Abstract

Understanding competing charge density wave (CDW) orders in the bilayer kagome metal ScV6Sn6 remains challenging. Experimentally, upon cooling, short-range order with wave vector \({{{{\bf{q}}}}}_{2}=(\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{2})\) forms, which is subsequently suppressed by the condensation of long-range \({{{{\bf{q}}}}}_{3}=(\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{3})\) CDW order at lower temperature. Theoretically, however, the q2 CDW is predicted as the ground state, leaving the CDW mechanism elusive. Here, using anharmonic phonon-phonon calculations combined with density functional theory, we predict a temperature-driven structural phase transitions from the high-temperature pristine phase to the q2 CDW, followed by the low-temperature q3 CDW, explaining experimental observations. We demonstrate that semi-core electron states stabilize the q3 CDW over the q2 CDW. Furthermore, we find that the out-of-plane lattice parameter controls the competing CDWs, motivating us to propose compressive bi-axial strain as an experimental protocol to stabilize the q2 CDW. Finally, we suggest Ge or Pb doping at the Sn site as another potential avenue to control CDW instabilities. Our work provides a full theory of CDWs in ScV6Sn6, rationalizing experimental observations and resolving earlier discrepancies between theory and experiment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Kagome materials have emerged as promising platforms to study novel quantum phases of matter that arise from the interplay between lattice geometry, band topology, and electronic correlations1,2,3. Typical electronic band structures of kagome materials include Dirac points, flat bands, and van Hove singularities, serving as rich sources for a variety of structural and electronic instabilities4,5,6,7,8. Indeed, exotic electronic states such as superconductivity9,10,11, charge density waves (CDWs)9,12,13,14,15, pair density waves16, non-trivial topological states9,17, and electronic nematicity18, have been observed in representative kagome metals AV3Sb5 (A=K, Rb, and Cs)19. Of these, the CDW state exhibits unconventional properties including time-reversal and rotational symmetry breaking12,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26, and an unconventional interplay with superconductivity featuring a double superconducting dome27,28,29,30. This has sparked remarkable interest and controversy, prompting the exploration of other material candidates in the quest for a comprehensive understanding of the CDW state in kagome materials.

In this context, the newly discovered bilayer kagome metals RV6Sn6 (R is a rare-earth element) have attracted much attention31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51. Among the RV6Sn6 series, the non-magnetic ScV6Sn6 compound is the only one that has been reported to undergo a CDW transition, which occurs below TCDW ≈ 92 K38. The wave vector \({{{{\bf{q}}}}}_{3}=(\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{3})\), often described as corresponding to a \(\sqrt{3}\times \sqrt{3}\times 3\) periodicity in real space, has been identified as the ordering vector of the CDW state through x-ray diffraction (XRD)38, neutron diffraction38, and inelastic x-ray scattering (IXS)39,40. The in-plane \(\sqrt{3}\times \sqrt{3}\) periodicity has been further confirmed using surface-sensitive techniques such as scanning tunneling microscopy41,42 and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy42,43. It has also been established that the CDW distortion is dominated by out-of-plane displacements of Sc and Sn atoms38,47, which exhibit strong electron-phonon coupling39,40,42,48. Interestingly, short-range order with \({{{{\bf{q}}}}}_{2}=(\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{2})\), corresponding to \(\sqrt{3}\times \sqrt{3}\times 2\) periodicity, has been detected above TCDW, but it is supressed below TCDW when the dominant q3 CDW develops39,40,48.

On the theoretical front, density functional theory (DFT) calculations have reproduced the competing CDW orders47, but all previous DFT studies have found that the q2 CDW order is the lowest energy ground state39,47,52,53,54, in stark contrast to experimental reports. Various mechanisms have been proposed to explain the observed q3 CDW ground state, including configurational entropy52, the order-by-disorder mechanism53, and large fluctuations from flat phonon soft modes54. These scenarios are based on harmonic phonon dispersions, which exhibit multiple imaginary phonon modes and a theory capable of quantitatively explaining the temperature-driven phase transition from the q2 order to the q3 CDW order is missing. Moreover, the inclusion of electronic temperature in DFT calculations is also insufficient to predict the observed CDW transition, which is overestimated by thousands of degrees. These discrepancies between theoretical models and experimental observations pose a key challenge to achieving a comprehensive understanding of CDW states in bilayer kagome metals.

In this work, we present a first principles theory of CDW order in ScV6Sn6 that explains the reported experimental observations and resolves earlier discrepancies between theory and experiment. Our theory is based on the inclusion of anharmonic phonon-phonon interactions, and captures the observed temperature dependence of charge orders, with a q2 distortion occurring at a higher temperature that is subsequently suppressed by the dominant low-temperature q3 charge ordering. Moreover, we calculate a phase diagram comparing the two charge orders as a function of the in-plane and out-of-plane lattice parameters, and suggest a clear pathway for using compressive bi-axial strain to experimentally stabilize a CDW with a dominant q2 wave vector in ScV6Sn6. We also predict that Ge or Pb doping at the Sn site can control CDW order, and propose ScV6Pb6 as another CDW material within the 166 kagome family. Finally, we rationalize discrepant earlier theoretical models by highlighting that the relative stability of the competing CDW states in ScV6Sn6 exhibits a complex dependence on the number of valence electrons included in the calculations and on the out-of-plane lattice parameter.

