Abstract

Plitidepsin is an antitumoral compound safe for treating COVID-19 that targets the translation elongation factor eEF1A. Here we detect that plitidepsin decreases de novo cap-dependent translation of SARS-CoV-2 and non-viral RNAs but affects less than 13% of the host proteome, thus preserving cellular viability. In response to plitidepsin, cells upregulate EIF2AK3 and proteins that reduce translation, but also proteins that support proteostasis via ribosome synthesis and cap-independent translation by eIF4G2 and IGF2BP2. While plitidepsin inhibits cap- or internal ribosome entry sites (IRES)-mediated translation, its impact on N6-methyladenosine (m6A) translation is limited. In agreement, plitidepsin blocks members of Coronaviridae, Flaviviridae, Pneumoviridae and Herpesviridae families. Yet, it fails to inhibit retroviruses that exploit m6A synthesis routes and are blocked by drugs targeting IGF2BP2 m6A reader. By deciphering the molecular fingerprint of cells treated with therapies targeting translation we identify a rational approach to select broad-spectrum antivirals with potential to counteract future pandemic viruses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Long before the COVID-19 pandemic began, infectious diseases were already responsible for one in four deaths worldwide1. Antivirals have helped to reduce and control the high morbidity and mortality caused by infectious diseases1,2. Historically, these compounds targeted viral factors, a strategy with some limitations3, including the need to have an in-depth prior knowledge on the pathogen (which may not always be available for newly emerging viruses such as SARS-CoV-2), a small number of suitable viral targets, and a typically rapid viral evolution causing antivirals to eventually lose potency (as illustrated by several monoclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 that lost efficacy during the Omicron era4).

An interesting and cost-effective approach to tackle all these limitations relies on developing treatments against cellular host factors that are pivotal for the infection of multiple viruses. Host-directed strategies can target conserved cellular factors required for the replication of distinct emerging and/or re-emerging viruses3. As host factors are evolutionarily conserved, these molecules are less prone to the emergence of resistance, since viral evasion requires considerable larger mutational changes2. Host factors are therefore attractive candidates due to their reduced chances of resistance development and their potential for broad antiviral action that can protect against different viruses, including novel threats yet to be discovered.

Having an extensive portfolio of host-directed broad-spectrum therapies ready to deploy in the clinical setting will greatly increase our chances of containing outbreaks or even preventing future pandemics. This need manifested during the surge of the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent estimates indicate that 4 million lives could have been saved if an effective antiviral had been available within 6 months of the start of the pandemic5. Moreover, although effective SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were quickly developed, this is not always possible for all viruses, as is the case of HIV-16. Even for SARS-CoV-2, it has taken years for COVID-19 vaccines to reach 20 % of the population in low-income nations7. Consequently, the availability of host-directed broad-spectrum antivirals ready to deploy when novel viruses break through will be key for future preparedness3.

Difficulties to develop pan-antivirals rely on the intensive labor required to screen libraries of compounds targeting the host. These drug-repurposing efforts were successful in revealing a plethora of already clinically available compounds with strong antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-28,9,10. However, identifying which of these candidates may have a broad-spectrum activity, and predicting a priori which viruses will be susceptible remains challenging. In this study, we followed an orthogonal approach instead, to understand the molecular changes induced after inhibiting a particular host factor and visualize novel indications beyond the well-known mechanism of action. Among the many processes that could be targeted in the host, protein translation is an attractive critical step central to viral replication. The tight regulation of cellular proteostasis11, which controls protein homeostasis and facilitates cell adaptation to a constantly changing environment, offers an opportunity to safely exploit translation as a therapeutic target.

Our starting point was our discovery that plitidepsin12,13, a marine compound that inhibits protein translation, also prevents SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro10 and in vivo14 and blocks the biogenesis of double-membrane vesicles (DMVs) where coronaviruses replicate15. The mechanism of action of plitidepsin is well established, as it targets the eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 alpha (eEF1A) that has two isoforms (eEF1A1 and 2) required for the binding of aa-tRNA to the A-site of ribosomes during the elongation step16. However, plitidepsin also triggers the phosphorylation of the eukaryotic initiation factor 2 subunit alpha (eIF2α) required to initiate translation17, highlighting its potential to alter diverse translation routes via yet unknown pathways.

Here we aimed to decipher how a pharmacological intervention reprograms the molecular landscape in a cell after blocking translation, what led to the identification of complementary antivirals targeting different protein translation routes. Using a combination of transcriptomics, deep quantitative proteomics and functional infectious or mRNA reporter assays, we show that plitidepsin viral inhibition goes beyond its primary mechanism of action and relies on the cell’s proteostatic response to eEF1A blockade, namely a shift from cap or internal ribosome entry sites (IRES)-mediated translation towards a N-6-methyladenosine (m6A)-dependent translation. We further exploit this mechanistic insight to predict and experimentally validate plitidepsin’s antiviral efficacy against other genetically diverse viral families based on the translation pathway they depend on. As predicted by the molecular network modified by plitidepsin, viruses that exploit m6A translation still replicate. However, these viruses were sensitive to other compounds targeting m6A readers involved in this particular route. Our study not only sheds light on the intricate relationship between viral replication and cellular proteostasis, but also serves as a template for the development of new host-targeting antivirals with a broad, predictable, and complementary range of activities. Unraveling the molecular fingerprint of cells treated with a host-directed translation inhibitor allowed us to predict viral sensitivity and to identify a rational approach to select for broad-spectrum antivirals that could be key to counteract future pandemic viruses.

Results

Plitidepsin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 omicron lineages

Plitidepsin interferes with protein translation via direct inhibition of the host elongation factor eEF1A, but also through the indirect phosphorylation of the initiation factor eIF2α required for protein synthesis16,17. Plitidepsin blockade of eEF1A has been previously demonstrated via knockdown and gain of function experiments in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection14. In agreement with this established mode of action, recent SARS-CoV-2 omicron variants XBB1.5 and BQ1.1 were similarly sensitive to plitidepsin as earlier variants such as D614G, and showed a dose response in the reduction of the viral-induced cytopathic effect on Vero E6 cells when drug and virus were added simultaneously to the cells (Fig. 1A). This was also the case for D614G and JN.1 variants in experiments where we reached a higher cytopathic effect (Supplementary Fig. 1A). The concentration of plitidepsin that inhibited 50 % of the viral-induced cytopathic effect (IC50) of all these variants was in the nanomolar range (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1A). This antiviral efficacy correlated with a significant reduction of SARS-CoV-2 RNA transcript production of positive and negative polarity measured over time in infected cells by transcriptome analysis (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 1B; P < 0.001 for all genes). This was also confirmed for some structural genes by qPCR (Fig. 1C; P = 0.0160 for envelope and P = 0.0437 for nucleocapsid). We next measured the amount of spike and nucleocapsid proteins released to the supernatant by ELISA and found a reduction in quantity by plitidepsin treatment (Fig. 1D; P = 0.0022 and P = 0.0260, respectively). When we titrated the infectivity of these supernatants, plitidepsin effectively reduced viral replication (Fig. 1E; P = 0.0022). We also used a SARS-CoV-2 nanoluciferase reporter virus to infect Vero E6 cells and test plitidepsin antiviral activity. With this reporter system, cells infected in the presence of 50 nM of plitidepsin did not produce nanoluciferase at non-cytotoxic drug concentrations (Fig. 1F; P < 0.0001). These findings demonstrate the drastic reduction of SARS-CoV-2 infection upon plitidepsin treatment, detected by independent techniques measuring viral-induced cytopathic effect, viral mRNA of distinct viral genes analyzed by transcriptomics or qPCR, release of viral proteins, viral titration and luciferase production by a reporter virus.

A Viral-induced cytopathic effect on Vero E6 cells exposed to different SARS-CoV-2 (D614G and two Omicron variants) in the presence of increasing concentrations of plitidepsin (red, orange and yellow lines). Cytotoxic effect on cells exposed to plitidepsin in the absence of virus is also shown (gray lines). Non-linear fit to a variable response curve showing mean and S.D. from one representative experiment (n exp = 1) with 3 technical replicates (n rep = 3) out of 3 experiments, excluding data from toxic drug concentrations. The IC50 for each virus is indicated. B RNAseq effective size libraries of total reads of positive (solid lines) and negative (dotted lines) cell-associated SARS-CoV-2 transcripts. Cells were infected with D614G and treated or not with 50 nM of plitidepsin and processed for transcriptome analysis at the indicated hours post-infection. Mean and S.D. of n rep = 3. Two-way RM ANOVA test showed P < 0.001 for all genes comparing mock versus plitidepsin. C Cell-associated copies of SARS-CoV-2 genes in cells infected with D614G treated or not with 50 nM of plitidepsin at the indicated hours post-infection detected by qPCR. Two-way RM ANOVA test showed P = 0.0160 for envelope and P = 0.0437 nucleocapsid genes comparing mock versus plitidepsin. D SARS-CoV-2 spike and nucleocapsid in the supernatant of Vero E6 cells infected with D614G over time ± 50 nM of plitidepsin detected by ELISA (P = 0.0022; P = 0.0260). C and D show mean and S.D. of n exp = 3 and n rep = 6. E Infectivity of supernatants collected 48 h post SARS-CoV-2-infection from cells treated ± 50 nM of plitidepsin in triplicates (P = 0.0022). Mean TCID50/mL and S.D. of n exp = 6 and n rep = 6, where the initial viral input to infect cells is marked by the gray shaded area. F Nanoluciferase produced by Vero E6 cells infected with a SARS-CoV-2 reporter virus and treated with the indicated concentrations of plitidepsin (P < 0.0001). Mean and S.D. of n exp = 3 and n rep = 9 expressed in relative light units (RLUs). Statistical differences from D to F were assayed with a two-sided Mann–Whitney U test 48 h post-infection. Source Data file provides source data.

