Abstract

Heavy metals complexed with organic ligands are among the most critical carcinogens threatening global water safety. The challenge of efficiently and cost-effectively removing and recovering these metals has long eluded existing technologies. Here, we show a strategy of coordinating mediator-based electro-reduction (CMBER) for the single-step recovery of heavy metals from wastewater contaminated with heavy metal-organic complexes. In CMBER, amidoxime with superior coordinating abilities over traditional ligands is immobilized by an amidoximation reaction onto a flow-through electrode that concurrently functions as a filtration device. This unique process spontaneously captures heavy metal ions at the -N-OH and -NH2 groups of the amidoxime from their complexes without external energy input (ΔG of amidoxime mediator with Cu(II): −6.59 eV), followed by direct in situ electro-reduction for metal recovery. The reduction of captured Cu(II) to Cu(0) regenerates the amidoxime’s active sites, enabling continuous capture of Cu(II). Operating at a voltage of 3 V and a water flux of 250 L m−2 h−1, the CMBER system achieves a Cu(II) recovery rate of 97.6% and demonstrates an energy efficiency of 340.1 g kWh−1. This energy efficiency significantly outperforms existing technologies, showing a nearly fivefold improvement. CMBER creates a new dimension for cost-effective resource recovery and water purification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heavy metals rank among the most critical carcinogens threatening global water safety1,2,3,4, particularly when they react with co-existing organic ligands like natural organic matter and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)5,6. These reactions lead to the formation of highly toxic, carcinogenic, and stable heavy metal-organic complexes7,8,9. Due to the strong affinity between heavy metal and organic ligands10, treating these complexes without generating secondary pollution presents a significant challenge for conventional methods such as membrane separation11, adsorption12, and precipitation13,14. Given these challenges and the need to meet sustainable metal recycling goals15,16, it is crucial to develop wastewater treatment techniques that can effectively break the metal-organic bonds in these complexes while concurrently recovering the valuable metal resources.

The critical step in releasing heavy metal ions from heavy metal-organic complexes for subsequent reduction and recovery involves breaking the heavy metal-organic coordination bonds13,17. Existing technologies, including advanced oxidation10,18,19,20, photo-oxidation21,22,23, electro-oxidation8,24,25, discharge plasma oxidation26,27,28 and electro-reduction29,30, generally depend on potent oxidants or substantial energy input to disrupt these complex structures, accomplishing this critical step inefficiently31. These methods utilize energy (or chemicals) to break the heavy metal-organic coordination7,32,33, and generally require a separate treatment process to recover the heavy metals34. Therefore, creating an efficient method for heavy metal recovery without damaging the organic ligand represents a crucial challenge in addressing these limitations.

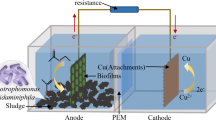

In this work, we present a strategy utilizing coordinating mediator-based electro-reduction (CMBER) for the efficient, single-step recovery of heavy metals from wastewater containing heavy metal-organic complexes (Fig. 1). By employing amidoxime, which has superior affinity for heavy metal ions compared to traditional ligands in complexes, our method facilitates the spontaneous capture of heavy metal ions directly from their complexes without the need for external energy. Subsequently, these metals captured by amidoxime groups can undergo direct in situ electro-reduction for recovery. In our approach, we eliminate the need to break heavy metal-organic complexes using potent oxidants generated at the anode, distinguishing our work from existing literature. Operating at a voltage of 3 V and a water flux of 250 L m−2 h−1, the CMBER system has successfully achieved a Cu(II) recovery rate of 97.6% and demonstrated an energy efficiency of 340.1 g kWh−1, significantly surpassing existing technologies. The CMBER can also achieve ~95.0% recovery of Ni(II) from Ni(II)-EDTA and Pb(II) from Pb(II)-EDTA. Moreover, the process regenerates amidoxime’s active sites during the electro-reduction of captured metal ions (e.g., from Cu(II) to Cu(0)), thereby enabling the continuous capture and recovery of Cu(II) over extended periods. The strategy creates a new dimension for cost-effective resource recovery and water purification.

The strongly coordinating mediator-based cathode spontaneously captures heavy metal ions directly from their complexes without the need for external energy and subsequently reduce them in situ to recover the metals. The process regenerates amidoxime’s active sites during the electro-reduction of captured heavy metal ions to heavy metals, thereby enabling the continuous capture and recovery of heavy metal ions over extended periods.

Results

Creation of strong coordinating mediator-based cathode

The critical factor in achieving spontaneous capture of heavy metal ions from complexes involves the development of an amidoxime-functionalized cathode. Initially, polyacrylonitrile-modified carbon felt (PCF) was created by immersing commercial carbon felt (CF) into a mixture of polyacrylonitrile (PAN) and carbon black, dispersed in dimethylformamide (DMF). This PCF served as the foundation for the subsequent preparation of amidoxime mediator-functionalized PCF (APCF) through an amidoximation reaction35, which involved converting -C ≡ N groups to amidoxime groups in the presence of Na2CO3 and hydroxylamine hydrochloride (NH2OH·HCl), as outlined in the Methods section and Supplementary Fig. 1. Field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) images reveal that both PCF and APCF are composed of fibers ~20 μm in diameter covered with a thin polymer layer on the surface (Supplementary Fig. 2). Moreover, these images confirm the homogeneous distribution of surface-bound carbon black nanoparticles on both PCF and APCF, a modification aimed at enhancing electrode conductivity.

