Abstract

The propagation of interfacial waves in free and constrained conditions, such as deep and shallow water, has been broadly studied over centuries. It is a common event that anyone can witness, while contemplating the ocean waves washing ashore. As a complementary configuration, this work introduces waves propagating on an interface restricted by its pinning to the solid microstructures of an underwater superhydrophobic surface. The latter has the ability to stabilize a well-defined microscale gas layer, called a plastron, trapped between the water and the solid phase. The acoustic radiation force produced with focused MHz ultrasound successfully triggers kHz “plastronic waves”, i.e., capillary waves travelling on a plastron’s gas-water interface. The exposed waves possess interesting features, i.e., (i) a high propagation speed up to 45 times faster than conventional deep water capillary waves of comparable wavelength and (ii) a relation of the propagation speed with the geometry of the microstructures. Based on this and on the observed variation of wave speed over time in conditions of gas-undersaturated or -supersaturated water, the usefulness of the plastronic waves for the non-destructive monitoring of the plastron’s stability and the spontaneous air diffusion is eventually demonstrated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Capillary waves, also known as ripples, are surface tension -dominated mechanical perturbations of a liquid-gas interface. Evocations date back at least to the first century AD, when Pliny the Elder was reporting on the absence of ripples in the wake of ships releasing surfactants1. The earliest description of capillary waves in the modern scientific sense is attributed to John Scott Russell2. His investigation portrayed the orbital motion of the water molecules carried on by the swelling interface and measured propagation speeds in the range 0.2–0.9 m s−1. The influence of a nearby seabed on the wave motion has been first assessed for the case of gravity-driven waves with longer wavelength λ, in a configuration of intermediate depth of the water medium, with a first linear model proposed by Sir Airy in 18413, further developed to account for weak nonlinear effects by Sir Stokes4 in 1847. Later extensions to these models would consider e.g., high wave steepness5 and pure capillary waves6. Together, these works would contribute in particular to describing a wavenumber-to-frequency relation, commonly called dispersion relation. For a wave travelling at an interface between two fluid phases (i.e., an interfacial wave) a and b, the angular frequency Ω(k) writes

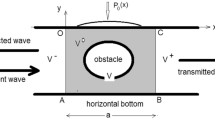

where g and σ are gravity and surface tension. k = 2π/λ is the wavenumber. ρa and ha (respectively, ρb and hb) are the density and thickness of the fluid phase a (respectively, b). At an air-water interface, a minimum for the wave propagation speed, here referred to as the phase speed cp = Ω(k)/k, can be found for λ ≃ 1.7 cm and equals ca. 0.23 m s−1, in a condition of deep water (h ≫ λ). Interfacial waves on water are generally categorised, according to their wavelength into two distinct groups, capillary (λ ≤ 1.7 cm) and gravity (λ ≥ 1.7 cm) waves, mainly governed by distinct restoring forces, respectively surface tension and gravity7. Capillary and gravity waves are dispersive, meaning that their propagation speed depends on their wavelength, according to Eq. (1), a graphical representation of which is provided as Supplementary Information (SI), in Fig. S1.

The wave-driven orbital motion of water molecules constrained by a shallow water configuration (h ≪ λ) experiences a no-slip boundary condition at the water-bottom interface8, causing the wave to slow down3 and its amplitude to increase9. This effect is known as wave shoaling and is opposed to the restoring forces, such as gravity and interfacial tensions, which try to restore the equilibrium state. The pinning contact of the water interface to the walls of a channel in which a wave travels can also exert an additional restoring force, opposite to the interface displacement, which further stiffens the gas-water interface10 and speeds up the wave propagation10,11. This effect is intensified, when the wall spacing is narrowed12 and the water interface becomes curved13. In contrast, a condition of freely moving contact line agrees with the theory of waves on constraint-free interfaces10,14. Together, this abundant literature constitutes in-depth knowledge of water waves in various configurations, which all share a common determinant, namely the assumption that the air or gas phase above the water interface is boundary-free and inviscid.

While capillary waves have been extensively studied in free conditions (e.g., deep water)2,3,4,5,6,7 and in constrained conditions (e.g., shallow water or narrow channel)3,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, to the best of our knowledge, systematic studies on capillary waves at an interface constrained by its pinning to an array of microstructures are still lacking. Such conditions could be facilitated by the superhydrophobic state exhibiting a superior water repellency. Nature itself offers fascinating examples, such as lotus15 and salvinia16 leaves, aquatic arthropod exoskeletons17, feathers18, serving as remarkable sources of inspiration19. Superhydrophobicity is enabled by a combination of surface chemistry20 and nano-micro topography, which prevents liquid entry and impalement20,21. Underwater immersion, a thin layer of air is trapped between the micropillars, where the micropillar tops support the water like a fakir on a bed of nails. Collectively, this is known as a plastron, or the Cassie state22. However, the water-repellent feature can be compromised by spontaneous changes in the environment20. In particular, the plastron can experience depletion as a result of gas dissolution or pressure-induced impalement23,24. Eventually, the plastron could be lost and the surface fully wetted, the so-called Wenzel state25, while partially wet states would be here referred to as intermediate states. The plastron condition is typically assessed optically by bright-field microscopy23,26, total internal reflection technique24,27, or confocal microscopy28. Acoustics-based alternatives to optics21 show limitations due to (i) complexity and cost related to integrating a transducer into the studied surface29,30, or (ii) lack of access to the plastron dynamics and intermediate wetting states31.

