Abstract

Childhood obesity poses a significant public health challenge, yet the molecular intricacies underlying its pathobiology remain elusive. Leveraging extensive multi-omics profiling (methylome, miRNome, transcriptome, proteins and metabolites) and a rich phenotypic characterization across two parts of Europe within the population-based Human Early Life Exposome project, we unravel the molecular landscape of childhood obesity and associated metabolic dysfunction. Our integrative analysis uncovers three clusters of children defined by specific multi-omics profiles, one of which characterized not only by higher adiposity but also by a high degree of metabolic complications. This high-risk cluster exhibits a complex interplay across many biological pathways, predominantly underscored by inflammation-related cascades. Further, by incorporating comprehensive information from the environmental risk-scape of the critical pregnancy period, we identify pre-pregnancy body mass index and environmental pollutants like perfluorooctanoate and mercury as important determinants of the high-risk cluster. Overall, our work helps to identify potential risk factors for prevention and intervention strategies early in the life course aimed at mitigating obesity and its long-term health consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Childhood obesity, characterized by high body fat accumulation, is a leading public health threat1. It is estimated that around 1 in every 10 children are currently living with obesity across Europe2. Childhood obesity is difficult to reverse, drives a myriad of metabolic perturbations, and substantially increases the risk of later cardiovascular disease (CVD), an effect known to be, at least partly, mediated by obesity-associated metabolic dysfunction, including dyslipidemia, hyperinsulinemia, and hypertension1,3,4. Nevertheless, the risk of developing obesity-associated comorbid diseases can vary across individuals. It has been shown that not all individuals with obesity develop metabolic dysfunction, a phenomenon referred to as metabolically healthy status, and studies have reported a considerably lower risk for future CVD events and all-cause mortality in those individuals compared to individuals with a metabolically unhealthy status5.

It has been suggested that complex interactions between metabolically active tissues (such as fat, liver, and the skeletal muscle) play a role in the health state of the complex obesity phenotype6,7. Yet, little is known about the molecular architecture underlying the biology behind obesity and metabolic dysfunction. Recent advances in high-throughput technologies have brought forward an accelerated incentive in obesity research, with omics data being key to an in-depth functional understanding of health and disease states. Studies to date have largely focused on adult populations, on the examination of single to two omics layers and on weight-related outcomes with no consideration of other metabolic characteristics8,9,10. This provides little knowledge about the internal molecular environment and the underlying biological pathways early in the development of the multi-faceted obesity phenotype. As highlighted, the tenet of the precision medicine concept in obesity calls for a more holistic approach and a comprehensive multi-omics profiling to better understand this prevalent health condition11,12,13. This can ultimately facilitate assessment of obesity-associated risk and disease progression, and aid towards targeted intervention strategies.

We therefore sought to interrogate multiple blood omics layers and a number of metabolic health outcomes in children to advance our understanding of the pathobiology of obesity, early in disease genesis. Our objective was to offer insights into the diversity of molecular profiles in metabolically healthy and unhealthy individuals. We hypothesized that children at risk for metabolic disease would show broad and aggregated alterations in blood omics analytes, whether as causes or effects of biological changes leading up to the disease. To explore this hypothesis, we leveraged the unique database of the population-based Human Early Life Exposome (HELIX) project14, one of the largest datasets of the general pediatric population with comprehensive multi-omics profiling (five molecular layers) and a rich phenotypic characterization of metabolic health from two regions in Europe.

Motivated by the emerging field of precision environmental health15, we also sought to examine the role of the prenatal environment to provide an additional level of understanding of potential contributors to disease etiology. Prenatal life is a particularly important period to study the environmental triggers of disease; exposures during this developmentally vulnerable period may have pronounced effects at the molecular level and disease risk later in life16. Using a comprehensive approach that incorporates key environmental, social, and lifestyle factors, we aimed to understand how early-life exposures are associated with molecular profiles linked to childhood obesity and metabolic dysfunction.

Overall, this study seeks to expand our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underpinning obesity and associated metabolic dysfunction and to identify modifiable environmental factors that could guide future prevention strategies.

Results

Figure 1 demonstrates our analytic workflow. We analyzed data from the HELIX project, involving children from two parts of Europe: the Northern/Western (N/W) part (study sites: Bradford, UK; Poitiers, France; Kaunas city, Lithuania; and Oslo, Norway) and the Southern/Mediterranean (S/M) part (study sites: Sabadell, Spain; and Heraklion, Greece). Our study population included a total of 863 children (N = 557 from the N/W part and N = 306 from the S/M part).

a We integrated multi-omics data, including DNA methylation, miRNAs, transcript clusters, proteins and metabolites, from childhood blood samples from the HELIX population-based project. We applied similarity network fusion and spectral clustering to derive distinct multi-omics clusters in children from the Northern/Western European part and recapitulated these clusters in children of the Southern/Mediterranean part. b Using generalized regression models, we examined the association of the multi-omics clusters with several metabolic outcomes to characterize the clinical phenotype of each cluster. c We applied machine learning methods to derive SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) values in order to identify the molecular features with high importance in cluster definition and then performed pathway analysis to characterize underlying biological pathways. d We examined how the prenatal environment affects cluster membership. We applied Least Absolute Shrinkage Selection Operator (LASSO) with Stability-enHanced Approaches using Resampling Procedures (SHARP) to identify the most important determinants among several prenatal factors. We then estimated the probability of cluster membership across levels of the identified determinants.

In Table 1, we present characteristics of our study population. The mean (SD) age of children was 7.8 (1.4) years, and a total of 471 children (54.6%) were boys. Children from the N/W cohort were more likely to have mothers with a higher educational level (58.9% vs 35.4%) compared to those from the S/M cohort. These children also had a lower total fat mass (mean (SD) 6.1 (3.7) kg vs. 7.3 (4.2) kg) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels (14 (5.1) U/L vs. 18.1 (6.4) U/L) and were less likely to have overweight/obesity (22.8% vs. 39.2%) than children from the S/M cohort.

Integrative approach to identify multi-omics clusters of children

To derive distinct multi-omics clusters, we applied an integrative network and clustering approach to blood DNA methylation, miRNA expression and gene transcription, plasma protein, and serum metabolite data.

As a first step, we conducted a screening of published literature to identify and select omics molecules related to childhood adiposity measures. This filtering step was performed to: 1) provide much-needed replication of published literature17; and 2) reduce the high dimensionality of the multi-omics dataset, and thus unwanted noise that may dilute clustering signals18,19. Details about the omics biomarkers assessed in HELIX and our search strategy are available in Supplementary Data 1A-C and Supplementary Table 1. A total of 1379 omics features (N = 976 CpG sites, N = 51 miRNAs, N = 219 transcript clusters, N = 35 proteins, and N = 98 endogenous metabolites) were included in the integrated analysis (Supplementary Data 2A-D).

We leveraged the multi-centre nature of the HELIX project and applied first our multi-omics approach in the population of N/W cohort and used the population from the S/M cohort as validation cohort. We computed an affinity matrix for each of the omics datasets and then derived a fused affinity matrix by similarity network fusion (SNF)20. To identify mutually exclusive clusters, we applied spectral clustering to the fused matrix and used the eigengap approach and rotation cost approach to choose the optimal number of clusters. We identified three multi-omics clusters (hereafter referred to as Cluster A, Cluster B, and Cluster C) in the population from the N/W cohort (Supplementary Fig. 1). We subsequently used label propagation, a graph-based semi-supervised method20, to predict the multi-omics clusters (as derived in children from the N/W cohort) in the cohort of children from the S/M cohort. In the N/W cohort, a total of 227 children were included in Cluster A, 150 children in Cluster B, and 180 children in Cluster C. In the S/M cohort, the corresponding numbers of children assigned to each cluster were 238, 21, and 47. We did not observe significant differences by sex, age, study site and ethnicity across the clusters in each part of Europe (Supplementary Table 2).

