Abstract

Intensified host-guest electronic interplay within stable metal-organic cages (MOCs) presents great opportunities for applications in stimuli response and photocatalysis. Zr-MOCs represent a type of robust discrete hosts for such a design, but their host-guest chemistry in solution is hampered by the limited solubility. Here, by using pyridinium-derived cationic ligands with tetrakis(3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)borate (BArF−) as solubilizing counteranions, we report the preparation of soluble Zr-MOCs of different shapes (1-4) that are otherwise inaccessible through a conventional method. Enforced arrangement of the multiple electron-deficient pyridinium groups into one cage (1) leads to magnified positive electrostatic field and electron-accepting strength in favor of hosting electron-donating anions, including halides and tetraarylborates. The strong charge-transfer (CT) interactions activate guest-to-host photoinduced electron transfer (PET), leading to pronounced and regulable photochromisms. Both ground-state and radical structures of host and host-guest complexes have been unambiguously characterized by X-ray crystallography. The CT-enhanced PET also enables the use of 1 as an efficient photocatalyst for aerobic oxidation of tetraarylborates into biaryls and phenols. This work presents the solution assembly of soluble Zr-MOCs from cationic ligands with the assistance of solubilizing anions and highlights the great potential of harnessing host-guest CT for boosting PET-based functions and applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal-organic cages (MOCs)1,2,3, a class of discrete metallosupramolecular capsules, are assembled from organic ligands with either metal ions or metal clusters. Their well-defined cavities enable them to have wide applications ranging from molecular recognition4, separation5,6,7,8,9, stabilization of reactive species10, and catalysis11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Although MOCs can be used in solid state, akin to the use of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)20,21,22,23, it is the most appealing to make use of the molecular attribute of MOCs that distingushes them from MOFs. In particular, MOCs can behave or be processed as discrete hollow molecules in solution, which can afford unique host-guest chemistry and functions inaccessible by porous solids.

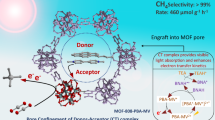

Photoinduced electron transfer (PET) plays a central role in biological photosynthesis and many artificial photoresponsive and photocatalytic processes24,25,26,27. How to achieve high-efficiency PET in artificial systems is a great challenge. Formation of ground-state charge-transfer (CT) complexes prior to PET, in particular with the use of cage hosts to intensify host-guest electronic communications, is expected to be an effective strategy, which is explored in this work. CT complexation is capable of increasing the host-guest affinity and prearranging the substrate in short contact with the host, overcoming the diffusion limitation on PET28,29,30,31. In particular, CT complexation gives rise to bathochromic and intense photoabsorption. Excitation through the CT absorption not only increases the range and efficiency of light harvesting but also provides a more direct and faster route for PET than excitation through cage absorption.

The pyridinium unit is known for the capability of PET as well as CT due to its electron-deficient attribute32. It has been used as the building unit of various artificial molecules, supermolecules, polymers, and MOFs to impart photoresponsive and photocatalytic properties33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. Gathering of multiple cationic pyridinium units in one coordination cage is envisioned to generate a superimposed positive field inside and around the cage and also cooperatively magnify the electron-accepting strength. The resultant hosts are thus promising to display charge-enhanced CT complexation towards electron-rich guests, activating the guests for efficient PET and leading to superior light-responsive and catalytic performances. It is thus highly desirable to prepare multipyridiniums-integrated MOCs with high solubility and stability, which remains rare.

The Zr-MOCs with Cp3Zr3O(OH)3 vertices (Cp = η5-C5H5) and multicarboxylic linkers, which exhibit high chemical stability due to the high Zr−O bond energy (766 kJ/mol), have witnessed rapid development since the first report in 2013 by the Yuan group43,44. They are usually synthesized through a conventional solvothermal approach to yield crystalline powders. The majority of Zr-MOCs have limited solubility resulting from the strong interactions between cationic Cp3Zr3O(OH)3 vertices and counterions (generally Cl−), and are primarily used as crystalline solids for multiphase applications, such as gas separation44,45,46 iodine capture47, and heterogeneous catalysis48,49. Nevertheless, a few Zr-MOCs have been investigated as hosts for anion binding in solution or processed in solution to prepare composite membranes50,51,52,53,54,55. Improvement of the solubility of Zr-MOCs can be achieved by functionalizing the linkers with amino, alkyl, or other solubilizing groups50,51,52. Another rare but innovative method involves the decoration of the Cp3Zr3O(OH)3 nodes by introducing pendant groups, such as n-butyl, benzyl, or trifluoromethylbenzyl, into the Cp rings53,54. A third solubilization strategy is postassembly ion exchange, which has been effective for various ionic MOCs including Zr-MOCs55,56.

In this work, we highlight the use of counteranions to facilitate synthesis of highly soluble Zr-MOCs from pyridinium-derived cationic ligands. Different from the previous postassembly anion-exchange method55, we introduce the solubilizing counteranion, tetrakis(3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)borate (BArF−), into the flexible pyridinium-based ligands to minimize cation-anion interactions during the self-assembly, thereby preventing the formation of insoluble intermediates. Following this approach, four Zr-MOCs ranging from helicates (1-3) to tetrahedron (4) were constructed homogeneously in solutions. The incorporation of multiple electron-deficient pyridinium groups imparts superior electron-accepting abilities to the MOCs, which thus are capable of hosting electron-donating anions, including tetraarylborates, through dominative CT interactions. The ground-state interactions facilitate guest-to-host PET, resulting in efficient and regulable photochromism. In particular, the photogenerated radical state of 1 can rapidly transfer electrons to O2 to generate O2•−, enabling the use of 1 as an effective photocatalyst for oxidation of tetraarylborate guests.

Results

Design, synthesis, and characterization

We first attempted to prepare the desired Zr-MOC using the conventional synthetic method for Zr cages44, i.e., reacting zirconocene dichloride (Cp2ZrCl2) with 1,1’-bis(4-carboxybenzyl)-4,4’-bipyridinium dichloride (L1-Cl, Supplementary Fig. 1). In spite of extensive efforts to screen synthetic conditions, including solvent mixtures, temperature, pH and reaction time, this method led to insoluble amorphous powder. Considering the strong Coulombic and hydrogen-bonding interactions afforded by the chloride ions and the high flexibility of the ligand due to the presence of methylene joints, we infer that the counteranion (Cl−) in high content influences the self-assembly process by irreversibly forming insoluble precipitates with the cationic intermediates of the metal-organic assembly.

