Abstract

Separation of multi-component mixtures in an energy-efficient manner has important practical impact in chemical industry but is highly challenging. Especially, targeted simultaneous removal of multiple impurities to purify the desired product in one-step separation process is an extremely difficult task. We introduced a pore integration strategy of modularizing ordered pore structures with specific functions for on-demand assembly to deal with complex multi-component separation systems, which are unattainable by each individual pore. As a proof of concept, two ultramicroporous nanocrystals (one for C2H2-selective and the other for CO2-selective) as the shell pores were respectively grown on a C2H6-selective ordered porous material as the core pore. Both of the respective pore-integrated materials show excellent one-step ethylene production performance in dynamic breakthrough separation experiments of C2H2/C2H4/C2H6 and CO2/C2H4/C2H6 gas mixture, and even better than that from traditional tandem-packing processes originated from the optimized mass/heat transfer. Thermodynamic and dynamic simulation results explained that the pre-designed pore modules can perform specific target functions independently in the pore-integrated materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adsorptive separation is emerging as one of the most effective energy-saving approaches to upgrade the traditional separation processes, as it does not involve the phase transition process1. The key to implementing the adsorptive separation technology is to develop highly efficient adsorbents. Compared to traditional porous materials, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), or porous coordination polymers, or metal organic materials with ordered porous structures and outstanding designability, have shown great potential for application of adsorptive separation2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Ordered pore environments with pre-designed adsorption sites in MOF can realize directional recognition of specific molecules, but usually works for binary mixture systems18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Nevertheless, whether in nature or industrial manufacture, the separation of the realistic mixture is complex and diverse26,27,28,29,30. For example, in the purification process of ethylene, it is necessary to deal with impurities with very similar physicochemical properties, such as ethane, acetylene, and carbon dioxide31,32.

One-step separation of multi-component impurities by a single adsorbent is an ideal separation approach33,34,35,36,37,38,39, but such adsorbents are usually difficult to design. The primary cause is the great challenge of on-demand modular assembly with multiple types of adsorption site or pore channels into single crystalline network (i.e., MOF or other porous matrix). In industry, multi-component mixtures are usually separated by tandem packing of several adsorbents, but this will lead to inscrutable mass/heat transfer and adverse packing process (e.g., the physical mixing of adsorbents at the interface).

Aiming at the above problems, chemical integration of two or more different ordered pores could be a more feasible way, even if such a strategy has not yet been used in multi-component gas separations. Integrating different ordered porous materials can be realized by direct chemical compositing40 or buffer-layer assisted method41,42, though a certain prerequisite has to be met (i.e., unit cell matching in epitaxy growth of core-shell MOF, exquisite control of synthetic condition). Thus, we envision that such a pore integrated material with multiple pore characteristics should be multi-functional while avoiding various disadvantages caused by tandem packing. Therefore, according to the purification requirements, the pores can be modularly assembled, achieving the efficient separation of multi-component mixtures in one single adsorption step (Fig. 1).

Blue and yellow ball are the impurity A and B, red ball is the target product molecule, the blue framework presents core MOF which has the specific pore sturcture for impurity A removal, the yellow framework presents shell MOF which has the specific pore sturcture for impurity B removal. When the mixed gas passes through the PIS material, the core MOF and shell MOF can cooperate to remove the impurity A and B, obtain the target product molecule by one step.

Concerning requirements of the multi-component gas purification process, we developed a pore integration strategy (PIS) to address two challenging ternary gas mixture systems. Herein, two ultramicroporous porous materials TIFSIX-2-Cu-i43 ([(Cu(dpa)2(TiF6)]), dpa = 1,2-bis(4-pyridyl)acetylene), SIFSIX-3-Ni2,43 ([(Ni(pyrazine)2SiF6)n]) with ultra-selective adsorption to C2H2 or CO2, were effectively grown onto the crystal surface of another ordered one with suitable pore size and polar pore surface for potentially strong C2H6 adsorption (Zn-datz-ipa44, [Zn2(datz)2(ipa)]·DMF, Hdatz = 3,5-diamino-1,2,4-triazole, H2ipa = isophthalic acid) under the assistance of dense oxygen anchor in middle SiO2 layer (Fig. 2a), respectively. In addition to selectivity, the ease to synthesis and the controllable morphology of the samples are also key factor for selecting these MOFs.The resultant materials (Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i and Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@SIFSIX-3-Ni) with the integrated pore can effectively capture both impurities from C2H4 in dynamic breakthrough experiments of ternary C2H2/C2H4/C2H6 and CO2/C2H4/C2H6 gas mixtures, respectively. The thermodynamic and dynamic adsorption preference in Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i was also validated by molecular simulation of first adsorption site at the equilibrium-state and dynamic selective adsorption behavior in the integrated pores. Such a PIS to address the simultaneous removal of multiple impurities in a single separation step can be potentially utilized to a wide range of multi-component gas separation processes of industrial interest.

a Synthetic route of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i. b SEM image of Zn-datz-ipa nanoparticle. c left: SEM images of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2 nanoparticle, right upper: TEM images of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2 nanoparticle, right lower: the corresponding elemental mappings for Si (red) and Zn (light blue) elements. d left: SEM images of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, right upper: TEM images of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i nanoparticle, right lower: the corresponding elemental mappings for Cu (orange) and Zn (light blue) elements. e PXRD patterns of Zn-datz-ipa (red line), TIFSIX-2-Cu-i (blue line) and Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i (yellow line), insert: the detail PXRD information of Zn-datz-ipa (star), TIFSIX-2-Cu-i (circle) and Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i.

