Abstract

Solar-driven, selective biomass hydrogenation is recognized as a promising route to renewable chemicals production, but remains challenging. Here, we report a TiO2 supported Cu single-atom catalyst with a four-coordinated Cu1−O4 structure, which can be universally applied for solar-driven production of various renewable chemicals from lignocellulosic biomass-derived platform molecules with good yields using green methanol as a hydrogen donor, to address this challenge. It is significant that the biomass upgrading driven by natural sunlight on a gram scale demonstrates the great practical potential. By combining in situ soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy with theoretical calculations, we successfully identify the dynamic evolution of Cu sites along with the biomass hydrogenation and methanol oxidation, where the tandem process is enabled by the photogenerated electrons and holes to complete a chemical cycle. The concept of solar-driven biomass hydrogenation proposed here provides an efficient and sustainable methodology for the sustainable production of renewable chemicals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

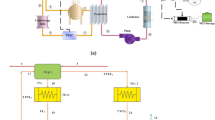

Biomass is the largest renewable carbon resource on earth and can be widely used to produce renewable fuels and chemicals through suitable conversion pathways, achieving more sustainable lifestyles, economies and societies1,2,3. One of the most important strategies is the hydrodeoxygenation of biomass and biomass-derived platform molecules to improve both the sustainability and economic visibility due to their rich oxygen content compared to petrochemical feedstocks4. Traditional biomass upgrading via thermal-driven hydrogenation is an energy-intensive and hazardous process, typically requiring harsh reaction conditions (e.g., high temperature, pressurized H2), precious metal catalysts and expensive reactors (Fig. 1). In addition, the selectivity of the target product is difficult to control5. Selective hydrogenation of biomass and biomass-derived platform molecules under mild conditions therefore remains a major challenge.

Recently, electro-driven hydrogenation has attracted increasing attention due to the advantages of low energy consumption, moderate operating conditions and the use of water as a hydrogen source6. However, the high overpotential, low current density and unsatisfactory target product selectivity limit its further development. In contrast, solar-powered technology is a cost-effective and sustainable approach that can convert inexpensive and readily available liquid hydrogen carriers such as methanol to produce hydrogen7,8, which may be further used for biomass hydrogenation to manage the circular hydrogen economy. Undoubtedly, the renewability of hydrogen source is a highly important factor in the development of renewable chemical production methods, alongside biomass and solar energy. However, it should be noted that the high calorific value and reactivity of hydrogen inevitably lead to additional transportation/production costs and safety risks9. With the rapid development of green electricity, green methanol-related industries have entered the fast lane10,11, and thus selective hydrogenation using green methanol as an in situ hydrogen source will be an ideal approach to the production of renewable chemicals12. To this end, there is a strong demand for solar-driven production of renewable chemicals via biomass hydrogenation using green methanol as a hydrogen donor under much milder conditions. Solar-driven synthesis also has great potential to control reaction activity and selectivity by exploiting photogenerated electrons and holes13,14. For example, Wu et al. reported that TiO2 nanocrystals selectively photocatalyzed the hydrogenation transformations of biomass-derived furfural (FAL) and vanillin (VAL) into the corresponding alcohols and coupling products using methanol as a hydrogen donor15. However, it still remains a major challenge for the selective production of renewable chemicals due to the severe recombination of photogenerated electrons/holes and their strong redox ability, which requires the development of efficient and selective catalysts.

The key to the catalyst development is the design of catalytically active sites. In principle, such a tandem solar-driven hydrogenation reaction system using green methanol as a hydrogen donor usually requires multiple active sites to accommodate the multi-step sequential reactions12,16,17. Such a design is even more challenging in the case of solar-driven reactions, where the active sites tend to undergo complex dynamic evolution under operating conditions18,19,20,21. Intuitively, in situ characterization techniques, which can be performed under reaction conditions and detect a wide range of substrates detection, may provide important mechanistic clues22,23. Soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy (sXAS) is one such technique that can accurately detect the active centers under reaction conditions24, but has not been fully explored for the rational design and in situ analysis of catalytically active sites in complex tandem reactions.

Here, we report the design of a catalyst with Cu single atoms (SAs) supported on TiO2 nanosheets (denoted as CuSAs-TiO2), having a four-coordinated Cu1−O4 structure, for the highly efficient and selective solar-driven hydrogenation of various biomass-derived platform molecules to high-value renewable chemicals using green methanol as a hydrogen donor under mild reactions. For the typical hemicellulose-derived FAL hydrogenation, the yield rate of furfuryl alcohol (FOL) is up to 34 mol h−1 molCu−1 with desirable selectivity of >99% in a photochemical flow reactor. The gram-scale hydrogenation reaction under the natural sunlight irradiation further demonstrates the practical potential of this catalyst. By combining advanced in situ sXAS with theoretical calculations, we directly identify the dynamic evolution of the valence state of Cu single sites. Briefly, the Cu2+ over CuSAs-TiO2 is first pre-activated to Cu+ by a photogenerated electron, and then Cu+ captures a hole to Cu2+ for the methanol oxidation to active hydrogen and then back to Cu+ for the FAL hydrogenation. Based on this dynamic evolution, the photogenerated electrons and holes are utilized synchronously via the tandem reaction. This work provides a methodology for the highly efficient and sustainable biomass hydrogenation to renewable chemicals based on a novel understanding of the dynamic evolution process.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterizations of CuSAs-TiO2

We first synthesized the Cu SAs supported on ultrathin TiO2 nanosheets with (001) exposed facet using a one-pot hydrothermal method (Supplementary Fig. 1), and the mass loading of Cu was determined to be 1.2 wt.% through inductively coupled plasma−mass spectrometry (ICP−MS) (Supplementary Table 1). As reference samples, bare TiO2 nanosheets with (001) exposed facet, TiO2 nanosheets with both Cu single atoms and nanoclusters (CuSAs+NCs-TiO2), and TiO2 nanosheets with Cu nanoparticles (CuNPs-TiO2) were also synthesized via the same method. The Cu contents were determined to be 3.6 and 7.5 wt.% for CuSAs+NCs-TiO2 and CuNPs-TiO2, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirms the successful synthesis of anatase TiO2 nanosheets (PDF #99-0008) (Supplementary Fig. 2), while the introduction of Cu species does not affect the crystal structure of the TiO2 supports. No characteristic peaks of Cu species can be observed for CuSAs-TiO2 and CuSAs+NCs-TiO2, indicating the high dispersion of copper species. In comparison, the CuNPs-TiO2 catalyst exhibits weak XRD diffraction peaks at 43.3 and 50.4° attributed to metallic Cu (PDF #99-0034).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images show the ultrathin nanosheet morphology with an average size of ~20 nm for the TiO2 and CuSAs-TiO2 catalysts (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). Furthermore, the high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image (Supplementary Fig. 4b) reveals that this nanosheet structure predominantly exposes the (001) facet. The elemental mappings of CuSAs-TiO2 by energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy further confirm the presence and uniform distribution of Cu, O and Ti elements across the entire nanosheets (Supplementary Fig. 5). To visualize the presence of Cu SAs in the CuSAs-TiO2, aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC HAADF-STEM) was employed to characterize the sample (Fig. 2b). Indeed, the Cu species is present in the form of SAs, which are marked with yellow circles. In contrast, the Cu nanoclusters (NCs) with a spacing of 0.21 nm corresponding to Cu (111) planes are identified on CuSAs+NCs-TiO2 catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 6). By further increasing the Cu loading, obvious Cu nanoparticles (NPs) are observed for CuNPs-TiO2 (Supplementary Fig. 7), in agreement with the XRD results (Supplementary Fig. 2). As such, the different forms (SAs, NCs and/or NPs) of Cu species supported on TiO2 nanosheets can be easily controlled by adjusting the copper content. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms indicate a larger specific surface area for CuSAs-TiO2 (83.7 m2 gcat−1) with a pore size of 30.3 nm (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Table 2) than those of pure TiO2 (76.9 m2 gcat−1) and CuSAs+NCs-TiO2 (51.6 m2 gcat−1), providing abundant mass transfer channels for catalytic reactions.

