Abstract

Gut microbiota disruptions after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT) are associated with increased risk of acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD). We designed a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial to test whether healthy-donor fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) early after alloHCT reduces the incidence of severe aGVHD. Here, we report the results from the single-arm run-in phase which identified the best of 3 stool donors for the randomized phase. The primary and key secondary endpoints were microbiota engraftment and severe aGVHD, respectively. Three cohorts of patients (20 total) received FMT, each from a different donor. FMT was safe and effective in restoring microbiota diversity and commensal species. Microbiota engraftment, determined from shotgun sequencing data, correlated with larger microbiota compositional shifts toward donor and better clinical outcomes. Donor 3 yielded a median engraftment rate of 66%, higher than donors 1 (P = 0.02) and 2 (P = 0.03) in multivariable analysis. Three patients developed severe aGVHD; all 3 had received FMT from donor 1. Donor 3 was selected as the sole donor for the randomized phase. Our findings suggest a clinically relevant donor effect and demonstrate feasibility of evidence-based donor selection. FMT is a holistic microbiota restoration approach that can be performed as a precision therapeutic. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT06026371

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite standard immunosuppressive prophylaxis, up to half of patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT) develop acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD). aGVHD is the clinical phenotype of an alloimmune attack by the graft against host tissues; classical targets are the gastrointestinal tract, skin, and liver1. aGVHD remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality after alloHCT and limits the success of this curative-intent procedure2.

Disruptions in the intestinal microbiota in the early peri-engraftment period have been associated with increased incidence and severity of subsequent aGVHD3,4,5,6,7. Multiple mechanisms seem to be involved. Increased degradation of colonic mucin glycans due to the expansion of mucolytic species brings intestinal bacteria and the immune system into closer contact and exacerbates aGVHD in meropenem-treated mice8,9. Butyrate production by the commensal gut microbiota may protect against aGVHD5,10. Microbiota species/strain-specific induction or suppression of MHC class II expression on intestinal epithelial cells modulates cognate antigen availability to T cells, affecting aGVHD initiation and severity11,12,13.

These and other findings have inspired microbiota restoration using fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) to prevent and treat aGVHD. Non-randomized studies have shown encouraging responses to FMT in some patients with steroid-refractory or high-risk treatment-naive aGVHD14,15,16. We have tested FMT in the prophylactic setting. In a recent randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial, we administered third-party oral FMT vs. placebo to alloHCT recipients at the time of neutrophil recovery17. FMT was safe in this highly immunocompromised patient population and ameliorated dysbiosis; it restored microbiota diversity and several commensal bacteria and reduced potential pathobionts17,18. Although the infection rate, the primary endpoint, was numerically lower in the FMT arm, the difference did not reach statistical significance. A trend for increased grade II–IV aGVHD was observed in the FMT arm. However, the small number of events and large imbalance between the two arms in GVHD prophylaxis regimens limited the interpretation. Post hoc analysis showed a strong negative association between donor microbiota engraftment and grade II–IV aGVHD19, suggesting that a more complete replacement of patient microbiota by healthy donor microbiota may be needed to reduce aGVHD. Additional analysis suggested that features of the donor product, such as abundance, antigenicity, and metabolic function of specific bacteria combined with their engraftment potential are also important in modulating aGVHD risk20, indicating a possible donor effect. Both engraftment efficacy and donor choice have been associated with clinical outcomes of FMT in other clinical settings21,22. To our knowledge, other than the required pathogen screening criteria, no microbiota-specific criteria have thus far been used for donor selection in FMT trials.

Our findings from the first trial suggested a need to enhance microbiota engraftment and optimize donor choice to prevent aGVHD. Therefore, we designed a follow-up trial with an initial single-arm run-in phase where we administered a larger dose of FMT and compared microbiota and clinical outcomes between 3 cohorts of patients, each treated with FMT from one of the 3 donors. The main objectives were to improve engraftment, identify the optimal donor, and use that donor as the sole FMT donor in the subsequent randomized placebo-controlled phase with the primary endpoint of aGVHD.

Here, we report the results from the pre-planned interim analysis at the end of the run-in phase. We corroborate our previous findings by demonstrating safety of early post-alloHCT FMT at a larger dose and its efficacy in restoring microbiota diversity and commensal species. In addition, we demonstrate evidence for donor dependence of microbiota engraftment and clinical outcomes, thus suggesting a donor effect in FMT.

Results

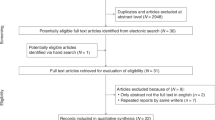

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Twenty patients received FMT and were evaluated for clinical outcomes. Fourteen additional patients were enrolled but did not start FMT. Product from donor 1, 2, and 3 was used in 6, 6, and 8 patients, respectively. FMT was started at a median of 25 days after HCT (range 19–40). The median interval from the last dose of antibacterial antibiotics until the first dose of FMT was 4 days (range 2–9). Two patients were exposed to antibacterial antibiotics (levofloxacin to treat a urinary tract infection and oral vancomycin to treat a C. difficile infection) between FMT initiation and the post-FMT sample and 1 did not provide the post-FMT sample. The remaining 17 patients were evaluable for engraftment. FMT in these patients was sex-matched in 7 and mismatched in the remaining 10. Supplementary Fig. S1 shows the patient/sample flow diagram.

Adverse events

Nineteen of the 20 patients who started FMT completed the planned week of treatment. In the remaining patient, treatment was discontinued after 5 days due to cytomegalovirus viremia and a skin rash. Both findings were later shown to be unrelated to FMT; the rash was due to sulfa allergy and the FMT donor was CMV seronegative, while both the patient and his stem cell donor were seropositive. No grade 3+ treatment-related AEs occurred. Most patients experienced transient grade 1–2 gastrointestinal symptoms during the week of treatment. Two DLTs occurred. One was a case of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection found on biopsy during esophagogastroduodenoscopy for work-up of nausea and early satiety 17 days after the last dose of FMT. Although the FMT donor for this patient had a positive stool antigen, deep shotgun sequencing of their stool failed to identify H. pylori DNA, making infection transmission unlikely. The other DLT was a C. difficile infection 6 days after the last dose of FMT, with prompt response to oral vancomycin. All FMT donors had been tested for C. difficile and were PCR-negative, as part of the mandatory eligibility criteria. Thus, this DLT was considered unrelated to FMT.

