Abstract

Biological ion channels exhibit strong gating effects due to their zero-current closed states. However, the gating capabilities of artificial nanochannels have typically fallen short of biological channels, primarily owing to the larger nanopores that fail to completely block ion transport in the off-states. Here, we demonstrate solid-state hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks-based membranes to achieve high-performance ambient humidity-controlled proton gating, accomplished by switching the proton transport pathway instead of relying on conventional ion blockage/activation effects. Density functional theory calculations reveal that the reversible formation and disruption of humidity-induced water bridges within the frameworks facilitates the switching of proton transport mode from the adsorption site hopping to the Grotthuss mechanism. This transition, coupled with the introduction of bacterial cellulose to enhance desorption/adsorption of water clusters, enables us to achieve a superior proton gating ratio of up to 5740, surpassing state-of-the-art solid-state gating devices. Moreover, the developed membrane operates entirely on solid-state principles, rendering it highly versatile for a myriad of applications from environmental detection to human health monitoring. This study offers perspectives for the design of efficient proton gating systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gating channel proteins in biological cell membranes play a pivotal role in regulating ion flow by opening or closing ion channels in response to environmental stimuli, crucial for the maintenance of life1,2,3. Drawing inspiration from nature’s elegant design, researchers have embarked on constructing artificial smart gating ion channels, anticipating wide applications in biosensors, energy conversion, and ion separation4,5,6,7. Typically, the modulation of ionic gating is usually achieved by chemical modification strategies, such as inducing structural transformation in responsive molecules functionalized on the channel walls or altering the charge polarity within the nanochannel8,9,10. These alterations enable changes in pore size and surface properties11,12, thereby exerting precise control over ion transport, producing unique ion blockage or activation effects13,14,15. Nevertheless, despite their promise, existing approaches often fall short in achieving complete ion obstruction, leading to undesired high-current levels during closed states16. This manifests as currents in off-states typically within the magnitude of tens of nanoamperes. Particularly challenging is the effective gating of protons, characterized by their minimal radius of motion. The conventional chemical modification strategies struggle to efficiently modulate proton transport, necessitating novel avenues for enhanced gating efficiency.

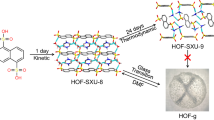

To achieve efficient ionic gating, a promising approach involves building/disrupting ion pathways by switching ion transport modes, rather than solely focusing on altering pore size or charge properties. Take protons as an example (Fig. 1a, b): when transported via the Grotthuss mechanism, they travel in chain-like manner through hydrogen bond networks (HBNs)17, akin to continuous bridges formed by water molecules, enabling ultrafast proton transport18. In contrast, protons must encounter larger potential barriers between the neighboring adsorption sites (known as adsorption site hopping mechanism), leading to sluggish or even obstructed ion transport. These two distinct processes exhibit vastly different transportation barriers, resulting in disparate migration rates. Currently, transitioning between the two transport modes proves challenging due to the uncontrollable nature of hydrogen bonding interactions in the conventional ionic gating systems that function in aqueous environment19,20. In quasi-solid or solid-state materials such as polystyrene sulfonate (PSS)21,22, polydiallyldimethylammonium chloride (PDACl)21, and covalent organic frameworks (COF)23,24, irreversible HBNs constrain the flexible modulation of water bridges. To this end, uniform and densely distributed hydrogen-bonding sites are indispensable25. Hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks (HOFs)26,27, emerging as two-dimensional (2D) porous crystals, constructed by periodic hydrogen-bonding interactions that exhibit a remarkable propensity for breakage and repair facilitated by moisture28, provide a promising platform for the reversible formation of water bridges. This unique means of modulating water bridges is expected to enable the switch of the proton transport mode for achieving high-performance gating effect.

The reversible formation and disruption of humidity-induced water bridges within HOFs facilitates the switching of proton transport mode from the adsorption site hopping (a) to the Grotthuss (b) mechanism. Further addition of BC (c) substantially enhances the desorption and adsorption capability of water clusters in low and high RH environments, respectively. The transition of proton transport mode, coupled with the enhanced desorption/adsorption behavior of water clusters, collectively contributed to the achievement of ultra-high proton gating with an on-off ratio of approximately 5740 (d). The Ei (i = 1, 2, 3, 4) symbol stands for energy.

Herein, we have observed a high-performance ambient humidity-controlled proton gating effect in 1,2,4,5-tetrakis (4-carboxy-phenyl)-benzene (H4TCPB) based 2D HOF composites. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations reveal that the proton transport process atop H4TCPB monomer plays a pivotal role in determining the overall transport dynamics, and can be switched from adsorption site hopping to the Grotthuss mechanism by forming reversible water bridges through HBNs. Moreover, the moisture adsorption/desorption capacity can be further strengthened by expanding the layer spacing of HOF-H4TCPB membranes with bacterial cellulose (BC) (Fig. 1c). The designed solid-state proton gating membrane achieved an impressive on-off ratio of up to 5740 (Fig. 1d), which is far superior to that of traditional solid gating membranes, such as polyelectrolyte gel diodes29,30, heterogeneous membrane diodes31, and others32,33. This accessible proton gating device with good mechanical flexibility holds promise for applications in agroforestry management and human health monitoring. Importantly, the efficient proton gating by switching proton transport paths provides a strategy for designing superior nanofluidic gating devices.