a TEM and b AC HAADF-STEM images of CuSAs-TiO2 catalyst. Spots in the yellow circles are single copper atoms. c Cu 2p XPS spectra for CuSAs-TiO2 and CuSAs+NCs-TiO2. d Normalized Cu K-edge XANES spectra for CuSAs-TiO2, Cu foil, Cu2O and CuO. Inset is the partial enlarged detail. e Cu K-edge EXAFS spectra in R space for CuSAs-TiO2 and standards. f Wavelet transform analysis of the first coordination shell for CuSAs-TiO2, Cu foil and CuO. g Cu K-edge EXAFS (points) and curve fit (line) for CuSAs-TiO2, shown in R-space. The data are k3-weighted and not phase-corrected. Inset is the optimized structure of CuSAs-TiO2. Color code: Cu (blue), Ti (azure) and O (red). h Ti L-edge sXAS spectra for TiO2 and CuSAs-TiO2.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was used to analyze the surface elemental compositions and chemical states of the as-synthesized catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 9). High-resolution Cu 2p spectra and Cu LMM AES spectra of CuSAs-TiO2 show the peaks at 932.6 and 952.3 eV corresponding to Cu+ species (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 10)25, and the small peaks at 934.9 and 954.6 eV can be further assigned to Cu2+ species26. It should be noted that Cu2+ species can be easily reduced to Cu+ under high vacuum due to the bombardment effect of X-ray irradiation, especially when the content of highly dispersed Cu is extremely low27,28. This feature lays a solid foundation for the cyclic regeneration of Cu SAs between different valence states. However, with the increase of Cu loading, Cu species aggregation process significantly reduces the dispersion, thereby slowing down the reduction of partial Cu2+. Meanwhile, the asymmetric peaks in O 1s of CuSAs-TiO2 fit well into two peaks (529.7 and 530.9 eV), corresponding to lattice oxygen species (O lattice) and oxygen vacancies (O defect) (Supplementary Fig. 11)29. This is because the introduction of Cu SAs significantly disrupts the pristine TiO2 lattice via the Jahn-Teller effect, further increasing the concentration of oxygen vacancies within the catalyst30.

We further employed X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) to elucidate the form and local coordination environments of Cu SAs in CuSAs-TiO231. The XANES spectra reveal that the absorption edge position of CuSAs-TiO2 is close to CuO (Fig. 2d), suggesting that the valence state of Cu SAs is close to +2. The Fourier-transformed EXAFS (FT- EXAFS) in R space shows that the primary peak at ~1.52 Å is attributed to the nearest shell coordination of Cu−O bond, and the CuSAs-TiO2 does not show a prominent peak at the position of Cu−Cu bond (~2.24 Å) (Fig. 2e), excluding the existence of metallic Cu NPs32. The minor scattering peak at ~2.57 Å can be attributed to Cu−O−Ti coordination in the second shell33. Moreover, wavelet transform was also used to identify the atomic dispersion of the Cu atoms in visualization. As shown in Fig. 2f, the difference of intensity maximum in the wavelet transform images between CuSAs-TiO2 and Cu foil sample (~1.52 Å vs ~2.23 Å) also strongly confirms that Cu species are atomically dispersed in CuSAs-TiO2. In addition, the wave vector (k) is also a key to distinguish different coordination atoms around Cu. Compared with Cu foil, the strongest oscillation of CuSAs-TiO2 in k space occurs in the low k part and is close to CuO, indicating that Cu is coordinated by atoms with smaller atomic number (i.e., O atoms) rather than other Cu atoms. Furthermore, the optimal fitting results for CuSAs-TiO2 suggest that the main coordination originates from four Cu−O bonds, with an average bond length of ~1.93 Å (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13, and Supplementary Table 3). Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra also show the strong signal of Cu2+,21, consistent with the XANES results (Supplementary Fig. 14).

To elucidate the electronic structure, sXAS was used to characterize the TiO2 and CuSAs-TiO2. Figure 2h shows the Ti-L2 and Ti-L3 X-ray absorption fine structure normalized from 455 to 475 eV. The Ti-L2 edge is situated on the higher energy side (Ti 2p1/2 → Ti 3 d), while the Ti-L3 edge is located on the lower energy side (Ti 2p3/2 → Ti 3 d). Due to the octahedral crystal field in the TiO2 crystal, the Ti L2,3 peaks are further split into t2g and eg orbitals. The peaks at 459.8 and 461.6 eV in the Ti L3 edge can be assigned to the t2g and eg orbitals of Ti 3 d, respectively34. Notably, the t2g and eg orbital peaks of CuSAs-TiO2 are higher than those of pure TiO2, indicating that the electron filling degree of Ti 3 d orbital is reduced, leading to the generation of Tiδ+ (δ > 4) center with lower electron density7,32. The formation of these electron-deficient Ti centers, together with the oxidation state for Cu SAs slightly lower than +2, demonstrates electron donation from the coordinated Ti atoms to Cu SAs as a result of the strong electronic interaction in the Cu−Ti dual-metal coordination. As revealed by the O K-edge spectra, the peaks at 533.0 and 535.6 eV correspond to electron excitations from the 1s to the 2p states, respectively, which are hybridized with t2g and eg states in the Ti 3d orbitals (Supplementary Fig. 15)33. Taken together, the results indicate that the Cu SAs are the isolated atoms that occupy the lattice position of Ti and are coordinated with O, and that the strong electronic interactions between Cu and adjacent Ti atoms are present. In addition, the band structures of the samples were investigated using UV–vis–NIR diffuse reflectance spectroscopy and synchrotron radiation photoemission spectroscopy (SRPES) (Supplementary Figs. 16–19). It is found that the introduction of Cu species alters the valence-band maximum (VBM) and the conduction band minimum (CBM) (Supplementary Figs. 20–22), resulting in a modification of the band structure, which is mainly due to the strong interactions between the TiO2 support and the Cu SAs.

