Abstract

The high performance of two-dimensional (2D) channel membranes is generally achieved by preparing ultrathin or forming short channels with less tortuous transport through self-assembly of small flakes, demonstrating potential for highly efficient water desalination and purification, gas and ion separation, and organic solvent waste treatment. Here, we report the construction of vertical channels in graphene oxide (GO) membrane based on a substrate template with asymmetric pores. The membranes achieved water permeance of 2647 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 while still maintaining an ultrahigh rejection rate of 99.9% for heavy metal ions, which is superior to the state-of-the-art 2D membranes reported. Furthermore, the membranes exhibited excellent stability during long-term filtration experiments for at least 48 h, as well as resistance to ultrasonic treatment for over 100 minutes. The vertical channels possess very short pathway for almost direct water transport and a highly effective channel area, meanwhile the asymmetric porous template enhances the packing of the inserted GO nanosheets to avoid the swelling effect of membrane. Our work provides a simple way to fabricate vertical channels of 2D nanofiltration membranes with high water purification performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A long-standing goal for nanofiltration and separation membranes is ultrahigh water permeance together with a high rejection rate1,2,3,4, which is particularly crucial but still challenging for multivalent ions sieving in the wastewater purification, brackish water separation, and seawater desalination as the rising global demand of freshwater5. Membrane separation is the key technology for multivalent and heavy metal ions separation6,7,8. Typically, the graphene-based nanofiltration membranes9,10,11, have significant achievements in toxic multivalent ions rejection12,13. However, improving water permeance while maintaining the high rejection of nanofiltration membranes still remains a great challenge9,14,15. For example, the highest water permeance of ~164.7 L m⁻2 h⁻1 bar⁻1 in the early report16, was still moderate, with a rejection of 85.2% for multivalent metal ions. This limits the practical applications of graphene-based membranes in a variety of fields17,18.

There have been previous efforts to improving the ion sieving performance of GO membranes. A simple and widely studied GO flakes with small lateral size, are usually thought to be potential for high-flux and energy-efficient membranes due to their shorter and less tortuous water channels2,19,20,21. Obviously, the direction of water transport along the planes of the GO flakes12,22, which we refer to as vertical channels, has the shortest water channels when the same amount of GO is used. Ultrathin GO membranes with a thickness less than 50 nm23,24,25 can also create shorter water channels, but they render the membrane highly unstable with respect to ion rejection and mechanical strength. A method reported for sieving ions through the vertical channels of a GO membrane involves encapsulating and stacking GO flakes together using Stycast epoxy12, however, this method showed a moderate water permeance due to the physical confinement imposed by the epoxy.

Here, we report the vertical channels of graphene oxide membranes by inserting and stacking GO flakes in a mixed cellulose ester (MCE) substrate with asymmetric pores. The membrane exhibited high ion sieving performance due to its unique water channel structure, including short and minimally tortuous water channels, as well as the resulting high-density water channels along the permeation direction. The water permeances reached up to 1106 to 2647 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 with rejection rates of 99.9% for heavy metal ions of Pb(NO3)2, CuSO4, ZnSO4, CrCl3, and FeCl3, which were approximately 7 to 15 times the highest water permeance of 2D membranes reported. In addition, the membranes exhibited a good stability in long-term filtration experiments. Notably, this approach to fabricating membranes with quasi-vertically asymmetric channels can be extended to other 2D materials like MXene, offering a straightforward method for producing high-performance nanofiltration membranes.

