Abstract

The development of efficient and stable electrocatalysts for water oxidation in acidic media is vital for the commercialization of the proton exchange membrane electrolyzers. In this work, we successfully construct Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces for acidic oxygen evolution reaction (OER). The catalysts achieve overpotentials as low as 167, 300, and 390 mV at 10, 500, and 1500 mA cm−2 in 0.5 M H2SO4, respectively, with the electrocatalyst showing robust stability for >1000 h of operation at 10 mA cm−2 and negligible degradation after 200,000 cyclic voltammetry cycles. Operando spectroelectrochemical measurements together with theoretical investigations reveal that the OER pathway over the Ru–O–Ir active site is near-optimal, where the bridging oxygen site of Ir–OBRI serves as the proton acceptor to accelerate proton transfer on an adjacent Ru centre, breaking the typical adsorption-dissociation linear scaling relationship on a single Ru site and thus enhancing OER activity. Here, we show that rational design of multiple active sites can break the activity/stability trade-off commonly encountered for OER catalysts, offering good approaches towards high-performance acidic OER catalysts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water electrolysis, in conjunction with the electric energy supplied by wind turbines and photovoltaics, is a near-ideal technology for the production of green hydrogen and is essential to global decarbonization efforts1,2. Acidic proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolysis, which allows high proton conduction, a fast system response and relatively large working current densities, offers significant advantages over the traditional alkaline water electrolysis3,4,5. However, the high operating voltages, sluggish anodic oxygen evolution reaction (OER) kinetics, and electrocatalyst corrosion/degradation under harsh acidic operating conditions limit the use of PEMWE technologies6,7. The iridium dioxide (IrO2) OER electrocatalyst offers good corrosion resistance, but its high price (~US$140 gIr−1) and low mass activity prevent its large-scale applications. Relative to IrO2, ruthenium dioxide (RuO2) with the rutile structure represents a promising alternative OER electrocatalyst owing to its relatively high catalytic activity and low cost (~US$16 gRu−1)8,9,10. However, the over-oxidation of Ru cations during OER can lead to Ru dissolution and electrocatalyst instability, motivating the search for improved Ru-based electrocatalysts.

Oxygen evolution on RuO2 catalysts has been reported to follow the traditional adsorption evolution mechanism (AEM), for which a low theoretical overpotential of approximately 370 mV is expected due to the limitation imposed by the linear scaling relationship between the adsorption energies of the OH* and OOH* intermediates11,12. To date, various strategies involving defect engineering13,14, element doping15,16,17, morphology regulation18,19,20 and strain engineering21,22 have been exploited to develop high-performance Ru-based catalysts. Previous studies have revealed that modification of the electronic/geometric structure of Ru centres can alter their OER behavior23,24. As reported in a recent work, breaking the Ru–O–Ru symmetry of RuO2 by doping with other elements can induce charge rearrangement and change the d-band centre of the active Ru atoms, leading to a remarkable increase in the OER activity25. For example, introduction of additional metal sites with different ionic electronegativities regulates the Ru charge within Ru–O–M structure motifs, thereby altering the OER route and electrocatalyst stability26,27. Moreover, designing Ru–O–M structure motifs using corrosion-resistant elements to stabilize RuO2 and alter the nature of Ru–O bonding can effectively prevent Ru overoxidation and dissolution during OER28,29. However, such improved stability is usually achieved by sacrificing activity30. Generally, a reduction in the covalency of Ru–O bonding prevents the participation of lattice oxygen in OER; however, for catalysts whose OER process is dominated by the AEM, this leads to relatively high overpotentials due to the restrictions imposed by the aforementioned linear scaling relationship. Strengthening the Ru–O bonding can enhance lattice oxygen redox reaction and boost OER activity. However, the accompanying formation of oxygen vacancies usually results in rapid catalyst degradation31,32. Therefore, most recently reported high-performance RuO2-based OER catalysts still exhibit the problems of low activity and rapid performance decay (<50 h) under high current conditions in traditional three-electrode cells in the laboratory. In view of the activity-stability trade-off and practical demands, it is necessary to break the linear relationship of the AEM via rational construction of Ru–O–M interfaces in RuO2, while preventing the lattice oxygen from participating in the OER, to achieve both high activity and stability at high current densities.

Given the possible existence of nonuniform OER reactions involving adjacent metal atoms and the steric hindrance of lattice oxygen, linear scaling relationships can readily be broken in a multimetal system. Herein, we describe a thermally driven cation exchange strategy to successfully introduce Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces in a RuO2 electrocatalyst (Ir-RuO2, Supplementary Fig. 1). The presence of abundant Ru–O–Ir interfaces in the Ir-RuO2 catalyst was verified using X-ray absorption spectroscopy, aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. At the atomic level, we demonstrate that the introduction of acid-resistant Ir in the atomic form precisely regulated the local Ru–O bonding, with the Ir-RuO2 catalyst delivering both impressive acidic OER activity and stability. Specifically, overpotentials as low as 167 and 390 mV were achieved at 10 and 1500 mA cm−2 for acidic OER, respectively. Furthermore, the electrocatalyst operated stably with long lifetimes of 1023 and 255 h at 10 and 100 mA cm−2 under acidic conditions, respectively, far outperforming commercial RuO2 and IrO2 and most high-performance Ru-based catalysts. The assembled PEMWE, in which Ir-RuO2 was used as the anode, also exhibited high performance requiring only 1.60 V to reach the current density of 1.0 A cm−2 and showing good stability during operation for 300 h. Operando differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS), attenuated total refraction surface-enhanced infrared spectroscopy (ATR-SEIRAS IR) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) studies revealed that the OER pathway was modified over the constructed Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces. Specifically, the bridging oxygen site of Ir–OBRI, which serves as a proton acceptor, can capture H* from the adjacent Ru–OOH* and facilitate its conversion to Ru–OO*, thereby leading to O2 evolution with enhanced kinetics. Density functional theory (DFT) analysis confirmed that multiple active centres within Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces can optimize the configuration of OER intermediates, thus overcoming the thermodynamic limitations of traditional AEM processes. The construction of Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces also inhibits oxygen vacancy formation and the dissolution of active Ru atoms, greatly enhancing electrocatalyst stability during OER.

