Abstract

Halorhodospira (Hlr.) halophila strain BN9622 is an extremely halophilic and alkaliphilic phototrophic purple sulfur bacterium isolated from a hypersaline lake in the Libyan Desert whose total salinity exceeded 35% at pH 10.7. Here we present a cryo-EM structure of the native LH1–LH2 co-complex from strain BN9622 at 2.22 Å resolution. Surprisingly, the LH1–LH2 co-complex consists of a double-ring cylindrical structure with the larger LH1 ring encircling a smaller LH2 ring. The Hlr. halophila LH1 contains 18 αβ-subunits and additional bacteriochlorophyll a (BChl a) molecules that absorb maximally at 797 nm. The LH2 ring is composed of 9 αβ-subunits, and the BChl a molecules in the co-complex form extensive intra- and inter-complex networks to allow near 100% efficiency of energy transfer to its surrounding LH1. The additional LH1-B797 BChls a are located in such a manner that they facilitate exciton transfer from monomeric BChls in LH2 to the dimeric BChls in LH1. The structural features of the strain BN9622 LH1–LH2 co-complex may have evolved to allow a minimal LH2 complex to maximize excitation transfer to the core complex and effectively harvest light in the physiologically demanding ecological niche of this purple bacterium.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The major photosynthetic apparatus of purple phototrophic bacteria (Proteobacteria) comprises two distinct pigment-protein complexes: the light-harvesting (LH) complex and the reaction center (RC). While RCs among purple phototrophs are structurally highly conserved and display similar spectroscopic properties, LH complexes exhibit extensive diversity in both structure and spectral properties1. All purple phototrophic bacteria contain a core light-harvesting (LH1) complex composed of an array of α- and β-polypeptides (plus γ-polypeptides in certain species), bacteriochlorophyll (BChl), and carotenoids, with the subunit number in a given complex ranging from 10 to 17 per RC. Some species of purple sulfur bacteria contain multiple αβ-polypeptides2,3,4. All LH1 complexes with known structures of purple phototrophs surround one or two RCs forming a closed (O-shaped) or open (C-, S-, crescent-shaped) ring structure and contain a single layer of BChl molecules3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Absorption spectra of these LH1 complexes reveal a redshifted band (Qy transition) ranging from 865 nm to 960 nm for BChl a-containing species and from 1006 nm to 1016 nm for BChl b-containing species1.

A second type of LH complex termed the peripheral light-harvesting (LH2) complex is present in some but not all purple phototrophs and is typically much more abundant than LH1. Similar to LH1, LH2 complexes also consist of a structural subunit composed of one pair of αβ-polypeptides, three BChls, and one carotenoid arranged in a circular structure22,23,24,25,26,27. However, differing from LH1, LH2 complexes contain two layers of BChl a that have different absorption maxima (around 800 nm and 850 nm, respectively) and have smaller ring sizes of 7 to 9 subunits. In photosynthetic membranes, LH2 complexes are typically located in the periphery of LH1–RC core complexes as observed by atomic force microscopy28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 and are arranged to optimize the transfer of excitation energy to the nearby LH1 complexes.

The LH complexes from extremophilic purple phototrophs have developed specific mechanisms for stabilizing photocomplexes to environmental extreme(s), and this can be seen in the LH1 complexes from several thermophilic purple phototrophs. For example, the LH1 complex from the purple sulfur bacterium Thermochromatium (Tch.) tepidum incorporates Ca2+ to form an extensive and tight Ca2+-binding network near the BChl a-coordinating sites, thus stabilizing the LH1 ring structure to heat6,8,37; a similar strategy is employed by the slightly less thermophilic purple sulfur bacterium Allochromatium tepidum4,38. By contrast, the LH1 complex from the BChl b-containing mildly thermophilic purple nonsulfur bacterium Blastochloris (Blc.) tepida may adopt alternative strategies in order to increase thermostability39.

Several extremely halophilic (growth optimum >15% NaCl) purple sulfur bacteria are known, and some species require more than just high levels of salt for optimal growth, being double, or even triple extremophiles. Such phenotypes raise obvious questions about how photocomplexes function under these unusual environmental conditions. Here, we explore this question by revealing the cryo-EM structure of the distinct LH1–LH2 co-complex from the alkaline salt lake purple sulfur bacterium Halorhodospira (Hlr.) halophila strain BN962240,41, one of the most halophilic of all known Bacteria42. The conjoined LH1–LH2 structure forms a double-ring supercomplex with the enlarged LH1 ring completely encircling the smaller LH2. This heretofore unseen photocomplex topology exhibits energy transfer from LH2 to LH1 at near 100% efficiency and may be a special modification necessary for photosynthesis to proceed under the unusually harsh environmental conditions in which Hlr. halophila thrives.

Results

In the detergent-solubilized photocomplexes from Hlr. halophila intracytoplasmic membranes (ICM), the LH1–LH2 co-complex coexisted with a supercomplex formed by LH1, the RC, and a high-potential iron–sulfur protein (HiPIP), and an HiPIP-free LH1–RC complex. These photocomplexes could not be completely separated by either sucrose density gradient centrifugation or NaCl-eluted DEAE chromatography (or by sequential treatments with both methods) to yield sufficient quantities of individual complexes for structural analysis, although a small amount of highly purified LH1–LH2 co-complex was obtained that was used for spectroscopic measurements (Supplementary Fig. 1b). As a result, a mixture of the LH1–LH2, LH1–RC and LH1–RC–HiPIP complexes was subjected to cryo-EM single-particle analysis, and all of these complexes were identified from computational image analyses (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). Here we focus on the structure description of the co-complex; structural features of the Hlr. halophila LH1–RC–HiPIP supercomplex will be presented elsewhere43.

Structural overview of the LH1–LH2 co-complex

The cryo-EM structure of the Hlr. halophila LH1–LH2 co-complex was determined at 2.22 Å resolution (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs. 2–4, Supplementary Table 1). The co-complex exhibited a multi-layered concentric organization with the larger LH1 ring spatially encircling the smaller LH2 ring (Fig. 1a). The LH1 complex consists of eighteen LH1 αβ-subunits, the largest subunit number known in purple bacterial LH1 complexes, with the LH1 β-polypeptides positioned on the outermost surface of the LH1 ring spanning 120 Å in diameter. The LH2 complex is composed of nine LH2 αβ-subunits with its outermost surface (70 Å diameter) formed from LH2 β-polypeptides that are fitted into the LH1 inner ring (78 Å diameter) of α-polypeptides. Transmembrane domains of the LH1 and LH2 have similar lengths and are aligned on the same plane with the same orientations: N-termini on the cytoplasmic side and C-termini on the periplasmic side (Fig. 1b). Phospholipids (presumably phosphatidylglycerol, PG) were identified in the spaces between LH1 β-polypeptides (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 5a).

