Abstract

Wireless energy-responsive systems provide a foundational platform for powering and operating intelligent devices. However, current electronic systems relying on complex components limit their effective deployment in ambient environment and seamless integration of energy harvesting, storage, sensing, and communication. Here, we disclose a coupling effect of electromagnetic wave absorption and moist-enabled generation on carrier transportation and energy interaction regulated by ionic diode effect. As demonstration, a wireless energy interactive system is established for electromagnetic-moist coupled energy harvesting and signal transmission through highly integrated polyelectrolyte/conjugated conductive polymer bilayer ionic diode films as dynamic energy-switching carriers. The gradient distribution of ions within the films, excited by moist energy, enables the ionic rectification and further endows the films with electromagnetic energy harvesting capability. In turn, the absorbed electromagnetic energy drives the directional migration of charge carriers and internal ionic current. By rationally regulating the electrolyte and dielectric properties of ionic diodes, it becomes feasible to control targeted electric signals and energy outputs under coupled electromagnetic-moist environment. This work is a step towards enabling enhanced smart interactivities for wirelessly driven flexible electronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the vigorous development of artificial intelligence & internet of things (AIoT), electromagnetic wave (EMW) has become an indispensable carrier for energy and information interaction1,2. AIoT devices require stable power management and environmental adaptability to ensure continuous operation and connectivity among devices across complex scenarios3. Simultaneously, the exponential proliferation of EMW may trigger electromagnetic interference and excessive radiation, even posing harm to information security, precision instruments, and human health4. Despite recent advances in electromagnetic interference shielding and EMW absorption materials (EMAs), electronic systems based on these materials still face harsh challenges, comprising but not limited to energy harvesting, energy storage, sensing, and communication5,6. Therefore, it is crucial to develop a smart, sustainable and seamlessly integrated wireless energy interactive system to enable contactless reception, conversion, and transmission of energy and signals.

Typically, an energy interactive system is a technology framework designed to efficiently harvest, convert, and manage multiple forms of energy from various sources to optimize overall system performance and functionality7,8. In pursuit of the aforementioned vision, the focus of the research is put on developing EMAs that can couple with the ambient environment, ultimately serving as a multiple dynamic energy-switching carriers. To implement multiple interactive functions using these EMAs, the following obstacles need to be addressed. (i) For electromagnetic wave absorption: to achieve high electromagnetic energy harvesting performance, the chemical composition, micro-nano morphology, and metamaterial structure of EMAs must be meticulously engineered to match impedance and mitigate electromagnetic loss, resulting in high EMW absorption efficiency and a wide effective absorption frequency bandwidth9, which in turn improves the performance of electrostatic capacitors10. (ii) For signal output: the operation of devices and signal visualization depends on the output of direct current (DC) signals, necessitating the scavenging of wireless electromagnetic energy and its conversion into a usable form, which usually requires the integration of various electronic components11. (iii) For intelligent interaction: ambient energy often manifests in various coupled modes, including wireless electromagnetic energy, DC energy, thermal energy, chemical energy, and kinetic energy, etc12. Therefore, it is critical to elucidate the fundamental physical mechanisms governing multi-energy field coupling to ensure the predominance of high-quality energy, thence enabling the development of flexible, comfortable, and chipless intelligent response wireless multi-energy interaction devices.

The exploration of electromagnetic energy harvesting can be traced back to Tesla’s experiments in the 20th century13, with subsequent advancements in rectennas and semiconductor diodes gradually enabling the realization of DC current output14,15. Rectennas, typically consisting of an electromagnetic collector (resistive loads) and a rectifier circuit (diodes), integrate resonance and DC current output functionalities, realizing both the harvesting and conversion of electromagnetic energy into electrical energy16, finally channeling the rectified DC current in a circuit. To promote the smart harvesting of electromagnetic energy, novel energy interactive systems have gradually emerged based on the thermoelectric effect17, ferroelectric effect18, and triboelectric effect19, etc (Supplementary Table 1). However, energy harvesting based on the electromagnetic-thermal coupling effect lacks effective energy storage and requires integration with external storage devices such as capacitors and batteries20,21. To solve the storage issue, contact coupling with energy carriers was performed by inducing interface capacitance and redistributing charges, but contact operating mode may limit wireless far-field interaction22. Moist-enabled electricity generation (MEG)23,24, an emerging energy harvesting technology that leverages the inexhaustible chemical potential of atmospheric water molecules, has recently achieved moist-electricity interaction, due to the surface potential difference and ionic current induced by the directional transport and asymmetric distribution of ionic charge carriers25,26. Notably, certain unique dielectric and electrolyte property changes induced by moisture, including the diode-like rectifying effect and interfacial micro-capacitance effect, have yet to be developed and utilized. On one hand, the diode effect is a fundamental condition of electromagnetic energy harvesting. On the other hand, radiated EMW can alter dynamic charge migration polarization, potentially changing the moist response characteristics. Therefore, investigating the energy interaction phenomenon and mechanism of electromagnetic-moist coupling through the ionic diode effect holds significant theoretical and practical merits, offering promising and innovative work modes in the field of intelligent energy interaction.

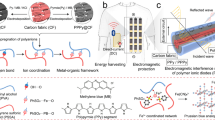

Herein, we carry out a fundamental study on the wireless, chipless coupled interaction between electromagnetic and moisture energy interaction with the regulation of ionic diodes effect. Unlike conventional electromagnetic energy interactive systems, which require integrating electronic components such as antennas, rectifiers, and storage devices onto a rigid circuit board, the wireless energy interactive system based on our study addresses challenges in smart environment coupling and multi-component integration (Fig. 1f). Given the ionic rectification effect induced by surface moist response, the prepared polyelectrolyte/conjugated conductive polymer ionic diode (PCID) films enabled the coupling and synergistic harvest of ambient moist and EMW energy. This work focuses much more on discovering an interesting scientific phenomenon and exploring its underlying fundamental mechanism, that is, the electromagnetic-moist coupling effect, rather than solely making a device for energy harvesting. This energy interactive mechanism offers opportunities for advancing electromagnetic energy harvesting materials using flexible EMAs, with potential applications in self-powered wireless charging, electromagnetic radiation detection, and information storage technologies.

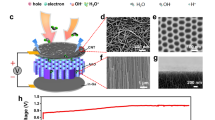

a Schematic of the chemical structure of P(AAm-co-AAc), P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl, and P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy. b Molecular structures and charge/discharge process in PCIDs. c1-c4 SEM and EDX elemental mapping images of MC100-2, d FTIR spectra of MC50-2, e Dynamic development of VO value of MC100-2 under moist and EMW radiation. f A schematic comparison between the conventional energy interactive system and our wireless energy interactive system, g Schematic illustration of the physical mechanism underlying the moist response of PCIDs. h Schematic illustration of the coupled physical mechanism underlying the electromagnetic-moist response of PCIDs.

Results

Design of electromagnetic-moist coupled wireless energy interaction and system

The PCIDs were fabricated by depositing electronically conductive polypyrrole (PPy) onto ionically conductive poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) (P(AAm-co-AAc)) through an electrochemical deposition technique (Fig. 1a). The as prepared PCID stood out as solid-state rectification system, bringing about the rectifying performance by counterions-selective asymmetry of carrier channels in heterogeneous film. Unlike conventional electron-based diodes with p-n heterojunctions, the diode-like rectifying behavior in ions transport-based devices depend on either permitting or restricting the flow of specific ions27. This approach not only offers enhanced controllability by manipulating the generation, diffusion, and migration properties of ionic charge carriers, but also demonstrates greater potential for practical applications since meticulously designed gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs) also serve as promising candidates for energy storage, making it theoretical feasible for realizing all-in-one device for harvesting and storing coupled electromagnetic-moist energy.

