Abstract

The insulator-to-metal transition in VO2 has garnered extensive attention for its potential applications in ultrafast switches, neuronal network architectures, and storage technologies. However, the photoinduced insulator-to-metal transition remains controversial, especially whether a complete structural transformation from the monoclinic to rutile phase is necessary. Here we employ the real-time time-dependent density functional theory to track the dynamic evolution of atomic and electronic structures in photoexcited VO2, revealing the emergence of a long-lived monoclinic metal phase under low electronic excitation. The emergence of the metal phase in the monoclinic structure originates from the dissociation of the local V-V dimer, driven by the self-trapped and self-amplified dynamics of photoexcited holes, rather than by an electron-electron correction. On the other hand, the monoclinic-to-rutile phase transition does appear at higher electronic excitation. Our findings validate the existence of monoclinic metal phase and provide a comprehensive picture of the insulator-to-metal transition in photoexcited VO2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

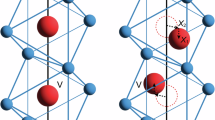

The intricate interplay of charge, spin, lattice, and orbital degrees of freedom leads to a variety of emergent phenomena in strongly correlated materials and may also create a barrier to learning their underlying mechanisms1,2,3,4,5. For instance, the insulator-to-metal transition (IMT) behaviors accompanied by a rapid, reversible structural phase transition from the monoclinic (M1) insulating phase to the rutile (R) metallic phase in vanadium dioxide (VO2)6,7,8,9,10 have gained great attention in the past three decades due to its potential applications in ultrafast switches, neuronal network architectures, and storage technologies11,12,13,14. At low temperatures, VO2 is stabilized in the M1 phase and is characterized by the Peierls V-V dimerization followed by titling to form zigzag chains (Fig. 1a, f and Supplementary Fig. 1a). As the temperature rises above 341 K, it transforms to the R phase15,16 due to the dissociation of the V-V dimers (Fig. 1d, g and Supplementary Fig. 1b). Photoexcitation using ultrafast laser pulses provides a powerful approach to investigate and manipulate the phase transition of VO2 with a timescale in the limit of atomic motion17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. It is widely acknowledged that surpassing a certain threshold of laser fluence induces the IMT in VO2, followed by a gradual lattice reorganization from the M1 phase to the R phase4,17,25,26,27,28,29, which is attributed to electron-phonon coupling30,31.

a The atomic structure of the 2 × 2 × 2 supercell for the insulating monoclinic (M1) phase. Here, V and O atoms are labeled by purple and orange balls, respectively, and the dashed gray parallelepiped represents the unit cell. The Peierls lattice distortion along the a-axis causes V-V dimerization with the bonds of the V-V dimers (with a bond length dS) and the bonds of long counterparts (with a bond length dL) represented by purple lines and gray lines, respectively. The time evolution of the real-space distribution of photoexcited holes on the (010) plane for M1-phase VO2 following (b) a strong photoexcitation and (c) a weak photoexcitation, respectively. For comparison, the initial positions of the V atoms before photoexcitation are indicated by white balls, and the photoinduced atomic driving forces on V atoms are marked by white arrows with their length indicating the relative force strength. d The corresponding 2 × 2 × 4 supercell of the metallic rutile (R) phase, in which all V-V bonds (purple lines) along the a-axis are equally distributed at dR. The blue shading indicates a 3D isosurface of the partial charge density of the bands around the Fermi level as marked in (g). e The 2 × 2 × 2 supercell structure of the metal monoclinic (MM) phase with a 3D isosurface of the partial charge density of an isolated band around the Fermi level marked in (h). The V atoms in a chain with larger displacements are labeled by Arabic numerals 1–4. The first-principles calculations predicted unfolded band structures of the M1 phase (f), the R phase (g), and the MM phase (h).

However, recent experiments have unveiled that a weaker laser fluence than the threshold required for M1-to-R phase transition can also induce the IMT, resulting from the formation of a metastable monoclinic metal (MM) phase4,11,29. Specifically, Morrison et al.4 demonstrated the instantaneous emergence of the MM phase within a picosecond lifetime by employing a combination of ultrafast electron diffraction and time-resolved infrared transmittance. Sood et al.11 further indicated that the electric drive can also induce such a long-lived MM phase in addition to photoexcitation. The emergence of this MM phase is commonly attributed to the suppression of the electron-electron correlation and the enhancement of electron-phonon coupling at lower photoexcitation4,11,29. On the other hand, Xu et al.32 refuted the existence of the MM phase, arguing that there is only one threshold for photoinduced phase transition and thus no separate threshold for this MM phase. This refutation was also supported by the absence of the MM phase in structural measurements of the femtosecond total X-ray scattering26 and optical spectra utilizing the X-ray absorption spectroscopy, broad-band optical detection28, and time- and spectrally resolved coherent X-ray imaging21. This discrepancy in the observations of the MM phase is vaguely argued to be the differences of the VO2 samples (single-crystal26,32,33 or polycrystalline4,11,29), and the overlooked differences in heat dissipation between different instruments28. Hence, it is urgent to carry out a theoretical investigation to examine the existence of the MM phase and reveal the underlying microscopic mechanism.