Clinical outcomes

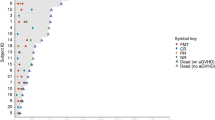

All survivors completed follow-up to day +180, with no missing data. Figure 1 shows subject-level characteristics and clinical outcomes. Day +180 non-relapse mortality was 0%. Three (15%) patients relapsed. One was a patient with multiple myeloma undergoing the alloHCT part of a tandem auto-allo transplant who relapsed at day +53, with rapid progression and death at day +91. The other 2 patients had high-risk acute myeloid leukemia; one relapsed at day +56 and the other one relapsed at day +119 (second alloHCT); both patients survived past day +180. No other deaths occurred, yielding a day +180 overall survival of 95%.

Baseline characteristics from left to right include age, sex, disease, donor type, conditioning regimen, GVHD prophylaxis, and graft source. All survivors had 180 days of follow up after HCT. aGVHD acute graft-versus-host disease, ALL acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML acute myeloid leukemia, BM bone marrow, BPDCN blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, CB cord blood, CNI calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus or cyclosporine), Cy cyclophosphamide, F female, Flu fludarabine, FMT fecal microbiota transplantation, Haplo HLA-haploidentical related donor, LD low-dose, M male, MM multiple myeloma, MDS myelodysplastic syndromes, Mel melphalan, MMF mycophenolate mofetil, MPN myeloproliferative neoplasms, MSD HLA-matched sibling donor, MTX methotrexate, MUD 9/10 or 10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donor, NHL non-Hodgkin lymphoma, PB peripheral blood, PTCy post-transplantation cyclophosphamide (50 mg/kg on days +3 and +4), SAA severe aplastic anemia, Siro sirolimus, TBI total body irradiation, Treo treosulfan, TTP thiotepa.

Grade III–IV aGVHD occurred in 3 (15%) patients: two with isolated stage 3 skin aGVHD (15 and 16 days after starting FMT) and one with isolated stage 3 lower gut late-acute GVHD (130 days after starting FMT). All 3 patients had received FMT from donor 1. Three additional patients developed grade II aGVHD (2 with donor 2; 1 with donor 3), for an overall grade II–IV aGVHD incidence of 30%: one stage 2 skin aGVHD, and two lower gut aGVHD (one stage 1 and one late-acute stage 2). The stage 2 lower gut aGVHD occurred in the setting of an early taper of GVHD prophylactic medications due to a decline in donor chimerism. All cases of aGVHD were steroid-responsive, except the patient with stage 3 lower gut late-acute GVHD. This case was complicated by a delay in diagnosis and treatment in a suburban community setting. Profound deconditioning and anasarca along with large-volume diarrhea and CMV viremia led to prolonged hospitalization after transfer to our center. GVHD responded to 2 additional lines of therapy (ruxolitinib and extracorporeal photopheresis) and the patient was discharged to a rehabilitation facility.

Effect of FMT on microbiota diversity and composition

A total of 80 samples including 3 FMT donor samples and 77 patient samples were analyzed. These samples contained a median of 21,463,396 (range 13,567,385–44,146,652) post-filtering high-quality microbial reads mapped to 1128 species belonging to 613 genera. The distribution of the 15 most abundant genera among samples is shown in Fig. 2a. The most prominent genus-level difference between the donors was the markedly higher abundance of Bifidobacterium in donor 3 (16.3%) compared to donors 1 and 2 (both <1%). In hierarchical clustering of donor samples (Fig. 2b), donor 1 was distinctly different from donors 2 and 3 who clustered together. In contrast to donors 2 and 3, donor 1 was enriched in Ruminococcus bicirculans, Blautia wexlerae, Gemmiger formicilis, Wujia chipingensis, and Phocaeicola vulgatus, while Eubacterium rectale, Roseburia faecis, Coprococcus eutactus, Ruminococcus bromii, and Lachnospira pectinoschiza were less abundant in donor 1 compared to donors 2 and 3. The characteristic feature of donor 3 was a higher abundance of Bifidobacterium adolescentis, B. bifidum, Dialister invisus, and Ruminococcus callidus. Donor 2 had no appreciable characteristic feature other than a higher abundance of an unclassified species (GGB3345_SGB4425). Donors 1 and 3 had highly different microbiota compositions, with abundant species in one donor being rare in the other, and vice versa. Despite these compositional differences, microbiota diversity was similar (Shannon index = 4.0) in all 3 donors (Fig. 2c).

a Genus-level microbiota composition, with the 15 most abundant genera among all samples shown. Less abundant genera are grouped together. The asterisks indicate samples from patients who received FMT. b Species-level donor microbiota heatmap visualizing the results of unsupervised hierarchical clustering using CLR-transformed abundances and a ward.D function. Each column is a sample and each row is a species. The blue-red gradient shows species abundances scaled row-wise. c Alpha diversity as measured by Shannon’s index. Each box shows the median (horizontal middle line) and interquartile range at the corresponding timepoint. Whisker lines indicate non-outlier maximum and minimum values. A small jitter is included for better visualization. The P value is from a Kruskal–Wallis test (P = 2.1 × 10−8). Bonferroni-corrected P values in pairwise comparisons: P = 0.01 (donor vs. baseline), P = 0.003 (donor vs. pre-FMT), P = 0.04 (donor vs. post-FMT), 0.004 (baseline vs. pre-FMT), 0.0003 (baseline vs. post-FMT), and 2.1 × 10−8 (pre-FMT vs. post-FMT). n = 3 (donor), n = 32 (baseline), n = 28 (pre-FMT), and n = 17 (post-FMT). d Species-level donor and patient microbiota heatmap. Methods and notations are similar to (b). Colored circles indicate post-FMT samples. e Differential abundance analysis using general linear model-based Microbiome Multivariable Association with Linear Models (MaAsLin2), comparing the two sample clusters in (d). Each circle in the volcano plot is a species; those with FDR-adjusted P value (q value) <0.05 are shown in red and those with a coefficient >2.5 or <−2.5 are labelled. The significance threshold is shown as a dashed blue line. Circles above this line represent statistically significant species. Species to the right/left of zero along the x axis were enriched in the cluster on the right/left of the heatmap in (d). f Beta diversity and ordination visualized by principal coordinate analysis. Aitchison’s distance was used to quantify the overall compositional difference between samples. The first two principal coordinates are shown. Numbers in parentheses indicate percent microbiota variation explained by the corresponding axis. Each symbol represents a sample. The centroid of each cluster is shown by a larger symbol. Confidence ellipses are shown. CLR centered log-ratio, FMT fecal microbiota transplantation, PC principal coordinate.

