Abstract

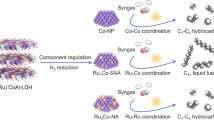

Solar-driven CO2 reduction to value-added C2 chemicals is thermodynamically challenging due to multiple complicated steps. The design of active sites and structures for photocatalysts is necessary to improve solar energy efficiency. In this work, atomically dispersed Ru-O sites in RuxIn2-xO3 are constructed by interior lattice anchoring of Ru. This results in the dynamic reconstruction of Ruδ+-O/Ru0-O sites upon photoexcitation, which facilitates the CO2 activation, *CO intermediates adsorption, and C-C coupling as demonstrated by varied in situ techniques. A SiO2 core in RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 construction further enhances the solar energy utilization and individual RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystals dispersion for photocatalytic CO2 reduction reaction. It results in the maximum ethanol production rate up to 31.6 μmol/g/h with over 90% selectivity. DFT simulation reveals that the C2 dimer formation primarily underwent an asymmetric *CO-*CHO coupling route via a low-energy precedence ladder of *CHO. This work provides an insightful understanding of active sites with dynamic reconstruction towards asymmetric C-C coupling for CO2RR at the atomic scale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solar-driven carbon dioxide (CO2) reduction to value-added chemicals is a desirable approach towards carbon neutralization1,2,3. For comparison, C2+ chemicals produced from CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR), such as ethanol and ethylene, are more desirable than C1 chemicals like methane, carbon monoxide, and methanol, due to the merit of higher-energy density4,5. During the CO2RR process to produce C2+ chemicals, beyond the energy required for the dissociation of the inert C=O bond (~750 kJ/mol) and activation of intermediates, additional energy is needed to drive the C–C coupling step, leading to the formation of carbonous dimers (such as *CO-*CO and *CO-*CHO)6,7. Additionally, to facilitate C-C coupling, it is essential to increase the coverage of *C1 species (such as *CO and *CHO) and reduce the adsorption energy of CO on the active sites to enhance carbon-based dimer formation8,9,10. These thermodynamic and kinetic challenges make a photocatalytic reduction of CO2 into C2+ chemicals an exceptionally difficult process.

In a photocatalysis system, only a fraction of solar energy is absorbed to generate charge carriers for photocatalysts, leading to inefficient utilization of solar energy (Supplementary Fig. S1)11. Core-shell is a distinctive catalyst structure designed to enhance solar energy efficiency, where either the outer shell or the inner core of the photocatalysts helps reduce light energy loss via secondary irradiation12,13. Hence, a silica-based core-shell system has been applied in the CO2 hydrogenation reaction14,15,16.

The actual physical and chemical states of the metal active center play a crucial role in multi-step CO2RR towards C2+ chemicals production. For CO2RR on copper-based catalysts, the metallic species (Cu0) exhibit thermodynamically favorable activation of CO2 compared with oxidized species, while Cuδ+ species in a higher oxidation state serve as indispensable sites for C-C coupling step17,18,19. Moreover, a suppressed generation of Cu0 led to the insufficiency of Cu0-Cuδ+ pairs for C2+ production18,20. Notably, the synergistic reconstruction of Cu0 and Cuδ+ species effectively completes the complicated CO2 conversion to C2+ chemicals. However, the dynamic reconstruction nature of catalysts beyond Cu has rarely been unveiled for photocatalytic CO2RR. With an abundant supply of electrons in its d orbital that can participate in the formation of d-π* antibonding with CO2, Ruthenium (Ru) has been recognized as a highly active metal center for CO2RR21,22. Nevertheless, CO2RR into C2+ chemicals has rarely been achieved on Ru-based photocatalysts, likely due to the limited understanding of the dynamic construction of Ru catalysts. Recently, single-atom catalysts (SAC) with unsaturated coordination or hemilability have been extensively adopted for CO2RR because of the merit of high atomic efficiency, high catalytic efficiency, and unique reaction selectivity23,24,25. More importantly, the nature of the isolated catalytic center for SAC enables the investigation of the dynamic reconstruction of photocatalysts during the CO2RR process.

In this work, we synthesized RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystals with Ru atomically dispersed within In2O3 lattice, serving as a model photocatalyst to investigate the dynamic reconstruction of active sites and the resultant reaction pathway for photocatalytic CO2RR. Multiple techniques (STEM, XANES, Raman et al.) revealed that Ru atoms anchored within the lattice exist in a single-atom state, exhibiting unsaturated coordination with adjacent O to form Ruδ+-O sites. The improved productivity of C2 chemical (ethanol) from CO2RR confirms the synergy between enhanced solar energy utilization and effective dispersion of individual active nanocrystals in such RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 core-shell structure. In situ XPS, DRIFTS and Raman spectroscopy unveiled a dynamic reconstruction between Ru0-O and Ruδ+-O: the metallic state Ru0-O site exhibited thermodynamically favorable activation of CO2, providing high coverage and low adsorption energy of *CO species on the active sites, while the oxidized state of Ruδ+-O facilitated the intermediates stabilization and C-C coupling. Under solar irradiation, the local electron redistribution in the Ru-O-In sites resulted in the transient acid-base pairs generation, which promoted CO2 activation, intermediates regulation and C-C coupling. Consequently, this dynamic reconstruction enabled the solar-driven RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 to convert CO2 into ethanol with a maximum productivity of 31.6 μmol/g/h and a selectivity greater than 90%. Density functional theory (DFT) simulation further revealed the dominant *CO-*CHO dimerization pathway for ethanol production.

Results

Morphology and Structure analysis of catalysts

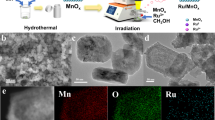

A series of RuxIn2-xO3 (x = 0%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 3.0%, and 5.0%) nanospheres were synthesized by varying the amount of Ru3+ precursor (Supplementary Fig. S2). Typically, the average size of pure In2O3 was ~58 nm (Supplementary Fig. S3), whose main exposed lattice fringes were (222) and (400) facets with space of 0.292 nm and 0.253 nm, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S4). Because of the smaller radius of Ru3+ (0.68 Å) compared to In3+ (0.81 Å), the incorporation of Ru3+ into In2O3 resulted in a smaller size of RuxIn2-xO3 nanosphere, with the 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 nanosphere, for example, measuring around 52 nm (Supplementary Fig. S5). The corresponding (222) facet in 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 exhibited a slightly smaller interplanar spacing of 0.286 nm compared with bcc In2O3 (0.292 nm) (Supplementary Fig. S6). Moreover, Ru atoms presented a homogeneous dispersion in the 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystal with no obvious evidence of metallic Ru and RuO2 characteristic fringes (Supplementary Fig. S6). Additionally, the incorporation of smaller Ru ions within RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystals resulted in a larger-surface area compared with pure In2O3 (Supplementary Fig. S7), thereby providing more adsorption sites for CO2 photoreduction. To enhance the photothermal effect and ensure the dispersion of individual nanocrystal, a RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 core-shell structure was fabricated, aiming to reduce solar energy loss and improve the interaction of active site with adsorbates. Herein, amorphous silica acted as the core, and its larger surface (size of ~0.64 μm) (Supplementary Fig. S8) provided more planting-bed sites for the agglomeration of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystals (Supplementary Fig. S2). This allowed individual RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystal to be efficiently dispersed onto the larger surface support, further boosting the interaction with adsorbates (CO2). As shown in Fig. 1a–d and Supplementary Fig. S9, these images confirm a core-shell structure of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 shell with SiO2 core. The 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystals were closely attached to the surface of SiO2. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy line scanning (Fig. 1f, g) and elemental mapping (Fig. 1h) images further proved that the 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystals were uniformly dispersed on the SiO2 support. Furthermore, atomic force microscopy demonstrated the arc shape of the core-shell 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 /SiO2 surface (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. S10). The Ru mole proportion in each RuxIn2-xO3 series nanocrystals were measured by the inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) (Supplementary Table S1).

a, b TEM and d HRTEM images of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 nanocrystal (inset: relevant FFT pattern of (222) facet), and c corresponding lattice space of (222) facet; e Line-scanning profile of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 surface from 2D AFM image in Supplementary Fig. S10 and corresponding 3D AFM image (bottom); f HAADF-STEM image, and corresponding g line-scanning elemental distribution profile along red line in (f), and h relevant elemental mappings of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 nanocrystal.

