Abstract

Irrespective of the specific see-through device, obtaining optimal transparency remains the primary goal. In this work, we introduce a general strategy to enhance the transparency of various see-through devices. We achieve this by structuring the colored functional materials into imperceptible three-dimensional mesh lines, addressing a common challenge in multi-layer structures where each layer causes a reduction in transparency due to their color or opacity. To overcome this limitation, we selectively integrate functional materials into micron-wide groove structures transforming functional layers to functional meshes. Regardless of the initial color of the functional material, the resulting functional mesh can exhibit a high transmittance of 88% (vs. air) under any operating state while maintaining its intended function within the device. We apply this strategy to fabricate proof-of-concept of devices such as electrochromic devices, supercapacitors, and zinc batteries, all of which exhibit remarkable overall transparency when compared to the multi-layer device.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

See-through devices have attracted much attention for their potential applications across diverse fields such as navigation1,2,3, medical research4,5, engineering6,7, and entertainment8,9. Positioned as a state-of-the-art technology focusing on the interaction between virtual information and the real world10,11,12, these devices include liquid crystal displays13, organic light-emitting diodes14 to energy storage devices such as supercapacitors15,16 or batteries17, and even cameras can be made see-through for device integration18. A key consideration for these see-through devices is the transparency in the off-state. In most cases, these devices (except the camera) have a multi-layer structure, necessitating a combination of highly transparent conductive electrodes and functional layers19,20. While several high-performance transparent conductive electrodes such as silver (Ag) grids and nanowires have been developed as alternatives to the traditional tin-doped indium oxide (ITO) glass, they only provide incremental improvements in the overall device transparency. The challenge lies in the color or opacity of the functional materials within the multi-layer device structure, which reduces overall device transparency. Efforts have been made to mitigate this issue by decreasing the film thickness or utilizing materials with high transparency. However, the 100% coverage of the functional materials across the surface continues to impact the transparency.

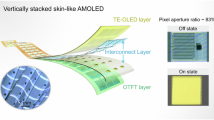

Herein, we propose a general strategy to enhance the transparency of various devices by structuring the colored functional layers into three-dimensional (3D) mesh lines imperceptible to the naked eye. Our approach is based on the recognition that, as long as the device structure sequence remains unchanged, not all functional materials have to be complete film layers to maintain charge transfer or ion transport functions (detailed in Supplementary Note 1). Using nanoimprinting technology, a periodic micron-wide mesh-line groove structure with adjustable depth (hundreds of nanometers to several micrometers) can form within the highly transparent UV curable resin film acting as a template21. Subsequently, current collecting and ion storing materials are filled inside of the groove structure in sequence to obtain an embedded 3D mesh with both electronic and ionic conductivities. The micron-wide mesh lines only take up 3 ~ 8% of the area of the entire surface (Fig. 1). In doing so, the transparency is no longer susceptible to the color or opacity of the functional materials, while maintaining the intended function of the materials.

In this work, we first chose an electrochromic device (ECD) as the main object of the study to demonstrate how the micro-structuring can enhance device transparency. As a non-emissive see-through device, the ECD has unique advantages such as eye-friendly characteristics, stepless color modulation, and energy efficiency12,22,23. Within the device structure, the counter electrode, which plays the role of ion storage and the conductive electrode, coordinates the redox reaction of the electrochromic layer, playing an essential role in charge balance for the normal operation of an ECD24,25,26. Unfortunately, the balance between transparency and ion storage capacity of the counter electrode is still not well established (detailed in Supplementary Note 2). By applying the structurization strategy, we successfully fabricated an embedded ion storage (EIS) mesh with a high transmittance of up to 88% (vs. air) over the whole visible region as a highly integrated counter-electrode material. After assembly, the whole device exhibited very similar color coordinates compared with the single electrochromic electrode at both colored and bleached states, indicating ultra-low color interference of the EIS mesh. In addition, benefiting from the decent ion storage capacity of the EIS mesh, a highly transparent symmetric supercapacitor and a highly transparent zinc battery were also successfully fabricated, which further demonstrated the effectiveness of transparency enhancement of the structurization strategy.

Results and Discussion

To quantitatively measure the occupied area of the mesh structure on the entire substrate, we define the filling ratio (ηf.r.) of the mesh structure as shown in Eq. 1, where w is the width of the mesh line, p is the mesh pitch, and h is the apothem (the schematic diagram of a single period of the honeycomb mesh is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1).