Plitidepsin decreases the early translation of SARS-CoV-2 proteins required for the late synthesis of structural viral proteins

SARS-CoV-2 infection relies on the early translation of positive sense single-stranded viral RNA genomes liberated upon fusion. These genomes allow the synthesis of viral replicase polyproteins (pp1ab and pp1a) required for DMV formation, the organelles where, via double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) intermediates, the negative viral RNA strands and the sub-genomic RNAs are generated. These guide the later translation of structural proteins required for the formation of new viral particles. Since translation inhibitors have previously shown greater efficacy blocking negative sense coronavirus RNA synthesis than positive sense strand synthesis18, this led to hypothesize that plitidepsin could preferentially reduce sub-genomic RNA formation and accumulation14. Yet, we had previously observed that plitidepsin reduced formation of DMV15, suggesting that this compound could also block the earlier translation of positive sense SARS-CoV-2 RNAs needed for pp1ab and pp1a synthesis.

To test if plitidepsin could inhibit the initial translation of positive sense SARS-CoV-2 RNAs and limit the early synthesis of non-structural viral proteins, we performed a proteome analysis. Vero E6 cells left untreated (0 nM) or treated with increasing concentrations of the drug (0.5, 5, and 50 nM) were concomitantly inoculated with SARS-CoV-2 or left uninfected (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Fig. 2A). Two days post-inoculation, cells were processed for deep quantitative proteomics to gain resolution and cover most of the expressed cellular and viral proteins. We applied a multiplexed quantitative proteomics strategy with deep peptide fractionation using high pH reverse phase chromatography19 as a robust and highly reproducible technique. Tandem mass tags-based experiments have some advantages compared to label-free methods, including high multiplexing capacity, deep proteome coverage by off-line fractionation prior to mass spectrometric analysis, and increased number of statistically significant regulated peptides detected19. Using this strategy, we identified 8881 proteins across all tested conditions. The magnitude of protein detection and statistical significance in SARS-CoV-2 exposed cells versus non-infected cells treated at fixed concentrations of plitidepsin (ranging from 0 to 50 nM) were represented in a volcano plot, where cellular and viral proteins were identified (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Fig. 2A; Supplementary Data 1). In non-treated infected cells, 835 proteins were significantly upregulated and 705 were downregulated (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Data 1). Six out of eight detected SARS-CoV-2 proteins (spike, nucleocapsid, membrane protein, non-structural protein 8 -NS8-, ORF9B and pp1ab/pp1a proteins) showed robust quantification values and were used in subsequent analyses (Fig. 2A). These viral proteins were not significantly detected when SARS-CoV-2 inoculated cells were treated with 50 nM plitidepsin and compared to non-infected cells (Fig. 2A). Moreover, cells treated with 50 nM plitidepsin exposed to SARS-CoV-2 only up-regulated 50 proteins and down-regulated 79 among the 6533 proteins consistently detected throughout all samples (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Data 1). The antiviral effect of plitidepsin was lost at lower drug concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 2A), where protein changes resembled those found in untreated cells (Fig. 2A). Thus, we detected a much lower number of cellular proteins significantly altered in cells treated with 50 nM of plitidepsin exposed to SARS-CoV-2 when compared to non-infected cells (Fig. 2A), in contrast to the observed effect at lower drug concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Overall, these results emphasize that the proteins detected in 50 nM plitidepsin-treated cells exposed to SARS-CoV-2 highly resemble those identified in non-infected cells (Fig. 2A).

A Protein detection and significance obtained with a two-sided linear model adjusted with Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) in SARS-CoV-2 exposed versus non-infected cells ± 50 nM plitidepsin. Volcano plots of 6533 proteins consistently detected in all assayed samples comparing Log 10 of adjusted P-values and Log 2 fold change (FC). Dotted lines indicate P = 0.05. P Significantly downregulated cellular proteins are shown in yellow dots, upregulated in blue. Gray dots represent proteins with no variation. Viral proteins are shown in red. Proteins are listed in Supplementary Data 1. B Differences in abundance (Log 2 intensity distribution) of the indicated viral proteins in cells exposed to SARS-CoV-2 (orange) and not exposed (green) ± 0.5, 5 and 50 nM of plitidepsin. Interquartile range (IQR), and first, second and third quartiles (Q) are shown. Whiskers extend 1.5 times the IQR from Q1 and Q3. Data from A and B derive from n rep = 3 analyzed for each condition tested. C Percentage of Vero E6 cells positive for dsRNA detected by FACS. Cells ± 50 nM plitidepsin were inoculated with D614G for 48 h (P = 0.0002). Data show mean and S.D. from n exp = 3 and n rep = 8. D Confocal microscopy of dsRNA (green) of Vero E6 cells treated as in C. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). Scale bar 50 µm. E Cell-associated nucleocapsid and spike content detected by ELISA in Vero E6 cells infected with D614G ± 50 nM of plitidepsin followed over time (P = 0.0022). Mean and S.D. for each timepoint of n exp = 3 and n rep = 6. C and E statistical differences were assayed with a two-sided Mann–Whitney U test 48 h post-infection. F Confocal microscopy of nucleocapsid (green) and spike (red) staining of Vero E6 cells infected with D614G ± 50 nM of plitidepsin (Scale bar 50 µm). Highlighted inset is magnified (Scale bars 25 µm). Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). Source Data file provides source data.

When we focused on the viral proteins detected at each of the tested conditions, the antiviral effect was only evident at 50 nM of plitidepsin and equally effective at decreasing the expression of all the SARS-CoV-2 proteins detected herein (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. 2B), as previously observed for viral transcripts (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 1B). Thus, plitidepsin exerted its antiviral activity by reducing the expression of early pp1ab and pp1a polyproteins required for DMV formation and viral RNA genome replication, ultimately affecting the synthesis of structural proteins such as the nucleocapsid or the spike needed to generate new coronaviruses (Fig. 2B). To further confirm these proteomic results, we used independent analytical approaches. Pp1ab and pp1a polyproteins facilitate the synthesis of non-structural proteins involved in the replication of the viral genome via dsRNA. We used an antibody that binds dsRNA to detect coronavirus genome replication20 by FACS and confocal microscopy, and found that dsRNA was effectively reduced in cells exposed to SARS-CoV-2 and concomitantly treated with 50 nM plitidepsin two days post-infection (Fig. 2C; P = 0.0002, Supplementary Fig. 3A, and Fig. 2D). Next, we used different antibodies to detect the cell-associated SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and spike content in Vero E6 cells, which were reduced in the presence of 50 nM plitidepsin as observed by ELISA and confocal microscopy (Fig. 2E, F; P = 0.0022). The complementary approaches of proteomics, FACS, ELISA and confocal microscopy revealed that plitidepsin interfered with the early translation of SARS-CoV-2 positive sense RNA required for polyprotein synthesis, limiting viral RNA genome replication and subsequent structural viral protein formation needed for the correct biogenesis of new coronaviruses.

Plitidepsin reduces the translation of RNAs and de novo synthesis of host proteins without affecting cellular viability

The impact of plitidepsin on positive viral RNA translation prompted us to investigate if the observed inhibition was virus-specific or could extend to other unrelated transcripts. We therefore analyzed the expression of a processed, cap-dependent mRNA transcript encoding luciferase. A lipid nanoparticle (LNP) containing this luciferase 5’capped mRNA was used to transfect Vero E6 cells, and 48 h later, translation was effectively inhibited by 50 nM plitidepsin (Fig. 3A; P < 0.0001), similarly to that observed with the nanoluciferase SARS-CoV-2 reporter virus (Fig. 1F). To further confirm that the decrease of de novo protein expression was not virus-specific, we analyzed eGFP expression of cells transfected with either an mRNA encoding eGFP via LNPs or infected with an eGFP SARS-CoV-2 expressing virus. Regardless of the source of fluorescent protein used, we observed an equal inhibitory eGFP translation activity at 50 nM plitidepsin (Fig. 3B, C; P < 0.0001, Supplementary Figure 3B, C). Of note, we found a sustained activity of plitidepsin, as transfection of cells pre-treated for 48 h with 50 nM plitidepsin reduced de novo luciferase expression by 90 % (Fig. 3D; P < 0.0001), similar to the 96 % observed in cells transfected immediately after adding the drug. These data reinforce the capacity of plitidepsin to inhibit de novo cap-dependent translation of mRNAs from both viral and non-viral origin.