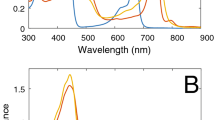

a Top view of the co-complex from the periplasmic side. b Side view of the co-complex. c Tilted view of BChl a and carotenoids in the co-complex. Color scheme: LH1-α, green; LH1-β, blue; LH2-α, cyan; LH2-β, magenta; BChl a, red sticks; carotenoids, yellow sticks; lipids, wheat sticks. d Room-temperature absorption spectra of the highly purified LH1–LH2 co-complex (black solid line) and the DEAE chromatographic fraction (black dotted line) used for cryo-EM analysis. The two spectra were normalized at 883 nm. Inset shows the Qy region of the 77 K absorption spectrum of the highly purified LH1–LH2.

Hlr. halophila LH1 and LH2 complexes both contain two layers of BChl a molecules (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 6). One layer is formed by the essentially monomeric (isolated) BChls with longer BChl–BChl distances that do not overlap each other while the second layer is formed by dimeric BChls with extensive overlap and strong coupling between their bacteriochlorins. The LH1 complex contained 36 dimeric and 9 monomeric BChls a while the LH2 complex contained 18 dimeric and 9 monomeric BChls a. Each LH1 and LH2 complex also contained nine spirilloxanthins (Fig. 1c), the dominant carotenoid in Hlr. halophila (Supplementary Fig. 5b). The monomeric BChls a in LH1 and LH2 adopt different orientations: the LH1 bacteriochlorin planes are virtually parallel to those of the dimeric BChls a, whereas the LH2 bacteriochlorin planes are essentially perpendicular to those of the dimeric BChls a (Supplementary Fig. 6). Based on analogies to the relationships between pigment arrangement and spectroscopic behavior for typical LH19,12 and LH222,23,27 complexes of phototrophic Proteobacteria and the LH complexes from species of different bacterial phyla, such as Roseiflexus (Rof.) castenholzii44 and Gemmatimonas (Gem.) phototrophica45, the dimeric BChls a in the Hlr. halophila LH1 and LH2 exhibit Qy bands at 883 nm and 835 nm, respectively, at room temperature. By contrast, the monomeric BChls a in Hlr. halophila LH1 and LH2 all yield a Qy band at 797 nm (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Data 1). Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of the Hlr. halophila LH1–LH2 co-complex yielded signals with the signature pattern of − +, + −, and + − with increasing wavelength (Supplementary Fig. 1c), corresponding to the absorption bands at 797 nm, 835 nm, and 883 nm, respectively. The latter two signals are consistent with the CD signs of the dimeric BChls a in LH2 and LH1, respectively. At 77 K, a shoulder was observed at 792 nm in the absorption spectrum (Fig. 1d, inset) that is likely the Qy band of the LH1 monomeric BChls a. Notably, the LH1 dimeric BChls a showed a significant redshift to 902 nm at 77 K. Hereafter, unless otherwise stated, the monomeric BChls a in LH1 and LH2 are termed LH1-B797 and LH2-B797, respectively, and the dimeric BChls a in LH1 and LH2 termed LH1-B883 and LH2-B835, respectively, based on their room temperature Qy maxima.

LH1 of the Hlr. halophila co-complex

Two forms of the Hlr. halophila LH1 α- and β-polypeptides were identified from the cryo-EM density map based on their different amino acid sidechains. These correspond to α1 and β1 polypeptides encoded by the genes pufA1 and pufB1, respectively, in the puf operon, and α2 and β2 polypeptides encoded by a second pair of pufA2B2 in the Hlr. halophila gene cluster encoding LH2 αβ-polypeptides (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The α1/β1- and α2/β2-pairs are positioned adjacent to each other in the LH1 ring forming an alternating arrangement with a total of nine sets for each pair (Fig. 2a). In the cryo-EM structure, 18–23 residues in the C-termini of all LH1 polypeptides and 6 residues in the N-termini of β1- and β2-polypeptides were not observed in the cryo-EM map (Fig. 2e) presumably due to posttranslational truncation and/or structural disorders. Amino acid sequences in the transmembrane regions showed 59% identity for the α1/α2 and 70% identity for the β1/β2-pairs (Fig. 2e).

a Tilted view of the LH1 complex looking from the periplasmic side. Polypeptides are shown by cylindrical cartoons and pigments are shown by sticks. Color scheme: α1, green; β1, blue; α2, orange; β2, gray; BChl a, red; carotenoids, yellow. b Tilted view of the pigments in LH1 with representative distances (in Å) between the BChls a. For clarity, phytol chains are omitted. c BChl a-binding sites in an α1/β1 subunit showing hydrogen bondings around C3-acetyl groups of the dimeric BChls a and C131-carbonyl group of the monomeric BChl a. d BChl a-binding sites in an α2/β2 subunit showing hydrogen bondings around C3-acetyl groups of the dimeric BChls a. A nearby spirilloxanthin (Spx) is shown by a yellow stick. e Sequence alignments between α1 and α2 and between β1 and β2. Red letters: BChl a-coordinating His residues; magenta letters: hydrogen-bonding residues; light-gray letters: invisible residues. Symbol scheme: (*) identical, (.) similar, (:) highly similar. The underlined regions represent predicted membrane-spanning domains.

Thirty-six dimeric BChls a (LH1-B883) in the Hlr. halophila LH1 form a partially overlapping ring on the periplasmic side with average Mg–Mg distances of 9.3 Å within a dimer and 8.4 Å between dimers (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table 2). The nine monomeric BChls a (LH1-B797) are located on the cytoplasmic side with a Mg–Mg distance of 34.3 Å and presumably absorb at 792 nm at 77 K (Fig. 1d, inset) because of their long spacings. The closest Mg–Mg distance between a monomeric BChl a and a nearby dimeric BChl a is 15.7 Å (Fig. 2b), and orientation of the monomeric bacteriochlorins is similar to that of the dimeric BChls a (Supplementary Fig. 6); this indicates that exciton couplings can occur between these pigments with the capability of transferring exciton energy from the LH1-B797 to LH1-B883. It is noteworthy that the relative orientation of the monomeric bacteriochlorins with respect to that of the dimeric BChls a in Hlr. halophila LH1 differs from those of the monomeric BChls a in the LH complexes from both Rof. castenholzii44 and Gem. phototrophica45 (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Each Hlr. halophila α1/β1-pair binds two dimeric BChls a with α1-His29 and β1-His37 residues, and the α1-polypeptide binds an additional monomeric BChl a with its His18 residue in the N-terminal region (Fig. 2c). The α1-His18 is replaced by a Phe at the same position in the α2-polypeptide and is thus unable to bind a BChl a (Fig. 2e). In addition, the C3-acetyl group in the dimeric BChl a forms a hydrogen bond with α1-Trp40 or β1-Trp46 of its associated polypeptide. No such hydrogen bond forms for the monomeric BChl a but instead, a hydrogen bond is formed between the C131-carbonyl group of BChl a and a nearby α1-Tyr10 (Fig. 2c). Each α2/β2-pair binds two dimeric BChls a through α2-His29 and β2-His37 and forms hydrogen bonds with the BChl a C3-acetyl group through α2-Trp40 and β2-Trp46 (Fig. 2d). Molecules of spirilloxanthins are primarily spanned between the α2- and β2-polypeptides (Fig. 2d), whereas this position is occupied by monomeric BChl a in the α1/β1-pair (Fig. 2c). Comparison of the Hlr. halophila LH1 α1/β1-pair with the α/β-subunit of Gem. phototrophica LHh complex45 reveals that although their overall structures are similar (Supplementary Fig. 8), apparent differences exist in their hydrogen-bonding patterns. All Hlr. halophila LH1 dimeric BChls a form hydrogen bonds between the BChl a C3-acetyl groups and nearby Trp residues (Fig. 2c, d). By contrast, such hydrogen bonds are absent from the α-polypeptide-bound B816 BChls a in Gem. phototrophica. Differences in hydrogen bonding and Mg–Mg distance may explain the different absorption behavior between the Hlr. halophila LH1 dimeric BChls a (~883 nm) and the Gem. phototrophica LHh complex (~816 nm).

