Abstract

Challenges in CO2 capture, CO2 crossover, product separation, and electrolyte recovery hinder electrocatalytic CO2 reduction (CO2R). Here, we present an integrated electrochemical recovery and separation system (ERSS) with an ion separation module (ISM) between the anode and cathode of a water electrolysis system. During ERSS operation, protons from the anolyte flow through the anodic cation exchange membrane (CEM) into the ISM, acidifying the CO2R effluent electrolyte. Cations like K+ in the ISM flow through the cathodic CEM into the catholyte to balance the OH− ions from hydrogen evolution. ERSS recycles electrolyte-adsorbed CO2, recovers KOH with a 94.0% K+ yield, and achieves an 86.2% separation efficiency for CO2R products. The recovered KOH can capture CO2 from air or flue gas or be utilized as a CO2R electrolyte, closing the CO2 capture, conversion, and utilization loop. Compared to the conventional acid-base neutralization process, ERSS saves $119.76 per ton of KOH recovered and is applicable to other aqueous alkaline electrosynthesis reactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Renewable electricity-driven electrosynthesis, such as the electrolysis of CO2, N2, H2O, hydrocarbons, and biomass, offers promising alternatives for conventional industrial reactions and supports carbon management and net-zero emissions goals. CO2 reduction (CO2R), a key electrosynthesis reaction, can produce high-value fuels and chemicals, facilitate renewable energy storage, and significantly reduce CO2 emissions. Significant efforts have focused on developing CO2R catalysts with high product selectivity (Faradaic efficiency, FE) for C1 (CO, formate, methanol) or C2+ (ethylene, ethanol, n-propanol) products, high current density, high energy efficiency (EE), and long-term stability at low overpotentials. Despite recent advances, CO2R is not yet industrially viable due to several challenges:

First, CO2 capture remains a significant challenge. Conventional wet chemical scrubbing using sp3 amines faces technical and economic issues, including high energy consumption, corrosion, and sorbent degradation1,2. The Ca(OH)2/CaCO3/CaO + CO2 cycling process is energy-intensive, requiring temperatures up to 900 °C to release CO23. Electrochemically mediated carbon capture with redox-active organic compounds, such as quinones, shows promise but lacks reliable sorbents with excellent solubility, processibility, and stability against impurities4. The electrochemical solid-electrolyte reactor using oxygen/water (O2/H2O) redox couple also shows potential5 but is limited by high operational energy consumption.

Second, CO2 utilization efficiency in CO2R remains very low. Continuous-flow electrolyzers, such as zero-gap membrane electrode assemblies (MEA) and flow cells with highly alkaline electrolytes, achieve high current density for producing CO, ethylene, ethanol, and multi-carbon products6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. However, a high concentration of OH− ions leads to significant CO2 loss through the reaction of 2OH− (aq) + CO2 (g) → CO32− (aq) + H2O, and CO2 crossover where CO3²⁻ migrates to the anolyte, reducing CO2R efficiency. For instance, in two-electron processes like CO2 to CO, CO2 utilization efficiency is often below 50%, and for ethylene and ethanol production, it typically does not exceed 25%14. Electrocatalytic CO2R in acidic media can avoid CO3²⁻ formation but faces challenges such as the need for substantial cations (like K+) to suppress HER, anode catalyst instability in acidic conditions, and severe corrosion of reactor materials15.

Finally, high costs are associated with electrolyte recovery and product separation. Techno-economic analysis (TEA) of alkaline CO2 electrolyzers indicates that over 50% of the input energy is used for regenerating alkaline solution and CO2 from CO32− ions14. Additionally, recovering the alkaline electrolyte and separating products from the CO2R effluent further increases costs. For instance, chemical neutralization and distillation for downstream liquid product separation from an alkaline electrolyte account for over 60% of capital costs and 64% of total energy costs16. However, most CO2R research tends to focus on catalyst development, electrolyzer design, and mechanism verification, often overlooking product separation and application, which delays the industrialization of CO2R.

Industrializing CO2R requires a systematic engineering approach to optimize costs for catalyst production, electrolyzer manufacture, CO2 capture, CO2 utilization efficiency, electrolyte recovery, and product separation. Such a comprehensive approach has not yet been reported. We present an integrated electrochemical recovery and separation system (ERSS) based on the electrodialysis principle17,18,19,20,21, featuring an ion separation (ISM) module between the anode and cathode of a water electrolysis cell. The ERSS facilitates the recycling of the electrolyte-adsorbed CO2 from the acidified ISM (CO32−(aq)/HCO3− (aq) → CO2 (g)) and achieves 94% KOH recovery and 86.2% separation efficiency for CO2R products. Recovered KOH can capture CO2 from air or flue gas or be used directly for CO2R, supporting continuous CO2 capture, conversion, and utilization. The ERSS paves the way for CO2R industrialization with renewable energy.

Results and discussion

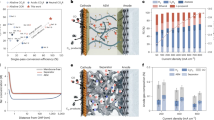

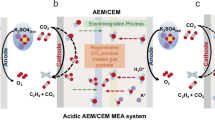

Configuration of the ERSS. Figure 1 shows the integration of an alkaline CO2R electrolyzer (Fig. 1a) with the ERSS system (Fig. 1b). The ERSS includes an oxygen evolution reaction (OER) anode (2H2O → O2 + 4H+ + 4e−) with an iridium oxide catalyst on titanium mesh and a hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) cathode (2H2O + 2e− → H2 + 2OH−) with a commercial Pt/C catalyst. Both electrodes used pure water as the electrolyte. The anode and cathode were separated by an ISM consisting of CEMs with a porous carbon felt or polyethylene mesh as a support layer. This support layer was in close contact with the CEMs to minimize ohmic losses. The effluent electrolyte, containing CO2R products, alkali, and carbonate/bicarbonate from the alkaline CO2R electrolyzer, flowed directly into the ISM chamber for CO2 capture, alkali recovery, and product separation.

