Abstract

Previous estimates of deep soil inorganic nitrogen (N) reservoirs have been mainly limited to desert soils, however, recent evidence suggests that deep soil pools are far more ubiquitous across biomes and therefore may be important for global N budgets. Here, we used observations from 280 deep soil profiles (2-205 m) across a wide array of ecosystem and land cover types to seek insight into the full geospatial variation of deep soil nitrate. Using a random forest machine learning approach we estimate a total deep soil nitrate pool of 15.2 ( ± 1.1 SD) Pg of N. When included in the global soil N pool, our estimates of deep soil N increase the global N storage budget by 16%. Estimating these deep soil N pools continues to add to our understanding of soils as a fate for anthropogenically fixed N, and the critical role that deep soils play in our biosphere.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biologically available soil nitrogen (N) limits primary productivity across much of Earth’s surface1, influencing crop production in certain parts of the world2 and limiting vegetative growth that would otherwise buffer against climate change by removing atmospheric carbon dioxide3,4. Despite its importance, and a multitude of advances in various areas of N cycling research, reactive N storage in environmental reservoirs remains one of the largest uncertainties in our understanding of N budgets5. While observations have found soils as deep as 250 m6, global estimates of soil N are typically based on surface soil measurements in the top meter of soil (or less) and often omit N stored at depth. Based mainly on surface soil measurements (≤ 1 m), our current estimates of global N pools range from 5.4 to 335 Pg (Table S1), with 95 Pg N most often cited7. However, large amounts of N can be stored in soils deeper than 1 m and these pools of N are highly variable across space. Considering that deep soils have the capacity to retain large amounts of N8, incorporating these pools into global estimates has the potential to increase the global soil N budget.

While most of the world’s N is retained in the earth’s core and in our atmosphere, the pools that are ecologically relevant are primarily those that cycle amongst our biota. Soils comprise the largest pool of N in the terrestrial biosphere, with most existing as organic N. Inorganic N pools comprise a smaller percentage of soil N but play a disproportionately important role in ecosystems. Nitrate (NO3−) and ammonium (NH4+), two forms of inorganic N, are the most readily available forms for biotic uptake, with NO3− being scarce where N cycles tightly9. While estimates of global soil N are common (Table S1), those of global NO3− remain rare. Nitrate is also of particular interest as this form of N is highly mobile and chemically reactive, thus contributing significantly to environmental N pollution10. Despite its importance, there has yet to be a spatially explicit synthesis of global soil NO3− pools.

Large pools of NO3− have been found to accumulate in deep soils around the world. Researchers have found evidence of deep soil NO3− accumulation in a variety of biomes, including tropical11, desert8, and temperate12 ecosystems. The prevalence of these sizable deep soil N pools is likely to vary geographically and do not necessarily correlate with surface soil NO3− concentrations. Factors that control their prevalence include N input rates such as fertilization, deposition, or fixation that promote nitrification; anion exchange capacity or hardpans that can constrain NO3− mobility; and loss rates such as leaching, denitrification, and biologic uptake13. Precipitation, temperature, soil pH, soil texture, and the degree of geologic weathering can all affect these processes, indirectly influencing soil N storage. An understanding of the size and geographic distribution of deep soil NO3− stocks will require an understanding of controls on the pools and the geographic distribution of said factors.

Here, we address two major gaps in our current soil N budget estimates: (1) most global N budgets do not include deep soil N, and (2) global soil NO3− budgets have yet to be spatially quantified. Given that there are no robust global estimates of soil NO3−, but evidence of NO3− pools in deep soils globally, we sought insight into the full geospatial variation of NO3− pools in deep soils across a wide array of ecosystems and how this contributes to our understanding of soil N budgets globally. We performed a systematic review of deep soil NO3− pools (≥ 2 m deep) and coupled results from our synthesis with a machine learning approach to produce spatially explicit global estimates of deep soil NO3−. We hypothesized that deep soil NO3− pools could significantly increase the global N budget and discussed the potential ecological significance and fate of these understudied pools.