The crystal phase structure of the as-synthesized catalysts was investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Supplementary Fig. S11). All the characterized peaks of RuxIn2-xO3 series samples matched with the identical XRD patterns of cubic In2O3, with the primary (222) facet. Due to its smaller radius in contrast with In inos mentioned above, the incorporation of Ru ions into RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystals led to a larger 2 theta shift of (222) facet compared to pure In2O3, which contributed to internal lattice disrtortion. All the RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystals’ XRD patterns showed no obvious characteristic peaks related to metallic Ru and RuO2. The extended shoulder of the characterized peak around 2 theta of 21° (Supplementary Fig. S12) attributed to amorphous silica (Supplementary Fig. S13) confirmed the formation of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 composite. The crystal structure of catalysts was further supported by Raman spectra. As displayed in Supplementary Fig. S14, all the peaks located in 130.6, 307.2, 367.1, 494.8, and 627.9 cm−1 are identically indexed to the E2g, E1g, and A1g vibration models of In2O3, respectively26. Significantly, an obvious B2g vibration peak at 740.5 cm−1 assigned to the in-plane Ru-O mode indicates that Ru atoms are bonded with adjacent O in RuxIn2-xO327, moreover, the intensity of B2g peak increased with higher Ru contents. Interestingly, the intensity of B2g peak decreased at Ru mole proportion above 3.0%, likely due to excessive Ru3+ ions aggregating into metallic Ru-Ru bonds instead of forming Ru-O bonds (Supplementary Fig. S15). Taking into consideration of above XRD and Raman discussion, the Ru configuration in RuxIn2-xO3 probably was interior lattice anchoring. To deepen insights into the chemical state of Ru and electron redistribution of Ru-(O)-In sites, high-resolution spectra of Ru 3 d, In 3 d, and O 1 s were investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). As shown in Fig. 2a, Ru predominantly existed in the oxide state of RuOx, and with a minor presence of metallic state Ru0 in 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 sample28,29. Particularly, the Ru 3d5/2 peak corresponding to the oxide state in 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 exhibted a slight ~0.41 eV shift to lower binding energy compared with that in RuO2, indicating a lower oxide state of Ruδ+ realtive to Ru4+30. In other words, Ruδ+ probably coordinated with O in an unsaturated state in contrast to Ru-O bonding in RuO2. Additionally, oxide states in O 1 s and In 3 d spectra displayed a slight ~0.55 eV and ~0.61 eV shift to higher binding energy (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. S16) compared to those in In2O3. This further proved that smaller Ru ions could attract more electrons from neighboring In and O atoms (Fig. 2c), ultimately leading to electron redistribution and accumulation at the local Ru-(O)-In sites.

High-resolution XPS spectra of a Ru 3 d + C 1 s and b O 1 s; c Schematic illustration of electrons redistribution in local In-O site of pure In2O3 (bottom) and Ru-O-In site of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 (top); d HAADF-STEM images of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystal, and e corresponding 3D surface plot of yellow-dotted area (insert: atomic profile of white-line scanning). f Normalized Ru K-edge XANES spectra (insert: enlarged pink area) and g corresponding k2-Weighted Ru K-edge Fourier-transform EXAFS spectra; h Normalized In K-edge XANES spectra and i corresponding k2-Weighted In K-edge Fourier-transform EXAFS spectra of In2O3, 0.5%RuxIn2-xO3, 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 and 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 nanocrystals respectively, as well as Ru foil, RuO2 and In foil references. j Schematic illustration of In-O bond length (RIn-O) in pure In2O3 (top), and Ru-O bond length (RRu-O) in 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 (middle) and RuO2 (bottom) (purple: In; red: O; cyan: Ru; black: oxygen vacancy).

To deepen insights into the Ru configuration in RuxIn2-xO3, spherical aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) images further unveiled homogenously atomical dispersion of Ru atoms with a lower contrast compared to In atoms (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. S17), wherein atomic Ru anchored into the interior lattice site to form Ru-(O)-In configuration (Fig. 2e). Furthermore, the brightness-faded area observed after Ru incorporation suggested unsaturated coordination, probably deriving from O vacancies. The electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra (Supplementary Fig. S18) revealed the existence of paramagnetic oxygen vacancy species (g = 2.003), thereby further providing insightful evidence for unsaturated Ru-O coordination30. To further investigate the electronic structure and coordination environment of Ru and In atoms in RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystals, the X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra of Ru and In were obtained in Fig. 2f–i, respectively. From the Ru K-edge XANES spectra of RuxIn2-xO3, the near absorption edge (pink area) appeared at a slightly lower energy than that of RuO2 (Fig. 2f), indicating that the chemical state of Ru in RuxIn2-xO3 is lower than +4. Additionally, the white-line peak of Ru-O in RuxIn2-xO3 exhibited both a lower energy position and reduced intensity compared to RuO2. This suggests more electrons geometrically deviated from neighboring In and O to Ru 3 d orbitals, enhancing the electron donation for dynamic Ruδ+ reduction and CO2 activation. This intriguing electron redistribution around Ru-(O)-In sites was further proved by the higher-energy shift of In-O peak in the In K-edge XANES spectra of RuxIn2-xO3 (Fig. 2h) compared with that of In2O3 as well. The above discussion is also in accordance with the aforementioned XPS analysis. The Fourier-transformed k2-weighted EXAFS analysis unveiled that a dominant peak at 1.67 Å (Fig. 2g) was assigned to the near-shell coordination of Ruδ+-O bonding in 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystal. Further EXAFS spectra fitting (Supplementary Figs. S19–S26 and Supplementary Tables S2, S3) determined the accurate Ruδ+-O bond length to be 2.06 Å, which is longer than Ru4+-O bond (1.98 Å) in RuO2 and shorter than In3+-O bond (2.18 Å) in In2O3 (Fig. 2j). This is attributed to the radius of Ruδ+ was longer than Ru4+ and shorter than In3+, respectively. The fact of the shortened Ru-O bond length in RuxIn2-xO3 compared to In-O bond in In2O3 was in good agreement with the simulated geometry structure (Supplementary Fig. S27). This change would contribute to the lattice distortion of (222) facet in RuxIn2-xO3 (Supplementary Fig. S11). From the EXAFS data fitting table (Supplementary Table S2), the Ru atoms are coordinated with neighber O (Ru-O) and In (Ru-In) due to the interior lattice anchoring (Fig. 2d). Moreover, the Ru-O coordination in 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 presented a lower coordination number of 2 compared to saturated coordination of Ru(4+)-O (6) in RuO2 as well as In(3+)-O (6) in In2O3 standard4,23. This unsaturated coordination state may derive from the formation of adjacent oxygen vacancies (Supplementary Fig. S18). In addition, due to the Ru incoporation, the related In-O and In-In coordination in RuxIn2-xO3 framework appeard a slight decline (Supplementary Table S3), which can be attributed to electron delocalization from O and In4. It is worth noting that the SiO2 core combining with 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 basically had a negligible influence on the Ru and In atoms coordination environment (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). Interestingly, because of the electron redistribution around Ru-(O)-In sites, the CO2 and NH3 temperature-programmed desorption (CO2/NH3-TPD) spectra revealed a strengthened acid-base pair formation in RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystals in contrast with pure In2O3 (Supplementary Fig. S28), which could provide abundant adsorption sites for the CO2 activation.

The density of state (DOS) was analyzed to gain insights into the electronic structure of RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystals. Because of the interior lattice anchoring of Ru into RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystals, the d orbitals of Ru would hybridize with the O p orbitals, leading to a defective structure with a visible signature below the conduction band (Fig. 3a, b). This defective state formation led to the darkened color of the RuxIn2-xO3 catalysts (Supplementary Fig. S29), enhancing the absorption of photons (Supplementary Fig. S30). On the other hand, due to the strong interaction of Ru d orbitals with the 2π orbitals of CO2 (Fig. 3c), more electrons infused into the bonding state (d-π) below Fermi level (Fig. 3d, e, and Supplementary Fig. S31), which resulted in a strong interaction between CO2 and Ru-O site, further boosting the C = O bond dissociation.

a Simulated DOS plots of In2O3 (left) and RuxIn2-xO3 (right), and b relevant schematic illustration of defective energy level formation from hybridization of Ru d orbital and O p orbital; c pDOS simulation plot of Ru orbitals (including s, p, and d) in RuxIn2-xO3 hybridizing with CO2 orbitals (including s and p), and d corresponding schematic illustration dxz/yz-π bonding orbital deriving from Ru-CO2; e Charge difference plots for side-view CO2 adsorbed on RuxIn2-xO3 (right) and In2O3 (left) models (The yellow and blue contours represent electron density accumulation and depression, respectively).