Metabolic outcomes associated with the multi-omics clusters

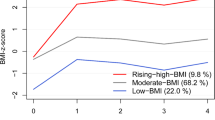

We then examined the association of the multi-omics clusters with metabolic health outcomes to characterize the clinical phenotype of each cluster. In the N/W cohort, we observed that compared to children in Cluster A, children in Cluster C had a higher BMI, higher fat mass, higher waist circumference, lower HDL cholesterol, higher blood pressure, and higher insulin levels (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 3). Notably, in the S/M cohort, we observed a similar pattern of associations with metabolic outcomes for Cluster C. Membership in Cluster C was also found to associate with higher odds of having a metabolically unhealthy status (that is, defined as having at least one metabolic risk factor following consensus pediatric cutoffs)21,22 in both cohorts, as compared to children in Cluster A (N/W cohort: 39.1% vs. 24.5%, adjusted OR 1.96 (95% CI 1.20-3.20); S/M cohort: 52.5% vs. 29.2%, adjusted OR 2.61 (95% CI 1.30-5.21)). For the multi-omics Cluster B, we observed associations mostly with the anthropometric outcomes in N/W cohort. For instance, membership in Cluster B was associated with higher fat mass as compared to membership in Cluster A. A similar association was also observed in the S/M cohort. When we pooled together the two cohort populations (thus better reflecting a pan-European population), we observed more precise and pronounced results, possibly owning to smaller standard errors and higher outcome contrasts. In a post-hoc sensitivity analysis, we examined whether sex had any influence in the observed associations for fat mass and metabolic risk (Supplementary Table 4). We observed no substantial evidence to indicate effect modification by sex, as reflected in the largely overlapping 95% confidence intervals of the sex-specific effect estimates. Overall, our findings suggest potential generalizability of the identified multi-omics clusters, with Cluster C being designated as the “severe cluster” in terms of metabolic health.

a Associations with continuous metabolic health outcomes. Effect estimates and their 95% CIs were derived from generalized linear regression models while controlling for study site, sex, and age at examination. Circles indicate beta coefficients (expressed in SD change) and whiskers indicate 95% CIs. The metabolic syndrome (MetS) score was derived using z-scores for waist circumference, HDL cholesterol level, triglyceride level, insulin level, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Cluster A was the reference category. ALT alanine aminotransferase, BMI body mass index, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HDL high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, SBP systolic blood pressure. b Associations with categorical metabolic health outcomes. Effect estimates and their 95% CIs were derived from logistic regression models while controlling for study site, sex, and age at examination. Circles indicate odds ratios and whiskers indicate 95% CIs. Given the asymmetrical nature of the odds ratio scale, odds ratios are not in the centre of the 95% CIs. Overweight/obesity (Ov/Ob) was defined according to the World Health Organization criteria. Metabolically unhealthy (MetU) status was defined as the presence of at least one of the following risk factors: systolic or diastolic blood pressure ≥90th percentile, insulin ≥90th percentile, HDL cholesterol ≤40 mg/dl, triglycerides ≥110 mg/dl, ALT ≥ 22.1 U/L for females and ≥25.8 U/L for males. Cluster A was the reference category. The number of participants in each multi-omics cluster across cohorts was as follows: N = 227 for Cluster A, N = 150 for Cluster B and N = 180 for Cluster C in the Northern/Western cohort, and N = 238 for Cluster A, N = 21 for Cluster B, and N = 47 for Cluster C in the Southern/Mediterranean cohort. Source data for all panels are provided as a Source Data file.

We then stratified our study population according to weight status to assess the magnitude of the metabolic effects associated with Cluster C separately in children with normal weight and overweight or obesity (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 5). We observed that Cluster C was associated with a poorer metabolic profile in both categories of weight status, with more pronounced associations being observed in children with overweight or obesity. In those children, Cluster C was associated with more than a two-times higher odds of having a metabolically unhealthy status compared to Cluster A (N/W cohort: 47.4% vs. 24.2%, adjusted OR 3.26 (1.10-9.70); S/M cohort: 64% vs. 38.5%, adjusted OR 2.77 (1.08-7.09)).

Finally, in a sub-sample of our initial study population (Ntotal=404; NN/W = 233, NS/M = 171), we had available anthropometric measures assessed in adolescence (mean (SD) age of 14.8 (1.36) years) (Supplementary Table 6). We thus sought to examine whether the identified multi-omics clusters were associated prospectively with obesity-related outcomes. We observed that membership in Cluster C was associated with higher adolescent BMI, waist circumference and fat mass, as opposed to membership in Cluster A (Supplementary Fig. 3). For Cluster B, weaker associations were observed.

Molecular drivers of the multi-omics clusters

Given the clinical relevance of the multi-omics clusters in terms of metabolic health, our biological inquiry focused on identifying the molecular drivers of the clusters (that is, molecular features with high importance in cluster definition), so as to better understand potential underlying biological mechanisms. We applied eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGboost) using a one-cluster-versus-the-rest approach and the multi-omics molecules as predictors. Models’ hyperparameters were tuned in the N/W cohort (training set) and performance was assessed in the S/M cohort (testing set). Our models performed well in correctly predicting cluster membership (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) values > 0.90) in the S/M cohort (Supplementary Table 7).

To understand both the decision-making mechanisms of the models and the impact of the features on each cluster, we calculated SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) values across features which quantify the magnitude of contribution of each feature at the local (individual) level and can be aggregated to provide a global measure of feature importance23. To identify the features with high importance, we selected those that had a mean SHAP value at concordant direction across cohorts and an absolute mean SHAP value within the top quartile in each cohort across all molecular layers (Supplementary Data 3A-B).

miRNAs, gene transcription clusters, and proteins exhibited the highest contribution to the definition of the high-risk Cluster C (Fig. 3a). Specifically, membership to Cluster C was associated with higher levels of 14 miRNAs in blood (including hsa-miR-23a-3p, hsa-miR-130a-3p, hsa-miR-21-5p, hsa-miR-192-5p, hsa-miR-24-3p, hsa−let−7 g − 5p) and altered blood transcription levels of 52 genes (including ACSL1, LRRK2, REST, CCND2, POLR1C, PROK2, S100A8, SPI1, IL1B, FTO) (Supplementary Data 4A and Supplementary Fig. 4). Cluster C was also linked to a distinct proteomic profile characterized by higher circulating levels of HGF, IL-6, TNF-alpha, BAFF, IL1-beta, CRP, IL-8, IL-1RA, and MCP1 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Furthermore, higher blood levels of the branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) valine and two carnitines(C6(C4:1-DC) and C16:1), along with lower levels of the non-essential amino acid glycine and two lysophosphatidylcholines (lysoPCaC18:1 and lysoPCaC18:2), were observed to associate with Cluster C. For Cluster B, miRNAs and gene transcription also exhibited the highest importance (Supplementary Fig. 6). Altered circulating levels of 25 miRNAs and blood transcription levels of 9 genes were associated with membership to Cluster B (Supplementary Data 4B and Supplementary Fig. 7). There was a little crossover with the top features characterizing Cluster C and the direction of association generally differed (Supplementary Fig. 8).

a Global importance of the features contributing to the definition of Cluster C. Mean absolute SHAP values were calculated based on a classifier comparing membership to Cluster C vs. membership to Cluster A or B. We present the top features, defined as those with mean SHAP values at concordant direction across cohorts and mean absolute SHAP values ranking within the top quartile in each cohort. b Integrated pathway analysis at the gene level of the top features contributing to the definition of Cluster C. Significance was tested using hypergeometric tests with a false discovery rate (FDR)-P value threshold of less than 0.05. Enriched pathways with more than or equal to three genes annotated to the top features are presented. The size of the dots is proportional to the number of genes (GeneN). KEGG Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Source data for all panels are provided as a Source Data file.