Results

Two-dimensional HOF-H4TCPB membrane with humidity-dependent conductivity

The 2D HOF-H4TCPB was prepared via one-step self-assembly process of H4TCPB in a mixed solution of water and N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) with molar ratio of 1:1 (Fig. 2a). Detailed synthesis process was provided in the Methods section. Nuclear magnetic resonance, high-resolution mass spectrometry, ultraviolet spectroscopy and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) demonstrated the clear structure of the H4TCPB and HOF-H4TCPB (Supplementary Figs. 1–5). Crystallographic data demonstrate detailed structural information of HOF-H4TCPB (Supplementary Table 1). Indeed, the water molecules can participate in hydrogen bonding (–COOH···H2O) and assist the fabrication of HOF-H4TCPB due to their strong hydrogen bond forming ability. This conclusion was further verified by scanning electron microscope (SEM), FTIR and thermogravimetric analysis (Supplementary Figs. 6–8). The successfully prepared ultrathin HOF-H4TCPB exhibits a nanosheet structure with a lateral size ranging from 1 to 2 μm and a thickness of approximately 2.24 nm (Supplementary Figs. 9–10). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) images in Fig. 2b demonstrate that the nanosheet possesses a regular structure with good crystallinity. Moreover, the obtained HOF-H4TCPB can form a stable mixed suspension in water solution with strong Tyndall Effect, indicating its good dispersibility owing to the abundance of hydrogen bonding (Supplementary Fig. 11). The FTIR confirms the presence of functional -COOH groups on the surface of HOF-H4TCPB (Supplementary Fig. 12). Additionally, the HOF-H4TCPB nanosheets can be readily reassembled via a vacuum-assisted filtration method to form a white, self-supported 2D membrane with a typical lamellar nanochannels structure (Supplementary Figs. 13–14). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern further indicates that the characteristic peak of the HOF-H4TCPB membrane at 7.45°, which is consistent with the simulated result (Supplementary Fig. 15), corresponding to an interlayer distance of approximately 1.18 nm, as determined by the Bragg diffraction formula. This value is consistent with the lattice fringe spacing of approximately 1.20 nm revealed by cross-sectional high-resolution TEM (Fig. 2c).

a Schematic of the preparation of HOF-H4TCPB. b TEM image and SAED pattern of the HOF-H4TCPB nanosheet. c The cross-section high-resolution TEM of HOF-H4TCPB. The embedded figures show locally enlarged TEM image and reveal a lattice spacing of 1.20 nm. d Absorbed water contents of HOF-H4TCPB as the function of ambient humidity, showing that ambient humidity promotes effective water uptake by such membrane. e, f, XPS fine spectra of HOF-H4TCPB membrane treated with ambient humidity of 0% RH (e) and 97% RH (f), revealing water uptake facilitates the construction of the HBNs. g The ionic conductivity of HOF-H4TCPB membrane as a function of ambient humidity. h I-V curves of the HOF-based gating device in 20% and 97% RH, respectively, evidenced by a nearly 140-fold difference in proton transport rates. i Variations of the proton gating ratio in response to RH value. Each experiment in b and c was repeated three times independently with similar results.

HOF-H4TCPB demonstrates excellent hydrophilicity, exhibiting a water contact angle of only 16.3° compared to conventional hydrophilic membranes such as cellulose (51.3°) and GO (59.6°) (Supplementary Fig. 16). This characteristic endows HOF-H4TCPB with the ability to absorb water from its surroundings. The water absorption behavior of the HOF-H4TCPB at various ambient humidities reveals a notable increase in water content within the membrane, rising from 4% to 25% as the relative humidity (RH) increased from 0 to 97% RH (Fig. 2d). This observation shows that ambient humidity promotes effective water uptake by the HOF-H4TCPB membrane. Fortunately, the XRD patterns show good crystallinity even at humidity ranging from 20% RH to 97% RH, indicating the excellent robustness of the structure (Supplementary Fig. 17a, b). The shifts of the main peaks are primarily caused by the additional water molecules occupying the layer space. This water uptake facilitates the formation of the water bridge, thereby promoting the construction of the HBNs, as supported by a 60-fold increase in -OH groups when ambient humidity rises from 0 to 97% RH, observed through the high-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (HRXPS) analysis (Fig. 2e, f and Supplementary Fig. 18). Furthermore, the FTIR at various humidity displays red-shifted characteristic peaks of -OH groups, from 3471 cm−1 to 3346 cm−1 with increasing ambient humidity. This was attributed to the participation of water molecules in hydrogen bonds, that construct a substantial hydrogen bonding network, which drives the formation of water bridges in the HOF-H4TCPB membrane (Supplementary Fig. 19).

The proton transport behavior was first investigated using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). Analysis of the Nyquist plots revealed that the HOF-H4TCPB membrane exhibits minimal conductivity at 20% RH. However, as the RH increases, the measured conductivity rises accordingly, reaching an impressive 1.52 mS cm−1 at 97% RH (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Fig. 20 and Supplementary Table 2). This notable conductivity enhancement can be attributed to the formation of interconnected HBNs facilitated by abundant water molecules. Obviously, the proton transport within HOF-H4TCPB membrane can be precisely regulated by RH. Moreover, the ionic conductivity of HOF-H4TCPB membranes gradually decreased as the membrane thickness increased (Supplementary Fig. 21). This was primarily attributed to the prolongation of proton migration routes caused by the thicker membrane, which consequently reduced the efficiency of proton transport. However, reducing the membrane thickness also resulted in poor self-support. Consequently, HOF-H4TCPB membranes with an optimal thickness of about 25 µm are typically utilized in our work. To ensure the directed transport of protons, an ion gating device was constructed using electrodes with different redox potentials to drive them (Fig. 1c)34. The proton migration properties of the HOF-H4TCPB membrane at various RH levels were investigated by current-voltage (I-V) measurements using such a device in a homemade humidity test setup (Supplementary Fig. 22). Under the regulation of humidity, a nearly 140-fold difference in proton transport rates was achieved, as evidenced by the increase of short-circuit current from 16.5 to 2308 nA (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. 23). The cross-over point between the ON and OFF states is significantly shifted from 0 due to an initial potential difference for driving the directional transport of ions created by asymmetric electrodes. The gating behavior, quantified by the gating ratio Ion/Ioff, where Ion represents the short-circuit current at high humidity (ranges from 20% to 97% RH) and Ioff represents the short-circuit current at 20% RH, increases upon rising RH (Fig. 2i).

