Abstract

α-Ketoglutaric acid (KGA) and methanetriacetic acid (MTA) are important multi-functional carboxylic acids with versatile applications. However, their synthetic processes are still not green and efficient. Herein, we report a novel one-pot approach for sustainable synthesis of KGA and MTA from biomass-derived pyruvic and glyoxylic acids under mild conditions. KGA is synthesized via cross-aldol condensation of pyruvic and glyoxylic acids to 2-hydroxy-4-oxopentanedioic acid, followed by its sequential dehydration and hydrogenation on Pd/TiO2, affording a high yield of 85.4% on a molar basis of glyoxylic acid at 110 °C and 1.0 MPa H2. The synthesis of MTA involves cross-aldol condensation of KGA and glyoxylic acid to 3-(carboxymethyl)-2-hydroxy-4-oxopentanedioic acid and its subsequent hydrodeoxygenation on Pd/TiO2 and MoOx/TiO2 in a high yield of 86.2% at 200 °C and 2.0 MPa H2. This novel approach provides a rationale for the sustainable production of various multi-functional carboxylic acids that are still not easily available.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

α-Ketoglutaric acid (KGA) and methanetriacetic acid (MTA) are important carboxylic acids containing muti-functional groups. KGA is a versatile building block for the synthesis of various products, such as thermally stable coatings, biodegradable elastomers and thermo-responsive polymers1,2,3,4,5,6. It can also be directly used as a key component in dietary supplements, photo initiators and antidotes7,8,9,10,11,12. MTA provides a flexible tripodal scaffold for the synthesis of metal-organic frameworks, shape-shifting molecules and organometallic catalysts with C3-symmetry13,14,15,16,17. Meanwhile, MTA is a promising substitute for nitrilotriacetic acid as tripodal cross-linking ligands because of its stable skeleton18,19,20,21.

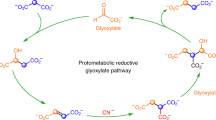

Currently, KGA is commercially produced via the microbial fermentation or enzymatic transformation, typically using glycerol, glucose and L-glutamic acid as substrates22,23,24,25,26. However, this method encounters problems with complicated operations, low yields, heavy pollution and high cost. KGA has also been synthesized by the reaction of diethyl succinate and diethyl oxalate involving their sequential condensation, decarboxylation and hydrolysis (Fig. 1a)27. However, this multi-step reaction displays poor carbon-atom economy with a carbon-based yield of as low as 28%, and employs large amounts of organic solvents (e.g., diethyl ether) and stoichiometric amounts of strong bases and acids (e.g., potassium tert-butoxide and hydrochloric acid). KGA can also be obtained from the oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl furfural using H2O2 as an oxidant on an Amberlyst-15 catalyst (Fig. 1a), but in a low carbon-based yield (26%) arising from its inevitable decarboxylation to succinic acid in the present of H2O228. Compared to KGA, the synthesis of MTA is more challenging because of its complex carbon skeleton29,30. One representative example is based on the condensation of citric and cyanoacetic acids, involving six sequential steps of esterification, decarboxylation, condensation, etc (Fig. 1a)17,29. Unsurprisingly, these tedious steps lead to a low carbon-based yield of 20%. Moreover, this reaction requires the use of large amounts of organic solvents (i.e., methanol and toluene), homogeneous catalyst (i.e., Pd(OAc)2) and toxic reactant (i.e., cyanoacetic acid). These problems with these methods limit their practical applications. Therefore, the development of alternative routes for the efficient and sustainable synthesis of KGA and MTA is highly desirable.

Herein, we report a novel approach for the one-pot synthesis of KGA and MTA from biomass-based pyruvic and glyoxylic acids in aqueous solutions. As depicted in Fig. 1b, KGA is synthesized via the cross-aldol condensation of pyruvic and glyoxylic acids to the 2-hydroxy-4-oxopentanedioic acid (C5) intermediate and its sequential dehydration and selective hydrogenation. The further condensation of KGA with glyoxylic acid leads to the production of MTA, involving the formation of the 3-(carboxymethyl)-2-hydroxy-4-oxopentanedioic acid (C7) intermediate and its sequential hydrodeoxygenation. In this approach, pyruvic and glyoxylic acids appear to be promising precursors, especially considering their structural similarity to the fragments of KGA and MTA cleaved at their C3-C4 bonds. Meanwhile, the two precursors can be sustainably produced from the biomass-based feedstocks31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. For example, the photocatalytic oxidation of lactic acid yielded pyruvic acid in a high selectivity of 94% at 90% conversion on Pt/CdS catalysts along with H2 production31. These features render it advantageous to synthesize KGA and MTA from the biomass-based pyruvic and glyoxylic acids, resembling the “click chemistry”, by their sequential cross-aldol condensation and hydrodeoxygenation. Under preliminarily optimized conditions, KGA and MTA can be obtained in high yields of 85.4% and 86.2%, respectively. Compared to the traditional routes for the synthesis of KGA and MTA, this approach provides a new strategy for producing high-valued multi-functional carboxylic acids with high yields and carbon-atom economies.