To obtain a more holistic understanding of the molecular complexity and mechanisms characterizing the multi-omics clusters, we conducted integrated pathway analysis (functional enrichment) at the gene level24. We annotated the top molecular features to genes and then used two public databases (KEGG, Gene Ontology) to enhance the comprehensiveness of our pathway analysis results and mitigate limitations across the use of single databases, such as differences in pathway coverage and data curation methodologies25. We observed that the majority of pathways associated with Cluster C were related to immune system and inflammation (e.g., immune cell differentiation and activation, Toll-like receptor signaling26,27, MAPK signaling, TNF signaling, JAK/STAT signaling28) (FDR-P < 0.05) (Fig. 3b). We also identified pathways related to insulin action in metabolism (e.g., PI3K-Akt signaling29, NF-Kappa B signaling26, AGE-RAGE signaling30, p38 MAPK31,32) (FDR-P < 0.05). Other noteworthy pathways associated with Cluster C included those related to endothelial function (e.g., pathways of vascular endothelial growth factor production and nitric oxide biosynthetic process33,34, HIF-1 signaling35,36) (FDR-P < 0.05). To complement these findings, we integrated the annotated genes with data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) public database37 to identify the human tissues in which these genes are most highly expressed (Supplementary Fig. 9). Several of these genes showed high expression in adipose tissue, liver, skeletal muscle, and pancreas, underscoring the role of these tissues in the metabolic and inflammatory characteristics of Cluster C. Overall, these results suggest a multifaceted involvement of biological mechanisms characterizing the poor metabolic phenotype of Cluster C. For Cluster B, no integrated pathways emerged at FDR-P < 0.05.

Prenatal factors associated with the multi-omics clusters

Finally, we sought to examine how the prenatal environment is associated with cluster membership. We assessed a total of 37 key maternal environmental exposures and characteristics, including exposures from the outdoor environment, blood concentrations of chemical exposures, food group intakes and other social and lifestyle factors in pregnancy (Supplementary Table 8). Building on previous research showing that exposome components and their impact exhibit considerable variability across regions owning to different population characteristics and exposure patterns38,39, we examined associations with the multi-omics clusters separately in the N/W and S/M cohorts. To identify the most important environmental factors, we applied LASSO penalized regression with a stability-enhanced approach using resampling (SHARP)40, which can accommodate correlation among exposures (Supplementary Fig. 10) and enhance result reliability. In the N/W cohort, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and exposure to PFOA emerged as the main factors in LASSO, while in the S/M cohort, maternal mercury exposure was highlighted (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 9). Specifically, higher pre-pregnancy BMI and higher maternal levels of PFOA were found to associate with increased probability of belonging to Cluster C in the N/W cohort (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 10). Moreover, elevated maternal levels of mercury were similarly linked to a greater likelihood of belonging to Cluster C in the S/M cohort (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table 10).

a Selection proportion values of prenatal factors derived from Least Absolute Shrinkage Selection Operator (LASSO) penalized multinomial models using cluster membership as outcome and a stability enhanced approach employing resampling. Dashed lines represent the threshold in selection proportion for which each factor is stably selected or stably excluded. DDE 4,4′dichlorodiphenyl dichloroethylene, HCB hexachlorobenzene, NDVI average Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, NO2 nitrogen dioxide, PCB polychlorinated biphenyl, PFHxS perfluorohexane sulfonate, PFNA perfluorononanoate, PFOA perfluorooctanoate, PFOS perfluorooctane sulfonate, PM10 particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of less than 10 μm, PM2.5 particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of less than 2.5 μm. Outdoor environment buffers reflect distance from home address. b Predicted probabilities of cluster membership for the selected prenatal factors in the Northern/Western cohort derived from multinomial regression models controlled for study site, sex and age at examination. Solid lines represent the predicted probabilities and dotted lines represent their 95% CIs. c Same as (b) but for the Southern/Mediterranean cohort. The number of participants in each multi-omics cluster across cohorts was as follows: N = 227 for Cluster A, N = 150 for Cluster B and N = 180 for Cluster C in the Northern/Western cohort, and N = 238 for Cluster A, N = 21 for Cluster B, and N = 47 for Cluster C in the Southern/Mediterranean cohort. Source data for all panels are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

It is increasingly recognized that obesity is a complex phenotype encompassing a multitude of interconnected and interacting pathomechanisms. Once established, obesity poses a significant challenge to treat. Therefore, understanding the molecular biology of obesity, along with associated biomarker signatures and modifiable environmental determinants that could inform preventive or therapeutic measures, is becoming increasingly important. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study to apply a systems biology approach through deep, multi-omics profiling in a population-based cohort of children to identify and validate molecular signatures of obesity early in disease genesis and characterize subgroups with differing metabolic characteristics driven by distinct molecular pathways. We further incorporated information from the environmental “riskscape” of the critical pregnancy period, capturing widespread chemical exposures, outdoor and built environmental exposures, and demographic and lifestyle factors, to explore potential environmental contributors to disease risk early in the life course.

The primary aim of this study was to uncover the molecular mechanisms underpinning childhood obesity and associated metabolic dysfunction, rather than to develop a predictive risk score for metabolic outcomes. The bottom-up multi-omics clustering approach was selected to allow for the emergence of distinct molecular subtypes, enabling a data-driven exploration of metabolic health. While the metabolic syndrome score remains a valuable clinical tool for risk classification, it does not reflect the intricate molecular heterogeneity underlying obesity-associated metabolic dysfunction. By focusing on clusters derived from multi-omics profiles, our approach provides an understanding of biological pathways involved in metabolic health, beyond established clinical scores.

We followed a targeted approach in selecting omics biomarkers for investigation, as our objective was to provide an integrated framework to offer much-needed replication of existing literature, instead of pursuing novel discoveries. We acknowledge that we might have been underpowered for more exploratory endeavors. Previous research trying to characterize the molecular architecture of childhood obesity has been limited by small sample sizes, lack of a validation population, examination of body mass index only, and assessment of only one to two omics layers, thereby providing a limited coverage of the molecular landscape characterizing the obesity phenotype8,9,10. Our study overcomes limitations of prior literature in several ways. It is the largest muti-omics study of childhood obesity to date with a rich phenotypic metabolic characterization, the first to employ a unique design using a bottom-up approach from molecular omics to clinical clusters of children. Importantly, we recapitulated these clusters in an independent population, with comparable omics and phenotypic data, despite underlying sociodemographic differences between the cohorts. The similarity networks were generated using state-of-the-art omics profiling platforms, which not only provide broad molecular coverage, but they are also widely used in epidemiologic research and provide highly reproducible data.

In many current obesity treatment guidelines, diagnosis of obesity and treatment decisions are based on BMI41,42, despite the fact that at a given BMI, the individual variation in comorbidities and health risk factors is high43,44,45. Observational data show that a subgroup of individuals with obesity may be at a significantly higher risk than estimated solely from the positive association between BMI and cardiometabolic risk5,43,45,46. Our multi-omics approach in obesity identified clusters of children with differences in their phenotypic characteristics. Cluster C was identified as the cluster with the highest degree of metabolic dysfunction, characterized by increased adiposity and the strongest associations with adverse metabolic outcomes. Children in Cluster B appeared to have a relatively healthier metabolic profile; however, the potential for transition to a metabolically unhealthy state remains an important consideration, as these children may still be at risk for future metabolic complications. Recent studies highlight that metabolically healthy individuals with obesity carry a health risk and may transition to an unfavorable metabolic state5,45,47,48. Further research incorporating longitudinal follow-up data is needed to examine the trajectory of multi-omics profiles and provide insights into the risk of metabolic complications in the future.

Although our study utilized several omics layers, we recognize that resource constraints may limit the scope of omics layers feasible for other studies. Of the layers we analyzed, miRNA expression, transcriptomics, and proteomics proved particularly valuable for clustering profiles related to metabolic dysfunction and identifying key molecular pathways. For resource-limited settings, focusing on transcriptomics and proteomics could yield meaningful insights, as these layers capture broad gene expression changes and protein-level functional alterations, respectively. Together, they can provide a comprehensive view of the biological pathways central to obesity and metabolic dysfunction, thereby enhancing the utility of these analyses.