Results

Electrocatalyst characterization

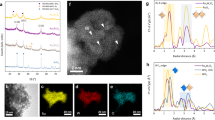

The Ir-RuO2 catalyst was prepared via a rapid, thermally driven cation exchange strategy (see details in the “Materials and Methods”, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). The powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of Ir-RuO2 (Supplementary Fig. 3a) matched that of the rutile RuO2 phase (JCPDS no. 43–1027) with no obvious impurities. The Raman spectrum of Ir-RuO2 was also characteristic of rutile RuO2 (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, inset in Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 4) revealed that Ir-RuO2 consisted of aggregates of nanoparticles. As shown in Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 5, aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-HAADF-STEM) revealed multiple exposed crystal faces of a rutile RuO2 phase on the surface of nanoparticles, where the magnified HAADF-STEM images of Ir-RuO2 (a1 of Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 6) suggest that Ir was atomically dispersed in the RuO2 matrix (marked by dotted circles). The high-resolution STEM image (a2 of Fig. 1a) demonstrated that the lattice fringe spacings of 2.45 and 3.30 Å are assigned to the (101) and (110) facets of RuO2, respectively. The corresponding fast Fourier transform pattern (a3 of Fig. 1a) confirmed the crystalline nature of Ir-RuO2. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX, Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 7) elemental mapping profiles of Ir-RuO2 further verify that Ru, Ir, and O were evenly distributed in the RuO2 matrix with no evident Ir or Ru aggregation. Inductively-coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) analysis indicated that Ir-RuO2 contained approximately 11.2 wt.% Ir in a RuO2 matrix (Supplementary Table 1), indicating an abundance of asymmetric Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces (as illustrated in Fig. 1c). The importation of Ru–O–Ir interfaces in Ir-RuO2 was expected to change the local electronic structure of Ru–O sites, which was expected to greatly affect the OER behavior of RuO29,33. Then, X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) was performed to analyze the chemical structure of Ir-RuO2 after loading with Ir atoms. Figure 1d displays the Ru K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra for Ir-RuO2, Ru metal foil and commercial RuO2 powder (denoted as Com. RuO2). Compared with those of the Ru metal foil, the absorption edge positions for Ir-RuO2 and Com. RuO2 were located at a higher energy due to a higher oxidation state of Ru. The Ru K-edge extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS, Fig. 1e) spectrum of Ir-RuO2 showed two main peaks in R space at 1.48 and 3.16 Å which can be attributed to the Ru–O and Ru–O–Ru/Ir scattering paths, respectively. Notably, Ir-RuO2 shows a slightly increased Ru–O bond length compared with that of Com. RuO2, implying a changed local coordination environment due to the constructed Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces. Considering that the valence orbitals of metal atoms participate directly in bonding with the oxygen intermediates during OER processes34,35, soft X-ray O K-edge XAS tests were also carried out to obtain deeper insights into the modified electronic structure of Ir-RuO2 (Fig. 1f). Two pre-edge peaks at ~529 and ~531 eV were observed for both Ir-RuO2 and Com. RuO2, representing the t2g and eg orbitals hybridized with unoccupied O 2p orbitals, respectively36. Ir-RuO2 and Com. RuO2 showed a difference in the degree of occupancy between the t2g and eg states, confirming the formation of different hybrid structures after the introduction of Ir. Specifically, Ir-RuO2 has relatively weak pre-edge intensities compared with that of Com. RuO2, with the t2g/eg intensity ratio decreasing from 1.18 (Com. RuO2) to 1.07 (Ir-RuO2), suggesting a lower degree of hybridization and more unoccupied orbital states for Ir-RuO2. This indicates the lower covalency between Ru (3d-t2g) orbitals and O 2p for Ir-RuO2 compared to Com. RuO237. Generally, increasing the Ru–O bond lengths through the optimization of the interaction of the Ru 4d and O 2p orbitals increases the OER activity of Ru-based OER catalysts23. Moreover, lowering the Ru–O covalency can inhibit the lattice oxygen-mediated (LOM) OER pathway, which can greatly extend the service life of the catalyst38. Figure 1g shows the Ir L3-edge XANES spectra for Ir-RuO2 and selected reference samples. The absorption edge of Ir-RuO2 was close to that of Com. IrO2 reference sample, indicating an average Ir valence state of close to 4. In the corresponding Ir L3-edge EXAFS spectra (Fig. 1h) of Ir-RuO2, the peak at 1.58 Å in R space can be ascribed to the Ir–O scattering paths (first coordination shell). The Ir–O peak position was slightly lower than that of Com. IrO2 (1.61 Å), suggesting stronger Ir bonding by bridging oxygen (OBRI) at the Ru–O–Ir interfaces, which is expected to suppress the participation of lattice oxygen in OER and enhance the electrocatalyst stability17. The Ir L3-edge wavelet transform (WT)-EXAFS spectra of Ir-RuO2 and Ir metal foil further confirmed this pothesis. The WT-EXAFS plot for Ir-RuO2 exhibited two intensity maxima which can be attributed to Ir–O (R = 1.59 Å and k = 9.60 Å−1) and Ir–O–Ru (R = 3.10 Å and k = 13.20 Å−1) scattering paths (Fig. 1i), respectively. Moreover, no Ir–Ir scattering path associated with Ir metal foil (Fig. 1j) was observed in Ir-RuO2, indicating that Ir existed in atomic form at the Ru–O–Ir interfaces. The surface chemical information of Ir-RuO2 was further studied by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The survey XPS spectrum for Ir-RuO2 (Supplementary Fig. 8) confirmed that the Ir atoms were successfully incorporated into RuO2. The core-level Ir 4f spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 9) showed the peaks at 61.5/64.5 eV and 62.5/65.5 eV that are attributed to Ir4+ and Ir3+, respectively. No peaks due to the Ir0 species were found, further confirming the predominance of atomically-dispersed cationic Ir species in Ir-RuO2. Collectively, our experimental results indicate that the incorporation of Ir atoms impacts both the structural and electronic properties of RuO2, with the abundant Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces having the potential to increase the OER activity in acidic media (as verified by the experiments described below).

a AC-HAADF-STEM image of the Ir-RuO2 catalyst (inset: SEM image of Ir-RuO2, scale bar, 1 μm). a1 and a2 are the temperature-scale and high-resolution STEM images of the selected regions in (a), respectively. a3 shows the fast Fourier transform pattern of the selected region in (a2). Scale bar, 2 nm. b EDX elemental mapping images of Ru, Ir and O atoms on Ir-RuO2. Scale bar, 20 nm. c Crystal structure simulation of the Ir-RuO2 catalyst. d, e Normalized (d) Ru K-edge XANES and (e) FT-K-edge EXAFS spectra for Ir-RuO2. The data for Ru foil and Com. RuO2 are also included for comparison. f O K-edge XAS spectra for Ir-RuO2 and Com. RuO2. g, h Normalized Ir L3-edge XANES (g) and FT-L3-edge EXAFS (h) spectra of Ir-RuO2, with Ir foil and Com. IrO2 used as reference material. i, j k3-weighted WT-EXAFS contour plot for (i) Ir-RuO2 and (j) Ir foil. R represents the distance from the central atom and K is the wavelength of the oscillation.

