Abstract

Superconducting domes, ubiquitous across a variety of quantum materials, are often understood as a window in which pairing is favored, opened by the fluctuations of competing orders. Yet, the understanding of how such a window closes is missing. Here, we show that inelastic neutron scattering, by quantifying a length scale associated with the dipoles correlation, ℓ0, addresses this issue. We find that, within the experimental precision, the end of the superconducting dome coincides with the end of a highly polarizable state (in which ℓ0 is longer than the interatomic distance). Thus, the superconducting dome is driven by the competition between the increase in the density of states and the inevitable collapse of the quantum paraelectric phase. This is compatible with a crucial role played by the soft ferroelectric mode in driving superconductivity. Such a scenario may also be at work in other quantum paraelectric materials, either bulk or at interfaces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In many superconducting materials such as cuprates1, pnictides2, heavy fermions3, doped band insulators4, and oxide5 or graphene6 heterostructures, the superconducting transition temperature (Tc) displays a dome shape as a function of the doping. Identifying the mechanisms giving rise to these domes is the subject of intense debates.

Among superconducting domes, the case of doped SrTiO3 is unique (see refs. 7,8 for reviews). In bulk crystals, the superconducting dome starts at a carrier concentration as low as n ≃ 5 × 1017 cm−3 for oxygen reduced samples9,10, spans over more than three orders of magnitude and ends at n ≃ 1021 cm−3, irrespective of the dopant identity11,12. This corresponds to a doping level of about 5%, an extremely low doping level compared with the threshold of superconductivity in many other materials. Moreover, by contrast with other families, the parent compound is not magnetic but is an incipient ferroelectric, the so-called quantum paraelectric phase. This state, characterized by a large dielectric constant ϵ ≈ 2 × 10413, is driven by the softening of the zone centered transverse optical (TO) phonon mode that hybridizes with the transverse acoustic (TA) phonon mode at low temperature14,15,16,17.

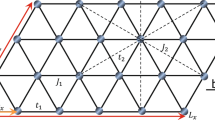

Recently, it has been suggested that the coupling of electrons with ferroelectric fluctuations can lead to superconducting pairing, in particular down to a very low carrier density. This coupling can take either the form of quadratic coupling18,19,20 or the form of a Rashba type electron-TO mode coupling10,21,22. In these theories, the attractive pairing mechanism is static with an amplitude set by kF, the Fermi wave-vector and ℓ0, the dipolar correlation length. ℓ0 is given by the TO dispersion energy (E) satisfying in the parent compound14,15 :

where ℓ0=\(\frac{{v}_{TO}}{{\omega }_{TO}}\) with ωTO and vTO the energy and velocity of the TO mode at the zone center. In doped polar materials, ℓ0 represents the radius of local electric dipoles formed around defects23,24. In highly polarizable crystals, such as quantum paraelectrics, ℓ0 can extend remarkably, reaching a few nanometers. Defects cooperate via dipolar interactions over long distances to generate mesoscopic dipoles. This cooperative behavior can lead to the percolation of dipoles and induce a ferroelectric ground state, as observed in Sr1−xCaxTiO324.

Here, we present the first systematic study of the dispersion of the soft ferroelectric phonon mode in electron doped SrTi1−xNbxO3 and Sr1−xLaxTiO3. Using inelastic neutron scattering (INS), a probe that allows to determine ℓ0, we track its decrease with electron doping as a result of the hardening of the TO-mode, the decrease of the velocity of the TO mode, and the breakdown of the TO/TA hybridization. Comparing ℓ0 and kF leads to a qualitative picture of the superconducting dome of SrTiO3. The increase in carrier density has opposite consequences for kF and for ℓ0. The former increases, while the latter decreases. When carrier density attains a threshold value (≃1021 cm−3), ℓ0 saturates to a value comparable to the interatomic distance and concomitantly, superconductivity disappears. Thus, the superconducting dome coincides with a crossover regime where the highly polarizable dielectric state of undoped SrTiO3 is tuned into a normal dielectric state through electron doping. Our result provides direct evidence of the key role of the soft TO mode and its hybridization with the TA mode in the superconducting dome of quantum paraelectrics.

