Abstract

In nature, plants convert solar energy into chemical energy via water oxidation. Inspired by natural photosynthesis, artificial photosynthesis has been gaining increasing interest in the field of sustainability/green science and technology as a non-natural and thermodynamically endergonic (ΔG° > 0, uphill) solar-energy-driven reaction that uses water as an electron donor and a source material. Among the artificial-photosynthesis processes, inorganic-synthesis reactions via water oxidation, including water splitting and CO2-to-fuel conversion, have been attracting much attention. In contrast, the synthesis of high-value functionalized organic compounds via artificial photosynthesis, which we have termed artificial photosynthesis directed toward organic synthesis (APOS), remains a great challenge. Herein, we report a synthetically pioneering and meaningful strategy of APOS, where the carbohydroxylation of C = C double bonds is accomplished via a three-component coupling with H2 evolution using dual functions of semiconductor photocatalysts, i.e., silver-loaded titanium dioxide (Ag/TiO2) and rhodium–chromium–cobalt-loaded aluminum-doped strontium titanate (RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Natural photosynthesis, which involves a series of complicated cascade reactions in plants, plays an essential role in the energy flow on the earth1,2. It starts from water oxidation in the light phase, followed by reductive immobilization of CO2 to produce energy-rich glucose in the dark phase (the Calvin cycle). The overall reaction scheme acquires chemical energy from renewable solar energy with a change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG°) of +2880 kJ mol−1 (Fig. 1a, left). Based on the characteristic features of naturally occurring photosynthesis, artificial photosynthesis has been defined by Inoue as a non-natural and thermodynamically uphill reaction (ΔG° > 0) driven by solar energy using water as an electron donor and a source material3,4. Water splitting and CO2-to-fuel conversion represent promising artificial photosynthesis approaches in which the starting materials are inorganic compounds such as water and CO25,6. For a carbon-neutral and sustainable society, the development of chemical transformations of relatively large and functionalized organic compounds to produce value-added chemicals using environmentally friendly methods is essential7. We use the term, artificial photosynthesis directed toward organic synthesis (APOS), to describe a synthetically useful organic-to-organic transformation meeting all the criteria of artificial photosynthesis (Fig. 1a, right)8. There are seminal works of endergonic organic synthesis partially meeting the criteria of artificial photosynthesis, where water has rarely been used as an electron donor; and/or synthetic utility has scarcely been discussed in terms of scalability and applicability to structurally complex/pharmaceutically relevant organic substrates9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18.

a Natural photosynthesis (left) and artificial photosynthesis directed toward organic synthesis (APOS) (right, this work). b Radical-to-cation crossover-cascade mechanism of the carbohydroxylation of styrene derivatives in a wasteful manner (previous work) and through clean C–H bond activation with H2 evolution (this work). LG = leaving group, e.g., AcO−, N2 + BF4−, ArI + BF4−; X• = heteroatom-centered radical, e.g., tBuO•, iPrO•; e– = electron.

The carbohydroxylation of C = C double bonds in styrene derivatives is one of the most powerful and straightforward tools for the one-step construction of highly functionalized alcohols (Fig. 1b)19,20,21,22,23. In a representative radical-to-cation crossover-cascade (conversion of a carbon-centered radical to a carbocation) mechanism, the addition of a carbon-centered radical (•R) to a C = C double bond in a styrene derivative gives a relatively stable benzylic radical intermediate, which is converted to a carbocation. The cationic center intercepts water, affording an alcohol as the three-component coupling product. Although several transition-metal-catalyzed, electrochemical, and photocatalytic methods are available for the carbohydroxylation of styrene derivatives using activated initial radical precursors24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, the use of the radical precursors with leaving groups (LG ≠ H) inevitably leads to the formation of stoichiometric quantities of thermodynamically stable waste (ΔG° < 0, downhill), and some LGs undergo undesirable substitution with nucleophilic water (Fig. 1b, top left)24. A greener alternative and more attractive strategy for achieving the carbohydroxylation involves C–H bond activation to generate the carbon-centered radicals, in which two electrons and two protons are in total released from organic substrates and water (Fig. 1b, bottom)32. From the viewpoint of atom economy, the ideal byproduct is H2, whose molecular weight is no more than 2 g/mol. Furthermore, H2 is in practice not wasteful and an attractive energy source/carrier because it is nonpolluting and releases a drastic amount of heat or electric energy along with clean water upon its combustion with O2 (e.g., in a fuel cell)33. However, in previously reported carbohydroxylation reactions via C–H bond activation, excess amounts of oxidants giving X• (X• = heteroatom-centered radical) were used, leading to stoichiometric quantities of energy-poor waste (XH) instead of energy-rich H2 (Fig. 1b, center left)34,35,36. These conventional processes become thermodynamically exergonic (ΔG° < 0) because energy is released/consumed when waste is formed; in other words, not energy-productive. Even though well-designed photocatalytic systems have recently enabled unique dehydrogenative transformations8,37,38, sunlight has not yet been used, and the role of water as the electron donor as well as the potential scalability of such reactions for organic synthesis remain to be established.