Results

Synthesis and characteristics of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i

Considering the similarity of the two separation systems, the more challenging C2H2/C2H4/C2H6 separation system was selected as the typical discussion in the main text. The corresponding data and analysis of CO2/C2H6/C2H4 separation was listed in supporting information. Zn-datz-ipa nanocrystals with uniform size (ca. 200 nm × 150 nm block) was firstly synthesized according to the reported procedure with a little modification44 (Fig. 2b and Fig. S1). The purity and porosity were confirmed by the powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) pattern and 77 K N2 adsorption (Figs. 2e and 3a). Due to the relatively polar pore surface and suitable pore size in Zn-datz-ipa, C2H6 demonstrates the largest uptake at low pressure of <10 kPa and strongest adsorption energy, followed by C2H4, and then for C2H2. The selective adsorption for C2H6 over C2H2 and C2H4 affords Zn-datz-ipa to be a good candidate for C2H6 removal from ternary gas mixture in the following pore integrated material. Thereafter, the amorphous SiO2 was chosen as the intermediate transition layer because its very dense O atoms can act as the anchors for the terminal coordination of following out-layer TIFSIX-2-Cu-i45. Noting that the integrating of two heterostructural MOF with different lattice in a single crystal/particle is very difficult46,47,48,49, and most of the successful examples of core-shell MOF systems reported so far are from the combination between the isostructural MOFs50,51,52,53. The layer of silica shell was subjected to cover the surface of Zn-datz-ipa through the conventional Stöber silica encapsulation process with a little modification54. The characteristic broad diffraction peak of amorphous SiO2 can be observed from 17° to 32° in the PXRD data of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2 (Fig. S2). Scanning electron microscope (SEM), transmission electron microscope (TEM) and energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) mapping images show that the SiO2 layer with thickness of ca. 15 nm grows uniformly on the surface of Zn-datz-ipa but not completely covered (Fig. 2c, Figs. S3–S5). Next, we attempted to in-situ grow TIFSIX-2-Cu-i on the dispersed Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2 particles in methanol. It should be noted that the additive amount of precursors for TIFSIX-2-Cu-i growth greatly affects the uniformly even growth of TIFSIX-2-Cu-i layer on Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2 particles. When the precursors of TIFSIX-2-Cu-i were over dose, TIFSIX-2-Cu-i was inclined to nucleate independently (Fig. S6), while reducing the precursor amount of TIFSIX-2-Cu-i would lead to poor crystallinity and insufficient acetylene adsorption contribution in resultant integrated pore system (Fig. S7). Finally, the uniform core-shell pore-integrated porous material of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i was produced under an optimized feeding Zn/Cu molar ratio of 12.2:1. SEM, TEM and EDS mapping images show that the nano-sized particles of TIFSIX-2-Cu-i evenly cover on the surface of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2 (Fig. 2d, Figs. S8–S10). In contrast, TIFSIX-2-Cu-i grows randomly on/out of Zn-datz-ipa crystals without use of SiO2 buffer-layer (Fig. S11). The PXRD pattern of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i shows that Zn-datz-ipa maintains the structure during the whole synthesis process, and two characteristic diffraction peak of TIFSIX-2-Cu-i can be observed at ca. 9° and ca. 13°, indicating the successful integrating of two ordered porous materials (Fig. 2e). We speculated that SiO2 and core-shell MOFs are formed through coordination bonds, but other hydrogen bond forces cannot be ruled (Figs. S12–S15).The molar ratio of Zn/Cu/Si = 62.0/3.5/1 was obtained by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) (Table S1), giving a formula of [Zn2(datz)2(ipa)]8.9@[SiO2]0.3@[Cu(dpa)2(TiF6)] for Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i. Relatively low content of Si will greatly benefit the gas diffusion through the middle SiO2 layer. Moreover, the generality of such transition layer lattice matching strategy is also successfully applied to prepare two other types of pore integrated materials, UiO-66@SiO2@ZIF-8 and UiO-66@SiO2@MOF-74 (Figs. S16–S25).

a N2 adsorption isotherms at 77 K of Zn-datz-ipa, TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, and Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i (insert graph: SEM images of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i before and after adsorption measurement). Adsorption isotherms of C2H6 (blue circle), C2H4 (red triangle), C2H2 (yellow star) on Zn-datz-ipa (b), TIFSIX-2-Cu-i (c) and Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i (d) at 298 K. (Color code for graph b and c insert: H, white; C, gray; N, light purple; O, red; F, brown; Ti,; Zn, dark brown; Cu, dark red.) e IAST selectivities of C2H6/C2H4 (50/50, v/v, blue bar) and C2H2/C2H4 (50/50, v/v, yellow bar) for Zn-datz-ipa, TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, and Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i at 298 K. f Adsorption kinetic curves of C2H6 for Zn-datz-ipa (red), Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2 (blue), Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i (yellow).