In this work, aimed at resolving the controversy surrounding the existence of the relatively long-lived MM phase, we employ the real-time time-dependent density functional theory (rt-TDDFT) simulations to investigate the IMT dynamic processes. Under strong photoexcitation, the photoexcited holes induce significant atomic driving forces on each V-V dimer, breaking all V-V dimers and resulting in the formation of the metallic R phase (Fig. 1b), as discussed in our previous works9. Conversely, under weak photoexcitation, the photogenerated holes are insufficient to generate the necessary atomic driving force to dissociate all V-V dimers simultaneously (Fig. 1c). However, we observe the dissociation of a specific pair of V-V dimers (labeled as V3-V4) within the supercell (Fig. 1e). This local dissociation of the V-V dimer is attributed to the transfer of photoexcited holes to the vicinity of two V atoms, amplifying the atomic driving force acting on them and causing an elongation of their bond length. Importantly, this local structural phase transition will not alter the monoclinic-phase characteristics of the overall crystal structure under the XRD measurements34,35, but, results in the localization of electronic wave function (Fig. 1e), corresponding to an isolated band crossing the Fermi level (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. 1c) and giving rise to the formation of MM phase within a picosecond lifetime. It is crucial to emphasize that the underlying MM phase is associated with the broken of local V-V dimer. This clarification sheds light on the nature of the MM phase characterized by local structural alterations in VO2, thereby enhancing our comprehension of the photoinduced IMT and laying the groundwork for future exploration in this field.

Results

Photoinduced M1-to-R phase transition

Figure 2 shows the temporal evolution of band gap, V-V bond lengths, and simulated X-ray Diffraction (XRD) of the M1-phase VO2 at 300 K following the photoexcitation at fluences corresponding to excitations of 0.79%, 0.97%, and 1.25% of valence electrons to conduction bands. These fluences are near the threshold for the conventional M1-to-R structural phase transition in VO29. One can see from Fig. 2f that, at strong photoexcitation of 1.25%, bond lengths of all V-V dimers get longer and that of their long bond counterparts get shorter immediately after the photoexcitation. At around 120 fs, these bond lengths become equally distributed at 2.74 Å, which is the V-V bond length in the R phase. After that, all bonds still vary slightly around 2.74 Å in damped oscillations. From the evolution of V-V bonds, we can identify that the VO2 system undergoes a photoinduced transition from the M1 phase to the R phase. To further confirm it, we examine the XRD pattern in which the vanishing of the 30\(\bar{2}\) Bragg peak and the slight intensity increase of the 200 and 220 peaks signify the transition from the M1 phase to the R phase4,26,29,32. Figure 2i shows that the evolution of the 200, 220, and 30\(\bar{2}\) Bragg peaks in our simulated XRD pattern based on the dynamic evolution of atom positions (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4) is consistent with the experimental measurements for photoinduced M1-to-R phase transition32. Specifically, our theoretically predicted intensity of the 30\(\bar{2}\) peak disappears completely at ~150 fs and then becomes steady without any oscillation (Fig. 2i), indicating a complete phase transition to the R phase26,32. Note that the slight differences in intensity and time scale between our simulation and experiments may arise from differences in photoexcitation strength and sample imperfection33,36. From the band structure of VO2 in the R phase (Fig. 1g), one can see that multiple energy bands intersect the Fermi level and close the band gap. Figure 2c shows that right after the photoexcitation the bandgap drops sharply and approaches zero after 50 fs, along with the crystal structure transition toward the R phase. The resulting charge modulation will further stabilize the VO2 in the R phase, giving rise to no coherent phonon oscillation between the two phases involved in the transition, which is frequently observed in the experimental literature26,32.

The dynamic evolution of the band gap at photoexcitation of η = 0.79% (a), η = 0.97% (b), η = and 1.25% (c). η represents the proportion of valence electrons photoexcited to the conduction bands. d–f the corresponding temporal dynamics of the V-V bond lengths. The red and blue dashed lines correspond to the long and short bond lengths, respectively. The average bond lengths of long and short bonds are represented by red and blue solid lines, respectively. The green, purple, and orange solid lines in (e) highlight the bonds of a local chain marked by Arabic numerals 1–4 in Fig. 1(e). g–i The corresponding time evolution of the simulated 200 (blue lines), 220 (green lines), 30\(\bar{2}\) (red lines) Bragg peaks compared with available experimental data (black circles)32.