Inflammation plays a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of obesity and associated metabolic dysfunction, representing a critical area of study in understanding the complexities of these conditions4,49. Through examination and integration of different omics layers, our study unveiled a cascade of enriched inflammation-related pathways characterizing the high-risk cluster C, further elucidating the molecular underpinnings of the obesity phenotype. Recruitment of immune cells and inflammation, especially in adipose tissue, can start early in disease genesis49, which is consistent with our observation on many dysregulated immune cell differentiation and activation pathways in Cluster C. Enlarged adipocytes and polarized immune cells secrete a plethora of cytokines, including TNF-a, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-1b, and chemokines (MCP-1). These molecules serve as both paracrine and endocrine factors, instigating signaling cascades such as MAPK, JAK/STAT, TNF, and NFK-b pathways. The culmination of these events can lead to the development of insulin resistance and the perpetuation of inflammatory responses, thus forming a feed-forward loop of chronic inflammation49,50. Although elevated inflammatory cytokines are well-established cardiovascular risk factors, the majority of research has focused on the adult population, leaving a significant gap in our understanding of the onset of these biomarkers in children51. Addressing this knowledge deficit, our study delved into the proteomic profile of children and confirmed an elevation of the inflammatory cytokines in children belonging to the high-risk cluster. We also observed elevated CRP levels associated with the high-risk cluster, a well-established marker of systemic inflammation that has been shown in numerous prospective studies to predict cardiovascular events52,53. Animal in vivo and in vitro studies have reported that CRP is directly linked to endothelial function through alteration of vascular endothelial growth expression and nitric oxide synthase activity54,55.

We identified a signature of 14 miRNAs playing a significant role in the definition of the high-risk Cluster C. Among the miRNAs identified, four in particular (miR-23a, miR-24, miR-130a and miR-21) have gathered increased attention for their role in regulating key metabolic processes. Specifically, miR-23a and miR-24 are part of the miR-23 ~ 27 ~ 24 family which has been suggested to control effector immune cell responses and has been implicated in various physiological and pathological processes, including the atherosclerotic process56,57,58,59,60,61,62. Moreover, miR-130a has been reported to regulate the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells and angiogenesis63,64,65, potentially contributing to vascular remodeling and altered blood pressure66,67,68. miR-21 exerts pleiotropic effects in human metabolism, including roles in insulin action69,70 and hepatic inflammation71. Additionally, several DNA methylation markers were identified as contributing to the definition of Cluster C, albeit to a lesser extent than miRNAs. The CpGs cg08462942 and cg09615786 emerged as the strongest contributors. Notably, cg08462942 is annotated to ATG4B, an autophagy-related gene that has been implicated in adipogenesis72,73,74. The CpG cg09615786 is annotated to DCBLD2 which has been linked to endothelial function75. Further, one particularly interesting signature detected with the metabolomics data was the perturbed levels of the BCAA valine and non-essential amino acid glycine in the high-risk Cluster C. Elevated circulating levels of valine have consistently been reported in adults with diabetes76,77, and have been implicated in insulin resistance, possibly through 3-hydroxyisobutyrate driven lipotoxicity (e.g., diglyceride accumulation)78. Conversely, lower circulating glycine levels have been observed in metabolic disorders associated with obesity and diabetes79. It has been suggested that glycine metabolism should be considered in close interaction with BCAA metabolism, as muscle-liver trafficking of BCAA-derived nitrogen might play a role in glycine depletion80.

Environmental and lifestyle factors are estimated to account for 70–90% of the burden of human disease81. In light of this, precision environmental health has emerged as a new framework aiming to integrate environmental and biological factors to better understand associations and identify high-risk individuals15. In our study, we built upon this framework by introducing the prenatal environment as an additional dimension and employing a robust data science method to explore associations with health risk. Our models showed that environmental exposures were differentially associated with multi-omics cluster membership in the two parts of Europe. This can be probably attributed to differences in factors related to diet, lifestyle, socioeconomic status, or other demographic and cultural factors. Among a set of several prenatal factors, we identified pre-pregnancy BMI and maternal PFOA levels to be the strongest predictors of membership to the high-risk Cluster C in the Northern/Western cohort. Mothers from this part had in general a higher BMI but similar PFOA levels to those in the Southern/Mediterranean cohort. Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI has been shown to have persistent effects on long-term health in offspring82, with an accumulating body of evidence highlighting an association with future obesity risk83. PFOA is a manmade chemically stable compound that can cross the placenta84, and once in the human body, it exhibits a long elimination half-life85. Over the last years, PFOA has received increased attention for its potential adverse effects, with several studies, but not all, reporting an association with childhood obesity86,87. We also identified maternal exposure to mercury, a heavy metal designated as a high-priority pollutant by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)88, to be a risk factor for membership to Cluster C in the Southern/Mediterranean cohort. Blood mercury levels were much higher in this part, probably as a result of higher fish consumption89. Mercury has been shown to readily cross the human placenta barrier90. Similar to our findings, mercury exposure has previously been associated with metabolic syndrome, visceral adiposity, and insulin resistance91,92. Overall, our results underscore the importance of the modifiable prenatal environment linked to subsequent disease risk and highlight the need to tailor prevention guidelines to accommodate diverse country contexts. We acknowledge that potential gene-environment interactions may influence disease risk. For instance, a small study in the Faroes cohort recently showed that PFAS health effects and in particular associations observed with insulin sensitivity could vary between individuals as a result of genetic predisposition involving gene variants related to lipid and glucose metabolism93. Large-scale studies incorporating polygenic risk scores and environment-wide interaction models will be needed to comprehensively assess how genes interact with the environment to shape health outcomes.

Our study has some limitations. The omics measurements were conducted concurrently with the assessment of phenotypes, thereby limiting our ability to discern whether the identified biological signatures and underlying pathways are causal factors or consequences of obesity and metabolic dysfunction. However, we did observe an association between the high-risk multi-omics cluster in childhood and subsequent obesity traits in adolescence in a subsample of our population. Future investigations incorporating repeated omics and phenotyping measurements could elucidate the temporal dynamics and causal relationships of the biological mechanisms underlying obesity and metabolic dysregulation. The metabolomic platform used (LC-MS/MS, Biocrates kit) does not provide specific fatty acid side-chain composition for lipids and is limited in the number of metabolites identified, thereby providing partial coverage of the metabolome. However, this analytical method provides absolute concentrations of metabolites, with unambiguous annotation, has high interlaboratory reproducibility, and has been widely used in large-scale epidemiology studies94,95. While our study employed both targeted and untargeted methods, additional untargeted technologies—such as high-resolution mass spectrometry, shotgun proteomics, single-cell RNA sequencing, and metagenomics—could enhance the understanding of molecular pathways involved and help identify novel biomarkers and risk factors96. We utilized blood samples that were readily accessible for the assessment of omics profiles, however, we acknowledge that blood may not be the ideal target matrix for the relevant health outcomes. Future studies encompassing samples of adipose tissue, skeletal muscle and liver, which constitute main metabolic tissues of the human body, will provide a clear understanding of the intricate inter-tissue cross-talk underlying the pathophysiology of obesity and associated metabolic dysfunction. Further, given its observational design, our study identifies associations between prenatal factors and obesity-related outcomes but does not establish causation. Although our study included extensive prenatal data, we were unable to assess the effects of maternal diabetes and preeclampsia- two conditions closely associated with offspring’s metabolic health97,98- due to substantial missing data. However, we included pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain, which have been strongly linked to maternal metabolic health99,100,101. We assessed a wide variety of environmental factors, which might be prone to different types of exposure measurement error. Questionnaire-based assessment of diet, for instance, is known to be subject to potential misclassification, while outdoor air pollutants based on residential addresses have been shown to not highly correlate with short-term personal air pollution levels102. Nevertheless, the exposure assessment methods in our study have been widely used in large cohort studies and were applied using validated instruments. Our study provides insights into childhood obesity and metabolic dysfunction in a European cohort that mostly consists of white people. Expanding future research to include more ethnically and geographically diverse populations would be important for determining the generalizability of multi-omics clusters and associations across different demographic groups.