Results

Figure 1a–d show the dispersion of the soft ferroelectric mode as measured by INS along the (H,H,0) direction for carrier densities ranging from 2.4 × 1018 cm−3 to 1.0 × 1021 cm−3 at T = 1.5 K. The identity of the dopants (La or Nb) is indicated in parentheses for each carrier density. Descriptions of the samples, their characterization by electrical transport measurement and the configuration of spectrometers are given in the Supplementary Information Note A. Convolution of the phonon spectral function with the spectrometer resolution function allows accurate fits and independent determination of ωTO, vTO and the energy width of the TO-mode (Γ), see Supplementary Information Note B. In the whole doping range, the energy dispersion of the TO mode satisfies Eq.(1) along both directions (H,H,2) and (H,2,0), see Fig. 1e, f.

Momentum-and energy-resolved neutron scattering intensity map of along the (H,H,2) direction in SrTi1−xNbxO3 with an electron density a n(Nb) = 2.4 × 1018 cm−3, b n(Nb) = 2.3 × 1019 cm−3, c n(Nb) = 1.8 × 1020 cm−3 and in Sr1−xLaxTiO3 with d n(La) = 1.0 × 1021 cm−3 at T = 1.5 K. e Dispersion of the soft ferroelectric mode along [H,H,0] for the five dopings studied as function of H2. f same as (e) along [H,0,0]. For all the doping the dispersion can be fitted through : E2(q)=\({\omega }_{TO}^{2}\)+\({v}_{TO}^{2}{q}^{2}\), where q[1,1,0]=\(\frac{2\pi }{a}\sqrt{2}\)H and q[1,0,0]=\(\frac{2\pi }{a}\)H where a is the lattice parameter of SrTiO3, that allows one to determine \({\ell }_{0}=\frac{{v}_{TO}}{{\omega }_{TO}}\). Black arrows on (a–d) indicate the position of ωTO.

Figure 2a shows the energy scans at Q = (0,0,2) for five of the samples studied at T = 1.5 K. The soft TO mode begins to harden when the carrier density exceeds 2.3 × 1019 cm−3. Figure 2b–d show the deduced doping evolution of ωTO, vTO and Γ. As doping increases, ωTO increases from 2.1 meV at n(Nb) = 2.4 × 1018 cm−3, which is comparable to the value in pure SrTiO3, to 17.0 meV at n(La) = 1.6 × 1021 cm−3. This sudden hardening of the TO mode is accompanied by a slight decrease of vTO at low temperature of about 40%, and a slight decrease of its energy width. Like in pure SrTiO314,15, we note no anisotropy in the TO-dispersion across the doping range studied (vTO(Q//[1, 1, 0]) ≈ vTO(Q//[1, 0, 0])).

a E-scans at Q = (0, 0, 2) for five electron doped samples. Curves are shifted for clarity. b ωTOvs.n in linear-log scale in oxygen reduced STO (green points from ref. 30), in Nb-doped STO (close circle points are INS data, open squares are from infrared measurements from ref. 29), in La-doped STO (close red circles). Inset : \({\omega }_{TO}^{2}\)vs.n in linear scale. The dot line is a linear fit of slope 2.3 × 1019 meV2.cm3. c vTOvs.n in linear-log scale in Nb and La doped STO deduced from the fit of the dispersion shown in Fig. 1, in oxygen reduced samples (green open symbols) at T = 300 K measured along [111] direction from ref. 30. d Energy width (ΓTO) of the TO mode at T = 1.5 K at H=K=0 (closed symbols). e Intensity of the TO mode normalized with the TA mode intensity at T = 150 K. Error bars are deduced from the convolution with refinement program that finds the best least-squares fit of the dispersion parameters (see Supplementary Information Note B).