Catalytic properties of CuSAs-TiO2

Upon acquiring the structural information of catalysts, we evaluated their catalytic performance in the light-driven tandem biomass hydrogenation system. In the tandem reaction, the green methanol releases active hydrogen species in situ, which is coupled with typical hemicellulose-derived FAL hydrogenation to a renewable chemical (Supplementary Fig. 23). Using methanol as hydrogen donor, a complete FAL conversion and >99% FOL selectivity can be achieved over the CuSAs-TiO2 catalyst within 4 h under 500 mW cm−2 light irradiation (Fig. 3a). This light-driven hydrogenation performance far exceeds the reported results, especially in terms of selectivity (Supplementary Table 4). In sharp contrast, only 48.5% and 42.9% FAL conversions with 21.7% and >99% FOL selectivity is achieved over TiO2 and CuSAs+NCs-TiO2 catalysts, respectively. This indicates that the single-atom Cu sites can effectively improve the catalytic efficiency and FOL selectivity on the TiO2 support. In addition, Supplementary Fig. 24 shows that the performance of CuSAs-TiO2 is far superior to that of many other transition metal-based SAs, including Ni, Co and Fe-based SAs. As a control, the main product is 2-furaldehyde dimethyl acetal with a 19.5% FAL conversion in the absence of catalyst due to spontaneous aldol condensation between FAL and methanol. In addition, the commercial P25 and CuSAs-P25 only give the 72.2% and 42.4% FAL conversions with 80.1% and 41.4% FOL selectivity under the same conditions, suggesting that the importance of TiO2 nanosheets with (001) exposed facet. To demonstrate the feasibility of practical applications, we carried out a gram-scale synthesis using 1 g FAL as reactant under 500 mW cm−2 light irradiation. Under such conditions, the CuSAs-TiO2 catalyst still retains high catalytic activity and selectivity.

a Catalytic performance of various catalysts in the solar-driven hydrogenation of FAL employing methanol as the hydrogen source under 500 mW cm−2 within 4 h reaction. b Time-dependent performance under 500 mW cm−2 and c Light intensity-dependent performance for the solar-driven FAL hydrogenation reaction over CuSAs-TiO2 within 4 h. Inset in c is thermography image of CuSAs-TiO2 under Xenon lamp irradiation (500 mW cm−2). Other reaction conditions: 10 mg catalyst, 0.25 mmol substrate, 6 mL methanol−water solution, 1 atm Ar. d Cyclic test of solar-driven hydrogenation of FAL over CuSAs-TiO2. Reaction conditions: 20 mg catalyst, 0.5 mmol substrate, 12 mL methanol−water solution, 1 atm Ar, 4 h, 100 mW cm−2. e Catalytic performance of CuSAs-TiO2 under Xenon lamp simulated sunlight and natural sunlight irradiation. This test was conducted in University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui, China (31° 50’ N, 117°15’ E) at August, 2024. Reaction conditions: Left) 10 mg catalyst, 0.25 mmol substrate, 6 mL methanol−water solution, 1 atm Ar, 24 h, 100 mW cm−2 AM1.5; Middle) 10 mg catalyst, 0.25 mmol substrate, 6 mL methanol−water solution, 1 atm Ar, 6 h, sunlight; Right) 200 mg catalyst, ~ 1 g substrate, 450 mL methanol−water solution, 1 atm Ar, 5 days, sunlight. Insets in e are digital photographs of gram-scale reaction system under outdoor sunlight irradiation. f Schematic illustration of the photochemical flow reactor, including reactants supplier, peristaltic pump, homemade reactor and product collector. Reaction conditions: 20 mg catalyst, 0.25 mmol substrate, 6 mL methanol−water solution, 1 atm Ar, 1 h, 500 mW cm−2. g Solar-driven hydrogenation of various biomass-derived platform molecules to renewable chemicals over CuSAs-TiO2 catalyst. Reaction conditions: 10 mg catalyst, 0.1 mmol substrates, 3 mL methanol−water solution, 1 atm Ar, 100 mW cm−2 365 nm LED.

We further systemically investigated the effect of reaction conditions on the optimum CuSAs-TiO2 catalyst. Figure 3b shows that the FAL conversion gradually increases from 36.1% to >99% by prolonging the reaction time from 1 to 4 h under 500 mW cm−2 light irradiation. The FOL selectivity is remained at >99% over the reaction time, indicating the great advantage of solar-driven synthesis. It is worth noting that the activity of such solar-driven tandem hydrogenation strongly depends on the solvent. Control experiments reveal that the addition of water significantly enhances FAL conversion, and a solvent consisting of 76 wt.% methanol and 24 wt.% water is considered to be the optimum solvent (Supplementary Fig. 24). Furthermore, replacing the hydrogen source with other alcohols such as ethanol or isopropanol (Supplementary Fig. 24), results in reduced activity due to the superiority of hydrogen production by methanol reforming.

To confirm the origin of the energy driving the reaction, the reaction was performed under different light sources (Supplementary Fig. 24). It turns out that if the wavelength range of the light is limited to infrared or visible light (400–700 nm), this reaction cannot take place. When the light source is switched to ultraviolet light (<400 nm), the FAL can be completely converted to FOL. Since the light absorption edge is 390 nm according to the UV–vis–NIR diffuse reflectance spectra (Supplementary Fig. 16), the results indicate that this is indeed a typical light-driven hydrogenation reaction. Certainly, the reaction can also proceed smoothly under the 500 mW cm−2 full-spectrum light irradiation. To standardize the reaction system toward practical applications, we therefore mainly used full-spectrum light to drive the FAL hydrogenation using methanol as the hydrogen donor. To exclude the influence of thermal effects on the reaction, the reaction temperature was first confirmed to be ~45 °C using non-contact infrared thermometry and contact thermocouples (Fig. 3c). A thermally driven catalytic reaction was then carried out at a high reaction temperature of 120 °C in the dark, which showed no catalytic activity, demonstrating the importance of light irradiation to the reaction. Increasing the light intensity from 200 to 500 mW cm−2 promotes the corresponding FAL conversion from 55.8% to >99% in a 4 h reaction. We also demonstrate that the introduction of an electron scavenger (carbon tetrachloride, CCl4) into the system completely stops the FAL conversion (Supplementary Fig. 24f). It should be noted that since methanol is a common hole scavenger, the addition of another hole scavenger (triethanolamine, TEOA) slightly inhibits FAL conversion. These results reveal that the photogenerated electrons and holes are jointly involved in the reaction process.

The stability of the catalyst, a key factor for practical applications, was also evaluated at a low conversion. The CuSAs-TiO2 catalyst demonstrates the satisfactory durability over 5 consecutive cycles (Fig. 3d). The TEM, XRD and XPS results show that the reused catalyst remains unchanged in morphology, structure and surface-interface composition after the 5 cycles (Supplementary Figs. 25–27), confirming its superior stability. Moreover, after six months of storage, the catalyst shows no significant loss of catalytic activity compared to the fresh sample, indicating good storage stability. To further demonstrate the potential for practical applications using solar light, we evaluated the catalytic performance under stimulated AM1.5 light and natural solar light. Figure 3e shows that the FAL can be converted to FOL within 24 h under the illumination of stimulated AM1.5 light with an intensity of 100 mW cm−2. Remarkably, the FAL hydrogenation reactions driven by natural solar light, especially for gram-scale synthesis, can be easily achieved with high yields (Fig. 3e), indicating its great industrial application potential. Furthermore, by immobilizing the catalyst within a homemade photochemical flow reactor with arc-shaped flow channels, a high conversion rate of 34 mol h−1 molCu−1 and >99% FOL selectivity was obtained (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 28).

