Abstract

The interplay of electrons with a chiral medium has a diverse impact across science and technology, influencing drug separation, chemical reactions, and electronic transport1-30. In particular, electron-chirality interactions can significantly affect charge and spin transport in chiral conductors, making them highly appealing for spintronics. However, an atomistic mapping of different electron-chirality interactions remains elusive. Here, we find that helicene-based single-molecule junctions behave as a combined magnetic-diode and spin-valve device. This dual-functionality enables the identification of an atomic-scale coexistence of different electron-chirality interactions: the magnetic-diode behavior is attributed to an interaction between electron’s angular momentum in a chiral medium and magnetic fields, whereas the spin-valve functionality is ascribed to an interaction between the electron’s spin and a chiral medium. This work uncovers the coexistence of electron-chirality interactions at the atomic-scale, identifies their distinct properties, and demonstrates how integrating their functionalities can broaden of the available methods for spintronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The interactions between electronic angular momentum, whether in a spin or orbital form, and a chiral medium hold diverse fundamental and practical implications. For example, these interactions are directly associated with molecular recognition, charge transfer in biosystems, chemical reactions, drug purification, and, foremost, with electronic transport in chiral conductors across all relevant scales and dimensions, down to individual molecules1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. As a fundamental symmetry-related subject with broad impact, the details of these interactions have been subjected to extensive research1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51. However, an atomistic picture of the interplay between electronic angular momentum and a chiral medium remains elusive, along with its full potential for spintronic manipulations.

In the last two decades, a large set of phenomena related to electron transport and transfer in chiral conductors has been studied experimentally. The observed phenomena have been typically attributed to one of two general effects: the chiral-induced spin selectivity (CISS)1,5,6,7,8,9,12,14,15,19,20,21,22,23,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51 and the electrical magnetochiral anisotropy (EMCA, sometimes denoted as eMChA)2,3,4,10,11,13,16,17,18,21,23,24,43,47,49. In the former case (CISS; Fig. 1a), specifically in the context of electron transport, the magnetic moment of an electron moving in a chiral conductor interacts with the chiral system. Depending on the conductor’s chirality and the direction of the electron velocity, this interaction promotes the transport of electrons with one spin direction (either parallel or antiparallel to the velocity) and suppresses the transport of electrons with the opposite spin direction. Thus, for a given chirality and current direction, the electronic current is dominated by one spin population. In the latter case (EMCA; Fig. 1b) that to date has not been identified in atomic-scale systems, the angular momentum2,49 of an electron moving in a chiral system is affected by the chiral landscape. The interaction between the resulted angular momentum and an external magnetic field, parallel or antiparallel to the electron’s velocity, promotes or suppresses electron transport. In this case, the conductor’s resistance is decreased or increased by the EMCA effect depending on the chirality of the system, the current direction, and the external magnetic field orientation. The CISS effect is expected to be detected experimentally when time-reversal symmetry breaks, while for the EMCA effect this condition already holds47.

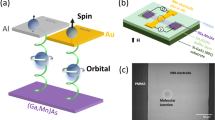

a Illustration of chiral-induced spin selectivity (CISS). b Illustration of electrical magnetochiral anisotropy (EMCA). Here, the helix indicates a chiral conductor, red circles - electrons (e), red arrows—spin (S), blue arrows—electron transport directions, black arrows—magnetic field (B) directions. c Illustration of a break-junction setup and a helicene molecular junction. d Histogram and an average of current in absolute values as a function of voltage (\(\left|I\right|\)–V curves) for Ni(Au)/M-helicene/Au junctions under +2 T magnetic field, parallel to the junction. Ni(Au) refers to a Ni electrode wet by Au. e The same under −2 T magnetic field antiparallel to the junction. f Average of absolute value of current as a function of voltage for Ni(Au)/M-helicene/Au junctions under parallel and antiparallel +2 T and −2 T magnetic fields. g–i The same as (d–f) but for Ni(Au)/P-helicene/Au junctions. The standard error of the current [\(({{\rm{standard}}}\; {{\rm{deviation}}})/\sqrt{{{\rm{\#}}}\; {{\rm{of}}}\; {{\rm{curves}}}}\)] in (d) to (i) is smaller than the curve width. j Asymmetry as a function of voltage magnitude for Ni(Au)/M-helicene/Au junctions under the mentioned opposite magnetic fields. Asymmetry is defined as \({{\rm{Asymmetry}}}=100\cdot [\left|I(+V)\right|-\left|I\left(-V\right)\right|]/[\left|I\left(+V\right)\right|+\left|I\left(-V\right)\right|]\). k The same as in (j), but for Ni(Au)/P-helicene/Au junctions. The number of examined molecular junctions (and corresponding I–V curves) in each case varies between 251 to 377.

In this work, we reveal the simultaneous occurrence of the EMCA and CISS effects at the atomic-scale and characterize their properties at the limit of quantum transport. Specifically, we find that single-molecule junctions based on helicene molecules behave as a merged magnetic-diode and spin-valve device, due to a coexistence of the EMCA and CISS effects. The distinct nature of these effects is unveiled by their different response to applied magnetic fields, and electrodes composed of metals with different spin-orbit coupling (SOC). We find no apparent coupling between the EMCA and CISS effects and identify the conditions in which their magnitude is equal. We uncover an unknown response of the EMCA effect to SOC, and the absence of a similar response for the CISS effect. This important observation can limit the range of relevant theoretical models for the two effects. Our work maps the different contributions that dominate the interplay between electrons and a chiral medium at the atomic scale. The found coexistence of the CISS and EMCA effects at this scale presents opportunities for a broader range of spintronic manipulations in miniaturized systems, leveraging the different nature of each effect.

