Abstract

Spin-polarized lasers have demonstrated many superiorities over conventional lasers in both performance and functionalities. Hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites are emerging spintronic materials with great potential for advancing spin-polarized laser technology. However, the rapid carrier spin relaxation process in hybrid perovskites presents a major bottleneck for spin-polarized lasing. Here we report the identification and successful suppression of the spin relaxation mechanism in perovskites for the experimental realization of spin-polarized perovskite lasers. The electron-hole exchange interaction is identified as the decisive spin relaxation mechanism hindering the realization of spin-polarized lasing in perovskite microcrystals. An ion doping strategy is employed accordingly to introduce a new energy level in perovskites, which enables a long carrier spin lifetime by suppressing the electron-hole exchange interaction. As a result, spin-polarized lasing is achieved in the doped perovskite microcrystals. Moreover, the doped cation is a magnetic species allowing for the magnetic field control of the spin-polarized perovskite lasing. This work unlocks the potential of perovskites for spin-polarized lasers, providing guidance for the design of perovskites towards spintronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A spin-polarized laser is a unique coherent light source based on the stimulated emission of spin-polarized carriers1,2. The spin-polarized laser generates a new function, circularly polarized laser emission, through the conversion of spin angular momentums from carriers to photons3,4. In addition, the spin-polarized lasers have many superiorities in performance, such as lasing threshold, efficiency, and modulation speed5,6,7. By virtue of the new function and superior performance, the spin-polarized lasers have great potential in a wide range of fields, such as asymmetric synthesis, chiral sensing, displays, chiroptics, spintronics, valleytronics, and optical communications1,8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

The spin polarization for circularly polarized lasing relies on the spin splitting of electronic bands by spin–orbit interaction4,15. This stringent requirement has severely limited the choice of candidate materials for spin-polarized lasers. So far, most spin-polarized lasers have been demonstrated based on GaAs quantum wells with large spin–orbit coupling1,16,17. Besides, the spin-polarized lasers suffer from low degrees of circular polarization because the recombination of spin-imbalanced electrons with degenerated light and heavy holes produces opposite circularly polarized emission18. Recently, hybrid organic–inorganic perovskites have emerged as excellent spintronic materials combining giant spin–orbit coupling and lifted spin degeneracy of light and heavy holes19,20,21,22,23,24. As direct-bandgap semiconductors, the perovskites are also outstanding gain media for laser oscillations25,26,27,28,29. Hence, they have rapidly become promising candidates for exploring spin-polarized lasers30,31. However, the fast carrier spin relaxation processes in hybrid perovskites make it challenging to sustain spin polarization for lasing32,33.

As a long spin relaxation lifetime is beneficial for achieving spin-polarized lasing in perovskites, various strategies have been developed to suppress the carrier spin relaxation processes31,32,34,35. However, the realization of spin-polarized lasing remains elusive in perovskites because their carrier spin lifetimes are still too short to sustain sufficient spin polarization before laser generation. In particular, the complex carrier spin relaxation processes mainly through Elliott–Yafet (EY), D’yakonov–Perel’ (DP), and Bir–Aronov–Pikus (BAP) mechanisms36,37 make it even more difficult to find a strategy of increasing the carrier spin lifetime of perovskites towards spin-polarized lasing.

In this work, we identify and successfully suppress the dominant spin relaxation mechanism in the lasing regime of perovskites, enabling the experimental realization of spin-polarized perovskite lasers. The BAP mechanism based on the electron–hole exchange interaction was identified as the decisive factor hindering the realization of spin-polarized lasing in perovskites. Accordingly, a type of divalent metal cation was doped into the perovskite microcrystals to introduce a new energy level capable of suppressing the electron–hole exchange interaction by trapping a portion of carriers, which led to a fourfold increase in the carrier spin lifetime of the perovskites. By virtue of the effective carrier spin polarization, spin-polarized lasing with a degree of circular polarization up to 27.3% was realized in the perovskite microcrystal under optical spin injection. Furthermore, the doped cations exhibited a characteristic of amplifying the magnetic effect on carrier spin in the perovskite microcrystal, which enabled magnetic field control of the spin-polarized perovskite lasing. These results establish an ion doping strategy for improving the spintronic performance of perovskites toward spin-polarized lasing.

