Abstract

Bacteria of clinical importance, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, can become hypermutators upon loss of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) and are clinically correlated with high rates of multidrug resistance (MDR). Here, we demonstrate that hypermutated MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa has a unique mutational signature and rapidly acquires MDR upon repeated exposure to first-line or last-resort antibiotics. MDR acquisition was irrespective of drug class and instead arose through common resistance mechanisms shared between the initial and secondary drugs. Rational combinations of drugs having distinct resistance mechanisms prevented MDR acquisition in hypermutated MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa. Mutational signature analysis of P. aeruginosa across different human disease contexts identified appreciable quantities of MMR-deficient clinical isolates that were already MDR or prone to future MDR acquisition. Mutational signature analysis of patient samples is a promising diagnostic tool that may predict MDR and guide precision-based medical care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

DNA mismatch repair (MMR)-deficiency drives hypermutation, or abnormally elevated mutation rates, and produces a consistent pattern of mutations across domains of life1,2,3,4. This pattern is defined by enriched C > T and T > C transition mutations and frameshifts caused by insertions or deletions (indels) in homopolymers5,6,7,8. Determination of the trinucleotide context, which considers the bases preceding and following the mutated base, allows for the identification of more precise mutational signatures. Several dozen distinct single base substitution (SBS) patterns have been computationally extracted from large datasets of human tumor genomes by measuring the relative abundance of each of the 96 possible trinucleotide mutation possibilities9,10. Five such mutational signatures (SBS6, SBS15, SBS21, SBS26, SBS44) in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) are associated with MMR deficiency in human tumors. Recently, de novo signature extraction was performed from large bacterial genomic datasets, and signatures were associated with MMR deficiency in some bacterial species, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa11.

MMR-deficient bacteria, predominately characterized by inactivation of mutS or mutL, are of great clinical importance due to their association with multidrug resistance (MDR). This link between MMR deficiency and MDR has been documented primarily in P. aeruginosa isolated from chronic respiratory infections in patients with bronchiectasis, including individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF), a fatal, autosomal recessive disorder that affects over 100,000 people globally12,13,14,15. MMR deficiency is observed in up to 60% of isolates of P. aeruginosa from people with CF (pwCF)16,17, and statistical analyses of sequenced longitudinal isolates of P. aeruginosa collected from pwCF have suggested MMR deficiency as the driver of MDR acquisition within the host18. MMR deficiency and MDR have also been observed in non-CF infection contexts19,20,21,22, and its prevalence remains an important unanswered question. In vitro, MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa acquires resistance to a single antibiotic treatment faster than wild-type (WT)21,23,24,25,26,27,28. Exactly how MMR deficiency drives MDR acquisition and the role of antibiotic treatment in this process are not fully understood.

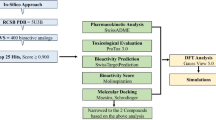

In this work, we aimed to study how MMR deficiency drives MDR and to address the links between the MMR deficiency-associated mutational signature and MDR. We performed in vitro adaptive evolution of MMR-deficient lab strains of P. aeruginosa by exposure to different antibiotics followed by whole genome sequencing (WGS) to characterize the mutational signature acquired in the absence of MMR. We then tested the evolved MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa for the acquisition of cross-resistance to drugs of different classes. Using WGS data from evolved lineages, we identified putative drug resistance mechanisms which we subsequently confirmed using structural analyses.

We then used this same approach to investigate a set of prospectively collected P. aeruginosa clinical isolates from pwCF and found that mutational signature analysis successfully predicted MMR status and future MDR acquisition in patient samples. Finally, we further validated the predictive ability of mutational signature analysis using two large publicly available P. aeruginosa isolate collections from pwCF and three separate disease contexts to illuminate the broad potential contribution of MMR deficiency in infections outside of CF.

Results

MMR deficiency is characterized by a hallmark mutational signature and drives rapid drug resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Previous work has shown MMR deficiency enhances antibiotic resistance acquisition in P. aeruginosa in vitro and is characterized by enriched genomic transition and insertion and deletion (indel) frameshift mutations6,21,23. We initially sought to characterize the full trinucleotide mutational signature that develops in MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa laboratory strains following antibiotic resistance acquisition. To do this, we performed in vitro adaptive evolution of WT and mutS-deficient P. aeruginosa insertional transposon knockout strain MPAO1-mutSTn (referred to as mutS- throughout)29,30 by exposure to drugs of differing classes: aztreonam (AZ, monobactam, cell wall synthesis); colistin (COL or polymyxin E, antimicrobial peptide, cell membrane stability); chloramphenicol (Chl, 50S ribosomal subunit and protein synthesis); investigational drugs D-CONGA and D-CONGA-Q7 (antimicrobial peptides, cell membrane stability)31,32,33,34. AZ and COL are clinically relevant treatments for P. aeruginosa infections used as a ‘first-line’ or ‘last-resort’ option, respectively35,36. D-CONGA and D-CONGA-Q7 are cationic antimicrobial peptides developed via synthetic molecular evolution and are efficacious in vitro and in vivo against drug-resistant clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and P. aeruginosa, including P. aeruginosa CF isolates37. Notably, induction of resistance to D-CONGA and D-CONGA-Q7 has not been observed for WT P. aeruginosa (PAO1)37,38. Prior to experimentation, mutS- was validated as a hypermutator (308-fold increase vs. MPAO1) via rifampicin reversion frequency (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Strains were confirmed as susceptible to all compounds via microbroth dilution defined by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpoints, except for chloramphenicol due to anticipated intrinsic resistance (Supplementary Fig. 1b)39,40.

MMR-deficient and WT lab strains were evolved in vitro by repeated exposure to respective treatments using a modified microbroth dilution approach. After each exposure, the population growing at the highest concentration of the drug was grown without treatment to expand the population and then treated again. Upon the emergence of drug resistance (defined by CLSI clinical breakpoints) and at the experimental endpoint (passage 10), evolved bacterial clones were subject to WGS and de novo mutation identification. For clarity, we define a ‘lineage’ as an independently evolved biological replicate including all sampling timepoints, and a ‘clone’ as a specific timepoint from a lineage. Higher mutation rates (Fig. 1a) and enriched transitions (Supplementary Fig. 1c) were observed in mutS- clones compared to MPAO1, consistent with MMR deficiency. To investigate the mutational signature associated with MMR deficiency, we assessed the trinucleotide SBS spectra of de novo mutations in all evolved clones. No significant shift in mutation spectra was observed due to antibiotic treatment (Supplementary Fig. 1d). In any single clone analyzed, there were insufficient numbers of mutations to generate robust mutational signatures given the full 96 possible trinucleotide sequence contexts. To address this, we combined all observed mutations from each individual mutS- clone into a single composite spectrum serving as the de facto mutational signature from MMR deficiency in P. aeruginosa (Fig. 1b). This signature is dominated almost exclusively by both C > T and T > C transitions, in agreement with a previous report11. The C > T transitions were enriched in NCC and NCG contexts, with a slight 5′ preference for C and G, and notably diminished in NCT contexts. The T > C transitions were enriched in CTN and GTN contexts, particularly in GT(G or C) contexts. Indel mutations are also increased significantly in homopolymers (Supplementary Fig. 1c), consistent with MMR deficiency5,6.

a Identification of unique SNVs following WGS showed exponentially higher mutation rates in MPAO1-mutSTn (mutS-) evolved lineages compared to MPAO1. b Trinucleotide mutational signature associated with MMR deficiency in P. aeruginosa, comprised of 661 unique SNVs identified from 27 independent biological replicates of mutS-. c Comparison of the P. aeruginosa MMR deficiency mutational signature (mutS-) to the composite human (HumanΔMMR) and all 5 individual SBS signatures using cosine similarity analysis. d Comparison of observed C > T and T > C transitions in all trinucleotide contexts from all mutS- isolates to C > T and T > C transition proportions in the HumanΔMMR mutation signature. e, f In vitro adaptive evolution of mutS- with repeated exposure to e antibiotic drug treatment (aztreonam, AZ), or f peptide drug treatment (colistin, COL; D-CONGA; or D-CONGA-Q7), resulted in significantly faster resistance acquisition than wild-type MPAO1. a shows biological replicates of n = 27 (mutS−) and n = 5 (WT) compared via unpaired t test. e, f are shown as mean ± SD of independent biological triplicates. Two-tailed P values are shown, **p = 0.0061, ****p < 0.0001, unpaired t tests of slopes from linear regression analysis of log-transformed datasets for comparison of treatment + mutS− vs WT.