The collapse of the quantum para-electric regime upon doping is further supported by the temperature dependence of ωTO and vTO shown on Fig. 3a, b. Up to n(Nb) = 2.3 × 1019cm−3, the T-dependence of ωTO and vTO shows almost no difference from the parent compound14 (black open square points in Fig. 3a, b). Above this concentration, the TO mode becomes almost temperature independent. Similar results have also been observed in oxygen reduced samples (see Supplementary Information Note B). At the highest doping studied, the system is no longer in the quantum para-electric phase. vTO, by contrast, barely changes with temperature, and decreases by 40% with doping.

a, b Temperature dependence of ωTO and vTO for the five doping studied compare with the parent compound values from ref. 14 (in black open square points). c Amplitude of the TA softening at Q = (0.05,0.05,2) versus temperature for three dopings compare with the parent compound behavior (in black open circle points from ref. 17). As the TO mode becomes harder the TA softening vanishes as a consequence of the decrease of the coupling between both modes. Error bars are deduced from the convolution with refinement program that finds the best least-squares fit of the dispersion parameters (see Supplementary Information Note B).

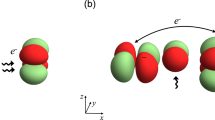

Previous studies documented hybridization between the TO and TA branches in the undoped SrTiO314,15,17. This hybridization, a consequence of the anharmonic coupling of phonon modes16, is concomitant with the softening of the TO mode. It manifests itself in two ways. First, there is a dramatic transfer of intensity from the TA branch towards the TO mode at Q = (0,0,2)14,16. Second, the TA mode itself softens at a finite wave-vector17. The latter feature has been recently ascribed to a flexo-electric effect25. According to our results, doping not only hardens the TO mode, but also weakens the TO-TA hybridization. When doping increases, the absolute intensity of the TO mode, normalized by the amplitude of the TA mode at high temperature in each sample decreases by about a factor four, see Fig. 2e and Supplementary Information Note B. Simultaneously, the TA softening, measured at Q = (0.05,0.05,2), decreases and vanishes at the highest doping (see Fig. 1c). Thus, the hardening of the TO mode is accompanied by the weakening of its coupling with the TA mode. As a result, the spectral weight transfer and the softening of the TA mode both eventually vanish with doping, thus Γ decreases. At the highest doping, we note an increase of Γ possibly related to the damping of the TO mode by the electrons, which has been proposed to explain the increase of superconductivity in ferroelectric-type materials26,27. The breakdown of the quantum para-electric regime is thus concomitant with the breakdown of the TO-TA hybridization, providing further evidence that both effects are intimately related.

Discussion

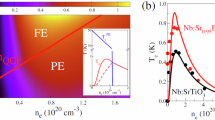

Our measurement allows us to quantify for the first time the doping evolution of \({\ell }_{0}=\frac{{v}_{TO}}{{\omega }_{TO}}\), (see Fig. 4a). Due to the combined change of ωTO and vTO, ℓ0 decreases by more than one order of magnitude with the doping, and saturates to the Ti-O distance (\(\frac{a}{2}\), where a is the lattice parameter), above n ≈ 1 × 1021 cm−3. The comparison of the doping evolution of ℓ0 with Tc is clue to understand the origin of the superconducting dome of SrTiO3. Figure 4c shows the superconducting domes for SrTi1−xNbxO3, Sr1−xLaxTiO312 and SrTi(\({}^{18}{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{y}^{16}{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{1-y}\))3−δ28. Regardless of the nature of the dopants, all the domes end at a carrier density of n ≈ 1 × 1021 cm−3. The end of the superconducting domes is thus concomitant with the saturation of \({\ell }_{0}\approx \frac{a}{2}\), i.e., the end of the quantum-para-electric regime. We note that our doping evolution of ωTO is in good agreement with early infra-red measurements29 in SrTi1−xNbxO3 and INS measurements in oxygen reduced SrTiO330. We used this earlier data and estimated ℓ0 in SrTiO3−x, as shown in Fig. 4a, based on the observed temperature independence of vTO in Nb and La-doped samples.