To prove the generality of the biomass conversion and utilization, the typical lignocellulose-derived platform molecules were chosen as the studied reaction substrates for the developed solar-driven synthesis strategy (Fig. 3g). First, the hemicellulose-derived FAL (1a) and 5-methyl furfural (2a) are selectively converted to alcohol products with >99% yields using methanol as hydrogen donor within 0.5 and 1 h under 100 mW cm−2 365 nm LED light irradiation, respectively. Similarly, the cellulose-derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (3a) is hydrogenated to 2,5-dihydroxymethylfuran (3b) with >99% yield within 1 h. In addition to furans, lignin-derived aldehydes and ketones can also be converted into the corresponding products with high activity and selectivity by this synthesis strategy. For example, the lignin-derived VAL (6a) and cyclohexanone (8a) are selectively converted to the corresponding alcohols with >99% yields within 12 and 2 h, respectively. So far, the universal, selective hydrogenation toward a wide spectrum of biomass-derived substrates with high yields under mild reactions has rarely been reported16. Therefore, our solar-driven hydrogenation over CuSAs-TiO2 can feasibly control the activity and selectivity of biomass conversion to produce renewable chemicals with high universality compared to thermal and electro-driven synthesis.

Dynamic evolution of catalytic sites

Interestingly, the color of the CuSAs-TiO2 obviously changes from pale yellow to deep gray under full-spectrum light irradiation (Fig. 4a), and this newly formed metastable intermediate can maintain its stability. Upon re-exposure to air, the sample turns back to its original pale yellow. This suggests a photoinduced reversible valence state transition in CuSAs-TiO2, which is crucial for understanding the dynamic evolution of catalytic sites in light-driven synthesis. To unravel the mechanisms for the light-driven hydrogenation, metal L-edge XANES spectra attributed to transitions from 2p to unfilled 3d orbitals, which are sensitive to the metal oxidation states and can provide valuable information on the oxidation state changes35, were used to study the system. The in situ sXAS offers significant advantages over XPS in that it allows the valence states of elements to be studied under atmospheric conditions, thereby greatly minimizing the influence of reaction conditions on the inherent valence states. Such a technique also allows for the introduction of a wider variety of reactants into the in situ reaction chamber. Considering these inherent advantages of soft X-rays, we for the first time performed in situ sXAS of the Cu L-edge to monitor the dynamic evolution of Cu SAs under real experimental conditions (Fig. 4b, c). As shown in Fig. 4d, in the presence of He, the peak of Cu element in CuSAs-TiO2 is at 930.9 eV, indicating that Cu SAs exist predominantly in the form of +2. Upon light irradiation, the Cu2+ signal gradually decreases and a new Cu+ peak appears at 933.6 eV, which is consistent with the values reported in the literature36,37,38. Although the L3 absorption edge of metallic Cu typically appears at about 933.5 eV, which overlaps with the spectral features of Cu2O, no characteristic fingerprint peak of metallic Cu is observed in the spectra. After the addition of FAL and 76 wt.% methanol−water solution, the Cu2+ signal continues to decrease rapidly while the Cu+ signal increases to a certain value. These results suggest that under initial light irradiation, CuSAs-TiO2 undergoes a pre-activation process in which Cu2+ captures photogenerated electron to Cu+. However, the extent of this change is quite limited. Upon the introduction of the substrates into the chamber, Cu SAs rapidly establish a tandem catalytic system characterized by the stable coexistence of Cu2+/Cu+. To confirm the reusability of the catalyst, oxygen is introduced into the in situ chamber after the reaction, thus resulting in the disappearance of the Cu+ signal and the recovery of the Cu2+ signal to its initial intensity (Fig. 4d), indicating good reusability of the CuSAs-TiO2 catalyst.

a Digital photographs of the color change of the reaction solution before/after irradiation and exposure to air. b Digital photograph of in situ sXAS facility. c Digital photograph of reaction chamber. d In situ Cu L-edge sXAS spectra for CuSAs-TiO2 under different conditions. e In situ EPR spectra of CuSAs-TiO2 during the irradiation and regeneration cycle process. Inset is the partial enlarged detail. f Schematic illustration for the proposed reaction process for dynamic evolution of Cu sites over CuSAs-TiO2. The gray, black and red spheres represent H, C and O atoms, respectively. g In situ DRIFTS spectra for the adsorption and activation of FAL and methanol over CuSAs-TiO2. h In situ EPR spectra for TiO2 and CuSAs-TiO2 under irradiation using DMPO as a spinning trapping agent.

In situ EPR experiments also confirm the dynamic evolution of Cu SAs in CuSAs-TiO2 along with irradiation (Fig. 4e). Before irradiation, the EPR spectrum of CuSAs-TiO2 shows the strong Cu2+ signal. The Cu2+ signal decreases upon exposure to light irradiation and then returns to its original state upon exposure to air. This indicates that EPR-silent Cu+ is formed during the irradiation and then oxidized back to Cu2+ upon exposure to air, which is in good agreement with in situ sXAS results. In addition, the Ti and Cu elements were also examined by using in situ near ambient pressure (NAP)-XPS at lower vacuum levels (Supplementary Figs. 29 and 30). The Ti 2p spectrum shows no significant change under irradiation conditions, while the signal of Cu2+ is weakened and thus the signal of Cu+ is enhanced in the Cu 2p spectrum, indicating that the Cu2+ site on CuSAs-TiO2 has a strong ability to trap electrons7. Taken together, the in situ characterization results lead to the conclusion of a photoinduced activation process. The photoexcited electrons in the TiO2 support are transferred to Cu SAs, and subsequently initiate the variation of the location and components of Cu d-orbital energy levels, thus causing the transformation of Cu2+ to Cu+. This transformation is primarily attributed to the strong interaction between Cu and the TiO2 support, as previously reported7. Furthermore, the one-electron reduction process (i.e., Cu2+ to Cu+) is easier than the two-electron process (i.e., Cu2+ to Cu0), which is crucial for the cycling or self-healing of both Cu2+ and Cu+. After the formation of Cu+, CuSAs-TiO2 establishes a tandem reaction system by cyclically regenerating Cu2+ and Cu+, and then realizes the synchronous utilization of photogenerated electrons and holes.

Figure 4f outlines the proposed reaction process along with the dynamic evolution of Cu sites over CuSAs-TiO2. Methanol molecules are first adsorbed on the surface of CuSAs-TiO2. Under light irradiation, the electrons and holes in TiO2 are excited and transferred for the subsequent reactions. Cu2+ traps an electron to form Cu+ for pre-activation (dotted line), and then the formed Cu+ captures a hole to generate Cu2+ for the methanol oxidation dehydrogenation (solid line). During this process, methanol is dissociated and oxidized to formaldehyde and active hydrogen (*H). The *H is adsorbed on the lattice O atoms near Cu SAs, which is responsible for the color change of CuSAs-TiO2 from pale yellow to deep gray39. Such a process provides a moderate oxidation potential compared to the photoexcited holes in the valance band of TiO2, thereby preventing excessive oxidation of methanol to carbon dioxide. Meanwhile, the electron-rich Cu site (Cu+) has the ability to adsorb and activate FAL with the help of *H to produce FOL. Once the reaction is complete, the catalyst restarts a new cycle of tandem reaction. In short, the closed reaction process consisting of two separate oxidation−reduction half-reactions is successfully established by exploiting the in situ dynamic evolution of Cu2+/Cu+ over CuSAs-TiO2, leading to the high activity and product selectivity (>99%) of solar-driven FAL hydrogenation.