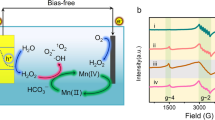

We have previously reported that C–H bonds of organic solvents can be activated to cleanly generate carbon-centered radicals through hydrogen-atom transfer (HAT) to an aqueous hydroxyl radical (•OH), which is oxidatively generated from water on a silver-loaded titanium dioxide (Ag/TiO2) photocatalyst under near-UV-light irradiation (Fig. 2a left)39. Hisatomi and Domen have developed a highly efficient rhodium–chromium–cobalt-loaded aluminum-doped strontium titanate (RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al) photocatalyst for overall water splitting evolving H2 through water oxidation to O2 under near-UV- or solar-light irradiation (Fig. 2a right)40,41,42.

a Our previous achievements in organic synthesis (left) and in water splitting (right). b Optimization study. Reaction conditions: 1a (0.1 mmol), 2a (1 mL, 19.0 mmol), H2O (100 μL), PC-1 (10.0 mg), PC-2 (10.0 mg), and LiOH (2 μmol) under LED irradiation (λ = 365 nm) and an N2 atmosphere at room temperature for 24 h. The yields of 3aa, 4, and 5 were determined by 1H NMR analysis (theoretical yield of 5: 50 μmol); H2 was quantified by μGC-TCD. aConversion of 1a: 100%, selectivity to 3aa: 72%, yield of CO2: 7 μmol, yield of O2: <1 μmol. bYield of CO2: 22 μmol, yield of O2: 24 μmol.

Here, we show a synthetically meaningful and thus potentially scalable example of APOS. Aiming at the three-component, carbohydroxylation reactions via APOS, we propose a redox-efficient dual photocatalytic system of Ag/TiO2 and RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al involving a stoichiometric oxidant-free multi-redox cascade, starting with the homolytic cleavage of one O–H bond of water to give a •OH (oxidation), followed by a homolytic C–H bond scission by the •OH (oxidation), a radical-to-cation crossover (oxidation), and H2 evolution (reduction) (Fig. 1b bottom and 2a). Remarkably, water plays multifunctional roles in this coupling reaction: as a •OH source to promote the C–H bond activation, as an electron donor for H2 evolution, and as a source of the oxygen atom incorporated into the alcohol product (–OH). The reaction proceeds under light irradiated from near-UV LEDs and also from a solar simulator. Density-functional-theory (DFT) calculations suggest that this transformation is thermodynamically uphill (ΔG° > 0: endergonic). The synthetic potential of the present transformation is highlighted by a short synthesis of terfenadine, a pharmaceutically important anti-histamine compound.