Pure gas adsorption

Microporosity of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i was established by 77 K N2 sorption experiments, which gives a typical type-I characteristic. The pore volume was calculated to be 0.237 cm3 g–1 using the N2 uptake measure at P/P0 = 0.8, which is consistent with the theoretical value (0.239 cm3 g–1) calculated based on the above-mentioned composite formula (Fig. 3a). Such a finding undoubtedly proves that the existence of middle SiO2 layer does not affect the gas diffusion between the core and shell pores. To verify the effectiveness of the PIS for C2 hydrocarbon separation, single-component isotherms of C2H2, C2H4 and C2H6 were also measured at 273 K and 298 K, respectively for Zn-datz-ipa, Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2, TIFSIX-2-Cu-i and Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i (Figs. 3b–d, S26–S30). As expected, the isotherms of as-synthesized TIFSIX-2-Cu-i is highly consistent with the reported result55, following the adsorption uptake sequence at 298 K and 100 kPa of C2H2 (104.4 cm3 g–1) > C2H4 (54.1 cm3 g–1) > C2H6 (47.1 cm3 g–1) and the same adsorption enthalpy (Qst) sequence of C2H2 (48.7 kJ mol−1) > C2H4 (38.1 kJ mol−1) > C2H6 (36.0 kJ mol−1) (Figs. S31 and S32). In contrast, Zn-datz-ipa demonstrate the reverse sequence for these three C2 hydrocarbon adsorption (C2H6 > C2H4 > C2H2), especially at relatively low pressure and 298 K. Specifically, at 10 kPa and 298 K, the C2H6 demonstrates the largest C2H6 uptake (35.9 cm3 g–1), followed by C2H4 (31.7 cm3 g–1), and then for C2H2 (30.1 cm3 g–1), while the sequence was same for adsorption enthalpy (Qst), C2H6 (42.5 kJ mol−1) > C2H4 (37.8 kJ mol–1) > C2H2 (36.7 kJ mol−1) (Figs. S33 and S34). For Zn-data-ipa@SiO2, because of very limited amount of SiO2 and its surface location on porous crystals, the gas adsorption uptake and affinity to three gases is almost unchanged compared with that of Zn-datz-ipa (Figs. S35 and S36). To be noted, for both Zn-datz-ipa and TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, adsorption energy of C2H4 stands in the middle position of C2H2, C2H4 and C2H6, which can be inferred that C2H4 cannot be separated in one step from ternary gas mixture if only one of them is used. Interestingly, gas adsorption of C2H2, C2H4 and C2H6 in Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i has undergone a qualitative change which is particularly obvious in the low-pressure uptake sequence at 10 kPa of C2H2 (33.9 cm3 g–1) > C2H6 (31.5 cm3 g–1) > C2H4 (28.5 cm3 g–1) and Qst sequence of C2H6 (38.4 kJ mol−1) > C2H2 (38.1 kJ mol−1) > C2H4 (36.2 kJ mol−1) (Figs S37 and S38). Regarding to the adsorption uptake and energy, C2H4 all shifts to the lowest position compared to C2H2 and C2H6. The change of adsorption behavior is also reflected in the ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST) selectivity. Both IAST selectivity of C2H6/C2H4 and C2H2/C2H4 in Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i were larger than 1 (Fig. 3e and Figs. S39–S46), manifesting the simultaneously selective adsorption property of C2H2 and C2H6 over C2H4. To further verify the unaffected gas diffusion behavior, the adsorption kinetics of C2 gases were studied at 298 K. For C2H6 with the largest kinetic radius, the diffusional time constants of Zn-datz-ipa, Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2, and Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i were calculated to be 89, 109, and 105 respectively, meaning that the out-layer of TIFSIX-2-Cu-i and middle layer of SiO2 have a negligible effect on the C2H6 diffusion from external environment to internal pore channel of Zn-datz-ipa (Fig. 3f and Figs. S47–S49). Additionally, we synthesized TIFSIX-2-Cu-i@SiO2@Zn-datz-ipa, which has the opposite sequences with Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i (Figs. S50–S53, Table S2). Due to synthesis limitations, the proportion of the shell (Zn-datz-ipa) is relatively small, making it difficult to inverted the C2H4/C2H6 selectivity in the PIS material. (Fig. S54). However, adsorption isotherms at different shell contents reveals that the adsorption enthalpy of the TIFSIX-2-Cu-i@SiO2@Zn-datz-ipa for ethane increases (36.3 kJ mol−1 to 36.6 kJ mol−1) with the content increase of shell MOF Zn-datz-ipa (Figs. S55–S57), which is consistent with our previous experimental observations55. In the thermodynamic driven separation system, the components of the PIS materials worked separately, and the final static adsorption performance should be the accumulation of the adsorption behavior of each MOF in the PIS materials. That is, when the selectivity in the actual separation process is not dominated by the diffusion, the growing sequence of MOFs has a relatively minor impact on their application performance.