Results and discussion

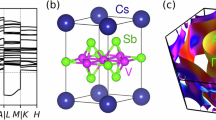

The high temperature pristine phase of ScV6Sn6 crystallizes in the hexagonal space group P6/mmm (Fig. 1a). The primitive cell contains one Sc atom (Wyckoff position 1a), six equivalent V atoms (6i), and three pairs of nonequivalent Sn atoms, labeled as Sn1 (2e), Sn2 (2d ), and Sn3 (2c). The crystal structure consists of two kagome layers of V and Sn1 atoms, a triangular layer of Sc and Sn3 atoms, and a honeycomb layer of Sn2 atoms. In the two kagome layers, the Sn1 atoms buckle in opposite directions relative to each V kagome sublattice. The Sn1 and Sc atoms form a chain along the c axis. Notably, the smallest R-site ion radius of ScV6Sn6 among the RV6Sn6 series leads to the formation of Sn1-Sc-Sn1 trimers mediated by a shortening of the Sc-Sn1 bonds and an elongation of the Sn1-Sn1 bonds along the chain. This unique structural feature results in more space for the Sn1-Sc-Sn1 trimers to vibrate along the c direction, a characteristic absent in other RV6Sn6 compounds without a trimer formation, which has been demonstrated to be crucial to the formation of the CDW44,48. Motivated by this observation, the calculations reported below are performed using the PBEsol exchange-correlation functional55, which gives better agreement with the experimentally measured out-of-plane lattice parameter compared to the often-used PBE exchange-correlation functional56. Nonetheless, the overall conclusions of our work are independent of the exchange-correlation functional used (See Supplementary Note 2).

a Crystal structure of pristine ScV6Sn6. b, c CDW displacement patterns (blue arrows) for the b q3 (\(\sqrt{3}\times \sqrt{3}\times 3\)) and c q2 (\(\sqrt{3}\times \sqrt{3}\times 2\)) orders. The arrows are calculated through the structural difference of the relaxed CDW structure and the pristine structure. d Harmonic (gray) and anharmonic (red) phonon dispersions of pristine ScV6Sn6. The inset shows the Brillouin zone of pristine ScV6Sn6 with certain high symmetry points labeled. The prime notation designates the high symmetry points on the \({q}_{z}=\frac{1}{3}\) plane.

Figure 1d shows the calculated harmonic and anharmonic phonon dispersions of pristine ScV6Sn6. The harmonic phonon dispersion shows multiple dynamical instabilities, which appear as imaginary frequencies in the phonon dispersion (represented by the gray area in Fig. 1d). The harmonic instabilities span a wide region of the Brillouin zone, including the whole \({q}_{z}=\frac{1}{2}\) plane represented by the A-L-H-A closed path, and also including other values of qz, for example the \({K}^{{\prime} }\) point at the \({q}_{z}=\frac{1}{3}\) plane. Specifically, the calculated harmonic instabilities include the CDW instabilities reported experimentally with wave vectors q3 and q2, which correspond to the \({K}^{{\prime} }\) and H points of the Brillouin zone, respectively; but also include many other instabilities. Interestingly, when anharmonic phonon-phonon interactions57,58,59 are included, most harmonic instabilities disappear, leaving only two at the \({K}^{{\prime} }\) and H points at finite temperatures. This aligns with available experimental reports, which observe only those two instabilities.

Figure 1b, c illustrate the CDW structures optimized along the imaginary phonon modes at q3 and q2, respectively. The distortions of both CDW orders mainly occur along the Sn1-Sc chains, where the Sn1-Sc-Sn1 trimers are displaced to form × 3 and × 2 CDW periodicities along the c axis for the q3 and q2 orders, respectively. The q3 CDW order involves three trimers exhibiting a stationary-up-down pattern while the q2 CDW order involves two trimers with an up-down pattern. In both CDW orders, the trimers in one Sc1-Sn chain alternate their displacement along the c axis relative to the other Sc1-Sn chains, resulting in the \(\sqrt{3}\times \sqrt{3}\) in-plane periodicity.