Mutation spectra from hypermutated MMR-deficient human tumors have similar enrichments in transition mutations and so represent a large dataset for comparison to our P. aeruginosa mutS- signature. We found that the P. aeruginosa mutS- mutational signature has slight cosine similarity to human SBS6 and SBS15 (Fig. 1c). We also created a composite human MMR-deficient tumor signature (HumanΔMMR) by combining all individual signatures associated with MMR defects: SBS6, SBS15, SBS21, SBS26, and SBS44 (Supplementary Fig. 1e). The P. aeruginosa mutS- signature is more similar to this HumanΔMMR signature (Fig. 1c) with C > T at GCN and NCG being somewhat preferred (Fig. 1d). There are also several key differences, including a slight increase in overall T > C in P. aeruginosa while also having relatively fewer overall GTA > GCA. Along with the dissimilarities to SBS21 and 26 (Fig. 1c), which are dominated by T > C mutations, these unique features highlight the importance of mutational signature characterization across species.

We next sought to determine how the characterized MMR deficiency-associated mutational signature in P. aeruginosa is linked to rapid drug resistance acquisition. During the adaptive evolution of mutS- clones, we observed rapid acquisition of resistance to both AZ (Fig. 1e) and COL (Fig. 1f), with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) well above clinical breakpoints designated by the CLSI. An MMR-deficient strain of a different genotype, MPAO1-mutLTn, also exhibited rapid resistance acquisition, supporting MMR deficiency as the driver (Supplementary Fig. 1f and g). MMR-proficient MPAO1 eventually displayed elevated MICs to both AZ and COL, but it did so more slowly indicating that MMR deficiency catalyzed resistance acquisition. Despite lack of resistance acquisition previously observed in PAO137,38, mutS- rapidly developed resistance to both D-CONGA and D-CONGA-Q7 (Fig. 1f). These results indicate that MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa possesses a hallmark mutational signature that is linked to accelerated emergence of drug resistance under experimental in vitro conditions.

Treatment of MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa induces MDR through shared mechanisms of resistance

There is a strong association between hypermutation and MDR in P. aeruginosa clinical isolates, including documentation of hypermutator infections rapidly acquiring new cross-resistance to drugs never used as treatments21, but the mechanism of how MMR deficiency drives MDR acquisition is not fully understood. To examine this, we assessed MICs of the evolved mutS- and MPAO1 clones (Fig. 1) against a panel of five antibiotics from three different classes for cross-resistance acquisition: aztreonam (AZ, monobactam, cell wall synthesis); ciprofloxacin (fluoroquinolone, DNA gyrase); D-CONGA, D-CONGA-Q7, and polymyxin b (antimicrobial peptides, cell membrane stability). A summary of MIC values is presented in Supplementary Table 1. Treatment of mutS- with the antibiotics AZ or Chl induced cross-resistance to antibiotics in a different class such as ciprofloxacin (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a, pink lines), whereas no cross-resistance developed in antibiotic-treated WT MPAO1 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a, gray lines). Similarly, treatment of mutS-, but not WT MPAO1 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2b, gray lines), with COL, D-CONGA, or D-CONGA-Q7 induced cross-resistance to other peptides (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2b, blue lines). However, exposure to COL, D-CONGA, or D-CONGA-Q7 failed to induce marked cross-resistance to antibiotics (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a, blue lines) and treatment with antibiotic compounds resulted in no change in peptide MICs (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2c, pink lines). In vitro adaptive evolution of mutL- produced similar treatment-induced cross-resistance to that seen with mutS- (Supplementary Fig. 2d, pink lines), suggesting rapid cross-resistance acquisition is characteristic of, and dependent on, MMR deficiency. These mutually exclusive trends in cross-resistance acquisition suggest that treatment of MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa drives MDR in a highly selective manner but is not determined by common class or cell target.

a Representative cross-resistance acquisition to antibiotic compounds. Repeated exposure of mutS- to antibiotic drugs (aztreonam, AZ; chloramphenicol, Chl) drove rapid acquisition of resistance to ciprofloxacin (pink lines), but exposure to peptides (colistin, COL; D-CONGA; D-CONGA-Q7) did not (blue lines). MPAO1-WT cells were unaffected by exposure to any treatment (gray lines). Black dashed line represents the clinical breakpoint designated by CLSI. b Representative cross-resistance acquisition to peptides. In vitro adaptive evolution of mutS- with repeated exposure to peptide drugs (COL, D-CONGA, D-CONGA-Q7) rapidly acquired resistance to the peptide drugs D-CONGA (top, blue lines) and D-CONGA-Q7 (bottom, blue lines), while mutS- exposed to antibiotic drugs did not (top and bottom, pink lines). c MALDI-MS structural analysis of lipid A isolated from three independent mutS- lineages evolved in D-CONGA-Q7 (left) or D-CONGA (right) revealed functional membrane changes driving peptide resistance. d WGS followed by de novo mutation identification showed parallel enrichment of nonsynonymous mutations in efflux pumps for AZ- and Chl-treated lineages and in membrane-modifying genes for D-CONGA and D-CONGA-Q7 peptide-treated lineages. A and B are shown as mean ± SD of independent biological triplicates. *p = 0.0121, ***p = 0.0008, and ****p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA of slopes from linear regression analysis of log-transformed datasets for comparison of treatment + mutS− vs no treatment + mutS− vs treatment + WT. In all graphs, pink denotes drugs that are substrates of efflux pumps and blue denotes peptides. WT MPAO1 is shown in gray.

We speculated that, instead of being driven by shared class or cell target, MDR acquisition was driven by common selective pressures determining common mechanisms of resistance between the drug of exposure and drugs of cross-resistance. Thus, repeated exposure to MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa could be selected for mutations conferring resistance to AZ but simultaneously also conferring resistance to ciprofloxacin. To test this, we evaluated potential mechanisms of cross-resistance by examining all nonsynonymous de novo mutations in emergent resistant clones. Antibiotic-treated clones were enriched in mutations in nalC, nalD, and mexT, transcriptional repressors that regulate mex drug efflux operons, along with mexE, mexD, mexF, and mexI, genes in mex efflux operons (Supplementary Data 1). Drug efflux pumps are well-characterized transmembrane transport systems in P. aeruginosa, and other bacteria that mediate MDR41,42, and nonsynonymous mutations in such genes are widely reported in MDR CF isolates43,44. Clones treated with peptide drugs instead shared nonsynonymous mutations in pmrB and opr86, including PmrB-G188S (Supplementary Data 1) that has previously been shown to confer COL resistance43. Both genes are associated with outer membrane modifications44,45,46,47,48,49 indicating possible parallel evolution.

To validate membrane modifications as the mechanism of resistance to peptides D-CONGA and D-CONGA-Q7, we purified lipid A from D-CONGA- and D-CONGA-Q7-treated clones and performed matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS). D-CONGA-treatment selected against the presence of penta-acylated lipid A (m/z 1446) and secondary palmitoyl-modified lipid A (m/z 1684) (Fig. 2c, left), suggesting downregulation of PagL and PagP promotes D-CONGA resistance45,50. D-CONGA-Q7-treated clones predominately showed the presence of penta-acylated lipid A (m/z 1446) and secondary palmitoyl-modified lipid A (m/z 1684) (Fig. 2c, right), suggesting upregulation of PagL and PagP promote D-CONGA-Q7 resistance. Two D-CONGA-Q7-treated clones showed 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose (Ara4N) incorporation (m/z 1815) (Fig. 2c, right), which likely explains observed polymyxin b cross-resistance47 These spectra show marked differences in selection for lipid A structure following treatment of MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa with D-CONGA or D-CONGA-Q7, and support membrane modifications as the mechanism of resistance for peptides.

Notably, no mutations in mex drug efflux operons were found in peptide-treated clones, and no mutations in membrane modification genes were found in antibiotic-treated clones (Fig. 2d). Our data thus far suggest that treatment of MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa drives cross-resistance through shared mechanisms of resistance driven by the selective pressures imposed by initial treatment. Within the scope of this work and tested drugs, treatment with antibiotics was selected for mutations in efflux pumps, whereas treatment with peptides was selected for mutations in membrane modification genes in a mutually exclusive manner.