Photoinduced MM phase

As the photoexcitation strength is reduced to 0.97% excitation, Fig. 2b illustrates that the bandgap rapidly diminishes to zero, akin to the behavior observed at 1.25% photoexcitation, indicating the presence of a long-lived metallic state. However, in this case, the bandgap then oscillates around zero, albeit with distinctions from the case at 1.25% photoexcitation. Notably, the corresponding unfolded band structure (Fig. 1h) reveals an isolated band near the Fermi level when projecting the electronic states of the VO2 system at 500 fs. Figure 1e shows that this isolated band corresponds to the electronic states highly localized on one of the V-V dimers (associated V atoms denoted as V3 and V4, respectively). Figure 2e shows that the bond length of this V-V dimer (V3-V4) and that of the corresponding long counterparts (V2-V3 and V4-V1) become equal at 110 fs and then rebound slightly with an oscillation thereafter but never recover back to their original bond lengths. Meanwhile, the remaining V-V dimers have a very small change in bond length and maintain the characteristic features of the M1 phase (Figs. 1e and 2e). The reduced intensity of the simulated 30\(\bar{2}\) peak drops by about 55% at 150 fs and then slightly recovers (Fig. 2h), exhibiting an oscillation of 6 THz consistent with the coherent phonon observed experimentally17,32,36,37,38. Therefore, we demonstrate that the formation of the metastable metallic (MM) phase under 0.97% photoexcitation is driven by a local structural transition. This finding of photoinduced metallic metastable phase arising from local atomic nucleation has been postulated very recently to explain the experimental data for the photo-susceptibility of VO239 and time-resolved harmonic spectroscopy in NbO240.

To validate the reliability of our simulations, we also perform the same simulations in a larger supercell (Supplementary Note 3). Our large supercell simulation shows that photoexcitation induces the dissociation of two adjacent V-V dimers, which is in excellent agreement with that observed in a very recent experiment41, rather than just one dimer as observed in the small supercell. It indicates homogeneous nucleation should occur in a real photoexcited system (Supplementary Fig. 7). These local dissociation around the V-V dimers act as a trapping center for excited holes and induces carrier localization (Supplementary Fig. 7d, e). The carrier localization, in turn, amplifies these distortions. This process is similar to the formation of photoexcited polarons, which are more likely to form in adjacent chains rather than along the a-axis V-V dimer direction of the M1 phase.

The existence of the MM phase has been experimentally confirmed through the analysis of changes in the transmission spectrum4. To deepen understanding, we have modified the Random Phase Approximation (RPA) method42 to calculate the absorption spectra of photoexcited states (Supplementary Note 4). We then extract the values of the absorption spectra at the photon energy \(\hslash \omega\) = 0.25 eV4 to generate the transmission spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 11). At photoexcitation of 0.97%, the infrared transmission reaches a minimum and almost remains at that value due to the long-lived existence of metallic properties with an isolated band near the Fermi level, which also aligns well with experimental results4. On the other hand, we also present the evolution of the absorption amplitude at 5 μm (~0.25 eV), 900 nm (~1.4 eV), and 690 nm (~1.8 eV) for different photoexcitation fluences (Supplementary Fig. 14), and the Fourier transformation of such optical measurement which can be related to the coherent phonon modes induced by the laser excitation. Our results reveal that the absorption amplitude at the 5 μm probe wavelength shows a sudden increase at 0.97% photoexcitation, distinct from the behavior at 900 nm and 690 nm (Supplementary Fig. 13). Such results can be tested in future experiments.

Besides, one hallmark of the MM phase observed in previous experiments on polycrystalline samples is the rapid decrease in the 30\(\bar{2}\) peak followed by a slow increase in the 200 peak4,11,29. However, this delay effect has been subjected to debate in other experiments, with the contention that it is only observed in polycrystalline samples with the separated nano domains4,11,29 and cannot be reliably detected in single crystal samples26,32,33. Our XRD dynamic evolution results do not exhibit this delay effect and closely resemble the changes observed in single crystal experiments32. Consequently, it is not rigorous to discern the occurrence of a metastable phase solely based on the delay phenomenon observed in the 200 and 30\(\bar{2}\) Bragg peaks in single crystal. XRD primarily reflects the long-range order of atoms, making it challenging to directly detect phase transitions involving localized atoms like those in our theoretical simulation. Recently, advanced transient diffuse X-ray scattering has been developed to detect local non-equilibrium lattice distortions41, which could serve as a powerful method to verify our localized phase transition. Additionally, the variation in heat dissipation among different experimental instruments complicates the simultaneous detection of electronic structure and atomic structure evolution at the same laser threshold, contributing significantly to doubts about the existence of the MM phase. According to our simulation results, the existence of the MM phase can only be detected through electronic structure analysis. Future experiments can utilize time-resolved angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy19,43,44 to discern the isolated band near the Femi level (Fig. 1h), thereby validating the presence of the MM phase.