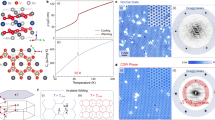

To further characterize the CDW of ScV6Sn6, we investigate the temperature dependence of phonon dispersions using anharmonic calculations within the stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation57,58,59. Figure 2a displays the anharmonic phonon dispersion of pristine ScV6Sn6 at temperatures of 0 K, 50 K, 100 K and 200 K. The majority of phonon branches show a negligible temperature dependence, with the key exception of a pronounced softening of the lowest energy phonon branch at q2 (H point) and q3 (\({K}^{{\prime} }\) point) upon cooling. The squared frequency ω2 of the soft modes should exhibit a linear behavior with respect to temperature near the vanishing point60, and we use a linear fit to extract the transition temperatures T* associated with each phonon softening (Fig. 2b). At high temperature (200 K), the pristine ScV6Sn6 phase is dynamically stable and the phonon frequencies at both q vectors are real. Interestingly, the frequency at q2 becomes imaginary at a higher temperature of 140 K compared to the temperature of 84 K at which the frequency at q3 becomes imaginary. This implies that, starting from the high temperature pristine phase, the first distortion to develop with decreasing temperature is that associated with q2, rationalizing the short-range q2 order above the q3 CDW transition temperature observed in XRD48 and IXS40.

a Anharmonic phonon dispersions at 0 K, 50 K, 100 K, and 200 K. b Squared phonon frequency ω2 of the lowest energy phonon modes at the H and \({K}^{{\prime} }\) points with respect to ionic temperature. The calculated anharmonic frequencies are shown in circles and the experimental results40 are represented by squares. c Helmholtz free energy of the two CDW structures compared to the pristine structure.

Our work clearly identifies anharmonic phonon-phonon interaction as the driving mechanism underlying the observed temperature-induced CDW transition in ScV6Sn6. In this context, our anharmonic phonon results exhibit remarkable quantitative agreement with experimental data (Fig. 2b). This should be contrasted with the significant overestimation of temperature scales (with critical temperatures of 2000 K and 5500 K) obtained by adjusting electronic temperature only via changing smearing values in harmonic phonon calculations (See Supplementary Note 3).

Comparing the calculated Helmholtz free energy between the q2 and q3 CDW orders, we observe a crossover from q2 to q3 CDWs (Fig. 2c). The q2 CDW order is more stable at high temperature and the free energy difference decreases as the temperature decreases. The crossover occurs approximately at Tc = 43 K, which is lower than the onset of the q3 CDW instability T* = 84 K in Fig. 2b. The predicted transition temperature Tc of the q3 CDW (≈ 43 K) is lower than experimental values of 92 K61 and 84 K48. This quantitative discrepancy is attributed to the sensitivity of Tc on the volume of the system, as discussed in detail below, and more generally to the inherent temperature-independent limitations of DFT calculations, such as those arising from the choice of exchange-correlation functional. At 0 K, the q3 CDW structure is more stable by 1.80 meV/f.u. compared to the q2 CDW structure.

Our DFT calculations correctly predict the q3 CDW to be the lowest energy ground state, consistent with experiments38,39,40,48. Puzzlingly, all earlier DFT studies47,52,53 had predicted the q2 distortion to be the ground state, in stark contrast to the experimental reports and to our results. To rationalize this, we highlight that in our calculations we have established that the inclusion of electronic semi-core states in the valence is necessary to stabilize the q3 CDW order (Fig. 3). Using a standard pseudopotential with valence electrons 3d14s2 for Sc atoms and 5s25p2 for Sn atoms, which excludes the semi-core states from the valence, the total electronic energy of the q2 CDW is lower than that of the q3 CDW by 0.52 meV/f.u. (Fig. 3a), a conclusion reached by previous DFT calculations47,52,53,54. The q2 CDW remains the ground state in the free energy, stabilized by 0.44 meV/f.u. over the q3 CDW (Fig. 3b). The free energy includes both total electronic energy and phonon energy, with phonon contributions encompassing both harmonic and anharmonic zero-point energy at 0 K. By contrast, a pseudopotential that includes the s and p semi-core states in Sc atoms and the d semi-core states in Sn atoms as valence states, predicts the q3 CDW to be the ground state, regardless of phonon contributions. The q3 CDW structure is further stabilized upon considerinng phonon contributions, increasing the energy difference between the q2 and q3 CDWs from 0.47 to 1.80 meV/f.u. (Fig. 3a, b).

a Total electronic energy and (b) free energy of CDW states relative to the pristine state at 0 K with and without including semi-core states as valence states. The free energy contains total electronic energy and phonon energy that arises from both harmonic and anharmonic quantum effects. c, d Electronic band structures and density of states (DOS) calculated with and without treating semi-core states as valence states for (c) the q2 and d the q3 CDW states. The semi-core states refer to the 3s and 3p orbitals of Sc atoms and the 4d orbitals of Sn atoms.