Molecular modeling

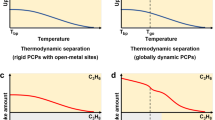

To understand the thermodynamic adsorption differences of three C2 hydrocarbon molecules in Zn-datz-ipa and TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, corresponding host-guest structures were studied by density functional theory (DFT) simulations. In both Zn-datz-ipa and TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, the host-guest interactions are mainly dominated by the hydrogen bonding between C2 hydrocarbons and donor atoms of the framework. For Zn-datz-ipa, gas molecules with more hydrogen atoms can attract more interaction sites with N/O atoms of the framework, thus giving an adsorption energy (Ea) hierarchy of C2H6 (–44.7 kJ mol−1) > C2H4 (–40.7 kJ mol−1) > C2H2 (–37.3 kJ mol−1) (Fig. 4a and Fig. S58), in line with our experimental finding (Fig. S33). For TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, in presence of strong F- site, the Ea follows the order of acidity of guest hydrogen atoms: C2H2 (–45.9 kJ mol−1) > C2H4 (–33.7 kJ mol−1) > C2H6 (–30.9 kJ mol−1) (Fig. 4a and Fig. S59), also consistent with the experimental results in this study and previous report55. To be concluded, Ea vaules of first C2H2 adsorption site in TIFSIX-2-Cu-i and first C2H6 adsorption site in Zn-datz-ipa are all higher than first C2H4 adsorption site in both porous materials. This means the rational combination of these two materials is very likely to capture C2H2 and C2H6 by their strong and specific binding sites, respectively. In order to verify the correctness of DFT simulation method, We have calculated the thermodynamic adsorption preference of C2 gases in the different amount ratio of Zn-datz-ipa/TIFSIX-2-Cu-i in Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i materials (Table S3 and Fig. S60). The results are constant with the single materials. What’s more, in PIS materials, the SiO2 interlayer is non-porous, so its effect on adsorption is negligible. Since the entire core-shell structure is in a loose state, dynamic factors are not affected by the mesoscopic structure of the material in this system. To further investigate the dynamic competitive adsorption among these three adsorbates in integrated pore system of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, molecular dynamic simulations were carried out based on a supercell including 9 unit cells of Zn-datz-ipa, and 4 unit cells of TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, which is very close to the molar ratio in experimental samples of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i. When 50 pairs of each C2 hydrocarbon molecules added into the system, molecular size and polarization played the dominant role at the very beginning as we can find most C2H6 molecules in outer free space at 0.1 ns (Fig. 4b). However, as the elapse of the time, we can easily find that more and more C2H6 molecules were adsorbed in Zn-datz-ipa (from 0 to 36), while more and more C2H2 molecules were adsorbed in TIFSIX-2-Cu-i (from 0 to 26). Notably, the previous adsorbed C2H4 was replaced by following C2H2 and C2H6 when we compared two specific states between 8 ns and 15 ns. Very similar findings were observed in other 7 sets of simulation batches with different proportion of Zn-datz-ipa and TIFSIX-2-Cu-i in such a pore integrated structure model (Figs. S61–S68, Tables S4 and S5). Such a dynamic simulation process implies the highly synergistic cooperation of two ordered pore environment to capture both C2H2 and C2H6 in presence of C2H4.

a First-site adsorption configurations and adsorption energy of C2H2 in TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, C2H6 in Zn-datz-ipa was greater than C2H4 in TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, C2H4 in Zn-datz-ipa respectively (from left to right). b Molecular dynamic snapshots of competitive gas mixture adsorption in Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, displayed as numbers of gas molecules in each part at specific time points. (Color code: H, white; C, brown; N, blue; O, red; F, light blue; Ti, light pink; Zn, gray; Cu, pink.).

Column breakthrough experiments

To investigate the real separation ability of materials under practical conditions, dynamic breakthrough experiments for equimolar ternary gas mixture of C2H2/C2H4/C2H6 at 298 K and ambient pressure were firstly conducted for four sets of separation columns packed by Zn-datz-ipa, TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, physical mixture of these two porous materials and Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i. As shown in Fig. 5a and S70, C2H2, and C2H4 breakthrough first from the Zn-datz-ipa column almost at the same time (41.7 min g–1), while C2H6 was selectively captured and elutes out last at 58 min g–1, which is highly consistent with adsorption isotherms and simulation results (Fig. S71). For TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, C2H2 can be effectively adsorbed by the column, but C2H4 and C2H6 are not well separated (Fig. 5b and Fig. S72). These results further confirm that C2H4 cannot be produced in one step when there is only one single physisorbent of Zn-datz-ipa or TIFSIX-2-Cu-i in the separation column. Next, a physical mixture of Zn-datz-ipa and TIFSIX-2-Cu-i with Zn/Cu molar ratio of 9/1 was packed into the separation column after sufficient grinding. As shown in Fig. 5c, C2H2 (50.8 min g–1) elute out immediately after C2H4 (50.6 min g–1), which is probably caused by relatively low loading of TIFSIX-2-Cu-i compared to Zn-datz-ipa. In other words, relatively low content of TIFSIX-2-Cu-i is impossible to perfectly distribute each diffusion path of gas mixture, so C2H2 passes out quickly without adequate contact with specific C2H2 binding site of TIFSIX-2-Cu-i. When TIFSIX-2-Cu-i amount increased in the physical mixture (i.e., equal mass ratio), C2H6 then becomes the problematic one due to the weakened capture ability and similarly poor spatial distribution in the separation column (Fig. S73). In sharp contrast, PIS-based Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i hold the great promise to address this issue because of the chemically well-integrated pore system in each single particle of the material. The breakthrough result reveals that C2H4 preferentially elutes out at 52.8 min g–1 from the adsorption bed of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i (Fig. 5d), and C2H4 with polymer-grade purity (>99.5%) can be maintained until the C2H2 flow out at 59.2 min g–1 (Fig. S74), giving an excellent C2H4 production capacity of 0.433 mmol g−1. Due to the larger content of Zn-datz-ipa in Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, C2H6 finally flowed out at 64.0 min g–1. In addition, experimental dynamic selectivity of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i was evaluated by online mass spectrometry at different flow rates, and the dynamic selectivity at all four flow rates was consistent with that calculated by IAST (Fig. S75 and Table S8). To further clarify the advantages of PIS, the tandem-packing processes commonly used in industry are also compared. When the TIFSIX-2-Cu-i and Zn-datz-ipa are located in two different columns or tandem-packed in one column, C2H4 can be preferentially eluted from the column, giving productivities (C2H4 purity > 99.5%) of 0.256 mmol g–1 and 0.331 mmol g–1 respectively (Fig. 5d, e). Both values are significantly lower than the productivity of PIS (0.433 mmol g−1), which may be due to the complex mass transfer and thermal effects in the breakthrough. Therefore, the numerical experiments were conducted with Fluent software. It can be seen that the Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i and tandem-packing TIFSIX-2-Cu-i/Zn-datz-ipa have significant difference in mass transfer behaviors and thermal effects. The pressure drop and temperature rise in the two-stage process (60 kPa, 110 K) are obviously higher than that of PIS (15 kPa, 55 K), which should be account for the better C2H4 productivity of PIS (Figs. S76–S79, Tables S9–S12).

