Abstract

Transport of energy carriers in solid-state materials is determined by their wavefunctions and interactions with the environment. While quantum transport theory has predicted distinct transport in the intermediate coupling regime resulting from the intricate interplay between coherent wave-like and incoherent particle-like mechanisms, these predictions are awaiting experimental evidence. Here we demonstrate quantum transport signatures in perovskite nanocrystal superlattices by imaging exciton propagation with high spatial and temporal resolutions over 7-298 K. At 7 K, coherent propagation of the excitons dominates, with transient ballistic motion within a coherence length of up to 40 nanocrystal sites. The interference of the wave-like motion leads to Anderson Localization in the long-time limit. As temperature increases, a peak in the long-time diffusion constant is observed at a temperature where static disorder and dephasing are balanced, which substantiates evidence for environment-assisted quantum transport. Our results connect theoretical predictions and experiments using a stochastic Anderson localization model, highlighting perovskite nanocrystals as promising building blocks for quantum materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The transport of excitation energy through networks of interacting particles is a fundamental process that underlies various crucial phenomena, ranging from the efficient capture of light energy in photosynthesis to the transmission of information between qubits1,2,3,4,5,6. While electronic transport has been studied in both the coherent and incoherent limits, there are limited experimental studies addressing the intermediate regime where both coherent and incoherent effects are important. Recent theoretical calculations have shed light on the interplay between coherence, dephasing, and disorder in the intermediate coupling regime, revealing quantum transport behaviors that interpolate between the ballistic and diffusive limits4,7,8,9,10. Intriguingly, theoretical investigations and quantum simulations have predicted a phenomenon known as environment-assisted quantum transport (ENAQT), which challenges conventional wisdom3,7,11,12,13. It postulates that the presence of dephasing, including thermal fluctuations and interactions with phonons, can unexpectedly enhance the transport of quantum states within disordered systems. However, the experimental validation of these predictions remains elusive. The main challenge lies in probing transport in the quantum regime in complex materials, which involves fast dephasing processes on the picosecond or shorter timescale and nanoscale localization lengths.

Superlattices (SLs) composed of interacting lead halide perovskite colloidal nanocrystals (NCs)14,15, such as those derived from cesium lead bromide (CsPbBr3), offer a highly-controllable platform for investigating quantum transport phenomena in the intermediate coupling regime. Critically, their large oscillator strengths allow for an exciton coupling strength that can overcome static disorder in the system16,17,18,19. In addition, the optical coherence time of excitons in individual CsPbBr3 NCs has been reported to be as long as 80 ps at 4 K20,21,22. With well-controlled size and inter-NC distance, electronic coupling can be tuned in these SLs to modify the competition between coherence and dephasing. Recent studies have revealed that excitons can be delocalized across multiple NCs in these SLs14,23. Exciton transport in colloidal NC solids have been extensively studied, including perovskite and metal chalcogenide NCs. However, despite the importance of quantum effects, the majority of these studies conventionally assumed classical diffusion24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. While preliminary evidence hinting at enhanced transport due to coherent effects has been previously proposed, such as the fast early-time transport in the study by Zhang et al.32, they have not fully addressed the temperature-dependent behavior crucial for a comprehensive mechanistic understanding. Importantly, the temperature dependence of exciton transport serves as a key factor in unraveling the intricate interplay between coherence and dephasing, thereby enabling a rigorous test of ENAQT predictions.

Here, we present direct visualization of coherent transport of excitons and an experimental realization of ENAQT in perovskite NCSLs. Leveraging transient absorption and photoluminescence (PL) microscopy techniques24,33, we achieved high spatial and temporal resolution simultaneously, enabling a comprehensive investigation of different exciton transport regimes over a temperature range spanning 7-298 K. To simulate the experiments, we employed the Anderson Hamiltonian and the Haken-Strobl-Reineker (HSR) model7. At 7 K, ballistic transport over 10 s of NC sites leads to a maximum transient diffusion constant. Most remarkably, at intermediate temperatures, the interplay between coherence and dephasing collaboratively enhances transport. We observed a maximum for the steady-state diffusion constant at temperatures where static disorder and thermal fluctuations balance each other, providing experimental evidence of ENAQT.

Results

NCSLs as a platform to investigate quantum transport

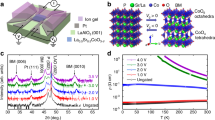

One defining characteristic of disordered materials, such as colloidal NC solids, is the impact of the static and dynamic disorder on their optical and transport properties. Fig. 1a provides a visual representation of the essential parameters influencing exciton transport in CsPbBr3 NC SLs. The static disorder \(\Delta\) arises from inhomogeneities in NC size and orientation and \(\varGamma\) characterizes dephasing resulting from dynamic disorder, such as phonon scattering and thermal fluctuations. The electronic coupling strength between neighboring NCs is denoted as J, which results from the coupling between their transition dipoles through Coulombic interactions. J is given by \(J=\frac{\kappa {\mu }^{2}}{{n}^{2}{\varepsilon }_{0}{a}^{3}}\), where\(\,\mu\) transition dipole moment, n is the refractive index, \({\varepsilon }_{0}\) is vacuum permittivity, \(a\) is the distance between NCs, and \(\kappa\) is the orientation factor (2 based on the head-to-tail alignment of dipoles). The different quantum transport regimes are illustrated in Fig. 1b. At low temperatures (minimal dephasing), wave-like ballistic transport is expected within the coherence length \({L}_{0}\) and destructive interference prevents the transport between the coherent segments as predicted by Anderson localization1. At high temperatures, large thermal fluctuations induce dynamic exciton localization to a single NC, leading to random walks that resemble classical diffusion. Notably, in the intermediate temperature regime known as ENAQT, weak dephasing is predicted to mitigate the destructive phase interference linked to Anderson localization, thereby facilitating enhanced quantum transport.

a A schematic illustrating the different parameters influencing exciton transport in NCSLs, including static disorder \(\Delta\), dephasing \(\varGamma\), and dipolar coupling J. b Schematic illustration of different transport regimes interpolated between the wave-like coherent and particle-like incoherent limit. At low temperatures, in the absence of dephasing, the propagation is wave-like within the coherence length defined by Anderson localization. Quantum interference leads to total suppression of transport at the long-time limit. At intermediate temperatures, dephasing can destroy the phase coherence responsible for Anderson localization and induce transport, this is the essence of ENAQT. At high temperatures, coherence is rapidly lost and excitons transition to classic diffusion-like movement. c Chemical structures of the OA/OAm and DAB ligands along with the CsPbBr3 core. d–e TEM images of NCs showing difference in gap spacing for OA/OAm (d) and DAB (e). f–g with 1D trace insets, small-angle X-ray scattering of SLs of OA/OAm capped NCs (e) and SLs of DAB capped NCs (f). h 7 K PL spectra of DAB-1, OA-1 SLs are compared to uncoupled (UC) NCs. i–j Transient PL dynamics of DAB-1 (i) and OA-1 (j) at various temperatures. PL lifetimes decrease as temperature decreases, which can be attributed to superradiant decay from delocalized excitons. The measured instrument response function (IRF) of the system is shown in gray in (i) and (j).