Results

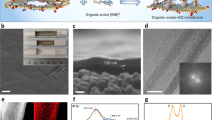

We chose a custom-made MCE membrane with asymmetric pores (diameter 50 mm, Tianjin Jinteng Experiment Equipment Co., ltd.) as the substrate, where one side has an average pore size of 0.2 μm and the other side has a large pore size of approximately 2 μm (Fig. 1b, c). GO flakes with a lateral size of approximately 450 nm were prepared from a GO suspension via an amino-hydrothermal method (AD-rGO) (see Supplementary Section 1). Then, using vacuum filtration, 40 mL of a 30 mg L−1 AD-rGO suspension was loaded onto the large pore side of MCE substrate, and the same amount suspension was loaded on the small pore side of another MCE substrate as a control. For the small pore side, the AD-rGO membrane was uniformly stacked on the substrate (Fig. 1d), resulting in a thin and layered membrane that was continuous and free of macro pores or defects. This is a typical GO membrane structure with 2D horizontal water channels stacked on the small pore side. While for the large pore side, the AD-rGO flakes were inserted into the large pore side of the substrate with only a few flakes stacked on the surface (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 1), no flakes were observed leaking from the other small pore side.

a Schematic of typical GO membrane with 2D horizontal water channels stacked on the substrate (left), and GO membrane with vertical channels based on a substrate with asymmetric pores (right). Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of small-pore side (b) and large-pore side (c) of a mixed cellulose ester (MCE) substrate. Small-pore side has a pore size of approximately 0.2 ~ 0.5 μm, while the large-pore side has a pore size of approximately 2 μm. d Cross-section and surface of AD-rGO membrane stacked on the small-pore side of MCE substrate. e SEM image of AD-rGO flakes inserted into the large-pore side of a MCE substrate. In the cross-section images of MCE substrate (i-iii), AD-rGO flakes have self-assembled within it. The red-shaded area marks the AD-rGO membranes, illustrating their main distribution within the MCE substrate. f Pure water permeances of the AD-rGO membranes. The membranes are stacked on the small pore side (with horizontal channels) and inserted into the large pore side (with vertical channels) of substrate, respectively. g Water permeances and rejection rates of the AD-rGO membrane with vertical channels for heavy metal ions. h Summary of the filtration performance of state-of-the-art membranes reported in the literature based on water permeances and rejection rates for heavy metal ions. Orange, green, and blue circles represent nanofiltration membranes (NFMs), two-dimensional material membranes (2DMS), and GO-based membranes (GOMs), respectively. The values are mean ± SD (n = 3).

The AD-rGO membranes with GO flakes inserting into the MCE substrate exhibited ultrahigh ion sieving performance. As shown in Fig. 1f, the pure water permeance through the membranes was 4169 L m−2 h−1 bar−1, demonstrating a significant advantage in water permeance compared to the typical layered membranes stacked on the small pore side of substrate (93 L m−2 h−1 bar−1). Then, 150 mL of 50 mg L−1 of different salt (Pb(NO3)2, CuSO4, ZnSO4, CrCl3, and FeCl3) solutions were added to the feed side, respectively. Under a pressure of 1 bar, the salt solutions were filtered through the membranes. As shown in Fig. 1g, the water permeances of the AD-rGO membrane were 2647 L m−2 h−1 bar−1, 1564 L m−2 h−1 bar−1, 1530 L m−2 h−1 bar−1, 1314 L m−2 h−1 bar−1, and 1106 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 with corresponding rejection rates of 99.9% for Pb(NO3)2, ZnSO4, CuSO4, CrCl3, and FeCl3, respectively. The water permeance of most heavy metal ions is similar, except for Pb(NO3)2, which has a higher permeance due to its relatively low molar concentration when compared to the same mass concentration. The relatively decreased water permeances for heavy metal ions compared to the pure water is attributed to the strong hydrated cation–π interactions that tune the interlayer spacing by cations9,26. The larger cation-π interactions of trivalent ions, such as Cr3+ and Fe3+, narrow the interlayer spacing and make it difficult for other hydrated cations with larger sizes in solution to enter the spacing, resulting in a higher rejection rate and a lower water permeance4,9. We note that the highest water permeance reported of nanofiltration membranes is about 164.7 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 with a rejection of 85.2% for multivalent metal ions16, as shown in Fig. 1h and Supplementary Table 1. Therefore, the water permeances of our membranes are superior to all other nanofiltration membranes, while still ensuring ultrahigh ion rejection.

