Abstract

Zinc-ion batteries have demonstrated promising potential for future energy storage, whereas drawbacks, including dendrite growth, hydrogen evolution reaction, and localized deposition, heavily hinder their development for practical applications. Herein, unlike elaborated structural design and electrolyte excogitation, we introduce an effective parts-per-million (ppm)-scale electrolyte additive, phosphonoglycolic acid (PPGA), to overcome the intrinsic issues of zinc negative electrode in mild acidic aqueous electrolytes. Profiting from absorbed PPGA on zinc surface and its beneficial interaction with hydrogen bonds of adjacent water molecules, stable symmetric stripping/plating of zinc in aqueous ZnSO4 electrolyte at around 25 oC was achieved, procuring 362 and 350 days of operation at 1 mA cm-2, 1 mAh cm-2 and 10 mA cm-2, 1 mAh cm-2, respectively. As a proof-of-concept, an Ah-level Zn||Zn0.25V2O5·nH2O pouch cell examined the validity of PPGA and sustained 250 cycles at 0.2 A g-1 and around 25 oC without capacity loss. The Zn||Br2 redox flow battery demonstrated an operation of over 800 h at 40 mA cm-2, 20 mAh cm-2 with an average coulombic efficiency of 98%, which is attributed to restrained dendrite growth and side effects. This work is believed to open up new ways forward for knowledge of electrolyte additive engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rechargeable aqueous Zinc-ion batteries are attracting increasing attention with the ever-growing demand for large-scale energy storage applications, especially given the cost-effectiveness, intrinsic safety, low redox potential (-0.76 V vs standard hydrogen electrode, SHE), and competitive specific capacity (820 mAh g−1) of metallic zinc1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Yet the deposition of zinc metal in mildly acidic aqueous electrolytes is often accompanied by the nucleation of zinc hydroxyl complex and hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) as to the battery failure after undue consumption of electrolytes and infiltrating growth of zinc dendrites8,9,10.

Strategies ranging from the geometric conformation of the zinc negative electrode and separator to electrolyte configuration have advanced the controlled Zn nucleation/growth with suppressed side reactions11,12,13,14,15,16,17. For instance, zinc-titanium alloy was found to restrain intergranular corrosion and favor the uniform deposition of zinc negative electrode18. Miscible molecules with a higher Gutmann donor number (DN) than water (DN = 18), such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, DN = 29.8) and N, N-dimethylacetamide (DMA, DN = 27.8), were found to reconstruct the solvation sheath of Zn2+ and suppress water reduction and growth of zinc dendrites19,20. However, adverse effects arising from those negative electrode treatments have not yet been considered squarely for the time being. For example, heavy use of water-miscible polar organic solvent can cause the inevitable dissolution of classic conversion-type positive electrode materials such as halogens, chalcogens, and their derivatives21,22, while the complicated design of either the negative electrode or the separator is not particularly economical23,24; each solution can undermine the applicability of zinc negative electrode on a broader perspective.

Unlike a radical change of the electrolyte and zinc surface, additive engineering toward the aqueous electrolyte is perhaps the most promising way to counteract the degradation of zinc negative electrode and ensure its universality for different aqueous zinc-ion batteries25. Furthermore, the feeding amount of additive in aqueous electrolytes can go down to less than 1 mM26, which could present a cost-effective and general method to regulate zinc deposition without bothering the positive electrode part. However, the resulting battery reversibility is far below that of their counterparts treated by conventional methods, highlighting the significance of developing effective electrolyte additives while sustaining a reasonably low feeding amount for economic considerations27,28,29. The success of corrosion and scale inhibitors that take effect at a low dosage (several ppm) to increase the solubility of solutes and prevent scale formation in water systems motivates us to reach our goal of manipulating Zn chemistry30,31,32.

Herein, we proposed a ppm-scale effective inhibitor, phosphonoglycolic acid (PPGA), as the additive to the ZnSO4 electrolyte. Considering the low dosage and the necessity to understand the operational mechanism of the threshold scale inhibitor, we exposed zinc electrodes to a sub-ppm-level PPGA solution (0.1 wt%) for various durations, leading to a progressive evolution of the byproducts in terms of phase structure, crystallinity, and quantity produced. In line with theoretical predictions, the findings demonstrated that PPGA was inclined to adhere to the surface of zinc metal and interact with circumambient water molecules to regulate zinc deposition and restrain side effects in both pouch cells and redox flow batteries. In addition to comprehending the ppm-scale additive, our methodologies for monitoring the formation, growth, and types of byproducts could offer valuable insights into zinc negative electrode studies.