a Doping evolution of ℓ0=\(\frac{{v}_{TO}}{{\omega }_{TO}}\) for Nb-doped (blue points), La-doped (red points), reduced SrTiO3 (in green points estimated from ref. 30, see the text) and \(\frac{a}{2}\) (in gray dot line) where a = 3.9 Å is the lattice parameter of SrTiO3. b Doping evolution of the Fermi momentum (kF) in the three sub-bands i = 1,2 and 3. c Doping evolution of the superconducting critical temperature (Tc) according to11,12,46. The gray areas in (a, c) mark the end of the superconducting dome concomitant with the saturation of ℓ0 to about \(\frac{a}{2}\). d \({k}_{F}^{i}{\ell }_{0}\)vs.n for each sub-band. e Comparison of the carrier dependence of ℓ0 and Tc in linear scale. f Sketch of the electron doping evolution of 2ℓ0 (blue disk) and 2kF (black dot arrows). With electron doping ℓ0 decreases and saturates to about \(\frac{a}{2}\), the Ti-O distance, while kF increases. The summit of the superconducting dome occurs when \({k}_{F}^{3}{\ell }_{0}\) is the largest, see the text. Error bars on Tc are from11,12,46.

The key role of ℓ0 in shaping the superconducting dome of SrTiO3 is further highlighted once it is compared with the density of the states length scale, kF. For Nb and La doped samples the evolution of the Fermi surface is well captured by the rigid band approximation31,32. It consists of three non-parabolic bands located at the Γ-point, which are successfully filled at two critical dopings: nc1 = 1.2 × 1018 cm−3 and nc2 = 2.2 × 1019 cm−3. Figure 4b shows the doping evolution of the average Fermi momentum, \({k}_{F}^{i}\), in the three sub-bands (i = 1,2,3) as determined by the frequency of quantum oscillation studies33 for a magnetic field parallel to the [001] direction. When the carrier density increases, \({k}_{F}^{i}\) increases, while ℓ0 decreases. As a result, \({k}_{F}^{i}{\ell }_{0}\) displays a dome shape whose peak shifts to a higher concentration as each sub-band fills, see Fig. 4d. For the last two bands, the peaks in \({k}_{f}^{i}{\ell }_{0}\) occur at approximately 3 × 1019 cm−3, which is three times lower than the peak of the superconducting dome in Nb-doped SrTiO3. Interestingly, for the last band, the peak occurs at n = 5 × 1019 cm−3, close to the middle of the superconducting dome of SrTi1−xNbxO3, see Fig. 4c.

This comparison allows us to draw a qualitative picture of the doping evolution of Tc, sketched in Fig. 4c. At low doping, where ℓ0 ≈ 3 nm, Tc increases due to the increase of \({k}_{F}^{i}\) up to n ≈ 2 × 1019 cm−3 where ℓ0 starts to decrease. A close inspection of the behavior of Tc and ℓ0 in the overdoped regime shows that ℓ0 drops faster than Tc, see Fig. 4f. Above the summit of the superconducting dome, the increase in the density of states does not enhance the critical temperature. Superconductivity is weakened as ℓ0 shrinks. Above n ≈ 0.5 × 1021 cm−3, Tc inevitably vanishes as ℓ0 reaches its minimum value—the Ti-O distance (\(\frac{a}{2}\))—at which point the normal dielectric state is fully reached.

So far, the overdoped regime has been understood as the passage from the clean to the dirty limit34, and the end of the dome as the end of the anti-adiabatic regime10. Indeed, the ratio of \(\frac{{E}_{F}}{{\omega }_{TO}}\) remains approximately constant at 3–4, placing it in an intermediate regime between the adiabatic (EF ≫ ωTO) and anti-adiabatic (EF ≪ ωTO) limits. Our result identifies the length scale ℓ0, which drives the decrease of Tc and of the superconducting gap, Δ, whose ratio has been found constant to the weak-coupling BCS value across the dome10,35. This result is consistent with quantum critical theories applied to ferroelectrics36,37,38 and with theoretical works where electrons are coupled with the soft TO-mode18,19,20,21,22,39,40. Combined with the known Fermi surface probed by quantum oscillations studies9,31,32,41, our result provides the parameters to quantitatively test theories of superconductivity in SrTiO3. It also helps to understand the electron doping evolution of the unusual thermal conductivity42, isotropic magneto-resistance43 and T2-term resistivity44,45 in doped SrTiO3.