To decipher the mechanism of photogenerated charge carriers transfer dynamics induced by the defective state after Ru incorporation, the femtosecond transient absorption (fs-TA) spectroscopy was carried out to track electrons transfer from the excited state to trap or interfacial state31. The fs-TA spectra of In2O3 and 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 with a range of 425–750 nm are demonstrated in Fig. 4a, b, d, e, wherein both a minor ground-state bleach and a prominent photoinduced absorption (PIA) process could be observed at different time delays. The PIA is related to the absorption of excited-state electrons generated in conduction band32. Due to the Ru incorporation, the PIA of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 (on set at 465 nm) appeared a slight blue-shift compared with that of In2O3 (on set at 500 nm), which suggests the Ru incorporation is favarable for the PIA process under illumination. Furthermore, a more comparable absorbance of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 revealed more charge carriers generated upon light absorption in contrast with In2O3, due to the defect level formation. To give a quantitative description of charge carriers transfer dynamics, we focused on the major PIA relaxation dynamics in Fig. 4a, d. The triexponential fitting based on the dynamics curve probed at 630 nm yields the relaxation time constants (and weighted coefficients) (Fig. 4c, f): τ1 = 2.9 ± 0.2 ps (88.0%), τ2 = 33.6 ± 3.3 ps (10.0%), and τ3 = 837.1 ± 187.2 ps (2.0%) for In2O3; and τ1 = 1.9 ± 0.2 ps (97.4%), τ2 = 21.7 ± 1.7 ps (2.3%), and τ3 = 412.7 ± 65.2 ps (0.3%) for 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 (Supplementary Table S4). Because the charge trapping and radiative recombination usually occurs at a picosecond and nanosecond time scale, respectively, we attributed the relaxation time constants to the event of electron trapping at different depth (τ1 and τ2) and non-radiative recombination (τ3)33. Notably, faster PIA relaxation time constants associated with electron trapping could be affirmed in 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3. This suggets that the defective energy level arisen from Ru incorporation benefits photoinduced electron trapping, faciliating dissociation into free electrons (Supplementary Fig. S32). Consequently, the accelerated charge separation contributed to enhanced photocurrent density (Supplementary Fig. S33). Although photogenerated charge underwent a relative fast non-radiative recombination in 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 compared with In2O3, the weight ratio merely accounts for 0.3%. Taken together, the aforementioned discussion demonstrates that a unique defective level continuation attributed to Ru incorporation accelerates electron trapping and charge separation, thereby endowing photogenerated electrons with more opportunity to reduce Ruδ+ species and activate CO2.

Normalized transient adsorption kinetic decay curves, contour maps fs-TA spectra, and relevant PIA relaxation dynamics curve of (a–c) In2O3 and (d–f) 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3, respectively (excitation at 400 nm and probe at 630 nm); 3D KPFM images of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 catalyst under dark g and illumination (h, i) with different monochromatic wavelength (h: λ = 420 nm, i: λ = 532 nm).

To verify the efficient photogenerated charges carriers transfer onto surface, Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) was performed under dark and illumination with different monochromatic wavelengths, respectively (Fig. 4g–i and Supplementary Fig. S34). As shown in Supplementary Fig. S35, the line-scanning plots of charge distribution demonstrated that the average surface charge of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 is ~−122 mV under dark. While, that shifts to −379 mV (λ = 420 nm) and −248 mV (λ = 532 nm) under illumination, respectively. This directly verified that abundant active electrons were induced onto the catalyst surface under light, which provided reliable evidence of a negative charge microenvironment for 12e-required CO2 photoreduction to ethanol (\(2{{CO}}_{2}+12{H}^{+}+12{e}^{-}\to {C}_{2}{H}_{5}{OH}+3{H}_{2}O\)).

Photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance

The photocatalytic CO2RR performance over RuxIn2-xO3 series catalysts was evaluated in a gas–liquid–solid three phases system. From Supplementary Figs. S36–S38, the possible products include C1 (CO, CH4 and HCOOH) and C2 (C2H4, C2H6, and CH3CH2OH) chemicals. Notably, because of the absence of active Ruδ+(-O) sites for C-C coupling in pure In2O3, there is no C2 chemicals production. While, a good productivity of ethanol was obtained in the RuxIn2-xO3 series catalysts (Supplementary Fig. S37b). The ethanol productivity increased with progressively higher Ru content, following a slight decrease over 3.0% loading, which resulted from a decline of Ruδ+-O sites on the Ru nanoparticles (Supplementary Fig. S15). This result revealed the Ruδ+-O sites dominantly acted as the C–C coupling center. Interestingly, the ethanol productivity over 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 (18.1 μmol/g/h) improved ~12.3% compared with that of single 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 (16.1 μmol/g). The enhanced activity was attributed to extra thermal energy provided from a secondary irradiation by silica core (Supplementary Fig. S39), which stabilized more excited hot electrons and boosted endothermic C-C coupling step. Furthermore, sufficient dispersion of individual RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystals improved more interaction between active sites and CO2. To further improve the productivity of ethanol by enhancing mass transfer and driving force for product direction6, a series of pressurized experiments were conducted using single 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 and 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 catalysts under similar condition otherwise varied CO2 pressure. As shown in Fig. 5a, the ethanol productivity of both 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 and 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 catalysts finally improved up to 28.3 and 31.6 μmol/g/h, respectively, with over 90% selectivity. The photocatalytic performance of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 and 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 catalysts under visible light was investigated at maximum pressure of CO2 as well. The corresponding ethanol productivity was 14.2 μmol/g/h (86.9% Sel.) and 16.4 μmol/g/h (85.9% Sel.), respectively (Fig. 5b). A peer performance summary of photocatalytic CO2RR to C2 products was discussed in Supplementary Table S5. It is known that *CO is a key intermediate in the CO2RR to C2 products. In particular, the formation of *COCO* or *COCHO* species through C-C coupling of dual *CO or *CO with *CHO further promoted the formation of C2 products8,34,35. Therefore, we tried to aerate extra high-purity CO gas into the reaction system at a similar condition, aiming to enhance the adsorption of CO species onto the surfaces and boost the formation of *CO species directly. As a result, from Fig. 5c, the ethanol productivity was remarkably improved at a CO2 + CO combination compared with single CO2 at the same pressure. This result unveiled that the *CO is the key precursor of the C2 dimer during the C-C coupling process. A series of control and isotopic trace experiments further confirmed the photocatalytic CO2 conversion into ethanol (Supplementary Figs. S40, 41). The recycle experiment revealed the 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 could remain a well-stable activity for photocatalytic CO2RR (Supplementary Fig. S42). Moreover, 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 could keep a good crystal and electronic structure during the course of the reaction (Supplementary Figs. S43–S45). Besides, the interior anchored Ru atoms still remained a homogeneously atomic state without serious aggregation after reaction (Supplementary Fig. S46). The relevant band structure worked for the photocatalytic CO2RR was illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S47.

a Photocatalytic CO2RR performance and related ethanol selectivity under full-spectrum illumination for 3 h at varied pressure of CO2 (PCO2 = 1, 2, 4, and 6 bar) over 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 (top) and 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 (bottom); b Photocatalytic CO2RR performance and related ethanol selectivity under visible light (λ > 420 nm) for 3 h at CO2 = 6 bar over 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3 (top) and 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 (bottom); c Ethanol productivity of CO as intermediate exploration in CO2 photoreduction process under full-spectrum illumination for 3 h at different pressure of CO2 and CO combination over 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2.