Electrocatalytic performance of Ir-RuO2 towards acidic OER

The oxygen evolution performance of Ir-RuO2 was tested using linear sweep voltammetry in 0.5 M H2SO4 (see details in Electrochemical OER Measurements). For meaningful comparison, the OER activities of Ir-RuO2, Com. RuO2 and Com. IrO2 were tested under identical conditions. Figure 2a shows the polarization curves of these catalysts for acidic OER. In the OER region, Ir-RuO2 shows a sharply increasing anodic current with smaller applied voltages compared to Com. RuO2 and Com. IrO2. Impressively, the overpotential to deliver 10 mA cm−2 (η10) is only 167 mV, outperforming the Com. RuO2 (η10 = 285 mV) and Com. IrO2 reference catalysts (η10 = 310 mV). The high OER activity of Ir-RuO2 is still maintained with increasing current density. In detail, the overpotential for Ir-RuO2 necessary to reach 100 mA cm−2 was only 230 mV, which is lower than that of Com. RuO2 and Com. IrO2. More importantly, the OER process on Ir-RuO2 can be extended to industrially-relevant current densities (Fig. 2b), with a small overpotential (η1500 = 390 mV) required to reach 1.5 A cm−2. Next, Tafel slope analyses (Fig. 2c) were used to evaluate the oxygen evolution kinetics of the catalysts. It is observed that Ir-RuO2 has the lowest Tafel slope of 48.2 mV dec−1. We note that a Tafel slope of approximately 40 mV dec−1 signifies fast kinetics for OHads deprotonation to form Oads leading to O–O bond formation during OER15,39. Figure 2d summarizes the overpotentials of the catalysts at different current densities. Compared with Com. RuO2 and Com. IrO2, Ir-RuO2 exhibited lower overpotentials over the whole current range studied, with the superior performance of Ir-RuO2 becoming more evident at high current densities. These results demonstrate that Ir-RuO2 has great application potential for industrial PEMWE applications. Furthermore, EIS (Supplementary Fig. 10) was performed to evaluate the interfacial charge transfer resistance of Ir-RuO2, where a smaller value was observed for Ir-RuO2 than those of Com. RuO2 and Com. IrO2, thus providing evidence for a much faster electron transfer and mass diffusion during OER on Ir-RuO2. We further calculated the electrochemically specific surface area (ECSA) of each electrocatalyst. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 11, Ir-RuO2 exhibited a higher ECSA for the OER compared to the two commercial electrocatalysts, suggesting that the Ir-RuO2 catalyst has more active sites for OER. Moreover, Ir-RuO2 also delivered a superior turnover frequency (TOF) value normalized to the number of metal sites per geometric area and higher mass activity compared to the benchmark catalysts (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13, and Table 2), providing evidence for the superior intrinsic activity of Ir-RuO2. We note that the TOF value and mass activity calculated here are based on the total metal sites in Ir-RuO2 (including inactive Ru–O–Ru sites), so that we can infer that the Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces have high activity for OER. Furthermore, we also prepared Ir-RuO2 catalysts with different Ir contents using a similar synthesis process (see details in Methods). As shown in Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15, construction of Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces can effectively regulate the intrinsic activity of RuO2 for acidic OER, where a volcanic OER activity curve can be observed. In addition, we further measured the Faradaic efficiency (FE) of acidic OER using the drainage gas gathering method. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 16, an FE of ~100% was obtained for Ir-RuO2 during continuous testing at 100 mA cm−2, verifying its efficient OER performance. In summary, the Ir-RuO2 catalyst demonstrates good OER activity at both low and high current densities compared to those of the reference catalysts (Com. RuO2 and Com. IrO2) and outperforms most high-performance Ru/Ir-based OER catalysts (Supplementary Table 3).

a Representative LSV curves for Ir-RuO2, Com. RuO2 and Com. IrO2 in 0.5 M H2SO4. b LSV curve of Ir-RuO2 for acidic OER at high current density. c Corresponding Tafel slopes derived from (a). d Overpotentials to reach 10, 100, 500, and 1000 mA cm−2. e Chronopotentiometric curves for Ir-RuO2 during acidic OER, showing superior stability compared to Com. RuO2 and Com. IrO2. The voltages were not iR compensated. The inset in (e) is a photograph of a homemade H-type cell, with photographs displaying the uniformity and intensity of bubble generation at 10 and 100 mA cm−2, respectively, for the Ir-RuO2 catalyst on working electrodes. IrO2. f–h Steady-state OER polarization curves for Ir-RuO2 (f), Com. RuO2 (g) and Com. IrO2 (h) before and after accelerated voltammetric cycling. i Dependence of Ru and Ir dissolution in the electrolyte on the OER reaction time at 100 mA cm−2. j Chronopotentiometric curve @ 1.0 A cm−2 of the PEM electrolyzer operated at 80 °C for 300 h. The insets in (j) are the polarization curve and schematic illustration of the PEM electrolyzer using Ir-RuO2 as the anode electrocatalyst, respectively.