Proton transport mechanism revealed by DFT calculations

DFT calculations were conducted to elucidate the underlying mechanism governing the highly efficient proton gating behavior. In the context of 2D HOF nanosheet, which is formed through hydrogen bonding interactions between H4TCPB and water molecules, the overall proton transport is contributed by two regions: region 1 housing hydrogen bonding connections and region 2 occupied by the H4TCPB monomers (Fig. 3a). Within region 2, where hydrogen-bonded interactions are absent, proton transport relies on the adsorption site hopping mechanism with a sluggish rate attributable to a notable energy barrier of 2.06 eV (Fig. 3b). Upon the addition of more water molecules, the energy barrier substantially decreases to 0.33 eV owing to the formation of numerous HBNs. It is noteworthy that the energy barrier in region 1 remains unaltered, as the existence of intrinsic hydrogen-bonded interaction enables the realization of the Grotthuss mechanism, thereby rendering it independent of humidity levels. These findings underscore that the proton transport atop the H4TCPB monomer plays a dominant role in the gating effect.

a For the 2D HOF nanosheet, the overall proton transport is contributed by two regions: region 1 housing hydrogen bonding connections, and region 2 occupied by the H4TCPB monomers. b Comparison of the binding energy of proton through region 1 and region 2 of HOF-H4TCPB in low/high RH. The inset shows the proton transport atop the H4TCPB monomer (region 2) plays a dominant role in the gating effect. c–f Proton transport pathway (c, e) and energy profile (d, f) in low (c, d) and high (e, f) RH in region 2. The Ets symbol stands for energy barrier. Structures of HOF-H4TCPB after kinetic optimization in low (g) and high (h) water contents. i The MSD of the optimized HOF-H4TCPB in low and high H2O contents, respectively, exhibits that the protons mobility rate within HOF + H2O is 1.66 times higher than that of within the HOF structure.

In detail, when the content of water molecule is low, the proton jumps from one -COOH end of the H4TCPB to the other -COOH end (Fig. 3c). Throughout this process, the benzene ring serves as a transit station for proton adsorption, thereby allowing proton migration along the Adsorption Site A-H. The overall migration potential rises to 2.06 eV (Fig. 3d) owing to the strong interaction between proton and the benzene ring, coupled with the substantial confinement experienced during proton jumping. However, under high humidity condition, where the HBNs are established, the adsorbed protons undergo ultrafast Grotthuss transportation along the water bridges on HOF-H4TCPB (Fig. 3e), thereby experiencing a notable reduction in energy barrier to 0.33 eV (Fig. 3f). This transition signifies the switch in proton transport on HOF-H4TCPB membranes from adsorption site hopping to the Grotthuss mechanism facilitated by the formation of reversible water bridges through HBNs. The ion transport activation energies (Εa) through the HOF-H4TCPB membranes with varying RH would help to gain further understanding of the ion transport mechanism. It is observed that as the humidity level of the membrane increased from 20% RH to 97% RH, the proton transport activation energy decreased from 9.65 kJ mol–1 to 3.16 kJ mol–1 (Supplementary Fig. 24). The decrease in Εa at high humidity further signifies the switch in proton transport on HOF-H4TCPB membranes from adsorption site hopping to the Grotthuss mechanism. This transition can be vividly illustrated in the optimized large area of the HOF structure in Fig. 3g, h. At low water contents, water clusters congregate around the junction between the H4TCPB monomers, interconnected solely by the benzene ring of H4TCPB. As the water content increases, excess water molecules bridge these clusters, forming a continuous network for proton transport35. Figure 3i displays the mean square displacement (MSD) of protons within the HOF and HOF + H2O models. Notably, the migration of protons within HOF + H2O surpasses that within the HOF structure, exhibiting a mobility rate 1.66 times higher in the presence of water. This underscores the substantial enhancement in proton migration within the HOF membrane under high humidity condition.

Improved proton gating performance

The gating performance of HOF-H4TCPB membranes is further optimized by the intercalation of BC with abundant -OH functional groups (Supplementary Fig. 12). The XRD pattern of the HOF-H4TCPB/BC membrane displays the characteristic peaks of the above two components separately, confirming their homogeneous composition. Additionally, the additional characteristic peaks in the composite membrane primarily originate from the BC structure (Supplementary Fig. 25). The as-prepared HOF-H4TCPB/BC membranes exhibit a pronounced fiber structure and expanded 2D nanochannels compared to pristine HOF-H4TCPB membranes (Supplementary Figs. 26–27), thereby promoting the rapid water molecule adsorption/desorption kinetics and accelerates the establishment of a reversible water bridge. Importantly, HOF-H4TCPB/BC composite membranes exhibit excellent structure stability at humidity ranging from 20% RH to 97% RH (Supplementary Fig. 17c). Ionic conductance measurements unveil a charge-governed ionic transport behavior across the HOF-H4TCPB/BC membrane (Fig. 4a). Specifically, in regions of high-concentration, the conductance follows the bulk rule, demonstrating a linear correlation with increasing concentration. While, as the concentration of HCl decreases (<10−2 M), the conductance first decreases and gradually approaches a plateau, suggesting that protons can more readily move within the interlayer nanochannels.