We use single-molecule junctions prepared in a break-junction setup at 4.2 K (Fig. 1c52,53). The junctions include a Ni electrode as a source or drain for spin-polarized current, a counter electrode made of Au, Ag, or Cu, and an unprecedented 2,2’-dithiol-[6]helicene (helicene hereafter) as a chiral molecular bridge (see Supplementary Section 1 for synthesis and characterization, Figs. S1–S6, and Tables S1–S5). The choice of the molecule was motivated by the well-known affinity of thiol groups for the coinage metals and by the robust helical chirality of the helicene framework54. Before the molecules are introduced, the contact between the electrode tips is repeatedly broken and reformed in sub-atomic precision. This process wets the Ni tip with the softer metal of the counter electrode to have two atomic-scale apexes made of the softer metal52. Next, the helicene molecules are introduced into the cold junction by in-situ sublimation from a local source during repeated junction breaking and squeezing53. We use either the P-enantiomer of helicene with a clockwise helicity or the M-enantiomer with an anticlockwise helicity (Fig. 1, insets). The described junction fabrication and the following measurements are done in a cryogenic temperature and ultra-high vacuum conditions that minimize unwanted contaminations. See details in “Methods” and Supplementary Section 2.

Results

Current–voltage curves under magnetic fields, asymmetry, and magnetoconductance

Figure 1d–i presents histograms and average current in absolute values, as a function of applied voltage (\(\left|I\right|\)-V curves) measured for hundreds of molecular junction realizations. Before each measurement, the two electrode apexes are squeezed against each other and then stretched to reform a new molecular junction in order to sample the span of different molecular junction configurations. Separate sets of \(\left|I\right|\)-V measurements were performed for molecular junctions based on M (Fig. 1d, e) and P (Fig. 1g, h) enantiomers. During the measurements, a constant magnetic field of \(+\)2 or \(-\)2 Tesla (T) was applied to align the Ni magnetization parallel or antiparallel to the junction’s axis. Consequentially, a spin-polarized current is generated at a finite voltage with a dominant population of spins aligned either antiparallel or parallel to the junction’s axis. To have a better comparison between these cases, the average \(\left|{{\rm{I}}}\right|\)-V curves for opposite magnetic fields, are presented together in Fig. 1,f, i, for each enantiomer (refer to Figures S7–S13 for complementary information related to Fig. 1). Interestingly, the \(\left|{{\rm{I}}}\right|\)-V curves are asymmetric, revealing current rectification or diode-like behavior. Namely, the current magnitude is different for a positive and negative voltage. For a given enantiomer, the asymmetry is inverted when the magnetic field direction is reversed (blue versus red in Fig. 1f, i). Moreover, for a given magnetic field (e.g., blue curves in Fig. 1f, i), the asymmetry is inverted when opposite molecular chirality (P or M) is used. This is quantitatively summarized in Fig. 1j, k, by asymmetry histograms and average asymmetry as a function of voltage (see Fig. 1 caption for asymmetry definition). The observed inversion of asymmetry when opposite chirality or magnetic field direction are used rules out the possibility of an asymmetric junction structure as the source of asymmetry in the |I|–V curve. Thus, the origin of the diode-like behavior of the helicene junctions is clearly related to the application of magnetic fields and the molecule’s chirality.

CISS and EMCA in current–voltage curves and magnetoconductance

The identified current rectification (e.g., Fig. 2a, in polar I–V presentation) stands in contrast to the characteristics of I–V measurements reported in previous experiments related to the CISS effect across a wide range of systems. These systems include a chiral conducting medium positioned between ferromagnetic and non-ferromagnetic electrodes6,19,20,21,26,27,29. Irrespective of the diverse architectures and materials used, in all these cases the reported response of the I–V curves to opposite magnetization or chirality is symmetrical in the following sense. The current magnitude in one curve is always larger than that of the other curve, regardless of voltage polarity as illustrated in Fig. 2b. This behavior was attributed to the injection of spins with opposite orientations at positive and negative applied voltages55. We include in this definition also previously reported asymmetric I–V curves resulting from uneven voltage drops across an asymmetric junction structure, where the current magnitude may differ for opposite voltages. However, it consistently remains larger for a specific chirality and magnetic field direction when compared to their opposite counterpart6,29,56. In contrast to the findings related to the CISS effect, the EMCA effect induces a suppression of resistance for one voltage polarity and an enhancement in resistance for the opposite voltage polarity2,3,4. Specifically, for a given chirality and magnetic field orientation, the contribution to resistance (or conductance, which is 1/resistance) by the EMCA effect changes its sign, depending on the current direction. This is translated into current rectification and an asymmetric I–V curve11,24,47,49,57, as exemplified in Fig. 2c. However, also this behavior shows merely partial resemblance to our measurements (e.g., Fig. 2a, d).

