Abstract

Supramolecular nanoreactor as artificial mimetic enzyme is attracting a growing interest due to fine-tuned cavity and host-guest molecular recognition. Here, we design three 3d-4f metallo-supramolecular nanocages with different cavity sizes and active sites (Zn2Er4L14, Zn4Er6L26, and Zn2Er8L38) based on a “bimetallic cluster cutting” strategy. Three nanocages exhibit a differential catalysis for the three-component aza-Darzens reaction without another additive, and only Zn2Er8L38 with the largest cavity and the most lanthanides centers has excellent catalytic conversion for monosubstituted and disubstituted N-aryl aziridine products. The host-guest relationship investigations confirm that Zn2Er8L38 significantly outperforms Zn2Er4L14 with the smaller cavity and Zn4Er6L26 with the fewer Lewis acidic sites in multi-component reaction is mainly attributed to the synergy of inherent confinement effect and multiple Lewis acidic sites in nanocage. The “bimetallic cluster cutting” strategy for the construction of 3d−4f nanocages with large windows may represent a potential approach to develop supramolecular nanoreactor with high catalytic efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Enzymes, as natural catalysts, provide various perfect substrate-binding pockets to encapsulate special molecules and accelerate biochemical reactions, which has inspired scientists to develop artificial nanoreactors for efficient and selective catalytic reactions under ambient conditions1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Supramolecular coordination nanocages are discrete molecular architectures with well-defined shapes, sizes, and geometries9,10,11,12,13. Apart from their aesthetically pleasing structures, several artificial nanocages also can self-recognize guest molecules according to the size of the inner nano-space like enzymes, which offers a delicate approach to controlling chemical reactions beyond the bounds of the flask14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. For these molecular hosts, a variety of synthetic methods have been explored to adjust the cavity size, window shape, and intrinsic performances of supramolecular nanocages mainly via the guidance of metal knots and organic linkers, including selecting definite coordination metal ions or clusters to construct different geometry of the cage, lengthening linear linkers to enlarge cage size, utilizing rigid tripod or tetrapod ligands to establish and stabilize novel geometry of the cage, and incorporating nonpolar aromatic backbones to tune microenvironment of the cavity in a cage22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Obviously, it is undeniable that ligand-driven supramolecular coordination nanocage based on highly symmetrical ligands as well as transition metal coordination-driven nanocage is the most common strategy because it can effectively avoid the generation of unexpected isomers in the self-assembly process31,32,33. However, the construction of a stable and suitable confinement space is only an indispensable part of the mimetic enzyme, and an outstanding coordination cage-based nanoreactor should be able to provide simultaneously abundant active sites anchored in the structure of the nanocage to achieve catalytic activity for different substrate34,35. Therefore, it remains a huge challenge to combine the functional binding activity with host architecture in coordination cage chemistry36,37,38.

Notably, the nanocage models with regularity structure can enhance the confinement effect, but weaken the exploitation of catalytic sites in the inner cavity to some extent39,40,41. Moreover, the potential catalytic functions of the metal centers in the nanocage are often hindered or neglected42,43. Once excess metal ion knots with unsaturated coordination as Lewis acidic sites are embedded inside the cage, these active monometallic ions will greatly increase the number of catalytic centers for the substrates without sacrificing cavity space44,45. Lanthanide ions have large ionic radius, variable coordination numbers, and weak stereochemical preference due to inherent f orbital nature, which make them become good Lewis acidic sites in various catalytic materials. Significantly, numerous lanthanide polymetallic clusters, especially dinuclear clusters, have been synthesized in the participation of negatively charged oxygen atom due to the highly oxyphilic feature of lanthanide ions46,47,48,49,50,51. Thus, it is fairly valuable and interesting to precisely adjust the formation or disassembly of dinuclear lanthanide clusters to release and expose more Lewis acidic sites in the nanocage for Ln-catalysis.

On the other hand, aziridines with minimal saturated nitrogen heterocycles are valued as building blocks and useful precursors for the synthesis of a wide range of nitrogen-containing compounds due to their highly regio- and stereoselective ring-opening reactions, which have been synthesized widely via the aza-Darzens reaction52,53,54,55. In varieties of synthesis strategies, one-pot multicomponent aza-Darzens couplings to synthesize aziridines have exhibited an excellent atomic economy and become a rare shortcut in synthetic chemistry, even though they are seldom studied56. Toste and Lin et al. promoted a three-component aza-Darzens reaction for using a homogeneous nanovessel catalyst and heterogeneous catalyst, respectively42,57,58. Meanwhile, our investigation found that the size of the host cavity and the rational arrangements of catalytic centers in the nanocage are crucial to the multi-component reaction because of an inefficient reaction conversion for aromatic aldehydes and anilines with steric hindrance groups in the small nanocage59. Although different types of catalysts have been explored for the three-component aza-Darzens reaction, the nanocages-based catalysts still need to be optimized to surmount the longer reaction time, higher catalyst loading, use of additive, and universality of various substrates57,58,59,60.

Herein, we report a “bimetallic cluster cutting” strategy via modulating the steric hindrance and flexibility of the nonsymmetric ligand to control the formation or disassembly of the lanthanide metallic cluster. As depicted in Fig. 1, three related multidentate ligands (L1–L3) based on nonsymmetric dihydrazide have been designed and investigated. In these ligands, L1 has a smaller steric hindrance relative to L2 and L3, but L3 possesses the larger steric groups and a more flexible chain in the molecule skeleton synchronously. By self-assembly of these ligands with the mixed metal ions under the same conditions, two stable 3d-4f supramolecular nanocages with different cavity sizes and active sites, [Zn4Er6(L2)6]4+ (Zn4Er6L26) and [Zn2Er8(L3)8Cl2]2+ (Zn2Er8L38), have been synthesized, and both of them are systematically compared with the pioneer [Zn2Er4(L1)4Cl2]2+ (Zn2Er4L14) possessing the smaller size nanocage59 in structure and catalytic property. Three nanocages exhibit stepwise increased catalytic sites and growing cavity sizes as the number of lanthanide ions increased, which are synergistically and significantly affecting the three-component aza-Darzens reaction. Significantly, the nanocage Zn2Er8L38 with the largest cavity and the most erbium centers has the highest catalytic conversion (88 % yield) only in 0.5 h for monosubstituted aziridine product without another additive under mild conditions, and catalytic conversion for more complex disubstituted N-aryl aziridine product also could be achieved 81 % yield in 6 h. To the best of our knowledge, the study represents a meaningful exploration for the design and the construction of discrete 3d−4f nanocages with substrate selectivity and catalytic turnover, and the “bimetallic cluster cutting” strategy may be a potential approach to develop supramolecular nanoreactor with excellent efficiency.

Results

Designed synthesis and characterizations

Lanthanide ions with special 4f electronic configuration exhibit high coordination numbers, kinetic lability, weak stereochemical preference, and variable coordination sphere, resulting in uncontrollable and unpredictable stereo structures of lanthanide complexes61. For rare earth ions, most of them need more coordination atoms. Significantly, an acylhydrazone group linked together with phenol moiety possesses multiple N/O donor atoms, which not only could provide the stable tridentate-chelating site to fix a lanthanide ion but also could bridge easily another lanthanide ion to form a bimetallic cluster unit. The kind of lanthanide dinuclear clusters can be found in numerous lanthanide complexes48,49,50,51. Therefore, that is a huge challenge to control precisely the formation or disassembly of bimetallic cluster units. Encouragingly, with the introduction of the steric hindrance and flexibility in ligands, the bridging effect of negatively charged oxygen atom could be restrained and a lanthanide cluster could be broken down into isolated metal ions.