a A conventional continuous-flow alkaline CO2R electrolyzer. b The configuration and working mechanism of the ERSS system. The ERSS consisted of an HER cathode, an OER anode, and an ISM. The anode and cathode were separated by the ISM. The ISM comprised two CEMs separated by a porous carbon felt or polyethylene network. The porous carbon felt or polyethylene network was placed as a support layer in the ISM chamber, in close contact with CEMs on both sides, to minimize the overall ohmic losses of the ERSS. Through water electrolysis in the ERSS, the protons generated in the anolyte flowed through the CEM into the ISM, gradually acidifying the effluent electrolyte from the CO2R electrolyzer and producing water (H+ + OH− = H2O) and high-purity CO2 (CO32−(aq)/HCO3− (aq) → CO2 (g)). Meanwhile, cations such as K+ in the ISM chamber flowed through another CEM into the catholyte to balance the OH− ions generated HER, recovering a high-purity KOH solution. The liquid products from the alkaline CO2R electrolyzer can collected as an aqueous solution from the ISM chamber.

In the ERSS, water electrolysis generated protons in the anolyte, which flowed through the anodic CEM into the ISM, acidifying the effluent electrolyte from the CO2R electrolyzer and producing water (H+ + OH− = H2O) and high-purity CO2 (CO32−/HCO3− → CO2). Concurrently, cations like K+ in the ISM flowed through the cathodic CEM into the catholyte to balance OH− ions from the HER, recovering high-purity KOH. During ERSS operation, the KOH electrolyte, liquid products, and carbonate/bicarbonate from the CO2R electrolyzer in the ISM served as ion transporters, reducing the overall cell voltage. The CEM in the ISM chamber effectively separated some alcohol and carboxylic acid products from the effluent electrolyte. The high-purity H2 at the cathode and O2 at the anode can be collected and marketed as by-products.

Our ERSS design offers several advantages. Firstly, it operates at room temperature, making it simple and efficient while producing high-purity H2 and O2 by-products. Secondly, traditional product separation from alkaline solutions involves an acid-base neutralization process (ABNP) and low-temperature crystallization, requiring excess acid and posing significant anticorrosion challenges16. In contrast, our ERSS efficiently recovers KOH electrolytes electrochemically, allowing for direct reuse without additional treatment. Thirdly, the ERSS only performs OER/HER electrolysis, consuming minimal water without needing specific chemicals or consumables. Fourthly, it recovers adsorbed CO2 from the effluent electrolyte of CO2R, addressing low CO2 utilization efficiency in alkaline CO2R electrolyzers. Fifthly, over-accumulating liquid products in alkaline electrolytes degrade CO2R operational stability. Our ERSS continuously separates products and recovers KOH, enhancing CO2R stability. The ERSS offers a systematic approach for electrolyte recovery, product separation, and CO2 capture for alkaline CO2R electrolyzers using renewable electricity.

Concept verification

To validate the ERSS, we prepared five simulated 0.1 M KOH solutions (10 mL), each containing one of the following: methanol (MeOH, 9.091 v%), ethanol (EtOH, 9.091 v%), n-propanol (PrOH, 9.091 v%), formic acid (FA, 0.023 v%), and acetic acid (HAC, 0.023 v%). These compounds are common CO2R products. As shown in Fig. 2a, linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) was performed on the ERSS with the ISM chamber filled with pure or mixed 0.1 M KOH solutions containing different alcohols. The presence of alcohols led to lower currents in the LSV curves compared to pure KOH solutions between -3 ~ -5 V, attributed to alcohols’ ability to penetrate the CEM and affect ion transfer efficiency, with smaller molecules permeating more easily (Fig. 2a). The initial ERSS voltage was approximately 1.81 V, including the water electrolysis thermodynamic potential (1.23 V), OER and HER overpotentials, and ohmic loss. Under a constant 3 V with 90 C passed charges (87.7 C needed to recover all K+ ions) (Fig. 2b), the yields of MeOH, EtOH, and PrOH were 84.1%, 95.6%, and 90.9% (Fig. 2c), respectively, indicating minimal alcohol loss through CEM permeation. Correspondingly, K+ recovery yields were above 95.6%, 94.3%, and 97.4% (Fig. 2c).

a The i-V curves (without iR corrections) of the ERSS operated with the 0.1 M KOH simulated electrolyte with MeOH (9.1 v%), EtOH (9.1 v%), and PrOH (9.1 v%), respectively. b The i-t (with 95% iR corrections) and Q-t curves of the ERSS operated with the 0.1 M KOH simulated electrolyte with MeOH, EtOH, and PrOH, respectively. c The KOH, MeOH, EtOH, and PrOH yields, respectively. d The i-V curves (without iR corrections) of the ERSS operated with the 0.1 M KOH simulated electrolyte with FA (0.023 v%) and HAc (0.023 v%), respectively. e The i-t (with 95% iR corrections) and Q-t curves of the ERSS operated with the 0.1 M KOH simulated electrolyte with FA and HAc, respectively. f The yields of KOH, FA, and HAc, respectively. The i-t curves were all operated at a constant voltage of 3 V and were stopped when the accumulated charge reached 90 C. The electrode utilized in the ERSS was with a surface area of 2 × 2 cm2. The ERSS was performed at room temperature and ambient pressure.

