Abstract

Iron alloys, including steels and magnetic functional materials, are widely used in capital construction, manufacturing, electromagnetic technology, etc. However, they face the long-standing challenge of high coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE), limiting the applications in high-precision fields. This work proposes a strategy involving the in-situ formation of a nano-scale lamellar/labyrinthine negative thermal expansion (NTE) phase within the iron matrix to tackle this problem. For example, a model alloy, Fe-Zr10-Nb6, was synthesized and its CTE is reduced to approximately half of the iron matrix. Meanwhile, the alloy possesses a strength-plasticity combination of 1.5 GPa (compressive strength) and 17.5% (ultimate strain), which outperforms other low thermal expansion (LTE) metallic materials. The magnetovolume effect of the NTE phase is deemed to counteract the positive thermal expansion in iron. The high stress-carrying hard NTE phase and the tough matrix synergistically contribute to the high mechanical properties. The interaction between the slip of lamellar microstructure and the slip-hindering of labyrinthine microstructure further enhances the strength-plasticity combination. This work shows the promise of offering a method to produce LTE iron alloys with high mechanical properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery and widespread utilization of iron, particularly in the form of iron alloys, have exerted a profound influence on industrialization, modernization, as well as advancements in science and technology. Represented by steels1, their excellent mechanical properties and complete industry make them the foremost structural materials. Meanwhile, the strong magnetism of the Fe element spawns essential magnetic functional materials such as soft magnets2. However, iron alloys confront a long-standing challenge of high thermal expansion, whether employed as structural or functional materials. Specifically, iron has a coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) of about 12 ppm/K, which restricts its advanced applications that demand low dimension-temperature sensitivity and low thermal mismatches when assembled with different materials.

Owing to the inherently weak metallic bonds, viable strategies for directly reducing the CTE in iron alloys are limited. Generally, low thermal expansion (LTE) or even negative thermal expansion (NTE) can be found in intermetallic compounds or solid solution alloys3,4,5,6,7,8,9. However, achieving LTE and maintaining good mechanical properties in these metal-based compounds cannot be achieved simultaneously. For instance, despite the renown of the Invar alloy10,11, celebrated with a Nobel Prize in 1920 for its zero thermal expansion (ZTE) characteristics, its mechanical strength is deficient, with a mere yield strength of 275 MPa. Some intermetallic compounds with ZTE or NTE cannot be processed due to their brittleness, such as Hf0.87Ta0.13Fe212, La(Fe,Si,Co)1313, and MnCoGe14. Metal matrix composites (MMCs) using these NTE compounds as reinforcements are considered effective in reducing CTE15,16,17. But conventional methods to form MMCs such as powder metallurgy inevitably result in weak interface bonding. Additionally, the CTE mismatch between NTE compounds and the metal matrix introduces obvious residual stresses at the interface, further exacerbating the mechanical properties of the MMCs. Recently, the non-stoichiometric approach in NTE compounds, exemplified by, ErxFe10V1.7Mo0.318, LaFe10.2+xCo1.2Si1.619, and Er2Fe14+xB1+0.07x20, have boosted material strength, but it is found ineffective in enhancing toughness. Thus, current solutions for reducing the CTE and achieving high mechanical properties of iron alloys are still confronted with problems that necessitate further attention.

In this work, a strategy is presented to balance the thermal expansion and mechanical properties. A series of alloy compositions are designed and demonstrated to show a nano-scale microstructure and an efficient reduction in CTE while maintaining reliable mechanical properties. For example, in Fe-Zr10-Nb6 alloy, it exhibits an isotropic LTE as well as a combination of high compressive stress and moderate ultimate strain. To delve deeper into the LTE mechanism and the advantages in mechanical properties, a detailed investigation is conducted using neutron powder diffraction (NPD), scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), in-situ neutron diffraction under different temperatures and engineering stress, Mössbauer spectra, and micromechanical experiments. It is evident that the NTE phase counteracts the positive thermal expansion (PTE) of the matrix by the magnetovolume effect (MVE), and the mechanical properties are facilitated by the distinctive microstructures. Such a strategy not only contributes to a reduction in CTE but also provides atomic-scale high-strength interfacial bonding, coupled with its simple synthesis procedure and cost-effectiveness, which has led to a edge among the presently reported iron-based LTE materials.

Results and discussion

As the primary constituent of iron alloys, Fe serves not only as a solvent but also as a precursor for forming second phases. Generally, transition metal elements with larger atomic radii exhibit low solubility in iron, and frequently engage with iron in a ratio of 1:2, resulting in Laves-type AFe2 (A = transition metal elements) compounds. Intriguingly, Laves-type AFe2 compounds occasionally exhibit excellent NTE21 performance due to their complex magnetism and novel Kagome lattice22. This implies it is feasible to in-suit form the Laves-type NTE phase by introducing a trace amount of transition metal elements into iron alloys. Concurrently, the dispersion of the second phase typically results in the strengthening of the alloy23. Such a strategy not only holds the prospect of reducing CTE but also presents the opportunity to achieve high mechanical properties. As shown in the schematic in Fig. 1a, the alloy design strategy involves the utilization of Laves-type NTE compounds to compensate for the PTE in iron alloys. A series of alloy compositions were designed in Fe-Zr-Nb, Fe-Hf-Nb, Fe-Hf-Ta, Fe-Hf-Ti, and Fe-Ti-Sc systems to in-situ form the specific NTE phase. Taking the Fe-Zr-Nb system as a case study, we synthesized samples with nominal compositions of Fe-Zr6-Nb4, Fe-Zr10-Nb6, and Fe-Zr14-Nb8, referred to as Z1, Z2, and Z3, respectively.

