Abstract

Water is crucial for meeting sustainability targets, but its unsustainable use threatens human wellbeing and the environment. Past assessments of water scarcity (i.e., water demand in exceedance of availability) have often been spatially coarse and temporally limited, reducing their utility for targeting interventions. Here we perform a detailed monthly sub-basin assessment of the evolution of blue (i.e., surface and ground) water scarcity (years 1980-2015) for the world’s three most populous countries – China, India, and the USA. Disaggregating by specific crops and sectors, we find that blue water demand rose by 60% (China), 71% (India), and 27% (USA), dominated by irrigation for a few key crops (alfalfa, maize, rice, wheat). We also find that unsustainable demand during peak months of use has increased by 101% (China), 82% (India), and 49% (USA) and that 32% (China), 61% (India), and 27% (US) of sub-basins experience at least 4 months of scarcity. These findings demonstrate that rising water demands are disproportionately being met by water resources in already stressed regions and provide a basis for targeting potential solutions that better balance the water needs of humanity and nature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Meeting multiple United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) related to poverty, food security, sanitation, clean energy, and human health requires the long-term sustainability of global water resources1. Yet multiple pressures continue to mount because of rising human water demands and increasing variability in water availability. Agriculture is the dominant water consumer globally – accounting for approximately 90% of humanity’s water footprint2, and irrigated agriculture continues to expand3,4. Domestic water demand (particularly in cities) is projected to rise substantially despite deepening surface water deficits5. The water needs of the mining sector are also expected to grow, in particular with the expanding extraction of non-conventional fuel sources (e.g., shale oil and gas) in water-stressed regions6. The water footprint of industrial production is also projected to experience the most rapid growth of any sector by 2050 under most socio-economic development pathways7. These various demands are already producing widespread water scarcity8,9,10 – broadly defined as when human and environmental water requirements exceed water availability. The growth in water demands coupled with lessening and more variable water supplies portends both deepening and expanding water scarcity issues globally.

In recognition of these current and future water sustainability challenges, numerous water scarcity assessments have recently emerged, providing an important understanding of humanity’s water demand in relation to water resource availability. A suite of global studies has evaluated patterns of annual water scarcity, showing hotspots of unsustainable water demand in the US High Plains and Southwest, northern China, northern India, the Middle East, and eastern Australia, among other locations11,12,13,14. However, regions throughout the world experience seasonal variations in both demand and availability which are often not well captured within annual assessments. To address this limitation, other studies have evaluated monthly water scarcity, highlighting many places where water demand exceeds availability for a portion of the year8,9,15,16. While all of this work has enhanced our understanding of patterns of water scarcity, there has been a lack of temporal coverage (i.e., time series) combined with spatial (i.e., sub-basin), temporal (i.e., monthly), and sectoral granularity, which can provide important new insights into how, where, and why patterns of water scarcity have evolved - seasonally and annually - in recent decades. In addition, many existing intervention programs often evaluate solutions in geographic and sectoral isolation and do not account for the multiple scales and actors affected by individual water sustainability interventions. Developing a spatially and temporally detailed understanding of how sector-specific water demands have emerged in recent decades is therefore a critical step both in determining how often, and by what magnitude, areas are experiencing conditions of water scarcity as well as in identifying solutions that account for the interconnectivity of human-water systems and can align anticipated water needs with places of sufficient and timely water availability. As such, we seek to develop a transferable approach that fuses the benefits of regional (i.e., context specificity) and global (i.e., inter-regional comparability) water assessments, while overcoming some of their key shortcomings (i.e., highly customized and parameterized; broad simplifying assumptions, respectively). Our approach also explicitly accounts for environmental flow requirements across entire countries at such fine levels of spatial, temporal, and sectoral disaggregation. The combination of these innovative elements can enable comparison across scales, readily allows for the incorporation of other sustainability considerations beyond water (e.g., food security, energy, climate change, etc.), and promises to provide a new understanding of the challenges and opportunities for improved water sustainability across large extents.

Here we examine in detail the spatiotemporal evolution of water demand and seasonal (i.e., sub-annual) and chronic (i.e., annual) water scarcity in the world’s most populous countries – China, India, and the United States – which alone account for 41% of the global population17, 49% of blue water demand2, and 39% of food production18. Due to differences in the temporal coverage of the various input datasets (and in particular, the 5- or 10-year span between agricultural censuses), the time periods evaluated for China, India, and the United States are 1980–2015, representing the most up-to-date and comprehensive data available. We focus on blue water (i.e., surface and groundwater) because of its importance in multiple societal sectors and its potential for competing demands. We define water scarcity as the condition when blue water demand exceeds renewable blue water availability (i.e., total blue water availability minus environmental flows8,19 - where environment flows refer to the water required to support aquatic ecosystems and the livelihoods that depend on them19,20). For each study country, we developed time series of district-level crop-specific irrigated areas21,22,23,24 and combined these with gridded (5 arcminute) monthly crop water requirements25 to estimate monthly irrigation water demand. These crop-specific blue water demands were then summed with sector-specific (i.e., direct livestock (i.e., watering and cleaning), mining, domestic, manufacturing, electricity generation (i.e., cooling of thermal power plants)) estimates of monthly blue water consumption26 (i.e., evapotranspiration; not withdrawals) to calculate total monthly blue water consumption. To evaluate unsustainable water demand (i.e., the volume of consumptive water demand in exceedance of renewable blue water availability) and blue water scarcity, we then aggregate these water consumption estimates to the sub-basin level (2443 sub-basins across the study countries) and compare them to monthly estimates of total blue water availability27, using a range-of-variance approach to account for environmental flow requirements19. In doing so, we are able to evaluate spatially detailed monthly (i.e., seasonal) and annual (i.e., chronic) trends in water scarcity, quantify where and to what extent volumes of unsustainable water demand have increased (i.e., intensified), and identify the dominant water user in each sub-basin. With critical implications for global water security, understanding the degree to which these countries have been able to achieve sustainable water use can provide important insights into the efficacy of their water resource management efforts since the start of the century and point to potential solutions for addressing water sustainability challenges.