In order to improve the reversibility and self-correction ability during the self-assembly, BArF− was chosen as the counteranions of the ionic ligand. The rather bulky and highly lipophilic anion is supposed to minimize cation-anion interactions and thus to enable the high solubilities of the assembly intermediates and the product. As shown in Fig. 1a, 1-BArF ({[Cp3Zr3(μ3-O)(μ2-OH)3]2(L1)3}(BArF)8) was assembled from a 1:2 ratio of L1-BArF and Cp2ZrCl2 in CH3OH/H2O at 65 °C for 12 h. The reaction gave a homogeneous solution and 1-BArF was precipitated by adding a large amount of water. The identity of the cage was confirmed by high-resolution electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry (HR-ESI-MS), which is consistent with a C2L3 [C = cluster Cp3Zr3(μ3-O)(μ2-OH)3, and L = Ligand] composition (Supplementary Fig. 22). The 1H NMR spectrum of 1-BArF presents only one set of ligand resonances, indicating the C3-symmetry of the cage (Fig. 1b). All proton signals of 1 were assigned by two-dimensional (2D) NMR experiments (Supplementary Figs. 20–21).

a Self-assembly of 1-BArF (C2L3, {[Cp3Zr3(μ3-O)(μ2-OH)3]2(L1)3}(BArF)8). b 1H NMR spectrum (CD3OD, 400 MHz, 298 K) of 1-BArF. c Structures of 2-BArF (C2L3, {[Cp3Zr3(μ3-O)(μ2-OH)3]2(L2)3}(BArF)8), 3-BArF (C2L3, {[(n-BuCp)3Zr3(μ3-O)(μ2-OH)3]2(L3)3}(BArF)8), and 4-BArF (C4L4, {[Cp3Zr3(μ3-O)(μ2-OH)3]4(L4)4}(BArF)16).

1-BArF is highly soluble in various solvents, such as methanol, acetonitrile, acetone, and DMSO (Supplementary Fig. 17). The counteranions can be easily exchanged to other anions to obtain 1-X complexes ({[Cp3Zr3(μ3-O)(μ2-OH)3]2(L1)3}X8) with X = Tf2N− (bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide), TfO− (trifluoromethanesulfonate), PF6−, Cl−, or NO3− (Supplementary Figs. 23–24). In particular, 1-NO3 is stable and highly soluble in water (Supplementary Fig. 23).

Vapor diffusion of Et2O into a MeOH solution of 1-BArF in the presence of SCN− produced crystals of 1-SCN suitable for single-crystal X-ray analysis. As shown in Fig. 2a, MOC 1 is a cage-like triple helicate with two trinuclear [Cp3Zr3(μ3-O)(μ2-OH)3] clusters connected by three viologen-based carboxylate linkers. The helicity arises from the gauche conformation of the linker, which is allowed by the two flexible methylene joints between viologen and benzoate moieties.

To prove the reliability of soluble Zr-MOC synthesis using solubilizing ionic ligands, we synthesized three additional Zr-MOCs of different shapes and sizes following similar procedures (Figs. 1c, 2–4). Cage 2 is isomeric to 1, with the difference being in the carboxylate position in the ligands (Supplementary Figs. 25–32). 2-BArF ({[Cp3Zr3(μ3-O)(μ2-OH)3]2(L2)3}(BArF)8) was found to partially dissociate into ligands and Zr-clusters in CD3OD, DMSO-d6, and CD3COCD3, while negligible dissociation occurred in CD3CN (Supplementary Fig. 32). The presence of additional anions, such as I− and TfO−, could also serve as templates to drive the conversion from the assembly components into the cage (Supplementary Figs. 33–34). The assembly of a thiazolo[5,4-d]thiazole-extended viologen ligand with dibutylzirconocene dichloride ((n-BuCp)2ZrCl2) led to an elongated C2L3 helicate (3-BArF, {[(n-BuCp)3Zr3(μ3-O)(μ2-OH)3]2(L3)3}(BArF)8) (Supplementary Figs. 35–41). We noted that the assembly using Cp2ZrCl2 showed significant dissociation in CD3OD, while the use of (n-BuCp)2ZrCl2 enabled the formation of 3 with negligible dissociation. This could be because the n-butyl groups decorating Cp3Zr3O(OH)3 vertices further increase the solubility and stability of the cage in organic solvents53. A face-capped C4L4 tetrahedral cage 4-BArF ({[Cp3Zr3(μ3-O)(μ2-OH)3]4(L4)4}(BArF)16) was also successfully assembled from a tripyridinium-tricarboxylate ligand and Cp2ZrCl2 (Supplementary Figs. 42–48). These cages (2-4) have been fully characterized by 1D and 2D NMR and HR-ESI-MS. Crystals of 3-SCN were obtained by vapor diffusion of chloroform into an ethanol solution of 3-BArF in the presence of SCN−. As shown in Fig. 2b, the diameter of helicate 3 is similar to that of 1, which are determined by three methylene groups. The heights are determined by the lengths of the bipyridinium units, and the distances between the two μ3-O atoms are 24.74 Å for 3 and 19.65 Å for 1.

Charge transfer-promoted anion binding

Considering the very weak binding ability of BArF− with the cages resulting from its bulky size, low charge density, and substituted trifluoromethyl groups57,58, we used 1-BArF as the host to investigate the guest binding properties of 1. 1H NMR titrations of 1-BArF with various anions (Cl−, Br−, I−, SCN−, TfO−, ReO4−, NO3−, ClO4−, PF6−, and Tf2N−, as tetrabutylammonium [TBA] salts) presented gradual shifts of resonance signals, in particular for viologen protons (H1 and H2 in Fig. 1a), indicating anion binding in fast exchange on the NMR timescale. Interestingly, the binding of the halide anions showed upfield shifts of H1 and downfield shifts of H2 (Supplementary Figs. 53–55), while other anions induced upfield shifts of both protons (Supplementary Figs. 56–62). Binding constants were determined using BindFit (Supplementary Table 1) http://supramolecular.org/. The 1:1 binding stoichiometry was obtained for all these anions with the following binding hierarchy: I− > Br− > Cl− > SCN−, TfO−, ReO4− > NO3−, ClO4− > PF6−, Tf2N−. The binding sequence for halides is not determined by Coulombic interactions or charge localization of halides but consistent with their electron-donor (ED) strength, suggesting the dominance of electron donor-acceptor CT interactions between halides and the viologen moieties of the cage. The strong CT binding of I− and Br− is evidenced by the visual color changes (from colorless to yellow) and the appearance of CT absorption in UV-Vis spectra upon addition of these anions into 1-BArF (Supplementary Fig. 68). Weak CT interactions between 1 and Cl− or SCN− were confirmed by UV-Vis spectra. The rest of the anions show no indication of CT due to their poor ED abilities.