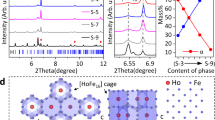

a Schematic diagram of the alloy design strategy. The PTE and NTE represent the PTE phase (iron alloys) and NTE phase (negative thermal expansion compounds) respectively. The MVE represents the magnetovolume effect. b NPD refinement results of Z2 at 300 K. c Crystal structures of the PTE and NTE phases. d SEM images and IPF of Z2 in the longitudinal-transverse (LD-TD) and transverse-normal (TD-ND) planes. e EDS elements mapping under HRTEM. f, g HAADF-STEM image of PTE phase (f) along [110] zone axis and NTE phase (g) along [001] zone axis. The insets show the corresponding SAED patterns. h HAADF-STEM image at the phase boundary. The inset shows the corresponding FFT profile. The schematic diagram shows the semi-coherent relationship of the interface, yellow balls represent Fe atoms, purple/green balls represent Zr/Nb atoms, and the “⊥” represents dislocations. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Crystal structure and microstructure

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns (Supplementary Fig. 1) of alloys with different compositions show that all alloys exhibit a dual-phase structure of a body-centered cubic (BCC) phase and a C14-type Laves phase. The detailed crystal structures of Z1-Z3 were determined by NPD (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1). The NPD pattern and refined results of Z2 are depicted in Fig. 1b, revealing the presence of the dual-phase structure: a C14-type Laves phase (P63/mmc, labeled as NTE phase) with the composition of (Zr0.62Nb0.27Fe0.11)Fe2, and a BCC α-Fe phase (Im-3m, labeled as PTE phase). The NTE phase formed herein exhibits a hexagonal structure, rather than the cubic structure as reported in the (Zr,Nb)Fe2 compounds with NTE behavior24,25,26. A minor fraction of Fe is found to substitute Zr/Nb in the 4f Wyckoff site within the NTE phase, as the crystal structures of these two phases are shown in Fig. 1c. This antisite of Fe atoms in the NTE phase is significant for its thermal expansion behavior.

Off-axis transmission Kikuchi diffraction (TKD) on both longitudinal-transverse (LD-TD) and transverse-normal (TD-ND) planes of Z2 (Supplementary Fig. 3) was employed to characterize the spatial distribution and orientation relationship of the two phases. The two phases show nano-scale microstructures on both observational planes, suggesting their spatial uniformity (Fig. 1d). All alloys exhibit lamellar/labyrinthine arrangements of two phases (Supplementary Fig. 4), exemplifying the typical characteristics of eutectic alloys. The thermogravimetric-differential thermal analysis curves (Supplementary Fig. 5) of alloys further demonstrated the eutectic reaction above 1500 K. For instance, a sequence of transitions from hypo-eutectic to eutectic to hyper-eutectic microstructures is observed in Z1-Z3 (Supplementary Fig. 6). From the corresponding inverse pole figures (IPF) (Fig. 1d), the crystal orientation of the PTE phase is relatively random, whereas the NTE phase is textured. The energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) element mapping results obtained using a high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) for Z2 indicate an alternating arrangement of Zr/Nb-enriched regions and Fe-enriched regions without elemental segregation (Fig. 1e). Of paramount significance is the discovery of such a naturally formed nano-scale microstructure within LTE alloys. Especially, this microstructure exhibits a grain refinement effect and synergistic behavior between two phases, endowing it with potential for high strength27 and wear-resistant28 applications.

High-angle angular dark field-scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) was employed to collect atomic-resolution images of Z2. The HAADF-STEM images and the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns of the NTE and PTE phases (Fig. 1f, g) correspond entirely to the crystal structures (Fig. 1c). Additionally, the EDS analysis offers indirect evidence for the antisite of Fe atoms (Supplementary Fig. 7, Supplementary Table 2). The HAADF-STEM image at the phase boundary and the fast Fourier transform (FFT) analysis indicate an ordered interfacial match with a quite small lattice mismatch (δ = 3.01%) between the (1\(\bar{1}\)0)PTE and (112)NTE planes (Fig. 1h). The inverse FFT (IFFT) profile shown in Supplementary Fig. 8d demonstrated a semi-coherent relationship at phase boundary. The lattices of the two phases match as schematic illustrated in Fig. 1h, while mismatch is accommodated through dislocations and a tilted interface (Supplementary Fig. 8). Such interfaces distinguish themselves from conventional disordered interfaces in MMCs, bearing lower interfacial energy and reducing the risk of failure caused by stress concentration (Supplementary Discussion 1). The nano-scale microstructures coupled with ordered interfaces provide alloys with favorable assurances under thermal cycle and mechanical loading conditions.