Results and Discussion

Global synthesis of field measured deep soil nitrate pools

Our observational synthesis generated data for 363 soil profiles (ranging from 2 to 205 m in depth) that reported inorganic N and 280 soil profiles that reported soil NO3− from 57 studies that spanned tropical, temperate, and arid ecosystems (Figures S1 and S2). While most soil profiles were sampled up to 5 m (72%), a considerable portion were sampled between 5–15 m deep (21%), while our deepest profile extended down to 205 m (Table S2). Results from our synthesis indicated that deep soil NO3− pools ranged from 0–13,600 kg N ha−1, with a median of 218 kg N ha−1, regardless of sampling depth. The observations with the largest deep soil NO3− pools ( > 10,000 kg N ha−1) were all located in arid regions of the southwest United States and within natural ecosystems, followed by a group of more temperate sites located mainly in China and under cultivation (4000–8000 kg N ha−1), with the vast majority of sites having smaller deep soil NO3− pools and spanning a much wider breadth of climates and land use (see Data Availability Statement for raw data). Forested/woodland soil profiles ranged from 10–282 kg N ha−1 (median = 49 kg N ha−1), croplands ranged from 0–8050 kg N ha−1 (median = 254 kg N ha−1), deserts ranged from 5–12,900 kg N ha−1 (median = 78 kg N ha−1), and grass/shrublands ranged from 24–13,600 kg N ha−1 (median = 161 kg N ha−1, Figure S3). Smaller deep soil NO3− pools in forests may be attributed to the occurrence of large or deep-rooted trees that have the potential to uptake deep soil N or create preferential flow pathways13. Alternatively, smaller deep soil NO3− pools in forests may be explained by the fact that climate co-varies with ecosystem type, and wetter environments are more likely to support forests as well as conditions for N loss pathways such as leaching and denitrification14.

Modeled estimates of global deep soil nitrate pools

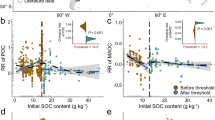

We coupled results from our synthesis with machine learning approaches to generate spatially explicit N budget estimates for deep soils. We considered climate, soil properties, plant biomass, and human activity as the predictors to build the global model (see Methods section for details). By using the Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) method, we found the most important of selected predictors for global soil NO3− prediction were soil depth, rock N weathering rate, aridity index, fertilizer application rate, and temperature (Figure S4 and S5). Following RFE, we used three machine learning models (RF, random forest regression; CUBIST, cubist; GBM, stochastic gradient boosting) to train the dataset, and RF provided the best fit (R2 = 0.38; Figure S6). The RF model generated 2.6 Pg N in cropland soils, 2.0 Pg N in grasslands, 5.1 Pg N in forest soils, and 5.5 Pg N in desert soils (Table 1, Figure S7). Together, deep soil NO3− pools equate to 15.2 ( ± 1.1 SD) Pg of N, with the largest pools having the highest degree of variation (Fig. 1). When we add this to the existing 95 Pg of soil N globally7, based on measurements taken in the top 1 m of soil, our estimates of deep soil NO3− increase the global soil N budget by 16% (Table S1). However, the magnitude by which our estimates increase the global N budget is dependent on the global soil N estimate used. Because estimates of total soil N are quite variable, ranging from 5.4 to 335 Pg, deep soil NO3− pools could increase the N budget anywhere from 5–281% (Table S1).

To our knowledge, there have previously been a handful of attempts to quantify global soil N, which were quite variable (Table S1), however, these did not include deep soil NO3− pools (≥ 2 m). Approaches in the way previous global soil N estimates were made varied and appear to affect the outcome (Table S1). While a few publications used soil profile measurements and spatial methods to make global estimates of soil N, many relied on published estimates of already scaled N pools and/or used stoichiometric ratios for scaling. In a few cases, the methodology used to derive soil N estimates was not available and/or the estimates were not reproducible. Those estimates that used soil core data and spatial methods to produce global soil N estimates range from 65–105 Pg N, which we assume to be more reliable than others given their transparent and more sophisticated methodology. Furthermore, while other soil N estimates may partition between soil type or reservoir, we found none that distinguished between agricultural and natural ecosystem stocks. Our analysis builds upon previous estimates of soil N by including deeper soil N pools, advances the methodology available to derive global soil N estimates, and provides ecosystem specific estimates.

To our knowledge, only one previous paper has attempted to estimate deep soil N. Walvoord et al.8 estimated soil NO3− reservoirs in arid lands by extrapolating N measurements from 30 m deep soil solution measurements taken from five arid sites in the southwest United States. They estimated that 3–15 Pg N (mean of 9 Pg N) can be found in deep soil from arid regions globally. By adding their N estimates to existing budgets, they found that deep soil N increased global estimates by 3–16%. We take this approach further by synthesizing new soil NO3− measurements at a global extent (Figure S1). While our deep soil NO3− estimates (15.2 Pg N) increase the global N budget, our estimates are smaller than Walvoord et al.8 estimates; we estimate 5.5 Pg N in deserts. Furthermore, we estimate 12.6 Pg N for all natural ecosystems (10.4 × 109 ha), comparable to Walvoord et al.8 estimate for deserts despite covering a much larger area than deserts (3 × 109 ha). One explanation for the difference in estimates is that Walvoord et al.8 extrapolated measurements from arid regions with particularly large deep soil NO3− pools, while the broader range of ecosystems included here typically have smaller N reservoirs. Another explanation is that Walvoord et al.8 included the top 2 m of soil in their estimates, which typically have higher soil N stocks, whereas we did not. For example, in another study, Post et al.7 estimated 21 Pg of N in the top meter of desert soils alone. Finally, our approach differs from Walvoord et al.8 in that our analysis included measurements deeper than 30 m (Table S2) and included soil extract measurements of NO3−. From our dataset, soil extract measurements of NO3− were lower on average (Figure S9) than soil solution measurements used by Walvoord et al.8 as extractable soil N is likely a more stable pool than soil solution measured N. Notably, soil N measurement methodology covaried with biome, whereby most soil solution measurements were made in deserts.