a Measured average I–V curve for hundreds of Ni(Au)/M-helicene/Au junctions. Simulated I–V curve for the CISS effect (b), and the EMCA effect (c). For details about the model underlying (b,c), see Supplementary section 3. d Measured average I–V curve for hundreds of Ni(Au)/P-helicene/Au junctions. The standard error of the current in (a,d) is smaller than the curve width. e Average magnetoconductance (MC) (black) based on measured data from (a) for M-helicene junctions. The green curve represents a linear fit. f Symmetric component (black) of the MC in (e), and a linear fit (green). g Antisymmetric component (black) of the MC in (e), and a linear fit (green). h Average MC (black) based on measured data from (d) for P-helicene junctions. The green curve is not a fit to the data in (h), but a mirror inversion of the fit for the measured MC of the M-helicene junctions seen in (e). Note the agreement between the inverted curve based on data obtained in a set of experiments for the M-helicene junctions and the data obtained in independent set of experiments for the P-helicene junctions. The MC in (e) and (h) is obtained from I–V data above \(\pm\)100 mV for robust results. The number of examined molecular junctions in each case varies between 251 and 377.

To understand the observed I–V behavior for the helicene junctions, we turn to magnetoresistance (MC), defined as: \({{\rm{MC}}}=\left[G\uparrow (V)-G\downarrow (V)\right]/\left[G\uparrow \left(V\right)+G\downarrow (V)\right]\), where \({G}_{i}={I}_{i}/V\) is the conductance measured under positive (\({{\rm{i}}}=\uparrow\)) and negative (\({{\rm{i}}}=\downarrow\)) magnetic fields. Figure 2e, shows in black the MC obtained from the I–V curves in Fig. 2a for M-helicene junctions. The MC curve can be decomposed into symmetric \(\left.{{\rm{MC}}}(+V\, )+{{\rm{MC}}}(-V\, )\right)/2\)) and antisymmetric \(\left.{{\rm{MC}}}(+V)-{{\rm{MC}}}(-V)\right)/2\) components, presented in black in Fig. 2f and g, respectively. Ignoring the fine structure of the symmetric MC curves in Fig. 2f, we can find a linear fit (green) to this MC component. According to the MC definition, a symmetric MC implies an I–V curve with a current magnitude always larger for a positive magnetic field compared to the I–V curve for a negative magnetic field. In fact, using the MC definition, the fit in Fig. 2f can be produced by the I–V curves presented in Fig. 2b that illustrate the CISS response (see Supplementary Section 3 for the phenomenological model used to produce Fig. 2b). Therefore, the MC symmetrical response to magnetic field is a typical signature for the CISS effect. The antisymmetric MC component in Fig. 2g is also fitted to a linear function (green). In contrast to the above case, the antisymmetric MC component indicates for a positive magnetic field an I–V curve with a current magnitude smaller for one voltage polarity and higher for the other polarity, and vice versa for the opposite magnetic field. This description aligns with the behavior of the I–V curves shown in Fig. 2c that illustrate the EMCA response. These I–V curves are related to the fit in Fig. 2g through the MC definition (Supplementary Section 3), and the antisymmetric MC response to magnetic field is therefore associated with the EMCA effect. Since the sum of the green fits in Fig. 2f, g yields the fit to the total MC in Fig. 2e, the general behavior of the experimentally obtained MC in Fig. 2e can be explained by the contribution of both effects: the CISS accounts for the MC shift (finite MC intercept), while the EMCA introduces the MC tilting (non-zero MC slope), and the peculiar behavior of the measured I–V curves in Fig. 2a is an outcome of the concurrent contributions from the CISS (Fig. 2a) and EMCA (Fig. 2a) effects. Focusing on the I-V curves and the resulted MC for the P-helicene junctions presented in Fig. 2d and h, respectively, the green curve in Fig. 2h is not a fit to this graph. Interestingly, it is the linear fit seen in Fig. 2g yet with an inverted intercept and slope signs, revealing a remarkable agreement with the measured data for P-helicene junctions in evidently independent experiments. See Supplementary Section 3 for additional details, and a comparison of the symmetric and antisymmetric MC components for M- and P-helicene junctions. We note that the insensitivity of the symmetric MC component, associated here with the CISS effect, to the applied voltage is consistent with previous reports on the CISS effect19,20,56,58,59,60,61 (in most of these reports, the definition of spin polarization is equivalent to our definition of MC).

The influence of magnetic field magnitude

As mentioned, the EMCA effect arises in the presence of an external magnetic field. In contrast, the CISS effect is not expected to be influenced by such fields, except for a negligible influence from Zeeman splitting. Figure 3a–i presents the \(\left|I\right|\)-V curves, asymmetry, and MC in three different magnetic fields. Here, magnetic fields above 2 T were considered to ensure magnetization saturation even at the Ni atomic apex, and higher fields than 4 T were avoided due to expected contributions from high-order corrections to the EMCA effect3,7,24. While there are evident differences between the curves, to get quantitative information we first focus on the asymmetry at 1 V as a function of magnetic field as presented in Fig. 3j, which reveals a clear linear dependence. The asymmetry is proportional to the conductance difference between positive and negative voltage (Supplementary Section 4), which is expected to be linear and reduced to zero in the absence of magnetic field for the EMCA effect2,3. Applying linear fits (red) to the data at negative and positive magnetic field, yields similar slopes and intercepts within the measurement uncertainty listed in the caption of Fig. 3. This similarity allows us to consider the intercepts as reliable evidence of a finite EMCA at zero applied magnetic field. This behavior may originate from the presence of the Ni electrode, considering the Ni-induced finite magnetic field even when the external field is nullified, and other possible contributions. A detailed identification of the different mechanisms in which a ferromagnetic electrode can influence the EMCA effect requires further specialized studies. However, in the context of this work, we repeated the measurements without the Ni electrode for an ensemble of Au/M-helicene/Au junctions at \(\pm \,\) 2 T (Fig. S13). We found that the MC shift attributed to the CISS effect is essentially nullified in the absence of spin injection, as expected. Interestingly, comparing Fig. S13d to Fig. 1j, the asymmetry attributed to the EMCA effect is clearly reduced in the absence of the Ni electrode, corroborating the conclusion that the presence of the Ni electrode affects the EMCA effect.