Thermal expansion properties

The successful formation of NTE phases establishes a foundation for achieving LTE in iron alloys. Figure 2a shows the linear CTE (αl) of Z1-Z3 and pure iron. It can be seen Z1-Z3 each manifest LTE. In the case of Z2, its αl is measured as 5.5 ppm/K (110 to 325 K), nearly 53% lower than that of the iron matrix. With increasing content of Zr/Nb, the αl continues to decrease, underscoring the efficacy of this strategy in reducing CTE. All alloy compositions that form the specific NTE phase exhibit reduced CTE compared with the iron matrix (Supplementary Fig. 9). As depicted in Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 3, a comprehensive comparison of the linear CTE is performed between the alloys in this work and conventional iron alloys (stainless steel, carbon steel, bearing steel, etc.)29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. The results prove that introducing the NTE phase into iron alloys is a potent strategy for reducing their CTE. Meanwhile, the CTE is tunable by controlling the NTE phase content.

a Linear CTE (αl) of Z1-Z3 and pure iron. b Comparison of linear CTE between the alloys mentioned in this work and conventional iron alloys. The gray column represents the decrease in CTE. c Linear CTE (αl) of Z2 measured along different directions (top) and after different times thermal shock cycles (bottom). The LN2 represents the liquid nitrogen. d Temperature dependence of (200)PTE and (220)NTE peaks determined by the NPD of Z2. The PTE and ZTE represent the positive thermal expansion and zero thermal expansion behavior. e Intrinsic unit cell CTE (αV) of the two phases (dash line) and the average volume changes of Z2 determined by ROM (solid line). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Solely exhibiting LTE is insufficient for meeting engineering requirements, isotropic CTE and good thermal cycling stability are also crucial factors to consider. As depicted in Fig. 2c (top), the αl was measured along three directions with approximately the same value, demonstrating it isotropic. From Fig. 2c (bottom) and Supplementary Fig. 10, the αl and the microstructure were largely unaffected after 100 times thermal shock cycles between liquid nitrogen (LN2, 77 K) and hot oil (473 K). This thermal fatigue resistance of the alloys underscores the strong interfacial bonding of the two phases.

Temperature-dependent NPD was conducted to analyze the lattice parameter changes for two phases. Figure 2d illustrates the temperature dependence of the (200)PTE and (220)NTE peaks. With increasing temperature, the (200)PTE peak exhibits a trend of shifting toward lower angles, indicating a PTE behavior of its lattice. In contrast, the (220)NTE peak remains nearly unaltered, indicating its ZTE behavior. The thermal expansion of unit cell volume (αV) is extracted, as shown in Fig. 2e and Supplementary Table 4. The αV is 23.4 ppm/K (5-555 K) for the PTE phase and 6.7 ppm/K (5-455 K) for the NTE phase. Meanwhile, the average αV of Z2 is calculated to be 11.5 ppm/K (5-455 K) by the rule of mixture (ROM). The in-situ formed NTE phase exhibits abnormal ZTE, compensating for the iron matrix’s thermal expansion.

Low thermal expansion mechanism

Following the materials’ design, it can be considered that the abnormal thermal expansion behavior of the NTE phase is related to its magnetism. As the temperature dependence of magnetization (M-T curves) illustrated in Fig. 3a, all alloys exhibit a ferromagnetic (FM) state with high magnetization from 5 K to 800 K. This phenomenon can be attributed to the strong magnetic background of the PTE phase (α-Fe). However, the M-T curves exhibit a change in slope at approximately 470 K, which likely represents the magnetic transition process of the NTE phase. The isothermal magnetization curves (M-H) of Z2 are tested at different temperatures to assist in understanding the magnetic transition (Fig. 3b). The saturation magnetization (Ms) extracted from the M-H curves (inset of Fig. 3b) exhibits a decrease as the temperature rises, reaching a distinct inflection point between 450 K and 500 K. Combining its consistency with the fluctuations observed in the M-T curves, the inflection point at approximately 475 K can be confirmed as the Curie temperature (TC) of the NTE phase within Z2. In light of previous research, the antisite of Fe atoms within the NTE phase usually stabilizes the FM-ordered state and increases TC26,45. In these three samples, where the NTE phase formed in different Fe concentrations, the difference in TC is relatively modest (Fig. 3a). This suggests an upper limit to this antisite. Such a characteristic allows the NTE phase to maintain a stable contraction in alloys with different PTE phase fractions, and it can be considered that the CTE of alloys is only related to the content of the NTE phase.

a Temperature dependence of magnetization (M-T curves) for Z1-Z3. b Isothermal magnetization curves (M-H) of Z2 at different temperatures. The inset shows the temperature dependence of Ms for Z2. c Temperature dependence of the (002) magnetic peak intensity for the NTE phase. The inset shows the magnetic structure of the NTE phase. d Fe57 Mössbauer spectra of Z2 at 6.2 K. e Temperature dependence of ωs, ωnm (dash line), and ωexp (solid line) for the NTE phase. f Linear positive correlation between \({M_{{\rm{NTE}}^2}}\) and ωs for NTE phase. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The magnetic structure of the NTE phase was analyzed using temperature-dependent NPD. As depicted in Fig. 3c, the intensity of the (002) magnetic peak decreases with increasing temperature until 475 K and remains invariant, which suggests a parallel arrangement of FM spin moments in the a-b plane. The inset of Fig. 3c displays the magnetic structure of the NTE phase. The antisite Fe atoms at the 4f Wyckoff site show extra spin moments, as highlighted with a dashed circle. To further investigate the effect of antisite Fe atoms occupation on magnetism, Fe57 Mössbauer spectra of Z2 were collected and fitted (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Table 5). The absorption of α-Fe was first fitted and subtracted from the total spectrum. The remaining signals were well fitted with three sextets representing the interaction between hyperfine fields and spin moment. The present results reveal additional spectra splitting, indicating that Fe atoms at the 4f Wyckoff site possess reliable spin moments. It can be considered collectively that Fe(4f) possesses an ordered moment and introduces extra magnetic exchange interaction, stabilizing the hexagonal FM-order state.