Our analysis shows high degrees of spatial variability in deep soil N pools, the mechanisms for which are not robustly characterized and may vary geographically. In highly weathered clayey soils, such as those in Australia, sub-Saharan Africa, Costa Rica, and Brazil13,15,16,17, deep soil NO3− has been found to covary with anion exchange capacity. This is because highly weathered tropical soils with variable charge 1:1 clays can develop net anion exchange capacity at low pH, which allows them to hold large quantities of NO3− 16. This contrasts with less weathered temperate soils in which NO3− is typically quite mobile. Previous researchers have found that soil anion exchange capacity explained the magnitude of NO3− accumulation in tropical soils at depth (down to 8 m)13,17 and that large soil N pools were consistent with a higher density of binding sites and anion exchange capacity16. In China, we saw instances where ecosystem/management played a role, as deep soil N pools were higher beneath croplands than grasslands12. In arid soils, subsurface NO3− accumulation is typically found 1–2 m down, below what is considered the active rooting zone18. One key factor contributing to NO3− accumulation in desert soils is the establishment of a persistent hydraulic sink at the base of the soil. Nitrate accumulation in desert sites is estimated to range from 10,000 to 16,000 years, consistent with the onset of arid Holocene climatic conditions and shifts to xeric vegetation that triggered subsoil NO3− retention8. Nitrogen cycling processes have been relatively constant since the Pleistocene/Holocene transition19 and modern factors furthering subsoil NO3− accumulation are considered to be diminished soil resources (water and organic carbon) and rare leaching events18. Even within croplands, we found that arid soils tend to hold more N, suggesting an important role of soil characteristics and climate in driving N retention and losses.

We found soil depth, rock N weathering rate, and aridity index were the best predictors of soil NO3−. Deep soil NO3− also increased with fertilization rate. These findings imply that fertilizer inputs in managed croplands impact subsurface reservoirs, providing further evidence that, as others have suggested, these deep soil N pools are dynamic and have the potential to minimize losses to waterways13,15. We were surprised to find that croplands had relatively small soil N pools (2.6 Pg N) compared to other ecosystems (Table 1), and this likely speaks to the multitude of factors that influence deep NO3− storage. In addition to N inputs, deep soil N accumulation can be influenced by vegetation, rooting depth, rainfall, leaching, denitrification, and soil characteristics that promote anion exchange capacity or hardpan development, among other factors. It is unclear why croplands have smaller N pools than natural ecosystems, but this may be that agriculture in temperate regions lack anion exchange capacity to retain N, N inputs are typically targeted to reach crops through precision fertilization techniques, agricultural soils have high rates of denitrification that remove N from surface soils, and that irrigation of well-drained agricultural soils promotes downward movement of the remaining N to groundwater.

While we compiled the most comprehensive database of deep soil N measurements for this study, 280 soil profiles remains a low sample size for machine learning, increasing the uncertainty of our estimates. We acknowledge the limitations of scaling field measurements via machine learning, which functions much better when the data cover the range of predictor values20. Due to the intensive nature of sampling deep soils, our analyzes were limited by available data and representative distribution across our predictors. In particular, our estimates were highly driven by soil depth, however, when we look at the distribution of study sites included in our synthesis, few measurements were taken in the deepest soils (50–250 m; Figure S2), suggesting a need for more soil N measurements in those regions to better understand and extrapolate soil NO3− stocks to the greatest soil depths. Furthermore, the majority of data we used to train and validate the model were in the upper 2–5 m of soil, thus our analysis has a depth-related limitation due to sample size. Although 30% of data points were deeper than 5 m, our results would have higher prediction accuracy if more data > 5 m were available. Thus, we present the uncertainty of our spatially explicit estimates through the standard deviation (Fig. 1B).

While the geographic distribution of our synthesis exceeded those of previous studies, there were still notable gaps that may bias our spatially explicit estimates. We found arid soils from natural ecosystems to have the highest N pools (Table 1), however, we lack observations from key regions such as the Saharan desert and the Middle East, even though these are some of the regions contributing the most to our global total. Tropical soil observations were scarce, given the depth of these soils and their potential for anion exchange capacity13,15, more deep soil measurements should be taken in the tropics. High latitude soils data are also underrepresented in our synthesis; thus, we did not account for permafrost in our model, which can store large amounts of N21. Finally, we based our analysis on instantaneous measurements of soil NO3− from publications that spanned decades and thus provide a global estimate rather than one for a particular point in time. Since soil NO3− is highly mobile, it is likely that patterns will change over time. A more robust database of deep NO3− measurements made in conjunction with potential drivers could enable a mechanistic understanding that would allow for improved process-based modeling, while repeated measurements would allow us to understand whether these deep soil N pools are dynamic in time. Despite the uncertainties, we consider our estimates to represent the most current state-of-the-art understanding. Future research should include measurements of other deep soil N pools and develop approaches to investigate the dynamics of deep soil N in response to anthropogenic activity.