To gain further insight into the role of the pseudopotential, we analyse the effect of semi-core states on the electronic structures of the q2 and q3 distorted phases (Fig. 3c, d). We find that including semi-core states shifts the overall band dispersions and DOS of the occupied states upward, leading to a reduced total energy gain of both CDW states upon formation from the pristine structure (Fig. 3a). Specifically, the total energy gain of the CDW structures over the pristine structure decreases from −3.43 to −1.95 meV/f.u. for the q2 CDW, and from −2.91 to −2.42 meV/f.u. for the q3 CDW. The larger reduction in total energy gain for the q2 CDW is attributed to more significant changes in its electronic structure arising from larger structural changes in the q2 CDW, particularly in the bond lengths in the Sn1-Sc-Sn1 chains. These bond lengths change by up to 0.065 Å in the q2 CDW, compared to a maximum change of 0.022 Å in the q3 CDW upon the inclusion of semi-core states (see Supplementary Table S4 for details). This demonstrates that semi-core effects have a more pronounced impact on the q2 CDW than on the q3 CDW. Furthermore, unlike in the q3 CDW state, we observe that semi-core states affect the electronic structure near the Fermi level in the q2 CDW. The atom-projected DOS shows that the Sc and Sn1 states, which are responsible for the CDW state, are particularly influenced, suggesting that the corrections in the Sn1-Sc-Sn1 chains alter the Fermi surface and associated properties.

The validity of our theoretical calculations is confirmed by cross-checking with pseudopotential-free all-electron wien2k calculations (see Supplementary Note 4). We find that the vasp results, obtained by including semi-core states as valence, show remarkable agreement with the wien2k results in terms of the total energy of both pristine and CDW structures, as well as their atomic and electronic structures. Overall, this demonstrates that the inclusion of semi-core electron states in the valence is necessary to obtain a theoretical model that correctly predicts the ground state CDW order of ScV6Sn6. This explains and resolves the outstanding discrepancy between theory and experiment, and provides a foundation for the predictive model of the CDW state in bilayer kagome ScV6Sn6 described above. Additionally, we note that the calculated energy difference between the two CDWs is small (less than 2 meV/f.u.), highlighting the competing nature of the two CDWs in ScV6Sn6. This suggests that the competition between the two CDW orders can be easily manipulated via external perturbations, as discussed in detail below.

Having established the correct theory of the competing CDWs in ScV6Sn6, we explore the phase diagram in lattice parameter space which provides important insights for manipulating the competing CDWs. Figure 4a shows a phase diagram of the q2 and the q3 CDW orders as a function of the in-plane and out-of-plane lattice parameters. We find that the out-of-plane lattice parameter holds the key to control competing the CDW orders. This can be rationalized by noting that the out-of-plane lattice parameter determines the space available for the distortions of adjacent Sn1-Sc-Sn1 trimers and thus dominates the energetics between competing CDWs. A smaller out-of-plane lattice parameter restricts the available space for Sn1-Sc-Sn1 trimers to distort, favoring an additional stationary configuration of trimers in q3 CDW. Conversely, a larger out-of-plane lattice parameter facilitates the collective distortions of trimers and favors the q2 CDW.

a Phase diagram of the competing q2 and q3 CDW orders in the in-plane and out-of-plane lattice parameter space. Color bar represents the total energy difference between the q2 and q3 structures. The gray dashed line shows the change of lattice parameters under in-plane biaxial strain. b Relative enthalpy H = E + PV of the q2 and q3 CDWs to pristine structure. Vertical dashed line indicates the experimental value of critical pressure of 2.4 GPa that CDW orders are totally suppressed45. c Total energy of the q2 and q3 CDWs as a function of in-plane biaxial strain.

In addition, we discuss the effects of the hydrostatic pressure and in-plane biaxial strain on the competing CDWs. Hydrostatic pressure suppresses both CDW orders (Fig. 4b), as increasing pressure decreases the out-of-plane lattice parameter and thus the space available for Sn1-Sc-Sn1 trimers to distort. Our theoretical value for the critical pressure (≈ 2.8 GPa) at which the q3 CDW disappears is in remarkable agreement with the experimental value of 2.4 GPa45. Similary, in-plane biaxial tensile strain leads to a decrease in the out-of-plane lattice parameter, suppressing both CDW orders (Fig. 4c). By contrast, in-plane compressive strain increases the out-of-plane lattice parameter, enhancing the stability of both CDW orders. Interestingly, the q2 CDW order becomes the ground state under the compressive strain. The predicted value of critical compressive strain is just around 1%, which should be experimentally accessible. These predictions warrant further experimental studies to corroborate our findings.