Results

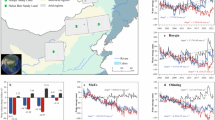

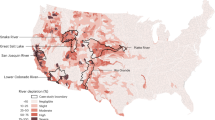

Blue water demand has increased through time (1980–2015) (Fig. 1), with steady increases in both China (from 118 km3 to 201 km3; +70%) and India (from 177 km3 to 323 km3; +83%) and plateauing in the US (from 86 km3 to 105 km3; +22%) – attributable to a decoupling of water use and agricultural economic productivity as well as geographic shifts in irrigated area28,29. For all three countries, irrigation for crop production was the chief consumer of blue water (80% of total blue water demand for China in 2015, 95% for India, and 81% for the US), though the relative importance of the crops that constituted this demand differed (Figs. S1–S3). In China, just three crops – wheat (20% of total blue water demand), rice (19%), and maize (15%) – made up more than half of total blue water demand across all sectors (Figs. 1 and 2a). This homogeneity of water consumption was even more pronounced in India where irrigation for rice (29%), wheat (26%), and sugarcane (14%) comprises more than two-thirds of the country’s total blue water demand (Figs. 1 and 2b). In the US, alfalfa (25% of total blue water demand) and maize (22%) dominated irrigation and total demand (Figs. 1 and 2c). These dominant crops for blue water demand also varied seasonally (Figs. 3–5). For example, in the North China Plain, wheat dominated water demand from October through May, while maize had higher demand from June to September. In northwest China, wheat (January–April) and cotton (May–November) alternate as the highest water consumers. In central and western India, a mosaic of different crops dominates water demand seasonally. In the Ogallala Aquifer region of the US Midwest, wheat’s dominance (March–May) is replaced by maize (June–October) as the year progresses. While these main crops account for large fractions of blue water demand at the national level, we find substantial spatial heterogeneity between sub-national units in terms of dominant water users, with regionalized patterning (Fig. 2). Notably, crop production was not the dominant water user in 41% of sub-basins in China (e.g., livestock in central-western China), 10% of sub-basins in India (e.g., domestic in eastern India), and 35% of sub-basins in the US (e.g., domestic, livestock, and thermo-electric power generation in the eastern US).

Time series in the left-hand column show the total blue water demand by sector for a China, c India, and e the USA. Time series in the right-hand column show the unsustainable blue water demand by sector for b China, d India, and f the USA. A list of all crops can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

The sub-basin level sector or crop with the highest volume of blue water demand for 2011–2015 in a China, b India, and c the USA along with d a global inset map. Following Brauman et al. 8, our analysis did not consider sub-basins smaller than 1000 km2 (shown in white).

a–l show the sub-basin level sector or crop with the highest volume of monthly blue water demand for 2011–2015 in China. Following Brauman et al. 8, the analysis did not consider sub-basins smaller than 1000 km2 (shown in white).

a–l show the sub-basin level sector or crop with the highest volume of monthly blue water demand for 2011–2015 in India. Following Brauman et al. 8, the analysis did not consider sub-basins smaller than 1000 km2 (shown in white).

a–l show the sub-basin level sector or crop with the highest volume of monthly blue water demand for 2011–2015 in the USA. Following Brauman et al. 8, the analysis did not consider sub-basins smaller than 1000 km2 (shown in white).

We evaluated total blue water demand and availability as there is no comprehensive or sufficient information on sector- or crop-specific blue water sourcing (i.e., surface or groundwater). Thus, unsustainable water demand in a location can potentially lead to streamflow depletion, reservoir drawdown, groundwater depletion, or a combination thereof depending on the water sources utilized. We find that the rising blue water demands of all of these sectors have generally increased volumes of unsustainable water demand (i.e., the volume of blue water demand in excess of renewable availability) with time (Fig. 6). Specifically, between the periods 1980–1984 and 2011–2015, we estimate that unsustainable blue water demand has risen by 101% in China, 82% in India, and 49% in the US and currently accounts for 30%, 61%, and 44% of average (2011–2015) total blue water demand, respectively (Fig. 1). Our findings also show that seasonal unsustainable water demand has grown dramatically in magnitude, particularly during the primary growing seasons in China, India and the US (Fig. 6; Fig. S6). In China, unsustainable demand has expanded temporally – from a sharp peak in May (1980–1984) to now growing by 30% and 101% between 1980–1984 and 2011–2015 in May and June, respectively – due in large part to the steady expansion of maize. In the US, unsustainable demand for July grew by +48%, and August by +49% between 1980–1984 and 2011–2015 – due to the expansion of alfalfa and maize – but has remained steady in more recent years (i.e., 1997 onward). Conversely, in India, unsustainable demand has continued to steadily increase throughout the study period, rising by +57% in March, +66% in April, and +99% in May when irrigated wheat and rice are primarily grown.