The incorporation of the amidoxime group into the APCF electrode was verified through FT-IR and XPS analyses. In the APCF spectra (Fig. 2a), there are no characteristic peaks at 2250 cm−1 corresponding to the C ≡ N group, which represents the stretching vibration of C ≡ N in PCF36. Instead, new characteristic peaks appear at 905.4, 1595.3, 3183.4, and 3327.1 cm−1, corresponding to the N-O, C = N, N-H, and O-H bonds35, respectively, indicating the almost complete conversion of C ≡ N into amidoxime groups. To further analyze the structure of organic polymers in PCF and APCF, solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (SSNMR) tests were performed. Similarly, no characteristic peaks corresponding to the C ≡ N group were observed in the 13C spectra of organic polymers from APCF (Supplementary Fig. 3), further demonstrating that the C ≡ N group in PCF has been largely converted to the amidoxime groups.

a Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra of polyacrylonitrile-modified carbon felt (PCF) and amidoxime mediator-functionalized PCF (APCF). b Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves of carbon felt (CF), PCF and APCF electrodes in a 5 mM Cu(II)-EDTA and 0.5 M Na2SO4 electrolyte at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The electrochemical characteristics of the APCF were evaluated using Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) in a 0.5 M Na2SO4 solution and Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) in an electrolyte solution containing 5 mM Cu(II), 6 mM EDTA, and 0.5 M Na2SO4 to mitigate the impact of concentration polarization. An elevated concentration of EDTA was employed to ensure complete complexation of all Cu(II) ions with EDTA, forming Cu(II)-EDTA complexes (the six-coordination complex). The slopes of the straight lines in the EIS curves for the three electrodes—PCF, CF, and APCF—increased sequentially, while the contact angle with water decreased correspondingly. This demonstrated a clear correlation between diffusion impedance and hydrophilicity (Supplementary Fig. 4)37. Additionally, the APCF exhibited lower charge transfer resistance compared to CF. This improvement is attributed to the evenly distributed carbon black within the coating and the highly hydrophilic nature of the amidoxime mediator, which together significantly enhanced the mass transfer of pollutants at the electrode surface and improved the performance38. LSV curves revealed that the APCF electrode displayed a distinct reduction peak at −0.32 V vs. Ag/AgCl in a solution containing Cu(II)-EDTA (Fig. 2b), indicative of the reduction of Cu(II) to Cu(0)39. In comparison, both CF and PCF showed no reduction peaks, indicating that only the amidoxime-functionalized APCF electrodes were capable of reducing Cu(II) in the saturated coordination complexes. Simultaneously, the APCF electrode can achieve the reduction of Pb(II) and Ni(II) from Pb(II)-EDTA and Ni(II)-EDTA at −1.00 V and −1.11 V, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5). The efficient reduction of these heavy metals from their organic complexes by the amidoxime-functionalized APCF electrode underscores its potential in the capture and recovery of heavy metals.

Heavy metal recovery performance of CMBER

To demonstrate that the spontaneous capture and recovery facilitated by the strong coordinating mediator, we employed electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring (EQCM-D, Biolin Scientific, Sweden). This technique was used in conjunction with an PAN-modified Au sensor (PAN-S) and an amidoxime mediator-functionalized PAN-S (APAN-S) to quantify the interaction involved in capturing Cu from Cu(II)-EDTA. Initially, both the PAN-S and the APAN-S were equilibrated by circulating 50 mM Na2SO4 electrolyte through the EQCM-D cell for 20 min. Following the introduction of 0.5 mM Cu(II)-EDTA into the system, the APAN-S electrode exhibited an increase in mass without any voltage being applied (Fig. 3a), whereas the PAN-S demonstrated negligible mass change. This disparity underscores the significant role of the amidoxime mediator’s strong coordination ability with Cu(II) in the capture process. When a potential of around −0.9 V vs. Ag/AgCl was applied, the mass of the APAN-S electrode continued to rise, demonstrating that the amidoxime mediator’s active sites were being regenerated through the reduction of captured Cu(II) over the course of the test. Meanwhile, the PAN-S recorded no significant change in mass. These findings conclusively show that Cu(II) in Cu(II)-EDTA complexes was initially captured by the amidoxime mediator (Fig. 3b), facilitated by the strong coordination bond between the amidoxime groups and Cu(II). This step was succeeded by the electrochemical reduction of the captured Cu(II) ions to their metallic (Cu(0)) state, alongside the regeneration of the amidoxime’s active sites.

a Mass change of the polyacrylonitrile -modified Au sensor (PAN-S) and an amidoxime mediator-functionalized polyacrylonitrile-S (APAN-S) from electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring (EQCM-D) test. b The proposed pathways for Cu(II) recovery from Cu-organic complex by amidoxime mediator in CMBER. c Effects of different voltages on Cu(II)-EDTA recovery. Experimental conditions: 0.5 mM Cu(II)-EDTA; 50 mM Na2SO4; a flux of 250 L m−2 h−1. d Comparison of Cu(II) recovery by and amidoxime mediator-functionalized polyacrylonitrile-modified carbon felt (APCF) electrode to those of carbon felt (CF) and polyacrylonitrile-modified carbon felt (PCF) electrodes at 3.0 V under a flux of 250 L m−2 h−1. e Digital photographs of pristine and used APCF electrode, and the corresponding magnified scanning electron microscope (SEM) and energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) images of used APCF electrode. Experimental conditions: 0.5 mM Cu(II)-EDTA; 50 mM Na2SO4; a flux of 250 L m−2 h−1; at 3 V for 8 h. f Ni(II) and Pb(II) recovery from Ni(II)-EDTA and Pb(II)-EDTA by APCF electrode at 4.2 V. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In the experiments for heavy metal recovery, wastewater first flowed through the APCF cathode, followed by the CF anode, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 6. Prior to voltage application during the test phase, the electrode was allowed to equilibrate for 5 min. We explored the effectiveness of the CMBER in capturing Cu(II)-EDTA at various voltages. At 0.0 V, there was no observable recovery of copper. As the voltage was increased to 2.0 V and 2.5 V, copper recovery improved to ~30% and 63.7%, respectively (Fig. 3c). A notable recovery rate of 97.6%, with the energy efficiency of 340.1 g kWh−1, was achieved at an applied voltage of 3.0 V (Supplementary Table 1). This superior performance is attributed to the lower cathodic potential (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7), which is more conducive to the reduction of captured Cu(II), thereby accelerating the regeneration of active sites of the amidoxime mediator and enhancing the capture efficiency of Cu(II)-EDTA in the CMBER. Interestingly, at 3.0 V, the concentration of EDTA in the solution remained largely unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 8), indicating that extracting copper from Cu(II)-EDTA complexes does not significantly alter the structure of EDTA. This finding distinctly differentiates our copper recovery mechanism through spontaneous capture and electro-reduction in the CMBER from other methods reported in the literature5,8,10,20,21,22,26,33,40,41,42, which involve breaking Cu(II)-EDTA complexes to release Cu(II). Throughout the operation, the CMBER system was found not to generate harmful components (Supplementary Fig. 9). However, further increasing the voltage to 4.0 V resulted in a reduced recovery rate of 93.9% (from 97.6% at 3.0 V) and a lower energy efficiency of 207.2 g kWh−1 (from 340.1 g kWh−1 at 3.0 V), suggesting that 3.0 V is the optimal voltage for this process, as evidenced by the results of EQCM-D test under different cathodic potentials (Supplementary Fig. 10).