The magnetic contribution on the thermal expansion (i.e., MVE) was quantitatively described using spontaneous volume magnetostriction (ωs)46 (Fig. 3e). Here, ωexp represents experimental thermal expansion, ωnm represents normal thermal expansion, and ωs = ωexp - ωnm. It is evident that the NTE phase lattice expansion with increasing temperature, whereas the MVE counters this trend below TC. This unconventional MVE originates from the distinctive magnetic temperature dependence of the NTE phase. As shown in Fig. 3f, by the Landau theory, the ωs can be regarded as a quadratic function of total magnetic moment (MNTE)47. The pronounced linear correlation between ωs and \({M_{{\rm{NTE}}^2}}\) aptly underscores the dominant role of FM order in MVE. Thus far, an intrinsic mechanism by which the NTE phase reduces the CTE of iron alloys has been revealed. Specifically, this mechanism is rooted in the compensatory action of MVE, which evolves concomitantly with the changes in magnetism. The antisite Fe atoms stabilize the hexagonal FM state, thereby facilitating the occurrence of MVE at higher temperatures.

Mechanical properties and deformation mechanism

To meet the requisites in specific application contexts, the mechanical properties of LTE materials warrant due scrutiny. The compression engineering stress-strain curves of the Z1-Z3 and pure iron are illustrated in Fig. 4a and other alloys are included in Supplementary Fig. 11. All the designed alloys achieve an enhancement in strength compared to pure iron. In the case of Z1-Z3, the plasticity decreases with the increase of Zr/Nb content and Z3 even becomes brittle. Z2 exhibits a strength-plasticity balance characterized by a compressive strength of 1.5 GPa and an ultimate strain of 17.5%. Temperature-dependent tensile tests are conducted to further evaluate the mechanical properties of the alloy (Supplementary Fig. 12). Similar to all reported LTE natural dual-phase alloys and MMCs, current alloys exhibit tensile brittleness at room temperature. However, in terms of compression performance, strength-plasticity combinations in this work far surpass that of LTE metallic materials12,13,14,18,19,20,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58 (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table 6). Furthermore, the plasticity of the alloys enables good machinability as exemplified by the screw support seat (Fig. 4c) machined using computer numerical control (CNC) lathes. The smoothness of the workpiece surface meets the demands for high precision and efficient manufacturing. Meanwhile, compared to the conventional Invar alloy, the material in this work has better comprehensive performance (Supplementary Discussion 2). Such mechanical properties are attributed to the synergy between the two phases as well as the response of the heterogeneous microstructures during loading.

a Compression engineering stress-strain craves of Z1-Z3 and pure iron. b Comparison of compressive strength and ultimate strain between the alloys mentioned in this work and other typical metal-based LTE materials. (Invar is completely plastic, the strength at 25 % strain is used here for comparison.) c Screw support seat machining by CNC, made of Z2. d Lattice strain of two phases versus true strain. The suffixes A and T represent along and perpendicular to the loading direction, respectively. The subscripts PTE and NTE represent the PTE phase and NTE phase, respectively. e Normalized FWHM of two phases’ peaks versus true strain. The error bars represent the standard deviation. f Phase-specific stress of each phase versus true strain. Note the tensile stress is depicted as negative. g, i SEM images of micropillars with different microstructures. The insets show the enlarged microstructures. h, j Micromechanical properties of micropillars in g and i. The insets show the SEM images of corresponding pillars after testing. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Generally, the Laves-type NTE phase exhibits poor mechanical performance attributed to its inherent brittleness. However, a compressive strength higher than the iron matrix has been observed while demonstrating larger plastic deformation from the pure NTE phase. This enhancement can be attributed to the synergy between the two phases. Hereto, in-situ neutron diffraction under compression loading59 was conducted on Z2. The diffraction along the loading direction (labeled as A) and perpendicular to it (labeled as T) were collected (Supplementary Fig. 13). As the lattice strain of two phases versus the true strain shown in Fig. 4d, the two phases exhibited disparity deformation behaviors. The process can be divided into three stages: stage I, co-elastic; stage II, the PTE phase yields while the NTE phase retains elastic; and stage III, co-plastic. Figure 4e reveals the normalized full width at half maximum (FWHM) of peaks versus true strain. The FWHM of (110)PTE peaks exhibits a slow increase, corresponding to uniform deformation in the PTE phase. Conversely, the FWHM of (103)NTE peaks displays a pronounced increase starting from stage II, indicating instability and possibly stress concentration in the NTE phase. In stage III, the increase slows down, but notable errors are observed, indicating the strain is released as shear or microcracks. The microstructure provides tolerance to shear bands and microcrack within alloys, with tough phases at crack tips featuring high-density dislocation walls and stronger stress fields, thereby retarding crack propagation across both phases60.

