serve as crosslinkers to form a noncovalent interaction with MnPS3 and promote charge transfer for the CE of SERS. This work provides new insights into the design and manufacture of a plasmon-free SERS platform with single-molecule detection ability, as well as a way to control the properties and broaden the applications of 2D materials.

Results

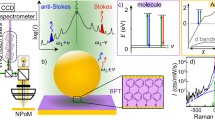

Mechanochemical strategy for designing SERS platform

Figure 1a shows the common structure of the plasmon-free SERS substrates based on 2D materials. Quasi-covalent bonding and charge transfer between the analytes and the 2D material makes the SERS substrate function. Compared to the plasmonic SERS substrates, their detection limit needs to be improved. To do this, we propose a mechanochemical strategy to design the SERS platform. First, wrinkles are fabricated in 2D materials (Fig. 1b) to improve the interaction between the SERS substrate and the incident laser, and -NH2 groups are then introduced to chemically functionalize the SERS substrate (Fig. 1c), which improves the charge transfer. Using this method, 2D MnPS3 with edge plasmons and a large number of active sites is taken as an example. Figure 1d and e show a ball-and-stick model of 2D MnPS3, which has a monoclinic crystal structure and is composed of alternative [P2S6]4− and [Mn]2+ layers with an interlayer spacing of 0.65 nm. MnPS3 flakes with different thicknesses are easily obtained by mechanical exfoliation (Supplementary Fig. 1) and their high quality is shown by Raman spectrum, X-ray diffraction (XRD), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analyzes (Supplementary Fig. 2). During the preparation and transfer processes, wrinkles are randomly formed in 2D MnPS3, as shown in Fig. 1f. At flat region, we observe two main characteristic modes at 1398 and 1625 cm−1 of MB molecules with the concentration of 10−6 M (Fig. 1g), the intensities of which are quadrupled at wrinkled area (Fig. 1h). After the chemical functionalization with HD molecules, which dramatically improves the ability of 2D MnPS3 to detect MB (Fig. 1i) with the same concentration. In summary, these two modifications to a plasmon-free SERS detection platform based on 2D MnPS3 produce much more sensitive detection.

Schematic demonstration of the evolution process from (a) traditional plasmon-free SERS substrate to mechanochemical SERS platform based on the combination of (b) wrinkling and (c) chemical functionalization. d Top and (e) side view of ball-and-stick model of 2D MnPS3. f SEM image of 2D MnPS3 with a wrinkle. Raman spectra of MB molecules with the concentration of 10−6 M collected at (g) flat area, wrinkled area (h) before and (i) after chemical functionalization.

Abundant active sites on the surface of 2D materials are the prerequisite for their use in plasmon-free SERS. To study the surface structure, we used atomic force microscopy (AFM) to confirm the selection of a MnPS3 bilayer with a thickness of approximately 1.4 nm, as exhibited in Fig. 2a. Lateral force microscope (LFM) was used to image the lattice structure of 2D MnPS3 in the [001] direction (Fig. 2b). The corresponding fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern in the inset of Fig. 2c shows (1\(\bar{1}\)0), (\(\bar{1}\bar{1}\)0), and (0\(\bar{2}\)0) spots in reciprocal space, indicating that the flake was a single crystal. We also performed high-angle annular dark-field scanning TEM (HAADF-STEM) to analyze the flake and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) maps of Mn, P, and S elements indicates the uniformity of the flake (Supplementary Fig. 3). An atomic-resolved HAADF-STEM image (Fig. 2d) shows that there are 20 vacancies, marked by yellow dotted circles, in a 7 × 7 nm area on the surface of the flake. The lack of atoms is determined by the low intensity at these locations (Fig. 2e). The density of vacancies is estimated to be more than 3 × 1013 cm−2, which is higher than that on the surface of 2D TMDCs synthesized by chemical vapor deposition30. Therefore, a large number of vacancies on the surface causes the MnPS3 to absorb molecules and activates its SERS activity. As seen in Fig. 2f, MB molecules have two absorption peaks (indicated by grey dotted lines) in the wavelength range of 600–700 nm, while the absorption of visible light by MnPS3 shows no obvious peak. It is worth noting that an additional absorption band (indicated by a red dotted line) occurs for the mixture of MnPS3 and MB dyes, and is caused by noncovalent interaction and charge transfer between the two substances15. Accordingly, it is foreseeable that Raman spectra of MB molecules with the concentration of 10−6 M can be collected on 2D MnPS3, clarifying its plasmon-free SERS effect (Supplementary Fig. 4a and b). Based on the intensities of two main characteristic modes at 1398 and 1625 cm−1, the number of 2D MnPS3 layers has a slight effect on the strength of SERS signals. In addition, Raman bands of MB molecules on 2D MnPS3 can be activated by an incident laser with a wavelength of 633 nm rather than 532 nm (Supplementary Fig. 4c), which is consistent with the emergence of the resonance peak in the range of 600–700 nm (Fig. 2f). To summarize, 2D MnPS3 is promising for use in plasmon-free SERS platform because the active vacancies on its surface to bond analytes and initiate charge transfer for CE.