Results and discussion

Doping of perovskites for effective spin polarization

With excellent optical gain and spin properties, the methylammonium lead bromide (MAPbBr3, upper pane of Fig. 1a) perovskite is a promising candidate for realizing spin-polarized lasers23,24,25,26. The MAPbBr3 perovskite microcrystals were synthesized through a liquid-phase self-assembly method (Supplementary Fig. 1, see “Methods” for preparation details). Figure 1b shows a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the synthesized MAPbBr3 microcrystals with square plate morphologies. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectrum and selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern reveal the cubic phase of MAPbBr3 microcrystals (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3).

a Schematic diagrams showing the MAPbBr3 perovskite and the spin relaxation process through electron–hole exchange interaction (BAP mechanism). b SEM image of MAPbBr3 perovskite microcrystals with square morphologies and smooth surfaces. Scale bar is 2 μm. c–e Spin relaxation kinetics (black) of MAPbBr3 microcrystals obtained by subtraction of two sets of circularly polarized TA signals (red and blue) in the same and different polarization configurations under c low pumping at 293 K, d low pumping at 80 K, and e high pumping at 293 K. The spin relaxation kinetics is exponentially fitted to evaluate the spin relaxation time (τspin). f The fitted spin lifetime of MAPbBr3 microcrystals as a function of the excitation power and temperature. The spin lifetimes of MAPbBr3 microcrystals at all temperatures dramatically decrease at high pump fluences, identifying the electron–hole exchange interaction as the dominant spin relaxation mechanism in the lasing regime of perovskites.

The carrier spin relaxation dynamics was investigated in the MAPbBr3 microcrystals through the circularly polarized transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy. The pump-probe configuration consists of a right circularly polarized pump laser (σ+pump) and right/left circularly polarized probe lights (σ+probe/σ−probe) (Supplementary Fig. 4). Figure 1c shows the spin relaxation dynamics of the MAPbBr3 microcrystals under low pumping (0.2 μJ/cm2) at room temperature (293 K). The ground-state photobleaching signal in the same polarization (σ+pumpσ+probe) increases at the expense of that in the opposite polarization (σ+pumpσ−probe), which is a typical signature of carrier spin flip process38,39. The net spin relaxation kinetics is obtained by subtracting the σ+pumpσ−probe signals from σ+pumpσ−probe signals and is exponentially fitted to evaluate the spin relaxation times. The spin relaxation time was calculated to be 14.49 ps, which is too short to sustain efficient spin polarization for lasing (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b).

To find a strategy of achieving spin-polarized lasing in perovskites, we first attempted to probe the carrier spin relaxation mechanism in the MAPbBr3 microcrystals (Fig. 1c–f). As shown in Fig. 1c, d, f, with temperature decreasing from 293 K to 80 K, the spin relaxation time notably increases from 14.49 ps to 39.22 ps. The temperature-dependent spin relaxation time identifies that the EY mechanism dominates the spin relaxation process in MAPbBr3 microcrystals at room temperature19,33. Despite the significant increase in the spin lifetime at low temperature, the MAPbBr3 microcrystal cannot enable spin-polarized lasing yet (Supplementary Fig. 5c, d). This implies that the spin–orbit coupling is not the major reason destroying spin polarization for lasing in MAPbBr3 microcrystals. As shown in Fig. 1c, e, f, with the pump fluence increasing from 0.2 μJ/cm2 to 2.5 μJ/cm2, the spin relaxation time dramatically decreases from 14.49 ps to 4.24 ps. Since the increase in densities of photogenerated electrons and holes can enhance the electron–hole exchange interaction, the distinct pump fluence-dependent spin relaxation time indicates that the BAP mechanism dominates the spin relaxation process in MAPbBr3 microcrystals under high pumping conditions (lower panel of Fig. 1a)39,40. This indicates that the electron–hole exchange interaction is the decisive factor hindering the realization of spin-polarized lasing in MAPbBr3 microcrystals.