Guided by the lanthanide “bimetallic cluster cutting” strategy, a series of semirigid and multidentate bis-acylhydrazone ligands with nonsymmetry were designed, and their lanthanide complexes with different nanocage structures were synthesized (Fig. 1). Experimental details for the synthesis and characterization of ligands are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1–10, and all lanthanide nanocages, Zn2Er4L14, Zn4Er6L26, and Zn2Er8L38, were prepared by the self-assembly of the ligands L1-L3 with ZnCl2, Er(NO3)3 or Er(ClO4)3 in CH3OH. Yellow lump crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were obtained by evaporating slowly the solution at room temperature. Crystal data, FT-IR spectra, thermogravimetric analyses (TGA), powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), and photoluminescence spectra (PL) of these nanocages were investigated, indicating the formation of 3d-4f complex (Supplementary Table 1–3 and Supplementary Fig 11–14).

Structure description

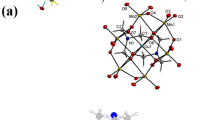

The ethoxy group at the terminal in ligand L1 has greater freedom and can provide a potential neutral ether oxygen atom to coordinate lanthanide ions. The crystal structure of the Zn2Er4L14 cage is shown in Fig. 2a, and it mainly consists of four deprotonated ligands, four Er3+ ions and two Zn2+ ions. Each Er3+ ion is first chelated by two tridentate coordination moieties, and two coordinated Er3+ units are further connected via phenol oxygen atoms to form a lanthanide-based bimetallic cluster unit. Then, two pairs of bimetallic cluster units (Er···Er distance is 3.54 Å) are connected by four ligands and two Zn2+ nodes in opposite positions to become a distorted supramolecular nanocage. The diameter of the spherical cavity is about 7.5 Å, and two elliptical open windows with a size of ∼4.8 × 7.8 Å2 are exposed outside the surface of the cavity in opposite positions (Supplementary Fig. 15 and 16).

a Molecular structure of Zn2Er4L14 nanocage (left), the lanthanide bimetallic cluster unit (middle), and the polyhedral skeleton of all metal ions (right). b Molecular structure of Zn4Er6L26 nanocage (left), a distorted molecular square composed of four independent Er coordination units and a bimetallic cluster unit (middle), the polyhedral skeleton, and spatial arrangement of all metal ions (right). c Molecular structure of Zn2Er8L38 nanocage (left), a molecular square composed of four independent Er coordination units (middle), and the polyhedral skeleton of all metal ions (right). All hydrogen atoms, solvent molecules, and uncoordinated anions are omitted for clarity. C gray, O red, N blue, Cl pale green, Er magenta, Zn cyan.

When the ethoxy group is replaced by the tert-butyl group at the ligand terminal, the steric hindrance effect can limit largely the bridging of the adjacent phenolic oxygen atom for metal ions. A view of the X-ray crystal structure of the Zn4Er6L26 cage is shown in Fig. 2b, which is crystallized in the triclinic P\(\bar{1}\) space group. Different from Zn2Er4L14, Zn4Er6L26 supramolecular cage was constructed by six deprotonated ligands, six Er3+ ions, and four Zn2+ ions. Two Er3+ ions, each of them chelated separately by a tridentate ligand, are further bridged by enolic hydroxyl oxygen atoms in ligands to form a lanthanide-based bimetallic cluster unit (Er ∙ ∙∙Er distance is 3.97 Å). However, the other four Er3+ ions are independently chelated by two multi-dentate acylhydrazone moieties from different ligands. Then, they are connected by ligands to form slightly twisted parallelogram. The distance between the adjoining independent Er3+ ions are in the range of 8.10–9.33 Å. Four coordinated Zn2+ ions as key components of metalloligands connect different ligands and strengthen the whole supramolecular frame. Thus, a lanthanide bimetallic cluster unit, four lanthanide coordination individuals, and metalloligands are gathered together to form a squished lantern-shaped cage with a spherical cavity, whose diameter is about 8.0 Å (Supplementary Fig. 17 and 18). The cage mainly possesses three irregular and wide windows, which surround the cavity and allow more molecules to pass through the cage. It is worth noting that six Er3+ ions in the Zn4Er6L26 cage are not chelated completely by ligands and retain many coordination methanol molecules, which may be wonderful and potential active sites for guest compounds.

With the introduction of ligand L3 that possesses steric hindrance groups and a more flexible chain synchronously, the supramolecular cage exhibits a more obvious change. Zn2Er8L38 is crystallized in the monoclinic P21/c space group, and consists of eight deprotonated ligands, eight Er3+ ions and two Zn2+ ions (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, every Er3+ ion is octa-coordinated by two tridentate coordination moieties that come from different ligands and two solvent molecules, and all Er3+ ions become separate coordination units. Four lanthanide complex units are connected firstly by ligands to form a distorted planar molecular square (Er···Er distances are in the range of 7.53-8.10 Å), and a pair of molecule squares are further linked via Zn2+-based metalloligands to form eventually an oblique prism-shaped and macroporous supramolecular cage (Er···Er distance is about 11.82-12.20 Å). Two Zn2+ ions, penta-coordinated by different ligands and Cl– anion, are fixed at the two poles of the cage in opposite positions, and two pairs of huge opening windows with sizes of ∼11 × 7.5 Å2 and ∼7.5 × 8.0 Å2 respectively surround the cavity, which are convenient for access of the larger guest molecules (Supplementary Fig. 19 and 20). In addition, abundant coordination solvent molecules on Er3+ ions face toward the inner channel of the cavity, indicating that these occupied molecules are easily removed from the metal ions in the catalysis and the Zn2Er8L38 cage is a great advantage in providing many potential catalytic sites inside the cavity.

1H NMR spectra of Zn2Er4L14, Zn4Er6L26 and Zn2Er8L38 cages displayed more complicated signals compared with ligands due to the existence of abundant paramagnetic Er3+ ions (Supplementary Fig. 21–23). Nevertheless, the diffusion-ordered NMR spectroscopy (DOSY) experiments exhibited the formation of different single diffusion bands with the diffusion coefficient D = 1.20 × 10−10 m2·s−1 (log D = – 9.92) for Zn2Er4L14 cage, D = 6.32 × 10−11 m2·s−1 (log D = – 10.20) for Zn4Er6L26 cage and D = 9.5 × 10−11 m2·s−1 (log D = – 10.02) for Zn2Er8L38 cage, respectively, which confirmed the existence of molecular cages in solution to a certain extent (Supplementary Fig. 24–26). Thus, the dynamic radii (r) of these cages calculated by Stokes-Einstein equation are 9.57 Å, 18.20 Å and 12.20 Å, respectively, consistent with the change of crystal structure sizes (~ 9.45 Å for Zn2Er4L14, ~16.2 Å for Zn4Er6L26, and ~12.5 Å for Zn2Er8L38).

The existence and formation of three cage-like assemblies in solution were confirmed further by high-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectra (HRESI-MS). The nanocage Zn2Er4L14 had a narrow symmetrical peak at maximum m/z = 1511.6356 with an isotopic distribution pattern separated by (0.50 ± 0.005) Da, which should belong to the positively double-charged ion of Zn2Er4L14 cage, {[Er4Zn2(L1–3H+)4Cl2]·NO3–·Cl–·H2O·5CH3OH + 2H+}2+ (calc. m/z = 1511.6360)59. As shown in Fig. 3, for nanocage Zn4Er6L26, although the HRESI-MS spectra were more complex due to dynamic dissociation-combination of the assembly in solution, the strong molecular ion peak of Zn4Er6L26 could be observed easily at m/z = 2576.6920 with an isotopic distribution pattern separated by (0.50 ± 0.005) Da attributed to the double-charged positive ion of Zn4Er6L26 cage, {[Er6Zn4(L2–4H+)3(L2–3H+)3]·3NO3–·CH3OH·2H2O}2+ (calc. m/z = 2576.6973). The other two main peaks with double-charged positive ions in the range between m/z = 2600 and m/z = 2650 could belong to molecular ions derived from host cage {[Er6Zn4(L2–4H+)6]·2NO3–·3H++solvent}2+, consistent with simulated isotope patterns (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. 27). For Zn2Er8L38 nanocage, the HRESI-MS also exhibited a symmetrical molecular ion peak at m/z = 3274.1098 with an isotopic distribution pattern separated by (0.50 ± 0.005) Da, which could be attributed to the double-charged positive ion of Zn2Er8L38 cage, {[Er8Zn2(L3–3H+)8Cl2]·CH3CN·H2O}2+ (calc. m/z = 3274.1094). The complex distribution of other ion peaks might be due to the larger supramolecular structure and the dynamic self-assembly configuration of Zn2Er8L38 cage in solution (Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Fig. 28). These cage-based ion precursors or fragments of Zn2Er8L38 cage in experimental HRESI-MS are all in good agreement with those of theoretical simulations, which provides convincing evidence for the dynamic formation and evolution of the nanoscale 3d-4f metallacages in solution.