a–c Average current (in absolute values) as a function of applied voltage for Ni(Ag)/M-helicene/Ag junctions at different applied magnetic fields. The standard error of the current is smaller than the curve width. d–f Average asymmetry as a function of applied voltage magnitude at different applied magnetic fields. g–i Average MC as a function of applied voltage at different magnitudes of magnetic field. The MC is obtained from I-V data at voltages above \(\pm\)50 mV. j Asymmetry at 1 V as a function of magnetic field. Red curves are linear fits with slopes and intercepts of: −2.2\(\pm\)0.1 %/T and −5.1\(\pm\)0.2 % for negative fields, and −2.0\(\pm\)0.2 %/T and −5.3\(\pm\)0.8 % for positive fields. k MC shift as a function of magnetic field magnitudes. The shift is obtained by the intercept of a linear fit to the MC data (see Supplementary section 5). The error bars for asymmetry and MC indicate the experimental uncertainty in view of the standard deviation of the measured currents. The number of examined molecular junctions in each case varies between 372 and 634. We study the response to magnetic field magnitudes using junctions based on Ag rather than Au. This choice is motivated by the tendency of Au to form atomic chains, which enhances result variability and complicates the analysis, especially when minor trends should be carefully detected. See Fig. S16 for corresponding \(\left|I\right|\)-V and asymmetry histograms.

Plotting in Fig. 3k the detected MC shift as a function of magnetic field magnitude reveals that it is not sensitive to the field, as expected for the CISS effect (see Supplementary Section 5). The asymmetry response to magnetic fields and the lack of detected influence of the field on the MC shift, support the earlier conclusion that the asymmetry is an outcome of the EMCA effect, while the observed MC shift is a consequence of the CISS effect. The zero MC at a positive voltage signifies a specific point where the influence of the EMCA and the CISS effects is equal and opposite, resulting in MC nullification (Supplementary Section 3). This point shifts to a lower voltage with an increase in magnetic field, as expected in view of the EMCA response to magnetic field strength. Interestingly, the linear response of the asymmetry to magnetic fields and the absence of any detected effect of magnetic fields on the MC shift suggest that within our experimental sensitivity there is no coupling between these manifestations of the CISS and EMCA effects.

The influence of metal electrodes with different spin-orbit coupling

Examining the response of the two effects to a common variable can further test their coexistence while providing insights into the distinct nature of each effect. Below, we consider the influence of different non-ferromagnetic electrodes made of Cu, Ag, and Au, having in mind their different SOC with increasing magnitude: Cu<Ag<Au62. In all three cases, the molecular junctions are characterized by a similar conductance around 5\(\cdot\)10−3 Go (Fig. S7). Figure 4a–c presents the measured average \(\left|I\right|\)-V curves for the three cases when applying parallel and antiparallel magnetic fields for M-helicene junctions (see Fig. S18 for a similar analysis of P-helicene junctions). The \(\left|I\right|\)-V response to magnetic fields varies among junctions based on the three different metals. Examining in Fig. 4d–f the resulting asymmetry, we find a monotonous increase in its magnitude. Figure 4j summarizes the total asymmetry (sum of positive and negative asymmetry magnitudes) at 1 V for the three different metals, where a larger asymmetry is observed for metals that exhibit a larger SOC. Focusing on MC in Fig. 4g–i, the increased tilt observed along the Cu, Ag, and Au series is another manifestation of the mentioned asymmetry trend. However, the MC shift presented in Fig. 4k is not sensitive to the metal type (see Supplementary Sections 5 and 6).

a–c Average current (in absolute values) as a function of applied voltage for Ni(X)/M-helicene/X junctions, where X is Cu (a), Ag (b), and Au (c). The standard error of the current is smaller than the curve width. d–f Average asymmetry as a function of applied voltage magnitude for the same junctions as in (a–c), respectively. g–i Average MC as a function of applied voltage for the same junctions as in (a–c), respectively. The MC is obtained from I–V data at voltages above \(\pm\)50 mV for Cu and Ag-based junctions, and \(\pm\)100 mV for Au-based junctions. j Total asymmetry at 1 V for junctions based on different metals. k MC shift for junctions based on different metals. The shift is obtained by the MC-axis intercept of a linear fit to the MC data (see Supplementary section 5). The red curve represents the average value. The number of examined molecular junctions in each case varies between 316 and 443. The error bars for asymmetry and MC indicate the experimental uncertainty. See Figs. S16a,d,g, Fig. S17, and Fig. 1d,e,j for \(\left|I\right|\)-V and asymmetry histograms for the three cases. See Fig. S18 and Fig. S19 for a similar analysis of P-helicene-based junctions.