To further elucidate this synergy, the phase-specific stress of each phase is calculated (Fig. 4f). Due to the ZTE behavior of the NTE phase below TC (475 K), a disparity in CTE between the two phases arises, and the thermal mismatch residual stress introduced during preparation is also taken into account. As shown in the temperature dependence of residual stress (Supplementary Fig. 14), the calculated internal stress is 384 MPa at 280 K. The PTE phase with a larger volume contracting bears tensile stress, whereas the NTE phase bears compressive stress. During stage I, the PTE phase demonstrates a rapid increase in carried stress, whereas the NTE phase shows a slower increase, indicating that the PTE phase bears more load. In stage II, while the PTE phase yields, the NTE phase begins to rapidly harden to carry more stress and reaches nearly 2 GPa. In stage III, the PTE phase continues to soften while the NTE phase shows small hardening with increasing stress. The low yield strength and high plasticity of the PTE phase provide deformability while hindering the propagation of cracks and slides in the NTE phase. In turn, the NTE phase contributes to a higher stress-carrying ability of the alloy61. Such a synergy between the tough and hard phases greatly benefits the balance of strength and plasticity.

As is well known, materials with heterogeneous microstructures usually exhibit complex mechanical behavior62,63. Thus, compressive micromechanical experiments of micropillars were conducted to reveal the deformation mechanism of alloys. As depicted in Fig. 4g and h, when the lamellar layers of the micropillar are perpendicular to the loading direction, the material yields at 0.8 GPa and reveals slip events along phase boundaries (Supplementary Movie 1), manifesting as instabilities in the stress-strain curve (Fig. 4h) at approximately 14% strain. This indicates that the failure initiates with relative slip along the phase boundaries. The experiment with the lamellar layers tilted toward the loading direction further corroborated this observation (Supplementary Fig. 15, Supplementary Movie 2). In addition, a micropillar with labyrinthine microstructure embedded in the tilted lamellar microstructure is prepared, as shown in Fig. 4i. Interestingly, Fig. 4j and Supplementary Movie 3 reveal the absence of stress instabilities in this micropillar, and no catastrophic sliding is observed in the insert of Fig. 4j. Instead, the slip band terminates near the labyrinthine microstructure. This observation suggests an interaction between the two types of microstructures, with lamellar slip enhancing the deformation capacity and the labyrinthine microstructure hindering slip propagation across the entire grain, thus delaying premature material failure. It can be believed that the interaction between naturally formed heterogeneous microstructures further enhances the mechanical properties of alloys.

In summary, a method for reducing thermal expansion and achieving high mechanical properties in iron alloys has been demonstrated through the in-situ formation of Laves-type NTE phases. The analysis of the NPD and Mössbauer spectra reveals that the NTE phase readily induces the antisite of Fe atoms at 4f Wyckoff site, which stabilizes the hexagonal FM state, engenders evident ZTE, and mitigates the PTE exhibited by the iron matrix. The heterogeneous microstructure and semi-coherent phase boundaries improve alloys’ thermal cycling stability. The micromechanical behaviors highlight the synergistic effect of the NTE phase and the PTE phase, as well as the cooperative influence of lamellar and labyrinthine microstructures, which contribute to the strength-plasticity combination. This strategy enables these alloys to satisfy stringent requirements for LTE and reduce thermal expansion mismatch with other inorganic non-metallic materials, such as silicon and glass. Moreover, the simple preparation of no need for heat treatment, and low-cost formulation without rare earths or noble metals, combined with high machinability, broadens the scope for potential applications (Supplementary Discussion 3) of these alloys in wide engineering areas such as aerospace and optical systems.

Methods

Material preparation

All bulk alloys are prepared by arc-melting under an Ar atmosphere with the starting materials of high-purity elements (>99.95 wt%). Re-melting is performed four times to promote chemical homogeneity, and water-cooled copper mold casting is used to form the alloy ingot with dimensions of 10×10×60 mm.

Structural characterization

The phase and crystal structural at room temperature are identified by XRD using an X-ray diffractometer (SmartLab 9 kw, Rigaku Corporation) performed with Co Kα radiation and NPD at General Purpose Powder Diffractometer, China Spallation Neutron Source. The nano-scale dual-phase microstructures of the alloys are obtained under SEM (Zeiss GeminiSEM500), in the form of backscattered electrons images and off-axis TKD images. High-resolution and atomic-resolution images of the alloys are characterized by HRTEM (FEI Tecnai G2 F30) and HAADF-STEM (ThermoFisher Themis Z), both equipped with an EDS. The lattice mismatch (δ) is calculated by the following formula:

Where d represents the interplanar spacing, obtained through refinement results of NPD at room temperature.

Thermal expansion behavior

The linear CTE curves are collected using a thermal dilatometer (NETZSCH, DIL 402 Expedis Select) with ~Ф5×10 mm cylindrical samples. The temperature-dependent NPD is carried out at the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organization (ANSTO), and the temperature dependence of the lattice parameters is obtained by refining the diffraction data using the Rietveld method.

Mechanical properties

The engineering stress-strain curves under compressive loading are measured using an electronic universal testing machine (WDW-200D) with Ф4×10 mm cylindrical samples, and the strain rate is controlled at 1×10−3 s−1.

Magnetic properties

The magnetic properties are measured using a physical property measurement system (Quantum Design) equipped with a vibrating sample magnetometer.