Rational combination therapy of MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa prevents resistance acquisition

Based on this mutual exclusivity of resistance mutations to antibiotics and peptides, we reasoned that combining treatments requiring distinct resistance mechanisms could significantly slow or possibly even prevent MDR in MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa. Our data thus far and prior literature51,52,53,54,55 suggest this can be accomplished by combining an antibiotic and a peptide drug. To test this approach, we evolved mutS- in antibiotic + peptide combinations (AZ + COL, AZ + D-CONGA, and AZ + D-CONGA-Q7) and measured resistance acquisition after repeated combination treatment compared to monotherapy. All antibiotic + peptide combination treatments significantly reduced resistance acquisition compared to monotherapies (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. a and b, compare purple lines to pink and blue lines). In vitro adaptive evolution of mutL- in AZ + COL also prevented resistance acquisition (Supplementary Fig. 3c, purple lines), suggesting that the efficacy of combination therapy is not dependent on the specific genotype responsible for MMR deficiency. Antibiotic + peptide combination treatments showed no significant effect on resistance acquisition in WT MPAO1 (Supplementary Fig. 3d–f). WGS of midpoint and endpoint clones showed that combination therapy had no effect on mutation rate (Supplementary Fig. 4a) or mutation spectra (Supplementary Fig. 4b, c), indicating combination therapy was effective despite continued mutagenesis from MMR deficiency. These results suggest that rationally combining drugs that impose competing selective pressures (i.e. require distinct and exclusive mechanisms of resistance) effectively prevent drug resistance acquisition of MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa in vitro.

a In vitro adaptive evolution of mutS- with repeated exposure to combination aztreonam + colistin (AZ + COL) results in minimal resistance acquisition (purple line). b In vitro adaptive evolution of mutS- treated with tobramycin + colistin (TOB + COL) does not prevent resistance acquisition. c mutS- acquisition of resistance to polymyxin B (blue lines), which was previously shown to be induced by COL and D-CONGA-Q7 treatment, was not observed with evolution with repeated exposure to combination therapy (purple lines). d mutS- acquisition of resistance to ciprofloxacin, which was induced by AZ treatment (pink lines), was not observed with evolution with repeated exposure to combination therapy (purple lines). e In vitro adaptive evolution of mutS- treated with a common treatment regimen used in human patients with CF infected with P. aeruginosa, aztreonam cycled with tobramycin (AZ/TOB). f, g Comparison of resistance acquisition to TOB between f mutS- or g MPAO1 previously passaged 10 times in AZ and mutS-/MPAO1 with no prior evolution. All data are shown as mean ± SD of independent biological triplicates. ****p < 0.0001, ordinary one-way ANOVA of slopes (a), ordinary one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons (c, d), or unpaired t test (two-tailed) (e) from linear regression analysis of log-transformed datasets. for comparison of combination therapy + mutS- vs monotherapy + mutS- (a, c, d) or treatment + mutS- vs WT (e).

Aminoglycosides are substrates of efflux pumps41 but share a mechanism of resistance with peptides through membrane modifications56. Due to this, the antibiotic + peptide model may be an oversimplification. To test this, we evolved MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa in tobramycin (TOB), COL, and TOB + COL. Treatment with TOB + COL resulted in resistance acquisition similar to both monotherapies (Fig. 3b). We performed WGS on all endpoint clones and observed mutations in pmrB and cti, both contributing to alterations of membrane fluidity or charge that have been linked to resistance to both colistin and aminoglycosides. From this, drugs in combination must have distinct mechanisms of resistance to be effective against MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa.

We next sought to determine if antibiotic + peptide combination treatment could eliminate the previously observed single treatment-induced MDR acquisition in MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa. To do so, we evaluated the combination-treated evolved clones against the same panel of single antibiotics to evaluate potential cross-resistance acquisition. Antibiotic + peptide combination therapy treatment of mutS- effectively eliminated the cross-resistance to polymyxin B (Fig. 3c, purple lines), D-CONGA (Supplementary Fig. 4d, purple lines), and D-CONGA-Q7 (Supplementary Fig. 4e, purple lines) that we previously observed with peptide monotherapy. Combination treatment of mutS- also eliminated cross-resistance acquisition to ciprofloxacin, previously observed with antibiotic monotherapies (Fig. 3d, purple lines). Combination-treated clones showed minimal elevation in MICs against relevant monotherapies (Supplementary Fig. 4f-h). Our data suggest that rationally combining therapies requiring exclusive mechanisms of resistance prevents MDR acquisition in MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa.

A common treatment approach for pwCF chronically infected with P. aeruginosa is cycled continuous inhaled antibiotic therapy, such as AZ cycled with TOB35,36,57,58. However, our results suggest this approach would be ineffective at preventing resistance acquisition in MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa, since AZ and TOB can both be effluxed effectively to confer resistance. To model this in vitro, we treated mutS- with AZ and then evolved the AZ-adapted clones in TOB and determined resistance acquisition. AZ cycled with TOB induced significant resistance in mutS- (Fig. 3e, pink line). MPAO1 also acquired resistance to AZ cycled with TOB, albeit at a much slower rate and magnitude (Fig. 3e, black line). We next compared the resistance to TOB of strains previously evolved in AZ (Fig. 3e, passage 11-20) to that of naïve strains with no prior drug exposure. After 10 passages in AZ, evolved MMR-deficient clones were significantly more resistant to TOB than naïve clones, with MICs above the clinical breakpoint (Fig. 3f). WT clones previously evolved in AZ similarly displayed MICs higher than naïve clones (Fig. 3g). These results suggest that this common treatment approach in humans can drive rapid resistance acquisition in MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa in culture. Additionally, they suggest this common approach could be priming for resistance acquisition to the 2nd drug in the cycle.

Mutational signature analysis predicts MMR deficiency and MDR in P. aeruginosa isolates from pwCF

Our results thus far suggest that MMR deficiency produces a distinct mutational signature and drives rapid MDR acquisition, but that this can be targeted with rational combinations of treatments. We speculated that identification of the MMR deficiency-associated mutational signature itself could be a predictor of rapid drug resistance acquisition and potentially guide targeted treatment with combination therapy. To test this, we prospectively collected 26 isolates of P. aeruginosa from 15 subjects with bronchiectasis (CF or non-CF) chronically colonized with P. aeruginosa. Longitudinal isolates were collected from three subjects: S2, S6, and S7. We subsequently performed WGS, variant calling to PAO1, and deduplication of shared variants, and then plotted trinucleotide mutation spectra of unique mutations only. Trinucleotide mutation spectra from 7 subject isolates showed similar C > T enrichment in NCC and NCG and reduction in NCT and T > C enrichment in CTN and GTN that we saw with mutS- (Fig. 4a), whereas the spectra of the other 19 isolates did not display all of these characteristics (Supplementary Fig. 5a). These 7 isolates had overall elevated levels of unique single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Quantitative assessment via cosine similarity showed that spectra from these same 7 isolates were most similar to mutS- (Fig. 4b). From cosine similarity analysis and clustering results, all isolates with a cosine similarity with mutS- above 0.78 were predicted to be MMR-deficient, and all below 0.78 as WT, resulting in 7 predicted MMR-deficient isolates and 19 WT (27% isolates MMR-deficient). Interestingly, different subject isolates clustered based on decreasing degrees of similarity to the P. aeruginosa MMR-deficient mutational signature, with some being more similar to HumanΔMMR, SBS6, or SBS15 than P. aeruginosa mutS- (Fig. 4b). This same cluster (S18 Pa1 to S16 Pa1) also showed elevated similarity to SBS44 compared to P. aeruginosa mutS-. These six isolates show C > T enrichment but were lacking the dramatic C > T diminishment in NCT contexts and T > C enrichment, suggesting these are key distinguishing factors for theprediction of MMR status.

a Trinucleotide mutation spectra of predicted MMR-deficient isolates collected from 15 subjects with bronchiectasis (CF and non-CF). b Trinucleotide mutation spectra from patient isolates were compared to P. aeruginosa mutS-, Human ΔMMR, and each individual COSMIC SBS associated with MMR deficiency and clustered based on cosine similarities. c Mutant frequencies of all subject isolates were measured using rifampicin reversion (rpoB mutants resistant to rifampicin per 108 viable cells). Hypermutators are defined as those having mutant frequencies above the dotted line, which represents 20-fold higher than the mutant frequency of the WT MPAO1 parent strain. Clinical isolates predicted based on mutation spectra to be MMR-deficient and hypermutant are shown in blue. Clinical isolates predicted to be WT are shown in gray. Lab strains are shown in white. For each isolate, the presence (+) or absence (−) of nonsynonymous mutations in the indicated key MMR genes are denoted below. d Numbers of nonsynonymous mutations for each indicated key drug efflux or membrane-modifying gene are plotted for all subject isolates. Predicted MMR-deficient isolates are clustered at the top (blue text), and predicted WT isolates are clustered at the bottom (black text). e, f Representative resistance acquisition shown for subject isolates. Predicted MMR-deficient subject isolates rapidly acquired resistance to e aztreonam (AZ) and f colistin (COL), while WT isolates did not. g Combination treatment of S6T1 Pa2, a predicted MMR-deficient isolate, with aztreonam + colistin (AZ + COL) prevented resistance acquisition. c is shown as mean ± SD of independent biological triplicates. e–g is shown as mean ± SD of independent biological triplicates. ****p < 0.0001, ordinary one-way ANOVA of slopes from linear regression analysis of log-transformed datasets for comparison of S6T1 Pa2 + combination therapy vs S6T1 Pa2 + monotherapy.

Another notable finding was that the mutation spectrum of S6T1 Pa2 resembled mutS-, while the spectrum of S6T1 Pa1 did not (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 5a). Both isolates were collected from the same patient at the same time indicating infections from distinct isolates. A longitudinal isolate from the same subject, S6T2 Pa1, did not resemble mutS- either (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Our results predicted that S6T1 Pa2 would be MMR-deficient and more rapidly acquire MDR during in vitro experiments than the predicted MMR-proficient S6T1 Pa1 or S6T2 Pa1.