Results

Reaction optimization

Our investigations started by exploring various combinations of semiconductor photocatalysts (Fig. 2b, PC-1 and PC-2) for the three-component coupling of α-methyl styrene (1a), acetonitrile (2a), and water to furnish alcohol 3aa and H2. Using Ag/TiO2 in the absence of other photocatalysts afforded 4 as the two-component adduct of 1a and 2a (14%; Entry 1), which is consistent with our previous work39. Pristine SrTiO3:Al in combination with Ag/TiO2 also gave 4 (4: 15%; Entry 2), whereas RhCr/SrTiO3:Al selectively gave three-component-coupling product 3aa with H2 evolution (3aa: 22%, 4: <1%, H2: 90 μmol; Entry 3). Meanwhile, RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al drastically improved the yield of 3aa and H2, which were obtained along with a small amount of 5, most likely resulting from the dimerization of the benzylic radical intermediate (3aa: 72%, 5: 9%, H2: 160 μmol; Entry 4). Although using Pt/TiO2 instead of RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al prevented the formation of 4 and promoted the H2 evolution, 5 was obtained as the major product instead of 3aa (3aa: <10%, 5: 42%, H2: 80 μmol; Entry 5). This result suggests that RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al plays a critical role not only in the H2 evolution but also in the oxidative radical-to-cation crossover from the benzylic radical to the corresponding benzylic cation. Using RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al in the absence of the Ag/TiO2 photocatalyst, oxidative side reactions of 1a proceeded, affording CO2 (22 μmol) with H2 (220 μmol) (Entry 6; Supplementary Figs. 4b and 6). Thus, RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al independently extracts electrons from the organic compounds, causing their oxidative degradation accompanied by the evolution of H2. This could partially account for the fact that an excess of H2 (160 μmol) was detected along with CO2 (7 μmol) (Fig. 2b, Entry 4; Supplementary Figs. 4a and 5; a more detailed elucidation of the mass balance is shown in Supplementary Fig. 10). Although the products generated via the C–H bond activation of 2a were hardly detected in the absence of Ag/TiO2 (3aa, 4, and 5: <1%; Entry 6), pristine TiO2 catalyzed this transformation in combination with RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al, albeit with a relatively low efficiency (3aa: 31%; Entry 7). Accordingly, Ag/TiO2 is indispensable for the efficient activation of the C–H bond. All these results are consistent with the mechanistic blueprint of the dual photocatalytic semiconductors system (Fig. 2a). Further optimization showed that loading an appropriate amount of Ag on TiO2 was critical (0.5 wt% Ag; Supplementary Table 1). Moreover, the optimal ratio between Ag/TiO2 and RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al was determined to be 1:1 (w/w; Supplementary Table 2). Although the three-component coupling also proceeded to some extent under more neutral conditions without base additives, LiOH more effectively promoted the reaction (Supplementary Table 3). The concentration and volume of the aqueous solution of LiOH were optimized (H2O: 100 μL, LiOH: 2 μmol; Supplementary Table 4). The positive role of a tiny amount of LiOH is speculated as follows: LiOH provides Li+ and –OH. Referring to a survey of LiOH-promoted (photo)electrochemical water oxidation using cocatalyst-loaded TiO2 electrodes43, the adsorption of –OH on the TiO2 photocatalytic surface is enhanced by Li+ through noncovalent interactions formed as in TiO2–OH–Li+(OH2)x (x = hydration number), and –OH would be more easily oxidized to •OH8. In contrast, a larger amount of LiOH would form inorganic salt layers on the TiO2 surface, which causes the inhibition of adsorption/activation of organic molecules including 2a on the TiO2 surface43,44. A series of control experiments revealed that each photocatalyst, water, N2 substitution, and near-UV-light irradiation were indispensable (Supplementary Table 5). After the optimization study, the standard conditions shown in Fig. 3 (footnote) were established.

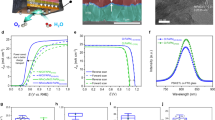

Standard conditions: 1 (0.1 mmol), 2 (1 mL), H2O (100 μL), Ag (0.5 wt%)/TiO2 (10.0 mg), RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al (10.0 mg), LiOH (2 μmol) under LED irradiation (λ = 365 nm) and an N2 atmosphere at room temperature for 24 h. Isolated yield of 3. H2 was quantified by μGC-TCD. Reaction time: a36 h, b48 h, c72 h, d96 h. e2a (2 mL), H2O (200 μL), LiOH (4 μmol). fAg/TiO2 (20.0 mg), gRhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al (20.0 mg). h1 mmol scale reaction using two Kessil lamps (λ = 370 nm). iDetermined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude mixture.

Substrate scope

With the standard conditions in hand, we explored the substrate scope of styrene derivatives (Fig. 3, top and center). In all cases, more than stoichiometric amounts of H2 were detected (>0.1 mmol) after the reactions. A wide variety of functionalized styrene derivatives is compatible with the present conditions. A relatively electron-rich methyl styrene 1b underwent this transformation more smoothly than electron-deficient derivatives 1c–1f (3ba: 51%; 3ca–3fa: 20–38%). These results suggest that the electron-donating group on the aromatic ring in the benzylic radical intermediate would be thermodynamically advantageous in the radical-to-cation crossover step45. F, Cl, and Br halogens were well tolerated (3da–3fa: 34–38%). An α,β-nonsubstituted styrene derivative gave the corresponding product in a relatively low yield (3ga: 35%), whereas 1,1-diarylethenes were more suitable substrates (3ha–3na: 44–71%). A reaction on the 1 mmol scale using 1,1-diphenylethylene was also successful (3 ha: 75%; Supplementary Fig. 1). Vinylpyridine and vinylthiophene derivatives as well as a β-methylated styrene derivative gave the products in moderate yield (3oa: 54%; 3pa: 19%; 3qa: 41%). A styrene derivative with a relatively complex structure synthesized from a drug molecule (fenofibrate) using the Wittig reaction was converted into a more functionalized product (3ra: 52%). A fully aliphatic 1,1-dialkylalkene (methylenecyclohexane) also gave the corresponding product, albeit in a low yield (12%, Supplementary Information pages 25).