Experimental breakthrough curves at 298 K for C2H2/C2H4/C2H6 (1:1:1, total gas flow is 1.5 cm3 min−1) based on (a) Zn-datz-ipa, b TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, c physical mixture of Zn-datz-ipa and TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, d tandem packing of Zn-datz-ipa and TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, e synergistic sorbent separation technology (SSST) with Zn-datz-ipa and TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, and f pore integration strategy (PIS) with Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i. In (a–f), above each figure is the illustration of breakthrough column, the single Zn-datz-ipa column, the single TIFSIX-2-Cu-i column, and the physical mixture column cannot separate the C2H2/C2H4/C2H6 three mixture gases by one step. In e-f, the molar ratio of Zn/Cu is 9/1, the shading part represents the integral area selected for calculating C2H4 productivity. (Color code: H, white; C, brown.).

The promising separation ability for a ternary gas mixture with different molar ratio of C2H2/C2H4/C2H6 (1/90/9) was also achieved (Fig. S80). In addition, all the experimental breakthrough data were validated by the highly consistent dynamic breakthrough simulations (Figs. S81–S83). The well-maintained separation performance was observed after five repeating breakthrough cycles, and the porosity of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i after breakthrough experiments still displays the almost identical value in the 77 K N2 sorption isotherms (Figs. S84–S86).

Universality of the PIS

To verify the universality of PIS, we developed another separation system (CO2/C2H4/C2H6) through the similar synthetic approach. Zn-datz-ipa was also selected as the core MOF, while the CO2-selective SIFSIX-3-Ni was chosen as the shell MOF, yielding Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@SIFSIX-3-Ni with a formula of [Zn2(datz)2(ipa)]0.98@[SiO2]0.033@[Ni(pyrazine)2SiF6]. The purity and porosity of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@SIFSIX-3-Ni were confirmed by PXRD patterns and 77 K N2 isotherm (Figs. S87 and S88). SEM and TEM images showed that the microcrystalline particles of SIFSIX-3-Ni can be uniformly covered on Zn-datz-ipa to form a regular core-shell structure (Figs. S89 and S90). As expected, Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@SIFSIX-3-Ni exhibited stronger CO2 (51.1 kJ mol−1) and C2H6 (42.4 kJ mol−1) than for C2H4 (36.5 kJ mol−1), accounting for the ability to purify C2H4 from the equimolar CO2/C2H4/C2H6 in one step during the breakthrough experiment (Figs. S91–S112). Additionally, to explore the effect of MOF proportion on performance, we modulated the SIFSIX-3-Ni content in Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@SIFSIX-3-Ni by varying reaction duration, leading to an increment in shell-MOF SIFSIX-3-Ni amount over reaction days. PIS materials from 2 days, 2.5 days, and 3 days were assessed, with XRD, TG, and adsorption isotherms detailed in Figs. S113–S115. It can be seen that with the increase of CO2-selected MOF SIFSIX-3-Ni, the CO2 adsorption enthalpy of the PIS samples increased (Fig. S116). Therefore, the PIS strategy allows for performance control of the shell MOF by adjusting the proportion of core-shell MOF. These results further affirm that PIS can provide a simple and efficient modular assembly on demand strategy for the separation of specific multi-component mixtures.

Discussion

PIS based on ordered porous materials with respectively specific binding sites to C2H2, CO2 and C2H6 was demonstrated here for two representative three-component C2H4 separation systems. Porous materials used here for pore-integration, probably can be substituted by other better physisorbents with higher adsorption uptake and/or selectivity to further enhance the overall performance. Such a strategy could be a new solution to fabricate advanced multi-functional physisorbents to tackle with many other complex separation systems in related industry processes.

Methods

General

All reagents were obtained from vendors and used as received without further purification. The crystallinity and phase purity of the samples were measured using PXRD with a Rigaku Mini Flex II X-ray diffractometer employing Cu-Kɑ radiation operated at 40 kV and 15 mA, scanning over the range 5–50° (2ϴ) at a rate of 10° min−1. Thermogravimetry analyses were performed at a rate of 10 °C min−1 under N2 flow using TA Q50 system. The adsorption kinetics were recorded under the target gas atmosphere with a flow rate of 25 cm3 min−1.

Synthesis of TIFSIX-2-Cu-i

An aqueous solution (20 mL) obtained from dissolving 0.8 g (3.3 mmol) of Cu(BF4)2·xH2O and 0.67 g (3.3 mmol) of (NH4)2TiF6 was added into a methanol solution (20 mL) with 0.67 g (6.6 mmol) 4,4’-bipyridylacetylene. This mixture was transferred into a 100 mL borosilicate bottle, and then heated at 80 °C for 24 h. After cooling, the mixture was filtered. The resulting blue-purple powder was exchanged with fresh methanol three times daily for 3 days and then heated to 50 °C under vacuum to finally obtain activated TIFSIX-2-Cu-i.