Mechanical waves carry their propagation medium’s properties, making them useful tools for investigating optically opaque or contamination-sensitive media, such as, respectively, the Earth’s crust32 and biological tissues33, or soft matter and biological fluids34,35. With this in mind, the examination of the dynamics of the gas-water interface, constrained by microstructures, in response to mechanical stress could provide a means for remotely monitoring the plastron’s condition, wetting state, and spontaneous gas diffusion over time. Accordingly, this work presents an original configuration of capillary waves induced by ultrasound (US), travelling on a gas-water interface bounded to the solid microstructures of a superhydrophobic plastron. The wave behaviour is studied by varying the density of the three-phase contact line and the pillar height. The sensing potential of these waves for remotely monitoring the plastron and its intermediate wetting state is eventually addressed.

Results and discussion

Superhydrophobic underwater medium for interfacial waves

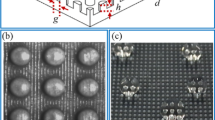

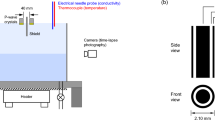

Made of PDMS (polydimethylsiloxane), superhydrophobic samples with well-defined surface roughness were prepared by soft lithography, the details of which are given in “Microfabrication”. The surface topography consists of a 5 mm × 5 mm array of cylindrical micropillars arranged in a square lattice. While the pillar diameter is kept constant (20 μm), the investigated configurations differ by the pillar height h (21, 25, 37, 53 and 71 μm) or the inter-pillar spacing s (15, 20, 25, 35, 45, 55 and 65 μm). A graphical summary of the employed configurations is provided in SI, Fig. S2. The experimental setup, schematically illustrated in Fig. 1a, b and described in “Experimental setup ”, employs a superhydrophobic surface immersed in water. The image of a specimen (h = 25 μm, s = 25 μm), acquired by Scanning Electron Microscopy, is given in Fig. 1c. Along with high-speed imaging (159090 fps) and a high-intensity focused US (HIFU) transducer (2.5 MHz), the experimental configuration allowed to generate and to observe the periodic perturbations of the gas-water interface of a plastron induced by acoustic radiation force (ARF), enabled by focused US. Given that the imaging frame rate is considerably smaller than the acoustic frequency (2.5 MHz), this work does not report on the acoustic time-scale dynamics of the plastron, but rather on the fluidic time-scale phenomena set into motion by the second-order nonlinear forces of the acoustic field. The ARF-induced interface motion modifies the light refraction leading to local changes of light transmission through the sample, providing a top-view visualisation of the plastron spatiotemporal perturbations at microsecond time scales.

a The experimental setup, schematised here, featuring a high-speed camera (159090 fps) and a 2.5 MHz high-intensity focused US (HIFU) transducer, allows the study of a water-submerged superhydrophobic surface placed at the focus of co-axial optical and acoustic fields. The response of the plastron to an amplitude-modulated (AM) US pulse takes the shape of interfacial perturbations travelling along the gas-water interface from the acoustic focal point, the ripples with same coherence forming patterns of concentric circles, schematised in (b). c An exemplary image acquired by Scanning Electron Microscopy shows the details of a superhydrophobic sample with pillar spacing s = 25 μm and height h = 25 μm. d For the same pillar geometry, the wave frequency as a function of the applied AM frequency always exhibits a 2:1 ratio, demonstrating the control of the frequency of the produced plastronic waves. e The axisymmetric field of acoustic pressure produced by the HIFU transducer was measured in a free field (in the absence of a superhydrophobic surface) using a needle hydrophone. f The radial waves at the gas-water interface (s = 25 μm, h = 25 μm) are optically assessed from the top-view refraction patterns induced by the moving gas-water interface. The wave analysis based on the tracking of the wavefronts, i.e., the wave lines of same phase, normally done in polar coordinates (Details in SI, Figs. S10 and S11), is here conceptualised on an unprocessed high-speed footage.

Acoustically induced plastronic waves

Periodically poking an underwater plastron with an US excitation with spatial acoustic distribution given in Fig. 1e allows to generate coherent ripples in a circularly symmetric fashion, as exemplified in Fig. 1f. This essentially results from the acoustic waves having sufficient time-averaged energy density to provide an ARF able to deform the gas-water interface36. As per existing theoretical models37, a focal acoustic pressure of 1.5 MPa (measurement in a free field condition) is expected to be able to induce a Cassie-to-Wenzel transition of the plastron, given that this pressure would correspond to a radiation force ≥540 Pa, which is superior to the critical impalement pressure of all plastron configurations investigated in this work. However, considering that the US actuation employed here is of short duration (<1 ms) and modulated in amplitude, as detailed hereafter, it might not provide sufficient time for the inertia-driven interface dynamics to locally generate plastron collapse. This aspect is briefly commented in SI, Section 1.A.