a Conductance of the HOF-H4TCPB/BC composite membrane as the function of HCl concentration. b I-V curves of the optimized gating device in 20% and 97% RH, respectively. The gating ratio (c), on-off speed (d), and Zeta potential (e) of the gating device based on BC, HOF-H4TCPB and their composite membranes. f Variations of the on-off speed in response to different BC contents. g Variations of the gating ratio of improved device in response to RH value. h Continuous long-time switching response over an hour, revealing excellent cyclic stability of the optimized gating device. i On-off ratio of HOF-based gating devices triggered by simple ambient humidity far exceeds that of conventional solid-state gating units triggered by a variety of complex conditions.

The proton migration properties of the HOF-H4TCPB/BC membrane at 20% and 97% RH levels were investigated by I-V measurements (Fig. 4b). Under the regulation of humidity, almost three orders of magnitude difference in proton transport rates were achieved, as evidenced by the substantial increase of short-circuit current from 0.5 to 2870 nA. When integrating the HOF-H4TCPB/BC membrane into a gating device, an extraordinarily high on-off ratio of 5740 was observed, surpassing those of devices based solely on pure BC (~5) and HOF-H4TCPB (~140) membranes (Fig. 4c). The gating speed, including recovery (response) speed, exhibited a substantial increase from 0.77 nA/s (0.69 nA/s), 28.97 nA/s (36.67 nA/s) to 66.58 nA/s (57 nA/s), corresponding to devices based on BC, HOF-H4TCPB, and their composite membranes, respectively (Fig. 4d). The addition of aramid nanofibers (ANF) or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) has also been shown to improve the gating performance of the HOF-H4TCPB. It has demonstrated gating ratios of approximately 1877.8 and 342.7, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 28). These values are significantly higher than those of the pure HOF-H4TCPB membrane (~140), highlighting the effectiveness of polymer intercalation. Nevertheless, the optimization of ANF or PVA was observed to be considerably less effective than that of BC. This notable enhancement in gating performance can be attributed to the introduction of hydrophilic BC, which not only increases the interlayer distance, facilitating fast flow of water molecules but also enhances the negative surface charge (Fig. 4e), thereby promoting efficient proton transport. However, it’s worth noting that excessive BC content may disrupt the HOF-dominated HBNs, leading to markedly reduced gating speed. Optimal switching speed of this device is observed when the HOF-H4TCPB: BC ratio is 5:2, as shown in Fig. 4f. Furthermore, as the ambient humidity increases from 20% to 97% RH, the switching ratio of the HOF-H4TCPB/BC-based device increases gradually from 1 to 5740 (Fig. 4g), underscoring that the proton gating behavior can be precisely regulated by the water molecules. In addition to its excellent humidity dependence, this gating device exhibits superior gating response repeatability, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig 29. The continuous long-time switching response over an hour demonstrates the excellent cyclic stability of this equipment (Fig. 4h). It is noteworthy that the gating effect of this proton gating device triggered by simple ambient humidity far exceeds that of conventional solid-state gating units triggered by a variety of complex conditions, such as ZIF-8 modified with sulfonated spiropyran36, sub-nanometer-sized MXene37, COF-DHTA/TAPB membrane38, etc39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50 (Fig. 4i and Supplementary Table 3).

Insight into the improved proton gating behavior

The underlying reason for the improved gating performance was revealed by DFT calculations. The BC-optimized HOF-H4TCPB membrane exhibited larger on-currents compared to the normal HOF in a wet environment (Fig. 5a). Notably, HOF-H4TCPB/BC demonstrated drastically reduced off-currents when modulated in dry surroundings (Fig. 5b), thereby contributing to the exceptionally high switching ratios. Actually, the gating properties of HOF-H4TCPB are inextricably related to the electronegativity of H4TCPB. As depicted in the electrostatic potential map in Fig. 5c, the -COOH moiety in the H4TCPB monomer exhibits the highest electronegativity, facilitating the adsorption of water molecules onto the HOF structure. Since the intercalation of BC leads to the expansion of the HOF-H4TCPB layer spacing, two distinct models were developed to simulate the structure before and after BC intercalation (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 30). The intrinsic mechanism of the dramatic decrease in the off-current was further elucidated by the examination of desorption of water clusters. Initially, water clusters within the pristine HOF-H4TCPB exhibited a strong adsorption effect (Ead = 3.02 eV), primarily due to the compact layer spacing. These water molecules can be strongly bound by the upper and lower layers of -COOH, forming a stable hydrogen bonding network. However, after expansion of the interlayer, the water clusters can only be adsorbed on the unilateral -COOH (Ead = 2.74 eV). These water molecules are only connected by hydrogen bonds between H2O-H2O, which is a weaker interaction compared to the bonding between H2O-COOH. The differential adsorption of water molecules on the HOF and expanded HOF structure further elucidate the observed phenomena (Fig. 5e). As a result, the off-current of composite membrane experiences a significant reduction in comparison to pristine HOF, as illustrated in Fig. 5f. In high RH environment, the HOF-H4TCPB/BC shows improved water adsorption characteristics, primarily stemming from the embedding of BC which expands the interlayer spacing of HOF (Fig. 5g). Consequently, water molecules are more accessible to HOF-H4TCPB/BC, inducing more complete HBNs. As a result, HOF-H4TCPB/BC demonstrates an optimized on-current compared to the HOF membrane with restricted nanospaces of approximately 1.32 nm. Overall, the optimized HOF-H4TCPB/BC membrane is able to achieve enhanced desorption of water clusters in low RH conditions and also enhanced adsorption of water clusters in high RH environments, collectively contributing to the achievement of ultra-high proton gating capabilities.