The behavior for carboxylic acids (FA and HAc) is similar. Although the LSV curves for 0.1 M KOH solutions containing low concentrations of FA (0.023 v%) and HAc (0.023 v%) were comparable to those of pure KOH solutions (Fig. 2d), increasing the concentration (Supplementary Fig. 1), for example, of FA, reduced ion transport efficiency. This was attributed to the consumption of OH⁻, which forms formate anions (HCOO⁻) that migrate more slowly than OH⁻ (the effect is less pronounced at low HCOO⁻ concentrations). After applying a constant 3 V and passing 90 C (Fig. 2e), FA and HAc yields were 96.1% and 94.9% (Fig. 2f), and K+ recovery yields were 95.2% and 94.3% (Fig. 2f), respectively. Despite dissociation constants of 1.77 × 10−4 for FA and 1.75 × 10−5 for HAc, the pH of separated solutions was acidic (3.7 and 3.8, respectively; Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating most FA and HAc remained in their acid form. In contrast, the solutions were neutral after alcohol separation (Supplementary Fig. 3). pH measurements for pure water and solutions with FA (0.023 v%) and HAc (0.023 v%) were 6.7, 3.3, and 3.6, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4), confirming the effective removal of the majority of K⁺ from the solutions. Considering the impact of small molecules on CEM swelling and shuttle effects, we also analyzed the composition and pH of the anolyte. The pH values of the anolytes were measured to be 6.5, 6.6, and 6.7, respectively, when alcohol molecules (MeOH, EtOH, or PrOH) were present in the solution within the ISM, which is similar to the pH of deionized water (6.7), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. To investigate the presence of alcohol molecules, we employed 1H-NMR to analyze the alcohols diffusing from the ISM into the anolyte. Our results confirmed the presence of alcohol molecules in the anolytes of the ERSS. However, it is essential to note that the presence of these alcohol molecules did not alter the pH value of the anolyte, and no electro-oxidation products such as FA or HAc were detected. When FA or HAc were present in the ISM solution, no specific acid species in the anolyte was detected. Nevertheless, the pH measurements of the anolytes were approximately 5.5 and 5.6, respectively, suggesting that a small number of acidic molecules may have permeated into the anolyte. However, their concentrations were too low for direct detection by 1H-NMR (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Considering the charge balance within the ERSS, the cathode chamber generated one OH− for each electron transferred, while one K+ migrated from the ISM chamber to the catholyte, forming KOH. Thus, we define KOH recovery’s Faradaic efficiency (FE) to assess economic benefits. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 7, FEs of KOH recovery exceeded 90% for all simulated alcohol and carboxylic acid solutions. We varied KOH concentrations in the ISM chamber from 0.1 M to 1.0 M, observing that LSV curve currents increased with higher concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 8). This is because the KOH solution in the ISM chamber acted as an ion transporter; higher ion concentrations facilitated faster ion transport, leading to higher currents.

Electrochemical CO2 capture typically involves absorbing and releasing CO2 through pH swings22,23,24. Based on the ERSS mechanism, we assessed capturing CO2 from the atmosphere or flue gas using KOH solution and recycling high-purity CO2 from the resulting K2CO3 or KHCO3. The specific reactions for CO2 capture with KOH are:

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 9, as the ISM chamber processes either K2CO3 or KHCO3 solution, protons from OER migrate through the anodic CEM towards the ISM chamber, driven by the electric field. Within the ISM chamber, the following reactions occur:

Under the electric field, K+ migrates through the cathodic CEM towards the cathode, combining with OH− from the HER to form KOH and maintain charge balance. Despite the lower migration rates of CO32− and HCO3− compared to OH−, their effect on ERSS operation remains acceptable (Supplementary Fig. 10). To validate the ERSS’s capability for simultaneous CO2 capture and CO2R product separation, an operational process was devised (Fig. 3a). High-purity CO2 was collected at the ISM outlet, with H2 and O2 by-products from the cathode and anode, respectively, via water electrolysis (Fig. 3a). A 0.5 M K2CO3 solution containing 0.091 v% FA was used as a simulated solution, and CO2 was collected using the water displacement method. Applying a constant voltage of 5 V for ERSS electrolysis, real-time CO2 collection was monitored (Fig. 3b). 50 mL CO2 was produced in the first 16 min. The volume of CO2 gradually increased, reaching a plateau of 345 mL, with a collected yield of 77.5% (Fig. 3c). The KOH recovery yield was 90.2%, and the FA yield was 80.6% (Fig. 3c). Approximately 22.5% of the remaining CO2 dissolved in the electrolyte or trapped in ISM. Initially, protons from the anode reacted with K2CO3 to form KHCO3, delaying CO2 production. At 16 min, 2023.8 C of charge had passed, while converting K2CO3 to KHCO3 required approximately 1754.3 C. Consequently, only 50 mL of CO2 was collected over 16 min.

a Schematic diagram of the ERSS for KOH recovery, CO2 capture, and organic molecule separation from carbonate/bicarbonate electrolytes. b The CO2 production and charge consumption curves from the ERSS operated with 0.5 M K2CO3 simulated electrolyte with FA (0.091 v%). c The corresponding yields of KOH, FA, and CO2. d The CO2 production and charge consumption curves from the ERSS operated with 1.0 M KHCO3 simulated electrolyte with FA (0.091 v%). e The corresponding yields of KOH, FA, and CO2. The Q-t curves were all operated at a constant voltage of 5 V. The electrode utilized in the ERSS was with a surface area of 10 × 10 cm2. The resistance was about 0.7 Ω (KHCO3 with FA) and 0.5 Ω (K2CO3 with FA). There were no iR corrections to the voltage. The ERSS was performed at room temperature and ambient pressure.