Since conventional interfacial waves are dispersive, a control of the wave frequency is needed to assess the influence of the plastron geometry only on the wave behaviour. To achieve this, an amplitude modulation (AM) was applied to the 2.5 MHz sinusoidal wave delivered by the HIFU transducer, expected to yield an ARF frequency acting on the superhydrophobic surface approximately at double the frequency of the AM. The employed driving signal has the form \(y(t)=A\sin (2\pi {f}_{{{{\rm{ac}}}}}t)\cdot \sin (2\pi t/{T}_{{{{\rm{AM}}}}})\), with the constants A = 0.5 V and fac = 2.5 MHz. The only changing parameter in the signal is the AM period TAM, which is in the range 100−500 μs and affects the total duration of the signal that lasts 3 cycles of AM, so that t ∈ [0, 3TAM].

Under the action of that AM driving pressure, a dynamic game of forces sets up between the US waves periodically poking the interface and the interfacial tensions trying to restore its equilibrium. This results in the generation of capillary waves travelling at the gas-water interface of the plastron, therefore referred to in this study as plastronic waves. A video recording can be found in SI (Movie 1). In the exemplary case of Fig. 1f, TAM ≅ 160 μs, and the signal duration is thus 3TAM ≅ 480 μs. Three cycles of AM appeared to be a good compromise of duration considering that a longer excitation may result in interference phenomena of the interfacial waves due to reflection from the outer boundary of the superhydrophobic sample. On the other hand, a shorter excitation did not allow the generation of enough wavefronts to provide a sensitive detection of the wave properties, such as phase speed, wavelength, frequency, and attenuation ratio, in the employed optical arrangement. The details of the generation process of the plastronic waves is outlined in the following.

The time instant t = 0 μs corresponds to the moment, when the generation of a single AM US pulse y(t) is initiated. Because the HIFU transducer’s focusing shape has a nominal 50 mm radius of curvature, the acoustic perturbation has to propagate from the transducer for about 34 μs, theoretically, before it reaches the gas-water interface of the plastron, placed at the acoustic focus of the transducer. This estimation considers a speed of sound in water =1490 m s−1 at 25 °C. When the US pulse should have started to impact the plastron, a pattern of concentric circles emerges from stillness. The optical contrast reaches a maximum around time t = 82 μs, as illustrated in the first snapshot in Fig. 1f. In this exemplary case, 82 μs approximately equals 34 μs + TAM/4 = 74 μs, which should temporally correspond to the first maximum of AM, and, therefore, to a maximum of acoustic energy. The bright areas of this pattern spatially correlate with the experimentally measured locations of both the acoustic focus and the first side lobe, the latter located at a radial distance r ≅ 0.8 mm from the acoustic epicentre, as shown in Fig. 1e and labelled in Fig. 1f. It can therefore be deduced that brighter and darker areas respectively transcribe troughs (inward excursion, i.e., towards the gas phase) and crests (outward excursion, i.e., towards the water) of the gas-water interface, producing a pattern of optical refraction, i.e., the consequence of transmitted light bending due to the deformation of the gas-water interface. This is further confirmed and elaborated thanks to a side-view demonstration of plastron deformation performed in a superhydrophobic micro-channel, as discussed in Section 1.A of the SI and illustrated with experimental images in Fig. S3.

In Fig. 1d, the frequency of the plastronic waves is studied as a function of the signal AM frequency. When the latter varies in the range 4.8−6.3 kHz, the frequency of the plastronic waves varies in the range 9.5−12.1 kHz. A ratio 2:1 of the wave frequency to the AM frequency is thus repeatedly observed. This is true for any micropillar geometry, as shown in Fig. S4, confirming that the AM ARF poking the plastron with periodicity TAM/2 is the driving mechanism of the plastronic waves. The determination of the range of AM frequencies employed for each microstructure geometry results from experimentation on the plastron response to a short US pulse (50 cycles, 2.5 MHz), which is further documented in SI, Section 1.A, and illustrated in Fig. S5–7.

Influence of constraints and edges on the wave characteristics

With constant pillar height (h = 53 μm), we tune the interface three-phase contact density by employing various pillar spacings s: 15, 20, 25, 35, 45, 55 and 65 μm. The dispersion relation of the produced plastronic waves is illustrated in Fig. 2a. All these wavenumber-to-frequency linear relations have a non-zero, positive y-intercept, meaning that dispersion occurs. This is confirmed on the graph by exemplary values of the ratio Ω/k, which varies with respect to k. The dependence of the slope on pillar spacing suggests that the dispersion relation of the plastronic waves can be modulated by varying the pillar spacing and, thus, the density of the three-phase contact line.