To explore the underlying mechanism of the FAL hydrogenation transformation at the molecular level, we employed synchrotron radiation-based in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier-transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) to track the evolution of surface reactant species during the light-driven tandem reaction. As shown in Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 31, some distinct peaks can be observed under light irradiation after the introduction of FAL and methanol−water mixed solution to the CuSAs-TiO2. Specifically, the peaks at 1604 and 1453 cm−1 are assigned to furan ring breath and C=C characteristic vibrations40. The peaks at 1150–1300 cm−1 are indexed to C-O, C-C stretching vibrations and C-H bending vibration within the furan ring41. It has been reported that the chemical adsorption of the furan ring on the sample surface can lead to the disappearance of the furan ring breath and the C=C bond42. Notably, the peaks between 1150 and 1610 cm−1 gradually increase with time, demonstrating no chemical adsorption of furan ring on CuSAs-TiO2 surface. The chemisorption peak corresponding to the C=O group of FAL is situated at 1667 cm−1. This suggests that the C=O group undergoes linear adsorption via the η1(O)-aldehyde configuration, which is subsequently activated over CuSAs-TiO243. Therefore, we propose that FAL is adsorbed on CuSAs-TiO2 only through vertical configuration, which is conducive to the selective hydrogenation of FAL to produce FOL. As the time increases, the vibration signal of C=O gradually decreases until it disappears. Concurrently, three new bands appear that can be attributed to the C−O band of FOL (1102 cm−1) and the C=O bond of HCHO (1741 and 1770 cm−1)40,44. In contrast, the pure TiO2 exhibits simultaneous adsorption of C=O group and furan ring of FAL, which results in its poor FOL selectivity (Supplementary Fig. 32). Furthermore, we also conducted FAL-TPD experiments on the pure TiO2 and CuSAs-TiO2, and the result shows that the pure TiO2 exhibits the multiple adsorption modes (Supplementary Fig. 33), resulting in poor FOL selectivity. In comparison, the CuSAs-TiO2 exhibits a single adsorption mode for FAL, which is well consistent with in situ DRIFTS results.

The highly selective production of FOL was further confirmed by mass spectrometry using a carbon radical trapping agent (1,1-diphenylethylene) (Supplementary Fig. 34)15, demonstrating the great advantages of solar-driven organic synthesis. To identify reaction intermediates, in situ EPR spectroscopic studies were performed using a radical trapping agent (5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO)). While the studies show no significant signals for TiO2 under light irradiation, the CuSAs-TiO2 displays a sextet spectrum possibly attributed to the DMPO-CH2OH spin adduct (Fig. 4h), indicating the formation of hydroxymethyl radicals (·CH2OH) during the transformation process from methanol dehydrogenation to formaldehyde (AH = 21.5 G and AN = 15.0 G)45. Moreover, Supplementary Fig. 35 reveals that by keeping the same experimental conditions, it takes longer time for the DMPO-CH2OH spin adduct signal to appear at the same intensity without the addition of water, proving that the addition of water effectively promotes the methanol dehydrogenation process. These results depict the hydrogenation process of the FAL to FOL along with the oxidation of methanol to formaldehyde, driven by the photogenerated charge carriers.

Mechanism of dynamic evolution

To confirm the mechanism, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed focusing on the dynamic evolution of Cu sites on CuSAs-TiO2. The CuSAs-TiO2 sample was simulated with Cu replacing Ti in TiO2 to form a Cu1–O4 structure (Fig. 5). Bader charge analysis suggests that 1.10 e- is directly transferred to neighboring O atoms from the Cu SA in CuSAs-TiO2. This asymmetric electron distribution is consistent with the feature observed in XANES (Fig. 2d, h), suggesting a strong interaction between Cu SA and TiO2 support. Meanwhile, the charge density difference indicates that the electron-rich Cu SAs are formed in Model III due to the transfer of photogenerated electrons compared to Model I. At this point, Cu2+ is converted to Cu+, requiring additional *H to be adsorbed on the surface to balance the surface charge and stretching the Cu–O bond (Supplementary Table 5), which is consistent with the literature33,46. According to the simulations, the VBM of the three models is mainly contributed by O atoms, while the CBM mainly originates from Ti atoms (Fig. 5b). However, the Cu1–O4 unit of Model I demonstrates the contribution to the conduction band of TiO2 surface at ~3.50 eV, which favors the accumulation of photogenerated electrons on Cu site and in turn completes the pre-activation from Cu2+ to Cu+ (Fig. 5b). We then simulated the oxidative dehydrogenation process of methanol by placing a *H in the lattice oxygen near the Cu site, and found that the Cu site contributes to the VBM as well as some occupied impurity states in the band gap of TiO2 so as to accumulate photogenerated holes for further dissociation of methanol over the as-formed Cu2+ site to remove the second hydrogen atom (Model II). In parallel, the FAL reduction process was simulated by placing two *H in the lattice oxygen. It turns out that Cu site induces unoccupied impurity states near the CBM of TiO2 at ~2.80 eV so as to accumulate photogenerated electrons for FAL hydrogenation (Model III). We also performed a comparative analysis of the adsorption energies of FAL on the three models, which shows that the FAL has a stronger affinity for adsorption on Model III (Fig. 5c), indicating that the FAL hydrogenation occurs on Cu+ site.

a The dynamic evolution models of CuSAs-TiO2, Bader charges of Cu SAs and charge density difference of the coordination atoms (I−III). The yellow and cyan indicate an accumulation and depletion in the electron density, respectively. b Total density of states (DOS) and partial density of states (PDOS) and c FAL adsorption energies (Eads) of CuSAs-TiO2 at different stages. The cobalt blue, sky blue and red spheres represent Cu, Ti and O atoms, respectively.

In summary, we have designed a Cu SAs photocatalyst with a four-coordinated Cu1−O4 structure supported by ultrathin TiO2 nanosheets, which enables the solar-driven hydrogenation of biomass-derived FAL using methanol as a hydrogen donor. The catalyst exhibits satisfactory activity and selectivity, and the yield rate of FOL is up to 34 mol h−1 molCu−1 in a photochemical flow reactor. Impressively, the gram-scale hydrogenation reaction with high yield, driven by natural sunlight, further demonstrates the practical potential of this synthetic approach. The sustainable system can easily be used to synthesize various high-value renewable chemicals from biomass-derived platform molecules. As evidenced by in situ sXAS characterizations and theoretical calculations, such a synthetic approach is enabled by the dynamic evolution of the valence state of Cu SAs. We anticipate that this work may provide a novel avenue for the development of highly efficient catalysts and systems for important biomass upgrading reactions to produce renewable chemicals.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

Copper chloride (CuCl2, 98%), titanium butoxide (TNBT, 99%), furfural (FAL, 99.5%), 5-methylfurfural (98%), 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (95%), benzaldehyde (98%), acetophenone (98%), cyclohexanone (99.5%), cinnamaldehyde (95%) and vanillin (99%) were purchased from Aladdin. Sodium sulfate (Na2SO4, 99%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 96%), hydrofluoric acid (HF, 40%), methanol (MeOH, 99.5%) and absolute ethanol (EtOH, 99.7%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. The deionized water used in all experiments was ~18.0 MΩ cm. All of chemical reagents were used as received without further purification.

Synthesis of Cu-TiO2 catalysts

The Cu-doped anatase TiO2 nanosheets dominated by (001) facet were simply synthesized by a one-pot hydrothermal method. Typically, 186.4 mg CuCl2 was first mixed with 25 mL of titanium butoxide (TNBT) and 3 mL of hydrofluoric acid (HF) solution. Subsequently, the mixed solution was transferred to a 100 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave and heated to 180 °C for 24 h. After cooling to room temperature, the precipitate was separated by centrifugation, washed with 1.0 M NaOH, deionized water and ethanol, and dried at 60 °C overnight to obtain 1.5 wt.% CuSAs-TiO2 catalyst. Other Cu-TiO2 samples with different Cu contents were prepared by varying the ratio of CuCl2 and TNBT. The catalyst of bare TiO2 nanosheets was synthesized without CuCl2.