Predictions of MMR status were functionally validated by assessing for hypermutator phenotype via rifampicin reversion frequency (Fig. 4c). Additionally, all predicted MMR-deficient isolates had a nonsynonymous mutation in mutS, mutL, or uvrD. However, many validated WT isolates also had mutations in an MMR gene, indicating that assessing for genotype is an inaccurate determinant of MMR status (Fig. 4c). We next assessed all isolates for mutations in mex efflux operons and membrane-modifying operons. MMR-deficient isolates were slightly enriched in nalD mutations compared to WT isolates, similar to what we saw in AZ-treated MMR-deficient lab-evolved isolates (Fig. 4d). S6T1 Pa1 and S6T1 Pa2 had identical mutations in efflux and membrane-modifying operons with two exceptions, the Pa2 isolate had a mutation in mexB and an additional mutation in mexX. S6T2 Pa1 had a rather different profile of mutations, suggesting it is a distinct isolate through adaptive radiation59 (i.e. adaptive evolution of infecting isolates to occupy different niches in CF lung). All mutations in genes of interest called PAO1 are tabulated in Supplementary Data 2.

We next asked how well the mutS- mutational signature can predict rapid drug resistance in clinical isolates. We measured resistance acquisition and efficacy of combination therapy in a set of predicted MMR-deficient and WT patient samples in vitro. We then evolved strains in AZ alone, COL alone, and combined AZ + COL and measured resistance acquisition. Three predicted MMR-deficient isolates, S6T1 Pa2, S8 Pa1, and S9 Pa1, demonstrated MICs to AZ above CLSI-defined clinical breakpoints at the start of in vitro adaptive evolution. All three isolates acquired further resistance to AZ alone (Fig. 4e, pink lines) and rapidly acquired resistance to COL (Fig. 4f, blue lines). S9 Pa2 was heterogeneously susceptible to both monotherapies, but all clones rapidly acquired resistance similar to MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa laboratory strains (Fig. 4e, f). AZ + COL combination treatment prevented resistance acquisition in all predicted MMR-deficient clinical isolates, even in those with preexisting AZ resistance (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 5c–e, compare purple to pink and blue lines). Predicted WT clinical isolates either did not develop significant resistance acquisition or did so at a rate similar to WT MPAO1 (Fig. 4e, f, black lines). Combination therapy had no effect on resistance acquisition in MMR-proficient samples (Supplementary Fig. 5f–n), compare purple to pink and blue lines). Together, these results indicate that mutational signature analysis coupled with rational combination therapy is a promising precision medicine approach that can prevent the emergence of MMR deficiency-induced MDR in P. aeruginosa clinical isolates in vitro.

Although these results strongly suggest the diagnostic promise of mutational signature analysis, our test population was limited to subjects from one geographic area (LA, USA). To expand the breadth of our work’s translation, we applied our pipeline on publicly available WGS reads of 131 P. aeruginosa isolates from 50 pwCF in Spain60. Trinucleotide mutation spectra from 17 isolates strongly resembled mutS- and showed enrichment and diminishment in key discussed C > T and T > C contexts (Fig. 5a). Cosine similarity analysis predicted these 17 isolates as MMR-deficient and the remaining 114 as WT (13% MMR-deficient). Exact cosine similarities and predictions for all isolates are in Supplementary Data 3 and 4, respectively. A small cluster of 6 isolates showed higher similarity to HumanΔMMR, SBS6, and SBS15 than P. aeruginosa mutS- (Fig. 5b). Similar to our collected isolates, predicted MMR-deficient and WT isolates were indistinguishable by MMR genotype (Fig. 5c). These isolates had accompanying data on clinical resistance and hypermutator phenotype, allowing us the opportunity to validate our predictions. Of the 17 predicted MMR-deficient isolates, 11 were reported as hypermutators via rifampicin reversion (Fig. 5d, blue). All of the six remaining predicted MMR-deficient were not hypermutators (Fig. 5d, green), however, clustered with the mutS- samples (Fig. 5b, green stars). This suggests that these samples were at some point MMR deficient. The remaining 7 predicted WT isolates that were reported to be hypermutators (Fig. 5d, dark gray) did not cluster with the mutS- samples (Fig. 5b, gray circles). The hypermutator phenotypes in these samples are candidates for alternative causes. Despite incomplete agreement with hypermutator phenotype, predicted MMR-deficient isolates show a strong correlation (p = 0.0021 via Fisher’s exact) with MDR (defined by ‘R’ via EUCAST to ≥3 drugs) (Fig. 5e), as does the hypermutator phenotype like previously documented (Fig. 5f)12. Our application of mutational signature analysis in clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa shows that it can rather robustly, easily, and accurately screen for MMR deficiency and identify isolates prone to rapid MDR acquisition or enriched for MDR.

a Representative trinucleotide mutation spectra of isolates predicted as MMR-deficient from pwCF. b Clustering of trinucleotide mutation spectra based on cosine similarity from patient isolates using P. aeruginosa mutS-, HumanΔMMR, and each individual COSMIC SBS associated with MMR deficiency. c Percentage of predicted MMR-deficient and WT isolates containing nonsynonymous mutations in MMR genes. d Comparison of the mutator status for each isolate via rifampicin reversion reported by Lopez-Causape et al. (normal vs hypermutator) to the MMR status predicted by mutational signature (MMR-deficient vs WT) using the same dataset. Those isolates in blue were predicted MMR-deficient and confirmed hypermutant. Two sets of isolates showed discordance between prediction and observation. Those isolates in green were predicted MMR-deficient but were observed not to be mutators. Those isolates in dark gray were predicted to be WT but observed to be hypermutators. The isolates with discordant predictions indicated by green stars (MMR-deficient, normal) or gray circles (WT, hypermutant) in b and discussed more in the text. e, f Correlation of predicted MMR deficiency using e mutational signature analysis or f hypermutation from rifampicin reversion with MDR. Two-sided p values were calculated using Fisher’s exact test and found to be e p = 0.0021 and f p = 0.0009. MDR isolates were defined by clinical resistance (‘R’ via EUCAST) to ≥3 drugs.

Mutational signature analysis reveals presence of MMR deficiency in other contexts

Previous studies linking MMR deficiency and MDR in P. aeruginosa were largely focused on isolates from pwCF or other chronic lung infection contexts12,17,18,61. An early study screening isolates from intensive care units attributed the contribution of hypermutation in non-CF P. aeruginosa infections to <1%19. However, a few recent clinical case studies have suggested that MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa may be playing a more prominent role in non-CF disease contexts21,22. We used mutational signature analysis to investigate the frequency of MMR deficiency using publicly available datasets of WGS reads from 325 P. aeruginosa clinical isolates in four important human disease contexts: respiratory tract infections (RTIs), urinary tract infections (UTIs), intraabdominal infections (IAIs), and pwCF. Trinucleotide spectra from 22 isolates were predicted to be MMR-deficient via qualitative similarity with mutS- (Fig. 6a) and cosine similarity analysis (Fig. 6b). Cosine similarities along with predictions for all 325 isolates are in Supplementary Data 5 and 6, respectively. Predicted MMR-deficient isolates were enriched in pwCF (31% of the total pwCF isolates), similar to previous reports17,18 but were also found at significant levels in RTIs (5.5% of the total RTI isolates), UTIs (2.8% of the total UTI isolates), and IAIs (2.7% of the total IAI isolates) (Fig. 6c). We again observed a cluster of isolates with similarity to SBS6 that appeared across all four disease contexts (Fig. 6b). MMR-deficient isolates from pwCF were significantly correlated (p = 0.0256) with MDR (Fig. 6d) as seen previously12. Predicted MMR-deficient isolates trend towards higher rates of MDR in RTIs (Fig. 6e) and UTIs (Fig. 6f), but not IAIs (Fig. 6g). These results illuminate a potential larger and more appreciable role of MMR deficiency in non-CF infections of P. aeruginosa than previously accepted.

a Trinucleotide mutation spectra of those patient isolates predicted as MMR-deficient from three different patient cohorts: cystic fibrosis (CF); respiratory tract infection (RTI); urinary tract infection (UTI); and intraabdominal infection (IAI). b Trinucleotide mutation spectra from patient isolates were clustered based on cosine similarity to mutS-, Human ΔMMR, and each individual COSMIC SBS associated with MMR deficiency. c Percentage of isolates predicted as MMR-deficient or WT across the indicated disease contexts. d–g Percentage of MDR isolates out of those predicted as MMR-deficient vs. WT from (d) CF, (e) RTI, (f) UTI, and (g) IAI. MDR is defined by clinical resistance (‘R’ via CLSI) to ≥2 drugs. Two-tailed p = 0.0256 (d) via Fisher’s exact.