We prepared CsPbBr3 NCs capped by oleic acid/oleylamine (OA/OAm) ligands and didecyldimethylammonium bromide (DAB) ligands (structures shown in Fig. 1c) to access different disorder and coupling strengths upon assembly of the NCSLs. Details on the NCSL synthesis, structural characterization, and optical images can be found in the Methods and Supplementary Figs. 1–3. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images displayed in Fig. 1c, d provide a comparison of the inter-NC distances for SLs prepared using different ligands. Additional TEM images are available in Supplementary Fig. 1. While the NC core size is similar, 8-9 nm (Supplementary Fig. 1a–d), the use of longer OA/OAm ligands results in a larger average center-to-center distance a of 11.2 nm ± 1.1 nm (Fig. 1d). Conversely, the use of DAB ligands yields a reduced a of 9.9 nm ± 1.1 nm (Fig. 1e). The difference in interparticle-distance is also reflected in the small-angle X-ray scattering patterns (Fig. 1f, g). More orientational disorder is present in DAB NCSL when compared to OA/OAm NCSL as demonstrated through scanning TEM imaging and fast Fourier transform analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1e–i). The Bohr diameter of excitons in CsPbBr3 NCs is estimated to be 7 nm34, indicating that the excitons are in the intermediate confinement regime17. For CsPbBr3 NCs of 8-9 nm in size, it is known that the lowest exciton state is a bright triplet state35,36, which leads to a large oscillator strength and strong dipolar coupling.

The emission for SLs at 7 K (Fig. 1h, OA-1 and DAB-1) is red-shifted and narrower compared to the uncoupled NCs (UC NCs), an optical signature of delocalized excitons23, similar to what is observed in molecular J-aggregates37. PL lifetimes also decrease as temperature decreases in all SLs (Figs. 1i, j and Supplementary Fig. 4), which suggests an additional indication of superradiant decay from delocalized excitons, consistent with our previous work23. The delocalized state arises from the quantum superposition of N NC excitations, resulting in a state that is superradiant. This is due to the transition dipole moment of delocalized excitons being enhanced by a factor of N (similar to superradiance in molecular J-aggregate37,38), a phenomenon termed single-photon superradiance39. This differs fundamentally from many-body superfluorescence14, where the transition dipoles of multiple NCs align into a macroscopic dipole following photoexcitation. It is important to note that the formation of SLs tends to favor a subset of NC sizes40, meaning the energy shifts observed between the UC NCs and SLs cannot be directly equated to \({J}\) coupling and instead we estimated \({J}\) using dipolar coupling. The shorter inter-NC distance in the SLs prepared with DAB ligands contributes to a stronger \(J\) at approximately 40 meV. In contrast, the SLs prepared with OA/OAm ligands exhibit a lower value of \(J\), approximated at 20 meV. Additional details on dipolar coupling can be found in the "Methods". The occurrence of multiple PL peaks suggests the presence of multiple aggregate domains composed of different NC sizes, as detailed in Supplementary Fig. 2. In our experiments, we focus on the SLs that display majorly a single redshifted emission peak (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicative of a more uniform NC size distribution and minimal presence of UC NCs.

The strength of static and dynamic disorder in SLs are reflected in the temperature-dependent PL spectroscopy. We examined the emission linewidths and their temperature dependence of three different SLs, denoted as DAB-1, DAB-2, and OA-1 (Supplementary Figs. 5–7). As the temperature increases, the exciton linewidth increases further, largely due to scattering from optical phonons of energy around 16 meV23. The linewidths at 7 K (Supplementary Fig. 7), where static disorder dominates and dynamic disorder is minimal, are 26.0 meV, 34.7 meV, and 16.0 meV for DAB-1, DAB-2, and OA-1, respectively. The broader linewidth observed in the SLs with DAB ligands is attributed to larger inhomogeneities in NC sizes and variations in inter-NC distances, as reflected in the broader peak of the small angle X-ray scattering patterns (Fig. 1f, g). Overall, \(J\), \(\varGamma,\) and \(\Delta\) can be of similar energy scales, on the order of 10 s of meV, which provides an ideal platform to investigate quantum transport.

Time- and temperature- dependent exciton transport

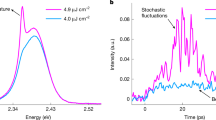

We utilized complementary time-resolved PL and femtosecond transient absorption microscopy (TAM) between 7-298 K (see “Methods” for details) to investigate different quantum transport regimes as illustrated in Fig. 1b. The PL microscopy approach involves mapping the spatial and temporal evolution of the emission intensity using a time-correlated single photon counting detector, and the results are shown in Fig. 2a, b for DAB-1 (also Supplementary Figs. 8a–d for DAB-2 and OA-1 SLs). For TAM, we used a fixed pump beam and scanned the probe beam across the sample, resulting in images that depict the pump-induced change in the probe reflection as a function of probe position (Supplementary Fig. 9)41, providing a time resolution of ~ 200 fs. Although the temporal resolution of PL microscopy is inferior, (about 70 ps), it provides a superior sensitivity that is critical for imaging transport over a nanosecond window which is necessary for investigating ENAQT. The results presented are the average calculated from multiple separate measurements (Supplementary Figs. 10a, b). The exciton density for these measurements was 1.0\(\times\)1011 cm-2 and high-order effects, such as annihilation, are negligible (see “Methods” and Supplementary Figs. 10c, d).

a Time- and spatial- dependent PL microscopy images of DAB-1 at select temperatures (7, 89, and 295 K). The PL intensity is normalized to the center to visualize the spreading of excitons. b The exciton spatial profiles extracted from a at different delay times. Notably, the distribution deviate from Gaussian due to non-diffusive coherent motion. c-d Mean squared displacement (MSD) \({R}^{2}\left(t\right)\) as a function of time calculated as described in the main text from transient PL microscopy profiles of DAB-1 (c), and OA-1 (d). The error bars represent standard deviation calculated from five separate measurements. At low temperatures, the short-time non-diffusive exciton transport highlighted by the shaded areas exhibits enhancement as the temperature decreases. The long-time transport displays a non-monotonic temperature dependence, with a maximum observed at an intermediate temperature, which is a signature of ENAQT.

It is noteworthy that the time-dependent exciton spatial profiles depicted in Fig. 2b markedly diverge from a Gaussian shape, despite being subjected to a Gaussian excitation beam (fitting to Gaussian and the excitation beam shown in Supplementary Fig. 8g). This deviation arises because a Gaussian distribution is a result of diffusive motion from numerous random walks. In contrast, coherent motions and quantum transport yield distribution tails that decay more slowly than a Gaussian function42. Consequently, fitting the spatial distribution to Gaussian functions is not appropriate in this context. Instead, we calculated the mean squared displacement (MSD) of the excitons directly, as given by \({R}^{2}(t)={\sum }_{n}{P}_{n}(t)|{r}_{n}-{r}_{0}{|}^{2}\), where n denotes the site index in the SLs, \({P}_{n}\left(t\right)\) is the probability of finding an exciton at site n, and rn is the spatial location of site n. The \({R}^{2}\left(t\right)\) as a function of temperature, averaged from multiple time-resolved PL microscopy measurements, for DAB-1 and OA-1 are shown in Figs. 2c, d, respectively. The results from DAB-2 are plotted in Supplementary Fig. 8e.