Discussion

We attribute the ultrahigh water permeances to the vertical water channels in the AD-rGO membrane assembled on the substrate template, where AD-rGO flakes with suitable lateral sizes can be inserted and stacked within the substrate. By preparing the AD-rGO flakes with an average lateral size to approximately 450 nm (Fig. 2a, b), it is convenient to insert these flakes into the large pore side (approximately 2 μm) of the MCE substrate without leaking from the other small pore side (approximately 0.2 μm), allowing stable stacking of the AD-rGO flakes within the substrate. Such a simple structure greatly shortens the water pathway and increases the density of water channels (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 2).

a Atomic force microscope (AFM) image of AD-rGO flakes with corresponding height profiles taken along the marked white line. b Size distribution of AD-rGO and initial GO flakes measured by nanoparticle size analyzer. c C1s X-ray photoelectron spectrum of AD-rGO flakes. d C1s X-ray photoelectron spectrum of initial GO flakes. The spectrum is decomposed into five peaks, which correspond to the C-C/C = C (sp2 carbon), C-N, C-O-C/C-OH, C = O, and O = C-OH groups.

In addition, compared with initial GO (content of oxygen-containing groups ~31.3%)27,28, the AD-rGO prepared by the amino-hydrothermal method has a low content of oxygen-containing groups (~22%) and additional C-N groups (~4%) as analyzed by the C1s X-ray photoelectron spectrum (Fig. 2c, d). The low content of oxygen-containing groups causes the Zeta potential of AD-rGO (−28.8 mV) to be slightly lower than that of GO (−34.8 mV). The low content of oxygen-containing groups will decreases transport resistance due to the nearly frictionless flow on graphene surface11 and improves water permeance. For the sieving performance of heavy metal salt solutions, the water permeance of the initial GO membrane with horizontal channel was 64 L m −2 h −1 bar −1, with corresponding rejection rate of 98.9% reported in our previous work4. The cation-π interaction can be further enhanced due to the doped nitrogen29,30,31,32 in C-N groups (~4%). Our membrane also shows less affected by different anions (see Supplementary Fig. 3), which is beneficial for the rejection of heavy metals.

The effect of salt concentration on the ion sieving performance was further investigated, using CuSO4 as an example. 150 mL of CuSO4 solutions with a concentration of 25 ~ 200 mg L−1 was added to the feed side and filtered through the membranes under a pressure of 1 bar. As shown in Fig. 3a, the water permeance gradually decreased from 1880 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 to 899 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 as the concentration of CuSO4 solution increased from 25 mg L−1 to 200 mg L−1, while the rejection rate remained stable at 99.9%. The results show that higher salt concentration can reduce the water permeance. The strong hydrated cation–π interactions between Cu2+ and GO flakes that reduce the interlayer spacing by compressing the hydration shell of the Cu²⁺ ions. This interaction leads to a more compact structure, enhancing the rejection rates of multivalent ions by restricting their passage through the membrane. The higher salt concentration will further reduce the interlayer spacing, causing enrichment and blockage of salt ions in interlayer spacing, leading to lower water permeance affected by the concentration polarization33,34. The water permeance of 899 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 with a rejection rate of 99.9% still maintains a high efficiency, demonstrating the robust ion sieving performance of the AD-rGO membrane.

a Water permeance and rejection of AD-rGO membranes for different concentrations of CuSO4 solution. b Water permeance and rejection of AD-rGO membranes prepared with different AD-rGO masses for 50 mg L−1 CuSO4 solution. c Long-term filtration performance of AD-rGO membrane for 50 mg L−1 CuSO4 solution. The filtrate was collected every 250 mL for a total of 16 cycles using a semi-automatic vacuum filtration method. d Stability of the AD-rGO and GO membranes in the aqueous solution ultrasonic treated with 40 kHz for 100 min. The values are mean ± SD (n = 3).