In situ dynamic reconstruction of Ruδ+-O/Ru0-O sites analysis

From the above discussion, the unsaturated coordination Ruδ+-O sites in RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystal played a decisive role in photocatalytic CO2RR. To monitor the dynamic change of Ruδ+-O sites during the CO2RR process, in situ XPS spectra were carried out over 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 under initial dark, time-resolved illumination, and following a “light-off” again. As illustrated in Ru 3 d spectra (Fig. 6a), the Ru0/Ruδ+ 3d5/2 species showed a remarkable dynamic change along with illumination continuation. Specifically, the peaks of both Ru0 3d5/2 and Ruδ+ 3d5/2 species synchronously shifted to a lower energy range over the first 30 min, followed by a sluggish shift, and then a slightly additional shift to lower energy after 45 min. Furthermore, after removed light source, the peaks of Ru0/Ruδ+ 3d5/2 slightly shifted to a higher-energy range as well as Ru0/Ruδ+ 3d3/2, which suggests the dynamic transformation of Ru0/Ruδ+ 3d5/2 would recover to a thermodynamics equilibrium tendency in the absence of light excitation. However, it was worth noting that the equilibrium would undergo a sluggish process, and an ideal recovery to the initial state would be hard to observe immediately. This potential reducibility of Ru species could be confirmed by H2-TPR spectra (Supplementary Fig. S48). On the contrary, the oxides peak in O 1 s spectra presented an opposite shift trend along with the Ru 3 d5/2 peak shift (Fig. 6b). Interestingly, because of the stronger electron attraction of Ruδ+ at Ru-(O)-In site as above discussion, a fraction of electrons from In atoms would contribute to Ru0 species formation during illumination (slight higher-energy shift of In 3d in Supplementary Fig. S49), confirming that no obvious In0 species would be observed. The above results unveiled that unsaturated coordination of Ruδ+ exhibited an intimate electron transfer interaction with neighboring O and In.

In situ XPS spectra of high-resolution a C 1 s + Ru 3 d and b O 1 s of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 catalyst under dark and illumination (full-spectrum light, 300 W Xe lamp) at time scale, c corresponding dynamic change of proportion of Ru0 3 d5/2 (yellow) and Ruδ+ 3 d5/2 (purple) in RuOx peaks in Ru 3d XPS spectra, and d relevant plot for the ratio of Ru0 3d5/2 peak to Ruδ+ 3d5/2 in RuOx peak proportion (IR0/IRuδ+) in Ru 3d XPS spectra, ratio of oxides peak to Si-O peak proportion (IOxides/ISi-O) in O 1 s XPS spectra, and ratio of O-C = O peak to C-C peak proportion (IO-C=O/IC-C) in C 1 s XPS spectra; e In situ Raman spectra of B2g (in-plane Ru-O mode) of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 (i) and In2O3 (ii) under dark and illumination (full-spectrum) at time scale at a range of 500–1000 cm−1, and f corresponding time-resolved relative intensity change of B2g mode; g schematic illustration of dynamic Ru0-O/Ruδ+-O sites reconstruction during photocatalytic CO2 reduction process (P represents product, I represents intermediates).

To further validate the above hypothesis, the dynamic reconstruction process of Ruδ+-O/Ru0-O will be investigated by quantifying the changes in proportions of characteristic peaks in Ru 3 d, C 1 s, and O 1 s spectra over time. As shown in Fig. 6c, the proportion of Ru0 and Ruδ+ in Ru 3 d spectra exhibited a complementary trend. Moreover, the dynamic change in ratio of IRu0 to IRuδ+ showed a similar wave-like trend (Fig. 6d), as well as did in ratio of IOxides to ISi-O (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. S50). This result revealed the metallic Ru0 (3d5/2) species were produced from Ruδ+ (3d5/2) reduction through electron transfer from Oxides species of O and In during illumination. And aforementioned thermodynamics equilibrium was further affirmed by dynamic changes in the proportions among different chemical species after “off” light (Fig. 6c, d and Supplementary Fig. S50). In addition, the above trend unveiled that the kinetic rate of electrons filling into Ruδ+ orbital to form metallic Ru0 is much faster than the electron consumption rate of Ru0 for CO2 and intermediates activation. This resulted in more Ru0(-O) species formation (ratio of IRu0 to IRuδ+ >1) (S-I in Fig. 6d) with excess electrons accumulating around Ru-O sites. Subsequently, as more CO2 molecule orbitals hybridized with Ru0(-O) orbitals, the abundant electrons in Ru0-O sites were consumed, resulting in Ru0(-O) oxidization to Ruδ+(-O). At this stage, the kinetic rate of electrons refilling into Ruδ+(-O) to form Ru0(-O) could not keep up with the consumption rate of Ruδ+(-O), causing the ratio of IRu0 to IRuδ+ back to ~1:1 (S-II in Fig. 6d). This is because Ruδ+-O served as the active sites for C-C coupling process, and other intermediates undergo a slow kinetic protonation rate36, as a result, many Ruδ+-O sites would not be released timely and not further be reduced to Ru0(-O) species by nearby electrons, causing a significant accumulation of electrons around these sites again. Once these electrons refilled into the Ruδ+(-O) orbital after releasing product and intermediates, more Ru0(-O) species were newly formed (ratio of IRu0 to IRuδ+ >1) (S-III in Fig. 6d). Interestingly, this dynamic transformation between Ru0(-O) and Ruδ+(-O) pairs could be indirectly confirmed by dynamic changes of in-plane Ru-O (B2g) mode in in situ Raman spectra (Fig. 6e, f). The time-resolved fluctuations of B2g intensity suggests a dynamic regeneration of Ruδ+-O and Ru0-O species. Considering such intimate dependence on active Ruδ+-O/Ru0-O pairs during photocatalytic CO2RR, the ratio of IO-C=O and IC-C initially decreased at S-I stage, subsequently plateaued at S-II stage due to a deficiency of Ru0-O species, and then continuously declined as more Ru0-O species were newly formed at S-III stage (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. S51). To sum up, above results verified an intimately dynamic reconstruction between Ruδ+-O and Ru0-O species during photocatalytic CO2 activation, intermediates regulating, and even C-C coupling process.

Taken together, dynamic reconstruction of Ruδ+-O and Ru0-O pairs was schematically illustrated in Fig. 6g. A majority of electrons from O transfer to Ruδ+ after absorbing photons’ energy, gradually reducing it to the metallic state of Ru0(-O) (opening Ru-O bond). Later, the electrons in metallic Ru0(-O) species further interact with the absorbed CO2, and then Ru0(-O) returned to Ruδ+(-O), resulting in CO2 activation and intermediates regulating. The associated Ruδ+(-O) species further worked for the following C-C coupling steps. At last, the Ruδ+ re-bonded with O by releasing products (close Ru-O bond). It is worth noting that the above discussion merely demonstrated a dynamic shuttle process of Ru0-O/Ruδ+-O pairs during photocatalytic CO2RR. That did not mean that the whole photocatalysis process would take 45 min. Because the electrons excitation and transfer among these species are extremely rapid37, while, the reduction process of oxides species for intermediates activation and protonation would undergo a slow kinetics, resulting in electrons accumulating around the active sites18,36,38.

This alternant redox between Ruδ+ and Ru0 was also confirmed by cyclic voltammetry (CV). From Supplementary Fig. S52, an obvious broad peak of Ru0 (pink area) derived from Ruδ+ could be observed towards the negative scanning under both dark and illumination without CO2, as well as Ru0 oxidizing to Ruδ+ (cyan area) towards the positive scanning. Moreover, a new reduction peak came from CO2 activation ahead of Ruδ+→Ru0 peak within the negative scanning range in CO2-saturated electrolyte. Due to the Ruδ+-O/Ru0-O pairs sites in RuxIn2-xO3 nanocrystal, an obvious peak of CO2 activation was observed in the Bode phase plot (Supplementary Fig. S52d) compared with pure In2O3.