Synthesis of CuSAs-P25

The CuSAs-P25 was synthesized through a traditional impregnation method. In a typical synthesis, 4.0 g of commercial P25 support and 0.1269 g of CuCl2 were dispersed in 20 mL of H2O under continuously stirring. Then the mixture was heated on a hotplate at 120 °C to remove water. After the evaporation of water, the mixture was calcinated at 300 °C for 2 h under a 10 vol% H2/Ar atmosphere. The commercial P25 was purchased from Aladdin.

Catalysts characterization

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were taken on a Hitachi Model H7700 microscope at 100.0 kV. High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images, scanning TEM (STEM) image and energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy mapping profiles were recorded on a JEOL JEM2100 field-emission higher-resolution transmission electron microscope at 200.0 kV. Aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC HAADF-STEM), elemental mappings and aberration-corrected AC HAADF-STEM images were recorded by a JEOL JEM-ARM 200F field-emission transmission electron microscope with a spherical aberration corrector. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded by using a Philips X’Pert Pro Super X-ray diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.54178 Å). The concentrations of various elements in the prepared samples were measured with the inductively coupled plasma−mass spectrometry (ICP−MS, Thermo Fisher Scientific iCAP RQ) after dissolving them with a mixture of HCl and HNO3 (3:1, volume ratio). Nitrogen adsorption−desorption isotherms were measured with a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 adsorption apparatus at 77 K to 1 bar using a surface area and porosity analyzer (Micromeritics ASAP 2460). UV–vis–NIR diffuse reflectance spectra were recorded in the spectral region of 200−2500 nm with a Shimadzu SolidSpec-3700 spectrophotometer. Steady-state photoluminescence spectra were recorded on a JY Fluorolog-3-Tou Spectrometer and a FluoroMax-4 spectrofluorometer (Horiba Scientific). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted on Thermo Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi using a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source under the ultrahigh vacuum (up to 10−10 mbar). Temperature-programmed desorption/mass spectrometry (TPD/MS) experiments were conducted using an AMI-300 catalyst characterization system. The signals were monitored using a Master 320 mass spectrometer. H2-temperature programmed desorption (H2-TPD) was carried out on a Micromeritics AutoChem II 2920 apparatus. The 70 mg of sample was first pretreated at 200 °C in helium with a heating ramp of 10 °C min−1 for 45 min to remove impurities. After cooling to 50 °C, the catalyst was exposed to 10 vol% H2/Ar for 60 min. Subsequently, the sample was heated from 50 to 600 °C under He flow with a heating ramp of 10 °C min−1. H2-temperature programmed reduction (H2-TPR) was carried out on a Micromeritics AutoChem II 2920 apparatus. 70 mg of the sample was first pretreated at 200 °C in helium with a heating ramp of 10 °C min−1 for 30 min and then cooled to 50 °C. Subsequently, the sample was heated from 50 to 700 °C in the flow of 10 vol% H2/He with a heating ramp of 5 °C min−1. Photoelectrochemical measurements were carried out using a three-electrode CHI 660E electrochemical workstation. The working electrode was prepared by dropping the catalyst suspension containing 5.0 mg of catalyst and 1 mL of distilled water onto the F-doped tin oxide glass (1 cm × 3 cm). The Pt foil and saturated Ag/ AgCl electrode were used as counter electrode and reference electrode, respectively. 0.5 M Na2SO4 aqueous solution was chosen as the electrolyte. The photocurrent responses of the prepared photoelectrodes (i.e., I–t) were operated by measuring the photocurrent densities under chopped light irradiation (light on/off cycles: 40 s).

SRPES characterization

Synchrotron radiation photoemission spectroscopy (SRPES) experiments were performed at the Photoemission Endstation (BL10B) in the NSRL. Valence-band spectra were measured using synchrotron-radiation light as the excitation source with a photon energy of 169.50 eV and referenced to the Fermi level (EF = 0) determined from Au. A sample bias of −10 V was applied in order to observe the secondary electron cutoff. The work function (Φ) was determined by the difference between the photon energy and the width of whole valence-band spectra.

XAS characterization

The X-ray absorption spectra (XAS) of standard anatase Cu foil, Cu2O and CuO powders were collected for comparisons. Cu K-edge XAS measurements were performed at the beamline 4B9A of Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF) in Beijing, China. The storage ring of BSRF was operated at 2.5 GeV with the maximum stored current of 250 mA.

In situ sXAS measurements

Synchrotron-radiation-based O K-edge, Ti L-edge and Cu L-edge XAS measurements were carried out at the MCD-A and MCD-B beamlines (Soochow Beamline for Energy Materials) (BL12B) of National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) in Hefei, China. The electron beam energy of the storage ring was 800 MeV with an average stored current of 300 mA. The photo energy ranged from 100 to 1000 eV with an energy resolution of 0.2 eV. All the data were recorded in the total electron yield (TEY) mode by collecting the sample drain current under a vacuum greater than 5 × 10−8 Pa. The resolving power of the grating was typically E/ΔE = 1000, and the photon flux was 5 × 108 photons per second. The specimen was situated within a reaction chamber, hermetically sealed by a Si3N4 window, meticulously tailored for real-time monitoring of state transitions in powder samples during soft X-ray spectroscopy investigations. Following placement, the specimen underwent a 5 min helium (99.999%) purge to capture its initial spectral signature. First, only light irradiation was applied in the He atmosphere, with spectral data acquisition transpiring at 5 min intervals. Upon achieving material stability, the solvent and FAL were systematically introduced into the sample chamber for 5 min, followed by another round of continuous illumination and spectral data acquisition at 10 min intervals. Upon confirming material stability, the light source was deactivated, oxygen (99.999%) was introduced, and the final spectrum was collected. The obtained spectra’s edge-jump was normalized to a value of 1.

In situ NAP-XPS measurements

In situ near ambient pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (NAP-XPS) measurements were performed at Chemistry Experiment Teaching Center at the University of Science and Technology of China in Hefei. The fresh catalyst was first treated at ultrahigh vacuum (up to 10−8 mbar). The elemental information of the sample was collected under dark conditions, and then the data was recorded again under 1.0 W cm−2 of light irradiation.

In situ EPR measurements

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra were obtained on the JEOL JES-FA200 spectrometer equipped with a 500 W xenon lamp (USHIO Optical Modulex SXS5 U1501XQ) as the illumination source. Before in situ characterization, 99.999% Ar gas was used to carry the solvent and FAL into the sample test tube continuously for 30 min. The EPR spectra were recorded under light irradiation conditions.

In situ DRIFTS measurements

In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier-transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) measurements were performed using a Bruker IFS 66 v Fourier-transform spectrometer equipped with a Harrick diffuse reflectance accessory at the Infrared Spectroscopy and Microspectroscopy Endstation (BL01B) of NSRL. Each spectrum was recorded by averaging 256 scans at a resolution of 4 cm−1.The samples were placed in an infrared (IR) reaction chamber sealed with ZnSe windows, which was specifically designed to examine highly scattered powder samples in diffuse reflection mode. After sample loading, the chamber was purged with argon gas (99.999%) for 30 min. Then the spectrum was collected as background spectrum. Before the in situ characterization, Ar gas (99.999%) was used to carry the solvent and FAL through the sample chamber continuously for 30 min. After that, the system was exposed to light irradiation and the spectra were collected when the irradiation times are 0, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 30 min, respectively. The sample chamber was kept closed during the in situ characterization.