To explore the acidic stability of Ir-RuO2, systematic stability evaluations were performed. Figure 2e shows the chronopotentiometric (CP) responses of Ir-RuO2, Com. RuO2 and Com. IrO2 catalysts in a homemade H-type cell at room temperature. Com. RuO2 and Com. IrO2 experienced rapid activity loss in acidic media, particularly at a relatively high current density. The Com. RuO2 electrocatalyst showed the worst OER tolerance under acidic conditions, as evidenced by only 30 h of stability at 10 mA cm−2 and a sharp voltage increase at 100 mA cm−2 within 2 h. This activity degeneration was due to surface Ru atom dissolution. Com. IrO2 shows a relatively stable CP curve (achieving 72 h of stability) at 10 mA cm−2. However, a similar activity decay (after approximately 5 h) to that of Com. RuO2 can be observed at 100 mA cm−2, even though IrO2 is considered to be an acid-resistant catalyst. By contrast, Ir-RuO2 showed greatly improved OER stability, with stable operation for 1023 and 255 h at 10 and 100 mA cm−2, respectively (see Supplementary Movies 1, 2). It should be also noted that the Ir-RuO2 catalyst showed long-term OER stability above 1.46 V, which is commonly reported as the potential limit for RuO2-based catalysts in acidic media15,40,41. Ir-RuO2 shows a greatly extended stability window in the high voltage direction which exceeded those of the most recently reported Ru/Ir-based acidic OER catalysts (Supplementary Table 3). The outstanding stability of Ir-RuO2 was further verified by accelerated voltammetric cycling, as shown in Fig. 2f. Negligible degradation was observed for Ir-RuO2 even after 200,000 cycles. By contrast, the Com. RuO2 and Com. IrO2 electrocatalysts showed continuous activity degeneration after only 10,000 and 20,000 cycles (Fig. 2g, h), in agreement with the CP test results and further confirming the good durability of the Ir-RuO2 catalyst. To reveal the source of the difference in stability, we studied metal dissolution (based on the ICP-MS results) from the catalysts at 100 mA cm−2, due to the large differences in stability observed for the three catalysts under this current density. As shown in Fig. 2i, both Com. RuO2 and Com. IrO2 experienced severe metal loss and thus rapid activity degradation. By contrast, only weak metal dissolution was found for Ir-RuO2 with a high S-number of 2.0 × 104 (Supplementary Table 4). Moreover, we also measured the mass loss of the electrode (Ir-RuO2 coated carbon paper) during continuous long-term operation, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 17 and Table 5. The electrode clearly lost only tiny amounts of Ru to dissolution, with an average loss of only 0.30 μg cmgeo−2 h−1 after 200 h of operation. These results strongly suggest that the Ru–O–Ir atomic interface is robust during acidic OER operation, thus ensuring the outstanding stability of the catalyst. Furthermore, the oxidation behavior of the Ru sites was analyzed by cyclic voltammetry (CV) to reveal the origin of the good stability of Ir-RuO2 for acidic OER. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 18, Com. RuO2 exhibits two sets of redox peaks near 0.60 and 1.25 V, which can be readily attributed to Ru3+/Ru4+ and Ru4+/Ru6+, respectively42. After Ir doping, Ir-RuO2 exhibited a distinct increase in the Ru3+/Ru4+ signal area, indicating that the oxidation state of Ru in Ir-RuO2 varies between +3 and +4 during the OER process. Furthermore, the peaks assigned to Ru4+/Ru6+ disappeared after Ir was doped into RuO2, indicating that Ir doping optimized the electronic environment and effectively suppressed the overoxidation of the Ru sites responsible for metal dissolution. Therefore, construction of the Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces can effectively stabilize the catalyst structure and enhance its OER activity in acidic solutions.

To better understand the structural evolution of the Ir-RuO2 catalyst during acidic OER, further catalyst characterization data were collected after a stability test carried out for 1023 h. The XRD pattern and Raman spectra revealed that the Ir-RuO2 catalyst still retained a rutile structure without any impurities, but showed some broadening of the peaks (Supplementary Fig. 19), suggesting that a small amount of metal dissociation occurred on the catalyst surface after long acidic OER testing. The core-level Ir 4f, and Ru 3d XPS spectra (Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21) revealed that the concentration of the Ir3+ and Ru3+ species on the Ir-RuO2 surface decreased slightly, implying that more high-valent Ir4+ and Ru4+ were formed within the oxidation voltage window43,44,45. The AC-HAADF-STEM image (Supplementary Figs. 22 and 23) further verified that the original morphology of Ir-RuO2 was preserved during OER, as well as the uniform distribution of Ru, Ir and O. The Ru K/Ir L3-edge FT-EXAFS spectra of Ir-RuO2 after OER (Supplementary Fig. 24) further suggested that the local bonding structure of Ru–O–Ir was well maintained, which was also verified by the magnified AC-HAADF-STEM image (Supplementary Fig. 25), suggesting a robust Ru–O–Ir atomic interface and thus ensuring OER stability. Encouraged by the high OER performance of Ir-RuO2, a simple PEMWE device was assembled using the catalyst as the anode (Fig. 2j). As expected, the Ir-RuO2 catalyst also exhibited a high PEM performance. Specifically, only 1.6 and 1.8 V are required for the current densities of 1.0 and 2.0 A cm−2, respectively. Moreover, the Ir-RuO2 catalyst also showed good stability and the PEMWE device can operate steadily for 300 h at 1.0 A cm−2 without significant degradation. Therefore, the high performance of the PEM electrolyzer based on Ir-RuO2 further demonstrates its large application potential.

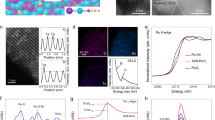

Operando spectroelectrochemical measurements and OER mechanism

To reveal the origin of the good activity of the Ir-RuO2 electrocatalyst, we performed operando ATR-SEIRAS IR and DEMS analyses to identify the intermediate species generated on the electrocatalyst surface and gaseous oxygen products during the OER process (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Figs. 26, and 27). Figure 3b shows the operando ATR-SEIRAS IR spectra of Ir-RuO2 as a function of the applied step voltage. When the bias potential reached the OER region, several obvious absorption peaks located at 1053, 1200, and 3300 cm−1 appeared. Similar spectral changes were observed for Com. RuO2 (Fig. 3c) as the voltage increased, except for the absence of the absorption peak located at 1053 cm−1. The absorption peaks located at ~1200 and 3300 cm−1 are ascribed to the *OOH and *OH intermediates formed during an AEM reaction pathway, while the additional absorption peak at 1053 cm−1 observed for Ir-RuO2 is attributed to hydrogen bonding-linked *OOH with adjacent sites, which can affect the frequency of molecular vibration27,46,47 (Supplementary Table 6). Notably, the intensity of the absorption peak at 1053 cm−1 increased for Ir-RuO2 as the applied potential increased, implying a stronger interaction between the Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces and the *OOH intermediates. In view of the changed intermediate structure after Ir doping, the OBRI site around the Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces was considered to be a potential proton acceptor that accelerates the deprotonation of *OOH at the adjacent RuCUS site, thus breaking the adsorption-dissociation linear relationship. Isotope-labelled operando DEMS measurements were further conducted to elucidate the OER pathway on Ir-RuO2, where the gaseous O2 products were collected and analyzed using gas chromatography. Specifically, Ir-RuO2 was first 18O-labelled through multiple LSV cycles (1.1–1.5 V versus RHE) in H218O electrolyte (0.5 M H2SO4), and 32O2, 34O2 and 36O2 signals were detected every cycle (Supplementary Fig. 28). Then, the 18O-labelled Ir-RuO2 was thoroughly washed with H216O deionized water, followed by four LSVs in the H216O electrolyte. If Ir-RuO2 followed an LOM, exchange between the 18O adsorbates and the lattice oxygen (Olat) will occur on Ir-RuO2 during the above-described 18O-labelling process, which would lead to the formation of 34O2 or 36O2 products during the test in the H216O electrolyte via two pathways: (i) combination one 8Olat and one 16O adsorbate, or (ii) direct coupling between two 18Olat (Supplementary Fig. 29). Indeed, as expected, the DEMS results was in good agreement our prediction, as depicted in Fig. 3d, e. When the voltage reached the OER region, the signals of the 32O2 and 34O2 products were detected without 36O2, and it should also be noted that the intensity ratio of the 34O2/32O2 signals was as low as ~0.2% in the OER region (Fig. 3f), which is close to the natural isotopic abundance of 18O in water4,31; this indicates that the LOM was absent and that Olat was not directly involved in forming O2 molecules for Ir-RuO2. These results are consistent with the ATR-SEIRAS IR findings, further confirming the role of OBRI as a proton acceptor during O2 evolution on Ir-RuO2. Furthermore, operando EIS tests were carried out within the OER potential region to explore the dynamic interfacial evolution of Ir-RuO2. It is observed from the Bode plot (Fig. 3g) that with increasing bias, a nonuniform distribution of surface charge appears on Ir-RuO2, where a small phase angle in the low-frequency region corresponds to faster OER kinetics. Notably, Ir-RuO2 has a narrower transition phase peak interval of 1.35–1.5 V than Com. RuO2 (1.35–1.6 V), as shown in Fig. 3h. For Ir-RuO2, the rapid charge dissipation and high efficiency of the oxidized charge induce an increase in the OER rate accompanied by fast surface deprotonation coupled with the electron-transfer process. Combining the operando ATR-SEIRAS IR, DEMS and EIS results, we propose a bridging oxygen-mediated deprotonation (BOMD) pathway at the Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces to rationalize the extraordinary OER activity of Ir-RuO2 above the thermodynamic limit of the AEM, as schematically depicted in Fig. 3i and Supplementary Fig. 30. First, the 4e− OER on the Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces is initiated by H2O dissociation to *OH. Next, the OBRI serves as a proton acceptor and facilitates proton transfer on the adjacent Ru centres to form *O. Subsequently, a second H2O molecule is adsorbed on the Ru site followed by a proton-coupled electron transfer step to form OOH*. Then, a proton is transferred from the OOH* intermediate to the adjacent OBRI to form *O2. Finally, *O2 is desorbed from the surface. In this mechanism, OBRI plays a critical role in the deprotonation of oxygen-containing intermediates, avoiding the traditional adsorption-dissociation linear relationship at single Ru sites and thus enhancing the OER activity.