LH2 of the Hlr. halophila co-complex

The cryo-EM structure revealed that the Hlr. halophila LH2 is composed of nine copies of a single αβ-pair of polypeptides associated with two dimeric BChls a, one monomeric BChl a, and one spirilloxanthin (Fig. 3a). Twenty-two residues in the C-terminus of the LH2 α-polypeptide, one residue in the C-terminus and nine residues in the N-terminus of the LH2 β-polypeptide were invisible in the cryo-EM density map (Fig. 3e). The central hole formed by the inner α-polypeptides is filled by a double-layer of structured phospholipids (Supplementary Fig. 9). The eighteen dimeric BChls a (LH2-B835) form a partially overlapping ring on the periplasmic side of the membrane with average Mg–Mg distances of 9.7 Å within a dimer and 8.6 Å between dimers (Fig. 3b). The nine monomeric BChls a (LH2-B797) are located on the cytoplasmic side with a Mg–Mg distance of ~21.0 Å. The Mg–Mg distances between a monomeric BChl a and two nearby dimeric BChls a are 17.1 Å and 17.7 Å.

a Top view of the LH2 complex viewing from the periplasmic side. Polypeptides are shown by cylindrical cartoons and pigments are shown by sticks. Phosphatidylglycerols in the central hole are shown by thin sticks (wheat). Color scheme: α-polypeptides, cyan; β-polypeptides, magenta; BChl a, red; carotenoids, yellow. b Tilted view of the pigments in the LH2 with representative distances (in Å) between the BChls a. For clarity, phytol chains are omitted. c The BChl a-binding sites in an LH2 subunit. Half of the dimeric BChls a form hydrogen bonds with α-Tyr41 while half lack such hydrogen bonds. The monomeric BChls a are coordinated by α-Met1 and form hydrogen bonds with β-Arg38. d Overlapping view of the Hlr. halophila LH2 (colored) and that of Rbl. acidophilus 10050 (gray, PDB: 1NKZ) by superposition of Cα carbons. e Sequences of α- and β-polypeptides. Red letters: BChl a-coordinating residues; magenta letter: hydrogen-bonding residue; light-gray letters: invisible residues.

The Hlr. halophila LH2 dimeric BChls a are coordinated by α-His31 or β-His48 residues (Fig. 3e). While the dimeric BChls a coordinated by α-His31 form hydrogen bonds between their C31-carbonyl group and α-Tyr41 in the same polypeptide, such hydrogen bonds are absent from the β-His48-coordinated BChls a because the nearby residue is a Phe (α-Phe44) of a neighboring α-polypeptide (Fig. 3c). This is similar to that of the LH2 from Rhodoblastus (Rbl.) acidophilus strain 705046 but differs from that seen in the LH2 complexes from Rbl. acidophilus strain 1005022, Phaeospirillum (Phs.) molischianum23, Rhodobacter (Rba.) sphaeroides (recently reclassified into the genus Cereibacter) mutant strain B725, and Rhodopseudomonas (Rps.) palustris27. In the latter four organisms, the dimeric BChls a coordinated by β-polypeptides also form a hydrogen bond with a Tyr or Trp in the α-polypeptides (Supplementary Fig. 10d). The hydrogen-bonding pattern on the Hlr. halophila LH2 dimeric BChls a thus explains its absorption maximum at 835 nm (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Data 1). The LH2 lacking a hydrogen bond in the dimeric BChls a shows a blue-shifted Qy at 823 nm47 (as in Rbl. acidophilus 7050), whereas the LH2 complexes with their dimeric BChls a all hydrogen-bonded at the C31-carbonyl group exhibit a Qy at ~850 nm27 (as in Rbl. acidophilus 10050, Phs. molischianum, Rba. sphaeroides and Rps. palustris). Hence, the Hlr. halophila LH2 absorbs at an intermediate wavelength (835 nm) between these two absorption maxima.

The Hlr. halophila LH2 monomeric BChls a are coordinated by the N-terminal carboxymethyl methionine (Cxm1) of α-polypeptides and form hydrogen bonds between their C31-carbonyl group and β-Arg38 (Fig. 3c). The carboxymethyl group is within a hydrogen-bonding distance (~2.5 Å) of the sidechain of a nearby β-His30. The coordination by the carboxymethyl Met (hydrogen-bonded with a His) and the hydrogen-bonding with an Arg have also been observed for the monomeric BChls a in the LH2 from Rbl. acidophilus 1005022, Rba. sphaeroides B725 and Rps. palustris27. Hence, the overall structure of the Hlr. halophila LH2, including the pigment arrangement, is highly similar to those of the nonameric LH2s from Rbl. acidophilus 1005022 and a mutant strain (strain B7) of Rba. sphaeroides25 (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Fig. 10).

LH1–LH2 interactions in the co-complex

The Hlr. halophila LH1–LH2 co-complex can be viewed as a nonamer of a structural subunit containing three pairs of polypeptides: LH1-α1/β1, LH1-α2/β2, and LH2-α/β (Fig. 4a). The polypeptides within the protomer display a characteristic spatial geometry. The LH1-α2/β2 and LH2-α/β pairs lie close to each other and are aligned on the same plane in the co-complex. This arrangement is reflected in the close proximity of their genes on the Hlr. halophila chromosome (pufA2B2 and pucAB are present in the same cluster, Supplementary Fig. 1a) and their likely coordinated expression and assembly. The LH1-α1/β1 pairs (encoded by pufA1B1 in the puf operon) are located in between the arrays formed by LH1-α2/β2 and LH2-α/β polypeptides, filling the space in the larger LH1 inner and outer surfaces. In the cryo-EM structure, only one specific interaction was observed between LH1 and LH2 polypeptides, that of α2-Arg12 of LH1 and β-Asp35 of LH2. Instead, the two complexes primarily interact hydrophobically between the LH2 β-polypeptides and LH1 α-polypeptides and through the LH2 monomeric BChls a (LH2-B797) and detergent molecules (Fig. 4b, c). The intercomplex interactions between LH1-α2 and LH2-β including ion pairs are completely conserved, but most of the interactions between LH1-α1 and LH2-B797 are non-conserved among LH1 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 11). The protrusions of LH2-B797 BChls fit snugly into the hydrophobic pockets formed by these non-conserved residues. The intercomplex interface is therefore both distinct within a protomer and different from the multi-conformation double-ring complex of Gem. phototrophica. In the latter case, a ring analogous to LH2 (LHh) lies outside of the LH1 ring45 instead of inside of the LH1 ring as occurs in the Hlr. halophila co-complex. The interface characteristic was further supported in focused 3D classification48 of a protomer from the Hlr. halophila LH1–LH2 co-complex that showed a virtually identical conformation in all classes (Supplementary Fig. 12). Although speculation, it is possible that the hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions in the interface help maintain co-complex integrity at the high salinities and warm temperatures Hlr. halophila experiences in its habitat49.