Crystal structures of the host-guest complexes revealed the exact positioning of the bound anions within 1. Single crystals of 1-I and 1-Br were obtained by slow vapor diffusion of chloroform or Et2O into EtOH or MeOH solutions of 1-BArF in the presence of TBAI or TBABr. For 1-I (Fig. 3a), an I− anion resides at the center of the helicate host, maintaining a pseudo-C3 symmetry. The host-guest interactions involve a set of six C-H ∙ ∙ ∙ I− (2.50 − 3.32 Å for H ∙ ∙ ∙ I) contacts between the I− and three viologen units. For 1-Br (Fig. 3b), a Br− anion is also encapsulated inside the host but significantly displaced from the center, interacting with the host through three C-H ∙ ∙∙Br− (2.66 − 2.75 Å for H ∙ ∙∙Br) bonds with two viologen units and an anion-π contact (3.26 Å) with the third viologen unit. The offset guest positioning inside the cage leads to an asymmetric gourd-shaped structure, with a linker swinging inwards for the anion-π interaction. The different host-guest structures of 1-I and 1-Br reflect the guest adaptability of the cage arising from the flexible linkers. In both structures, multiple pyridinium units from the cage cooperate in interacting with the guest ions, which accounts for the large binding constants and the strong CT complexation.

Tetraarylborate anions with variable ED abilities also provide an opportunity to investigate the CT-based binding properties of the electron-poor cage. Five tetraarylborates, [B(Ph-R)4]− with R = OCH3, CH3, H, Cl, and F (in an order of descending ED strength, Fig. 4b) were chosen. Significant signal shifts in 1H NMR were observed upon adding tetraarylborates into 1-BArF in CD3OD. For instance, addition of BPh4− resulted in notable upfield shifts for H1, H2, H4, and H5 of 1 (Fig. 4a), indicating guest-induced conformational and/or charge-density changes of 1. The peaks of BPh4– also experience a significant upfield shift upon adding 0.5 equiv. compared to the signals of free BPh4–, and present gradual downfield shifts with increasing its concentration, consistent with the shielding effects of the anisotropic cones of the polyaromatic cage on the bound guest. Similar phenomena were also observed for other tetraarylborate anions (Supplementary Figs. 63–67) and there is an overall trend that the anions with higher ED strength cause larger shifts for the protons of 1. The binding constants obtained by 1H NMR titrations (Supplementary Table 2) are also positively correlated with the ED strength of tetraarylborates, supporting the predominance of CT interactions.

a 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD, 298 K) titrations of BPh4− into 1-BArF. Peaks from the guest are indicated by asterisks. b Color of the methanol solution of 1-BArF in the absence or presence of 6 equiv. [B(Ph-R)4]−. c UV-vis spectrophotometric titrations of BPh4− into a methanol solution of 1-BArF (0.1 mM).

The CT complexation is evidenced by the distinctive chronic response of 1-BArF towards tetraarylborates (Fig. 4b). The colorless solution of 1-BArF turned yellow upon addition of BPh4−, [B(Ph-Cl)4]−, or [B(Ph-F)4]−, whereas the addition of [B(Ph-OCH3)4]− or [B(Ph-CH3)4]−gave rise to maroon solutions. UV−vis spectrophotometric titrations of 1-BArF with the former three tetraarylborates present the gradual emergence of a broad absorption extending into the visible-light region (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 69c–d), which is assignable to guest-to-host CT transitions. For [B(Ph-OCH3)4]− and [B(Ph-CH3)4]−, the CT absorption bands extend longer into the visible-light region (Supplementary Fig. 69a–b).

Photochromism and generation of superoxide

Upon exposure to Xe lamp, the solution of 1-BArF in air-free methanol changed from colorless to blue (Fig. 5a). The UV-vis spectra showed new bands centered around 400 and 612 nm, which are characteristic of the viologen radical (V•+)59. The bands grew with irradiation time and reached saturation after 180 s. The photochromic response involves a PET process, in which the viologen unit V2+ accepts an electron to generate the blue-colored radical V•+ (Fig. 5c). The radical formation was further confirmed by the strong ESR (electron spin resonance) signal at g = 2.0040 (Fig. 5d). The photochromic phenomenon was not observed for 1-OTf but was for the mixture of 1-OTf and NaBArF (Supplementary Fig. 70), which evinced that BArF− serves as the ED in PET.

a UV-vis spectra of 1-BArF (190 µM) in air-free methanol upon Xe lamp irradiation for different periods of time. Insets: the reversible color changes upon irradiation and exposure to air. b Photochromic kinetics of 1-OTf (65 µM) in air-free methanol in the presence of 6 equiv. tetraarylborates. Insets: saturation color of the solutions. c Scheme illustrating PET from BArF− to V2+ and ET from V•+ to O2. d ESR spectra (CH3OH, 9.82 GHz, 298 K) of 1-BArF and L1-BArF irradiated under oxygen-free conditions. e ESR spectra (CH3OH, 9.82 GHz, 298 K) of 1-BArF and L1-BArF irradiated in the presence of O2 and DMPO. f Solvent effect on color-fading kinetics of irradiated 1-BArF (190 µM) upon exposure to air. g Anion effect (8 equiv.) on photochromism of 1-BArF (190 µM) in CH3OH.

Considering the incapability of TfO− as an ED, the PET behaviors of different tetraarylborates with 1 can thus be conveniently compared by adding [B(Ph-OCH3)4]−, BPh4−, or BArF− into solutions of 1-OTf. Results showed that the PET-based photochromic performance of the mixtures is positively correlated to the ED strengths and CT capability of tetraarylborates (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 71). BArF− gave the slowest and weakest response, and the response with [B(Ph-OCH3)4]− was the fastest and the strongest.