a AFM image of a 2D MnPS3 flake. Inset is a plot of the flake height along the yellow dotted line. b LFM image and (c) corresponding FFT pattern of 2D MnPS3. d Atomic-resolved HAADF-STEM image of 2D MnPS3. Surface vacancies are marked by yellow dotted circles. e (top) HAADF-STEM image of 2D MnPS3 and (bottom) the intensity variation along the green dotted line which indicates a vacancy. f Transmittance spectra of MnPS3, MB molecules, and their mixture.

SERS performance and sub-attomolar molecular sensing

In addition to the resonance between 2D materials and molecules, improving the light-matter interaction must also be considered to enhance the performance of SERS substrates. It has been reported that formation of wrinkles in 2D materials can promote the light-matter coupling due to the introduction of suspension and strain26. Figure 3a illustrates the controllable formation of uniaxial wrinkles in a 2D sheet using the pre-strain method31. Mechanically-exfoliated MnPS3 flakes were attached to an adhesive tape which is pasted, flake side down, to a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrate under a uniaxial tensile stress. After removing the tape, some of flakes remained on the pre-strained PDMS. Finally, the PDMS substrate was released to its original state and MnPS3 with parallel ridges (Supplementary Fig. 5) was obtained. Scanning electronic microscopy (SEM) in Fig. 3b shows a gap between the wrinkles and the substrate, indicating the suspension of wrinkles. The strain of a wrinkle varies with position and is schematically shown in Fig. 3c. The strain at the peak of a wrinkle (ε) can be easily changed by changing the pre-strain of the PDMS layer during the preparation process. Specifically, the wavelength (λ) of uniaxial wrinkles, which is also known as the distance between adjacent wrinkles, can be calculated by32

where t, E, and ν represent the thickness, Young’s modulus, and Poisson’s ratio of MnPS3 flake, respectively, μs is the shear modulus of PDMS, Λ is a constant equaled to

where ε0 donates to the pre-tension of PDMS. Regarding the flakes with the same t, E and ν are also constants. According to these two equations, smaller λ is achieved on PDMS substrate with a higher pre-strain, leading to a higher aspect ratio (height to width, h/λ) of the wrinkles33. ε is calculated by34

a Schematic of the fabrication of parallel wrinkles in 2D MnPS3. b SEM image of the wrinkles. c Schematic of the strain variation in a wrinkle. d Raman spectra of MB molecules absorbed from solutions with the same concentration at wrinkled MnPS3 regions prepared on PDMS substrates with different pre-strains and flat regions. e Optical microscope image of parallel wrinkles, one of which has collapsed to a fold. f Raman map based on the intensity of the peak at 1625 cm−1, which is corresponding to (e). g SERS spectra of MB molecules on MnPS3 wrinkles subjected to different tensile strains.

Theoretically, the height, width, and distance between wrinkles are determined by ε0 and have an influence on both ε and light-matter coupling. Therefore, the release of PDMS substrate with a higher pre-strain results in the formation of uniaxial MnPS3 wrinkles with a higher strain, which shows stronger light-matter interaction and higher SERS performance.

