Abstract

Electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide (CO2) into sustainable fuels and base chemicals requires precise control over and understanding of activity, selectivity and stability descriptors of the electrocatalyst under operation. Identification of the active phase under working conditions, but also deactivation factors after prolonged operation, are of the utmost importance to further improve electrocatalysts for electrochemical CO2 conversion. Here, we present a multiscale in situ investigation of activation and deactivation pathways of oxide-derived copper electrocatalysts under CO2 reduction conditions. Using well-defined Cu2O octahedra and cubes, in situ X-ray scattering experiments track morphological changes at small scattering angles and phase transformations at wide angles, with millisecond to second time resolution and ensemble-scale statistics. We find that undercoordinated active sites promote CO2 reduction products directly after Cu2O to Cu activation, whereas less active planar surface sites evolve over time. These multiscale insights highlight the dynamic and intimate relationship between electrocatalyst structure, surface-adsorbed molecules, and catalytic performance, and our in situ X-ray scattering methodology serves as an additional tool to elucidate the factors that govern electrocatalyst (de)stabilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The electrocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide (CO2) over metallic catalysts depends on the morphological1,2,3 and chemical nature of the catalyst surface4, next to external factors such as electrolyte composition5,6 and local pH7. Cu stands out as electrocatalyst material because of its unique ability to form C–C bonds, for example in multicarbon (C2+) products such as ethylene and ethanol1,2,3. However, the relationship between catalyst structure and performance (stability, selectivity and activity) is still heavily studied and is likely affected by dynamic morphological changes under operational conditions1,2,3. For example, it has been shown that the C2+ hydrocarbon selectivity of Cu electrocatalysts can be tailored on demand through the preparation of well-defined nanoparticles with selectively exposed Cu(100) surface sites, but variations in product distribution are observed under prolonged operation4. Furthermore, recent experimental and theoretical studies have pointed out the potential impact of sub-surface oxygen in oxide-derived electrocatalysts on the production of C2 products8,9,10,11, but again changes in performance are observed over time and attributed to dynamic variations in the electrocatalyst structure. These observations have boosted research into the stability of electrocatalysts12,13,14, which has been identified as one of the major bottlenecks for widespread implementation of electrocatalytic conversion reactions in the chemical industry.

The development and application of advanced in situ microspectroscopic investigations with multiscale spatial and time resolution are of paramount importance to elucidate the structure-function relationships of CO2 reduction electrocatalysts15,16,17. For this purpose, (synchrotron-based) X-ray methods are ideally suited because they allow for multiscale probing of material characteristics with high spatiotemporal resolution18,19,20,21. Furthermore, the choice of a particular X-ray method and combinations thereof potentially result in complementary information about size, shape and composition of catalyst particles, which are crucial parameters determining the reaction outcome during CO2 electroreduction. In the state of the art, operando X-ray absorption spectroscopy studies revealed the chemical reduction of cupric oxide (CuO) to copper and the simultaneous formation of disordered and under-coordinated Cu atoms for boosted electrocatalytic CO2 reduction reaction to hydrocarbons10,22,23,24. Furthermore, in situ X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies were successfully performed to elucidate temporal variations in crystalline structure and grain size during activation and deactivation of electrocatalysts at work25,26,27. However, insights into (de)activation of electrocatalysts through in situ characterization with ensemble statistics and optimal spatiotemporal resolution require the combination of complementary techniques over multiple length scales.

This study presents a multiscale X-ray scattering approach to elucidate the activation and deactivation of oxide-derived copper electrocatalyst particles for CO2 reduction. The oxide-derived copper electrocatalyst particles under study displayed boosted C–C coupling after cathodic-bias onset at short timescales, but a decrease in catalytic performance is observed after prolonged operation for 30 min. These changes are potentially caused by variations in catalyst structure, size, shape and composition, which are ideally probed simultaneously with high spatiotemporal resolution. In situ X-ray scattering at wide angles provides information on the crystal structure and crystalline domain size, whereas at small angles the scattering is determined by size, shape and volume of the scattering objects28,29,30,31,32,33. We extracted the dynamics of activation and deactivation of micron-sized Cu2O octahedral and cubic electrocatalyst particles, deposited on thin glassy carbon substrates, from milliseconds up to 30 min by building a detailed model for X-ray scattering of particles of different sizes and morphologies. With our in situ X-ray scattering methodology, we find that (1) during activation, the morphology of the pristine Cu2O octahedra is inherited by the activated copper electrocatalyst (as confirmed by ex-situ electron microscopy), (2) the Cu2O fully reduced to metallic Cu within 40 s, and (3) the size of the active electrocatalyst decreased during activation in the first minute due to lattice contraction, accompanied by an increased polydispersity and porosity. On longer timescales, changes in the power-law slope of the scattering pattern in the high-scattering-vector regime evidenced roughening of the electrocatalyst on longer length scales (up to 100 nm), and the dynamics of the increased roughening over the course of half an hour were elucidated. We linked these in situ X-ray scattering observations to the variations in catalytic performance monitored by changes in product distribution and different adsorbed reaction intermediates through in situ Raman spectroscopy measurements. The in situ Raman spectroscopy data revealed that the surface reduced to metallic copper within 30 s (in line with the in situ X-ray scattering data), followed by the appearance of surface-bound carbon monoxide (*CO at 280, 360 and 2090 cm–1) on undercoordinated surface sites over the next few seconds. The characteristic Cu–CO vibrational features are replaced by signals due to strongly bound, inactive, and poisonous bridged CO (*CObr at 460–500 cm–1 and 1950 cm–1) on planar surface sites over the next few minutes, accompanied by a decrease in C2 hydrocarbon selectivity over the course of half an hour. This study reveals the intimate relationship between electrocatalyst structure and performance during electrochemical CO2 reduction and showcases the potential of multiscale in situ X-ray scattering techniques to elucidate activation and deactivation of electrocatalysts of varying size, shape and polydispersity.

Results and discussion

It has been reported in the literature that oxide-derived copper electrocatalyst particles experience higher selectivity to multicarbon (C2+) reaction products (e.g., ethylene) than their metallic counterparts in electrochemical CO2 reduction, especially in the early stages after cathodic-bias onset (Fig. 1a)10,11,23,34. However, as reaction time progresses, the product distribution changes in favor of hydrogen production (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, the structure of the pristine electrocatalyst is substantially different from the spent electrocatalyst, as evidenced through ex-situ scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis, showcasing the intimate relationship between catalyst performance and structure. Ex situ SEM analysis (Fig. 1c–e) reveals that the pristine well-defined Cu2O electrocatalyst particles studied in this work (e.g., octahedra, Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. SI1, crystal structure confirmed by XRD, see Supplementary Fig. SI2, and cubes, see Supplementary Fig. SI3)35 display a roughened morphology after prolonged operation (Fig. 1d, e), which was further confirmed with electrochemical active surface area analysis (see Supplementary Fig. SI4 for cyclic voltammograms of octahedra and cubes).