a The dispersion relation of the plastronic waves with respect to the inter-pillar spacing s, with fixed pillar height h = 53 μm. Exemplary values of the ratio Ω/k (i.e., the phase speed), indicated in orange on the plot, confirm the dispersive behaviour, emphasising as the pillar spacing decreases. b The phase speed as a function of the pillar spacing, with fixed pillar height h = 53 μm, all wavelengths combined. The comparison of experimental measurements is done with the theoretical phase speed of conventional (unconstrained) deep water waves (λ = 1 mm) and with the semi-empirical model of Scott and Benjamin12, defined in Eq. (2). This model, which describes the phase speed of an interfacial wave travelling in a deep water-filled channel as a function of the wall spacing bc, plotted here for different wavelengths, shows a good agreement with the experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The phase speed of plastronic waves grows with increasing wavelength, which is more obvious in Fig. 2b. This contradicts with the behaviour of conventional deep water capillary waves, as shown in SI, Fig. S1. Another contrasting feature of the plastronic waves is that they travel considerably faster than deep water waves, as computed from Eq. (1), for λ = 1 mm. This represents a speed-up factor of up to 45, which seems to be facilitated by the plastron configuration. Among all our experiments, the highest phase speed achieved is 22.5 m s−1, which is experienced by a 13.1 kHz plastronic wave with wavelength 1.7 mm, in the case of the smallest pillar spacing s = 15 μm (h = 53 μm).

Figure 2b also depicts the semi-empirical model of Scott and Benjamin12, which describes the phase speed cp of an interfacial wave travelling in a deep water-filled channel, as follows

where hc and bc are the wall height and spacing. The stiffness of the interface, augmented by its pinning to the solid structures, grows with the narrowing of the space between them, and thus with the density of edge constraints10. Equivalently, decreasing the spacing between the micropillars will make the interface appearing stiffer from the perspective of the propagating wave, and thus is anticipated to increase the wave speed, which is confirmed by Fig. 2b. For the largest spacing, the phase speed of the plastronic waves approaches that of conventional waves in deep water, as it should occur with the removal of constraints11. These experimental results are in line with the properties of capillary waves in water-filled channel, for which the propagation speed decreases with the broadening of the channel in which they travel10,12. Although the model of Scott and Benjamin focuses on centimetre-scale water waves with wave speed not exceeding 2 m s −1 12, it was here computed for a range of wavelengths (λ = 0.5, 0.8, 1.1, and 1.4 mm) comparable with the ones of our experimental data. The parallel with the plastronic waves is striking.

Influence of the pillar height on the wave characteristics

With constant pillar spacing (s = 25 μm), we now investigate the wave behaviour with respect to the pillar height h: 21, 25, 37, 53 or 71 μm. The dispersion relation in Fig. 3a facilitates the comparison at a given wavenumber between the plastronic waves and the conventional deep water capillary waves, again computed from Eq. (1). The angular frequency of plastronic waves is higher than that of conventional waves and seems to be weakly dependent on the pillar height. In Fig. 3b, for a given wavelength (i.e., a given plotting colour), the phase speed evidences a quadratic-like relation with downward curve and a local maximum around h = 37 μm. Below and above this pivotal value of pillar height, a drop in phase speed is typically observed, suggesting undemonstrated mechanisms for slowing down the wave propagation.

a The dispersion relation of the plastronic waves differs considerably from that of conventional deep water capillary waves with similar wavenumber. b The quadratic-like relation between the phase speed and the pillar height possesses a local maximum at h = 37 μm with decreasing speed below and above this pivotal value of pillar height. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In the context of ocean waves, the slowing down of shallow water waves with the thinning of the water depth is a known phenomenon. It has been repeatedly suggested by Lamb7, Walbridge and Woodward11 and Gjevik38, that the phase velocity of an interfacial wave travelling on a medium’s interface is weakly influenced by its viscosity, except, when the medium’s depth approaches the thickness of the thin layer of viscous-dominated fluid forming close to the solid boundary. The experimental implementation of their analytical description confirmed that the motion of the water molecules driven by the swelling interface can be slowed down by this so-called viscous boundary layer, through fluid deceleration due to viscous shear stresses. An analogous force in the case of air is expected to be present, but considerably smaller, since air is about 50 times less viscous than water39. In the frequency range 9.5−12.1 kHz of the plastronic waves studied as a function of the pillar height, the viscous boundary layer associated to a wave perturbation in air (kinematic viscosity ν ≅ 15.6 × 10−6 m2 s−1, at 25 °C) has a thickness \(\delta=\sqrt{\nu /\pi f}\)11 ≅ 21.5 ± 1.3 μm. Because the smallest pillar heights (h = 21 and 25 μm) investigated in this work are such that δ ≅ h, the slowing down of the plastronic waves due to viscous effects as the plastron gets thinner cannot be excluded as a participating mechanism influencing the wave characteristics.

All considered, this local maximum formed around 37 μm suggests that more than one mechanism compete. Nevertheless, as the physics of the exposed wave phenomena is not predicted by the existing theory, developing a new model of interfacial wave propagation emulating these experimental conditions is necessary to thoroughly explain the behaviour of the plastronic waves.