Synthesis of SIFSIX-3-Ni

437 mg (1.5 mmol) of Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, 269 mg (1.5 mmol) of (NH4)2SiF6, and 240 mg (3 mmol) of pyrazine was added into 3 mL water, stirring the slurry mixture 3 days, a microcrystalline powder in purple was harvested. The suspension mixture was filtered and washed by water and ethanol. Then it was exchanged with fresh ethanol three times daily for 3 days and heated to 100 °C under vacuum to finally obtain activated SIFSIX-3-Ni.

Synthesis of Zn-datz-ipa

A clear solution of 1.487 g (5 mmol) of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O in 10 mL deionized water was added dropwise over another clear DMF/MeOH (40 mL, v/v = 1:1) solution with 0.496 g (5 mmol) Hdatz and 4.153 g (2.5 mmol) H2ipa. The resulting mixture was heated at 130 °C for 72 h, and then cooled to room temperature. The white powder was exchanged with fresh methanol three times daily for 3 days and then heated to 150 °C under vacuum to finally obtain activated Zn-datz-ipa.

Synthesis of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2

1.0 g of as-prepared Zn-datz-ipa were dispersed in 50 mL methanol by ultrasonication for 30 min. 5 mL tetraethyl orthosilicate was added to the above dispersion and stirred for an additional 30 min. Then, 5.0 mL 0.1 M NaOH aqueous solution was added drop wisely over 5 min with a stirring rate of 500 rpm at room temperature. After 24 h stirring, Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2 were collected by centrifugation (8000 rpm in 30 × g, 10 min) and washed with methanol for three times. The white powder was exchanged with fresh methanol three times daily for 3 days and then heated to 150 °C under vacuum to finally obtain activated Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2.

Synthesis of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i

0.2 g of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2 particle was dispersed in methanol by ultrasonication for 30 min. 0.055 mmol mL−1 Cu(BF4)2·xH2O and 0.055 mmol mL−1 (NH4)2TiF6 aqueous solution was added into the above suspension solution. Then 0.11 mmol mL−1 of 4,4’-bipyridylacetylene and 100 μL of triethylamine (TEA) methanol solution was added into the above suspension solution using peristaltic pumps (LSP04-1A, Longer Precision Pump Co., Ltd.) with an injection rate of 20 mL h−1. After string at 80 °C for 24 h, the light blue powder was filtered and washed by menthol for three times. The light blue powder was exchanged with fresh methanol three times daily for 3 days and then heated to 50 °C under vacuum to finally obtain activated Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i.

Synthesis of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@SIFSIX-3-Ni

1.5 mmol Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, 1.5 mmol (NH4)2SiF6, 3 mmol pyrazine, were solved in a 30 mL borosilicate bottle containing 6 mL water and 60 μL of triethylamine (TEA), 0.21 g Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2 particle was dispersed into above suspension solution by ultrasonication for 5 min. Then 1.5 mmol mL−1 of pyrazine aqueous solution was added into the above suspension solution using peristaltic pumps (LSP04-1A, Longer Precision Pump Co., Ltd.) with an injection rate of 6 mL h−1. After string at room temperature for 72 h, the light purple powder was filtered and washed by water and ethanol for three times. Then it was exchanged with fresh ethanol three times daily for 3 days and heated to 100 °C under vacuum to finally obtain activated Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@SIFSIX-3-Ni.

Single-gas sorption experiments

Gas sorption isotherms for N2, C2H6, C2H4, and C2H2 were measured with an automatic volumetric sorption apparatus Micromertics 3FLEX. All the high-purity gases used in the single-gas adsorption experiments were purchased commercially: He (99.999%), N2 (99.999%), C2H2 (99.99%), C2H4 (99.999%), and C2H6 (99.999%). A 4 L Dewar filled with liquid N2 was adopted for control of achievement of 77 K. Precise control of 273 K and 298 K were realized by a Julabo ME (v.2) with a recirculating control system containing a mixture of ethylene glycol and water.

Dynamic gas breakthrough experiments

The Zn-datz-ipa, TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, and Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i breakthrough curves were recorded on a homemade apparatus for C2H6/C2H4/C2H2 gas mixtures at 298 K and 100 kPa. Activated Zn-datz-ipa 4.82 g, TIFSIX-2-Cu-i 4.82 g, Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i 4.82 g were prepared and packed into a stainless-steel column for the C2H6/C2H4/C2H2 (1/1/1, total gas flow of 1.5 cm3 min–1), C2H6/C2H4/C2H2 (90/9/1, total gas flow of 1.5 cm3 min−1) separation experiment. And the outlet gas concentration was monitored by a gas chromatography analyzer (TCD-Thermal Conductivity Detector, detection limit 0.1 ppm). After each breakthrough experiment, Zn-datz-ipa can be regenerated under a He flow of 20 cm3 min−1 at 70 °C for 8 h, TIFSIX-2-Cu-i can be regenerated under a He flow of 20 cm3 min−1 at 50 °C for 8 h, Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i can be regenerated under a He flow of 20 cm3 min−1 at 90 °C for 8 h.

Data availability

All relevant data are provided in this article and its supplementary Information. Source data of the PXRD patterns, TGA curves, sorption tests; gas adsorption enthalpies and selectivities and breakthrough tests that support the findings of this study are provided as a Source Data file (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28075376). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Sholl, D. S. & Lively, R. P. Seven chemical separations to change the world. Nature 532, 435–437 (2018).

Cui, X. L. et al. Pore chemistry and size control in hybrid porous materials for acetylene capture from ethylene. Science 353, 141–144 (2016).