Results

Working principle of PPGA

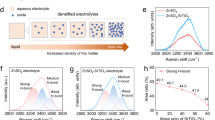

The water-soluble PPGA is widely employed in industries as a cathodic corrosion inhibitor, effectively halting scale formation at substoichiometric level by intervening in one or more steps of the scale formation processes, such as aggregation, nucleation, crystal growth, and agglomeration33,34,35,36. It is a chemically stable organophosphorus compound featured with a carboxyl group, a phosphono group, and a hydroxyl group covalently bonded to a carbon atom, as depicted in Fig. 1a. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations revealed that the outward hydrogen atoms of PPGA were partially charged as the oxygen atom was more electronegative than either carbon or hydrogen. Such molecular geometry endowed PPGA with a high tendency to form hydrogen bonds with adjacent water molecules by donating one hydrogen proton (-OH…OH2) with a high average bond energy of −0.76 eV while that for the -O…H2O hydrogen bonds was down to -0.27 eV, close to the strength of the intermolecular hydrogen bonds in water (Supplementary Fig. 1). 2 mol L−1 ZnSO4 electrolyte was referred to as BZS for the subsequent additive study. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra in Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2 confirmed the strong interaction between PPGA and H2O, with BZS utilized as the background to specifically analyze the signals originating from HZS. Specifically, with the increase of PPGA additive (0–10 ppm), the O-H stretching vibration experienced a continuous blue-shift of from 3182 cm−2 to 3243 cm−1 due to reduced mass of water molecule and decreased O-H bond length, both of which hinted at the destruction of intermolecular hydrogen bonds of water. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) measurement in Fig. 1c demonstrated an upfield chemical shift with the inclusion of PPGA (5 ppm) due to increased electron density and reduced number of deshielded protons, convincing the disruption of intermolecular water hydrogen bond network.

a The interaction between PPGA and H2O. b FTIR spectra of BZS with a varying amount of PPGA (0, 1, 5, or 10 ppm), where BZS was used to subtract the background. c 1H NMR spectra of BZS electrolyte and that with 5 ppm PPGA. d MD simulation of PPGA (marked by a green ellipsoid) and e corresponding energy evolution. f XRD patterns of zinc metal treated with studied electrolytes. The inset in (a) denotes the electrostatic potential map of PPGA. In (a and d), the color scheme for the spheres is as follows: red is oxygen, white is hydrogen, gray is carbon, light gray in (d) is zinc, pink is phosphor, and yellow represents sulfur atoms.

Although wandered away from performing as a hydrogen bond acceptor, the electronegative oxygen atom of PPGA exhibited high responsibility for the adsorption on the zinc surface, particularly along the (002) lattice plane of zinc (Supplementary Fig. 3). This resulted in a considerable binding energy of −0.73 eV, surpassing that of H2O molecules (−0.27 eV). Its strong adsorption ability was further confirmed by Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. As demonstrated in Fig. 1d, e, PPGA suspended in ZnSO4 electrolyte could successfully reach the zinc electrode at 240 ps and edged along the surface in the following 3760 ps, contributing to an overall decline in energy for a more stable system. The formation of zinc hydroxyl complex, which nucleated with localized pH increase and concomitant HER, reached minimal as unscaled water clusters and dynamic adsorption of PPGA on the zinc surface. As shown in Fig. 1f, zinc metal that soaked in BZS for 10 days gave strong X-ray diffractions (XRD) from 3Zn(OH)2·ZnSO4·5H2O, which was simplified as Zn4SO4(OH)6·5H2O. Remarkably, its crystallization was significantly suppressed by introducing 1 ppm of PPGA into the ZnSO4 electrolyte and entirely disappeared as the feeding amount reached 5 ppm.

To understand the working principle of adsorbed PPGA, we proposed a modified negative electrode treatment strategy to reach sub-ppm-level adsorption on the zinc surface (Fig. 2a). Specifically, zinc metal was soaked in a mixed solution of 0.1 wt% PPGA and BZS for a varying time (0, 1, 5, or 10 min), followed by water rinse and continuous immersion in BZS for 10 days. It is important to highlight that a high dosage of PPGA could be detrimental to the zinc electrodes and may have limited effectiveness in suppressing side effects (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 1)37. As shown in the XRD spectra in Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 5, the zinc hydroxyl complex crystallized with a decreasing hydration number from 5 (3Zn(OH)2·ZnSO4·5H2O) to 4 (3Zn(OH)2·ZnSO4·4H2O) and 3 (3Zn(OH)2·ZnSO4·3H2O) with prolonged treatment time. This process was accompanied by a reduction in Raman intensity of the O-H vibration and suppressed crystallization peaks, indicating its ability to impede the nucleation and growth of the zinc hydroxyl complex (Supplementary Fig. 6). The crystal size study derived from the Scherrer formula further verified the above argument38. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 2c, the average crystal size of the complex decreases to the nanoscale (<70 nm) after PPGA exposure. Notably, the average size of surface zinc was also slightly reduced, which may be attributed to the improved surface morphology by PPGA, as will be discussed later. Localized scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images in Fig. 2d further supported the crystalline evolution of the zinc hydroxyl complex. Massive bulk crystals clustered on the zinc surface in the control sample, leading to substantial electron accumulation and imaging artifacts. However, these insulating byproducts greatly decreased after a 10-min treatment in the proposed mixed solution. The treatment enabled a weaker binding with oxidation and enhanced Zn metal bonds according to the high-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra in Fig. 2e, f. Instead, the sample lacking adsorbed PPGA exhibited a minor O-H bond at around 526 eV, stemming from the zinc hydroxyl complex presented on the zinc surface. A slight signal in the P2p region may hint at the adsorbed PPGA at the zinc surface after 10 min of soaking (Supplementary Fig. 7). Remarkably, the Zn 2p3/2 core level spectra of the control sample possessed a special broad peak subjecting to the accumulation of valence charge in the Zn vicinity which would favor the nucleation of the zinc hydroxyl complex39. DFT results in Fig. 2g supportively demonstrated a remarkable energy drop after the adsorption of PPGA on the Zn(OH)2 surface in multiple contact modes (P-O…H, or C-O…H, or their mixture), which helped restrain the nucleation and growth of the hydroxyl compound.