Finally, we propose the doping of Pb or Ge at the Sn site as a further strategy to control competing CDWs in ScV6Sn6 and to explore the microscopic mechanisms underlying CDW instabilities within the 166 bilayer kagome family. To investigate the effect of doping, we fully substitute the Sn atom with other Group 14 elements, Ge and Pb. Figure 5a displays the harmonic phonon dispersion of ScV6Pb6 (red lines) and ScV6Ge6 (black lines). The phonon dispersion of ScV6Pb6 shows imaginary modes at the L and H points, indicating CDW instabilities. The calculated total energy (Fig. 5b) confirms that ScV6Pb6 has a CDW ground state, with the L distortion slightly favored over the q2 distortion. We note that the q3 instability is not present in this compound. In contrast, ScV6Ge6 exhibits no imaginary modes, consistent with the calculated total energy showing that the CDW structure is unstable compared to the pristine structure. The bond ratio d2/d1 in X-Sc-X chains within the ScV6X6 compounds (X = Ge, Sn, and Pb) is an important indicator for the emergence of CDWs, with the ratio increasing as the atomic radius increases from Ge to Pb (Fig. 5c). A larger bond ratio is one of the necessary conditions for CDWs to emerge in this kagome system, as the CDWs displacement patterns consist of the vibration of X-Sc-X trimers. These vibrations are promoted by the larger bond difference between X-Sc and X-X atoms, which corresponds to a larger bond ratio. In the case of ScV6Sn6, the bond ratio is reduced to nearly 1 when Sc is substituted by larger atoms like Y or Gd, leading to the disappearance of CDWs44. Similarly, in ScV6Ge6, the bond ratio is close to 1, making trimerisation unfavorable and resulting in the absence of CDWs. Additionally, we find that there exists an optimal range of bond ratios that drive CDW formation, as the calculated energy gain of CDW states over the pristine structure diminishes in the Pb case compared to the Sn case, despite Pb having a larger bond ratio.

a Harmonic phonon dispersions of ScV6Ge6 and ScV6Pb6. b Total energy of various CDW structures relative to the pristine structure in ScV6X6 materials (X=Ge, Sn, and Pb). c Bond ratio d2/d1 in X-Sc-X chains and out-of-plane lattice parameter in the pristine structure of ScV6X6 materials (X=Ge, Sn, and Pb).

We note that the q3 CDW order is less stable compared to the pristine case in both the Ge and Pb compounds, and thus cannot be observed. In the Pb case, our theory predicts that the L and H (q2) CDWs are dominant, which we speculate is due to the larger out-of-plane lattice parameters (Fig. 5c), where we leave the detailed characterization as future work. Our results suggest that partial doping of Pb or Ge at the Sn site could suppress the q3 distortion, potentially leading to the dominance of the q2 CDW. We also predict ScV6Pb6 as a new CDW compound within the 166 bilayer kagome family. These predictions warrant further experimental studies to explore the role of doping in ScV6Sn6.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the decisive role of temperature, captured by anharmonic phonon-phonon interactions, and volume, on the competition between the q2 and q3 charge orders in ScV6Sn6. Our work fully resolves the controversy between previous theoretical and experimental studies: a correct theoretical description of CDW order requires the inclusion of semi-core electron states as valence, and the use of a correct out-of-plane c lattice parameter. Our theory also elucidates the experimentally observed temperature-induced CDW phase transition from a high temperature q2 to a low temperature q3 order. Finally, we predict that in-plane biaxial strain can be used to manipulate the competing CDW orders, and propose that compressive strain could be used to experimentally discover a regime in which the q2 CDW dominates. We also suggest Ge or Pb doping at the Sn site can tune the competing CDW orders, and we predict ScV6Pb6 as a new CDW material, stimulating future experimental works. More generally, our findings contribute to the wider effort of understanding CDW states in kagome metals, including the prototypical CsV3Sb519 and magnetic FeGe62, where the origin of the CDW states remains an open question13,23,63,64,65,66,67. Moreover, our work provides important insight into understanding and manipulating multiple CDW instabilities, such as those in CsV3Sb5 under doping and pressure29,30 as well as in the recently discovered room temperature CDW kagome metal LaRu3Si268,69.

Methods

Electronic structure calculations

We perform density functional theory (DFT) calculations using the Vienna ab initio simulation package vasp70,71 implementing the projector-augmented wave method72. We use PAW pseudopotentials with valence configurations: 3s23p63d14s2 (3d14s2) for Sc atoms, 3s23p64s23d3 (4s23d3) for V atoms, and 5s24d105p2 (5s25p2) for Sn atoms for the cases with (without) semi-core states. We approximate the exchange correlation functional with the generalized-gradient approximation PBEsol55 in the calculations reported in the main text. For comparison, we also perform calculations using the PBE56 exchange-correlation functional. We use a kinetic energy cutoff for the plane wave basis of 500 eV and a Methfessel-Paxton smearing of 0.02 eV. We use a Γ-centered k-point grid of size 15 × 15 × 8 for the primitive cell and commensurate k-point grids for the supercell calculations. All the structures are optimized until the forces are below 0.005 eV/Å. We perform a cross-check of the electronic structure calculations using the castep73 package (see Supplementary Note 1.2 for details), with norm-conversing pseudopotentials generated on-the-fly (NCP19), and employing identical valence configurations as those used in vasp calculations, including semi-core states. We also use the PBEsol55 exchange-correlation functional. We choose a kinetic energy cutoff for the plane wave basis of 1000 eV with a Gaussian smearing of 0.02 eV. We use a Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid with an applied half step shift if the number of k-points is even, which generates the exact same Gamma-centered k-point grid as that used in the vasp calculations. All the structures are optimized until the forces are below 0.005 eV/Å.