The photogenerated blue solutions (Fig. 5a, b), either from 1-BArF or from mixed 1-OTf and BAr4−, showed no indication of fading if kept under N2 overnight, but upon exposure to O2 or air, the solutions faded rapidly concomitant with the generation of biaryls and phenols (oxidation products of BAr4−) (Supplementary Fig. 72). The phenomenon indicates that the blue V•+ radical was quenched through electron transfer (ET) to O2, which generated superoxide (O2•−) for BAr4− oxidization (vide infra). The generation of O2•− was confirmed by spin-trapping ESR for a sample of 1-BArF irradiated under O2. The use of 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrrolin N-oxide (DMPO) as spin trap led to the sharp ESR signals of the DMPO-O2•− adduct (Fig. 5e).

The successive PET and ET processes of 1-BArF were also studied in other solvents. According to the UV-Vis spectra at different irradiation time, the photochromic contrast and kinetics of 1-BArF in different solvents (deoxygenated) present the following order: CH3COCH3 > DMSO > CH3CN ~ CH3OH (Supplementary Figs. 73-74). This indicates the highest PET efficiency in acetone. Interestingly, the fading rates of the blue radical solutions in air follow an approximately inverse order: CH3COCH3 < DMSO < CH3CN < < CH3OH (Fig. 5f), based on the ratio of At/A0, where A0 and At represent absorbances of the irradiated 1-BArF before and after exposure to air. In particular, the acetone solution did not fade overnight in air, while the methanol solution faded completely within 5 s. The fast fading in methanol indicates a high ET activity of V•+ in the solvent and a high superoxide-generation efficiency, which is conducive to photocatalytic oxidation.

Apart from solvent, the PET behaviors of 1-BArF can also be modulated by coexistent anions, showing a weakening, enhancement, or suppression effect (Fig. 5g). Upon introducing anions with poor ED ability, such as TfO−, NO3−, or Tf2N−, the photochromic response of 1-BArF was depressed, as indicated by the slowed growth of the characteristic radical absorptions with irradiation time (Supplementary Fig. 75). The weakening effect is attributed to the binding of these anions to the cage, which expels BArF− away from the cage to disadvantage the PET from BArF−.

In contrast, the addition of SCN−, Cl−, or Br− to 1-BArF significantly enhances the photochromic response (Supplementary Fig. 76). The degree of enhancement increases in the order SCN− < Cl− < Br− (Fig. 5g), which is consistent with the increase of their binding constants as well as CT capabilities with 1. The enhancement effect can be attributed to the dominance of these electron-rich (pseudo)halide ions in PET as EDs. Differently, although I− has the highest ED strength and also the largest binding constant with 1, the photochromic response of 1-BArF was significantly diminished by I− and even completely suppressed when in the presence of more than 4 equiv. of I−. (Supplementary Fig. 77). The strongly bound I− anions can prevent BArF− from accessing the cage, and the strong ground-state CT interaction between I− and V2+ can impair the electron deficiency of V2+, suppressing PET from BArF−. Moreover, the firm CT complexation allows not only ultrafast PET from I− to V2+ but also ultrafast back ET in the picosecond time scale, precluding a sufficiently long lifetime of the photogenerated V•+ to display its color39,59.

X-ray crystal structures of the cage after photochromism were determined. Slow evaporation of Et2O into a fully irradiated methanol solution of 1-BArF in the presence of Br− or SCN− under nitrogen led to single crystals of 1•-Br and 1•-SCN. The crystals show a dark blue color characteristic of V•+. While eight anions are required for charge balance of a nonradical cage, ion chromatography revealed the existence of seven and six counteranions per cage for 1•-Br and 1•-SCN, respectively. The anion contents indicate that 1/3 and 2/3 of the viologen units in the two compounds are V•+. Crystallographic analysis allowed the discrimination of V•+ from V2+ in 1•-Br. As shown in Fig. 3c, the interannular torsion angles and the interannular C-C bond distances of two viologen units in 1•-Br are similar to those of V2+ in 1-Br (25.3–40.6° and 1.47–1.50 Å, respectively). However, the third viologen unit in 1•-Br shows a much smaller torsion angle and a shorter C-C bond (5.0° and 1.46 Å, Fig. 3c), which can be ascribed to V•+. The differences reflect the increased planarity and bond order between the two pyridinium rings from V2+ to V•+60. Compared with 1-Br, 1•-Br also presents significant changes in cage shape and host-guest interactions. Different from the gourd-like shape and the off-center Br− encapsulation of the cage in 1-Br (Fig. 3b), the cage in 1•-Br adopts the quasiregular helical shape and encapsulates Br− at the center through hydrogen bonding interactions (Supplementary Fig. 51).

The overall structure of the cage in 1•-SCN (Supplementary Fig. 52a) is similar to that in 1-SCN (Fig. 2a), exhibiting the helical shape with no anions inside. Differently, V•+ and V2+ in 1•-SCN cannot be crystallographically differentiated. Nevertheless, in the radical-containing cage, the average inter-annular torsion angle is decreased and the average inter-annular C-C bond is shortened (Supplementary Fig. 52b).

Photocatalytic oxidation of tetraarylborates

The efficient PET and superoxide-generation capabilities of 1 with tetraarylborates provide an opportunity for photocatalytic oxidation of tetraarylborates. Chemical, electrochemical, and photochemical oxidation of tetraarylborates has been studied as new approaches towards biaryls61,62,63,64,65,66,67. In these cases, biaryls are usually generated by coupling two of the four aryl rings in the substrates, with the byproduct having been reported to be diarylborinic acids or left unidentified. The use of 1 as a photocatalyst enables simultaneous oxidative coupling and hydroxylation, generating biaryls and phenols in the 1:2 molar ratio, with no other side products. Note that both products are useful building blocks in chemical and pharmaceutical industries.