As shown in Fig. 3d, we find that the intensities of the vibration modes of MB molecules at 1398 and 1625 cm−1 on a wrinkled MnPS3 flake are much higher than on a flat one, with the strongest signals coming from a wrinkled flake prepared on the PDMS substrate with a 20% pre-tension. To highlight the contribution of wrinkles to the SERS, a square area including in which some wrinkles had collapsed to folds was selected for Raman mapping (Fig. 3e). The corresponding Raman map based on the intensity of 1625 cm−1 mode (Fig. 3f) shows more sensitive detection of MB molecules at wrinkles, while only small signals appear at the folds. Raman maps of MB molecules at the same scale show the strongest responses on wrinkled MnPS3 prepared using PDMS with a 20% tensile strain because of the high curvature (Supplementary Fig. 6). Owing to the improved light-matter coupling, the plasmon-free SERS substrates based on 2D MnPS3 with wrinkles are able to detect 10−10 M MB molecules (Supplementary Fig. 7). In addition, Raman characterization of a wrinkled MnPS3-based SERS substrate under tension was performed. The intensities of the two MB characteristic peaks decrease with the increasing strain, and return to its initial value when the tension is fully released (Fig. 3g). The ability to detect trace MB molecules using a SERS substrate under 10% tensile strain proves the ultrahigh flexibility and stability of the substrate, which is of great importance for detection in harsh conditions. These experimental results support the above theoretical insights and align with the phenomena reported by the previous study26. In this part, we optimize the detection performance of plasmon-free SERS substrate through the strain engineering of 2D materials, and experimentally verify the functions of light-matter coupling on SERS activation.

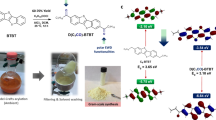

Chemical functionalization can increase the charge-transfer behaviors of 2D materials21, which results in better SERS performance. With the introduction of HD molecular fragments, SERS substrates based on functionalized wrinkled MnPS3 can detect MB molecules at ultralow concentrations from 10−11 to 10−19 M (Figs. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 8), which is equivalent to a single MB molecule in hundreds of microliters of solution. Regrading to the SERS spectrum of MB molecules at 10−19 M concentration, the calculated signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) of the signals at 1398 (Supplementary Fig. 9a) and 1625 cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. 9b) are 3.3 and 3.1, respectively. Hence, these SERS peaks are further confirmed, since their SNRs are more than 335. Noteworthily, the SERS substrate used to detect 10−11 M MB molecules (Supplementary Fig. 10a) show good reproducibility with 23% standard deviation of the peak intensity at 1625 cm−1, owing to the uniform absorption of probe molecules. In comparison, the small amount of MB molecules in 10−19 M solution is insufficient to fully cover the SERS substrate. Therefore, the distribution of insufficient probe molecules gives rise to the variable peak intensities at different locations. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 10b, it is a probability to collect obvious characteristic peaks or observe no Raman signals at different wrinkled areas on the same SERS substrate, but blinking phenomena were not observed in this case. In addition, the SERS substrate shows a high enhancement factor of 4.8 × 108 (Supplementary Fig. 11). These outstanding detection performances are caused by the combined effects of wrinkle-induced light-matter interaction and chemical modulation, since the intensities of MB vibrational modes at wrinkles is higher than that at flat areas after chemical decoration (Supplementary Fig. 12a). To assess the stability of a 2D MnPS3-based SERS substrate that is exposed in continuous laser radiation, and Raman spectra were collected for every 10 min. As shown in Fig. 4b, the peak intensity of MB decreases with the radiation time, but still maintains about 32% of its original after 2 h. In addition, when the SERS sensor was stored in ambient conditions for 50 days, the peak intensity was at least 75% as high as its original value (Fig. 4c). These results show the sub-attomolar detection limit and high stability of the plasmon-free SERS platform based on wrinkled MnPS3 with chemical functionalization.

a SERS spectra of MB molecules absorbed from bulk solutions with various concentrations. Stability of SERS spectra of MB molecules after (b) the exposure to laser radiation for more than 2 h and (c) 50-day storage in air. d S 2p XPS spectra of MnPS3 with (top) and without (bottom) MB and HD molecules. e AFM image of a wrinkle in 2D MnPS3 with MB and HD molecules, three locations of which were selected to collect (f) nano-IR spectra. g Schematic of the operating mechanism for mechanochemical SERS platform. h Performance comparison among plasmon-free SERS substrates based on MnPS3, other 2D materials or heterostructures, plasmonic SERS substrates, and other small-molecule sensors.