a HRESI mass spectra of Zn4Er6L26 cage in CH3CN. Inset: Observed and simulated mass peaks at m/z = 2576 with isotopic distribution patterns separated by (0.50 ± 0.005) Da. b HRESI mass spectra of Zn2Er8L38 cage in CH3CN/CH2Cl2. Inset: Observed and simulated mass peaks at m/z = 3274 with isotopic distribution patterns separated by (0.50 ± 0.005) Da.

Catalytic properties

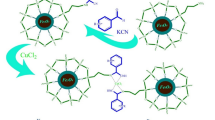

Supramolecular nanocage with rich Lewis acidic sites and large windows is beneficial to facilitate the chemical transformation and catalyze guest molecules in the cavity. Thus, these unique nanocage structures stimulated us to explore and evaluate the catalytical application of Zn2Er4L14, Zn4Er6L26, and Zn2Er8L38 as supramolecular nanoreactors for the synthesis of aziridine derivatives. The condition optimization of the three-component aza-Darzens reaction by using aniline, formaldehyde, and α-diazo ester as model substrates is summarized in Supplementary Table 6.

As shown in Fig. 4a, in the presence of 0.2 mol% Zn2Er8L38 cage and within the same reaction time, different solvents affected significantly the yield of the reaction product 4a. The acetonitrile with a weak nitrogen donor atom for three-component aza-Darzens reaction exhibited an outstanding yield (65 %) compared with that in the other solvents (17 – 60 %), and the methanol with weaker coordination ability is the second-best solvent. The solvents with the stronger coordination ability (DMSO and DMF) may inhibit the coordination and exchange process of substrates on lanthanide ion center. Then, based on systematic screening of other parameters including catalyst loading and reaction time, the best catalytic conditions for the Zn2Er8L38 cage catalyst were obtained and the yield of 4a could achieve 91 %. Given the economy of the reaction, the optimal and economical catalytic conditions of the Zn2Er8L38 cage for the three-component aza-Darzens reaction were determined (0.4 mol% nanocage catalyst in acetonitrile at room temperature for 0.5 h). Significantly, under the optimal conditions, product 4a could not be observed when the Zn2Er8L38 cage was replaced by ligand or ZnCl2 as the catalyst. The product 4a was just obtained less than 20 % yield in the absence of any catalyst and in the presence of Er(ClO4)3 or a mixture catalyst (L3, Er(ClO4)3 and ZnCl2) as catalyst.

a Optimization of solvent conditions for three-component aza-Darzens reaction in the presence of 0.2 mol% Zn2Er8L38. b The yield change of product 4a catalyzed by various cages over time. Reaction conditions: 0.5 mmol aniline, 0.6 mmol formaldehyde, 0.7 mmol α-diazo ester, 0.4 mol% catalyst. c 1H NMR monitor for the formation of the disubstituted N-aryl aziridine product 5a catalyzed by 0.2 mol% Zn2Er8L38. Reaction conditions: 0.5 mmol aniline, 1.0 mmol benzaldehyde, 0.7 mmol α-diazo ester. The changes of 1H NMR signals are showed in color regions (400 MHz, 298 K, CDCl3).

In addition, the catalysis of different nanocages for the aza-Darzens reaction showed that 4a could only obtain 46 % and 40 % yield in the presence of Zn4Er6L26 and Zn2Er4L14, respectively, but Zn2Er8L38 cage had an overwhelming catalysis advantage in yield of 4a (88 %) compared with Zn2Er4L14 and Zn4Er6L26 under the same conditions (Fig. 4b). Even prolonging reaction time, Zn2Er8L38 still exhibited the highest and most satisfactory catalytic efficiency compared with the other nanocage catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 29)57,59. These results indicated that Zn2Er8L38 cage with the largest pore size and the greatest number of Lewis acidic sites provided an excellent catalytical microenvironment to increase the intrusion of small molecule substrates into the host cage and facilitate substrate conversion for three-component aza-Darzens reaction.

Under optimal experimental conditions, the Zn2Er8L38 cage as the catalyst for aza-Darzens reactions showed a broad substrate scope and good tolerance of functional groups. As shown in Table 1, for general electron-withdrawing substituents (−F, −Cl, −Br, −I) and electron-donating substituents (−Me, −Et, −iPr, −OMe, –OEt) on the aniline para-position, there were no significant differences in aza-Darzens reaction efficiency, and the corresponding target products could be obtained in the range of 56 % to 88 % yield. When the position of the substituent was changed (m–Me, m–Et, m–iPr, m–F) and the larger steric groups were presented (o–tBu, m–tBu, p − tBu) on aniline ring, the catalytic reaction could still proceed smoothly, and the yields of most target products were greater than 80 %. Only strong electron-withdrawing substituents (p–COOH and p–NO2) inhibited the catalytic reaction and no products could be observed, which may be because their strong electron-withdrawing effect can weaken nucleophilic addition of the amine group that had been confirmed by 1H NMR and DFT calculations (Supplementary Fig. 30–32). In addition, compared to formaldehyde, the propanal could generate more complex disubstituted N-phenyl aziridine in 86 % yield catalyzed by more catalyst, where cis-aziridine was the major isomer. To verify the practicality of the catalyst Zn2Er8L38, a gram-scale experiment of the three-component aza-Darzens reaction was carried out. When aniline (0.93 g), formaldehyde (2.03 g), α-diazo ester (2.27 g), and Zn2Er8L38 (0.4 mol% for aniline) were mixed in 80 mL of acetonitrile, the isolated yield of 4a was as high as 85 % (1.62 g) in 3 h, which is the gram-scale exploration for this three-component reaction and presents great potential for application in the industrial synthesis of aziridine.

Benzaldehyde derivatives as aza-Darzens reaction substrates can afford disubstituted N-aryl aziridine derivatives, which are important ring-opening precursors for biological drugs52. Many catalysts just exhibited poor catalytic properties to form disubstituted N-aryl aziridine derivatives within finite time due to the conjugative effect of aromatic aldehyde57,59. Interestingly, Zn2Er8L38 cage could become an excellent tool to catalyze effectively aromatic aldehyde derivatives instead of formaldehyde in three- component aza-Darzens reaction in a few hours. The quantitative transformation of benzaldehyde as the substrate was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy. As shown in Fig. 4c, intermediate N-benzylideneaniline was generated rapidly by the reaction of benzaldehyde with aniline in solution, and a peak at 8.5 ppm could be easily observed. As the reaction progressed, two new peaks near 3.5 ppm were found, and product 5a (cis-aziridine as the major diastereomer) was obtained in 81 % yield under the optimal catalytic condition (0.2 mol% Zn2Er8L38 cage in acetonitrile at room temperature for 6 h) (Supplementary Table 7), which was more efficient than that of most catalysts52,58,62. As shown in Table 2, a wide range of functional groups on aniline and benzaldehyde were tolerated to afford disubstituted N-aryl aziridine products (5b-v) in good to excellent yields (55−86 %). Both electron-withdrawing substituents and electron-donating substituents could not influence dramatically the formation of target products. Some aziridine products (5k, 5 l, and 5w) could be obtained only in cis-configuration, which may be due to the feature of the substrates (electronegativity and conjugated structure) and structural feature of Zn2Er8L38 cage (cavity size and window size). However, the substrate 1-naphthaldehyde, instead of benzaldehyde, as one of the starting materials in the three-component aza-Darzens reaction only showed poor conversion (5w, 24 % yield), which might be due to its large aromatic conjugative effect and steric hindrance in the reaction.