a Schematic illustration of the OER mechanism determined by operando ATR-SEIRAS IR and DEMS analyses of the Ir-RuO2 catalyst. b, c Operando ATR-SEIRAS IR analyses of Ir-RuO2 (b) and Com. RuO2 (c) during acidic OER. d Operando DEMS signals of the generated 32O2, 34O2, and 36O2 versus time when performing LSV tests in H216O electrolyte (d) for Ir-RuO2 (18O-labelled Ir-RuO2 as the catalyst) from 1.10 to 1.50 V versus RHE. e Detailed comparison between the 32O2, 34O2, and 36O2 signals for the experiment in (d). f Ratios of 34O2:32O2, and 36O2:32O2 from (e). g, h Operando EIS spectra of measured Ir-RuO2 (g) and Com. RuO2 (h) from 1.35 to 1.60 V versus RHE. i Proposed BOMD pathway for Ir-RuO2 under acidic conditions.

DFT calculations were carried out to elucidate the influence of Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces on OER activity. The Ir atoms were incorporated into optimized RuO2 (110) surfaces because the (110) facets were predicted to be the most stable surface in our RuO2 catalyst annealed at 350 °C (Supplementary Fig. 31)4,17. It was found that Ir atoms were more stable at the fully coordinated Ru (RuBRI) sites than at the coordinatively unsaturated Ru positions (Rucus), and the Rucus position with a coordination number of 5 was considered the active site of the Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces for OER (Supplementary data 1 and 2). First, we studied the electronic structures of RuO2 and Ir-RuO2 via partial density of states (PDOS) and charge density difference analyses. As shown in Fig. 4a, b, compared with that of pure RuO2, there is a large amount of charge rearrangement around Ir atoms in Ir-RuO2, which alters the electronic structure of the adjacent active RuCUS sites. The altered electronic structure is responsible for the enhanced catalytic activity of Ir-RuO2 relative to that of RuO2. The results of PDOS analyses of Ir-RuO2 and RuO2 (Fig. 4c, d) also indicate that the incorporation of Ir species creates new hybridized electronic states in Ir-RuO2, expanding the energy range to 5–6 eV (marked by yellow rectangles) compared with that of RuO2. Moreover, the 4d orbital of the Ru atom (shifting from εd = 1.274 to 1.218 eV) and the 2p orbital of the O atom (shifting from εp = −3.23 to −3.19 eV) in Ir-RuO2 are closer to the Fermi level, suggesting that the incorporation of Ir sites increases the d-electron density of surface Ru atoms. Therefore, the effective charge concentration on the surface of Ir-RuO2 contributed to its enhanced reactivity by regulating the evolution and adsorption strength of the reaction intermediates. To understand the OER mechanism on Ir-RuO2, theoretical investigations were performed. Figure 4e illustrates the proposed BOMD pathway in detail, where the lattice oxygen bridged to Ir sites (i.e., Ru–O–Ir interfaces) acts as a proton acceptor to promote the deprotonation of oxygen-containing intermediates (OH* and OOH*) and the formation of oxygen molecules on the adjacent Ru centre. Furthermore, the energy profiles for each elemental step during OER based on the AEM, LOM, and BOMD were calculated and compared, with the results plotted in Fig. 4f and Supplementary Figs. 32–34. For Ir-RuO2, the rate-determining step (RDS) in the BOMD pathway was only 1.64 eV, which was smaller than those in the AEM (1.92 eV) and LOM (2.09 eV), as shown in Fig. 4g. Moreover, an AEM pathway was also modelled for RuO2 and the required energies (RDS: 2.11 eV) were higher than those of Ir-RuO2 via the BOMD pathway (Supplementary Fig. 35). The low reaction energy barrier of the BOMD pathway is clearly advantageous with respect to AEM and LOM, explaining the very high OER activity of Ir-RuO2. In addition, the DFT results also explain the good stability of Ir-RuO2. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 36, the energies for Ru demetallization (i.e., creation of a Ru vacancy), and oxygen vacancy formation increased after the Ru–O–Ir atomic interface was constructed in RuO2, suggesting that Ir-RuO2 would offer better stability during OER, which is in good agreement with our ICP-MS results (Fig. 2f) and the high reaction energy of LOM compared to BOMD. In summary, the theoretical investigations demonstrate that the dual site-type OER is more favorable for Ir-RuO2 and has a small energy barrier, in full agreement with our experimental observations.

a, b Charge density difference plots and corresponding electron transfer data analyzed via Bader charge calculations. Cyan and yellow correspond to the depletion and charge accumulation regions in actual space, respectively. IrBRI represents the fully coordinated Ir site. c, d PDOS plots for Ir-RuO2 and RuO2. e Schematic showing the evolution of the key O-containing intermediates for the proposed BOMD process on the Ir-RuO2 (110) surface. The Ru, Ir, O, and H atoms correspond to gray, blue, red, and white spheres, respectively. e1 and e2 represent the bridging oxygen-mediated deprotonation processes during OER. f ∆G diagrams for OER via BOMD pathways on Ir-RuO2 at U = 0 V versus RHE. * represents the active site. g Comparison of the ∆G of the RDS based on AEM, LOM, and BOMD.