Further reducing the photoexcitation to 0.79%, Fig. 2a shows that the magnitude of the bandgap falls sharply, approaching almost zero at 60 fs after photoexcitation, but then quickly increases to 0.3 eV followed by a damped oscillation within the range from 0.1 to 0.5 eV thereafter. Along with this behavior of bandgap, the bond lengths of the V-V dimers get longer, and their long bond counterparts get shorter, tending to their bond length of 2.74 Å in the R phase within the initial 100 fs. Before getting equal, they rebound partially with long-lived oscillations after 100 fs (Fig. 2d). Particularly, different from the above two cases of strong photoexcitation, there is no V-V bond approaching the bond length of 2.74 Å in the R phase. Figure 2g shows that our simulated XDR pattern is in excellent agreement with experimental measurements32. One can see from Fig. 2g that the 30\(\bar{2}\) peak in the simulated XDR pattern (see Supplementary Note 2 for details) exhibits a drop of ~35% in intensity with an oscillation corresponding to a 6.0 THz coherent phonon mode17,32,36,37,38, indicating that the crystal structure is still maintained in the M1 phase32. Consequently, at 0.79% photoexcitation a transient metal phase is emerging but is, however, last only for a few tens of femtoseconds.

Origin of photoinduced MM phase

We have demonstrated that the experimentally observed long-lived metallic metastable phase4,11,29 indeed exists. The fluence range of the MM phase is from 9.3 mJ/cm2(0.79% electron excitation) to 12.5 mJ/cm2 (1.25% electron excitation), with a window of 3.2 mJ/cm2 which is close to the experimental fluence window of 4 mJ/cm24,29. To reveal the mechanism underlying the local nucleation-driven metallic metastable phase near just below the threshold photoexcitation for M1-to-R phase transition, we recall the recently uncovered photoexcitation-dependent atomic driving forces for such structural phase transition9, which unifies the ordered coherent27 and disorder26 dynamics observed experimentally in photoexcited VO2. It was found9 that the photoexcited holes generate a force on each V-V dimer to drive their collective coherent motion, which is in competition with the thermal-induced random vibrations. At a very strong photo excitation, the photogenerated atomic driving forces are much larger than the atomic forces induced by thermal phonons and drive the atoms toward the M1-to-R structural phase transition direction in a deterministic way. As the photoexcitation strength is lowered approaching the threshold (e.g., 1.25% photoexcitation), the photogenerated atomic forces become comparable with the atomic forces associated with thermal phonon vibrations, making the M1-to-R structural phase transition process disordered due to V atoms being pushing away from the transition path by thermal phonon vibrations, as shown in Fig. 1b.

If the photoexcitation strength is reduced slightly below the threshold where the photogenerated atomic forces are not strong enough to drive the M1-to-R structural phase transition, a different dynamic emerges. To track the evolution of the photoexcited holes on each individual V-V dimer, we define \({p}_{\text{h}}(t)\) as the integration of electronic states located on each V-V dimer weighted by time-dependent unoccupation number \({\rho }_{V-V}(E,t)\) within a range from −1.6 eV to the Fermi level (located at 0 eV), as shown in Fig. 3b, c: \({p}_{\text{h}}(t)={\int }_{\text{-}1.6\text{eV}}^{0}{\rho }_{V-V}(E,t){dE}\). Figure 3a shows\(\,{p}_{\text{h}}(t)\) for different V-V dimers. One can see that all \({p}_{\text{h}}(t)\) increase at a nearly equal rate at the initial 30 fs arising from the photoexcitation by a laser pulse. After that, they tend to have a relatively steady value for V-V dimers except for the V3-V4 dimer, which gets larger even after the photoexcitation (see also Fig. 3b). It implies that the enhanced part of photoexcited holes on the V3-V4 dimer relative to the remaining V-V dimers should arise from a transfer from its nearby area (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 15a). It has been revealed that the electron-phonon coupling-induced self-amplification process creates homogeneous atomic nucleation in photoinduced nonthermal melting in Si45. Figure 3d schematically shows that the thermal phonon vibrations could induce a local maximum, say at the V3-V4 dimer, in the energy landscape of the valence band edge according to the deformation potential theory originally developed by Bardeen and Shockley46. This local maximum renders the V3-V4 dimer as a hole-trapping center to capture more photoexcited holes from its vicinity, as shown in Fig. 3b and diagramed in Fig. 3d, which further enhances the atomic force on the V3-V4 dimer alone, as shown in Fig. 1c. Larger atomic force drives the bond length of the V3-V4 dimer longer than the remaining V-V dimers to have a deeper potential well for holes, as shown in Fig. 3a and schematically diagramed in Fig. 3d. The deeper well can capture more holes and so on, forming a self-amplification process induced by electron-phonon coupling. Such a self-amplification process successively upraises the bonding state band of the V3-V4 dimer and increases the number of localized holes on the V3-V4 dimer, as shown in Fig. 3a, yielding a sufficient strong atomic force to dissociate the V3-V4 dimer but sustaining the remaining V-V dimers. Such self-amplified local distortion generates atomic nucleation, which is responsible for the emergence of the long-lived MM phase as observed in the simulation case of 0.97% photoexcitation (as shown in Fig. 1c and Fig. 2b) and experimentally measurements4,11,29. Besides, such pre-existing local V-V defects in the actual systems are likely to be beneficial for the formation and stability of the MM phase. Thus, in the polycrystalline phase with separated nanodomains, it is possible that photoexcited holes are more easily to be trapped by the existing structural distortions to have a phonon-assisted self-amplification for local nucleations so that a lower photoexcitation is required for the monoclinic metallic phase. Whereas in single crystalline VO2, these local atomic nucleations are homogeneously distributed in the area under the photoexcitation, giving rise to a uniform transition to a monoclinic metallic phase. Note that this photoinduced local atomic nucleation is a bit like the formation of polarons, which has been identified as the main factor that causes the metallic states as reported in other materials such as in Nd2CuO447 and BaBiO348,49. It will be extremely helpful to use the experimental technique used in photoexcited polarons observation50,51,52,53, such as the transient extreme-ultraviolet spectroscopy on an ultrafast timescale, to probe the MM phase in VO2.