The PCIDs were then expected to be employed as electromagnetic-moist dynamic energy-switching carriers. As is illustrated in Fig. 1g, h when a PCID is exposed to an ambient moist environment, the COOH groups in P(AAm-co-AAc) undergo hydrolysis and ionization, releasing H+ ions, which will diffuse towards the PPy side due to concentration gradients and osmotic pressure (Fd,H, concentration driving force), resulting in a charge imbalance on the surface of P(AAm-co-AAc) and PPy28. PPy not only serves as an H+ collection layer, but also, owing to the PPyn+Cl-n structure generated by electrochemical deposition, can release Cl-, thereby further increasing the positive charge density of PPy as Cl- diffuses into P(AAm-co-AAc) via concentration driving force (Fd,Cl)29. Here, PCID behaves as a moisture-enabled electricity generator due to spontaneous ionic carriers separation30. When an EMW excitation is applied to the P(AAm-co-AAc) side of the PCID, the steady-state equilibrium created by ionic charge carriers under the dominant influence of concentration gradients and osmotic pressure will be disrupted. In addition to being acted upon by the forces of diffusion (Fd,H) and (Fd,Cl), these carriers will also experience the effect of the electromagnetic field (FE), which varies with the oscillation of the alternating electromagnetic field. In this context, once possessing both EMW absorption efficiency and diode-like properties, the PCID will play a role akin to rectennas, further leveraging the foundation of MEG to harvest electromagnetic energy and enhance DC output.

Firstly, P(AAm-co-AAc) hydrogels were prepared by UV-induced free radical polymerization method. In KCl electrolyte, the internal electric field caused pyrrole molecules to penetrate through the P(AAm-co-AAc) electrolyte adhered to the conductive glass (FTO) electrode and polymerize in situ on the electrode, resulting in the formation of P(AAm-co-AAc) hydrogel/PPy films. In order to solve the problems of film deformation and low strength caused by solvent evaporation, glycerol was used as a water-retaining agent to soak the above hydrogel composite film for 20 min to prepare the final P(AAm-co-AAc) organohydrogel/PPy PCIDs. Finally, the preparation of a PCID involves creating a PCID circuit where the PPy side is fully attached to the flexible conductive cobalt-nickel alloy cloth, while the P(AAm-co-AAc) side is partially attached to cobalt-nickel alloy cloth. Moreover, to verify the rectification effect and eliminate the influence of the Hofmeister effect on energy harvest, single-layer P(AAm-co-AAc) and P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl were also prepared as controls31. Different ratios of acrylamide (AAm) and acrylic acid (AAc) in P(AAm-co-AAc) and variable deposition times of PPy were considered to analyze the impacts of H+ concentration, diffusion properties, and the thickness of PPy respectively. Finally, the naming of all samples is detailed in Supplementary Table 2.

The asymmetric structure is exhibited by the cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) images of freeze-dried P(AAm-co-AAc) hydrogel/PPy films (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1). The enrichment of Cl elements on the PPy side in EDX elemental mapping images proves the positively charged characteristics of the PPy networks (Fig. 1b). As the deposition time of PPy increases, its thickness gradually grew from 6.73 μm (1,200 s) to 12.65 μm (1800 s) and 15.06 μm (2400 s). Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) is employed for studying the chemical structure of PCIDs and for further analyzing the contrasting moist response properties between the GPE and PPy sides (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. 2). The absorption band at 3259 cm−1, 2931 cm−1 and 1028 cm−1 can be attributed to the stretching vibration of -OH, C-H and C-O, respectively32. Notably, in the FTIR spectra of AAm containing PCID, no characteristic peak of N-H bending vibration can be observed, whereas the stretching vibration peak of C = O shifts to 1655 cm−1, proving the formation of (C = O···H-N) type hydrogen bonds in P(AAm-co-AAc)33. On the PPy side, only low-intensity broad stretching vibration peaks of C-C and C-N in the pyrrole rings appeared at 1465 cm−1 and 1583 cm−1, respectively, mainly due to the high crystallinity of electrochemically deposited PPy, which drastically restricts molecular mobility. Moreover, a series of sharp noise absorption peaks within the range of 1900–2300 cm−1 and a wide absorption band at 650 cm−1 are all attributed to the abundant adsorbed water in the GPE34, which are extremely weak in the PPy side, confirming the strong hydrophilicity of GPE and the hydrophobicity of PPy. This difference in chemical structure and hydrophilicity provides the necessary conditions for the diffusion of ion gradients and the establishment of ions concentration differences in PCID.

As shown in Fig. 1e, taking MC100-2 as an example, the coupled electromagnetic-moist interaction performance is preliminarily verified using the open circuit voltage (VO)35. Within 60 s, the VO value of MC100-2 stabilized at 0.31 V, attributed entirely to the harvest of moist energy. Subsequently, under 0.1 Hz EMW radiation, VO continued to rise steadily, attributing to the harvest of electromagnetic energy. However, after about 300 s of continuous radiation, the VO value gradually stabilized at a constant value (0.59 V), indicating that the PCID’s harvesting of electromagnetic energy tended to saturate, thus validating its energy storage capability. After 2460 s, the EMW radiation was withdrawn, the VO value gradually decreased, indicating that electromagnetic energy stored in the PCID device was slowly released. This study confirms the capability of synergistically harvesting and storing both ambient moist energy and electromagnetic energy.

Coupled electromagnetic-moist performance

First, the rectification behaviors of homogeneous P(AAm-co-AAc) and heterogeneous P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy are investigated by testing the differentiated forward and reverse conduction capabilities of the GPE and PPy sides respectively. As shown in Fig. 2a, the forward DC resistance (RF) values of the P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy samples are much smaller than the reverse DC resistance (RR) values, indicating that they had an excellent ionic rectification effect. In contrast, the P(AAm-co-AAc) and P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl samples do not exhibit such behavior (Supplementary Figs. 3–6)36. Owing to the asymmetry in surface charge polarity caused by different chemical components, ion channels in the film will reject similarly charged ions and attract counterions37. Results indicate that, in the P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy system, the migration of cations (H+, K+) from the GPE side to the PPy side, and the migration of anions (Cl-) from the PPy side to the GPE side, are permissible as they complement the kinetics driven by concentration gradients and osmotic pressure (Fig. 2c)38. However, the movement of charge carriers in the opposite direction is impeded. This diode-like rectifying effect is further evaluated by the rectification ratio (RR/RF)39. As shown in Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 3, all rectification ratios of P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy significantly exceeded those of pure P(AAm-co-AAc) and P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl, indicating that the augmented rectification effect in P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy predominantly arose from the function of PPy as a proton-collecting layer, rather than the Hofmeister effect of KCl. It is worth noting that as the proportion of the AAc component in P(AAm-co-AAc) increases, the rectification ratio of P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy gradually decreases, which can be attributed to the increase in H+ concentration. Recently, three kinds of ionic diodes have garnered significant attention: electrolyte heterogenous films with asymmetric structures27, nanofluidic diodes based on nanopore structures and surface charge distribution40, and diodes based on electrolyte solution concentration gradients41 (Supplementary Table 4). In comparison, nanofluidic diodes and concentration gradient diodes exhibited superior ionic rectification effects, but their rigid structures and stringent requirements, such as the need for precise concentration gradients, limited their practicality in real applications. Moreover, the great MEG and EMW absorption potential make electrolyte heterogenous films type P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy an ideal candidate for coupled electromagnetic-moist energy harvesting.