Baseline diversity of patient microbiota was lower than FMT donors, consistent with prior studies comparing baseline pre-HCT diversity to healthy adults23. Similar to our previous trial17, microbiota diversity declined further during transplantation until the pre-FMT timepoint. After FMT, microbiota diversity increased, exceeding even baseline levels and approaching donor microbiota diversity (Fig. 2c). We utilized unsupervised, species-level, hierarchical clustering to explore similarities across all samples analyzed, including donor and recipient samples (Fig. 2d). Interestingly, we found that one naturally occurring cluster (left) encompassed all donor samples and most post-FMT samples (11/17; 65%), but only a small number of baseline (5/32; 16%) and pre-FMT (2/28; 7%) samples. This cluster likely represents samples that are “healthier” or more normal, given that the donor samples are all included. Co-clustering of donor and most post-FMT samples suggested a marked compositional shift toward donor after FMT. In differential abundance analysis (Fig. 2e), marked differences in many species were observed between the two clusters. The cluster on the left was highly enriched in Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (among other Faecalibacterium species), Dorea longicatena, Eubacterium rectale, and several species of Blautia. The cluster on the right was enriched in fewer species including Blautia producta and Blautia caecimuris. In principal coordinates analysis (Fig. 2f), the first axis separated patient samples based on timepoint. Baseline samples were the closest to donor samples. Between baseline and pre-FMT timepoints, microbiota shifted away from donor compositions. This was reversed with FMT, indicating a partial recovery of the commensal microbiota.

Donor dependence of FMT effects on the microbiota

Pre-FMT microbiota alpha diversity was strongly and negatively associated with engraftment rate (Fig. 3a), indicating a patient effect. In contrast, the compositional distance between pre-FMT patient microbiota and donor microbiota did not correlate with engraftment rate (Spearman’s rho = −0.19, P = 0.47). Species-level mean engraftment rate—the primary endpoint of the run-in phase—was 67% for donor 3, 60% for donor 2, and 54% for donor 1 (Fig. 3b). Median (interquartile range) values were 66% (56–81%), 72% (41–75%), and 57% (45–66%), respectively. To remove patient effect and make a potential donor effect easier to demonstrate, we adjusted engraftment rates for pre-FMT alpha diversity using a linear regression model which also included FMT donor/recipient sex concordance as a covariate given differences in the gut microbiota between men and women24 and possible effects of sex match/mismatch on FMT outcomes25. As detailed in Table 2 and visualized in Fig. 3c, donor 3 was the clear best in terms of engraftment (donor 3 vs. donor 1: P = 0.02; donor 3 vs. donor 2: P = 0.03). Interestingly, there was a trend for better engraftment in sex-matched FMT (P = 0.08).

a Negative correlation between donor microbiota engraftment and pre-FMT alpha diversity as measured by Shannon’s index. The correlation coefficient and P value (0.0001) are from a Spearman’s correlation test. b Donor microbiota engraftment at the species level, defined as the percentage of post-FMT species that were shared exclusively between the post-FMT sample and FMT product. These species were absent in pre-FMT and baseline patient samples. The P value is from a Kruskal–Wallis test. Data from 5, 6, and 6 patients treated with FMT from donors 1, 2, and 3 are included, respectively. c Donor microbiota engraftment at the species level, adjusted for pre-FMT microbiota diversity and FMT donor/patient sex match status. The results are from a linear regression model, where engraftment was the outcome variable, donor number was the main predictor, and pre-FMT microbiota diversity (measured by Shannon’s index) and FMT donor/recipient sex concordance (yes vs. no) were the covariates. Donor-specific regression residuals are plotted. The P values are from the regression model; they are two-sided, correspond to the donor term (comparing donor 3 to donors 1 and 2), and indicate the unadjusted significance of pairwise comparisons between donors. Data from 5, 6, and 6 patients treated with FMT from donors 1, 2, and 3 are included, respectively. d Post-FMT microbiota alpha diversity as measured by Shannon’s index. The P value is from a Kruskal–Wallis test. Data from 5, 6, and 6 patients treated with FMT from donors 1, 2, and 3 are included, respectively. e Relative reduction in patient-donor Aitchison’s distance from pre- to post-FMT. The P value is from a Kruskal–Wallis test. Data from 5, 6, and 6 patients treated with FMT from donors 1, 2, and 3 are included, respectively. f Donor microbiota engraftment at the strain level, defined as the percentage of post-FMT strains that were shared exclusively between the post-FMT sample and FMT product. These strains were absent in pre-FMT and baseline patient samples. The P value is from a Kruskal–Wallis test. Data from 5, 6, and 6 patients treated with FMT from donors 1, 2, and 3 are included, respectively. g Negative correlation between donor microbiota engraftment and compositional similarity between post-FMT and donor microbiota. The correlation coefficient and P value are from a Spearman’s correlation test. h Per-species strain-level donor microbiota engraftment. Species present in at least 25% of post-FMT samples were included. Species that were not present in the donor used for the patient were not included because engraftment could not occur (by definition). The results for all species irrespective of the 25% prevalence threshold are provided in Supplementary Data 1. Numbers in the right column (“Total”) indicate how many times the species was detected in post-FMT samples. Each box in (b–f) shows the median (middle line) and interquartile range. Black circles indicate means. Whisker lines indicate non-outlier maximum and minimum values. A small jitter is included for better visualization. Patient IDs are shown in (a–g) and can be linked to their corresponding donors using data in Fig. 1. FMT fecal microbiota transplantation.

There was a trend for higher post-FMT microbiota alpha diversity in patients treated with donor 3 (Fig. 3d) and a trend for a greater relative reduction in patient-donor compositional dissimilarity from pre- to post-FMT (indicating the magnitude of compositional shift toward donor) with donor 3 (Fig. 3e). Although neither trend approached statistical significance, both were consistent with our main finding favoring donor 3. The second trend is also consistent with Fig. 2d, where the donor cluster (left) included 5/6 (83%) evaluable post-FMT samples using donor 3, compared to 4/6 (67%) samples using donor 2 and 2/5 (40%) samples using donor 1.