Cartoons showing the main products formed during electrochemical CO2 reduction over octahedral Cu2O electrocatalyst particles at early stages of cathodic bias (a) and after prolonged operation up to 30 min (b). Representative ex situ SEM images of pristine Cu2O (c) and spent Cu electrocatalyst particles after 15 (d) and 30 min (e) of –1.0 VRHE cathodic bias, showing increasing surface roughness on various length scales. f Illustration of the custom electrochemical cell used for the in situ X-ray scattering experiments. Detectors show representative 2D in situ wide- and small-angle X-ray scattering patterns and the length scales probed with WAXS and SAXS. The dashed arrows show the azimuthal integration of the data and the solid arrows the scattering vector q. g Faradaic efficiency of the three main CO2 reduction reaction gas products at –1.0 VRHE over the course of one hour (note: H2 is omitted from this plot, and included in Supplementary Fig. SI5). The error bars correspond to data from three independent experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

After 15 min of cathodic bias at –1.0 VRHE, the octahedral shape is still discernible in the SEM images, but the surface appears to consist of smaller grains36. The formation of smaller crystalline Cu grains is also inferred from the surface sensitive ex situ grazing-incidence X-ray diffraction (GI-XRD) patterns of the spent particles (see Supplementary Fig. SI2), which show broadening of the characteristic Cu reflections. Detailed image analysis of the SEM images reveals roughening on the nanometre scale (up to 100 nm) of selected facets (see Supplementary Fig. SI1). Statistically more relevant characterization of surface roughness and insights into the roughening dynamics with ensemble statistics are possible with combined small- and wide-angle X-ray scattering (Fig. 1f). The use of X-ray scattering for electrocatalyst characterization is still in its infancy compared to diffraction and spectroscopy, despite its favorable characteristics for multiscale in situ characterization of size, shape, and size dispersion (small-angle X-ray scattering, SAXS) and crystalline structure (wide-angle X-ray scattering, WAXS) with ensemble statistics. Only a few recent reports have highlighted the potential of X-ray scattering for electrocatalysis research17,26,37,38,39,40, but in situ, SAXS patterns on par with ex-situ patterns have not been demonstrated yet. High-quality in situ data are challenging to obtain because of background scattering and beam attenuation due to the electrode substrate (e.g., glassy carbon) and aqueous electrolyte. Our custom in situ cell for X-ray scattering experiments minimizes the contribution from background scattering and beam attenuation by decreasing the pathlength of the X-rays through the glassy carbon substrate and electrolyte (Fig. 1f). From Fig. 1g, it is evident that the selectivity towards CO2 reduction products decreases in favor of hydrogen (see Supplementary Fig. SI5) on timescales similar to those of the structural changes observed by ex situ SEM. To correlate the temporal variations in product distribution for oxide-derived copper octahedra (Fig. 1g) and cubes to the observed structural changes and roughening, we use a multiscale in situ X-ray scattering approach with ensemble statistics and high spatiotemporal resolution over a wide q range (Fig. 1f, from 0.1 nm–1 down to 3 × 10–3 nm–1 in SAXS, corresponding to ~60 nm to 2 micron in real space) from milliseconds to half an hour after cathodic-bias onset.

Morphological and structural changes during the activation phase

From the chronoamperometry data of the Cu2O particles (see Supplementary Fig. SI6 for data in H-cell and in situ transmission cell), two main timeframes for electrocatalytic reduction are observed. In the first minute (activation phase), the reduction of Cu2O to Cu occurs, indicated by the high cathodic current, accompanied by CO2 reduction on oxide-derived Cu. After the first minute, the current originates from the reduction of CO2 and hydrogen evolution on the metallic copper. The activation of Cu2O octahedra to oxide-derived Cu was monitored with in situ WAXS and SAXS at the ID02 beamline of the ESRF with millisecond time resolution, details in Supplementary Information (SI) Section A. A custom electrochemical cell for transmission X-ray scattering experiments was used (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. SI7), the copper oxide particles were deposited on thin glassy carbon substrates (180 μm thickness to minimize background scattering and attenuation) and CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3 aqueous electrolyte solution was pumped through the cell with a peristaltic pump (electrolyte flow 10 mL/min, see SI section A for further details). The octahedra and cubes were exposed to –0.40, –1.0 and –1.25 VRHE and SAXS and WAXS patterns were collected simultaneously. All figures in the main text contain data of the experiments at –1.0 VRHE bias for the octahedral particles, and all other data, including further experimental details and the data for the cubic Cu2O particles, can be found in SI sections B and C. In Fig. 2, SAXS and WAXS scattering patterns and analysis for the first minute of the reaction are depicted (ex situ scattering patterns prior to reduction displayed in Supplementary Fig. SI8). The 2D SAXS and WAXS patterns were azimuthally integrated followed by a baseline subtraction to correct for background scattering of the electrolyte, glassy carbon, and other contributions. Data processing details are provided in the experimental section (see SI section B and Methods).

An iR-corrected electrode potential of –1.0 VRHE is applied at time t = 0. a Wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) patterns measured at t = 0 s and t = 60 s, patterns are shifted for clarity. Inset shows a zoom of the Cu2O (111) and Cu (111) reflections. b Calculated X-ray powder diffractogram for Cu (red) and Cu2O (blue)69,70. c Differential WAXS patterns, relative to the mean of the initial 10 diffractograms (recorded over the first 3.4 s). Blue region: negative features. Red regions: positive features. d Normalized differential WAXS signal of Cu (111) and Cu2O (111) peaks in red and blue, respectively, during the first minute. e Six representative small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) patterns (dots) and corresponding fits (solid lines) taken during the first 60 s (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 60 s) of the reaction (vertically shifted for clarity). The purple and green dashed lines indicate the position of the second minimum for the first and last pattern, respectively. The model is fitted to the q-value range highlighted in grey. f Mean edge length as a function of the reaction time, as determined by fitting the SAXS patterns. The light blue shaded area shows the ±σ polydispersity of the particles. g Cartoon showing the shrinkage effect of electrochemical reduction on the unit cell of Cu2O and Cu. h Focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM) imaging of a singular spent octahedron reveals a porous interior within the particle. i Scattering invariant of octahedral catalyst particles as function of time for cathodic biases of –1.0 VRHE. The data is normalised with respect to the first measurement of each experiment (scattering invariant of 1.0). The expected increase in the scattering invariant for full conversion of Cu2O to Cu with retention of all Cu atoms in the final particles is indicated by the grey dashed line (see Supplementary Fig. SI16). j In situ Raman spectra collected during the first minute of the reaction (15 s per spectrum). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Wide-angle X-ray scattering during activation: crystalline phase and grain size

The WAXS patterns in Fig. 2a show the complete phase transformation from Cu2O (characteristic diffraction peaks at q = 25.5, 29.4, 41.6 and 48.8 nm–1) to Cu (characteristic diffraction peaks at q = 30.2, 34.5 and 48 nm–1) over the course of 60 s at a cathodic bias of –1.0 VRHE. The assignments of the reflections are shown in Fig. 2b and the gradual transformation from Cu2O to Cu is visualized in Fig. 2c, which presents the change in diffraction intensity with respect to the initial WAXS pattern as a function of time. Here, blue regions denote a decrease in diffraction intensity, whereas red regions correspond to increased diffraction intensity (see Supplementary Fig. SI9 for the other potentials). The diffraction peaks of the initial Cu2O particles have instrumentation-limited widths of 0.07 nm–1 (Fig. 2a; see Supplementary Fig. SI10 for characterization of the instrument resolution). The numerically integrated intensities of the peak area of Cu2O (111) and Cu (111) are analyzed as a function of time (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. SI11), showing that the Cu2O (111) diffraction intensity decreases slightly before the ingrowth of Cu (111) diffraction intensity. The metallic Cu reflections are absent during the first 10 s, indicating an activation period, but gradually increase in intensity during the first 60 s, until they fully dominate the WAXS patterns and no Cu2O reflections can be discerned. The width of the Cu reflections is 0.5 nm–1, which is significantly broader than those of Cu2O, indicating smaller crystalline Cu domains in the activated electrocatalyst particles (see Supplementary Fig. SI11).