The different response of asymmetry and MC shift to the metal type strengthen the conclusion that they stem from two different effects, in accordance with the accumulated indications presented above for the coexistence of the CISS and EMCA effects. The observed increase in asymmetry along the set of Cu, Ag, and Au provides the first systematic indication for a possible influence of SOC on the EMCA effect. This provides guidelines for a theoretical examination of the role of SOC in the EMCA effect, a dimension that is currently absent. The association of the CISS effect with MC shifts and the absence of a clear MC shift response in Fig. 4k (ignoring \(\sim\)1% lower shift for Cu) suggest that at the limit of the measurement uncertainty, the CISS effect is not sensitive to the electrode’s SOC or other variance between the used Au, Ag and Cu electrodes, in agreement with14,16, where similar metals were used. Note that the slightly lower response for the Cu-based electrode is observed both here and in refs. 14,16. This contrasts the observations reported in ref. 27, where the use of an Al substrate led to a significantly lower MC compared to an Au substrate. We can point to one difference in the mentioned comparative analyses: all the mentioned metals have distinct SOCs, but Cu, Ag, and Au have dominant s frontier orbitals at the Fermi energy, in contrast to Al with dominant p on top of s frontier orbitals. These may indicate the sensitive role of the substrate’s atomistic properties in determining the spin-dependent transport via metal-chiral molecule interfaces. Generally, if the CISS effect is indeed independent of the metal’s SOC as observed here, it narrows down the range of theoretical explanations pertinent to the CISS effect in similar systems.

Discussion

The clear indications for the EMCA effect in the examined single-molecule junctions raise a question regarding the conditions in which this effect can be observed at the atomic or molecular scale. Previous I–V measurements in chiral molecular junctions were typically performed as a function of magnetization orientation of one of the electrodes in order to explore the CISS effect. In these studies, a planar multi-molecular geometry or a scanning probe microscope configuration was usually adopted, where a flat ferromagnetic thin film was used as a central component of one of the electrodes (e.g., refs. 6,20,29). These structures have essentially a negligible intrinsic magnetic field, ignoring the film’s edges. In another example, the molecule was placed away from the ferromagnet26. Beyond a sizable magnetic field, a significant current density can also enhance the EMCA response49. While high current densities are not typical for multi-molecular junctions, they are expected for single-molecule junctions29. In fact, the combination of both: a sizable magnetic field, and a high current concentration, are met in our single-molecule junction experiments. In our setup, one of the electrodes is made of bulk Ni with an intrinsic magnetic field, and the junction is subjected to external fields of at least 2 T. Furthermore, the current concentration is around 107 A/cm2. Therefore, we expect that the EMCA effect will be seen in chiral single-molecule junctions with similar current concentrations and magnetic fields. We could not find indications for the reduction in the CISS response when the voltage is reduced to 50 mV. This may seemingly violate the constraints set by time-reversal symmetry. According to the latter, the CISS should be nullified within the linear response regime37,39,42,45,51. Yet, our observations agree well with former measurements of a finite CISS response at low applied voltages across ferromagnet-based two terminal devices63,64, thus providing guiding lines for theoretical descriptions of the CISS effect.

To conclude, in this work chiral single-molecule junctions are used to map the interplay of electrons and chirality at the atomic scale. This electron-chirality interaction dominates charge and spin transport in chiral materials. We uncover the simultaneous occurrence of the CISS and EMCA effects at the atomic scale, seen as a combined magnetic-diode-spin-valve spintronic functionality. Our analysis reveals no apparent coupling between these effects. Importantly, we find that metallic electrodes with different SOC affect the EMCA response, but not the CISS response. This work provides the first indication of the existence of the EMCA effect at the atomic scale and at the limit of quantum electronic transport. We further reveal an unknown SOC influence on the EMCA effect, offering a starting point for developing an atomistic EMCA theory, which is currently absent. The lack of substrate SOC influence on the CISS effect in electronic transport experiments can be used to narrow down the relevant atomistic mechanisms for this effect. Overall, the coexistence of the CISS and EMCA effects, both of comparable magnitude at the atomic scale, can expand the scope of spintronic functionalities in miniaturized systems by harnessing the unique characteristics of each effect.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