Structure−activity relationships

To illustrate the inherent synergy between the confinement effect of the nanocage and multiple Lewis acidic sites of lanthanide ions on the cage for the three-component aza-Darzens reaction, several representative substrates with differences in molecular size and steric hindrance were selected to evaluate and analyze the catalytic capability of Zn2Er4L14, Zn4Er6L26, and Zn2Er8L38 catalysts (Supplementary Table 8). As shown in Fig. 5, Zn2Er4L14 with the smallest cavity and windows could accommodate easily and catalyze small or chain aliphatic aldehydes aniline (A and E) with small size in a lower yield (<40 %), yet a few products (< 24 %) were generated for those butylanilines (B, C, and D) and aryl aldehydes (F and G) with large steric hindrance, which could be explained preferably by the incompatible cavity of Zn2Er4L14 cage. As the cavity size of nanocages increased, the cavity and windows of Zn4Er6L26 and Zn2Er8L38 were large enough so that these larger substrate molecules (B – F) could be easily allowed to enter the nanocage, access to Lewis acidic centers, and react with the other components. However, Zn2Er8L38 exhibited more than one-third of overall yields than that of Zn4Er6L26 for these substrates, which might be due to the larger cavity size and more Lewis acidic sites of Zn2Er8L38. Remarkably, when 1-naphthaldehyde (G) with the largest size was catalyzed by these nanocages, only Zn2Er8L38 with the largest cavity size exhibited certain catalytic ability, overwhelming catalysis advantage compared with Zn2Er4L14 and Zn4Er6L26. Although other possible effects cannot be completely excluded, the synergy of confinement space, the size of open windows, and the number of Lewis acidic sites in the nanocage play a key role in the selectivity of intermediate and the import or export of guest molecules.

The differentiation of representative substrates with different sizes and steric hindrance for three-component aza-Darzens reaction catalyzed by Zn2Er4L14, Zn4Er6L26, and Zn2Er8L38. Reaction condition: anilines (0.5 mmol for A-G), aldehyde (0.6 mmol formaldehyde for A-D; 1.5 mmol propanal for E, 1.0 mmol aromatic aldehyde for F, G), α-diazo ester (0.7 mmol for A-D, F, G; 1.5 mmol for E), catalyst (0.4 mol% for A-E; 0.2 mol% for F, G), time (0.5 h for A-D; 2 h for E; 6 h for F, G), room temperature.

Although it was difficult to characterize and analyze the formation of the inclusion complexes due to paramagnetic effect of lanthanide Er3+ ion in NMR, we still performed NMR titration experiments in CD3CN/DMSO-d6 through 1H and 19F NMR. When N-benzylideneaniline intermediate was added to the solution of Zn2Er8L38 cage, the signals of H atoms in guest molecule were broadened severely compared with those of the pure compound in deuterium reagent, and 1H NMR signals of of N-benzylideneaniline shifted to high magnetic fields with ~0.05 ppm (Supplementary Fig 33). In addition, 19F NMR spectroscopy of guest molecule N-(4-fluorophenyl)methanimine as an intermediate was measured in CD3CN/DMSO-d6 (100:1, v/v) to track the formation of the inclusion complexes in the cage. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 34, 19F NMR spectrum of free N-(4-fluorophenyl)methanimine showed a sharp and single peak at – 125.05 ppm. Significantly, a new peak was found clearly at − 129.30 ppm, which could be belonged to the 19F signal of Zn2Er8L38 nanocage-encapsulated N-(4-fluorophenyl)methanimine. Furthermore, the 1H-DOSY experiments of {N-(4-fluorophenyl)methanimine}@Zn2Er8L38 systems was carried out to investigate host−guest interactions (Supplementary Fig. 35). The experiment result revealed two distinct diffusion coefficients (Log D) for the host cage (− 9.09) and the guest compound (− 8.90), indicating dynamic host−guest interactions. In contrast, 1H NMR spectra of N-benzylideneaniline (Supplementary Fig. 36) and 19F NMR spectra of N-(4-fluorophenyl)methanimine (Supplementary Fig. 37) in the presence of L3 showed that there were no change in NMR, which indicated that the guest molecules could not bind with ligand on the external surface of the cage.

To understand the host−guest interaction, UV-vis titration experiments were performed to estimate the interaction between main substrate molecules and host cages (Supplementary Fig. 38–40). The titration of a single component (α-diazo ester, N-methyleneaniline, or aziridine product) could be better fitted by a 1:1 host−guest model, and the associate constants (Ka) were calculated. For small molecule α-diazo ester, Ka values were 6.95 × 104 M–1 for host Zn2Er4L14, 8.55 × 104 M–1 for host Zn4Er6L26 and 1.40 × 105 M–1 for host Zn2Er8L38, respectively. For intermediate molecule N-methyleneaniline, Ka values were 9.61 × 104 M–1 for Zn2Er4L14, 4.52 × 104 M–1 for Zn4Er6L26, and 5.32 × 104 M–1 for Zn2Er8L38, respectively. However, Ka values of product 4a with host cage were found to be 8.37 × 103 M–1 for Zn2Er4L14, 6.22 × 103 M–1 for Zn4Er6L26, and 5.39 × 103 M–1 for Zn2Er8L38, respectively, much less than those Ka values of substrates. The result indicated that the catalytic process of the host supramolecular cages mainly went through the uptake of substrate molecules and the release of the product molecules, which worked continuously to facilitate the aza-Darzens reaction and achieve the repeated use of the catalyst.

The competition experiments also were performed to further prove the host-guest effect of the nanocage. Tartaric acid (TA), a competing guest molecule, was first added to the solution of nanocages, and the Ka values of TA were calculated to be 9.52 × 104 M−1 for Zn2Er4L14, 5.95 × 104 M−1 for Zn4Er6L26, and 6.18 × 104 M−1 for Zn2Er8L38, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 41). Then, the three-component aza-Darzens reaction was carried out by using aniline, formaldehyde, and α-diazo ester under optimal experimental conditions. The reaction conversions were poor for all composite catalysts, and the yields of the product 4a were only 7 % for Zn2Er4L14, 20 % for Zn4Er6L26, and 0 % for Zn2Er8L38, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 42–44). This is principally because the strong competing guest prevents substrate molecules from entering smoothly the cavity of the nanocage. Therefore, the confinement space is a crucial factor to accelerate the interactions between substrate and catalytic site, which would boost effectively multi-component reaction in nanoreactor.

Furthermore, the cyclic experiments of these cages were carried out and the recyclability was then tested over 4 cycles, demonstrating a negligible decline in catalytic performance and product yield for nanocages (Supplementary Fig. 45). In addition, all recycled nanocages were found to maintain their original cage structures, evidenced by almost identical FT-IR, UV−vis, and near-infrared (NIR) emission spectra (Supplementary Figs. 46–48). These results implied that the structure of these nanocages could not be damaged and the catalysts could exist stably in the reaction solution.

Theoretical calculations

To understand the differences among three nanocages in the confinement effect and the substrate selectivity, especially for the formation of the disubstituted N-aryl aziridine, the density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to estimate the interaction energies between host nanocage and guest molecules in the cavity environment. The structures of three nanocages were first optimized by DFT calculation, which present a series of stable cavities with different sizes. Then, the substrates, α-diazo ester and intermediate N-benzylideneaniline, were placed simultaneously in these nanocages, and their relative locations in mixed systems were self-adjusted and self-optimized further by DFT. Finally, the lowest energy and binding energy of every mixed system containing α-diazo ester, N-benzylideneaniline and nanocage were calculated.