The equation indicates that the finer and sparser mesh lines, corresponding to lower ηf.r., leads to the higher transmittance of the entire surface. Another important parameter of the embedded mesh is the mesh depth, which is determined by the nanoimprinting template during the fabrication process. Due to the sharp decrease in the active area, compensation in volume must be made by deepening the mesh structure to ensure a similar amount of the functional material is used as in the traditional multi-layered device. For example, if a functional layer that is typically 100 nm thick, the depth of the targeted functional mesh (with a filling ratio of 5%) should be designed to be at least 2 μm. Considering the space for filling functional materials and the overall transparency of the obtained mesh, the honeycomb shape with a pitch of 100 μm, width of 4 μm and groove depth of 7 μm was optimized as the best structure (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3a, 4). By blading and annealing the Ag paste into the imprinted groove structure, a 3-μm-thick Ag mesh was obtained as the current collector (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b), leaving a depth of 4 μm to fill with functional material.

Considering the overall function of the mesh, the subsequent filling material should have the following properties: (I) reliable filling ability, guaranteeing it can be efficiently filled into the groove structure; (II) good electronic and ionic conductivity; (III) excellent stability, not only requiring its operational stability but also protecting the electrochemically unstable metallic mesh underneath. With the factors mentioned above in mind, an embedded ion storage (EIS) mesh was formulated, which serves as a highly integrated transparent electrode material suitable for various types of devices. Initially, to obtain an EIS mesh most suitable for ECDs, a blend of WO3 nanoparticles (NPs) and commercial poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)/poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) paste was chosen since it has been shown to have high electrochromic performance in traditional multi-layer devices27,28. The blend not only shows the advantages of the high ion capacity of WO3 and the high conductivity of PEDOT:PSS, but also the filling ability of the NPs and the film-forming ability of the blend. In addition, both WO3 and PEDOT:PSS are cathodic EC materials, which facilitates Li+ insertion/extraction (Eqs 2 and 3).

The WO3 NPs were synthesized by a modified Costa’s method29, which can be found in detail in Supplementary Fig. 5 and the Methods section. XRD measurement was carried out on the synthesized product after annealing at 120 °C (Supplementary Fig. 6), revealing the existence of a small amount of bound water, which may slightly improve the ion capacity of WO330. Three results of laser diffraction particle size distribution measurement of the dispersed NPs are plotted in Supplementary Fig. 7, showing an average size of ~65 nm of WO3 NPs, which were small enough for the NPs to serve as the filling material in the micron-sized groove structures. To analyze the blending uniformity of WO3 NPs and PEDOT:PSS paste, Raman spectra measurements were carried out on five samples with different blending ratios. Spectra with good signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios are plotted in Supplementary Fig. 8, where a prominent peak at 1442 cm-1 can be found in the spectrum of pure PEDOT:PSS corresponding to the Cα = Cβ stretching vibrations in the five-member ring of PEDOT31,32. With the incremental increase in WO3 amount, the relative intensity of the PEDOT:PSS peaks decrease, and three new peaks at 650, 810, and 947 cm-1 gradually appear. The band around 950 cm-1 is assigned to the stretching mode of the terminal W = O bond, which is typical for all types of tungsten trioxide hydrates, and the bands at 650 and 810 cm-1 can be attributed to the stretching modes of the O-W-O bridging oxygens33,34. Notably, compared to the Raman spectrum of neat WO3, an evident Raman shift at 673 cm-1 vanishes after blending with PEDOT:PSS, and a red shift around the peak at 641 cm-1 is also found in the FTIR spectra (Supplementary Fig. 9), indicating the possible chemical interaction between the two materials. This is further verified by the results of the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and the ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) measurements (Supplementary Figs. 10-12). Conductivities (σ) of the blends were also measured and calculated by Eq. 4 using the test results from Supplementary Fig. 13:

where ρ is the resistivity, L is the length (2 cm), R is the resistance, and S is the cross-sectional area. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 14, the conductivity of the pure PEDOT:PSS paste was calculated to be 23.2 S/cm and decreased to 10.9 S/cm after blending with WO3 NPs in a 2:1 ratio. The conductivity of the blend dropped sharply with the further addition of WO3. This is because the presence electrically insulating WO3 NPs disrupts the continuity of the PEDOT:PSS phase. However, compared to the neat WO3 sample, the addition of the PEDOT:PSS paste did improve the conductivity. After blading and annealing the blended paste inside of the groove structure, the EIS mesh was fabricated (Supplementary Fig. 5). Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements were carried out on the EIS meshes with five different blending ratios of the ion storage paste. Owing to the jelly-like nature (bringing inconvenience to the blading process) and low solid content (~5%) of the pure PEDOT:PSS paste, the PEDOT:PSS EIS mesh exhibited such a low ion capacity that it could hardly storage any amount of ions for the electrochromic process. With increasing WO3 proportion, more solid components filled the groove structure (Supplementary Figs. 3c-f and 15), and the ion capacity of the EIS mesh increased (Supplementary Fig. 16). Notably, the neat WO3 EIS mesh did not exhibit the highest ion capacity due to the lack of conductivity. Microcracks were also observed across the mesh lines (Supplementary Fig. 15), which might expose the Ag mesh underneath directly to the electrolyte, leading to severe side reactions. Therefore, the blending ratio of WO3:PEDOT:PSS paste = 2:1 was determined to be the most suitable for fabricating the EIS mesh.