We next investigated the applicability of carbon-centered radical precursors with different C–H bonds (Fig. 3, bottom). Water-miscible organic solvents were well suited to this transformation. The C–H bond functionalization of acetone smoothly furnished an equilibrium mixture of alcohol and cyclic hemiacetal in good yield (3hb + 6: 75%). The C(sp2)–H bond of acetaldehyde was functionalized smoothly (3hc: 52%). It was also possible to introduce a wide variety of functionalities into the organic frameworks, including cyclic ether (3hd, 3he: >70%), amide (3hf: 49%, 3hg: 42%), and carbamide (3hh: 36%) moieties. A relatively hydridic C–H bond of 1,4-dioxane (2 d) was selectively cleaved when 2a was used as a solvent (10 equivalent of 2 d and 190 equivalent of 2a, relative to 1 h) due to the electrophilic nature of •OH (3hd: 57%, 3 ha: 17%, Supplementary Table 6)45. In the case of acetic acid, C–H bond functionalization followed by cyclization gave γ-butyrolactone as a minor product (7: 9%), while 8 (16%) and 9 (43%) were obtained as major products via the addition of the O-centered carboxyl radical and the decarboxylatively formed methyl radical to the C = C double bond, respectively. These results suggest significant potential for carboxylic acids to serve as O-centered/C-centered carboxyl and alkyl radical sources in three-component coupling reactions with H2 evolution25,26,46,47,48,49,50. In contrast, less polar solvents did not give the two- and three-component coupling products, even though these are structurally similar to the successful ones (Supplementary Table 7). Such a solvent-specific behavior is consistent with our previous C–H bond functionalization reactions using aqueous •OH generated from water via Ag/TiO2 photocatalysis39.

Demonstration of APOS

To further illustrate the synthetic potential of this method, the synthesis of terfenadine (10; a histamine H1 receptor antagonist)51 was performed via the key carbohydroxylation (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Information pages 23–24). The reaction of commercially available 4-tert-butylstyrene (1g, 1 mmol) with 2a and water afforded a mixture of alcohol and ketone as the three-component coupling products (3ga: 32%; 11: 15%). The mixture of 3ga and 11 was subjected to reducing conditions using DIBAL-H to produce the identical cyclic hemiacetal (γ-hydroxy aldehyde) intermediate at low temperature. Subsequent reductive amination with amine 12 afforded terfenadine (10; 38% over three steps from 1 g). 1,1-Diarylethene 1s with a tethered nucleophilic hydroxy group gave 1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran derivative 13 (39%; Fig. 4b). This intramolecular cyclization, which proceeded via the smooth addition of the tethered alcohol to the benzylic cation, could be useful for the synthesis of bioactive molecules52.

Demonstration of the synthetic potential of this transformation: a synthesis of terfenadine and b application for cyclization. Meeting the requirements for artificial photosynthesis: c a solar-induced endergonic reaction with H2 evolution and d H2O serving as the oxygen source. e Plausible reaction mechanism; e– = electron, h+ = hole.

Finally, to confirm whether the main pathway involving the three-component coupling meets the criteria of artificial photosynthesis3, several control experiments and theoretical calculations were carried out. The endergonic nature of the reactions was confirmed by means of DFT calculations at the B3LYP/6-31 G(d, p) level (synthesis of 3aa: ΔG° = +60 kJ mol−1; 3 ha: ΔG° = +77 kJ mol−1; Fig. 4c, Supplementary Table 8). The synthesis of 3 ha with H2 evolution was also realized under irradiation with a xenon-lamp-based solar simulator (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 2). A labeling experiment using 18OH2 almost exclusively furnished 18O-labeled 3 ha, suggesting that water is the main source of the oxygen atoms incorporated into the alcohol products (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 3). Overall, the obtained experimental and theoretical results demonstrate that the present transformation can be regarded as an APOS.