Potential implications for deep soil nitrate pools

While the implications of deep NO3− to the global N budget are clear, the potential of deep soil NO3− to leach out of soils and affect downstream ecosystems, and the biological relevance to plants are still relatively unknown. The former may depend on the depth to groundwater and anion exchange capacity of the soil, and the latter may depend on the rooting depth and accessibility of NO3−, the main form of N that plants take up, to deep roots. Estimating these deep soil N pools continues to add to our understanding of soils as a fate for anthropogenically fixed N, and the critical role that deep soils play in our biosphere.

Deep soil N pools may represent less mobile reservoirs of NO3− compared to aquatic and terrestrial surface pools of NO3− that actively contribute to environmental pollution. Deep soil N is less susceptible to denitrification22, which converts soil NO3− into the air pollutant nitric oxide or the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide. The lower susceptibility to denitrification is attributed to microbial biomass, where half is typically found in the top 10 cm of soil and decreases dramatically with depth23. Leaching of limiting nutrients like N can contaminate groundwater and cause eutrophication in rivers, lakes, and coasts24,25. Leaching is primarily influenced by precipitation or irrigation, but abiotic soil properties can play a role as well. Some data suggest that the deep NO3− pools may attenuate against leaching to ground water in croplands where N fertilizer is applied13. In a cropland soil, Weitzman et al.26 found that ~44% of surface N was removed in crop harvest, ~29% was leached into groundwater, while ~27% was retained along 3 m deep soil profiles. Still, there is much to understand about soil N turnover rates and the speed with which land use change can influence this N pool. Correlations between deep soil N pools and fertilizer application rate suggest that these reservoirs can be influenced by N inputs to surface soils. The dynamics of these deep soil N pools depends on the balance between inputs (e.g., N fertilizer applications, N fixation, N deposition, etc.) and losses (e.g., leaching, denitrification, etc.), as well as the mechanisms that retain N. For instance, if anion exchange capacity is the primary mechanism for the storage of soil NO3− at depth, it’s possible that there is a finite amount of charge, that once saturated will no longer allow deep soils to protect against leaching13,27. More research is needed to better understand the extent to which deep soil can hold fertilizer N on soils surfaces and thus reduce leaching or if this pool is dynamic and actively cycles amongst biota, surface soils, and atmospheric reservoirs.

One potential fate of deep soil N is uptake by deep-rooted vegetation. Our synthesis focuses on soils deeper than 2 m, and includes measurements as deep as 205 m. While there is strong evidence for deep roots well below 2 m across many ecosystems28, as well as support for their role in the hydrologic and carbon cycles29, it is still unclear if these roots can access deep pools of NO3−. Shallow, fine roots play a more important role in NO3− uptake for plants, but deep-rooted taproots may still be able to access NO3− 30. Root depth varies by ecosystem and climate, with some of the deepest roots occurring in forests, deserts, and tropical grasslands28. While we find evidence of smaller NO3− pools in forests, we find the opposite for deserts, despite both being relatively deeply rooted ecosystems. In croplands, most species are short rooted and thus seemingly unlikely to access deep soil N, however, some cropland roots have been documented as deep as 4 m31 and common crops like alfalfa and soybean have roots as deep as 2 m32. Within agricultural studies that examine the role of plants in taking up fertilizer N, there is support for the ability of deep-rooted plants to access NO3− below the surface soils (up to 3.9 m)33,34,35. For example, Kristensen and Thorup-Kristensen36 found that fodder radish captured 80% of the NO3− up to 2.5 m. Deep-rooted plants likely can access and take up NO3−37, but this still needs to be investigated outside of agricultural settings. Future research should explore the relationship between root characteristics and deep soil N uptake, as well as their relevance to plant productivity.

Annual inputs of N to the biosphere typically exceed N outputs suggesting a pool of missing N, or a sink that remains under/unaccounted. Our finding suggest that deep soils may play a role in unearthing this missing N sink. Galloway et al.5 suggested that about 175 Tg of N were missing from the global N budget in the early 1990s, and that 115 Tg of that N was estimated to be denitrified to the atmosphere, while the remaining 60 Tg was assumed to be routed to storage in biomass and soils. While denitrification and N storage in soils remain the most poorly constrained aspects of the N cycle5, our estimate of 15.2 Tg N in deep soils (which increases the soil N budget by 16% but accounts for 25% of presumed terrestrial storage) contributes evidence for soils as a substantial N sink. The partitioning of anthropogenically-fixed N entering the biosphere between denitrification and soil storage remains an area that requires more research and new techniques to advance38.