Mössbauer spectroscopy

The Mössbauer spectroscopy measurements are performed at 6.2 K with a low-temperature 57Fe Mössbauer spectrometer (WissEl, WSS-10), in which the α-Fe is used for reference and 57Co (Rh) is used as the radiation source.

In-situ neutron diffraction under compression loading

The in-situ neutron diffraction measurements under compression loading are carried out at VULCAN, Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), using Ф8×16 mm cylindrical samples. The lattice strain of the specific crystal plane is calculated by interplanar spacing, which is obtained from real-time diffraction data after a single peak fitting64. The calculation formula is as follows:

where εhkl is the hkl-orientation lattice strain, dhkl and d0, hkl are the hkl-orientation interplanar spacings measured during and before deformation, respectively.

Thermal residual stress and phase-specific stress calculations

The thermal residual stress (σr) between NTE and PTE phases is calculated by formula65:

where E, V, and α represent the Young’s modules, volume fraction, and CTE, respectively. To and Tp denote the operating and processing temperatures of alloys, respectively. In this work, To represent the environment temperature (~280 K), and Tp represents the TC of the NTE phase.

The phase-specific stress of the PTE phase (σPTE) is calculated by formula60:

where EPTE, νPTE, and εPTE denote the elastic modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and lattice strain, respectively. The subscripts “11”, “22”, and “33” refer to specific directions of lattice strain, with “11” representing the axial direction, while “22” and “33” denote the transverse directions. Additionally, it is assumed that ε22 is equal to ε33. Due to possible modulus anomalies in the NTE phase, the phase stress of the NTE phase (σNTE) is simply calculated by formula60:

Micromechanical experiments

The samples with a thickness of 2 mm are first ground and finely polished. The cylindrical micropillars are milled from the surface of the samples using a 30 keV Ga+ focused ion beam (FIB, Tescan Lyra FIB workstation). Rough pillars with a diameter of 10 μm and height of 3 μm are first fast-milled under ion beam conditions of 4.5 nA. After that, the pillars are finely polished step by step by reducing the current to 1 nA, 240 pA, and 50 pA until they reach an aspect ratio (height/diameter) of ~2 with diameters of ~3 μm and heights of ~6 μm. Micropillar compression tests are carried out with an in-situ indenter system (Alemnis AG) inside an SEM (Philips XL30) at room temperature. A 5 μm diameter diamond flat punch (Synton MDP, Switzerland) is applied to load and unload on the pillars with a displacement rate of 6 nm s−1, corresponding to a strain rate of 1×10−3 s−1. The microstructures of the micropillars before and after compression are characterized using SEM in the same workstation with FIB.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Jiang, S. et al. Ultrastrong steel via minimal lattice misfit and high-density nanoprecipitation. Nature 544, 460–464 (2017).

Han, L. et al. A mechanically strong and ductile soft magnet with extremely low coercivity. Nature 608, 310–316 (2022).

Chen, J., Hu, L., Deng, J. & Xing, X. Negative thermal expansion in functional materials: controllable thermal expansion by chemical modifications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 3522–3567 (2015).

Song, Y., Shi, N., Deng, S., Xing, X. & Chen, J. Negative thermal expansion in magnetic materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 121, 100835 (2021).

Belo, J. H., et al. Giant negative thermal expansion at the nanoscale in the multifunctional material Gd5(Si, Ge)4. Phys. Rev. B 100, 134303 (2019).

Long, F., Song, Y. & Chen, J. La (Fe,Si/Al)13-based materials with exceptional magnetic functionalities: a review. Microstructures 4, 2024011 (2024).

Atuchin, V. V. et al. Negative thermal expansion and electronic structure variation of chalcopyrite type LiGaTe2. RSC Adv. 8, 9946–9955 (2018).

Li, Q., Onuki, Y. & Sun, Q. Tailoring thermal expansion of shape memory alloys through designed reorientation deformation. Acta Mater. 218, 117201 (2021).

Xu, M. et al. Giant uniaxial negative thermal expansion in FeZr2 alloy over a wide temperature range. Nat. Commun. 14, 4439 (2023).

Guillaume, C. É. Recherches sur les aciers au nickel. J. Phys. Theor. Appl. 7, 262–274 (1898).

van Schilfgaarde, M., Abrikosov, I. A. & Johansson, B. Origin of the Invar effect in iron–nickel alloys. Nature 400, 46–49 (1999).

Li, L. F. et al. Good comprehensive performance of Laves phase Hf1-xTaxFe2 as negative thermal expansion materials. Acta Mater. 161, 258–265 (2018).

Huang, R. et al. Giant negative thermal expansion in NaZn13-type La(Fe, Si, Co)13 compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11469–11472 (2013).

Zhao, Y.-Y. et al. Giant negative thermal expansion in bonded MnCoGe-based compounds with Ni2In-type hexagonal structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 1746–1749 (2015).

Zhou, C. et al. Near-zero thermal expansion of ZrW2O8/Al-Si composites with three dimensional interpenetrating network structure. Compos. B Eng. 211, 108678 (2021).

Yuan, X. et al. Design of negative/nearly zero thermal expansion behavior over a wide temperature range by multi-phase composite. Mater. Des. 203, 109591 (2021).

Takenaka, K. Negative thermal expansion materials: technological key for control of thermal expansion. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 13, 013001 (2016).