a The evolution of photoexcited holes on V-V dimers at electronic excitations of 0.97% within −1.6−0 eV below the Fermi Level. The V3-V4 dimer is represented in a solid blue line, and other V-V dimers are illustrated in dashed blue lines. b, c The projected density of states (PDOS) of V3-V4 dimer (b) and other V-V dimers (c) from TDDFT simulations at different times. Red (blue) shaded areas represent the distributions of photoexcited electrons (holes). d The schematic diagram of the self-trapping and self-amplified dynamics. The red solid circles and blue hollow circles represent photoexcited electrons and holes, respectively. The movement of the V atom is shown with purple circles. The yellow shading indicates the V-O band.

Because electron-phonon coupling plays a central role in such self-amplification processes, such photoinduced atomic nucleation is naturally dependent on both photoexcited holes and thermal phonons. Supplementary Fig. 19b shows that if the initial temperature of VO2 lowers to 100 K to suppress the thermal phonon vibrations, the photoinduced local atomic nucleation does not appear, and the photoexcited holes and atomic driving force are almost evenly distributed at all V-V dimers. On the other hand, if we lower the photoexcitation to 0.79% excitation, a certain V-V dimer can only capture more photoexcited holes by tens of femtoseconds but is insufficient to dissociate corresponding V-V dimer (Supplementary Fig. 18). Figure 2a shows that this transient capture of photoexcited holes results in the instantaneous collapse of bandgap (emergence of a metallic state) followed by a rapid recovery process (see also Supplementary Fig. 18). Furthermore, when considering only the effect of temperature and excluding the influence of forces from photoexcited holes, we did not observe the formation of a stable MM phase (Supplementary Note 6). The change of V-V bond lengths and the reduction of band gap have the same trend with temperature (Supplementary Fig. 20), which aligns with previous findings54. Notably, our current rt-TDDFT simulations do not account for carrier cooling processes, which lead to lattice heating. This lattice heating, occurring after a few hundred femtoseconds, may influence the local phase transition. The effect of hot carrier cooling will be addressed in our future work.

Electron-electron interaction and electron-phonon coupling

Although we have demonstrated the IMT in the M1 structure being driven by the structural change in the atomistic structure, it is also worth examining the photoinduced electron correlation effect on the bandgap. Whether IMT in VO2 can be classified as a Mott-type transition is a controversial topic5,55,56. This is particularly interesting considering the experimental approaches are difficult to access the electron correlation effect alone due to the ever existence of electron-phonon coupling in the system. Here, we investigate this question theoretically using rt-TDDFT simulations by freezing the atomic positions, thus turning off the electron-phonon coupling. Figure 4 shows that the bandgap of M1 phase VO2 gets smaller linearly even without structural change by increasing the photoexcitation strength, indicating the effect of electron correlation effect on the bandgap. The bandgap collapses completely at a strong photoexcitation of about 3.75% valence electrons pumped into the conduction bands, indicating that the photoexcitation threshold for the transition to the metal phase driven by the electron correlation is much higher than that driven by the local nucleation (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 1, Fig. 2c, d) and thus latter is preferred in the competition between these two mechanisms. This predicted threshold for the photoinduced Mott-type transition is even higher than that for the conventional M1-to-R phase transition at 1.25% excitation in VO2.

Discussion

In summary, our rt-TDDFT simulation confirms the existence of experimentally observed long-lived MM phase in VO24,11,29 under photoexcitation slightly weaker than the threshold for the M1-to-R structural transition. Specifically, under a strong photoexcitation above the threshold for the M1-to-R structural transition, the photoexcited holes occupied the bonding state band of the V-V dimers to generate an atomic driving force on each V-V dimer to elongate its bond until the dimer is completely dissociated9, and the dissociation of all V-V dimers results in the transition to the metallic R phase (Fig. 1b). Conversely, under weak photoexcitation, the photogenerated holes are insufficient to generate the necessary atomic driving force to dissociate all V-V dimers simultaneously (Fig. 1c). However, we observe that one of V-V dimers in the supercell experience slight stretching due to the influence of thermal phonons (Fig. 3d). This subtle displacement induces the transfer of photoexcited holes to the vicinity of two V atoms, amplifying the atomic driving force acting on them to further stretch their bond length. The process increases the local well depth and can trap more holes from the vicinity, creating a self-amplified and self-trapped process. This interplay between photoexcited holes, atomic driving forces, and V-V dimer displacement initiates a self-amplification in the dynamical process, eventually leading to the complete dissociation of a pair of V-V dimers leaving the remaining dimers intact. The localized effect observed in the MM phase contributes to its relatively long-lived lifetime, which justifies its appropriate assignment as an IMT phase based on electronic structure analysis. In contrast to prior literature assuming no structural changes, we demonstrate that the emergence of a metallic state in the M1 phase arises from the local atomic nucleation, which is consistent with very recent experimental evidence observed in VO239 and NbO240. From the view of the photogenerated atomic driving force, we develop a unified understanding of both photoinduced M1-to-R phase transition at strong photoexcitation and M1-to-MM phase transition at low photoexcitation.