Photocatalytic reaction pathway

CO2 photoreduction to ethanol is a multiple-step process with various activations and coupling of intermediates. To understand the interaction of intermediates on the catalyst surface, in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier-transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) was carried out under simulated photocatalytic CO2RR conditions over a time scale. Overall, due to the active Ru-O site existence, the 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 showed enhanced adsorption for CO2 (Supplementary Fig. S53). Moreover, the DRIFTS spectra of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 after illumination demonstrated more abundant characteristic fingerprints compared to pure In2O3 (Fig. 7a, b). The bands at 1507 and 1374 cm−1 were assigned to the asymmetric and symmetric OCO stretching modes of monodentate carbonates (m-CO32−) respectively, while the OCO stretching modes of bidentate carbonates (b-CO32−) appeared at 1541 and 1338 cm−1 22,23. And the evidence of bands at 1222, 1433, and 1622 cm−1 indicated the bicarbonate (HCO3−) species formation23,39. Moreover, the stretching modes of H2O providing H source were detected at 1650 cm−1 and a range of 3580 to 3760 cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. S54), corresponding to the -OH group22,40. The appearance of broad bands centered at 2968 and 2738 cm−1 were respectively linked to the H-C and OCO stretching modes of formate species (*OCHO) as well as at 1472 cm−1 23,41,42, proving the formation of formic acid precursor. As a precursor of *CO, the relevant stretching mode of *COOH could be observed at 1258, 1561, and 1716 cm−1 43,44. Most importantly, much remarkable stretching modes of *CO-Ruδ+ were detected at 2090 and 2047 cm−1, corresponding to the linear *CO species in low-frequency and high-frequency range, respectively, as well as bridged *CO at 1945 and 1843 cm−1 9,34,45. Due to the high coverage of surface-absorbed *CO species at the Ruδ+-O sites, it provided a high probability for the formation of *COCO/*COCHO dimer and *CHO precursor of *COCHO. The high coverage of *CO at the Ruδ+-O sites and further hydrogenation to be *CHO were also proven by the direct activation of CO gas (Supplementary Fig. S55). The related *CHO and *COCHO stretching modes were observed at 1748 cm−1 and 1574 cm−1 as well, respectively34,40,46,47,48. The efficient activation for CO resulted from a strong interaction of the atomically dispersed Ru sites with CO by molecular orbital hybridization (Supplementary Figs. S56 and 57). Because of abundant monomer and dimer formation upon active sites, relevant stretching modes of ethanol product44 were also observed in Supplementary Fig. S54.

In situ DRIFTS spectra of a 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 and b In2O3 catalysts at CO2 + H2O(g) atmosphere under dark and time-resolved illumination for 105 min (with interval of 15 min); c corresponding time-resolved dynamic absorbance profile of *COlinear at 2047 cm−1, *CObridged at 1843 cm−1, *CHO at 1748 cm−1 and *COCHO species in In situ DRIFTS spectra over 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2; d In situ Raman spectra of 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 (i) and In2O3 (ii) catalysts at CO2 + H2O(g) atmosphere under dark and time-resolved illumination for 105 min (with interval of 15 min); e free energy diagram of CO2RR to ethanol by *COOH pathway on the (222) surface of Ru SAs sites of RuxIn2-xO3 and In2O3 (insert: illustration of energy barrier of *CO-*CO, *CO-*CHO and *CHO-*CHO coupling); f hypothesized mechanism illustration of photocatalytic CO2RR towards ethanol production on the surface of Ru SAs sites.

To verify the hypothesized relationship between intermediates and dynamic reconstruction of Ruδ+-O/Ru0-O pairs in the in situ XPS section, the time-resolved dynamic absorbance of several key intermediates (*COlinear, *CObridged, *CHO and *COCHO) during photocatalytic CO2RR was collected in Fig. 7c. As abundant Ru0(-O) species were formed from Ruδ+(-O) by photoinduced electrons, consequently, metallic Ru0(-O) boosted the CO2 activation as well as efficient intermediates regulating by Ruδ+(-O) (Ru0→Ruδ+), all above species increased obviously at the first stage (S-I). Because of a low reduction kinetics of Ruδ+(-O), insufficient regeneration of Ru0(-O) hampered efficient activation of adequate *CO2 species, leading to a declined production rate of *CO and *CHO species at the second stage (S-II). However, *COCHO species kept a good increase as more Ruδ+-O species were generated and occupied. This result indicated that the metallic state Ru0(-O) was favorable for CO2 activation, while oxide state Ruδ+(-O) could boot intermediates regulating and C-C coupling, which is consistent with the case of Cu0-CuI pairs18,24. Subsequently, as more Ru0-O species were regenerated in the S-III stage, the formation rate of all C1 intermediates increased again, while the *COCHO species decreased due to the decline of Ruδ+-O species.

Above powerful adsorption of *CO species (including *COlinear at 2091 cm−1 and CObridged at 1845 cm−1)45 was also confirmed by in situ Raman spectra (Fig. 7d). Similar time-resolved dynamic evolution of *COlinear species was observed as well (Supplementary Fig. S58). Interestingly, this strong adsorption of *CO species would diminish after removing the light source (Fig. 7d and Supplementary Fig. S58), which suggests that the primary contribution to *CO species regulating comes from the Ru0(-O) species driven by illumination. To highlight the beauty of Ru incorporation in enhancing adsorption and achieving high coverage of *CO for C2 dimer formation, other metals (such as Co and Ni) were investigated in photocatalytic CO2RR (Supplementary Fig. S59).

Taking into consideration of both in situ DRIFTs and Raman spectra analysis, key intermediates’ dynamic evolution was in good agreement with the dynamic reconstruction of Ruδ+-O/Ru0-O pairs in in situ XPS results (Fig. 6c), further proving the dynamic reconstruction of Ruδ+(-O)/Ru0(-O) pairs played a paramount role in CO2 activation, intermediates regulating, and C-C coupling.

To further understand the pathway to C1 and C2 chemicals during photocatalytic CO2RR process, various possible mechanisms were studied using DFT calculations on (222) facet with Ru SAs exposure. The results displayed in Fig. 7e and Supplementary Tables S6 and S7 revealed that the Ru SAs site (0.15 eV) exhibited 0.06 eV lower free energy (∆G) of adsorbed *CO2 compared to In2O3 (0.21 eV) as well as *OCOH (Supplementary Fig. S60), which demonstrates a thermodynamically favorable CO2 activation and intermediates regulating by Ru SAs. As the key precursor of *CO, the Ru SAs site shows exothermic adsorption (-0.63 eV) for *COOH in contrast with pure In2O3 (1.04 eV). Because of the strong interaction between CO and the Ru SAs site, further reduction of *COOH to form *CO is favored with −0.22 eV (Supplementary Fig. S57). This results in favorable coverage of *CO and intermediates (e.g., *CHO) production, which further facilitates C2 dimer production. This is in line with the strengthened stretching modes of *CO and *CHO species in the DRIFTS spectra (Fig. 7a). To investigate the lowest free energy pathway for C-C coupling, three possible C-C coupled intermediates were investigated using DFT calculations, i.e., *CO-*CO, *CO-*CHO and *CHO-*CHO coupling. We found the ∆G of *CO-*CO (1.35 eV) and *CHO-*CHO (1.55 eV) is higher than that of *CO-*CHO (1.30 eV) (Supplementary Table S6), indicating that the *CHO precedence formation provides a favorable path for C-C coupling of *CO and *CHO intermediates. A peer summary of possible C-C couping mechanism during photocatalytic CO2RR was discussed in Supplementary Table S5. Due to C-C coupling step involving a high energy barrier during C2 dimer production, more energy from the solar in the RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 core-shell structure could be utilized to overcome this barrier. That was the reason why RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 photocatalyst showed enhanced ethanol productivity under illumination. Based on the above discussion, Supplementary Fig. S61 displayed the full mechanistic study for the reduction of CO2 to ethanol over Ru SAs system.

Discussion

In this work, a series of active RuxIn2-xO3 photocatalysts with atomically dispersed Ru atoms were synthesized. Diverse techniques unveiled that unsaturated coordination Ruδ+-O sites played a crucial role in the photocatalytic CO2RR process. The RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 core-shell composites showed a higher reaction rate and selectivity for photothermal catalytic CO2RR into ethanol compared to the single RuxIn2-xO3. In situ XPS, DRIFTS, and Raman revealed that the metallic state of Ru0(-O) showed thermodynamically favorable activation of CO2, resulting in high coverage and strong interaction of *CO species on the Ru SAs site, while the oxide state of Ruδ+(-O) boosted intermediates regulating and asymmetric C-C coupling process. The intimately dynamic reconstruction of Ruδ+(-O)/Ru0(-O) pairs jointly completed the multi-step C2 chemical production from CO2. The DFT calculations further confirmed the *COCHO intermediate was the key dimer for ethanol production, and it would be formed through a precedence ladder of *CHO coupling with *CO instead of dual *CO or dual *CHO. This work provides a comprehensive insight into the dynamic construction of active sites towards intermediates regulating during the CO2RR process at the atomic level.