Examining the spatiotemporal evolution of blue water scarcity also allowed us to identify regions of seasonal and chronic water scarcity as well as hotspots of intensifying unsustainable water demand. While we find that 10% of study sub-basins experienced annual water scarcity (i.e., annual blue water demand exceeds annual renewable availability) across the three study countries, more than half (57%) of sub-basins were under some level of blue water scarcity (i.e., 1 month or greater) when examining seasonal water scarcity in these three countries. In China, we see that 32% of sub-basins experienced on average at least 4 months of water scarcity in the period 2011–2015, with unsustainable demand concentrated in the arid northwest and the agriculturally important northeast (including the Huang-Huai-Hai region) (Fig. 7b). Seasonal water scarcity increased in sub-basins in the North China Plain but decreased in central China (Fig. 7c). In India, the state of water scarcity is stark, with 61% of all sub-basins subject to unsustainable demand for at least 4 months and seasonal water scarcity occurring even in locations that are perceived as relatively water-abundant (e.g., southern and western India) (Fig. 7e). Unsustainable water demand also appears to have shifted and intensified, particularly in the northern and central parts of the country (where irrigated rice-wheat systems and sugarcane cultivation dominate) (Figs. 7f, 4, 8; Figs. S2, S4–S5;). In the US, 27% of all sub-basins – mostly in the western half of the country – experienced seasonal water scarcity (i.e., 4 months or more) (Fig. 7h), with notable increases in water-scarce months in sub-basins in Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah (Fig. 7i). Comparing changes in total water demand with changes in unsustainable water demand can also shed light on whether increasing water demand or decreasing water availability is the dominant contributor to intensifying water scarcity. In 71% (China), 71% (India), and 56% (USA) of sub-basins where unsustainable water demand increased, we find that total water demand increased more quickly, suggesting that increasing water demands (and not decreasing water availability) has been the primary contributor to intensifying water scarcity in these places (Fig. 9). Taken together, all of these results show that a large portion of the growth in blue water demand within the study countries has been met unsustainably by increasing blue water abstractions in locations where demand already exceeded availability.

Maps show the average number of months per year for which each sub-basin experienced blue water scarcity for the period 1980–1984 and 2011–2015 in China (a, b), India (d, e), and the United States (g, h). c, f, i show the change in number of months under blue water scarcity; positive values indicate that the average number of months with blue water scarcity increased between the periods 1980–1984 and 2011–2015. Negative values indicate a decrease in seasonal blue water scarcity. Following Brauman et al. 8, the analysis did not consider sub-basins smaller than 1000 km2 (shown in white).

Maps show the unsustainable blue water demand for the period 1980–1984 and 2011–2015 in China (a, b), India (d, e), and the United States (g, h). c, f, i show the change in unsustainable blue water demand; positive values indicate that unsustainable blue water demand worsened between the periods 1980–1984 and 2011–2015. Negative values indicate an improvement in unsustainable blue water demand. Following Brauman et al. 8, the analysis did not consider sub-basins smaller than 1000 km2 (shown in white).

Maps show the primary contributor to the changes in unsustainable blue water demand (UBWD) in China (a), India (b), and the United States (c) during the periods 1980–1984 and 2011–2015, analyzed from the perspectives of both water demand and water availability. Unsustainable blue water demand was estimated by month and then summed for each year. Based on the change in annual unsustainable blue water demand and the change in annual water demand between 1980–1984 and 2011–2015, we then identified the primary contributor to the changes in annual unsustainable blue water demand. Purple regions show where unsustainable water demand worsened over the time period, with darker purple indicating that increasing water demand is the dominant contributor to intensifying water scarcity, while lighter purple indicates decreasing water availability is the dominant contributor to intensifying water scarcity. Conversely, green regions show where unsustainable water demand decreased over the time period, with darker green indicating that increasing water availability is the dominant contributor to alleviating water scarcity and lighter green indicating decreasing water demand is the dominant contributor to alleviating water scarcity. Following Brauman et al. 8, the analysis did not consider sub-basins smaller than 1000 km2 (shown in white).

Lastly, we evaluated 88 combinations of input datasets to quantify the extent to which our estimates are sensitive to specific inputs and variables. For blue water demand, we used four crop water requirements (CWRs) datasets, two approaches for translating gridded CWRs to the county level, and considered temporally fixed or time-varying monthly CWRs. For renewable blue water availability, we assessed the uncertainty of total blue water availability using eleven global hydrological models. Across all input combinations, the range of estimates for total crop blue water demand in the year 2015 was 141–181 km3 (95% confidence interval in a bootstrap analysis) in China, 229–385 km3 in India, and 71–99 km3 in the United States (Fig. 10). Renewable blue water availability estimates ranged from 1724 to 1953 km3 in China, 870 to 1011 km3 in India, and 1185 to 1539 km3 in the United States (Fig. S7). Taken together, this produced ranges of unsustainable blue water demand China (58–68 km3), India (175–222 km3), and the United States (39–47 km3) (Fig. S8). While the magnitudes of blue water demand and renewable blue water availability unsurprisingly vary based on the specific combination of input datasets, we find high consistency in the spatial patterns and temporal trends of water scarcity and unsustainable blue water consumption. As such, this sensitivity analysis confirms that the spatiotemporal changes observed in our study are robust to the choice of input datasets.