The efficiency of the CMBER in recovering Cu(II) from Cu(II)-EDTA was assessed at different water fluxes. The findings indicated that copper recovery improved from 10.0% to 97.6% as the flux was reduced from 1000 L m−2 h−1 to 250 L m−2 h−1 (Supplementary Fig. 11). The compromised recovery efficiency at higher fluxes was attributed to the insufficient reaction time available for the amidoxime to effectively capture and recover copper from Cu(II)-EDTA. Decreasing the water flux further to 125 L m−2 h−1 did not notably enhance copper recovery, establishing 250 L m−2 h−1 as the optimal water flux for this process. Moreover, to elucidate the specific contribution of the amidoxime mediator in the APCF electrode, Cu(II) recovery experiments were also conducted using PCF and CF electrodes as controls. The recovery rates for Cu(II) with CF and PCF electrodes were substantially lower, at ~36% and 10%, respectively (Fig. 3d). The particularly low recovery observed with the PCF electrode was linked to the obstruction of CF’s active sites by the polyacrylonitrile coating. The hydrogen evolution potentials of CF and APCF electrode were −1.39 V vs. Ag/AgCl and −1.51 V vs. Ag/AgCl (Supplementary Fig. 12), respectively, indicating that the hydrogen evolution reaction is less pronounced in APCF electrode compared to CF electrode due to the presence of organic coatings. Therefore, the Faradaic efficiency of APCF electrodes for Cu(II) recovery (86.0%) is significantly higher than that of CF electrodes (32.1%) under the same operating conditions (Supplementary Table 2), enhancing overall energy efficiency. The APCF’s cathodic potential at the cell voltage of 3.0 V ( − 0.89 V vs. Ag/AgCl, Supplementary Fig. 7) was also below the hydrogen evolution potential (−1.51 V vs. Ag/AgCl), effectively minimizing the impact of cathodic hydrogen evolution on Cu(II) recovery. The presence of competing species (e.g., Fe(III), Ca(II), Mg(II), humics) had no significant impacts on the recovery of Cu(II) compared to the control (Supplementary Fig. 13). This insignificant effect of coexisting Ca(II) and Mg(II) on Cu(II) recovery is likely due to the lower stability of the complexes formed by Ca(II) and Mg(II) with amidoxime groups (Supplementary Table 3), while amidoxime groups preferentially form more stable complexes with Cu(II). In the electrochemical system, the reduction potential of Fe(III) to Fe(0) is −0.037 V vs. SHE43, which is significantly more positive than the cathodic potential of −0.693 V vs. SHE, allowing Fe(III) to be directly reduced without occupying the amidoxime groups. Additionally, negatively charged humics are repelled by the cathode and migrate toward the anode under the electric field.

The conversion of Cu(II) to Cu(0) was further examined through XRD and EDS analyses, with the CMBER system operated continuously at 3.0 V with a flux of 250 L m−2 h−1 for 24 h. Observations revealed a transition in color for the used APCF electrode from black to reddish-brown, indicative of copper’s presence (Fig. 3e). Enlarged SEM images and EDS data confirmed that the carbon nanofibers of the used APCF electrode were densely coated with copper, with minimal presence of other elements such as C and O, suggesting a high concentration of copper particles on the electrode. XRD analysis presented distinctive peaks at 43.3°, 50.4°, and 74.1° (Supplementary Fig. 14), correlating to the (1 1 1), (2 0 0), and (2 2 0) crystal planes of copper (Cu(0)), as per JCPDS No.04-083644. Additionally, peaks observed at 29.6°, 36.4°, 61.3°, and 73.5° were assigned to Cu2+1O (JCPDS No.05-0667)45, likely stemming from the oxidation of copper particles’ outer layers during extended operation and electrode drying. The Cu 2p3/2 XPS spectra identified two principal peaks with binding energies at 932.4 and 934.6 eV (Supplementary Fig. 15), corresponding to Cu and Cu-O46,47, respectively. Similar to Cu(II), the recovery rate of Ni(II) from Ni(II)-EDTA and Pb(II) from Pb(II)-EDTA using the APCF electrode at 4.2 V was 93.2% and 94.4%, respectively (Fig. 3f). A cell voltage of 4.2 V was applied to achieve efficient recovery of Pb(II) and Ni(II). At this voltage, the APCF’s cathodic potential is −1.45 V vs. Ag/AgCl, which is below the hydrogen evolution potential of the electrode (−1.51 V vs. Ag/AgCl). The difference minimizes the likelihood of hydrogen evolution reactions, maximizes heavy metal recovery efficiency and prevents the formation of inorganic scaling, thereby enhancing current utilization efficiency. The conversion of Ni(II) to Ni(0) and Pb(II) to Pb(0) was further confirmed by XRD analyses (Supplementary Fig. 16).

This comprehensive analysis unequivocally demonstrates the APCF electrodes’ capability to capture and recover Cu(II) from Cu(II)-EDTA. Unlike methods described in the literature, which necessitate the destruction of EDTA through the use of highly oxidizing agents like reactive oxygen species for copper recovery, our approach achieves spontaneous capture and reduction of Cu(II)-EDTA directly at an amidoxime-functionalized APCF electrode. By incorporating the amidoxime mediator into the cathode, we streamline the process for removal and recovery, laying the groundwork for next-generation environmental remediation techniques via the CMBER strategy.