Schematic diagrams of the EIS mesh structure are illustrated in Fig. 2a and 2d inset with a traditional counter electrode structure for comparison. During ion doping, the ion storage material may undergo slight additional coloring due to its electrochromic properties, causing further transmittance reduction in the traditional counter electrode. In contrast, the EIS mesh counter electrode confines the electrochromic reactions within the grooves, ensuring that the remainder of the film is unaffected by the reactions and thus remains transparent. Figure 2b and c are the SEM images of the EIS mesh with a 100 μm mesh period and filled with the blend of the optimized ratio (magnified in Supplementary Fig. 17). The corresponding EDS mapping and TOF-SIMS profiles are also given in Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19. It can be seen from the UV-vis spectra (Fig. 2d) that the polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate, PET with Ag mesh, PET with Ag and EIS mesh have similar spectra, highlighting the effectiveness of our structuring strategy. Notably, compared to the ~90% transmittance of the bare PET substrate, the additional mesh lines cause only a minor decrease in transmittance because they only cover 4.6% of the substrate area, resulting in a transmittance of 88% across the whole visible region. A more conventional spin-coated WO3 film (~200 nm) on ITO glass was fabricated as a comparison to study the optical and electrochemical performance of the EIS mesh. A three-electrode system was applied by submerging the EIS mesh or the spin-coated film into the electrolyte and connecting it to the working electrode of an electrochemical station with a platinum (Pt) wire as the counter electrode and Ag/AgCl as the reference. By applying different voltages ranging from 0 to −0.8 V, spectra of the EIS mesh almost overlapped with each other with only a slight fluctuation of less than 0.2%, as shown in Fig. 2e and the inset, indicating the unchanging color characteristics of our counter electrode. Comparatively, the spin-coated WO3 film turned blue with increasing applied voltage as continuous insertion of Li+ proceeded (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21), which greatly hinders its application as the counter electrode material for ECDs (Supplementary Figs. 22 and 23). CV measurements were subsequently carried out to study the ion capacity of the electrodes. Figure 2g plots the in-situ spectra at 700 nm with the CV input voltage. Still, no visible fluctuation can be seen in the time-dependent spectra of the EIS mesh, while the spin-coated film exhibits a modulation of ~35%. By integrating the close plot of the CV curves in Fig. 2h (detailed in Supplementary Note 3), the ion capacities of the electrodes can be calculated to be 5.98 and 11.08 mC/cm2 for the EIS mesh and the spin-coated WO3 film, respectively. Although the occupied area of the EIS mesh is just 4.6% of the spin-coated film, the ion capacity can be high up to 54% of the conventional film, due to the depth of the embedded structure. Moreover, galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) measurement was also applied to the EIS mesh (Fig. 2i, j) with a consequential areal specific capacitance of 2.68 mF/cm2 under 0.1 mA/cm2 (detailed in Supplementary Note 4), which is a remarkable value among the reported flexible transparent supercapacitor materials16,20,35,36,37.

a Schematic diagrams and corresponding optical images of the electrodes. IS: ion storage, ITO: indium tin oxide, EIS: embedded ion storage. b Optical microscopy image of the honeycomb structure of EIS mesh. c Magnified image of the mesh-line junction captured by SEM. d Transmittance spectra (vs. air) of PET and the derived meshes. Inset: schematics of the cross sections. e Transmittance spectra (vs. air) of the EIS mesh under different applied voltages. Inset: magnification of the spectra from 600 to 700 nm. f Transmittance spectra (vs. air) of the spin-coated WO3 film (on ITO glass) under different applied voltages. g Transmittance (vs. air) of the EIS mesh and spin-coated WO3 film under a cyclic voltammetry input voltage. h The corresponding CV curves. i The GCD curve and j the calculated areal capacitance of the EIS mesh at different current densities.