Plausible mechanism

On the basis of the present results and those obtained in our previous studies on the C–H bond functionalization by Ag/TiO239 and water splitting by RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al40, a plausible redox-efficient mechanism can be proposed (Fig. 4e). Upon photoexcitation, TiO2 and SrTiO3:Al generate excited electron–hole pairs. The excited electrons and holes of SrTiO3:Al are accommodated in RhCr particles and in Co particles on the SrTiO3:Al surface, respectively40. Meanwhile, the excited electrons of TiO2 are deployed in the Ag particles on TiO2, and the holes are trapped by water molecules adsorbed on the TiO2 surface53. The interfacial water is oxidized to aqueous •OH by the holes of TiO2 (Since this reaction also proceeds in the absence of LiOH, H2O is depicted in Fig. 4e). The HAT to •OH from a C–H bond of a water-miscible organic molecule (2, R–H) restores water and produces a carbon-centered radical (R•)39. After the addition of R• to the C = C double bond of styrene derivative 1, the resulting benzylic radical is oxidized to the benzylic cation intermediate by the holes in the Co particles on the SrTiO3:Al surface, since Ag/TiO2 can barely oxidize benzylic radicals39. The nucleophilic attack of water on the carbocation affords three-component coupling product 3. Concurrently, water is oxidized to O2 by the holes in the Co particle on the SrTiO3:Al surface40. In practice, using RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al with organic substrates (1a and 2a) and water in the absence of Ag/TiO2, 24 μmol of O2 (Supplementary Figs. 4b and 6) was produced, whereas O2 was hardly detected after the three-component coupling under the standard conditions using the dual system of Ag/TiO2 and RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al (O2: <1 μmol, Supplementary Figs. 4a and 5). This result suggests that O2 generated via the RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al-promoted water oxidation is consumed by quenching the excited electrons at the Ag particles on the TiO2 surface, to restore water54. In this plausible scenario, O2 functions as a redox mediator (electron shuttle) between two semiconductors55,56,57, and O2 does not appear in the APOS scheme shown in Fig. 1a. Another possible product of water oxidation would be hydrogen peroxide; however, it was detected only in negligible quantities in a titration experiment using a titanium–porphyrin complex (Supplementary Fig. 9)58,59,60,61. Finally, a couple of excited electrons of SrTiO3:Al and a couple of protons accumulate and combine on the RhCr particles to produce H2.

In summary, we developed a photocatalytic system using water by merging the dual functions of Ag/TiO2 and RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al semiconductors into a one-batch operation for APOS. This system differs from our previously reported organic synthesis based on alcohol (an organic variant of water) splitting to produce aldehydes and H2 (ΔG° > 0) using an acidic aqueous media, since water was not necessarily an electron and hydrogen source in the latter case11. The carbohydroxylation of styrene derivatives with H2 evolution via C–H bond activation is an endergonic reaction induced by simulated solar light, where water plays three roles: as the •OH source, as the electron donor, and as the oxygen atom source. It should also be underlined that the round-trip step, from H2O to •OH (oxidation) and from •OH to H2O (reduction), is so fast and robust that this redox/HAT catalysis is essentially non-destructive and occurs inexhaustibly by using sufficient water. The chemoselective three-component coupling involves multiple redox/HAT processes to access a useful synthetic intermediate and enabled the rapid and greener synthesis of valuable and rather complex organic frameworks, including a pharmaceutical compound. The high-performance water splitting RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al catalyst was found to be a competent catalyst for the simultaneous H2 evolution and radical-to-cation crossover in organic synthesis when combined with another semiconductor. The artificial photosynthesis presented here would pave the way for useful green and sustainable organic synthesis methods promoted by semiconductor photocatalysts.

Methods

An oven-dried Pyrex glass test tube was charged with a magnetic stirrer bar, Ag/TiO2 (10.0 mg) and RhCrCo/SrTiO3:Al (10.0 mg). The vessel was sealed with a rubber septum and placed under nitrogen, and then 1 (0.10 mmol), 2 (1 mL) and an aqueous solution of LiOH (0.02 M, 100 μL) were added (1 that was not volatile was added with photocatalysts). The mixture was sonicated and then stirred under LED irradiation (λ = 365 nm). After 24 h, the gas phase was analyzed by μGC-TCD. The reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc and dried over Na2SO4. After filtration through a 0.45 μm membrane filter and concentration under reduced pressure (80 mmHg, 40 °C), the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel.