Mechanisms of the spontaneous capture and reduction of CMBER

The process of Cu(II) capture from Cu(II)-EDTA by the amidoxime mediator was examined using the X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES), extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) and density functional theory (DFT) calculations (the atomic coordinates of configurations are shown in Supplementary Data 1). For XANES and EXAFS tests, the APAN material was introduced into a solution containing 0.5 mM Cu(II)-EDTA for 120 min (APAN-Cu(II)-EDTA) to analyze the coordination environment of Cu(II). As a control, the APAN material was directly added to a 0.5 mM CuSO4 solution for 120 min (APAN-CuSO4). In the EXAFS spectra, Cu in both samples exists mainly in the two coordination forms, Cu-N and Cu-O (Fig. 4a). The coordination numbers of Cu-O and Cu-N in APAN-Cu(II)-EDTA were found to be 2.1 ± 0.1 and 2.5 ± 0.1, respectively (Supplementary Table 4), closely resembling those in APAN-CuSO4. This indicates that the amidoxime mediator can spontaneously capture Cu(II) from Cu(II)-EDTA, with a coordination ratio of amidoxime mediator to Cu(II) of 2:1. The calculated binding energy for this ratio (2:1) of amidoxime mediator to Cu(II) was −47.8 eV (Fig. 4b), indicating a significantly stronger negative binding energy than that observed for Cu(II) with EDTA, which was −41.2 eV. Additionally, the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) associated with the Cu capture reaction was negative (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 17), implying that the amidoxime mediator is capable of spontaneously capturing Cu(II) from Cu(II)-EDTA. In contrast, a positive ΔG value (+30.8 eV) for the capture of Cu(II) from Cu(II)-EDTA by two cyanide groups present in the PCF electrode suggests that such a reaction is energetically unfavorable. This conclusion is supported by experimental observations detailed in Fig. 2a and Fig. 3d.

a Extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra of the used amidoxime mediator-functionalized polyacrylonitrile (APAN) material. The inset of panel a is the corresponding EXAFS data weighted by k3 χ(k). b Binding energy of Cu(II) with various organic ligands. c Recovery of Cu(II) from different Cu-organic complexes including Cu(II)-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Cu(II)-EDTA), Cu(II)-N-(2-hydroxyethyl)ethylenediamine-N,N’,N’-triacetic acid (Cu(II)-HEDTA), Cu(II)-nitrilotriacetic acid (Cu(II)-NTA), Cu(II)-ethylenediamine-N,N’-diacetic acid (Cu(II)-EDDA), Cu(II)-iminodiacetic acid (Cu(II)-IDA), and Cu(II)-glycine (Cu(II)-Gly) in CMBER. d Binding energy of Cu(II) in different Cu-organic complexes. Error bars represent the standard deviations (s.d.) (n = 3), and data are presented as mean values ± s.d for independent samples. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. The atomic coordinates of configurations are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

To further elucidate the effectiveness of the amidoxime mediator in recovering Cu(II) from a variety of Cu(II)-organic complexes, we conducted Cu(II) recovery experiments at 3.0 V with a water flux of 250 L m−2 h−1 using a variety of complexes, including Cu(II)-HEDTA, Cu(II)-NTA, Cu(II)-EDDA, Cu(II)-IDA, and Cu(II)-Gly. The recovery rates for Cu(II) from these complexes in the CMBER system were as follows: 97.6% for Cu(II)-EDTA, 98.3% for Cu(II)-HEDTA, 99.6% for both Cu(II)-NTA and Cu(II)-EDDA, 99.7% for Cu(II)-IDA, and 99.9% for Cu(II)-Gly (Fig. 4c). These recovery efficiencies closely matched the binding energies of the respective organic ligands with Cu(II), which were −41.2 eV for Cu(II)-EDTA, followed by −39.8 eV, −38.3 eV, −32.6 eV, −25.8 eV, and −24.5 eV for Cu(II)-HEDTA, Cu(II)-NTA, Cu(II)-EDDA, Cu(II)-IDA, and Cu(II)-Gly, respectively (Fig. 4d). The ΔG for the capture of Cu(II) by the amidoxime mediator from these complexes ranged from −6.6 to −23.3 eV (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 18). A more negative ΔG value is indicative of a higher spontaneity in the capture reaction. This correlation aligns well with the observed copper recovery rates in the CMBER. These findings highlight the role of strong coordinating mediator electro-reduction in facilitating the spontaneous capture and efficient recovery of Cu(II) from various Cu(II)-organic complexes, with the performance closely linked to the comparative coordination strengths of the Cu(II)-amidoxime mediator and the Cu(II)-organic complexes.

We further explored the spontaneous capture and recovery mechanisms of Cu(II) by the amidoxime mediator in the CMBER system using in situ Raman spectroscopy and electronic structure calculations (Fig. 5a). The Raman spectra at different reaction times all exhibited two broad peaks at ~426 cm−1 and 567 cm−1, attributed to Cu-N and Cu-O bonds, respectively (Fig. 5b)48,49. Initially, at a reaction time of 1 s, most amidoxime groups reacted with Cu(II)-EDTA, resulting in a Cu-O to Cu-N peak integrated area ratio of 1.76. This indicates that in Stage I, the -N-OH group from the amidoxime mediator displaces a carboxyl group in Cu(II)-EDTA (Cu-O/Cu-N = 2). With a coordination ratio of 2:1 between the amidoxime mediator and Cu(II), this substitution transitions Cu(II) from a six-coordinated state within Cu(II)-EDTA to a four-coordinated state. The ΔG for this reaction is −0.51 eV (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 19), suggesting the reaction’s spontaneous nature. As the reaction time increased to 2 s, the Cu-O to Cu-N peak integrated area ratio decreased to 0.48, suggesting that Stage II involves the replacement of two carboxyl groups in Cu(II)-EDTA by the -NH2 group from amidoxime, further reducing Cu(II) coordination to a two-coordinated state (ΔG = − 2.47 eV). At 4 s, the Cu-O to Cu-N peak integrated area ratio increased to 0.89, indicating that Stage III marks the complete capture of Cu(II) by the amidoxime mediator, with EDTA being released (ΔG = − 3.61 eV), thereby concluding the capture phase. Subsequently, in Stage IV, the captured Cu(II) is reduced to Cu(0) at the cathode, while the amidoxime mediator’s active sites regenerate simultaneously, preparing it for another cycle of Cu(II)-EDTA capture. To verify the regeneration, we immersed the APCF electrode in a Cu-EDTA solution and conducted an LSV test in 0.5 M Na2SO4, which displayed a Cu(II) reduction peak at −0.32 V. After completely reducing the captured Cu(II) to Cu(0), the electrode was re-immersed in the Cu-EDTA solution and subjected to another LSV test. The reappearance of the Cu(II) reduction peak confirmed that the amidoxime-based sites could be successfully regenerated (Supplementary Fig. 20).