Taking advantage of the existence of the electrolyte, which allows for the unoriented migration of ions, the EIS mesh can successfully be used as the counter electrode in an ECD, as shown in Fig. 3a. As the most widely used electrochromic polymer (ECP) material38, ECP-magenta was spin-coated onto the ITO glass as the working electrode (~280 nm) to study the color interference of the EIS mesh (Supplementary Fig. 24). We spin-coated two ECP-magenta electrodes and assembled one of them into a device with the EIS mesh. Both the electrode and the device were switched to their colored and bleached states for the comparison of spectra and color coordinates (Fig. 3b). Figure 3c plots the UV-vis spectra of bare ITO glass, spin-coated ECP-magenta electrode, and the assembled device. It can be seen from the spectra that although ECP-magenta is known for its high transparency at the bleached state, it still leads to an inevitable decrease in the transmittance of the device, which is likewise for the highly transparent electrolyte. By transferring the spectra into CIE L*a*b* color coordinates (detailed in Supplementary Note 5), no obvious gamut shift can be found in both the colored and bleached states of the device versus single electrode (Fig. 3d), indicating very limited color interference of the EIS mesh when used as the counter electrode (Supplementary Note 6, Supplementary Table 1). In addition, the cyclic stability of the device should also be studied as an important performance index of the EIS mesh. CV measurement was first carried out to confirm the suitable switching voltages, which were finally determined to be +1.2/−0.4 V according to the plateaus of the CV curves in Fig. 3e. After 2000 operation cycles, modulation of the device dropped only 4% compared to the initial 48% (Fig. 3f). Moreover, after 6000 switching cycles, modulation of the device can totally recover to the initial state by applying a higher voltage at 1.5 V (Supplementary Fig. 25), illustrating the good cyclic stability of the EIS mesh as the counter electrode. Besides, owing to the flexibility of the EIS mesh and the solubility of ECP-magenta, a patterned flexible ECD is also fabricated with the ability to change colors under bending (Supplementary Fig. 26 and Supplementary Movie 1).

a Schematic diagram of the electrochromic device. ITO: indium tin oxide, ECP: electrochromic polymer, EIS: embedded ion storage. b Optical images of the device (active area 2 × 2 cm2) and a single electrode (spin-coated ECP-magenta on 2.5×3 cm2 ITO glass) in both colored and bleached states. c Transmittance spectra (vs. air) of the device and electrode in both colored and bleached states compared with bare ITO glass. d Calculated CIE L*a*b* color coordinates according to the spectra. e CV curves of the device under different scan rates. f Transmittance of the device at 550 nm under 2000 cycles, stimulated with 1.2/−0.4 V for bleaching/coloration and the step of 5 s.

As a demonstration, a pair of sunglasses was fabricated using ECP-blue as the electrochromic layer (~435 nm) and EIS mesh as the counter electrode (Supplementary Movies 2 and 3); the structure is illustrated in detail in Fig. 4a. Two independent coin cell batteries were used as the driven source and connected to the electrochromic (EC) lens by electrical circuits, as shown in Fig. 4b. In the series circuits, each lens was measured to consume ~27 mC charge for an entire electrochromic switch, indicating low power consumption of the EC sunglasses. By applying different voltages or controlling the stimulation time, the EC lens exhibits a stepless color shift from blue to highly transparent, and the modulation at 600 nm is about 47% (Fig. 4c). The switching speed of the EC lens was also tested on 3 different points, as shown in Fig. 4d and e. Owing to the highly conductive Ag mesh underneath, the switching time of points 2 and 3 is almost the same and just one second later than point 1 (as the electrodes of the lens are designed at the position close to the nose bridge), which means the mid and the edge area of the lens share the same switching speed, indicating a uniform electrochromic process over the whole area. In addition, the EC lens was also used as the dimming module on a pair of augment reality (AR) glasses (BT-40, Epson) to reveal the feasibility of application (Supplementary Movie 4). Figure 4f is a simplified optical path figure of the AR glasses. When capturing the waveguide images inside of a bright studio (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 27), words on the background plate are clear to identify owing to the high transparency of the EC dimming module in off mode. However, the displayed logo is mixed up with the adjacent background, and we can hardly distinguish the overlapped area (Fig. 4h). After switching the dimming module to on mode, the background words could still read because of the low haze and suitable transmittance of the ECD. Meanwhile, the waveguide images became much more apparent as the dimming module effectively eliminated the interruption of the bright background, indicating a promising future for ECDs with an EIS mesh counter electrode as the dimming module for the see-through displays.

a Schematic diagram of the electrochromic (EC) sunglasses. EIS: embedded ion storage, ECP: electrochromic polymer. b The drive circuit of the EC sunglasses and the power consumption of each coin cell battery for an entire electrochromic switching per lens. (c) Transmittance spectra (vs. air) of the EC lens. d Switching speed of the 3 points (Point 1: next to the electrodes; Point 2: middle of the lens; Point 3: distal of the lens.) on the lens. e Optical images of the EC sunglasses in both colored and bleached states. f Schematic diagram of the optical path of augment reality (AR) glasses with an EC dimming module. g Schematic diagram of the placement of objects for capturing the waveguide image. h A logo displayed by the AR glasses in a bright studio with the EC dimming module in off (left) / on (right) mode.