In summary, our study delves into the intricate molecular biology of childhood obesity and metabolic dysfunction. Through the integration of multi-omics profiling and prenatal environmental and lifestyle data, we unveil distinct metabolic clusters of children and identify potential modifiable risk factors. Our results may help to inform early-life prevention and intervention strategies aimed at combating obesity and its long-term health consequences.

Methods

Study participants

This study used data collected in the HELIX project14, a collaboration across six established and ongoing longitudinal population based cohorts, involving children from two large parts of Europe: the Northern/Western (N/W) part (study sites: Born in Bradford (BiB) cohort study, Bradford, UK; Étude des Déterminants pré et postnatals du développement et de la santé de l’Enfant (EDEN) cohort study, Poitiers, France; Kaunas cohort (KANC) study, Kaunas city, Lithuania; and Norwegian Mother, Father and Child (MoBa) cohort study, Oslo, Norway103) and the Southern/Mediterranean (S/M) part (study sites: INfancia y Medio Ambiente (INMA) cohort study, Sabadell, Spain; and RHEA Mother Child cohort study, Heraklion, Greece). Data collection was performed according to identical pre-defined standardized protocols across cohorts and conducted by trained staff. The full HELIX protocol and database are described elsewhere14.

All participating families provided written informed consent. Local ethical committees approved the studies that were conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethical committees for each cohort were the following: BIB: Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, EDEN: Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé, INMA: Comité Ético de Inverticación Clínica Parc de Salut MAR, KANC: Kaunas Regional Committee for Biomedical Research Ethics, MoBa: Regional komité for medisinsk og helsefaglig forskningsetikk, Rhea: Ethical committee of the general university hospital of Heraklion, Crete.

Multi-omics assessment

Blood samples were collected during the childhood follow-up visit at the end of the clinical examination, following a median (IQR) fasting time of 3.4 (2.8, 4.0) hours. Blood samples were collected using a ‘butterfly’ vacuum clip and processed into a variety of sample matrices: EDTA used for plasma proteomics, miRNAs, and DNA isolation; tempus tubes for RNA isolation; and plastic silica Vacutainers for serum metabolomics. All samples were processed and frozen at −80 °C under standardized procedures.

We used both targeted and untargeted methods to assess molecular features across five omics layers. For untargeted profiling, we assessed blood DNA methylation with the Illumina 450 K array, blood gene expression using the Affymetrix HTA v2.0 array and blood miRNA expression using the Agilent SurePrint Human miRNA rel 21 array. For targeted profiling, we assessed plasma proteins using three Luminex multiplex assays and serum metabolites with the LC-MS/MS Biocrates AbsoluteIDQ p180 kit. Further details about the omics biomarkers assessed in HELIX have been described previously24,104 and are available in Supplementary Data 1A-C.

Anthropometry and metabolic health outcomes

During the clinical examination of childhood follow-up, we assessed height and weight and calculated BMI age-and-sex–standardized z-scores (z-BMI) using the international World Health Organization (WHO) reference curves105. We followed the WHO criteria for defining childhood overweight or obesity (z-BMI > 1 SD)105. Bioelectric impedance analysis (BIA) was performed and we calculated the proportion of total fat mass using appropriate equations106. We also assessed waist circumference (WC) and blood pressure (BP) with common, standardized protocols14. HDL cholesterol, triglyceride, and ALT levels were quantified in serum using colorimetric methods according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Insulin levels were assessed using the human adipokine 15-plex magnetic panel. Following the criteria proposed in the European, multicenter IDEFICS study107, we constructed age- and sex-specific percentiles for waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and insulin91, and then calculated a metabolic syndrome risk score as follows: metabolic syndrome Score= z-WC + (– z-HDL cholesterol + z-triglyceride)/2 + z-insulin + (z-systolic BP + z-diastolic BP)/2. This score is used to reflect a metabolic health profile, with higher scores indicating a poorer profile, and has been previously validated in the European, multi-center IDEFICS study107. We also used a categorical definition of metabolically unhealthy status in childhood using consensus pediatric cut-offs21,22. Specifically, a metabolically unhealthy status was defined as the presence of at least one of the following metabolic risk factors: systolic or diastolic blood pressure ≥90th percentile, insulin ≥90th percentile, HDL cholesterol ≤40 mg/dl, triglycerides ≥110 mg/dl, and ALT ≥ 22.1 U/L for females or ≥25.8 U/L for males21,22.

We followed up a subset of our study population in adolescence, during which we assessed body mass index, waist circumference, and total fat mass using similar protocols and procedures as those in childhood.

Prenatal exposure variables

A total of 37 key maternal environmental exposures and characteristics were investigated in the study, including: exposures from the outdoor environment (air pollution, traffic, built environment, and surrounding green space); blood biomonitoring exposures (metals, organochlorine compounds [OCs], perfluoroalkyl substances [PFAS]); food group intakes (fish, legumes, dairy, meat, fruits and vegetables); and other social and lifestyle factors (tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, maternal education, maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain). A complete list of the prenatal factors investigated can be seen in Supplementary Table 7. As previously described38, missing maternal environmental exposure data (chemicals, metals, exposures from the outdoor environment, and diet) were imputed using a chained equations method implemented in the mice R package108. Prior to imputation, continuous exposure variables were transformed to achieve linearity or categorized, when needed. We used data on environmental factors with missing information <40%. Details on the assessment methods and distribution levels in HELIX can be found elsewhere14,38,109.

Data synthesis and analysis

Creation of multi-omics clusters

As a first step, we conducted a screening of published literature to identify and select omics molecules in blood, plasma and/or serum that are related to adiposity measures in children (<18 years of age). For DNA methylation, miRNAs and metabolomics, we searched for systematic reviews, published up to 15 March 2024, and evaluated included studies. For transcriptomics, we conducted a search of individual studies, as no systematic synthesis of published literature was available up to the index date. We also screened manually bibliographies of included articles and used expert input to identify any additional eligible studies. Details of our search strategy across these four omics layers are available in Supplementary Table 1. We then linked the omics molecules identified from the literature to the HELIX dataset. For the proteome data, no filtering was performed; our panels assessed a total of 35 proteins, all of which were included in the analysis.

Data from all omic layers were adjusted for key covariates and scaled to a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. Covariates included study site, child’s sex, child’s age at measurement, and child’s ethnicity (European ancestry; Pakistani or Asian; and other). In addition, plasma protein and serum metabolite levels were adjusted for time to last meal and technical batch. DNA methylation, miRNA expression, and gene expression data were corrected by surrogate variables (SVs), which captured both batch effects and blood cell type composition.

To derive biologically distinct molecular clusters, we used integrative network and clustering methods to the multi-omics data. We applied first our multi-omics approach in the population of N/W cohort and used the population from the S/M cohort as validation cohort. We computed distance matrices for each of the omic datasets with the amap R package110 using 1) Pearson distance for DNA methylation, miRNA expression, and gene expression data and 2) Euclidian distance for metabolome and proteome data. Then, we computed an affinity matrix of each dataset and derived a fused affinity matrix by similarity network fusion (SNF) using the SNFtool R package20. For defining the parameters k (number of neighbors) and sigma (hyperparameter), we performed a grid search across the recommended values by Wang and colleagues20 and chose those (k = 90 and sigma=0.8) that maximized the variance of the affinity matrix111. To identify mutually exclusive clusters, we then applied spectral clustering to the fused affinity matrix and chose the optimal number of clusters based on the eigen-gap best approach and the rotation cost approach111. We subsequently used label propagation, a graph-based semi-supervised method20, to predict the multi-omics clusters (as derived in children from the N/W cohort) in the cohort of children from the S/M part. This method leverages on nodes connected by edges (where similar subjects tend to have the same label) and propagates labels from labeled nodes to unlabeled ones through their interconnected edges in the integrated network. In this way, a child in multi-omics Cluster A in the N/W cohort had a similar multi-omics profile to an individual in multi-omics Cluster A in S/M, and so on.