As shown in Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 49, and Fig. 50, the small molecule α-diazo ester can enter freely and be trapped in the cavities of all nanocages. However, the larger intermediate N-benzylideneaniline cannot be encapsulated in the cavity of Zn2Er4L14, but can only enter and exist in the cavities of host Zn4Er6L26 and Zn2Er8L38. For the substrates in three nanocages, the binding energies were calculated to be + 32.82 kcal·mol–1 for Zn2Er4L14, – 66.78 kcal·mol–1 for Zn4Er6L26, and – 78.42 kcal·mol–1 for Zn2Er8L38, respectively. The positive binding energy for Zn2Er4L14 suggests that the cage size is insufficient to accommodate the substrates because of steric hindrance so that the aza-Darzens reaction is inhibited. In contrast, the negative binding energies for Zn4Er6L26 and Zn2Er8L38 imply that all substrates tend to enter the cage, and the confinement in Zn2Er8L38 with the largest cavity size is highly favorable for host−guest interaction and subsequent catalytic reaction in microcavity.

a Calculated interaction energy (left) and IGMH analysis (right) for the substrates (α-diazo ester and intermediate N-benzylideneaniline) in the cavity of nanocage Zn2Er4L14 a, Zn4Er6L26 (b), and Zn2Er8L38 (c). The color scale shows a range of interaction strength from strong attraction (blue) to weak interaction close to van der Waals radii (green), to strong repulsion (red). Computational methods: B3LYP-D3/6-31(G(d)/Lanl2DZ/MWB57.

Specifically, even the imine intermediates, N-(4-nitrophenyl)methanimine and 4-(methyleneamino)benzoic acid, that are hard to get due to strong electron-withdrawing effect of p–NO2 and p–COOH, the binding energies of these intermediates in the cavity of the largest host Zn2Er8L38 also could be calculated to obtain – 65.91 kcal·mol–1 and – 64.23 kcal·mol–1, respectively, more favorable for catalyzing the reaction (Supplementary Fig. 51). But the fact that the products (4r and 4s) are trace indicated that the formation of imine intermediate is the most important step, and the confinement effect of the cavity size only one of the conditions for the three-component aza-Darzens reaction to proceed. Moreover, the reason that less products (4g, 4m, 4q and 5w) were obtained in the smallest Zn2Er4L14 cage might be well explained by the synergy of steric hindrance of substrate molecules and positive binding energies (+ 30.92 kcal·mol–1~+ 43.17 kcal·mol–1) for α-diazo ester and intermediates (Supplementary Fig. 52).

The weak interactions in the catalytic system have been exhibited by the independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition (IGMH) analysis63,64. The area of the red isosurface between these independent molecules represents the steric hindrance of the weak interaction, which can be qualitatively measured by the sign(λ2)ρ corresponding to the maximum δg in the red region. Obviously, the isosurfaces in the cage Zn2Er8L38 are all green (Fig. 6) and the system of Zn2Er8L38 has a minimum value of sign(λ2)ρ (0.009227) compared to that in Zn2Er4L14 (0.041627) and Zn4Er6L26 (0.030682), indicating that the substrates in host Zn2Er8L38 have minimal steric hindrance and repulsive interaction. Thus, the larger substrates can be exchanged and catalyzed easily in the nanocage, which is closely consistent with the experimental trend.

Catalytic mechanism

The three-component aza-Darzens reaction involves two key steps: intermolecular nucleophilic attack of the C-C bond (key I) and intramolecular nucleophilic attack of the C-N bond (key II). When there is no catalyst or an inefficient catalyst is present in the system, the aza-Darzens reaction can be severely inhibited by the above two key steps, showing a slow reaction rate or a difficult reaction process, especially for those disubstituted aryl aziridine compounds (Fig. 7a). Hence, these nucleophilic attack processes can be accelerated by increasing the number of Lewis acidic sites and enhancing the coordination binding, and the intramolecular cyclization process can be promoted by increasing the collision probability of functional groups. Significantly, unlike conventional homogeneous catalysis in the free diffusion model, the designed supramolecular nanocages, especially Zn2Er8L38, are well integrated with multiple lanthanide Lewis acidic sites and confined nanospace (Supplementary Table 9). The various substrates can be encapsulated easily in the cavity of the cage and be coordinated with multiple Lewis acidic sites, accompanied by a quick release of the product molecules due to the steric hindrance effect and the efficient promotion of aza-Darzens reaction (Fig. 7b). Thus, the two key factors, key I and key II, are self-regulated simultaneously by using this kind of nanocage.

a Two key steps in free diffusion fashion for the three-component aza-Darzens reaction: intermolecular nucleophilic attack of the C-C bond (key I) and intramolecular nucleophilic attack of the C-N bond (key II). b The graphical representations for the integration strategy of multiple lanthanide Lewis acidic sites and confined nanospace in supramolecular nanocage Zn2Er8L38 to promote two key steps of three-component aza-Darzens reaction. c The proposed mechanism for the three-component aza-Darzens reaction catalyzed by Zn2Er8L38 nanocage.

To gain insight into the mechanism of the three-component aza-Darzens reaction catalyzed by coordination cages, a series of NMR experiments for 5a were performed in detail. The intermediate N-benzylideneaniline is generated rapidly by the reaction of the benzaldehyde and aniline in solution whether the catalyst exists or not (Supplementary Fig. 53). Then, the inclusion complex of Zn2Er8L38 cage and N-benzylideneaniline is formed through the encapsulation behavior of cage, supported by the signal change of N-benzylideneaniline in 1H NMR (Supplementary Fig. 33). Immediately, two new peaks near 3.5 ppm were gradually increased, suggesting the formation of cyclization product 5a (Fig. 4c). Kinetic analysis of the aza-Darzens reaction for aniline suggested that it was in accord with first-order kinetics model, and the equilibrium of N-benzylideneaniline inclusion was not relevant to the catalytic processes but depended only on the concentration of substrate. The ratio of the reaction rate constants K(Zn2Er8L38)/K(catalyst-free) reached 36, suggesting high encapsulation efficiency and extraordinary acceleration effect of Zn2Er8L38 cage for guest molecules (Supplementary Fig. 54).

Furthermore, the reaction pathways of product 5a catalyzed by Zn2Er8L38 and catalyst-free were calculated and simulated by using DFT (Supplementary Fig. 55). Using N-benzylideneaniline as a starting material, the reaction process involves two key steps, intermolecular nucleophilic attack of electronegative C atom in α-diazo ester and intramolecular nucleophilic attack of N atom in the intermediate. In the absence of any catalyst, the main energy levels of reaction transition states for TS3 and TS4 are 55.45 kcal/mol–1 and 50.39 kcal/mol–1, respectively, and the energy level of 5a is –26.89 kcal/mol–1. However, when lanthanide Er3+ ion is chosen as the Lewis acidic site, the transition state levels of intermediates and the energy level of the coordination product decline significantly, resulting in the promotion of the reaction.

Based on the above results, a possible mechanism for this three-component aza-Darzens reaction catalyzed by the Zn2Er8L38 cage was proposed. As shown in Fig. 7c, the intermediate imine compound, such as N-methyleneaniline or N-benzylideneaniline, is generated rapidly by the reaction of the aldehyde compound with aniline, followed by the encapsulation of the empty Zn2Er8L38 nanocage I to form complex intermediate II. In the cavity, the lanthanide Er3+ ion as the Lewis acidic site coordinates with the N atom of the imine compound, resulting in the stabilization of the dynamic imine intermediate. Immediately, the α-diazo ester goes close to the anchored imine compound in the cage and its electron-rich C atom takes place intermolecular nucleophilic attack to construct a C-C bond and form an intermediate III. Subsequently, an intramolecular nucleophilic displacement takes place and the cyclization reaction is completed to obtain intermediate product IV, in which the coordination ability of product molecule with aza-heterocycle is weakened because of steric hindrance effect and the new molecule can be easily crowded out of the cage. Finally, a target product aziridine is generated, accompanied with the release and regeneration of the catalyst Zn2Er8L38 cage.