Discussion

MMR corrects replication errors made by very different DNA polymerases across domains of life, yet the accumulation of C > T and T > C transitions and frameshift mutations has been observed across species5,6,62,63,64. The power of WGS using large numbers of samples has allowed a much finer resolution of the consequences of MMR loss. In this work, we demonstrate that MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa mutational signature shows similarities to human MMR deficiency signatures, even at trinucleotide context resolution. However, our work highlights some key differences in the mutagenic context that we suggest could be due to codon usage bias resulting from high GC genomic content in P. aeruginosa65,66,67. Recently, a mutS-associated mutational signature was de novo extracted from a large dataset of P. aeruginosa genomes11. Our characterized mutS- signature overall shows high similarity to their presented signature, with both demonstrating enrichment of C > T in NCC and NCG and diminishment in NCT. However, their extracted signature shows more C > T in NCA contexts than we observed. T > C enrichment in CTN and GTN contexts is mirrored in both presented signatures. Computational extraction versus forward lab construction of mutational signatures is not necessarily more accurate and is highly dependent on the quality of the dataset used for extraction. However, computational extraction of signatures from large, heterogeneous datasets may be more broadly applicable than our lab-constructed signature using one strain of the same genetic background, especially in clinical diagnostic settings.

To build a potential clinical diagnostic tool, we demonstrated that strains producing this MMR-deficient mutational signature rapidly acquire MDR. This causal relationship between MMR deficiency and MDR was recently demonstrated in a clinical case of respiratory infection with MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa that longitudinally acquired AZ and ceftolozane-tazobactam resistance without treatment with either antibiotic21. Our work suggests that treatment of MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa could rapidly select for cross-resistance to non-treatment drugs, which is mediated by common selective pressures and shared mechanisms of resistance (e.g., drug efflux) to the initial drug used for treatment. These findings warn that antibiotic treatment of MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa could rapidly drive pan-resistance, as P. aeruginosa efflux pumps are promiscuous and have numerous drug substrates41. Our current study also suggests that empiric monotherapeutic cycling in MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa infections could accelerate MDR, thereby reducing the number of effective treatment options for patients. However, our current study is limited by the clinically relevant drugs tested, and future work is needed to evaluate rapid MDR acquisition upon exposure to other common antipseudomonal antibiotics.

Our findings of D-CONGA and D-CONGA-Q7 resistance in MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa enabled investigation into potential mechanisms of resistance to these investigational peptides. It is worth noting that levels of resistance to D-CONGA and D-CONGA-Q7 acquired by MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa were much lower than those of other compounds (e.g. AZ, COL). We identified two targets for mechanisms of resistance to these peptides, pmrB and opr86. Opr86 contributes to membrane biogenesis and can lead to over-vesiculation and membrane stress when mutated45, which has previously been attributed to antimicrobial peptide resistance68. Structural analyses suggest that lipid A structure selection plays a vital, yet different, role in resistance to both peptides. Namely, our results implicate differences in the regulation of PagP and PagL, key lipid A modifying enzymes previously linked to peptide resistance48 in response to D-CONGA and D-CONGA-Q7, but future work is needed to further elucidate these mechanisms. Treatment with D-CONGA-Q7 selects for lipid A modifications with AraN4, suggesting this common peptide resistance-conferring moiety does, in fact, confer resistance to D-CONGA-Q7 despite previous data from WT P. aeruginosa that suggested otherwise38. This finding also highlights the potential future use of hypermutator strains to investigate resistance mechanisms to novel compounds.

It is worth noting that in vitro evolution experiments in this work started with a seed population of ~103 CFU, so it is possible that resistance-conferring mutations were preexisting in this initial population rather than de novo acquired. However, we looked for mutations in genes or pathways made in parallel across independent biological replicates to minimize the chance of analyzing preexisting mutations. Additionally, all observed resistance-conferring mutations were in the MMR deficiency mutation spectra, supporting the likelihood of them being acquired de novo.

We found that a rational combination therapy approach showed effective prevention of MDR in MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa compared to monotherapies or the standard of care therapies in vitro35,36,57,69,70. In the current study, we defined rational combination therapy as combining two drugs that do not select for the same mechanism of resistance. An example of this, AZ + COL, was even effective against MMR-deficient clinical isolates with preexisting AZ resistance. This suggests that the addition of a drug imposing a distinct selective pressure prevents resistance acquisition to a different drug when applied in a rational combination. Current regimens of combination therapy often consist of two antibiotics from different classes (e.g. monobactam + fluoroquinolone), which our work suggests would be less effective in hypermutators due to shared mechanisms of resistance and likelihood of cross-resistance71. Further supporting the need for two drugs with competing mechanisms of resistance, TOB + COL treatment resulted in rapid drug resistance acquisition, unlike other tested combinations. It is possible that specific drug combinations could have different efficacies on MMR-deficient infections. Previous literature has demonstrated in vitro efficacy of meropenem-tobramycin55, ceftazidime-tobramycin53,54, meropenem-ciprofloxacin52, and tobramycin-ciprofloxacin51 in combination against hypermutator P. aeruginosa. More targeted rational combinations following this model must be tested to broaden treatment options for MMR-deficient infections. Still, our study stresses the need to consider potential mechanisms of resistance and cross-resistance when combining or cycling drugs in hypermutator infections.

Our analyses of P. aeruginosa strains isolated from subjects with chronic respiratory colonization demonstrate the potential of mutational signature analysis to predict MMR-deficient and hypermutator strains that are likely MDR-prone and might be prevented with rational combination therapy. We found similar proportions of predicted MMR-deficient isolates in our prospective subject sample collection and from two published patient datasets60,72 that are both in-line with previous reports16,17,18. Notably, looking for nonsynonymous mutations in MMR genes was not an accurate predictor of MMR status. This is likely due to the numerous variants of unknown significance and high divergence of clinical isolates from the PAO1 reference genome. Our approach to addressing this high divergence was to deduplicate variants across all samples in a related batch, leaving only mutations unique to each sample for analysis. In theory, this should maximize the likelihood of detecting true mutations as commonly shared variants across samples attributed to divergence were removed. Despite this, we still found levels of SNVs to be an inaccurate predictor of MMR status, with high mutation burdens found in S14 Pa1, S15 Pa1, S16 Pa1, and S17 Pa1. The lack of additional isolates from the same subject, which most other isolates had, would decrease the validity of deduplication and could explain this. Future applications of phylogenetic reconstruction and de novo reference genome assembly could help standardize SNV counts across isolates and clarify spectra. We also note that many clinical isolates displayed enrichment in C > T, especially in NCC and NCG contexts. It appears that the reduction in C > T in NCT contexts and the overall specificity of the T > C spectra were vital determining factors in predictions.

One case of particular interest was subject 6, from which we collected 2 isolates at the same time point, with one predicted to be MMR-deficient and one predicted to be WT. At a later timepoint, we collected an additional isolate predicted as WT but appeared distinct from both S6T1 Pa1 and S6T1 Pa2. This highlights the potential of coexistence of MMR-deficient and wild-type strains, additionally documented by others6,73. Previous work suggests under selective pressures, such as drug treatment, hypermutator strains dominate mixed populations74, but further studies are needed to clarify.

Although predicted MMR-deficient isolates from the Lopez-Causape et al.60 dataset were strongly correlated with MDR, they did not completely align with reporting of hypermutator phenotype. Rifampicin reversion frequency increases can come from sources other than MMR deficiency, including mutator phenotypes resulting from deficiencies in other repair pathways or preexisting rifampicin resistance in an isolate75,76. Mutation spectra represent all previously accumulated insults to the genome, so it is possible that an isolate can have very high similarity to mutS- but have subsequently acquired a mutation that suppresses the mutator phenotype76. Additionally, isolates predicted as WT but were reported as mutators could have very recently lost MMR activity and, therefore, have yet to acquire enough mutations to demonstrate a signal.

Interestingly, in all three clinical isolate datasets analyzed, we observed clustering of isolates with high cosine similarity to human SBS6 and sometimes human SBS15 but with less similarity to P. aeruginosa mutS-. Along with selecting for hypermutators, antibiotic treatment is also known to transiently increase mutation rates via rpoS-mediated suppression of mutS and upregulation of DNA polymerases IV (DinB) and V (UmuD’2 C)77,78,79,80,81,82. DNA polymerases IV and V are translesion synthesis (TLS) polymerases lacking a 3′→5′ exonuclease activity and are thus error-prone83,84,85, and they are hypothesized to not only help bacterial cells overcome antibiotic-induced DNA damage after treatment but also to promote adaptive evolution86. We propose this as a potential explanation for this clustering, but future work is needed involving de novo signature extraction and correlation to investigate the reasoning behind it. Treatment-induced MMR suppression and TLS-mediated mutagenesis have also been shown to drive cross-resistance acquisition and are of significant clinical concern87.