Results

Synthesis of α-ketoglutaric acid (KGA)

The first step for the KGA synthesis, as depicted in Fig. 1b, proceeded by the cross-aldol condensation of pyruvic and glyoxylic acids in the form of their sodium salts at near neutral pH (~8) in their aqueous solution (0.2 mol L−1). The glyoxylic acid conversion reached 17.8% after 40 min at 80 °C (Fig. 2a), and mainly formed the 2-hydroxy-4-oxopentanedioic acid (C5) intermediate (identified by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and mass spectrometry (MS) shown in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2) in 82.6% selectivity with its dehydration product, 4-oxopent-2-enedioic acid (C5-DH, Supplementary Fig. 2, in 7.7% selectivity). In addition to the two desired intermediates of KGA (i.e., C5 and C5-DH), a small amount of 3-(carboxy(hydroxy)methyl)-2-hydroxy-4-oxopentanedioic acid and 3-(carboxy(hydroxy)methyl)-4-oxopent-2-enedioic acid (Supplementary Fig. 3, abbreviated collectively as C5-GA with 8.9% selectivity) was formed by the further aldol condensation of C5 with glyoxylic acid. With increasing the glyoxylic acid conversion to 90.2% (Fig. 2a), the selectivity to C5 decreased monotonically to 53.5%, while the selectivities to C5-GA and C5-DH increased concurrently to 29.9% and 13.0%, respectively. This selectivity trend reflects the reaction pathways for the formation of C5 and its subsequent conversion to C5-GA and C5-DH (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 4).

a Evolution of conversions and selectivities for aldol condensation of pyruvic and glyoxylic acids (i.e., the first step of KGA synthesis) with reaction times. C5: 2-hydroxy-4-oxopentanedioic acid; C5-DH: 4-oxopent−2-enedioic acid; C5-GA: by-products derived from further condensation of C5 with glyoxylic acid. Reaction conditions: 2 mmol sodium pyruvate, 2 mmol sodium glyoxylate, 80 °C, 10 mL H2O. b Effect of molar ratios of pyruvic acid to glyoxylic acid on products selectivities in their aldol condensation reaction. Reaction conditions: 2 mmol sodium glyoxylate, 80 °C, 10 mL H2O, at nearly complete glyoxylic acid conversions obtained by varying reaction time. c Evolution of conversions and selectivities for sequential dehydration and hydrogenation reaction of C5 intermediate (i.e., the second step of KGA synthesis) with reaction times. Reaction conditions: 5 mL condensation reaction solution of pyruvic and glyoxylic acids with an initial ratio of 4:1 at nearly complete conversion of glyoxylic acid from the first step, 5 mL H2O, 30.0 mg Pd/TiO2 (2 wt% Pd), 110 °C, 1.0 MPa H2. d Proposed reaction pathways for KGA synthesis via two steps from pyruvic and glyoxylic acids (not including by-products of C5-GA and 2-hydroxypentanedioic acid, for clarity).

To suppress the further condensation of the C5 intermediate with glyoxylic acid to form the C5-GA by-products, the aldol condensation of pyruvic and glyoxylic acids at different molar ratios was examined. Within the kinetically-controlled regime (at ~30% glyoxylic acid conversion), when the ratios increased from 1:1 to 4:1 at 80 °C, the activities increased from 0.6 to 6.5 mmolglyoxylic acid h−1, and the total selectivities to the desired C5 and C5-DH products (i.e., the intermediates of KGA) increased from 88.8% to 96.3%, while the selectivities to C5-GA decreased from 10.6% to 2.8% (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results show that the formation of C5 is kinetically favorable, relative to its further condensation with glyoxylic acid, at the higher molar ratios of pyruvic acid to glyoxylic acid. Such favorable formation was more obvious at nearly complete conversion of glyoxylic acid. With increasing the ratios of pyruvic acid to glyoxylic acid from 1:1 to 4:1 (Fig. 2b), the selectivities to C5-GA decreased dramatically from 29.9% to 7.3%, concurrently with the increase in the total selectivities to C5 and C5-DH from 66.5% to 91.1%, corresponding to 90.1% yield of the desired products (83.1% C5 yield, 7.0% C5-DH yield). Moreover, the excess pyruvic acid can be well recycled for the new runs of condensation reaction, as described below.

Next, we explored the second step for the one-pot synthesis of KGA from the C5 intermediate via its sequential dehydration and hydrogenation on supported metal catalysts. Without separation and neutralization of the C5 intermediate, Pd/TiO2 (2 wt% Pd) was added directly into the reaction solution after the first step of the aldol condensation reaction, as discussed above, with an initial ratio of pyruvic acid to glyoxylic acid of 4:1 at nearly complete conversion of glyoxylic acid. The Pd particles possessed a mean diameter of 1.7 nm with a narrow size distribution on TiO2 (Supplementary Fig. 6a). As shown in Fig. 2c, the C5 conversion reached 19.7% after 10 min at 110 °C and 1.0 MPa H2, and the selectivities to KGA and C5-DH were 92.3% and 4.7%, respectively. A small amount of 2-hydroxypentanedioic acid (in 0.2% selectivity) was formed by the further hydrogenation of KGA. With increasing the C5 conversion to 100%, the selectivities to KGA kept nearly constant (90.5-94.8%). Meanwhile, the selectivities to C5-DH decreased to 0.1% while the selectivity to 2-hydroxypentanedioic acid slightly increased to 5.1%. Combining the first step, KGA was obtained in a high overall yield of 85.4% on a molar basis of glyoxylic acid upon the complete C5 conversion (Supplementary Table 1, entry 6). It is noted that the selectivities to C5-DH and 2-hydroxypentanedioic acid were always low (<6%), indicating that the hydrogenation of C5-DH to KGA is facile compared to the dehydration of C5 and the excessive hydrogenation of KGA. Meanwhile, the total selectivities to KGA and 2-hydroxypentanedioic acid (derived from the KGA hydrogenation) increased from 92.5% to 99.9% with the decrease in the selectivities to C5-DH from 4.7% to 0.1%, reflecting the intermediate nature of C5-DH for the synthesis of KGA (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 7).