In contrast to the overdoped regime, the underdoped regime shows a dopant dependence, see Fig. 4c. It can arise from variations in the Fermi surfaces, as evidenced in oxygen-reduced and Nb-doped SrTiO3, where different Fermi seas have been found by quantum oscillation measurements32. It can also be attributed to a dopant-variation of ℓ0. Under Ca, Ba or O18 substitution, SrTiO3 becomes ferroelectric. That ferroelectric state vanishes under electron doping12,28,46. Investigating the electron doping dependence of ℓ0 and of the TO/TA hybridization for these ferroelectrics or in plastic deformed SrTiO347 is an appealing perspective to elucidate the differences in their underdoped regime.

In conclusion, we show that the end of the superconducting dome of bulk SrTiO3 is concomitant with the collapse of the quantum para-electric regime. This result demonstrates the key role of the soft TO mode and its hybridization with the TA branch in the superconductivity of quantum paraelectrics and their interface.

Methods

Nb-doped samples have been provided by CrysTec GmbH. La-doped samples have be grown using the floating zone technique12. Hall carrier densities and electron mobilities were determined using electrical transport measurements conducted with a standard four-probe method in a Quantum Design Physical Property Measurement System, up to 12 T. For further details, see Supplementary Information Note A. Inelastic neutron scattering (INS) measurements were performed on the thermal neutron triple-axis spectrometers EIGER48 at the Swiss spallation neutron source (SINQ), Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI), Villigen, Switzerland, and IN8 at the Institut Laue-Langevin (ILL)49, Grenoble, France, as well as on the cold triple-axis spectrometer TASP (SINQ-PSI)50. The samples were successively oriented such that momentum transfers Q of the form (H,H,L), (H,K,0) were accessible. Measurements on EIGER and IN8 were done with kf = 2.662 Å−1 and on TASP with kf = 1.97 Å−1 with one PG filter inserted into the scattered beam in order to eliminate higher order contamination. Except for measurements on IN8, which employed a doubly focused Si(111) monochromator, PG002 monochromators and analyzers were used. No collimations were applied. For details on the experimental fitting, see Supplementary Information Note B.

Data availability

Data collected on IN8 at ILL are available at https://doi.org/10.5291/ILL-DATA.DIR-318. All the other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author B.F. upon request.

References

Keimer, B., Kivelson, S. A., Norman, M. R., Uchida, S. & Zaanen, J. From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper oxides. Nature 518, 179 (2015).

Fernandes, R. M. et al. Iron pnictides and chalcogenides: a new paradigm for superconductivity. Nature 601, 35 (2022).

White, B., Thompson, J. & Maple, M. Unconventional superconductivity in heavy-fermion compounds. Phys. C. Supercond. Appl. 514, 246 (2015).

Bustarret, E. Superconductivity in doped semiconductors. Phys. C. Supercond. Appl. 514, 36 (2015).

Zubko, P., Gariglio, S., Gabay, M., Ghosez, P. & Triscone, J.-M. Interface physics in complex oxide heterostructures. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2, 141 (2011).

Balents, L., Dean, C. R., Efetov, D. K. & Young, A. F. Superconductivity and strong correlations in moiré flat bands. Nat. Phys. 16, 725 (2020).

Collignon, C., Lin, X., Rischau, C. W., Fauqué, B. & Behnia, K. Metallicity and superconductivity in doped strontium titanate. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 10, 25 (2019).

Gastiasoro, M. N., Ruhman, J. & Fernandes, R. M. Superconductivity in dilute SrTiO3: a review. Annl. Phys. 417, 168107 (2020).

Lin, X., Zhu, Z., Fauqué, B. & Behnia, K. Fermi surface of the most dilute superconductor. Phys. Rev. X 3, 021002 (2013).