a A method designed to evaluate the function of PPGA on the zinc surface. b XRD pattern of treated zinc metals. c derived crystal size of zinc hydroxyl complex. d SEM images of treated zinc metals. XPS spectra of e O 1 s and f Zn 2p3/2 core levels of fresh zinc metal and the one treated for 10 min. g Interaction between PPGA and zinc hydroxide.

Electrochemical effect of PPGA

Considering the role of passivating zinc surface and modulating water hydrogen bond network, the BZS electrolyte with 5 ppm PPGA additive, hereafter denoted as PZS, was further brought for electrochemical studies. The relatively lower HOMO level of the PPGA molecule theoretically favored a stronger attraction toward free electrons to raise the energy barrier of HER (Fig. 3a). Experimental observations shown in the inset of Fig. 3b witnessed the violent HER of a three-electrode Zn|BZS|Ti cell (swept from −1.25 V to 0 V with a scan rate of 5 mV/s). Remarkably, with the inclusion of PPGA, HER was significantly suppressed according to the dropped current and vanished H2 bubbles in the PZS electrolyte, as well as a much lower corrosion current, revealing uniform zinc deposition (Fig. 3c). The chronoamperometry (CA) measurement in Fig. 3d suggested a low reduction current and a fast 3D diffusion process in PZS owing to the absence of the notorious concomitant HER. MD simulations in Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Note 2 further exhibited guided zinc flux (which was mitigated to some extent for uniform deposition) and favored desolvation of Zn2+ cations near the zinc electrode in PZS. As such, highly reversible cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of Zn|PZS|Ti were achieved with a low and consistent deposition current during the 50 scans at 1 mV s-1 (Fig. 3e). The evolution of CV curves was subsequently visualized in Fig. 3f where the amount of charged/discharged electricity of Zn|PZS|Ti and the associated nucleation potential mostly remained localized arising from the highly reversible Zn stripping/plating process.

a HOMO-LUMO structure with the energy level diagram of PPGA. b linear sweep voltammetry (LSV, scanned from 1.25 V to 0 V), c linear polarization, d CA (measured under a bias of −1.2 V) and e CV curves of Zn|BZS|Ti and Zn|PZS|Ti cells and f the derived evolution of electric charge during each stripping and plating steps. The blue region (holes) and green region (electrons) in (a) reflect a positive and negative phase, respectively.

Moreover, PZS facilitated a notably symmetrical and reversible deposition in the Zn||Zn cell, exhibiting a low fD factor (following the equation \({f}_{D}=|{I}_{P(002)}/{I}_{P(101)}-{I}_{S(002)}/{I}_{S(101)}|\times 100\%\)) of 6.3% (after 50 cycles) and 4.4% (after 300 cycles) at 1 mA cm−2, 1 mAh cm−240, suggesting a balanced and progressively improved stripping and deposition on the two symmetric Zn electrodes (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 9). Instead, the fD value of Zn|BZS|Zn was nearly tripled in 50 cycles, subjected to the intensive accumulation of zinc hydroxyl complex as a marker of HER. The overlayed SEM image in Fig. 4b exhibits that the plated zinc electrode in PZS was smooth and neat. In contrast, the control sample was dominated by hydroxyl byproducts (marked in purple) and deep cracks. SEM and SEM-mapping images with a broader field of vision further convinced the uniform deposition/stripping of zinc in Zn|PZS|Zn cell without byproducts and corrosion spots (Supplementary Figs. 10–12 and Supplementary Note 3).

a XRD patterns of stripped/plated zinc electrodes in Zn||Zn cells, b associated SEM images of the plated side. Zn | |Zn cells cycled at c 1 mA cm−2, 1 mAh cm−2 and d 10 mA cm−2, 1 mAh cm−2. e Zn||Cu cells cycled at 1 mA cm−2, 1 mAh cm−2. f Comparison of achieved cycling performance with values reported in the literature (estimated by simplified ex-post calculations). It is noted that the cycling measurements were conducted at around 25 oC and “-S” and “-P” in (a) denote a complete stripping and plating process, respectively.