Accordingly, we employ an ion doping strategy to suppress the electron–hole exchange interaction in the MAPbBr3 microcrystals towards spin-polarized lasing (upper panel of Fig. 2a). The introduction of divalent manganese cations (Mn2+) is expected to construct a new energy level in the MAPbBr3 perovskite, which would weaken the electron–hole exchange interaction by trapping part of electrons or holes (lower panel of Fig. 2a). The Mn-doped MAPbBr3 (Mn-MAPbBr3) microcrystals were synthesized with the same liquid-phase self-assembly method (Supplementary Fig. 1, see “Methods” for preparation details). By changing the contents of manganese bromides (MnBr2) in the perovskite precursor solutions, we were able to synthesize high-quality MAPbBr3 microcrystals with the Mn doping concentrations (cMn) ranging from 0 to 3.7 wt‰ (Supplementary Figs. 6–9). The Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals (cMn ≤3.7‰) share the same square morphology as the pure MAPbBr3 ones, indicating that the introduction of a small amount of Mn2+ does not affect the crystal growth of MAPbBr3 perovskites. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) evidences the successful introduction and uniform distribution of Mn in the MAPbBr3 microcrystal (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 10). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) reveals the formation of [MnBr6]4− in the MAPbBr3 microcrystal (Supplementary Fig. 11). As shown in Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3, the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals exhibit almost the same XRD spectrum and SAED pattern as the pure MAPbBr3 ones, indicating that the MAPbBr3 microcrystal maintains its high crystallinity and original crystal structure after Mn doping. A very small shift of the XRD peak towards a high angle reveals a lattice contraction of the MAPbBr3 perovskite crystal, which confirms the successful introduction of smaller Mn2+ compared with Pb2+ in the MAPbBr3 microcrystal41. Overall, high-quality Mn-MAPbBr3 perovskite microcrystals were successfully synthesized, which is beneficial for low-threshold lasing (Supplementary Fig. 12).

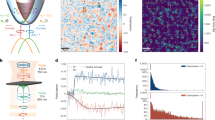

a Schematic diagrams showing the Mn-MAPbBr3 perovskite and the suppression of spin relaxation process by a trap level. The Mn-induced trap states disturb the electron–hole exchange interaction by capturing part of holes toward, therefore effectively suppressing the spin relaxation process. b TEM image and EDS mapping of a Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal, showing uniform doping of Mn elements in the perovskite microcrystal. Scale bars are 2 μm. c TA spectra of Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals at different delay times under linearly polarized configuration. The emergence of PB bands ranging from 550 nm to 580 nm after Mn doping is caused by the filling of trap states. d Spin relaxation kinetics (black) of Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals obtained by subtraction of two sets of circularly polarized TA signals (red and blue) at 530 nm in the same and different polarization configurations under high pumping at 293 K. The spin relaxation kinetics is exponentially fitted to evaluate the spin relaxation time (τspin). e TA kinetics probed at 530 nm of the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals with different Mn doping concentrations under high pumping. The rapid decay amplitude increases gradually from 0.8% to 27.8% with the Mn concentration. f Spin relaxation time and portion of trapped holes of Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals as a function of the Mn doping concentration. The spin lifetime and the portion of trapped holes in MAPbBr3 microcrystals share the same variation trend with the Mn concentration increasing, indicating that the prolonged spin relaxation time is attributed to the trap levels capturing holes.

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 13, the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals exhibit a low-energy tail in their absorption spectrum compared with that of pure MAPbBr3 microcrystals, which suggests the introduction of trap states in MAPbBr3 microcrystals by Mn doping42,43. The trap-involved carrier dynamics was investigated by TA spectroscopy. Note that the TA spectra of Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals under moderate and high pumping conditions were collected for investigating the type of trapped carriers and the influence of trap states on spin relaxation, respectively. Both the pure and doped MAPbBr3 microcrystals are characterized by typical ground-state photobleaching (PB) peaks around 530 nm (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 14). Nevertheless, only the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals present weak and broad PB bands ranging from 550 nm to 580 nm, which is attributed to the filling of trap states. The TA kinetics reveals the emergence of a rapid decay process in the ground-state PB signal accompanied by a fast rise process in the trap state PB signal within 1 ps in the MAPbBr3 microcrystals after Mn doping (Supplementary Fig. 15), which corresponds to a fast trapping process of the band-edge carriers by the trap states34,44,45. Under moderate pumping (1 μJ/cm2), the rapid decay amplitude increases from 2.7% to a plateau value of ~36.7% with the Mn concentration increasing from 0 to 3.7‰ (Supplementary Fig. 16), The maximum increment of the rapid decay amplitude of ~34% with the introduction of Mn is consistent with the theoretical contribution of holes in TA signals, which implies that the type of trapped carriers is holes46,47.