Association of multi-omics clusters with clinical phenotypes

We assessed the relation of multi-omics clusters with several adiposity and metabolic traits. We applied generalized linear and logistic regression models (for continuous and categorical outcomes, respectively) while treating cluster membership as predictor and controlling for age at examination, sex and study site. Cluster A was chosen as the reference category for comparative analyses because it exhibited the lowest levels of adiposity and metabolic complications, thereby providing a clearer baseline for assessing metabolic health differences across clusters. To account for the differential follow-up in adolescence and potential attrition bias, we applied inverse probability weighting with the weightit R package by calculating weights based on the inverse of the probability of participating in the follow-up according to maternal education, study site, child sex, age, ethnicity, and weight status in childhood. We then included these weights in the adolescent regression models. All derived P-values were two-sided and a threshold of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Identification of molecular drivers of multi-omics clusters and pathway analysis

In our biological inquiry, we sought to identify which molecules had the highest contribution to the definition of the clusters. We thus applied XGboost with decision-tree based learner112 using the caret113 and xgboost114 R packages. XGboost is a nonlinear and nonparametric ensemble model that is able to handle high dimensionality even within a small dataset112. We applied a one-cluster-versus-the-rest approach and used the multi-omics molecules as predictors. Models’ hyperparameters were tuned in the N/W cohort (training set) using 5-fold cross-validation and the Gini coefficient as evaluation metric. We then assessed the final performance of each model in the S/M cohort (testing set) using the evaluation metrics accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, gmean, balanced accuracy and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), calculated with the confusionMatrix function in caret, the metrica115 and pROC116 R packages. Having established a high classifying capacity of our machine learning models, we then calculated SHAP values across all molecular features. By assessing both the magnitude and sign of each SHAP value, one can determine the impact of a feature on the final model prediction23. The size of the absolute mean SHAP value (across all subjects) reflects the magnitude of feature’s contribution to the model, with larger values indicating greater importance. The sign of the SHAP value indicates the direction of influence exerted by the feature on the final classification. For instance, in the context of binary classifiers such as ours (e.g., membership to Cluster C vs. membership to Cluster A or Cluster B), a positive SHAP value signifies that the feature steered the prediction towards Cluster C. We defined the top molecular drivers of the clusters as those features that had a mean absolute SHAP value within the top 25% of each cohort and had a mean SHAP value at concordant direction across cohorts.

We performed single-omics regression analyses to estimate the percentage change in each identified top feature associated with the multi-omics clusters. Further, for molecular layers whose features could be easily annotated to genes (DNA methylation, miRNA expression, gene transcription, and proteins), we performed enrichment (or over-presentation) analysis at the gene level using two public databases (KEGG, Gene Ontology Biological Processes). The ClusterProfiler R package117 were used to examine whether the list of genes annotated to the top features was enriched for a specific pathway. Significance of enriched pathways was tested using hypergeometric tests at a false discovery rate (FDR)-P value threshold of less than 0.05. For pathways of the Gene Ontology database belonging in the same parent-child hierarchy, we selected the pathways exhibiting the highest number of genes related to the features and/or the smallest FDR-P value. We report enriched pathways with ≥3 genes. We further evaluated tissue-specific expression patterns of the mapped genes by using the publicly available dataset of the GTEx project118. Expression levels were measured in Transcripts Per Million (TPM) to enable accurate comparisons across tissues.

Identification of prenatal determinants of the multi-omics clusters

We estimated correlations between the variables of interest using Pearson’s correlation for continuous vs continuous variables, R2 of a linear model for continuous vs categorical variables, and Cramér’s V test for categorical vs categorical variables in the first imputed exposure dataset. To identify the most important prenatal determinants of the multi-omics cluster, we applied LASSO penalized multinomial regression with cluster membership as the outcome, the prenatal variables as predictors and adjustment for study site, age and sex. LASSO considers all exposures simultaneously and performs variable selection by shrinking the lowest regression coefficients of the predictors, which correspond to the least informative ones, to zero. To enhance reliability of LASSO models, we applied a stability selection approach using resampling (K = 100 complementary subsamples of 80% of observations) and an automated calibration procedure implemented in the sharp R package40. The calibration procedure aims at identifying the pair of hyper-parameters (λ penalty parameter and π threshold in selection proportion) that maximizes model stability40. We applied this approach in each imputed exposure dataset and kept the variables with a mean selection proportion above the mean π across datasets. We subsequently fitted multinomial regression models adjusted for the same covariates as the LASSO models to obtain predicted probabilities of cluster membership related to the selected variables by using the nnet119 and ggeffects120 R packages.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings from this study are available within the manuscript and its supplementary information. Due to the HELIX data policy and data use agreement, human subjects’ data used in this project cannot be freely shared. Researchers external to the HELIX Consortium who have an interest in using data from this project for reproducibility or in using data held in the HELIX data warehouse for research purposes can apply for access to data for a specific manuscript at the time. Interested researchers should fill in the application found at https://www.projecthelix.eu/files/helix_external_data_request_procedures_final.pdf. and send it to helixdata@isglobal.org. The applications are received by the HELIX Coordinator, and are processed and approved by the HELIX Project Executive Committee. The decision to accept or reject a proposal is taken by the HELIX Project Executive Committee, and is based largely on potential overlap with other HELIX-related work, the adequacy of data protection plans, and the adequacy of authorship and acknowledgement plans. Further details on the content of the data warehouse (data catalogue) including those data used for the present study and procedures for external access are described on the project website https://www.projecthelix.eu/es/data-inventory. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The software program and packages used to conduct the present analyses are freely available and can be found via the citations in the manuscript. The code used for the present analysis can be found at: Stratakis N. Multi-omics architecture of obesity and metabolic dysfunction: identifying biological pathways and prenatal determinants. nstrata/multiomics_childhood_obesity. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14354199.

References

Bluher, M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 15, 288–298 (2019).

Report on the fifth round of data collection, 2018–2020: WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI). (WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, 2022).

Magge, S. N. et al. The metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents: shifting the focus to cardiometabolic risk factor clustering. Pediatrics 140, e20171603 (2017).

Powell-Wiley, T. M. et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation 143, e984–e1010 (2021).

Stefan, N., Haring, H. U. & Schulze, M. B. Metabolically healthy obesity: the low-hanging fruit in obesity treatment? Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 6, 249–258 (2018).

Bluher, M. Metabolically Healthy Obesity. Endocr. Rev. 41, bnaa004 (2020).

Iacobini, C., Pugliese, G., Blasetti Fantauzzi, C., Federici, M. & Menini, S. Metabolically healthy versus metabolically unhealthy obesity. Metabolism 92, 51–60 (2019).

Paczkowska-Abdulsalam, M. & Kretowski, A. Obesity, metabolic health and omics: Current status and future directions. World J. Diab. 12, 420–436 (2021).

Aleksandrova, K., Egea Rodrigues, C., Floegel, A. & Ahrens, W. Omics biomarkers in obesity: novel etiological insights and targets for precision prevention. Curr. Obes. Rep. 9, 219–230 (2020).

Drouard, G. et al. Longitudinal multi-omics study reveals common etiology underlying association between plasma proteome and BMI trajectories in adolescent and young adult twins. BMC Med. 21, 508 (2023).

Cifuentes, L., Hurtado, A. M., Eckel-Passow, J. & Acosta, A. Precision medicine for obesity. Dig. Dis. Inter. 5, 239–248 (2021).

Karczewski, K. J. & Snyder, M. P. Integrative omics for health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet 19, 299–310 (2018).

Gawlik, A. et al. Personalized approach to childhood obesity: Lessons from gut microbiota and omics studies. Narrative review and insights from the 29th European childhood obesity congress. Pediatr. Obes. 16, e12835 (2021).

Maitre, L. et al. Human Early Life Exposome (HELIX) study: a European population-based exposome cohort. BMJ Open 8, e021311 (2018).