Remarkably, with the inclusion of PZS, the Zn||Zn symmetric cell sustained a 362- and 350-days’ operation at 1 mA cm-2, 1 mAh cm−2, and 10 mA cm−2, 1 mAh cm−2, respectively, while Zn|BZS|Zn cell finished in 120 hours (Fig. 4c, d). The attractive performance of PPGA primarily stemmed from its passivation to the zinc surface and interaction with water molecules. Notably, during the initial cycling stages, a significant stripping optimization (an autonomous reduction of stripping overpotential) of the Zn|PZS|Zn cell occurred without external intervention despite the initially high stripping overpotential resulting from an uneven zinc surface or insufficient polishing treatment (Fig. 4c). This validates the gradual modification of the zinc surface by PPGA, corroborated by the decreased crystallite size of bulk zinc as indicated in the XRD results presented in Fig. 2c. PPGA ignited successful cycling of Zn||Zn symmetric cells at a varying current density (from 0.5 mA cm−2 to 10 mA cm−2) with averted short circuit (Supplementary Fig. 13). The special line further advanced to long-term cycling at higher current density and areal capacity. Specifically, unlike in BZS, where cells ended with either penetration of zinc dendrites (short circuit) or channel blockage, the Zn|PZS|Zn cell operated stably at 5 mA cm−2, 2 mAh cm−2 for 2000 h and at 10 mA cm−2, 10 mAh cm-2 for 500 h (Supplementary Fig. 14, 15). The reduced nucleation overpotential observed in Supplementary Fig. 15 somewhat indicates an optimized zinc deposition process, aligning with PPGA’s function in modifying the zinc surface. The reversibility of zinc deposition was further examined by the Zn|PZS|Cu configuration which successfully cycled at 1 mA cm−2, 1 mAh cm−2 for 1000 times (2000 h) with a high average coulombic efficiency (CE) of 99.2% (Fig. 4e). In contrast, the Zn|BZS|Cu encountered perforation of the separator in 100 cycles next to battery short circuit (Supplementary Fig. 16). The ppm scale addition of PPGA (5 ppm) raises our interest in crosswise comparison with other additives. As demonstrated in Fig. 4f, PPGA took a notable mark concerning the additive amount (5 ppm), accumulated capacity (84.19 Ah cm−2), and current density (10 mA cm−2), outperforming its counterparts.

PPGA in full batteries

To assess the capability of PPGA for practical use, Zn|PZS|Zn0.25V2O5·nH2O full batteries were favorably assembled (Supplementary Fig. 17). According to the CV in Fig. 5a, PPGA (5 ppm) was found to be inert toward the Zn0.25V2O5·nH2O positive electrode (Supplementary Fig. 18), apart from a slight contribution to the overall charge quantity. The distribution of relaxation times (DRT) analysis was derived from the quantitative deconvolution of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) spectra in Fig. 5b based on an open-source MATLAB script-based software, DRTtools41. The DRT profile of Zn||Zn0.25V2O5·nH2O full batteries, as depicted in Fig. 5c, was provided with three prominent local maxima, all of which contributed to the total polarization resistance of the cell42. Similar to Zn | |Zn symmetric cells (Supplementary Fig. 19), the charge transfer resistance on the negative electrode (Rc1) and the positive electrode (Rct2) of the two cases showed mild differences except for the slightly dropped polarization of Zn|PZS|Zn0.25V2O5·nH2O, supporting no detectable adverse effect of the ppm-scale additive to this specific storage system43,44. As depicted in Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 20, Zn|PZS|Zn0.25V2O5·nH2O facilitated a capacity of 371.7 mAh g-1 at 0.2 A g−1 with a capacity retention of 87.6% (retained 325.6 mAh g−1 after the current reset). In contrast, the capacity retention of the battery operated in BZS decreased to 70.6%, maintaining 275.5 mAh g-1 out of 389.7 mAh g−1. As shown in Fig. 5e, additional ppm-scale PPGA further benefited to 1000 cycles at 1.2 A g−1 with capacity retention of 77.8%, outperforming the counterpart that was subjected to irreversible capacity loss and short circuit after 300 cycles45. We further proposed an ampere-hour-scale Zn|PZS|Zn0.25V2O5·nH2O pouch cell with a low N(100 µm, 58.8 mAh cm−2)/P(16.5 mAh cm−2) ratio of 3.5:1 and electrolyte/capacity (E/C) ratio of around 8 mL Ah-1 by using the designed PZS (Supplementary Fig. 21). As shown in the long-term cycling performance in Fig. 5f and galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) curves in Fig. 5g, the practical cell configuration sustained an Ah-level capacity at 200 mA g−1 for 250 cycles with an average CE of 99.9% and negligible capacity loss, though a trace amount of V2O5 was added to the electrolyte to compensate for the dissolution of positive electrode materials.

a CV, b EIS spectra, c DRT spectra, d Rate and e cycling performance of Zn | |Zn0.25V2O5 coin cell based on BZS and PZS; f its long-term cycling performance, and g selected GCD curves. Insets in f denote the representative voltage profile of the pouch cell. All tests were performed at around 25 oC. The cutoff voltage was 1.6 V. The positive electrode mass loading is around 1.5 mg cm−2 for coin cells and 60 mg cm-2 for the pouch cell.