a DC resistance of P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl, and P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 60,000). b Rectification ratio of P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl, and P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy. c Schematic illustration of the diode-like rectifying behavior of PCIDs. VO values of d P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl and e P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy without EMW radiation. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 60,000). f IS values of P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy without EMW radiation. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 600,000). g VO and h IS values of P(AAm-co-AAc) under different frequencies of EMW radiation. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 60,000). i VO values of MC100-2 under different frequencies of EMW radiation. VO values of j P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl and k P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy with 100% AAc under different frequencies of EMW radiation. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 60,000). l VO and IS values of MC75-2 under tunable RH without EMW radiation. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 60,000). m VO and IS values of MC75-2 under tunable temperature and different frequencies of EMW radiation. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 60,000).

To comprehensively study the coupled electromagnetic-moist performance of PCIDs, a systematic investigation is conducted on the electrical output performance of PCID under the influence of moisture alone as well as the simultaneous action of moisture and EMW. Under stable relative humidity (RH) conditions (RH = 60%, 23.5 °C), pure P(AAm-co-AAc) exhibited poor electrical output properties, regardless of the proportion of AAc, of which VO value was consistently less than 0.1 V, and the short circuit current (Is) value was at the nA level (Fig. 2g, h, Supplementary Figs. 7, 11). Nonetheless, with the proportion of AAc increasing from 0% to 100%, the VO and IS value of P(AAm-co-AAc) increased by 1,609.2% and 2,698.7%, respectively, indicating that the MEG performance of P(AAm-co-AAc) was primarily attributed to the release of H+ from carboxyl groups. As shown in Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 8, with the increase in immersion time of KCl solution, the VO value of P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl instead decreased, which indicated that the introduction of K+ could interfere with the establishment of the concentration gradient of H+.

When PPy was deposited, both the VO and IS of P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy are dramatically improved, and their stability over time was also improved as the much smaller standard deviation as compared to P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 9). With the increase in deposition time of PPy, for P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy containing 75% AAc, there was a tendency for the VO value to increase, suggesting that the role of PPy as an H+ storage layer gradually became more pronounced with increasing thickness. Notably, for pure PAAc/PPy, the VO value of MC100-3 was smaller than that of MC100-2, which may be ascribed to the too dense PPy with exceeding deposition, in which the ion migration channels will be limited. However, for P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy containing lower amounts of AAc (0%, 25%, 50%), there is a decreasing trend in the VO value, which can be attributed to the shielding effect of K+ on low concentrations of H+ that still plays a major role. More importantly, the deposition of PPy significantly increased the IS value by several orders of magnitude compared to P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl, particularly for samples with a high AAc ratio (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Fig. 13). Among them, the IS value of MC75-2 reached 0.80 μA, which is 36,412 times higher than that of MC75-K2 (21.97 pA), suggesting that the diode-like rectifying effect of PCIDs is a necessary condition for stable output DC (Supplementary Fig. 15). In addition, when the deposition amount of PPy is the same, the increase in AAc content significantly increases the IS value, which can be mainly ascribed to the increase in H+ concentration. In this case, it can be preliminarily speculated that the rectification effect is not only indispensable for establishing the potential difference but also a necessary condition for DC current output, while the carrier concentration is related to the intensity of current output.

Under EMW excitation, the VO and IS values of PCIDs were significantly improved. As shown in Fig. 2g, h, the VO and IS values of P(AAm-co-AAc) have significantly improved with the interaction of EMW, while the changes of pure PAAm are negligible, confirming H+ as the pivotal carrier for facilitating the mutual coupling of moist response and EMW absorption. The function of EMW displayed dependency on both frequency and time (Supplementary Fig. 7). In the presence of low-frequency EMWs, H+ ions undergo periodic migration within the electrolyte, resulting in periodic fluctuations in the VO. As the frequency of EMW progressively increased, a delay emerged between the migration-induced polarization of H+ ions and the oscillation of the electric field vector. This ultimately led to a reduction in the amplitude of VO fluctuations, causing the potential difference across the films to approach a stable equilibrium. In the circuit, the IS values of P(AAm-co-AAc) gradually transformed from AC output to DC output under the excitation of EMW (Supplementary Fig. 11), revealing that EMW can enhance its rectification effect and amplify the moist performance.

After the Hofmeister effect treatment of KCl, the VO and IS values of PAAm/KCl increased, whereas those of P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl with a higher AAc proportion decreased (Supplementary Figs. 8,12,14,15). This is attributed to the introduction of K+ and Cl- ions, which facilitated free charge carriers within PAAm, thereby enhancing its charge migration polarization ability. However, these ions weakened the rectification effect of P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl with a high AAc proportion, resulting in a diminished capability to harvest electromagnetic energy. In instance, for PAAc/KCl (Fig. 2j), as the KCl infiltration time increased, its VO value under 1000 Hz radiation decreased from 0.66 V (1,200 s) to 0.42 V (1800 s) and 0.08 V (2400 s), while their IS value decreased from 10.72 nA (1,200 s) to 0.51 nA (1800 s) and 1.96 nA (2400 s). Although both the moist-driven DC outputs of P(AAm-co-AAc) and P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl can be achieved under EMW radiation, their weak intensities still limit their practical applications.

Here, PCIDs composed of P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy, which exhibit stronger rectification effects, are verified to possess enhanced moist and electromagnetic synergistic energy harvesting capabilities. Under EMW radiation, the VO and IS of all P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy were increased (Supplementary Figs. 9, 13–15). For example, as depicted in Fig. 2i, k, with the increase in radiation frequency, the VO value of MC100-2 rose from 0.34 V without radiation to 0.51 V at 10,000 Hz, of which fluctuation amplitude also gradually decreased due to polarization relaxation, demonstrating a more stable potential difference. Compared with VO, the enhancement effect of EMWs on the IS of PCIDs is relatively weaker, which may be attributed to the changes in the impedance and capacitance of the materials, as well as other electrolyte and dielectric properties, with varying radiation frequencies. The IS value of MC100-2 increased from 0.54 μA without radiation to 0.59 μA at 100 Hz. Moreover, the EMW frequency corresponding to the maximum values of VO and IS gradually shifted towards higher frequencies with increasing AAc content. For instance, the IS of MC0-3 reached its maximum value of 0.045 μA at 0.1 Hz, while the IS of MC100-3 reached its maximum value of 0.65 μA at 100 Hz, which indicated their optimal electromagnetic-moist coupling effect under EMW radiation at 0.1 Hz and 100 Hz.