Our work also highlights the potential contribution of MMR deficiency in MDR in disease contexts outside of CF, which was previously thought to be low or negligible19. We show that MMR deficiency is present in appreciable proportions in RTIs, UTIs, and IAIs. These findings are additionally supported by recent documentation of clinical cases of MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa acute RTIs leading to rapid MDR, treatment failure, and eventual infection-induced mortality21,22. An additional consideration is multiple rounds of antibiotic treatment have been shown to co-select for MMR deficiency via genetic ‘hitchhiking’, implying strains circulating in hospitals and exposed to numerous previous rounds of treatment could be enriched for MMR deficiency, but further future work is needed23,88,89. Future work will focus on hospital-associated infection contexts, namely central line-associated bloodstream infections. Our findings suggest that MMR deficiency and rapid MDR acquisition should be seriously considered in broader ranges of P. aeruginosa infections and, importantly, underscores the imminent need for a clinically viable diagnostic screen.

Overall, our work shows that WGS and mutational signature analysis can be used to identify MMR-deficient bacteria that already are MDR or will rapidly acquire MDR. This rapid identification should help guide clinicians for potentially effective precision treatment, such as rational combination therapy, rather than relying on empiric therapy that could potentially drive further resistance. Currently, there are no viable diagnostics to determine MMR status, and targeted treatment regimens for MMR-deficient P. aeruginosa are not yet available. Clinical applications of WGS, such as metagenomic next-generation sequencing, are becoming widely available for sensitive and robust diagnosis of bacterial infections90 providing the framework for possible clinical implementation of mutational signature analysis. Early detection of MMR-deficient infections using WGS and mutational signature analysis could guide precision medical care leading to improved patient outcomes. In addition to P. aeruginosa, MMR deficiency is also observed in other ESKAPE (Enterococcus faecium, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp.) species91,92,93. Notably, up to 15% of A. baumannii intensive care unit isolates display a hypermutator phenotype94,95. Expanding the scope of this research has the potential to uncover the broader impact of MMR deficiency on the rise of bacterial MDR in clinical settings and could reveal vital information to help manage this global health crisis. Additionally, future work aims to characterize further signatures associated with alternative pathways potentially linked with clinical resistance phenotypes.

Methods

Ethics statement

Research conducted in this presented work complies with all relevant ethical regulations and informed consent was obtained from subjects. Human subjects research was monitored and approved by Tulane University Institutional Review Board (Tulane IRB 2019-1840).

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Wild-type, parent strain MPAO1and transposon mutants MPAO1-mutSTn (strain PW7149) and MPAO1-mutLTn (strain PW5709), were purchased from the Pseudomonas aeruginosa two allele transposon library of Colin Manoil, PhD at the University of Washington (funded by grant no. NIH P30 DK089507)29,30. P. aeruginosa strains were initially streaked on Pseudomonas Isolation Agar (PIA) (BD Difco). All strains were cultured in Luria Bertani (LB) broth (Miller) (VWR Life Sciences) at 37 °C at 220 rpm for 18 h to make glycerol-frozen stocks stored at −80 °C prior to experimentation.

Confirmation of insertional transposon knockout mutants

Insertional transposon mutants were confirmed via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with gene-flanking and transposon-annealing primer sets. The following primer sequences were used to confirm transposon insertion for MPAO1-mutSTn: 5′-CTGGATATCAACCTCAGCGG-3′ and 5′-GATTCAGGTCGAGGTTCAGC-3′ (expected no band), and 5′-GGGTAACGCCAGGGTTTTCC-3′ and 5′-CTGGATATCAACCTCAGCGG-3′ (expected size 554 bp). The following primer sequences were used to confirm transposon insertion for MPAO1-mutLTn: 5′-GTCGCGGATATCGATCAGG-3′ and 5′-AAGGGCATCTACATTCTCGC-3′ (expected no band), and 5′-GGGTAACGCCAGGGTTTTTCC-3′ and 5′-AAGGGCATCTACATTCTCGC-3′ (expected size 267 bp). Primer sets were first optimized on MPAO1. PCR products were visualized on 1% agarose gels via electrophoresis and mutant expected sizes were confirmed.

Rifampicin reversion frequency assays

Bacteria were streaked from glycerol stocks on LB agar, and independent triplicate colonies were inoculated into 10 mL Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB) (BD BBL) and incubated for 18 h overnight. 1 mL of each culture was pelleted at 4000 × g for 10 min, and the pellet was washed with sterile 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 3 times. The pellet was resuspended in 1 mL 1× PBS and serially diluted 10-fold in 1× PBS. Dilutions were spotted (10 μL) and spread (100 μL) on CAMHB agar and CAMHB agar containing 100 μg/mL rifampicin and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Mutant frequency was determined by mutants (colonies grown on CAMHB + rifampicin)/viable cells (colonies grown on CAMHB)14.

Antimicrobial peptide preparation

D-CONGA and D-CONGA-Q7 were synthesized using Fmoc solid-phase chemistry and purified to >95% via high-performance liquid chromatography by Bio-synthesis Inc., with identity confirmed via MALDI mass spectrometry. Solutions were prepared by dissolving the desired mass into 0.025% (v/v) acetic acid in water, and peptide concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

MICs were determined via microbroth dilution assay in 96-well culture plates (Falcon, U-bottom) following CLSI guidelines, with twofold serial dilutions of tested antibiotic in CAMHB, inoculated with 50 μL of 2.75 × 105 CFU/mL of each bacterial strain and incubated at 37 °C, 200 rpm for 24 h. MIC experiments were performed using biological triplicates.

In vitro adaptive evolution

Serial passaging of bacterial strains was performed in 96-well culture plates with twofold serial dilutions of antibiotic in CAMHB, inoculated with 50 μL 2.75 × 105 CFU/mL of each strain and incubated at 37 °C, 200 rpm for 24 h. Next, bacteria taken from the well with the highest concentration of antibiotic that still exhibited growth (compared to negative control with no inoculum) were diluted 1:100 into 5 mL of fresh LB containing no antibiotics and grown overnight. The bacteria were then serially passaged in the same antibiotic. The bacteria were serially passaged a total of 10 times.

MICs were determined for all antibiotics (aztreonam, ciprofloxacin, D-CONGA, D-CONGA-Q7, polymyxin B) after 1, 4, 7, and 10 complete passages in treatment (see Antimicrobial susceptibility testing). For this, a sample was removed from the entire population in liquid culture at the designated timepoint.

DNA purification

Aliquoted cultures of evolved clones from each lineage were stored at −80 °C after time of emergence of resistance and experimental endpoint. Frozen aliquoted cultures were thawed and pelleted (500 μL) at 4000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was discarded. Genomic DNA was isolated using a Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit per manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quality and concentration were determined via absorbance at 260 nm, 280 nm, and 230 nm.

WGS and variant calling

Genomic DNA preps from desired resistant and control lineages were whole genome sequenced using Illumina short-read sequencing (NextSeq 2000). Sample libraries were prepared using Illumina DNA Prep Kit and IDT 10 bp UDI indices. Demultiplexing, quality control (only reads with Q > 30 kept), and adapter trimming were performed using Illumina bcl-convert (v3.9.3). Each sample produced a minimum of 400 Mbp high-quality reads (2 × 151 bp), with an average depth of coverage of ×60 of the ~6.3 Mbp genome.

Paired-end reads were aligned to the PAO1 reference genome (NCBI accession #NC_002516.2), and variants were called to reference using breseq (v0.36.1)96. All variants called were at 100% frequency unless otherwise specified.

Identification of de novo mutations and candidate resistance mechanisms

For lab-evolved strains, variants that were common to the parental strain prior to adaptive evolution and that were common among all lineages with the same parental independent colony (i.e., common among all colony 1 lineages, so assumed to be in colony 1 prior to evolution) were excluded, leaving only candidate de novo mutations. Common de novo mutations among independent lineages under the same treatment were identified as candidate resistance-conferring mutations.

Mutational signature analysis

Variant call format (VCF) files containing all variants called to PAO1 for each sample were deduplicated, removing any variant shared with at least one other sample in the same batch from all samples, using bcftools97 to create unique VCFs for each sample. Separate ‘batches’ for deduplication included: all evolved lab strains, all prospectively clinical isolates from pwCF, retrospective clinical isolates from the dataset of Lopez-Causape et al. 60., and retrospective clinical isolates from the dataset of Kos et al.72. For analysis of lab evolved strains and construction of the mutS- mutational signature, only the final timepoint for each independent lineages was included, excluding longitudinal sequences from the same lineage at different timepoints.