Plastronic waves as a monitoring tool for plastron longevity and stability

After all, we can affirm that plastronic waves carry the properties of the plastron under investigation. Assuming the phase speed known for a given microstructured design of superhydrophobic surface, a shift of that value would be an evidence of variation in shape, volume or internal pressure of the plastron. Building on this premise, the change in phase speed of the plastronic waves has been monitored over time for a same plastron. For the investigated configuration (h = 53 μm, s = 25 μm), the results are shown in Fig. 4, where the mean value and the standard deviation of the phase speed are depicted as a function of time for two different values of pulse repetition period (PRP), i.e., 5 seconds in Fig. 4a and 20 seconds in Fig. 4b, and for two different conditions of gas concentration of the surrounding water. In a condition of supersaturation of gas in water, as confirmed with pH measurements and dissolved oxygen probing (details in “Methods”), but also with the observation of spontaneous formation of bubbles on the tank walls, a relative downward shift of the phase speed is recorded over time, drifting by 9 ± 5%, after 4 minutes. In a condition of undersaturation of gas in water (degassed), a relative upward shift of the phase speed is recorded over time, drifting by 8.5 ± 4.5% after 4 minutes. The variation of hydrostatic pressure ΔPhyd = 200 ± 10 Pa and water temperature T0 = 25.7 ± 0.4 °C having not significantly changed along these sets of experiments, one can consider that the shift in phase speed reflects the plastron alteration via the gas diffusion from and to the surrounding water. When the water is supersaturated, its outgassing can spontaneously take place, e.g., via outward transfer into the plastron24,40. Subsequently, the plastron inflates, revealed by the observed decrease of the phase speed demonstrated in Fig. 4. In contrast, when the water is undersaturated, the water ingassing spontaneously takes place, e.g., via gas intake from the intra-plastronic gas24,41. Consequently, the plastron is expected to be dissolving, which is transcribed by the gradual increase of the waves phase speed observed in Fig. 4. This happens similarly with other plastron configurations, such as reported in SI for h = 21 μm, in Fig. S8b. With these considerations, the plastronic waves become an interpreter of the plastron changes and stability. The possibility to probe a micrometre scale plastron with a remotely introduced energy in sub-millimetre length scale, i.e., the plastronic waves, can become greatly powerful, when the plastron Cassie-to-Wenzel transition and invasive methods to probe it are not viable options.

The observation of the relative change in the phase speed of plastronic waves with respect to time allows to monitor the gas exchange taking place between the plastron and the water. The plastron is actuated with successive AM pulses y(t) with a given pulse repetition period (PRP). The recording is done over a duration of 4 minutes, for a total of 49 acquisitions in the case of a 5 seconds PRP (a) and 13 acquisitions in the case of a 20 seconds PRP (b). On completion of recording, the relative change in the phase speed significantly differentiates between the two explored configurations, in blue for a gas-undersaturated water and in red for a gas-supersaturated water, revealing the spontaneous dissolution and inflation, respectively, of the superhydrophobic plastron under monitoring. A similar behaviour observed in both cases of PRP indicates that the US actuation and the propagating waves do not accelerate the gas exchange processes. The parameter n refers to the number of repetitions for each experimental configuration. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

A similar shift of phase speed over time for different PRP informs us that the US actuation is not accelerating the gas diffusion, unlike a water flow would23. Instead, the plastronic waves could act as an effective, non-destructive probing sensor, incorporated in an active control system, for plastron regulation and wetting prevention. Considering that a key challenge in maintaining an underwater superhydrophobic surface unwet remains to this date in solutions for preventing a Cassie-to-Wenzel state transition from occurring, this successful utilisation of plastronic waves for monitoring a plastron might open up novel applications in, e.g., on-chip biofilm reactor, micromixing, leaky-wave systems, micro-/soft-robotics, implantable biosensors and microfluidic transport.

Discussion

The marriage of surface engineering and nonlinear focused US (2.5 MHz) allowed us to reveal a novel class of interfacial waves travelling on an underwater thin gas layer in micrometre width scale. We demonstrated that a plastron, i.e., a three-phase construct consisting of a gas layer trapped between the topography of PDMS micropillars immersed in water can, with contribution of surface tension and contact line forces, altogether form a meta-medium that can carry interfacial waves with frequency in the range 3.3−19 kHz and new characteristics, hence the name plastronic wave. High-speed optical microscopy provided means to highlight their extraordinary fast phase speed considerably exceeding that of conventional capillary waves with similar wavelength, as well as their nonlinear relation with the geometry of the microstructures and the gas layer.

To explain the behaviour of the US-induced plastronic waves, the well known complementary case of waves travelling in deep water was considered, but also the literature on waves propagating on constrained interfaces or in the vicinity of a viscous boundary layer. While the impact of increasing density of the three-phase contact line on the wave speed follows known trends12, the quadratic-like association between the phase speed and the pillar height suggests that mechanisms not predicted by previous studies compete in the dispersion relation, at the investigated wave frequencies. Although a tentative analogy was done with the literature on gravity-capillary waves slowing down due to viscous forces11,38, further investigations will be necessary to explain thoroughly the experimental results reported here.

Finally, the usefulness of the US-induced plastronic waves as a non-destructive interpreter of the plastron stability, via the examination of the relative change of their phase speed over time, is also demonstrated. The significance of these observations extends far and wide, appealing to a diverse audience working in applied physics, engineering, meta-materials, surface coatings, microfluidics, lab-on-a-chip and biomedical applications.