Therefore, we have illustrated that the photoinduced transient MM phase in VO2 arises from the phonon-assisted self-amplification of interatomic forces, which drive local atomic distortions and local phase transition under a photoexcitation below the threshold for the M1-to-R structural phase transition. This new mechanism is also applicable to NbO2 where a local nucleation growth has also been suggested to account for the ultrafast metallization process based on the time-resolved harmonic spectroscopy40. Particularly, our theory is even applicable to broad classes of materials not just strongly correlated materials, considering the phonon-assisted self-amplification of driving forces has been found to generate the homogeneous nucleation for the photoexcitation-induced nonthermal melting of Si45. The local atomic nucleation instead of electronic correlation responsible for the transient metallization offers advantages and disadvantages for potential applications. For instance, the electrons in the transient metallization are highly localized in real space, which will benefit the development of subnanoscale high-dense devices, but will degrade the carrier transport in nanoscale devices. The local atomic nucleation mechanism enables the possibility of precise manipulation of local phase transition and thus holds promise for significantly enhancing energy efficiency and accelerating the high-speed optoelectronic devices.

Methods

All calculations were performed using the ab initio package PWmat57, incorporating the local density approximation functional (LDA) + U exchange-correlation58. Our simulation model comprised a 96-atom supercell, employing a plane-wave basis with a cutoff energy of 45 Ry. The total energy and eigenvalues convergence criteria were set as 2 × 10−3 eV and 1 × 10−4 eV. To ensure accurate Brillouin-zone sampling, a 2 × 2 × 2 Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh was utilized. A Hubbard U value of 3.4 eV for V 3 d states was employed, yielding a bandgap of ~0.67 eV for M1-VO2 (Fig. 1f), consistent with the experimentally observed value4,10.

The atomic configuration was equilibrated for 1 ps using a time step of 1 fs at 300 K in the NVE ensemble during BOMD simulations. Selecting the thermally equilibrated structure at 300 K as the initial configuration for TDDFT calculations. To simulate photoinduced IMT dynamics, the time-space external field can be described as a Gaussian shape,

where we selected photon energy of \(\hslash \omega\) = 1.55 eV, consistent with experimental parameters4,28, a time delay of \({t}_{0}\) = 25 fs, and a width parameter \(\sqrt{2}\sigma\) = 10 fs. The electric field is adjusted to E0 = 0.054, 0.108, 0.162, 0.183, and 0.215 \({\rm{V}}/{\text{\AA}}\) at 300 K to attain electronic excitations of 0.11%, 0.39%, 0.79%, 0.97% and 1.25% in free structure. When frozen structure, the laser fluence is set to E0 = 0.054, 0.108, 0.162, 0.183, 0.215, 0.323, 0.431, and 0.539 \({\rm{V}}/{\text{\AA}}\) to achieve electronic excitations of 0.11%, 0.39%, 0.79%, 0.97%, 1.25%, 2.10%, 3.00%, and 3.75%, as illustrated in Suppl. Figure 2a, b.

It has been found that the photoexcitation can induce a change of the Hubbard U value59, we also examine the photoexcitation-induced change of U value and assess its effect on phase transition in VO2. Our results show that the U value first decreases from 3.4 to 3.25 eV and then saturates at 3.25 eV with increasing the photoexcitation strength (Supplementary Fig. 21), consistent with reference59. We perform the rt-TDDFT simulations with an even lower U value (U = 3.0 eV) and find that this smaller U value has similar results as U = 3.4 eV, implying that the mechanism responsible for the emergence of MM phase in VO2 is rather than the mechanism of electronic correlation. Therefore, we can safely neglect the effect of photoexcitation-induced U change (see Supplementary Note 7).

Data availability

The results data used for the plotting of the Figures generated in this study have been deposited in the figshare database with the identifier [data https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27791184]60 The raw DFT data generated in this study are available upon restricted access for due to size considerations, access can be obtained by request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

The rt-TDDFT CODE has been integrated into the PWmat package. The PWmat software can also be accessed directly from http://www.pwmat.com.

References

Imada, M., Fujimori, A. & Tokura, Y. Metal-insulator transitions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 1039 (1998).