As a promising solution for large-scale storage applications with cost efficiency, competitive theoretical energy density and safety, zinc-based flow batteries have attracted widespread attention46. However, the system intensively suffers from the asymmetric distribution of active species and charges, mutually reinforcing by the growth of zinc dendrites47,48,49. To further validate the effectiveness and applicability of a ppm-scale PPGA additive, we subsequently proposed an investigation on the aqueous zinc-based redox flow battery in regard to manipulating zinc flux in a more extensive system. Figure 6a depicts the general configuration of a Zn||Br2 flow battery, which consists of a current collector, a carbon felt electrode (CF, 2 × 2 cm2 in our case), and a membrane in-between and external anolyte/catholyte tanks that circulated by pumps to drive the redox reactions50. As expected, the PPGA additive (10 ppm) furnished the Zn||CF flow battery with 500 reversible cycles (CE closed to 100%) at 40 mA cm−2, 20 mAh cm−2, while the control sample barely functioned properly after 50 cycles (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 22). The corresponding voltage profile witnessed an irreversible Zn2+/Zn redox reaction in the control sample on account of increased deposition voltage on CF over time (Fig. 6c). The stable long-term cycling performance of Zn||Br2 flow batteries highlighted the significance of PPGA additive which brought about 800 cycles at 40 mA cm-2 with an average CE of 98% (Fig. 6d). By contrast, the same setup with the absence of PPGA fetched out with a fading capacity and CE after 50 cycles which was subjected to persistent dendrite growth and side effects, giving rise to short-circuit and polarization, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 23)51. The voltage profile demonstrated in the inset of Fig. 6d stressed the well-retained discharge capacity and minimized charge/discharge polarization by applying PPGA additive to the flow battery. The rate performance summarized in Fig. 6e further embodied that PPGA could promote a stable CE with insignificant capacity fading even at a high current density of up to 100 mA cm-2.

a Illustration of the studied redox flow battery; b Zn||CF flow batteries cycled at 40 mA cm−2, 20 mAh cm−2 and c corresponding voltage evolution over time; d Long-term cycling, and e CE under varying current densities of Zn||Br2 redox flow batteries. Insets in d show selected charge-discharge curves during the cycling process. We note that the battery tests were conducted at around 25 oC with a flow rate of 50 mL/min, a charge cutoff capacity of 20 mAh cm−2, and a discharge cutoff voltage of 0.8 V (for Zn||Br2 flow batteries) or −0.5 V (for Zn||CF flow batteries).

Discussion

Electrolyte additives offer a cost-efficient and secure option to regulate zinc deposition and refrain side reactions in mild acidic electrolytes of batteries. They are highly competitive to intricate negative electrode configuration and depth design of electrolytes. Instead of implementing a large dosage of electrolyte additive, we proposed a ppm-scale electrolyte additive, hydroxyphosphono-acetic acid, for durable zinc-ion batteries. The introduced PPGA, with a feeding amount down to 5 ppm, could effectively be adsorbed on the zinc surface and optimize Zn deposition, sparing the adverse effects of HER and dendrite growth, thereby enabling long-term cycling of nearly 1 year at 1 mA cm−2, 1 mAh cm−2, and 10 mA cm−2, 1 mAh cm−2 for the Zn|PZS|Zn symmetric cells. The improvement was demonstrated by an Ah-level Zn||Zn0.25V2O5·nH2O pouch cell, which successfully operated for 250 cycles without capacity fading. A Zn||Br2 redox flow system further verified the effectiveness of PPGA (10 ppm) by which the flow battery facilitated 800 cycles at 40 mA cm−2 with an average CE of 98%, profiting from controlled zinc chemistry and alleviated dendrite growth. The introduced strategy may shed light on the development of electrolyte additive engineering.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

Zn bromide (99%), zinc sulfate (AR), hydroxyphosphono-acetic acid (PPGA, 50% in H2O; also named as 2-hydroxy-2-phosphonoacetic acid; CAS No.: 23783-26-8), Vanadium(V) oxide (V2O5, 99%), Anhydrous zinc acetate (99.99%), Zinc bromide (ZnBr2, 99%), Znic chloride (ZnCl2, 98%), 1-ethyl-1-methylpyrrolidinium bromide (MEP, 99%), and 1-Methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (99%) were purchased from Aladdin. Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) and Ketjen black EC-300J were purchased from SOLVAY (Solef 1008) and Nouryon, respectively. All chemicals were used as received without further treatment. Hydrophilic Daramic membranes, ~900 µm thick, with an average pore size of around 0.1 µm and a porosity of about 58% (Polypore (Shanghai) Membrane Products Co., Ltd, China), were utilized as received. Glass fibers were purchased from Whatman, Cytiva (USA) with a lateral size of 12 mm and thickness of 260 µm. All electrolytes were prepared with deionized water.