We operated ERSS with a 1.0 M KHCO3 solution containing 0.091 v% FA to validate the phenomenon. Applying a constant voltage of 5 V, we collected 50 mL of CO2 after 2 min of electrolysis, corresponding to a charge of 235.5 C (Fig. 3d). As the reaction continued, the CO2 volume increased to 690 mL, with a CO2 capture yield of 79.6% (Fig. 3e). The KOH recovery yield was 90.1%, and the FA yield was 82.2%. FA, being more acidic than H2CO3, reacted with KHCO3 to release approximately 26 mL of CO2 during solution preparation. This leads to a CO2 yield based on reactions (3) and (4), where HCO3− reacts with one proton to form one CO2 molecule, and CO32− reacts with two protons to form one CO2 molecule. The underestimation of CO2 collection might result from the electric double layer on the electrodes, which consumed a portion of the charge. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 11, the FEs for KOH recovery in K2CO3 and KHCO3 solutions were 87.6% and 85.3%, respectively, and the CO2 capture efficiencies were 75.2% and 75.4%. These results demonstrate that the ERSS effectively integrates CO2 capture, product separation, and electrolyte recovery.

Practical integration of ERSS with alkaline CO2R. The low CO2 utilization efficiency in alkaline CO2R electrolyzers poses a significant barrier to CO2R industrialization14. Most CO2 is absorbed by the alkaline solution to form CO32− rather than participating in catalytic reactions. To make CO2R industrialization cost-effective, recovering and reusing the KOH electrolyte is crucial. We integrated our ERSS with an alkaline CO2R electrolyzer and demonstrated its effectiveness for CO2 capture and product separation. Various FA-selective electrocatalysts, including Bi, Co, Pd, In, Pb, Sn, and carbon-based materials25,26,27,28,29,30,31, can be explored for ERSS applications. Bismuth-based catalysts have achieved Faradaic efficiencies (FE) over 95% at high current densities ( > 50 mA cm−2), outperforming most non-precious metal catalysts32,33,34,35,36. As a demonstration, we synthesized a two-dimensional Bi (2D-Bi) catalyst via a hydrolysis method for alkaline CO2R to produce FA13. This catalyst, featuring abundant low-coordination active sites, showed enhanced catalytic performance13. Characterization by X-ray diffraction, SEM, TEM, and STEM-EDS revealed that the 2D-Bi catalyst had a Bi6O6(OH)3(NO3)3·1.5H2O crystal phase and a nanosheet structure consistent with previous reports13 (Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Fig. 13).

The CO2R performance of the 2D-Bi catalyst was evaluated in a two-electrode flow cell using 1.0 M KOH as the electrolyte. Gas and liquid products were analyzed via gas chromatography (GC) and 1H-NMR, respectively. As expected, the main product was FA, with minor CO and H2 by-products (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 14, and Supplementary Fig. 15). The maximum FE for FA was approximately 95.7%, with a partial current density of FA reaching 181.4 mA cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 16). A stability test showed that the catalyst maintained a current density of 50 mA cm−2 for about 200 min, with the FE for FA remaining above 85% (Fig. 4b). Post-reaction, the pH of the KOH electrolyte decreased slightly from 13.9 to 13.8 (Supplementary Fig. 17). To simulate CO2 capture from flue gas, the post-reaction electrolyte was bubbled with 10% CO2 in Ar at 100 sccm before KOH recovery on ERSS, and the pH was monitored in real-time. As shown in Fig. 4c, the pH dropped from 13.8 to 13.0 within 19 min, decreased rapidly to 10.7 between 19 and 35 min, and slowed to 8.9 by 161 min (Supplementary Fig. 18). This pH decreased because CO2 reacted with KOH and followed the reaction path of CO2 → K2CO3 → KHCO3.

a The FEs of electrocatalytic CO2R products on Bi-based catalysts at different current densities. b Long-term stability test of Bi-based catalyst at 50 mA cm−2 current density. c The pH evolution curves of the catholyte after electrocatalytic CO2R during the adsorption of simulated flue gas (10% CO2 at 100 sccm). d The CO2 production and charge consumption curves from the ERSS operated with the CO2-saturated catholyte. The Q-t curves were all operated at a constant voltage of 5 V and were stopped when the charge consumption reached 3931.3 C. e The pH value of catholyte from the ERSS before and after KOH recovery. f Long-term stability test of Bi-based catalyst with the recovered KOH electrolyte at 50 mA cm−2 current density. The electrode utilized in the ERSS was with a surface area of 10 ×10 cm2. The resistance was about 0.7 Ω. There were no iR corrections to the voltage. The ERSS was performed at room temperature and ambient pressure.

After the CO2 adsorption process was completed, the 40 mL electrolyte was subjected to our ERSS at a constant voltage of 5 V. Real-time CO2 collection was monitored (Fig. 4d). Initially, collecting 50 mL of CO2 in 3 min is slower compared to the KHCO3 simulated solution (2 min), indicating the presence of K2CO3. Once the electrolyte converted to KHCO3, CO2 production began, resulting in a total collection of 630 mL. The amount of captured CO2 depended on the later-stage electrolyte’s CO2 absorption capacity (Fig. 4c) and the FA yield from CO2R. HCOO− might influence CO2 adsorption, but neutral CO2R products like alcohols do not affect CO2 capture. The CO2 absorption rate decreased in the later stages as the system approached saturation. The final recovery yields for KOH, FA, and CO2 were 94.0%, 86.2%, and 69.1%, respectively, with Faradaic efficiencies for KOH and CO2 recovery at 92.3% and 67.7% (Supplementary Fig. 19 and Supplementary Fig. 20). The pH of the recovered KOH solution was 13.9, consistent with a 1 M KOH solution (Fig. 4e). Using this recovered KOH for CO2R, we achieved stable performance at 50 mA cm−2 for 200 min, with a FE for FA above 85%, demonstrating the ERSS’s effectiveness in practical applications (Fig. 4f).