a Schematic of the proposed pathways for spontaneous capture and in situ electro-reduction using the strong coordinating mediator. b In situ Raman spectra of amidoxime mediator with Cu(II)-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Cu(II)-EDTA) at different reaction times. c Energy barriers in different conformations during the spontaneous capture reaction of amidoxime mediator with Cu(II)-EDTA. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. The atomic coordinates of configurations are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Charge density difference analyses in Stage IV (Supplementary Fig. 21) indicate electron transfer from the -NH2 group in the amidoxime mediator to Cu(II), aiding in Cu(II)’s reduction. The distinct charge densities between Cu(II) and the amidoxime mediator facilitate this reduction process. Thus, although the amidoxime mediator-Cu(II) complex is structurally more stable than Cu(II)-EDTA, the Cu(II) captured in the amidoxime mediator is still more likely to gain electrons directly for reduction. During the reduction of Cu(II), the Cu-O bonds in the amidoxime mediator-Cu(II) complex are preferentially broken, followed by the Cu-N bonds (Supplementary Fig. 22 and Supplementary Fig. 23). Cu(II) continues to gain electrons through the -NH2 group until the reduction of Cu(II) is complete and the amidoxime mediator is fully regenerated. Notably, unlike the amidoxime mediator, the cyanide group does not provide a significant electron transfer route to Cu(II) (Supplementary Fig. 24), highlighting that cyanide coordination does not effectively contribute to Cu(II) reduction. Through DFT calculations, we have verified the intricate interactions between Cu(II) and the amidoxime mediator that underpin the mechanisms of Cu(II) capture and reduction.

Analysis of the CMBER’s applicability for Cu(II) recovery

The energy efficiency of Cu(II) recovery (measured as Cu(II) recovered per kWh of electrical energy) from 0.5 mM Cu(II)-EDTA utilizing the CMBER approach was determined to be 340.1 g kWh−1. This efficiency significantly surpasses (fivefold improvement) that of existing technologies reported in the literature, which include 16.89 g kWh−1 for decomplexing Cu(II)-EDTA to release Cu(II) and 14.99 g kWh−1 for Cu(II) recovery through self-enhanced electrochemical membrane filtration8; as well as 9.93 g kWh−1 for releasing Cu(II) from Cu(II)-EDTA via the electro-Fenton process and subsequent Cu(II) recovery through electrochemical reduction10 (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Table 5). Notably, the CMBER maintains ~80% Cu(II) recovery efficiency after around 130 h of operation (Fig. 6b), demonstrating both sustained performance and high energy efficiency with a remarkable Cu(II) recovery capacity of 941 kg-Cu m−2. The recovered copper consisted of agglomerated nanoparticle clusters (Supplementary Fig. 25). The regenerated APCF exhibited FT-IR spectra identical to those of the pristine electrode (Supplementary Fig. 26), indicating that the functional group structure of the amidoxime on the regenerated APCF electrode was maintained throughout the whole heavy metal recovery process (as shown in Fig. 1). The reduced Cu(0) can be separated from the electrode surface by applying a reverse cell voltage of 1.0 V for 15 s. After completing the Cu(0) separation operation, the APCF electrode can resume its high treatment efficiency with Cu(II)-EDTA (Supplementary Fig. 27).

a Comparison on recovery and energy efficiency of Cu(II) recovery from Cu(II)-organic complexes by different strategies. The size of the circle represents the Cu(II)-organic complexes concentration of the influent. Blue color: literature results; Red color: this study; Black color: symbols. The references for the data sources are included in Supplementary Table 5. b The capacity of CMBER for Cu(II) recovery during long-term test. c Recovery of Cu(II) from real Cu-containing chip manufacturing effluent water in batch mode. The GB 39731-2020 standard specifies the discharge limits for water pollutants in the Chinese electronics industry. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Additionally, the CMBER’s applicability was tested on actual Cu-containing wastewater from chip manufacturing processes (Supplementary Table 6), evaluating its potential for real-world application. Operating under conditions identical to those used for simulated wastewater, the concentration of Cu(II) in the effluent was reduced to 17.6 μg L−1 in an hour (Fig. 6c) with the influent concentration of 7.05 mg L−1. This result meets the Chinese electronic industry’s discharge standards for water pollutants (GB 39731-2020, which sets a limit of 0.5 mg L−1), underscoring the practical viability of employing strong coordinating mediator-based electro-reduction for the treatment of wastewater containing heavy metal-organic complexes.