Mean engraftment rate at the strain level was ~50% for all donors (donor 1: 48%; donor 2: 53%; donor 3: 50%; Fig. 3f). Median (interquartile range) values were 53% (35–62%), 60% (25–79%), and 47% (43–63%), respectively. Engraftment with FMT from donor 2 was the most heterogeneous, with 2 patients experiencing poor engraftment. The extent of engraftment was a strong determinant of compositional similarity between post-FMT and donor microbiota (Fig. 3g). Strain-level donor microbiota engraftment rate varied among species. Among species present in at least 25% of post-FMT samples (Fig. 3h), engraftment was 100% for Ruminococcus bromii; 50–100% for an Oscillospiraceae species, Eubacterium rectale, and Collinsella aerofaciens; and 25–50% for Mediterraneibacter faecis, Dorea longicatena, Coprococcus comes, Blautia massiliensis, Bifidobacterium longum, Alistipes putredinis, and Gemmiger formicilis. When considering all species in post-FMT samples (Supplementary Data 1), irrespective of their prevalence, engraftment was 100% for 41 species and ≥50% for 67 species. Six species (Blautia obeum, Blautia faecis, Phocaeicola vulgatus, Dialister invisus, Candidatus Cibionibacter quicibialis, and Faecalibacterium sp. HTFF) had no engraftment despite a relative abundance of >1% in at least 1 donor.

Donor dependence of FMT effects on aGVHD risk

Since all 3 cases of severe aGVHD occurred in patients treated with FMT from donor 1, we performed exploratory analyses to examine whether these patients had a distinct post-FMT microbiota signature that could be uniquely attributed to donor 1. Such a finding would suggest a clinically relevant donor effect, thereby supporting the importance of donor choice based on their precisely characterized microbiota composition, an approach not used in FMT trials to date. Despite our small sample size (3 patients with and 14 without grade III–IV aGVHD), a clustering of post-FMT samples based on subsequent development of grade III–IV aGVHD was apparent (Fig. 4a). These samples clustered also based on the FMT donor, indicating significant donor-specific modulation of the microbiota (Fig. 4b). Notably, while post-FMT samples pertaining to donors 1 and 2 showed some overlap, those pertaining to donor 3 clustered distinctly separately, suggesting a unique pattern of microbiota modulation by donor 3. In differential abundance analysis, 4 post-FMT species were significantly more abundant in patients who later developed grade III–IV aGVHD vs. those who did not (Fig. 4c, d): SGB9342 (a Proteobacteria species), SGB5183 (a Lachnospiraceae species), SGB14179 (an Oscillospiraceae species), and Prevotella disiens. SGB9342 and SGB14179 were present in donor 1 (relative abundances 1.1% and 0.01%, respectively) and absent in donors 2 and 3. In strain-level analysis using the entire database, two strains of SGB9342 were identified. The first strain was present exclusively in donor 1 and post-FMT samples from 4 of the 5 patients treated with FMT from this donor. The second strain was present only in the baseline sample from one patient and no donors. Strain-level analysis could not be performed for SGB14179 due to insufficient resolution. SGB5183 and Prevotella disiens were absent from all donors. Therefore, one strain of SGB9342 from donor 1 engrafted in most patients receiving FMT from this donor, reached >1% abundance in post-FMT samples, and correlated with severe aGVHD.

a Principal coordinate analysis using Aitchison’s distance, comparing post-FMT samples between patients developing vs. not developing grade III–IV aGVHD. The first two principal coordinates (PC1 and PC2) are shown. Numbers in parentheses indicate percent variation explained by the corresponding axis. Each symbol represents a sample. The centroid of each cluster is shown by a larger symbol. Confidence ellipses are shown. The P value is from an adonis test with 999 permutations. b Same analysis as in (a), this time comparing post-FMT samples from different donors. Overall P = 0.00002. P values for all pairwise comparisons were <0.05. c Volcano plot showing post-FMT species associated with subsequent grade III–IV aGVHD in differential abundance analysis using general linear model-based Microbiome Multivariable Association with Linear Models (MaAsLin2). Each circle is a species; those with FDR-adjusted P value (q value) <0.10 are shown as larger circles in red. The significance threshold is shown as a dashed blue line. Circles above this line represent statistically significant species. All species significant at this threshold were also significant at q < 0.05. All significant species are to the right of zero along the x axis, indicating their association with grade III–IV aGVHD. d Relative abundance (y axis) of significant species in (c) in post-FMT samples compared between patients developing vs. not developing grade III–IV aGVHD. Each box shows the median (horizontal middle line) and interquartile range. Whisker lines indicate non-outlier maximum and minimum values. A small horizontal jitter is included for better visualization. Adjusted P values (q values) are from (c) and two-sided. Data from 3 and 14 patients with and without grade III–IV aGVHD are included, respectively. aGVHD acute graft-versus-host disease, FMT fecal microbiota transplantation, PC principal coordinate.

Donor choice for the randomized phase

With a 67% species-level mean engraftment rate and 50% strain-level mean engraftment rate, donor 3 was the overall best donor, yielding significantly higher engraftment rates than donors 1 and 2 in post-hoc multivariable analysis. In addition, donor 3 was associated with the smallest number of critical clinical events (two events in 8 patients with donor 3; three events in 6 patients with donor 2; four events in 6 patients with donor 1; Fig. 1). Only 1 of the 8 patients treated with donor 3 developed grade II aGVHD and none developed grade III–IV aGVHD. This compared favorably to donor 2 (2/6 patients developed grade II aGVHD and none developed grade III–IV aGVHD) and donor 1 (3/6 patients developed grade III–IV aGVHD). Collectively, donor 3 emerged as the optimal donor and was selected for the randomized phase.

Discussion

In this pre-planned analysis performed at the conclusion of the run-in phase, we demonstrated that oral encapsulated FMT, at a total dose more than 4 times higher than in our previous trial, was feasible and safe as an adjunct to standard GVHD prophylaxis in alloHCT patients. No major toxicity occurred, supporting the safety of healthy donor FMT using current donor/stool screening criteria even in the most immunocompromised patients. We achieved 54–67% mean species-level engraftment rate and ~50% mean strain-level engraftment rate. FMT resulted in a remarkable restoration of microbiota diversity and shift toward donor compositions. The latter confirmed the recovery of diversity to be due to FMT rather than a mere reflection of spontaneous recovery over time with antibiotic de-escalation and improvements in oral intake. Both the recovery of diversity and compositional shift toward donor were greater in the current trial compared to our previous trial.