Discussion

In summary, we reported that Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces within a RuO2 matrix allow highly active and acid-stable OER electrocatalysis. An overpotential of only 167 mV was achieved for Ir-RuO2 to drive the OER at 10 mA cm−2, with low overpotentials (390 mV) at a high current density of up to 1500 mA cm−2. Furthermore, Ir-RuO2 can operate stably for 1023 and 255 h at 10 and 100 mA cm−2 in acidic electrolytes, respectively. The assembled PEMWE also exhibited a stable operation for 300 h at 1.0 A cm−2. Operando ATR-SEIRAS FTIR and DEMS measurements together with theoretical investigations revealed that a bridging oxygen-mediated deprotonation process occurs at Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces, with the modified electronic structure regulating the evolution of reaction intermediates. Moreover, operando EIS tests confirmed that the Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces increased the mobility of protons on the catalyst surface, enabling a fast reaction kinetics and thus breaking the traditional scaling relationships between the key *OOH and *OH oxygen intermediates. The construction of the Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces also suppressed the dissolution of Ru atoms and the formation of oxygen vacancies during OER, thus endowing Ir-RuO2 with remarkable stability for acidic OER over a wide range of current densities. Consequently, both high OER activity and stability (and state-of-the-art overall performance) were realized at the Ru–O–Ir atomic interfaces.

Methods

Materials

All chemicals were purchased directly from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. The IrCl3·xH2O, RuCl3·3H2O, Water−18O (H218O), Com. RuO2 (99.95%) and IrO2 (99.95%) were purchased from Adamas Reagent (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. The 5 wt% Nafion® ionomer was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. The Com. Pt/C (40 wt% Pt), titanium felt and carbon paper were purchased from Suzhou Sinero Technology Co., Ltd. The Nafion 115 membrane and Nafion 117 membrane were purchased from DuPont Co.

Synthesis of Ir-RuO2

The Ir-RuO2 electrocatalyst was synthesized via a thermal-driven cation exchange strategy. First, an aqueous solution consisting of 0.05 g IrCl3·xH2O (Ir > 52 wt.%) and 0.30 g RuCl3·3H2O was transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave. After heat treatment at 200 °C for 8 h, the obtained precipitate was washed several times and then dried. The collected powders were calcined in air at 350 °C for 4 h. The product obtained is denoted as Ir-RuO2. The Ir-RuO2 powders with different Ir contents were prepared using a similar synthesis process, with changes only in changing the mass proportion of metal salts.

Characterization

Wide-angle powder XRD data were collected using a Rigaku MiniFlex600 instrument equipped with a Cu Kα X-ray source. HAADF-STEM and bright field images were collected using an aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope (USA) at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV, which was also equipped with a Gatan Enfina electron energy-loss spectrometer and a Gatan EDAX energy-dispersive X-ray system. XPS analyses were performed using a Kratos AXIS Ultra DLD spectrometer. The Ru and Ir loadings in the samples were determined by ICP-OES (Agilent 5110). The contents of the dissolved metal in the electrolyte were determined by ICP-MS (Agilent 7800). XAS measurements were conducted at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. The transmission mode was used and the X-ray photon energy was controlled via a Si(111) double-crystal monochromator. The energy calibration was conducted using an Ir/Ru foil. Background normalization/subtraction routines were carried out using the Athena software.

Electrochemical OER measurements

Acidic OER tests on Ir-RuO2 and other reference electrocatalysts were performed in a 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte at room temperature. The concentrated sulfuric acid (98%) and deionized water were used to prepare the electrolyte (0.5 M H2SO4). Note that pouring water into concentrated sulfuric acid is not allowed. The pH of the electrolyte is 0.3 ± 0.01. A three-electrode cell was adopted, where a catalyst-modified carbon paper (area 0.25 cm2), a graphite rod and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) were used as the working electrode, the counter electrode and the reference electrode, respectively. All electrochemical tests were conducted on an electrochemical workstation (CHI660E, Shanghai, China). To prepare the working electrodes, dispersions consisting of electrocatalyst (5 mg), Nafion solution (5 wt.%, 20 μL) and deionized water (480 μL) were prepared. After ultrasonic treatment, the homogeneous electrocatalyst ink (25 μL) was applied to pretreated carbon paper (prior to use, the carbon paper was treated with sulfuric acid (98 wt%) at 80 °C for 1 h), after which the resulting modified carbon paper electrodes were allowed to dry naturally in air. The catalyst loading was close to 1.0 mgcatalyst cm−2 on carbon paper. The overpotential against the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) can be obtained via the equation:

where ERHE and EθSCE are potentials versus RHE, with EθSCE = 0.241 V. The SCE electrode was calibrated under an H2 atmosphere using a Pt wire as the working electrode46. The OER performance of Ir-RuO2 and other reference electrocatalysts were tested under the same conditions to allow meaningful comparison of their intrinsic catalyst activity and stability. Polarization curves were obtained from linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) measurements to obtain polarization curves. The voltage range is 1.1–1.7 V versus RHE and the sweep rate is 5 mV s–1. The 95% iR compensation was conducted, where R is the uncompensated resistance as determined at an open circuit voltage. EIS was performed in the frequency range of 0.1–100 KHz. The electrochemically active surface area (ECSA) for all electrocatalysts was estimated according to the following Eq. (2):

where Cdl was measured from the scan-rate-dependent CVs in the non-Faradaic region of 1.041–1.141 V versus RHE in 0.5 M H2SO4 with the scan rate of 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 45 mV s−1. The specific capacitance (CS) of 0.04 mF cm−2 was used.

The long-term stability of Ir-RuO2 during OER at different current densities was evaluated in a homemade H-type electrolytic cell, where a Nafion 117 membrane was used. The chronoamperometry and chronopotentiometric tests were performed without iR compensation.

PEMWE measurement

A PEM device was assembled using an Ir-RuO2 catalyst and Com. Pt/C (40 wt%) as anode and cathode electrocatalysts, respectively. Uniform anode and cathode ink (including catalyst, distilled water, isopropanol and Nafion 115 solution (5 wt%)) were obtained after ultrasonication and then sprayed directly onto titanium felt and carbon paper (2*2 cm2), respectively. The catalyst loading was close to 3.0 mgcatalyst cm−2. A Nafion 115 membrane was used. The Nafion 115 membrane was pre-treated with dilute hydrogen peroxide and sulfuric acid before use to remove contaminants on the surface, respectively. The PEM performance of the catalysts was measured at 80 °C with distilled water as the electrolyte. The performance of the assembled PEMWE device was evaluated using an Autolab electrochemical workstation configured with BOOSTER10A.