To further investigate the feasibility of continuous separation using ERSS (Supplementary Fig. 21), we treated a simulated electrolyte containing 0.074 V% FA in 0.1 M KOH at a flow rate of 1.1 mL/min in the ISM (Supplementary Fig. 22). The yields of FA and KOH remained above 80% and 85%, respectively. The ERSS operated continuously for 100 h without degradation. To simulate practical industrial conditions, we also tested the ERSS with a higher concentration of 0.4 V% FA in 1.0 M KOH at a flow rate of 1.1 mL/min (2 A current) and 2.2 mL/min (4 A current). Under these conditions, the yields of FA and KOH stayed above 80% and 85%, demonstrating the ERSS’s effectiveness for industrial applications (Supplementary Fig. 23).

The design of the ERSS extends beyond its application in alkaline CO2R, offering the potential for various alkaline electrosynthesis reactions, such as the anodic oxidation of alcohols for alkali recovery and product separation. Replacing the energy-intensive OER with anodic oxidation of alcohols or aldehydes reduces energy consumption while generating high-value organic products at the anode. This method has garnered significant interest from the research community. For instance, biomass-derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) electrooxidation to produce furan-2,5-dicarboxylic acid (FDCA) is a promising reaction to couple with CO2R. The main operational costs for this reaction are associated with alkali recovery and product separation. We tested the ERSS using a simulated 0.1 M KOH solution containing 0.91 mM FDCA for KOH recovery and FDCA separation. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 24, the ERSS LSV curve for the KOH-FDCA solution was slightly lower than for pure KOH due to the larger FDCA anion size and slower electron transfer rate compared to OH−. After operating the ERSS at a constant voltage of 3 V with 90 C of charge passed, KOH recovery reached 95.6%, FDCA yield was 99.5%, and Faradaic efficiency for KOH recovery was 93.1% (Supplementary Fig. 24). The larger size of the FDCA molecule compared to FA and HAc results in higher separation yields due to its reduced ability to penetrate the CEM.

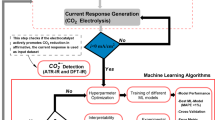

Therefore, we propose an integrated system combining electrochemical conversion systems (ECS) and ERSS, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. This system comprises three main zones: the ECS zone, the CO2 capture zone, and the ERSS zone. In the ECS zone, cathodic CO2R is coupled with anodic oxidation of organic substances in alkaline electrolytes (e.g., KOH solution). The effluent catholyte and anolyte are then collected and transferred to CO2 absorption towers in the CO2 capture zone to adsorb CO2 from flue gas or air. Once saturated with CO2, the effluent solutions are sent to separate ERSS units in the ERSS zone for CO2 release and product separation. The recovered KOH solution from the ERSS can be reused in the ECS, and the captured CO2 serves as a feedstock for the ECS (Fig. 5a, b). As demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 25 and Supplementary Fig. 26, a continuous operation involving electrocatalytic CO2 reduction coupled with CO2 capture and the ERSS system was performed. Our experimental results indicated that the CO2R system could operate stably, achieving a FE of FA greater than 80%. Additionally, the system consistently released high-purity CO2 from the ISM chamber of the ERSS at a flow rate of 3.92 mL/min, with a high purity of greater than 97%, containing less than 3% hydrogen (H2) that diffused from the cathode (Supplementary Fig. 27). This integration effectively addresses the challenge of low CO2 utilization in alkaline CO2R. The products collected from the anolyte and catholyte can either be used directly or undergo further purification. Additionally, the system produces high-purity H2 and O2 for market sale and operates continuously using only renewable electricity and pure water. Beyond CO2R, ERSS can also be applied to heterogeneous catalysis systems in alkaline environments for alkali recovery and product separation, such as thermally catalytic alcohol oxidation37. In summary, our ERSS design is versatile for alkaline reaction systems, including ECS and heterogeneous catalysis, enabling efficient product separation and alkaline solution recovery.

a Flowchart demonstration of the integration of the ECS and the ERSS, including the ECS zone, the CO2 capture zone, and the ERSS zone. After conducting cathodic CO2R coupled with anodic oxidation of an organic substance in alkaline electrolytes in the ECS zone, both the effluent catholyte and anolyte are transferred to the CO2 absorption towers in the CO2 capture zone to adsorb CO2 from flue gas or air, respectively. Once the effluent catholyte and anolyte are saturated by CO2, they will be transferred into two separate ERSS units in the ERSS zone for CO2 release collection and product separation. The recovered KOH solution from ERSS can be re-utilized as the electrolyte for ECS, and the captured CO2 can be supplied as a source for ECS. b Schematic diagram demonstrating an operation cycle, including electrocatalytic CO2R, CO2 capture, electrolyte recycling, and product separation. c Techno-economic analysis on the operation of the ERSS, assuming 1 tone of KOH is treated daily. d The energy cost of the ERSS system for 1-ton KOH recovery operated under different voltages.

Techno-economic and energy costs analysis. In this work, our primary motivation was to address practical challenges in electrolyte recovery and product separation in the ECS. Thus, a techno-economic analysis was conducted to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the ERSS. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 28a, our ERSS recovers 1 ton of KOH at a cost of only $243.26, which includes expenses for the electrolyzer, electricity, water, catalysts, CEM, factory balance, labor, and balance of plant (Bop). Electricity constitutes 21.82% of the total cost; however, with the rapid advancement of renewable energy, these costs are expected to decrease. Revenues from by-products—CO2, H2, and O2—amount to $30.50, $29.70, and $7.92, respectively, resulting in the reduction of a net cost of $68.12 per ton of KOH recovered. In contrast, traditional ABNP for KOH treatment (Supplementary Fig. 29), which relies on large amounts of H2SO4 (Supplementary Fig. 28b), incurs a net cost of $294.9 per ton of KOH due to the lack of profitable by-products and no CO2 emission reduction benefits. Furthermore, our ERSS is more energy-efficient than ABNP, saving $119.76 per ton of KOH treated (Fig. 5c) at the onset voltage. Our findings indicate that the energy consumption of the ERSS system is exclusively dependent on the applied voltage (Fig. 5d). Although the energy required to recover 1 ton of KOH in our ERSS process (9.55 GJ at 5 V) is slightly higher than the energy reported for capturing 1 ton of CO₂ (7.98 GJ)5, our energy expenditure encompasses a broader range of processes. This includes not only CO₂ capture and KOH recovery but also the utilization of alkaline ECS electrolytes, product purification, and the additional value generated from high-value O₂ and green H₂ production. Consequently, it is essential to select an appropriate applied potential tailored to specific industrial requirements (Supplementary Fig. 30b). Although the initial energy cost for CO2 capture is slightly higher (about 249 kJ/mol CO2) compared to recent advancements (Supplementary Fig. 30a and Supplementary Table S2), the ERSS’s multifunctional capabilities offer substantial advantages. Overall, the ERSS effectively addresses downstream challenges in the alkaline ECS and significantly contributes to CO2 emission reduction efforts.