Similar to Pd/TiO2, the C5 conversions and selectivities to KGA on TiO2-supported Pt and Rh as well as SiO2- and ZrO2-supported Pd catalysts (2 wt% metal, metal particle sizes of 1.2–1.8 nm shown in Supplementary Figs. 6 and 8) fell in the narrow ranges of 30.8–35.1% and 91.6–94.4%, respectively, under the same reaction conditions (Supplementary Table 1, entries 1-5). These results indicate that these metal catalysts do not involve in the rate-determining dehydration of C5 to C5-DH and they predominantly catalyze the hydrogenation of the C=C bond in C5-DH, relative to its C=O bond (Fig. 2d).

Such favorable hydrogenation of the C=C bond in C5 on these metal catalysts was confirmed by the separate reactions of two model molecules, i.e., crotonic and pyruvic acids, with the similar chemical environments of the C=C and C=O bonds in C5, respectively. Crotonic acid was completely hydrogenated to butyric acid in a 100% selectivity on the metal catalysts at 40 °C for 0.5 h (Supplementary Table 2). However, the conversions of pyruvic acid were negligible (<3%) and its C=O bond remained intact on these metal catalysts under the identical conditions (Supplementary Table 3). Consistently, the hydrogenation of the C=C bond in crotonic acid showed a much lower apparent activation energy (15.1 kJ mol−1, Supplementary Fig. 9) on Pd/TiO2, relative to the hydrogenation of the C=O bond in pyruvic acid (68.2 kJ mol−1, Supplementary Fig. 10). Furthermore, these results can account for the observation that the hydrogenation of pyruvic acid (i.e., the unreacted pyruvic acid in the first aldol-condensation step) hardly proceeded (~3% conversion) on Pd/TiO2 during the dehydration and hydrogenation of the C5 intermediate to KGA. As a result, the excess pyruvic acid from the first step can be readily separated and recycled as a reactant for the new runs of the aldol condensation reaction with glyoxylic acid (for details, see Supplementary Fig. 11), reflecting the advantage of this method for the synthesis of KGA.

The stability of the Pd/TiO2 (2 wt% Pd) catalyst was examined during the conversion of C5 to KGA within kinetically-controlled regime (~35% conversions). During the five consecutive cycles, the C5 conversions and the selectivities to KGA remained almost constant, being 32.5-35.6% and 91.5-93.9%, respectively, at 110 °C and 1.0 MPa H2 (Supplementary Fig. 12). The inductively couple plasma–atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) analysis results showed that the concentrations of Pd and Ti in the reaction solution were below the detection level after the five cycles, indicating the negligible leaching of the Pd/TiO2 catalyst. The TEM images (Supplementary Fig. 13) showed that the mean size of the Pd particles on the spent Pd/TiO2 catalyst varied negligibly after the five cycles. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the Pd/TiO2 catalyst is stable and recyclable under the reaction conditions in this work.

Synthesis of Methanetriacetic Acid (MTA)

Similar to the condensation of pyruvic and glyoxylic acids, the cross-aldol condensation of KGA and glyoxylic acid, as the first step for the synthesis of MTA, also proceeded efficiently in the form of their sodium salts at a pH value of about 9. As shown in Fig. 3a, the KGA conversion reached 14.6% after 5 min at 50 °C, and the selectivity to 3-(carboxymethyl)-2-hydroxy-4-oxopentanedioic acid (C7, Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15) was 96.8%. A small amount of 3-(carboxymethyl)-4-oxopent-2-enedioic acid (C7-DH, 3.2% selectivity, Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15) was also formed from the dehydration of C7 (Fig. 3d). By prolonging the reaction time to 3.0 h, the KGA conversion increased to 85.8%, and the selectivities to C7 and C7-DH (i.e., the two desired intermediates of MTA) remained almost constant, being 96.5–98.4% and 1.6–3.5%, respectively. Such selectivity trends for the two intermediates indicate that the dehydration of C7 to C7-DH underwent slowly under the condensation conditions. No products were detected from the further condensation of C7 and glyoxylic acid at 50 °C, most likely due to the steric hindrance of the bulky carboxymethyl substituents in C7 (Supplementary Fig. 16).