Material and electrochemical characterizations

Zn0.25V2O5 was prepared as positive electrode materials. Specifically, 4 mmol V2O5 and 2.6 mmol anhydrous zinc acetate were dissolved in a mixture of H2O and acetate (94:6 % v/v) and subsequently transferred to a sealed Teflon vessel and heated to 200 oC for 72 h. The obtained precipitate was washed with water and acetone and dried at 60 oC for further use. FTIR measurement was carried out using a Perkin Elmer FT-IR spectrophotometer. Powder XRD patterns were conducted by a Rigaku Smartlab X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). XPS was performed on a PHI model 5802; the carbon spectrum (284.8 eV) was used as a reference for calibration. FEI Quanta 250 SEM and energy dispersive spectroscopy were used to study the morphology and elemental composition of the samples. CVs and EIS were collected on an electrochemical workstation (CHI 660E). EIS measurements were performed after assembling the batteries without additional treatment. The applied signal for EIS measurement was potentiostatic (single frequency) with an amplitude of 0.005 with a frequency range extended from 0.01 to 100,000 Hz until reaching a total of 74 data points for Zn||Zn0.25V2O5 full cells and 61 data points for Zn||Zn symmetric cells. The long-term stability and rate performance of batteries were obtained by the LAND battery testing system at around 25 oC. The LSV curves were obtained by sweeping from −1.25 V to 0 V with a scan rate of 5 mV/s and the CA measurement was conducted with an initial bias of −1.2 V. All electrochemical measurements were conducted in an ambient atmosphere without the use of chambers. The NMR measurement was conducted using the Bruker 300 MHz “AVANCE III HD” Nuclear Magnetic Resonance System (NMR-300), which was equipped with an auto-sampler.

Static battery assembly

The Zn||Zn symmetric coin cells were assembled by two Zn foils (100 µm, 1 × 1 cm2) and an intermediate glassy fiber separator (Whatman, GF/C) with the addition of 60 µl electrolyte. 2 mol L−1 ZnSO4 electrolyte (BZS) and the same electrolyte with an additional 5 ppm of PPGA (PZS) resulted in water-to-solute ratios of 10.76747 and 10.76687, respectively. Zn||ZnVO coin cells followed a similar procedure while the positive electrode was Zn0.25V2O5 positive electrode which was prepared by a mixture of Zn0.25V2O5, Ketjen black, and PVDF with a mass ratio of 7:2:1, following by the doctor blade coating method to reach a mass loading of around 1.5 mg cm-2 (single side coating). The used case and spring were stainless steel. The Zn0.25V2O5 pouch cell was an amplified version of the coin cell. Specifically, the Zn0.25V2O5 positive electrode (~ 60 mg cm-2) and Zn negative electrode were both shaped to 10 cm × 10 cm and assembled with a slightly larger separator (10.4 cm × 10.4 cm) and a suitable amount of PZS electrolyte (around 15 mL), subjected to Al packaging bag. An automated vacuum sealing machine (Wuhan Geruisi New Energy Co. Ltd) was used for capsulation, followed by constant pressure from two piled plastic plates to remove excess electrolytes and ensure high sealability. The assembled pouch cell was left to set for 10 h and cycled 5 times at 1 C (200 mA g−1) to fully wet the thick electrodes and release the H2 gas caused by corrosion reactions via opening the packing film, next to re-sealing and the formal test.

Flow battery performance

The zinc-based flow battery was assembled by sandwiching a porous polyolefin membrane (Daramic) between two carbon felt (CF) electrodes clamped by two graphite plates. The active area of the electrode is 2 × 2 cm2. For Zn||Br2 flow batteries, the anolyte contains 2 mol L−1 ZnBr2 and 3 mol L−1 KCl. For the batteries with PPGA, an additional 10 ppm of PPGA was added to the anolyte taking into account the varying surface area of the positive electrodes in flow batteries and coin cells. The catholyte requires a bromine complexing agent to slow down the diffusion of corrosive bromine, and 0.4 mol L−1 MEP was added. Those different electrolytes in the anolyte and catholyte were used to flow-pass the batteries. The batteries were operated at a constant current density and the charge process was controlled by the designated capacity. The discharge process ended with a cut-off voltage of 0.8 V. The Zn||CF flow battery assembly method is the same as the Zn||Br2 flow battery, except that the positive electrode used a Zn plate attached to CF. The anolyte and catholyte were identical, containing 2 mol L−1 ZnBr2 and 3 mol L−1 KCl. All the battery performance tests were conducted by CT3001A, LAND Battery Testing System.

Method of theoretical calculations

The calculation of crystal size was determined using the Scherrer equation, expressed as \(\tau=\frac{K\lambda }{\beta \cos \theta }\), where \(\tau\) is the mean size of the measured crystals, \(K\) is a dimensionless shape factor (typically equals to 0.9), \(\lambda\) is the X-ray wavelength (1.5406 Å), \(\beta\) is the line broadening at half the maximum intensity (FWHM), \(\theta\) is the Bragg angle38. The Dmol3 mode within a numerical atom-centered basis function framework was adopted for the first-principles calculations based on the density functional theory (DFT). The electronic exchange-correlation interactions were resolved by the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) method. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) method with PBE formulation was used for the structural optimization. DFT semi-core pseudopotentials were chosen for the core treatment with relativistic effects, which replaced the core electrons with a single effective potential. The adsorption energy \({E}_{{ads}}\) was evaluated through the equation: \({E}_{{ads}}={E}_{{ensemble}}-{E}_{{absorbent}}-{E}_{{adsorbate}}\) where the subscript denotes either the energy of absorbent, adsorbate, or the whole system after adsorption52. Multiwfn was used for figure demonstration53.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are presented in the manuscript and Supplementary Information or are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data used in this study are also available in the Science Data Bank database at https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.18060.