Futhermore, the practical availability of the coupled electromagnetic-moist performance of PCIDs is successfully validated under various environmental conditions, including different RH levels and temperatures. Taking the PCIDs sample (MC75-2) with the best DC discharge capability under indoor temperature and RH as the research object, the VO values without radiation was basically not affected by RH (Fig. 2l). Subsequently, under EMW radiation, higher RH levels caused MC75-2 to exhibit stronger polarization intensity, thereby more effectively enhancing the VO value (Supplementary Fig. 16). As shown in Fig. 2l and Supplementary Fig. 17, MC75-2 displayed higher IS values at increased RH levels, which indicated that higher RH promoted the ionization of H+, resulting in greater ionic conductivity. At an RH of 90%, the IS value of MC75-2 reached 6.60 μA under 1 Hz EMW radiation (Supplementary Fig. 18). As shown in Fig. 2m and Supplementary Figs. 19–21, higher temperature was beneficial to both VO and IS values, which can be attributed to the improved ion mobility and dielectric polarization. Especially, at 50°C, the IS value of MC75-2 reached 11.45 μA under 0.1 Hz EMW radiation.

To study the long-term stability of PCIDs, we measured the IS of MC75-2 on the first day and after one week of continuous operation, with each testing session lasting 12 h. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 22, the results demonstrated that after one week, the IS value (0.75 μA) still maintained 95.1% of its initial value recorded on the first day (0.79 μA). This indicated that the PCIDs exhibited excellent stability over time and suggested a reliable lifetime for the device under continuous operation. The consistent electricity generation and discharge performance also implied that the redox reactions did not significantly affect the lifetime of the device.

In this case, a strong coupling between moist and EMW absorption of PCIDs can be built, promising optimistic prospects for the development of high-efficiency dynamic energy-switching carriers. On one hand, the moist-induced diode-like rectifying effect endows PCIDs with electromagnetic energy harvesting capabilities; on the other hand, EMW radiation alters the motion and polarization modes of charge carriers within PCIDs, enabling the modulation and enhancement of moist-enabled ionic current while absorbing EMW.

Insights into the coupled performance

Since the EMW absorption and moist response mechanisms are respectively affected by the dielectric and electrolyte properties, the above electromagnetic-moist coupling mechanism is deeply analyzed and verified based on the dielectric and electrolyte properties of PCIDs (Fig. 3). Figure 3a shows the generation of the primary charge carrier H+. With the increase in AAc proportion, the concentration of H+ significantly increased, indicating that P(AAm-co-AAc) can successfully adsorb H2O molecules from the air and induce the ionization of COOH groups. As the immersion time of the KCl solution increases, the concentration of H+ in P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl gradually increases owing to the Hofmeister effect, which promotes the hydrophilicity of the polyelectrolyte. It is worth emphasizing that after the deposition of PPy, the surface H+ concentration of P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy exhibits a significant decrease. This confirms that PPy, playing a role as a cationic accommodation layer, effectively facilitates the migration of H+ from P(AAm-co-AAc) to PPy, thereby inducing an asymmetrical distribution of H+ and forming a potential difference.

a H+ concentration on the surface of P(AAm-co-AAc), P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl and P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 5). b Equivalent circuit model for EIS fitting and interface charge distribution model of PCIDs under alternating electric fields. c ionic conductivity of P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl and P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy. d D values of P(AAm-co-AAc), P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl and P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy. e Rct values of P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy. f Simulated induced potential distribution profiles of MC100, MC100-K2, and MC100-2 under different frequency radiation along the normal direction. g Simulated surface potential difference along the normal direction under radiation of different frequencies for MC100, MC100-K2, and MC100-2, and the ɛr value of MC100-2 under radiation of different frequencies.

Based on the electrical equivalent circuit and charge distribution model in Fig. 3b, the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS, Supplementary Figs. 23–28) is fitted to investigate the transfer properties of charge and mass. As a double-layer electrolyte, under the manipulation of alternating electric fields, the movement of charge carriers is mainly affected by Ohmic resistance (RΩ), Faraday effect (Zf), and ionic double layer (IDL) response42.

The higher ionic conductivity of P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl compared to that of P(AAm-co-AAc) illustrates that the introduction of free charges such as K+ and Cl- can reduce the RΩ of the polyelectrolyte (Fig. 3c). With the increase in AAc proportion, the ionic conductivity of P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl first decreases and then increases. This trend occurred because KCl not only introduced new charge carriers K+ and Cl-, but also decreased the swelling of P(AAm-co-AAc) molecular chains and compressed the ion transport channels. Additionally, copolymers like MC50, due to the simultaneous effect of NH2 and COOH, are more prone to forming intermolecular hydrogen bonds, hindering carrier transport and exhibiting lower ionic conductivity. P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy demonstrated the boosting ionic conductivity, primarily due to the conjugated structure of PPy, which imparted electronic conductivity characteristics, allowing PPy to act as a transition layer between the ionic conductive GPE and the electrode. Ultimately, the stronger current output and higher IS value of PCIDs are determined by the high H+ concentration and abundant ion channels.

The mechanism of Faraday reaction of GPE is analyzed from the perspectives of mass transfer and charge transfer. To study mass transfer, the diffusion coefficient (D) of H+ is calculated (see details in Supplementary Note 1). As is shown in Fig. 3d, the D values of all systems, including P(AAm-co-AAc), P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl, and P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy, increase with the AAc proportion, indicating that the increase in the proportion of COOH groups and the decrease of amino groups in the GPEs hinder the migration and diffusion of H+. Generally, COOH exhibits a stronger electronegativity than NH2 in same environment, indicating a greater affinity for H+ binding. As a result, this slows down the transfer rate of H+ from the side of P(AAm-co-AAc) ionized by moisture contact to the other side, thereby limiting the ion concentration difference across the membrane, which consequently accounted for the lower VO values observed in generators with higher AAc content. The charge transfer capability is analyzed through the charge transfer resistance (Rct) values, which is primarily attributed to the contact resistance43. As is shown in Supplementary Fig. 32a, a high proportion of AAc is accompanied by a lower Rct value, which means that an increase in H+ concentration was beneficial to charge transfer. However, the introduction of K+ and Cl- for 1200 s instead increases the Rct value of GPEs (Supplementary Fig. 32b), owing to the shrinkage of charge channels. When PPy is deposited onto one side of P(AAm-co-AAc), in the circuit of P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy, there exists Rct formed not only between GPE and the electrode interface (Rct,1), but also between PPy and GPE interface (Rct,2). Simultaneously, the unique electrolyte property is able to simultaneously release and accept two types of charge carriers, ions and electrons, which not only makes the resistance between PPy and the conductive electrode negligible but also effectively reduces the Rct,2 value (Fig. 3e).

To further analyze the charge transfer properties at the heterointerface, a typical capacitor-type IDL model is studied by the the complex capacitance (C(ω) = C’(ω) + jC’’(ω)), of which the real part (C’(ω)) and the imaginary part (C’’(ω)) represent energy storage and release, respectively (see details in Supplementary Note 2). Compared to single-layer P(AAm-co-AAc) and P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl-based GPEs (Supplementary Figs. 34, 36), the C(ω) of double-layer P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy is significantly larger (Supplementary Fig. 38), particularly at relatively higher frequencies, confirming the superior energy storage and release properties of the P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy44. The enhanced interfacial capacitance effect of P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy is attributed to the IDL, not only at the GPE/electrode interface (Cd1) but also at the PPy/GPE interface (Cd2). Furthermore, the higher the AAc proportion in P(AAm-co-AAc), the higher the corresponding frequency value of the maximum C’’(ω), indicating that a higher concentration of H+ is associated with shorter relaxation times, which implies faster reversible charge-discharge kinetics. At the same time, further deposition of KCl also has a similar effect. Moreover, the C’’(ω) of P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy is almost always greater than C’(ω) at any frequency, confirming its stronger IDL properties and wider effective electric field response frequency. Moreover, taking MC75-2 as an example, the charge-discharge properties of PCIDs as capacitors are also studied through galvanostatic charge-discharge test (see details in Supplementary Note 2). The excellent energy storage, power delivery and stability enable it a promising candidate for alternative solution for energy storage.