We have developed a coordinating mediator-based electro-reduction strategy for the single-step recovery of heavy metals from wastewater containing heavy metal-organic complexes. This unique method leverages the -N-OH and -NH2 groups of amidoxime to spontaneously capture heavy metal ions from their complexes (e.g., Cu(II)-EDTA, Ni(II)-EDTA and Pb(II)-EDTA), without requiring external energy, followed by direct in situ electro-reduction to recover the metals. The transformation of captured Cu(II) into Cu(0) regenerates the active sites of amidoxime, facilitating the ongoing capture of Cu(II). At a voltage of 3 V and a water flux of 250 L m−2 h−1, our CMBER system has achieved a Cu(II) recovery efficiency of 97.6% and demonstrated an energy efficiency of 340.1 g kWh−1, which is nearly five times higher than existing technologies. The CMBER can also achieve ~95.0% recovery of Ni(II) from Ni(II)-EDTA and Pb(II) from Pb(II)-EDTA. The CMBER approach introduces a cost-effective avenue for resource recovery and water treatment.

Methods

Preparation of APCF electrodes

All chemicals (analytical reagent grade) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The method for fabricating APCF electrodes is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1. In summary, 2 g of polyacrylonitrile (PAN, average molecular weight = 150,000) and 1 g of Super P carbon black conductive agent (TIMCAL) were mixed and dispersed in 40 mL of dimethylformamide (DMF, Macklin), creating a homogeneous and viscous slurry. Pieces of commercial carbon felt (CF) (2 cm × 2 cm) were soaked in this slurry overnight to produce PAN-modified CF (PCF). These PCF electrodes were then dried at 80 °C for 2 h. To convert -C ≡ N groups to amidoxime for fabricating APCF electrodes, the PCF electrodes underwent further modification: they were submerged in 100 mL of water, which was heated to 70 °C. Once the temperature stabilized, 7.5 g of Na2CO3 (≥99.5%) and 10 g of hydroxylamine hydrochloride (NH2OH·HCl, 98%) were added sequentially to the mixture. The reaction35 was allowed to proceed for 3 h, followed by a thorough rinse with water. Finally, the APCF electrodes were dried at 80 °C for 2 h.

Electrochemical tests

The metal recovery experiments were performed using an electrochemical setup with a two-electrode system in a CMBER device, comprising an APCF cathode and a CF anode, with the APCF cathode positioned in front of the CF anode (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4). The electrode area, electrode spacing and chamber electrolyte volume of the CMBER device were 4 cm2 and 2 cm and 8 cm3, respectively. Before assembling the continuous-flow apparatus, both electrodes were immersed and allowed to equilibrate in a 50 mM Na2SO4 (≥99%) solution for 12 h. Control experiments employing CF and PCF as working electrodes were also conducted for comparison. During the electroreduction phase of Cu(II)-EDTA, a consistent cell voltage of 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 3.5 or 4.0 V was applied using an electrochemical workstation (Gamry Reference 600 + ). The treated effluent was discharged directly from the system without being recirculated back into the feed water. This direct discharge approach ensures that the effluent, once processed, is immediately removed from the system, preventing it from re-entering the treatment cycle. To elucidate the Cu(II) recovery mechanism, a variety of organic ligands known for their differential coordinating capacities with Cu(II) were tested, including N-(2-hydroxyethyl)ethylenediamine-N,N’,N’-triacetic acid (HEDTA, 98%), nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA, ≥99%), ethylenediamine-N,N’-diacetic acid (EDDA, ≥98%), iminodiacetic acid (IDA, ≥98%), and glycine (Gly, ≥99%).

The Electrochemical Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation Monitoring (EQCM-D, Biolin Scientific, Sweden) was employed to monitor mass changes on the gold sensor by observing shifts in the vibrational harmonics or overtones (fn) of piezoelectric quartz crystals. The EQCM-D electrochemical module included an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, a platinum (Pt) sheet counter electrode, and a quartz crystal sensor as the working electrode. The gold quartz-crystal sensor (Biolin Scientific, Sweden) was coated with a 25 mg L−1 PAN solution in DMF, achieving an electrochemically active surface area of 0.79 cm2 for the modified electrode. After a drying process at 60 °C for 3 h, the PAN-coated gold sensor (PAN-S) underwent further modification by immersion in a 30 mL solution containing 2 g of Na2CO3 and 3 g of NH2OH·HCl, followed by heating at 70 °C for 2 h. This procedure produced an amidoxime mediator-functionalized, PAN-modified gold sensor (APAN-S), which was then dried at 80 °C for 1 h. To establish stable baseline frequencies, a 50 mM Na2SO4 solution was circulated through the EQCM-D chamber. The electrolyte consisting of 0.5 mM EDTA-Cu (0.5 mM Cu(II) and 0.6 mM Na2EDTA) and 50 mM Na2SO4 was used during the capture and electro-reduction phases. Mass change (Δm, g) was determined from the observed frequency shift (Δf) using the following equation:

where Cf is the mass sensitivity constant (17.7 ng cm−1 Hz−1 for 5 MHz crystals), and n is the overtone number (1,3…n).

The metal recovery (R, %) and energy efficiency (E, g kWh−1) were calculated by the following equations (Eqs. 2 and 3):

where t (h) is the operation time, Ct (mM) is the concentration of metal ions at time t, C0 (mM) is the initial concentration of metal ions, M is the molecular weight of Cu, Q (L m−2 h−1) is the water flux of the solution, U (V) is the operating voltage, and I (A m−2) is the average current density.

Analytical methods

The electrode morphologies were examined using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, Zeiss Gemini 300), with the elemental composition of the electrodes assessed through an energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) attached to the FESEM. To further characterize the electrode materials, a suite of analytical techniques was employed: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR, Nexus 670), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo ESCALAB 250XI), and X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku Ultima IV). The electrochemical properties of the electrodes were analyzed using linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in a three-electrode setup, facilitated by an electrochemical workstation (Reference 600 + , Gamry). Copper ion concentrations were quantified through inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, Agilent 720ES) after acid digestion. The levels of EDTA and other organic ligands were determined using reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 1200)8,19. X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra were recorded in transmission mode with Si(111) crystal monochromators at the BL11B beamlines at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) (Shanghai, China). The in situ Raman spectra of amidoxime mediator-functionalized PAN were collected on a Deep Inspectra R Raman spectrometer with an in situ cell from 300 – 650 cm−1 in solution containing 0.5 mM Cu(II), 0.6 mM EDTA and 50 mM Na2SO4. The total organic carbon concentration was analyzed by a total organic carbon analyzer (TOC-L, SHIMADZU). High-resolution solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (SSNMR) spectra were acquired using a Bruker 400 M under the following conditions: a MAS spin rate of 10 Khz, a recovery time of 4 s, a pulse programmed cp for acquisition, and a pre-scan delay of 6.5 μs.