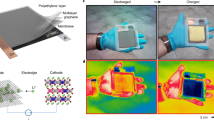

Benefiting from the decent ion storage capacity (Fig. 2j), the EIS mesh is also used as the active electrodes of transparent energy storage devices. Figure 5a illustrates the device structure of a symmetric supercapacitor with a high transmittance of more than 70% (vs. air) over the whole visible region (Fig. 5b, c), which also exhibits a constant value during the charge/discharge process (Supplementary Fig. 28), further demonstrating the unchanging color characteristics of the EIS mesh. It can be seen from Fig. 5d that the CV curves of the highly transparent supercapacitor are not in the shape of rectangular, indicating that the ion capacity is mainly contributed by the redox reactions of WO3. GCD measurement is also carried out to calculate the areal capacitance, and the results are plotted in Fig. 5e, f. Regrettably, the lithium ions inserted in WO3 are not able to extract completely at a 0 V potential (Fig. 2h and Eq. 2), which means that the lithium ions will gradually accumulate inside of the EIS mesh, leading to unsatisfying capacitance and cyclic performance of the highly transparent supercapacitor.

a Schematic diagram of the transparent supercapacitor with both embedded ion storage (EIS) mesh as the active electrodes. b Optical images of the transparent supercapacitor. c Transmittance spectrum (vs. air) of the transparent supercapacitor. d CV curves of the transparent supercapacitor under different scan rates. e GCD curves and f the calculated areal capacitance of the transparent supercapacitor at different current densities.

As another type of energy storage device, zinc battery has a relatively larger electrochemical window, which can make better use of the ion storage property of the EIS mesh. A highly transparent zinc battery was assembled in the structure illustrated in Fig. 6a using EIS mesh as the cathode and a water-in-salt (WIS) electrolyte. The optical image and corresponding transmittance spectrum are shown in Supplementary Figs. 29 and 30, respectively. CV curves at different scan rates are shown in Fig. 6c, which show similar shapes to those of the supercapacitor except for two additional small peaks at 0.6 and 0.9 V, respectively, corresponding to the insertion/extraction of zinc ions39. Figure 6d plots the GCD curves of the zinc battery at different current densities, exhibiting fairish rate performance and good coulombic efficiency (Fig. 6e). Cyclic performance of the zinc battery was evaluated at a current density of 200 μA/cm2 in the potential window between 0 and 1.2 V (Fig. 6b). During 2000 operation cycles, the specific capacity of the zinc battery exhibits a slight uptrend while the coulombic efficiency maintains around 100%. It can be seen from the insets of Fig. 6b that the charge/discharge time prolongs with the cyclic process, and more obvious plateaus appear on the GCD curve, indicating a continuous activation process of the zinc battery. Furthermore, two batteries in series (with a total active area of 8 cm2) were used to drive a digital timer, and the screen brightness showed no obvious change after 20 min of operation (Fig. 6f, g and Supplementary Movie 5), illustrating certain practicability of the transparent zinc battery.

a Schematic diagram of the transparent battery with zinc (Zn) mesh as the anode and embedded ion storage (EIS) mesh as the cathode. WIS: water-in-salt. b Cyclic performance of the transparent battery at 200 μA/cm2. Inset: GCD curves of the transparent battery at different cycle numbers (corresponding to the three orange points on the gray plot). c CV curves of the transparent battery under different scan rates. d Specific capacity and e corresponding coulombic efficiency of the transparent battery at different current densities (calculated from the GCD curves). f Schematic and g optical images of the power supply system (two transparent batteries in series) of a digital timer.

Finally, we want to emphasize that the filling material in the groove structure can be altered and is not limited to the WO3 and PEDOT:PSS combination. For electrochromic materials with different ion-storing requirements, other materials can be applied without considering their initial color or opacity, because our strategy can always make the overall layer transparent. For example, an embedded nickel oxide mesh can act as the anion storage in an ECD using PEDOT:PSS as the electrochromic layer (Supplementary Fig. 31). Carbon materials can also be processed to render a black film translucent. (Supplementary Fig. 32). Moreover, it has to be admitted that both the transparent supercapacitor and zinc battery exhibit relatively inferior capacitance (capacity) than the traditional nontransparent ones owing to the dramatic decrease in the mass loading of active materials. However, by utilizing functional materials with higher ion storage properties (e.g., MXene16 and MnO240), energy storage devices of sufficient capacitance (capacity) and high transparency will be in prospect, leading to significant advances in the integration of see-through devices.