Baccarelli, A., Dolinoy, D. C. & Walker, C. L. A precision environmental health approach to prevention of human disease. Nat. Commun. 14, 2449 (2023).

Gluckman, P. D., Hanson, M. A., Cooper, C. & Thornburg, K. L. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 61–73 (2008).

Perng, W. & Aslibekyan, S. Find the needle in the haystack, then find it again: replication and validation in the ‘omics era. Metabolites 10, 286 (2020).

Ruan, P., Wang, Y., Shen, R. & Wang, S. Using association signal annotations to boost similarity network fusion. Bioinformatics 35, 3718–3726 (2019).

Torres-Martos, A. et al. Omics data preprocessing for machine learning: a case study in childhood obesity. Genes (Basel) 14, 248 (2023).

Wang, B. et al. Similarity network fusion for aggregating data types on a genomic scale. Nat. Methods 11, 333–337 (2014).

Damanhoury, S. et al. Defining metabolically healthy obesity in children: a scoping review. Obes. Rev. 19, 1476–1491 (2018).

Vos, M. B. et al. NASPGHAN Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children: Recommendations from the Expert Committee on NAFLD (ECON) and the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN). J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 64, 319–334 (2017).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From Local Explanations to Global Understanding with Explainable AI for Trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67 (2020).

Maitre, L. et al. Multi-omics signatures of the human early life exposome. Nat. Commun. 13, 7024 (2022).

Garcia-Campos, M. A., Espinal-Enriquez, J. & Hernandez-Lemus, E. Pathway analysis: state of the art. Front Physiol. 6, 383 (2015).

Geijtenbeek, T. B. & Gringhuis, S. I. Signalling through C-type lectin receptors: shaping immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 465–479 (2009).

Jialal, I., Kaur, H. & Devaraj, S. Toll-like receptor status in obesity and metabolic syndrome: a translational perspective. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99, 39–48 (2014).

Sarapultsev, A. et al. JAK-STAT signaling in inflammation and stress-related diseases: implications for therapeutic interventions. Mol. Biomed. 4, 40 (2023).

Molinaro, A. et al. Insulin-Driven PI3K-AKT signaling in the hepatocyte is mediated by redundant PI3Kalpha and PI3Kbeta activities and is promoted by RAS. Cell Metab. 29, 1400–1409.e1405 (2019).

Gonzalez, P., Lozano, P., Ros, G. & Solano, F. Hyperglycemia and oxidative stress: an integral, updated and critical overview of their metabolic interconnections. Int J. Mol. Sci. 24, 9352 (2023).

Bengal, E., Aviram, S. & Hayek, T. p38 MAPK in glucose metabolism of skeletal muscle: beneficial or harmful? Int J. Mol. Sci. 21, 6480 (2020).

Nandipati, K. C., Subramanian, S. & Agrawal, D. K. Protein kinases: mechanisms and downstream targets in inflammation-mediated obesity and insulin resistance. Mol. Cell Biochem. 426, 27–45 (2017).

Celletti, F. L. et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor enhances atherosclerotic plaque progression. Nat. Med 7, 425–429 (2001).

Forstermann, U., Xia, N. & Li, H. Roles of vascular oxidative stress and nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 120, 713–735 (2017).

Giordano, F. J. Oxygen, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and heart failure. J. Clin. Invest 115, 500–508 (2005).

Akhtar, S. et al. Endothelial hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha promotes atherosclerosis and monocyte recruitment by upregulating MicroRNA-19a. Hypertension 66, 1220–1226 (2015).

GTEx Consortium. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 369, 1318–1330 (2020).

Tamayo-Uria, I. et al. The early-life exposome: Description and patterns in six European countries. Environ. Int 123, 189–200 (2019).

Robinson, O. et al. The urban exposome during pregnancy and its socioeconomic determinants. Environ. Health Perspect. 126, 077005 (2018).

Bodinier, B., Filippi, S., Nost, T. H., Chiquet, J. & Chadeau-Hyam, M. Automated calibration for stability selection in penalised regression and graphical models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C. Appl Stat. 72, 1375–1393 (2023).

Jensen, M. D. et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation 129, S102–S138 (2014).

Garvey, W. T. et al. American association of clinical endocrinologists and american college of endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr. Pr. 22, 1–203 (2016).

Beyene, H. B. et al. Metabolic phenotyping of BMI to characterize cardiometabolic risk: evidence from large population-based cohorts. Nat. Commun. 14, 6280 (2023).

Sims, E. A. Are there persons who are obese, but metabolically healthy? Metabolism 50, 1499–1504 (2001).

Neeland, I. J., Poirier, P. & Despres, J. P. Cardiovascular and metabolic heterogeneity of obesity: clinical challenges and implications for management. Circulation 137, 1391–1406 (2018).

Piche, M. E., Tchernof, A. & Despres, J. P. Obesity phenotypes, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Circ. Res. 126, 1477–1500 (2020).

Lee, H., Kim, J. S. & Shin, H. Predicting the transition to metabolically unhealthy obesity among young adults with metabolically healthy obesity in south korea: nationwide population-based study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 10, e52103 (2024).

Gao, M. et al. Metabolically healthy obesity, transition to unhealthy metabolic status, and vascular disease in Chinese adults: A cohort study. PLoS Med. 17, e1003351 (2020).

Wu, H. & Ballantyne, C. M. Metabolic Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Obesity. Circ. Res. 126, 1549–1564 (2020).

Wu, H. & Ballantyne, C. M. Skeletal muscle inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. J. Clin. Invest 127, 43–54 (2017).

Balagopal, P. B. et al. Nontraditional risk factors and biomarkers for cardiovascular disease: mechanistic, research, and clinical considerations for youth: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 123, 2749–2769 (2011).

Ridker, P. M. Clinical application of C-reactive protein for cardiovascular disease detection and prevention. Circulation 107, 363–369 (2003).

Alfaddagh, A. et al. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease: From mechanisms to therapeutics. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 4, 100130 (2020).

Hein, T. W. et al. Human C-reactive protein induces endothelial dysfunction and uncoupling of eNOS in vivo. Atherosclerosis 206, 61–68 (2009).

Badimon, L. et al. C-Reactive Protein in Atherothrombosis and Angiogenesis. Front Immunol. 9, 430 (2018).

Sprenkle, N. T. et al. The miR-23-27-24 clusters drive lipid-associated macrophage proliferation in obese adipose tissue. Cell Rep. 42, 112928 (2023).

Garavelli, S. et al. Plasma circulating miR-23~27~24 clusters correlate with the immunometabolic derangement and predict C-peptide loss in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 63, 2699–2712 (2020).

Cho, S. et al. miR-23~27~24 clusters control effector T cell differentiation and function. J. Exp. Med. 213, 235–249 (2016).

Guo, J. et al. Hsa-miRNA-23a-3p promotes atherogenesis in a novel mouse model of atherosclerosis. J. Lipid Res. 61, 1764–1775 (2020).

Peng, M. et al. Extracellular vesicles carrying proinflammatory factors may spread atherosclerosis to remote locations. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 79, 430 (2022).

Wang, M. et al. Obesity-induced overexpression of miRNA-24 regulates cholesterol uptake and lipid metabolism by targeting SR-B1. Gene 668, 196–203 (2018).

Ng, R. et al. Inhibition of microRNA-24 expression in liver prevents hepatic lipid accumulation and hyperlipidemia. Hepatology 60, 554–564 (2014).

Chen, Y. & Gorski, D. H. Regulation of angiogenesis through a microRNA (miR-130a) that down-regulates antiangiogenic homeobox genes GAX and HOXA5. Blood 111, 1217–1226 (2008).

Cavallari, C. et al. miR-130a and Tgfbeta content in extracellular vesicles derived from the serum of subjects at high cardiovascular risk predicts their in-vivo angiogenic potential. Sci. Rep. 10, 706 (2020).

Wu, W. H. et al. MicroRNA-130a mediates proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells in hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 24, 1087–1093 (2011).