Yoon, H. et al. Low-density superconductivity in SrTiO3 bounded by the adiabatic criterion. arXiv e-prints, arXiv:2106.10802 (2021).

Tomioka, Y., Shirakawa, N., Shibuya, K. & Inoue, I. H. Enhanced superconductivity close to a non-magnetic quantum critical point in electron-doped strontium titanate. Nat. Commun. 10, 738 (2019).

Tomioka, Y., Shirakawa, N. & Inoue, I. H. Superconductivity enhancement in polar metal regions of Sr0.95Ba0.05TiO3 and Sr0.985Ca0.015TiO3 revealed by systematic Nb doping. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 111 (2022).

Müller, K. A. & Burkard, H. SrTiO3: an intrinsic quantum paraelectric below 4 K. Phys. Rev. B 19, 3593 (1979).

Yamada, Y. & Shirane, G. Neutron scattering and nature of the soft optical phonon in SrTiO3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 26, 396 (1969).

Courtens, E. et al. Phonon anomalies in SrTiO3 in the quantum paraelectric regime. Phys. Scr. T49B, 430 (1993).

He, X. et al. Anharmonic eigenvectors and acoustic phonon disappearance in quantum paraelectric SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 145901 (2020).

Fauqué, B. et al. Mesoscopic fluctuating domains in strontium titanate. Phys. Rev. B 106, L140301 (2022).

van der Marel, D., Barantani, F. & Rischau, C. W. Possible mechanism for superconductivity in doped SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. Res. 1, 013003 (2019).

Kiselov, D. E. & Feigel’man, M. V. Theory of superconductivity due to Ngai’s mechanism in lightly doped SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. B 104, L220506 (2021).

Volkov, P. A., Chandra, P. & Coleman, P. Superconductivity from energy fluctuations in dilute quantum critical polar metals. Nat. Commun. 13, 4599 (2022).

Yu, Y., Hwang, H. Y., Raghu, S. & Chung, S. B. Theory of superconductivity in doped quantum paraelectrics. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 63 (2022).

Gastiasoro, M. N., Temperini, M. E., Barone, P. & Lorenzana, J. Theory of superconductivity mediated by Rashba coupling in incipient ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. B 105, 224503 (2022).

Vugmeister, B. E. & Glinchuk, M. D. Dipole glass and ferroelectricity in random-site electric dipole systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 62, 993 (1990).

Samara, G. A. The relaxational properties of compositionally disordered ABO3perovskites. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 15, R367 (2003).

Guzmán-Verri, G. G., Liang, C. H. & Littlewood, P. B. Lamellar fluctuations melt ferroelectricity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 046801 (2023).

Setty, C., Baggioli, M. & Zaccone, A. Superconducting dome in ferroelectric-type materials from soft mode instability. Phys. Rev. B 105, L020506 (2022).

Setty, C., Baggioli, M. & Zaccone, A. Erratum: superconducting dome in ferroelectric-type materials from soft mode instability [phys. rev. b 105, 020506 (2022)]. Phys. Rev. B 106, 139903 (2022).

Rischau, C. W. et al. Isotope tuning of the superconducting dome of strontium titanate. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 013019 (2022).

Devreese, J. T., Klimin, S. N., van Mechelen, J. L. M. & van der Marel, D. Many-body large polaron optical conductivity in SrTi1−xNbxO3. Phys. Rev. B 81, 125119 (2010).

Bäuerle, D., Wagner, D., Wöhlecke, M., Dorner, B. & Kraxenberger, H. Soft modes in semiconducting SrTiO3: II. The ferroelectric mode. Z. f.ür. Phys. B Condens. Matter 38, 335 (1980).

Allen, S. J. et al. Conduction-band edge and Shubnikov–de Haas effect in low-electron-density SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. B 88, 045114 (2013).

Fauqué, B. et al. Electronic band sculpted by oxygen vacancies and indispensable for dilute superconductivity. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 033080 (2023).

Lin, X. et al. Critical doping for the onset of a two-band superconducting ground state in SrTiO3−δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 207002 (2014).