Small-angle X-ray scattering in the first minute of activation: morphology and size

Figure 2e shows the SAXS patterns at different times during the first minute of reaction under –1 VRHE (Supplementary Fig. SI12 for other potentials). Multiple oscillations are observed between 0.009 and 0.09 nm–1, which closely match a model of individual polydisperse equilateral octahedra with random orientations (solid lines in Fig. 2e, SI section B and Supplementary Fig. SI13)41,42. An alternative model of octahedra with a preferential orientation matches the data less well (Supplementary Fig. SI13). The observed deviation between the individual-particle model and the data at q < 0.02 nm–1 is consistent with a structure-factor contribution due to random particle stacking on the electrode (Supplementary Fig. SI14). We note that the first minimum is smeared due to the instrument resolution of 0.0005 nm–1, and therefore the second minimum is used in our analysis. Over the course of the experiment, the minima in the scattering patterns shift to higher q values, showing shrinking of the particles. The decreasing amplitude and number of the oscillations over time indicates increasing polydispersity. Figure 2f shows the evolution of the mean particle edge length obtained from the fitted model. Over the course of a minute, the particles shrink from an edge length of 830 nm to 750 nm. The blue shaded area represents the particle polydispersity, which increases from 2% at the beginning to 8% after 1 min. The shrinking kinetics from SAXS overlay well with the phase transformation kinetics from WAXS (compare Fig. 2d–f), suggesting that the shrinking is associated with the smaller unit cell of Cu compared to Cu2O. Indeed, a size decrease is expected upon phase transformation from Cu2O to Cu (Fig. 2g). However, a size decrease to 85% of the initial size would be calculated from the unit cell lengths of Cu2O and Cu (4.25 to 3.61 Å, respectively), while the observed decrease is only to 90%43,44. Hence, our final particles are larger than would be possible for solid Cu particles containing the same amount of Cu as the precursor Cu2O particles. Therefore, we infer that our oversized particles are porous. Indeed, holes in the Cu particles are confirmed with ex-situ focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM) experiments (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. SI15). This porosity is a necessary consequence of the limited shrinking of the particles upon reduction. In analogy to the nanoscale Kirkendall effect, pores or voids can develop inside the particles if the reduction is too quick so that outgoing and ingoing diffusion rates are unbalanced (e.g., inward Cu diffusion and outward O diffusion). Porous copper and copper oxide scaffolds have been previously observed in literature, where pore formation is also ascribed to the reduction kinetics during thermal activation45. The increase in polydispersity upon reduction, as observed with SAXS, may reflect variations in porosity among the final Cu particles.

Cu leaching could additionally contribute to the formation or growth of holes in the Cu particles. We checked this possibility by the analysis of the scattering invariant (Fig. 2i). This parameter gives a measure for the total scattering intensity of a sample (see Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Fig. SI16) and is sensitive to the amount of scattering material and its electron density. We observe that the scattering invariant increases within the first minute (Fig. 2i). This is in line with Cu2O reduction to Cu. Although the Cu particles are smaller than the precursor Cu2O particles, the electron density of Cu is higher. The net effect is an expected increase in the scattering invariant by 57% (Supplementary Fig. SI16, dashed line). Experimentally, the increase in scattering invariant is smaller (29%). The deviation (29% vs. 57%) could be due to contributions of the background scattering from the electrochemical cell. After 30 s, when the reduction is finished, the scattering invariant increases slowly (Fig. 2i). This is not consistent with significant Cu leaching, which would decrease the scattering invariant as the solid volume of the particles would go down. In contrast, the slowly increasing scattering invariant indicates that the porosity slowly decreases over time. To verify the contribution of Cu leaching to the pore formation, we analyzed the electrolyte with UV–Vis spectroscopy measurements (Supplementary Fig. SI17). We prepared stock solutions of 0.1 mM dmphen (2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline) according to recent literature46 and added this to the electrolytes collected after CO2 reduction experiments (30 min and 9 h). No UV–Vis absorption band is detected that can be related to [Cu(dmphen)2]+ (reproduced by dissolving CuI and dmphen into deionized water, with a distinct absorption band centred at ~450 nm and an OD of 0.03 for a 67 μM solution). We estimate the detection limit to be 1 μM based on the signal to noise ratio. Complete leaching of Cu+ from Cu2O would result in 76.9 μM [Cu(dmphen)2]+, see Supplementary Discussion. We therefore conclude that Cu leaching from our Cu2O octahedra is undetectable with an upper limit of 1.3% Cu and that rapid reduction is the dominant process resulting in pore formation. The porosity explains the larger size of the scattering objects from SAXS analysis, compared to the expected particle size due to the phase transformation. The increase in polydispersity upon reduction as observed with SAXS may reflect variations in porosity among the final Cu particles. The same analysis was performed for the cubic Cu2O electrocatalyst (Supplementary Fig. SI18), which revealed similar dynamics during activation: fast Cu2O to Cu reduction from WAXS and decrease in edge length to 88% (~1100 nm to ~950 nm) from SAXS. The discrepancy between the decrease in edge length from SAXS analysis and the calculated shrinkage (to 85%) based on the Cu2O and Cu lattices indicates the presence of voids for the cubic particles as well, similar to the observation for the octahedra. We note that the pristine cubic Cu2O particles have a larger polydispersity than the octahedral particles, highlighting the robustness of our model to analyse size, shape and polydispersity of various electrocatalyst particles.