Performance evaluation

For a typical solar-driven synthesis, the FAL hydrogenation was conducted in a batch reactor using green MeOH as a hydrogen donor. Firstly, the 10 mg of catalyst, 0.25 mmol of substrate and 6 mL of methanol−water solution (76 wt.% MeOH) were added into a pressure-resistant thick-wall reaction tube (35 mL), and the tube was filled with 1 atm high-purity Ar (99.9999%) and sealed by Teflon threaded cap. The mixture was sonicated for 5 min to form a uniform suspension. Then the reaction was performed under a full-spectrum xenon lamp illumination with a light intensity of 500 mW cm−2. After 4 h of reaction, the reaction mixture was dehydrated by anhydrous sodium sulfate. The organic phase was analyzed by gas chromatography−mass spectroscopy (GC−MS, Agilent 5795). The reaction gas was analyzed by gas chromatography (GC, Agilent 7890 A) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). In addition to H2, no carbon-containing gases such as CO, CO2 and CH4 were detected. All measurements were run independently three times, and the test results were averaged.

For better recycling of CuSAs-TiO2 catalyst in the cyclic test, a larger scale of reaction was performed. Reaction conditions: CuSAs-TiO2, 20 mg; FAL, 0.5 mmol; Methanol−water solution, 12 mL; Atmosphere, Ar; Time, 4 h; Light intensity, 100 mW cm−2. The CuSAs-TiO2 catalyst was washed using water several times after photocatalytic reaction, and dried at 70 °C overnight before the next use. To better convert various biomass-derived platform molecules, we used a LED light source with a wavelength of 365 nm for irradiation, and adjusted the reaction time to ensure the complete conversion of the substrates. Reaction conditions: CuSAs-TiO2, 10 mg; Substrates, 0.1 mmol; Methanol−water solution, 3 mL; Atmosphere, Ar; Light intensity, 100 mW cm−2. For using the designed photochemical flow device, 20 mg of sample was loaded on the channel of the homemade flow reactor. The reactor was clamped with mould and quartz plate. The reactants of FAL and MeOH were premixed, which were then pumped into the reactor for photochemical reaction under 500 mW cm−2 of light irradiation. The liquid products were received in bottle.

The conversion, selectivity and yield were estimated using the following formula:

DFT calculations

The spin-polarized density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed by using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)47,48. The interaction between the core and valence electrons was described using the frozen-core projector augmented wave (PAW) approach49,50. The generalized gradient approximation of Perdew−Burke−Ernzerhof (PBE) functional51 was used. The energy cutoff was set to be 500 eV. The DFT-D3 vdW correction proposed by Grimme with zero-damping function was adopted to describe long-range vdW interactions52. The convergence criteria of energy and force were set to be 10−5 eV and 0.02 eV Å−1, respectively. A Monkhorst−Pack grid of 11 × 11 × 5 k-points was used to sample the Brillouin zone of the unit cell for the anatase TiO2. The optimized lattice parameters were a = b = 3.821 Å and c = 9.546 Å. A 3 × 3 supercell with five layers of TiO2 was used to describe the (001) surface with the last two layers fixed in the calculation. The bottom layer Ti and O dangling bonds were saturated with pseudo-hydrogens with nuclear charges of +1.25 and +0.75, which has been reported in previous studies53,54. A vacuum space greater than 15 Å perpendicular to the surface was applied to separate the interactions between neighboring slabs. To obtain accurate electronic structures, the Heyd−Scuseria−Ernzerhof (HSE06) hybrid functional was used55. The Brillouin zone was sampled by Monkhorst−Pack mesh of 3 × 3 × 1 and Γ-centered mesh of 2 × 2 × 1 k-point for PBE and HSE06 calculations, respectively, for the slab system. Atomic coordinate information is available in Supplementary Data 1.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Li, N. et al. Selective lignin arylation for biomass fractionation and benign bisphenols. Nature 630, 381–386 (2024).

Mika, L. T., Cséfalvay, E. & Németh, Á. Catalytic Conversion of Carbohydrates to Initial Platform Chemicals: Chemistry and Sustainability. Chem. Rev. 118, 505–613 (2018).

Zheng, S. et al. Synthesis of valuable benzenoid aromatics from bioderived feedstock. Nat. Sustain. 6, 1436–1445 (2023).

Yuan, X., Lee, K., Eisenberg, J. B., Schmidt, J. R. & Choi, K.-S. Selective deoxygenation of biomass-derived carbonyl compounds on Zn via electrochemical Clemmensen reduction. Nat. Catal. 7, 43–54 (2024).

Sendeku, M. G. et al. Deciphering in-situ surface reconstruction in two-dimensional CdPS3 nanosheets for efficient biomass hydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 15, 5174 (2024).

Tian, C. et al. Progress and roadmap for electro-privileged transformations of bio-derived molecules. Nat. Catal. 7, 350–360 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. High quantum efficiency of hydrogen production from methanol aqueous solution with PtCu-TiO2 photocatalysts. Nat. Mater. 22, 619–626 (2023).

Xu, Y. et al. Efficient methane oxidation to formaldehyde via photon–phonon cascade catalysis. Nat. Sustain. 7, 1171–1181 (2024).

Chen, G. et al. Recent progress of heterogeneous catalysts for transfer hydrogenation under the background of carbon neutrality. Nanoscale 16, 1038–1057 (2024).

Shih, C. F., Zhang, T., Li, J. & Bai, C. Powering the Future with Liquid Sunshine. Joule 2, 1925–1949 (2018).

Olah, G. A. Beyond Oil and Gas: The Methanol Economy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 2636–2639 (2005).

Garg, N., Sarkar, A. & Sundararaju, B. Recent developments on methanol as liquid organic hydrogen carrier in transfer hydrogenation reactions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 433, 213728 (2021).

Bhattacharjee, S., Linley, S. & Reisner, E. Solar reforming as an emerging technology for circular chemical industries. Nat. Rev. Chem. 8, 87–105 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Hierarchical assembly of donor–acceptor covalent organic frameworks for photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide from water and air. Nat. Synth. 3, 998–1010 (2024).

Wu, X. et al. Selectivity Control in Photocatalytic Valorization of Biomass-Derived Platform Compounds by Surface Engineering of Titanium Oxide. Chem 6, 3038–3053 (2020).

Lv, S., Liu, H., Zhang, J., Wu, Q. & Wang, F. Water promoted photocatalytic transfer hydrogenation of furfural to furfural alcohol over ultralow loading metal supported on TiO2. J. Energy Chem. 73, 259–267 (2022).

Wu, Z.-Y. et al. A general synthesis of single atom catalysts with controllable atomic and mesoporous structures. Nat. Synth. 1, 658–667 (2022).

DeRita, L. et al. Structural evolution of atomically dispersed Pt catalysts dictates reactivity. Nat. Mater. 18, 746–751 (2019).