Crop blue water demand was estimated based on ten uncertainties for China (a), India (b), and the United States (c). The uncertainties include (1) four crop water requirements (CWRs) datasets25,51,52,53; (2) the use of temporally fixed or time-varying monthly CWRs; and (3) two methods of spatial aggregation for CWRs (gridded CWRs were averaged to the county-/district-level either by simple spatial averaging or by using gridded crop-specific harvested areas as weights). The black solid line represents the mean value, and the shaded area is the 95% confidence interval estimated using the bootstrap method (n = 1000).

Discussion

Our study provides important insights into the spatiotemporal evolution of water scarcity in the world’s most populous countries – China, India, and the United States. Our monthly sub-national sector-specific analysis enabled us to identify the locations, seasonal duration, and sectors most tied to blue water scarcity across these nations which are critical to global food and water security. We find that blue water demand continues to grow in all three study countries, and we provide evidence of deepening water scarcity driven in large part by the rising irrigation demand (primarily via expanding irrigated area) of a handful of crops (i.e., rice, wheat, maize, alfalfa) (Figs. 1 and 10). On one hand, the growing magnitude and extent of unsustainable water use is stark and offers worrying prospects for future trends in water sustainability. On the other hand, the fact that a relatively small number of commodities dictate water demand to such a large degree may offer promise for simplifying water sustainability challenges and formulating feasible efforts toward their resolution.

To this end, while the prominent role of crop production in driving water demand and scarcity is certainly expected, our spatially and temporally detailed analysis provides an important step toward linking scientific understanding with sustainable action. By knowing where and when unsustainable water demand is occurring (Figs. 7 and8) and which specific sectors dominate that demand (Figs. 2–5, Figs. S1–S3), it is possible to begin developing targeted, context-specific interventions to improve water sustainability. For instance, approaches such as ours can be combined with remotely sensed (e.g., GRACE) or modeled estimates of water storage to perform crop- or sector-specific attributions of groundwater depletion, which can directly inform refined on-ground actions. Further, our analysis also enabled us to identify the places where unsustainable water demand is increasing most rapidly, providing valuable information for prioritizing locations of intervention (Figs. 7–9, Figs. S4, S5). In particular, our findings on physical water scarcity can facilitate the effective implementation of ‘soft’ economic approaches to addressing water sustainability issues (i.e., allocating limited water resources to high-value uses) while ensuring equitable and fully compensatory benefits sharing among water-reliant actors30. To this end, combining such spatially explicit water information with data on other outcomes can also help to avoid undesirable tradeoffs with other dimensions of sustainability (e.g., food security, climate change, rural development) and enable informed and holistic sustainability decision-making towards meeting stakeholder priorities and achieving multiple SDGs in tandem (e.g., refs. 30,31,32). Further, as the availability of consistent (i.e., incorporating the same assumptions and input information) time-varying data continues to increase for the study countries and other nations, our approach can also be utilized to disentangle the roles of human activities and climatic changes in contributing to conditions of water scarcity.

Numerous solutions exist to ameliorate the widespread and intensifying patterns of blue water scarcity that we observed33. These strategies include employing market-based water rights schemes34, transfers from water-abundant to water-scarce regions (e.g., ref. 35), switching to alternative water supplies (e.g., stormwater, treated wastewater), installing low-flow appliances, implementing water use restrictions, offering incentives for reduced water use, and promoting educational programs33. For crop production specifically, solutions include pairing improved irrigation efficiencies and reduced conveyance losses36 with water consumption caps37, expanding irrigation exclusively in water-abundant areas10, targeted fallowing28,38, and planting of less water-intensive and higher yielding crops30,39,40,41. Other solutions further down the food supply chain – including increasing imports from water-abundant regions30, reducing food waste42, shifting diets43, and promoting circularities44 – can also lead to changes to less water-intensive crop production patterns and choices. While many of these solutions have been attempted by a variety of context-specific intervention programs within our study countries, these solutions are typically implemented in isolation (e.g., within a single sub-basin or river reach by an individual agency) and often do not account for the hydrologic interconnectivity of interventions and their potentially cascading influences on other parts of a river basin. As such, isolated or siloed interventions can act at counter-purposes to one another and potentially exacerbate water scarcity issues in other sub-basins. Conversely, by taking a multi-scalar and multi-temporal view of water scarcity challenges, our approach can enable more integrated and coordinated intervention planning that maximizes co-benefits and minimizes tradeoffs for all water users and the environment across diverse geographic scales. Such approaches to evaluating solutions must also be accompanied by broader investments in water infrastructure as well as integrative policies and decision processes30.

While a growing body of research points to deep opportunities for improving the sustainability of water use, it is clear from our findings that the societal priorities dictating where and how water is consumed continue to view it as an unlimited resource. To this end (and as our study demonstrates), robust measurement, modeling, and accounting will be fundamental to resolving these tradeoffs between water and other societal outcomes and ultimately supporting science-based decision-making and water resource governance45. Our work also demonstrates that efforts to improve water sustainability in the study countries have largely fallen short of reversing these undesirable trends and that large-scale coordinated interventions are urgently needed in order to realize substantial positive change and to meet water sustainability targets. Close evaluation of the success of several more recent efforts in the studied countries (e.g., California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (2014); China’s Three Red Lines (2012); India’s revised National Water Policy (2012; 2020)) can also shed light on whether these nations have been able to overcome past policy shortcomings. In addition, it is necessary to understand the social, political, and economic factors that influence the decisions of water users and contribute to choices that diverge from the most sustainable pathways. Such insights are essential for moving beyond simply the identification of water sustainability solutions and toward their real-world adoption and implementation.