Collignon, C. et al. Superfluid density and carrier concentration across a superconducting dome: the case of strontium titanate. Phys. Rev. B 96, 224506 (2017).

Thiemann, M. et al. Single-Gap superconductivity and dome of superfluid density in Nb-Doped SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 237002 (2018).

Edge, J. M., Kedem, Y., Aschauer, U., Spaldin, N. A. & Balatsky, A. V. Quantum critical origin of the superconducting dome in SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 247002 (2015).

Rowley, S. E. et al. Ferroelectric quantum criticality. Nat. Phys. 10, 367 (2014).

Enderlein, C. et al. Superconductivity mediated by polar modes in ferroelectric metals. Nat. Commun. 11, 4852 (2020).

Klein, A., Kozii, V., Ruhman, J. & Fernandes, R. M. Theory of criticality for quantum ferroelectric metals. Phys. Rev. B 107, 165110 (2023).

Saha, S. K., Gastiasoro, M. N., Ruhman, J. & Klein, A. Strong coupling theory of superconductivity and ferroelectric quantum criticality in metallic srtio3. (2024), arXiv:2412.05374 [cond-mat.str-el].

Uwe, H., Yoshizaki, R., Sakudo, T., Izumi, A. & Uzumaki, T. Conduction band structure of SrTiO3. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 24, 335 (1985).

Martelli, V., Jiménez, J. L., Continentino, M., Baggio-Saitovitch, E. & Behnia, K. Thermal transport and phonon hydrodynamics in strontium titanate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 125901 (2018).

Collignon, C. et al. Quasi-isotropic orbital magnetoresistance in lightly doped SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 065002 (2021).

Lin, X., Fauqué, B. & Behnia, K. Scalable T2 resistivity in a small single-component Fermi surface. Science 349, 945 (2015).

Kumar, A., Yudson, V. I. & Maslov, D. L. Quasiparticle and nonquasiparticle transport in doped quantum paraelectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 076601 (2021).

Rischau, C. W. et al. A ferroelectric quantum phase transition inside the superconducting dome of Sr1−xCaxTiO3−d. Nat. Phys. 13, 643 (2017).

Hameed, S. et al. Enhanced superconductivity and ferroelectric quantum criticality in plastically deformed strontium titanate. Nat. Mater. 21, 54 (2022).

Stuhr, U. et al. The thermal triple-axis-spectrometer eiger at the continuous spallation source sinq. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip. 853, 16 (2017).

Piovano, A. & Ivanov, A. The TAS-IN8 upgrade: towards the limit of a three-axis spectrometer performance. EPJ Web Conf. 286, 03011 (2023).

Semadeni, F., Roessli, B. & Böni, P. Three-axis spectroscopy with remanent benders. Phys. B Condens. Matter 297, 152 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Feigelman, R. Fernandes, D. Kiseliov, M. Gastiasoro, G. Guzmán-Verri, R. Lobo, P. Littlewood, A. Subedi and D. Van Der Marel for useful discussions. This work was supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-18-CE92-0020-01, ANR-22-CE30-0032-02), by Jeunes Equipes de l\({\prime}\)Institut de Physique du Collège de France and by a grant attributed by the Ile de France regional council. This work is based on experiments performed at the Swiss spallation neutron source SINQ, Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, Switzerland. This work was also supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number 23H01135.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

La doped samples have been grown by Y.T. Sample alignments have been done by B.F., C.R., and B.B. Electrical transport measurements have been done by S.J. and B.F. Inelastic neutron scattering measurement have been done by B.F., P.B., T.F., B.R., and A.I. Data analysis have been done by B.F. Manuscript has been written by B.F. and K.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fauqué, B., Jiang, S., Fennell, T. et al. Doping dependence of the dipolar correlation length scale in metallic SrTiO3. Nat Commun 16, 2301 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56806-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56806-w

This article is cited by

-

Strong coupling theory of superconductivity and ferroelectric quantum criticality in metallic SrTiO3

npj Quantum Materials (2025)