Lin, R. B. et al. Molecular sieving of ethylene from ethane using a rigid metal-organic framework. Nat. Mater. 17, 1128–1133 (2018).

Li, J. R., Kuppler, R. J. & Zhou, H. C. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1477–1504 (2009).

Gu, C. et al. Design and control of gas diffusion process in a nanoporous soft crystal. Science 363, 387–391 (2019).

Liao, P. Q., Huang, N. Y., Zhang, W. X., Zhang, J. P. & Chen, X. M. Controlling guest conformation for efficient purification of butadiene. Science 356, 1193–1196 (2017).

Zeng, H. et al. Orthogonal-array dynamic molecular sieving of propylene/propane mixtures. Nature 595, 542–548 (2021).

Cadiau, A., Adil, K., Bhatt, P. M., Belmabkhout, Y. & Eddaoudi, M. A metal-organic framework–based splitter for separating propylene from propane. Science 353, 137–140 (2016).

Furukawa, H. et al. Ultrahigh porosity in metal-organic frameworks. Science 329, 424–428 (2010).

Banerjee, D. et al. Metal–organic framework with optimally selective xenon adsorption and separation. Nat. Commun. 7, ncomms11831 (2016).

Krause, S. et al. A pressure-amplifying framework material with negative gas adsorption transitions. Nature 532, 348–352 (2016).

Zhai, Q.-G., Bu, X., Mao, C., Zhao, X. & Feng, P. Systematic and dramatic tuning on gas sorption performance in heterometallic metal–organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2524–2527 (2016).

Rieth, A. J. & Dincă, M. Controlled gas uptake in metal–organic frameworks with record ammonia sorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 3461–3466 (2018).

Smith, G. L. et al. Reversible coordinative binding and separation of sulfur dioxide in a robust metal–organic framework with open copper sites. Nat. Mater. 18, 1358–1365 (2019).

Wang, S. et al. Engineering structural dynamics of zirconium metal–organic frameworks based on natural C4 linkers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 17207–17216 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Porous framework materials for energy & environment relevant applications: A systematic review. Green. Energy Environ. 9, 217–310 (2024).

Yang, S. et al. Supramolecular binding and separation of hydrocarbons within a functionalized porous metal–organic framework. Nat. Chem. 7, 121–129 (2015).

Bae, Y.-S. et al. High propene/propane selectivity in isostructural metal–organic frameworks with high densities of open metal sites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 1857–1860 (2012).

Chen, C.-X. et al. Nanospace engineering of metal–organic frameworks through dynamic spacer installation of multifunctionalities for efficient separation of ethane from ethane/ethylene mixtures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 9680–9685 (2021).

Geng, S. et al. Scalable room-temperature synthesis of highly robust ethane-selective metal–organic frameworks for efficient ethylene purification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 8654–8660 (2021).

Dong, Q. et al. Confining water nanotubes in a Cu10O13-Based metal–organic framework for propylene/propane separation with record-high selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 8043–8051 (2023).

Gong, W. et al. Programmed polarizability engineering in a cyclen-based cubic Zr(IV) metal–organic framework to boost Xe/Kr separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 2679–2689 (2023).

Yang, S.-Q. et al. Immobilization of the polar group into an ultramicroporous metal–organic framework enabling benchmark inverse selective CO2/C2H2 separation with record C2H2 production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 13901–13911 (2023).

Zheng, X. et al. Optimized sieving effect for ethanol/water separation by ultramicroporous MOFs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202216710 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Purification of propylene and ethylene by a robust metal–organic framework mediated by host–guest interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 15541–15547 (2021).

Siegelman, R. L. et al. Water enables efficient CO2 capture from natural gas flue emissions in an oxidation-resistant diamine-appended metal-organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 13171–13186 (2019).

Sholl, D. S. & Lively, R. P. Exemplar mixtures for studying complex mixture effects in practical chemical separations. JACS Au 2, 322–327 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. Self-assembled iron-containing mordenite monolith for carbon dioxide sieving. Science 373, 315–320 (2021).

Lin, J.-B. et al. A scalable metal-organic framework as a durable physisorbent for carbon dioxide capture. Science 374, 1464–1469 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Discrimination of xylene isomers in a stacked coordination polymer. Science 377, 335–339 (2022).

Haribal, V. P., Chen, Y., Neal, L. & Li, F. Intensification of ethylene production from naphtha via a redox oxy-cracking scheme: Process simulations and analysis. Engineering 4, 714–721 (2018).

Fakhroleslam, M. & Sadrameli, S. M. Thermal/catalytic cracking of hydrocarbons for the production of olefins; a state-of-the-art review III: Process modeling and simulation. Fuel 252, 553–566 (2019).

Cao, J.-W. et al. One-step ethylene production from a four-component gas mixture by a single physisorbent. Nat. Commun. 12, 6507 (2021).

Dong, Q. et al. Shape-and size-dependent kinetic ethylene sieving from a ternary mixture by a trap-and-flow channel crystal. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2203745 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. One‐step ethylene purification from an acetylene/ethylene/ethane ternary mixture by cyclopentadiene cobalt‐functionalized metal–organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11350–11358 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Guest-molecule-induced self-adaptive pore engineering facilitates purification of ethylene from ternary mixture. Chem 8, 3263–3274 (2022).

Xu, Z. et al. A robust Th-azole framework for highly efficient purification of C2H4 from a C2H4/C2H2/C2H6 mixture. Nat. Commun. 11, 3163 (2020).