Density functional theory calculations

The molecular geometries were computed using density functional theory (DFT), employing the PBE0 density functional method complemented with the D3BJ dispersion correction50,51. For the purpose of geometry optimization and vibrational frequency analysis, the 6–31 + G(d) basis set was selected for carbon (C), hydrogen (H), nitrogen (N), and oxygen (O) atoms, while the Stuttgart/Dresden (SDD) pseudopotential was utilized for copper (Cu(0)). Following geometry optimization, the 6–311 + G(d,p) basis set was applied for single-point energy calculations to enhance precision. The DFT-D3 with BJ-damping was applied to correct the weak interaction to improve the calculation accuracy. The SMD implicit solvation model52 was used to simulate the solvation effect of water, ensuring a more realistic environmental context for the reactions. These comprehensive computational analyses were conducted using the Gaussian 16 software suite53. The binding energy (Eb) was determined according to the following equation:

where EAB is the energy of complex, and EA and EB represent the energies of isolated structure. Charge density difference (isosurface = 0.015) between Cu(II) and amidoxime (or cyanide) group was performed with the Multiwfn software (version 3.8)54 and the VMD package (version 1.9.3)55.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of the study are included in the main text and supplementary information files. The atomic coordinates of configurations used in this study are provided in Supplementary Data 1. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Bolisetty, S., Peydayesh, M. & Mezzenga, R. Sustainable technologies for water purification from heavy metals: review and analysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 463–487 (2019).

Awual, M. E. et al. Ligand imprinted composite adsorbent for effective Ni(II) ion monitoring and removal from contaminated water. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 131, 585–592 (2024).

Hasan, M. M. et al. Facial conjugate adsorbent for sustainable Pb(II) ion monitoring and removal from contaminated water. Colloids Surf., A 673, 131794 (2023).

Awual, M. R. Novel conjugated hybrid material for efficient lead(II) capturing from contaminated wastewater. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C. 101, 686–695 (2019).

Wu, L. et al. Electrochemical removal of metal–organic complexes in metal plating wastewater: a comparative study of Cu-EDTA and Ni-EDTA removal mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 12476–12488 (2023).

He, S. et al. Highly effective photocatalytic decomplexation of Cu-EDTA by MIL-53(Fe): Highlight the important roles of Fe. Chem. Eng. J. 424, 130515 (2021).

Ye, Y. et al. Water decontamination from Cr(III)–organic complexes based on pyrite/H2O2: performance, mechanism, and validation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 10657–10664 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Self-enhanced decomplexation of Cu-organic complexes and Cu recovery from wastewaters using an electrochemical membrane filtration system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 655–664 (2021).

Guan, W., Zhang, B., Tian, S. & Zhao, X. The synergism between electro-fenton and electrocoagulation process to remove Cu-EDTA. Appl. Catal., B 227, 252–257 (2018).

Li, M. et al. An electrochemical strategy for simultaneous heavy metal complexes wastewater treatment and resource recovery. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 10945–10953 (2022).

Efome, J. E., Rana, D., Matsuura, T. & Lan, C. Q. Experiment and modeling for flux and permeate concentration of heavy metal ion in adsorptive membrane filtration using a metal-organic framework incorporated nanofibrous membrane. Chem. Eng. J. 352, 737–744 (2018).

Ling, L.-L., Liu, W.-J., Zhang, S. & Jiang, H. Magnesium oxide embedded nitrogen self-doped biochar composites: fast and high-efficiency adsorption of heavy metals in an aqueous solution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 10081–10089 (2017).

Wang, T. et al. A green strategy for simultaneous Cu(II)-EDTA decomplexation and Cu precipitation from water by bicarbonate-activated hydrogen peroxide/chemical precipitation. Chem. Eng. J. 370, 1298–1309 (2019).

Sun, J.-M., Shang, C. & Huang, J.-C. Co-removal of hexavalent chromium through copper precipitation in synthetic wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 4281–4287 (2003).

Kubra, K. T. et al. Utilizing an alternative composite material for effective copper(II) ion capturing from wastewater. J. Mol. Liq. 336, 116325 (2021).

Awual, M. R. et al. Inorganic-organic based novel nano-conjugate material for effective cobalt(II) ions capturing from wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 324, 130–139 (2017).

Zu, D. et al. Understanding the self-catalyzed decomplexation mechanism of Cu-EDTA in Ti3C2Tx MXene/peroxymonosulfate process. Appl. Catal., B 306, 121131 (2022).

Fu, F., Xie, L., Tang, B., Wang, Q. & Jiang, S. Application of a novel strategy—advanced fenton-chemical precipitation to the treatment of strong stability chelated heavy metal containing wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 189-190, 283–287 (2012).

Huang, X. et al. Coupled Cu(II)-EDTA degradation and Cu(II) removal from acidic wastewater by ozonation: Performance, products and pathways. Chem. Eng. J. 299, 23–29 (2016).

Chen, Y. et al. Targeted decomplexation of metal complexes for efficient metal recovery by ozone/percarbonate. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 5034–5045 (2023).

Huang, X. et al. Autocatalytic decomplexation of Cu(II)–EDTA and simultaneous removal of aqueous Cu(II) by UV/chlorine. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 2036–2044 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Photoelectrocatalytic oxidation of metal-EDTA and recovery of metals by electrodeposition with a rotating cathode. Chem. Eng. J. 324, 74–82 (2017).

Zeng, H. et al. Enhanced photoelectrocatalytic decomplexation of Cu–EDTA and Cu recovery by persulfate activated by UV and cathodic reduction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 6459–6466 (2016).