A Expression of luciferase in Vero E6 cells transfected with lipid nanoparticles (LNP) containing ready-to-express luciferase mRNA ± 50 nM plitidepsin. Vero E6 were assayed by luminometry two days after transfection. B Expression of eGFP in Vero E6 cells transfected with LNP containing ready-to-express eGFP mRNA in the absence or presence of 50 nM plitidepsin. Vero E6 were assayed by FACS two days after transfection. C Expression of eGFP in Vero E6 cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 eGFP reporter in the absence or presence of 50 nM plitidepsin. Vero E6 were assayed by FACS two days after infection. D Relative expression of luciferase in Vero E6 cells pre-treated or not with 50 nM plitidepsin for 48 h before transfection with LNP containing ready-to-express luciferase mRNA, assayed by luminometry one day after transfection. Values were normalized to the mean RLUs of cells transfected without the drug, set at 100 %. A–D show mean and S.D. of n exp = 3 and n rep = 9 (P < 0.0001). E Cellular ATP released by Vero E6 cells exposed for 48 h to the indicated plitidepsin concentrations measured by luminometry. Mean and S.D. of n exp = 4 and n rep = 12. F Cellular viability of Vero E6 cells exposed for 48 h to increasing concentrations of plitidepsin stained with live and dead staining kit by FACS. Cells were incubated with 10 % DMSO to induce mortality (P = 0.0022). G Cellular viability of Vero E6 treated as in F with 0.5, 5, and 50 nM plitidepsin and measured by MTT (P < 0.0001). F and G show mean and S.D. of n exp = 3 and n rep = 9. Statistical differences were assayed with a two-sided one sample t-test in D and with a two-sided Mann–Whitney U test in the rest of the panels. Source Data file provides source data.

Despite the observed inhibitory effect on de novo cap-dependent protein translation, plitidepsin treatment did not affect cellular viability, as detected by measuring the cellular metabolic state via luminometric ATP quantification (Fig. 3E), by assessing the cellular membrane integrity with a live and dead staining FACS probe effectively disrupted by DMSO (Fig. 3F; Supplementary Fig. 3D) or by MTT assay (Fig. 3G). Overall, these data showed an inhibitory activity of plitidepsin on de novo cap-dependent protein translation in a context where cellular viability was preserved.

Plitidepsin has a larger impact on SARS-CoV-2 mRNA abundance and viral protein translation than on host coding mRNAs or cellular protein synthesis

We then sought to analyze if the lack of cellular toxicity observed in the presence of plitidepsin could rely on the differential impact of this compound on the viral transcript and protein content as compared to the host mRNA and proteins synthesized two days after SARS-CoV-2 exposure. Translation efficiency of a given mRNA largely depends on its concentration if we assume a similar quantity of cellular resources available, such as the pools of free ribosomes, aa‐tRNAs and translation factors. Using transcriptomics to follow SARS-CoV-2 infected cells over time, we found that positive viral mRNAs increased and remained one logarithm above the host coding cellular mRNAs 24 h and 48 h after viral exposure (Fig. 4A; Supplementary Data 2). The decrease of host coding cellular mRNAs observed concurs with prior reports describing the early degradation of cytosolic cellular mRNAs upon SARS-CoV-2 infection21, but could be also linked to the viral induced cytopathic effect (Fig. 4A). In sharp contrast, 50 nM plitidepsin consistently maintained the level of positive viral mRNA one logarithm below host coding cellular transcripts, that were not altered over time by infection (Fig. 4B; Supplementary Data 2). Higher basal levels of host coding cellular mRNAs offered a plausible explanation for the preferential synthesis inhibition of de novo SARS-CoV-2 proteins over cellular proteins in the presence of plitidepsin.

A Host-coding RNA and positive cell-associated SARS-CoV-2 transcripts of Vero E6 cells exposed to SARS-CoV-2 at the indicated hours post-infection. B Cells were exposed to SARS-CoV-2 as in A with 50 nM plitidepsin. Transcripts are listed in Supplementary Data 2. C Log 2 fold change of cellular protein expression (yellow plots) and viral proteins (gray plots) comparing SARS-CoV-2 exposed cells treated with the indicated concentration of plitidepsin versus infected mock-treated cells. Violin plots show the median (horizontal lines) and quartiles (bottom and upper lines) 48 h post-infection. D Percentages of proteins increased (red), decreased (green) or unaffected (gray) in cells treated with 50 nM plitidepsin for 48 h found in SARS-CoV-2 exposed cells compared to non-infected untreated cells. E Molecular functions significantly enriched in proteins upregulated shown in D Protein counts within each of the molecular functions detected with a strength > 0.5 and more than 5 members are depicted. F Biological processes and cellular compartment categories significantly enriched in proteins as described in E. E and F show statistical differences and P values from two-sided enrichment test corrected with Benjamini–Hochberg FDR. G Circular plot of the connection network established between proteins mutually upregulated in cells treated with 50 nM plitidepsin in SARS-CoV-2 exposed and non-infected cells. eEF1A isoforms were also included (although they are not modified) to detect putative interactors (linked with orange lines). Purple lines show network connections. Gray-shaded areas contain purple lines whose length is proportional to the increased protein expression in SARS-CoV-2 exposed cells. External arches represent the molecular functions linked to these proteins, that have the same colors as in E Proteins not involved in the depicted functions or disconnected were not represented but are listed in Supplementary Data 3. Functions found are listed in Supplementary Data 4. Proteins in bold are functionally linked to the activity of plitidepsin. A–F show data of n rep = 3 analyzed for each timepoint tested. Source Data file provides source data.

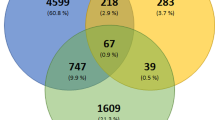

These findings correlated with the proteomic results obtained 48 h post viral addition. No major differences in the host protein expression were observed on cells treated with three concentrations of plitidepsin compared to untreated SARS-CoV-2 infected cells (Fig. 4C). In sharp contrast, for the viral proteome we observed a significant reduction of SARS-CoV-2 protein expression at 50 nM plitidepsin (Fig. 4C; Supplementary Data 1), as previously described in Fig. 2. A total of 840 cellular proteins, which represent fewer than 13 % of the total proteins detected (Fig. 4D), were significantly affected by 50 nM plitidepsin upon SARS-CoV-2 exposure, including some that were upregulated (5.5 %) or downregulated (7.3 %). Despite the capacity of plitidepsin to inhibit global de novo cap-dependent protein translation, this compound used at 50 nM had a very limited effect on the cellular proteome and a much higher impact decreasing the viral proteome.

Although the overall impact of plitidepsin on the host’s protein expression was limited, we wanted to understand whether those proteins whose expression changed could reveal more insights regarding the global effect on translation inhibition. To understand how treatment with an inhibitor of protein translation could lead to an increase in the expression of certain cellular proteins in treated cells, we analyzed the molecular landscape changed by 50 nM plitidepsin regardless of the infection status of the cell. The complete lists of proteins upregulated and downregulated in cells treated with 50 nM plitidepsin, that were consistently changed as compared to non-treated cells in the absence and in the presence of SARS-CoV-2, is detailed in Supplementary Data 3. No changes in the expression of eEF1A1 and eEF1A2, the two isoforms targeted by plitidepsin, were detected either by FACS analyses or proteomics (Supplementary Figs. 3E and 4). These findings are consistent with the predicted mode of action of plitidepsin, which likely binds eEF1A in the same site as didemnin B14 to block its activity during translation elongation, but does not lead to target degradation. Next, we focused on those proteins consistently downregulated by cells treated with 50 nM plitidepsin in the absence and in the presence of SARS-CoV-2 (Supplementary Data 3). These represented 3.22 % of all proteins, a lower percentage that the one linked to cells exposed to SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 4D). Functional enrichment analyses identified several associated with cell adhesion and regulation of motility (Supplementary Data 4, strength > 0.5). Using STRING, we only found 4 putative interactors of eEF1A: STAT-3, FN1, GRN and eE2FK, the latter being the only one involved in protein translation. eE2FK is a kinase that phosphorylates and inhibits the elongation factor eEF2, so its downregulation by cells treated with 50 nM plitidepsin may increase protein elongation rate via eEF2 activity. The network of proteins consistently upregulated by cells treated with 50 nM plitidepsin in the absence and in the presence of SARS-CoV-2 (Supplementary Data 3) represented a 3.18 % of all the proteins detected, which is a lower percentage that the one linked to cells exposed to SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 4D). The molecular functions enriched in this network were mostly related to translation, including RNA binding and structural constituent of ribosome (Fig. 4E; Supplementary Data 4, strength > 0.5). These gene ontology categories correlated with those found for biological processes, where most of the proteins were linked to cytoplasmic translation or rRNA processing, or for the cellular component, where most of the proteins grouped within cytosolic ribosome or ribonucleoprotein granule (Fig. 4F; Supplementary Data 4, strength > 0.5).