Methods

Microfabrication

For the microfabrication of the superhydrophobic samples, PDMS was selected for its optical transparency and compatibility with soft lithography method. Each sample consists of an array of cylindrical micropillars of constant diameter (20 μm), arranged in a square lattice, spread across an area of 5 mm × 5 mm enclosed in a 50 μm thick wall. Two series of samples differentiating by their varying parameter were fabricated. In the first series, the varying parameter was the pillar height, equalling 21, 25, 37, 53, and 71 μm, while keeping constant the pillar spacing (25 μm). In the second series, the varying parameter was the pillar spacing, equalling 15, 20, 25, 35, 45, 55 and 65 μm, while keeping constant the pillar height (53 μm). For more details, refer to SI, Section 1.C, Fig. S9 and Table S1.

Experimental setup

As schematised in Fig. 1, a microstructured PDMS sample (manufactured as described in “Microfabrication”) is immersed in pure water (Milli-Q®, 18.2 MΩ cm, 1 ppb total organic carbon), held to a manual 2-axis translation stage (Standa Ltd., 7T175-100, Lithuania) and placed at both the foci of a HIFU transducer (Sonic Concepts™, H-147, central frequency fac = 2.5 MHz, Washington, USA) and a high-speed camera (Vision Research™, Phantom v1612, New Jersey, USA). The visualisation is done in a top-view perspective, through the central opening of the transducer, with a ×5 magnification objective (Canon Inc., MP-E 65 mm, Japan), resulting in an image scaling of 5.7 μm pixel−1. When the sample is submerged in the water, air remains trapped between the microstructures, thanks to the interfacial tensions taking place at the three-phase boundaries, forming then a plastron. The transducer is facing the microstructured side of the sample and thus the tips of the micropillars. A controlled diving speed of <10 mm s−1 assures us of a reproducible thickness of the plastron42. In addition to that, a constant immersion depth (5.6 ± 1.2 cm) of the sample allows to replicate the hydrostatic pressure. Once immersed, an amplitude-modulated US pulse (driving frequency 2.5 MHz, 3 cycles of AM, 0.5 V amplitude input voltage) is generated by an arbitrary function generator (B&K Precision, 4053b, California, USA) and then amplified 50× by a high voltage amplifier (Falco Systems B.V., WMA-300, Netherlands). The produced axisymmetric acoustic field was measured at the focal plane using a needle hydrophone (Precision Acoustics Ltd., 0.2 mm, England). The mechanical interaction between the US pulse and the superhydrophobic surface is recorded at high speed (159090 Hz, 384 × 176 pixels frame size, 357 ns exposure time and 80,000 exposure index), via the software Phantom Camera Control (Phantom®, version 3.4, New Jersey, USA). The synchronisation between the signal generator and the video acquisition is so that the time τ = 0.5 μs (pulse generation delay, as set in the signal generator) always corresponds to the instant at which the US pulse is initiated. It should be noted that each experimental iteration is conducted with a new, fresh superhydrophobic surface, so that every experiments meet the same initial conditions.

The geometrical and acoustic properties of the HIFU transducer, as described by the manufacturer, are given in what follows. The transducer with central frequency 2.5 MHz has an outer diameter of 60 mm and an inner diameter (central opening) of 22.6 mm. The curvature radius at radiating surface is 50 mm, and the focal depth is 39 mm. The pressure focal gain is 91.17, assuming 1 at the radiating surface and in a linear homogeneous field. The focal width and length at half-amplitude (−6 dB) equal 0.51 mm and 3.28 mm.

Tuning of gas concentration of water

In the run of experiments evaluating the impact of gas concentration on the rate of gas diffusion from and to the plastron, via the continuous analysis of US-induced plastronic waves, the Milli-Q water was degassed with a vacuum system (Vacuum Chambers, 2RS-3, Poland) and then carbonated by the means of a sparkling water device (SodaStream International Ltd., Jet™, Israel). Calibrated pH metre (Mettler Toledo™, Seven Compact, Switzerland) and dissolved oxygen metre (Milwaukee Instruments Inc., MW600, North Carolina, USA) were employed to measure the concentration Co of carbon dioxide and the concentration Do of dissolved oxygen present in the Milli-Q water throughout the experimental runs. Based on the pH measurement, the concentration Co is calculated from the expression Co = 10−2.pH/Ka1, where Ka1 is the first constant for dissociation of carbonic acid H2CO3 in water43. Our gas-supersatured water had a CO2 concentration ranging between Co = 153 ± 89 μM (pH = 5.09 ± 0.1) and Co = 304 ± 178 μM (pH = 4.94 ± 0.1), and a concentration Do in the range 3.1−3.2 ± 0.1 mg L−1. For the undersaturation experiment, the water was placed for 15 minutes in the vacuum system for depressurisation (−0.98 ± 0.01 bar). After degassing, the CO2 concentration ranged between Co = 7.3 ± 8 μM (pH = 5.75 ± 0.1) and Co = 15.3 ± 9 μM (pH = 5.59 ± 0.1). The concentration Do was in the range 2.8−3.2 ± 0.1 mg L−1. If the gas concentrations happened to be significantly below or above these concentrations, the plastron was quickly (<4 minutes) experiencing, respectively, collapse or depinning. An example of such depinning event is depicted in SI Fig. S8a. As the intra-plastronic gas volume and pressure increase, so does the Laplace pressure. When the interfacial tensions cannot hold the bulging interface, the gas-water interface detaches (i.e., depinning) from the micropillar tips and a tethered bubble forms, as presented in more detail in a recent work44.