Because the hole trapping can weaken the electron–hole exchange interaction48,49, the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals are expected to enable a long spin lifetime. When the Mn doping concentration increases from 0 to 3.7‰, the spin lifetime of the MAPbBr3 microcrystals increases from 4.24 ps to 17.28 ps under high pumping (2.5 μJ/cm2) (Fig. 2d). To better understand the influence of hole trapping on spin relaxation, we further analyzed the TA measurements on the MAPbBr3 microcrystals with different Mn concentrations under high pumping (Fig. 2e). Under the condition of high pumping and consequently a high carrier density, the rapid decay amplitude increases gradually from 0.8% to 27.8% with the Mn concentration increasing from 0 to 3.7‰, from which we calculated the portion of trapped holes increasing from 2.6 to 83.3% (Fig. 2f). Apparently, the spin relaxation time and the portion of trapped holes in MAPbBr3 microcrystals share the same variation trend with the Mn concentration increasing, indicating that the prolonged spin relaxation time is attributed to the trap levels suppressing electron–hole exchange interaction by capturing holes. The long spin lifetime of the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals means the effective maintenance of carrier spin polarization for laser generation, which is beneficial for the realization of spin-polarized lasing.

Spin-polarized lasing in Mn-doped perovskite microcrystals

Figure 3a shows typical Mn-MAPbBr3 perovskite microcrystals with efficient green photoluminescence (PL). Note that no notable Mn2+ emission is observed around 590 nm in the Mn-doped MAPbBr3 microcrystals because the Br-based perovskite has a bandgap comparable to that of Mn2+, going against energy transfer from the perovskite to Mn2+ (Supplementary Fig. 17)50,51. The individual Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals exhibit a high homogeneity in the carrier spin property as they have spin lifetimes of 16.86 ± 0.32 ps (Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19) close to that of ensembles of Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals (17.28 ps, Fig. 2d). In addition, the square Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals can function as optical gain media and microcavities simultaneously for realizing laser oscillations27,52. Overall, the individual Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals combining spin polarization, optical gain, and microcavity effect have the potential to realize spin-polarized lasing.

a PL image of square Mn-MAPbBr3 perovskite microcrystals, showing typical green emission. Scale bar is 5 μm. b Emission spectra from a Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal under right circularly polarized excitation of different pump fluences, exhibiting the evolution from broad spontaneous emission to sharp lasing. Insets: corresponding PL image of the microcrystal above the lasing threshold. c Plots of emission intensities versus pump fluences, from which the lasing threshold was derived to be 10.0 μJ/cm2. d Right and left circularly polarized components of the laser emission from the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal. The DCP of the spin-polarized laser emission is estimated to be as high as 27.3%. e, f Polarization angle-dependent intensities of the laser emission from the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal under right and left circularly polarized excitation after passing through a quarter-wave plate. The chirality of spin-polarized laser output from the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal changes with that of the pump source. σ+pump/σ−pump, right/left circularly polarized pumping; σ+det/σ−det, right/left circularly polarized emission components.

Optically pumped lasing of the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals was characterized by a micro-photoluminescence measurement system at room temperature (Supplementary Fig. 20). As shown in Fig. 3b, a right circularly polarized pump laser was used for spin injection in a Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal (cMn = 3.7‰) to induce spin-polarized lasing. With the increase of pump fluence, the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal exhibits a clear evolution from weak and broad spontaneous emission to strong and sharp laser peaks. The microcavity effect in Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals with different sizes reveals that the laser peaks are stimulated emission amplified whispering-gallery modes (Supplementary Fig. 21)53,54. The coherence of laser emission from the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal is demonstrated through Michelson interference (Supplementary Fig. 22). The lasing action in the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal was confirmed by the nonlinear increase in the light emission versus the pump fluence (Fig. 3c)55,56. The S-shaped nonlinear dependence of the emission intensity on the pump fluence reveals the transition from spontaneous emission via amplified spontaneous emission to full lasing emission (Supplementary Fig. 23)53,57. The lasing threshold was derived to be 10.0 μJ/cm2 a little lower than that under linearly polarized excitation. In addition, the spin polarization-induced lasing threshold reduction of the MAPbBr3 microcrystal increases with the Mn concentration (Supplementary Fig. 24).