Within the upregulated proteins found in cells treated with 50 nM plitidepsin (Supplementary Data 3), we identified several putative interactors of eEF1A1 or 2 isoforms that were represented in a circular layout plot (Fig. 4G). The connection with these elongation factors was plotted inside the circle with inner orange lines, while the interaction among other members of the network is depicted in purple lines (Fig. 4G). The fold change in expression of each protein is represented by the length of the purple line within the gray bars (Fig. 4G), while their association to the molecular functions represented in Fig. 4E is shown in concentric color labels. Some interactors of eEF1A could inhibit protein translation, including AGO2 and PUM2. These two proteins complex with eEF1A and attenuate translation elongation22. We also found RC3H2, which promotes mRNA deadenylation and degradation, RRP8, that mediates silencing of ribosomal DNA, or CBX6, a component of a complex required to maintain a transcriptionally repressive state of many genes (Fig. 4G). We also identified EIF2AK3 (Fig. 4G), a stress-sensing kinase that phosphorylates eIF2α, which may explain why prior reports found an increased phosphorylation of eIF2α upon plitidepsin treatment17. Of note, phosphorylated eIF2α acts as a global cap-dependent synthesis inhibitor. Overall, these results show that plitidepsin increased the phosphorylation of eIF2α17 via EIF2AK3 upregulation and enhanced the expression of other translation-inhibiting proteins such as AGO2, PUM2, RC3H2 and CBX6.

STRING also identified several putative interactors of eEF1A crucial for enhancing protein synthesis, such as EIF2S3, 35 large and small ribosomal proteins (RPL and RPS), CTIF, eIF4G2, YTHDF1, PABPC1, and PABPC4 (Fig. 4G). EIF2S3 is a subunit of eIF2 involved in translation initiation that interacts with several of the ribosome proteins increased in response to plitidepsin treatment (Fig. 4G). This cluster of interconnected proteins stabilizes 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits and represents more than 36 % of all the ribosomal proteins annotated in the human proteome (35 out of 95). Another interactor found was CTIF (Fig. 4G), which complexes with eEF1A1 to facilitate the recognition and aggresomal targeting of misfolded proteins23 and functions as a cap-dependent translation initiation factor. The upregulation of these cap-dependent translation factors may represent a cellular homeostatic response after treatment with a translation inhibitor such as plitidepsin. Yet, cells treated with plitidepsin also upregulated several proteins involved in cap-independent translation pathways, such as eIF4G2, PABPC1, IGF2BP2 and YTHDF1 (Fig. 4G). These factors pointed to a possible route to preserve the host proteome, but whether cap-independent translation pathways continued to be active in the presence of plitidepsin remained unknown.

Plitidepsin redirects viral translation via eIF4G2 and PABPC1 towards a cap-independent m6A route read by IGF2BP2

Our study found a previously unnoticed global effect of plitidepsin, namely treatment-induced changes in the host’s protein translation machinery, which could favor antiviral activity while preserving the cellular proteome integrity. However, the mechanism underlying the preferential increase of certain proteins in the presence of plitidepsin was unclear. Among the proteins upregulated by cells treated with 50 nM plitidepsin, we identified eIF4G2, which is required to initiate cap‐independent mRNA translation when eIF2α is phosphorylated24, as it happens upon plitidepsin treatment17. Several cap-independent pathways regulated by eIF4G2 co-exist with cap-dependent translation25. These alternative routes allow to initiate translation via m6A reading, CITES or IRES elements25.We, therefore, checked if eIF4G2-dependent IRES-mediated translation could operate in the presence of plitidepsin. We tested a dual-reporter plasmid that expresses firefly luciferase via a poliovirus cap-independent IRES translation and renilla luciferase via a cap-dependent translation route. With this system, we observed that plitidepsin equally inhibited cap-dependent and cap-independent IRES pathways (Fig. 5A). We next confirmed that IRES-dependent translation is also targeted by plitidepsin using a plasmid of HIV-1-Gag-eGFP that is enriched in IRES domains26, that was also effectively blocked by plitidepsin (Fig. 5B; P = 0.0002, Supplementary Fig. 3F). These results suggest that after IRES-mediated initiation of protein translation, the target of plitidepsin eEF1A is required to continue with protein elongation, providing a possible explanation for the inhibitory activity of this compound.

A Expression of a bi-cistronic dual reporter plasmid that expresses firefly luciferase via a poliovirus IRES and renilla luciferase via cap-dependent translation 48 h after Vero E6 transfection ± 50 nM of plitidepsin. B Geometric mean expression (Geo Mean) of HIV-1 Gag-eGFP plasmid detected by FACS 48 h after transfection on Vero E6 cells ± 50 nM of plitidepsin (P = 0.0002). C Infection of a luciferase single-cycle infectious HIV-1 construct pseudotyped with VSVg in the presence of the indicated antivirals (P = 0.0315; P ≤ 0.0012). Vero E6 cells were pulsed with equal amount of pseudoviruses and cultured for two days to determine luciferase activity, in RLUs. D Infection of a GFP single-cycle infectious HIV-1 construct pseudotyped with VSVg in the presence of indicated antivirals for two days. Vero E6 cells were pulsed with an equal amount of pseudoviruses to determine Geo Mean GFP in HIV-1 GFP+ cells by FACS (P < 0.0001). E Representation of Biorender showing proteins upregulated by 50 nM plitidepsin involved in translation via m6A and readers identified. Graph shows infection of HIV-1 construct pseudotyped with VSVg as in C, but in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of CWI1-2 (P = 0.0384; P = 0.0001), tegaserod and plitidepsin (P = 0.0057). F Nanoluciferase produced by Vero E6 cells infected with a nanoluciferase SARS-CoV-2 reporter virus. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of CWI1-2, tegaserod and plitidepsin (P < 0.0001) and assayed by luminometry 48 h post-infection. Values are expressed in RLUs. G Fold reduction of luciferase mRNA expression on Vero E6 cells 48 h in the presence of 50 nM plitidepsin after transfection of a capped 5’ mRNA, an uncapped with 50 % of m6A (P < 0.0001) or an uncapped mRNA not modified (P = 0.0002). A–G show mean and S.D. from at least n exp = 3 and n rep = 8, where statistical differences were measured with a two-sided Man–Whitney U test. HIV-1 human immunodeficiency virus type 1, VSVg vesicular stomatitis virus G protein, DTG Dolutegravir, AZT Zidovudine. Source Data file provides source data.

After confirming that plitidepsin effectively blocked cap-independent and IRES-mediated translation, we focused on several of the interactors of eEF1A upregulated on cells treated with plitidepsin, including eIF4G2 and PABPC1 (Fig. 4G) that are involved in m6A-mediated mRNA cap-independent translation27. The m6A in the 5´ UTR of mRNA recruits readers such as IGF2BP2 and YTHDF1 that are upregulated in response to plitidepsin treatment (Fig. 4G), which then bind to eIF4G2 and PABPC1 to initiate m6A mRNA translation, even when eIF2α is phosphorylated and eEF1A is not present28. To test if cells treated with 50 nM plitidepsin could effectively inhibit m6A‐mediated cap‐independent translation, we infected Vero E6 cells with an HIV-1 VSVg-pseudotyped luciferase reporter virus that uses this translation route29. When the genome of this reporter virus is retrotranscribed into DNA, it integrates into the cellular genome and produces luciferase transcripts fused to Nef along all HIV-1 genes except for Env and Vpr. In the presence of plitidepsin, cells infected with this HIV-1 reporter system did not decrease luciferase production as compared to untreated infected cells (Fig. 5C), suggesting the activity of a cap-independent alternative translation route. Of note, our prior findings with the HIV-1 Gag-eGFP expression plasmid inhibited by plitidepsin (Fig. 5B) did not challenge these results, as Gag was expressed by transient transfection in the absence of viral infection. This viral protein was selected because HIV-1 Gag mRNA transcripts are largely devoid of m6A modifications29,30 due to a specific demethylation of Gag that promotes genomic viral RNA packing31. We also used a different GFP VSVg-pseudotyped HIV-1 system that integrates into the cellular genome and expresses GFP alone and no other HIV-1 transcript32,33, which are the ones read via m6A‐meadiated translation29. With this system, infected plitidepsin-treated cells produced less GFP, as similarly observed with dolutegravir (DTG), an antiviral that inhibits HIV-1 integration (Fig. 5D; P < 0.0001, Supplementary Fig. 3G).

Next, we aimed to confirm that HIV-1 mRNA can be expressed via m6A translation. We targeted IGF2BP2 and YTHDF1, two of the readers upregulated in cells treated with plitidepsin (Fig. 4G). We blocked IGF2BP2 using CWI1-2 and YTHDF1 with tegaserod34,35, and found that HIV-1 luciferase expression was reduced by treatment with IGF2BP2 inhibitor but not by YTHDF1 inhibitor, suggesting IGF2BP2 is a key reader of modified HIV-1 transcripts (Fig. 5E; P = 0.0001). In sharp contrast, CWI1-2 and tegaserod did not affect SARS-CoV-2 replication, while plitidepsin clearly blocked it (Fig. 5F; P < 0.0001). To test the effect of plitidepsin in cap-dependent translation compared to m6A-mediated translation in a non-viral context, we transfected three mRNAs coding for the same luciferase gene with a 5’ capped end with 0 % of m6A, an uncapped 5’ end methylated with 50 % of m6A, and an uncapped 5’ end which cannot be translated (Fig. 5G). The fold reduction of luciferase production by plitidepsin was significantly greater for capped mRNAs but had a lower effect on uncapped mRNA with 50 % m6A (Fig. 5G; P < 0.0001). Hence, this inhibitor had a lower impact on m6A translation.