Methods

Sustainable water consumption was calculated based on two components. First, monthly total water availability data were utilized to determine environmental flow requirements (EFRs) and the amount of blue water available for sustainable consumption within each sub-basin. Crop-specific irrigated areas were then combined with estimated crop water requirements to determine the volume of blue water demand for each crop. Blue water demands from agriculture and other societal sectors (domestic, electricity generation (i.e., cooling of thermal power plants), livestock (i.e., watering and cleaning), manufacturing, and mining water consumption) were then combined to estimate total human demand in each study country.

Irrigated area statistics

Crop-specific district-level irrigated area (IA) statistics for India for the years 1966–2015 were taken from the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics22. Crop-specific county-level irrigated area statistics for the United States for the years 1980-2017 were taken from the United States Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service23. County-level crop-specific sown area statistics for China for the years 1980–2015 were taken from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China / Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences21. The crops for which IA statistics were available account for 83% (India), 97% (United States), and 93% (China) of each country’s harvested area18 (Table S1). For India, isolated (often single-year) data gaps were linearly interpolated. For the United States, agricultural census data are collected in years ending with a 2 and 7 (i.e., 1982, 1987, 1992, 1997, 2002, 2007, 2012, and 2017). IA values for the intervening years were estimated by linear interpolation. While survey data were also available for many of the intervening years, notable discrepancies between census and survey data – potentially due to differences in sample size and methodology – prevented their use. For China, county-level IA statistics were not disaggregated by crop. To resolve this, we used gridded (5 arcminute) crop-specific maps of irrigated area and harvested area for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, and 202024 to estimate the fraction of irrigated area to harvested area for each crop within each county. These county-level fractions were then interpolated based on the growth rate of effective irrigated area of cultivated land to provide a county-level irrigated area fraction for each crop in each year for which county-level crop-specific sown area was available (i.e., 1980–2015).

Total water availability estimates

Renewable water availability was calculated as the total blue water availability minus the environmental flow requirement, where the total blue water availability accounts for both surface and subsurface runoff, including the water in rivers, lakes, and aquifers46,47. Estimates of total blue water availability (i.e., runoff) for the years 1980 through 2015 came from eleven global hydrological models (CLASSIC, CWatM, ELM-ECA, H08, HydroPy, JULES-ES-VN6P3, JULES-W2, MIROC-INTEG-LAND, ORCHIDEE-MICT, VISIT, WaterGAP2-2e) from Phase 3a of the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project48. These model outputs account for varying direct human forcing (e.g., dams and reservoirs) but do not include information on interbasin transfers (due to a lack of available comprehensive data on water transfers across the study countries). As such, the estimated volumes of water availability used in this study may differ to a certain extent in the source and destination locations of large-scale water transfers. Original gridded (0.5° resolution) data for monthly total water runoff (units: kg*m−2/s) were converted to monthly availability estimates (i.e., runoff depth) (units: mm/month) and then were spatially averaged to the sub-basin scale - with 1211 sub-basins in China, 349 in India, and 883 in the US. The choice of sub-basins as the unifying geographic unit of analysis in our study (for both water availability and water demand) was motivated by their hydrological coherence and their common use in multiple previous national and global assessments of water demand and water scarcity8,28,38,49. Following Brauman et al. 8, for reasons of data reliability, sub-basins smaller than 1000 km2 were not considered in the analysis, thereby excluding small coastal watersheds as well as unconnected mountain/interbasin watersheds. This produces some gaps in the resultant maps (see e.g., western portions of China, India, and the US). Following this data cleaning, the volume of total blue water availability (m3) within each sub-basin was then calculated as the product of the water runoff depth values and their respective sub-basin area. The main results of the study are reported using the average values of all eleven hydrological models (Figs. 1, 6–9), with uncertainties depicted in Fig. S7.

Allocations for environmental flow requirements (EFRs)

EFRs refer to the water (quantity, quality, and timing) required to support the health of aquatic ecosystems and the livelihoods that depend on them19,20. EFRs were calculated at monthly time steps using the range-of-variability approach (RVA), which has been widely used for national- to global-level EFR estimation (e.g., refs. 10,50). The main advantage that this approach offers in the context of the present study is its ability to take into account water availability across a wide range of scales and flow volumes. This is particularly useful in cases where ecological datasets (which are necessary to assess a river’s ecological condition/degradation) are not comprehensively available. This RVA approach thus offers a flexible (i.e., applicable at local to global scales) yet standardized approach to account for differences in characteristics (and the resulting range/heterogeneity in realistic EFRs) between the thousands of sub-basins that we assess. This approach was used to calculate renewable blue water availability (r) in each sub-basin s as:

where as is the total blue water availability and ηx is the xth percentile total water availability, based on the ranked distribution of total monthly blue water availability across all sub-basins within a country19.