a Evolution of conversions and selectivities for aldol condensation of KGA and glyoxylic acid (i.e., the first step of MTA synthesis) with reaction times. Reaction conditions: 50 °C, 5 mmol sodium α-ketoglutarate, 5 mmol sodium glyoxylate, 10 mL H2O. b Effect of α-ketoglutaric acid (KGA) concentrations on KGA conversions and selectivities for aldol condensation of KGA and glyoxylic acid. Reaction conditions: molar ratio of KGA to glyoxylic acid = 1:1, 50 °C, 3.0 h, 10 mL H2O. c Evolution of conversions and selectivities for hydrodeoxygenation (i.e., the second step of KGA synthesis) of 3-(carboxymethyl)-2-hydroxy-4-oxopentanedioic acid (C7) and 3-(carboxymethyl)-4-oxopent−2-enedioic acid (C7-DH) with reaction times on Pd/TiO2 and MoOx/TiO2. Reaction conditions: 0.5 mL condensation reaction solution of KGA and glyoxylic acid (2.0 mol L−1) at nearly complete conversion of KGA from the first step, 9.5 mL H2O, 3.0 mmol HCl, 0.10 g Pd/TiO2 (2 wt% Pd), 0.10 g MoOx/TiO2 (5 wt% Mo), 200 °C, 2.0 MPa H2. C7-Diol: 3-(carboxymethyl)−2,4-dihydroxypentanedioic acid; C7-ol: 3-(carboxymethyl)−2-hydroxypentanedioic acid. d Proposed reaction pathways of MTA synthesis from KGA and glyoxylic acid.

Further studies showed that the condensation reaction of KGA with glyoxylic acid to the C7 and C7-DH intermediates was kinetically favorable at their higher concentrations (Figsoxylic acid of 1:1), the conversions of KGA increased from 64.0% to 95.6% after the reaction for 3.0 h at 50 °C, while the total selectivities to C7 and C7-DH were always around 100%, leading to a high yield of 95.6% for the two desired intermediates (93.0% for C7 and 2.6% for C7-DH) at 2.0 mol L−1.

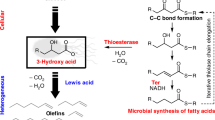

As the second step for the synthesis of MTA, the subsequent hydrodeoxygenation of C7 and C7-DH requires the selective cleavage of their α-C-OH bonds adjacent to the carboxyl groups via the 3-(carboxymethyl)-2,4-dihydroxypentanedioic acid (C7-Diol) and 3-(carboxymethyl)-2-hydroxypentanedioic acid (C7-ol) intermediates (Fig. 3d). This reaction was performed on a physically mixed catalyst of Pd/TiO2 and MoOx/TiO2 (2 wt% Pd and 5 wt% Mo; denoted as Pd/TiO2 + MoOx/TiO2) in the condensation reaction solution, as discussed above, after nearly complete conversions of KGA and glyoxylic acid. As shown in Fig. 3c, upon heating to the reaction temperature (i.e., 200 °C) at 2.0 MPa H2, the C7 and C7-DH intermediates were readily hydrogenated to C7-Diol and C7-ol in the selectivities of 83.8% and 11.5%, respectively, with a small amount of MTA (4.7%, Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19). With increasing the reaction time to 29.0 h, the selectivity to C7-Diol monotonically decreased to 0.6%, while the selectivity to C7-ol showed a volcano-type trend with a peak value of 44.8% at 6.0 h, and the selectivity to MTA concurrently increased to 79.9% (Fig. 3c), reflecting the intermediate nature of C7-Diol and C7-ol for the synthesis of MTA (Fig. 3d). It is also noted that, by-products were formed during the reaction, and their total selectivities reached 16.1% (Fig. 3c), as a result of the decarboxylation and hydrogenation of carboxyl groups in C7-Diol, C7-ol and MTA. These side reactions can be suppressed by tuning the reaction procedures and conditions. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 20, the C7 reaction was first carried out at a lower temperature (i.e., 110 °C) for cleaving its β-C-OH bond (adjacent to the ketone group) on Pd/TiO2, and then at a higher temperature (i.e., 200 °C) for cleaving the α-C-OH bond to form MTA on Pd/TiO2 + MoOx/TiO2. In this way, a high overall yield of 86.2% for MTA was obtained on a molar basis of KGA or glyoxylic acid.

For comparison with Pd/TiO2 + MoOx/TiO2 (Table 1, entry 1), Pd/TiO2 was individually examined under the identical conditions. It mainly catalyzed the hydrogenation of C7 to C7-Diol and C7-DH to C7-ol (Table 1, entry 2), and exhibited a low hydrodeoxygenation activity, as evidenced from the low selectivities of C7-ol (11.7%) and MTA (4.6%). The physical mixtures of Pd/TiO2 with WOx/TiO2 and NbOx/TiO2 still showed low selectivities to C7-ol (~13%) and MTA (~5%, Table 1, entries 3 and 4)). Such comparison shows that Pd/TiO2, WOx/TiO2 and NbOx/TiO2, when used individually, are not active for the cleavage of the α-C-OH group in C7-Diol and C7-ol. Furthermore, the Pd/TiO2 catalyst modified with dispersed MoOx species (Table 1, entry 5) exhibited similar selectivities (44.2% C7-ol, 32.7% MTA) to those observed with the physically mixed Pd/TiO2 and MoOx/TiO2. These results reveal that MoOx is an essential component, independent of its presence in close contact or physically mixing with the Pd sites, for catalyzing the selective cleavage of the α-C-OH bonds in the C7-Diol and C7-ol intermediates.