Comparison of the on-currents (a) and off-currents (b) between HOF-H4TCPB/BC and HOF-H4TCPB-based gating devices. c Electrostatic potential (ESP) surface of H4TCPB monomer (unit: Hartree/e). The blue and red colors denote less and more electron density in the ESP surface, respectively. d Differential charge diagrams of HOF-H4TCPB and expanded HOF structures. The yellow and blue areas denote the electron-losing and the electron-gaining, respectively. The Ead symbol stands for adsorption energy. e The adsorption energy as a function of water contents on the structures of expanded HOF and HOF-H4TCPB, respectively. f After BC intercalation, the water desorption capability in low RH was strengthened due to the weakened adsorption within the expanded HOF layers. g After BC intercalation, the water adsorption capability was augmented as the HOF-H4TCPB/BC structure offers increased accessibility for water molecules, thereby inducing more complete HBNs.

All solid-state proton gating devices for agroforestry and human health monitoring

The addition of BC nanofibers not only strengthens the humidity sensing properties through the synergetic effect with HOF but also endows the HOF membrane with excellent mechanical properties51(Supplementary Fig. 31), giving the device promising prospects for solid-state applications in humidity monitoring. Moisture is one of the most critical parameters in daily production activities, especially in domains such as granaries, farmland and orchards52, where diligent monitoring of the moisture content in both the storing environment and the nurturing soil is imperative (Fig. 6a). An optical image showcasing a soil moisture monitoring employing the gating device is shown in Supplementary Fig. 32. During the monitoring procedure, the HOF-H4TCPB/BC membrane was placed situated within the soil, shielded from the external environment factors that could compromise the precision of the monitoring outcomes. As shown in Fig. 6b, when the soil sample is dry, the device only records about 0.2 μA in the output short-circuit current signal. However, as the sample is gradually moistened by ambient humidity, the output signal escalates rapidly, maintaining robust humidity monitoring for up to 4 h of ambient humidity treatment (at that peak, the output signal reaches 11.9 μA). Moreover, to ascertain the precision of the proton gating unit, soil samples (i-iv) with varying moisture contents were used for moisture level monitoring (Fig. 6c). The recorded short-circuit current signals monitored through the gating device increased from 2.3 to 16 μA, corresponding to four soil samples ranging from 8% to 36% wt in moisture content, respectively. This reflects the accurate detection of the diverse moisture levels present in different soil samples, demonstrating the potential of the device for applications in agroforestry. In addition, the proton gating device demonstrated good signal stability over 10 cycles of operation (each monitoring session lasted 1 h) when soil moisture was kept constant. Importantly, the device maintained its structural integrity after multiple cycles, demonstrating its reusable and recyclable potential (Supplementary Fig. 33).

a Schematic of the moisture contents monitoring in both the storing environment and the nurturing soil, such as farmland, orchard, and granary. The optical photograph of the gating device. b Response curve of the gating device situated within the dry soil sample, which was then moistened by ambient humidity, showing robust monitoring of humidity for up to 4 h. c Response curve of soil samples (i-iv) with varying moisture contents. d Schematic of the relationship between human respiratory rate and health. A low respiratory rate is associated with poisoning or heightened intracranial pressure. A high respiratory rate is often associated with high fever, pain, anemia, hyperthyroidism, or heart failure. e Response curves of human breathing corresponding to different respiratory rates, demonstrating the precise monitoring of respiratory frequencies at 2.01–1.44 Hz, 0.22–0.38 Hz, and 0.05–0.06 Hz by the proton gating device. f Schematic of gating device in series with Bluetooth. Such device was mounted in a mask for wireless monitoring of human respiration.

The HOF-based solid-state proton gating devices offer versatile applications, extending beyond environmental monitoring to encompass human health tracking. Among vital health parameters, respiratory rate stands out as a crucial indicator, typically falling within the range of 12–20 breaths per minute for a healthy adult at rest53. A low respiratory rate may signal an overdose of anesthetics or sedatives, as well as heightened intracranial pressure. Conversely, a high respiratory rate often accompanies conditions such as fever, pain, anemia, hyperthyroidism, and heart failure (Fig. 6d). We monitored the human respiratory rate with this gating device, unveiling distinct response signals corresponding to different respiratory patterns (Fig. 6e). To facilitate this monitoring, the device was affixed inside a mask, with wireless Bluetooth technology enabling real-time data transmission for human respiration tracking (Fig. 6f). A seamless respiratory monitoring curve was monitored, demonstrating the device’s efficacy when integrated into the mask. The device remains stable and continues to monitor oral breathing effectively even when masks are disturbed during use, as the humidity from human breathing is not affected (Supplementary Fig. 34). Additionally, beyond respiratory monitoring, sweat emanating from human pores is also a source of humidity54. When a finger is brought close to the device, a corresponding response signal is generated, which diminishes as the finger recedes (Supplementary Fig. 35). Remarkably, finger perturbations, such as left-right and up-down, affect the output electrical signals of the device (Supplementary Fig. 36a). This is because the movement of the finger changes the position of the humidity source, demonstrating the excellent sensitivity of the device to non-contact interactions. Additionally, Supplementary Fig. 36b displays the non-contact signals from bare and gloved finger. The gloved finger did not trigger the device because it could not emit humidity, indicating that mechanical interference from non-humidity sources does not affect the device. This non-contact application offers valuable insights for mitigating wear and tear on high-precision instruments during long-term use, and to safeguard the human body against a wide range of bacterial microorganisms.