The dielectric properties of the PCIDs are investigated using the complex permittivity (ɛr = ɛ’ - jɛ’’ ), where the real part (ɛ’ ) and imaginary part (ɛ’’ ) correspond to the storage and attenuation capacities of dielectric energy, respectively45. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 40,42,44, the ɛr values of all samples decrease with increasing alternating electric field frequency, which illustrates that the migration polarization of free charge carriers (H+, K+, Cl-, etc.) in GPEs and the interfacial polarization effect gradually weaken under high-frequency alternating electric fields46. Simultaneously, high-frequency electric fields can stimulate the movement activity of dipoles and electrons in polar polymers (including P(AAm-co-AAc) and PPy), thereby enhancing their conductivity, which also explains the decrease in electrolyte impedance with increasing frequency (Supplementary Figs. 33,35,37).

To further verify the coupled electromagnetic and moist mechanism according to above dielectric and electrolyte properties, a finite element analysis (FEA) model based on the typical coupled Poisson and Nernst–Planck (PNP) equation is carried out (see details in Supplementary Note 3)41. H+ is regarded as the primary ionic charge carrier inducing the potential gradient distribution. Therefore, the H+ concentration and the corresponding D value obtained from testing are utilized as boundary conditions and the transfer properties of free ions for FEA simulations. Crucially, different materials demonstrate diverse capacities for storing and attenuating electromagnetic energy under varying frequency EMW. Consequently, they exhibit distinct εr values, determining the theoretical validation of the coupling process of electromagnetic-moist coupling based on the Poisson equation38. Consistently, under EMW radiation, the simulated potential difference on opposite sides of PCIDs follows the following pattern: MC100 > MC100-K2 > MC100-2 (Fig. 3f, g), showing a similar law to the measured VO values presented in Fig. 2j–l. This result further confirms the stronger charge migration polarization ability of single-layer film samples (P(AAm-co-AAc), P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl) under the excitation of alternating electric fields, leading to stronger potential differences in these films under open-circuit conditions. In contrast, the bilayer film samples, due to their stronger dielectric capacitance, exacerbate the more storage of electromagnetic energy, hence reducing the apparent VO value. Additionally, as the frequency increased, the gradually decreasing εr of PCIDs also corresponds to their gradually increasing simulated potential difference (Fig. 3g), which further confirms that the dielectric energy storage capability is inversely related to the surface potential difference. Nevertheless, the simulated values at low frequencies are still slightly lower than the measured VO values. This discrepancy may be mainly due to the micro-interface polarization and interfacial micro-capacitance effects that are hard to incorporate in the FEA. Therefore, Density Functional Theory (DFT) analysis at the molecular level is subsequently employed to further refine the analysis of the electromagnetic-moist coupling mechanism, which facilitates the explanation on the contribution of electromagnetic energy harvested through interfacial polarization relaxation to electricity generation.

Energy conversion, harvesting, and interaction

The output power density (Pden) of PCIDs under variable frequency EMW radiation is tested by connecting with a load resistance (1 MΩ) in series (see details in Supplementary Note 4)47. Under moist conditions alone, P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy with a higher proportion of AAc tends to demonstrate a higher Pden, while increased PPy deposition also proves advantageous for energy output (Supplementary Fig. 48,49). Benefiting from the abundance of H+ ions and their higher migration activity, MC75-3 achieved a Pden value of 0.46 mW·m-2 solely under moist dominance. It is worth noting that under tunable frequencies of EMW radiation, the Pden value of P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy increased to varying degrees, which can be attributed to the simultaneous harvesting of ambient moist energy and electromagnetic energy. Taking PAAm/PPy with the highest rectification ratio as an example, the Pden values of MC0-3 under EMW radiation ranging from 0.1 Hz to 10,000 Hz reached 107.8%, 105.4%, 119.1%, 127.6%, 149.1%, and 176.4% compared to the non-radiated state (Fig. 4a, b). The Pden value of MC75-3 reaches 0.49 mW·m-2 under EMW radiation of 10,000 Hz. Moreover, it can be statistically deduced that the Pden value of PCIDs is positively related to the tanδɛ (ɛ’’ / ɛ’ ) value, which represents the energy attenuation capacity of incident EMW (Fig. 4c, d, Supplementary Figs. 52, 53). This phenomenon further confirms that part of the electromagnetic energy absorbed by PCIDs was converted into electrical energy. During this process, the increase in DC power output under EMW was not only contributed to the enhanced efficiency of moist-enabled electricity generation, but also the synergistic harvesting of ambient moist potential energy and electromagnetic energy. The radiation-to-DC power conversion efficiency (ηrad-DC) is further evaluated (see details in Supplementary Note 4). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 54, most PCIDs show increasing ηrad-DC values with the increase of radiation frequency, indicating that the impedance of the receiving antennas of the PCIDs tends to match at relatively higher frequencies. Especially, a peak ηrad-DC value of 25.74% was recorded at 100 Hz by MC50-2, revealing its optimal electromagnetic energy harvesting performance.

a Pend values of MC0-3 under different frequencies of EMW radiation. b Pend values of PAAm/PPy under different frequencies of EMW radiation. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 60,000). c Tanδε values of PAAm/PPy under different frequencies of EMW radiation. d Dependence between Pend and tanδε values of PAAm/PPy. e Schematic of the energy conversion and harvesting mechanism. f Differential charge density mapping of the P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy heterointerface. g DOS plots of P(AAm-co-AAc), PPy, and P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy. h Schematic of the interfacial polarization mechanism. i. Schematic of the ion gradient distribution construction mechanism. j Schematic of the diode-like rectifying effect. Cole-Cole plots of k PAAm/KCl and l PAAm/PPy. m Maxwell capacitance of MC100−2 under D10000Hz radiation. n Spatial charge distribution in MC100-2 at n1 initial state, n2 0.025 ms, n3 0.05 ms, n4 0.075 ms, n5 0.1 ms. Digital photos of integrated PCID device with o1 no radiation, approaching o2 a hand, o3 mobile phone, and p real-time dynamic changes in electric signals.

The electromagnetic-moist coupled wireless energy interaction mechanism manipulated by diode-like rectifying engineering is analyzed by both practical characterization and theoretical simulation. The energy conversion and harvesting mechanism in PCIDs are comprehensively analyzed by performing dielectric polarization characterization and energy simulation under alternating electric fields.

Practically, based on the Debye relaxation theory (see details in Supplementary Note 5), the Cole-Cole plots of P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy exhibit a more semi-circular shape, whereas the ε’’ and ε’ values of P(AAm-co-AAc) and P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl show close linear correlation (Fig. 4k, l, Supplementary Figs. 46, 47). This demonstrates the outstanding polarization relaxation capacity of P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy, while the electromagnetic loss of P(AAm-co-AAc) and P(AAm-co-AAc)/KCl is solely attributed to conductive loss48. With EMW, the polarization relaxation effect and diode-like rectifying effect in PCIDs will synergistically enhance the harvesting of moist energy and electromagnetic energy. On one hand, the concentration difference and osmotic pressure induced by surface moist cause the orientation movement and initial separation of heterogeneous charges in PCIDs (Fig. 4i). This not only triggers the ionic rectification effect but also promoted the construction of the IDL between GPE and PPy, serving as the primary site for interfacial polarization relaxation. On the other hand, during the interfacial polarization process, the periodic aggregation, separation, and rearrangement of spatial charges in the IDL depend on the energy of the incident EMW, which make the PCIDs more efficient in absorbing EMW, thereby enhancing their rectification effect and DC output performance. Additionally, the separated charges in the IDL can form a built-in electric field (BIEF), which contributes to the construction of heterointerface micro-capacitance, providing “storage space” for electromagnetic energy absorbed based on interfacial polarization, once again explaining the superior C(ω) value of PCIDs than pure GPEs49.