We first investigated the oxidation of NaBPh4 in methanol with 1-NTf2 as the photocatalyst. 1-NTf2 was chosen because Tf2N−, as a CT- and PET-inactive anion showing the weakest binding with 1, is not expected to perturb the interactions of 1 with substrates. Under mild conditions (room temperature, O2 balloon, 6 W light at 400 nm), the use of 10 mol% 1-NTf2 gave rise to excellent conversion to biphenyl and phenol (entry 1 in Table 1). The reaction in air also gave satisfactory results (entry 2). In the absence of any catalyst, light, or dioxygen, no effective conversion was observed (entries 3-5), which confirms the catalytic role of 1-NTf2 in the light-driven aerobic oxidation reaction. The inactivity of Cp2ZrCl2 (entry 6) suggests the catalytic activity of 1-NTf2 arises from the organic linker rather than the metal center.

Catalytic performance of 1-NTf2 in different solvents increases in the order CH3COCH3 < DMSO < CH3CN < CH3OH (entries 1 and 8-10). The solvent effect is consistent with the solvent dependence of the color-fading kinetics observed in photochromic studies (Fig. 5f): the solvent that affords faster V•+-to-O2 ET allows faster regeneration of V2+ for the next cycle of PET with the substrate and also faster generation of O2•− for oxidation. Photoconversion of BPh4− catalyzed by 1 with different anions decreases as 1-NTf2 > 1-OTf > 1-Cl (entries 1 and 11-12, Supplementary Fig. 78). The anion dependence can be related to the binding affinity (Supplementary Table 1): the competing anion with strong affinity adversely influences the interactions of BPh4− with 1, and the electron-donating anion like Cl− also competes with BPh4− in PET. When 1-BPh4 was used as the source of the catalytic cage, the conversion was slightly higher than that using 1-NTf2 (entry 13), confirming a weak adverse effect of the Tf2N − ion.

Impressively, water-soluble 1-NO3 allows the reaction to be conducted in water with excellent yields (entry 14 in Table 1). Notably, the water-insoluble biphenyl product precipitates directly from the aqueous solution, allowing facile separation. These results complied with the principles of green chemistry: molecular oxygen as oxidant, water as solvent, high selectivity, and facile isolation of products.

To verify the reliability of 1 as the photocatalyst, tetraarylborates with varying substitution groups were tested (Table 2). All substrates underwent simultaneous oxidative coupling and hydroxylation to give biaryls and phenols. For [B(Ph-R)4]− with 1-NTf2 in CH3OH, the conversion after 10 h varies in the following order: R = OCH3 > CH3 > H > Cl > F. BArF− shows the lowest reactivity and requires longer time. The order, also observed in their binding hierarchy with 1 and photochromic response, is in good agreement with ED strength of the substrates. The oxidation of [B(Ph-R)4]− (R = H, Cl or F) with 1-NO3 in water also gave satisfactory yields (>80%, 15 h). The low conversions for [B(Ph-OCH3)4]− and [B(Ph-CH3)4]− and the trace conversion for BArF− result from their low solubility in water (Table 2).

To determine whether the aryl coupling is intermolecular or intramolecular, the photocatalytic reaction was performed with a mixture of [B(Ph-OCH3)4]− and BPh4− (Supplementary Fig. 79). Only homocoupling biaryl products (biphenyl and 4,4’-dimethoxybiphenyl) were obtained, which supports intramolecular coupling.

Based on the investigations and previous reports for oxidation of tetraarylborates and other organoboron65,66, the catalytic mechanism is proposed in Fig. 6. The cage undergoes PET with bound BPh4− to produce BPh4• (I) and subsequent ET with O2 to produce O2•−. The intramolecular C-C coupling through 1,2-rearrangement in I leads to intermediate II67, to which O2•− is added to give III. The release of biphenyl product from III and concomitant intramolecular ET to coordinated O2•− generate a peroxide intermediate (IV), which readily reacts with water to give V. V undergoes B-to-O phenyl migration and subsequent hydrolysis to produce phenol product and phenylboronate (VII)68. Finally, VII undergoes oxidative hydroxylation with 1 as the photocatalyst to produce another equivalent of phenol, which has been verified by the photocatalytic tests starting directly with NaBPh(OH)3 (Supplementary Fig. 80).

1 undergoes PET with BPh4− to produce BPh4• (I) and subsequent ET with O2 to produce O2•−. The intramolecular C-C coupling through 1,2-rearrangement in I leads to intermediate II, to which O2•− is added to give III. Biphenyl product is released from III, along with intramolecular ET to coordinated O2•− generating a peroxide intermediate IV. IV reacts with water to give V, which then undergoes B-to-O phenyl migration to give VI. Hydrolysis of VI produces phenol product and VII, the latter of which further undergoes oxidative hydroxylation in the presence of 1 to produce another equivalent of phenol.

Performances of cage in comparison to ligand and CT contribution

Ligand L1-BArF exhibited no appreciable 1H NMR shifts upon introducing an excess of TfO−, I−, or BPh4− (Supplementary Figs. 81–82), suggesting interactions of these anions with the free ligand are very weak. Addition of electron-donating anions, such as BPh4−, [B(Ph-OCH3)4]−, and I− into L1-BArF led to only faint changes in color and UV-Vis spectra (Fig. 7a, b and Supplementary Figs. 83–84), proving weak CT complexation. The properties of L1-BArF, contrary to those of 1-BArF, demonstrate that the gathering of multiple viologen linkers in one cage leads to much enhanced CT binding capabilities.

a UV-vis spectra of 1-BArF (100 µM) and L1-BArF (300 µM) before and after addition of BPh4− (600 µM) in CH3OH. The filled areas show the absorption increase after BPh4− addition. Insets: color after BPh4− addition. b Comparison of the absorbances for 1-BArF (100 µM) and L1-BArF (300 µM) in the presence of BPh4− (600 µM), [B(Ph-OCH3)4]− (600 µM), or I− (800 µM) in CH3OH. c UV-vis spectra of 1-BArF (190 µM) and L1-BArF (570 µM) in CH3OH before and after Xe-light irradiation for 150 s. The filled areas show the absorption increase after irradiation. Insets: color after irradiation. d Photochromic kinetics of the mixture of 1-NTf2 (65 µM) or L1-NTf2 (195 µM) with BPh4− (390 µM) or BArF− (390 µM) in CH3OH. Insets: color after irradiation. e, f, Kinetics for photooxidation of BPh4− catalyzed by 1 or L1 in CH3OH (e) and in H2O (f). Conditions: 10 mol% for 1 or 30 mol% for L1, O2, 6 W light at 400 nm.

