Abstract

Micro actuators are widely used in NEMS/MEMS for control and sensing. However, most are designed with suspended beams anchored at fixed points, causing two main issues: restricted actuated stroke and movement modes, and reduced lifespan due to fatigue from repeated beam deformation, contact wear and stiction. Here, we develop an electrostatic in-plane actuator leveraging structural superlubric sliding interfaces, characterized by zero wear, ultralow friction, and no fixed anchor. The actuator features a micro-scale graphite flake in structural superlubric contact with silicon dioxide tracks, reducing friction from edge defects. Using the charge injection method, the structural superlubric actuator not only achieves a maximum relative actuation stroke of 82.3% of the flake size by applying voltage to buried electrodes—3.4 times larger than previously reported, but also enables controllable reciprocating actuation by adjusting the form of the bias voltage. Additionally, no visible wear was observed at the structural superlubric interface after over 10,000 sliding cycles, indicating robust reliability. Our work presents a design concept for micro actuators with high performance and durability, potentially guiding the development of many structural superlubric micro-devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Micro actuators typically consist of one or more movable mechanical components, with their motion governed by electrostatic, electrothermal, electromagnetic, or piezoelectric actuation mechanisms1,2, which can find extensive applications in micro inertial sensors3,4, switches5,6, resonator7,8, motors9,10, mirrors11,12 and more. As devices are scaled down to the micron or even nanometer range, the relative strengths of various forces shift, and challenges emerge due to the increased surface-to-volume ratios. Surface tension, van der Waals forces, and electrostatic forces become dominant, superseding gravity as the primary influences at these scales1. At the microscale, friction and wear at solid contact surfaces with nanoasperities present significant challenges. These issues often result in device complications, severely constraining both yield and operational lifespan.

As a result, almost all micro actuators rely on suspended beams with fixed anchors2 to prevent direct contact between two solid surfaces. However, suspended beam structures remain vulnerable to failure due to stiction following contact. Despite the development of numerous methods to prevent fabrication-induced stiction—such as surface roughening13, modifying solution-substrate wetting properties14, applying self-assembled monolayers (SAMs)15, supercritical drying16, and freeze sublimation drying. But these techniques do not address in-use stiction, which results from electric potential differences, van der Waals forces between microstructure surfaces, or cold welding of similar materials during device operation. While increasing the suspended gap between structures is a feasible way to mitigate these risks, it comes at the cost of performance, such as higher actuation voltages and slower response times in RF MEMS switches17. In addition, these suspended configurations exhibit several performance limitations. Firstly, the fixed anchor limits the stroke and movement type for micro actuators. The strain at the end of the beam is generally not more than 1% in order to avoid plastic deformation18, which restrain the relative stroke of the free beam end. As a result, the reported maximum strokes of the micro actuators below the millimeter scale is only 24.5% of the feature size19. Meanwhile, the fixed anchor would restrict beam movement, allowing the micro actuator to perform only single-direction motion, either in-plane or out-of-plane. Secondly, fatigue damage20,21 caused by repeated deformation of the beams and internal frictional resistance results in a limited lifespan and Q factor, in particular for micro inertial sensors and switches that operate for billions to trillions of deformation cycles. These challenges significantly hinder the advancement of MEMS/NEMS devices, limiting their reliability, performance, and innovative design potential.

In-plane actuators with contact interface offer a potential solution to these challenges by eliminating fatigue failure from repeated structural deformation and enabling movements such as rotation, turning, and other complex trajectories. However, in-plane actuators often face reliability and stroke limitations due to friction, wear and stiction issues. For example, the first micro-motor22 developed in 1989 suffered severe interfacial wear damage within a five-minute operational lifetime. Although various atomic-scale film technologies, such as self-assembled monolayers (SAMs)15, diamond-like carbon (DLC), and ultra nano crystalline diamond (UNCD) films1, have been employed to reduce friction and wear, their fabrication compatibility with NEMS/MEMS devices and long-term stability remain suboptimal. These challenges continue to hinder the availability of micro in-plane actuators with contact interfaces in commercial products. Therefore, innovative solutions for advanced microactuators must be pursued to tackle the challenges of interface friction, wear, and stiction through advanced configurations, designs, and materials.

Structural superlubricity (SSL) represents a state of zero wear and virtually zero friction when two solid surfaces slide in direct contact23,24,25,26,27. SSL microsystems offer effect solutions to the challenges of wear and stiction, providing an unconventional design concept for realizing micro in-plane actuator (i.e., SSL actuators). Theoretical models of SSL actuators such as gigahertz oscillators based on carbon nanotubes28,29 and in-plane electro-superlubric oscillators30,31 have been proposed. However, achieving these model actuators has not yet been realized experimentally so far. In addition to challenges in device design and fabrication, a core issue lies in the fact that while low friction in the SSL state can be achieved within the contact area, defects at the edges generate significant friction with the substrate during sliding32, making actuation difficult. Therefore, overcoming edge friction and enhancing driving force represent the primary challenge in realizing controllable in-plane SSL actuators on the micron scale.

In this work, we demonstrate an electrostatic in-plane SSL actuator, using a micro-scale graphite flake (15 × 15 μm2) in direct SSL contact with silicon dioxide tracks. The graphite flake rests atop 1.5 μm wide silicon dioxide tracks, reducing the edge contact length to one-tenth compared to a flat silicon dioxide substrate, thereby depressing edge friction. By applying a bias voltage to the buried electrode, injected net charge on the graphite flake enhances electrostatic driving force. The SSL actuator achieves a maximum relative actuation stroke of 82.3% of the feature size, which is 3.4 times larger than the previously reported maxima. Moreover, with the injected net charge effect, the SSL actuator demonstrates controllable and reciprocating actuation by systematically adjusting the form of bias voltage. Over 10,000 sliding cycles, no increase in friction or visible wear was observed, and contact stress consistently remained below the critical failure stress of the SSL state. These findings showcase the robust durability of microscale in-plane SSL actuators, poised to inspire the development of more SSL micro-devices with high performance and reliability.

Results

Design of the electrostatic in-plane SSL actuator

We designed the electrostatic actuation structure of SSL interfaces. Figure 1a depicts the schematic diagram outlining the theoretical framework behind electrostatic in-plane actuation at the SSL interface. This configuration features buried electrodes on both sides, with a single-crystal graphite flake forming SSL contact with the atomically flat silicon dioxide tracks positioned above the buried electrodes33. The left and right sides of the graphite flake form a capacitor with respective buried electrodes, connected in series through the graphite flake. The equivalent circuit diagram is also shown in Fig. 1a. Geometric parameters h, d, he, hg in Fig. 1a represent the vertical distance between graphite flake and electrodes, the distance between two electrodes, the thickness of the electrodes, and the thickness of graphite flake, respectively. The displacement of the graphite flake is denoted by x, representing the distance between the right boundary of the graphite flake and the left boundary of the right electrode. The origin is defined as x=0 when both boundaries are aligned.