This non-monotonic temperature dependence of MSD underscores the interplay between coherence, disorder, thermal fluctuations, and different transport regimes as depicted in Fig. 1b. Notably, two important observations emerge. Firstly, at low temperatures, the transient non-diffusive exciton transport (as highlighted by the shaded areas in Fig. 2c, d) exhibits enhancement as the temperature decreases. Because excitons are more delocalized at lower temperature due to slower dephasing from phonon scattering23, this behavior suggests enhanced exciton migration by coherent effects in this temperature regime and consistent with non-gaussian spatial distribution. This short-time regime persisted the longest for DAB-1. We note that for DAB-1 and DAB-2, the initial exciton migration at 7 K is slightly slower than 11 K accompanied by a small decrease in PL intensity, possibly due to trap states being populated. Secondly, for all three SLs, the long-time transport ( > 1 ns) displays a non-monotonous temperature dependence, with a maximum observed at an intermediate temperature, suggesting the existence of ENAQT. At 295 K (\(\varGamma \, \gg \, J\)), any coherence created during the time evolution is quickly destroyed, excitons migrate entirely incoherently, which resembles classical diffusion. The exciton diffusion measured at room temperature, 0.1–0.5 cm2s-1 are consistent with other measurements on perovskite NC solids27,30,43.

We also performed experiments on two control samples, a thin film with randomly distributed NCs in a PMMA matrix as well as a bulk crystal of CsPbBr3 (Supplementary Figs. 11–13). Both these two control cases show very different temperature-dependent transport behaviors from the nanocrystal superlattices. Specifically, the diffusion constant monotonously increases as temperature increases in the random thin film, which implies that thermal activation is necessary for incoherent hopping between the NCs. Interestingly, NCSLs also exhibit different temperature and time-dependent transport from the bulk crystal (Supplementary Fig. 12, 13). Firstly, transport in the SLs is substantially faster than in the bulk crystal in the sub-nanosecond timescale at 7 K and a transient coherent regime was not observed in the bulk crystal, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 13. These observations suggest different electronic coupling and dephasing mechanisms in NCSLs compared to the bulk crystal. Although faster transport in the NCSLs might seem counterintuitive, it can be understood by considering the exciton coupling between the NCs. In the SLs with NCs separated by long-chain insulating ligands, exciton transport exclusively relies on long-range dipolar exciton interactions, whereas in the bulk crystal with extended lattices, the exciton binding energy is smaller and band-like charge transport is more important. The dipolar coupling between the quantum confined NCs is stronger than in the bulk due to larger exciton transition dipole moment resulting from a better overlap between the electron and hole envelope functions35. Secondly, for the bulk crystal, transport decreases monotonically with increasing temperature, exhibiting relatively weak temperature dependence below 100 K. The weak temperature dependence in the bulk crystal can be explained by the fact that before the activation of phonon scattering, transport is controlled by temperature-independent defect scattering within the band. The defect scattering leads to fast dephasing and hence the absence of the coherent transport on the time scale of 100 ps in the bulk crystal. In contrast, excitons are charge neutral particles so that the scattering from charge impurities and other defects are much less significant in the SLs than in the bulk. This results in slower dephasing and coherent transport on the time scale of 100 s of ps of the excitons in SLs.

At high temperatures, there is a finite probability of excitons dissociating into free charge carriers. However, the nanocrystals are separated by long insulating ligands, such as OA and DAB, which greatly hinder charge transport. A recent work demonstrated that room-temperature free carrier mobility is ~0.19 cm²V−1·s−1, equivalent to a diffusion constant of about 0.0048 cm²s−144. Based on this, we conclude that the contribution of free charge carrier transport to our results is negligible. Photon recycling through reabsorption45 may contribute to the background incoherent exciton transport. However, this effect is unlikely to cause the observed non-monotonous temperature dependence, given that the Stokes shift of ~ 50 meV remains constant across temperatures for the SLs23. This Stokes shift is in line with observations from diluted solutions and the intrinsic Stokes shift reported previously46, suggesting minimal reabsorption within the SLs. The limited reabsorption can be attributed to their narrow size distribution.

Ballistic transport within the coherence length of the excitons

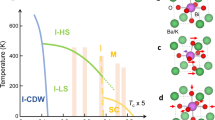

We first focus on the initial fast exciton transport that is enhanced at low temperatures. The effective time-dependent diffusion constant can be calculated by, \(D\left(t\right)=\frac{d{R}^{2}(t)}{2{dt}}\), which is plotted as a function of time at different temperatures for DAB-1 and OA-1 in Figs. 3a, b, respectively (results from DAB-2 in Supplementary Fig. 8f). We compare the results at 7 K in Fig. 3c, where both \(t\) and \(D(t)\) are plotted in dimensionless units, \(t\to {Jt}\), \(D\to D/J{a}^{2}\), using J from the dipolar estimates (see “Methods”) and X-ray and TEM analysis. We consider the exciton coupling strength \(J\) to be independent of temperature, drawing on findings from our previous report on exciton absorption of isolated NCs does not change significantly as a function of temperature23. We simulated \(D\left(t\right)\) as a function of dephasing rate \(\varGamma\), using an HSR model (Fig. 3d, more details described in "Methods"). From here, we correlate larger \(\varGamma\) simulation to experimental exciton transport at a higher temperature and use the terms dephasing rate and temperature interchangeably. In the weak dissipative regime (low-temperature, \(\varGamma \, \ll \, J\)), \(D\left(t\right)\) is predicted to increase initially with t and has a maximum value \({D}_{\max }\) at \({t}_{\max }\) due to the coherent transport within the exciton coherence length \({L}_{0}\), as defined by Anderson localization (Fig. 3d). \({D}_{\max }\), \({t}_{\max }\) and \({L}_{0}\) are inversely proportional to \(\Delta /J\) as simulated in Fig. 3e and illustrated in in Fig. 3f. Rising temperatures accelerate dephasing from phonon scattering, leading to a reduced ballistic transport and a decrease in \({D}_{\max }\,\). Upon increase in time, \(D\left(t\right)\) decays and the relaxation time is sensitive to \(\varGamma\) (Fig. 3d). This predicted temperature- and time- dependence agrees with the experimental observation in Fig. 3a, b. We note that the HSR model treats the exciton-phonon interaction classically and does not properly account for detailed balance at finite temperatures. Consequently, the correspondence between experimental dephasing dynamics and simulations is on a qualitative basis.

a–b Temperature dependence of diffusivity as the first derivative, \(D(t)=\frac{d{R}^{2}(t)}{2dt}\), for DAB-1 (a), and OA-1 (b). The orange and purple shaded areas represent the time windows used to extract \({D}_{\max }\) and \({D}_{s}\), respectively. The standard deviations are calculated from multiple separate measurements at each temperature. c Comparison of diffusivity between DAB-1, DAB-2 and OA-1 at 7 K using transient PL microscopy, plotted as unitless \(D(t)/J{a}^{2}\). These results provide evidence for coherent exciton transport within \({L}_{0}\) by validating the existence of a distinct peak \({D}_{\max }\). The color circles indicate \({D}_{\max }\). The error bars represent standard deviation calculated from multiple separate measurements. d Simulated diffusivity with increasing \(\varGamma\) (blue to red) with \(\Delta /J=1.0\), plotted as unitless \(D/J{a}^{2}\). Here a larger \(\varGamma\) is correlated to a higher temperature and the terms dephasing rate and temperature are used interchangeably within the HSR model. e Simulated diffusivity for selected \(\Delta /J\) values with \(\varGamma=0\) and initialized as a Gaussian distribution with standard deviation of 10 lattice spacings, plotted as unitless \(D/J{a}^{2}\). f Illustration of the relationship between \(\Delta /J\) and \({L}_{0}\). During \({t}_{\max },\) excitons propagate ballistically within the coherent length \({L}_{0}\).