Lin, K. et al. High performance and low thermal expansion in Er-Fe-V-Mo dual-phase alloys. Acta Mater. 198, 271–280 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Balancing negative and positive thermal expansion effect in dual-phase La(Fe,Si)13/α-Fe in-situ composite with improved compressive strength. J. Alloy. Compd. 769, 233–238 (2018).

Yu, C. et al. Superior zero thermal expansion dual-phase alloy via boron-migration mediated solid-state reaction. Nat. Commun. 14, 3135 (2023).

Shiga, M., Muraoka, Y. & Nakamura, Y. Invar effects of Laves phase intermetallic compounds. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 10, 280–287 (1979).

Xu, J. et al. Significant zero thermal expansion via enhanced magnetoelastic coupling in Kagome magnets. Adv. Mater. 35, e2208635 (2022).

Kim, S.-H., Kim, H. & Kim, N. J. Brittle intermetallic compound makes ultrastrong low-density steel with large ductility. Nature 518, 77–79 (2015).

Shiga, M. Invar effects in Zr0.7Nb0.3Fe2. Phys. Lett. A 53, 319–320 (1975).

Song, Y. et al. Transforming thermal expansion from positive to negative: the case of cubic magnetic compounds of (Zr,Nb)Fe2. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 1954–1961 (2020).

Sun, Y. et al. Interplanar ferromagnetism enhanced ultrawide zero thermal expansion in Kagome cubic intermetallic (Zr,Nb)Fe2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 17096–17102 (2023).

Shi, P. et al. Enhanced strength–ductility synergy in ultrafine-grained eutectic high-entropy alloys by inheriting microstructural lamellae. Nat. Commun. 10, 489 (2019).

An, X. L. et al. A new strong pearlitic multi-principal element alloy to withstand wear at elevated temperatures. Acta Mater. 227, 117700 (2022).

Elmer, J., Olson, D. & Matlock, D. Thermal expansion characteristics of stainless steel weld metal. Weld. J. 61, 293 (1982).

Winczek, J. & Kulawik, A. Dilatometric and hardness analysis of C45 steel tempering with different heating-up rates. Metalurgija 51, 9–12 (2012).

Jiang, B. et al. Thermophysical properties of bearing steel GCr15SiMn. Metall. Res. Technol. 112, 301 (2015).

Kwon, Y.-S., Wu, Y., Suri, P. & German, R. M. Simulation of the sintering densification and shrinkage behavior of powder-injection-molded 17-4 PH stainless steel. Met. Mater. Trans. A 35, 257–263 (2004).

Subramanian, R. et al. Thermal expansion characteristics of Fe–9Cr–0.12C–0.56Mn–0.24V–1.38W–0.06Ta (wt%) reduced activation ferritic–martensitic steel. J. Nucl. Mater. 459, 150–158 (2015).

Shi, J. et al. Structural, magnetic and magnetostrictive properties of Fe83Ga17 films with a Ti adhesion layer. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 475, 662–667 (2019).

Thurn, J. & Hughey, M. P. Evaluation of film biaxial modulus and coefficient of thermal expansion from thermoelastic film stress measurements. J. Appl. Phys. 95, 7892–7897 (2004).

Laplanche, G. et al. Temperature dependencies of the elastic moduli and thermal expansion coefficient of an equiatomic, single-phase CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 623, 348–353 (2015).

Kaschnitz, E., Hofer, P. & Funk, W. Thermophysical properties of a hot-work tool-steel with high thermal conductivity. Int. J. Thermophys. 34, 843–850 (2012).

Areitioaurtena, M., Segurajauregi, U., Fisk, M., Cabello, M. J. & Ukar, E. Numerical and experimental investigation of residual stresses during the induction hardening of 42CrMo4 steel. Eur. J. Mech. A Solids 96, 104766 (2022).

Hellström, K., Diaconu, V.-L. & Diószegi, A. Density and thermal expansion coefficients of liquid and austenite phase in lamellar cast iron. China Foundry 17, 127–136 (2020).

Fu, J. X., Li, X. D. & Hwang, W. S. Study of the coefficient of thermal expansion for steel Q235. Adv. Mat. Res. 194-196, 326–330 (2011).

Yakout, M., Elbestawi, M. A. & Veldhuis, S. C. A study of thermal expansion coefficients and microstructure during selective laser melting of Invar 36 and stainless steel 316. L. Addit. Manuf. 24, 405–418 (2018).

Bai, Y., Zhao, C., Zhang, J. & Wang, H. Abnormal thermal expansion behaviour and phase transition of laser powder bed fusion maraging steel with different thermal histories during continuous heating. Addit. Manuf. 53, 102712 (2022).

Dong, F., Qie, J.-M. & Deng, H.-H. Study on thermal physical properties of 304 stainless steel. In 6th international symposium on high-temperature metallurgical processing. 99–104 (2015).

Souder, W. & Hidnert, P. Thermal expansion of a few steels. Ch.4 (Government Printing Office, US, 1922).

Xu, M. et al. High-temperature zero thermal expansion in HfFe2+δ from added ferromagnetic paths. Chem. Mater. 34, 9437–9445 (2022).

Moriya, T. & Usami, K. Magneto-volume effect and invar phenomena in ferromagnetic metals. Solid State Commun. 34, 95–99 (1980).