a The left image shows a theoretical schematic of the electrostatic in-plane SSL actuator, featuring buried electrodes (yellow) and a graphite flake (black) in SSL contact with the silica surface (gray) on a silicon substrate (blue). Geometric parameters h, d, \({h}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}\), and \({h}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\) represent the vertical distance between the graphite flake and electrodes, the distance between two electrodes, the thickness of the electrodes, and the thickness of the graphite flake, respectively. The displacement of the graphite flake (x) is the distance between the right boundary of the graphite flake and the left boundary of the right electrode. \({F}_{x}\) and \({F}_{z}\) denote the lateral driving force and normal attraction force, respectively. A bias voltage (\({V}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}={V}_{{{{\rm{R}}}}}-{V}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\)) is applied to the buried electrodes, where \({V}_{{{{\rm{R}}}}}\) and \({V}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) are the potentials of the right and left electrodes, respectively, and each electrode acquires charges \(-{q}_{1}\) and \(-{q}_{2}\). Electrostatic induction causes the left and right sides of the graphite island to acquire charges of equal magnitude but opposite signs. The right image shows the equivalent circuit diagram of the actuator, where \({C}_{1}\) and \({C}_{2}\) are the series-connected capacitors formed by the graphite flake with the respective buried electrodes. b 3D schematic of the electrostatic in-plane SSL actuator, where L is the width of the graphite flake, s is the width of the supporting tracks, D is the distance between parallel tracks, \({W}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}\) is the width of the buried electrodes, and \({h}_{{{{\rm{t}}}}}\) is the height of the silica tracks. c Theoretical normal attraction force over lateral driving force \({F}_{z}/{F}_{x}\) under different air gap h, where \(L=15\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) and \(d=2\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\). The air gap used in our prototypes is \(h=0.9\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) (black star mark, that is, \({h}_{{{{\rm{t}}}}}=1\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) and \({h}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}=100\,{{{\rm{nm}}}}\)). d and (e) are distribution of electric field norm on side sectional view and von Mises stress of graphite flake bottom surface through finite element method (FEM) simulation, respectively. The purple arrows in (d) are electric field lines. The black dashed boxes in (e) are the contact region between the graphene flake and the silica tracks. The schematics in (a, b, d, and e) are not to scale. f and (g) are the relation between driving force (\({F}_{x}\)), normal attraction force (\({F}_{z}\)) and position of graphite flake, where the square points and the dashed line are the FEM simulation result and theoretical calculation result respectively. The bias voltage applied to electrodes is \({V}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}=200\,{{{\rm{V}}}}\). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

When a bias voltage \({V}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}\) is applied to the two buried electrodes, each electrode acquires charges \(-{q}_{1}\) and \(-{q}_{2}\), while the left and right sides of the graphite island also acquire charge of equal magnitude but opposite signs due to electrostatic induction. Applying the circuit theory for capacitor series, we differentiate the total electrostatic energy of the system34, obtaining the lateral driving force along the x-direction, \({F}_{x}\), and the normal attraction along the z-direction, \({F}_{z}\), as

respectively (see details in Supplementary Section 3). Here, L is the length of graphite flake, \({W}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}\) is the width of the buried electrodes, and \({\varepsilon }_{0}\) is the vacuum permittivity, \({\varepsilon }_{{{{\rm{r}}}}}\) is the relative permittivity of the silica. It is worth noting that the \({F}_{x}\) represents a linear restoring force whose magnitude varies with the applied bias voltage, with its positive and negative signs indicating direction. In contrast, \({F}_{z}\) consistently points in the negative direction of the z-axis, and we focus on its magnitude of \({F}_{z}\) in subsequent discussions, disregarding its direction.

Since graphite flakes can only be actuated when the actuating force exceeds the frictional force \({F}_{x} > f\), reducing friction is key to successful actuation. Although SSL contact state achieves low friction, edge defects of the single-crystal graphite flake can generate significant friction with the substrate during sliding. This edge friction can be 4-5 orders of magnitude greater than that of the areal contact32. Therefore, we designed the silica track structure to replace the full contact structure. In this design (Fig. 1b), the graphite flake is supported by fabricated silica tracks, preventing the edges of the graphite flakes from directly contacting the substrate, thereby significantly reducing edge friction. Compared to full edge contact, the track design reduces the total length of edge contact from 4L to 4s, where s is the width of the silica track. Geometric parameters of the tracks are labeled in Fig. 1b, including the distance between the two parallel tracks D, the width of the silica tracks S, and the height of the silica tracks \({h}_{{{{\rm{t}}}}}\). Furthermore, since the friction force is proportional to the attraction force \(f=\mu {F}_{z}\), where μ is the friction coefficient of the SSL interface. The following relationship must be satisfied to achieve in-plane actuation:

It is more feasible to actuate a graphite flake with a smaller value of \({F}_{z}/{F}_{x}\). Figure 1c shows the theoretical relationship of \({F}_{z}/{F}_{x}\) obtained by Eq. (1) for L=15 μm and d=2 μm. The ratio \({F}_{z}/{F}_{x}\) decreases rapidly when the air gap exceeds 0.9 μm. However, the air gap h should not be too large, as \({F}_{x}\) decreases with increasing h (Eq. (1), see details in Supplementary Fig. 4). Therefore, in subsequent fabrication and experiments, the air gap h was set to 0.9 μm, with \({h}_{{{{\rm{t}}}}}=1\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) and \({h}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}=100\,{{{\rm{nm}}}}\).

Based on the above analysis and design, the 3D structure diagram of the electrostatic in-plane SSL actuator we finally designed is shown in Fig. 1b. FEM simulations were carried out for the electrostatics by using the model shown in Fig. 1b. The key parameters are L = 15 μm, \({h}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}=200\,{{{\rm{nm}}}}\), \({W}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}=8{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\), \({h}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}=100\,{{{\rm{nm}}}}\), \(d=2\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\), \(h=0.9\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\), \({h}_{{{{\rm{t}}}}}=1\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\), D = 10 μm, \(S=1.5\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\), \({\varepsilon }_{{{{\rm{r}}}}}=1\) for air and \({\varepsilon }_{{{{\rm{r}}}}}=3.9\) for silica (see details in “Methods” and Supplementary Section 5). The graphite flake is modeled as a floating potential node with zero charge (\(Q=0\). In addition, the left electrode is grounded (\({V}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=0\)), while the potential of the right electrode is set to the applied bias voltage, \({V}_{{{{\rm{R}}}}}\)=\({V}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}\). When \({V}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}=200\,{{{\rm{V}}}}\) and \(x=3\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\), the simulated distribution of electric field norm on the side sectional view is shown in Fig. 1d, where the purple arrows are electric field lines. The asymmetric electric field distribution primarily generates the electrostatic driving force \({F}_{x}\) on the graphite flake, with the maximum electric field strength reaching approximately \({10}^{8}{{{\rm{V}}}}/{{{\rm{m}}}}\) near the right buried electrode.