Mechanism of mechanochemical activation for SERS improvement

It is interesting to understand the mechanism of the mechanochemical approach to significantly improving the SERS effect based on 2D materials. Note that every HD molecule has one -NH2 group, which may contribute to the interaction with 2D MnPS3 and MB probe molecules. To test this, 2D MnPS3-based SERS substrates were functionalized with HD molecules at different concentrations, and this is positively corelated with the peak intensity of MB (Supplementary Fig. 12b). Accordingly, this mechanochemical SERS technology may provide a converse way to determine the abundance of HD based on the spectral processing of MB molecules on these functionalized SERS platforms with different concentrations of HD molecules, since the ultrafast and sensitive detection of histamine is extremely urgent in the fields of food safety and biology36. Tyramine hydrochloride (TH), which also has an amino group, was used to replace HD for the chemical decoration of a 2D MnPS3-based SERS substrate. As expected, strong Raman signatures of MB molecules at a low concentration of 10−11 M were collected, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 12c. These results reflect the participation of amino groups in the activation of SERS performance. In addition to the intensity, we found that there is at least 5 cm−1 shift of 1625 cm−1 peak of MB molecules at both the wrinkled and flat regions of 2D MnPS3 (Supplementary Fig. 13). According to Stark and charge transfer theories37, the absorbed HD molecules can change the polarizability and charge transfer state of MB, leading to the peak shift. Based on XPS analyzes of 2D MnPS3, S 2p orbits have a binding energy shift of 0.56 eV after the absorption of MB molecules and functionalization with amino groups (Fig. 4d). The red shift is related to electron acceptance of S sites from the absorbed MB and HD molecules38. We also used nano-IR to examine the combined effects of the wrinkled morphology and molecule decoration. As shown in Fig. 4e and f, the peak around 3000 cm−1 has a red shift at the top of the wrinkle, compared with that at unstrained part. This peak belongs to HD molecules, because it is absent in bare MnPS3 and MnPS3 with absorbed MB molecules (Supplementary Fig. 14). Accordingly, charges in HD fragments incline to transfer through wrinkles rather than flat regions of 2D MnPS3. Apart from the enhanced light-matter interaction, wrinkles also play a role in improving chemical functionalization. Furthermore, Supplementary Fig. 15 shows a photoluminescence (PL) peak at near 800 nm for the mixture of MB and HD molecules. The peak intensity can be further enhanced and the peak position can be redshifted by adding 2D MnPS3 flakes as substrates to the system, indicating the charge transfer between MB, HD molecules, and 2D MnPS3. Additionally, we have fabricated a device based on 2D MnPS3 (Supplementary Fig. 16a). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 16b and c, the electrical conductivity of 2D MnPS3 rarely changes after the absorption of MB and HD molecules, demonstrating the predominant contribution of -NH2 groups to the charge transfer between 2D MnPS3 and MB molecules rather than that on 2D MnPS3.

Consequently, it is clear that the mechanism of chemical decoration on SERS is that HD molecules act as crosslinkers to functionalize 2D MnPS3 and interact with MB analytes, supplying more channels for charge transfer (Fig. 4g). Using the mechanochemical method, the SERS-active platform based on 2D MnPS3 harvests a sub-attomolar detection sensitivity. As shown in Fig. 4h, the performance is superior to those of other plasmon-free SERS substrates constructed by controlling the chemical composition of the 2D materials or using heterostructures19,39,40,41. The detection limit of 2D MnPS3-based SERS substrate is also lower than those of the newly-developed SERS sensors based on 2D TMDCs/metal hybrids (10−18 M)11,42 and metallic nanocolloids (10−16 M)9. It is worth mentioning that the performance of this mechanochemical SERS platform surpass the small-molecule detectors fabricated based on the concepts of quantum capacitance8, field effect3, electrochemistry4, circular dichroism1, and fluorescence5,6.

Discussion

We have designed and manufactured a plasmon-free SERS platform based on 2D MnPS3 with sub-attomolar detection capability by using mechanochemical strategy. We took the role of light into account to optimize the performance of the SERS substrate, in which the mechanism of light-matter interaction induced by wrinkled structures has been demonstrated. We also found that chemical functionalization with HD molecules further activates the 2D MnPS3-based SERS so that it can detect MB molecules at an extremely low concentration of 10−19 M, which equals to a single molecule in dozens of microliters in aqueous. The mechanism for this has been shown to be due to the aminos in HD molecules supplying many more pathways to increase charge transfer. Out results provide a novel way to overcome the performance limit of the plasmon-free SERS detection platform, but also spread a solution to fine control of the properties of 2D materials for fundamental physics and state-of-art technologies.