Based on the Hagen–Poiseuille equation, the water flux is inversely proportional to the thickness of the membrane (Δx). We attribute this to the increase in channel length and transport resistance due to the increased thickness. However, a membrane with sufficient thickness can ensure it is free of defects and possesses mechanical strength, which is beneficial to the stability of the sieving performance. A gradient screening of the amount of AD-rGO has been performed (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 4). Notably, the membrane prepared with a mass of ~0.4 mg of AD-rGO reached ultrahigh water permeance of 2535 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 with a sufficient high rejection rate of 99.9% for 50 mg L−1 CuSO4 solutions. With a lower amount of AD-rGO, the membrane still maintains excellent ion sieving performance, which is superior to the typical layered membranes.

Furthermore, the membranes exhibit excellent stability during long-term filtration experiments. Taking a 50 mg L−1 CuSO4 solution as the initial feed liquid, the filtrate continuously flows through the membrane and was collected every 250 mL for a total of 16 cycles using semi-automatic vacuum filtration method (see Supplementary Section 1). As shown in Fig. 3c, the AD-rGO membrane exhibited high stability and promising anti-pollution performance (see Supplementary Fig. 5) in both the water permeance and rejection rate during continuous operation.

The stability of AD-rGO membrane in aqueous solutions was also tested by ultrasonic treatment at 40 KHz for 100 minutes in aqueous solutions. Compared with the rapid breakdown and dissolution of the GO membrane under ultrasonic treatment, the AD-rGO membrane remained stable for over 100 min, indicating that it is a robust membrane (Fig. 3d). With the help of the MCE substrate, the membrane can withstand high pressures of up to 8 bar and maintain their ion sieving performance (see Supplementary Fig. 6). The insertion and stacking of AD-rGO flakes inside the asymmetric channels of the MCE substrate, coupled with the hydrophobicity of the flakes based on low oxygen-containing groups, greatly improve the stability of the AD-rGO membrane in aqueous solutions.

The profiles of the PMF curves from our molecular dynamics (MD) simulation (see Supplementary Fig. 7) indicate that Cu2+ requires a large energy barrier to enter the channel, whereas the water molecule within the channel has a similar free energy to that in the bulk solution. This demonstrates a significant difference in permeability between heavy metal ions and water molecules within the channel. For the monovalent Na+, its PMF curve is similar to that of water molecules, showing only a slight energy barrier within the channel. We find that the hydrated structures of the multivalent ions within the interlayer spacings are distorted4, being smaller than those of hydrated ions in solution (see Supplementary Fig. 8 and 9). This decreased spacing together with the distortion of hydrated ions within it result in the large energy barrier to enter the channel. These results reveal the mechanism by which GO membrane channels effectively reject multivalent ions while allowing water molecules and low-valence ions to pass through quickly.

In summary, we have successfully achieved the vertical channels of AD-rGO membrane by inserting and stacking flakes in a custom-made substrate with asymmetric pores. The AD-rGO flakes with an average lateral size to approximately 450 nm can easily be inserted into the large pore side (approximately 2 μm) of the MCE substrate without leaking from the other small pore side (approximately 0.2 μm), guaranteeing stable stacking of the AD-rGO flakes within the substrate. This simple structure greatly shortens the water pathway and increases the density of water channels, resulting in the membrane exhibiting high ion sieving performance. Moreover, the membranes showed good stability in long-term filtration experiments.