Sayetat, F., Fertey, P. & Kessler, M. An easy method for the determination of debye temperature from thermal expansion analyses. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 31, 121–127 (1998).

Dan, S., Mukherjee, S., Mazumdar, C. & Ranganathan, R. Zero thermal expansion with high Curie temperature in Ho2Fe16Cr alloy. RSC Adv. 6, 94809–94814 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. Realization of zero thermal expansion in La(Fe,Si)13 -based system with high mechanical stability. Mater. Des. 148, 71–77 (2018).

Song, Y. et al. Zero thermal expansion in magnetic and metallic Tb(Co,Fe)2 intermetallic compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 602–605 (2018).

Song, Y. et al. Opposite thermal expansion in isostructural noncollinear antiferromagnetic compounds of Mn3A (A = Ge and Sn). Chem. Mater. 30, 6236–6241 (2018).

Sun, X. M. et al. Giant negative thermal expansion in Fe-Mn-Ga magnetic shape memory alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 113, 041903 (2018).

Hu, J. et al. Adjustable magnetic phase transition inducing unusual zero thermal expansion in cubic RCo2-based intermetallic compounds (R = rare earth). lnorg. Chem. 58, 5401–5405 (2019).

Li, L. F. et al. Near-zero thermal expansion and high thermal conductivity from ambient to cryogenic temperatures in Hf0.87Ta0.13Fe2Cux. Materialia 9, 100637 (2020).

Cao, Y. et al. Ultrawide temperature range super-Invar behavior of R2(Fe,Co)17 materials (R = rare earth). Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 055501 (2021).

Yu, C. et al. Plastic and low-cost axial zero thermal expansion alloy by a natural dual-phase composite. Nat. Commun. 12, 4701 (2021).

Pang, X. et al. Design of zero thermal expansion and high thermal conductivity in machinable xLFCS/Cu metal matrix composites. Compos. B Eng. 238, 109883 (2022).

Zhou, H. et al. Low-melting metal bonded MM′X/In composite with largely enhanced mechanical property and anisotropic negative thermal expansion. Acta Mater. 229, 117830 (2022).

An, K. et al. First in situ lattice strains measurements under load at VULCAN. Met. Mater. Trans. A 42, 95–99 (2010).

Shi, P. et al. Hierarchical crack buffering triples ductility in eutectic herringbone high-entropy alloys. Science 373, 912–918 (2021).

Yu, D., Bei, H., Chen, Y., George, E. P. & An, K. Phase-specific deformation behavior of a relatively tough NiAl–Cr(Mo) lamellar composite. Scr. Mater. 84-85, 59–62 (2014).

Ding, Z. Y., He, Q. F., Wang, Q. & Yang, Y. Superb strength and high plasticity in laves phase rich eutectic medium-entropy-alloy nanocomposites. Int. J. Plast. 106, 57–72 (2018).

Schwiedrzik, J. et al. In situ micropillar compression reveals superior strength and ductility but an absence of damage in lamellar bone. Nat. Mater. 13, 740–747 (2014).

An, K. VDRIVE- Data Reduction and Interactive Visualization Software for Event Mode Neutron Diffraction. Report No. ORNL-TM-2012-621 (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2012).

Mei, H. Measurement and calculation of thermal residual stress in fiber reinforced ceramic matrix composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 68, 3285–3292 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFE0109100) (J.C.), the Outstanding Young Scientist Program of Beijing Colleges and Universities (JWZQ20240101015) (J.C.), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22275014, 12104038 and 22205016) (Y.S. and C.Z.). A portion of this research used resources at the Spallation Neutron Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility operated by the ORNL. The beam time was allocated to (VULCAN) on proposal number IPTS-29886.1. We acknowledge Dr. Chinwei Wang for collecting the NPD data at the high-intensity diffractometer Wombat of the ANSTO. We acknowledge Prof. Xianran Xing for providing laboratory XRD and macroscopic magnetic tests at the Institute of Solid State Chemistry, University of Science and Technology Beijing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C., Y.S., and H.L. conceived the idea of the work. H.L. and Y.S. designed and carried out the main experiments. Y.Z., K.A., Y.Ch. and D.Y. conducted and analyzed the in-situ neutron diffraction results. C.Z., Y.W., and J.J.S. helped the micromechanical experiments. L.H. and J.H. collected the temperature-dependent NPD data. F.L. helped the magnetic measurement. Y.Y. helped the TEM test. Y.S. and J.C. supervised the project. Z.L. and J.C. provided useful insights on this project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Suhrit Mula and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, H., Zhou, C., Song, Y. et al. A strategy to reduce thermal expansion and achieve higher mechanical properties in iron alloys. Nat Commun 16, 211 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55551-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55551-w

This article is cited by

-

Nanoscale multi-gradient ordered architectures driven exceptional strength and ductility in low thermal expansion magnesium alloy

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Effect of quenching and tempering on microstructure and properties of Super Invar alloy fabricated by laser powder bed fusion for semiconductor equipment

Progress in Additive Manufacturing (2025)

-

Low-frequency phonon driven enhancement of negative thermal expansion in Zn2−xMnxGeO4

Tungsten (2025)

-

Temperature-stable dielectric constant and low thermal expansion in linear low-density polyethylene/copper vanadate composites

Polymer Bulletin (2025)