Combining the electrostatic field derived from the FEM simulation enables calculation of the electrostatic force acting on the graphite flake. Concurrently, considering the contact between the graphite flake and the silica track, the von Mises stress distribution on the bottom surface of the graphite flake can be obtained, as depicted in Fig. 1e. Here, the maximum stress occurs near the silica track, significantly lower than the reported critical stress \(( > 1\,{{{\rm{GPa}}}})\) to break down the SSL state35. At the same time, the simulated deformation of the graphite flake corresponding to the stress is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3a. The results indicate that the deformation of the contact region is less than 0.5 nm, comparable to the surface roughness of the fabricated silica track itself (see Supplementary Fig. 3b). Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the deformation of the graphite flakes does not significantly affect the SSL state. Additionally, the maximum deformation of the graphite flake (3 nm) in Supplementary Fig. 3a due to normal electrostatic attraction is approximately 0.33% of the initial gap h=0.9 μm. This value does not exceed the pull-in instability criterion, which states that the elastic deformation of the cantilever beam cannot exceed one-third of the initial gap36. Therefore, the SSL actuator is expected to remain stable and will not experience pull-in instability within the bias voltage range used in our experiments.

Based on these simulations, it is evident that the graphite flake experiences primarily a lateral driving force \({F}_{x}\) along the x-direction and a negligible force \({F}_{y}\) along the y-direction due to the symmetry. The lateral driving force \({F}_{x}\) (Fig. 1f) and normal attraction \({F}_{z}\) (Fig. 1g) evaluated from FEM simulation and theoretical modeling across different \(x\) positions (from \(0\) to \(13\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\)) are consistent, validating robustness of the model. The discrepancies are primarily attributable to edge effects in capacitance37, which are most pronounced at extremes of graphite flake movement (\(x=0\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) and \(x=13\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\)).

Based on the above simulations and theoretical insights, we ascertain that using the silica track structure to mitigate edge friction results in the actuation of graphite flakes towards a balanced position \((x=6.5\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}})\), driven by substantial linear restoring forces and the low friction characteristic of the SSL interface.

Fabrication of the electrostatic in-plane SSL actuator

Building on the structural framework and parameters detailed in the preceding section, it is evident that engineering a track structure with an atomically smooth surface yields two significant advantages. Firstly, it reduces the heightened friction caused by the edges of the graphite flake, and secondly, it diminishes the normal electrostatic attraction force. Consequently, these measures collectively limit frictional effects to an ultra-low threshold, facilitating a substantial actuated stroke.

To manufacture this structure, we first created silica tracks using electron beam lithography (EBL) and reactive ion etching (RIE) on atomically flat silicon oxide wafers. Next, we fabricated the actuated electrodes via EBL and electron beam evaporation (see details in “Methods” and Supplementary Section 1). Scanning electron microscope (SEM) observations following this fabrication process are depicted in Fig. 2a.

a SEM observation of electrodes and silica tracks before the graphite flake transfer process. b AFM topography of the corresponding structures in a. c Height profiles of line AB in (b). d SEM observation of the transfer of graphite flakes on top of the tracks and electrodes. e AFM topography of the corresponding structures in (d). f Height profiles of lines CD and EF in (e). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We further characterized the surface topography of the silica tracks and buried electrodes by using an atomic force microscope (AFM), as shown in Fig. 2b. The section of orange line AB (Fig. 2c) and the geometric parameters of the fabricated structure are consistent with the theoretical design. In addition, we examined the topography of the silica tracks, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3b. Statistical analysis indicates that the surface roughness of the silica tracks after fabrication and cleaning is 0.6 nm. According to previous research, this roughness is sufficient to form a stable SSL contact with the graphite flake33. Subsequently, we transferred the graphite flake with length of \(L=15\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) and thickness of \({h}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}=200\,{{{\rm{nm}}}}\) (see details in “Methods” and Supplementary Section 2) onto the top surface of the silica tracks. SEM observation and AFM topography characterization after the transfer process are shown in Fig. 2d and e, respectively. The sections of green line AB and blue line EF are detailed in Fig. 2f. From the characterization results, it is evident that the graphite flake rests on parallel silica tracks, with a portion of the buried electrodes positioned directly beneath the graphite flake to provide lateral driving force, aligning with the design in Fig. 1b.

Large relative actuated stroke

After preparing the sample as described earlier, we applied a bias voltage between the buried electrodes and observed the electrostatic in-plane actuation process using a high-speed camera (for detailed experimental workflow, please refer to “Methods” section and Supplementary Section 8). The continuous unidirectional multi-step actuation process is shown in Fig. 3a, and the corresponding recorded center position of graphite flake over time is plotted in Fig. 3b. The whole actuation process includes three steps.

a SEM image series of continuous unidirectional multi-step actuation process. The form of voltage applied at each step is as follows. Step 1 from (i) to (ii): 10 kHz AC square wave, 150 V amplitude, 50% duty cycle, actuation distance about 1.76 μm. Step 2 from (ii) to (iii): 10 kHz AC square wave, 200 V amplitude, 50% duty cycle, actuation distance about 1.18 μm. Step 3 from (iii) to (iv): DC, 200 V amplitude, actuation distance about 9.41 μm. b Corresponding position of the graphite flake during the actuation process in (a) as a function of time, where the moment of charge injection (the lightning symbol) and applied voltage form are marked in the figure. c SEM image series of two continuous reciprocating actuation processes. d Corresponding position of the graphite flake during the actuation process in (c) as a function of time. The actuation direction (arrow directions), applied voltage forms (arrow colors and circular marks), and moments of charge injection (lightning symbols) are indicated in (c and d). The white dashed line in (a and c) indicates the geometric center of the buried electrode gap, corresponding to \(x=6.5\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In the first step (i-ii), an AC square wave voltage with a frequency of 10 kHz, an amplitude of 150 V, and a duty cycle of 50% was applied to the electrodes, resulting in an actuation distance of approximately 1.76 μm. At this stage, the graphite flake had not yet reached its equilibrium position due to the small lateral driving force near equilibrium, which was insufficient to overcome friction and complete the actuation. In the second step (ii-iii), the amplitude of the AC square wave was increased to 200 V to enhance the lateral driving force (refer to the theoretical relationship Eq. (1)). The graphite flake was further actuated, achieving a displacement of 1.18 μm, approaching the equilibrium position at the geometric center between the buried electrodes. In the third step (iii-iv), a DC voltage of 200 V was applied to the graphite flake, resulting in a significant actuation with a displacement of 9.41 μm. The lightning symbol in Fig. 3b indicates that the charge injection occurs during this process, which will be explained in detail in the next section. The total travel distance across the three continuous actuations amounted to \(12.35{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\), demonstrating a relative actuation stroke of 82.3% to characteristic size of the graphite flake itself (\(15\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\)). For a detailed visualization of the overall actuation process, please refer to Supplementary Movie 1. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the SSL actuator exhibits a relative stroke approximately 3.4 times larger than the maximum value of 24.5% reported previously for microscale electrostatic in-plane actuation.