For the last 30 years, the narrow concept of soil has been challenged, as many argue for a new conception of soils and ecosystems that extends to deeper depths39,40,41,42. Soil is biologically active much deeper than has been thought by many ecologists. Thus the lower boundary of soil should extend into the C horizon, which ranges from shallow to very deep, sometimes extending many meters in depth39,40. Deep soils represent important stores of nutrients and carbon that are poorly understood and rarely sampled41. Richter et al.43 estimated that the median depth to which soils were being sampled by ecologists interested in carbon was 15 cm and that 90% of ecologically-relevant studies sampled only the upper 30 cm. Natural and anthropogenic terrestrial activity significantly affects biogeochemistry throughout soil profiles, however, the lower boundaries of most terrestrial ecosystems have been demarcated too shallow to facilitate a complete understanding of ecosystem structure and function. For example, accurate assessments of photosynthetically-fixed carbon requires accounting of respiratory CO2 and carbonic acid to the base of the critical zone42. A good illustration of our bias in studying N cycling in surface soils is the recently discovered extent to which rock weathering influences soil N cycling and aboveground ecosystem dynamics44. Critical zone science aims to highlight the interconnectedness of the plant-soil-water-rock continuum, but this approach has been embraced more widely by hydrologists and geologists than by soil scientists. Unique processes, depth dynamics, and the large volumes of deep soils make them an integral part of understanding biogeochemistry beyond the surface.

Soil N estimates are critically important as they have implications for global and regional N budgets, resource management, and feedbacks to climate change. Soil nutrient status not only influences N loss rates45 and limits the ability of soils to sequester carbon4 but is also a key factor in determining the ability of vegetation to buffer against climate change46. Deep soil N can promote the redistribution of new organic carbon to deeper soil layers, furthering the potential capacity for carbon sequestration in soils47. Nitrogen fertilizer currently supports about half the world’s population, but a doubling of N in our biosphere has also resulted in widespread pollution of our water and air10. Deep soils have the potential to function as a sink for N pollution in the environment and better quantification of such N pools can help us to understand how anthropogenic activity has altered the N cycle. Deep soil N pools may have implications for vegetation and crop production, as well as water and air quality, and their quantification can help inform scientific questions that rely on robust N budgets. A deeper understanding of the global N cycle will improve our ability to model biotic thresholds related to food production, environmental pollution, and climate change.

We conclude that terrestrial N pools are likely larger than previous estimates. When we include deep soil N pools, global soil N budgets increase 5–281%, depending on the soil N estimate used. This is perhaps not surprising given that our current N budget is based on just the top meter of soil and does not account for up to hundreds of meters of soil N at depth. While much of soil biogeochemistry focuses on surface soil measurements, there remains a need for studying deep soils, not only for their capacity to store N and subsequently reduce N pollution, but for their role in other critical processes such as organic carbon storage. We emphasize the need for understanding deep soils in the context of global change, as they will continue to play a critical role in ecosystem function.

Methods

Observational synthesis

We searched Web of Science using the search term (((deep AND soil) OR subsoil) AND (nitrate OR (mineral AND nitrogen))) in January of 2020, which generated 5225 results. We extracted data from papers that reported N stock (kg ha−1) for the soil profiles below 2 m, measured either as soil extracts or from soil solution (NH4+, NO3−, total N). Our literature review generated data from 363 soil profiles from 57 studies (all between 2 and 205 m deep). Our data set included 68 study sites that spanned tropical, temperate, and arid ecosystems. Among soil profiles, 76% reported only NO3−, 4% reported only ammonium (NH4+), and 30% reported total inorganic N (in sum or as NO3− and NH4+). Because NO3− pools were on average an order of magnitude higher (787 kg NO3−-N ha−1 and 47 kg NH4+-N ha−1), with a larger sample size, we chose to focus our analysis on observations of deep NO3−, which limited our analysis to the 280 profiles. We also collected other soil and environmental data that might influence the accumulation of N in subsurface soils (e.g., climate, pH, anion exchange capacity, soil texture, vegetation type, land use-history (including historical fertilization rates), N deposition rate, depth to bedrock, and soil type). A list of all data collected in the observational synthesis is linked to in the Data Availability Statement, some of which were used in the machine learning analysis (see the Global depth soil NO3−-N modeling section below). We included only analyzes that report N stock (soil inorganic N on a per area basis) and did not include those that only report soil N concentration data, except in a handful of circumstances where concentration data were scaled to round out gaps in the dataset (mainly, a lack of data in tropical ecosystems).