We achieved the best engraftment outcome with donor 3, with 67% mean engraftment rate at the species level and 50% at the strain level, reaching statistical significance for superiority over the other donors in post-hoc multivariable analysis. Multiple other microbiota and clinical indices also favored donor 3 as the optimal donor. The importance of donor choice (a.k.a the “super donor” phenomenon) for microbiota engraftment and clinical response to FMT remains controversial in the non-transplant setting and completely unknown in alloHCT recipients. Two large meta-analyses of FMT trials in different disease settings indicated a donor effect, particularly in patients treated with antibiotics21,22. Although our patients did not receive a planned, uniform pre-FMT antibiotic conditioning, all were exposed to antibiotics during the early post-HCT period. Therefore, the existence of a donor effect in our patients is plausible and supported by data. In addition, given the differences in engraftment potential of different species as demonstrated herein, in our previous trial17, and in other studies21,22,26, taxonomic composition of the donor microbiota is likely important for engraftment. One meta-analysis showed that strains from relatively abundant species were more likely to engraft while those from predicted oral, oxygen-tolerant, and gram-positive species were less likely to engraft21. Donor microbiota diversity, another predictor of engraftment in previous studies21, was not a determinant of donor effect in our trial because it was similar in the 3 donors. Consistent with previous analyses21, pre-FMT microbiota diversity was negatively associated with engraftment, with less diverse pre-FMT microbiota promoting donor microbiota engraftment. Adjustment of engraftment for pre-FMT microbiota diversity (patient effect) and FMT donor/recipient sex match status made donor 3 distinctly better than donors 1 and 2.

The most remarkable difference in microbiota composition among the 3 donors was the obligate anaerobic genus Bifidobacterium and its species B. adolescentis, both of which were highly enriched in donor 3. B. adolescentis was present at a high abundance in donor 3 (11.6%) and a low abundance in donor 2 (0.05%), but absent in donor 1, all pre-FMT samples, and post-FMT samples from donors 1 and 2. In contrast, this species was present in post-FMT samples from 3 of the patients treated with donor 3, with relative abundances of 9.7%, 1.4%, and 0.4%. Strain-level analysis confirmed B. adolescentis in these patients to be donor-derived. B. adolescentis is evolutionarily adapted to fermenting plant-derived glycans such as resistant starch. The major metabolites produced by B. adolescentis are short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) acetate and lactate27. By cross-feeding butyrogenic bacteria, B. adolescentis increases fecal butyrate28,29,30. This species is also important for microbiota recovery after antibiotic treatment31. In healthy adults, the abundance of B. adolescentis in the gut microbiota is associated with less tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in response to stimulation, suggesting an anti-inflammatory effect32. Anti-inflammatory effects and cross-feeding of butyrogenic bacteria by B. adolescentis in donor 3 may have created favorable microbial community compositions with tolerogenic potential in post-FMT samples, leading to better clinical outcomes. In a previous FMT trial for patients with irritable bowel syndrome, the most significant difference between effective donors (i.e., those whose corresponding patients had a clinical response) and ineffective donors was the abundance of Bifidobacterium, with effective donors having a significantly higher abundance of this genus33.

Donor 1 was associated with the worst microbiota and clinical outcomes. In particular, the occurrence of all 3 cases of severe aGVHD in patients treated with FMT from donor 1 raised the hypothesis that unique features of this donor’s microbiota contributed to GVHD. In exploratory analysis we searched for species that would be the most likely culprits if FMT from donor 1 increased GVHD risk. This analysis identified one strain of SGB9342 (an unclassified Proteobacteria species) present exclusively in donor 1 which engrafted and expanded in most patients treated with this donor and correlated with severe aGVHD. An additional finding indirectly supporting the inferiority of donor 1 came from hierarchical clustering, where donors 2 and 3 formed one cluster while donor 1 formed its own cluster. This observation indicated the presence of unique features in this donor’s microbiota. Compared to donors 2 and 3, donor 1 had a substantially lower abundance of Ruminococcus bromii and Eubacterium rectale, two butyrogenic obligate anaerobic commensals of the gut with 100% and ~65% engraftment rate in our trial, respectively.

A key determinant of the fate of donor microbiota once they reach the recipient’s gut is their intrinsic engraftment potential. Using strain-level engraftment, we found that several species in post-FMT samples were derived exclusively or largely from donor strains, indicating strong and reliable engraftment. These species include some of the major SCFA-producing, obligate anaerobic commensals of the gut (e.g., Eubacterium rectale, Ruminococcus bromii) considered to be protective against aGVHD5,10. In contrast, several other important commensal species (e.g., Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Blautia wexlerae) engrafted weakly. This species specificity of engraftment potential is consistent with prior studies21,22. As an example, both in our previous trial and other studies, the Actinobacteria phylum (including various Bifidobacterium species) was among taxa with the highest engraftment rates17,22. Of the 4 Bifidobacterium species with sufficient resolution to evaluate strain-level engraftment in the present study, 3 (B. adolescentis, B. bifidum, and B. catenulatum) had 100% donor engraftment and the 4th one (B. longum) had 38% engraftment). Early after alloHCT, enteral nutrition is often compromised, and some degree of intestinal barrier damage occurs due to the conditioning regimen. These and other micro-ecosystem factors in the colon may influence microbiota engraftment and need to be studied in future work.

Limitations of the study included the small sample size in each cohort, precluding definitive hypothesis testing for any given endpoint. As a result, the totality of data including microbiota indices and clinical outcomes was used to select the best donor. Heterogeneity in transplant platforms, especially conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis regimens was probably a contributor to the differences observed in microbiota and clinical outcomes in patients treated with different donors. Although a much larger number of patients per donor would have allowed formal hypothesis testing while adjusting for several potential confounders, practical considerations (e.g., a priori need for storage of many more capsules from each donor for both run-in and randomized phases) were prohibitive. Also, the alternative strategy of using a homogenous patient population and transplant platform, although beneficial for the analysis of the run-in phase, would have limited applicability to the randomized phase where patient heterogeneity is desirable. Nonetheless, the consistent patterns observed in pre-planned univariate analysis supported by statistical significance in post-hoc multivariable analysis allowed us to identify the optimal donor for the randomized phase.

In conclusion, the run-in phase of our randomized placebo-controlled FMT trial to prevent severe aGVHD met its endpoints. A higher dose of FMT compared to our previous trial was feasible and safe and improved microbiota indices more effectively. Engraftment reached 100% for some of the key commensal species considered beneficial for gut health in general and protective against GVHD. Microbiota and clinical outcomes correlated and together identified a clear “winner” among the 3 donors. While the best approach to donor selection remains unknown, our findings suggest a donor effect and feasibility of evidence-based donor selection. The optimal donor is currently being used in the ongoing randomized phase of the trial to examine whether FMT reduces the risk of severe aGVHD.

Methods

Trial oversight

The trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT06026371) was conducted at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center (FHCC)/University of Washington (Seattle, WA) and the study protocol was approved by the institutional review board (protocol #RG1123691; FDA IND #29935). Donor screening, stool testing for infectious agents, and product manufacturing (Compound MTP101-C; FDA IND #15071) were conducted at the University of Minnesota using Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) protocols, as described in our previous trial17. The FHCC Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC) and an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) monitored the conduct of the study. Enrollment in the run-in phase started on November 1, 2023 and reached target accrual on February 14, 2024. After successful completion of the run-in phase, the randomized phase was initiated on June 12, 2024.