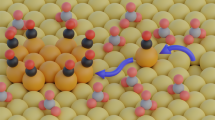

To couple the observed dynamics of the electrocatalyst structure and morphology during activation to the concomitant changes at the electrode/electrolyte interface, in situ Raman spectroscopy was performed (Fig. 2j). The in situ Raman spectra collected in the first minute show that the bands of Cu2O (390, 520, and 630 cm–1) disappear within the first 15 s, in line with the rapid reduction observed with WAXS. The spectrum at 15 s displays almost no signal, indicating a similar timescale for the activation period of Cu2O into Cu as found with in situ WAXS. Characteristic bands for linear adsorbed CO (*CO) on undercoordinated sites at 280 and 360 cm–1 appear after 30 s, corresponding to Cu–CO bending and Cu–C linear stretching vibrations, respectively47,48. Adsorbed CO is very sensitive to the atomic-scale structure of the Cu surface. Specifically, the linear CO stretch vibration is roughly divided in literature into multibound (1800–1900 cm–1), bridged (1900–2000 cm–1), terrace site (~2050 cm–1), undercoordinated site (~2090 cm–1, accompanied by features at 280 and 360 cm–1) and oxidized Cu (>2100 cm–1)49. The presence of dominant features at 280 and 360 cm–1 indicates that the activated Cu surface has many undercoordinated sites, for example adatoms, dendrites or steps and edges50,51. Such surface details are not observable in the SAXS data, highlighting that Raman spectroscopy and X-ray scattering are useful complementary techniques.

Morphological and structural changes after the first minute: deactivation period

In the time-dependent electrocatalytic performance, an increased production of hydrogen is observed at the expense of carbon-containing CO2 reduction products over a period of half an hour (Supplementary Fig. SI19). The stability of the Cu2O electrocatalysts was studied for 9 h (Supplementary Fig. SI20), showing a decrease in CO2 reduction products over time. The in situ WAXS data shows that after 1 min, the crystal phase of the particles remains constant with no clear variations in grain size over the course of 30 min (Supplementary Fig. SI21). However, subtle structural changes are revealed by the SAXS patterns at prolonged cathodic bias (Fig. 3a), especially in the SAXS regime at q > 0.05 nm–1. Going from 1 min to 30 min of cathodic bias, the slope of the SAXS patterns at q > 0.05 nm–1 (the Porod regime) changes from q–4 to q–3, indicating an increase in scattering at larger q values (Fig. 3b). The model we used to fit the SAXS patterns during the activation phase, which assumed smooth octahedra, exhibits a slope of q–4 and is no longer suitable to fit the SAXS patterns at longer operation time of 30 min. Using the simple relationship q = 2π/d, we estimate that the increase in scattering (at 0.05 nm–1) is the result of an increase in scattering objects of size d = 100 nm. We propose that the increased scattering is due to increased surface roughness, in line with ex situ SEM of the spent catalyst at different times (Fig. 1d, e). Indeed, we can reproduce the changes in the scattering at high q with models of octahedra with increasingly rough surfaces, which we express in terms of the parameter Pgrow (Fig. 3c–e and SI section C)52. Supplementary Fig. SI22 describes the different surface-roughness models that we tested, of which the best is presented here in Fig. 3c. We conclude that increased scattering at high q is caused by an increase in surface roughness on length scales of ~100 nm, which occurs only after prolonged cathodic bias (t = 30 min). Porosity on the 100-nm length scale could also contribute to the increased scattering at larger q values (Fig. SI22), but such large pores are not consistent with the FIB-SEM data (Fig. 2h). In future SAXS experiments on more porous samples, where porosity is the dominant type of roughness, the degree and length scale of porosity could be followed in situ, as we did here for surface roughness, highlighting the potential of our SAXS methodology for analyzing morphological changes during operation.

a Six representative small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) patterns (dots) showing the changes in catalyst shape over time, and corresponding fits to a model of polydisperse smooth octahedra (solid lines). The patterns are shifted for clarity. The model is fitted to the data in the grey shaded area. The change in slope of the SAXS patterns from a q–4 to a q–3 dependence indicates increased surface roughening on the 100 nm length scale. b Analytical form factor of smooth octahedra (black) and form factors based on a discrete scatterer model of octahedra with increasing surface roughness (light to dark red). c–e Simulated particles with increasingly rough octahedra (more details in Supplementary Information). In situ (surface-enhanced) Raman spectroscopy (SERS) measurements conducted on Cu2O octahedra in the f low- and g high-Raman-shift regime. Each spectrum is an average of 3 different spots acquired over a 5 min duration. The top spectrum was obtained after 120 min, and an extended version is presented in Supplementary Fig. SI23. Cartoons of the observed vibrational features for h linear adsorbed CO, i low-frequency band CO, and j bridged CO. k, l Schematic of structural changes observed with in situ X-ray scattering. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In the literature, increased roughness on the nanometre scale is usually associated with a boost in electrocatalytic activity due to the abundant presence of undercoordinated sites53,54,55,56. However, we observe a decrease in electrocatalytic activity at prolonged cathodic bias (up to 30 min) on similar timescales as the appearance of surface roughness of ~100 nm from the SAXS analysis. To correlate the changes in selectivity to the changes in electrocatalyst structure, in situ Raman spectroscopy on similar time scales was performed. The results, shown in Fig. 3f, g and Supplementary Fig. SI23, reveal the dynamics of *CO surface intermediates. It is found that on activated oxide-derived copper surfaces, the characteristic vibrations of linear CO on Cu are dominant in the initial 15 min (Cu-CO bending at 280 cm–1, Cu-C stretch at 360 cm–1 and linear CO stretch at 2050–2090 cm–1, Fig. 3f–i), accompanied by lower intensity vibrational features between 450 and 500 cm–1. Subsequently, the vibrational features in the 450–500 cm–1 region increase in intensity after prolonged operation (t > 15 min), until they are the sole species at t > 30 min. The vibrational features between 450 and 500 cm–1 clearly consist of two bands, initially centred at around 460 and 495 cm–1. These bands are already present after a few s of cathodic bias (Fig. 2i) but increase in intensity over time. Furthermore, the ratio between 460 and 495 cm–1 changes as a function of time, suggesting they either originate from different surface-adsorbed species or from a molecule with a Raman spectrum that changes with the surface coverage. For example, the ratio between the 280 and 360 cm–1 features has been inferred to correlate with CO coverage and C2+ hydrocarbon production57. The low 360/280 cm–1 band intensity ratio observed in our data (see Supplementary Fig. SI24) indicates low *CO surface coverage on these time scales, in line with a low ethylene production57. Linear *CO vibrations are discerned at 2050–2090 cm–1 during the first 20 min as well, supporting the assignment of the 280 and 360 cm–1 features to Cu–CO. These linear *CO features are no longer present after 120 min of cathodic bias, and a broad feature at 1950 cm–1 is discernible, which is typically ascribed to multibound CO or bridged CO in literature. It has been debated in the literature whether bridged CO acts as poisonous or spectator species during electrochemical CO2 reduction58,59,60,61. We infer that bridged CO is a poisonous species in our experiments since electrochemical oxidation and subsequent cathodic bias reinstates single-bound *CO as the dominant surface intermediate and results in boosted CO2 reduction toward carbon-containing products (Supplementary Fig. SI25). We suggest that the surface roughness on length scales of ~100 nm favors the formation of planar surface sites and the presence of bridged CO, in contrast to activated oxide-derived copper surfaces with abundant undercoordinated sites and the dominant presence of single-bound *CO at the surface (Fig. 3k,l). This can be explained by ripening due to atom rearrangements and coalescence of dendrites and other protrusions on the surface, which smoothens the atomic-scale roughness but creates inhomogeneities on larger length scales. Figure 3k–l illustrates the overarching degradation mechanism revealed by the combination of X-ray scattering and Raman spectroscopy: as the length scale of surface roughness increases to 100 nm (X-ray scattering), well beyond the atomic range, the CO adsorption geometry becomes similar to that on a planar surface (Raman spectroscopy).