Global depth soil NO3 −-N modeling

Based on previous studies, we identified mean annual precipitation (MAP), mean annual temperature (MAT), aridity index (AI), potential evapotranspiration (PET), soil depth, soil pH, plant biomass, rock N weathering rate, clay content, and fertilizer addition rate as predictors to predict variation in deep soil NO3−6,48,49,50,51. When a variables’ value was not reported in the original paper, we extracted the values for each observation from the global database (see below for the database sources).

To select a representative group of auxiliary variables, we utilized the Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) method available in the caret package48. RFE is an algorithm designed for backward selection of predictors. This technique initially constructs a model with all predictors and evaluates the importance of each predictor in this model. Subsequently, it removes the least important predictor and rebuilds the model49. One of the advantages of RFE is its ability to mitigate the effect of correlation on the importance measure. In this study, we executed RFE with thirteen subsets of variables ranging from 5 to 10. We selected the optimal subset of covariates based on the lowest root mean squared error (RMSE) following a 10-fold cross-validation. After RFE selection, we found soil depth, fertilizer N application rate, AI, MAT, and rock N weathering rate were the most important variables in the global NO3− model with the lowest RMSE, thus we used those in our analysis.

Due to potential nonlinear relationships between soil NO3− and environmental variables, we used an ensemble machine learning method to build a global deep soil NO3− model. We compared three machine learning methods (RF, random forest regression; CUBIST, cubist; GBM, stochastic gradient boosting; Figure S6) with the same variables previously selected to assess the most accurate model of NO3− stocks.

To build the models, we separated the dataset randomly into a training subset (60% of the total observations) and a testing holdout subset for validation (40% the total observations). We used 10-fold cross-validation with five repetitions with the training data to access the variability of the predictions (Figure S8). The average value of root mean squared error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and R-square (R2) will get statistical metrics for the model’s performance. Finally, we used the testing holdout data to evaluate the final model’s performance (Figure S8). The importance of each predictor was calculated as the percentage increase in the mean standard error (Figure S4). The mean marginal effect of each value of a given predictor to the final prediction was visualized by using a partial dependence plot (Figure S5). These model building and validation processes were adapted from Sena-Souza et al.50.

Global depth soil NO3 −-N spatial prediction

Since random forest (RF) best captured geospatial variation in soil NO3− (Figure S6), we used RF to generate the global soil NO3− prediction using the best fit model. The whole dataset (n = 280) was applied to the RF model to create the final soil NO3−-N map globally at a spatial resolution of 10,000 by 10,000 m. We performed the spatial predictions by using the prediction function in a raster package in R (3.5-2, https://rspatial.org/raster) and applying the chosen model to the stacked covariate raster, which includes MAT, AI, soil depth, rock N weathering rate, and fertilizer addition rate. We predicted the NO3−-N map at global scales using RF, then used a land cover map51 to separate the projections in to managed agricultural land (referred to as cropland), grassland, forest, and desert. The built-up water and the other area without soils were removed in our analysis. The standard deviation was generally used to predict the spatial uncertainty from the RF model (Fig. 1). We applied one spatial prediction to RF models in order to generate a map of deep soil NO3− (Fig. 1) and 20 spatial predictions to generate a standard deviation map (Fig. 1).

Global fertilization rate was sourced from Wang et al.52. Global depth of soil to bedrock data were sourced from Pelletier et al.6. (https://daac.ornl.gov/cgi-bin/dsviewer.pl?ds_id=1304). Global soil pH map was derived from Batijes53. The global AI and PET were sourced from Zomer et al.54. Plant biomass data were derived from Spawn and Gibbs55. Soil clay data were sourced from Hengl et al.56. Mean annual temperature and precipitation were derived from Fick and Hijmans57,58. Rock N weathering rate data were from Houlton et al.44. A complete list of references for predictors used in the model can also be found in Table S3. Global land use maps were sourced from FAO GLC-SHARE51 database.

Data availability

Code availability

The global soil nitrate projection input data and R code generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo repository under accession code 13154845.

References

Du, E. et al. Global patterns of terrestrial nitrogen and phosphorus limitation. Nat. Geosci. 13, 221–226 (2020).

Houlton, B. Z., Almaraz, M., Aneja, V., Austin, A. T. & Bai, E. A World of Cobenefits: Solving the Global Nitrogen Challenge. Earth’s. future 7, 865–872 (2019).

Wang, Y. P. & Houlton, B. Z. Nitrogen constraints on terrestrial carbon uptake: Implications for the global carbon-climate feedback. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, 1–5 (2009).

Van Groenigen, J. W. et al. Sequestering soil organic carbon: a nitrogen dilemma. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 11503–11504 (2017).

Galloway, J. N. et al. Nitrogen cycles: past, present, and future. Biogeochemistry 70, 153–226 (2004).

Pelletier, J. D. et al. A gridded global data set of soil, intact regolith, and sedimentary deposit thicknesses for regional and global land surface modeling. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 8, 41–65 (2016).