Notably, based on the custom-made substrate with asymmetric channels, the quasi-vertically asymmetric channels of 2D nanofiltration membranes can be conveniently fabricated and easily extended to other 2D nanofiltration membranes, including MXene (see Supplementary Fig. 10 and 11), MoS2, and MOFs. In addition, for membranes with the same water channel structure, the water flux can be further influenced by the characteristics of the fluid (e.g., viscosity) and the intralayer properties of 2D flakes, such as surface chemistry, nanopores, wetting properties, and the complex boundary conditions of the membrane flake materials, as well as their interfacial interactions. The high density vertical transport channels construction reported in this work provides new inspiration for the fields of nanofiltration and separation membranes. Meanwhile, improvements in the intrinsic characteristics of the membranes, hold promise for further enhancing the ion sieving performance of 2D membranes.

Methods

Experimental operations

GO was prepared from natural graphite powder using the modified Hummers method. Smaller-sized GO flakes were subsequently obtained from GO using an amino-hydrothermal method and characterized by SEM, XPS, AFM, and a nanoparticle size and zeta potential analyzer. Vertical nanochannel membranes were obtained by vacuum filtration after adding an AD-rGO suspension to the large pore size of MCE substrate. The salt solutions were then introduced for vacuum filtration. The water permeability was calculated, and the initial and filtered ion concentrations of the salt solution were determined using ICP-OES.

Theoretical calculations

The potential of mean forces (PMFs) for an ion (Cu2+ or Na+) or a water molecule moving from the bulk solution into the vertical channel, were calculated by using the umbrella-sampling algorithm. The semi-empirical quantum chemistry calculations were performed to investigate the adsorption behavior of hydrated cations (denoted as cation-(H2O)8) on a graphene, referred to as cation-(H2O)8@graphene. The artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm, implemented in the ABCluster program, was employed to identify the most stable configurations of both the cation-(H2O)8@graphene and cation-(H2O)8 complexes.

Data availability

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article (and its Supplementary Information file), or available from the corresponding author on request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Chen, W. et al. High-flux water desalination with interfacial salt sieving effect in nanoporous carbon composite membranes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 345–350 (2018).

Han, Y., Xu, Z. & Gao, C. Ultrathin Graphene Nanofiltration Membrane for Water Purification. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 3693–3700 (2013).

Zhang, M. et al. Controllable ion transport by surface-charged graphene oxide membrane. Nat. Commun. 10, 1253 (2019).

Dai, F. et al. Ultrahigh water permeation with a high multivalent metal ion rejection rate through graphene oxide membranes. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 10672–10677 (2021).

Uliana, A. A. et al. Ion-capture electrodialysis using multifunctional adsorptive membranes. Science 372, 296–299 (2021).

Shannon, M. A. et al. Science and technology for water purification in the coming decades. Nature 452, 301–310 (2008).

Bolisetty, S. & Mezzenga, R. Amyloid–carbon hybrid membranes for universal water purification. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 365–371 (2016).

Xie, X. et al. Microstructure and surface control of MXene films for water purification. Nat. Sustain. 2, 856–862 (2019).

Chen, L. et al. Ion sieving in graphene oxide membranes via cationic control of interlayer spacing. Nature 550, 380–383 (2017).

Fang, A., Kroenlein, K., Riccardi, D. & Smolyanitsky, A. Highly mechanosensitive ion channels from graphene-embedded crown ethers. Nat. Mater. 18, 76–81 (2019).

Joshi, R. et al. Precise and Ultrafast Molecular Sieving Through Graphene Oxide Membranes. Science 343, 752–754 (2014).

Abraham, J. et al. Tunable sieving of ions using graphene oxide membranes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 546–550 (2017).

Wang, Z. et al. Graphene oxide nanofiltration membranes for desalination under realistic conditions. Nat. Sustain. 4, 402–408 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Nanoparticle-templated nanofiltration membranes for ultrahigh performance desalination. Nat. Commun. 9, 2004 (2018).

Sapkota, B. et al. High permeability sub-nanometre sieve composite MoS2 membranes. Nat. Commun. 11, 2747 (2020).

Yi, R. et al. Selective reduction of epoxy groups in graphene oxide membrane for ultrahigh water permeation. Carbon 172, 228–235 (2021).