Detailed characterization of the MoOx/TiO2 and Pd/TiO2 components suggests that the essential role of MoOx is closely related to its reducible and oxophilic nature. The MoOx species were highly dispersed on MoOx/TiO2 without the detectable formation of MoO3 crystallites (Supplementary Figs. 21 and 22). Upon physical mixing with Pd/TiO2, they tended to be more readily reduced partially from Mo6+ to Mo5+ via the hydrogen spillover from the Pd surfaces, leading to the formation of the oxygen vacancies on MoOx/TiO2 (Supplementary Figs. 23–25). Such reduced MoOx species facilitated the adsorption and activation of the α-C-OH bonds in C7-Diol and C7-ol to efficiently form MTA.

In comparison with Pd, other noble metals (Pt, Rh and Ru) with similar particle sizes (1.2–1.7 nm; TEM micrographs shown in Supplementary Fig. 6) on TiO2 were also examined in the C7 reaction. Physically mixing with MoOx/TiO2, they also mainly afforded the hydrogenolysis products of C7-ol (29.7–39.5%) and MTA (26.3–31.9%), but the selectivities to by-products (10.1-35.0%) were higher under the same conditions (Table 1, entries 6-8), most likely due to the higher activities for the reduction of the carboxyl group of C7-Diol, C7-ol and MTA on Pt/TiO2, Rh/TiO2 and Ru/TiO2. Such comparison shows the superiority of Pd as a key component with MoOx/TiO2 for the efficient synthesis of MTA.

Meanwhile, the Pd/TiO2 + MoOx/TiO2 catalyst was noted to be stable in the reaction of C7 to MTA. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 26, the C7 conversions and the selectivities to C7-ol and MTA remained almost constant, being 100%, 24.1–26.1% and 9.4–11.1%, respectively, during the five consecutive cycles at 200 °C and 2.0 MPa H2. The ICP-AES analysis results after each cycle showed no detecting leaching of Pd, Ti and Mo into the aqueous reaction solution. The TEM images (Supplementary Fig. 27) showed that the mean sizes of the Pd particles on Pd/TiO2 did not change essentially (1.7 vs 1.8 nm) after the five cycles. Raman spectra showed no aggregation of the dispersed MoOx on TiO2 after the recycling experiments (Supplementary Fig. 28). Clearly, these results demonstrate that the TiO2-supported Pd and MoOx catalysts are stable and recyclable under the reaction conditions used in this study.

Discussion

In summary, a novel one-pot approach has been developed for the sustainable synthesis of KGA and MTA from biomass-based pyruvic and glyoxylic acids in water via their cross-aldol condensation and subsequent hydrodeoxygenation reactions. The aldol condensation of glyoxylic acid with pyruvic acid and KGA occurs efficiently in the aqueous solutions of their sodium salts to form the C5 and C7 intermediates, respectively, under mild conditions. Subsequently, the C5 intermediate undergoes efficient dehydration and hydrogenation to form KGA on Pd/TiO2 with a high stability and recyclability. The physically mixed catalysts of Pd/TiO2 and MoOx/TiO2 exhibit a high efficiency and stability in the hydrodeoxygenation of the C7 intermediate to MTA, for which the MoOx species are notably essential for the selective cleavage of the α-C-OH bonds adjacent to the carboxyl group, while the Pd sites merely catalyze the activation of H2 and hydrogenation of the C=C and C=O bonds. This novel approach affords the high overall yields of KGA (85.4%) and MTA (86.2%), which demonstrates the feasibility and promising potentials for the synthesis of various multi-functional carboxylic acids with high atom economy and sustainability.

Methods

Reagents and materials

All the chemicals used in this study were obtained from certified reagent sources and were used without further purification. Sodium pyruvate, butyric acid and deuterium oxide (D2O) were purchased from Energy Chemicals (Shanghai, China). Sodium glyoxylate and crotonic acid were purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). Sodium α-ketoglutarate was purchased from Duly Biotech (Nanjing, China). Pd(NH3)4(NO3)2 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Missouri, USA). H2PtCl6·6H2O, RhCl3·3H2O and RuCl3·xH2O were purchased from Beijing Chemical Reagents (Beijing, China). (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O was purchased from Xilong Chemical Factory (Guangdong, China). (NH4)6W7O24·6H2O, hydrochloric acid, barium chloride and ethanol were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Beijing, China). Cation-exchange resin (Dowex 50WX8, H-form, 200–400 mesh) and TiO2 were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Shanghai, China). NH4[NbO(C2O4)2]·xH2O was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). Sodium hydroxide solution (0.1 M) was purchased from J&K Scientific (Beijing, China). SiO2 was purchased from Macklin (Shanghai, China).