Unique VCFs were loaded into and parsed in R using the tidyverse suite98. For each mutation, the reference base was retrieved from the PAO1 reference genome sequence along with flanking reference bases on both the 3′ and 5′ ends to produce the trinucleotide mutation context. Where necessary, trinucleotide contexts were converted to their reverse complement to reflect one of the canonical 6 types of bases changes (C > {A,G,T} or T > {A,C,G}). Individual mutation spectra were plotted in their 96-trinucleotide context. Due to few total detected de novo mutations, all mutations from mutS- samples were also compiled into one signature. Established human (hg38) MMR deficiency-associated mutational signatures were retrieved from the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC; SBS6/15/21/26/44). Human MMR signatures were also additively combined into a compiled signature. Cosine similarities between the mutation distributions of relevant samples and the COSMIC MMR-associated signatures were calculated using the R package MutationalPatterns99.

Lipid A extraction and MALDI-MS analysis

Lipid A structural analysis was performed, as previously described100. A single colony was scraped onto a steel target plate in duplicate with a toothpick. 1 µL of FLAT extraction buffer (0.2 M anhydrous citric acid, 0.1 M trisodium citrate dihydrate) was pipetted over bacterial spots. The FLAT target plate was incubated in a “Panini-Press” heat block at 100 °C for 30 min. Bacterial spots were washed with ddH2O and air-dried. 1 µL of 10 mg/mL Norharmane matrix was pipetted over bacterial spots. MALDI-TOF MS analysis was performed using a Bruker Microflex LRF equipped with a 337 nm nitrogen laser. Spectra were acquired in the negative ion mode. Analyses were conducted at < 60% global intensity with 300 laser shots for each spectrum acquisition. Spectra were recorded in triplicate. Agilent ESI tune mix (Agilent) was used for mass calibration.

All MALDI (timsTOF) MS and MS/MS data were visualized using mMass (Ver 5.5.0).5 Peak picking was conducted in mMass. Identification of all fragment ions was determined based on Chemdraw Ultra (Ver10.0).

Subject recruitment and isolate processing

Adult subjects with CF or non-CF bronchiectasis (8 male, 9 female) and a known history of P. aeruginosa chronic respiratory colonization were recruited from Tulane Medical Center (Tulane IRB 2019-1840), and informed consent was obtained. For S1 until S9: spontaneous sputum samples were collected in sterile screw-cap cups for processing. Samples were processed within 24 h of collection, kept at 4 °C overnight if needed, or processed directly from room temperature if within 4 h of collection. Sputum samples were processed with equal volume 6.5 mM DTT, vortexed for 45 s and rotated for 30 min. Processed sputum was streaked onto PIA for P. aeruginosa isolation. Colonies with distinct morphotypes were collected as different strains from each patient sample and pure-cultured on PIA.

For S10 until S19, sputum samples were processed by the clinical microbiology laboratory at Tulane Medical Center. Pure-cultured plates were then obtained.

Two collected samples, S10 Pa1, and S10 Pa2, were excluded from this study due to >5% divergence from PAO1 (see Whole genome sequencing and Mutational signature analysis).

Public dataset analyses

FASTQ files for all samples from datasets of Lopez-Causape et al.60 and Kos et al.72 were retrieved from NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) Run Selector using sra-tools. From the dataset of Lopez-Causape et al., the following samples were excluded from this study due to missing or insufficient quality reads: 004-526, 006-7204, 021-9884. 021-2955, 021-4234, 022-5179, 022-5546, 023-2344, 023-6966, 023-9557, 024-1092, 024-7416, 025-6546, 025-9260, 025-7986, OB2_38, OB2_50, OB2_23. From the dataset of Kos et al., the following samples were excluded from this study due to missing or insufficient quality reads: AZPAE13756, AZPAE13757, AZPAE13848, AZPAE13850, AZPAE13853, AZPAE13856, AZPAE13858, AZPAE13860, AZPAE13864, AZPAE13866, AZPAE13872, AZPAE13876, AZPAE13877, AZPAE13879, AZPAE13880, AZPAE14352, AZPAE14353, AZPAE14359, AZPAE14372, AZPAE14373, AZPAE14379, AZPAE14381, AZPAE14390, AZPAE14393, AZPAE14394, AZPAE14395, AZPAE14398, AZPAE14402, AZPAE14403, AZPAE14404, AZPAE14410, AZPAE14415, AZPAE14422, AZPAE14437, AZPAE14441, AZPAE14442, AZPAE14443, AZPAE14453, AZPAE14463, AZPAE14499, AZPAE14505, AZPAE14509, AZPAE14526, AZPAE14533, AZPAE14535, AZPAE14538, AZPAE14550, AZPAE14554, AZPAE14557, AZPAE14566, AZPAE14570, AZPAE14687, AZPAE14689, AZPAE14690, AZPAE14691, AZPAE14692, AZPAE14693, AZPAE14835, AZPAE14886, AZPAE14887, AZPAE14941, AZPAE14949, AZPAE15042.

Statistical analyses

All resistance acquisition data was analyzed in units of fold-change to normalize for differences in starting MIC across strains. Fold-change in MIC data for all strains and treatment groups was natural log-transformed and simple linear regression was performed considering each replicate fold-change value as an individual point. Slope, standard error of slope, and the total number of values of each treatment group of interest were analyzed via unpaired t-test (mutS- vs WT) or ordinary one-way ANOVA (cross-resistance acquisition of ABX + mutS- vs No ABX + mutS- vs ABX + WT), and α-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method. Differences in estimated mutation rate across treatment groups were determined via ordinary one-way ANOVA (Brown-Forsythe test). All figures were created and statistical tests were done using GraphPad Prism 9.3.1.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text or supplementary materials. All lipid A structural raw data files will be made available on GitHub or can be made available on request. This study used open-source code available on GitHub. Source data are provided with this paper.

Materials availability

All isolates collected in this study are available from the lead contact with a completed materials transfer agreement. All sequenced laboratory strains and patient isolates collected in this study, including de novo assemblies of S10 Pa 1, SP10 Pa2, SP11 Pa1, S12 Pa1, S12 Pa2, S12 Pa3, S7T2 Pa1, S14 Pa1, S15 Pa1, S16 Pa1, S17 Pa1, S18 Pa1, S18 Pa2, and S6T2 Pa1, have been deposited to National Center for Biotechnology Information BioProject, BioSample, and Sequence Read Archive with accession code PRJNA1009838. See Materials and Methods for specific tools used.

References

Radman, M., Matic, I., Halliday, J. A. & Taddei, F. Editing DNA replication and recombination by mismatch repair: from bacterial genetics to mechanisms of predisposition to cancer in humans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 347, 97–103 (1995).

Baross-Francis, A., Andrew, S. E., Penney, J. E. & Jirik, F. R. Tumors of DNA mismatch repair-deficient hosts exhibit dramatic increases in genomic instability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95, 8739–8743 (1998).

Radman, M. & Wagner, R. Missing mismatch repair. Nature 366, 722 (1993).

Hsieh, P. & Yamane, K. DNA mismatch repair: molecular mechanism, cancer, and ageing. Mech. Ageing Dev. 129, 391–407 (2008).

Lee, H., Popodi, E., Tang, H. & Foster, P. L. Rate and molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations in the bacterium Escherichia coli as determined by whole-genome sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E2774–83 (2012).

Marvig, R. L., Johansen, H. K., Molin, S. & Jelsbak, L. Genome analysis of a transmissible lineage of pseudomonas aeruginosa reveals pathoadaptive mutations and distinct evolutionary paths of hypermutators. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003741 (2013).

Lujan, S. A., Clark, A. B. & Kunkel, T. A. Differences in genome-wide repeat sequence instability conferred by proofreading and mismatch repair defects. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 4067–4074 (2015).

Kunkel, T. A. & Erie, D. A. DNA mismatch repair. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 681–710 (2005).

Nik-Zainal, S. et al. Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers. Cell 149, 979–993 (2012).

Alexandrov, L. B. et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500, 415–421 (2013).

Ruis, C. et al. Mutational spectra are associated with bacterial niche. Nat. Commun. 14, 7091 (2023).

Macía, M. D. et al. Hypermutation is a key factor in development of multiple-antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains causing chronic lung infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 3382–3386 (2005).

Smania, A. M. et al. Emergence of phenotypic variants upon mismatch repair disruption in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 150, 1327–1338 (2004).

Oliver, A., Baquero, F. & Blazquez, J. The mismatch repair system (mutS, mutL and uvrD genes) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: molecular characterization of naturally occurring mutants. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 1641–1650 (2002).

Varga, J. J. et al. Genotypic and phenotypic analyses of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa chronic bronchiectasis isolate reveal differences from cystic fibrosis and laboratory strains. BMC Genomics 16, 883 (2015).

Hogardt, M., Schubert, S., Adler, K., Götzfried, M. & Heesemann, J. Sequence variability and functional analysis of MutS of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolates. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 296, 313–320 (2006).

Oliver, A., Cantón, R., Campo, P., Baquero, F. & Blázquez, J. High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science 288, 1251–1253 (2000).