Method

Characterization of 2D MnPS3

Optical microscope (LV150N, Nikon) and SEM (S-4800, Hitachi) images were captured to characterize the morphology of mechanically-exfoliated and wrinkled MnPS3 flakes. AFM (Cypher ES, Oxford Instruments) at contact mode was used to image the morphology of 2D MnPS3. An approximately 20 × 20 nm region of a MnPS3 flake was scanned by using the LFM mode with a high frequency of 20 Hz to image lattice structures in [001] direction and acquire corresponding FFT patterns. XRD (K-Alpha, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and XPS (SmartLab, Rigaku) were used to analyze the structure and chemical composition of 2D MnPS3. Transmittance spectra were collected using an UV-vis spectrophotometer (UV-2700, SHIMADZU). With a cold-field-emission spherical aberration corrected TEM (Spectra 300, FEI) operated at 300 kV, HAADF-STEM images were taken to study the crystal structures and locate vacancies on the surface of 2D MnPS3, and EDS measurements were made to analyze the chemical composition of 2D MnPS3. Nano-IR spectra (NanoIR3, Bruker) were plotted to study IR absorption of chemically-functionalized 2D MnPS3. I-V curves of device based on 2D MnPS3 were measured by a semiconductor parameter analyzer (B1500A, Agilent).

SERS based on 2D MnPS3

SERS substrates were firstly immersed in 20 mL MB (98.5%, Yatai Chemical) and ethanol solutions with various concentrations to absorb analytes. After 6 h, the substrates were cleaned in pure ethanol and dried in air, in order to eliminate the residual solution and retain the molecules which are bonded to the SERS substrates. For further chemical decoration, the SERS substrates with absorbed molecules were placed in HD (98%, Macklin) or TH (98%, Macklin) and DI water solutions with a certain concentration for 6 h and then dried in air. Raman spectrometer (HR800, Horiba JY) was employed to collect SERS spectra of MB molecules on SERS substrates under a 633 nm excitation laser with a spot radius of 5 μm. No less than 5 spectra were collected at the locations with the similar morphology in the same SERS platform to obtain an averaged spectrum. Raman maps were obtained with step increments of 0.5 μm. SNR of Raman peaks was calculated by

where S is the peak height, σy represents the standard deviation of the peak height. PL spectra were collected using the same instrument with an excitation laser of 532 nm.

Calculation of EF

The EF of a SERS substrate is defined as39

where ISERS and IBulk are the intensities of dye molecules on SERS platform and bulk dye powders, respectively, and NSERS and NBulk represent the dye molecule numbers at the laser spot in these two cases. In this work, MB dye solutions with the high concentration of 10−3 M were dropped onto PDMS substrate to obtain bulk powders after the adequate evaporation of the ethanol solvent. Then 8 random locations were selected to collect the Raman spectra of bulk MB with the acquisition time of 2 s, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 11a. Accordingly, the average intensity of the characteristic peak at 1625 cm−1 was calculated as 386.4 counts, namely 193.2 counts s−1 (IBulk). NBulk can be expressed by

where ρ is the density of MB (1.23 g cm−1), h is the penetration depth of 633 nm laser (3 μm)43, NA is the Avogadro constant, A is the laser spot area (5 μm in radius), and Mmol is the molar mass of MB (337.87 g mol−1).

To estimate NSERS, we conducted an additional experiment that a SERS substrate was immerged into 1 mL MB solution with the concentration of 10−19 M, containing a total of approximately 60 MB molecules. We randomly selected 10 wrinkled locations to collect SERS spectra with the acquisition time of 30 s (Supplementary Fig. 11b), observing the characteristic peak at 1625 cm−1 in three of them, according to the criterion of SNR > 3 for peak determination. To avoid the overestimation of EF, we assume that all of 60 molecules in solution were absorbed on the SERS substrate, and they distributed at the three locations where the Raman signals of 1625 cm−1 peak were observed. Taking the bottom spectrum in Supplementary Fig. 11b, the signals in which stems from at most 20 molecules (NSERS), ISERS is calculated as 107.4 counts/30 s = 3.58 counts s−1. Based on the above discussion and calculation, EF is evaluated as 4.8 × 108.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file.

References

Liu, Y., Wu, Z., Armstrong, D. W., Wolosker, H. & Zheng, Y. Detection and analysis of chiral molecules as disease biomarkers. Nat. Rev. Chem. 7, 355–373 (2023).