Durante, C., Cuscov, M., Isse, A. A., Sandonà, G. & Gennaro, A. Advanced oxidation processes coupled with electrocoagulation for the exhaustive abatement of Cr-EDTA. Water Res. 45, 2122–2130 (2011).

Pan, M. et al. Multifunctional piezoelectric heterostructure of BaTiO3@graphene: decomplexation of Cu-EDTA and recovery of Cu. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 8342–8351 (2019).

Wang, T. et al. Novel Cu(II)–EDTA decomplexation by discharge plasma oxidation and coupled Cu removal by alkaline precipitation: underneath mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 7884–7891 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Self-catalytic Fenton-like reactions stimulated synergistic Cu-EDTA decomplexation and Cu recovery by glow plasma electrolysis. Chem. Eng. J. 433, 134601 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Enhancing Cu-EDTA decomplexation in a discharge plasma system coupled with nanospace confined iron oxide: insights into electron transfer and high-valent iron species. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. Energy 345, 123717 (2024).

Eivazihollagh, A., Bäckström, J., Norgren, M. & Edlund, H. Electrochemical recovery of copper complexed by DTPA and C12-DTPA from aqueous solution using a membrane cell. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 93, 1421–1431 (2018).

Juang, R.-S. & Lin, L.-C. Treatment of complexed copper(II) solutions with electrochemical membrane processes. Water Res. 34, 43–50 (2000).

Hu, X. et al. Electrocatalytic decomplexation of Cu-EDTA and simultaneous recovery of Cu with Ni/GO-PAC particle electrode. Chem. Eng. J. 428, 131468 (2022).

Xu, Z., Gao, G., Pan, B., Zhang, W. & Lv, L. A new combined process for efficient removal of Cu(II) organic complexes from wastewater: Fe(III) displacement/UV degradation/alkaline precipitation. Water Res. 87, 378–384 (2015).

Xu, Z., Shan, C., Xie, B., Liu, Y. & Pan, B. Decomplexation of Cu(II)-EDTA by UV/persulfate and UV/H2O2: efficiency and mechanism. Appl. Catal., B 200, 439–447 (2017).

Yang, L. et al. Electrochemical recovery and high value-added reutilization of heavy metal ions from wastewater: recent advances and future trends. Environ. Int. 152, 106512 (2021).

Wu, T. et al. Amidoxime-functionalized macroporous carbon self-refreshed electrode materials for rapid and high-capacity removal of heavy metal from water. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 719–726 (2019).

Weaver, J. B., Kozuch, J., Kirsh, J. M. & Boxer, S. G. Nitrile infrared intensities characterize electric fields and hydrogen bonding in protic, aprotic, and protein environments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 7562–7567 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Induced dipole moments in amorphous ZnCdS catalysts facilitate photocatalytic H2 evolution. Nat. Commun. 15, 2600 (2024).

Kim, J. et al. 10 mAh cm−2 cathode by roll-to-roll process for low cost and high energy density Li-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2303455 (2024).

Goss, D. J. & Petrucci, R. H. General Chemistry Principles & Modern Applications, Petrucci, Harwood, Herring, Madura: Study Guide. https://open.umn.edu (2007).

Zhao, X., Guo, L., Zhang, B., Liu, H. & Qu, J. Photoelectrocatalytic oxidation of Cu(II)–EDTA at the TiO2 electrode and simultaneous recovery of Cu(II) by electrodeposition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 4480–4488 (2013).

Zhao, X., Guo, L. & Qu, J. Photoelectrocatalytic oxidation of Cu-EDTA complex and electrodeposition recovery of Cu in a continuous tubular photoelectrochemical reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 239, 53–59 (2014).

Chen, C. et al. Enhanced ozonation of Cu(II)-organic complexes and simultaneous recovery of aqueous Cu(II) by cathodic reduction. J. Clean. Prod. 298, 126837 (2021).

Milazzo, G., Caroli, S. & Braun, R. D. Tables of standard electrode potentials. J. Electrochem. Soc. 125, 261C (1978).

Jiang, X. et al. Integrating hydrogen utilization in CO2 electrolysis with reduced energy loss. Nat. Commun. 15, 1427 (2024).

Li, J.-R. et al. In-situ synthesis of Cu/Cu2+1O/carbon spheres for the electrochemical sensing of glucose in serum. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 50, 24–31 (2022).

Liu, F. et al. Enhanced removal of EDTA-chelated Cu(II) by polymeric anion-exchanger supported nanoscale zero-valent iron. J. Hazard. Mater. 321, 290–298 (2017).

Devaraj, M., Deivasigamani, R. K. & Jeyadevan, S. Enhancement of the electrochemical behavior of CuO nanoleaves on MWCNTs/GC composite film modified electrode for determination of norfloxacin. Colloids Surf., B 102, 554–561 (2013).

Hong, N. T. & Dat, B. T. Dinuclear complexes of copper and silver with quinine. Vietnam J. Chem. 45, 255 (2014).

Albada, H. B., Soulimani, F., Weckhuysen, B. M. & Liskamp, R. M. J. Scaffolded amino acids as a close structural mimic of type-3 copper binding sites. Chem. Commun. 14, 4895-4897, (2007).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Marenich, A. V., Cramer, C. J. & Truhlar, D. G. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 6378–6396 (2009).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16 Rev. A.03. https://gaussian.com/relnotes_a03/ (2016).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996).

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 51925806) awarded to Z.W., the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 52100057) awarded to F.G., and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 52200107) awarded to L.M. for the financial support of the work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.S. and Z.W. conceived the idea and designed the research. W.S., J.L., F.G. and L.M. performed the experiment including electrode preparation, characterization, performance test and DFT calculation. X.S. provided constructive suggestions for the results and discussion. W.S., X.S. and Z.W. contributed to writing the manuscript. All coauthors discussed the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Md. Munjur Hasan and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, W., Li, J., Gao, F. et al. Strongly coordinating mediator enables single-step resource recovery from heavy metal-organic complexes in wastewater. Nat Commun 15, 10828 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55174-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55174-1