Data availability

The data generated in this study, including experimental procedures and characterization of products, are provided in the Supplementary Information. Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are also available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Johnson, M. P. Photosynthesis. Essays in Biochemistry 60, 255–273 (2016).

Ulmer, U. et al. Fundamentals and applications of photocatalytic CO2 methanation. Nat. Commun. 10, 3169 (2019).

Kuttassery, F. et al. 1. Artificial photosynthesis sensitized by metal complexes: utilization of a ubiquitous element. Electrochemistry 82, 475–485 (2014).

Lewis, N. S. & Nocera, D. G. Powering the planet: Chemical challenges in solar energy utilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103, 15729–15735 (2006).

Wang, Q. & Domen, K. Particulate photocatalysts for light-driven water splitting: mechanisms, challenges, and design strategies. Chem. Rev. 120, 919–985 (2020).

Yoshino, S., Takayama, T., Yamaguchi, Y., Iwase, A. & Kudo, A. CO2 Reduction using water as an electron donor over heterogeneous photocatalysts aiming at artificial photosynthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 966–977 (2022).

Anastas, P. & Eghbali, N. Green chemistry: principles and practice. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 301–312 (2010).

Yamauchi, M., Saito, H., Sugimoto, T., Mori, S. & Saito, S. Sustainable organic synthesis promoted on titanium dioxide using coordinated water and renewable energies/resources. Coord. Chem. Rev. 472, 214773 (2022).

Wang, H., Tian, Y.-M. & König, B. Energy- and atom-efficient chemical synthesis with endergonic photocatalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 745–755 (2022).

Sumin, A. L. & Knowles, R. R. Organic synthesis away from equilibrium: contrathermodynamic transformations enabled by excited-state electron transfer. Acc. Chem. Res. 57, 1827–1838 (2024).

Liu, Z., Caner, J., Kudo, A., Naka, H. & Saito, S. Redox-selective generation of aldehydes and H2 from alcohols under visible light. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 9452–9456 (2013).

Masuda, Y., Ishida, N. & Murakami, M. Light-driven carboxylation of o-alkylphenyl ketones with CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 14063–14066 (2015).

Mifsud, M. et al. Photobiocatalytic chemistry of oxidoreductases using water as the electron donor. Nat. Commun. 5, 3145 (2014).

Guo, Y., An, W., Tian, X., Xie, L. & Ren, Y.-L. Coupling photocatalytic overall water splitting with hydrogenation of organic molecules: a strategy for using water as a hydrogen source and an electron donor to enable hydrogenation. Green Chem. 24, 9211–9219 (2022).

Yuzawa, H. et al. Reaction mechanism of aromatic ring hydroxylation by water over platinum-loaded titanium oxide photocatalyst. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 25376–25387 (2012).

Yuzawa, H., Kumagai, J. & Yoshida, H. Reaction mechanism of aromatic ring amination of benzene and substituted benzenes by aqueous ammonia over platinum-loaded titanium oxide photocatalyst. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 11047–11058 (2013).

Yuzawa, H. et al. Anti-Markovnikov hydration of alkenes over platinum-loaded titanium oxide photocatalyst. Catal. Sci. Technol. 3, 1739–1749 (2013).

Park, S., Jeong, J., Fujita, K., Yamamoto, A. & Yoshida, H. Anti-Markovnikov hydroamination of alkenes with aqueous ammonia by metal-loaded titanium oxide photocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 12708–12714 (2020).

Courant, T. & Masson, G. Recent progress in visible-light photoredox-catalyzed intermolecular 1,2-difunctionalization of double bonds via an ATRA-type mechanism. J. Org. Chem. 81, 6945–6952 (2016).

Lan, X.-W., Wang, N.-X. & Xing, Y. Recent advances in radical difunctionalization of simple alkenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 39, 5821–5851 (2017).

Bao, X., Li, J., Jiang, W. & Huo, C. Radical-mediated difunctionalization of styrenes. Synthesis 51, 4507–4530 (2019).

Sharma, S., Singh, J. & Sharma, A. Visible light assisted radical‐polar/polar‐radical crossover reactions in organic synthesis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 363, 3146–3169 (2021).