While Do was on the same order of magnitude for both investigated configurations of gas concentration, Co significantly differed. This confirms that the concentration of carbon dioxide in the water, as investigated here, was the parameter driving the spontaneous ingassing and outgassing of the plastron. While the results presented in Fig. 4 were produced with h = 53 μm, another set of experiments conducted with h = 21 μm and with the same experimental conditions led to similar results, as illustrated in SI Fig. S8b. More details are provided in SI, Section 1.D.

Image analysis

The phase speed cp, wavelength λ, frequency f and attenuation ratio α of the US-generated waves result from the analysis of the wavefronts, i.e., the wave lines of same phase, performed in a polar coordinate system, with an home-made Matlab routine. A brief description of the method is given here, and supplemented in SI by details in Figs. S10 and S11, commented in Section 1.E.

The conversion of the high-speed video information into a polar coordinate system, the origin being the image-detected centre of the acoustic actuation, allowed to display the waves into a time vs. radial distance arrangement, as exemplified in Fig. S10. After a detection of the wavefronts, the wave speed cp is evaluated, based on the slope. Then, the wave period T is obtained by computing the average time spacing between wavefronts with same phase, as shown in Fig. S11. Eventually, the wavelength λ and the wave frequency f are such that f = 1/T and λ = cp/f.

Data availability

The raw data generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo database under accession code https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14393997. An exemplary script (Supplementary Data 1) and its associated video file (Supplementary Data 2) for wavefronts analysis are provided as Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Additional custom algorithms are available upon request.

References

Bostock, J. & Riley, H. T. Pliny the Elder: Naturalis Historia, trans. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.56616 (London, H. G. Bohn, 1855–1857).

Russell, J. S. Report on waves. In: Report of the Fourteenth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. John Murray, London (1844)

Airy, G. B. On tides and waves. Encyclopedia metropolitana, vol. 5, p. 289. Dover Publications, London (1841)

Stokes, G. G. On the theory of oscillatory waves. Trans. Camb. Philos. Soc. 8, 441–455 (1847).

Michell, J. H. On the highest waves in water. Philos. Mag. 36, 430–437 (1893).

Crapper, G. D. An exact solution for progressive capillary waves of arbitrary amplitude. J. Fluid Mech. 2, 532–540 (1957).

Lamb, H. Hydrodynamics. (University Press, Cambridge, 1895).

Gerstner, F. Theorie der wellen. Ann. der Phys. 32, 412–445 (1809).

Longuet-Higgins, M. S. & Stewart, R. W. Radiation stresses in water waves; a physical discussion, with applications. Deep Sea Res. Oceanogr. Abstr. 11, 529–562 (1964).

Monsalve, E., Maurel, A., Pagneux, V. & Petitjeans, P. Space-time resolved measurements of the effect of pinned contact line on the dispersion relation of water waves. Phys. Rev. Fluids 7, 014802 (2022).

Walbridge, N. L. & Woodward, L. A. Phase velocity of surface capillary-gravity waves. Phys. Fluids 13, 2461 (1970).

Scott, J. C. & Benjamin, T. B. Waves in narrow channels: faster capillary waves. Nature 276, 803–805 (1978).

Shankar, P. N. Frequencies of gravity-capillary waves on highly curved interfaces with edge constraints. Fluid Dyn. Res. 39, 457–474 (2007).

Heckerman, D., Garrett, S., Williams, G. A. & Weidman, P. Surface tension restoring forces on gravity waves in narrow channels. Phys. Fluids 22, 2270–2276 (1979).

Carbone, G. & Mangialardi, L. Hydrophobic properties of a wavy rough substrate. Eur. Phys. J. E Soft Matter 16, 67–76 (2005).

Barthlott, W. et al. The salvinia paradox: superhydrophobic surfaces with hydrophilic pins for air retention under water. Adv. Mater. 22, 2325–2328 (2010).

Parsons, M. C. Respiratory significance of the thoracicand abdominal morphology of the three aquatic bugs ambrysus, notonecta and hesperocorixa(insecta, heteroptera). Z. für. Morpho. Ökologie Tiere 66, 242–298 (1970).

Bormashenko, E., Musin, A., Whyman, G. & Zinigrad, M. Wetting transitions and depinning of the triple line. Langmuir 28, 3460–3464 (2012).

Drelich, J. & Marmur, A. Physics and applications of superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic surfaces and coatings. Surf. Innov. 2, 211–227 (2014).

Manoharan, K. & Bhattacharya, S. Superhydrophobic surfaces review: functional application, fabrication techniques and limitations. J. Micromanuf. 2, 59–78 (2019).

Mehanna, Y. A. et al. The challenges, achievements and applications of submersible superhydrophobic materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 6569–6612 (2021).