Theoretically, the dynamic energy conversion and transfer behaviors in PCIDs under EMW excitation are studied through the FEA based on a typical capacitor model. The spatial charge resonance phenomenon in PCIDs and the polarization process are examined by incorporating an electric displacement field (Di, see details in Supplementary Note 6)50. Using MC100-2 as an example (Fig. 4n and Supplementary Video 1), the potential underwent periodic changes and rearrangements by performing D10000Hz with a characteristic frequency of 10,000Hz. As is shown in Fig. 4m, the periodic resonance of the derived Maxwell capacitance substantiates the periodic absorption (0–0.025 ms, 0.075–0.125 ms, 0.175–0.2 ms) and release (0.025–0.075 ms, 0.125–0.175 ms) of electromagnetic energy51. Subsequently, by the rectification effect, a portion of the absorbed energy will be used to drive the separation of charges. During this process, the reciprocating motion of the carriers will be unidirectionally hindered by the FE, accelerating the movement of H+ towards the PPy side while impeding the movement towards the GPE side, ultimately converting the wireless electric field energy into direct current energy, which is completely consistent with the mechanism hypothesis proposed in design phase. Additionally, the charge behavior and interfacial polarization mechanism in PCIDs are microscopically further investigated through DFT, conducted by a chain segment model of P(AAm-co-AAc) and PPy at the interface52. Owing to variances in energy band structures, electrons spontaneously will diffuse across heterointerfaces, leading to their redistribution until equilibrium Fermi levels are attained on both sides53. As shown in Fig. 4f, an electron-deficient region (red) and an electron-rich region (blue) are respectively formed at the P(AAm-co-AAc) and PPy sides, attributed to the robust π-conjugated structure of PPy, which facilitates the establishment of a BIEF within the spatial charge delocalization zone extending from P(AAm-co-AAc) to PPy. The negatively shifted conduction band and abundant electron states in the valence band in the total orbital density-of-states (DOS) curves demonstrate heightened electron excitability (Fig. 4g), consequently amplifying the responsiveness to EMW and boosting interfacial polarization (Fig. 4h)54.

Based on the above analysis, as depicted in Fig. 4e, the electromagnetic-moist coupled wireless energy interaction mechanism of PCIDs can be summarized as follows:

i) The chemical potential difference between adsorbed H2O and gaseous H2O molecules drives the adsorption of H2O molecules on hydrophilic GPE surface, COOH dissociation, and H+ diffusion, which triggered the gradient distribution of H+ and futher the potential gradient distribution.

ii) On one hand, the potential difference induced by the aforementioned ions gradient distribution can directly drive the external DC output to achieve electrical energy. On the other hand, the ions and potential gradient distribution ensures the diode-like rectifying effect of PCIDs.

iii) Under the driving force of electromagnetic energy, the ionic diode properties will play three roles. First, the charge carriers, such as H+, in the ionic diode will be orientationally migrated by the alternating electric field, amplifying the ions gradient distribution in process. Secondly, according to transmission line theory, electromagnetic energy will be directly converted into electric field energy attributed to the unidirectional conduction characteristic (Fig. 4j), driving the internal DC in ionic diodes. Thirdly, the heterointerface between GPE and PPy performs a pronounced interfacial polarization relaxation effect, leading the constructed BIEF to act as a microcapacitor, further enhancing the harvesting efficiency of electromagnetic energy.

iv) Ultimately, the chemical potential energy of ambient gaseous water molecules and the energy of EMW will be synergistically harvested and converted into DC electrical energy. Furthermore, the harvesting processes of these two forms of energy are strongly coupled and mutually reinforced.

Ultimately, given the coupled electromagnetic-moist responsiveness, along with ionic diode and capacitor attributes, the proposed wireless energy interactive system will unleash unprecedented potential in fields such as AIoT equipment, information encryption, smart homes, wireless charging, and self-powered radiation monitoring, etc. A 4×5 array integration device is fabricated onto a flexible fabric. As depicted in Fig. 4o, p and Supplementary Video 2, when a mobile phone, acting as a radiation source, approached the PCID system from a distance, its response voltage signal increased from 1.89 V to 2.72 V. Once the radiation source moved away, the signal gradually returned to its original value. As a comparison, when a hand that does not emit electromagnetic radiation was brought close to the system, there was no obvious electrical signal. Therefore, with utilizing the extracted moisture and electromagnetic energy by PCID-based wearable devices, it is highly feasible to monitor and visualize electromagnetic signals emitted by radiation sources, such as mobile phones and laptops, through real-time dynamic changes in VO values. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 55, the incomplete digits displayed on the electronic clock under non-radiative conditions confirmed the DC output capability of this PCID under ambient environment, while the EMW radiation drove the normal operation of the electronic clock, confirming the successful synergistic harvesting of moist and electromagnetic energy. Therefore, the extracted energy can be directly utilized to power low-consumption wearable sensors. Additoinally, although the as-prepared PCIDs can dynamically harvest energy from ambient moisture and electromagnetic radiation in real time and convert it into electrical energy, their energy storage capacity still has significant potential for optimization. Thus, using PCIDs to charge commercial energy storage devices, such as batteries or capacitors, can not only prevent energy waste but also further expand the application scenarios for the harvested energy. Moreover, we propose an intelligent environment adaptive control system based on an electromagnetic-moisture coupled wireless energy interactive mechanism, which could promote green development and harmonious symbiosis between humans and nature (Supplementary Fig. 56). Therefore, this work not only proposes a novel wireless electromagnetic-moist energy interactive system with systematical operational physical mechanism investigation, but also develops a dynamic energy-switching carrier based on flexible diode films to achieve integrated energy harvest, conversion, storage and releasing, thereby advancing sustainable development and industrial upgrading in the fields of environment and energy.

Discussion

In summary, we carry out a fundamental study on the wireless, chipless coupled interaction between electromagnetic and moisture energy interaction with the regulation of ionic diodes effect. Further, we have developed an electromagnetic-moist coupled wireless energy interactive system based on P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy PCIDs to synergistically harvest electromagnetic and moist energy. This energy interaction mechanism allows the all-in-one device integration of antenna, rectifier, capacitor, etc. Using the diode-like rectifying effect induced by moist as a bridge, a coupling effect is established between moist-enabled electricity generation and electromagnetic energy harvesting. The wireless energy interactive mechanism is discussed in depth by manipulating the electrolyte and dielectric properties of PCIDs. We simultaneously elucidate the frequency dependence of this coupling effect, revealing that stronger interfacial polarization and charge migration relaxation were associated with higher energy conversion. Especially, the ηrad-DC value of MC50-2 reached 25.74% under 100 Hz EMW radiation. Finally, based on both experimental and theoretical analysis, a physical mechanism model of the energy harvesting, conversion and storage process in this system is established. Future efforts will seek to experimentally improve the rectification ratio and EMW absorption efficiency of polymer diodes while developing electronic systems that operate efficiently under EMW in wider frequency bands such as radiofrequency waves and microwaves. We anticipate that our wireless energy interactive system will help to enable future self-powered radiation monitoring, wireless charging, and information encryption, for automated and intelligent electromagnetic stealth and protection.