By utilizing the structurization strategy, a highly transparent functional mesh, EIS mesh, was fabricated through an all-printing additive method with a high transmittance of up to 88% (vs. air) and decent ion storage capacity (areal specific capacitance of 2.68 mF/cm2 under 0.1 mA/cm2). Owing to the highly integrated structure of the EIS mesh, it was successfully used in three different types of see-through devices as the counter electrode for an ECD, the active electrode for a symmetric supercapacitor, and the cathode for a zinc battery, which all exhibit remarkable enhancement in the transparency of the entire device. As a general strategy, by optimizing the filled functional material and device structure, this could be a feasible and facile approach to enhance the transparency of more types of see-through devices.

Methods

Materials

Tungsten powder (1~5 μm), hydrogen peroxide (30%), lithium perchlorate (LiClO4), lithium bromide (LiBr), zinc sulfate (ZnSO4), zinc chloride (ZnCl2), zinc acetate (ZnAc2), sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), boric acid (H3BO3), polyethylenimine (PEI), poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) and 2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (DMPAP) were purchased from Aladdin. Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) and propylene carbonate (PC) were purchased from Adamas. Ethanol and xylene were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. PEDOT:PSS paste was purchased from Agfa and PEDOT:PSS PH1000 was purchased from Heraeus Clevios. Ag paste was purchased from Ningbo Flexographic Electronic Technology Co., Ltd. ITO glass and PET-ITO were purchased from Yiwu QingYue Optoelectronics Technology Institute Co., Ltd. ECP powder (including ECP-magenta and ECP-blue), ready-made Ni mesh and the materials for fabricating embedded mesh structure (including PET and UV resin) were provided by OPQ Display Inc., Suzhou.

Preparation of the blended paste

The WO3 nanoparticles were synthesized based on a modified sol-gel route. Metallic tungsten powder (3.4 g) was added to hydrogen peroxide (50 g) in an ice-water bath and stirred until fully dissolved; this process might take several hours. The resulting clear and transparent solution (peroxopolytungstic acid, PPTA) was then heated to 100 °C under stirring in a round-bottom flask with a reverse-flow cooling system, giving a yellow solution after 2 h and a pale-yellow suspension after another 5 h. The suspension was divided into several centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 4300 g for 20 min to collect the precipitate, and two more centrifugation processes were subsequently applied with additive ethanol for washing (as the residual H2O2 could affect the performance of WO3). The synthesized WO3 nanoparticles were directly blended with the PEDOT:PSS paste in proportion without further annealing or freeze drying to retain the surface ligands.

Preparation of the EIS mesh

First, a UV-curable resin was filled between the PET substrate and Ni template for nanoimprinting. After exposed to the UV source, the groove structure was formed on PET and could be easily peeled off from the template. The Ag paste was then bladed into the grooves and annealed at 120 °C for 20 min to obtain the embedded Ag mesh. The IS paste was processed in like manner to obtain the EIS mesh. A schematic diagram of the fabrication process is attached in the Supplementary Information as Supplementary Fig. 5 for a clearer explanation.

Electrochromic device assembly

ECP powder was dissolved in xylene with a concentration of 4 wt% and spin-coated on the plasma-processed ITO glass (or Ni mesh/PEDOT:PSS PH1000) at 1500 rpm for 40 s, then annealed at 120 °C for 10 min as the working electrode. A mixture of 1 M LiClO4, PMMA (20 wt%), PEGDA (40 wt%), and DMPAP (0.4 wt%) in PC served as the UV curable electrolyte, and the EIS mesh served as the counter electrode. The device was laminated by 3 M double-sided tape (shaped by laser cutting) with the electrolyte in between and then exposed to a 50 W UV source for 30 s to form an all-solid-state ECD.

Transparent symmetric supercapacitor assembly

EIS mesh was used as the active electrode, and the same UV curable electrolyte mentioned above was used for sandwiching the all-solid-state supercapacitor.

Transparent zinc battery assembly

Metallic Zn was electroplated inside of the groove structure of embedded Ni mesh using a mixture of ZnSO4 (3 g), Na2SO4 (3 g), H3BO3 (0.5 g), and PEI (0.1 g) in 20 mL of DI water as the electrolyte and a Zn plate as the reference and counter electrode. A constant current density of 0.1 mA/cm2 was applied on the Ni mesh for 10 min to obtain the embedded Zn mesh as the anode of the battery. The WIS electrolyte consists of 10 M ZnCl2, 10 M ZnAc2, and 20 M LiBr, and all the salt can fully dissolve in DI water under stirring at 120 °C. After cooling down to room temperature, the WIS electrolyte is still of certain mobility, which is suitable for sandwiching between the EIS mesh and Zn mesh to obtain the transparent zinc battery.