Yang, Z., Ko, C. & Ramanathan, S. Oxide electronics utilizing ultrafast metal-insulator transitions. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 41, 337–367 (2011).

Jager, M. F. et al. Tracking the insulator-to-metal phase transition in VO2 with few-femtosecond extreme UV transient absorption spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9558–9563 (2017).

Morrison, V. R. et al. A photoinduced metal-like phase of monoclinic VO2 revealed by ultrafast electron diffraction. Science 346, 445–448 (2014).

Wegkamp, D. & Stähler, J. Ultrafast dynamics during the photoinduced phase transition in VO2. Prog. Surf. Sci. 90, 464–502 (2015).

Arcangeletti, E. et al. Evidence of a pressure-induced metallization process in monoclinic VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 196406 (2007).

Liu, M. et al. Terahertz-field-induced insulator-to-metal transition in vanadium dioxide metamaterial. Nature 487, 345–348 (2012).

O’Callahan, B. T. et al. Inhomogeneity of the ultrafast insulator-to-metal transition dynamics of VO2. Nat. Commun. 6, 6849 (2015).

Liu, H.-W. et al. Unifying the order and disorder dynamics in photoexcited VO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2122534119 (2022).

Shao, Z. et al. Recent progress in the phase-transition mechanism and modulation of vanadium dioxide materials. NPG Asia Mater. 10, 581–605 (2018).

Sood, A. et al. Universal phase dynamics in VO2 switches revealed by ultrafast operando diffraction. Science 373, 352–355 (2021).

Li, G. et al. Photo-induced non-volatile VO2 phase transition for neuromorphic ultraviolet sensors. Nat. Commun. 13, 1729 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Xiong, W., Chen, W. & Zheng, Y. Recent progress on vanadium dioxide nanostructures and devices: fabrication, properties, applications and perspectives. Nanomaterials 11, 338 (2021).

Park, J. H. et al. Measurement of a solid-state triple point at the metal-insulator transition in VO2. Nature 500, 431–434 (2013).

Morin, F. J. Oxides which show a metal-to-insulator transition at the Neel temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 3, 34 (1959).

Berglund, C. N. & Guggenheim, H. J. Electronic properties of VO2 near the semiconductor-metal transition. Phys. Rev. 185, 1022 (1969).

Wall, S. et al. Ultrafast changes in lattice symmetry probed by coherent phonons. Nat. Commun. 3, 721 (2012).

Frigge, T. et al. Optically excited structural transition in atomic wires on surfaces at the quantum limit. Nature 544, 207–211 (2017).

Nicholson, C. W. et al. Beyond the molecular movie: dynamics of bands and bonds during a photoinduced phase transition. Science 362, 821–825 (2018).

Chávez-Cervantes, M. et al. Charge density wave melting in one-dimensional wires with femtosecond subgap excitation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 036405 (2019).

Johnson, A. S. et al. Ultrafast X-ray imaging of the light-induced phase transition in VO2. Nat. Phys. 19, 215–220 (2023).

Disa, A. S. et al. Photo-induced high-temperature ferromagnetism in YTiO3. Nature 617, 73–78 (2023).

Afanasiev, D. et al. Ultrafast control of magnetic interactions via light-driven phonons. Nat. Mater. 20, 607–611 (2021).

Zong, A., Nebgen, B. R., Lin, S.-C., Spies, J. A. & Zuerch, M. Emerging ultrafast techniques for studying quantum materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 224–240 (2023).

Tao, Z. et al. The nature of photoinduced phase transition and metastable states in vanadium dioxide. Sci. Rep. 6, 38514 (2016).

Wall, S. et al. Ultrafast disordering of vanadium dimers in photoexcited VO2. Science 362, 572–576 (2018).

Baum, P., Yang, D.-S. & Zewail, A. H. 4D visualization of transitional structures in phase transformations by electron diffraction. Science 318, 788–792 (2007).

Vidas, L. et al. Does VO2 host a transient monoclinic metallic phase? Phys. Rev. X 10, 031047 (2020).

Otto, M. R. et al. How optical excitation controls the structure and properties of vanadium dioxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 450–455 (2019).

Haverkort, M. W. et al. Orbital-assisted metal-insulator transition in VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 196404 (2005).

Biermann, S., Poteryaev, A., Lichtenstein, A. I. & Georges, A. Dynamical singlets and correlation-assisted Peierls transition in VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 026404 (2005).

Xu, C. et al. Transient dynamics of the phase transition in VO2 revealed by mega-electron-volt ultrafast electron diffraction. Nat. Commun. 14, 1265 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Direct detection of V-V atom dimerization and rotation dynamic pathways upon ultrafast photoexcitation in VO2. Phys. Rev. X 12, 021032 (2022).

de la Peña Muñoz, G. A. et al. Ultrafast lattice disordering can be accelerated by electronic collisional forces. Nat. Phys. 19, 1489–1494 (2023).

Sun, X., Sun, S. & Ruan, C.-Y. Toward nonthermal control of excited quantum materials: framework and investigations by ultrafast electron scattering and imaging. C. R. Phys. 22, 1–59 (2021).