Methods

Synthesis of P(AAm-co-AAc) hydrogel

The P(AAm-co-AAc)/PPy organohydrogel heterogeneous films were prepared by a two-step method. First, 4 g of monomers AAm and AAc, 40 mg of UV initiator 2-Hydroxy-4’-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-2-methylpropiophenone, and 40 mg of cross-linking agent bisacrylamide were evenly mixed and dissolved into 20 ml of deionized water. The above prepolymer solution was transferred to a polytetrafluoroethylene mold covered with FTO conductive glass (depth 1 mm, conductive side facing down), and placed under a UV lamp with a wavelength of 365 nm to initiate free radical polymerization. After 1 h, a P(AAm-co-AAc) hydrogel adhered to the FTO conductive glass will be obtained. Furthermore, a series of P(AAm-co-AAc) hydrogels with different mass ratios of AAm and AAc were synthesized to control the concentration of H+ in the gels.

Preparation of P(AAm-co-AAc) hydrogel/PPy

Afterward, a three-electrode system was employed for the in-situ electrochemical deposition of PPy, with the FTO conductive glass adhered with P(AAm-co-AAc) hydrogel serving as the working electrode, an Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference electrode, and a platinum plate as the counter electrode. This configuration allowed for the precise manipulation and deposition of PPy. The concentration of KCl in the electrolyte solution is 0.5 M, while the concentration of monomer Py is 0.2 M. The galvanostatic method was used to ensure the stable progress of Py electrochemical deposition, with the current density being 30 mA·cm-2. Finally, PPy was uniformly deposited between P(AAm-co-AAc) and PPy, and the gradually increased deposition time (1,200 s, 1,800 s, 2,400 s) enabled PPy deposition with controllable thickness.

Preparation of P(AAm-co-AAc) organohydrogel/PPy PCIDs

The prepared P(AAm-co-AAc) hydrogel/PPy was infiltrated in a glycerol/deionized water mixture for 20 min to introduce glycerol molecules into the gel system and remove unpolymerized Py molecules, and finally obtained P(AAm-co-AAc) organohydrogel/PPy. For control purposes, the pure P(AAm-co-AAc) organohydrogel was similarly fabricated through infiltration in a glycerol/deionized water mixture. Additionally, the P(AAm-co-AAc) organohydrogel/KCl control group was effectively prepared by infiltration in a solution containing 0.5 M KCl along with the glycerol/deionized water mixture. Finally, the nomenclature of all prepared samples can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Construction of PCID based energy harvesters

As shown in Fig. 1f, energy harvesting units were prepared by sandwiching a 1.5 cm * 1 cm rectangular PCID film between a pair of copper-nickel alloy cloth electrodes (type: CEF−1, purchased from Suzhou Meisiyang Electronic Materials Co., Ltd.), with PPy being fully covered, while a 1 cm2-sized P(AAm-co-AAc) organohydrogel was exposed to the ambient environment. An integrated energy harvesting device was prepared by connecting above units in series (5 times) and in parallel (4 times) alternately.

Characterizations

A Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR, Nicolet 6700, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was employed to study the chemical structure. The micromorphology and interface structure of the film were characterized by field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Tescan VEGA3) equipped with EDX. An electrometer (Keithley 6514 system) was utilized to measure the DC resistance, VO, IS and Pden values. A pH tester (98109, Lianchuang) was used to detect the H+ concentration on the GPE surface. The carrier transport and impedance characteristics of the electrolyte were studied using a CHI660E electrochemical workstation. εr and tanδε values were tested by a wideband frequency dielectric spectrometer (Novocontrol Concept 50). The sine wave (DP-BT) was generated by a Schumann-type multi-state frequency-adjustable signal generator (Dongpeng Electrical Technology Co., Ltd.). As shown in Supplementary Figs. 57, 58, the PCIDs film unit was employed as receiver and placed in parallel at a distance of 5 mm from the antenna plane, where the radiated electromagnetic power density at the physical area was characterized (0.5 mW·m-2) by an electromagnetic wave radiation detector (RD630C, R&D Instruments). The study was approved by the Hong Kong Polytechnic University Institutional Review Board (No. HSEARS20230528002), and informed consent was also obtained from the volunteer (one of the authors of this paper) for wearable testing.

FEA of wireless energy interactive system

The coupled electromagnetic-moist performance and parametric potential changes over time were simulated on a COMSOL Multiphysics 5.6 software (see details in Supplementary Notes 3, 6).

Data availability

The source data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Portilla, L. et al. Wirelessly powered large-area electronics for the Internet of Things. Nat. Electron. 6, 10–17 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Human body IoT systems based on the triboelectrification effect: energy harvesting, sensing, interfacing and communication. Energ. Environ. Sci. 15, 3688–3721 (2022).

Haight, R., Haensch, W. & Friedman, D. Solar-powering the internet of things. Science 353, 124–125 (2016).

Iqbal, A. et al. Anomalous absorption of electromagnetic waves by 2D transition metal carbonitride Ti3CNTx (MXene). Science 369, 446–450 (2020).

Lv, H. et al. Insights into civilian electromagnetic absorption materials: challenges and innovative solutions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2315722 (2024).

Wang, X. X., Cao, W. Q., Cao, M. S. & Yuan, J. Assembling nano–microarchitecture for electromagnetic absorbers and smart devices. Adv. Mater. 32, 2002112 (2020).

Zeadally, S., Shaikh, F. K., Talpur, A. & Sheng, Q. Z. Design architectures for energy harvesting in the Internet of Things. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 128, 109901 (2020).

Lyu, P., Broer, D. J. & Liu, D. Advancing interactive systems with liquid crystal network-based adaptive electronics. Nat. Commun. 15, 4191 (2024).

Zhou, R. et al. Digital light processing 3d-printed ceramic metamaterials for electromagnetic wave absorption. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 122 (2022).

Han, S. et al. High energy density in artificial heterostructures through relaxation time modulation. Science 384, 312–317 (2024).

Bai, Y., Jantunen, H. & Juuti, J. Energy harvesting research: the road from single source to multisource. Adv. Mater. 30, 1707271 (2018).

Lin, S. & Wang, Z. L. The tribovoltaic effect. Mater. Today 62, 111–128 (2023).

Erkmen, F., Almoneef, T. S. & Ramahi, O. M. Electromagnetic energy harvesting using full-wave rectification. IEEE T. Microw. Theory 65, 1843–1851 (2017).

Brown, W. C. The history of power transmission by radio waves. IEEE T. Microw. Theory 32, 1230–1242 (1984).

Bharj, S. S., Camisa, R., Grober, S., Wozniak, F. & Pendleton, E. In High efficiency C-band 1000 element rectenna array for microwave powered applications. IEEE Antennas Propag. Soc. Int. Symp. 1992 Dig. 1, 123–125 (1992).

Erkmen, F. & Ramahi, O. M. A. Scalable, dual-band absorber surface for electromagnetic energy harvesting and wireless power transfer. IEEE T. Antenn. Propag. 69, 6982–6987 (2021).