In summary, we designed an ERSS to integrate electrolyte recovery, CO2 capture, and product separation, addressing key challenges in alkaline ECS. The design was motivated by the need to reduce CO2 emissions and enhance CO2 utilization efficiency in alkaline CO2R processes. The ERSS effectively recovered KOH from the CO2R effluent with a K+ yield of 94.0% and achieved up to 86.2% separation efficiency for CO2R liquid products. This recovered KOH can be reused for CO2 capture from air or flue gas and as an electrolyte for CO2R, thereby closing the CO2 capture, conversion, and utilization loop. Our techno-economic analysis indicates that electricity is one of the major cost components of the ERSS, constituting 21.82% of the total cost. Future research can focus on optimizing parameters such as operation temperature, pressure, and catalyst performance, and developing more efficient CEMs to lower energy costs and enhance practical deployment. The ERSS represents a significant advancement in alkaline ECS, offering a more effective alternative to traditional alkali recovery and product separation processes.

Methods

Materials

Proton exchange membrane (PEM) of Nafion 117 (Fuel cell store). 20% Pt/C catalysts (Johnson Matthey). Titanium mesh coated with iridium oxide (Alibaba TaoBao Store). Formic acid (FA, 98%). Acetic acid (HAc, 99.8%). Furan-2,5-dicarboxylic acid (FDCA, 99%). Methanol (MeOH, 99.5%). Ethanol (EtOH, 99.7%), Propanol (PrOH, 99.7%). Potassium bicarbonate (KHCO3, 99.7%). Potassium carbonate (K2CO3, 99.5%). Potassium hydroxide (KOH, 95%). Bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (Bi(NO3)2 ∙ 5H2O, AR). Hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB, 99%). Pure water (Milli-Q, 18.2 MΩ).

ERSS construction and operation

The ERSS was constructed as a three-compartment electrolysis cell, separated by proton exchange membranes of two Nafion 117 (used as received without any treatment), with a working window area of 2 ×2 or 10 x 10 cm² toward the ISM. Commercial 20% Pt/C catalysts were loaded on 2 × 2 or 10 x 10 cm² carbon paper as the cathode (1 mg/cm2), while a 2 ×2 or 10 x 10 cm² titanium mesh coated with iridium oxide served as the anode (1 mg/cm2). The cathode and anode were supplied with ultrapure water. The ERSS measurements were conducted on the BioLogic VMP3 workstation or DC POWER SUPPLY (DP6010). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy data were collected in the frequency range of 0.1–100,000 Hz in 0.1 M KOH solution with MeOH, EtOH, PrOH, FA, HAc, or FDCA (Supplementary Table S3). Cathode electrolyte 10 mL or 40 mL. All experiments were conducted at room temperature (25 °C) and ambient pressure.

Preparation of simulated solutions

Stock solution preparation: A FA stock solution with a concentration of 1 v% was prepared by mixing 100 μL of FA with 9.9 mL water. An HAc stock solution with a concentration of 1 v% was prepared by mixing 100 μL of HAc with 9.9 mL water. FDCA stock solution with a concentration of 10 mM was prepared by dissolving 15.77 mg FDCA in 10 mL water.

Simulated solution preparation: The FA simulated solution was prepared by thoroughly mixing 10 mL of 0.1 M KOH solution with 250 μL of FA stock solution and 750 μL of water. The preparation method for the HAc simulated solution was similar, except for substituting the FA stock solution with 250 μL of HAc stock solution. The methanol solution was prepared by thoroughly mixing 1 mL MeOH with 10 mL 0.1 M KOH solution. The other simulated solutions were prepared with the same method except for substituting 1 mL MeOH with 1 mL FDCA stock solution, 1 mLEtOH, or 1 mL PrOH (note that alcohols and FDCA stock solution do not require the addition of 750 μL water). 1 mL of each solution was used for the ERSS measure. The simulated solutions with FA in 1 M KHCO3 (99.7%) or 0.5 M K2CO3 (99.5%) were prepared by mixing 4 mL FA stock solution with 40 mL 1 M KHCO3 or 0.5 M K2CO3 solution. For continuous ERSS operation, the simulated electrolyte was a mixed solution of 0.1 M KOH and 0.074 v% FA and 1 M KOH and 0. 4 v% FA. All solutions are freshly prepared and used immediately.

Calculation of ERSS performance

The yield (Y1) of KOH electrolyte recovery was determined by measuring the OH− concentration through acid-base titration. The specific experimental steps are as follows: First, take 0.5 mL of the cathodic electrolyte and transfer it to a conical flask containing phenolphthalein reagent. The solution turns immediately red. Next, the solution is titrated with 0.01 M H2SO4 solution until the solution becomes colorless, and the volume of sulfuric acid solution used is recorded. Finally, calculate the KOH electrolyte recovery yield using the following formula:

Y1 is the yield of KOH electrolyte recovery, A is the OH− concentration obtained from acid-base titration, and B is the OH− concentration of the initial solution.