Study design

The study was designed as a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial in two consecutive phases. An initial single-arm run-in phase identified the best of the 3 FMT donors, defined as the one yielding the highest mean microbiota engraftment rate among recipients. Same-dose FMT from each donor was used for 4–8 patients. Donors were chosen sequentially. In the subsequent, ongoing randomized phase, patients are randomly assigned at a 1:1 ratio to FMT from the best donor from the run-in phase vs. placebo. No microbiota-specific criteria were used to select the 3 donors in the run-in phase. These donors were selected based on product availability at the time of initiation of the run-in phase and accounting for the possibility of being chosen also for the randomized phase. None of the donors consumed probiotics or other medications. Importantly, none of the donors had any antibiotic exposure in the last 5 years before donation. Donor 1 was a 34-year-old woman with a body mass index (BMI) of 23.5, donor 2 was a 36-year-old man with a BMI of 24.9, and donor 3 was a 40-year-old woman with a BMI of 26.4.

Eligibility criteria for enrollment in the trial are the same for both phases. Key inclusion criteria are: (i) age ≥18 y, (ii) GVHD prophylaxis using a calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) plus methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) (regimen 1), cyclosporine plus sirolimus plus MMF (regimen 2), or post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy) plus a CNI (with or without MMF or sirolimus) (regimen 3), and (iii) HLA-matched sibling donor, 9–10/10 HLA-matched unrelated donor, HLA-haploidentical donor, or umbilical cord blood. Key exclusion criteria are severe food allergy and a history of chronic aspiration. No eligibility criteria are used for the underlying disease, conditioning regimen, or graft source. Patients provide written informed consent before day 0 (day of HCT), preferably before transplant conditioning. The window for starting treatment opens at the time of neutrophil recovery to >0.5 × 109/L from post-transplant nadir and 2 days after discontinuation of antibacterial antibiotics (except those used for Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis), whichever occurs later. The window remains open until 10 days after the last dose of antibacterial antibiotics or day 45 post-transplant, whichever occurs first. Treatment is initiated within this window when all transplant-associated toxicities (except anemia and thrombocytopenia) are resolved to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE v.5) grade 2 or lower and patients are able to swallow capsules. Patients who develop grade II–IV aGVHD before starting study treatment do not receive study treatment. The protocol does not require or recommend any changes to standard prophylactic or therapeutic regimens for infections or GVHD.

Treatment consists of 3 FMT (vs. placebo in the randomized phase) capsules containing lyophilized purified microbiota, taken by mouth daily for 7 consecutive days. The microbiota dose per FMT capsule is similar to our previous trial (1–2 × 1011 bacteria), with 91%, 84%, and 81% viability for donors 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Treatment is discontinued if any of the following occurs during the week of study treatment: microbiologically documented bloodstream or gastrointestinal infections, antibacterial antibiotic exposure (except for Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis), grade III–IV aGVHD, CTCAE v.5 grade 3 or higher gastrointestinal toxicity, neutrophil decline to <0.5 × 109/L, or inability to swallow capsules. Three stool samples are collected from each patient in sterile, 95% ethanol-filled tubes and stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction. These samples are collected at baseline (as soon as possible after consent), pre-FMT/placebo (during the study treatment initiation window and before treatment initiation), and post-FMT/placebo (4 ± 1 weeks after the last dose of study treatment).

In the run-in phase, patients who did not meet treatment criteria within the protocol-defined window, did not provide pre- and post-FMT stool samples to permit microbiota engraftment analysis, or were exposed to antibacterial antibiotics (except those used for Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis) between the start of FMT and the post-FMT sample were considered unevaluable and were replaced. Enrollment continued until we had at least 4 evaluable patients for each donor. No new patients were enrolled thereafter, but patients who had already been enrolled received study treatment if eligible and were included in the analysis.

Adverse event (AE) monitoring in both phases continues until 30 days after the end of study treatment and includes 4 phone calls on days 1, 4, and 7 of treatment, and 7 days after the end of treatment. Dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) is defined as any of the following events occurring between dose 1 of study treatment and day 30 after the last dose: (i) CTCAE v.5 grade 3 or higher gastrointestinal AEs, (ii) anaphylaxis, (iii) non-relapse mortality, (iv) bacteremia other than those caused by Staphylococcus epidermidis, Streptococcus mitis, and Streptococcus parasanguinis, (iv) microbiologically documented gastrointestinal infection, and (v) multi-drug resistant infection (any site).

Microbiota profiling and bioinformatic analysis

DNA was extracted from patient samples and the FMT product from all donors using the ZymoBIOMICS®-96 MagBead DNA Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). Sequencing libraries were prepared using the Illumina® DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol and with unique dual-index 10 bp barcodes with Nextera® adapters. All libraries were pooled in equal abundance and the final pool was quantified using qPCR and TapeStation® (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The final library was sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 using a S2-300 flow cell and a PE150 configuration. The target sequencing depth was 20 M reads per sample.

Raw paired-end metagenomic sequence reads were quality-processed using the integrated pipeline provided in KneadData v.0.12.0. This sequence-level procedure included two main steps: (i) removal of reads mapped to the human reference genome GRCh37 (hg19) using Bowtie2 v.2.4.534 and (ii) removal of adapter sequences and low-quality reads using Trimmomatic v.0.3935 with default settings. Output files consisting of surviving paired and orphan reads were concatenated and used as input to MetaPhlAn4. MetaPhlAn436 with default parameters was used for species-level taxonomic assignment. MetaPhlAn uses a set of species-level genome bins (SGBs)37 as primary taxonomic units and accurately profiles their presence and abundance in metagenomes. The latest version (version 4) of MetaPhlAn uses a database containing ~5.1 million unique clade-specific marker genes for 21,978 existing SGBs and 4992 yet-to-be-characterized SGBs (defined solely based on metagenome-assembled genomes).