Nguyen, P. Q. et al. Wearable materials with embedded synthetic biology sensors for biomolecule detection. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 1366–1374 (2021).

Nakatsuka, N. et al. Aptamer-field-effect transistors overcome Debye length limitations for small-molecule sensing. Science 362, 319–324 (2018).

Lee, D. H., Lee, W.-Y. & Kim, J. Introducing nanoscale electrochemistry in small-molecule detection for tackling existing limitations of affinity-based label-free biosensing Applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 17767–17778 (2023).

Cao, D. et al. Coumarin-based small-molecule fluorescent chemosensors. Chem. Rev. 119, 10403–10519 (2019).

Jiang, C. et al. NBD-based synthetic probes for sensing small molecules and proteins: design, sensing mechanisms and biological applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 7436–7495 (2021).

Liu, X. & Hersam, M. C. 2D materials for quantum information science. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 669–684 (2019).

Huang, Y. et al. Ultrasensitive quantum capacitance detector at the edge of graphene. Mater. Today 73, 38–46 (2024).

Bi, X., Czajkowsky, D. M., Shao, Z. & Ye, J. Digital colloid-enhanced Raman spectroscopy by single-molecule counting. Nature 628, 771–775 (2024).

Son, W. K. et al. In vivo surface-enhanced Raman scattering nanosensor for the real-time monitoring of multiple stress signalling molecules in plants. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 205–216 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. 1T′-transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers stabilized on 4H-Au nanowires for ultrasensitive SERS detection. Nat. Mater. 23, 1355–1362 (2024).

Chen, W. et al. Synergistic effects of wrinkled graphene and plasmonics in stretchable hybrid platform for surface‐enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Adv. Opt. Mater. 5, 1600715 (2017).

Itoh, T. et al. Toward a new era of SERS and TERS at the nanometer scale: from fundamentals to innovative applications. Chem. Rev. 123, 1552–1634 (2023).

Tao, L. et al. 1T′ transition metal telluride atomic layers for plasmon-free SERS at femtomolar levels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 8696–8704 (2018).

Cong, S., Liu, X., Jiang, Y., Zhang, W. & Zhao, Z. Surface enhanced Raman scattering revealed by interfacial charge-transfer transitions. Innovation 1, 100051 (2020).

Shan, J.-Y. et al. Giant modulation of optical nonlinearity by Floquet engineering. Nature 600, 235–239 (2021).

Roccapriore, K. M., Kalinin, S. V. & Ziatdinov, M. Physics discovery in nanoplasmonic systems via autonomous experiments in scanning transmission electron microscopy. Adv. Sci. 9, 2203422 (2022).

Barua, A. et al. Photoluminescence and Raman enhancement by edge plasmons in MnPS3. J. Phys. Chem. C. 128, 6401–6411 (2024).

Wang, R. et al. Entropy engineering on 2D metal phosphorus trichalcogenides for surface‐enhanced Raman scattering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2312322 (2023).

Ferris, M. & Zabow, G. Quantitative, high-sensitivity measurement of liquid analytes using a smartphone compass. Nat. Commun. 15, 2801 (2024).

Bottari, G. et al. Chemical functionalization and characterization of graphene-based materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 4464–4500 (2017).

Zhang, S. et al. Controllable, wide-ranging n-doping and p-doping of monolayer group 6 transition-metal disulfides and diselenides. Adv. Mater. 30, 1802991 (2018).

Abellan, G. et al. Noncovalent functionalization and charge transfer in antimonene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 14389–14394 (2017).

Han, J. et al. Recent progress in 2D inorganic/organic charge transfer heterojunction photodetectors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2205150 (2022).

Wang, S.-W. et al. Thermally strained band gap engineering of transition-metal dichalcogenide bilayers with enhanced light-matter interaction toward excellent photodetectors. ACS Nano 11, 8768–8776 (2017).

Cho, C. et al. Spatial tuning of light-matter interaction via strain-gradient-induced polarization in Freestanding Wrinkled 2D Materials. Nano Lett. 23, 9340–9346 (2023).

Rahman, S., Yildirim, T., Tebyetekerwa, M., Khan, A. R. & Lu, Y. Extraordinary nonlinear optical interaction from strained nanostructures in van der Waals CuInP2S6. ACS Nano 16, 13959–13968 (2022).