Cassie, A. B. D. & Baxter, S. Wettability of porous surfaces. Trans. Faraday Soc. 40, 546–551 (1944).

Samaha, M. A., Tafreshi, H. V. & Gad-el-Hak, M. Influence of flow on longevity of superhydrophobic coatings. Langmuir 28, 9759–9766 (2012).

Hokmabad, B.V. & Ghaemi, S. Effect of flow and particle-plastron collision on the longevity of superhydrophobicity. Sci. Rep. 7, 41448 (2017).

Wenzel, R. N. Resistance of solid surfaces to wetting by water. Ind. Eng. Chem. 28, 988–994 (1936).

Wong, W. S. Y. & Vollmer, D. Effervescence-inspired self-healing plastrons for long-term immersion stability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2107831 (2021).

Bobji, M. S., Kumar, S. V., Asthana, A. & Govardhan, R. N. Underwater sustainability of the cassie state of wetting. Langmuir 25, 12120–12126 (2009).

Verho, T. et al. Reversible switching between superhydrophobic states on a hierarchically structured surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10210–10213 (2012).

Kung, C. H., Sow, P. K., Zahiri, B. & Mérida, W. Assessment and interpretation of surface wettability based on sessile droplet contact angle measurement: challenges and opportunities. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 6, 1900839 (2019).

Saad, N. et al. Characterization of the state of a droplet on a micro-textured silicon wafer using ultrasound. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 104908 (2012).

Bussonnière, A., Liu, Q. C. & Tsai, P. A. Acoustic responses of underwater superhydrophobic surfaces subjected to an intense pulse. J. Fluid Mech. 956, https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2023.61 (2023).

Giammarinaro, B. et al. Seismic surface wave focal spot imaging: numerical resolution experiments. Geophys. J. Int. 232, 201–222 (2022).

Laloy-Borgna, G., Zorgani, A. & Catheline, S. Micro-elastography: toward ultrasonic shear waves in soft solids. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 113701 (2021).

Krutyansky, L., Brysev, A., Zoueshtiagh, F., Pernod, P. & Makalkin, D. Measurements of interfacial tension coefficient using excitation of progressive capillary waves by radiation pressure of ultrasound in microgravity. Microgravity Sci. Technol. 31, 723–732 (2019).

Lucassen-Reynders, E. H. & Lucassen, J. Properties of capillary waves. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2, 347–395 (1970).

Chu, B.-T. & Apfel, R. E. Acoustic radiation pressure produced by a beam of sound. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 72, 1673–1687 (1982).

Bartolo, D. et al. Bouncing or sticky droplets: Impalement transitions on superhydrophobic micropatterned surfaces. Europhys. Lett. 74, 299–305 (2006).

Gjevik, B. Comments on phase velocity of surface capillary– waves. Phys. Fluids 15, 368–370 (1972).

Abernathy, F. H. Film notes for fundamentals of boundary layers. National Committee for Fluid Mechanics Films 21623 https://web.mit.edu/hml/ncfmf/10FBL.pdf (1970).

Vakarelski, I. U., Chan, D. Y. C., Marston, J. O. & Thoroddsen, S. T. Dynamic air layer on textured superhydrophobic surfaces. Langmuir 29, 11074–11081 (2013).

Jones, P. R. et al. Sustaining dry surfaces under water. Sci. Rep. 5, 12311 (2015).

de Maleprade, H., Clanet, C. & Quéré, D. Spreading of bubbles after contacting the lower side of an aerophilic slide immersed in water. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 094501 (2016).

Backholm, M. et al. Toward vanishing droplet friction on repellent surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2315214121 (2024).

Drago-González, A. et al. Ultrasonic healing of plastrons. Adv. Sci. 11, e2403028 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Research Council of Finland for funding this research via grant agreements No. 342169 (R.H.A.R.) and 342170 (H.J.N.), and via the Centre of Excellence Programme 2022-2029, in Life-Inspired Hybrid Materials (LIBER), project number 346109 (R.H.A.R.). W.S.Y.W. acknowledges the funding support from the Research Council of Finland as well, grant agreement No. 13347247, and also from the European Union’s HORIZON research and innovation program under Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 101062409. M.F. acknowledges the Finnish Cultural Foundation (grant No. 240398). All colleagues from the Medical Ultrasonics Laboratory and the Soft Matter and Wetting group are warmly thanked for their constructive criticism and suggestions. Professor Anton Kuzyk and his team are acknowledged for the provision of their Milli-Q water system and for the access to their pH measuring system. Professor Matilda Backholm is acknowledged for her support through the provision of the carbonation system and the guidance with CO2 measurement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.K. and W.S.Y.W. designed and fabricated the superhydrophobic samples. M.F. set up and conducted the experiments. M.F. produced and analysed the raw data. All authors, M.F., B.K., A.D.G., W.S.Y.W., R.H.A.R. and H.J.N., participated in the interpretation of the results. M.F. wrote the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the submitted version. H.J.N. and R.H.A.R. planned and supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Adrien Bussonnière, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fauconnier, M., Karunakaran, B., Drago-González, A. et al. Fast capillary waves on an underwater superhydrophobic surface. Nat Commun 16, 1568 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55907-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55907-w