a Schematic illustration of the arrangement of LH1 (closed circles), LH2 polypeptides (open circles), and LH2-B797 (ovals). Color scheme: LH1-α1, green; LH1-β1, blue; LH1-α2, orange; LH1-β2, gray; LH2-α, cyan; LH2-β, magenta; LH2-B797, wheat. The polypeptides surrounded by the dotted line encircle a protomer of the LH1–LH2 complex. b Intercomplex interaction sites (<4.0 Å). All interacting residues are shown as sticks. Most of the intercomplex interactions are hydrophobic and conserved. Non-identical residues of LH1-α are labeled with “*”. Dotted lines indicate hydrogen bonds or ion pairs. c The interface between LH1 and LH2 formed by the LH1 inner ring (α1- and α2-polypeptides) and LH2 outer ring (β-polypeptides). BChls a (LH2-B797) and detergents (DDM) are shown by wheat and cyan sticks, respectively. d Representative intercomplex BChl–BChl distances (Mg–Mg distances in Å) in the LH1–LH2 co-complex. The LH1 and LH2 BChls a are shown in red and wheat, respectively. For clarity, phytol chains are omitted.

In contrast to polypeptides, the BChls a in the Hlr. halophila LH1–LH2 co-complex reveal an extensive network of interactions between LH1 and LH2 (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 13). The LH1-B883 BChls are located just 24–27 Å (Mg–Mg) from neighboring LH2-B835 and LH2-B797 BChls, indicating exciton interactions between these pigments. Similar orientations (Qy and Qx dipole moments) of the LH1-B883 and LH2-B835 could also contribute to efficient energy transfer from the inner LH2-B835 toward the outer LH1-B883 pigments. In addition, the LH1-B797 BChls are positioned even closer (~20 Å Mg–Mg) to the nearby LH2-B797 (Fig. 4d), with a distance similar to those between LH2-B797 BChls (Fig. 3b); this implies stronger interactions between these monomeric BChls a of the two complexes. Thus, the “extra” LH1-B797 BChls may play an important role in providing a more feasible path for intercomplex exciton transfer than the more direct route from LH2-797 to LH1-B883. LH1-B797 BChls lie slightly farther from LH2-B835 BChls (~29 Å Mg–Mg, Supplementary Fig. 13), but may still interact, either directly or through LH2-B797.

Excitation energy transfer

The excitation energy transfer (EET) network comprising LH2-B797, LH2-B835, LH1-B797, and LH1-B883 was characterized by femtosecond transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy at room temperature. Figure 5 shows the transient absorption spectra in the time ranges of −0.5–10 ps (Fig. 5a) and 10–1700 ps (Fig. 5b) upon excitation at 800 nm. Sequential EET for B797→LH2-B835→LH1-B883 was accomplished within 10 ps (Fig. 5b). Decay-associated spectra (DAS) provided time constants of the EET kinetics of 0.8 ps for B797→B835 and 2.2 ps for LH2-B835→LH1-B883 (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 14). The excited state LH1-B883* relaxes to the ground state in 720 ps. Fluorescence decay analysis exhibited a single exponential manner, yielding 0.92 ns of fluorescence lifetime (Supplementary Fig. 15a) in agreement with that obtained from TA spectroscopy. Due to the spectral overlap between LH2-B797 and LH1-B797, the EET dynamics of LH2-B797→LH2-B835 and LH1-B797→LH1-B883 were indistinguishable. Therefore, a time constant of 0.8 ps could be assigned to both pathways. To further distinguish the two processes and determine their time constants, measurements on the B797 components from individual LH1 and LH2 complexes will be necessary.

Transient absorption spectra excited at 800 nm in the time range −0.5–10 ps (a) and 10–1700 ps (b). c Time dependencies of the ΔAbsorbance at the characteristic three wavelengths in the time range of −0.5–10 ps. d Diagram of EET pathways with their time constants obtained by global analysis (Supplementary Fig. 14). The duration and average power of the excitation beam were 147 fs and 10 μW, respectively. LH1–LH2 co-complexes were dissolved in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer containing 0.1 wt% DDM.

Upon excitation of LH2-B835 at 830 nm, the inter-ring EET from LH2-B835 to LH1-B883 occurs at 2.0 ps (Supplementary Figs. 16 and 17). The DAS component with the shortest lifetime of 100 fs in Supplementary Fig. 17a could represent the so-called “coherent spike” or an ultrafast relaxation process in B835. However, since the rise in the ground state bleach of B883 was also observable on a similar time scale in the DAS component, it may also represent an ultrafast energy transfer that is absent when the B797 was photoexcited. The negative band corresponding to B835 in the DAS is quite sharp and shifted toward shorter wavelengths. Hence, it may also indicate an energy transfer process from an unrelaxed excited state of B835. It is notable that the inter-ring EET rate (2.0 ps) is the same as that observed for the RC-dLH complex in Gem. phototrophica45. Distances of the nearest-neighbor BChls a of LH2-B835 and LH1-B883 are 24–26 Å, also equivalent to that of B816 and B868 (25–26 Å) in RC-dLH45. The rate constant could be universal for the inter-ring EET if inter-ring distances are the same. EET efficiency of the Hlr. halophila LH1–LH2 co-complex was evaluated from the fluorescence excitation spectrum that matches the absorptance (1–T) spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 15b). This result indicates that the EET network in Hlr. halophila functions with near 100% efficiency.

Discussion

Many structures of individual LH1 (in the form of LH1–RC)3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 and LH222,23,24,25,26,27 complexes have been reported, but to our knowledge, no fixed LH1 (or LH1–RC) and LH2 assembly (supercomplex) has been observed in ICM of purple phototrophic bacteria35. The distinct co-complex of Hlr. halophila described here features such characteristics. Attempts to obtain an LH1–LH2 co-complex by reconstitution and/or co-crystallization of LH1 (or LH1–RC) with LH2 have not succeeded. We note that a preparation of photocomplexes from Hlr. halophila strain BN9630 was reported previously50 in which the RC/LH1/LH2 fractions appeared to contain LH1–LH2 and LH1–RC complexes, but their structures were not described.