Li, Q. et al. Shear Stress Triggers Ultrathin-Nanosheet Carbon Nitride Assembly for Photocatalytic H2O2 Production Coupled with Selective Alcohol Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 20837–20848 (2023).

Luo, S. et al. Light-Induced Dynamic Restructuring of Cu Active Sites on TiO2 for Low-Temperature H2 Production from Methanol and Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 20530–20538 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Single-atom Cu anchored catalysts for photocatalytic renewable H2 production with a quantum efficiency of 56. Nat. Commun. 13, 58 (2022).

Sarma, B. B., Maurer, F., Doronkin, D. E. & Grunwaldt, J. D. Design of Single-Atom Catalysts and Tracking Their Fate Using Operando and Advanced X-ray Spectroscopic Tools. Chem. Rev. 123, 379–444 (2023).

Boyes, E. D., LaGrow, A. P., Ward, M. R., Mitchell, R. W. & Gai, P. L. Single Atom Dynamics in Chemical Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 390–399 (2020).

Liu, Y.-S. et al. In-Situ/Operando X-ray Characterization of Metal Hydrides. ChemPhysChem 20, 1261–1271 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. Titania-Supported Cu-Single-Atom Catalyst for Electrochemical Reduction of Acetylene to Ethylene at Low-Concentrations with Suppressed Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Mater. 35, e2303818 (2023).

Zhu, J. et al. Superexchange-stabilized long-distance Cu sites in rock-salt-ordered double perovskite oxides for CO2 electromethanation. Nat. Commun. 15, 1565 (2024).

Yuan, L. et al. Dynamic Evolution of Atomically Dispersed Cu Species for CO2 Photoreduction to Solar Fuels. ACS Catal. 9, 4824–4833 (2019).

Irie, H. et al. Visible Light-Sensitive Cu(II)-Grafted TiO2 Photocatalysts: Activities and X-ray Absorption Fine Structure Analyses. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 10761–10766 (2009).

Xiao, M. et al. Molten-Salt-Mediated Synthesis of an Atomic Nickel Co-catalyst on TiO2 for Improved Photocatalytic H2 Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 7230–7234 (2020).

Kang, J. et al. Valence oscillation and dynamic active sites in monolayer NiCo hydroxides for water oxidation. Nat. Catal. 4, 1050–1058 (2021).

Liu, Y., Sheng, W. & Wu, Z. Synchrotron radiation and its applications in inorganic materials. J. Inorg. Mater. 36, 901 (2021).

Shen, Y. et al. Room-temperature photosynthesis of propane from CO2 with Cu single atoms on vacancy-rich TiO2. Nat. Commun. 14, 1117 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. Photoinduced Metastable Asymmetric Cu Single Atoms for Photoreduction of CO2 to Ethylene. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2302692 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. Oxygen evolution reaction over catalytic single-site Co in a well-defined brookite TiO2 nanorod surface. Nat. Catal. 4, 36–45 (2020).

Xie, S. et al. Role of the Metal Atom in a Carbon-Based Single-Atom Electrocatalyst for Li-S Redox Reactions. Small 18, e2200395 (2022).

Davó-Quiñonero, A. et al. Insights into the Oxygen Vacancy Filling Mechanism in CuO/CeO2 Catalysts: A Key Step Toward High Selectivity in Preferential CO Oxidation. ACS Catal. 10, 6532–6545 (2020).

Jiang, P. et al. Experimental and theoretical investigation of the electronic structure of Cu2O and CuO thin films on Cu(110) using x-ray photoelectron and absorption spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 138, 024704 (2013).

Kuterasinski, L. et al. Reduction and Oxidation of Cu Species in Cu-Faujasites Studied by IR Spectroscopy. Molecules 25, 4765 (2020).

Fu, Y. et al. dz2 Band Links Frontier Orbitals and Charge Carrier Dynamics of Single-Atom Cocatalyst-Aided Photocatalytic H2 Production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 28166–28175 (2023).

Fu, Q. et al. Highly-dispersed surface NiO species and exposed Ni (200) facets facilitating activation of furan ring for high-efficiency total hydrogenation of furfural. Appl. Catal. B 343, 123501 (2024).

Xu, X. et al. Quenching method to prepare ultra-low loading high-entropy catalyst for furfural selectively hydrogenation at ambient temperature. Appl. Catal. B. 342, 123358 (2024).

Yu, J. et al. NiBi intermetallic compounds catalyst toward selective hydrogenation of unsaturated aldehydes. Appl. Catal. B. 277, 119273 (2020).

Wang, Q. et al. Interfacial Structure-Determined Reaction Pathway and Selectivity for 5-(Hydroxymethyl)furfural Hydrogenation over Cu-Based Catalysts. ACS Catal. 10, 1353–1365 (2019).

Meng, H. et al. Designing Cu0-Cu+ dual sites for improved C-H bond fracture towards methanol steam reforming. Nat. Commun. 14, 7980 (2023).

Jiang, Y. et al. Elevating Photooxidation of Methane to Formaldehyde via TiO2 Crystal Phase Engineering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 15977–15987 (2022).

Lee, B. H. et al. Reversible and cooperative photoactivation of single-atom Cu/TiO2 photocatalysts. Nat. Mater. 18, 620–626 (2019).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. Condens. Matter. 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci 6, 15–50 (1996).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. Condens. Matter. 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Chu, W. et al. Ultrafast Dynamics of Photongenerated Holes at a CH3OH/TiO2 Rutile Interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 13740–13749 (2016).

Chu, W., Zheng, Q., Prezhdo, O. V. & Zhao, J. CO2 Photoreduction on Metal Oxide Surface Is Driven by Transient Capture of Hot Electrons: Ab Initio Quantum Dynamics Simulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 3214–3221 (2020).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the NSFC (22122506, 22479139, 51472111, 22073085, 22232003, 22075267), the Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2408085JX001), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of CAS (Y2023129), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (20720220007, WK2060000039, KY2140000031) and the West Light Foundation of Chinese Academy of Sciences (xbzg-zdsys−202209). The authors thank the support from USTC Center for Micro- and Nanoscale Research and Fabrication. We thank the beamlines BL12B, BL01B and BL10B at the National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) in Hefei and 4B9A beamline of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF) for providing sufficient beamtime. The numerical calculations in this work were performed on the supercomputing system in the Supercomputing Center of the University of Science and Technology of China. This work was partially carried out at the Instruments Center for Physical Science, University of Science and Technology of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X., R.L. and W.G. conceived and designed the project. G.C. synthesised the catalysts and evaluated the synthesis performances. C.F. contributed to the DFT calculations and discussion. W.Z., L.Q. and X.F. performed in situ sXAS measurements. X.J. and J.M. performed the XPS measurements and discussion. C.H. contributed to in situ DRIFTS characterization. G.C., W.G. and Y.X. co-wrote the manuscript. G.C., C.F., and W.Z. contributed equally to this work. All the authors contributed to the discussion and paper revision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Haohong Duan, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, G., Fu, C., Zhang, W. et al. Solar-driven production of renewable chemicals via biomass hydrogenation with green methanol. Nat Commun 16, 665 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56094-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56094-4

This article is cited by

-

Adsorptive Removal of Ibuprofen from Aqueous Solution by UiO-66: Performance Evaluation and Mechanistic Insights

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2026)

-

H2-free hydrodeoxygenation of microalgae biomass using Pd-Ni/γ-Al2O3 bimetallic nanocatalyst in the supercritical environment

Scientific Reports (2025)