Yuan, X., Zhang, W. & Zhang, P. Hole-lattice coupling and photoinduced insulator-metal transition in VO2. Phys. Rev. B 88, 035119 (2013).

Horstmann, J. G. et al. Coherent control of a surface structural phase transition. Nature 583, 232–236 (2020).

Cavalleri, A., Dekorsy, T., Chong, H. H. W., Kieffer, J.-C. & Schoenlein, R. W. Evidence for a structurally-driven insulator-to-metal transition in VO2: a view from the ultrafast timescale. Phys. Rev. B 70, 161102 (2004).

Sternbach, A. J. et al. Inhomogeneous photo susceptibility of VO2 films at the nanoscale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 186903 (2024).

Nie, Z. et al. Following the nonthermal phase transition in niobium dioxide by time-resolved harmonic spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 243201 (2023).

Johnson, A. S. et al. All-optical seeding of a light-induced phase transition with correlated disorder. Nat. Phys. 20, 970–975 (2024).

Hu, S. et al. Optical properties of Mg-doped VO2: absorption measurements and hybrid functional calculations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 201902 (2012).

Rettig, L. et al. Persistent order due to transiently enhanced nesting in an electronically excited charge density wave. Nat. Commun. 7, 10459 (2016).

Zong, A. et al. Evidence for topological defects in a photoinduced phase transition. Nat. Phys. 15, 27–31 (2019).

Liu, W.-H., Luo, J.-W., Li, S.-S. & Wang, L.-W. The seeds and homogeneous nucleation of photoinduced nonthermal melting in semiconductors due to self-amplified local dynamic instability. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn4430 (2022).

Bardeen, J. & Shockley, W. Deformation potentials and mobilities in non-polar crystals. Phys. Rev. 80, 72 (1950).

Liu, Q. et al. Electron doping of proposed kagome quantum spin liquid produces localized states in the band gap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 186402 (2018).

Cava, R. J. et al. Superconductivity near 30 K without copper: the Ba0. 6K0. 4BiO3 perovskite. Nature 332, 814–816 (1988).

Franchini, C., Kresse, G. & Podloucky, R. Polaronic hole trapping in doped BaBiO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 256402 (2009).

Carneiro, L. M. et al. Excitation-wavelength-dependent small polaron trapping of photoexcited carriers in α-Fe2O3. Nat. Mater. 16, 819–825 (2017).

Biswas, S., Husek, J., Londo, S. & Baker, L. R. Highly localized charge transfer excitons in metal oxide semiconductors. Nano Lett. 18, 1228–1233 (2018).

Porter, I. J. et al. Photoexcited small polaron formation in goethite (α-FeOOH) nanorods probed by transient extreme ultraviolet spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 4120–4124 (2018).

Pastor, E. et al. Electronic defects in metal oxide photocatalysts. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 503–521 (2022).

Budai, J. D. et al. In situ X-ray microdiffraction studies inside individual VO2 microcrystals. Acta Mater. 61, 2751 (2013).

Wentzcovitch, R. M., Schulz, W. W. & Allen, P. B. VO2: peierls or Mott-Hubbard? A view from band theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 3389 (1994).

Pouget, J.-P. Basic aspects of the metal-insulator transition in vanadium dioxide VO2: a critical review. C. R. Phys. 22, 37–87 (2021).

Jia, W. et al. The analysis of a plane wave pseudopotential density functional theory code on a GPU machine. Comput. Phys. Commun. 184, 9–18 (2013).

Budai, J. D. et al. Metallization of vanadium dioxide driven by large phonon entropy. Nature 515, 535–539 (2014).

Tancogne-Dejean, N., Sentef, M. A. & Rubio, A. Ultrafast modification of Hubbard U in a strongly correlated material: ab initio high-harmonic generation in NiO. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 097402 (2018).

Guo, F.-W. et al. Photoinduced hidden monoclinic metallic phase of VO2 driven by local nucleation Data sets. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27791184 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grant Nos. 11925407, 61927901, 12474076, 12204470, and 12174380, the Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, CAS under Grant No. ZDBS-LY-JSC019, CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research under Grant No. YSBR-026, the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences under Grant No. XDB43020000, the key research program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences under Grant No. ZDBS-SSW-WHC002, and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant No. 2022M723073.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.G. performed the TDDFT simulations and prepared the figures with the help of W.L. F.G. and W.L. conducted the analysis, and discussion, and wrote the manuscript. J.L. and L.W. proposed the research project, established the project direction, and revised the paper with input from F.G., W.L., and Z.W. participated in the discussion. F.G., W.L., Z.W., S.L., L.W., and J.L. contributed to the analysis and discussion of the data. F.G. and W.L. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Simon Wall and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, FW., Liu, WH., Wang, Z. et al. Photoinduced hidden monoclinic metallic phase of VO2 driven by local nucleation. Nat Commun 16, 94 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55760-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55760-3