Blue crop water requirements (CWRs) and demand

Information on actual water withdrawals or pumping rates is not comprehensively available across the study countries, and estimations of blue CWRs provide the best alternative in examining the water needs of farmers across the country. Blue CWR represents a crop’s consumptive water demand in excess of what is provided through precipitation and is only used in calculations of consumptive water demand within irrigated areas. In reality, farmers with access to irrigation may not be able to fully meet the irrigation water demand of their crops, as limited by pumping rates and irrigation sources. As such, the blue CWR values used here likely represent an overestimation relative to actual water consumption. Blue crop water requirement estimates came from four different datasets: monthly gridded (5 arcminute) crop-specific blue CWRs from the WATNEEDS model25, monthly gridded (5 arcminute) crop-specific blue CWRs from Demeke and Mekonnen51, monthly country-level CWRs from the WaterCROP model52, and annual country-level CWRs from Mekonnen and Hoekstra53. Monthly county-level crop blue water demand (CWD) volumes were then calculated for each crop as the product of the spatially averaged county-level blue CWRs and the county-level irrigated areas (IA). Following Richter et al. 38, county-level CWDs were then allocated proportionally to sub-basins based on spatial overlap, with the assumption that water demand is equally distributed across a county. For instance, if a sub-basin spatially overlapped with county A by 30% and county B by 70%, then the crop blue water demand of this sub-basin is the sum of 30% of county A’s crop blue water demand and 70% of county B’s crop blue water demand.

Blue water demands of other societal sectors

To account for other societal water demands, we used data from a global gridded (0.5° resolution) database on monthly blue water consumption (i.e., evapotranspiration; not withdrawals) for domestic use, electricity generation (i.e., cooling of thermal power plants), livestock, manufacturing, and mining consumption26. For each pixel and month covering the years 1971 through 2010, this dataset reports sector-specific depths of consumption (mm/month) and then extrapolated linearly to 2015 based on the average annual growth rate for 2008–2010. Grid cells were spatially averaged to the sub-basin scale, and this sub-basin average depth was then multiplied by the respective sub-basin’s area to produce a monthly sector-specific volume (m3) for each sub-basin.

Blue water scarcity and unsustainable demand

We evaluated total blue water demand and availability as there is no comprehensive or sufficient information on sector- or crop-specific blue water sourcing (i.e., surface or groundwater). Because we are unable to disaggregate by source, unsustainable water demand in a location may lead to streamflow depletion, reservoir drawdown, groundwater depletion, or a combination thereof depending on the water sources utilized. The final time period evaluated for China, India, and the United States was 1980–2015. For each month and sub-basin, we calculated a blue water scarcity (BWS) ratio as the summed blue water demand from agriculture and other societal sectors divided by the renewable blue water availability (r) which accounts for EFRs (following e.g., refs. 8,10). When the resultant ratio exceeded 1.0, we assumed that the sub-basin was in a condition of physical blue water scarcity. Unsustainable blue water demand was estimated as the summed blue water demand from crop production and other societal sectors subtracted from the renewable blue water availability (r). When the resultant difference was less than 0, it was assumed that the societal demands within the sub-basin exceeded the renewable available blue water resources and were being utilized unsustainably (i.e., contributing to groundwater or streamflow depletion).

Sensitivity assessment of total and unsustainable blue water demand estimates

For all aspects of our analysis for which alternative datasets or methodologies exist, we quantitatively estimated the sensitivity of our estimates of total and unsustainable blue water demand. Throughout our approach, we evaluated sensitivity as it relates to: (1) the choice of water availability dataset; (2) the choice of crop water requirement dataset; (3) the method of spatial aggregation for CWRs; and (4) the use of temporally fixed or time-varying monthly crop water requirements. Other entry points for sensitivity into our analysis that could not be evaluated were crop-specific irrigated areas (for which there is no independent alternative source of spatially disaggregated time series information) and non-crop sector-specific blue water demand (for which there is no alternative dataset that is spatiotemporally disaggregated and geographically consistent). For total water availability, we considered estimates from eleven different global hydrological models (CLASSIC, CWatM, ELM-ECA, H08, HydroPy, JULES-ES-VN6P3, JULES-W2, MIROC-INTEG-LAND, ORCHIDEE-MICT, VISIT, WaterGAP2-2e) from phase 3a of the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project48. For blue crop water requirements, we considered estimates from four different process-based models25,51,52,53. For spatial aggregation of CWRs, gridded CWRs were averaged to the county-/district-level either by simple spatial averaging or by using gridded crop-specific harvested areas as weights24. Combining county-level monthly blue crop water requirements with irrigated areas allowed us to estimate monthly blue water demand; we made these estimations of monthly blue water demand using either temporally fixed (i.e., applying 1998–2002 average CWRs for each study year) or time-varying monthly crop water requirements. Altogether, this suite of sensitivity considerations produced 88 unique sets of estimates for total and unsustainable blue water demand (Fig. 10, Figs. S6–S8). We present the average values (Figs. 1–9) and uncertainties (Fig. 10) across all combinations of input datasets in the main results. Across all of these, we found that our estimates of spatial patterns and temporal trends of unsustainable blue water demand and water scarcity remained consistent and that estimated volumes of total and unsustainable blue water demand were most sensitive to the input data of annual country-level blue crop water requirements from Mekonnen and Hoekstra53, which overlooks the seasonality of CWR, resulting in an underestimation of unsustainable blue water demand compared to calculations based on monthly grid-level CWR datasets. In addition, India also displayed notable sensitivity to the temporally fixed monthly crop water requirements from Chiarelli et al. 25, with the resulting unsustainable blue water demand estimates being higher than other input combinations (Fig. S8).