Lv, H. et al. A flexible electromagnetic wave-electricity harvester. Nat. Commun. 12, 834 (2021).

Wei, X. K. et al. Progress on emerging ferroelectric materials for energy harvesting, storage and conversion. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2201199 (2022).

Gupta, R. K. et al. Broadband energy harvester using non-linear polymer spring and electromagnetic/triboelectric hybrid mechanism. Sci. Rep. 7, 41396 (2017).

Shu, J. C. et al. Molecular patching engineering to drive energy conversion as efficient and environment-friendly cell toward wireless power transmission. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1908299 (2020).

Cao, M. et al. Thermally driven transport and relaxation switching self-powered electromagnetic energy conversion. Small 14, 1800987 (2018).

Yang, W. et al. Single body-coupled fiber enables chipless textile electronics. Science 384, 74–81 (2024).

Zhao, F., Cheng, H., Zhang, Z., Jiang, L. & Qu, L. Direct power generation from a graphene oxide film under moisture. Adv. Mater. 27, 4351–4357 (2015).

Liu, X. et al. Power generation from ambient humidity using protein nanowires. Nature 578, 550–554 (2020).

Xu, T., Ding, X., Cheng, H., Han, G. & Qu, L. Moisture-enabled electricity from hygroscopic materials: a new type of clean energy. Adv. Mater. 36, 2209661 (2024).

Cao, Y., Xu, B., Li, Z. & Fu, H. Advanced design of high-performance moist-electric generators. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2301420 (2023).

Jiang, F. et al. Ion rectification based on gel polymer electrolyte ionic diode. Nat. Commun. 13, 6669 (2022).

Hu, L., Wan, Y., Zhang, Q. & Serpe, M. J. Harnessing the power of stimuli-responsive polymers for actuation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1903471 (2020).

Bao, B. et al. 3D porous hydrogel/conducting polymer heterogeneous membranes with electro-/ph-modulated ionic rectification. Adv. Mater. 29, 1702926 (2017).

Shen, D. et al. Moisture-enabled electricity generation: from physics and materials to self-powered applications. Adv. Mater. 32, 2003722 (2020).

Gurau, M. C. et al. On the mechanism of the hofmeister effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 10522–10523 (2004).

Abdel Maksoud, I. K. et al. Radiation synthesis and chemical modifications of p(AAm-co-AAc) hydrogel for improving their adsorptive removal of metal ions from polluted water. Sci. Rep. 13, 21879 (2023).

Su, J. et al. Dual-network self-healing hydrogels composed of graphene oxide@nanocellulose and poly(AAm-co-AAc). Carbohyd. Polym. 296, 119905 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Temperature-mediated phase separation enables strong yet reversible mechanical and adhesive hydrogels. ACS Nano 17, 13948–13960 (2023).

Tan, J. et al. Self-sustained electricity generator driven by the compatible integration of ambient moisture adsorption and evaporation. Nat. Commun. 13, 3643 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Sustainable power generation for at least one month from ambient humidity using unique nanofluidic diode. Nat. Commun. 13, 3484 (2022).

Matsuhisa, N. et al. High-frequency and intrinsically stretchable polymer diodes. Nature 600, 246–252 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Bilayer of polyelectrolyte films for spontaneous power generation in air up to an integrated 1000 V output. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 811–819 (2021).

So, J. H., Koo, H. J., Dickey, M. D. & Velev, O. D. Ionic current rectification in soft-matter diodes with liquid-metal electrodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 625–631 (2012).

Pérez-Mitta, G., Marmisollé, W. A., Trautmann, C., Toimil-Molares, M. E. & Azzaroni, O. Nanofluidic diodes with dynamic rectification properties stemming from reversible electrochemical conversions in conducting polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 15382–15385 (2015).

Gao, J. et al. High-performance ionic diode membrane for salinity gradient power generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 12265–12272 (2014).

Li, J., Pham, P. H. Q., Zhou, W., Pham, T. D. & Burke, P. J. Carbon-nanotube-electrolyte interface: quantum and electric double layer capacitance. ACS Nano 12, 9763–9774 (2018).

Song, H. et al. Hydrogen-bonded network enables polyelectrolyte complex hydrogels with high stretchability, excellent fatigue resistance and self-healability for human motion detection. Compos. Part B: Eng. 217, 108901 (2021).

Eskusson, J., Jänes, A., Kikas, A., Matisen, L. & Lust, E. Physical and electrochemical characteristics of supercapacitors based on carbide derived carbon electrodes in aqueous electrolytes. J. Power Sources 196, 4109–4116 (2011).

Gao, Z. et al. Tailoring built-in electric field in a self-assembled zeolitic imidazolate framework/mxene nanocomposites for microwave absorption. Adv. Mater. 36, 2311411 (2024).

Wu, F. et al. Inorganic-organic hybrid dielectrics for energy conversion: mechanism, strategy, and applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2212861 (2023).

Lu, J., Xu, B., Huang, J., Liu, X. & Fu, H. Charge Transfer and Ion Occupation Induced Ultra-durable and All-weather Energy Generation from Ambient Air for Over 200 Days. Adv. Funct. Mater. 36, 2406901 (2024).

Lan, D. et al. Impact mechanisms of aggregation state regulation strategies on the microwave absorption properties of flexible polyaniline. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 651, 494–503 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Confined magnetic-dielectric balance boosted electromagnetic wave absorption. Small 17, 2100970 (2021).

Stengel, M., Spaldin, N. A. & Vanderbilt, D. Electric displacement as the fundamental variable in electronic-structure calculations. Nat. Phys. 5, 304–308 (2009).

Hu, D. et al. Hybrid nanogenerator for harvesting electric-field and vibration energy simultaneously via Maxwell’s displacement current. Nano Energy 119, 109077 (2024).

Zhao, Z. et al. Advancements in microwave absorption are motivated by interdisciplinary research. Adv. Mater. 36, 2304182 (2024).

Fereiro, J. A. et al. A solid-state protein junction serves as a bias-induced current switch. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 11852–11859 (2019).

Bässler, H., Kroh, D., Schauer, F., Nádaždy, V. & Köhler, A. Mapping the density of states distribution of organic semiconductors by employing energy resolved-electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2007738 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would acknowledge the financial support received from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (Project No.: 1-W28T, Receiver: B.X.) for the work reported here.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.G. leaded the conceptualization, investigation, data curation and writing - the original draft; B.X. leaded the conceptualization, leaded the methodology, supervised the research work, held the funding acquisition, leaded the review & editing; Y.G., S.Z., and X.Y. contributed to materials preparation; C.F., J.L., and G.W. contributed to materials characterization; H.W. contributed to simulation and visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Gian Luca Barbruni, Hasan Ulusan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Z., Fang, C., Gao, Y. et al. Hybrid electromagnetic and moisture energy harvesting enabled by ionic diode films. Nat Commun 16, 312 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55030-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55030-2

This article is cited by

-

Harnessing the Power from Ambient Moisture with Hygroscopic Materials

Nano-Micro Letters (2026)

-

Multifunctional Three-Dimensional Porous MXene-Based Film with Superior Electromagnetic Wave Absorption and Flexible Electronics Performance

Nano-Micro Letters (2026)

-

Moist-electromagnetic coupling enabled by ionic-electronic polymer diodes for wireless energy modulation

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Nonlinear electromechanical coupling dynamics of a two-degree-of-freedom hybrid energy harvester

Applied Mathematics and Mechanics (2025)