Li, W.-W., Yu, H.-Q. & Rittmann, B. E. Chemistry: Reuse water pollutants. Nature 528, 29–31 (2015).

Sholl, D. S. & Lively, R. P. Seven chemical separations to change the world. Nature 532, 435–437 (2016).

Nie, L. et al. Realizing small-flake graphene oxide membranes for ultrafast size-dependent organic solvent nanofiltration. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz9184 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Effect of physical and chemical structures of graphene oxide on water permeation in graphene oxide membranes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 520, 146308 (2020).

Huang, H. et al. Ultrafast viscous water flow through nanostrand-channelled graphene oxide membranes. Nat. Commun. 4, 1–9 (2013).

Zhang, X. et al. Vertically transported graphene oxide for high-performance osmotic energy conversion. Sci. Adv. 7, 2000286 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Ultrathin, Molecular-Sieving Graphene Oxide Membranes for Selective Hydrogen Separation. Science 342, 95–98 (2013).

Xue, S. et al. Nanostructured Graphene Oxide Composite Membranes with Ultrapermeability and Mechanical Robustness. Nano Lett. 20, 2209–2218 (2020).

Cheng, L., Guan, K., Liu, G. & Jin, W. Cysteamine-crosslinked graphene oxide membrane with enhanced hydrogen separation property. J. Membr. Sci. 595, 117568 (2020).

Shi, G. et al. Ion Enrichment on the Hydrophobic Carbon-based Surface in Aqueous Salt Solutions due to Cation-π Interactions. Sci. Rep. 3, 3436 (2013).

Yi, R. et al. Ultrahigh permeance of a chemical cross-linked graphene oxide nanofiltration membrane enhanced by cation–π interaction. RSC Adv. 9, 40397–40403 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Bio-inspired graphene oxide-amino acid cross-linked framework membrane trigger high water permeance and high metal ions rejection. J. Membr. Sci. 659, 120745 (2022).

Shen, Y. et al. Organelle-targeting surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) nanosensors for subcellular pH sensing. Nanoscale 10, 1622–1630 (2018).

Ma, D. et al. C3N monolayers as promising candidates for NO2 sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 266, 664–673 (2018).

Varghese, S. S., Lonkar, S., Singh, K. K., Swaminathan, S. & Abdala, A. Recent advances in graphene based gas sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 218, 160–183 (2015).

Cui, H., Zheng, K., Zhang, Y., Ye, H. & Chen, X. Superior Selectivity and Sensitivity of C3N Sensor in Probing Toxic Gases NO2 and SO2. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 39, 284–287 (2018).

Parvatiyar, M. G. & Govind, R. Effect of dispersed phase on reducing concentration polarization. J. Membr. Sci. 105, 187–201 (1995).

McCutcheon, J. R. & Elimelech, M. Influence of concentrative and dilutive internal concentration polarization on flux behavior in forward osmosis. J. Membr. Sci. 284, 237–247 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFA1409800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12074341), and the Scientific Research and Developed Funds of Ningbo University (No. ZX2022000015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C. and P.L. conceived the ideas. L.C., J.J., C.H., F.Z., W.Z., X.D., and Y.F. designed the experiments and co-wrote the manuscript. C.H., J.J., J.Liu., J.Lan., S.H., H.Y., F.Z., and P.L. performed the experiments and prepared the data graphs. X.D., L.M., and S.G. performed the density functional theory computations. W.Z. and J.C. performed the molecular dynamics simulation. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Zhenghua Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, C., Jiang, J., Mu, L. et al. Quasi-vertically asymmetric channels of graphene oxide membrane for ultrafast ion sieving. Nat Commun 16, 1020 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56358-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56358-z

This article is cited by

-

From Membranes to Electrodes: Aligned Membrane Electrode Assemblies for Ion-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells and Water Electrolyzers

Electrochemical Energy Reviews (2026)