The experiments are done in a special version of a mechanical controllable break-junction set-up (Fig. 1c) as described in detail in ref. 52, and briefly here. The samples consist of one electrode made of a Ni wire terminated with a tip and a second counter electrode made of an Au, Ag, or Cu wire also ended with a tip (purity: 99.994% (Ni), 99.998% (Au), 99.997% (Ag), 99.9999% (Cu), diameter: 0.1 mm, length: 6 mm, manufacturer: Alfa Aesar). The two wires are attached to a flexible substrate composed of a phosphor-bronze plate (thickness: 1 mm) covered by an insulating Kapton film (thickness: 100 μm). Initially, the flexible substrate is bent, and subsequently, the two wires are attached to the bent substrate, with their tips oriented toward each other. Next, the substrate is relaxed to a flat configuration, and the tips are compressed together to form a macroscale contact. This break junction structure is introduced into a vacuum chamber and cooled to 4.2 K. To prepare an atomic-scale junction, the substrate is bent by a piezoelectric element (PI P-882 PICMA) that pushes the substrate at its center against two peripheral stoppers (Fig. 1c). As a result, the tips are pulled apart, and the contact cross-section is gradually reduced until a junction with a single-atom diameter neck is formed between the electrodes. Further extension leads to junction rupture. A fresh atomic junction can be prepared by relaxing the substrate, such that the electrode tips are pressed against each other to establish a multiatomic junction, after which the electrodes are pulled apart again to restore a single-atom junction. This break-make cycle can be iterated thousands of times such that the Ni electrode is wet by the softer metal of the counter electrode. After characterization of the bimetallic junction (Fig. S7a–c) to verify that the formed junction has now a typical conductance of a bare Cu, Ag, or Au junction as explained in ref. 52, the target molecules are introduced (See Supplementary Section 1 for details about the synthesis and characterization of the target molecules). We use a heated local molecular source to sublimate the target molecules into the cold junction, while repeating the break-make cycles. Once the typical conductance of the junction is altered (indicating the presence of molecules in the junction), the sublimation is stopped. Different molecular junctions are prepared by squeezing the electrodes to have a contact with a conductance of \(\sim\)20 \({G}_{0}\) followed by elongation of the contact up to rupture and the insertion of individual molecules between the electrodes. Repeating this procedure yields ensembles of molecular junctions with a variety of different geometries.

Conductance–displacement measurements

Conductance measurements as a function of elongation that provide the conductance histograms seen in Fig. S7 are done in the following way52. The junction is elongated at a rate of 20–40 Hz, while the conductance of the junction is measured simultaneously. The junction is biased with a fixed voltage provided by a DAQ card (NI-PCI6221) that is divided by 10 (by a homemade divider) to increase the signal-to-noise ratio. The resulting current across the junction is amplified by a current preamplifier (Femto amplifier DLPCA 200) and recorded by the DAQ card at a sampling rate of 50–200 kHz. The obtained current values are divided by the applied voltage values to extract the conductance. The interelectrode displacement is found by the exponential dependence of tunneling currents on the separation between the electrodes. The piezoelectric element that is used to bend the sample is driven by the same DAQ card connected to a piezo driver (Piezomechanik SVR 150/1).

Current–voltage measurements

The procedure for adjusting the junction before measuring current as a function of voltage (I–V measurement) is automated and based on the junction’s stability over a specific time interval. A junction is formed by increasing the interelectrode distance until the conductance drops below the lowest conductance of the bare metal junction. At this point, the interelectrode distance is fixed, and the current is recorded for 1 s. If the conductance variations during this time interval remain below 1 × 10−3 \({G}_{0}\) (\({G}_{0}\)≅1/12.9 (kΩ)−1 is the conductance quantum), an I–V measurement is conducted. However, if the conductance varies beyond 1 × 10−3 \({G}_{0}\) or the junction breaks during the measurement, the junction is reformed. Following this procedure, the junction is broken and reformed up to \(\sim\)20 \({G}_{0}\) to promote sampling of the span of junction structures. The I–V measurement itself is done as follows. Once a molecular junction is formed (typically within a conductance range of 1\(\cdot\)10−3 \({G}_{0}\) and 8\(\cdot\)10−3 \({G}_{0}\)), a variable bias voltage is applied across the junction from the mentioned DAC card and divider. The voltage is swept at a rate of 0.5 V/s, while the current is measured as mentioned above. During repeated I–V measurements on different molecular junction realizations, a constant magnetic field is applied using a superconducting magnet (\(\le\)9 T) that provides a magnetic field parallel or antiparallel to the sample wire.

Magnetic field application

A superconducting solenoid (American Magnetics) applies a constant magnetic field. The studied break junction is located at the solenoid’s center with its axis aligned to that of the solenoid. To avoid magnetostriction, we form hundreds of molecular junctions and perform the I–V measurements under a chosen fixed magnetic field. Before transitioning to the next measurement session at a different magnetic field, the interelectrode distance is increased to keep the junction broken while the magnetic field is altered to set a new fixed field. This procedure is done to avoid possible uncontrolled squeezing of the two electrodes against each other due to magnetostriction, which could otherwise modify the Ni(M) (M = Au, Ag, or Cu) electrode structure. The subsequent measurement session is thus conducted under a newly fixed magnetic field.

Data availability

Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Ray, K., Ananthavel, S. P., Waldeck, D. H. & Naaman, R. Asymmetric scattering of polarized electrons by organized organic films of chiral molecules. Science 283, 814–816 (1999).

Rikken, G. L. J. A., Fölling, J. & Wyder, P. Electrical magnetochiral anisotropy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 236602 (2001).

Krstić, V., Roth, S., Burghard, M., Kern, K. & Rikken, G. L. Magneto-chiral anisotropy in charge transport through single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Chem. Phys. 117, 11315–11319 (2002).

Rikken, G. L. J. A. & Wyder, P. Magnetoelectric anisotropy in diffusive transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 016601 (2005).

Göhler, B. et al. Spin selectivity in electron transmission through self-assembled monolayers of double-stranded DNA. Science 331, 894–897 (2011).

Xie, Z. et al. Spin specific electron conduction through DNA oligomers. Nano Lett. 11, 4652–4655 (2011).