Overall, these data indicate that in response to plitidepsin, cells upregulated key molecules involved in ribosome biosynthesis and m6A‐mediated translation, which can preserve the host proteome in the presence of an inhibitor of cap and IRES-mediated translation. Thus, beyond eEF1A inhibition and eIF2α phosphorylation, plitidepsin treatment on cells reprogramed a critical molecular network that regulates de novo protein translation and still allows for m6A‐ protein synthesis. That is the case of HIV-1, which can be targeted via specific alternative inhibitors of m6A readers such as CWI1-2, but not SARS-CoV-2, which is only sensitive to plitidepsin. This novel molecular landscape shaped by plitidepsin predicts its broad-spectrum antiviral potential against viruses that translate via cap-dependent and IRES-mediated pathways, which do not include m6A modifications because they are negatively regulated by m6A.

Antiviral activity of plitidepsin against other viruses

The molecular landscape reprogrammed by cells treated with plitidepsin had the potential to inhibit other RNA or DNA-dependent viruses that rely on cap-dependent and IRES-mediated translation. Yet, it also anticipated a lower activity against viruses that translate via m6A-mediated pathways. We, therefore, tested if plitidepsin was effective against other coronaviruses beyond the different SARS-CoV-2 variants we had tested before. We used MERS-CoV and, as expected, we also found an inhibitory activity of plitidepsin in the nanomolar range (Fig. 6A) as observed for remdesivir in the micromolar range (Supplementary Fig. 5). Since the methylation via m6A inhibits the replication of several RNA flaviviruses36,37,38, we next tested if plitidepsin was effective against these viruses as well. When we assessed if plitidepsin could inhibit the replicon system for Hepatitis C virus (HCV) or the replication of Zika virus (ZIKV), we found that this was the case for both flaviviruses (Fig. 6B, C) as detected with other well-known antivirals (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results confirmed the in vitro capacity of plitidepsin to inhibit the replication of two members of a distant viral family as compared to coronaviruses. Next, we tested the antiviral potential of plitidepsin against DNA viruses such as Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) during the lytic phase. Upon HSV-1 infection, m6A machinery redistributes accompanied by a wide-scale reduction of m6A both in the host and viral mRNAs39. Accordingly, we found that HSV-1 was also sensitive at a similar nanomolar range (Fig. 6D), further confirming the broad-spectrum antiviral activity of plitidepsin. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is an RNA virus that enhances viral replication via m6A-dependent translation, but has above 3-fold lower percentage of m6A than retroviral transcripts40,41. We therefore checked the antiviral activity of plitidepsin against RSV and observed that reaching a full inhibition required about a 10-fold higher drug concentration in this case (Fig. 6E; Supplementary Fig. 3H). Finally, we tested HIV-1, a retrovirus that effectively replicates via m6A translation29. Plitidepsin failed to inhibit HIV-1 replication (Fig. 6F), in agreement with prior data with the HIV-1 luciferase reporter pseudovirus (Fig. 5C) and in contrast to the well-known antiretroviral efavirenz (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results indicate that while plitidepsin has a lower antiviral potency against viruses that use m6A-synthesis pathways such as HIV-1, the molecular reprogramming of cells treated with plitidepsin broadly inhibited the replication of different unrelated viruses suppressed by m6A methylation that rely on cap-dependent or IRES-mediated translation routes.

A Dose-response curve for the anti-MERS-CoV activity (red lines) and cytotoxicity of plitidepsin (gray lines) shown as the mean and S.D. of n exp = 3 and n rep = 9 measured 3 days post-infection. B Dose-response curve for the anti-HCV replicon activity (red lines) and cytotoxicity of plitidepsin (gray lines) shown as the mean and S.D. of n exp = 3 measured 2 days post-infection. C Dose-response curve for the anti-ZIKV activity (red lines) and cytotoxicity of plitidepsin (gray lines) shown as the mean and S.D. of n exp = 3 measured 5 days post-infection. D Dose-response curve for the anti-HSV activity (red lines) and cytotoxicity of plitidepsin (gray lines) shown as the mean and S.D. of n exp = 3 measured 2 days post-infection. E Dose-response curve for the anti-RSV activity (red lines) and cytotoxicity of plitidepsin (gray lines) shown as mean and S.D. of n exp = 3 and n rep = 9 measured 3 days post-infection. F Dose-response curve for the anti-HIV-1 activity (red lines) and cytotoxicity of plitidepsin (gray lines) shown as the mean and S.D. of n exp = 3 measured 5 days post-infection. A–F The IC50 value is also indicated. MERS-CoV Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, HCV hepatitis C virus, ZIKV Zika virus, HSV herpes simplex virus, RSV respiratory syncytial virus, HIV-1 human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Source Data file provides source data.

Discussion

Our study sheds light into the translational landscape shaped by cells treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor plitidepsin, which acts beyond its well-established mechanism of action. This analysis revealed its broad antiviral potential against viruses repressed by m6A that translate via cap- or IRES-mediated routes. The effect of m6A on SARS-CoV-2 replication has yielded conflicting results42,43. However, a recent report suggests that while m6A facilitates SARS-CoV-2 RNA transcription, it also represses translation43. This could regulate the early switch from RNA translation to replication in the viral life cycle43. Given that SARS-CoV-2 particles are largely devoid of m6A modifications, which are later acquired by viral RNA throughout the replication cycle43, incoming SARS-CoV-2 viruses mostly rely on cap-dependent translation routes and are highly susceptible to plitidepsin and resistant to reader inhibitors. Other plitidepsin-sensitive RNA viruses tested herein also require early protein translation for establishing a productive infection and may be largely devoid of m6A modifications44. That is the case of HCV, which is translated via an IRES-dependent pathway45 sensitive to plitidepsin, or a DNA virus like HSV-1, whose infection reduces m6A methylation both in host and viral mRNAs39. In contrast, an RNA virus such as RSV enhances replication via m6A-dependent translation40, which may explain the higher IC50 of plitidepsin required to inhibit infection of this virus.

We also identified resistant viruses such as HIV-1, which does not rely on early viral protein translation to integrate as a provirus in the cellular genome. Here we found that HIV-1 translates in the presence of plitidepsin via a m6A-mediated pathway that is effectively targeted via other inhibitors of m6A readers, such as CWI1-2. Most importantly, our results identified IGF2BP2 as a new reader that regulates the expression of HIV-1. Overall, our findings highlight the utility of plitidepsin to counteract distant unrelated viruses from the Coronaviridae, Flaviviridae, Pneumoviridae and Herpesviridae families. Moreover, this strategy can be complemented with other drugs targeting m6A readers to globally repress the translation of different viruses exploiting m6A translation routes, as it is the case of retroviruses such as HIV-1. Targeting translation may therefore represent a unique therapeutic opportunity to identify complementary broad-spectrum antivirals with potential to widely tackle future pandemic viruses.

Plitidepsin binds to eEF1A and inhibits the elongation step where it promotes the attachment of the ternary complex (aminoacyl-tRNA-eIF2-GTP) to the A-site of the 80S ribosome. In addition, in response to plitidepsin treatment, cells induced the phosphorylation of eIF2α17 via the upregulation of EIF2S3K detected herein, which results in the arrest of protein synthesis at the initiation step46. These observations correlate with the capacity of plitidepsin to inhibit de novo cap-dependent translation of mRNAs regardless of their viral or cellular origin. However, plitidepsin did not affect cellular viability and had a larger impact on SARS-CoV-2 mRNA abundance and viral protein translation than on host coding mRNAs or cellular protein synthesis. The upregulation of key molecules associated with protein translation and ribosome synthesis in cells treated with plitidepsin could represent a homeostatic response after translation inhibition. Plitidepsin treatment also upregulated several proteins involved in cap-independent translation, such as eIF4G2, PABPC1 and m6A readers like IGF2BP2 and YTHDF1. These factors pointed to a possible cap-independent translation route that could preserve the host proteome in the presence of plitidepsin, favouring proteostasis. Prior studies have shown translation-competent complexes containing m6A mRNAs that joined ribosomal subunits and initiated elongation in the absence of eEF1A27 inhibited by plitidepsin. Factors such as eIF5 or eEF2, whose inactivating kinase eE2FK is downregulated in cells treated with plitidepsin, resulted in the formation of 80S ribosomes that underwent efficient elongation in the absence of eEF1A27, helping to explain why m6A transcripts are translated in the presence of plitidepsin. Thus, and beyond eEF1A inhibition and eIF2α phosphorylation, cells treated with plitidepsin reprogramed a critical molecular network that regulates de novo cap- and IRES-mediated protein translation, allowing viral m6A‐mediated protein synthesis.