Methods

Synthesis of materials

Synthesis of SiO2

The silica nanosphere was synthesized by sol-gel method. In brief, firstly, a volume of 81 mL absolute alcohol was mixed with 24 mL NH3·H2O with stirring. And then, a volume of 4.2 mL TEOS solution was added into the above solution drop by drop, and stirring for 1 h to get white suspension. Finally, the prepared suspension was filtered several times, washed with deionized water, and dried in a vacuum oven overnight. The prepared white silica nanosphere was further annealed at 300 °C for 2 h to remove the possible impurity.

Synthesis of photocatalysts

A series of RuxIn2-xO3 photocatalysts were prepared through a simple solvothermal method. Typically, 0.6 g of In(NO3)3·xH2O was dissolved in a volume of 34 mL anhydrous DMF solution with vigorous stirring for 1 h. And then, different masses of RuCl3·xH2O (3.0 mg, 6.0 mg, 18.5 mg, 31.5 mg) were added into the above solution for another 1 h stirring and 30 min ultrasonic treatment to synthesize a series of different Ru single atoms loading catalysts (RuxIn2-xO3, where x means weight proportion of Ru, x = 0%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 3.0%, and 5.0%). After that, the solution was transferred into the Teflon-lined stainless autoclave and heated at 150 °C for 24 h. After cooling down to room temperature, the catalyst samples were collected by filtration and washed with absolute alcohol and warm deionized water several times and then dried in a vacuum overnight. Finally, the dried catalyst samples were further annealed at 250 °C for 1 h with argon flow of 40 sccm, aiming to remove possible impurity. Other metals modification is similar as above synthesis procedure otherwise different metal precursor (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O and Co(NO3)2·6H2O). The pure In2O3 (x = 0%) catalyst was synthesized followed by the above procedure without any RuCl3·xH2O adding.

The RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 composite catalyst was synthesized followed by the above procedure. After got the homogeneous mixture of In3+ and Ru3+ solution, 90 mg SiO2 nanosphere was added into above solution for 30 min stirring and another 30 min ultrasonic treatment, respectively. And then, the mixture solution would undergo the solvothermal synthesis method and annealed treatment as above.

Characterization

The crystallographic phases were analyzed using a D8 Advanced XRD (USA) with Cu Kα X-ray radiation (λ = 1.54056 Å). The morphology was measured by a field-emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi S-4800, Japan) and transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEOL JEM-2100F, Japan). High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images were performed on a JEOL JEM-2100F field-emission electron microscope working at 200 kV. The ex-situ Raman spectra were obtained using a DXR3xi confocal Raman spectrometer (USA) with a 532 nm excitation laser. EPR spectra were recorded on an EPR spectrometer (Bruker EMX plus, USA). Surface morphology and potential were measured by the Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM, SPA-400, Japan), the surface potential was mapped by sample routing at zero tip bias, and dark and illumination conditions were maintained for 5 min before performing to achieve the equilibrium of carriers transport. XPS measurements of specific chemical states and elemental components were conducted using an ESCALAB 250Xi spectrometer system (Thermo Fisher, USA) with a monochromatic Al Kα source. Binding energies were calibrated to the C 1 s peak at 284.8 eV. Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherm was tested by Micromeritics (ASAP 2460, USA), surface area, and porosity analyzer at 77 K. The specific surface areas were calculated by the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller method. UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra were recorded by SHIMADZU UV–vis spectrophotometer in the range of 300~900 nm. Time-resolved photoluminescence spectrum was measured on a transient fluorescence spectrometer (FLS-1000, Edinburgh) with an excitation and emission wavelength at 360 nm and 450 nm, respectively. The content of Ru in RuxIn2-xO3 catalysts was measured by an ICP-MS instrument (Agilent 7700 series, USA).

CO2/NH3/H2 temperature-programmed desorption

CO2 and NH3 temperature-programmed desorption (CO2/NH3-TPD) measurements were performed using an AutoChem II 2920 chemical gas adsorption analyzer (USA). Prior to analysis, the catalyst was pretreated with helium (He) at 300 °C for 1 h (ramp: 10 °C/min) to remove adsorbed CO2, followed by cooling to 50 °C. For CO2-TPD, a 10% CO2/He gas mixture (or NH3/He for NH3-TPD) was introduced at 30–50 mL/min for 1 h to ensure saturation. The system was then purged with pure He and heated to 600 °C (ramp: 10 °C/min), with desorbed gases detected using a TCD-equipped GC.

The H2-TPR measurement is similar to the CO2/NH3-TPD measurements; otherwise, H2 flow replacement.

XAFS measurement

The X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) spectra were measured with beamline BL08U1A in Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF 1W1B, Shanghai, China) by using Si (111) double-crystal monochromator, in which storage rings of BSRF were operated at 2.5 GeV with a maximum current of 250 mA. The data collection was performed in transmission mode using an ionization chamber for metal foil and metal oxides as references, and in fluorescence excitation mode using a Lytle detector for SACs, respectively. All spectra were collected under ambient conditions.

In situ XPS measurement

In situ XPS spectra of RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 catalyst were measured by an X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, ESCALAB 250Xi, USA, Alpha equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα source), and all the raw data were calibrated by C 1 s at 284.8 eV. To investigate the dynamic change of Ru 3 d, O 1 s, and C 1 s, this experiment would be conducted under dark and time-resolved illumination (300 W Xe lamp: full spectrum) with CO2/H2 atmosphere. Typically, prior to performing the test, the catalyst would be pretreated with He gas flow at 100 °C for 1 h to remove the impurity absorbed on the surface, and then changed the atmosphere to be CO2/H2 till at 100 °C for another 1 h to achieve saturated adsorption. After that, firstly, the XPS spectra of different elements would be recorded in the dark at room temperature. And then, time-resolved XPS spectra would be recorded under illumination for 60 min with an interval of 15 min. At last, the spectra after removing the light source were recorded immediately again.

In situ DRIFTS measurement

The in situ DRIFT spectra were recorded by a Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (Thermo Fisher: Nicolet iS50, USA) with PerkinElmer Frontier in the range of 4000~600 cm−1, aiming to investigate the key intermediates during CO2 photoreduction process over pure In2O3 and RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 catalysts under dark and time-resolved illumination (300 W Xe lamp: full spectrum) reaction condition. Typically, before carrying out the measurement, the catalyst was pretreated with He gas flow at 100 °C for 1 h to remove absorbed impurities. Subsequently, the background spectrum was recorded with a resolution of 4 cm−1 at 100 °C in He flow. And then, a gas mixture of CO2/H2O(gas)/He with a flow rate of 40 sccm (30 sccm of CO2/H2O (g), 10 sccm He, respectively) was aerated into the reaction system for 40 min at 100 °C under dark. First, the in situ DRIFT spectrum of catalyst was recorded under dark, and then, the time-resolved DRIFT spectra was recorded under illumination for 105 min with an interval of 15 min in a resolution of 4 cm−1. The in situ DRIFT spectra of CO adsorption were measured following the CO2 measurement procedure.

In situ Raman measurement

The in situ Raman spectra were measured by a microscope confocal Raman spectrometer (Lab RAM HR Evolution Raman microscope, France) with an excitation of 532 nm laser. Simulated gas-liquid-solid phases condition as photocatalytic CO2RR was carried out. Prior to test, the catalysts samples were pretreated by He gas flow at 80 °C for 1 h to remove potential absorbed impurity. Keep at this condition, the background was recorded at a step rate of 4 cm−1. Next, the high-purity CO2 was aerated into system for 40 min to be saturated under dark. The spectra after absorbed CO2 would be record under dark first. And then, time-resolved Raman spectra would be recorded under illumination (300 W Xe lamp: full spectrum) for 105 min with an interval of 15 min. At last, the spectra after removed light source for 15 min later were recorded again.