Catalyst Preparation

Supported metal catalysts were prepared by an incipient wetness impregnation method. Taking Pd/TiO2 as an example, TiO2 was added into an aqueous solution of Pd(NH3)4(NO3)2 with vigorous stirring at 25 °C. The resultant suspension was stirred vigorously at 500 rpm and 25 °C for 6 h, and then evaporated to dryness at 60 °C under vacuum. Afterwards, the resulting powder was dried at 110 °C overnight, calcined in flowing synthetic air (Beijing Haipu) at 500 °C for 3 h, and then reduced in a 20% H2/N2 (Beijing Haipu) flow at 450 °C for 2 h (at 100 °C for 1 h for Pd/SiO2 to prevent the aggregation of Pd particles). Using the same method, the other supported metal catalysts were prepared using different metal precursors (i.e., H2PtCl6·6H2O, RhCl3 and RuCl3) and supports (i.e., ZrO2 and SiO2).

Supported oxide catalysts were also prepared by an incipient wetness impregnation method. Taking MoOx/TiO2 as an example, TiO2 was added into an aqueous solution of (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O with vigorous stirring at 25 °C. The resultant suspension was stirred vigorously at 500 rpm and 25 °C for 6 h, and then evaporated to dryness at 60 °C under vacuum. Afterwards, the resulting powder was dried at 110 °C overnight, and then calcined in flowing synthetic air (Beijing Haipu) at 500 °C for 3 h. By the same method, the other supported oxide catalysts were prepared using different metal precursors (i.e., NH4[NbO(C2O4)2]·xH2O and (NH4)6W7O24·6H2O). Following the same procedure, Pd-MoOx/TiO2 catalyst was prepared by incipient wetness impregnation of TiO2 with aqueous solutions of Pd(NH3)4(NO3)2 and (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O.

Catalyst and product characterization

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were taken on a JEOL JEM-F200 electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. All samples were prepared by uniformly dispersing in ethanol ultrasonically treating for 5 min, and then dripping onto an ultra-thin copper mesh using a glass capillary. The copper mesh was then dried in a glass desiccator at 25 °C for 2 h. The average sizes of metal particles and their size distributions were determined by measuring more than 250 particles randomly distributed in the TEM images.

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mappings were performed on a JEOL JEM-F200 transmission electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV with a JED−2300T detector. All samples were prepared by the same procedure, as described above for the TEM measurements.

Raman spectra of MoOx/TiO2 samples were acquired at 25 °C on a Micro Raman imaging spectrometer (DXRxi, ThermoFisher Scientific) with a resolution of 1.0 cm−1 using a 532 nm He-Ne laser.

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded on a PANalytical X-Pert3 Powder diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm) at 40 kV and 40 mA at 25 °C. The powder samples were placed inside a quartz-glass holder, and the 2θ angle was scanned in the range of 20-70o at a speed of 5° min−1.

X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS) analyzes were performed on an AXIS Supra spectrometer (Kratos Analytical Ltd.) using monochromatized Al Kα radiation. The binding energies were calibrated by referring to the C1s line at 284.6 eV.

Hydrogen temperature-programmed reduction (H2-TPR) experiments were carried out on a TP5080 flow unit (Tianjin Xianquan). A sample containing ca. 2.5 mg of Mo was placed in a quartz tube and treated at 200 °C for 1 h in a He flow (50 mL/min). H2-TPR profiles were then recorded by a TCD detector from 40 °C to 800 °C at a temperature ramp of 10 °C/min in a 5% H2/N2 flow (50 mL/min).

Hydrogen temperature-programmed desorption (H2-TPD) experiments were carried out on a TP5080 flow unit (Tianjin Xianquan). Physically mixed Pd/TiO2 (75 mg), MoOx/TiO2 (75 mg) or TiO2 (75 mg) samples were placed in a quartz tube and treated at 200 °C for 1 h in a 10% H2/Ar flow (30 mL/min). Afterwards, H2-TPD profiles were then recorded by a mass spectrometer from 50 °C to 800 °C at a ramping rate of 10 °C/min under an Ar flow (30 mL/min).

The concentrations of Pd, Ti and Mo for Pd/TiO2 and MoOx/TiO2 catalysts in the reaction solutions were measured by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES, Leeman Prodigy 7), and each sample was measured three times to obtain an average value.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra for the reaction intermediates and products were recorded on a Bruker 600-MHz NMR spectrometer (600 MHz for 1H-NMR and 151 MHz for 13C-NMR) in D2O. Mass spectrometric spectra were recorded on a Bruker Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer (Solarix XR) in H2O.

Catalytic reactions

The aldol condensation reactions of pyruvic and glyoxylic acids were carried out in a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave (50 mL) at a stirring speed of 450 rpm. In a typical run, sodium pyruvate (2 mmol), sodium glyoxylate (2 mmol) and H2O (10 mL) were introduced to the autoclave, and then heated to 80 °C under autogenous pressure. After reaction, the reaction solution was diluted with deionized water. Similarly, the aldol condensation reactions of α-ketoglutaric (KGA) and glyoxylic acids were carried out in the autoclave at 50 °C, typically containing 20 mmol sodium α-ketoglutarate and 20 mmol sodium glyoxylate in 10 mL H2O.