The native Hlr. halophila LH1–LH2 represents a distinct type of LH complex based on the spatial arrangement of conjoined LH1 and LH2, and points to a mechanism for optimizing light harvesting and exciton energy transfer through a pathway of LH2 (in LH1–LH2)→LH1 (in LH1–LH2)→LH1 (in LH1–RC)→RC. Typically, LH2 complexes are more abundant than LH1 complexes in mature ICMs with LH2:LH1 ratios varying between 1:1 and 7:130,32,51,52,53,54,55. This ratio varies among species and strongly depends on light conditions: low-light-grown cells tend to yield higher LH2:LH1 ratios in the ICM due to an increase in the number of LH2 complexes rather than changes in LH1 abundance32,52,53,56,57. This mechanism ultimately enhances photon absorption at low light intensity by maintaining energy transfer levels to LH1 and subsequently to the RC55,57,58. By contrast, Hlr. halophila cells express much less LH2 than LH1, roughly half that of LH1 based on comparisons of the absorption spectra of the purified LH1–LH2 co-complex and total LH1 complexes in the ICM (Supplementary Fig. 1b). A weak LH2-only-like band was observed from the detergent-solubilized ICM by sucrose density gradient separation indicating that a small amount of free LH2 may exist in Hlr. halophila ICM (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The low LH2:LH1 ratio and characteristic LH1-surrounded LH2 structure may confer an advantage over separate LH2 and LH1 complexes in terms of light harvesting and energy transfer efficiency as indicated by the EET results (Fig. 5, Supplementary Figs. 14–17), and as a result, make the phototroph more competitive in its highly saline, warm, and alkaline environment.

In addition to the LH2:LH1 ratio, the spatial arrangement of LH1 (or LH1–RC) and LH2 in the mature ICM also plays an important role in exciton transfers between the LH complexes29,32,55,57,58,59,60,61 because of the requirements for close association and connectivity between complexes for excitation energy transfers from pigment to pigment. A variety of species-dependent patterns have been observed in the organization of LH complexes but all reveal densely packed regions in the ICM ranging from the most highly organized LH complexes from Rba. sphaeroides29,54 to a more random arrangement where the LH1–RCs are intermingled with large domains of LH2 as seen in the ICM of Rba. blasticus31, Rhodospirillum (Rsp.) photometricum28,32, Phs. molischianum33, and Rps. palustris34. In the random arrangements, each LH1–RC can contact a maximum of 7 adjacent LH2 complexes59, indicating that each LH1 ring can have nearest-neighbor contacts with 7–14 LH2 αβ-subunits. Although the spatial organization of LH1–LH2 and LH1–RC in the Hlr. halophila ICM is unknown, the LH1–LH2 co-complex shows that each LH2-associated LH1 has close contacts on a constant basis and in a fixed geometry with 9 LH2 αβ-subunits (Figs. 1a and 4a). This number is similar to that in phototrophs that contain separate LH1 and LH2 systems and likely represents a strategy to allow a minimal number of LH2s to achieve a maximal efficiency of excitation transfer between LH complexes.

Despite completely different organizations, intercomplex BChl–BChl distances in the Hlr. halophila LH1–LH2 co-complex coincide with those estimated for non-conjoined LH1 and LH2 systems62,63,64,65. Sub-picosecond spectroscopic measurements on Rba. sphaeroides membranes yielded time constants of 3 ps at room temperature and 5 ps at 77 K for the excitation transfer from LH2 (B850) to LH1 (B875)62. Based on these values, distances of 27–32 Å were calculated for the BChls a between LH2 and LH1 complexes using a structural model for their association62. By contrast, high-resolution atomic force microscopy images of the LH1–RC and LH2 complexes in native membranes from Rba. sphaeroides combined with model calculations revealed somewhat shorter distances of 16–22 Å between LH2-B850 and LH1-B87565. Nevertheless, both estimated ranges are in good agreement with that determined for the Hlr. halophila LH1–LH2 co-complex (20–30 Å) on both dimeric and monomeric BChls a (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 13). This indicates that intercomplex BChl–BChl distances in the co-complex have evolved to achieve similar light harvesting and exciton transfer characteristics as those of separate LH1 and LH2 systems.

An obvious question that arises from our discovery that an LH2 complex resides within a free LH1 complex in the ICM of Hlr. halophila is how light energy transferred within the co-complex at near 100% efficiency reaches the reaction center in the phototroph’s LH1–RC core complex. Although speculation at this point, it is conceivable that an answer lies in the spatial arrangement of photocomplexes in the Hlr. halophila ICM. For example, if co-complexes lie in direct contact with core complexes within the membrane, one could envision energy absorbed by LH2 and transferred to LH1 in the co-complex being transmitted to LH1 of the core complex and from there to the reaction center. Since absorption by LH1 in the core complex of Hlr. halophila (and that of most other purple bacteria) is red-shifted relative to that of its reaction center yet efficient energy transfer from LH1 to the reaction center still occurs, might an analogous energy transfer process occur from co-complex LH1 to core complex LH1? If so, this would allow Hlr. halophila to supplement light energy absorbed directly by core complex LH1 with shorter wavelengths harvested by LH2 in the co-complex in a highly efficient manner. Further work on energy transfer in Hlr. halophila will be required to answer this intriguing question.

Methods

Preparation and characterization of the Hlr. halophila LH1–LH2 co-complex

Cells of Hlr. halophila strain BN962240,41 were cultivated phototrophically (anoxic/light) at 45 °C and pH 8.0 in media containing 3.1 M NaCl for 7 days under incandescent light (60 W). ICM was treated with 1.0% (w/v) n-dodecyl β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM) at 25 °C for 60 min followed by centrifugation at 4 °C and 150,000 × g for 90 min. The extracts were loaded onto a DEAE column (Toyopearl 650S, TOSOH) equilibrated at 8 °C with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 0.1% w/v DDM. Photocomplex fractions were eluted by a linear gradient of NaCl from 0 mM to 400 mM. However, only a very small amount of highly purified LH1–LH2 could be obtained that was used for spectroscopic measurements but was insufficient for cryo-EM analysis; most fractions contained mixtures of LH1–LH2, LH1–RC–HiPIP and LH1–RC, and one of them was used for cryo-EM analysis (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Data 1). The highly purified LH1–LH2 was concentrated for absorption and circular dichroism (CD) measurements (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. 1). The LH1–LH2 and LH1–RC mixture was assessed by negative-stain EM using a JEM-1400Flush instrument (JEOL). Carotenoids were analyzed by HPLC66. Suspension or solutions of membranes and LH were directly injected into the HPLC system (Waters), which consisted of a μBondapak C18 column and a photodiode array detector (Shimadzu). A linear gradient from methanol:water (9:1, v/v) to methanol was applied for 20 min and then methanol at flow rate of 1.8 ml/min. Each Hlr. halophila carotenoid was identified by its retention time on HPLC and absorption spectrum, and the carotenoid composition is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. Phospholipids extracted from ICM were analyzed using 31P-NMR67.

Cryo-EM data collection

Proteins for cryo-EM were concentrated to ~6 mg/ml after which 3 microliters of the protein solution were applied on glow-discharged holey carbon grids (200 mesh Quantifoil R2/2 molybdenum) that had been treated with H2 and O2 mixtures in a Solarus II plasma cleaner (Gatan, Pleasanton, USA) for 30 s and then blotted and plunged into liquid ethane at −182 °C using an EM GP2 plunger (Leica, Microsystems, Vienna, Austria). The applied parameters were a blotting time of 5.5 s at 80% humidity and 4 °C. Data were collected on a Titan Krios (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hillsboro, USA) electron microscope at 300 kV equipped with a Falcon 3 camera (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Movies were recorded using EPU software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a nominal magnification of 96 k in counting mode and a pixel size of 0.820 Å at the specimen level with a dose rate of 0.69 e− per physical pixel per second, corresponding to 1.39 e− per Å2 per second at the specimen level. The exposure time was 28.7 s, resulting in an accumulated dose of 40 e− per Å2. Each movie includes 40 fractioned frames.