Pop, F., Auban-Senzier, P., Canadell, E., Rikken, G. L. J. A. & Avarvari, N. Electrical magnetochiral anisotropy in a bulk chiral molecular conductor. Nat. Commun. 5, 3757 (2014).

Mtangi, W., Kiran, V., Fontanesi, C. & Naaman, R. Role of the electron spin polarization in water splitting. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 4916–4922 (2015).

Aragonès, A. C. et al. Measuring the spin-polarization power of a single chiral molecule. Small 13, 1602519 (2017).

Qin, F. et al. Superconductivity in a chiral nanotube. Nat. Commun. 8, 14465 (2017).

Wakatsuki, R. et al. Nonreciprocal charge transport in noncentrosymmetric superconductors. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602390 (2017).

Abendroth, J. M. et al. Analyzing spin selectivity in DNA-mediated charge transfer via fluorescence microscopy. ACS Nano 11, 7516–7526 (2017).

Yokouchi, T. et al. Electrical magnetochiral effect induced by chiral spin fluctuations. Nat. Commun. 8, 866 (2017).

Kettner, M. et al. Chirality-dependent electron spin filtering by molecular monolayers of helicenes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 2025–2030 (2018).

Al-Bustami, H. et al. Single nanoparticle magnetic spin memristor. Small 14, 1801249 (2018).

Tokura, Y. & Nagaosa, N. Nonreciprocal responses from non-centrosymmetric quantum materials. Nat. Commun. 9, 3740 (2018).

Aoki, R., Kousaka, T. & Togawa, Y. Anomalous nonreciprocal electrical transport on chiral magnetic order. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 057206 (2019).

Rikken, G. L. & Avarvari, N. Strong electrical magnetochiral anisotropy in tellurium. Phys. Rev. B. 99, 245153 (2019).

Lu, H. et al. Spin-dependent charge transport through 2D chiral hybrid lead-iodide perovskites. Sci. Adv. 5, eaay0571 (2019).

Kulkarni, C. et al. Highly efficient and tunable filtering of electrons’ spin by supramolecular chirality of nanofiber‐based materials. Adv. Mater. 32, 1904965 (2020).

Inui, A. et al. Chirality-induced spin-polarized state of a chiral crystal CrNb3S6. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 166602 (2020).

Kim, Y.-H. et al. Chiral-induced spin selectivity enables a room-temperature spin light-emitting diode. Science 371, 1129–1133 (2021).

Inui, A. et al. Chirality-induced spin polarization over macroscopic distances in chiral disilicide crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 126602 (2021).

Guo, C. et al. Switchable chiral transport in charge-ordered kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Nature 611, 461–466 (2022).

Nakajima, R. et al. spin polarization and a pair of antiparallel spins in a chiral superconductor. Nature 613, 479–484 (2023).

Yang, C. et al. Real-time monitoring of reaction stereochemistry through single-molecule observations of chirality-induced spin selectivity. Nat. Chem. 15, 972 (2023).

Adhikari, Y. et al. Interplay of structural chirality, electron spin and topological orbital in chiral molecular spin valves. Nat. Commun. 14, 5163 (2023).

Hannah, H. J. et al. Direct observation of chirality-induced spin selectivity in electron donor–acceptor molecules. Science 382, 197–201 (2023).

Safari, M. R., Matthes, F., Schneider, C. M., Ernst, K. H. & Bürgler, D. E. Spin‐selective electron transport through single chiral molecules. Small, 20 2308233 (2023).

Liang, Y. et al. Enhancement of electrocatalytic oxygen evolution by chiral molecular functionalization of hybrid 2D electrodes. Nat. Commun. 13, 3356 (2022).

Galperin, M. & Nitzan, A. Current-induced light emission and light-induced current in molecular-tunneling junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 206802 (2005).

Yeganeh, S., Ratner, M. A., Medina, E. & Mujica, V. Chiral electron transport: scattering through helical potentials. J. Chem. Phys. 131, 014707 (2009).

Guo, A. M. & Sun, Q. Spin-selective transport of electrons in DNA double helix. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 218102 (2012).

Gutierrez, R., Díaz, E., Naaman, R. & Cuniberti, G. Spin-selective transport through helical molecular systems. Phys. Rev. B 85, 081404R (2012).

Gersten, J., Kaasbjerg, K. & Nitzan, A. Induced spin filtering in electron transmission through chiral molecular layers adsorbed on metals with strong spin-orbit coupling. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 114111 (2013).

Maslyuk, V. V., Gutierrez, R., Dianat, A., Mujica, V. & Cuniberti, G. J. Enhanced magnetoresistance chiral molecular junctions.Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 5453–5459 (2018).

Yang, X., van der Wal, C. H. & van Wees, B. J. Spin-dependent electron transmission model for chiral molecules in mesoscopic devices. Phys. Rev. B 99, 024418 (2019).

Michaeli, K. & Naaman, R. Origin of spin-dependent tunneling through chiral molecules. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 17043–17048 (2019).

Dalum, S. & Hedegård, P. Theory of chiral induced spin selectivity. Nano Lett. 19, 5253–5259 (2019).

Fransson, J. Chirality-induced spin selectivity: the role of electron correlations. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 7126–7132 (2019).