Discussion

In conclusion, we reported the design of a series of 3d-4f supramolecular nanocages, Zn2Er4L14, Zn4Er6L26 and Zn2Er8L38, constructed by a “bimetallic cluster cutting” strategy that could utilize steric hindrance and flexibility of nonsymmetric ligand to control the disassembly of lanthanide metallic cluster unit. Three nanocages exhibited stepwise increased catalytic sites and growing cavity sizes as the number of lanthanide ions increased, which were synergistically and significantly affecting the three-component aza-Darzens reaction in the nanocages. Significantly, the nanocage Zn2Er8L38 with the largest cavity and the most Er3+ centers had the highest catalytic conversion (88 % yield) only in 0.5 h for monosubstituted N-aryl aziridine product without another additive under mild conditions, and catalytic conversion for more complex disubstituted N-aryl aziridine product also could be achieved 81 % yield in 6 h. Structure−activity relationship investigations and theoretical calculations showed that Zn2Er8L38 outperformed significantly Zn2Er4L14 with the smaller cavity and Zn4Er6L26 with the fewer Lewis acidic sites in the catalytic reaction, suggesting that the acceleration of multi-component aza-Darzens reactions for nanocage Zn2Er8L38 is attributed to the synergy of inherent confinement effect and multiple Lewis acidic sites in the nanocage. The study represents a meaningful exploration for the design and the construction of discrete 3d−4f nanocages with substrate selectivity and catalytic turnover, and the “bimetallic cluster cutting” strategy may be a potential approach in developing supramolecular nanoreactor with high catalytic efficiency.

Methods

Synthesis of Zn2Er4L1 4 59

A mixture of L1 (23.5 mg, 0.05 mmol) and triethylamine (16 μL, 0.22 mmol) in methanol (6 mL) were stirred. Then, ZnCl2 (6.8 mg, 0.05 mmol), Er(NO3)3·5H2O (22 mg, 0.05 mmol) added and stirred at room temperature. After a week, yellow lump crystals suitable for crystal analysis were filtered, washed three times with cold methanol, and dried in air. (yield, 45.0 %) ESI-MS {[Er4Zn2(L1−3H+)4Cl2]2+·NO3–·4H2O·2CH3OH + H+}2+ m/z: calcd. for [C90H105N21O37Cl2Zn2Er4]2+ 1472.6243, found: 1472.6239. IR (KBr pellets, cm–1): 3340.8(m), 2978.5(s), 2926.6(w), 2860.4(w), 1610(w), 1606(s), 1539.8(m), 1458.3(m), 1382.5(m), 1320.3(w), 1239.7(m), 1215.8(s), 1110.4(w), 1081.7(w), 896.6(m), 743.3(m).

Synthesis of Zn4Er6L2 6

A mixture of L2 (31.4 mg, 0.05 mmol) and triethylamine (16 μL) in methanol (6 mL) were stirred at room temperature. Then, ZnCl2 (6.8 mg, 0.05 mmol), Er(NO3)3·5H2O (22 mg, 0.05 mmol) added and stirred. After three weeks, yellow block crystals suitable for crystal analysis were filtered, washed three times with ethyl ether, and dried in air. The yield is 39 % based on the ligand. ESI-MS {[Er6Zn4(L2–4H+)3(L2–3H+)3]·3NO3–·CH3OH·2H2O}2+ (C206H280N34O41Zn4Er6) m/z: 2576.6920 (found), 2576.6973 (simulated). IR (KBr pellets, cm−1): 3421.5(m), 2953.8(m), 1606.8(s), 1530.5(w), 1432.9(w), 1385.2(s), 1328.2(w), 1257.1(w), 1235.5(w), 1202.9(w), 1166.5(m), 1032.4(w), 879.8(w), 843.4(w), 787.8(w), 745.7(w).

Synthesis of Zn2Er8L3 8

A mixture of L3 (31.5 mg, 0.05 mmol) and triethylamine (16 μL) in methanol (6 mL) were stirred. Then, ZnCl2 (6.8 mg, 0.05 mmol), Er(ClO4)3·xH2O (24.2 mg, 0.05 mmol) added and stirred at room temperature. After a week, yellow block crystals suitable for crystal analysis were filtered, washed three times with ethyl ether, and dried in air. The yield is 63 % based on the ligand. ESI-MS {[Er8Zn2(L3–3H+)8Cl2]·H2O·CH3CN}2+ (C282H389N41O41Cl2Zn2Er8) m/z: 3274.1098 (found); 3274.1094 (simulated). IR (KBr pellets, cm−1): 3524.3(w), 3356.1(w), 2961.8(s), 2904.3(w), 2867.8(w), 1613.2(s), 1530.4(s), 1463.5(w), 1430.9(m), 1384.9(m), 1357.9(w), 1254.3(m), 1171.3(m), 1101.3(m), 841.9(w), 783.2(w), 740.9(w), 626.7(w), 510.8(w).

General procedure for optimization of catalysis conditions

Catalyst, aniline, formaldehyde, α-diazo ester, and 4 mL solvent were sealed in a 25 mL round bottom flask. Subsequently, the solution was stirred for some time at room temperature under N2 atmosphere. After the reaction was completed, the solvent of the mixture was removed by rotary evaporation, and the resulting residue was extracted with dichloromethane (3×5 mL). The precipitated catalyst in dichloromethane was isolated and recycled. The solvent of the extract was removed under reduced pressure to give the crude product. The resulting crude product was dissolved in CDCl3 and a stock solution of 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane (0.5 mmol) was added, and the yield of the target product was determined by 1H NMR.

The experimental procedure for the gram-scale synthesis of 4a

Aniline (0.93 g, 10 mmol), formaldehyde (2.03 g, 12 mmol, 37 % v/v water), α-diazo ester (2.27 g, 14 mmol, 89 % v/v dichloromethane) and Zn2Er8L38 (0.4 mol% for aniline) were mixed in 80 mL of acetonitrile in a 250 mL round bottom flask. Subsequently, the solution was stirred for 3 h at room temperature under N2 atmosphere. After the reaction was completed, the solvent of the mixture was removed by rotary evaporation, and the resulting residue was extracted with dichloromethane (3×5 mL). The solvent of the extract was removed under reduced pressure to give the crude product. The product was purified via column chromatography (ethyl acetate/hexane) to obtain 4a (1.62 g, 85 % yield) as a yellow oil.

General procedure for disubstituted N-aryl aziridines (5a-w) catalyzed by catalyst Zn2Er8L3 8

In a typical procedure for 5a-w, catalyst Zn2Er8L38 (0.2 mol %), aniline (0.5 mmol), aromatic aldehyde (1.0 mmol), α-diazo ester (89 % v/v dichloromethane, 0.7 mmol), and 4 mL CH3CN were sealed in a 25 mL round bottom flask. Subsequently, the solution was stirred for 6 h at room temperature under N2 atmosphere. After the reaction was completed, the solvent of the mixture was removed by rotary evaporation, and the resulting residue was extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 5 mL). The precipitated catalyst in dichloromethane was isolated and recycled. The solvent of the extract was removed under reduced pressure to give the crude product. The resulting oil crude product was dissolved in CDCl3 and a stock solution of 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane (0.5 mmol) was added, and the yield of the target product was determined by 1H NMR. The product was purified via column chromatography (ethyl acetate/hexane) to obtain the disubstituted N-aryl aziridines as a yellow oil (Supplementary Appendix II). All isolated and purified disubstituted N-aryl aziridine derivatives are cis configuration, and the configuration of representative 5a has been determined by 1D NOE difference spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 56). The coupling constant (J H-H) of the aziridine ring in 1H NMR is ca. 6.9 Hz.

General procedure for NMR titration

The catalyst was added in the mixture of CD3CN and DMSO-d6 (2 × 10−3 M), and then a series of guest molecules with different equivalent were added and stirred at room temperature for 1 hour. After the solution was filtered, the NMR spectrum was determined at room temperature.