Wei, C. et al. Circulating miRNAs as potential marker for pulmonary hypertension. PLoS One 8, e64396 (2013).

Karolina, D. S. et al. Circulating miRNA profiles in patients with metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, E2271–E2276 (2012).

Urbich, C., Kuehbacher, A. & Dimmeler, S. Role of microRNAs in vascular diseases, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 79, 581–588 (2008).

Roggli, E. et al. Involvement of microRNAs in the cytotoxic effects exerted by proinflammatory cytokines on pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes 59, 978–986 (2010).

Calo, N. et al. Stress-activated miR-21/miR-21* in hepatocytes promotes lipid and glucose metabolic disorders associated with high-fat diet consumption. Gut 65, 1871–1881 (2016).

Loyer, X. et al. Liver microRNA-21 is overexpressed in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and contributes to the disease in experimental models by inhibiting PPARalpha expression. Gut 65, 1882–1894 (2016).

Fernandez, A. F. et al. Autophagy couteracts weight gain, lipotoxicity and pancreatic beta-cell death upon hypercaloric pro-diabetic regimens. Cell Death Dis. 8, e2970 (2017).

Haim, Y. et al. Elevated autophagy gene expression in adipose tissue of obese humans: A potential non-cell-cycle-dependent function of E2F1. Autophagy 11, 2074–2088 (2015).

Martinez-Garcia, G. G. et al. Autophagy Deficiency by Atg4B Loss Leads to Metabolomic Alterations in Mice. Metabolites 11, 481 (2021).

Guo, L. et al. DCBLD2 deletion increases hyperglycemia and induces vascular remodeling by inhibiting insulin receptor recycling in endothelial cells. FEBS J. 291, 4076–4095 (2024).

Wang, T. J. et al. Metabolite profiles and the risk of developing diabetes. Nat. Med. 17, 448–453 (2011).

Guasch-Ferre, M. et al. Metabolomics in prediabetes and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diab. Care 39, 833–846 (2016).

Jang, C. et al. A branched-chain amino acid metabolite drives vascular fatty acid transport and causes insulin resistance. Nat. Med. 22, 421–426 (2016).

Alves, A. & Morio, B. Alterations in glycine metabolism in obesity and chronic metabolic diseases - an update on new advances. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 26, 50–54 (2023).

White, P. J. et al. Muscle-Liver Trafficking of BCAA-Derived Nitrogen Underlies Obesity-Related Glycine Depletion. Cell Rep. 33, 108375 (2020).

Rappaport, S. M. & Smith, M. T. Epidemiology. Environment and disease risks. Science 330, 460–461 (2010).

Godfrey, K. M. et al. Influence of maternal obesity on the long-term health of offspring. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 5, 53–64 (2017).

Voerman, E. et al. Maternal body mass index, gestational weight gain, and the risk of overweight and obesity across childhood: An individual participant data meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 16, e1002744 (2019).

Mamsen, L. S. et al. Concentrations of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in human embryonic and fetal organs from first, second, and third trimester pregnancies. Environ. Int 124, 482–492 (2019).

Lindstrom, A. B., Strynar, M. J. & Libelo, E. L. Polyfluorinated compounds: past, present, and future. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 7954–7961 (2011).

Stratakis, N. et al. Prenatal exposure to persistent organic pollutants and childhood obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of human studies. Obes. Rev. 23, e13383 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Associations of gestational perfluoroalkyl substances exposure with early childhood BMI z-scores and risk of overweight/obesity: results from the ECHO Cohorts. Environ. Health Perspect. 131, 67001 (2023).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Priority Pollutant List. Vol. 2020 (December 2014).

Stratakis, N. et al. Fish Intake in Pregnancy and Child Growth: A Pooled Analysis of 15 European and US Birth Cohorts. JAMA Pediatr. 170, 381–390 (2016).

Needham, L. L. et al. Partition of environmental chemicals between maternal and fetal blood and tissues. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 1121–1126 (2011).

Stratakis, N. et al. Association of fish consumption and mercury exposure during pregnancy with metabolic health and inflammatory biomarkers in children. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e201007 (2020).

Roy, C., Tremblay, P. Y. & Ayotte, P. Is mercury exposure causing diabetes, metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance? A systematic review of the literature. Environ. Res. 156, 747–760 (2017).

Valvi, D. et al. Gene-environment interactions in the associations of PFAS exposure with insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function in a Faroese cohort followed from birth to adulthood. Environ. Res. 226, 115600 (2023).

Siskos, A. P. et al. Interlaboratory reproducibility of a targeted metabolomics platform for analysis of human serum and plasma. Anal. Chem. 89, 656–665 (2017).

Floegel, A. et al. Identification of serum metabolites associated with risk of type 2 diabetes using a targeted metabolomic approach. Diabetes 62, 639–648 (2013).

Cani, P. D. & Van Hul, M. Gut microbiota in overweight and obesity: crosstalk with adipose tissue. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, 164–183 (2024).

Feig, D. S. et al. Long-term neurobehavioral and metabolic outcomes in offspring of mothers with diabetes during pregnancy: a large, population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. Diab. Care 47, 1568–1575 (2024).

Yang, F. et al. Association of maternal preeclampsia with offspring risks of ischemic heart disease and stroke in Nordic countries. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2242064 (2022).

Bodnar, L. M., Ness, R. B., Markovic, N. & Roberts, J. M. The risk of preeclampsia rises with increasing prepregnancy body mass index. Ann. Epidemiol. 15, 475–482 (2005).

Brunner, S. et al. Excessive gestational weight gain prior to glucose screening and the risk of gestational diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetologia 58, 2229–2237 (2015).

Shirvanifar, M. et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes attributable to overweight and obesity across maternal birth regions: a Swedish population-based cohort study. Lancet Public Health 9, e776–e786 (2024).

Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. et al. Variability in and agreement between modeled and personal continuously measured black carbon levels using novel smartphone and sensor technologies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 2977–2982 (2015).

Magnus, P. et al. Cohort profile update: the norwegian mother and child cohort study (MoBa). Int. J. Epidemiol. 45, 382–388 (2016).

Robinson, O. et al. Associations of four biological age markers with child development: A multi-omic analysis in the European HELIX cohort. Elife 12, e85104 (2023).

de Onis, M. et al. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull. World Health Organ 85, 660–667 (2007).

Clasey, J. L., Bradley, K. D., Bradley, J. W., Long, D. E. & Griffith, J. R. A new BIA equation estimating the body composition of young children. Obes. (Silver Spring) 19, 1813–1817 (2011).

Ahrens, W. et al. Metabolic syndrome in young children: definitions and results of the IDEFICS study. Int J. Obes. (Lond.) 38, S4–S14 (2014).

van Buuren, S. & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J. Stat. Soft 45, 1–67 (2011).

Haug, L. S. et al. In-utero and childhood chemical exposome in six European mother-child cohorts. Environ. Int 121, 751–763 (2018).

CRAN—Package amap.

Chen, Y. et al. The value of prospective metabolomic susceptibility endotypes: broad applicability for infectious diseases. EBioMedicine 96, 104791 (2023).

Chen. T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 (Association for Computing Machinery, San Francisco, California, 2016).

Kuhn, M. Building Predictive Models in R Using the caret Package. J. Stat. Soft 28, 1–26 (2008).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. in KDD ‘16: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785-794 (San Francisco,California 2016).

Correndo, A. A. et al. metrica: an R package to evaluate prediction performance of regression and classification point-forecast models. JOSS 7, 4655 (2022).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinforma. 12, 77 (2011).

Wu, T. et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innov. (Camb.) 2, 100141 (2021).

The data used for the analysis described in this manuscript were obtained from the GTEx Portal https://www.gtexportal.org/home/.

Venables, W. N. & Ripley, B. D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, (Springer, New York, 2002).

Lüdecke, D. ggeffects: tidy data frames of marginal effects from regression models. JOSS 3, 772 (2018).

Acknowledgements