Operando ATR-SEIRAS IR measurements

Operando attenuated total reflection surface-enhanced infrared spectroscopy (ATR-SEIRAS IR) data were recorded using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer equipped with a Pike Technologies VeeMAX III ATR accessory and an MCT detector (Nicolet IS50, Thermo Fisher Scientific Co., Ltd). The electrochemical experiment was performed using an H-type cell, where an Au-coated Si prism, Ag/AgCl electrode and Pt foil were used as the working electrode, reference electrode and counter electrode, respectively. The pre-prepared electrocatalyst ink was cast on a Au-coated Si prism for operando measurements. Prior to formal ATR-SEIRAS IR measurements, a potential was applied to the as-constructed working electrode for a period of time until reliable signals were obtained. Background curves were collected under open circuit conditions. All ATR-SEIRAS IR spectra were recorded under the resolution of 4 cm–1.

Operando DEMS measurement with isotope labelling

Operando DEMS experiments were conducted using a QAS 100 (Linglu instruments) instrument equipped with a differential electrochemical mass spectrometer, with a high and mild vacuum environment in the first and second chambers, respectively. For the measurements, a typical three-electrode cell was used with the anode chamber directly linked to the mass spectrometer. The O2 generated from the electrolyte (0.5 M H2SO4) during the OER entered the first vacuum chamber of the mass spectrometer for further analysis. For the isotope labelling investigations, a 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte was prepared using H218O as the solvent, in which the working electrode consisted of electrocatalysts coated onto an Au film that was subjected to LSV cycles to label the electrocatalyst with 18O at a voltage of 1.1–1.5 V versus RHE. Then, the 18O-labelled working electrode was rinsed with H216O several times and dried to remove any physically adsorbed H218O. Finally, LSV cycles were applied to the 18O-labelled working electrode in a 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte with H216O acting as the solvent, with the gaseous products evolved at the anode detected by mass spectrometry.

Note that prior to all DEMS experiments, high-purity N2 was purged into the electrolyte for 30 min to eliminate any possible contributions from dissolved oxygen. Moreover, the working electrode without isotope labelling was subjected to similar LSV cycles in 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte using H216O as the solvent to evaluate the natural abundance of 18O in the electrolyte.

Computational details

We used the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP 5.4.4) to conduct all DFT calculations. To describe the exchange-correlation energy, the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof Generalized Gradient Approximation function was applied. Moreover, a projector-augmented wave with a kinetic energy cut-off of 500 eV, was used to expand the electronic eigenfunctions. The force convergence threshold and total energy were set to 0.02 eV Å−1 and 10−4 eV, respectively. Van der Waals interactions were modelled using the empirical correction of the DFT + D3 scheme and the Brillouin zone was sampled with a 2 × 2 × 1 Monkhorst-Park k-point grid.

Gibbs free energy changes (ΔG) of every electrochemical elementary reaction were estimated according to the following equation, where the theoretical hydrogen electrode model was employed for modelling OER (3):

where ΔEZPE is the difference in zero-point energy at 298.15 K between the products and the reactants, which can be calculated from vibrational frequencies. The values of ΔE were obtained from the total energies. The effects of the electrode pH and applied voltage were corrected using the ΔGpH and ΔGU terms, respectively. ΔS is the value of entropy and is obtained in a similar manner to ΔEZPE; The vibrational frequencies of free molecules and entropy values were obtained from the NIST database.

Data availability

All the data supporting this study can be available in the article and the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Chu, S. & Majumdar, A. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 488, 294–303 (2012).

Chang, J. et al. Synthesis of ultrahigh-metal-density single-atom catalysts via metal sulfide-mediated atomic trapping. Nat. Synth. 3, 1427–1438 (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. Long‐term stability challenges and opportunities in acidic oxygen evolution electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202216645 (2023).

Wu, Z.-Y. et al. Non-iridium-based electrocatalyst for durable acidic oxygen evolution reaction in proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. Nat. Mater. 22, 100–108 (2023).

Lin, Y., Dong, Y., Wang, X. & Chen, L. Electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media. Adv. Mater. 35, 2210565 (2023).

Spöri, C., Kwan, J. T. H., Bonakdarpour, A., Wilkinson, D. P. & Strasser, P. The stability challenges of oxygen evolving catalysts: towards a common fundamental understanding and mitigation of catalyst degradation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 5994–6021 (2017).

Chen, F.-Y., Wu, Z.-Y., Adler, Z. & Wang, H. Stability challenges of electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction: From mechanistic understanding to reactor design. Joule 5, 1704–1731 (2021).

Du, K. et al. Interface engineering breaks both stability and activity limits of RuO2 for sustainable water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 13, 5448 (2022).

Chang, J. et al. Oxygen radical coupling on short-range ordered Ru atom arrays enables exceptional activity and stability for acidic water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 12958–12968 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Exceptionally active and stable RuO2 with interstitial carbon for water oxidation in acid. Chem 8, 1673–1687 (2022).

Wu, H., Huang, Q., Shi, Y., Chang, J. & Lu, S. Electrocatalytic water splitting: mechanism and electrocatalyst design. Nano Res. 16, 9142–9157 (2023).

Shi, Y., Wu, H., Chang, J., Tang, Z. & Lu, S. Progress on the mechanisms of Ru-based electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media. J. Energy Chem. 85, 220–238 (2023).

Yan, H., Jiang, Z., Deng, B., Wang, Y. & Jiang, Z. J. Ultrathin carbon coating and defect engineering promote RuO2 as an efficient catalyst for acidic oxygen evolution reaction with super‐high durability. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2300152 (2023).

Dickens, C. F. & Nørskov, J. K. A theoretical investigation into the role of surface defects for oxygen evolution on RuO2. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 18516–18524 (2017).

Zhang, D. et al. Construction of Zn-doped RuO2 nanowires for efficient and stable water oxidation in acidic media. Nat. Commun. 14, 2517 (2023).

Shah, K. et al. Cobalt single atom incorporated in ruthenium oxide sphere: a robust bifunctional electrocatalyst for HER and OER. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 134, e202114951 (2022).

Wen, Y. et al. Stabilizing highly active Ru sites by suppressing lattice oxygen participation in acidic water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 6482–6490 (2021).

Laha, S. et al. Ruthenium oxide nanosheets for enhanced oxygen evolution catalysis in acidic medium. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1803795 (2019).