The correspondence between experimental and theoretical results provides evidence for coherent exciton transport based on the existence of a distinct peak diffusivity \({D}_{\max }\) (experiments in Fig. 3c, HSR modeling in Fig. 3e). \({t}_{\max }\) is ~ 400 ps and ~ 200 ps for DAB-1 and DAB-2, respectively, which can be explained by a larger \(\Delta /{{\rm{J}}}\) in DAB-2 as evident by broader PL linewidth (Supplementary Fig. 7). For OA/OAm ligands, \({t}_{\max }\) is much shorter at ~ 10 ps and can only be observed in the TAM measurements with higher temporal resolution (Supplementary Fig. 9 for OA-2 SL). This difference can be rationalized by a smaller \({{\rm{J}}}\) due to larger inter-NC distance in SLs with OA/OAm ligands, giving rise to a shorter \({L}_{0}\). Thus, qualitatively, the dependence of and \({D}_{\max }\) and \({t}_{\max }\) on \(\Delta /J\) agrees well with the prediction from the HSR model. We can estimate an upper bound of \({L}_{0}\) to be the square root of the area under \(D\left(t\right)\) before its peak value: \({L}_{0}\le \sqrt{{\int }_{0}^{{t}_{\max }}D\left(t\right){dt}}\), in units of the number of NC sites, as the MSD gained during this time duration can mostly be attributed to ballistic wavepacket expansion within \({L}_{0}\). Using experimental data, the upper limit for \({L}_{0}\) is determined to be 40, 17, and 5 for DAB-1, DAB-2, and OA-1, respectively. For OA-1, \({L}_{0}\) is on the same order as an average coherence number of 3 determined in our previous work on SLs with OA/OAm ligands calculated by superradiance decay rate23.

At the long-time limit, \(D\left(t\right)\) approaches 0 at 7 K, which can be explained by the lack of transport as predicted by Anderson due to quantum interference in a disordered energy landscape1,47. In DAB-1, \(D\left(t\right)\) dips below 0 during 1.5 – 3.5 ns at 7 K as depicted in Fig. 3a (also seen in DAB-3 in Supplementary Fig. 10d). This can be rationalized by the coherent back reflection of wave propagation at the edge of \({L}_{0}\), resulting in a reduction of the MSD. This effect is most pronounced in DAB-1 with the largest coherent length that is comparable to the beam sized of ~ 300 nm. Because \({L}_{0}\) is much shorter in DAB-1 and OA-1, the measurements were averaged over many coherent domains, which diminishes the ability observe the coherent back reflection. It is worth noting that the contraction in MSD aligns with findings from quantum transport simulations using superconducting qubits48 and reduction of diffusion due to quantum inference was also investigated theoretically in a 2D semiconductor49,50. In NCSLs, the lattice packing is less perfect than in crystalline bulk semiconductors, making quasimomentum not a good quantum number. Consequently, at low temperatures, exciton transport in NCSLs is predominantly impeded by Anderson localization, rather than scattering within a band (see Supplementary Note 2). For defect scattering in a band, such as for the bulk crystal at 7 K (Supplementary Fig. 13), transport is always allowed but the mean free path of the carriers is reduced by the presence of defects.

ENAQT

In the following, we analyze the temperature-dependent behavior to evaluate whether the synergistic interplay between static and dynamic disorder indeed results in the enhanced transport phenomena as theorized by ENAQT. As a result of the competition between Anderson localization and dephasing, the diffusion constant at the long-time steady-state limit is given by \({D}_{s}=\frac{2{J}^{2}\varGamma }{{\varGamma }^{2}+{\Delta }^{2}}\cdot {\left[L\left(\Gamma,\Delta \right)\right]}^{2}\), where \(L\left(\varGamma,\Delta \right)\) denotes the coherence length in a system influenced by dephasing \(\varGamma\)7. Dephasing at elevated temperature can mitigate phase interference of Anderson localization, facilitating transport. However, dephasing also introduces dynamic localization, reducing the coherence length compared to its initial value \({L}_{0}\). This leads to an optimal dephasing rate that maximizes long-time diffusion, which is the essence of ENAQT. We visualize this optimal diffusion in Fig. 4, where the \({D}_{s}\) peaks at an intermediate temperature, marking the ‘turnover temperature’ Tt - akin to Kramer’s turnover in classical systems51. This temperature signifies when static disorder and dephasing is balanced, \(\varGamma=\,\Delta\). Our experimental data, depicted in Fig. 4c–e, corroborate this turnover temperature in all three SLs. For OA-1, Tt is ~ 70 K while for DAB-1 and DAB-2 the Tt is ~ 100 K. Quantum diffusion in the ENAQT regime is considerably larger than classical diffusion, as \(L\left(\varGamma,\Delta \right)\) defines a larger step-size than a classical random walk (Fig. 4a).

a Schematic illustration of ENAQT. At finite dephasing, \(L\left(\varGamma,\Delta \right)\) defines a larger step-size than a classical random walk, and weak dephasing can destroy the phase coherence responsible for Anderson localization and induce transport between coherent segments. b A maximum (purple filled circle) of long-time diffsuion Ds is predicted at a turnover temperature Tt when \(\varGamma \approx \Delta\), which is the essence of ENAQT, diffusivity is plotted as unitless \(D/J{a}^{2}\). c–e Experimentally measured Ds and \({D}_{\max }\) for DAB-1 (c), DAB-2 (d), and OA-1 (e). The error bars represent standard deviation calculated from multiple separate measurements.

The turnover temperature can also be observed by when the transient diffusion constant \({D}_{\max }\) converges with the steady-state diffusion constant \({D}_{s}\) (Fig. 4b). In the long-time limit at low temperature, the dominant scattering channel is through the destructive interference induced by static disorder. In contrast, in the short-time regime, the excitons take time to reach the coherence length and scattering is primarily induced by dynamic disorder. At the turnover temperature, the scattering rate at the short-time and long-time limit converges \((\varGamma \sim \,\Delta )\), and \(D\left(t\right)\) becomes time independent. Experimentally, we obtained \({D}_{s}\) and \({D}_{\max }\) (Fig. 4c–e) by extracting \(D\left(t\right)\) near \({t}_{\max }\) and at the long-time limit as denoted by the red and blue shaded areas in Fig. 3a–c. The convergence of Ds and \({D}_{\max }\) was observed experimentally (Fig. 4c–e), at a temperature similar to Tt, lending further support for ENAQT. Note that there is a minor increase of \({D}_{\max }\) when temperature increases from 7 K to 11 K in DAB-1 and DAB-2. This trend can likely be attributed to trap states, which might trap excitons at 7 K, and these states have not been incorporated in our current model.