In our previous work, we performed 13C labeling experiments to confirm that the bands at 460 and 495 cm–1 correspond to Cu–C related intermediates, which coincided with the dominant presence of low-frequency CO at 2050 cm–1 (Fig. 3i), previously attributed to C–C directing species55,62,63. However, in our current experiments, the 495 cm–1 band slightly shifts to 500 cm–1 over time (t = 120 min), suggesting an increasing Cu–C bond strength. The vibrational energy of the Cu–C stretch vibration of multibound or bridged CO is expected to give rise to a vibrational feature at higher Raman shift compared to single-bound CO (e.g., at around 460–500 cm–1) because the electron density on the Cu–C bond is higher for bridged CO compared to single-bound Cu–CO. The vibrations around 500 cm–1 may thus be a combination of Cu–C stretch vibrations of C–C coupled, bridged, or multibound CO intermediates (Fig. 3h–j), which are hard to distinguish because of spectral overlap. According to the Sabatier principle, an active intermediate should not bind too strongly nor too weakly. The observed increase in Cu–C binding strength for the intermediates present at t = 120 min is in line with our assignment and previous observations in the literature from infrared spectroscopy studies that bridged CO is less active or a potential poisonous/spectator species64. This also agrees well with the decrease in CO2 reduction products and the increased roughening after prolonged operation, suggesting that the roughening in the 100 nm range results in deactivation of the catalyst through favored formation of multibound or bridged CO species on planar surface sites26. Based on our results, we conclude that undercoordinated surface sites are necessary for an active CO2 reduction catalyst, and that increasing the length scale of roughness by ripening should be avoided. Recovery of roughness on the atomic length scales can be achieved through rapid anodic pulses (e.g., in Fig. SI25)65, which ensures the abundant presence of undercoordinated sites through a dissolution/redeposition mechanism14. Furthermore, recent strategies to stabilize electrocatalyst particles, including (1) organic surface functionalization66,67, (2) alloying68 and (3) inorganic hybrid coatings13, can be investigated to ensure stable production of valuable chemicals from CO2.

This study offers real-time multiscale insights into the activation, operation, and deactivation of oxide-derived copper electrocatalysts during CO2 electroreduction, thereby elucidating the interplay between catalyst selectivity and morphological changes. Directly after electrocatalyst activation, ethylene and carbon monoxide are the dominant CO2 reduction products, whereas hydrogen formation takes over during prolonged operation. Through multiscale in situ small- and wide-angle X-ray scattering, the initial activation and subsequent surface roughening and deactivation was elucidated. In situ, SAXS and WAXS analysis and related models revealed the dynamic transformation from sharp Cu2O peaks to broad Cu peaks in the WAXS patterns during activation (t < 1 min), accompanied by a loss of well-defined particle size distribution and a decrease in particle size in the SAXS patterns. Both observations are indicative of the electrocatalyst activation process, leading to the formation of small crystalline domains of Cu and a non-uniform particle size distribution within the first minute after cathodic-bias onset. In situ Raman spectroscopy revealed the dominant presence of *CO directly after activation, with characteristic bands at 280, 360 and 2090 cm–1, indicative of *CO on undercoordinated surface sites. At prolonged operation, more subtle structural and morphological changes were observed through multiscale in situ X-ray scattering. An increased scattering at high q (>0.05 nm–1) over time is attributed to an increasing surface roughness on the 100 nm length scale, as evidenced by our models, consistent with the slope of the scattering pattern (intensity scales with q–3) that deviates from q–4 dependence for isotropic and uniform octahedra. These structural and morphological changes are coupled to time-dependent reaction intermediates through in situ Raman spectroscopy. These measurements revealed that single-bound Cu–CO species dominate the spectra after activation, which are replaced by bridged CO at planar surface sites after prolonged cathodic bias. We infer that the presence of bridged CO is correlated to the observed surface roughening from our SAXS analysis. With increasing catalyst roughening, the intensity of the vibrational bands at around 460–500 cm–1 rises, which is ascribed to poisoning species at the roughened copper surface, such as multibound or bridged CO, resulting in electrocatalyst deactivation. Our study reveals the dynamic relationship between electrocatalyst structure and performance during CO2 reduction, shedding light on catalyst activation and deactivation pathways that have the potential to aid the design of stable electrocatalysts for enhanced CO2 conversion.

Methods

Chemicals

The following chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich: polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, Mw = 29,000), l-ascorbic acid (99%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, pellets, ≥98%), copper (II) chloride anhydrous (CuCl2, >98%), copper (I) iodide (CuI, >99.5%), 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline (neocuproine, dmphen, >98%), methanol (HPLC grade), potassium bicarbonate (KHCO3, purity >99.7%). Ultrapure water was retrieved via a Direct-Q® 3 UV water purification system. Sulfuric acid (H2SO4, AnalaR NORMAPUR® analytical reagent, 95–97%) was purchased from VWR Chemicals. Absolute ethanol (99.5%) was purchased from Acros. Carbon dioxide gas (CO2, purity: 99.995%) was purchased from Linde Gas. Polishing powders (5 μm CeO2 and 1 μm Al2O3) were purchased from Bodemschat.

Synthesis of Cu2O octahedra and cubes

A procedure by Zhang et al. was used to synthesize the octahedral Cu2O electrocatalyst particles35. In a typical synthesis, CuCl2 (135.0 mg) was added to a 250 mL round bottom flask with stirrer and dissolved in 80 mL of ultrapure H2O. This mixture was heated with a water bath set to 55 °C under stirring. Upon reaching this temperature, PVP powder (0 g or 3 g for cubes or octahedra, respectively) was directly added. After everything was dissolved, 10 mL of 2.0 M NaOH was slowly added over the course of 10 min. A color change is observed from light blue to brown, and the solution was set to react for 30 min. After 30 min, 10 mL of 0.6 M reducing agent l-ascorbic acid solution was added to the mixture over the course of 10 min. This mixture was set to react for 3 h in which a color change from dark brown to a brick-red color is observed. The reaction mixture was then centrifuged for 2 min at 3000 rpm and the supernatant was discarded. The remaining particles were washed three times with a 1:1 ethanol:water mixture and stored in 10 mL of pure methanol, yielding typically a 5.5 mg/mL dispersion.

Electrode preparation

Two different substrate materials have been used to prepare the electrodes, carbon paper and glassy carbon. TGP-H 060 carbon paper is used and is cut into pieces of 1 × 2 cm. The cut carbon papers are then treated overnight in an aqua regia solution and afterwards washed 5 times with ultrapure water and twice with ethanol. After washing, the carbon papers are dried in an oven set to 60 °C. To prepare the carbon paper electrode, the carbon paper is placed horizontally in a clamp and 10 µL of the catalyst suspension is drop casted 2 times with a Finn-pipette, directly from the methanol suspension. After each 20 µL added, the electrode was let to dry in air.