Cramer, J., Sager, C. P. & Ernst, B. Hydroxyl groups in synthetic and natural-product-derived therapeutics: a perspective on a common functional group. J. Med. Chem. 62, 8915–8930 (2019).

Speckmeier, E., Fuchs, P. J. W. & Zeitler, K. A synergistic LUMO lowering strategy using Lewis acid catalysis in water to enable photoredox catalytic, functionalizing C–C cross-coupling of styrenes. Chem. Sci. 9, 7096–7103 (2018).

Shibutani, S., Nagao, K. & Ohmiya, H. Organophotoredox-catalyzed three-component coupling of heteroatom nucleophiles, alkenes, and aliphatic redox active esters. Org. Lett. 23, 1798–1803 (2021).

Tlahuext‐Aca, A., Garza‐Sanchez, R. A. & Glorius, F. Multicomponent oxyalkylation of styrenes enabled by hydrogen‐bond‐assisted photoinduced electron transfer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 3708–3711 (2017).

Fumagalli, G., Boyd, S. & Greaney, M. F. Oxyarylation and aminoarylation of styrenes using photoredox catalysis. Org. Lett. 15, 4398–4401 (2013).

Altmann, L.-M., Zantop, V., Wenisch, P., Diesendorf, N. & Heinrich, M. R. Visible light promoted, catalyst‐free radical carbohydroxylation and carboetherification under mild biomimetic conditions. Chem. Eur. J. 27, 2452–2462 (2021).

de Souza, E. L. S., Wiethan, C. & Correia, C. R. D. Iron-catalyzed meerwein carbooxygenation of electron-rich olefins: studies with styrenes, vinyl pyrrolidinone, and vinyl oxazolidinone. ACS Omega 4, 18918–18929 (2019).

Kindt, S., Wicht, K. & Heinrich, M. R. Thermally induced carbohydroxylation of styrenes with aryldiazonium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 8744–8747 (2016).

Xiong, P. et al. Electrochemically enabled carbohydroxylation of alkenes with H2O and organotrifluoroborates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 16387–16391 (2018).

Dalton, T., Faber, T. & Glorius, F. C–H activation: toward sustainability and applications. ACS Cent. Sci. 7, 245–261 (2021).

Yue, M. et al. Hydrogen energy systems: a critical review of technologies, applications, trends and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 146, 111180 (2021).

Yang, W.-C. et al. Vanadyl species-catalyzed complementary β-oxidative carbonylation of styrene derivatives with aldehydes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 13, 2385–2392 (2015).

Zheng, M. et al. Visible-light-driven, metal-free divergent difunctionalization of alkenes using alkyl formates. ACS Catal. 11, 542–553 (2021).

Ha, T. M., Chatalova-Sazepin, C., Wang, Q. & Zhu, J. Copper-catalyzed formal [2+2+1] heteroannulation of alkenes, alkylnitriles, and water: method development and application to the total synthesis of (±)-sacidum lignan D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 9249–9252 (2016).

Wang, H., Gao, X., Lv, Z., Abdelilah, T. & Lei, A. Recent advances in oxidative R1-H/R2-H cross-coupling with hydrogen evolution via photo-/electrochemistry. Chem. Rev. 119, 6769–6787 (2019).

Qi, M.-Y., Conte, M., Anpo, M., Tang, Z.-R. & Xu, Y.-J. Cooperative coupling of oxidative organic synthesis and hydrogen production over semiconductor-based photocatalysts. Chem. Rev. 121, 13051–13085 (2021).

Mori, S. & Saito, S. C(sp3)–H bond functionalization with styrenes via hydrogen-atom transfer to an aqueous hydroxyl radical under photocatalysis. Green Chem. 23, 3575–3580 (2021).

Lyu, H. et al. An Al-doped SrTiO3 photocatalyst maintaining sunlight-driven overall water splitting activity for over 1000 h of constant illumination. Chem. Sci. 10, 3196–3201 (2019).

Takata, T. et al. Photocatalytic water splitting with a quantum efficiency of almost unity. Nature 581, 411–414 (2020).

Nishiyama, H. et al. Photocatalytic solar hydrogen production from water on a 100 m2-scale. Nature 598, 304–307 (2021).

Ding, C. et al. Abnormal effects of cations (Li+, Na+, and K+) on photoelectrochemical and electrocatalytic water splitting. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 3560–3566 (2015).