Validation of estimates

Given the ensemble approach (incorporating all available combinations of input datasets) and the comprehensive sensitivity testing conducted in this study, the estimates for blue crop water requirements, blue water demand, and total water availability were validated. The validation indicates that these estimates provide a reliable assessment and quantification of the evolution of water demands and water scarcity in the study countries. For the validation of blue crop water requirements, the estimates were compared to available studies utilizing direct field measurements across the three study countries, showing good agreement (Table S2). Additionally, all crop-specific parameters in crop water requirement models (e.g., crop coefficients) were empirically determined through direct field measurements. For the validation of blue water demand, the estimates were compared to those reported by official statistics and other literature (Fig. S9), showing good agreement across all study countries. The differences from the official statistics are likely due to the statistical methodology, as the irrigation water requirements from statistical reports were calculated based on the water withdrawals (not consumption) at the intake points of the irrigation districts, which cannot precisely identify which crops the irrigation water is used for. Therefore, our estimated blue water consumption for most crops is lower than what is reported in national statistics, which are calculated based on coarser and less refined information. For the validation of total blue water availability, the eleven hydrological models’ simulations are validated with observations (Table S3), and the comparison with official estimates indicates that these models accurately capture temporal changes (Fig. S10). For the validation of crop-specific irrigated areas in China, a multi-step comparison process was conducted. First, the country-level crop harvested irrigated area estimates were compared with AQUASTAT values (Fig. S11). Second, a county-level comparison was conducted between the estimated total irrigated area of crops and the effective irrigated area of cultivated land. When the total irrigated area of crops exceeds the effective irrigated area of cultivated land, it indicates multiple cropping in that county (Fig. S12). These comparisons, which show strong agreement, indicate that the estimates of county-level crop-specific irrigated areas are reliable and accurate over time.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings in this study are available within the paper. The crop-specific irrigated area statistics, blue crop water requirement data, and societal water demand data can be found in the references. The global gridded water availability data from ISIMIP3a are available from https://www.isimip.org/.

Code availability

All the codes that contribute to the data preparation and analysis will be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020 (UN DESA, 2020).

Hoekstra, A. Y. & Mekonnen, M. M. The water footprint of humanity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 3232–3237 (2012).

Siebert, S. et al. A global data set of the extent of irrigated land from 1900 to 2005. Hydr. Earth Sys. Sci. 19, 1521–1545 (2015).

Xie, Y. & Lark, T. J. Mapping annual irrigation from Landsat imagery and environmental variables across the conterminous United States. Remote Sens. Environ. 260, 112445 (2021).

Flörke, M., Schneider, C. & McDonald, R. I. Water competition between cities and agriculture driven by climate change and urban growth. Nat. Sustain. 1, 51–58 (2018).

Rosa, L., Rulli, M. C., Davis, K. F., & D’Odorico, P. The water-energy nexus of hydraulic fracturing: a global hydrologic analysis for shale oil and gas extraction. Earths Future 6, 745–756 (2018).

Ercin, A. E. & Hoekstra, A. Y. Water footprint scenarios for 2050: A global analysis. Environ. Int. 64, 71–82 (2014).

Brauman, K. A., Richter, B. D., Postel, S., Malsy, M. & Flörke, M. Water depletion: an improved metric for incorporating seasonal and dry-year water scarcity into water risk assessments. Elementa 4, 000083 (2016).

Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2, e1500323 (2016).

Rosa, L. et al. Closing the yield gap while ensuring water sustainability. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 104002 (2018b).

Wada, Y. et al. Global depletion of groundwater resources. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L20402 (2010).

Haddeland, I. et al. Global water resources affected by human interventions and climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3251–3256 (2014).

Tuninetti, M., Tamea, S. & Dalin, C. Water debt indicator reveals where agricultural water use exceeds sustainable levels. Water Resour. Res. 55, 2464–2477 (2019).

Rosa, L., Chiarelli, D. D., Rulli, M. C., Dell’Angelo, J. & D’Odorico, P. Global agricultural economic water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz6031 (2020).

Hoekstra, A. Y., Mekonnen, M. M., Chapagain, A. K., Mathews, R. E. & Richter, B. D. Global monthly water scarcity: blue water footprints versus blue water availability. PLoS ONE 7, e32688 (2012).

Degefu, D. M. et al. Mapping monthly water scarcity in global transboundary basins at country-basin mesh based spatial resolution. Sci. Rep. 8, 2144 (2018).

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision (UN DESA, 2019)

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT database. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (FAO, 2021).

Pastor, A. V., Ludwig, F., Biemans, H., Hoff, H. & Kabat, P. Accounting for environmental flow requirements in global water assessments. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 5041–5059 (2014).

The Brisbane Declaration “Environmental flows are essential for freshwater ecosystem health and human well-being,” 10th International River Symposium and International Environmental Flows Conference (Brisbane, QLD). https://www.conservationgateway.org/ConservationPractices/Freshwater/EnvironmentalFlows/MethodsandTools/ELOHA/Pages/Brisbane-Declaration.aspx (2007).

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China / Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. County-Level Agricultural Statistics 2001-2015 (MoA/CAAS, 2018).

International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics. Village Dynamics in South Asia Meso Level Data for India: 1966–2015. http://data.icrisat.org/dld/ (ICRISAT, 2020).

United States Department of Agriculture. National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA) http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov (USDA, 2021).

International Food Policy Research Institute. Global Spatially-Disaggregated Crop Production Statistics Data https://www.mapspam.info/ (IFPRI, 2019).