The yield (Y2) of product separation was determined by testing the product concentration before and after the ERSS operation through H1-NMR spectra. The product separation yield was calculated by using the following formula:

Y2 is the product yield after separation, S1 is the product concentration after the ERSS operation, and S2 is the product concentration before the reaction.

The CO2 yield (Y3) was calculated according to the following formula:

Y3 is the yield of CO2. V1 is the actual volume of CO2 produced. V2 represents the calculated CO2 volume from the mole of KHCO3 or K2CO3. For example, 10 mL of 0.5 M K2CO3 solution, V2 = 0.01 L × 0.5 mol/L × 24.5 L/mol × 1000 mL/L = 122.5 mL (25 °C)

Here, we defined the Faraday efficiency (FE1) of the KOH recovery and calculated it according to the following formula:

FE1 is the Faraday efficiency of the KOH recovery, Q2 denotes the coulombs obtained from the electrochemical workstation, and Q1 is the number of coulombs calculated based on the concentration of recovered KOH. For example, The KOH recovery electrolyte is 10 mL 0.1 M, Q1 = 10 mL × 0.1 mol/L × 96485 C/mol × (1/1000) L/mL = 96.485 C.

Here, we also defined the Faraday efficiency (FE2) of CO2 and calculated it according to the following formula:

FE2 is the Faraday efficiency of CO2, Q2 denotes the coulombs obtained from the electrochemical workstation, and Q3 is the number of coulombs calculated based on the collected volume of CO2. For example, if the ISM chamber contains KHCO3 electrolyte, which undergoes a single-electron reaction, and the volume of CO2 collected is 100 mL, Q3 = 0.1 L / 24.5 L/mol × 96485 C/mol = 393 C. The corresponding data was measured once in a strictly standardized manner.

Preparation of 2D-Bi catalyst

Catalyst Preparation: Bismuth-based catalysts were prepared according to methods previously reported in the literature13. Specific synthesis steps involved dissolving 970 mg Bi(NO3)2 · 5H2O in 60 mL of deionized water and adding 500 mg CTAB. Next, 3.0 g urea was added to 40 mL ethanol, and the solution was sonicated to form a uniform mixture. Then, the urea-ethanol solution was rapidly added to the Bi(NO3)2 · 5H2O aqueous solution, followed by 30 min of vigorous stirring to form a white homogeneous solution. Finally, the solution was maintained at 90 °C in a water bath for 4 h, and a white Bi6O6(OH)(NO3)·1.5 H2O powder was collected by centrifugation. The collected white powder was washed with deionized water and ethanol and dried at 60 °C. Subsequently, 10 mg of the prepared white powder was mixed with 2 mL ethanol and 40 μL Nafion solution (3 A, 5%w/w in water and 1-propanol). The mixture was then sonicated for 20 min to obtain a homogeneous ink. The catalyst was sprayed onto a gas diffusion electrode using an electric spray gun for subsequent electrochemical CO2R testing.

CO2R performance test

Our continuous-flow electrolyzer for the electrochemical CO2R was meticulously designed. All electrochemical CO2R procedures were conducted on the BioLogic VMP3 workstation. A Bi-based catalyst was uniformly sprayed onto carbon paper with a hydrophobic microporous layer. Iridium oxide was electrodeposited onto titanium mesh (TaoBao Store) as the anode with a working area of 1 cm2. The cathode and anode were separated by an anion exchange membrane (AEM) (Fumasep FAB-PK-130, Fuel Cell Store). A 1.0 M KOH electrolyte was pumped at a 10 mL/min flow rate and circulated separately through the anode and cathode compartments. Simultaneously, CO2 was continuously passed through the gas flow channel on the backside of the cathode catalyst at a rate of 40 sccm.

The gas products (C2H4, CH4, H2, and CO) were meticulously detected every 8 min using an online gas chromatograph (GC, Shimadzu GC2014), which was equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD), a flame ionization detector (FID), and a TDX-01 column. The carrier gas used was Ar (99.99%). 1H NMR was used to study liquid products (FA, EtOH, and PrOH). Typically, 500 µL of electrolyte was mixed with 100 µL of deuterated water (D2O, Sigma Aldrich, 99.9% deuterium atoms) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma, 99.99%) as an internal standard, ensuring the precision of our liquid product analysis.

Data availability

Relevant data supporting the key findings of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Information file. All raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Li, Xing et al. Redox-tunable lewis bases for electrochemical carbon dioxide capture. Nat. Energy. 7, 1065–1075 (2022).

Rochelle, G. T. Amine scrubbing for CO2 capture. Science 325, 1652–1654 (2009).

Keith, D. W. et al. A process for capturing CO2 from the atmosphere. Joule 2, 1573–1594 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Redox-tunable isoindigos for electrochemically mediated carbon capture. Nat. Commun. 15, 1175 (2024).

Zhu, P. et al. Continuous carbon capture in an electrochemical solid-electrolyte reactor. Nature 618, 959–966 (2023).

Arquer, F. P. Gd et al. CO2 electrolysis to multicarbon products at activities greater than 1 A cm−2. Science 367, 661–666 (2020).

Li, F. et al. Molecular tuning of CO2-to-ethylene conversion. Nature 577, 509–513 (2020).

Ren, S. X. et al. Molecular electrocatalysts can mediate fast, selective CO2 reduction in a flow cell. Science 365, 367–369 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. Electrochemical CO2-to-ethylene conversion on polyamine-incorporated Cu electrodes. Nat. Catal. 4, 20–27 (2020).

Ma, W. et al. Electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to ethylene and ethanol through hydrogen-assisted C–C coupling over fluorine-modified copper. Nat. Catal. 3, 478–487 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Directing CO2 electroreduction pathways for selective c2 product formation using single-site doped copper catalysts. Nat. Chem. Eng. 1, 159–169 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Efficient electrosynthesis of n-propanol from carbon monoxide using a Ag–Ru–Cu catalyst. Nat. Energy. 7, 170–176 (2022).