Discussion

In summary, we develop a solid-state 2D HOF-based proton gating membrane. Different from conventional gating channels employing chemical modification strategies that focus on altering pore size or charge properties, our developed proton gating membrane stands out for its unique ability to build/disrupt ion pathways by switching ion transport modes. This distinctive feature enables an exceptional gating effect, even for protons, which typically pose challenges for directional transport due to their minimal radius of motion. Through DFT calculations, we have elucidated that the overall transport dynamics across the 2D plane of the HOF nanosheet are primarily governed by the region occupied by the H4TCPB monomers, rather than the connection node. Within this region, the transport mode can be switched from adsorption site hopping to Grotthuss mechanism by forming reversible water bridges facilitated by HBNs. Moreover, the gating effect can be further enhanced by expanding the layer spacing of HOF-H4TCPB membrane with BC. Such expansion enhances the desorption and adsorption of water clusters in high and low RH environments, respectively, contributing to an extraordinarily high ratio of 5740 that is far superior to state-of-the-art solid-state gating devices. Importantly, our proton gating membrane operates entirely on solid-state principles, rendering it highly versatile for a myriad of applications, including those in environmental and human health areas. This work opens up avenues for the design of artificial ion gating membranes, starting from the conversion of proton transport pathways.

Methods

Synthesis of HOF-H4TCPB nanosheets

The HOF-H4TCPB was synthesized by the one-step self-assembly process of H4TCPB (purity~98%) in a mixed solution of water and DMF (purity~99.9%). Of these, the building block H4TCPB monomer was purchased from Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd (CAS: 1078153-58-8). Briefly, 0.1 mmol of H4TCPB was dissolved into 7.5 ml of DMF to obtain a clear solution by ultrasound for 10 min. Next, 162 ml of deionized water was added to the above solution. After stirring for 8 h at room temperature, a uniform colloidal suspension of HOF-H4TCPB nanosheets was obtained. Then, 324 ml of deionized water was added to the above suspension. After stirring for 15 min at room temperature, the solvent was removed by filtration using an aqueous filter membrane with 0.22 µm pore size. Finally, the products were dissolved in 20 ml of deionized water to obtain cleaned HOF-H4TCPB nanosheets dispersion (2 mg/ml).

Preparation of HOF-H4TCPB and HOF-H4TCPB/BC membranes

For HOF-H4TCPB membrane: The membrane was fabricated by vacuum filtrating 3.5 ml of the above HOF-H4TCPB nanosheets dispersion on an aqueous filter membrane. With respect to the HOF-H4TCPB/BC membrane: The HOF-H4TCPB dispersion was first diluted to a concentration of 2 mg/ml. Then, 5 ml of the above HOF-H4TCPB dispersion (2 mg/ml) was mixed with 2 ml of BC solution (3.2 mg/ml). After stirring for 20 min at room temperature, 3.5 ml of the above mixed solution was taken to prepare the HOF-H4TCPB/BC membrane by vacuum filtration method.

To obtain composite membranes with different BC percentages, we combined 5 ml of HOF-H4TCPB dispersion with 1 ml, 2 ml, 3 ml, and 4 ml of BC dispersion to produce composite dispersions with varying BC concentrations. Following 20 min stirring period, 3.5 ml of each of the aforementioned dispersions were taken and filtered to obtain HOF-H4TCPB/BC composite membranes with volume ratios of 5:1 (24.2 wt% BC), 5:2 (39.1 wt% BC), 5:3 (49.0 wt% BC), and 5:4 (56.1 wt% BC) respectively.

Assembly of proton gated devices

The HOF-H4TCPB membrane was trimmed into a 1.0 × 1.0 cm square for further device assembly. To fabricate the proton-gated device, the positive and negative electrodes were first fixed on the PET substrate by arranging the two electrode sheets parallel to each other. A piece of HOF-H4TCPB membrane was then placed on top of the arranged two electrode sheets. Finally, two PTFE sheets with 0.8 × 0.8 cm square holes and screws were used to stabilize the above device and ensure close contact between the HOF membrane and the positive and negative electrodes. Similarly, solid-state proton gated devices based on HOF-H4TCPB/BC membranes were assembled in the same way as described above.

Characterization

The structural characteristics of the HOF-H4TCPB and HOF-H4TCPB/BC membranes were measured using a Panalytical XRD (40 kV, 40 mA) with a Cu K(alpha) radiation wavelength of 1.541 84 Å. The XPS spectra of the HOF-H4TCPB membrane were collected on a Thermo K-alpha XPS system. The morphologies of the HOF-H4TCPB/BC and HOF membranes were recorded using an FEI Nova Nano SEM equipped. The crystal structure of the HOF-H4TCPB nanosheet was analyzed by TEM (FEI Titan G2 60−300) equipped with an EDS detector (Bruker) operated at 200 kV. The hydrophilicity of HOF, BC, and GO membranes was verified using a contact angle measurement instrument (JC2000D). The water adsorption capacity of the HOF-H4TCPB membrane was measured by a 917 Coulometric Karl Fischer Moisture Tester. The data collection and analysis through the employment of Origin 2021 and Keithley DMM7510 software.