In the current HSR model, the noise is treated classically. We have also previously predicted the turnover temperature with full quantum treatments using polaron-transformed quantum master equations52 or stochastic path integral simulations8. We also note that transient localization and delocalization theoretical framework in molecular systems is relevant to the present work53,54,55,56,57. In the case of transient localization, raising the temperature primarily causes larger random intermolecular displacements whose relaxation time is longer than the transport timescale, predicting a monotonically decreasing transport with increasing temperature. For transient delocalization, vibrations supply activation energies to transiently promote excitons to higher energy states that are more delocalized, thereby enhancing their mobility53,54,55,56. This is akin to the high-temperature regime in ENAQT, where thermal activation is the primary transport mechanism. A distinction is that, in organic molecular systems that form small polarons, the reorganization energy (hundreds of meV) is typically an order of magnitude larger than the excitonic coupling strength (tens of meV)55. For CsPbBr₃ nanocrystals, the coupling to phonons is weaker compared to the vibrational coupling in organic semiconductors, and the reorganization energy is similar to the exciton coupling (tens of meV). However, the transient delocalization/localization mechanism is built on phonon coupling without accounting for static disorder. Our experimental measurements report two key observations supporting the rich physics resulting from the competition between static disorder and dynamic noise: (i) a turnover in long-time diffusivity and (ii) non-monotonic transient diffusivity. In this context, our joint experimental-theoretical effort expands the scope of the transient delocalization/localization mechanism. Nonetheless, the interplay between transient localization and delocalization mechanisms with opposite temperature dependencies could also lead to a turnover, which would be beneficial to incorporate in future studies.

Due to their dynamic ionic lattices and the formation of polarons, the conventional band picture might not be applicable to charge transport in halide perovskites, as extensively investigated in the literature58,59. A treatment of exciton-phonon coupling that accounts for the highly anharmonic lattices of perovskites60 can enhance our quantitative understanding. However, polaron formation should influence the exciton transport in the NCSLs much less than charge transport in bulk. This is because the polar phonons interact with the overall charge distribution of both the electron and hole. In CsPbBr₃, the electron and hole effective masses are nearly equal, resulting in similar wavefunctions for the electron and hole within the exciton17. Due to the charge neutrality of excitons, the polaron effect is less significant. In fact, as demonstrated by long exciton coherence time on the order of 100 ps20,21,22, the coupling between excitons and the lattice is weak at low temperatures. Nonetheless, it is anticipated that the introduction of non-Gaussian statistics would not alter the qualitative conclusions drawn here.

Discussion

By imaging the spatial distribution of excitons with high temporal resolution over a broad temperature range, we have successfully elucidated quantum transport phenomena beyond classical exciton diffusion in networks of interacting CsPbBr3 NCs. Indeed, the MSD we measured in the NCSLs at low temperatures closely resemble quantum simulations using ultracold atoms in disordered lattices and superconducting qubit where ENAQT was simulated47,48. ENAQT has been predicted to be crucial for photosynthesis, where maximum energy transfer efficiency is anticipated to occur at approximately room temperature within the FMO protein complexes11. However, experimental evidence of quantum diffusion of excitons has remained elusive thus far. Our work provides clear evidence of turnover behavior in ENAQT, supported by self-consistent theoretical modeling. By employing perovskite NC superlattices, we were able to modulate quantum transport through adjustments in critical system parameters, such as exciton coupling. Additionally, we highlight that exciton transport relies exclusively on long-range dipolar coupling, which can lead to coherent transport even with insulating long-chain ligands. This makes it distinct from previously explored coherent charge transport in quantum dot superlattices using conductive ligands61. Perovskite NCs in the intermediate and weak confinement regimes possess properties that make them uniquely suitable for achieving coherent exciton transport, including large exciton oscillator strengths of bright triplet excitons and slow dephasing, which leads to the enhanced coherent exciton transport in NCSLs over bulk crystals at low temperatures. These same properties also make perovskite NCs attractive for generating quantum light, such as single photons and superfluorescence20,22,38.

We emphasize that ENAQT is a general phenomenon in system with disorder, and evidence of ENAQT in perovskite excitonic materials exist in previous publications, albeit without explicit discussion of ENAQT. For example, a turnover temperature between 100-200 K in diffusion constant was also observed in recent report on perovskite SLs30,31. Interestingly, a similar non-monotonic temperature-dependence in exciton diffusion, including a peak in the long-time diffusion constant around 60 K, was observed in 2D perovskite quantum wells62. While these reports31,62 attributed the turn over behavior to the exchange of populations between bright and dark exciton levels, we propose that such an exchange is unlikely to be important in our case. This is because, for CsPbBr3 NCs in the intermediate confinement regime, such as those employed in this study, the dark state is higher in energy than the bright state17,35,36. Furthermore, even if the exact energy level alignment is debatable, the relaxation to the dark state seems negligible for the NCs of 8–9 nm in size. This is supported by the single-exponential decay patterns observed in single-NC lifetime measurements at low temperatures17,20. A relaxation to the dark state would typically result in a bi-exponential decay pattern.

The understanding of exciton transport in the quantum regime can have profound implications for the development of optoelectronic devices based on excitonic materials as well as the design of artificial photosynthesis. For instance, as an extensive range of potential applications, such as light-emitting diodes63, solar cells64,65, lasers66,67, and quantum information68 have been proposed for perovskite NCs. Quantum effects can be leveraged to enhance the efficiency of these solid-state applications, because the efficiencies are critically dependent on the ability of excitons to migrate between NCs. Our results also serve as an important step towards developing more realistic theoretical models for quantum transport in complex materials. For instance, by combining the experimental and theoretical protocols, one possesses the means to directly probe the scaling laws of Anderson localization lengths in excitonic systems that is currently unavailable. Further theoretical analysis, incorporating quantum treatment of phonons, will be essential to fully comprehend the transient dynamics of exciton transport including the contraction in MSD due to coherent reflection of wavepackets.

Methods

Material preparation

Materials

Lead (II) bromide (98 + %, extra pure) was obtained from ACROS Organics, while anhydrous n-hexanes were purchased from Thomas Scientific. Hexanes (certified ACS), acetone (certified ACS, 99.5%), toluene (certified ACS, 99.5%), 2-propanol (certified ACS plus), didecyldimethylammonium bromide (98 + %), perfluoro(decahydronaphthalene) (95%), and methyl acetate ( + 99%, Extra Dry) were acquired from Fisher Scientific. Oleylamine (technical grade, 70%), oleic acid (technical grade, 90%), octadecene (technical grade, 90%), cesium carbonate (99.9%, trace metal basis), polymethylmethacrylate (120,000 MW), and Supelco PTFE tubing L × O.D. × I.D. 25 ft × 1/4 in. (6.35 mm) × 0.228 in. (5.8 mm) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Silicon/silicon dioxide wafers (90 nm, 4” Diameter, p-type) were obtained from Graphene Supermarket. All chemicals were used as received without further purification.

CsPbBr3 NC synthesis and purification

The CsPbBr3 NCs were synthesized following our previously reported procedure23. Briefly, cesium carbonate (0.204 g, 0.6 mmol) was degassed in oleic acid (0.625 mL, 2.0 mmol, OA) and octadecene (10 mL, ODE), followed by dissolution at 150 °C. Degassed OA (0.5 mL) and oleylamine (0.5 mL, OAm) were added to PbBr2 (0.069 g, 0.188 mmol) and degassed in ODE (5 mL). This solution was held at 120 °C until the PbBr2 dissolved and heated to 180 °C. Then, 0.5 mL of the cesium solution was injected, and the solution was immediately cooled. The NCs were isolated through centrifugation and resuspended in hexane.