Characterization

The crystalline structure of the synthesized WO3 was examined on a Bruker AXS D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (XRD) with a Cu Kα radiation target (40 V, 40 A). Size distributions of the nanoparticles were measured by particle size and zeta potential analyzer (SZ-100, HORIBA). The Raman spectra were recorded by inVia Qontor confocal 498 Raman spectrometer (Renishaw). Resistances of the samples for calculating conductivity were measured with a typical multimeter. Film thickness was obtained from a step profiler (DEKTAK XT, Bruker). Morphologies of the EIS meshes were observed by SEM (S-4800 and Regulus8230, Hitachi), and the EDS mapping was performed on the same sample by FE-ESEM (Quanta FEG 250). The width and depth of mesh lines in the groove structures were characterized by optical microscopy (color 3D laser scanning microscope VK-9710, KEYENCE), and the elements inside were further studied by TOF-SIMS (TOF.SIMS5-100). Transmittance data were collected on a UV–visible spectrometer (Lambda 750, PerkinElmer). A three-electrode system was used for the electrochromic and electrochemical performance measurements in 1 M LiClO4/PC with Pt wire or carbon rod as the counter electrode and Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode, respectively, and a two-electrode system was used for the measurements of devices. Electrochemical behaviors were studied via cyclic voltammetry (CV), chronoamperometry (CA), amperometric i-t curves (i-t), and chronopotentiometry (CP) on an electrochemical workstation (CHI 760, CH Instruments, Inc., China).

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Extra data are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Peleg-Adler, R., Lanir, J. & Korman, M. The effects of aging on the use of handheld augmented reality in a route planning task. Comput. Hum. Behav. 81, 52–62 (2018).

Rameau, F., Bailo, O., Park, J., Joo, K. & Kweon, I. S. Real-time multi-car localization and see-through system. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 130, 384–404 (2022).

Rameau, F. et al. A real-time augmented reality system to see-through cars. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 22, 2395–2404 (2016).

Chen, X. et al. Development of a surgical navigation system based on augmented reality using an optical see-through head-mounted display. J. Biomed. Inform. 55, 124–131 (2015).

Hu, X., Baena, F. R. Y. & Cutolo, F. Head-mounted augmented reality platform for markerless orthopaedic navigation. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 26, 910–921 (2022).

Schiavi, B., Havard, V., Beddiar, K. & Baudry, D. BIM data flow architecture with AR/VR technologies: Use cases in architecture, engineering and construction. Autom. Constr. 134, 104054 (2022).

Solmaz, S. & Van Gerven, T. Automated integration of extract-based CFD results with AR/VR in engineering education for practitioners. Multimed. Tools Appl. 81, 14869–14891 (2021).

Eisert, P., Liu, Y., Mu Lee, K., Stricker, D. & Thomas, G. Introduction to the special section on augmented video. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 27, 713–715 (2017).

Liu, H. X., Holopainen, J. & Wagner, C. A design strategy for Geo AR mobile game sustainable success emphasizing game completeness. Entertain. Comput. 46, 100569 (2023).

Wakunami, K. et al. Projection-type see-through holographic three-dimensional display. Nat. Commun. 7, 12954 (2016).

Yin, K. et al. Advanced liquid crystal devices for augmented reality and virtual reality displays: principles and applications. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 161 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. A see-through electrochromic display via dynamic metal-ligand interactions. Chem 7, 1308–1320 (2021).

Li, J., Bisoyi, H. K., Tian, J., Guo, J. & Li, Q. Optically rewritable transparent liquid crystal displays enabled by light-driven chiral fluorescent molecular switches. Adv. Mater. 31, 1807751 (2019).

Jeong, S. Y. et al. Highly air-stable, flexible, and water-resistive 2D titanium carbide MXene-based RGB organic light-emitting diode displays for transparent free-form electronics. ACS Nano 17, 10353–10364 (2023).

Cheng, T., Zhang, Y.-Z., Zhang, J.-D., Lai, W.-Y. & Huang, W. High-performance free-standing PEDOT:PSS electrodes for flexible and transparent all-solid-state supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 10493–10499 (2016).

Zhang, C. J. et al. Transparent, flexible, and conductive 2D titanium carbide (MXene) films with high volumetric capacitance. Adv. Mater. 29, 1702678 (2017).

Chen, T. et al. Freestanding 3D metallic micromesh for high-performance flexible transparent solid-state zinc batteries. Small 18, 2201628 (2022).

Ma, Y., Gao, Y., Wu, J. & Cao, L. Toward a see-through camera via AR lightguide. Opt. Lett. 48, 2809–2812 (2023).

Liu, L., Cao, K., Chen, S. & Huang, W. Toward see‐through optoelectronics: Transparent light‐emitting diodes and solar cells. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8, 2001122 (2020).

Zhao, W. et al. Flexible transparent supercapacitors: Materials and devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2009136 (2020).