Ultrafast transient fs-TA spectroscopy measurement

The femtosecond transient absorption (fs-TA) spectra were measured using optical pump-probe spectroscopy with Femto-TA100 spectrometer (Time-Tech Spectra). The fs radiation source was an 800 nm output pulse from a regenerative amplified Ti: sapphire laser system, delivering 35 fs pulse at 6 mJ and 1 KHz. The 800 nm pump pulse was split into two beams via a 50% beam splitter. The transmitted beam was directed to a TOPAS Optical Parametric Amplifier to generate tunable pump pulses (250 nm to 2.5 μm), while 10% of the reflected beam was attenuated by a neutral-density filter and focused through a 2 mm CaF2 window to generate a white light continuum (340–800 nm) for the probe. This probe beam was focused onto the catalysts using an aluminum parabolic reflector, collimated after interaction, and passed into a fiber-coupled spectrometer with CMOS sensors operating at 1 KHz. Pump pulse intensity was controlled by a variable neutral-density filter wheel, and the pump-probe temporal delay was precisely regulated by a motorized delay stage. A 500 Hz mechanical chopper modulated the pump pulse, and changes in absorbance were calculated by comparing the probe pulses with and without the pump pulse. All measurements were carried out at ambient condition, and the catalysts were excited by a 400 nm pump pulse. The induced absorption change (∆A), as a function of both wavelength and temporal profile, was recorded to analyze the dynamic of the exited states.

Photocatalytic performance evaluation

CO2 Photoreduction experiment was carried out in a 70 mL high-pressure reactor with a quartz window in the center area on the top (Supplementary Fig. S62). The light source was provided by a 300 W Xe lamp (Excelitas Tech., United States, Light intensity: 1 W/cm2). The lamp was placed on the top of the high-pressure reactor with a distance of 15 cm between them. In a typical experimental procedure, 20 mg catalyst was dispersed into 10 mL deionized H2O. The reactor containing catalyst suspension was treated under ultrasound for 10 min. Prior to sealing, high-purity CO2 (99.999%, Air liquid) was aerated into suspension for 40 min under stirring. And then, the reactor was sealed and high-purity CO2 was purged into the reactor up to expected reaction pressure (1 bar, 2 bar, 4 bar, and 6 bar) and evacuated 5 times by turns to remove air, at last maintaining the high pressure for 20 min to stabilize. Subsequently, the reactor was conducted under illumination for 3 h. Before analyzing the products, the reactor was cooled down at a low temperature (4 °C). The gas products were quantified by a Gas Chromatograph (GC, Clarus 590, PerkinElmer) equipped with a TCD (5 A molecular sieve and a Carboxen 1000 packed column) and an FID detector. And the liquid products were quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Thermo Fisher ICS-6000 system) with a refractive index detector and an Aminex HPX-87 H column (300 × 7.8 mm, Bio-Rad). The sulfuric acid solution (5 mM) was used as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The liquid products were detected by the 1H-NMR (Bruker Advance III 400 MHz spectrometer with a BBFO probe, USA) and GC-MS (Agilent 5973, USA). In the quantification of gas products, it was noted that traces C2H4 and C2H6 were ignored. Because of the manual injection into the GC, the O2 in the reactor was just qualified and not quantified due to the inevitable exposure to air when the gas products were taken by the syringe. The ethanol selectivity was calculated by the equation as follows:

*CO as key intermediate exploration experiment was similarly followed as CO2 photoreduction procedure. Differently, after sealing the reactor, high-purity CO2 was purged into the reactor and kept at 2 bar pressure, following extra high-purity CO compensation (99.99%, Air liquid) was added up to the expected pressure (for example total pressure (4 bar) = CO2(2 bar) + CO(2 bar)). All of the error bars were calculated based on the duplicated experiments.

A 3-round recycle experiment was performed over 3.0%RuxIn2-xO3/SiO2 catalyst under full -spectrum light illumination for 3 h at a CO2 pressure of 6 bar condition.

The isotopic tracing experiment was carried out by using 13CO2 (99% atom% 13C, Sigma) as the carbon source. The experimental procedure and condition were followed as CO2 photoreduction reaction by replacing normal CO2. The mass spectra of ethanol were measured by GC-MS (Agilent 5975 GC-MS, USA, source type: electron ionization (EI)).

Computational details

DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) with spin polarization49, in conjunction with the Atomic Simulation Environment50, which was used to set up the VASP calculations. The generalized gradient approximation exchange-correlation functional parametrized by Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof for the electronic interactions51. The cutoff energy for the plane-wave-basis set was 500 eV, and the projector-augmented wave method for the core electrons was used52. The convergence criterion for the electronic self-consistent iteration was set at 10−6 eV. During the relaxation, we assumed the relaxation was achieved when the atomic forces were lower than 0.05 eV/Å. We used a Monkhorst−Pack grid with dimensions of 4 × 4 × 1 for sampling the first Brillouin zones53. The DOS calculations were done using a 12 × 12 × 12 k-points grid, and the tetrahedron method with Blöchl corrections54.

Because of the same miller indices of (111) and (222) facets, the In2O3 surface was modeled using 2 × 2 supercells of the (111) facets with four layers, for which only the bottom two layers were frozen, while the rest of the system was allowed to relax. The In2O3(111) is doped with Ru by substituting one In atom with Ru, which corresponds to a 3% Ru doping concentration in Ru-doped In2O3 surface. To ensure that the interactions between neighboring periodic images are negligible, a vacuum region along the z-direction has been added so that the distance between the two nearest surface atoms in neighboring images is at least 18 Å. We employed the DFT-D3 Grimme method for long-range dispersion interaction correction55.

The computational hydrogen electrode model proposed by Nørskov et al. was used to calculate the free energies of CO2 reduction intermediates, based on which the free energy of an adsorbed species is defined as: \(\Delta {G}_{{ads}}=\Delta {E}_{{ads}}+\Delta {E}_{{ZPE}}-T\Delta {S}_{{ads}}+\int {C}_{p}{dT}\) (2), where \(\Delta {E}_{{ads}}\) is the electronic adsorption energy, \(\Delta {E}_{{ZPE}}\) and \(T\Delta {S}_{{ads}}\) represent zero-point energy and entropy (difference between adsorbed and gaseous species), respectively, \(\int {C}_{p}{dT}\) is the enthalpy correction and T is at room temperature56.

Bader charge population analysis was used to analyze the charge population and electron transfer57. The Bader charge density difference was analyzed with the VESTA program58.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Information file. All raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Ou, H. et al. Atomically dispersed Au-assisted C–C coupling on red phosphorus for CO2 photoreduction to C2H6. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 22075–22082 (2022).

Rodríguez-Jiménez, S. et al. Self-assembled liposomes enhance electron transfer for efficient photocatalytic CO2 reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 9399–9412 (2022).

Xin, Z.-K. et al. Rational design of dot-on-rod nano-heterostructure for photocatalytic CO2 reduction: pivotal role of hole transfer and utilization. Adv. Mater. 34, 2106662 (2022).

Gong, S. et al. Selective CO2 photoreduction to acetate at asymmetric ternary bridging sites. ACS Nano 17, 4922–4932 (2023).

Das, R., Das, K., Ray, B., Vinod, C. P. & Peter, S. C. Green transformation of CO2 to ethanol using water and sunlight by the combined effect of naturally abundant red phosphorus and Bi2MoO6. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 1967–1976 (2022).

Shi, H. et al. Atomically dispersed indium-copper dual-metal active sites promoting C-C coupling for CO2 photoreduction to ethanol. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202208904 (2022).

Chakraborty, S. et al. Wurtzite CuGaS2 with an in-situ-formed CuO layer photocatalyzes CO2 conversion to ethylene with high selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202216613 (2023).

Jin, J. et al. Constrained C2 adsorbate orientation enables CO-to-acetate electroreduction. Nature 617, 724–729 (2023).

Chou, T.-C. et al. Controlling the oxidation state of the Cu electrode and reaction Intermediates for electrochemical CO2 reduction to ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 2857–2867 (2020).