In contrast to the pronounced photochromic response of 1-BArF or mixed 1-NTf2 and BPh4−, Xe-light irradiation of L1-BArF or mixed L1-NTf2 and BPh4− led to much fainter blue colors as well as much weaker radical signals in ESR and UV-Vis spectra (Figs. 5d and 7c, d). The above results prove that assembling the ligand into the cage causes remarkable enhancements in PET efficiency. To quantitatively evaluate the cage effect, PET enhancement factors (EFs) were calculated according to the ratio of the radical absorbances of the cage and the ligand after irradiation (AC/AL). The factor represents a measure of the concentration ratio of V•+ generated from the cage against that from the free ligand. The factors are up to 5.1 for BArF− and 7.4 for BPh4− after irradiation for 150 s (Supplementary Figs. 85–87). Since BArF− is a poor ED showing no effective CT complexation with either the cage or the ligand, the PET enhancement could be associated with the high positive charge of the cage, which facilitates the access and contact of BArF− for PET. The even larger EF observed for BPh4− than BArF− highlights the significant contribution of host-guest CT complexation to the PET, which can prevent diffusion dependence of PET.

Efficient PET is a prerequisite for efficient superoxide-generation through ET from V•+ to O2. Spin-trapping ESR tests with the ligand showed very weak DMPO-O2•− signals, in contrast to the strong signals observed with the cage (Fig. 5e). The comparison evinces that the ability to produce O2•− is greatly enhanced after cage formation.

To evaluate the cage effect on photocatalysis, kinetic experiments were carried out for photooxidation of BPh4−. As shown in Fig. 7e-f, the reaction with 1-NTf2 (in methanol) or 1-NO3 (in water) as catalyst proceeded much faster than the reaction catalyzed by the corresponding ligand. When the conversion of BPh4− with the cage was completed, only one third of the substrate was converted by the ligand. In the first 2 h, the turnover frequencies (TOFs) over 1-NTf2 and 1-NO3 are higher than those over the ligands by a factor of 3.6 and 4.0, respectively. Note that oxidative coupling of BArF− has succeeded with electrochemical method62 but failed with chemical oxidants64,65 for its high oxidation potential. Our results show that BArF− can be oxidized by O2 using 1-NTf2 as photocatalyst, although prolonged time is needed (Table 2). However, the use of L1-NTf2 only led to a trace conversion, demonstrating the high potency of the MOCs in upgrading photocatalytic performances.

Discussion

In conclusion, introduction of BArF− as the counteranions of cationic ligands enable homogeneous assembly processes in solutions, resulting in soluble Zr-MOCs. Helicate-like cage 1 is capable of binding a variety of anions, which is enabled by the Coulombic interactions for anions with poor ED strength and dominated by CT complexation for electron-donating halides and tetraarylborates. In comparison to the free ligand, the CT complexation is significantly enhanced owing to the cooperation of the multiple cationic viologen groups in the cage. The enhanced binding leads to pronounced photochromism due to anion-to-viologen PET, which can be modulated by coexistent anions and was characterized by X-ray crystal structures. The photogenerated viologen radical readily undergoes ET to dioxygen to produce superoxide. Combining the efficient PET and superoxide-generation properties, 1 can effectively catalyze photooxidation of tetraarylborates, which allows the simultaneous synthesis of biaryls and phenols through aryl coupling and hydroxylation. This work demonstrates the great potential of using host-guest CT complexation of MOCs to manipulate PET for sophisticated responsive and catalytic performances. Extended exploration with various electron-deficient soluble Zr-MOCs (e.g., 2-4) is underway in our laboratory.

Methods

Synthesis of 1-BArF

L1-BArF (20 mg, 9.3 μmol) and Cp2ZrCl2 (5.8 mg, 19 μmol) were added into a solution mixture containing 3.0 mL CH3OH and 0.12 mL H2O. The reaction mixture was stirred and kept at 65 °C overnight. After cooling to room temperature, 3.0 mL H2O was added and a large amount of white precipitate appeared. The precipitate was collected through centrifugation, thoroughly washed with water (5 mL × 3), and dried under vacuum to obtain 1-BArF (21 mg, 74% yield).

Synthesis of 1-X (X = NO3, OTf, PF6, Cl, and NTf2)

1-BArF (50 mg, 5.4 µmol) was dissolved in 2.0 mL CH3OH. Upon addition of TBANO3 (24 mg, 81 µmol), a large amount of white precipitate appeared immediately. The precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with CH3OH (3.0 × 10 mL), and dried under vacuum to obtain 1-NO3 (81% yield).

1-NO3 (50 mg, 17 µmol) was dissolved in 5.0 mL H2O. Upon addition of TBAX (X = OTf, PF6, Cl, or NTf2, 15 equiv.) in 0.5 mL CH3OH, a large amount of precipitate appeared immediately. The precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with H2O (5 mL for X = Cl, 3 × 10 mL for others), and dried under vacuum to obtain the corresponding compounds (>80% yield).

Measurements

NMR spectra were recorded using a Bruker 400 MHz Avance III HD Smart Probe (1H, 13C, 19F, and 2D experiments). Chemical shifts for 1H, 13C, and 19F are reported in ppm on the δ scale; 1H, 13C, and 19F were referenced to the residual solvent peak. Coupling constants (J) are reported in Hz. UV-vis absorption spectroscopy was recorded on a HIMADZU UV-2700 spectrometer in the 200–800 nm regions. Electron-spin resonance (ESR) signals were recorded on a Bruker Elexsys 580 spectrometer with a 100 kHz magnetic field in the X band at room temperature. Photochromic experiments were carried out in CEL-HXUV300 300 W xenon lamp system. All anaerobic operations are carried out using the LG1200/750TS glovebox. Photocatalysis was performed in Photosyn-10 parallel photoreactor, equipped with a 400 nm LED light. High-resolution mass spectra were collected on an HPLC-Q-TOF-MS spectrometer in acetonitrile/methanol solution. Elemental analyses were performed on an Elementar Vario ELIII analyzer. Anion contents were measured using an ICS-5000+/900 ion chromatograph.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information file. Additional data are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to D.Z. or E.-Q.G. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this paper have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under the deposition numbers 2356395, 1-SCN; 2356397, 1-I; 2356396, 1-Br; 2357282, 1•-SCN; 2359410, 1•-Br; and 2356398, 3-SCN. Copies of these data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Zhang, X. et al. Fine-tuning apertures of metal-organic cages: encapsulation of carbon dioxide in solution and solid state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 11621–11627 (2019).