HTW glassy carbon electrodes (GCE) were all cut to a size of 1 × 1 cm, and they were polished using Al2O3 powder. After polishing, they were transferred into a small flask together with a mixture of ethanol, acetone and water in ratio 1:1:2. The flask was then sonicated for ~10 min and the glassy carbon was washed with ultrapure water afterwards. The catalyst was then added directly from the ethanol suspension on top of the dry glassy carbon. After the GCE was dry, they were transferred to a Ossila UV Ozone Cleaner to get rid of any residual organics. For the Raman spectroscopy measurements, a typical electrode had ~80 µL of the catalyst suspension. After each experiment, the glassy carbon was cleaned with a wet wipe and polished and cleaned again. For the WAXS and SAXS measurements, thin glassy carbon electrodes (SIGRADUR K discs, diameter 22 mm, 180 µm thickness) were used and cleaned as described above.

Electrochemical measurements

All electrochemical experiments were performed in a CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3 solution (pH = 6.8) at room temperature and atmospheric pressure. 0.1 M KHCO3 aqueous solution was saturated with CO2 for at least 30 min to obtain an electrolyte with pH of 6.8. During the experiments, CO2 was continuously delivered into the cathodic chamber at a constant rate of 10 mL min−1. Pt mesh electrodes were used as a counter electrode and a leakless Ag/AgCl reference electrode (eDAQ) was used as a reference. A proton exchange membrane (Nafion 117, Dupont) was placed between cathode and anode chambers (both 20 mL) in a gas-tight H-cell. The iR-corrected potential EAg/AgCl with respect to Ag/AgCl was converted to a potential ERHE with respect to RHE (iR-corrected) using the determined resistance (~50 Ohm) and Eq. (1):

where R is the gas constant, F Faraday’s constant, and T = 293 K the temperature. Electrochemical measurements were performed on a Ivium compactstat.h10800 potentiostat (activity & X-ray) and an Autolab PGSTAT101 (Raman). Data was collected through the provided software of the potentiostats and the data was analyzed through a custom Python script. The Electrochemical Surface Area (ECSA) was evaluated by the double−layer capacitance (Cdl) through the Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) measurements at different scan rates in the non−Faradaic region by a linear fit of the charging current.

Activity

The activity evaluation of the Cu2O electrocatalyst particles for electrochemical CO2 reduction (eCO2RR) was carried out in a custom quartz H-cell. A platinum mesh was used as counter electrode, and a leakless Ag/AgCl reference electrode (eDAQ) was used for controlling the applied potential on the working electrode. The flow rate of CO2 was kept at 10 sccm. Gas products were quantified using an Interscience online gas chromatography (GC) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID, for hydrocarbons) and a thermal conductivity detector (TCD, for hydrogen) detector. A methanizer was used to detect CO and CO2. The GC injected a sample every 4 min. The Faradaic efficiency (FE) for the formation of a certain product i was calculated, using:

where ni is the number of electrons involved in the formation of product i, ci is the molar fraction of product i in the output gas mixture, f is the volumetric flow rate of CO2 gas, I is the average current over 4 min, and Vm = 22.4 L is the molar gas volume at the reaction temperature and pressure.

In situ X-ray scattering measurements

SAXS and WAXS measurements were performed at the ID02 beamline at the ESRF, at an energy of 18.0 keV. For the in situ experiments the catalyst particles were drop-casted onto a glassy carbon electrode and placed in a custom electrochemical cell, in which the path length of the collimated X-ray beam through the electrolyte was minimized to 4.5 mm to reduce background scattering and attenuation (Supplementary Fig. SI15). A CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3 electrolyte solution was pumped continuously through the cell (10 mL/min), and no membrane was used. Pt wire was used as counter electrode and a leakless Ag/AgCl miniature electrode as reference (1 mm diameter, Alvatek). At large scattering angles (q = 20–55 nm–1) X-rays were collected using a Rayonix LX170 WAXS detector, giving information about the changes in crystal structure of the particles. At small scattering angles (q = 3 × 10–3–10–1 nm–1 at sample-detector-distance of 31 m), the X-rays were detected using a Eiger2-4M detector (placed on a rail inside a vacuum flight tube), giving information about the shape, size, size dispersion and surface of the particles. Measurements were conducted at an iR-corrected potential of –0.4, –1.0 and –1.2 VRHE. To capture the fast particle restructuring at the sort time scale as well as the slower structural changes at the long-time scale, a time profile was used where the time between frames increased exponentially:

where ti is the integration time per frame (10 ms), tw is the initial waiting time (70 ms), S is a scaling factor (1.01) and n is the frame number. This resulted in a temporal resolution of 80 ms at the beginning of the experiment and about 15 s at the end of the experiment.

Raman spectroscopy measurements

The Raman spectroscopy measurements were performed on a Renishaw InVia confocal Raman microscope with a 785 nm laser. For time-resolved measurements, we measure in static mode with a Nikon CFI Apo NIR 40X W water-dipping objective with a numerical aperture of 0.8, resulting in a spot size of about a micron. The laser power on the sample was 2.4 mW. Each spectrum is an average of 3 spots on the Cu2O octahedra electrodes. On each spot, 3 spectra were collected with a time resolution of 18 s. A custom-made Raman cell was used, presented in our earlier work54,55. 0.1 M KHCO3 saturated with CO2 was used as electrolyte, and CO2 gas was bubbled at 10 sccm during the in situ Raman measurements, Pt wire as counter electrode and a leakless Ag/AgCl electrode as reference (2 mm diameter, Alvatek), and no membrane was used.

Scanning electron microscopy

The SEM images of the samples were recorded on a FEI Helios NanoLab G3 UC (FEI Company) instrument coupled with an Oxford Instruments Silicon Drift Detector X-Max energy-dispersive spectroscope. The samples were deposited onto Al stubs with carbon tape (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hartfield, PA, USA) without any coating treatment. Thereafter, secondary electron (SE) imaging was carried out with an Everhart–Thornley detector (ETD) and a beam of 10 kV, 0.1 nA and dwell time of 1 µs. FIB-SEM images were taken using the same instrument. A trench was made by milling perpendicularly to the surface, with an Ga ion beam of 30 kV and 0.43 nA. After milling the trench, a cleaning step was performed before imaging. SEM images of the cross-section were recorded in SE mode (2 kV, 0.1 nA) with a dwell time of 1 µs.

Grazing incidence X-ray diffraction measurements

XRD measurements were performed on a Bruker DISCOVER d8 with Cu Kα (1.540 Å) radiation using a grazing incidence (GI) mode, at an angle of incidence of 0.3 degrees to ensure surface sensitivity.

UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy measurements

UV-Vis absorption spectra were measured on a double-beam PerkinElmer Lambda 16 UV/vis spectrometer. A stock solution of 0.1 mM dmphen (2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline) in deionized water was prepared by dissolving dmphen (20.8 mg, 0.1 mmol) in 10 mL, and diluting the stock solution 100 times, according to literature46. A stock solution of 1 mM CuI in deionized water was prepared by dissolving CuI (1 mmol, 190.5 mg) in 10 mL, and diluting 100 times.