Zöllner, M. S., Saghatchi, A., Mujica, V. & Herrmann, C. Influence of electronic structure modeling and junction structure on first-principles chiral induced spin selectivity. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 16, 7357–7371 (2020).

Liu, Y., Xiao, J., Koo, J. & Yan, B. Chirality-driven topological electronic structure of DNA-like materials. Nat. Mater. 20, 638–644 (2021).

Alwan, S. & Dubi, Y. Spinterface origin chirality-induced spin-selectivity effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 14235 (2021).

Fransson, J. Charge and spin dynamics and enantioselectivity in chiral molecules. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 808–814 (2022).

Evers, F. et al. Theory of chirality induced spin selectivity: progress and challenges. Adv. Mater. 34, 2106629 (2022).

Wolf, Y., Liu, Y., Xiao, J., Park, N. & Yan, B. Unusual spin polarization in the chirality-induced spin selectivity. ACS Nano 16, 18601 (2022).

Zhao, Y., Zhang, K., Xiao, J., Sun, K. & Yan, B. Magnetochiral charge pumping due to charge trapping and skin effect in chirality induced spin selectivity. Nat. Commun. 16, 37 (2025).

Naskar, S., Mujica, V. & Herrmann, C. Chiral-induced spin selectivity and non-equilibrium spin accumulation in molecules and interfaces: a first-principles study. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 694–701 (2023).

Rikken, G. L. J. A. & Avarvari, N. Comparing electrical magnetochiral anisotropy and chirality-induced spin selectivity. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 9727–9731 (2023).

Dednam, W. et al. A group-theoretic approach to the origin of chirality-induced spin-selectivity in nonmagnetic molecular junctions. ACS Nano 17, 6452–6465 (2023).

van Ruitenbeek, J. M., Korytár, R. & Evers, F. Chirality-controlled spin scattering through quantum interference. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 024710 (2023).

Singh, A. K., Chakrabarti, S., Vilan, A., Smogunov, A. & Tal, O. Electrically controlled bimetallic junctions for atomic-scale electronics. Nano Lett. 23, 7775–7781 (2023).

Yelin, T. et al. Conductance saturation in a series of highly transmitting molecular junctions. Nat. Mater. 15, 444–449 (2016).

Barroso, J. et al. Revisiting the racemization mechanism of helicenes. Chem. Commun. 54, 188–191 (2018).

Naaman, R., Paltiel, Y. & Waldeck, D. H. A perspective on chiral molecules and the spin selectivity effect. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 3660 – 3666 (2020).

Ko, C. H. et al. Electron spin polarization and rectification driven by chiral perylene diimide-based nanodonuts. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 10271–10277 (2023).

Yan, B. Structural Chirality and Electronic Chirality in Quantum Materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 54, 97–115 (2024).

Kiran, V. et al. Helicenes—a new class of organic spin filter. Adv. Mater. 28, 1957–1962 (2016).

Al-Bustami, H. et al. Atomic and molecular layer deposition of chiral thin films showing up to 99% spin selective transport. Nano Lett. 22, 5022–5028 (2022).

Qian, Q. et al. Chiral molecular intercalation superlattices. Nature 606, 902 (2022).

Giaconi, N. et al. Spin polarized current in chiral organic radical monolayers. J. Mater. Chem. C. 12, 10029–10035 (2024).

Manchon, A. & Belabbes, A. Spin-orbitronics at transition metal interfaces. Solid State Phys. 68, 1–89 (2017).

Liu, T. et al. Linear and nonlinear two-terminal spin-valve effect from chirality-induced spin selectivity. ACS Nano 14, 15983–15991 (2020).

Hossain, M. A. et al. Transverse magnetoconductance in two-terminal chiral spin-selective devices. Nanoscale Horiz. 8, 320–330 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank the following scientists (listed alphabetically) for fruitful discussions and comments: Y. Dubi, F. Evers, P. Hedegård, R. Korytár, L. Kronik, R. Naaman, A. Nitzan, G. L. J. A Rikken, S. Tirion, J. M. van Ruitenbeek, B. J. van Wees, L. Venkataraman, and B. Yan. This work was supported in France by the CNRS, the University of Angers, the RFI LUMOMAT and the French National Agency for Research (ANR) project SECRETS (ANR PRC 20-CE06-0023-01). O.T. acknowledges the support of the European Research Council (Grant 864008), the Israeli Science Foundation (Grant 2129/23), funding by the Harold Perlman family, and research grants from Dana and Yossie Hollander.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.S., O.T., and N.A. designed the project. K.M., M.M.T., and A.H. performed the chemical synthesis, purification, and characterization of the compounds under the supervision of N.A. N.V. performed the chiral HPLC separation. A.K.S. fabricated the studied atomic and molecular junctions and conducted the experiments under the supervision of O.T. Experimental data analysis and model development were carried out by A.K.S., under the supervision of O.T. and N.A. A.K.S., N.A., and O.T. wrote the first draft with input from all other authors. A.K.S., N.A., and O.T. reviewed and edited the final draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jan van Ruitenbeek, Peng Xiong, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, AK., Martin, K., Mastropasqua Talamo, M. et al. Single-molecule junctions map the interplay between electrons and chirality. Nat Commun 16, 1759 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56718-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56718-9

This article is cited by

-

Quantum correlation behaviour in single-molecule junctions

Nature Reviews Physics (2025)