The relative stroke refers to the ratio of the actuation distance to the characteristic size of the actuation configuration. Square data points of different colors represent results from reported studies. The previously reported largest relative stroke is 24.5%. The SSL actuator exhibits a relative stroke of 82.3% (hexagonal pink marker) with respect to the characteristic size of the graphene flake (15 μm), which is nearly 3.4 times the previously reported maximum value. Copyright 2013, IEEE; Copyright 1989, Elsevier; Copyright 1993, IEEE; Copyright 2006, IEEE; Copyright 2002 Elsevier. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

A continuous reciprocating multi-step actuation process is demonstrated in Fig. 3c (Supplementary Movie 2), and the corresponding recorded center position of graphite flake over time is plotted in Fig. 3d. The colors and directions of the arrows in Fig. 3c and d represent the different forms of applied voltage and actuation direction respectively, while the lightning symbol represent that charge injection that occurs during this process. The results show two continuous reciprocating actuations in order. For the first step (i-ii), a 200 V DC voltage was applied to the buried electrodes, causing the graphite flake to actuate from its initial position near the geometric center of two buried electrodes, i.e., the equilibrium position \({x}_{0}=(L-d)/2=6.5\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\), to the right. For the second step (ii-iii), a \(-200\) V DC bias voltage was applied (indicated by green round mark in Fig. 3c and d, which represent the process of charge neutralization), followed by a square-wave AC voltage with a frequency of 10 kHz, an amplitude of 200 V, and a duty cycle of 50%. This sequence actuates the graphite flake back to its original position on the left. The repeated reciprocating actuations are carried out as shown in steps iii-v. These results illustrate the reciprocating in-plane actuation of the graphite flake achieved by alternating the form of the applied bias voltage from DC to AC. The mechanism underlying this phenomenon (charge injection) will be further explained and analyzed in the next section.

Actuated stroke enhancement by charge injection

According to the theoretical analysis in Fig. 1f and Eq. (1), the lateral driving force \({F}_{x}\) is proportional to the square of the applied bias voltage \({V}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}\), with the equilibrium position at the geometric center of the buried electrodes (\({x}_{0}=(L-d)/2=6.5\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\)). Therefore, regardless of whether the applied bias voltage is AC or DC, the graphite flake is expected to be actuated to the geometric center of the buried electrodes. However, Fig. 3 illustrates a different outcome: when a DC bias voltage is applied, the graphite flake moves to the right of the previous geometric center, whereas an AC bias voltage restores the flake to its original equilibrium position.

The observed phenomenon is attributed to the injection of a net charge \(Q\) into the graphite flake upon application of a bias voltage. As shown in Fig. 5a, before applying the bias voltage (\({V}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}=0\,{{{\rm{V}}}}\)), no charge is injected, and the equilibrium position is at the geometric center of the buried electrodes (left image in Fig. 5a). When the bias voltage is applied (\({V}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}} > 0\,{{{\rm{V}}}}\)), the injected charges \(Q\), induced by the strong electric field, cause the equilibrium position to shift to \(\Delta {x}_{0}\) (right image in Fig. 5a). The different colors in Fig. 5a represent the simulated potential distribution.

a Physical process of charge injection inducing an equilibrium position shift. Before the bias voltage is applied \(({V}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}=0\,{{{\rm{V}}}})\), there is no injected charge, and the equilibrium position is at the geometric center of the buried electrodes (left image). When bias voltage is applied \(({V}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}} > 0\,{{{\rm{V}}}})\), there are injected charges Q induced by strong electric field and the equilibrium position will shift to \(\Delta {x}_{0}\) (right image). The different colors in the figure represent the simulated potential distribution, where the bias voltage applied when calculating the potential distribution in the right image is 150 V. b Comparison of simulated driving force (\({F}_{x}\)), normal attraction force (\({F}_{z}\))-position relationship with (\(Q=-50\,{{{\rm{fC}}}}\)) and without (\(Q=0\,{{{\rm{C}}}}\)) injected charges. c Theoretical (solid line) and simulated (triangle points) relationship between the equilibrium position shift and injected charge. d Schematic diagram of the experimental setup to measure the injected charge of the graphite flake, which is obtained by contacting graphite flake with a high precision pico-ammeter grounded at one end and measuring the discharge current as a function of time. The different colors in the figure represent the simulated potential distribution following the short-circuiting of the two buried electrodes after charge injection. e Discharging curve measured using the experimental setup in (d). As the probe approaches the charged graphite flake, the ammeter current gradually increases due to electrostatic induction. Upon contact, a pronounced negative current peak is observed. Integration yields injected charges of \(-31.95{{{\rm{fC}}}}\) and \(-29.30\,{{{\rm{fC}}}}\) in two tests, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The simulated electric field distribution at a bias voltage of \(200\,{{{\rm{V}}}}\) (Fig. 1d) shows a maximum electric field strength of approximately \({10}^{8}\,{{{\rm{V}}}}/{{{\rm{m}}}}\) on the side associated with the smaller capacitance. Previous studies have shown that electric fields of this intensity are sufficient to ionize molecules locally in the air domain, creating a localized plasma channel for charge injection and imparting a net charge to the graphene flake17,38. However, this electric field strength remains well below the threshold for irreversible damage due to air breakdown39. Simultaneously, when a low electric field strength is applied for a short duration, no irreversible effects on the material occur40. The actuation test results in Fig. 3 further confirm that no irreversible device damage occurred due to breakdown during the reciprocating actuation process.

To study the impact of the injected charge on the driving force, we modified the boundary condition by adjusting the suspension potential of the graphite flake from zero net charge to a specific value, \(Q\). The corrected lateral driving force \({F}_{x}\) and normal attraction force \({F}_{z}\) can be obtained based on Eq. (1) as

(see details in Supplementary Section 4). Figure 5b shows the FEM simulation results of \({F}_{x}\) (lower) and \({F}_{z}\) (upper) for different displacements \(x\) with both \(Q=0\,{{{\rm{C}}}}\) and \(Q=50\,{{{\rm{fC}}}}\) under \({V}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}=200\,{{{\rm{V}}}}\). When the graphite flake carries a net charge of \(Q=50\,{{{\rm{fC}}}}\) (positive), \({F}_{z}\) shows a similar trend to \(Q=0\,{{{\rm{C}}}}\), but with a slight increase in value. For \({F}_{x}\), the equilibrium position \({x}_{0}\) (\({F}_{x}=0\), marked by the black dashed line), is defined. Simulation results with \(Q=0\,{{{\rm{C}}}}\) indicate \({x}_{0}=\left(L-d\right)/2=6.5\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\). With \(Q=50\,{{{\rm{fC}}}}\), the equilibrium position shifts leftward. The theoretical formula for the shift \(\Delta {x}_{0}\) is derived from Eq. (3):

which is shown as the red solid line in Fig. 5c (linear relationship). The red triangle solid point represents the FEM simulation result, aligning with the parameters in Fig. 1 and experimental conditions. The theoretical and simulation results exhibit consistent trends with minor magnitude differences attributed to neglecting fringe effects of the parallel plate capacitor37.

From these findings, applying a DC bias voltage of \(200\,{{{\rm{V}}}}\) injects a negative charge (\(Q < 0\)) into the graphite flake, shifting the equilibrium position rightward. Conversely, applying a -\(200\,{{{\rm{V}}}}\) DC bias neutralizes the previously injected charge. Subsequently, applying a high-frequency (10 kHz) AC bias results in an average net zero injected charge due to the short period relative to the charge injection relaxation time, thus maintaining the equilibrium position at the geometric center of the buried electrodes.