The reaction of the C5 intermediate was also carried out in the autoclave at a stirring speed of 450 rpm. In a typical run, supported catalyst (30.0 mg) was introduced into the condensation reaction solution (10 mL) of pyruvic and glyoxylic acids with an initial ratio of 4:1 at nearly complete glyoxylic acid conversion in the autoclave, and then the autoclave was sealed. The reactor was purged with H2 three times. Afterwards, the autoclave was pressurized with 1.0 MPa H2 at 25 °C and then heated to 110 °C, which was kept constant during the reaction. After reaction, the aqueous solution was filtered and the filtrate was diluted with deionized water. The catalyst was washed with deionized water three times and then dried in an oven at 60 °C for 6 h. Similarly, the hydrogenolysis reaction of the C7 intermediate was carried out in the autoclave at 200 °C and 2.0 MPa H2, typically containing 0.1 g M/TiO2 (M=Pd, Pt, Rh or Ru, 2 wt%), 0.1 g NOx/TiO2 (N=Mo, W or Nb, 5 wt%), 3 mmol HCl and 0.5 mL condensation reaction solution of KGA and glyoxylic acid at their nearly complete conversion in 9.5 mL H2O.

The reactants and products in aqueous solutions were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Shimadzu LC-20A) equipped with a refractive index (RID) detector and a Shodex Sugar-SH1011 column, using 0.01 mol L−1 H2SO4 aqueous solution as the mobile phase with a flow rate of 0.8 mL min−1. The concentrations of KGA and MTA in reaction solutions were determined by HPLC using KGA and MTA as an external standard, respectively. The products selectivities were reported on a molar basis.

Separation of sodium pyruvate

The separation of excess sodium pyruvate from the reaction solution of the C5 hydrogenolysis was performed by precipitating α-ketoglutarate and by-products in the form of their barium salts via addition of barium chloride and ethanol. Barium chloride (2.00 mmol) and ethanol (30 mL) were added to the C5 reaction solution (5 mL) with vigorous stirring at 25 °C for 2 h. Afterward, the resulting white precipitation was collected by filtration, and then dried in a vacuum at 30 °C. The corresponding filtrate was evaporated to dryness at 40 °C under vacuum to obtain excess sodium pyruvate.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Li, M. et al. Electrosynthesis of amino acids from NO and α-keto acids using two decoupled flow reactors. Nat. Catal. 6, 906–915 (2023).

Xiao, Y. et al. Electrocatalytic amino acid synthesis from biomass-derivable keto acids over ball milled carbon nanotubes. Green. Chem. 25, 3117–3126 (2023).

Gadgeel, A. A. & Mhask, S. T. Synthesis and characterization of UV curable polyurethane acrylate derived from α-Ketoglutaric acid and isosorbide. Prog. Org. Coat. 150, 105983 (2021).

Mangal, J. L. et al. Metabolite releasing polymers control dendritic cell function by modulating their energy metabolism. J. Mater. Chem. B 8, 5195–5203 (2020).

Barrett, D. G. & Yousaf, M. N. Poly(triol α-ketoglutarate) as biodegradable, chemoselective and mechanically tunable elastomers. Macromolecules 41, 6347–6352 (2008).

Chao, H. et al. Backbone-hydrolyzable poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) bis(glycidyl ether)-alt-ketoglutaric acid) with tunable LCST behavior. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 220, 1900004 (2019).

Gyanwali, B. et al. Alpha-ketoglutarate dietary supplementation to improve health in humans. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 33, 136–146 (2022).

Gaunt, A. P. et al. Labile photo-induced free radical in α-ketoglutaric acid: a universal endogenous polarizing agent for in vivo hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202112982 (2022).

Downs, F. G. et al. Multi-responsive hydrogel structures from patterned droplet networks. Nat. Chem. 12, 363–371 (2020).

Shahmirzadi, A. A. et al. Alpha-ketoglutarate, an endogenous metabolite, extends lifespan and compresses morbidity in aging mice. Cell Metab. 32, 447–456 (2020).

Sultana, S. et al. Alpha ketoglutarate nanoparticles: a potentially effective treatment for cyanide poisoning. Eur. J. Pharm. BioPharm. 126, 221–232 (2018).

Chin, R. M. et al. The metabolite α-ketoglutarate extends lifespan by inhibiting ATP synthase and TOR. Nature 510, 397–401 (2014).

Guo, F.-S., Leng, J.-D., Liu, J.-L., Meng, Z.-S. & Tong, M.-L. Polynuclear and polymeric gadolinium acetate derivatives with large magnetocaloric effect. Inorg. Chem. 51, 405–413 (2012).

Martínez-Benito, C. et al. Tailor-made copper(II) coordination polymers based on the C3 symmetric methanetriacetate as a ligand. CrystEngComm 19, 376–390 (2017).

Lippert, A. R., Naganawa, A. V., Keleshian, L. & Bode, J. W. Synthesis of phototrappable shape-shifting molecules for adaptive guest binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 15790–15799 (2010).

Allen, O. R. et al. Ruthenium complexes of CP3: a new carbon-centered polydentate podand ligand. Organometallics 30, 6433–6440 (2011).

Canadillas-Delgado, L. et al. The construction of open GdIII metal-organic frameworks based on methanetriacetic acid: new objects with an old ligand. Chem. Eur. J. 16, 4037–4047 (2010).

Bae, S. H. et al. Mononuclear nonheme high-spin (S=2) versus intermediate-spin (S=1) iron(IV)-oxo complexes in oxidation reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 8027–8031 (2016).