Unlike the pure MAPbBr3 microcrystals, the Mn-MAPbBr3 ones can maintain long carrier spin lifetimes at high pump fluences up to the lasing threshold of ~10 μJ/cm2 (Supplementary Fig. 25). In other words, the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals maintain spin polarization for obtaining circularly polarized laser emission. The circular polarization of the laser signal was characterized by selectively collecting its right and left circularly polarized components (Supplementary Fig. 26)58,59. The laser output from the pure MAPbBr3 microcrystal is linearly polarized as it has the same right and left circularly polarized components (Supplementary Fig. 5a). By sharp contrast, the laser output from the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal has notably different right and left circularly polarized components (Fig. 3d, e and Supplementary Fig. 27), revealing a degree of circular polarization (DCP) of 27.3%. Because the Mn enhances the carrier spin polarization in the MAPbBr3 microcrystal, the DCP of the laser signal from the MAPbBr3 microcrystal increases from 0 to 27.3% as the Mn doping concentration rises from 0 to 3.7‰ (Supplementary Fig. 28). As the carrier cooling reduces spin polarization, the circular degree of polarization of laser emission from the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal increases with excitation wavelength (Supplementary Figs. 29 and 30). Furthermore, the chirality of the spin-polarized laser output from the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal can be switched from right- to left-handedness by changing the chirality of the circularly polarized pump source (Fig. 3e, f and Supplementary Fig. 27). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that spin-polarized lasing has been reported in the perovskites so far.

Besides enhancing spin polarization, the Mn2+ is a typical magnetic ion capable of amplifying the magnetic effect on carrier spin (Fig. 4a), which offers a possibility to manipulate the spin-polarized lasing more efficiently with a magnetic field B60,61. The magnetic field lifts the degeneracy of the spin states (Zeeman effect), thermodynamically favoring the spin flipping from high to low spin states towards spin polarization62,63,64. However, the pure MAPbBr3 microcrystal without spin injection does not exhibit circularly polarized lasing under the magnetic field up to 0.5 T (Supplementary Fig. 31), indicating a negligible Zeeman splitting. By contrast, even under linearly polarized pumping, the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal supports circularly polarized lasing upon applying a magnetic field (Fig. 4b). This verifies a distinct enhancement of Zeeman splitting in the MAPbBr3 microcrystal by Mn doping60. As a result, the DCP of the laser emission from the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal increases with the magnetic field (Fig. 4c), which suggests great potential for exploring magnetic control of spin-polarized lasing.

a Schematic illustration of Mn-enhanced Zeeman splitting for effective magnetic control of spin-polarized lasing. b Circularly polarized components of the laser emission from a Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal under linearly polarized excitation in different magnetic fields. c Magnetic field-dependent DCPs of the laser emission from MAPbBr3 and Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals under linearly polarized excitation. This indicates that Mn2+ enhances the Zeeman splitting in the MAPbBr3 microcrystal. d Right and left circularly polarized components of the laser emission from a Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal under right circularly polarized excitation in different magnetic fields. The DCP of spin-polarized lasing undergoes a substantial increase (decrease) in the presence of a positive (negative) magnetic field. e Magnetic field-dependent DCPs of the laser emission from the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal under left and right circularly polarized excitation. The DCP of the laser emission is dynamically tuned from ~10% to ~40% by changing the magnetic field from −0.5 T to 0.5 T. Lpump, linearly polarized pumping.

Figure 4d shows the spin-polarized laser spectra from a Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal under right circularly polarized pumping at different magnetic fields. The spin-polarized lasing is remarkably enhanced and weakened by a positive and negative magnetic field, respectively. Nevertheless, the situation is the opposite for left circularly polarized pumping (Supplementary Fig. 32). As shown in Fig. 4e, the DCP of the laser emission from the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystal is increased from ~10% to ~40% by changing the magnetic field from −0.5 T to 0.5 T. Overall, we realized the magnetic control of spin-polarized lasing by exploiting the magnetic Mn2+ in perovskites.

In summary, we have realized spin-polarized lasing in Mn-doped MAPbBr3 perovskite microcrystals. The introduction of Mn2+ cations created a new energy level in the MAPbBr3 perovskite. This additional energy level effectively weakened the electron–hole exchange interaction by capturing part of the holes, remarkably extending the carrier spin lifetimes of the MAPbBr3 perovskites. Hence, spin-polarized lasing was successfully achieved in the Mn-MAPbBr3 microcrystals. In addition, the magnetic Mn2+ enhanced the Zeeman splitting in the MAPbBr3 microcrystals, allowing for the magnetic field control of the spin-polarized lasing. This work provides insight into the carrier spin dynamics in perovskites, which pave the way for the rational design of perovskites as powerful spintronic materials.

Methods

Materials

Methylamine bromine (MABr, 99.5%) and Lead (II) bromine (PbBr2, 99.5%) were purchased from Xi’an Polymer Light Technology Corporation.; Manganese (II) bromine (MnBr2, 98 + %), N, N-anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF, 99.9%), dichloromethane (CH2Cl2, 99.9%) and Toluene (TL, 99.9%) were purchased from Innochem Science & Technology (Beijing, China). All chemicals were used as received without further treatment.