Santatiwongchai, J., Faungnawakij, K. & Hirunsit, P. Comprehensive mechanism of CO2 electroreduction toward ethylene and ethanol: the solvent effect from explicit water–Cu(100) interface models. ACS Catal. 11, 9688–9701 (2021).

Han, X. et al. Intensifying heat using MOF-isolated graphene for solar-driven seawater desalination at 98% solar-to-thermal efficiency. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2008904 (2021).

Liu, B.-T. et al. Construction of function-oriented core–shell nanostructures in hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks for near-Infrared-responsive bacterial inhibition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 25701–25707 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Selective light absorber-assisted single nickel atom catalysts for ambient sunlight-driven CO2 methanation. Nat. Commun. 10, 2359 (2019).

Cai, M. et al. Greenhouse-inspired supra-photothermal CO2 catalysis. Nat. Energy 6, 807–814 (2021).

Feng, K. et al. Cobalt Plasmonic superstructures enable almost 100% broadband photon efficient CO2 photocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 32, 2000014 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. Grave-to-cradle upcycling of Ni from electroplating wastewater to photothermal CO2 catalysis. Nat. Commun. 13, 5305 (2022).

Wang, J., Tan, H.-Y., Zhu, Y., Chu, H. & Chen, H. M. Linking the dynamic chemical state of catalysts with the product profile of electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 17254–17267 (2021).

Chang, C.-J. et al. Lewis acidic support boosts C-C coupling in the pulsed electrochemical CO2 reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 6953–6965 (2023).

Lin, S.-C. et al. Operando time-resolved X-ray absorption spectroscopy reveals the chemical nature enabling highly selective CO2 reduction. Nat. Commun. 11, 3525 (2020).

Yang, P.-P. et al. Protecting copper oxidation state via intermediate confinement for selective CO2 electroreduction to C2+ fuels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 6400–6408 (2020).

Lan, J. et al. Efficient electrosynthesis of formamide from carbon monoxide and nitrite on a Ru-dispersed Cu nanocluster catalyst. Nat. Commun. 14, 2870 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Ru-based catalysts for efficient CO2 methanation: synergistic catalysis between oxygen vacancies and basic sites. Nano Res. 16, 12153–12164 (2023).

Yan, T. et al. Bismuth atom tailoring of indium oxide surface frustrated Lewis pairs boosts heterogeneous CO2 photocatalytic hydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 11, 6095 (2020).

Chen, Z., Liu, Z. & Xu, X. Dynamic evolution of the active center driven by hemilabile coordination in Cu/CeO2 single-atom catalyst. Nat. Commun. 14, 2512 (2023).

Xing, G. et al. Reconstruction of highly dense Cu-N4 active sites in electrocatalytic oxygen reduction characterized by operando synchrotron radiation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202211098 (2022).

Liu, D. et al. Large-scale synthesis of hexagonal corundum-type In2O3 by ball milling with enhanced lithium storage capabilities. J. Mater. Chem. A. 1, 5274–5278 (2013).

Ryan, J. V. et al. Electronic connection to the interior of a mesoporous insulator with nanowires of crystalline RuO2. Nature 406, 169–172 (2000).

Tao, H. et al. Nitrogen fixation by Ru single-atom electrocatalytic reduction. Chem 5, 204–214 (2019).

Yao, Y. et al. Single atom Ru monolithic electrode for efficient chlorine evolution and nitrate reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202208215 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Arming Ru with oxygen-vacancy-enriched RuO2 sub-nanometer skin activates superior bifunctionality for pH-universal overall water splitting. Adv. Mater. 35, 2206351 (2023).

Rahman, M. Z. & Mullins, C. B. Understanding charge transport in carbon nitride for enhanced photocatalytic solar fuel production. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 248–257 (2019).

Maity, P. et al. Cascade Electron Transfer induces slow hot carrier relaxation in CsPbBr3 asymmetric quantum wells. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 2602–2609 (2021).

Yao, Q. et al. Promoting photocatalytic H2 evolution through retarded charge trapping and recombination by continuously distributed defects in methylammonium lead iodide perovskite. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202308140 (2023).

Yao, K. et al. Mechanistic insights into OC–COH coupling in CO2 electroreduction on fragmented copper. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 14005–14011 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. CO electroreduction on single-atom copper. Sci. Adv. 9, eade3557 (2023).

Montoya, J. H., Peterson, A. A. & Nørskov, J. K. Insights into C-C coupling in CO2 electroreduction on opper electrodes. ChemCatChem 5, 737–742 (2013).

Chen, R. et al. Spatiotemporal imaging of charge transfer in photocatalyst particles. Nature 610, 296–301 (2022).

Zhao, S. et al. Steering carbon dioxide reduction toward C–C coupling using copper electrodes modified with porous molecular films. Nat. Commun. 14, 844 (2023).

Yu, Y.-Y., He, Y., Yan, P., Wang, S.-Y. & Dong, F. Boosted C–C coupling with Cu–Ag alloy sub-nanoclusters for CO2-to-C2H4 photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2307320120 (2023).

Xu, R. et al. Tandem photocatalysis of CO2 to C2H4 via a synergistic rhenium-(I) bipyridine/vopper-porphyrinic triazine framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 8261–8270 (2023).

Kattel, S., Yan, B., Yang, Y., Chen, J. G. & Liu, P. Optimizing binding energies of key intermediates for CO2 Hydrogenation to methanol over oxide-supported copper. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12440–12450 (2016).

Guo, W. et al. General synthesis and atomic arrangement identification of ordered Bi–Pd intermetallics with tunable electrocatalytic CO2 reduction selectivity. Nat. Commun. 15, 1573 (2024).

Deng, X. et al. Ultrafast electron transfer at the In2O3/Nb2O5 S-scheme interface for CO2 photoreduction. Nat. Commun. 15, 4807 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Coupling photocatalytic CO2 reduction and CH3OH oxidation for selective dimethoxymethane production. Nat. Commun. 15, 6047 (2024).

Chang, X. et al. Understanding the complementarities of surface-enhanced infrared and Raman spectroscopies in CO adsorption and electrochemical reduction. Nat. Commun. 13, 2656 (2022).

Ji, J. et al. Highly selective photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to ethane over Au-O-Ce sites at micro-interface. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 321, 122020 (2023).

Kim, Y. et al. Time-resolved observation of C–C coupling intermediates on Cu electrodes for selective electrochemical CO2 reduction. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 4301–4311 (2020).

Birdja, Y. Y. et al. Advances and challenges in understanding the electrocatalytic conversion of carbon dioxide to fuels. Nat. Energy 4, 732–745 (2019).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Hjorth Larsen, A. et al. The atomic simulation environment—a Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 273002 (2017).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Blöchl, P. E., Jepsen, O. & Andersen, O. K. Improved tetrahedron method for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 49, 16223–16233 (1994).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886–17892 (2004).

Henkelman, G., Arnaldsson, A. & Jónsson, H. A fast and robust algorithm for Bader decomposition of charge density. Comput. Mater. Sci. 36, 354–360 (2006).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA: a three-dimensional visualization system for electronic and structural analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 41, 653–658 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Canada First Research Excellent Funds (S.S., M.G.K., and J.H.) and China Scholarship Council scholarship (H.G.Z.). S.S. and A.G.Y. acknowledge the support from the Materials for Clean Fuels (MCF) Challenge R&D Program from the National Research Council of Canada. This research was enabled in part by the support provided by computational resources at Compute Canada (www.computecanada.ca).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. supervised the project and provided DFT analysis support. M.G.K. and J.H. conceptualized and supervised the project. H.G.Z. proposed the idea, designed and conducted experiments and characterization, analyzed data, and drafted the article. A.Y. conducted the DFT calculation and drafted computation details. Z.L. and H.Z. assisted EXAFS analysis and revised the manuscript. Y.X. contributed to the fs-TAs measurement and relevant analysis. X.C. and H.W. assisted synthesis and performance evaluation experiments. Z.K.L. assisted isotopic experiment and electrochemical properties test. All authors participated in the manuscript writing and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xinwen Guo, Tae Kyu Kim and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Yohannes, A., Zhao, H. et al. Photocatalytic asymmetric C-C coupling for CO2 reduction on dynamically reconstructed Ruδ+-O/Ru0-O sites. Nat Commun 16, 534 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55885-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55885-z