We also perform DFT calculations using the full-potential linearized augmented plane wave (FP-LAPW) method as implemented in the wien2k code74 using the PBEsol55 exchange-correlation functional. We use self-consistency cycle stopping criteria of 1 × 10−6 Ry for the energy and 1 × 10−4 e for the charge. The radii (R) of the muffin-tin (MT) spheres are taken to be 2.40, 2.26, and 2.38 Bohr for Sc, V, and Sn atoms, respectively. RMT × Kmax is set to 8.5 (confirming that using 9 yields the same results), where Kmax is the cutoff value of the modulus of the reciprocal lattice vectors and RMT is the smallest MT radius. The cutoff energy separating core and valence states is set to −136 eV, with the valence electrons treated as 3s23p64s23d1 for Sc atoms, 3s23p64s23d3 for V atoms, and 4s24p64d105s25p2 for Sn atoms. All the structures are optimized until the forces are below 0.5 mRy/Bohr.

Harmonic phonon calculations

We perform harmonic phonon calculations using the finite displacement method in conjunction with nondiagonal supercells75,76. The dynamical matrices are calculated on a Farey nonuniform q grid77 of size (3 × 3 × 2) ∪ (3 × 3 × 3), which is commensurate with both q2 and q3. The final dynamical matrix is calculated through the force constant matrix on a target uniform q grid of size 3 × 3 × 6.

Anharmonic phonon calculations

The anharmonic phonon calculations are performed using the stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation (SSCHA)57,58,59, which is a non-perturbation method taking into account anharmonic effects at both zero and finite temperature. The free energy of the real system is variationally minimized with respect to an auxiliary harmonic system. This is done using stochastic importance sampling, in which the total energy, forces, and stresses for an ensemble of configurations of the auxiliary harmonic system are calculated using vasp. The associated electronic structure calculations are performed using a kinetic energy cutoff 300 eV, and we consider configurations commensurate with a 3 × 3 × 2 supercell and a 3 × 3 × 3 supercell. The number of configurations needed to converge the free energy Hessian is of the order of 1000. A Farey nonuniform q grid of size (3 × 3 × 2) ∪ (3 × 3 × 3) is used to get commensurate phonon results at both q2 and q3 (see Supplementary Note 1.1 for details). To get better prediction of the CDW transition temperature, the lattice parameters are fixed to the experimental values38. To obtain a more accurate energy comparison, the free energy calculations are performed using the same parameters as the electronic structure calculations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the paper and Supplementary Information. All other relevant data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

The vasp code used in this study is a commercial electronic structure modeling software, available from https://www.vasp.at. The Quantum Espresso code used in this research is open source: https://www.quantum-espresso.org/. The castep code used in this study is freely available at https://www.castep.org/for academic research. The Wien2k code used in this study is a commercial software, available from http://susi.theochem.tuwien.ac.at/.

References

Yin, J.-X., Pan, S. H. & Zahid Hasan, M. Probing topological quantum matter with scanning tunnelling microscopy. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 249–263 (2021).

Neupert, T., Denner, M. M., Yin, J.-X., Thomale, R. & Hasan, M. Z. Charge order and superconductivity in kagome materials. Nat. Phys. 18, 137–143 (2022).

Jiang, K. et al. Kagome superconductors AV3Sb5 (A = K, Rb, Cs). Nat. Sci. Rev. 10, nwac199 (2022).

Wen, J., Rüegg, A., Wang, C.-C. J. & Fiete, G. A. Interaction-driven topological insulators on the kagome and the decorated honeycomb lattices. Phys. Rev. B 82, 075125 (2010).

Tang, E., Mei, J.-W. & Wen, X.-G. High-temperature fractional quantum hall states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 236802 (2011).

Sun, K., Gu, Z., Katsura, H. & Das Sarma, S. Nearly flatbands with nontrivial topology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 236803 (2011).

Kiesel, M. L., Platt, C. & Thomale, R. Unconventional Fermi surface instabilities in the kagome Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 126405 (2013).

Wang, W.-S., Li, Z.-Z., Xiang, Y.-Y. & Wang, Q.-H. Competing electronic orders on kagome lattices at van Hove filling. Phys. Rev. B 87, 115135 (2013).

Ortiz, B. R. et al. CsV3Sb5: a Z2 topological kagome metal with a superconducting ground state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 247002 (2020).

Ortiz, B. R. et al. Superconductivity in the Z2 kagome metal KV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 034801 (2021).

Yin, Q. et al. Superconductivity and normal-state properties of kagome metal RbV3Sb5 single crystals. Chin. Phys. Lett. 38, 037403 (2021).

Jiang, Y.-X. et al. Unconventional chiral charge order in kagome superconductor KV3Sb5. Nat. Mater. 20, 1353–1357 (2021).

Tan, H., Liu, Y., Wang, Z. & Yan, B. Charge density waves and electronic properties of superconducting kagome metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 046401 (2021).

Zhao, H. et al. Cascade of correlated electron states in the kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Nature 599, 216–221 (2021).

Liang, Z. et al. Three-dimensional charge density wave and surface-dependent vortex-core states in a kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. X 11, 031026 (2021).