Data availability

The full dataset that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author(s). Source data are provided with this paper for the data presented in the main text (X-ray scattering, Raman spectra, electrochemical measurements, electron microscopy). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code developed and used in this study is available from the corresponding author(s).

References

Raaijman, S. J., Arulmozhi, N. & Koper, M. T. M. Morphological stability of copper surfaces under reducing conditions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 48730–48744 (2021).

Asiri, A. M. et al. Revisiting the impact of morphology and oxidation state of Cu on CO2 reduction using electrochemical flow cell. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 345–351 (2022).

Zaza, L., Rossi, K. & Buonsanti, R. Well-defined copper-based nanocatalysts for selective electrochemical reduction of CO2 to C2 products. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 1284–1291 (2022).

De Gregorio, G. L. et al. Facet-dependent selectivity of Cu catalysts in electrochemical CO2 reduction at commercially viable current densities. ACS Catal. 10, 4854–4862 (2020).

Monteiro, M. C. O. et al. Absence of CO2 electroreduction on copper, gold and silver electrodes without metal cations in solution. Nat. Catal. 4, 654–662 (2021).

Waegele, M. M., Gunathunge, C. M., Li, J. & Li, X. How cations affect the electric double layer and the rates and selectivity of electrocatalytic processes. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 160902 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. pH effects on the electrochemical reduction of CO2 towards C2 products on stepped copper. Nat. Commun. 10, 32 (2019).

Dattila, F., Garciá-Muelas, R. & López, N. Active and selective ensembles in oxide-derived copper catalysts for CO2 reduction. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 3176–3184 (2020).

Grosse, P. et al. Dynamic changes in the structure, chemical state and catalytic selectivity of Cu nanocubes during CO2 electroreduction: size and support effects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 130, 6300–6305 (2018).

Möller, T. et al. Electrocatalytic CO2 reduction on CuOx nanocubes: tracking the evolution of chemical state, geometric structure, and catalytic selectivity using operando spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 17974–17983 (2020).

Wang, S., Kou, T., Baker, S. E., Duoss, E. B. & Li, Y. Recent progress in electrochemical reduction of CO2 by oxide-derived copper catalysts. Mater. Today Nano 12, 100096 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Operando studies reveal active Cu nanograins for CO2 electroreduction. Nature 614, 262–269 (2023).

Albertini, P. P. et al. Hybrid oxide coatings generate stable Cu catalysts for CO2 electroreduction. Nat. Mater. 23, 680–687 (2024).

Popović, S. et al. Stability and degradation mechanisms of copper-based catalysts for electrochemical CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 14736–14746 (2020).

den Hollander, J. & van der Stam, W. In situ spectroscopy and diffraction to look inside the next generation of gas diffusion and zero-gap electrolyzers. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 42, 100979 (2023).

Ligt, B., Hensen, E. J. M. & Costa Figueiredo, M. Electrochemical interfaces during CO2 reduction on copper electrodes. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 41, 101351 (2023).

Van Der Stam, W. The necessity for multiscale in situ characterization of tailored electrocatalyst nanoparticle stability. Chem. Mater. 35, 386–394 (2023).

Li, X., Wang, S., Li, L., Sun, Y. & Xie, Y. Progress and perspective for in situ studies of CO2 reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 9567–9581 (2020).

Handoko, A. D., Wei, F., Yeo, B. S. & Seh, Z. W. Understanding heterogeneous electrocatalytic carbon dioxide reduction through operando techniques. Nat. Catal. 1, 922–934 (2018).

Yang, S. et al. Halide-guided active site exposure in bismuth electrocatalysts for selective CO2 conversion into formic acid. Nat. Catal. 6, 796–806 (2023).

Herzog, A. et al. Operando investigation of Ag-decorated Cu2O nanocube catalysts with enhanced CO2 electroreduction toward liquid products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 7426–7435 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Morphology and mechanism of highly selective Cu(II) oxide nanosheet catalysts for carbon dioxide electroreduction. Nat. Commun. 12, 794 (2021).

Velasco-Velez, J. J. et al. Revealing the active phase of copper during the electroreduction of CO2 in aqueous electrolyte by correlating in situ X-ray spectroscopy and in situ electron microscopy. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 2106–2111 (2020).

Timoshenko, J. & Roldan Cuenya, B. In situ/operando electrocatalyst characterization by X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Chem. Rev. 121, 882–961 (2021).

Lei, Q. et al. Structural evolution and strain generation of derived-Cu catalysts during CO2 electroreduction. Nat. Commun. 13, 4857 (2022).

Magnussen, O. M. et al. In situ and operando X-ray scattering methods in electrochemistry and electrocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 124, 629–721 (2024).

Timoshenko, J. et al. Steering the structure and selectivity of CO2 electroreduction catalysts by potential pulses. Nat. Catal. 5, 259–267 (2022).

Graewert, M. A. & Svergun, D. I. Impact and progress in small and wide angle X-ray scattering (SAXS and WAXS). Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 23, 748–754 (2013).

Bogar, M., Khalakhan, I., Gambitta, A., Yakovlev, Y. & Amenitsch, H. In situ electrochemical grazing incidence small angle X-Ray scattering: from the design of an electrochemical cell to an exemplary study of fuel cell catalyst degradation. J. Power Sources 477, 229030 (2020).

Pauw, B. R. Everything SAXS: small-angle scattering pattern collection and correction. J. Phys. Cond. Matter 25, 383201 (2013).

Prins, P. T. et al. Extended nucleation and superfocusing in colloidal semiconductor nanocrystal synthesis. Nano Lett. 21, 2487–2496 (2021).

Narayanan, T. Recent advances in synchrotron scattering methods for probing the structure and dynamics of colloids. Adv. Coll. Interf. Sci. 325, 103114 (2024).

Narayanan, T. et al. Performance of the time-resolved ultra-small-angle X-ray scattering beamline with the extremely brilliant source. J. Appl. l Crystallogr. 55, 98–111 (2022).

Grosse, P. et al. Dynamic transformation of cubic copper catalysts during CO2 electroreduction and its impact on catalytic selectivity. Nat. Commun. 12, 6736 (2021).

Zhang, D. F. et al. Delicate control of crystallographic facet-oriented Cu2O nanocrystals and the correlated adsorption ability. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 5220–5225 (2009).

Jiang, Y. et al. Structural reconstruction of Cu2O superparticles toward electrocatalytic CO2 reduction with high C2+ products selectivity. Adv. Sci. 9, 2105292 (2022).

Bergmann, A. & Roldan Cuenya, B. Operando insights into nanoparticle transformations during catalysis. ACS Catal. 9, 10020–10043 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. Operando resonant soft X-ray scattering studies of chemical environment and interparticle dynamics of Cu nanocatalysts for CO2 electroreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 8927–8931 (2022).

Moss, A. B. et al. In operando investigations of oscillatory water and carbonate effects in MEA-based CO2 electrolysis devices. Joule 7, 350–365 (2023).