Image processing

All of the stacked frames were subjected to motion correction with MotionCor268. Defocus was estimated using CTFFIND469. A total of 331,335 particles were selected from 3,194 micrographs using crYOLO70 (Supplementary Fig. 3). All of the picked particles were further analyzed with RELION3.171, and 314,478 particles were selected by 2-D classification and divided into four classes by 3-D classification resulting in only one good class of LH1–LH2 co-complex containing 126,108 particles. The initial 3-D model was generated in RELION. The 3-D auto refinement without any imposed symmetry (C1) produced a map at 2.78 Å resolution after contrast transfer function (CTF) refinement, Bayesian polishing, masking, and post-processing. These particle projections were applied C9 symmetry, and then processed by CTF refinement before repeating Bayesian polishing and 3-D auto refinement. They were also subjected to subtraction of the detergent micelle density followed by 3-D auto refinement to yield the final map with a resolution of 2.22 Å according to the gold-standard Fourier shell correlation using a criterion of 0.143 (Supplementary Fig. 3b)72. The local resolution maps were calculated with RELION. Focused 3-D classification48 was conducted for the protomer region of the LH1–LH2 ring using the mask73,74 in RELION until convergence.

Model building and refinement of the LH1–LH2 co-complex

The initial atomic model for the LH1–LH2 structures was generated with MODELLER v10.175 using the atomic models of the Tch. tepidum LH1–RC (PDB: 5Y5S) and the Rbl. acidophilus LH2 (PDB: 1NKZ). The model was then fitted to the cryo-EM map obtained for the Hlr. halophila LH1–LH2 co-complex using Chimera76. Amino acid substitutions and real space refinement for the peptides and cofactors were performed using COOT77. The manually modified model was refined in real space on PHENIX78, and the COOT/PHENIX refinement was iterated until the refinements converged. Finally, the statistics calculated using MolProbity79 were checked. Figures were drawn with the Pymol Molecular Graphic System (Ver2.5, Schrödinger)80, UCSF Chimera76, and UCSF ChimeraX81.

Femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy

The light sources for the femtosecond transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy included a regeneratively-amplified Ti:sapphire laser (Solstice, Spectra-Physics) and a pair of noncollinear optical parametric amplifiers (NOPA, TOPAS-white, Light-Conversion)82,83. Output of the Ti:sapphire laser (1 kHz, 3.0 W) was divided equally into three beams and one of them was used for direct excitation of the sample at 800 nm (pump pulse). One of the NOPA instruments was tuned to a wavelength of 830 nm for the excitation of the sample and the other (set at 1050 nm) was focused into a rotating CaF2 window (2 mm thickness) for the generation of white-light supercontinuum (wavelength range: 400–950 nm), which was utilized as the probe pulse. Polarization between the pump and probe pulses was set at the magic angle (54.7°) and the average powers were set at 10 μW and 5 μW for the pump pulses at 800 nm and 830 nm, respectively. The probe pulse was divided equally into signal and reference pulses. The signal pulse was focused into the rotating sample cell (optical path: 2 mm, absorbance of the sample at 850 nm: ~1.0). The transmitted signal pulse and the reference pulse were detected via two pairs of spectrometer and multichannel photodiode array system (MSP-1000-V, Unisoku) and the data sent to a personal computer to generate the TA spectrum (ΔAbs).

Second-harmonic-generation frequency-resolved optical gating (SD-FROG) measurements were performed to obtain the autocorrelation trace of the pump pulse84. Pulse durations of the pump pulses were optimized by a pair of Brewster prisms and they were ca. 150 fs for both excitations at 800 and 830 nm. Cross-correlation trace between the pump pulse and white-light supercontinuum was obtained by optical Kerr effect (OKE) measurements of carbon tetrachloride84. The group-velocity dispersion curve was obtained by least-squares fitting of the cross-correlation trace, and the TA signals were calibrated based on these data. Time dependence of the TA spectra at various wavelengths were simultaneously analyzed by global fitting using Glotaran software based on the R package TIMP.66,67.

Fluorescence spectroscopy

Steady-state fluorescence spectra were obtained using a spectrometer with a CCD detector as described previously85. All data were collected at room temperature. Fluorescence from LH1-B883 was detected at 904 nm. For the excitation spectrum, comparisons were made with the absorptance, 1–T, spectrum, where T is the transmittance. Absorption spectra were obtained with a Shimazu UV-1800 spectrophotometer at ambient temperature.

Time-resolved fluorescence measurements were performed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (NX-3DFLIM-N03/Nanofinder30, Tokyo Instruments, Japan) equipped with an objective lens (LUCPLFLN ×20; numerical aperture = 0.45, Olympus, Japan) and a streak camera (C10627-03, Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan). A Ti:Sapphire laser (Mai Tai VF-TIS, Spectra-Physics Inc.) was used as the excitation source at 8 MHz through a pulse picker (Model3980, Spectra-Physics Inc.). An LH1–LH2 solution (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 0.1 wt% DDM, OD883 = 0.1) was placed into a quartz cell with a path length of 2 mm. Measurements were performed under ambient conditions (~25 °C).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

References

Kimura, Y., Tani, K., Madigan, M. T. & Wang-Otomo, Z.-Y. Advances in the spectroscopic and structural characterization of core light-harvesting complexes from purple phototrophic bacteria. J. Phys. Chem. B 127, 6–17 (2023).

Wang, Z.-Y., Shimonaga, M., Suzuki, H., Kobayashi, M. & Nozawa, T. Purification and characterization of the polypeptides of core light-harvesting complexes from purple sulfur bacteria. Photosynth. Res. 78, 133–141 (2003).

Tani, K. et al. Cryo-EM structure of a Ca2+-bound photosynthetic LH1-RC complex containing multiple αβ-polypeptides. Nat. Commun. 11, 4955 (2020).

Tani, K. et al. A Ca2+-binding motif underlies the unusual properties of certain photosynthetic bacterial core light-harvesting complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 298, 101967 (2022).

Roszak, A. W. et al. Crystal structure of the RC-LH1 core complex from Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Science 302, 1969–1972 (2003).

Niwa, S. et al. Structure of the LH1-RC complex from Thermochromatium tepidum at 3.0 Å. Nature 508, 228–232 (2014).

Qian, P., Siebert, C. A., Wang, P., Canniffe, D. P. & Hunter, C. N. Cryo-EM structure of the Blastochloris viridis LH1-RC complex at 2.9 Å. Nature 556, 203–208 (2018).

Yu, L.-J., Suga, M., Wang-Otomo, Z.-Y. & Shen, J.-R. Structure of photosynthetic LH1-RC supercomplex at 1.9 Å resolution. Nature 556, 209–213 (2018).

Tani, K. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the photosynthetic LH1-RC complex from Rhodospirillum rubrum. Biochemistry 60, 2483–2491 (2021).

Tani, K. et al. A previously unrecognized membrane protein in the Rhodobacter sphaeroides LH1-RC photocomplex. Nat. Commun. 12, 6300 (2021).