Chen, H. et al. Roton pair density wave in a strong-coupling kagome superconductor. Nature 599, 222–228 (2021).

Hu, Y. et al. Topological surface states and flat bands in the kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Sci. Bull. 67, 495–500 (2022).

Nie, L. et al. Charge-density-wave-driven electronic nematicity in a kagome superconductor. Nature 604, 59–64 (2022).

Ortiz, B. R. et al. New kagome prototype materials: discovery of KV3Sb5, RbV3Sb5, and CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 094407 (2019).

Yang, S.-Y. et al. Giant, unconventional anomalous Hall effect in the metallic frustrated magnet candidate, KV3Sb5. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb6003 (2020).

Kang, M. et al. Twofold van Hove singularity and origin of charge order in topological kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Nat. Phys. 18, 301–308 (2022).

Mielke, C. et al. Time-reversal symmetry-breaking charge order in a kagome superconductor. Nature 602, 245–250 (2022).

Denner, M. M., Thomale, R. & Neupert, T. Analysis of charge order in the kagome metal AV3Sb5 (A = K,Rb,Cs). Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 217601 (2021).

Guo, C. et al. Switchable chiral transport in charge-ordered kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Nature 611, 461–466 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Three-state nematicity and magneto-optical Kerr effect in the charge density waves in kagome superconductors. Nat. Phys. 18, 1470–1475 (2022).

Kim, S.-W., Oh, H., Moon, E.-G. & Kim, Y. Monolayer kagome metals AV3Sb5. Nat. Commun. 14, 591 (2023).

Chen, K. Y. et al. Double superconducting dome and triple enhancement of Tc in the kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 247001 (2021).

Yu, F. H. et al. Unusual competition of superconductivity and charge-density-wave state in a compressed topological kagome metal. Nat. Commun. 12, 3645 (2021).

Zheng, L. et al. Emergent charge order in pressurized kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Nature 611, 682–687 (2022).

Kang, M. et al. Charge order landscape and competition with superconductivity in kagome metals. Nat. Mater. 22, 186–193 (2023).

Pokharel, G. et al. Electronic properties of the topological kagome metals YV6Sn6 and GdV6Sn6. Phys. Rev. B 104, 235139 (2021).

Peng, S. et al. Realizing Kagome band structure in two-dimensional kagome surface states of RV6Sn6 (R=Gd, So). Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 266401 (2021).

Ishikawa, H., Yajima, T., Kawamura, M., Mitamura, H. & Kindo, K. GdV6Sn6: a multi-carrier metal with non-magnetic 3d-electron kagome bands and 4f-electron magnetism. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 90, 124704 (2021).

Hu, Y. et al. Tunable topological Dirac surface states and van Hove singularities in kagome metal GdV6Sn6. Sci. Adv. 8, eadd2024 (2022).

Rosenberg, E. et al. Uniaxial ferromagnetism in the kagome metal TbV6Sn6. Phys. Rev. B 106, 115139 (2022).

Lee, J. & Mun, E. Anisotropic magnetic property of single crystals RV6Sn6(R = Y, Gd − Tm, Lu). Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 083401 (2022).

Di Sante, D. et al. Flat band separation and robust spin Berry curvature in bilayer kagome metals. Nat. Phys. 19, 1135–1142 (2023).

Arachchige, H. W. S. et al. Charge density Wave in kagome lattice intermetallic ScV6Sn6. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 216402 (2022).

Cao, S. et al. Competing charge-density wave instabilities in the kagome metal ScV6Sn6. Nat. Commun. 14, 7671 (2023).

Korshunov, A. et al. Softening of a flat phonon mode in the kagome ScV6Sn6. Nat. Commun. 14, 6646 (2023).

Cheng, S. et al. Nanoscale visualization and spectral fingerprints of the charge order in ScV6Sn6 distinct from other kagome metals. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 1–9 (2024).

Hu, Y. et al. Phonon promoted charge density wave in topological kagome metal ScV6Sn6. Nat. Commun. 15, 1658 (2024).

Lee, S. et al. Nature of charge density wave in kagome metal ScV6Sn6. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 1–8 (2024).

Meier, W. R. et al. Tiny Sc allows the chains to rattle: impact of Lu and Y Doping on the charge-density wave in ScV6Sn6. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 20943–20950 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Destabilization of the charge density wave and the absence of superconductivity in ScV6Sn6 under high pressures up to 11 GPa. Materials 15, 7372 (2022).

Tuniz, M. et al. Dynamics and resilience of the unconventional charge density wave in ScV6Sn6 bilayer kagome metal. Commun. Mater. 4, 1–8 (2023).

Tan, H. & Yan, B. Abundant lattice instability in kagome metal ScV6Sn6. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 266402 (2023).

Pokharel, G. et al. Frustrated charge order and cooperative distortions in ScV6Sn6. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 104201 (2023).

Kang, S.-H. et al. Emergence of a new band and the Lifshitz transition in kagome metal ScV6Sn6 with charge density wave. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.14041 (2023).