Chiarelli, D. D. et al. The green and blue crop water requirement WATNEEDS model and its global gridded outputs. Sci. Data 7, 273 (2020).

Huang, Z. et al. Reconstruction of global gridded monthly sectoral water withdrawals for 1971–2010 and analysis of their spatiotemporal patterns. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 2117–2133 (2018).

Müller Schmied, H. et al. Sensitivity of simulated global-scale freshwater fluxes and storages to input data, hydrological model structure, human water use and calibration. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 3511–3538 (2014).

Richter, B. D. et al. Alleviating water scarcity by optimizing crop mixtures. Nat. Water 1, 1035–1047 (2023).

Mehta, P. et al. Half of 21st century global irrigation expansion has been in water stressed regions. Nat. Water 2, 254–261 (2024).

Grafton, R. Q., Williams, J. & Jiang, Q. Possible pathways and tensions in the food and water nexus. Earths. Future 5, 449–462 (2017).

Davis, K. F. et al. Assessing the sustainability of post-Green Revolution cereals in India. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 25034–25041 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Quantitative assessment of agricultural sustainability reveals divergent priorities among nations. One Earth 4, 1262–1277 (2021).

Marston, L. et al. Reducing water scarcity by improving water productivity in the United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 094033 (2020).

Debaere, P. et al. Water markets as a response to scarcity. Water Policy 16, 625–649 (2014).

Zhang, Q. The South‐to‐North Water Transfer Project of China: environmental implications and monitoring strategy 1. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 45, 1238–1247 (2009).

Jägermeyr, J. et al. Water savings potentials of irrigation systems: global simulation of processes and linkages. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 3073–3091 (2015).

Grafton, R. Q. et al. The paradox of irrigation efficiency. Science 361, 748–750 (2018).

Richter, B. D. et al. Water scarcity and fish imperilment driven by beef production. Nat. Sustain. 3, 319–328 (2020).

Davis, K. F. et al. Alternative cereals can improve water use and nutrient supply in India. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao1108 (2018).

Yang, X. et al. Diversified crop rotations enhance groundwater and economic sustainability of food production. Food Energy Secur. 10, e311 (2021).

Xie, W. et al. Crop switching can enhance environmental sustainability and farmer incomes in China. Nature 616, 300–305 (2023).

Kummu, M. et al. Lost food, wasted resources: global food supply chain losses and their impacts on freshwater, cropland, and fertiliser use. Sci. Total Environ. 438, 477–489 (2012).

Jalava, M., Kummu, M., Porkka, M., Siebert, S. & Varis, O. Diet change—a solution to reduce water use? Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 074016 (2014).

D’Odorico, P. et al. The global food-energy-water nexus. Rev. Geophys. 56, 456–531 (2018).

Garrick, D. E. et al. Valuing water for sustainable development. Science 358, 1003–1005 (2017).

Rosa, L. et al. Potential for sustainable irrigation expansion in a 3 °C warmer climate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 29526–29534 (2020).

Rosa, L. et al. Regional irrigation expansion can support climate-resilient crop production in post-invasion Ukraine. Nature Food 5, 684–692 (2024).

Frieler, K. et al. Scenario setup and forcing data for impact model evaluation and impact attribution within the third round of the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP3a). Geosci. Model Dev. 17, 1–51 (2024).

Davis, K. F., Rulli, M. C., Seveso, A. & D’Odorico, P. Increased food production and reduced water use through optimized crop distribution. Nat. Geosci. 10, 919–924 (2017).

Damerau, K. et al. India has natural resource capacity to achieve nutrition security, reduce health risks and improve environmental sustainability. Nat. Food 1, 631–639 (2020).

Demeke, B. W. & Mekonnen, M. M. The global water footprint of crop production from 1972 to 2018. In preparation.

Tuninetti, M., Tamea, S., D’Odorico, P., Laio, F. & Ridolfi, L. Global sensitivity of high‐resolution estimates of crop water footprint. Water Resour. Res. 51, 8257–8272 (2015).

Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 15, 1577–1600 (2011).

Acknowledgements

L.M. acknowledges the support of the National Science Foundation grant CBET-2144169. K.F.D. and L.M. were supported by the United States Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture grant 2022-67019-37180. M.C.R. and D.D.C. are supported by the NEXUS NESS project founded by the PRIMA Programme, an Art.185 initiative supported and funded under Horizon 2020, the European Union’s Framework Programme for Research and Innovation, with grant agreement no. 2042. D.D.C. was supported by Premio Florisa Melone. Q.D. and W.X. were supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (grant nos. 72261147472, 72348003, 72061147001, and 42377467), Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (grant no. 2023YFD2300301) and National Social Science Foundation of China (grant no. 21BJY013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.F.D. designed the study and coordinated the research; Q.D., T.S., Y.Z.A., D.D.C., B.D., L.M., P.M., M.M., M.C.R., and M.T. provided and collected the data; Q.D., T.S., T.A., W.X., and K.F.D. performed the analyses; T.S. and K.F.D. wrote the first draft; all authors contributed to interpreting the results and writing and revising the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks R. Quentin Grafton, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, Q., Sharretts, T., Ali, T. et al. Deepening water scarcity in breadbasket nations. Nat Commun 16, 1110 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56022-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56022-6

This article is cited by

-

Child diet diversity and irrigation expansion in the global south

Nature Sustainability (2025)