Pittkowski, R. K. et al. Monitoring the structural changes in iridium nanoparticles during oxygen evolution electrocatalysis with operando X-ray total scattering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 27517–27527 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Scattering functions of platonic solids. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 545–557 (2011).

Goertz, V., Dingenouts, N. & Nirschl, H. Comparison of nanometric particle size distributions as determined by SAXS, TEM and analytical ultracentrifuge. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 26, 17–24 (2009).

Suh, I.-K., Ohta, H. & Waseda, Y. High-temperature thermal expansion of six metallic elements measured by dilatation method and X-ray diffraction. J. Mater. Sci. 23, 757–760 (1988).

Neuburger, M. C. Prazisionsmessung Der Gitterkonstante Von Cuprooxyd Cu2O. Z. Phys. 67, 845–850 (1930).

Unutulmazsoy, Y., Cancellieri, C., Lin, L. & Jeurgens, L. P. H. Reduction of thermally grown single-phase CuO and Cu2O thin films by in-situ time-resolved XRD. Appl. Surf. Sci. 588, 152896 (2022).

Vavra, J. et al. Solution-based Cu+ transient species mediate the reconstruction of copper electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction. Nat. Catal. 7, 89–97 (2024).

Chernyshova, I. V., Somasundaran, P. & Ponnurangam, S. On the origin of the elusive first intermediate of CO2 electroreduction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E9261–E9270 (2018).

Gunathunge, C. M. et al. Spectroscopic observation of reversible surface reconstruction of copper electrodes under CO2 reduction. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 12337–12344 (2017).

Jiang, S., Klingan, K., Pasquini, C. & Dau, H. New aspects of operando raman spectroscopy applied to electrochemical CO2 reduction on Cu foams. J. Chem. Phys. 150, 041718 (2019).

Zhang, G. et al. Efficient CO2 electroreduction on facet-selective copper films with high conversion rate. Nat. Commun. 12, 5745 (2021).

Arán-Ais, R. M., Scholten, F., Kunze, S., Rizo, R. & Roldan Cuenya, B. The role of in situ generated morphological motifs and Cu(I) species in C2+ product selectivity during CO2 pulsed electroreduction. Nat. Energy 5, 317 (2020).

Suzuki, T., Chiha, A. & Yano, T. Interpretation of small angle X-ray scattering from starch on the basis of fractals. Carbohyd. Pol. 34, 357–363 (1997).

Mistry, H. et al. Highly selective plasma-activated copper catalysts for carbon dioxide reduction to ethylene. Nat. Commun. 7, 12123 (2016).

De Ruiter, J. et al. Probing the dynamics of low-overpotential CO2-to-CO activation on copper electrodes with time-resolved Raman spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 15047–15058 (2022).

An, H. et al. Spatiotemporal mapping of local heterogeneities during electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction. JACS Au 3, 1890–1901 (2023).

Simon, G. H., Kley, C. S. & Roldan Cuenya, B. Potential-dependent morphology of copper catalysts during CO2 electroreduction revealed by in situ atomic force microscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 2561–2568 (2021).

Zhan, C. et al. Revealing the CO coverage-driven C–C coupling mechanism for electrochemical CO2 reduction on Cu2O nanocubes via operando Raman spectroscopy. ACS Catal. 11, 7694–7701 (2021).

Hayden, B. E., Kretzschmar, K. & Bradshaw, A. M. An infrared spectroscopic study of CO on Cu(111): the linear, bridging and physisorbed species. Surf. Sci. 155, 553–566 (1985).

Zhu, S., Li, T., Cai, W. Bin & Shao, M. CO2 electrochemical reduction as probed through infrared spectroscopy. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 682–689 (2019).

Li, F. et al. Molecular tuning of CO2-to-ethylene conversion. Nature 577, 509–513 (2020).

Gunathunge, C. M., Ovalle, V. J., Li, Y., Janik, M. J. & Waegele, M. M. Existence of an electrochemically Inert CO population on Cu electrodes in alkaline pH. ACS Catal. 8, 7507–7516 (2018).

Moradzaman, M. & Mul, G. In situ Raman study of potential-dependent surface adsorbed carbonate, CO, OH, and C species on Cu electrodes during electrochemical reduction of CO2. ChemElectroChem 8, 1478–1485 (2021).

An, H. et al. Sub-second time-resolved surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy reveals dynamic CO intermediates during electrochemical CO2 reduction on copper. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 16576–16584 (2021).

Chou, T. C. et al. Controlling the oxidation state of the Cu electrode and reaction intermediates for electrochemical CO2 reduction to ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 2857–2867 (2020).

Kok, J., de Ruiter, J., van der Stam, W. & Burdyny, T. Interrogation of oxidative pulsed methods for the stabilization of copper electrodes for CO2 electrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 1950–19520 (2024).

Wu, B. et al. Stable solar water splitting with wettable organic-layer-protected silicon photocathodes. Nat. Commun. 13, 4460 (2022).

Lenne, Q., Leroux, Y. R. & Lagrost, C. Surface modification for promoting durable, efficient, and selective electrocatalysts. ChemElectroChem 7, 2345–2363 (2020).

Yang, S. et al. Near-unity electrochemical CO2 to CO conversion over Sn-doped copper oxide nanoparticles. ACS Catal. 12, 15146–15156 (2022).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA: a three-dimensional visualization system for electronic and structural analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 41, 653–658 (2008).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: the materials project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Netherlands Center for Multiscale Catalytic Energy Conversion (MCEC), an NWO Gravitation program funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science of the government of the Netherlands (JdR, WvdS, main applicant BMW), NWO grant Vi.Vidi.203.031 (VRMB, main applicant FTR), and the Solar Fuels research program of the Strategic Alliance EWUU between Utrecht University, University Medical Center Utrecht, Technical University Eindhoven, and Wageningen University (WvdS, main applicant BMW). The authors acknowledge ESRF for the granted beamtime (CH6487, AVP, FTR, main applicant WvdS) and Narayanan Theyencheri (ID02, ESRF) for helpful discussions and technical assistance. Sander Deelen (Utrecht University) is acknowledged for the design of the in situ cell. Danny Broere (Utrecht University) is thanked for providing 0.1 mmol of 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.v.d.S. and F.T.R.: conceptualization and supervision of the project, data acquisition and interpretation, writing of manuscript. J.d.R. and V.R.M.B.: data acquisition and analysis, writing of manuscript. S.Y., H.W., P.T.P., G.M.: acquisition of X-ray scattering data, feedback on manuscript. J.M.D.: acquisition electron microscopy data, feedback on manuscript. B.J.d.H.: acquisition Raman data, feedback on manuscript. J.C.L.J.: in situ cell design and technical support, feedback on manuscript. A.V.P. and B.M.W.: supervision and data interpretation, feedback on manuscript

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jinlong Gong, Andreas Borgschulte, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Ruiter, J., Benning, V.R.M., Yang, S. et al. Multiscale X-ray scattering elucidates activation and deactivation of oxide-derived copper electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction. Nat Commun 16, 373 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55742-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55742-5