Preparation of MAPbBr3 and Mn-MAPbBr3 perovskite microcrystals

A DMF solution of 0.1 M PbBr2 and 0.1 M MABr (equivalent to 0.1 M MAPbBr3) and a DMF solution of 0.02 M MnBr2 were prepared at room temperature. Then, different volumes of MnBr2 solution were added into the MAPbBr3 solution. 10 μL MAPbBr3 or Mn-MAPbBr3 solution was dropped onto a glass substrate supported by a Teflon stage in a beaker containing a mixture of CH2Cl2 and TL with a mass fraction ratio of 10:1 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The CH2Cl2 and TL vapor induced nucleation and subsequent growth of MAPbBr3 or Mn-MAPbBr3 perovskite crystals. After 12 h of growth, large-scale square microcrystals of MAPbBr3 or Mn-MAPbBr3 perovskites were obtained on the glass substrate.

Morphology, component, and structure characterizations

The morphology of perovskite microcrystals was characterized by a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi, S-4800). The components of perovskite microcrystals were measured through Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) on Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL, 2100 F) and X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, ESCALAB 250XI). The crystal structure of perovskites was examined through selected-area electron diffraction (SAED, JEOL, JEM-2100) and X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku, D/max-2500). The Mn doping concentrations were measured by inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) on a Shimadu ICPE-9000. The EDS and SAED were carried out on individual perovskite microcrystals, while the XRD and XPS were performed on ensembles of large-scale perovskite microcrystals.

Optical characterizations

The absorption spectra were measured on a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Hitachi UH4150). PL microscopy images were acquired using an optical microscope (Olympus BX51). Femtosecond transient absorption (TA) chracterizations were carried out using a commercial ultrafast TA spectroscopy system (Harpia-TA, Light Conversion) (Supplementary Fig. 4) and a micro-area TA spectroscopy system (Supplementary Fig. 18). Optically pumped lasing measurements were carried out by a micro-photoluminescence measurement system equipped with a femtosecond laser (Spectra Physics), an optical microscope (Olympus BX51), a charge-coupled device camera (Princeton Instruments), and a spectrophotometer (Princeton Instruments) (Supplementary Fig. 20). The optically pumped lasing measurement was carried out on individual perovskite microcrystals, while the UV–Vis absorption and TA were performed on ensembles of large-scale perovskite microcrystals.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main article and the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Lindemann, M. et al. Ultrafast spin-lasers. Nature 568, 212–215 (2019).

Basu, D., Saha, D. & Bhattacharya, P. Optical polarization modulation and gain anisotropy in an electrically injected spin laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 093904 (2009).

Chen, J. Y., Wong, T. M., Chang, C. W., Dong, C. Y. & Chen, Y. F. Self-polarized spin-nanolasers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 845–850 (2014).

Duan, X. et al. Valley-addressable monolayer lasing through spin-controlled Berry phase photonic cavities. Science 381, 1429–1432 (2023).

Holub, M., Shin, J., Saha, D. & Bhattacharya, P. Electrical spin injection and threshold reduction in a semiconductor laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146603 (2007).

Faria Junior, P. E. et al. Toward high-frequency operation of spin lasers. Phys. Rev. B 92, 075311 (2015).

Yokota, N., Nisaka, K., Yasaka, H. & Ikeda, K. Spin polarization modulation for high-speed vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 113, 171102 (2018).

Wang, L., Yin, L., Zhang, W., Zhu, X. & Fujiki, M. Circularly polarized light with sense and wavelengths to regulate azobenzene supramolecular chirality in optofluidic medium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13218–13226 (2017).

Maguid, E. et al. Photonic spin-controlled multifunctional shared-aperture antenna array. Science 352, 1202–1206 (2016).

Wan, L., Liu, Y., Fuchter, M. J. & Yan, B. Anomalous circularly polarized light emission in organic light-emitting diodes caused by orbital–momentum locking. Nat. Photonics 17, 193–199 (2023).

Lodahl, P. et al. Chiral quantum optics. Nature 541, 473–480 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. Multidimensional nanoscopic chiroptics. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 113–124 (2022).

Hirohata, A. et al. Review on spintronics: principles and device applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 509, 166711 (2020).

Schaibley, J. R. et al. Valleytronics in 2D materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16055 (2016).