Feliziani, S. et al. Mucoidy, quorum sensing, mismatch repair and antibiotic resistance in pseudomonas aeruginosa from cystic fibrosis chronic airways infections. PLoS One 5, 1–12 (2010).

Gutiérrez, O., Juan, C., Pérez, J. L. & Oliver, A. Lack of association between hypermutation and antibiotic resistance development in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from intensive care unit patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48, 3573–3575 (2004).

Hall, L. M. C. & Henderson-Begg, S. K. Hypermutable bacteria isolated from humans–a critical analysis. Microbiology 152, 2505–2514 (2006).

Khil, P. P. et al. Dynamic emergence of mismatch repair deficiency facilitates rapid evolution of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance in pseudomonas aeruginosa acute infection. mBio 10, e01822–19 (2019).

Nozick, S. H. et al. Phenotypes of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa hypermutator lineage that emerged during prolonged mechanical ventilation in a patient without cystic fibrosis. mSystems 9, e0048423 (2024).

Dößelmann, B. et al. Rapid and consistent evolution of colistin resistance in extensively drug-resistant pseudomonas aeruginosa during morbidostat culture. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, e00043–17 (2017).

Cabot, G. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ceftolozane-tazobactam resistance development requires multiple mutations leading to overexpression and structural modification of AmpC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 3091–3099 (2014).

Cabot, G. et al. Evolution of pseudomonas aeruginosa antimicrobial resistance and fitness under low and high mutation rates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 1767–1778 (2016).

Gomis-Font, M. A. et al. In vitro dynamics and mechanisms of resistance development to imipenem and imipenem/relebactam in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75, 2508–2515 (2020).

Barceló, I. et al. In vitro evolution of cefepime/zidebactam (WCK 5222) resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: dynamics, mechanisms, fitness trade-off and impact on in vivo efficacy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 76, 2546–2557 (2021).

Gomis-Font, M. A., Sastre-Femenia, M. À., Taltavull, B., Cabot, G. & Oliver, A. In vitro dynamics and mechanisms of cefiderocol resistance development in wild-type, mutator and XDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 78, 1785–1794 (2023).

Held, K., Ramage, E., Jacobs, M., Gallagher, L. & Manoil, C. Sequence-verified two-allele transposon mutant library for pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 194, 6387–6389 (2012).

Jacobs, M. A. et al. Comprehensive transposon mutant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 14339–14344 (2003).

Yu, Q. et al. In vitro evaluation of tobramycin and aztreonam versus Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms on cystic fibrosis-derived human airway epithelial cells. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 2673–2681 (2012).

Elson, E. C., Mermis, J., Polineni, D. & Oermann, C. M. Aztreonam lysine inhalation solution in cystic fibrosis. Clin. Med. Insights Circ. Respir. Pulm. Med. 13, 117954841984282 (2019).

Bassetti, M., Vena, A., Croxatto, A., Righi, E. & Guery, B. How to manage Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Drugs Context 7, 212527 (2018).

Starr, C. G. et al. Synthetic molecular evolution of host cell-compatible, antimicrobial peptides effective against drug-resistant, biofilm-forming bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 8437–8448 (2020).

Mogayzel, P. J. et al. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 187, 680–689 (2013).

Mogayzel, P. J. et al. Cystic fibrosis foundation pulmonary guideline. pharmacologic approaches to prevention and eradication of initial Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 11, 1640–1650 (2014).

Ghimire, J. et al. Optimization of host cell-compatible, antimicrobial peptides effective against biofilms and clinical isolates of drug-resistant bacteria. ACS Infect. Dis. 9, 952–965 (2023).

Ghimire, J., Guha, S., Nelson, B. J., Morici, L. A. & Wimley, W. C. The remarkable innate resistance of Burkholderia bacteria to cationic antimicrobial peptides: insights into the mechanism of AMP resistance. J. Membr. Biol. 255, 503–511 (2022).

Sidorenko, J., Jatsenko, T. & Kivisaar, M. Ongoing evolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 sublines complicates studies of DNA damage repair and tolerance. Mutat. Res. 797–799, 26–37 (2017).

Luong, P. M. et al. Emergence of the P2 phenotype in pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 strains involves various mutations in mexT or mexF. J. Bacteriol. 196, 504–513 (2014).

Fernández, L. & Hancock, R. E. W. Adaptive and mutational resistance: role of porins and efflux pumps in drug resistance. Clin. Microbiol Rev. 25, 661–681 (2012).

Dulanto Chiang, A. et al. Hypermutator strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa reveal novel pathways of resistance to combinations of cephalosporin antibiotics and beta-lactamase inhibitors. PLoS Biol. 20, e3001878 (2022).

López-Causapé, C. et al. Cefiderocol resistance genomics in sequential chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 29, 538.e7–538.e13 (2023).

López-Causapé, C. et al. Evolution of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutational resistome in an international cystic fibrosis clone. Sci. Rep. 7, 5555 (2017).

Romano, K. P. et al. Mutations in pmrB confer cross-resistance between the LptD inhibitor POL7080 and colistin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63, e00511-19 (2019).

McBroom, A. J. & Kuehn, M. J. Release of outer membrane vesicles by Gram-negative bacteria is a novel envelope stress response. Mol. Microbiol. 63, 545–558 (2007).

Tashiro, Y. et al. Opr86 is essential for viability and is a potential candidate for a protective antigen against biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 190, 3969–3978 (2008).

Jochumsen, N. et al. The evolution of antimicrobial peptide resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is shaped by strong epistatic interactions. Nat. Commun. 7, 13002 (2016).

Moskowitz, S. M., Ernst, R. K. & Miller, S. I. PmrAB, a two-component regulatory system of pseudomonas aeruginosa that modulates resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides and addition of aminoarabinose to lipid A. J. Bacteriol. 186, 575–579 (2004).

Owusu-Anim, D. & Kwon, D. H. Differential role of two-component regulatory systems (phoPQ and pmrAB) in polymyxin B susceptibility of pseudomonas aeruginosa. Adv. Microbiol 02, 31–36 (2012).

Giordano, N. P., Cian, M. B. & Dalebroux, Z. D. Outer membrane lipid secretion and the innate immune response to gram-negative bacteria. Infect. Immun. 88, e00920 (2020).

Douglass, M. V., Cléon, F. & Trent, M. S. Cardiolipin aids in lipopolysaccharide transport to the gram-negative outer membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2018329118 (2021).

Rees, V. E., Bulitta, J. B., Oliver, A., Nation, R. L. & Landersdorfer, C. B. Evaluation of tobramycin and ciprofloxacin as a synergistic combination against hypermutable pseudomonas aeruginosa strains via mechanism-based modelling. Pharmaceutics 11, 470 (2019).

Rees, V. E. et al. Meropenem combined with ciprofloxacin combats hypermutable pseudomonas aeruginosa from respiratory infections of cystic fibrosis patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 62, e01150-18 (2018).

Tait, J. R. et al. Pharmacodynamics of ceftazidime plus tobramycin combination dosage regimens against hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates at simulated epithelial lining fluid concentrations in a dynamic in vitro infection model. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 26, 55–63 (2021).

Bilal, H. et al. Simulated intravenous versus inhaled tobramycin with or without intravenous ceftazidime evaluated against hypermutable pseudomonas aeruginosa via a dynamic biofilm model and mechanism-based modeling. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 66, e0220321 (2022).

Bilal, H. et al. Synergistic meropenem-tobramycin combination dosage regimens against clinical hypermutable pseudomonas aeruginosa at simulated epithelial lining fluid concentrations in a dynamic biofilm model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63, e01293–19 (2019).

Bolard, A. et al. Production of norspermidine contributes to aminoglycoside resistance in pmrAB mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63, e01044–19 (2019).

Nick, J. A. et al. Azithromycin may antagonize inhaled tobramycin when targeting Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 11, 342–350 (2014).

Rojo-Molinero, E. et al. Sequential treatment of biofilms with aztreonam and tobramycin is a novel strategy for combating pseudomonas aeruginosa chronic respiratory infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 2912–2922 (2016).

Hall, K. M., Pursell, Z. F. & Morici, L. A. The role of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa hypermutator phenotype on the shift from acute to chronic virulence during respiratory infection. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 12, 943346 (2022).

Colque, C. A. et al. Hypermutator pseudomonas aeruginosa exploits multiple genetic pathways to develop multidrug resistance during long-term infections in the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64,e02142-19 (2020).

Glickman, B. W. & Radman, M. Escherichia coli mutator mutants deficient in methylation-instructed DNA mismatch correction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 77, 1063–1067 (1980).

Jones, M., Wagner, R. & Radman, M. Repair of a mismatch is influenced by the base composition of the surrounding nucleotide sequence. Genetics 115, 605–610 (1987).

Meier, B. et al. Mutational signatures of DNA mismatch repair deficiency in C. elegans and human cancers. Genome Res. 28, 666–675 (2018).