Pullen, S. & Clever, G. H. Mixed-ligand metal-organic frameworks and heteroleptic coordination cages as multifunctional scaffolds-a comparison. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 3052–3064 (2018).

Pérez-Ferreiro, M., Paz-Insua, M. & Mosquera, J. Mimicking nature’s stereoselectivity through coordination cages. Chem 9, 1355–1356 (2023).

Lu, S. et al. Encapsulating semiconductor quantum dots in supramolecular cages enables ultrafast guest–host electron and vibrational energy transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 5191–5202 (2023).

Fuertes-Espinosa, C. et al. Purification of uranium-based endohedral metallofullerenes (EMFs) by selective supramolecular encapsulation and release. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 11294–11299 (2018).

Zhang, W. Y., Lin, Y. J., Han, Y. F. & Jin, G. X. Facile separation of regioisomeric compounds by a heteronuclear organometallic capsule. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 10700–10707 (2016).

Wang, L. J., Bai, S. & Han, Y. F. Water-soluble self-assembled cage with triangular metal-metal-bonded units enabling the sequential selective separation of alkanes and isomeric molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 16191–16198 (2022).

Zhang, D., Ronson, T. K., Mosquera, J., Martinez, A. & Nitschke, J. R. Selective anion extraction and recovery using a FeII4L4 cage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 3717–3721 (2018).

Zhang, D., Ronson, T. K., Lavendomme, R. & Nitschke, J. R. Selective separation of polyaromatic hydrocarbons by phase transfer of coordination cages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 18949–18953 (2019).

Mal, P., Breiner, B., Rissanen, K. & Nitschke, J. R. White phosphorus is air-stable within a self-assembled tetrahedral capsule. Science 324, 1697–1699 (2009).

Yoshizawa, M., Tamura, M. & Fujita, M. Diels-alder in aqueous molecular hosts: unusual regioselectivity and efficient catalysis. Science 312, 251–254 (2006).

Omagari, T., Suzuki, A., Akita, M. & Yoshizawa, M. Efficient catalytic epoxidation in water by axial N-ligand-free Mn-porphyrins within a micellar capsule. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 499–502 (2016).

Cullen, W., Misuraca, M. C., Hunter, C. A., Williams, N. H. & Ward, M. D. Highly efficient catalysis of the Kemp elimination in the cavity of a cubic coordination cage. Nat. Chem. 8, 231–236 (2016).

Howlader, P., Das, P., Zangrando, E. & Mukherjee, P. S. Urea-functionalized self-assembled molecular prism for heterogeneous catalysis in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 1668–1676 (2016).

Fang, Y. et al. Catalytic reactions within the cavity of coordination cages. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 4707–4730 (2019).

Zhao, L. et al. Catalytic properties of chemical transformation within the confined pockets of Werner-type capsules. Coord. Chem. Rev. 378, 151–187 (2019).

Young, M. C., Holloway, L. R., Johnson, A. M. & Hooley, R. J. A supramolecular sorting hat: stereocontrol in metal-ligand self-assembly by complementary hydrogen bonding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 9832–9836 (2014).

Hong, C. M., Bergman, R. G., Raymond, K. N. & Toste, F. D. Self-assembled tetrahedral hosts as supramolecular catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 2447–2455 (2018).

Miyamura, H., Bergman, R. G., Raymond, K. N. & Toste, F. D. Heterogeneous supramolecular catalysis through immobilization of anionic M4L6 assemblies on cationic polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 19327–19338 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. A historical overview of the activation and porosity of metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 7406–7427 (2020).

Bobbitt, N. S. et al. Metal-organic frameworks for the removal of toxic industrial chemicals and chemical warfare agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 3357–3385 (2017).

Cook, T. R., Zheng, Y. R. & Stang, P. J. Metal-organic frameworks and self-assembled supramolecular coordination complexes: comparing and contrasting the design, synthesis, and functionality of metal-organic materials. Chem. Rev. 113, 734–777 (2013).

Pilgrim, B. S. & Champness, N. R. Metal-organic frameworks and metal-organic cages - a perspective. ChemPlusChem 85, 1842–1856 (2020).

Moser, C. C., Page, C. C., Farid, R. & Dutton, P. L. Biological electron transfer. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 27, 263–274 (1995).

Gray, H. B. & Winkler, J. R. Electron transfer in proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65, 537–561 (1996).

Jing, X., He, C., Zhao, L. & Duan, C. Photochemical properties of host-guest supramolecular systems with structurally confined metal-organic capsules. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 100–109 (2019).

Jin, Y., Zhang, Q., Zhang, Y. & Duan, C. Electron transfer in the confined environments of metal-organic coordination supramolecular systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 5561–5600 (2020).

Ham, R., Nielsen, C. J., Pullen, S. & Reek, J. N. H. Supramolecular coordination cages for artificial photosynthesis and synthetic photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 123, 5225–5261 (2023).

Das, A., Mandal, I., Venkatramani, R. & Dasgupta, J. Ultrafast photoactivation of C-H bonds inside water-soluble nanocages. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav4806 (2019).

Yan, D. N. et al. Photooxidase mimicking with adaptive coordination molecular capsules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 16087–16094 (2021).

Ghosal, S., Das, A., Roy, D. & Dasgupta, J. Tuning light-driven oxidation of styrene inside water-soluble nanocages. Nat. Commun. 15, 1810 (2024).

Sun, J.-K., Yang, X.-D., Yang, G.-Y. & Zhang, J. Bipyridinium derivative-based coordination polymers: From synthesis to materials applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 378, 533–560 (2019).

Garci, A. et al. Mechanically interlocked pyrene-based photocatalysts. Nat. Catal. 5, 524–533 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Chromophore-inspired design of pyridinium-based metal-organic polymers for dual photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202204918 (2022).