Rains, J. G. D. et al. Bicarbonate inhibition of carbonic anhydrase mimics hinders catalytic efficiency: elucidating the mechanism and gaining insight toward improving speed and efficiency. ACS Catal. 9, 1353–1365 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Boosting NH3 production from nitrate electroreduction via electronic structure engineering of Fe3C nanoflakes. Green. Chem. 23, 7594–7608 (2021).

Usman, M. et al. Simultaneous adsorption of heavy metals and organic dyes by β-cyclodextrin-chitosan based cross-linked adsorbent. Carbohydr. Polym. 255, 117486 (2021).

Wu, J. et al. Promoter engineering of cascade biocatalysis for α-ketoglutaric acid production by coexpressing L-glutamate oxidase and catalase. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 4755–4764 (2018).

Al-Shameri, A., Siebert, D. L., Sutiono, S., Lauterbach, L. & Sieber, V. Hydrogenase-based oxidative biocatalysis without oxygen. Nat. Commun. 14, 2693 (2023).

Chen, X., Dong, X., Liu, J., Luo, Q. & Liu, L. Pathway engineering of Escherichia coli for α-ketoglutaric acid production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 117, 2791–2801 (2020).

Zeng, W., Zhang, H., Xu, S., Fang, F. & Zhou, J. Biosynthesis of keto acids by fed-batch culture of Yarrowia lipolytica WSH-Z06. Bioresour. Technol. 243, 1037–1043 (2017).

Sun, Y. et al. A single-atom iron nanozyme reactor for α-ketoglutarate synthesis. Chem. Eng. J. 466, 143269 (2023).

Singh, J. et al. 13C-Labeled diethyl ketoglutarate derivatives as hyperpolarized probes of 2-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase activity. Anal. Sens. 1, 156–160 (2021).

Choudhary, H., Nishimura, S. & Ebitani, K. Metal-free oxidative synthesis of succinic acid from biomass-derived furan compounds using a solid acid catalyst with hydrogen peroxide. Appl. Catal., A 458, 55–62 (2013).

Hou, T., Zhang, J., Wang, C. & Luo, J. A facile method to construct a 2,4,9-triazaadamantane skeleton and synthesize nitramine derivatives. Org. Chem. Front. 4, 1819–1823 (2017).

Liu, H., Huang, Q., Liao, R.-Z., Li, M. & Xie, Y. Ring-closing C-O/C-O metathesis of ethers with primary aliphatic alcohols. Nat. Commun. 14, 1883 (2023).

You, Y. et al. Distinct selectivity control in solar-driven bio-based α-hydroxyl acid conversion: a comparison of Pt nanoparticles and atomically dispersed Pt on CdS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202306452 (2023).

Bie, C. et al. A bifunctional CdS/MoO2/MoS2 catalyst enhances photocatalytic H2 evolution and pyruvic acid synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202212045 (2022).

Liu, K., Huang, X., Pidko, E. A. & Hensen, E. J. M. MoO3-TiO2 synergy in oxidative dehydrogenation of lactic acid to pyruvic acid. Green. Chem. 19, 3014–3022 (2017).

Yin, C. et al. The facet-regulated oxidative dehydrogenation of lactic acid to pyruvic acid on α-Fe2O3. Green. Chem. 23, 328–332 (2021).

Zhang, C., Wang, T. & Ding, Y. Oxidative dehydrogenation of lactic acid to pyruvic acid over Pb-Pt bimetallic supported on carbon materials. Appl. Catal., A 533, 59–65 (2017).

Chadderdon, D. J. et al. Selective oxidation of 1,2-propanediol in alkaline anion-exchange membrane electrocatalytic flow reactors: experimental and DFT investigations. ACS Catal. 5, 6926–6936 (2015).

Feng, Y., Li, W., Meng, M., Yin, H. & Mi, J. Mesoporous Sn(IV) doping MCM-41 supported Pd nanoparticles for enhanced selective catalytic oxidation of 1,2-propanediol to pyruvic acid. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 253, 111–120 (2019).

Kim, J. E. et al. Electrochemical synthesis of glycine from oxalic acid and nitrate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 21943–21951 (2021).

Yan, K., Huddleston, M. L., Gerdes, B. A. & Sun, Y. Electrosynthesis of amino acids from biomass-derived α-hydroxyl acids. Green. Chem. 24, 5320–5325 (2022).

Manker, L. P. et al. Sustainable polyesters via direct functionalization of lignocellulosic sugars. Nat. Chem. 14, 976–984 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grants 2023YFA1506802 and 2021YFA1501104), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 22032001 and 22402002), China National Petroleum Corporation-Peking University Strategic Co-operation Project of Fundamental Research, and the Beijing National Laboratory for Molecular Sciences (Grant BNLMS-CXXM-201905).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L. conceived and directed the project. C.-B.H. planned the project, and designed and conducted the experiments and data analysis. W.H. and L.L. participated in the experimental work. C.-B.H. and H.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, CB., Hua, W., Liu, L. et al. Sustainable synthesis of α-ketoglutaric and methanetriacetic acids from biomass feedstocks. Nat Commun 16, 1245 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56536-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56536-z