Frougier, J. et al. Control of light polarization using optically spin-injected vertical external cavity surface emitting lasers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 252402 (2013).

Iba, S., Koh, S., Ikeda, K. & Kawaguchi, H. Room temperature circularly polarized lasing in an optically spin injected vertical-cavity surface-emitting laser with (110) GaAs quantum wells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 081113 (2011).

Hsu, F.-K., Xie, W., Lee, Y.-S., Lin, S.-D. & Lai, C.-W. Ultrafast spin-polarized lasing in a highly photoexcited semiconductor microcavity at room temperature. Phys. Rev. B 91, 195312 (2015).

Holub, M. & Bhattacharya, P. Spin-polarized light-emitting diodes and lasers. J. Phys. D. 40, R179–R203 (2007).

Giovanni, D. et al. Highly spin-polarized carrier dynamics and ultra large photoinduced magnetization in CH3NH3Pbl3 perovskite thin films. Nano Lett. 15, 1553–1558 (2015).

Long, G. K. et al. Spin control in reduced-dimensional chiral perovskites. Nat. Photonics 12, 528–534 (2018).

Odenthal, P. et al. Spin-polarized exciton quantum beating in hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites. Nat. Phys. 13, 894–899 (2017).

Zhai, Y. et al. Giant Rashba splitting in 2D organic-inorganic halide perovskites measured by transient spectroscopies. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700704 (2017).

Lafalce, E. et al. Rashba splitting in organic-inorganic lead-halide perovskites revealed through two-photon absorption spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 13, 483 (2022).

Niesner, D. et al. Giant Rashba splitting in CH3NH3PbBr3 organic-inorganic perovskite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 126401 (2016).

Xing, G. et al. Low-temperature solution-processed wavelength-tunable perovskites for lasing. Nat. Mater. 13, 476–480 (2014).

Zhu, H. et al. Lead halide perovskite nanowire lasers with low lasing thresholds and high quality factors. Nat. Mater. 14, 636–642 (2015).

Liao, Q. et al. Perovskite microdisk microlasers self-assembled from solution. Adv. Mater. 27, 3405–3410 (2015).

Dong, H., Zhang, C., Liu, X., Yao, J. & Zhao, Y. S. Materials chemistry and engineering in metal halide perovskite lasers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 951–982 (2020).

Wang, K. et al. Wettability-guided screen printing of perovskite microlaser arrays for current-driven displays. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001999 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Exciton chirality transfer empowers self-triggered spin-polarized amplified spontaneous emission from 1D-anchoring-3D perovskites. Adv. Mater. 35, 2305260 (2023).

Tang, B. et al. Evaluating lead halide perovskite nanocrystals as a spin laser gain medium. Nano Lett. 22, 658–664 (2022).

Li, Y., Luo, X., Liu, Y., Lu, X. & Wu, K. Size- and composition-dependent exciton spin relaxation in lead halide perovskite quantum dots. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 1701–1708 (2020).

Zhou, M., Sarmiento, J. S., Fei, C., Zhang, X. & Wang, H. Effect of composition on the spin relaxation of lead halide perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 1502–1507 (2020).

Cheng, H. et al. Dopant-induced slow spin relaxation in CsPbBr3 perovskite nanocrystals. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 4325–4332 (2022).

Liang, W. et al. Efficient optical orientation and slow spin relaxation in lead-free CsSnBr3 perovskite nanocrystals. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 1670–1676 (2021).

Dyakonov, M. & Perel, V. I. Optical orientation in a system of electrons and lattice nuclei in semiconductors. Theory J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 65, 362–375 (1973).

Bir, G. L., Aronov, A. G. & Pikus, G. E. Spin relaxation of electrons scattered by holes. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 69, 1382–1397 (1975).

Giovanni, D. et al. Ultrafast long-range spin-funneling in solution-processed Ruddlesden-Popper halide perovskites. Nat. Commun. 10, 3456 (2019).

Tao, W., Zhou, Q. & Zhu, H. Dynamic polaronic screening for anomalous exciton spin relaxation in two-dimensional lead halide perovskites. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb7132 (2020).

Zhao, W. et al. Transient circular dichroism and exciton spin dynamics in all-inorganic halide perovskites. Nat. Commun. 11, 5665 (2020).

Wei, Q. et al. Effect of zinc-doping on the reduction of the hot-carrier cooling rate in halide perovskites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 10957–10963 (2021).