DAB ligand exchange

Ligand exchanges were performed following a literature procedure with some modification69. The ligand exchange solution was prepared by dissolving 81 mg of DAB and 36.7 mg PbBr2 in 3 mL of toluene at 80 °C. For the ligand exchange, 150 µL of the NCs (about 7 µM), 150 µL of toluene, and 37.4 µL of DAB solution were stirred at room temperature for 1 h. To isolate the NCs, 345 µL of acetone was added, and the solution was centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 5 min. The NCs were resuspended in toluene.

Self-assembly of three-dimensional SLs via solvent evaporation

Solvent-evaporated superlattices (SLs) were synthesized following our previously reported procedure23. Briefly, 9–18 µL of 0.5 µM NCs in toluene was deposited on an 8 × 6 mm silica substrate and sealed in a glass jar in the glovebox until the toluene entirely evaporated.

Self-assembly of three-dimensional SLs via solvent diffusion

Solvent diffusion SLs were synthesized following a literature procedure with some modifications70. PTFE tube (about 3 cm) was placed in 0.5 mL of perfluoro(decahydronaphthalene) (PFD) in a 2 mL centrifuge tube. Then, 100 µL of 2 µM NCs in toluene was deposited inside the PTFE tube. Once the toluene layer was fully diffused, the PTFE tube was removed. The substrate was held in the PDF, and the solution was sonicated to transfer the SLs to the substrate. If excess PFD was present on the substrate, the substrate was rinsed with methyl acetate for 2 s to remove the PFD.

Structural characterization

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were acquired using a FEI Tecnai T20 TEM equipped with a 200 kV LaB6 filament. Optical images were acquired using an Olympus BX-51 Microscope with a tungsten lamp and DP71 CCD camera. UV-Vis data were collected using an Agilent Cary 6000i UV-Vis-NIR Spectrophotometer equipped with a PMT detector.

Estimation of dipolar coupling between NCs

The estimation of J follows the procedure outlined in the SI of Ref. 23. The calculation is outlined briefly below, but readers are encouraged to visit the SI of Ref. 23 for greater details. The transition dipole moment, \(\mu\), may be calculated as follows:

where n is the refractive index of CsPbBr3 (estimated as 1.875 for a 447 nm excitation energy)71,\(\,\epsilon\) is the extinction coefficient (estimated as 12.13 cm−1μM−1 for OA-1, 16.04 cm−1μM−1 for OA-2, 13.04 cm−1μM−1 for DAB-1 (and DAB-3), and 18.27 cm−1μM−1 for DAB-2, where NC sizes of OA-1, OA-2, DAB-1 (and DAB-3), and DAB-2 are 8.2 nm ± 1.3 nm, 9.0 nm ± 1.3 nm, 8.4 nm ± 1.4 nm, and 9.4 nm ± 1.7 nm respectively)72, \(\Delta v\) is the room temperature full width at half maximum of each SL at room temperature (measured as 87.84 meV for OA-1, 86.2 meV for OA-t2, 98.38 meV for DAB-1, 86.88 meV for DAB-2, and 85.01 meV for DAB-3), and \(v\) is the absorption maximum of a SL at room temperature (assumed to be 2.526 eV from a previous measurement on a representative CsPbBr3 NCSL)73. Evaluating the above expression, \(\mu\) is estimated be 85.2 D for OA-1, 97.09 D for OA-2, 93.5 D for DAB-1, 103 D for DAB-2 and 86.94 for DAB-3.

J may then be estimated using the following relation:

where \(\kappa\) is the orientation factor (assumed to be 2 based upon the expected head-to-tail alignment of dipoles within each SL), \({\varepsilon }_{0}\) is the vacuum permittivity (8.854\(\,\times \,\)10−12 Fm−1), and \(a\) is the distance between NCs within each SL (estimated as 11.2 nm, 12 nm, 9.9 nm and 10.9 nm for OA-1, OA-2, DAB-1 (and DAB-3), and DAB-2, respectively). Upon evaluation, J is estimated to be ~23 meV for OA-1, ~24 meV for OA-2, ~40 meV for DAB-1, ~37 meV for DAB-2 and ~35 meV for DAB-3.

Optical spectroscopy and microscopy

Time-resolved PL spectroscopy and microscopy

The superlattices (SLs) were placed inside a cryostat (Montana Instruments) with temperature stability < 10 mK and excited using a 447 nm laser beam (5 MHz repetition rate) with low fluence (180 nJ/cm2). PL spectra were obtained with a thermoelectric-cooled charge-coupled device (CCD, Andor Technology). Time-resolved PL dynamics were collected using a single photon avalanche diode (Pico-Quant, PDM series) and a time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) module. For diffusion measurements, the emission was magnified by 120x when using an objective with numerical aperture (NA) of 0.6 to measure SLs OA-1, DAB-1, and DAB-2. A magnification of 187.5x with an objective NA of 0.9 was used when performing power dependent measurements on DAB-3 (Supplementary Fig. 10). The magnified emission signal was then collected by a TCSPC module (Pico-Quant), which was placed on an electronic translational stage for obtaining spatial information. The exciton density employed for all PL measurements, including PL imaging for diffusion analysis, was 1.0\(\times\)1011 cm−2. The exciton density was calculated based on the measured absorption, beam size, and laser used. This density was chosen to effectively eliminate second-order effects, such as annihilation. Time resolution for the PL based measurements was determined by the instrument response function (IRF) and was about 70 ps.

Transient absorption microscopy (TAM)

Measurements were performed using a home-built set up whose details are described in previous manuscripts41. Briefly, an ultrafast amplifier laser system (PHAROS, Light Conversion), with a repetition rate of 750 kHz was used to pump two OPAs (TOPAS-Twins, Light Conversion) to generate a pump wavelength of 490 nm and a probe wavelength of 510 nm. The pump and probe were focused onto the SL using a 40x objective (NA 0.6) after using spatial filters to permit a diffraction-limited beam size. An acoustic optical modulator (AOM, R23080-1, Gooch and Housego) was used to modulate the pump to 100 kHz while the probe’s arrival time to the sample surface with respect to the pump beam was controlled using a mechanical translation stage (DDS600-E, Thorlabs). The experiment was performed in reflection mode where the change in the reflected probe beam was collected using an avalanche photodiode (APD, C5331-04, Hamamatsu) with a lock-in amplifier (SR830, Stanford Research Systems). A set of two galvo mirrors (GVS012, Thorlabs) were used to scan the probe beam across the sample while keeping the pump position constant. The exciton density utilized for TAM measurements was maintained at 3.6\(\times\)1012 cm-2. Time resolution for the TAM based measurements was mostly determined by the laser pulse width ( ~ 200 fs).

Theory and simulation

To qualitatively simulate the exciton transport in the perovskite NCSL, we adopt the Frenkel exciton model where each NC is treated as a two-level system representing its electronic ground and excited states. For simplicity we restrict ourselves to a one-dimensional SL of NC with nearest-neighbor coupling and leave the effects of higher dimensionality and long-range coupling to future studies. The effects of static disorder and dynamical noise, present in the experiment, are accounted for using the Anderson Hamiltonian and the Haken-Strobl-Reineker model, respectively. The system Hamiltonian is written as

where J is the exciton coupling strength, \(|n\rangle\) represents the state where the nth NC is in its electronic excited state with all others in the ground state, \({\epsilon }_{n}\) is the time-independent energy gap of the NC, and \({\xi }_{n}\left(t\right)\) is its time-dependent part. The effects of disorder and noise are accounted for by the statistical properties of the latter two quantities. Explicitly,

Here brackets represent ensemble averages, \({\delta }_{{nm}}\) is the Kronecker delta, \(\delta \left(t\right)\) is the Dirac delta function. \(\Delta\) and \(\varGamma\) are the two parameters specifying the strengths of the disorder and the noise, respectively74,75,76. Both terms are sampled from zero-mean Gaussian processes with the corresponding variances. While the noise term is purely real and does not account for quantum dissipation of the environment, one can approximately associate the magnitude of \(\varGamma\) to the temperature of the system. For detailed discussions of this model and its extension to higher dimensions, we refer the interested readers to view works by Moix 20137, Lee 201552, and Chuang 20169.