UV−vis titration for host−guest interaction

The titration experiments were carried out by adding 50.0 μL solution of substrate, guest compound (1.0 × 10−4 mol·L−1) or product (1.0 × 10−3 mol·L−1), to a solution of Zn2Er4L14, Zn4Er6L26 or Zn2Er8L38 (2.5 × 10−6 mol·L−1) in 3.0 mL CH3CN every 5 min. A series of absorption curves were measured at room temperature. UV–vis spectra of the system including cage and guest at the corresponding concentrations were also recorded for background subtraction. The binding constants (Ka) were calculated via the binding isotherms performed on the Benesi−Hildebrand (B-H) plots based on 1:1 binding model65,66.

Competitive experiment of host−guest interaction

Tartaric acid (TA) was selected as a competing guest molecule to occupy first the cavity of cage. In a typical procedure, the catalyst cage (Zn2Er4L14, Zn4Er6L26 or Zn2Er8L38, 0.4 mol %), TA (0.2 mmol), aniline (0.5 mmol), formaldehyde (37 % v/v water, 0.6 mmol), α-diazo esters (89 % v/v dichloromethane, 0.7 mmol), and 4 mL CH3CN were sealed in a 25 mL round bottom flask. Subsequently, the solution was stirred for 0.5 h at room temperature under N2 atmosphere. After the reaction was completed, the solvent of the mixture was removed by rotary evaporation, and the resulting residue was extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 5 mL). The solvent of the extract was removed under reduced pressure to give the crude product. The resulting oil crude product 4a was dissolved in CDCl3 and a stock solution of 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane (0.5 mmol) was added, and the yield of the target product 4a was determined by 1H NMR.

Kinetic study

The kinetic studies of three-component aza-Darzens reaction for disubstituted N-aryl aziridine in the presence of catalyst Zn2Er8L38 and catalyst-free were carried out. The concentration changes of aniline and 5a were monitored by 1H NMR analysis.

Theoretical calculations for host-guest encapsulation

Density functional theory calculations were performed using the Gaussian 16 software package67. Geometries of all molecules were optimized using the B3LYP functional with D3 (zero damping) dispersion corrections and the 6-31G(d)/Lanl2DZ/MWB57 basis set (the 6-31G(d) basis set for nonmetal atoms, the Lanl2DZ basis set for Zn atom and the MWB57 basis set for Er atom)68. Moreover, at the same level, vibrational frequencies were computed to verify no imaginary frequency in energy minima, and the binding energy of the cage and substrates were calculated. Furthermore, the weak interaction of cage and substrates was analyzed by IGMH analysis of Multiwfn63,64. The graphics were drawn by Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD)69. The computational data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file.

Crystallographic data

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction measurements of Zn4Er6L26 and Zn2Er8L38 were carried out on a Bruker SMART APEX-II CCD diffractometer with graphite monochromated Mo-Kα (λ = 0.71073 Å) radiation. Multi-scan absorption correction was applied with the SADABS program. Unit cell dimensions were obtained with least-squares refinements, and all structures were solved by direct methods using SHELXS-201770. Metal atoms in each complex were located from E-maps. The non-hydrogen atoms were located in successive difference Fourier syntheses. The final refinement was performed by full matrix least-squares methods with anisotropic thermal parameters for non-hydrogen atoms on F2. The hydrogen atoms were introduced at calculated positions and not refined (riding model). Crystallographic data as well as details of data collection and refinement for Zn4Er6L26 and Zn2Er8L38 is summarized in Supplementary Table 1 whereas selected bond lengths and angles are listed in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this article are available in the paper and in the Supplementary Information. DFT optimized coordinates are in separate excel file as Source Data. Additional data are available from the corresponding author on request. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, under deposition numbers CCDC 2299706 (Zn4Er6L26) and 2306791 (Zn2Er8L38). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Jing, X. et al. Control of redox events by dye encapsulation applied to light-driven splitting of hydrogen sulfide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 11759–11763 (2017).

Salles, A. G. Jr., Zarra, S., Turner, R. M. & Nitschke, J. R. A self-organizing chemical assembly line. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 19143–19146 (2013).

Yan, D. N. et al. An organo-palladium host built from a dynamic macrocyclic ligand: adaptive self-assembly, induced-fit guest binding, and catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202209879 (2022).

Jiao, Y. et al. Highly efficient supramolecular catalysis by endowing the reaction intermediate with adaptive reactivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 6077–6081 (2018).

Yu, Y. & Rebek, J. Jr. Reactions of folded molecules in water. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 3031–3040 (2018).

Grommet, A. B., Feller, M. & Klajn, R. Chemical reactivity under nanoconfinement. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 256–271 (2020).

Takezawa, H., Shitozawa, K. & Fujita, M. Enhanced reactivity of twisted amides inside a molecular cage. Nat. Chem. 12, 574–578 (2020).

Jiao, Y. et al. A donor–acceptor [2]catenane for visible light photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 8000–8010 (2021).

Sun, Q. F. et al. Self-assembled M24L48 polyhedra and their sharp structural switch upon subtle ligand variation. Science 328, 1144–1147 (2010).

Cook, T. R. & Stang, P. J. Recent developments in the preparation and chemistry of metallacycles and metallacages via coordination. Chem. Rev. 115, 7001–7045 (2015).

Hong, C. M., Bergman, R. G., Raymond, K. N. & Toste, F. D. Self-assembled tetrahedral Hosts as supramolecular catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 2447–2455 (2018).

Zhao, L. et al. Catalytic properties of chemical transformation within the confined pockets of Werner-type capsules. Coord. Chem. Rev. 378, 151–187 (2019).

Du, M. H. et al. Modification of multi-component building blocks for assembling giant chiral lanthanide-titanium molecular rings. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202116296 (2022).

Meeuwissen, J. & Reek, J. N. H. Supramolecular catalysis beyond enzyme mimics. Nat. Chem. 2, 615–621 (2010).

Cheng, P. M. et al. Guest-reaction driven cage to conjoined twin-cage mitosis-like host transformation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 23569–23573 (2020).

Zhao, L., Cai, J., Li, Y., Wei, J. & Duan, C. A host-guest approach to combining enzymatic and artificial catalysis for catalyzing biomimetic monooxygenation. Nat. Commun. 11, 2903 (2020).

Li, K. et al. Creating dynamic nanospaces in solution by cationic cages as multirole catalytic platform for unconventional C(sp)-H activation beyond enzyme mimics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202114070 (2022).

Ngai, C. et al. Moderated basicity of endohedral amine groups in an octa-cationic self-assembled cage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202117011 (2022).

Vardhan, H., Yusubov, M. & Verpoort, F. Self-assembled metal-organic polyhedra: an overview of various applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 306, 171–194 (2016).

Guo, J., Fan, Y. Z., Lu, Y. L., Zheng, S. P. & Su, C. Y. Visible-light photocatalysis of asymmetric [2+2] cycloaddition in cage-confined nanospace merging chirality with triplet-state photosensitization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 8661–8669 (2020).

Jiao, J. et al. Design and assembly of chiral coordination cages for asymmetric sequential reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2251–2259 (2018).

Fang, Y. et al. Catalytic reactions within the cavity of coordination cages. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 4707–4730 (2019).

Morimoto, M. et al. Advances in supramolecular host-mediated reactivity. Nat. Catal. 3, 969–984 (2020).

Percástegui, E. G., Ronson, T. K. & Nitschke, J. R. Design and applications of water-soluble coordination cages. Chem. Rev. 120, 13480–13544 (2020).

Gosselin, A. J., Rowland, C. A. & Bloch, E. D. Permanently microporous metal-organic polyhedra. Chem. Rev. 120, 8987–9014 (2020).

Saha, R., Mondal, B. & Mukherjee, P. S. Molecular cavity for catalysis and formation of metal nanoparticles for use in catalysis. Chem. Rev. 122, 12244–12307 (2022).