Calculation of the interlayer spacing

In this work, the interlayer spacing of the HOF-H4TCPB membrane can be obtained by the following Bragg diffraction formula:

where d is the interlayer spacing, θ is the incident angle, n is the diffraction order and λ is the wavelength. The XRD pattern shows that the characteristic peak of the HOF-H4TCPB membrane is located at 7.45° (Supplementary Fig. 15). According to the formula, the interlayer distance of the 2D HOF membrane is ~1.18 nm.

Proton gating performance testing

The proton gating properties were investigated using a homemade moisture regulator (Supplementary Fig. 22). The regulator mainly consists of a gas transfer system for delivering dry/wet nitrogen and a sealing unit for keeping the environment around the gating device stable. Experiments performed with this moisture regulator were carried out at room temperature (25 °C) unless otherwise specified.

During testing, moist nitrogen is supplied through the nitrogen-water system to create a 97% RH test environment. Dry nitrogen is supplied via the nitrogen-desiccant system to maintain a 20% RH test environment. In addition, the alternating flow of wet and dry nitrogen gas to the sample causes periodic changes in the relative humidity environment inside the sealed chamber, resulting in alternating changes in the output electrical signals.

The temperature and humidity values inside the sealed chamber were recorded using a commercially available temperature/hygrometer. The electrical signals from the proton gating device were measured using the Keithley DMM7510.

Density functional theory calculations

All calculations were implemented in the Device Studio program, which provides several functions for performing visualization, modeling, and simulation. The structural optimization and energy calculations were performed using the DS-PAW software (Version 2023 A), that integrated into the Device Studio program. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) generalized gradient approximation with a plane wave cutoff of 400 eV was used for the exchange-correlation function. All atomic positions were fully relaxed with the conjugate gradient method. The energy convergence was 10−4 eV and the force convergence was 0.05 eV/Å. For all structural optimization and adsorption calculations, the k-point grid was set to 3 × 3 × 1. During adsorption and diffusion possesses, the DFT-D3 method with Grimme correction is adopted to describe the long-range van der Waals interactions.

The proton hopping on H4TCPB mainly depends on the adsorption sites near the hydroxyl group (Site A and H) and the adsorption sites of the benzene ring on H4TCPB (Site B-G) (Fig. 3c, d). In contrast, the transport of protons according to the Grotthuss mechanism depends on the hydroxyl adsorption sites near the water molecule (Sites I and J) (Fig. 3e, f). The diffusion pathways and barriers are obtained by using the climbing-image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are provided in the article, Supplementary Information and Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Pan, X. et al. Structure of the human voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1. 4 in complex with β1. Science 362, eaau2486 (2018).

Ramu, Y., Xu, Y. & Lu, Z. Enzymatic activation of voltage-gated potassium channels. Nature 442, 696–699 (2006).

Bezanilla, F., White, M. M. & Taylor, R. E. Gating currents associated with potassium channel activation. Nature 296, 657–659 (1982).

Zhao, C. et al. Enhanced gating effects in responsive sub-nanofluidic ion channels. Acc. Mater. Res. 4, 786–797 (2023).

Weintrub, B. I. et al. Generating intense electric fields in 2D materials by dual ionic gating. Nat. Commun. 13, 6601 (2022).

Steven, B., Gael, N., Stefan, H. & Siwy, Z. S. DNA-modified polymer pores allow pH-and voltage-gated control of channel flux. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9902–9905 (2014).

Xiao, J. et al. Electrolyte gating in graphene-based supercapacitors and its use for probing nanoconfined charging dynamics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 683–689 (2020).

Sun, Y. et al. A highly selective and recyclable NO-responsive nanochannel based on a spiroring opening−closing reaction strategy. Nat. Commun. 10, 1323 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Role of outer surface probes for regulating ion gating of nanochannels. Nat. Commun. 9, 40 (2018).

Ghosh, A. et al. Modular gating of ion transport by postsynthetic charge transfer complexation in a metal-organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27103–27112 (2023).

PéPez-Mitta, G. et al. An all-plastic field-effect nanofluidic diode gated by a conducting polymer layer. Adv. Mater. 29, 1700972 (2017).

PéPez-Mitta, G. et al. Proton-gated rectification regimes in nanofluidic diodes switched by chemical effectors. Small 14, 1703144 (2018).

Zhang, Z. et al. Bioinspired heterogeneous ion pump membranes: unidirectional selective pumping and controllable gating properties stemming from asymmetric ionic group distribution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 1083–1090 (2018).

Zhu, Z., Wang, D., Tian, Y. & Jiang, L. Ion/molecule transportation in nanopores and nanochannels: from critical principles to diverse functions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8658–8669 (2019).

Zhou, Y. et al. Dynamically modulated gating process of nanoporous membrane at sub-2-nm speed. Matter 5, 281–290 (2022).

Zhou, Z. et al. Conjugated microporous polymer membranes for light-gated ion transport. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo2929 (2022).

Ma, Z. et al. Anhydrous fast proton transport boosted by the hydrogen bond network in a dense oxide-ion array of s-MoO3. Adv. Mater. 34, 2203335 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Moisture-electric–moisture-sensitive heterostructure triggered proton hopping for quality-enhancing moist-electric generator. Nano-Micro Lett 16, 56 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Photo-controllable ion-gated metal–organic framework MIL-53 sub-nanochannels for efficient osmotic energy generation. ACS Nano 16, 16343–16352 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Laminar regenerated cellulose membrane employed for high-performance photothermal-gating osmotic power harvesting. Carbohydr. Polym. 292, 119657 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Hydrogel ionic diodes toward harvesting ultralow-frequency mechanical energy. Adv. Mater. 33, 2103056 (2021).