In simulating the transport properties of the above-mentioned model, we initiate the exciton wavefunction as a Kronecker delta, \(|\psi \left(t=0\right)\rangle={\sum }_{n}{\delta }_{0n}{|n}\rangle=|0\rangle\). The wavepacket then expands outward due to the exciton couplings while subject to disorder and noise effects by propagating the time-dependent Schrodinger equation, corresponding to the quantum transport of excitons8. To properly compare with the experiments, we measure the wavepacket expansion by the corresponding mean-squared displacement (MSD) and its time-derivative, the diffusivity, D(t).

MSD and the corresponding diffusivity are defined for each individual trajectory. However, in our experiment the number of NC in each SL involved is typically on the order of 104, reasonably large that one can expect significant averaging over disorder and noise realizations occurs. Consequently, the numerical results presented here are obtained after ensemble averaging over both disorder and noise.

Data availability

All data supporting this study can be found within the paper and the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Codes that supports the findings of this study are available. The Matlab codes (and exemplary data files) which generated the Haken-Strobl-Reineker model results in this study have been deposited on Github and are publically accessible [https://github.com/chernchuang/HakenStroblReineker].

References

Anderson, P. W. Absence of diffusion in certain random lattices. Phys. Rev. 109, 1492–1505 (1958).

Lukin, A. et al. Probing entanglement in a many-body–localized system. Science 364, 256–260 (2019).

Maier, C. et al. Environment-assisted quantum transport in a pi 10-qubit network. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 050501 (2019).

Walschaers, M., Schlawin, F., Wellens, T. & Buchleitner, A. Quantum transport on disordered and noisy networks: an interplay of structural complexity and uncertainty. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 7, 223–248 (2016).

Chien, C.-C., Peotta, S. & Di Ventra, M. Quantum transport in ultracold atoms. Nat. Phys. 11, 998–1004 (2015).

Quiroz-Juárez, M. A. et al. Reconfigurable network for quantum transport simulations. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 013010 (2021).

Moix, J. M., Khasin, M. & Cao, J. Coherent quantum transport in disordered systems: I. the influence of dephasing on the transport properties and absorption spectra on one-dimensional systems. N. J. Phys. 15, 085010 (2013).

Zhong, X., Zhao, Y. & Cao, J. Coherent quantum transport in disordered systems: II. temperature dependence of carrier diffusion coefficients from the time-dependent wavepacket diffusion method. N. J. Phys. 16, 045009 (2014).

Chuang, C., Lee, C. K., Moix, J. M., Knoester, J. & Cao, J. Quantum diffusion on molecular tubes: universal scaling of the 1D to 2D transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 196803 (2016).

Aragó, J. & Troisi, A. Regimes of exciton transport in molecular crystals in the presence of dynamic disorder. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 2316–2325 (2016).

Rebentrost, P., Mohseni, M., Kassal, I., Lloyd, S. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Environment-assisted quantum transport. N. J. Phys. 11, 033003 (2009).

Zerah-Harush, E. & Dubi, Y. Universal origin for environment-assisted quantum transport in exciton transfer networks. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 1689–1695 (2018).

Kassal, I., Yuen-Zhou, J. & Rahimi-Keshari, S. Does coherence enhance transport in photosynthesis? J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 362–367 (2013).

Raino, G. et al. Superfluorescence from lead halide perovskite quantum dot superlattices. Nature 563, 671–675 (2018).

Cherniukh, I. et al. Perovskite-type superlattices from lead halide perovskite nanocubes. Nature 593, 535–542 (2021).

Akkerman, Q. A., Raino, G., Kovalenko, M. V. & Manna, L. Genesis, challenges and opportunities for colloidal lead halide perovskite nanocrystals. Nat. Mater. 17, 394–405 (2018).

Becker, M. A. et al. Bright triplet excitons in caesium lead halide perovskites. Nature 553, 189–193 (2018).

Krieg, F. et al. Monodisperse long-chain sulfobetaine-capped CsPbBr(3) nanocrystals and their superfluorescent assemblies. ACS Cent. Sci. 7, 135–144 (2021).

Lee, E. M. Y., Tisdale, W. A. & Willard, A. P. Perspective: nonequilibrium dynamics of localized and delocalized excitons in colloidal quantum dot solids. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 36, 068501 (2018).

Utzat, H. et al. Coherent single-photon emission from colloidal lead halide perovskite quantum dots. Science 363, 1068–1072 (2019).

Sun, W. et al. Elastic phonon scattering dominates dephasing in weakly confined cesium lead bromide nanocrystals at cryogenic temperatures. Nano Lett. 23, 2615–2622 (2023).

Kaplan, A. E. K. et al. Hong–Ou–mandel interference in colloidal CsPbBr3 perovskite nanocrystals. Nat. Photonics 17, 775–780 (2023).

Blach, D. D. et al. Superradiance and exciton delocalization in perovskite quantum dot superlattices. Nano Lett. 22, 7811–7818 (2022).

Akselrod, G. M. et al. Subdiffusive exciton transport in quantum dot solids. Nano Lett. 14, 3556–3562 (2014).

Lorenzon, M. et al. Improved stability and exciton diffusion of self-assembled 2D lattices of inorganic perovskite nanocrystals by atomic layer deposition. Adv. Optical Mater. 8, 2000900 (2020).

Yoon, S. J., Guo, Z., Dos Santos Claro, P. C., Shevchenko, E. V. & Huang, L. Direct imaging of long-range exciton transport in quantum dot superlattices by ultrafast microscopy. ACS Nano 10, 7208–7215 (2016).

Giovanni, D. et al. Origins of the long-range exciton diffusion in perovskite nanocrystal films: photon recycling vs exciton hopping. Light.: Sci. Appl. 10, 2 (2021).

Gutiérrez Álvarez, S. et al. Charge carrier diffusion dynamics in multisized quaternary alkylammonium-Capped CsPbBr3 perovskite nanocrystal solids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 44742–44750 (2021).

Yang, M. et al. Energy transport in CsPbBr3 perovskite nanocrystal solids. ACS Photonics 7, 154–164 (2020).

Shcherbakov-Wu, W. et al. Persistent enhancement of exciton diffusivity in CsPbBr3 nanocrystal solids. Sci. Adv. 10, eadj2630 (2024).

Bornschlegl, A. J. et al. Dark-bright exciton splitting dominates low-temperature diffusion in halide perovskite nanocrystal assemblies. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2303312 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Ultrafast exciton transport at early times in quantum dot solids. Nat. Mater. 21, 533–539 (2022).

Wan, Y. et al. Cooperative singlet and triplet exciton transport in tetracene crystals visualized by ultrafast microscopy. Nat. Chem. 7, 785–792 (2015).