Engraftment analysis was performed at 2 taxonomic levels: species (primary) and strain (secondary). In both methods, we examined each post-FMT sample and compared it to the pre-FMT and baseline samples from the same patient as well as the FMT product from the patient’s donor (i.e., donor sample). Patient-derived species/strains were identified as those shared between the patient’s post-FMT and pre-FMT (or baseline) samples but absent in the donor sample. Donor-derived species/strains were identified as those shared between the patient’s post-FMT and donor samples but absent in the patient’s baseline and pre-FMT samples. Engraftment was defined as Spd/(Spp + Spd) at the species level and Std/(Stp + Std) at the strain level, where Sp and St represent species and strains, and d and p represent donor and patient, respectively. Each term represents the number of donor- or patient-derived species/strains. Species/strains with an unknown origin (i.e., new species/strains absent in donor, patient’s baseline, and patient’s pre-FMT samples) or co-existing between donor and either patient’s baseline or pre-FMT samples were not included in these calculations. For species-level engraftment analysis, we used taxonomic tables generated by MetaPhlAn. For strain-level engraftment analysis, we used SameStr26 which leverages MetaPhlAn’s clade-specific markers to resolve within-species phylogenetic sequence variations. First, MetaPhlAn marker alignments were converted to single nucleotide variant profiles. These profiles were then filtered, merged, and compared between samples based on the maximum variant profile similarity (MVS) to detect strains that were shared between samples. Shared strains were called if species alignments between samples overlapped by ≥5 kb and with an MVS of ≥99.9%. We used two methods for engraftment analysis because of their complementarity: Species-level analysis uses all available data, whereas SameStr is limited to the detection of shared or coexisting strains that make up ≥0.25% of all genomes in the sample or ≥0.25% species relative abundance in case of single-strain species26. In contrast, strain-level analysis determines the origin of a given taxon more accurately than species-level analysis.

Within-sample (alpha) and between-sample (beta) diversity were determined from species-level data in vegan v.2.6.4 by Shannon’s index38 and Aitchison’s distance39, respectively. Aitchison’s distance respects the compositionality of microbiota data and is defined as the Euclidean distance applied to centered log-ratio (CLR) transformed abundances. Ordination was visualized in principal coordinates analysis (i.e., principal components analysis applied to Aitchison distances) using factoextra v.1.0.7. After removing the species occurring in only 1 sample, Microbiome Multivariable Association with Linear Models (MaAsLin2) was used to identify post-FMT species associated with severe aGVHD40. P values were corrected for multiple testing (false discovery rate; FDR method).

Statistical analysis

R v.4.2.0 was used for all analyses. The primary endpoint of the run-in phase was donor microbiota engraftment. The primary endpoint of the randomized phase is grade III–IV aGVHD, defined as scale C-D aGVHD per the International Blood and Marrow Transplantation Research (IBMTR) criteria41, at 6 months post-HCT. Secondary endpoints include grade II–IV (IBMTR scale B–D) aGVHD, non-relapse mortality, and Clostridioides difficile infection at 6 months post-HCT, and chronic GVHD at 1 year post-HCT. In the run-in phase, all patients who received at least one dose of FMT were included in the analysis of clinical outcomes. Of these patients, those who provided both pre- and post-FMT samples and were not exposed to antibacterial antibiotics between the first dose of FMT and the post-FMT sample were included in engraftment analysis.

Power calculation was not performed for the run-in phase. While engraftment was the main criterion used to choose the best donor, it was not the only one. This was because other than a post-hoc analysis of our previous trial, there is currently no evidence for engraftment to be a determinant of efficacy in preventing GVHD. As an example, choosing a donor with the greatest engraftment rate but whose recipients had poor clinical outcomes would not be justified. Therefore, additional criteria including patterns observed in alpha diversity and compositional shifts, findings from post-hoc exploratory analysis, and clinical outcomes were also considered. The totality of data was used to select the best donor.

Due to the small sample size, we focused on patterns and descriptive statistics more than P values; P values were provided for completeness. When statistical comparisons were performed, we used a Wilcoxon’s test to compare continuous variables between two groups and a Kruskal–Wallis test for multiple groups (with Bonferroni correction of P values in pairwise comparisons, when needed). In post-hoc exploratory analysis, we further delineated differences in engraftment rate among the 3 donors using a linear regression model, where donor number was the main predictor and engraftment (the outcome variable) was adjusted for pre-FMT microbiota diversity and FMT donor/recipient sex concordance as a binary variable. Donor-specific regression residuals were plotted to enable convenient visualization of findings from this analysis.

Data availability

The fastq sequencing files are available from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive, BioProject ID PRJNA1209112. De-identified subject-level clinical metadata are provided in Fig. 1 and can be linked to the sequencing files.

References

Zeiser, R. & Blazar, B. R. Acute graft-versus-host disease - biologic process, prevention, and therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 2167–2179 (2017).

Holtan, S. G. et al. Disease progression, treatments, hospitalization, and clinical outcomes in acute GVHD: a multicenter chart review. Bone Marrow Transplant. 57, 1581–1585 (2022).

Jenq, R. R. et al. Intestinal blautia is associated with reduced death from graft-versus-host disease. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 21, 1373–1383 (2015).

Golob, J. L. et al. Stool microbiota at neutrophil recovery is predictive for severe acute graft vs host disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 65, 1984–1991 (2017).

Burgos da Silva, M. et al. Preservation of fecal microbiome is associated with reduced severity of Graft-versus-Host Disease. Blood https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2021015352 (2022).

Stein-Thoeringer, C. K. et al. Lactose drives Enterococcus expansion to promote graft-versus-host disease. Science 366, 1143–1149 (2019).

Shono, Y. et al. Increased GVHD-related mortality with broad-spectrum antibiotic use after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in human patients and mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 339ra71 (2016).

Hayase, E. et al. Mucus-degrading Bacteroides link carbapenems to aggravated graft-versus-host disease. Cell 185, 3705–3719.e14 (2022).

Hayase, E. et al. Bacteroides ovatus alleviates dysbiotic microbiota-induced graft-versus-host disease. Cell Host Microbe 32, 1621–1636.e6 (2024).

Meedt, E. et al. Prolonged suppression of butyrate-producing bacteria is associated with acute gastrointestinal graft-vs-host disease and transplantation-related mortality after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 74, 614–621 (2022).

Yeh, A. C. et al. Microbiota dictate T cell clonal selection to augment graft-versus-host disease after stem cell transplantation. Immunity 57, 1648–1664.e9 (2024).

Koyama, M. et al. Intestinal microbiota controls graft-versus-host disease independent of donor-host genetic disparity. Immunity 56, 1876–1893.e8 (2023).

Koyama, M. et al. MHC class II antigen presentation by the intestinal epithelium initiates graft-versus-host disease and is influenced by the microbiota. Immunity 51, 885–898.e7 (2019).

van Lier, Y. F. et al. Donor fecal microbiota transplantation ameliorates intestinal graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, eaaz8926 (2020).