References

Ji, X. & Nazar, L. F. Best practices for zinc metal batteries. Nat. Sustain. 7, 98–99 (2024).

Wang, S. et al. Conversion‐type organic‐inorganic tin‐based perovskite cathodes for durable aqueous zinc‐iodine batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2300922 (2023).

Zheng, X. et al. Constructing robust heterostructured interface for anode-free zinc batteries with ultrahigh capacities. Nat. Commun. 14, 76 (2023).

Liu, S. et al. From room temperature to harsh temperature applications: fundamentals and perspectives on electrolytes in zinc metal batteries. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn5097 (2022).

Lin, D. & Li, Y. Recent advances of aqueous rechargeable zinc-iodine batteries: challenges, solutions, and prospects. Adv. Mater. 34, e2108856 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Perovskite cathodes for aqueous and organic iodine batteries operating under one and two electrons redox modes. Adv. Mater. 36, e2304557 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Halide exchange in perovskites enables bromine/iodine hybrid cathodes for highly durable zinc ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, e2401924 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Sulfolane-containing aqueous electrolyte solutions for producing efficient ampere-hour-level zinc metal battery pouch cells. Nat. Commun. 14, 1828 (2023).

Dong, N., Zhang, F. & Pan, H. Towards the practical application of zn metal anodes for mild aqueous rechargeable Zn batteries. Chem. Sci. 13, 8243–8252 (2022).

Zhou, L. et al. Unshared pair electrons of zincophilic lewis base enable long-life Zn anodes under “three high” conditions. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202208051 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. A metal-organic framework host for highly reversible dendrite-free zinc metal anodes. Joule 3, 1289–1300 (2019).

Guo, N. et al. A review on 3D zinc anodes for zinc ion batteries. Small Methods 6, e2200597 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. An asymmetric electrolyte to simultaneously meet contradictory requirements of anode and cathode. Nat. Commun. 14, 2925 (2023).

Zeng, Y. et al. Dendrite-free zinc deposition induced by multifunctional CNT frameworks for stable flexible Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 31, e1903675 (2019).

Huang, C. et al. Self‐healing SeO2 additives enable zinc metal reversibility in aqueous ZnSO4 electrolytes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2112091 (2022).

Zhao, K. et al. Boosting the kinetics and stability of Zn anodes in aqueous electrolytes with supramolecular cyclodextrin additives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 11129–11137 (2022).

Zong, Y. et al. Functionalized separator strategies toward advanced aqueous zinc‐ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2300403 (2023).

Zhao, Y. et al. Tailoring grain boundary stability of zinc-titanium alloy for long-lasting aqueous zinc batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 7080 (2023).

Wu, F. et al. Achieving highly reversible zinc anodes via N, N-dimethylacetamide enabled Zn-ion solvation regulation. Small 18, e2202363 (2022).

Cao, L. et al. Solvation structure design for aqueous Zn metal batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 21404–21409 (2020).

Burkitbayev, M. & Urakaev, F. K. Temperature dependence of sulfur solubility in dimethyl sulfoxide and changes in concentration of supersaturated sulfur solutions at 25. C. J. Mol. Liq. 316, 113886 (2020).

Jones, W. J. & Musulin, B. Solubility of iodine in dimethylsulfoxide. J. Chem. Eng. Data 7, 294 (1962).

Ma, J., Li, H., He, Z. R., Yang, H. & Fu, M. W. Complex unloading behavior of titanium alloy in cold and thermal-mechanical working. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 233, 107672 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. Long-life aqueous Zn-I2 battery enabled by a low-cost multifunctional zeolite membrane separator. Nano Lett 22, 2538–2546 (2022).

Guo, X. et al. Alleviation of dendrite formation on zinc anodes via electrolyte additives. ACS Energy Lett 6, 395–403 (2021).

Chen, R. et al. Trace amounts of triple-functional additives enable reversible aqueous zinc-ion batteries from a comprehensive perspective. Nano-Micro Lett 15, 81 (2023).

Geng, Y. et al. Electrolyte additive engineering for aqueous Zn ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 51, 733–755 (2022).

Yang, F. et al. Understanding H2 evolution electrochemistry to minimize solvated water impact on zinc-anode performance. Adv. Mater. 34, e2206754 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Controlled deposition of zinc-metal anodes via selectively polarized ferroelectric polymers. Adv. Mater. 34, e2106937 (2022).

Zhang, J. S. et al. Adsorption of kinetic inhibitors-on clathrate-hydrates. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 17418–17420 (2009).