To measure the net charge injected into the graphite flake, we first short-circuited the two buried electrodes after applying a \(150\,{{{\rm{V}}}}\) DC bias voltage. We then used a tungsten microprobe connected to a high-precision pico-ammeter to contact the top surface of the graphite flake. Figure 5d presents a schematic of the experimental setup, illustrating the potential distribution with the injected charge in the graphite flake. The testing process comprises two stages: approach and contact. Figure 5e shows the corresponding current signal upon with time in these two steps. As the tungsten probe approaches the graphite flake, the ammeter current increases slightly due to electrostatic induction. Upon contact, a distinct negative current waveform appears, indicating that negative charges are injected into the graphite flake by the \(150\,{{{\rm{V}}}}\) DC bias voltage. Integration of the current curves in Fig. 5e yields total injected charges of \(-31.95{{{\rm{fC}}}}\) and \(-29.30\,{{{\rm{fC}}}}\) in two tests, respectively. This is consistent consistent with the observed phenomenon of the graphite flakes shifting rightward due to the equilibrium position shift after negative charge injection.

Comparing the experimental results (Fig. 3) with the simulation results of the equilibrium position shift in Fig. 5c, where the graphite flake moved approximately \(\Delta {x}_{0}=4.2-5.8\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) to the right after applying a DC bias voltage, the injected charge is estimated to be around \(-80{{{\rm{fC}}}}\), with an absolute value is larger than the measured results above. This discrepancy may stem from two primary reasons. Firstly, in the test setup shown in Fig. 5d, not all the net charge of the graphite flake flows through the pico-ammeter. Instead, some remains to maintain electrostatic balance with the charge in the buried electrodes. Secondly, a portion of the net charge might be dissipated by conductive particles and compounds in the air during the testing process.

Both theoretical analysis and experimental results confirm that the primary reason the graphite flake is actuated to the right with a large relative stroke after applying a DC voltage is due to the shift in the equilibrium position of the lateral driving force \({F}_{x}\), induced by the injected charge.

Robust reliability of SSL microdevices

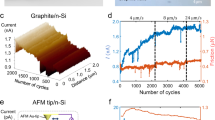

In this section, we demonstrate the reliability of the SSL microdevices. Firstly, using the atomic force microscope system (AFM, NT-MDT), we measured the friction at the graphite flake/silica tracks interface. The specific method involves pressing the AFM tip onto the upper surface of the Pt cap of the graphite flake. Given that the friction coefficient between the Pt cap and the AFM tip is significantly higher than that of the SSL interface formed by the bottom surface of the graphite flake and the silica tracks, the AFM tip is capable of dragging the graphite flake to slide on the silica tracks under a specific normal force. The sliding friction between the graphite flake and the silica tracks is then measured through the torsion of the AFM tip’s cantilever beam (for further details, see “Methods” and Supplementary Section 7)41. The measured friction under different normal forces is depicted in Fig. 6a, showing low coefficients of 0.0012 (loading) and 0.0015 (unloading). To measure the sliding friction force of a graphite flake on silica tracks without applying a normal load, we positioned the AFM tip to slide along the substrate and push the graphite flake from the side laterally. The resulting lateral force throughout the process is depicted in Fig. 6b, with the inset illustrating the complete testing procedure. Initially, the tip remained in contact only with the substrate, and the measured lateral force reflected the interaction between the tip and the substrate alone. Upon reaching the critical transition point, marked by the blue dotted line, the tip contacted both the substrate and the edge of the graphite flake, leading to a measured increase in lateral force of \(42\,{{{\rm{nN}}}}\), corresponding to the friction between the graphite flake and the silica track. Thereafter, the tip continued to push the graphite flake to the right while maintaining contact with the substrate.

a Friction measurements of graphite flakes on silica tracks under varying normal attraction forces, with a displacement amplitude of 1 μm and speed of 1 μm/s. Each point and error bar represent the average and standard deviation from 50 tests. b Lateral force measurements while pushing a graphite flake on silica tracks from the left side using an AFM tip. Inset: schematic diagram of the test method. The tip scans from left to right with a displacement amplitude of 2 μm and a speed of 1 μm/s: in the first half, the tip only slides in contact with the substrate without touching the graphite flake; after crossing the middle position (blue dotted line), the tip contacts the substrate and the side of the graphite flake simultaneously and pushes the graphite flake to the right. c Friction measurements over 11,000 consecutive sliding cycles under a normal force of \({F}_{{{{\rm{N}}}}}=10\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{N}}}}\), with a displacement amplitude of 1 μm and speed of 1 μm/s. d The amplitude of the cantilever in tapping mode of AFM was measured on the surface of the silica track in contact with the graphene flake after 11,000 sliding cycles. The magnitude of the amplitude change provides insight into the flatness of the local topography. e Raman characterization of the graphite flake surface in contact with silica tracks after 11,000 sliding cycles, with test points labeled as A-I. Inset: optical observation of the flipped graphite flake after sliding. f Raman characterization of the silica tracks surface in contact with graphite flake after 11,000 sliding cycles, with test points labeled as A-J. Inset: optical observation of the silica tracks after sliding. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Furthermore, we performed an 11,000-cycles sliding experiment with the graphite flake on the silica tracks utilizing the same method as described in Fig. 6a. This experiment was performed with a displacement amplitude of \(1\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) and a speed of \(1\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}/{{{\rm{s}}}}\), while maintaining a constant normal force of \({F}_{{{{\rm{N}}}}}=10\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{N}}}}\). The friction force in each sliding cycle is shown in Fig. 6c. Measured friction is stable at around \(47\,{{{\rm{nN}}}}\) with minimal variation throughout the process, indicating the robustness and stability of the SSL state between the graphite flake and silica tracks.

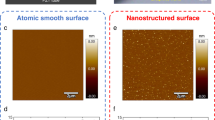

Following the 11,000-cycle sliding experiment, to characterized the sliding interface between the graphite flakes and the silica tracks, we used a tungsten probe coated with AB micro glue, secured the graphite flake and lifted it42, as detailed in Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Section 7. The amplitude of the cantilever in tapping mode of AFM was subsequently measured on the surface of the silica track in contact with the graphene flake after 11,000 sliding cycles, as shown in Fig. 6d. The magnitude of the amplitude change can reflect the flatness of the local topography, while the lack of obvious numerical changes in the silica track surface region in Fig. 6d indicates that no wear debris or surface damage was observed after sliding. Next, we conducted Raman characterization at various locations on the graphite flake surface in contact with the silica tracks, as depicted in Fig. 6e. The absence of a detectable D peak (at 1350\(\,{\mbox{c}}{{\mbox{m}}}^{-1}\)) indicates that the graphite flake surface remained undamaged after 11,000 sliding cycles. To corroborate this, Raman measurements were also carried out at different positions on the silica track surface post-sliding, as shown in Fig. 6f. The corresponding Raman spectra revealed no graphite-related peaks, such as the G peak (at 1580\(\,{\mbox{c}}{{\mbox{m}}}^{-1}\)) or 2D peak (at 2700\(\,{\mbox{c}}{{\mbox{m}}}^{-1}\)), confirming that no graphite wear debris was present on the silica tracks after sliding. These results confirm the wear-free feature of SSL contacts between the graphite flake and silica tracks. Furthermore, the friction force at the graphite flake/silica tracks interface is much smaller than the maximum driving force shown in Fig. 1f, underscoring the feasibility of electrostatic in-plane actuation at the SSL interface.