Plitidepsin is a promising example of a safe host-directed COVID-19 therapy12,13,47,48. The therapeutic potential of targeting m6A regulators is gaining momentum49, and by using CWI1-2 as an inhibitor in our assays, we identified IGF2BP2 as an efficient reader modulating HIV-1 expression. In turn, this class of host-directed antivirals targeting translation routes could prove valuable in developing novel and complementary broad-spectrum therapies. In this study, we demonstrate how plitidepsin interferes with viral replication by altering translation routes through a molecular pathway that acts beyond the inhibition of eEF1A. Our findings highlight the relevance of revealing the molecular signature reprogrammed in cells by host-directed therapies to unleash their full clinical potential and suggest that targeting alternative translational routes could offer protection against distant and unrelated major viral human threats.

In forthcoming outbreaks, a first line of broad-spectrum antivirals such as plitidepsin could be quickly implemented in the clinical settings and offer protection against novel viruses using cap or IRES-mediated translation. In addition, therapies targeting m6A readers could be useful against plitidepsin resistant viruses and provide alternative treatment options. Preparedness strategies will only succeed if we gain a deeper understanding of how host-directed antivirals work and how we can safely use them. Unraveling the molecular landscape reprogrammed by cells treated with host-directed therapies beyond their well-known mechanism of action could be key to identify complementary broad-spectrum antivirals such as plitidepsin or m6A inhibitors ready to deploy when a new pandemic begins.

Methods

Ethics statement

The institutional review board on biomedical research from Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol (HUGTiP) approved this study. The biologic biosafety committee of the Research Institute Germans Trias i Pujol approved the execution of SARS-CoV-2 experiments at the BSL3 laboratory of the Centre for Comparative Medicine and Bioimage (CMCiB) with reference approvals CSB-20-015-M7. The biologic biosafety committee of IRTA CReSA approved the execution of MERS-CoV experiments at the BSL3 laboratory with reference approval CBS159-2024. The biologic biosafety committee of IrsiCaixa approved the execution of ZIKV, HSV, HCV replicon and HIV-1 experiments at the BSL3 laboratory of IrsiCaixa.

Cell cultures and viral stocks

Vero E6 cells (ATCC CRL-1586) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 5 % fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (all ThermoFisher Scientific). MT4 cells (NIH AIDS Reagent Program) were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI; Life Technologies, Thermofisher) supplemented with 10 % FBS (Gibco, Thermofisher), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. HEK-293T cells (ATCC repository) were maintained in DMEM with 10 % fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (all from Invitrogen).

SARS-CoV-2 stocks used included original D614G isolated in March 2020 from a nasopharyngeal swab10. Compared to the Wuhan/Hu-1/2019 strain, this isolate has the following point mutations: D614G (spike), R682L (spike), and C16X (nsp13). Omicron variants tested included XBB.1.5, BQ1.1, and JN.1. Genomic sequences were deposited at GISAID repository (http://gisaid.org) with accessions ID EPI_ISL_510689 for D614G; EPI_ISL_17308812 for XBB.1.5, and EPI_ISL_16375366 for BQ.1.1, and EPI_ISL_18838623 for JN.1. Genomic sequencing was performed from viral supernatant by using standard ARTIC v3 based protocol followed by Illumina sequencing (dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bhjgj4jw). Raw data analysis was performed by viralrecon pipeline (https://github.com/nf-core/viralrecon) while consensus sequence was called using samtools/ivar at the 75 % frequency threshold. Viruses were propagated for three passages and viral stocks were prepared collecting and centrifuging the supernatant from Vero E6 cells. Recombinant infectious clone with nano-luciferase gene icSARS-CoV-2-nLuc (kindly contributed by Dr. Ralph S. Baric) was obtained from BEI resources, NIAID, NIH (# NR-54003). Recombinant infectious clone with eGFP gene iSARS-CoV-2-eGFP (kindly contributed by Dr. Ralph S. Baric) was obtained from BEI resources NIAID, NIH (# NR-54002). Viral stocks were titrated in Vero E6 cells, and the median tissue culture infectious dose per mL (TCID50/mL) were calculated using the Reed & Muench method.

MERS-CoV EMC B/2012 (GenBank Accession JX869059) was propagated as in ref. 50. Zika virus (ZIKV) strain MP1751 (ref: 1308258v), a positive sense RNA Flavivirus, was obtained from the National Collection of Pathogenic Viruses (UK Health Security Agency, UKHSA). ZIKV MP1751 corresponds to the African lineage (Uganda). Genomic sequence was deposited at GenBank repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/KY288905.1) with accession ID KY288905.1. Viral stocks were produced according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, ZIKV MP1751 was propagated in Vero E6 cells cultured in MEM with 10 % FBS (Gibco, Thermofisher) and cytopathic effect (CPE) was observed 3–4 days post-infection. Then, cell culture supernatants were isolated, filtered, and stored in aliquots at −80 °C until their use. Respiratory Syncytial Virus with enhanced GFP (RSV-GFP5) strain A2 stock was purchased from ViraTree LLC company (North Carolina, U.S.A). RSV stocks were grown in Vero E6 cells cultured in DMEM with 10 % FBS and collected when CPE was observed and verified by the presence of GFP+ cells. Then, cells were scraped and lysed to obtain the intracellular virus, pooled with the culture supernatant, and stored in aliquots at −80 °C. HSV-1 used is a laboratory-adapted 17syn+ strain containing a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-GFP cassette in the US5 region, and was grown in Vero E6 cells and stored at −80 °C51. The HIV-1 viral strain NL4-3 was obtained from the MRC Centre for AIDS Reagents (London, United Kingdom). NL4-3 viral stocks were produced on lymphoid MT4 cells and after 5 days of infection, cell culture supernatant was collected, filtered, and stored at −80 °C. Viral stock was titrated for use in MT4 cells prior to their use in the antiviral screening.

Antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants

Increasing concentrations of plitidepsin (PharmaMar) were added to 6 ×104 Vero E6 cells per well seeded in 96-well plates and immediately after, were infected with equivalent infectious units of the indicated SARS-CoV-2 variants titrated to induce a 50 % or above 70 % of CPE. Untreated non-infected cells and untreated virus-infected cells were used as negative and positive controls of infection, respectively. To detect any drug-associated cytotoxic effect, Vero E6 cells were equally cultured in the presence of increasing drug concentrations, but in the absence of virus. Cytopathic or cytotoxic effects of the virus or drugs were measured 3 days post-infection, using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega). Luminescence was measured in a Fluoroskan Ascent FL luminometer (ThermoFisher Scientific).

For kinetic experiments, 6 ×104 Vero E6 cells per well seeded in 96-well plates were infected with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.02 with the D614G variant in the presence or absence of 50 nM of plitidepsin. Cells were washed and collected at the indicated timepoints and assayed by qPCR to detect the envelope and nucleocapsid of SARS-CoV-2. Gene expression was determined by RT-qPCR (7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System; Applied Biosystems #4377355). Total RNA was isolated (NucleoSpin RNA Mini Kit; Macherey-Nagel #740955.50) from cells collected at different time points, retro-transcribed (RT) by AgPath-ID One Step RT-PCR kit (Applied Biosystems #AM1005), amplified by a TaqMan real-time PCR (50 °C for 10’, 95° for 10’, and 45 cycles at 95 °C for 15” and 58 °C for 30”) to obtain the number of cycles (Ct). The total gene copy number was normalized and extrapolated from the number of cycles (Ct) using a standard curve. Collected supernatant was used to measure the amount of spike or nucleocapsid with SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein ELISA Kit For Vaccine Development (ACROBiosystems; #RAS-A039) and Human SARS-CoV-2 N ELISA Kit (ThermoFisher; #EH490RB) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. These supernatants were titrated in triplicates on Vero E6 cells through 10 serial dilutions. After 5 days post-infection, cells were inspected by microscopy for a viral-induced CPE to calculate TCID50/mL with the Reed Muench method.

Assays with icSARSCoV-2-nLuc were performed in 6 ×104 Vero E6 cells per well seeded in white- 96-well plates and infected with nanoLuc SARS-CoV-2 reporter virus at a MOI of 0.02. Cells were treated with 0; 0.5; 5 and 50 nM of plitidepsin. Two days post-infection, nanoluciferase expression on infected cells was assessed with Nano-Glo Luciferase Assay (Promega; #N1110) measured with a Fluoroskan FL Plate Reader (Thermo Fisher). To evaluate any drug-associated cytotoxic effect, Vero E6 cells were equally treated and analyzed 48 h after transfection using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent viability assay (Promega; #G7570).

Cellular infection for protein extraction and precipitation

1 ×106 Vero E6 cells per well were seeded in a 24-well plate and infected with D614G SARS-CoV-2 at a MOI of 0.02 for 48 h in the presence or absence of 0.5, 5, and 50 nM of plitidepsin added at the time of infection. As a negative control, Vero E6 cells were treated with or without plitidepsin for the same time but without virus. After 48 h post-infection, cells were washed and lysed in 2 % SDS 50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.6 lysis buffer. Lysates were inactivated at 95 °C for 10 min and stored at −80 °C until the proteomic analysis was performed. Lysates were incubated on ice for 15–30 min followed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove insoluble debris. Protein was precipitated with 50 µL 100 % w/v TCA overnight (ON) at 4 °C. Then the pellet was washed with 500 µL of chilled acetone 30 min with vortex every 10 min two times. The sample was centrifuged and resuspended with 300 µL 6 M Urea Tris 0,1 M and quantified DCTM Protein Assay (BIO-RAD) kit.