Lu, B. et al. Pure pedot: Pss hydrogels. Nat. Commun. 10, 1043 (2019).

Liu, X., Wang, J., Shang, Y., Yavuz, C. T. & Khashab, N. M. Ionic covalent organic framework-based membranes for selective and highly permeable molecular sieving. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 2313–2318 (2024).

Cao, L. et al. An ionic diode covalent organic framework membrane for efficient osmotic energy conversion. ACS Nano 16, 18910–18920 (2022).

Shi, B. et al. Short hydrogen-bond network confined on COF surfaces enables ultrahigh proton conductivity. Nat. Commun. 13, 6666 (2022).

Lin, R. B. & Chen, B. Hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks: chemistry and functions. Chem 8, 2114–2135 (2022).

Chen, C. et al. Hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks for membrane separation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 2738–2760 (2024).

Song, X. et al. Design rules of hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks with high chemical and thermal stabilities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 10663–10687 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Improved osmotic energy conversion in heterogeneous membrane boosted by three-dimensional hydrogel interface. Nat. Commun. 11, 875 (2020).

Zhuang, Z. et al. Thermal-gated polyanionic hydrogel films for stable and smart aqueous batteries. Energy Stor. Mater. 65, 103136 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. A bioinspired multifunctional heterogeneous membrane with ultrahigh ionic rectification and highly efficient selective ionic gating. Adv. Mater. 28, 144–150 (2015).

Xu, R. et al. Reversible pH-gated MXene membranes with ultrahigh mono-/divalent-ion selectivity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 6835–6842 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Anion-responsive poly(ionic liquid)s gating membranes with tunable hydrodynamic permeability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 32237–32247 (2017).

Wu, X. et al. A potentiometric mechanotransduction mechanism for novel electronic skins. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba1062 (2020).

Popov, I. et al. Search for a Grotthuss mechanism through the observation of proton transfer. Commun. Chem. 6, 77 (2023).

Liang, H. Q. et al. A light-responsive metal-organic framework hybrid membrane with high on/off photoswitchable proton conductivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 7732–7737 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Voltage-gated ion transport in two-dimensional sub−1 nm nanofluidic channels. ACS Nano 13, 11793–11799 (2019).

Cao, L. et al. Oriented two-dimensional covalent organic framework membranes with high ion flux and smart gating nanofluidic transport. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 134, e202113141 (2022).

Yu, X. et al. Gating effects for ion transport in three-dimensional functionalized covalent organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 134, e202200820 (2022).

Zhao, C. et al. Bioinspired self-gating nanofluidic devices for autonomous and periodic ion transport and cargo release. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1806416 (2019).

Qian, T. et al. Efficient gating of ion transport in three-dimensional metal-organic framework sub-nanochannels with confined light-responsive azobenzene molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 132, 13151–13156 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. Highly-efficient ion gating through self-assembled two-dimensional photothermal metal-organic framework membrane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202302997 (2023).

Ling, H. et al. Heterogeneous electrospinning nanofiber membranes with pH-regulated ion gating for tunable osmotic power harvesting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, e202212120 (2023).

Atesci, H. et al. Humidity-controlled rectification switching in ruthenium-complex molecular junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 117–121 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Electrostatic gating of a nanometer water channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 3687–3692 (2007).

Wang, J. et al. Smart touchless human-machine interaction based on crystalline porous cages. Nat. Commun. 15, 1575 (2024).

Ota, H. et al. Highly deformable liquid-state heterojunction sensors. Nat. Commun. 5, 5032 (2014).

Gong, X. et al. A charge-driven molecular water pump. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 709–712 (2007).

Liu, X. et al. Power generation from ambient humidity using protein nanowires. Nature 578, 550–554 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Bilayer of polyelectrolyte films for spontaneous power generation in air up to an integrated 1,000 V output. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 811–819 (2021).

Heise, K. et al. Nanocellulose: recent fundamental advances and emerging biological and biomimicking applications. Adv. Mater. 33, 2004349 (2021).

Reich, P. B. et al. Effects of climate warming on photosynthesis in boreal tree species depend on soil moisture. Nature 562, 263–267 (2018).

Addison, P. S. et al. Accurate and continuous respiratory rate using touchless monitoring technology. Resp. Med. 220, 107463 (2023).

Min, J. et al. Skin-interfaced wearable sweat sensors for precision medicine. Chem. Rev. 123, 5049–5138 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Suzhou Key Laboratory of Bioinspired Interfacial Science (SZ2024004), Start-up Funding for Suzhou Institute for Advanced Research, University of Science and Technology of China (KY2260080023, Z.Z), and Leading Talents of Innovation and Entrepreneurship of Gusu District (ZXL2023341, Z.Z). The material characterization tests were supported by the Physical and Chemical Analysis Center at Suzhou Institute for Advanced Research, University of Science and Technology of China. We gratefully acknowledge HZWTECH for providing computation facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. proposed the idea and the project. D.D.L. designed the experiment. Y.X.W. synthesized and characterized HOF nanosheets and HOF/BC membrane. Q.X.Z. and Y.X.W. performed the device fabrication and characterization. S.Q.W. did the agroforestry and human health monitoring experiments. Q.X.Z. performed the DFT calculations. Z.Z. and L.J. supervised the project. D.D.L., Y.X.W. and Z.Z. wrote the paper. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Niveen Khashab, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, D., Wang, Y., Zhang, Q. et al. High-performance solid-state proton gating membranes based on two-dimensional hydrogen-bonded organic framework composites. Nat Commun 16, 754 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56228-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56228-8