Zhang, P. et al. Synergistic binding sites in a hybrid ultramicroporous material for one-step ethylene purification from ternary C2 hydrocarbon mixtures. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn9231 (2022).

Bloch, E. D. et al. Hydrocarbon separations in a metal-organic framework with open Iron(II) coordination sites. Science 335, 1606–1610 (2012).

Zhao T. et al. Emulsion-oriented assembly for Janus double-spherical mesoporous nanoparticles as biological logic gates. Nat. Chem. 15, 832–840 (2023).

Fang, W., Hongliang, W. & Tao, L. Seaming the interfaces between topologically distinct metal–organic frameworks using random copolymer glues. Nanoscale 11, 2121–2125 (2019).

Zhang, M. et al. 3D-agaric like core-shell architecture UiO-66-NH2@ZIF-8 with robust stability for highly efficient REEs recovery. Chem. Eng. J. 386, 124023 (2020).

Chen, K. J. et al. Benchmark C2H2/CO2 and CO2/C2H2 separation by two closely related hybrid ultramicroporous materials. Chem 1, 753–765 (2016).

Chen, K. J. et al. New Zn-aminotriazolate-dicarboxylateframeworks: synthesis, structures, and adsorption properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 13, 2118–2123 (2013).

Li, B., Ma, J. G. & Cheng, P. Silica-protection-assisted encapsulation of Cu2O nanocubes into a metal-organic framework (ZIF-8) to provide a composite catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 6834–6837 (2018).

Feng, L., Lv, X.-L., Yan, T.-H. & Zhou, H.-C. Modular programming of hierarchy and diversity in multivariate polymer/metal-organic framework hybrid composites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 10342–10349 (2019).

Kwon, O. et al. Computer-aided discovery of connected metal-organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 10, 3620 (2019).

Xinyu, Y. et al. One-step synthesis of hybrid core-shell metal-organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 3927–3932 (2018).

Yifan, G. et al. Controllable modular growth of hierarchical MOF-on-MOF architectures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 15658–15662 (2017).

Choi, S., Kim, T., Ji, H., Lee, H. J. & Oh, M. Isotropic and anisotropic growth of metal-organic framework (MOF) on MOF: logical Inference on MOF structure based on growth behavior and morphological feature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 14434–14440 (2016).

Faustini, M. et al. Microfluidic approach toward continuous and ultrafast synthesis of metal-organic framework crystals and hetero structures in confined microdroplets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 14619–14626 (2013).

Jayachandrababu, K. C., Sholl, D. S. & Nair, S. Structural and mechanistic differences in mixed-linker zeolitic imidazolate framework synthesis by solvent assisted linker exchange and de novo routes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 5906–5915 (2017).

Lee, G., Lee, S., Oh, S., Kim, D. & Oh, M. Tip-to-middle anisotropic MOF-On-MOF growth with a structural adjustment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 3042–3049 (2020).

Stöber, W., Fink, A. I. & Bohn, E. Science I. Controlled growth of monodisperse silica spheres in the micron size range. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 26, 62–69 (1968).

Chen, K. J. et al. Synergistic sorbent separation for one-step ethylene purification from a four-component mixture. Science 366, 241–246 (2019).

Acknowledgements

K.J.C., Q.Y.Z., Y.W., H.W. acknowledges the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22071195, 22275148, 22101231, 52176088) and The Youth Innovation Team of Shaanxi Universities. X.J. acknowledges the Natural Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi Province of China (2024JC-YBQN-0106), Shaanxi Fundamental Science Research Project for Chemistry and Biology (Grant No. 23JHQ004), and the Development and Planning Guide Foundation of Xidian University (XJSJ24076). We would like to thank the Analytical & Testing Center of Northwestern Polytechnical University for SEM and TEM testing, respectively. Specially, we gratefully thank Dr. Xiu-Bo Yang at the Analytical & Testing Center of Northwestern Polytechnical University for assistance with the TEM characterization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J.C. and Q.Y.Z. designed the project. X.J., L.C., Y.W., and R.Y. synthesized the compounds. X.J., Y.W., L.C, J.B.W., and J.W.C. collected and analyzed all adsorption data. X.J., Y.W., X.B.Y., S.H.W., and L.C., collected the SEM and TEM pictures. X.J., L.C., and R.Y. collected and analyzed all kinetic adsorption data. H.W. performed the molecular simulations, Adsorption dynamics simulations, and transient breakthrough simulations. D.H.Z. and R.Y.Z. performed the numerical experiments simulations. X.J., L.C., Y.W., and J.W.C. collected and analyzed all experimental breakthrough data. X.J., Y.W., H.W., and K.J.C. wrote the paper, and all authors contributed to revise the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.J.C., X.J., Y.W. and Q.Y.Z. have filed a provisional patent application (no. 2024100086805) regarding the pore integration strategy and application of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i and Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@SIFSIX-3-Ni, data related to synthesis method, adsorption curve, gas adsorption enthalpies, Ideal Adsorbed Solution Theory (IAST) selectivities and breakthrough curve of Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@TIFSIX-2-Cu-i and Zn-datz-ipa@SiO2@SIFSIX-3-Ni. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, X., Wang, Y., Wang, H. et al. Integration of ordered porous materials for targeted three-component gas separation. Nat Commun 16, 694 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55991-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55991-y

This article is cited by

-

Preparation of MOF-74 modified with organic amine and its CO2 adsorption performance

Journal of Materials Science (2025)