In-solution digestion for proteomic analysis

Briefly, 100 μg of each sample in a solution of 0.1 M Tris pH8/6 M Urea were digested with Lys-C and Trypsin. Prior digestion, samples were reduced and alkylated with DTT and CAA, then the samples were diluted with Tris 0.1 M to reach urea 2 mol/L. Lys-C was added at 1:100 (w/w) (enzyme-to-protein ratio) and protein digestion was carried out at 30 °C ON. Then the samples were diluted again with Tris 0.1 M to reach urea 0.8 mol/L. Trypsin was added at 1:100 (w/w) (enzyme-to-protein ratio) and protein digestion was carried out at 30 °C for 8 h. Enzymatic reaction was stopped with FA (10 % (v/v) final concentration). Digested sample was cleared by centrifugation and purified using reversed-phase C18 column (C18 macrospin column, The Nest Group) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Elution of peptides was performed with 50 % ACN in 0.1 % TFA, peptides were dried at the speedvac at RT and saved at −80 °C until further processing.

Tandem mass tag (TMT)-based MS proteomics labeling

Peptides were reconstituted in 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.5) and TMT16-plex reagents (ThermoFisher) was added from stocks dissolved in 100 % anhydrous ACN at a protein: MT ratio of 1:1.5 (w/w). The peptide–TMT mixture was incubated for 1 h at 25 °C and 400 rpm, and the labeling reaction was stopped by addition of either 5 % hydroxylamine to a final concentration of 0.4 % (15 min at 25 °C and 400 rpm). Labeled peptides were desalted using RP solid-phase extraction cartridges (Waters) and fractionated with Zorbax Extent-C18 (2.1 ×150 mm 3.5 µm 300 A) into 96 fractions and pooled into 48 fractions. The 48 fractions were dried via speedvac and the even fractions were desalted in stage tip columns.

LC-MS/MS measurements

Tryptic peptides sample were reconstituted with 3 % ACN and 0.1 % FA aqueous solution at 100 ng/µL and 8 µL (800 ng) were loaded into the Evotip. Peptides were separated using an Evosep EV1106 column (150 μm × 150 mm, 1.9 μm) (Evosep) at a flow rate of 500 nL/min with an 88 min run. The column outlet was directly connected to an EASY-Spray source (Thermo) fitted on an Orbitrap Eclipse™ Tribrid (Thermo Scientific). The mass spectrometer was operated in a data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. In each data collection cycle, one full MS scan (375–1500 m/z) was acquired in the Orbitrap (1.2 ×105 resolution setting and automatic gain control (AGC) of 2 ×105). The following MS2-MS3 analysis was conducted with a top speed approach. The most abundant ions were selected for fragmentation by collision-induced dissociation (CID). CID was performed with a collision energy of 35 %, 0.25 activation Q, an AGC target of 1 ×104, an isolation window of 0.7 Da, a maximum ion accumulation time of 50 ms and turbo ion scan rate. Previously analyzed precursor ions were dynamically excluded for 30 s. For the MS3 analyses for TMT quantification, multiple fragment ions from the previous MS2 scan (SPS ions) were co-selected and fragmented by HCD using a 65 % collision energy and a precursor isolation window of 2 Da. Reporter ions were detected using the Orbitrap with a resolution of 30,000, an AGC of 1 ×105 and a maximum ion accumulation time of 120 ms.

Data analysis and statistics for proteomic analyses

The RAW thermo files were processed with PEAKS X+ software using two databases (https://www.uniprot.org/). The first database is a mixture of sequences from the primate’s order (downloaded in May 2020) and the second contains the sequences of the SARS-CoV-2 proteins (downloaded in July 2021). Both databases were fused to obtain the final database which was interrogated to identify the proteins. The search was performed using the following parameters: Trypsin was selected as enzyme and a maximum of three missed cleavages were allowed. Carbamidomethylation in cysteines was set as a fixed modification, whereas oxidation in methionines, acetylation at the protein N-terminal and deamidation at asparagine and glutamine were used as variable modifications. The mass tolerance for the parental ion and MS/MS fragments were set to 10 ppm and 0.5 Da. Additionally, the TMT16plex modification (+304.21 Da) was set as fixed modification to allow the software to quantify the peptides. The FDR was assessed by using a decoy database and the final list of peptides and proteins was filtered at an FDR < 1 %. The manipulation of the data as well as the statistical analysis was performed using the R and R studio (https://www.rstudio.com/) software.

The resulting data matrix containing a total of 8881 proteins was filtered to remove common contaminants. Then, the quantification values were log2-transformed, and the proteins were grouped in protein groups according to the profile of peptides assigned to each protein. The resulting data set was then adjusted to remove the TMTset-batch effect by means of the ComBat algorithm (‘sva’ R package) and finally, all the samples were median-centered. The complete workflow generated a list of 7579 protein groups. Among them, a total of 6533 proteins which showed quantification values in all the samples, were used in the subsequent analyses. The statistical analyses were performed using the R package ‘limma’ and the functional analyses (enrichment analyses) were addressed with the R package ‘clusterProfiler’. The proteins with a Benjamini–Hochberg p adjusted P value < 0.05 were considered significantly regulated.

Gene ontology analyses and circular layout plot

To generate the list of all the Gene Ontology (GO) terms associated to proteins consistently upregulated or downregulated by 50 nM plitidepsin with or without SARS-CoV-2, we used STRING to select for Molecular Function, Biological Process, and Cellular Component as detailed below for the circular layout plot.

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks were constructed using STRING database52.The proteins submitted to STRING were those upregulated in cells treated with 50 nM plitidepsin in the presence or absence of SARS-CoV-2, using the fold change in protein expression of samples exposed to the virus. eEF1A isoforms were included in the analysis because they are plitidepsin targets, but their expression remained constant after treatment. First, all proteins that were detected in a non-human database were assigned to their human ID using the OMA database53. After obtaining the human orthologs ID, non-human and human sequences were aligned using ExPASy54, and sequence homology was between 94.3 % and 99 % in all cases. Interactions were determined by using the “full STRING network” as network type and nodes with an interaction score lower than 0.5 were removed. Also, “Neighborhood”, “Gene Fusion” and “Co-occurrence” were disabled as interaction sources and proteins with no interactions were removed from the PPI Network. The functional annotation used in the network was Gene Ontology55 and we used Biological Process, Molecular Function and Cellular Component. Enrichment results were filtered by adjusted P value < 0.05, Strength > 0.5. Functional terms with less than 5 proteins were also removed. In the case of Biological Process and Cellular Component, we nested those pathways significantly enriched (P value < 0.05) using the proteins of other categories with a lower adjusted P value to remove the redundancy of the results. The code developed to do this operation can be found in the following repository: https://github.com/proteomicsIJC/Functional_Annotation_Collapse. The PPI Network was represented using a circular layout plot made with the R package “circlize”56.

Viral detection by FACS, ELISA and confocal microscopy

Detection of dsRNA was performed on 4 ×105 Vero E6 cells per well seeded in a 24-well plate infected or not with a MOI of 0.02 with the D614G variant in the presence or absence of 50 nM of plitidepsin two days post-infection. Cells were fixed and permeabilized with a Fix&Perm kit (Thermo, #GAS001S100 and #GAS002S100) and stained with SCICONS mouse dsRNA Ab clone J2 from Nordic-MuBio (Abyntek; #10010500) revealed with a secondary mAb Goat anti-Mouse IgG2a Cross-Adsorbed Alexa Fluor™ 488 (Thermo, #A-21131). Samples were analyzed with Canto Flow Cytometer (BD) using FlowJo software to evaluate collected data.

For kinetic experiments, 6 ×104 Vero E6 cells per well seeded in a 96-well plate were infected with a MOI of 0.02 with the D614G variant in the presence or absence of 50 nM of plitidepsin. Cells were washed and lysed at the indicated timepoints to detect the cell-associated amounts of spike and nucleocapsid viral proteins with the previously indicated ELISAs. For immunofluorescence studies, Vero E6 cells were grown on 8-well Ibidi plates and infected in the presence or absence of 50 nM plitidepsin. At 48 h post-infection, cells were fixed with Fix media from the Fix and Perm kit (Thermo) for 20 min and washed with saturation buffer (SB; PBS with 2 % fetal bovine serum). Next, cells were permeabilized in the presence of the dsRNA Ab clone J2, anti-nucleocapsid rabbit pAb (GeneTex, #GTX135357) and ACE2-murine Fc IgG1k recombinant protein to detect the spike. After three washes, cells were incubated with a mixture of Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies in Perm media for 20 min. Secondary antibodies used for dsRNA were Goat anti-Mouse IgG2a Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 488 (Thermo, #A-21131) and for viral proteins the anti-Rb IgG conjugated Alexa Fluor™ 488 (Abcam, #Ab15077) or anti-mouse Abberior STAR RED conjugated Fab fragments. Cells were analyzed with an Abberior Infinity STED super-resolution microscope system equipped with an HCX PL APO 60 X/1.42 NA oil objective.