Sun, Q. et al. Excitation-dependent emission color tuning from an individual Mn-doped perovskite microcrystal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 20089–20096 (2019).

Nayak, P. K. et al. Impact of Bi3+ heterovalent doping in organic–inorganic metal halide perovskite crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 574–577 (2018).

Wu, K., Du, Y., Tang, H., Chen, Z. & Lian, T. Efficient extraction of trapped holes from colloidal CdS nanorods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 10224–10230 (2015).

Wang, C. et al. Phase regulation strategy of perovskite nanocrystals from 1D orthomorphic NH4PbI3 to 3D cubic (NH4)0.5Cs0.5Pb(I0.5Br0.5)3 phase enhances photoluminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 11642–11646 (2019).

Wang, S. et al. Ultrafast dopant-induced exciton auger-like recombination in Mn-doped perovskite nanocrystals. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 328–334 (2020).

Wu, K. et al. Ultrafast interfacial electron and hole transfer from CsPbBr3 perovskite quantum dots. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 12792–12795 (2015).

Wu, Z. et al. Hole-acceptor-manipulated electron spin dynamics in CdSe colloidal quantum dots. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 2126–2132 (2021).

He, J., Zhong, H. & Scholes, G. D. Electron-hole overlap dictates the hole spin relaxation rate in nanocrystal heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 046601 (2010).

Wang, C., Ma, L., Wang, S. & Zhao, G. Efficient photoluminescence of manganese-doped two-dimensional chiral alloyed perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 12129–12134 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. Mn2+-doped lead halide perovskite nanocrystals with dual-color emission controlled by halide content. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 14954–14961 (2016).

Zhang, Q. et al. High-quality whispering-gallery-mode lasing from cesium lead halide perovskite nanoplatelets. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 6238–6245 (2016).

Dong, H. et al. Organic microcrystal vibronic lasers with full-spectrum tunable output beyond the Franck-Condon principle. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 3108–3112 (2018).

Zhou, Z. et al. Experimentally observed reverse intersystem crossing-boosted lasing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 21677–21682 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. High-quality in-plane aligned CsPbX3 perovskite nanowire lasers with composition-dependent strong exciton–photon coupling. ACS Nano 12, 6170–6178 (2018).

Liu, D. et al. Organic laser molecule with high mobility, high photoluminescence quantum yield, and deep-blue lasing characteristics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 6332–6339 (2020).

Fan, F., Turkdogan, S., Liu, Z., Shelhammer, D. & Ning, C. Z. A monolithic white laser. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 796–803 (2015).

Zhan, X. Q. et al. 3D laser displays based on circularly polarized lasing from cholesteric liquid crystal arrays. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104418 (2021).

Liu, Z. F. et al. Circularly polarized laser emission from homochiral superstructures based on achiral molecules with conformal flexibility. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202214211 (2022).

Zhang, K. et al. Room-temperature magnetic field effect on excitonic photoluminescence in perovskite nanocrystals. Adv. Mater. 33, 2008225 (2021).

Rice, W. D. et al. Revealing giant internal magnetic fields due to spin fluctuations in magnetically doped colloidal nanocrystals. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 137–142 (2016).

Bussian, D. A. et al. Tunable magnetic exchange interactions in manganese-doped inverted core-shell ZnSe-CdSe nanocrystals. Nat. Mater. 8, 35–40 (2009).

Pandey, A. et al. Long-lived photoinduced magnetization in copper-doped ZnSe-CdSe core-shell nanocrystals. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 792–797 (2012).

Yu, J. H. et al. Giant Zeeman splitting in nucleation-controlled doped CdSe:Mn2+ quantum nanoribbons. Nat. Mater. 9, 47–53 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported financially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 22090023, 22375207, 22103091, U2032112, and U2230203), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant No. 2022YFA1204403) the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB0520203), and the New Cornerstone Science Foundation through the XPLORER Prize.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S.Z. conceived the original concept. H.D. and Y.S.Z. supervised the project. P.L. and Z.Z. designed and synthesized the materials. P.L., Z.Z., T.Z., H.L., and Z.J. performed the optical measurements. G.R., W.Z., and Y.Y. performed the transient absorption characterizations. P.L., Z.Z., G.R., J.Y., H.D., and Y.S.Z. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, P., Zhou, Z., Ran, G. et al. Spin-polarized lasing in manganese doped perovskite microcrystals. Nat Commun 15, 10880 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55234-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55234-6