Nirmalraj, P. N., Thodkar, K., Guerin, S., Calame, M. & Thompson, D. Graphene wrinkle effects on molecular resonance states. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2, 8 (2018).

Banerjee, S., Hawthorne, N., Batteas, J. D. & Rappe, A. M. Two-legged molecular walker and curvature: mechanochemical ring migration on graphene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 26765–26773 (2023).

Wu, Q. et al. Resolidified chalcogen precursors for high‐quality 2D semiconductor growth. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, e202301501 (2023).

Chen, W., Gui, X., Yang, L., Zhu, H. & Tang, Z. Wrinkling of two-dimensional materials: methods, properties and applications. Nanoscale Horiz. 4, 291–320 (2019).

Zang, J. et al. Multifunctionality and control of the crumpling and unfolding of large-area graphene. Nat. Mater. 12, 321–325 (2013).

Cao, C., Chan, H. F., Zang, J., Leong, K. W. & Zhao, X. Harnessing localized ridges for high‐aspect‐ratio hierarchical patterns with dynamic tunability and multifunctionality. Adv. Mater. 26, 1763–1770 (2014).

Wang, J. et al. Locally strained 2D materials: preparation, properties, and applications. Adv. Mater. 36, 2314145 (2024).

McCreery R. L. Raman Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis. (John Wiley & Sons, 2000).

Yu, J. et al. Advances in technologies to detect histamine in food: principles, applications, and prospects. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 146, 104385 (2024).

Ma, H. et al. Frequency shifts in surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy-based immunoassays: mechanistic insights and application in protein carbonylation detection. Anal. Chem. 91, 9376–9381 (2019).

Garrido, M., Naranjo, A. & Pérez, E. M. Characterization of emerging 2D materials after chemical functionalization. Chem. Sci. 15, 3428–3445 (2024).

Lv, Q. et al. Ultrafast charge transfer in mixed-dimensional WO3-x nanowire/WSe2 heterostructures for attomolar-level molecular sensing. Nat. Commun. 14, 2717 (2023).

Seo, J. et al. Ultrasensitive plasmon-free surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy with femtomolar detection limit from 2D van der Waals heterostructure. Nano Lett. 20, 1620–1630 (2020).

Hou, X. et al. Alloy engineering in few‐layer manganese phosphorus trichalcogenides for surface‐enhanced Raman scattering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1910171 (2020).

Yang, H., Mo, H., Zhang, J., Hong, L. & Li, Z.-Y. Observation of single-molecule Raman spectroscopy enabled by synergic electromagnetic and chemical enhancement. PhotoniX 5, 3 (2024).

Adar, F., Lee, E., Mamedov, S. & Whitley, A. Experimental evaluation of the depth resolution of a Raman microscope. Microsc. Microanal. 16, 360–361 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the supports from the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Nos. 2022A1515140158 to W.C., 2023A1515110759 to C.T., and 2023A1515011752 to B.L.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51991343, 51991340, 52102179, and 52188101 to B.L., and 12304212 to S.Z.), the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (No. 52125309 to B.L.), the Shenzhen Basic Research Program (Nos. JCYJ20200109144616617 and JCYJ20220818101014029 to B.L.), the Guangdong Research Fund (No. 2024LH7-3 to B.Z.). This work made use of the TEM facilities at the Institute of Materials Research, Tsinghua Shenzhen International Graduate School (Tsinghua SIGS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.C., C.T., S.Z., and H.-M.C. conceived the research and supervised the project. W.C., C.T., and S.Z. designed the experiments. W.C. and J.G. carried out the main experiments. X.W. prepared the wrinkled MnPS3 samples, fabraicated and measured the MnPS3-based devices. J.T. and B.L. performed the HADDF-TEM characterization. J.H. conducted the XPS and XRD characterizations and collected absorption spectra. Z.L., B.Z., L.-H.W., and X.-A.Z. analyzed the SERS data. W.C., C.T., and S.Z. analyzed all experimental results, organized the figures, and drafted the paper. B.D., B.L., and H.-M.C. helped wrote and revised the paper. All authors contributed to scientific discussion, checked the paper, and agreed with its content.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Minqiang Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, W., Gui, J., Weng, X. et al. Mechanochemical activation of 2D MnPS3 for sub-attomolar sensing. Nat Commun 15, 10195 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54608-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54608-0