Finally, we examine the stability of the electrostatic planar SSL actuator. According to previous theoretical work, the boundary of the buried electrodes below generates constraints (forming potential wells) on two degrees of freedom of the graphite flake outside the driving direction, thus achieving actuator stability30. Additionally, considering the light mass of the graphite flake with the Pt cap, which is only \(5.78\times {10}^{-13}{{{\rm{kg}}}}\), calculations show that even with low in-plane static friction of \(42\,{{{\rm{nN}}}}\) (Fig. 6b), a planar vibration acceleration of \(7412\,g\) (\(g=9.8\,{{{\rm{m}}}}{/{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{2}\) is the gravity acceleration) is required to induce movement of the graphite flake. This value far exceeds the vibration reliability requirements of MEMS products. Moreover, due to the presence of van der Waals adsorption force, the SSL actuator also demonstrates exceptional out-of-plane stability (see Supplementary Section 9 for a detailed analysis).

Discussion

In conclusion, structural superlubricity (SSL), characterized by zero wear and ultra-low friction at contact interfaces, effectively addresses challenges in micro-actuators, such as limited actuated stroke, constrained movement modes, and reduced lifespan due to friction and wear. We demonstrate an electrostatic in-plane SSL actuator comprising buried electrodes, silica tracks, and a microscale graphite flake (15 × 15 μm2). By employing the charge injection method, the graphite flake achieves an relative actuation stroke of up to 82.3% to its size by applying voltage to buried electrodes, nearly 3.4 times greater than the best previously reported result of 24.5%. Reciprocating actuation is also realized by altering the bias voltage form. Above performance facilitated by ultra-low SSL interface friction, absence of anchoring constraints, and equilibrium position shifts due to injected charge during actuation. Notably, no visible wear was observed at the SSL interface after over 10,000 sliding cycles, suggesting robust reliability. Furthermore, estimates indicate that the energy consumption of SSL actuators caused by friction and charge injection (~16 pJ in total) is significantly lower than that of commercial MEMS actuators (about tens of nJ)17, see details in Supplementary Section 10, which also represents a crucial advantage. Our research has verified the feasibility of electrostatic in-plane actuation in an SSL state, and introduces a design concept for SSL-based micro devices. The SSL actuator presented in this study will become the foundational unit for enabling controllable motion in future practical high-reliability SSL microsystems, such as electrical contacts in plane switches, motion units in electrostatic motors, adjustable valve for micro pumps, mechanical information storage unit, etc.

In addition, this study outlines a set of design criteria for electrostatic in-plane SSL actuators, summarized as follows: (1) Establish a SSL interface and eliminate the effect of the graphite flake’s edges; (2) Ensure that the ratio of electrostatic lateral driving force (\({F}_{x}\)) to normal attraction force (\({F}_{z}\)) exceeds the friction coefficient (\(\mu\)) to enable motion, satisfying the condition \({F}_{x}/{F}_{z} > \mu\); (3) The width of the buried electrodes (\({W}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}\)) should closely match the width of the graphite flake (\(L\)) to maintain in-plane stability during actuation; (4) To achieve a large stroke and enable reciprocating actuation, the applied voltage must generate an electric field exceeding the critical value for local ionization necessary for charge injection, but below the threshold for irreversible damage due to air breakdown (related to the dielectric gap \(d\)); (5) Alternating AC and DC bias voltages must be applied to the buried electrodes to achieve reciprocating actuation.

Future work will focus on reducing the actuation voltage. Potential solutions include using methods such as metal cap internal stress to achieve edge warping of the graphite flake, thereby physically eliminating high edge friction caused by electrostatic adsorption. Combining this with atomic-level plane polishing of heterogeneous materials can enable direct SSL contact between the edge-warped graphite flake and a flat, high-dielectric-constant dielectric. This approach not only reduces the gap between the graphite flake and the buried electrodes but also leverages the high dielectric constant to increase the driving force (Eq. (1)). For example, increasing the relative dielectric constant from 1 (air gap) to 25 and reducing the gap from 900 nm to 100 nm can reduce the bias voltage required to achieve the same driving force by a factor of 15, to around 13 V. This reduction offers significant application advantages.

Methods

Fabrication of silica tracks and buried electrodes

Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the entire fabrication process of the silica tracks and buried electrodes (steps i-ix). Firstly, silicon dioxide wafers (Guangzhou Fangdao Semiconductor Co.) are cleaned (i). In steps (ii) and (iii), the photoresist (AZ 5214) was spun on the substrate and patterned by photolithography. Then the exposed silicon dioxide was etched by reactive ion etching (iv), and the photoresist was cleaned off (v). Silicon dioxide tracks without electrodes were completed. In step (vi), the photoresist was spun on, and a secondary photolithography process was carried out (vii). Then a gold film with 100 nm in thickness was deposited using electron beam evaporation (viii). Lastly, the silicon dioxide tracks and electrodes were obtained after a lift-off process (ix). After all processes are completed, the samples will undergo ultrasonic cleaning using ethanol, alcohol, and deionized water sequentially for 5 minutes each to remove surface contaminants.

Fabrication and transfer of graphite flakes

The square graphite mesa arrays with Pt film were fabricated from highly ordered pyrolytic graphite (HOPG, ZYB grade (Brucker))43. The fabrication process is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2a. Magnetron sputtering was employed to deposit a 100 nm-thick Pt film on a freshly cleaved HOPG firstly. Secondly, a 1.5 μm-thick AZ 1500 photoresist film was spun on the Pt film, and then patterned the photoresist using photolithography. Pt pattern array was etched by ion beams. Finally, the Pt pattern array was used as a mask to remove the photoresist and HOPG by oxygen reactive ion etching (RIE) to obtain a graphene mesa, where the etching depth is around \(1.1{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\). 3D topography profile of graphite mesa with Pt film was obtained using BRUKER ContourGT-X (Supplementary Fig. 2b). The width and height of the graphite mesa are \(15\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) and \(1.2\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) respectively. The graphite flake is transferred to the top of silica tracks by following the procedure in the previously reported work41,42.

Electrostatic in-plane actuation tests

We used a waveform generator (RIGOL DG 1022) to generate a square wave AC signal or DC signal, which is amplified to \(200\,{{{\rm{V}}}}\) by a high voltage amplifier (TEGAM 2350). The voltage is applied on the left and right buried electrode by utilizing a homemade probe station. The left buried electrode is kept grounded throughout the experiment. Optical microscope images of the samples are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. The motion of the graphite flake was captured by a high-speed CCD (Photron FASTCAM SA-Z) and saved to the computer for subsequent analysis. The whole actuation experiments were conducted in a cleanroom environment, maintained at a temperature of 22 ± 1 °C and a relative humidity of 40 ± 4%.