Protesescu, L. et al. Nanocrystals of cesium lead halide perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, and I): novel optoelectronic materials showing bright emission with wide color gamut. Nano Lett. 15, 3692–3696 (2015).

Sercel, P. C. et al. Exciton fine structure in perovskite nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 19, 4068–4077 (2019).

Rossi, D. et al. Size-dependent dark exciton properties in cesium lead halide perovskite quantum dots. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 184703 (2020).

Spano, F. C. & Mukamel, S. Superradiance in molecular aggregates. J. Chem. Phys. 91, 683–700 (1989).

Rainò, G., Utzat, H., Bawendi, M. G. & Kovalenko, M. V. Superradiant emission from self-assembled light emitters: from molecules to quantum dots. MRS Bull. 45, 841–848 (2020).

Tighineanu, P. et al. Single-photon superradiance from a quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 163604 (2016).

Clark, D. E. et al. Quantifying structural heterogeneity in individual CsPbBr3 quantum dot superlattices. Chem. Mater. 34, 10200–10207 (2022).

Deng, S., Blach, D. D., Jin, L. & Huang, L. Imaging carrier dynamics and transport in hybrid perovskites with transient absorption microscopy. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1903781 (2020).

Zhong, J. et al. Shape of the quantum diffusion front. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 2485–2489 (2001).

Penzo, E. et al. Long-range exciton diffusion in two-dimensional assemblies of cesium lead bromide perovskite nanocrystals. ACS Nano 14, 6999–7007 (2020).

Dai, J. et al. Charge transport between coupling colloidal perovskite quantum dots assisted by functional conjugated ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 5754–5758 (2018).

van der Laan, M. et al. Photon recycling in CsPbBr3 all-inorganic perovskite nanocrystals. ACS Photonics 8, 3201–3208 (2021).

Gan, Z. et al. External stokes shift of perovskite nanocrystals enlarged by photon recycling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 011906 (2019).

Kondov, S. S., McGehee, W. R., Zirbel, J. J. & DeMarco, B. Three-dimensional Anderson localization of ultracold matter. Science 334, 66–68 (2011).

Karamlou, A. H. et al. Quantum transport and localization in 1d and 2d tight-binding lattices. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 1–8 (2022).

Glazov, M. M. Quantum interference effect on exciton transport in monolayer semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 166802 (2020).

Glazov, M. M., Iakovlev, Z. A. & Refaely-Abramson, S. Phonon-induced exciton weak localization in two-dimensional semiconductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 192106 (2022).

Kramers, H. A. Brownian motion in a field of force and the diffusion model of chemical reactions. Physica 7, 284–304 (1940).

Lee, C. K., Moix, J. & Cao, J. Coherent quantum transport in disordered systems: a unified polaron treatment of hopping and band-like transport. J. Chem. Phys. 142, 164103 (2015).

Ciuchi, S., Fratini, S. & Mayou, D. Transient localization in crystalline organic semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 83, 081202 (2011).

Aragó, J. & Troisi, A. Dynamics of the excitonic coupling in organic crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 026402 (2015).

Giannini, S. et al. Exciton transport in molecular organic semiconductors boosted by transient quantum delocalization. Nat. Commun. 13, 2755 (2022).

Sneyd, A. J., Beljonne, D. & Rao, A. A new frontier in exciton transport: transient delocalization. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 6820–6830 (2022).

Fratini, S., Mayou, D. & Ciuchi, S. The transient localization scenario for charge transport in crystalline organic materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 2292–2315 (2016).

Schilcher, M. J. et al. The significance of polarons and dynamic disorder in halide perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 2162–2173 (2021).

Lacroix, A., de Laissardière, G. T., Quémerais, P., Julien, J.-P. & Mayou, D. Modeling of electronic mobilities in halide perovskites: adiabatic quantum localization scenario. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 196601 (2020).

Debnath, T. et al. Coherent vibrational dynamics reveals lattice anharmonicity in organic–inorganic halide perovskite nanocrystals. Nat. Commun. 12, 2629 (2021).

Lan, X. et al. Quantum dot solids showing state-resolved band-like transport. Nat. Mater. 19, 323–329 (2020).

Ziegler, J. D. et al. Fast and anomalous exciton diffusion in two-dimensional hybrid perovskites. Nano Lett. 20, 6674–6681 (2020).

Jiang, Y. et al. Synthesis-on-substrate of quantum dot solids. Nature 612, 679–684 (2022).

Chen, J., Jia, D., Johansson, E. M. J., Hagfeldt, A. & Zhang, X. Emerging perovskite quantum dot solar cells: feasible approaches to boost performance. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 224–261 (2021).

Zhao, Q. et al. High efficiency perovskite quantum dot solar cells with charge separating heterostructure. Nat. Commun. 10, 2842 (2019).

Park, Y.-S., Roh, J., Diroll, B. T., Schaller, R. D. & Klimov, V. I. Colloidal quantum dot lasers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 382–401 (2021).

Zhou, C. et al. Quantum dot self-assembly enables low-threshold lasing. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 8, e2101125 (2021).

Kagan, C. R., Bassett, L. C., Murray, C. B. & Thompson, S. M. Colloidal quantum dots as platforms for quantum information science. Chem. Rev. 121, 3186–3233 (2021).

Stelmakh, A., Aebli, M., Baumketner, A. & Kovalenko, M. V. On the mechanism of alkylammonium ligands binding to the surface of CsPbBr3 nanocrystals. Chem. Mater. 33, 5962–5973 (2021).

Baranov, D., Toso, S., Imran, M. & Manna, L. Investigation into the photoluminescence red shift in cesium lead bromide nanocrystal superlattices. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 655–660 (2019).

He, S. et al. Tailoring the refractive index and surface defects of CsPbBr3 quantum dots via alkyl cation-engineering for efficient perovskite light-emitting diodes. Chem. Eng. J. 425, 130678 (2021).

Maes, J. et al. Light absorption coefficient of CsPbBr(3) perovskite nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 3093–3097 (2018).

W. W. Parson et al., Modern Optical Spectroscopy. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2015).

P. R. Vasudev M. Kenkre, Exciton Dynamics in Molecular Crystals and Aggregates. Springer Tracts in Modern Physics (Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, ed. 1, 1982).

Madhukar, A. & Post, W. Exact Solution for the diffusion of a particle in a medium with site diagonal and off-diagonal dynamic disorder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 39, 1424–1427 (1977).

Jayannavar, A. M. & Kumar, N. Mooij correlation in disordered metals. Phys. Rev. B 37, 573–576 (1988).

Acknowledgements

This work is primarily supported by the National Science Foundation grant 2004339, 2324299 (D.D.B., V.A.L.-R., D.E.C., S.D., O.F.W., C.W.L., L.H.) and 23242101 (J.C). Part of instrument is constructed with support from National Science Foundation grant 2117616.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.H. designed the experiments. D.D.B., V.A.L.-R., S.D., and O.F.W. carried out the optical measurements and analyzed the data. J.C. and C.C. completed theoretical calculations. D.E.C. and C.W.L. prepared samples and performed structural characterization. D.D.B., V.A.L.-R., C.C., J.C., and L.H. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Blach, D.D., Lumsargis-Roth, V.A., Chuang, C. et al. Environment-assisted quantum transport of excitons in perovskite nanocrystal superlattices. Nat Commun 16, 1270 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55812-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55812-8