Xia, C. et al. Continuous production of pure liquid fuel solutions via electrocatalytic CO2 reduction using solid-electrolyte devices. Nat. Energy. 4, 776–785 (2019).

Huang, J. E. et al. CO2 electrolysis to multicarbon products in strong acid. Science 372, 1074–1078 (2021).

Gu, J. et al. Modulating electric field distribution by alkali cations for CO2 electroreduction in strongly acidic medium. Nat. Catal. 5, 268–276 (2022).

Nabil, S. K. et al. Acid-base chemistry and the economic implication of electrocatalytic carboxylate production in alkaline electrolytes. Nat. Catal. 7, 330–337 (2024).

Digdaya, I. A. et al. A direct coupled electrochemical system for capture and conversion of CO2 from oceanwater. Nat. Commun. 11, 4412 (2020).

Willauer, H. D. et al. Development of an electrochemical acidification cell for the recovery of CO2 and H2 from seawater II. Evaluation of the cell by natural seawater. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51, 11254–11260 (2012).

Willauer, H. D. et al. Development of an electrochemical acidification cell for the recovery of CO2 and H2 from seawater. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 50, 9876–9882 (2011).

Willauer, H. D. et al. Feasibility of CO2 extraction from seawater and simultaneous hydrogen gas generation using a novel and robust electrolytic cation exchange module based on continuous electrodeionization technology. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 53, 12192–12200 (2014).

Willauer, H. D. et al. Development of an electrolytic cation exchange module for the simultaneous extraction of carbon dioxide and hydrogen gas from natural seawater. Energy Fuels 31, 1723–1730 (2017).

Seo, H. & Hatton, T. A. Electrochemical direct air capture of CO2 using neutral red as reversible redox-active material. Nat. Commun. 14, 313 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Electrochemically mediated carbon dioxide separation with quinone chemistry in salt-concentrated aqueous media. Nat. Commun. 11, 2278 (2020).

Jin, S. et al. Low energy carbon capture via electrochemically induced pH swing with electrochemical rebalancing. Nat. Commun. 13, 2140 (2022).

Gao, S. et al. Partially oxidized atomic cobalt layers for carbon dioxide electroreduction to liquid fuel. Nature 529, 68–71 (2016).

Natsui, K. et al. Stable and highly efficient electrochemical production of formic acid from carbon dioxide using diamond electrodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 2639–2643 (2018).

Min, X. & Kanan, M. W. Pd-catalyzed electrohydrogenation of carbon dioxide to formate: High mass activity at low overpotential and identification of the deactivation pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4701–4708 (2015).

Lei, F. et al. Metallic tin quantum sheets confined in graphene toward high-efficiency carbon dioxide electroreduction. Nat. Commun. 7, 12697 (2016).

Jiang, B. et al. Boosting formate production in electrocatalytic CO2 reduction over wide potential window on pd surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2880–2889 (2018).

Hoffman, Z. B. et al. Electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to syngas and formate at dendritic copper–indium electrocatalysts. ACS Catal. 7, 5381–5390 (2017).

Gao, S. et al. Ultrathin Co3O4 layers realizing optimized CO2 electroreduction to formate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 698–702 (2016).

Yang, H. et al. Selective CO2 reduction on 2d mesoporous Bi nanosheets. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1801536 (2018).

He, S. et al. The p‐orbital delocalization of main‐group metals to boost CO2 electroreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 16114–16119 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Controllable synthesis of few‐layer bismuth subcarbonate by electrochemical exfoliation for enhanced CO2 reduction performance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13283–13287 (2018).

Zhong, H. et al. Bismuth nanodendrites as a high performance electrocatalyst for selective conversion of CO2 to formate. J. Mater. Chem. A. 4, 13746–13753 (2016).

Han, N. et al. Ultrathin bismuth nanosheets from in situ topotactic transformation for selective electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to formate. Nat. Commun. 9, 1320 (2018).

Kar, S. et al. Catalytic furfural/5-hydroxymethyl furfural oxidation to furoic acid/furan-2,5-dicarboxylic acid with H2 production using alkaline water as the formal oxidant. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 1288–1295 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22471077, 21971070), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2021A1515010091), Guangdong Innovative and Entrepreneurial Research Team Program (2019ZT08L075), Guangdong Pearl River Talent Program (2019QN01L159), Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (202103040002) for financial support. X.W. acknowledges the support from the ECS grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Project No. 21300323) and the CityU start-up fund (Project No. 9610600).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P W, A P, and Z C. prepared the ERSS and conducted the reaction tests. P. W. performed the TEM and data analysis. P. W. and P. S. contributed to thorough discussions on this work. C. H., N. Z., and X.W. contributed to the flow cell’s design, preparation, operation, and discussion of the ERSS. P. W., A. P., and G. C. proposed the idea, designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. G. C. supervised and coordinated all investigators for this project. P. W, A P., and Z. C. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jingjing Duan, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, P., Pei, A., Chen, Z. et al. Integrated system for electrolyte recovery, product separation, and CO2 capture in CO2 reduction. Nat Commun 16, 731 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56111-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56111-6

This article is cited by

-

Realizing the practical application of CO2 electroreduction for urban wastewater denitrification

Nature Water (2025)

-

The promises and reality of metal–CO2 batteries

Nature Reviews Clean Technology (2025)

-

An electrochemical–biological hybrid system meets wastewater

Nature Water (2025)

-

Operando-electrified solvay process

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Dual S-scheme heterojunction nanocomposite-driven charge transport for photocatalytic green energy production and environmental implementations—where to go?

Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials (2025)