Li, S. C., Cai, L. X., Hong, M., Chen, Q. & Sun, Q. F. Combinatorial self-assembly of coordination cages with systematically fine-tuned cavities for efficient co-encapsulation and catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202204732 (2022).

Zhu, M. et al. {Mo126W30}: polyoxometalate cages shaped by π-π interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202213910 (2022).

Jiao, J. et al. Design and self-assembly of hexahedral coordination cages for cascade reactions. Nat. Commun. 9, 4423 (2018).

McConnell, A. J. Metallosupramolecular cages: from design principles and characterisation techniques to applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 2957–2971 (2022).

Shi, J. et al. Self-assembly of metallo-supramolecules with dissymmetrical ligands and characterization by scanning tunneling microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 1224–1234 (2021).

Lewis, J. E. M. Molecular engineering of confined space in metal-organic cages. Chem. Commun. 58, 13873–13886 (2022).

Yu, H. et al. Conformational control of a metallo-supramolecular cage via the dissymmetrical modulation of ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 26523–26527 (2021).

Guo, J. et al. Regio- and enantioselective photodimerization within the confined space of a homochiral ruthenium/palladium heterometallic coordination cage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 3852–3856 (2017).

Wang, Y., Chen, J., Yang, J., Jiao, Z. & Su, C. Y. Elaborating E/Z-geometry of alkenes via cage-confined arylation catalysis of terminal olefins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202303288 (2023).

Lu, Y. L. et al. A redox-active supramolecular Fe4L6 cage based on organic vertices with acid-base-dependent charge tunability for dehydrogenation catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 8778–8788 (2022).

Amouri, H., Desmarets, C. & Moussa, J. Confined nanospaces in metallocages: guest molecules, weakly encapsulated anions, and catalyst sequestration. Chem. Rev. 112, 2015–2041 (2012).

He, Q. T. et al. Nanosized coordination cages incorporating multiple Cu(I) reactive sites: host-guest modulated catalytic activity. ACS Catal. 3, 1–9 (2013).

Brown, C. J., Toste, F. D., Bergman, R. G. & Raymond, K. N. Supramolecular catalysis in metal-ligand cluster hosts. Chem. Rev. 115, 3012–3035 (2015).

Xue, Y. et al. Catalysis within coordination cages. Coord. Chem. Rev. 430, 213656 (2021).

Spicer, R. L. et al. Host-guest-induced electron transfer triggers radical-cation catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 2134–2139 (2020).

Bierschenk, S. M. et al. Impact of host flexibility on selectivity in a supramolecular host-catalyzed enantioselective aza-Darzens reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 11425–11433 (2022).

Cullen, W. et al. Catalysis in a cationic coordination cage using a cavity-bound guest and surface-bound anions: inhibition, activation, and autocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2821–2828 (2018).

Tang, X. et al. Homochiral porous metal-organic polyhedra with multiple kinds of vertices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 2561–2571 (2023).

Wang, S. Y. et al. Multicomponent self-assembly of metallo-supramolecular macrocycles and cages through dynamic heteroleptic terpyridine complexation. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 9274–9284 (2018).

Aroussi, B. E., Zebret, S., Besnard, C., Perrottet, P. & Hamacek, J. Rational design of a ternary supramolecular system: self-assembly of pentanuclear lanthanide helicates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 10764–10767 (2011).

Wang, Z. et al. Coordination-assembled water-soluble anionic lanthanide organic polyhedra for luminescent labeling and magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 16409–16419 (2020).

Li, X. Z., Tian, C. B. & Sun, Q. F. Coordination-directed self-assembly of functional polynuclear lanthanide supramolecular architectures. Chem. Rev. 122, 6374–6458 (2022).

Kitchen, J. A. Lanthanide-based self-assemblies of 2,6-pyridyldicarboxamide ligands: recent advances and applications as next-generation luminescent and magnetic materials. Coord. Chem. Rev. 340, 232–246 (2017).

Barry, D. E., Caffrey, D. F. & Gunnlaugsson, T. Lanthanide-directed synthesis of luminescent self-assembly supramolecular structures and mechanically bonded systems from acyclic coordinating organic ligands. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 3244–3274 (2016).

Bünzli, J. C. G. & Piguet, C. Lanthanide-containing molecular and supramolecular polymetallic functional assemblies. Chem. Rev. 102, 1897–1928 (2002).

Bew, S. P., Liddle, J., Hughes, D. L., Pesce, P. & Thurston, S. M. Chiral brønsted acid-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of N-Aryl-cis-aziridine carboxylate esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 5322–5326 (2017).

Jeong, J. U., Tao, B., Sagasser, I., Henniges, H. & Sharpless, K. B. Bromine-catalyzed aziridination of olefins. a rare example of atom-transfer redox catalysis by a main group element. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 6844–6845 (1998).

Tanner, D. Chiral aziridines-their synthesis and use in stereoselective transformations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 33, 599–619 (1994).

Singh, G. S., D’Hooghe, M. & De Kimpe, N. Synthesis and reactivity of C-heteroatom-substituted aziridines. Chem. Rev. 107, 2080–2135 (2007).

Degennaro, L., Trinchera, P. & Luisi, R. Recent advances in the stereoselective synthesis of aziridines. Chem. Rev. 114, 7881–7929 (2014).

Bierschenk, S. M., Bergman, R. G., Raymond, K. N. & Toste, F. D. A nanovessel-catalyzed three-component aza-Darzens reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 733–737 (2020).

Feng, X., Song, Y. & Lin, W. Dimensional reduction of Lewis acidic metal-organic frameworks for multicomponent reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 8184–8192 (2021).

Zhou, S. et al. A discrete 3d-4f metallacage as an efficient catalytic nanoreactor for a three-component aza-Darzens reaction. Inorg. Chem. 61, 4009–4017 (2022).

Vincenzo, P. et al. γ-Cyclodextrins as supramolecular reactors for the three-component aza-Darzens reaction in water. Chem. Eur. J. 30, e202303984 (2024).

Saraci, F., Quezada-Novoa, V., Donnarumma, P. R. & Howarth, A. J. Rare-earth metal-organic frameworks: from structure to applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 7949–7977 (2020).

Xie, W., Fang, J., Li, J. & Wang, P. G. Aziridine synthesis in protic media by using lanthanide triflates as catalysts. Tetrahedron 55, 12929–12938 (1999).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition: a new method for visual study of interactions in chemical systems. J. Comput. Chem. 43, 539–555 (2022).

Thordarson, P. Determining association constants from titration experiments in supramolecular chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 1305–1323 (2011).

Shiraishi, Y., Sumiya, S., Kohno, Y. & Hirai, T. A rhodamine-cyclen conjugate as a highly sensitive and selective fluorescent chemosensor for Hg(II). J. Org. Chem. 73, 8571–8574 (2008).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision E.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT (2013).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996).

Sheldrick, G. M. Programs for the refinement of crystal structures. SHELX-2017, (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 22171112, 22221001, 22131007), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (lzujbky-2023-stlt01), the Science and Technology Major Plan of Gansu Province (23ZDGA012), and Supercomputing Center of Lanzhou University. We thank Fengming Qi for NMR assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L., X.T., Y.T. and W.L. designed the research. J.L. did most of the experiments including the catalysts synthesis and the catalytic activity evaluation. M.K. provided the theoretical calculation support. S.Z., F.D., and X.H. analyzed the data. J.L. and X.T. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors read and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yiming Li, Antonio Rescifina and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Kou, M., Zhou, S. et al. Regulation of lanthanide supramolecular nanoreactors via a bimetallic cluster cutting strategy to boost aza-Darzens reactions. Nat Commun 16, 2169 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54950-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54950-3

This article is cited by

-

Engineered microbial platform confers resistance against heavy metals via phosphomelanin biosynthesis

Nature Communications (2025)