Friction measurement41,42

The measurements of friction between the graphite flake and silicon dioxide tracks were performed under ambient atmosphere throughout the entire experiments. The experimental system includes a NT-MDT AFM (NTEGRA Prima), a 100 μm XYZ piezoelectric displacment stage, an objective lens (×100, Mitutoyu) and a visual AFM tip (VIT_P series, NT-MDT). The torsional deformation of the cantilever of the AFM tip was recorded as the electric signal. The signal was then converted to the friction by a calibration factor obtained from a diamagnetic lateral force calibration experiment44, and to the normal force by another calibration factor derivated from the Sader method45,46. The specific calibration and friction measurement process refers to Supplementary Section 7. The whole tribology experiments were conducted in a cleanroom environment, maintained at a temperature of 22 ± 1 °C and a relative humidity of 40 ± 4%.

Finite element analysis

The model consists of a silicon substrate in the bottom, silica tracks in the middle, two electrodes in the groove, a graphite flake on the top of tracks, and an unshown large sphere air domain (constructed to facilitate convergence in the electrostatic field finite element simulation, effectively representing the atmosphere in real scenarios, with a radius of 150 μm). Both the silicon and silica substrates are square, length is 50 μm and height is 2 μm. Three 1 μm deep and 10 μm wide grooves are etched on the silicon dioxide substrate, forming two silicon dioxide tracks. Two electrodes with a height of \(100\,{{{\rm{nm}}}}\) and a spacing of \(2\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) are placed at the bottom of the middle groove. A square graphite flake with a side length of \(15{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{m}}}}\) and a height of 200 nm is placed on the tracks. The above parameter settings are realized in the fabricated SSL in-plane actuators. The model is symmetric about the \(x-z\) plane. The relative permittivity \({\varepsilon }_{{{{\rm{r}}}}}\) of air is set to 1, for silicon dioxide \({\varepsilon }_{{{{\rm{r}}}}}=3.9\), for silicon \({\varepsilon }_{{{{\rm{r}}}}}=11.7\). As for the boundary conditions, the edge of air domain is set to be zero-charged, which means n⋅D=0, where n is the boundary normal and D is the electric displacement. The potentials of left and right electrodes are \({V}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=0\,{{{\rm{V}}}}\) and \({V}_{{{{\rm{R}}}}}=200\,{{{\rm{V}}}}\), respectively. The graphite flake is treated as a floating potential node and carries net charge Q. The injected charge Q is set to 0 in Fig. 1d-g, and changed to analyze its effect on the equilibrium position (Fig. 5). The total charge of the system is conserved. In the beginning of the simulation, the voltage at all positions is set to 0 unless otherwise specified. The Maxwell electrostatic equation

is then solved, where \({\rho }_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}\) is the charge density, E is the electric field and V is the electric potential47. We assume that both air and silicon dioxide are linear dielectric48, and therefore \({{{\bf{D}}}}\,=\,{\varepsilon }_{0}{\varepsilon }_{{{{\rm{r}}}}}{{{\bf{E}}}}\). The results of electric fields and potential distributions are shown in Fig. 1d. By differentiating the total electrostatic potential energy \(W=\frac{1}{2}{\int }_{V}{{{\bf{D}}}}{{{\boldsymbol{\cdot }}}}{{{\bf{E}}}}{{{\rm{d}}}}V\) along different directions, we obtain the driving forces in the corresponding directions (Figs. 1f, g and 5b). To simulate the deformation and stress of the graphite flake, we treated all materials using linear elastic models. Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of materials are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The bottom surface of silicon substrates is fixed throughout the simulation.

Data availability

The source data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Berman, D. & Krim, J. Surface science, MEMS and NEMS: progress and opportunities for surface science research performed on, or by, microdevices. Prog. Surf. Sci. 88, 171–211 (2013).

Algamili, A. S. et al. A review of actuation and sensing mechanisms in MEMS-based sensor devices. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 16, 1–21 (2021).

Yazdi, N., Ayazi, F. & Najafi, K. Micromachined inertial sensors. Proc. IEEE 86, 1640–1659 (1998).

Sijie, Y. & Qingsong, X. A review on actuation and sensing techniques for MEMS-based microgrippers. J. Micro-Bio Robot. 13, 1–14 (2017).

Rebeiz, G. M. & Muldavin, J. B. RF MEMS switches and switch circuits. IEEE Microw. Mag. 2, 59–71 (2001).

Jang, J. E. et al. Nanoscale memory cell based on a nanoelectromechanical switched capacitor. Nat. Nanotech. 3, 26–30 (2008).

Nguyen, C. T. C. MEMS technology for timing and frequency control. IEEE T. Ultrason. Ferr. 54, 251–270 (2007).

Sazonova, V. et al. A tunable carbon nanotube electromechanical oscillator. Nature 431, 284–287 (2004).

Mashimo, T. & Izuhara, S. Review: Recent advances in micromotors. IEEE Access 8, 213489–213501 (2020).

Livermore, C. et al. A high-power MEMS electric induction motor. J. Microelectromech. S. 13, 465–471 (2004).

Wang, D., Watkins, C. & Xie, H. (2020) MEMS mirrors for LiDAR: a review. Micromachines 11, 456 (2020).

Schenk, H. et al. Large deflection micromechanical scanning mirrors for linear scans and pattern generation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quant. 6, 715–722 (2000).

Alley, R. L. Surface roughness modification of interfacial contacts in polysilicon microstructures. 7th Int. Conf. Sensors and Actuators, Yokohama, 1993, 291 (1993).

Abe, T., Messner, W. C. & Reed, M. L. Effects of elevated temperature treatments in microstructure release procedures. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 4, 66–75 (1995).

Jones, R. L., Harrod, B. L. & Batteas, J. D. Intercalation of 3-phenyl-1-proponal into OTS SAMs on silica nanoasperities to create self-repairing interfaces for MEMS lubrication. Langmuir 26, 16355–16361 (2010).

Mulhern, G. T. Supercritical carbon dioxide drying of microstructures. Proc. Transducers’ 93, Yokohama, June, 296–299 (1993).

Rebeiz, G. M. RF MEMS: Theory, Design, and Technology. John Wiley & Sons, 74–189 (2004).

Florando, J. N. & Nix, W. D. A microbeam bending method for studying stress-strain relations for metal thin films on silicon substrates. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 53, 619–638 (2005).

Olfatnia, M., Sood, S., Gorman, J. J. & Awtar, S. Large stroke electrostatic comb-drive actuators enabled by a novel flexure mechanism. J. Microelectromech. S. 22, 483–494 (2013).

Muhlstein, C. L., Brown, S. B. & Ritchie, R. O. High-cycle fatigue of single-crystal silicon thin films. J. Microelectromech. S. 10, 593–600 (2001).

Muhlstein, C. L., Stach, E. A. & Ritchie, R. O. Mechanism of fatigue in micron-scale films of polycrystalline silicon for microelectromechanical systems. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 1532–1534 (2002).

Long-Sheng, F., Yu-Chong, T. & Muller, R. S. IC-processed electrostatic micro-motors. Sens. Actuat 20, 41–47 (1988).

Hod, O., Meyer, E., Zheng, Q. & Urbakh, M. Structural superlubricity and ultralow friction across the length scales. Nature 563, 485–492 (2018).

Liu, Z. et al. Observation of microscale superlubricity in graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 205503 (2012).