Zhao, Z. L. et al. Boosting the oxygen evolution reaction using defect-rich ultra-thin ruthenium oxide nanosheets in acidic media. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 5143–5151 (2020).

Cui, X. et al. Robust interface ru centers for high-performance acidic oxygen evolution. Adv. Mater. 32, 1908126 (2020).

Qin, Y. et al. RuO2 electronic structure and lattice strain dual engineering for enhanced acidic oxygen evolution reaction performance. Nat. Commun. 13, 3784 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Strain‐modulated Ru‐O covalency in Ru‐Sn oxide enabling efficient and stable water oxidation in acidic solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202316029 (2024).

Hubert, M. A. et al. Acidic oxygen evolution reaction activity–stability relationships in ru-based pyrochlores. ACS Catal. 10, 12182–12196 (2020).

Hao, S. et al. Dopants fixation of Ruthenium for boosting acidic oxygen evolution stability and activity. Nat. Commun. 11, 5368 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Breaking the Ru‐O‐Ru symmetry of a RuO2 catalyst for sustainable acidic water oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202316903 (2023).

Shi, Z. et al. Customized reaction route for ruthenium oxide towards stabilized water oxidation in high-performance PEM electrolyzers. Nat. Commun. 14, 843 (2023).

Hao, Y. et al. Switching the oxygen evolution mechanism on atomically dispersed ru for enhanced acidic reaction kinetics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 23659–23669 (2023).

Hu, C. et al. Misoriented high-entropy iridium ruthenium oxide for acidic water splitting. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf9144 (2023).

Lin, Y. et al. Chromium-ruthenium oxide solid solution electrocatalyst for highly efficient oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media. Nat. Commun. 10, 162 (2019).

Rong, C., Dastafkan, K., Wang, Y. & Zhao, C. Breaking the activity and stability bottlenecks of electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reactions in acids. Adv. Mater. 35, 2211884 (2023).

Shi, Z. et al. Confined Ir single sites with triggered lattice oxygen redox: toward boosted and sustained water oxidation catalysis. Joule 5, 2164–2176 (2021).

Song, H. et al. RuO2–CeO2 lattice matching strategy enables robust water oxidation electrocatalysis in acidic media via two distinct oxygen evolution mechanisms. ACS Catal. 14, 3298–3307 (2024).

Zhao, F. et al. Increasing iridium oxide activity for the oxygen evolution reaction with hafnium modification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 15616–15623 (2021).

Lee, K. et al. Modulating the valence electronic structure using earth-abundant aluminum for high-performance acidic oxygen evolution reaction. Chem 9, 3600–3612 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Inverse doping IrOx/Ti with weakened Ir-O interaction toward stable and efficient acidic oxygen evolution. Chem 9, 2931–2942 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Single-site Pt-doped RuO2 hollow nanospheres with interstitial C for high-performance acidic overall water splitting. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl9271 (2022).

Frati, F., Hunault, M. O. & De Groot, F. M. Oxygen K-edge X-ray absorption spectra. Chem. Rev. 120, 4056–4110 (2020).

Zhang, N. & Chai, Y. Lattice oxygen redox chemistry in solid-state electrocatalysts for water oxidation. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 4647–4671 (2021).

An, L. et al. Recent development of oxygen evolution electrocatalysts in acidic environment. Adv. Mater. 33, 2006328 (2021).

McCrory, C. C. et al. Benchmarking hydrogen evolving reaction and oxygen evolving reaction electrocatalysts for solar water splitting devices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4347–4357 (2015).

Cherevko, S. et al. Oxygen and hydrogen evolution reactions on Ru, RuO2, Ir, and IrO2 thin film electrodes in acidic and alkaline electrolytes: a comparative study on activity and stability. Catal. Today 262, 170–180 (2016).

Liu, H. et al. Eliminating over-oxidation of ruthenium oxides by niobium for highly stable electrocatalytic oxygen evolution in acidic media. Joule 7, 558–573 (2023).

Jin, H. et al. Dynamic rhenium dopant boosts ruthenium oxide for durable oxygen evolution. Nat. Commun. 14, 354 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Rare-earth-regulated Ru-O interaction within the pyrochlore ruthenate for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution in acidic media. Sci. China Mater. 64, 1653–1661 (2021).

Liu, H. et al. Iridium doped pyrochlore ruthenates for efficient and durable electrocatalytic oxygen evolution in acidic media. Small 18, 2202513 (2022).

Lin, C. et al. In-situ reconstructed Ru atom array on α-MnO2 with enhanced performance for acidic water oxidation. Nat. Catal. 4, 1012–1023 (2021).

Vivek, J. P., Berry, N. G., Zou, J., Nichols, R. J. & Hardwick, L. J. In situ surface-enhanced infrared spectroscopy to identify oxygen reduction products in nonaqueous metal–oxygen batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 19657–19667 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52122308, 51973200, 52202050, and 21905253), Natural Science Foundation of Henan (202300410372), Joint Fund of Science and Technology R&D Plan of Henan Province (232301420042) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022TQ0286). We also acknowledge the Center for Modern Analysis and Gene Sequencing of Zhengzhou University and the BL14W beamline of Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for supporting this project. GINW acknowledge funding support from the Royal Society Te Apārangi (James Cook Research Fellowship), the Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment (C05X2007, UOCX2118), and a philanthropic donation from Greg and Kathryn Trounson.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y.L. and J.W.C. supervised all the aspects of this research. H.W. carried out the experiment, electrocatalytic evaluations, characterizations of the as-prepared electrocatalysts, interpreted the experimental data, and wrote this paper. X.Y. and J.K.Y. performed the DFT calculations. H.W., S.Y.W., and Z.A.H. participated in the work and discussed the experimental findings. Z.Y.T., J.B.C., and G.I.N.W. revised this manuscript and provided professional suggestions for this work. All the authors participated in commenting on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Helmut Schaefer and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Chang, J., Yu, J. et al. Atomically engineered interfaces inducing bridging oxygen-mediated deprotonation for enhanced oxygen evolution in acidic conditions. Nat Commun 15, 10315 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54798-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54798-7

This article is cited by

-

A triple-defense electrocatalyst for robust seawater oxidation

Nature Communications (2025)

-

MXene-Assisted NiFe sulfides for high-performance anion exchange membrane seawater electrolysis

Nature Communications (2025)

-

4f-modified Ru-O polarity as a descriptor for efficient electrocatalytic acidic oxygen evolution

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Engineering high-density microcrystalline boundary with V-doped RuO2 for high-performance oxygen evolution in acid

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Electronic tuning of RuO₂ polarizes metal–oxygen redox for proton exchange membrane water electrolysis

Nature Communications (2025)