Post, W. M., Emanuel, W. R., Zinke, P. J. & Stangenberger, A. G. Global patterns of nitrogen storage. Nature 298, 156–159 (1985).

Walvoord, M. A. et al. A Reservoir of Nitrate Beneath Desert Soils. Science 302, 1021–1024 (2003).

Almaraz, M. & Porder, S. Reviews and syntheses: measuring ecosystem nitrogen status – a comparison of proxies. Biogeosciences 13, 1–9 (2016).

Galloway, J. N. et al. The Nitrogen Cascade. Bioscience 53, 341 (2006).

Jankowski, K. J. et al. Deep soils modify environmental consequences of increased nitrogen fertilizer use in intensifying Amazon agriculture. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–11 (2018).

Jia, X. et al. Mineral N stock and nitrate accumulation in the 50 to 200 m profile on the Loess Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 633, 999–1006 (2018).

Huddell, A., Neill, C., Palm, C. A., Nunes, D. & Menge, D. N. L. Anion exchange capacity explains deep soil nitrate accumulation in brazilian amazon croplands. Ecosystems 26, 134–145 (2023).

Houlton, B. Z. & Bai, E. Imprint of denitrifying bacteria on the global terrestrial biosphere. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 106, 21713–21716 (2009).

Wong, M. T. F., Hughes, R. & Rowell, D. L. Retarded leaching of nitrate in acid soils from the tropics: measurement of the effective anion exchange capacity. J. Soil Sci. 41, 655–663 (1990).

Tully, K. L., Hickman, J., McKenna, M., Neill, C. & Palm, C. A. Effects of fertilizer on inorganic soil N in east Africa maize systems: vertical distributions and temporal dynamics. Ecol. Appl. 26, 1907–1919 (2016).

Harmand, J. M., Ávila, H., Oliver, R., Saint-André, L. & Dambrine, E. The impact of kaolinite and oxi-hydroxides on nitrate adsorption in deep layers of a Costarican Acrisol under coffee cultivation. Geoderma 158, 216–224 (2010).

Menon, M., Parratt, R. T., Kropf, C. A. & Tyler, S. W. Factors contributing to nitrate accumulation in mesic desert vadose zones in Spanish Springs Valley, Nevada (USA). J. Arid Environ. 74, 1033–1040 (2010).

Hartsough, P., Tyler, S. W., Sterling, J. & Walvoord, M. A 14.6 kyr record of nitrogen flux from desert soil profiles as inferred from vadose zone pore waters. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 2955–2958 (2001).

Chen, J., Zhang, Y., Kuzyakov, Y., Wang, D. & Olesen, J. E. Challenges in upscaling laboratory studies to ecosystems in soil microbiology research. Glob. Chang. Biol. 29, 569–574 (2023).

Strauss, J. et al. A globally relevant stock of soil nitrogen in the Yedoma permafrost domain. Nat. Commun. 13, 6074 (2022).

Stone, M. M., DeForest, J. L. & Plante, A. F. Changes in extracellular enzyme activity and microbial community structure with soil depth at the Luquillo critical zone observatory. Soil Biol. Biochem. 75, 237–247 (2014).

Murphy, D. V., Sparling, G. P. & Fillery, I. R. P. Stratification of microbial biomass C and N and gross N mineralisation with soil depth in two contrasting Western Australian agricultural soils. Soil Res 36, 45–56 (1998).

Power, J. F. Y. & Schepers, J. S. Nitrate contamination of groundwater in North America. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 26, 165–187 (1989).

Conley, D. J. et al. Ecology - Controlling eutrophication: nitrogen and phosphorus. Science 323, 1014–1015 (2009).

Weitzman, J. N. et al. Deep soil nitrogen storage slows nitrate leaching through the vadose zone. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 332, 107949 (2022).

Reynolds-Vargas, J. S., Richter, D. D. & Bornemisza, E. Environmental impacts of nitrification and nitrate adsorption in fertilized Andisols in the Valle Central of Costa Rica. Soil Sci. 157, 289–299 (1994).

Canadell, J. et al. Max rooting depth of veg types at global scale. Oecologia 108, 538–595 (1996).

Nepstad, D. C. et al. The role of deep roots in the hydrological and carbon cycles of Amazonian forests and pastures. Nature 372, 666–669 (1994).

Dunbabin, V., Diggle, A. & Rengel, Z. Is there an optimal root architecture for nitrate capture in leaching environments? Plant, Cell Environ. 26, 835–844 (2003).

Canadell, J. et al. Maximum rooting depth of vegetation types at the global scale. Oecologia 108, 583–595 (1996).

Fan, J., McConkey, B., Wang, H. & Janzen, H. Root distribution by depth for temperate agricultural crops. F. Crop. Res. 189, 68–74 (2016).