Song, Y. et al. Robust microscale superlubricity in graphite/hexagonal boron nitride layered heterojunctions. Nat. Mater. 17, 894–899 (2018).

Peng, D. et al. Load-induced dynamical transitions at graphene interfaces. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 12618–12623 (2020).

Liao, M. et al. UItra-low friction and edge-pinning effect in large-lattice-mismatch van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 21, 47–53 (2022).

Fennimore, A. M. et al. Rotational actuators based on carbon nanotubes. Nature 424, 408–410 (2003).

Zheng, Q. S. & Jiang, Q. Multiwalled carbon nanotubes as gigahertz oscillators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 045503 (2002).

Wu, Z., Huang, X., Xiang, X. & Zheng, Q. Electro-superlubric springs for continuously tunable resonators and oscillators. Commun. Mater. 2, 104 (2021).

Qu, C., Xiang, X., Ma, M. & Zheng, Q. Controlled movements in superlubric MEMS. J. Harbin Inst. Technol. (N. Ser.) 27, 45–57 (2020).

Qu, C. et al. Origin of friction in superlubric graphite contacts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 126102 (2020).

Peng, D. et al. 100 km wear-free sliding achieved by microscale superlubric graphite/DLC heterojunctions under ambient conditions. Natl Sci. Rev. 9, nwab109 (2022).

Kazimierczuk, M. K. Pulse-Width Modulated DC-DC Power Converters. John Wiley & Sons, (2015).

Liu, S.-W. et al. Robust microscale superlubricity under high contact pressure enabled by graphene-coated microsphere. Nat. Commun. 8, 14029 (2017).

Zhang, W.-M., Yan, H., Peng, Z.-K. & Meng, G. Electrostatic pull-in instability in MEMS/NEMS: A review. Sens. Actuat. A-Phys. 214, 187–218 (2014).

Han, X., Li, D., Cheng, Y., Li, G. & Wang, C. Analysis on edge effect of MEMS capacitance diaphragm gauge with square pressure-sensing diaphragm. Microsyst. Technol. 25, 2907–2914 (2019).

Fu, Y., Zhang, P., Verboncoeur, J. P. & Wang, X. Electrical breakdown from macro to micro/nano scales: a tutorial and a review of the state of the art. Plasma Res. Express 2, 013001 (2020).

Torres, J.-M. & Dhariwal, R. Electric field breakdown at micrometre separations in air and vacuum. Microsyst. Technol. 6, 6–10 (1999).

Padovani, A., La Torraca, P., Strand, J., Larcher, L. & Shluger, A. L. Dielectric breakdown of oxide films in electronic devices. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 07–62 (2024).

Huang, X. et al. Robust microscale structural superlubricity between graphite and nanostructured surface. Nat. Commun. 14, 2931 (2023).

Huang, X. et al. Microscale Schottky superlubric generator with high direct-current density and ultralong life. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–10 (2021).

Lu, X. K., Yu, M. F., Huang, H. & Ruoff, R. S. Tailoring graphite with the goal of achieving single sheets. Nanotechnology 10, 269–272 (1999).

Li, Q., Kim, K. S. & Rydberg, A. Lateral force calibration of an atomic force microscope with a diamagnetic levitation spring system. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 77, 065105 (2006).

Sader, J. E., Chon, J. W. M. & Mulvaney, P. Calibration of rectangular atomic force microscope cantilevers. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 70, 3967–3969 (1999).

Sader, J. E., Larson, I., Mulvaney, P. & White, L. R. Method for the calibration of atomic-force microscope cantilevers. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 66, 3789–3798 (1995).

Fitzpatrick, R. et al. Maxwell's Equations And The Principles Of Electromagnetism. (Laxmi Publications, Ltd., 2010).

Baron, A., Larouche, S., Gauthier, D. J. & Smith, D. R. Scaling of the nonlinear response of the surface plasmon polariton at a metal/dielectric interface. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B. 32, 9–14 (2015).

Akiyama, T. & Shono, K. Controlled stepwise motion in polysilicon microstructures. J. Microelectromech. S. 2, 106–110 (1993).

Donald, B. R., Levey, C. G., McGray, C. D., Paprotny, I. & Rus, D. An untethered, electrostatic, globally controllable MEMS micro-robot. J. Microelectromech. S. 15, 1–15 (2006).

Patton, S. & Zabinski, J. Failure mechanisms of a MEMS actuator in very high vacuum. Tribol. Int. 35, 373–379 (2002).

Eltagoury, Y. M., Soliman, M., Sabry, Y. M., Alotaibi, M. J. & Khalil, D. Electrostatic comb-drive actuator with high in-plane translational velocity. Micromachines 7, 188 (2016).

Sheikhaleh, A., Jafari, K. & Abedi, K. Design and analysis of a novel MOEMS gyroscope using an electrostatic comb-drive actuator and an optical sensing system. IEEE Sens. J. 19, 144–150 (2018).

Penskiy, I. & Bergbreiter, S. Optimized electrostatic inchworm motors using a flexible driving arm. J. Micromech. Microeng. 23, 015018 (2012).

Chiou, J.-C., Lin, Y.-J. & Kuo, C.-F. Extending the traveling range with a cascade electrostatic comb-drive actuator. J. Micromech. Microeng. 18, 015018 (2007).

Grade, J. D., Jerman, H. & Kenny, T. W. Design of large deflection electrostatic actuators. J. Microelectromech. S. 12, 335–343 (2003).

Zhao, Y. & Cui, T. Fabrication of high-aspect-ratio polymer-based electrostatic comb drives using the hot embossing technique. J. Micromech. Microeng. 13, 430 (2003).

Hou, M. T.-K. et al. Extending displacements of comb drive actuators by adding secondary comb electrodes. J. Micromech. Microeng. 16, 684 (2006).

Egawa, S., Niino, T. & Higuchi, T. Film actuators: Planar, electrostatic surface-drive actuators. IEEE Micro Electro Mechanical Systems. 9–14 (1991).

Conrad, H. et al. A small-gap electrostatic micro-actuator for large deflections. Nat. Commun. 6, 10078 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the financial support by National Natural Science Foundation of China (12002216, X.J., 11572173, Q.Z., 11890671, Q.Z., 51961145304, Q.Z., 11921002, Q.Z., 12425201, Z.X., 52090032, Z.X.), GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2020A1515110995, X.J., 2022B1515120040, X.J.), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JSGG20220831095802004, X.X., JCYJ20210324100600001, X.X.), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M761632, X.H.), China National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (BX20240183, X.H.), and Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Superlubricity Technology (ZDSYS20230626091701002, X.J.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.X. and Q.Z. conceptualized the experimental design for the research. X.X. and C.L. fabricated the device. X.H. and C.L. performed the measurements and analyzed the test data. X.H. and Y.S. conducted the structural design and simulation. J.N. assisted with testing the amount of injected charge; Z.X. contributed to the analysis of the mechanism. All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Diana Berman, Haojie Lang, and Ernst Meyer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, X., Xiang, X., Li, C. et al. Electrostatic in-plane structural superlubric actuator. Nat Commun 16, 493 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55078-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55078-0