Kakihana, K. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for patients with steroid-resistant acute graft-versus-host disease of the gut. Blood 128, 2083–2088 (2016).

DeFilipp, Z. et al. Third-party fecal microbiota transplantation for high-risk treatment-naïve acute GVHD of the lower GI tract. Blood Adv. 8, 2074–2084 (2024).

Rashidi, A. et al. Randomized double-blind phase II trial of fecal microbiota transplantation versus placebo in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation and AML. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 5306–5319 (2023).

Rashidi, A. et al. Long- and short-term effects of fecal microbiota transplantation on antibiotic resistance genes: results from a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Gut Microbes 16, 2327442 (2024).

Rashidi, A. et al. Potential of fecal microbiota transplantation to prevent acute GVHD: analysis from a phase II trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 4920–4929 (2023).

Rashidi, A. et al. Multi-omics analysis of a fecal microbiota transplantation trial identifies novel aspects of acute GVHD pathogenesis. Cancer Res Commun 4, 1454–1466 (2024).

Podlesny, D. et al. Identification of clinical and ecological determinants of strain engraftment after fecal microbiota transplantation using metagenomics. Cell. Rep. Med. 3, 100711 (2022).

Ianiro, G. et al. Variability of strain engraftment and predictability of microbiome composition after fecal microbiota transplantation across different diseases. Nat. Med. 28, 1913–1923 (2022).

Peled, J. U. et al. Microbiota as predictor of mortality in allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 822–834 (2020).

Haro, C. et al. Intestinal Microbiota is influenced by gender and body mass index. PLoS ONE 11, e0154090 (2016).

Sehgal, K. et al. Sex-discordant fecal Microbiota transplantation for Clostridioides difficile may increase risk of postinfection irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 166, 704–706.e2 (2024).

Podlesny, D. et al. Metagenomic strain detection with SameStr: identification of a persisting core gut microbiota transferable by fecal transplantation. Microbiome 10, 53 (2022).

Duranti, S. et al. Evaluation of genetic diversity among strains of the human gut commensal Bifidobacterium adolescentis. Sci. Rep. 6, 23971 (2016).

Qian, X. et al. Bifidobacterium adolescentis is effective in relieving type 2 diabetes and may be related to its dominant core genome and gut Microbiota modulation capacity. Nutrients 14, 2479 (2022).

Belenguer, A. et al. Two routes of metabolic cross-feeding between Bifidobacterium adolescentis and butyrate-producing anaerobes from the human gut. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 3593–3599 (2006).

Duncan, S. H., Louis, P. & Flint, H. J. Lactate-utilizing bacteria, isolated from human feces, that produce butyrate as a major fermentation product. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 5810–5817 (2004).

Chng, K. R. et al. Metagenome-wide association analysis identifies microbial determinants of post-antibiotic ecological recovery in the gut. Nat Ecol Evol 4, 1256–1267 (2020).

Schirmer, M. et al. Linking the human gut microbiome to inflammatory cytokine production capacity. Cell 167, 1125–1136.e8 (2016).

Mizuno, S. et al. Bifidobacterium-rich fecal donor may be a positive predictor for successful fecal Microbiota transplantation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion 96, 29–38 (2017).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Blanco-Míguez, A. et al. Extending and improving metagenomic taxonomic profiling with uncharacterized species using MetaPhlAn 4. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 1633–1644 (2023).

Pasolli, E. et al. Extensive unexplored human microbiome diversity revealed by over 150,000 genomes from metagenomes spanning age, geography, and lifestyle. Cell 176, 649–662.e20 (2019).

Shannon, C. E. & Weaver, W. The mathematical theory of communication. Univ. Illinois Press, Urbana 11, 117 (1949).

Aitchison, J., Barceló-Vidal, C., Martín-Fernández, J. A., & Pawlowsky-Glah, V. Logratio analysis and compositional distance. Math. Geol. 32, 271–275 (2000).

Mallick, H. et al. Multivariable association discovery in population-scale meta-omics studies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1009442 (2021).

Rowlings, P. A. et al. IBMTR severity index for grading acute graft-versus-host disease: retrospective comparison with Glucksberg grade. Br. J. Haematol. 97, 855–864 (1997).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (Academic Clinical Trials award #ACT9016-24) to A.R. and the National Institutes of Health’s award P30 CA015704 to the Fred Hutch/University of Washington/Seattle Children’s Cancer Consortium. The funders did not have any role in data collection, interpretation, or reporting. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The manufacturing of the FMT product and placebo was supported by Achieving Cures Together, a nonprofit organization. We thank the following individuals and institutions: Microbial Interactions & Microbiome Center (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) and Clinical Research Specimen Processing (CRSP, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA) for providing storage space; Maradi Pho, Sharon Lopez, and Amanda Kabage for preparation and shipment of the investigational product; Jennifer C. Davies, Kathlyn H. Acosta, Tony Yang, and Amanda Kabage for regulatory support; and the study’s independent DSMB for supervision and advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R. was the principal investigator and responsible for overseeing all aspects of the trial. A.R., T.G., and A.K. designed the trial. S.R., M.E., and L.S. collected the clinical data. A.J.K. and A.K. provided the study product. T.G., S.M., D.P., and A.R. analyzed the data. L.S. helped with patient enrollment and follow up. S.R. and A.R. wrote the manuscript. G.R.H., S.J.L., D.P., and A.K. provided intellectual input to data interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.R. has received consulting fees from Seres Therapeutics (2023) related to the design of a clinical trial unrelated to the present study and using a different microbiome therapeutic. A.K. has intellectual property pertaining to extraction and cryopreservation of microbiota from stool for transplantation. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reddi, S., Senyshyn, L., Ebadi, M. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation to prevent acute graft-versus-host disease: pre-planned interim analysis of donor effect. Nat Commun 16, 1034 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56375-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56375-y

This article is cited by

-

Fecal microbiota transplantation in pigs: current status and future perspective

Animal Microbiome (2025)

-

The microbiome in graft-versus-host disease: a tale of two ecosystems

Journal of Translational Medicine (2025)

-

Microbiotoxicity: an under-recognised player in drug efficacy, toxicity, and health outcomes

npj Antimicrobials and Resistance (2025)

-

Microbiome dysbiosis and chemotherapy resistance in acute myeloid leukemia (AML)

npj Biofilms and Microbiomes (2025)

-

C. difficile Infection in Colorectal Cancer: Risk Determinants, Outcomes, and Evolving Management Approaches

Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer (2025)