Hu, Z. et al. Ultra-low resistivity copper mesh as embedded current collector layer for inkjet-printed flexible electrochromic device realizing fast response and uniform coloration. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2201037 (2022).

Gu, C., Jia, A. B., Zhang, Y. M. & Zhang, S. X. Emerging electrochromic materials and devices for future displays. Chem. Rev. 122, 14679–14721 (2022).

Bulloch, R. H., Kerszulis, J. A., Dyer, A. L. & Reynolds, J. R. Mapping the broad CMY subtractive primary color gamut using a dual-active electrochromic device. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 6623–6630 (2014).

Eric Shen, D., Österholm, A. M. & Reynolds, J. R. Out of sight but not out of mind: the role of counter electrodes in polymer-based solid-state electrochromic devices. J. Mater. Chem. C. 3, 9715–9725 (2015).

Yu, L., Xing, X., Fang, D. & Meng, H. Highly transparent conjugated polymer as the counter electrode in electrochromic smart windows. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2201423 (2022).

He, J. et al. Highly transparent crosslinkable radical copolymer thin film as the ion storage layer in organic electrochromic devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 18956–18963 (2018).

Shao, Z. et al. All-solid-state proton-based tandem structures for fast-switching electrochromic devices. Nat. Electron. 5, 45–52 (2022).

Cai, G., Darmawan, P., Cheng, X. & Lee, P. S. Inkjet printed large area multifunctional smart windows. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1602598 (2017).

Costa, C., Pinheiro, C., Henriques, I. & Laia, C. A. T. Inkjet printing of sol-gel synthesized hydrated tungsten oxide nanoparticles for flexible electrochromic devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4, 1330–1340 (2012).

Wang, Z. et al. Remarkable near-infrared electrochromism in tungsten oxide driven by interlayer water-induced battery-to-pseudocapacitor transition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 33917–33925 (2020).

Shi, Y. et al. Designed growth of WO3/PEDOT core/shell hybrid nanorod arrays with modulated electrochromic properties. Chem. Eng. J. 355, 942–951 (2019).

Jeong, W. et al. Enhancing the conductivity of PEDOT:PSS films for biomedical applications via hydrothermal treatment. Biosens. Bioelectron. 171, 112717 (2021).

Santato, C., Odziemkowski, M., Ulmann, M. & Augustynski, J. Crystallographically oriented mesoporous WO3 films: synthesis, characterization, and applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 10639–10649 (2001).

Daniel, M. F., Desbat, B., Lassegues, J. C., Gerand, B. & Figlarz, M. Infrared and Raman study of WO3 tungsten trioxides and WO3, xH2O tungsten trioxide tydrates. J. Solid State Chem. 67, 235–247 (1987).

Cheng, T. et al. Inkjet-printed flexible, transparent and aesthetic energy storage devices based on PEDOT:PSS/Ag grid electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 13754–13763 (2016).

Xu, J. L. et al. Embedded Ag grid electrodes as current collector for ultraflexible transparent solid-state supercapacitor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 27649–27656 (2017).

Kiruthika, S., Sow, C. & Kulkarni, G. U. Transparent and flexible supercapacitors with networked electrodes. Small 13, 1701906 (2017).

Knott, E. P. et al. A minimally coloured dioxypyrrole polymer as a counter electrode material in polymeric electrochromic window devices. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 4953–4962 (2012).

Li, H., Firby, C. J. & Elezzabi, A. Y. Rechargeable aqueous hybrid Zn2+/Al3+ electrochromic batteries. Joule 3, 2268–2278 (2019).

Ye, X. et al. Unraveling the deposition/dissolution chemistry of MnO2 for high-energy aqueous batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 1016–1023 (2023).

Acknowledgements

W.S. acknowledges the financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFBYFB3603900 and 2022YFB3606500). Y.Y. acknowledges the financial support from the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20210125). X.C. acknowledges the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52103294). Y.Y. and C.K.L. acknowledge the funding from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology. The authors are grateful for the technical support of Nano-X from Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics (SINANO), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). We also would like to thank Suzhou Nanotest Technology Co., Ltd. for the SEM test.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.H., X.W., and W.S. conceived the project. Z.H., X.T., X.W., and Y.Y. designed the experiments. Z.H., X.T., S.N., X.C., W.X., and C.H. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. X.M., Z.M., and P.T. provided the AR glasses and assisted in the experiments. Z.H., Y.Y., and C.K.L. co-wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Guangming Nie, Xiaopeng Qi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Z., Tang, X., Yi, YQQ. et al. A general strategy to achieve see-through devices through the micro-structuring of colored functional materials. Nat Commun 15, 10836 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55133-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55133-w