Swainsbury, D. J. K. et al. Structures of Rhodopseudomonas palustris RC-LH1 complexes with open or closed quinone channels. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe2631 (2021).

Qian, P. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the Rhodospirillum rubrum RC-LH1 complex at 2.5 Å. Biochem. J. 478, 3253–3263 (2021).

Qian, P. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the dimeric Rhodobacter sphaeroides RC-LH1 core complex at 2.9 Å: the structural basis for dimerisation. Biochem. J. 478, 3923–3937 (2021).

Qian, P. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the monomeric Rhodobacter sphaeroides RC-LH1 core complex at 2.5 Å. Biochem. J. 478, 3775–3790 (2021).

Bracun, L. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the photosynthetic RC-LH1-PufX supercomplex at 2.8-Å resolution. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf8864 (2021).

Tani, K. et al. Asymmetric structure of the native Rhodobacter sphaeroides dimeric LH1-RC complex. Nat. Commun. 13, 1904 (2022).

Tani, K. et al. An LH1–RC photocomplex from an extremophilic phototroph provides insight into origins of two photosynthesis proteins. Commun. Biol. 5, 1197 (2022).

Cao, P. et al. Structural basis for the assembly and quinone transport mechanisms of the dimeric photosynthetic RC–LH1 supercomplex. Nat. Commun. 13, 1977 (2022).

Tani, K. et al. Rhodobacter capsulatus forms an unusually compact crescent-shaped LH1–RC photocomplex. Nat. Commun. 14, 846 (2023).

Bracun, L., Yamagata, A., Christianson, B. M., Shirouzu, M. & Liu, L.-N. Cryo-EM structure of a monomeric RC-LH1-PufX supercomplex with high-carotenoid content from Rhodobacter capsulatus. Structure 31, 318–328 (2023).

Tani, K. et al. High-resolution structure and biochemical properties of the LH1–RC photocomplex from the model purple sulfur bacterium, Allochromatium vinosum. Commun. Biol. 7, 176 (2024).

McDermott, G. et al. Crystal structure of an integral membrane light-harvesting complex from photosynthetic bacteria. Nature 374, 517–521 (1995).

Koepke, J., Hu, X., Muenke, C., Schulten, K. & Michel, H. The crystal structure of the light-harvesting complex II (B800-B850) from Rhodospirillum molischianum. Structure 4, 581–597 (1996).

Leiger, K. et al. Controlling photosynthetic excitons by selective pigment photooxidation. J. Phys. Chem. B 123, 29–38 (2019).

Qian, P. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides light-harvesting 2 complex at 2.1 Å. Biochemistry 60, 3302–3314 (2021).

Gardiner, A. T. et al. The 2.4 Å cryo-EM structure of a heptameric light-harvesting 2 complex reveals two carotenoid energy transfer pathways. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe-4650 (2021).

Qian, P. et al. Cryo-EM structures of light-harvesting 2 complexes from Rhodopseudomonas palustris reveal the molecular origin of absorption tuning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2210109119 (2022).

Scheuring, S. et al. Watching the photosynthetic apparatus in native membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 11293–11297 (2004).

Bahatyrova, S. et al. The native architecture of a photosynthetic membrane. Nature 430, 1058–1062 (2004).

Scheuring, S., Rigaud, J.-L. & Sturgis, J. N. Variable LH2 stoichiometry and core clustering in native membrane of Rhodospirillum photometricum. EMBO J. 23, 4127–4133 (2004).

Scheuring, S., Busselez, J. & Levy, D. Structure of the dimeric PufX-containing core complex of Rhodobacter blasticus by in situ atomic force microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 1426–1431 (2005).

Scheuring, S. & Sturgis, J. N. Chromatic adaptation of photosynthetic membranes. Science 309, 484–487 (2005).

Gonçalves, R. P., Bernadac, A., Sturgis, J. N. & Scheuring, S. Architecture of the native photosynthetic apparatus of Phaeospirillum molischianum. J. Struct. Biol. 152, 221–228 (2005).

Scheuring, S., Gonçalves, R. P., Prima, V. & Sturgis, J. N. The photosynthetic apparatus of Rhodopseudomonas palustris: structure and organization. J. Mol. Biol. 358, 83–96 (2006).

Scheuring, S. & Sturgis, J. N. Atomic force microscopy of the bacterial photosynthetic apparatus: plain pictures of an elaborate machinery. Photosynth. Res. 102, 197–211 (2009).

Liu, L.-N., Sturgis, J. N. & Scheuring, S. Native architecture of the photosynthetic membrane from Rhodobacter veldkampii. J. Struct. Biol. 173, 138–145 (2011).

Kimura, Y., Yu, L.-J., Hirano, Y., Suzuki, H. & Wang, Z.-Y. Calcium ions are required for the enhanced thermal stability of the light-harvesting-reaction center core complex from thermophilic purple sulfur bacterium Thermochromatium tepidum. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 93–99 (2009).

Kimura, Y. et al. Effects of calcium ions on the thermostability and spectroscopic properties of the LH1-RC complex from a new thermophilic purple bacterium Allochromatium tepidum. J. Phys. Chem. B 121, 5025–5032 (2017).

Seto, R. et al. Lycopene-family carotenoids confer thermostability on photocomplexes from a new thermophilic bacterium. Biochemistry 59, 2351–2358 (2020).

Imhoff, J. F., Hashwa, F. & Trüper, H. G. Isolation of extremely halophilic phototrophic bacteria from the alkaline Wadi Natrun, Egypt. Arch. Hydrobiol. 84, 381–388 (1978).

Imhoff, J. F., Kyndt, J. A. & Meyer, T. E. Genomic comparison, phylogeny and taxonomic reevaluation of the Ectothiorhodospiraceae and description of Halorhodospiraceae fam. nov. and Halochlorospira gen. nov. Microorganism 10, 295 (2022).

Challacombe, J. F. et al. Complete genome sequence of Halorhodospira halophila SL1. Stand. Genomic Sci. 8, 206–214 (2013).

Tani, K. et al. A native LH1–RC–HiPIP supercomplex from an extremophilic phototroph. Commun. Biol. 8, 42 (2025).

Xin, Y. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the RC-LH core complex from an early branching photosynthetic prokaryote. Nat. Commun. 9, 1568 (2018).

Qian, P. et al. 2.4-Å structure of the double-ring Gemmatimonas phototrophica photosystem. Sci. Adv. 8, eabk3139 (2022).

McLuskey, K., Prince, S. M., Cogdell, R. J. & Isaac, N. W. The crystallographic structure of the B800-820 LH3 light-harvesting complex from the purple bacteria Rhodopseudomonas acidophila strain 7050. Biochemistry 40, 8783–8789 (2001).

McLuskey, K., Prince, S. M., Cogdell, R. J. & Isaac, N. W. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of the B800–820 light-harvesting complex from Rhodopseudomonas acidophila strain 7050. Acta Cryst. D55, 885–887 (1999).

Bai, X. C., Rajendra, E., Yang, G., Shi, Y. & Scheer, S. H. Sampling the conformational space of the catalytic subunit of human gamma-secretase. eLife 4, e11182 (2015).