Chen, H. Y., Zahraa, O. & Bouchy, M. Inhibition of the adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of an organic contaminant in an aqueous suspension of TiO2 by inorganic ions. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 108, 37–44 (1997).

Garwood, J. J. A., Chen, A. D. & Nagib, D. A. Radical polarity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 28034–28059 (2024).

Xue, Q. et al. Metal-free, n-Bu4NI-catalyzed regioselective difunctionalization of unactivated alkenes. ACS Catal. 3, 1365–1368 (2013).

Prathima, P. S., Maheswari, C. U., Srinivas, K. & Rao, M. M. CuI/l-proline-catalyzed selective one-step mono-acylation of styrenes and stilbenes. Tetrahedron Lett. 51, 5771–5774 (2010).

Li, Y., Song, D. & Dong, V. M. Palladium-catalyzed olefin dioxygenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 2962–2964 (2008).

Zhu, Q. & Nocera, D. G. Photocatalytic hydromethylation and hydroalkylation of olefins enabled by titanium dioxide mediated decarboxylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 17913–17918 (2020).

Schwarz, J. & König, B. Decarboxylative reactions with and without light – a comparison. Green Chem. 20, 323–361 (2018).

Perlmutter, J. I. et al. Repurposing the antihistamine terfenadine for antimicrobial activity against staphylococcus aureus. J. Med. Chem. 57, 8540–8562 (2014).

Ha, T. M., Wang, Q. & Zhu, J. Copper-catalysed cyanoalkylative cycloetherification of alkenes to 1,3-dihydroisobenzofurans: development and application to the synthesis of citalopram. Chem. Commun. 52, 11100–11103 (2016).

Shirai, K. et al. Effect of water adsorption on carrier trapping dynamics at the surface of anatase TiO2 nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 16, 1323–1327 (2016).

Kanakaraju, D., anak Kutiang, F. D., Lim, Y. C. & Goh, P. S. Recent progress of Ag/TiO2 photocatalyst for wastewater treatment: doping, co-doping, and green materials functionalization. Appl. Mater. Today 27, 101500 (2022).

Cheng, Y. et al. Spatiotemporally synchronous oxygen self‐supply and reactive oxygen species production on Z‐scheme heterostructures for hypoxic tumor therapy. Adv. Mater. 32, 1908109 (2020).

Nosaka, Y. & Nosaka, A. Y. Generation and detection of reactive oxygen species in photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 117, 11302–11336 (2017).

Maeda, K. Z-Scheme water splitting using two different semiconductor photocatalysts. ACS Catal. 3, 1486–1503 (2013).

Lachheb, H. et al. Photochemical oxidation of styrene in acetonitrile solution in presence of H2O2, TiO2/H2O2 and ZnO/H2O2. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 346, 462–469 (2017).

Li, X., Wang, Q., Lyu, J. & Li, X. Recent investigation on epoxidation of styrene with hydrogen peroxide by heterogeneous catalysis. ChemistrySelect 6, 9735–9768 (2021).

Yu, W. & Zhao, Z. Catalyst-free selective oxidation of diverse olefins to carbonyls in high yield enabled by light under mild conditions. Org. Lett. 21, 7726–7730 (2019).

Matsubara, C., Kawamoto, N. & Takamura, K. Oxo[5,10,15,20-tetra(4-pyridyl)porphyrinato]titanium(IV): an ultra-high sensitivity spectrophotometric reagent for hydrogen peroxide. Analyst 117, 1781–1784 (1992).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by MEXT/JSPS Grant-in-aid for Early-Career Scientists, Specially Promoted Research, Transformative Research Areas (A): Green Catalysis, and International Leading Research, KAKENHI (Grant # 24K17676 to S.M., 23H05404, 23H04904, and 22K21346 to S.S.). This work was also partially supported by JST CREST (Grant # JPMJCR22L2 to S.S.), Yashima Environment Technology Foundation (to S.M.), Iketani Science and Technology Foundation (to S.M.), The Naito Research Grant (to S.M.), and Foundation of Public Interest of Tatematsu (to S.M.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M. and S.S. conceived the project. S.M. and R.H. carried out the experiments. S.S., T.H., and K.D. supervise the research. S.M. and S.S. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mori, S., Hashimoto, R., Hisatomi, T. et al. Artificial photosynthesis directed toward organic synthesis. Nat Commun 16, 1797 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56374-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56374-z