Kristensen, H. & Thorup-Kristensen, K. Roots below one-meter depth are important for uptake of nitrate by annual crops. In Quantifying and understanding plant nitrogen uptake for systems modeling (eds Ma, L., L. R. Ahuja, & T. Bruulsema) 245-258 (CRC Press, 2008).

Zhou, S. L., Wu, Y. C., Wang, Z. M., Lu, L. Q. & Wang, R. Z. The nitrate leached below maize root zone is available for deep-rooted wheat in winter wheat-summer maize rotation in the North China Plain. Environ. Pollut. 152, 723–730 (2008).

Jama, B., Ndufa, J. K., Buresh, R. J. & Shepherd, K. D. Vertical distribution of roots and soil nitrate: tree species and phosphorus effects. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 62, 280–286 (1998).

Kristensen, H. L. & Thorup-Kristensen, K. Root growth and nitrate uptake of three different catch crops in deep soil layers. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 68, 529–537 (2004).

Pierret, A. et al. Understanding deep roots and their functions in ecosystems: an advocacy for more unconventional research. Ann. Bot. 118, 621–635 (2016).

Almaraz, M., Wong, M. Y. & Yang, W. H. Looking back to look ahead: a vision for soil denitrification research. Ecology 101, 1–10 (2020).

Richter, D. D. & Markewitz, D. How deep is soil? Biosci 45, 600–609 (2016).

Richter, D. D. & Yaalon, D. H. The changing model of soil” revisited. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 76, 766–778 (2012).

James, J. N., Dietzen, C., Furches, J. C. & Harrison, R. B. Lessons on buried horizons and pedogenesis from deep forest soils. Soil Horiz. 56, 1–8 (2015).

Richter, D., de, B. & Billings, S. A. One physical system’: Tansley’s ecosystem as Earth’s critical zone. N. Phytol. 206, 900–912 (2015).

Richter, D. D. B., Bacon, A. R., Brecheisen, Z. & Mobley, M. L. Soil in the anthropocene. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 25, 012010 (2015).

Houlton, B. Z., Morford, S. L. & Dahlgren, R. A. Convergent evidence for widespread rock nitrogen sources in Earth’s surface environment. Science 360, 58–62 (2018).

Hall, S. J. & Matson, P. A. Nitrogen oxide emissions after nitrogen additions in tropical forests. Nature 400, 152–155 (1999).

Terrer, C. et al. Nitrogen and phosphorus constrain the CO2 fertilization of global plant biomass. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 684–689 (2019).

Hu, H., Zhao, L., Tan, W., Wang, G. & Xi, B. Discrepant responses of soil organic carbon dynamics to nitrogen addition in different layers: a case study in an agroecosystem. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 11, 314–325 (2024).

Kuhn, M. Building predictive models in R using the caret package. J. Stat. Softw. 28, 1–26 (2008).

Kuhn, M. & Johnson, K. Feature engineering and selection: a practical approach for predictive models. First edition. Taylor & Francis Group, New York, New York, USA (2019).

Sena‐Souza, J. P., Houlton, B. Z., Martinelli, L. A. & Bielefeld Nardoto, G. Reconstructing continental‐scale variation in soil δ15N: a machine learning approach in South America. Ecosphere 11, e03223 (2020).

Latham, J., Cumani, R., Rosati, I. & Bloise, M. FAO global land cover (GLC-SHARE) beta-release 1.0 database. Land and Water Division (2014).

Wang, C., Houlton, B. Z., Dai, W. & Bai, E. Growth in the global N2 sink attributed to N fertilizer inputs over 1860 to 2000. Sci. Total Environ. 574, 1044–1053 (2017).

Batjes, N. H. Harmonized soil property values for broad-scale modelling (WISE30sec) with estimates of global soil carbon stocks. Geoderma 269, 61–68 (2016).

Zomer, R. J. et al. Global tree cover and biomass carbon on agricultural land: the contribution of agroforestry to global and national carbon budgets. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–12 (2016).

Spawn, S. A. & Gibbs, H. K. Global aboveground and belowground biomass carbon density maps for the year 2010. Ornl Daac 2–6 (2020).

Hengl, T. et al. SoilGrids250m: Global gridded soil information based on machine learning. PLoS ONE 12, (2017).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. Worldclim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315 (2017).

Zomer, R. J., Xu, J. & Trabucco, A. Version 3 of the global aridity index and potential evapotranspiration database. Sci. Data 9, 409 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge funding from National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFE0124000) and International Partnership Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. 064GJHZ2022054FN) to C.W.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A. and M.Y.W. conceptualized the project and performed the synthesis. C.W. performed the modeling analysis. C.W., M.Y.W., and M.A. generated figures and tables. M.A. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to its revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xiaoli Cheng, Shu Kee Lam and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Almaraz, M., Wang, C. & Wong, M.Y. Deep soil contributions to global nitrogen budgets. Nat Commun 16, 966 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56132-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56132-1