Vieille, C. & Zeikus, G. J. Hyperthermophilic enzymes: sources, uses, and molecular mechanisms for thermostability. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65, 1–43 (2001).

Leguijt, T. & Hellingwerf, K. J. Characterization of reaction center/antenna complexes from bacteriochlorophyll a containing Ectothiorhodospiraceae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1057, 353–360 (1991).

Niederman, R. A., Mallon, D. E. & Langan, J. J. Membranes of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. IV. Assembly of chromatophores in low-aeration cell suspensions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 440, 429–447 (1976).

Firsow, N. N. & Drews, G. Differentiation of the intracytoplasmic membrane of Rhodopseudomonas palustris induced by variation of oxygen partial pressure or light intensity. Arch. Microbiol. 115, 299–306 (1977).

Gardiner, A. T., Cogdell, R. J. & Takaichi, S. The effect of growth conditions on the light-harvesting apparatus in Rhodopseudomonas acidophila. Photosynth. Res. 38, 159–167 (1993).

Adams, P. G. & Hunter, C. N. Adaptation of intracytoplasmic membranes to altered light intensity in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1817, 1616–1627 (2012).

Lüer, L. et al. Tracking energy transfer between light harvesting complex 2 and 1 in photosynthetic membranes grown under high and low illumination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 1473–1478 (2012).

Aagaard, J. & Sistrom, W. R. Control of synthesis of reaction center bacteriochlorophyll in photosynthetic bacteria. Photochem. Photobiol. 15, 209–225 (1972).

Driscoll, B. et al. Energy transfer properties of Rhodobacter sphaeroides chromatophores during adaptation to low light intensity. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 17133–17141 (2014).

Timpmann, K. et al. Efficiency of light harvesting in a photosynthetic bacterium adapted to different levels of light. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1837, 1835–1846 (2014).

Sturgis, J. N. & Niederman, R. A. Atomic force microscopy reveals multiple patterns of antenna organization in purple bacteria: implications for energy transduction mechanisms and membrane modeling. Photosynth. Res. 95, 269–278 (2008).

Dahlberg, P. D. et al. Mapping the ultrafast flow of harvested solar energy in living photosynthetic cells. Nat. Commun. 8, 988 (2017).

Onizhuk, M., Sohoni, S., Galli, G. & Engel, G. S. Spatial patterns of light-harvesting antenna complex arrangements tune the transfer-to-trap efficiency of excitons in purple bacteria. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 6967–6973 (2021).

Hess, S. et al. Temporally and spectrally resolved subpicosecond energy transfer within the peripheral antenna complex (LH2) and from LH2 to the core antenna complex in photosynthetic purple bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 12333–12337 (1995).

Pullerits, T. & Sundström, V. Photosynthetic light-harvesting pigment-protein complexes: toward understanding how and why. Acc. Chem. Res. 29, 381–389 (1996).

Fleming, G. R. & van Grondelle, R. Femtosecond spectroscopy of photosynthetic light-harvesting systems. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7, 738–748 (1997).

Scheuring, S., Boudier, T. & Sturgis, J. N. From high-resolution AFM topographs to atomic models of supramolecular assemblies. J. Struct. Biol. 159, 268–276 (2007).

Takaichi, S. et al. Direct injection of pigment–protein complexes and membrane fragments suspended in water from phototrophs to C18 HPLC. Photosynth. Res. 144, 101–107 (2020).

Nagatsuma, S. et al. Phospholipid distributions in purple phototrophic bacteria and LH1-RC core complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1860, 461–468 (2019).

Zheng, S. Q. et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017).

Rohou, A. & Grigorieff, N. Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol. 192, 216–221 (2015).

Wagner, T. & Raunser, S. The evolution of SPHIRE-crYOLO particle picking and its application in automated cryo-EM processing workflows. Commun. Biol. 3, 61 (2020).

Zivanov, J. et al. New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. eLife 7, e42166 (2018).

Rosenthal, P. B. & Henderson, R. Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 333, 721–745 (2003).

Roh, S. H. et al. Subunit conformational variation within individual GroEL oligomers resolved by Cryo-EM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 8259–8264 (2017).

Yamaguchi, H. et al. Structural insights into thermostabilization of leucine dehydrogenase from its atomic structure by cryo-electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 205, 11–21 (2019).

Šali, A. & Blumdell, T. L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779–815 (1993).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501 (2010).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Cryst. D66, 213–221 (2010).

Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 (2010).

DeLano, W. L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific, LCC (2004).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: structure visualization for researchers, editors, and developers. Protein Sci. 30, 70–82 (2021).

Kihara, Y., Tani, S., Higashi, Y., Teramoto, T. & Nagasawa, Y. Ultrafast excited state dynamics of forward and reverse trans-cis photoisomerization of red-light-absorbing Indigo derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. B 126, 3539–3550 (2022).

Hidaka, T., Tanaka, T., Murai, T., Teramoto, T. & Nagasawa, Y. Spectral heterogeneity of phenol blue in protic solvents revealed by ultrafast nonradiative decay dynamics. ChemPhotoChem 8, e202300163 (2024).

Trebino, R. et al. Measuring ultrashort laser pulses in the time-frequency domain using frequency-resolved optical gating. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 68, 3277–3295 (1997).

Sumino, A. et al. Influence of phospholipid composition on self-assembly and energy-transfer efficiency in networks of light-harvesting 2 complexes. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 10395–10404 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Mahiro Yamashita for providing technical assistance. This research was partially supported by Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS)) from AMED under Grant Numbers JP20am0101118 (support number 1758) and JP20am0101116 (support number 1878), 17am0101116j0001, 18am0101116j0002, and 19am0101116j0003. R.K., E.R.P., M.H. and B.M.H. acknowledge the generous support of the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST), Scientific Computing & Data Analysis Section at OIST and the Japanese Cabinet Office. This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 20H05086, 20H02856, 23K05822, 24K01620, 22K06144, 24H02084, 22K18694, 21H01985, 22H05416, 24H01128, and 22K19060, Japan. K.T. was supported in part by the Center for Quantum and Information Life Sciences, University of Tsukuba. L.-J.Y. acknowledges support of the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2019YFA0904600). M.T.M. was supported in part by NASA Cooperative Agreement 80NSSC21M0355. R.Ka. acknowledges support from Prof. Tsumoru Shintake.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.-Y.W.-O., Y.K., Y.N., T.D. and K.T. designed the work. M.T.M. provided materials. K.T., K.V.P.N., R.Ko., M.K., R.Ka., I.S., M.K., N.H., K.N., S.N., K.I., Y.I., R.M., S.T., E.R.P. M.H. and B.M.H. performed the experiments. K.T., K.V.P.N., R. K., L.-J.Y., Y.K., M.T.M., A.M., B.M.H. and Z.-Y.W.-O. analyzed data. Z.-Y.W.-O., K.T., Y.K., Y.N., T.D. and M.T.M. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Gagik Gurzadyan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tani, K., Nagashima, K.V.P., Kojima, R. et al. A distinct double-ring LH1–LH2 photocomplex from an extremophilic phototroph. Nat Commun 16, 1410 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55811-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55811-9