Shrestha, K. et al. Electronic properties of kagome metal ScV6Sn6 using high-field torque magnetometry. Phys. Rev. B 108, 245119 (2023).

Yi, C. et al. Quantum oscillations revealing topological band in kagome metal ScV6Sn6. Phys. Rev. B 109, 035124 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Driving mechanism and dynamic fluctuations of charge density waves in the kagome metal SnV6Sn6. Phys. Rev. B 109, L121103 (2024).

Subedi, A. Order-by-disorder charge density wave condensation at \(q=(\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{3})\) in kagome metal ScV6Sn6. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, 014006 (2024).

Hu, H. et al. Kagome Materials I: SG 191, ScV6Sn6. Flat Phonon Soft Modes and Unconventional CDW Formation: Microscopic and Effective Theory. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.15469 (2023).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Errea, I., Calandra, M. & Mauri, F. Anharmonic free energies and phonon dispersions from the stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation: application to platinum and palladium hydrides. Phys. Rev. B 89, 064302 (2014).

Bianco, R., Errea, I., Paulatto, L., Calandra, M. & Mauri, F. Second-order structural phase transitions, free energy curvature, and temperature-dependent anharmonic phonons in the self-consistent harmonic approximation: theory and stochastic implementation. Phys. Rev. B 96, 014111 (2017).

Monacelli, L. et al. The stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation: calculating vibrational properties of materials with full quantum and anharmonic effects. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 33, 363001 (2021).

Cochran, W. Crystal stability and the theory of ferroelectricity. Adv. Phys. 9, 387–423 (1960).

Ahsan, T., Hsu, C.-H., Hossain, M. S. & Hasan, M. Z. Prediction of strong topological insulator phase in kagome metal RV6Sn6. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 104204 (2023).

Teng, X. et al. Discovery of charge density wave in a kagome lattice antiferromagnet. Nature 609, 490–495 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Observation of unconventional charge density wave without acoustic phonon anomaly in kagome superconductors AV3Sb5 (A=Rb,Cs). Phys. Rev. X 11, 031050 (2021).

Liu, G. et al. Observation of anomalous amplitude modes in the kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Nat. Commun. 13, 3461 (2022).

He, G. et al. Anharmonic strong-coupling effects at the origin of the charge density wave in CsV3Sb5. Nat. Commun. 15, 1895 (2024).

Gutierrez-Amigo, M. et al. Phonon collapse and anharmonic melting of the 3D charge-density wave in kagome metals. Commun. Mater. 5, 1–8 (2024).

Teng, X. et al. Magnetism and charge density wave order in kagome FeGe. Nat. Phys. 19, 814–822 (2023).

Mielke, C. et al. Nodeless kagome superconductivity in LaRu3Si2. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 034803 (2021).

Plokhikh, I. et al. Discovery of charge order above room-temperature in the prototypical kagome superconductor La(Ru1−xFex)3Si2. Commun. Phys. 7, 1–8 (2024).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comp. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Clark, S. J. et al. First principles methods using CASTEP. Z. Kristallogr. 220, 567–570 (2005).

Blaha, P. et al. WIEN2k: an APW+lo program for calculating the properties of solids. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 074101 (2020).

Lloyd-Williams, J. H. & Monserrat, B. Lattice dynamics and electron-phonon coupling calculations using nondiagonal supercells. Phys. Rev. B 92, 184301 (2015).

Monserrat, B. Electron-phonon coupling from finite differences. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 30, 083001 (2018).

Chen, S., Salzbrenner, P. T. & Monserrat, B. Nonuniform grids for Brillouin zone integration and interpolation. Phys. Rev. B 106, 155102 (2022).

Acknowledgements

K.W., S.-W.K., and B.M. are supported by a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship [MR/V023926/1], and S.C. and B.M. are supported by a EPSRC grant [EP/V062654/1]. S.C. also acknowledges financial support from the Cambridge Trust and from the Winton Program for the Physics of Sustainability. B.M. also acknowledges support from the Gianna Angelopoulos Program for Science, Technology, and Innovation, and from the Winton Program for the Physics of Sustainability. The computational resources were provided by the Cambridge Tier-2 system operated by the University of Cambridge Research Computing Service and funded by EPSRC [EP/P020259/1] and by the UK National Supercomputing Service ARCHER2, for which access was obtained via the UKCP consortium and funded by EPSRC [EP/X035891/1].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-W.K. and B.M. conceived the study and planned and supervised the research. K.W., S.C., and S.-W.K. performed the DFT calculations, K.W. performed the SSCHA calculations. All authors contributed to the analysis. K.W., S.-W.K., and B.M. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, K., Chen, S., Kim, SW. et al. Origin of competing charge density waves in kagome metal ScV6Sn6. Nat Commun 15, 10428 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54702-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54702-3

This article is cited by

-

Discovery of high-temperature charge order and time-reversal symmetry-breaking in the kagome superconductor YRu3Si2

Nature Communications (2025)