Tang, B., Xu, W., Xu, J. F. & Zhang, X. Transforming a fluorochrome to an efficient photocatalyst for oxidative hydroxylation: a supramolecular dimerization strategy based on host-enhanced charge transfer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 9384–9388 (2021).

Ma, S. et al. Redox-active and Brønsted basic dual sites for photocatalytic activation of benzylic C–H bonds based on pyridinium derivatives. Green. Chem. 24, 2492–2498 (2022).

Li, S. L. et al. X-ray and UV dual photochromism, thermochromism, electrochromism, and amine-selective chemochromism in an anderson-like Zn7 cluster-based 7-fold interpenetrated framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 12663–12672 (2019).

Luo, Y. et al. Photo/electrochromic dual responsive behavior of a cage-like Zr(IV)-viologen metal-organic polyhedron (MOP). Inorg. Chem. 61, 2813–2823 (2022).

Gong, T. et al. Versatile and switchable responsive properties of a lanthanide-viologen metal-organic framework. Small 15, e1803468 (2019).

Sui, Q. et al. Piezochromism and hydrochromism through electron transfer: new stories for viologen materials. Chem. Sci. 8, 2758–2768 (2017).

Dale, E. J. et al. ExCage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 10669–10682 (2014).

Lei, Y. et al. A trefoil knot self-templated through imination in water. Nat. Commun. 13, 3557 (2022).

Liu, G., Ju, Z., Yuan, D. & Hong, M. In situ construction of a coordination zirconocene tetrahedron. Inorg. Chem. 52, 13815–13817 (2013).

El-Sayed, E. M., Yuan, Y. D., Zhao, D. & Yuan, D. Zirconium metal-organic cages: synthesis and applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 1546–1560 (2022).

Gosselin, A. J. et al. Ligand-based phase control in porous zirconium coordination cages. Chem. Mater. 32, 5872–5878 (2020).

Lee, S. et al. Porous Zr6L3 metallocage with synergetic binding centers for CO2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 8685–8691 (2018).

Cheng, S. et al. Synthesis, crystal structure and iodine capture of Zr-based metal-organic polyhedron. Inorg. Chim. Acta 516, 120174 (2021).

Jiao, J. et al. Design and assembly of chiral coordination cages for asymmetric sequential reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2251–2259 (2018).

Ji, C. et al. A high-efficiency dye-sensitized Pt(II) decorated metal-organic cage for visible-light-driven hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 285, 119782 (2021).

Liu, G. et al. Thin-film nanocomposite membranes containing water-stable zirconium metal–organic cages for desalination. ACS Mater. Lett. 3, 268–274 (2021).

Shi, W. J. et al. Supramolecular coordination cages based on N-heterocyclic carbene-gold(I) ligands and their precursors: self-assembly, structural transformation and guest-binding properties. Chem. Eur. J. 27, 7853–7861 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Self-healing hyper-cross-linked metal-organic polyhedra (HCMOPs) membranes with antimicrobial activity and highly selective separation properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 12064–12070 (2019).

Sullivan, M. G. et al. Altering the solubility of metal-organic polyhedra via pendant functionalization of Cp3Zr3OOH3 nodes. Dalton Trans. 52, 338–346 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Artificial biomolecular channels: enantioselective transmembrane transport of amino acids mediated by homochiral zirconium metal-organic cages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 20939–20951 (2021).

Pastore, V. J. et al. Clickable norbornene-based zirconium carboxylate polyhedra. Chem. Mater. 35, 1651–1658 (2023).

Grommet, A. B. et al. Anion exchange drives reversible phase transfer of coordination cages and their cargoes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 14770–14776 (2018).

Kobayashi, H. Weakly coordinating bulky anions designed by efficient use of polyfluoro-substitution. J. Fluor. Chem. 105, 201–203 (2000).

Krossing, I. & Raabe, I. Noncoordinating anions-fact or fiction? A survey of likely candidates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 2066–2090 (2004).

Jarzȩba, W., Pommeret, S. & Mialocq, J.-C. Ultrafast dynamics of the excited methylviologen–iodide charge transfer complexes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 333, 419–426 (2001).

Clennan, E. Viologen embedded zeolites. Coord. Chem. Rev. 248, 477–492 (2004).

Dhital, R. N. & Sakurai, H. Oxidative coupling of organoboron compounds. Asian J. Org. Chem. 3, 668–684 (2014).

Beil, S. B., Mohle, S., Enders, P. & Waldvogel, S. R. Electrochemical instability of highly fluorinated tetraphenyl borates and syntheses of their respective biphenyls. Chem. Commun. 54, 6128–6131 (2018).

Mizuno, H., Sakurai, H., Amaya, T. & Hirao, T. Oxovanadium(v)-catalyzed oxidative biaryl synthesis from organoborate under O2. Chem. Commun. 5042−5044 (2006).

Lu, Z., Lavendomme, R., Burghaus, O. & Nitschke, J. R. A Zn4L6 capsule with enhanced catalytic C-C bond formation activity upon C60 binding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 9073–9077 (2019).

Gerleve, C. & Studer, A. Transition-metal-free oxidative cross-coupling of tetraarylborates to biaryls using organic oxidants. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 15468–15473 (2020).

Music, A. et al. Electrochemical synthesis of biaryls via oxidative intramolecular coupling of tetra(hetero)arylborates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 4341–4348 (2020).

Music, A. et al. Photocatalyzed transition-metal-free oxidative cross-coupling reactions of tetraorganoborates. Chem. Eur. J. 27, 4322–4326 (2021).

Zou, Y. Q. et al. Highly efficient aerobic oxidative hydroxylation of arylboronic acids: photoredox catalysis using visible light. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 784–788 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22201075, D.Z.; 21971069, E.-Q.G.). R.L. is a Postdoctoral Researcher of the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique—FNRS. D.Z., E.-Q.G., and S.L. are grateful for financial support from the SINOPEC Research Institute of Petroleum Processing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Z., E.-Q.G., and G.L. conceived and designed the research. G.L. carried out the majority of the experimental work. Z.D. synthesized cage 3. Y.L. and Y.X. synthesized some tetraarylborate guests. C.W., R.L., and S.L. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results. G.L. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, G., Du, Z., Wu, C. et al. Charge-transfer complexation of coordination cages for enhanced photochromism and photocatalysis. Nat Commun 16, 546 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55893-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55893-z