Transfection of distinct mRNAs

Vero E6 cells were transfected with LNP mRNA FLuc or LNP mRNA eGFP (ProMab Biotechnologies; PM-LNPs-0024 and PM-LNPs-0021) into white-96-well plates at 6–8 ×104 cells/well. We used 2 µl of LNP mRNA per well or no mRNA were added in the absence or presence of 50 nM plitidepsin. Transfected cells were incubated for 48 h and assayed for luciferase expression with Bright Glo Luciferase system (Promega; # E2610) or for eGFP expression by FACS. Samples were analyzed with Canto Flow Cytometer (BD) using FlowJo software to evaluate collected data. To evaluate any drug or mRNA-associated cytotoxic effect, Vero E6 cells were equally treated and assessed 48 h after transfection using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent viability assay (Promega). Luminescence was measured with an EnSight Multimode Plate Reader (PerkinElmer).

Effect of plitidepsin on cellular viability

8x104 Vero E6 cells per well were seeded in a 96 well plate and treated with or without 50 nM of plitidepsin for 48 h or with 10 % DMSO as toxicity control. Next, cells were labeled with the LIVE/DEAD Fixable Near-IR (775) stain probe (Thermo, #L34975) and acquired with a Canto Flow Cytometer (BD) using FlowJo software to evaluate collected data. Cells treated with increasing concentrations of plitidepsin for 48 h were also assayed for ATP content with CellTiter-Glo luminescent viability assay (Promega) or with the tetrazolium-based colorimetric method (MTT). The luminometer and spectrophotometer used an EnSight Multimode Plate Reader (PerkinElmer).

Transcriptomic analysis

1 ×106 Vero E6 cells per well seeded in a 24-well plate were infected with D614G at MOI 0.02 in the presence or absence of 50 nM plitidepsin for 4 h, 24 h and 48 h using 3 biological replicates per condition. At the indicated timepoints, cells were lysed with TRIzol™ (Invitrogen, 15596026 and 15596018). RNA was extracted with a Nucleospin RNA Magenerey-Nagel extraction kit and sequenced with Illumina TruSeq RNA w/ Ribo-Zero library, with coverage Novaseq 6000 150 bp PE (150x2bp) 60 M reads/spl (9 Gb/spl) by Macrogen. Paired-end sequencing was performed according to standard TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Reference Guide (1000000040499 v00) protocol using TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Gold Kit. All samples passed quality control checks and were aligned using bowtie257 version 2.5.1 to the SARS-CoV-2 variant EPI_ISL_510689 and the reference ASM985889v3. For host alignment, the reference genome GCA_023783515.1 and the human genome (GRCh38, ENSEMBL version 109) were used. RSEM58 v1.3.1 was used to create the indexes of these genomes and calculate the gene expression. Viral transcripts for the forward and reverse strands were calculated with:

rsem-calculate-expression --bowtie2 --paired-end --time -p ${threads} --append-names --no-bam-output --strandedness ${strandedness} ${strand1} ${strand2} ${viral_transcriptome} ${rsem_viral_out}_${strandness}.

Host transcripts were calculated with:

rsem-calculate-expression --bowtie2 --paired-end --time -p ${threads} --append-names --no-bam-output --strandedness “none” ${strand1} ${strand2} ${host_transcriptome} ${rsem_host_out}.

Where strand1 and strand2 are the path to the paired fastq file, the *_transcriptome is the path to the appropriate reference via rsem-prepare-reference. Later the effective library size was calculated with edgeR calcNormFactors which multiplies the original library sizes by a scaling factor to normalize using trimmed mean of M-values (TMM).

Detection of eEF1A expression

6×104 Vero E6 cells per well seeded in 96 well plates were infected with a MOI of 0.02 with the D614G variant in the presence or absence of 50 nM of plitidepsin. Cells were washed 48 h later and fixed and perm as previously described. Cells were stained with mAb mouse IgG anti-EEF1A (Santa Cruz; #SC2178) and revealed with secondary Goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 647 (Jackson Immunoresearch; #115-606-071). Cells were acquired by FACS Canto using FlowJo software to evaluate collected data.

Effect of plitidepsin on IRES-mediated translation

250 ng of the bicistronic reporter plasmid pcDNA3 RLUC POLIRES FLUC (Addgene plasmid #4524, kind gift from Nahum Sonenberg) was transfected with X-tremeGENE HP Transfection Reagent (Roche) into 6 × 104 Vero E6 cells per well seeded in 96 well plates 24 h before. Cells treated with or without 50 nM plitidepsin were assayed 48 h post-transfection with the Dual-Glo® Luciferase Assay System (Promega; #E2920) or the Renilla-Glo® and Bright-Glo™Luciferase Assay Systems (Promega, #E2710 and #E2610). Luminescence was measured with an EnSight Multimode Plate Reader (PerkinElmer). 200 ng of the molecular clone HIV-Gag-eGFP obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Bei resources #ARP-11468) was used to transfect 6 × 104 Vero E6 cells seeded 24 h before transfection. Cells were transfected with X-tremeGENE HP Transfection Reagent (Roche) and assayed 48 h later by FACS to measure the percentage of GFP expressing cells. Samples were analyzed with Canto Flow Cytometer using FlowJo software to evaluate collected data.

Effect of plitidepsin on m6A-mediated translation

HIV-1 reporter pseudoviruses expressing VSVg glycoprotein and luciferase were generated using two plasmids. pNL4-3.Luc.R-.E- was obtained from the NIH AIDS repository. VSV-G plasmid was kindly provided by A. Cimarelli. Plasmids were transfected with X-tremeGENE HP Transfection Reagent (Roche) into HEK-293T cells. Supernatants were harvested 48 h later, filtered with 0.45 µM (Millex Millipore) and stored at −80 °C until use. Viruses were titrated in Vero E6 cells. Next, 6 × 104 Vero E6 cells per well were seeded into white-walled 96-well plates and infected with VSVg pseudotyped pNL4-3.Luc.R-.E- viruses. Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of plitidepsin (PharmaMar), zidovudine (Merck), dolutegravir (Viiv healthcare) or mock-treated. In some experiments, the following inhibitors targeting m6A readers were also used: CWI1-2 and Tegaserod (all from MedChemExpress). Two days post-infection, luciferase expression was assessed with the Bright Glo Luciferase system (Promega). To evaluate any drug-associated cytotoxic effect, Vero E6 cells were equally cultured into black-walled 96-well plates and cell viability was assessed 48 h after using the CellTiter-Glo assay (Promega). Luminescence was measured with an EnSight Multimode Plate Reader (PerkinElmer).

HIV-1 GFP particles pseudotyped with VSVg were generated by transfection33 and kindly provided by Dr. Julia Garcia Prado. Briefly, HIV-1 packaging plasmid pCMVR8.2 for lentiviral particle formation was co-transfected with vector genome pCSGW-GFP for reporter of integration along with vector envelope MDG-VSVG for entrance. Vero E6 cells were infected with this virus at a MOI of 1 for 48 h in the absence and presence of increasing concentrations of plitidepsin and dolutegravir. Cell-associated GFP was measured by FACS and results were confirmed with a GFP ELISA (Abcam).

mRNA FLuc with a 5’ capped end, an uncapped 5’ end methylated with 50 % of m6A, and an uncapped 5’end which cannot be translated were purchased from OZ Biosiences. Vero E6 cells were seeded 24 h before transfection with mRNA FLuc. A premixed solution containing the X-tremeGENE HP Transfection Reagent (Roche) and the FLuc mRNA was prepared at a 3:1 ratio (µl X-tremeGENE HP: µg mRNA) with a total of 0.2–0.5 µg of mRNA per well or no mRNA, in a serum-free Opti-Mem medium (Gibco). After a 15 min incubation at RT, mixes were added to Vero E6 cells and cells were mock-treated or treated with or without 50 nM plitidepsin. Transfected cells were incubated for 48 h and assayed for luciferase production with Bright Glo Luciferase system (Promega). To evaluate any drug or mRNA-associated cytotoxic effect, Vero E6 cells were equally treated and assessed 48 h after transfection using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent viability assay (Promega). Luminescence was measured with an EnSight Multimode Plate Reader (PerkinElmer).

Antiviral activity against MERS-CoV

Increasing concentrations of plitidepsin or remdesivir were added to 8 × 104 Vero E6 cells per well seeded in 96 well plates and immediately after, cells were infected with equivalent infectious units of MERS-CoV titrated to induce a 60 % of cytopathic effect, at a MOI of 0.01. Untreated non-infected cells and untreated virus-infected cells were used as negative and positive controls of infection, respectively. To detect any drug-associated cytotoxic effect, Vero E6 cells were equally cultured in the presence of increasing drug concentrations, but in the absence of virus. Cytopathic or cytotoxic effects of the virus or drugs were measured 3 days post-infection, using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega). Luminescence was measured in a Fluoroskan Ascent FL luminometer (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Antiviral activity against ZIKV