Fan, C., Kan, A. T., Fu, G., Tomson, M. B. & Shen, D. Quantitative evaluation of calcium sulfate precipitation kinetics in the presence and absence of scale inhibitors. SPE J. 15, 977–988 (2010).

Zeino, A., Albakri, M., Khaled, M. & Zarzour, M. Comparative study of the synergistic effect of ATMP and DTPMPA on CaSO4 scale inhibition and evaluation of induction time effect. J. Water Process Eng. 21, 1–8 (2018).

Gao, Y., Fan, L., Ward, L. & Liu, Z. Synthesis of polyaspartic acid derivative and evaluation of its corrosion and scale inhibition performance in seawater utilization. Desalination 365, 220–226 (2015).

Yi, C. & Zhu, B. Corrosion inhibition effect of 2-hydroxy phosphonoacetic acid and pyrophosfate on Q235 steel, electrochemical noise and EIS analysis. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 14, 6759–6772 (2019).

Zheng, Y. et al. Corrosion inhibition performance of composite based on chitosan derivative. J. Mol. Liq. 324, 114679(2021).

Mpelwa, M. & Tang, S. F. State of the art of synthetic threshold scale inhibitors for mineral scaling in the petroleum industry: a review. Pet. Sci. 16, 830–849 (2019).

Yu, Y. et al. Stabilizing Zn metal anode by interfacial self-assembled zincophilic metal-organic complex conversion layers. Energy Storage Mater 71, 103601 (2024).

Fatimah, S., Ragadhita, R., Husaeni, D. F. A. & Nandiyanto, A. B. D. How to calculate crystallite size from X-ray diffraction (XRD) using Scherrer method. Asian. J.S.E 2, 65–76 (2022).

Aldahhak, H. et al. Toward efficient toxic-gas detectors: exploring molecular interactions of sarin and dimethyl methylphosphonate with metal-centered phthalocyanine structures. J. Phys. Chem. C 124, 6090–6102 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. Quantifying asymmetric zinc deposition: a guide factor for designing durable zinc anodes. Adv. Mater. 36, e2406451 (2024).

Wan, T. H., Saccoccio, M., Chen, C. & Ciucci, F. Influence of the discretization methods on the distribution of relaxation times deconvolution: implementing radial basis functions with DRTtools. Electrochim. Acta 184, 483–499 (2015).

Soni, R. et al. Lithium-sulfur battery diagnostics through distribution of relaxation times analysis. Energy Storage Mater 51, 97–107 (2022).

Hong, H. et al. Metal-free eutectic electrolyte with weak hydrogen bonds for high-rate and ultra-stable ammonium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, e2308210 (2023).

Huld, F. T., Yu, Z. & Lou, F. Unravelling the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of silicon half cells with commercial loading. Energy Adv 2, 1176–1181 (2023).

Huang, C. et al. Amphoteric polymer strategy with buffer‐adsorption mechanism for long‐life aqueous zinc ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2315855 (2024).

Park, M., Ryu, J., Wang, W. & Cho, J. Material design and engineering of next-generation flow-battery technologies. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16080 (2016).

Xu, Z., Fan, Q., Li, Y., Wang, J. & Lund, P. D. Review of zinc dendrite formation in zinc bromine redox flow battery. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 127, 109838 (2020).

Yin, Y. & Li, X. Review and perspectives on anodes in rechargeable aqueous zinc-based batteries. Renewables 1, 622–637 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. High-energy-density aqueous zinc-based hybrid supercapacitor-battery with uniform zinc deposition achieved by multifunctional decoupled additive. Nano Energy 96, 107120 (2022).

Zhang, L., Feng, R., Wang, W. & Yu, G. Emerging chemistries and molecular designs for flow batteries. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 524–543 (2022).

Rana, M. et al. Scientific issues of zinc-bromine flow batteries and mitigation strategies. Exploration 3, 20220073 (2023).

Zhu, H. & Kee, R. J. Computational modeling of sodium-iodine secondary batteries. Electrochim. Acta 219, 70–81 (2016).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Acknowledgements

C.Z. acknowledges the support from the National Key R&D Program of China under Project 2019YFA0705104, the grants from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. R5019−22, Project No. CityU PDFS2122-1S05, and Project No. CityU 11214023), the Talent Recruitment Project of Guangdong Province (No. 2019QN01C883), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Project (JCYJ20220818102402004) and HIT-CityU Joint Laboratory on Zinc-based Batteries.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.X.W. and S.N.W. contributed equally to this work. S.X.W. and C.Z. designed the study. C.Z. supervised the experiments. S.X.W, S.N.W., Z.W., Y.W., D.Z., Z.C. conducted structural, electrochemical, and spectroscopic characterizations and analyzed the data. S.X.W. performed the theoretical calculations. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Roza Bouchal, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., Wang, S., Wei, Z. et al. A parts-per-million scale electrolyte additive for durable aqueous zinc batteries. Nat Commun 16, 1800 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56607-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56607-1

This article is cited by

-

Parallel adsorption of parts-per-million level additives for highly efficient aqueous zinc-ion battery

Science China Materials (2025)