Abstract

The Grignard reaction represents one of the most powerful carbon-carbon bond forming reactions and is the subject of continual study. Investigations of alkyl magnesium halide additions to β-hydroxy ketones identified a unique effect of the magnesium halide on diastereoselectivity, with alkylmagnesium iodide reagents demonstrating high levels of selectivity for the formation of 1,3-syn diols. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations and mechanistic studies suggest that the Lewis acidity of a chelated magnesium alkoxide can be tuned by the choice of halide, with the highest levels of diasteroselectivity achieved using alkyl magnesium iodide reagents. Exploiting this finding, we demonstrate that the diastereoselective addition of alkyl magnesium iodide reagents to ketofluorohydrins enables rapid access to naturally configured C4’-modified nucleosides. This work provides a platform to support antiviral and anticancer drug discovery and development efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Grignard reaction is a prototypical carbon-carbon bond-forming reaction and has been widely exploited by organic chemists for more than a century1,2. In addition to 1,2-addition reactions, Grignard reagents undergo radical3,4,5 and cross-coupling reactions6,7, and can be exploited as strong bases in a variety of scenarios8. Transmetalation to other organometal species also engenders a suite of complimentary reactivities2,9,10. While Grignard reagents are commonly represented as ‘RMgX’, their actual structure is well-understood to be far more complex. First, an equilibrium (Schlenk) exists between the diorganomagnesium (MgR2), organomagneisum halide (RMgX) and dihalomagnesium (MgX2) species (eq. 1)1,11. Second, these individual species can exist as monomers or as dimeric or polymeric aggregates depending on concentration, choice of solvent, and the nature of the halide4,12. Third, temperature also impacts reagent composition and reactivity13,14. Recent computational studies have helped shed additional light on these complex processes15. Thus, the solvent, R group, and temperature all impact reagent composition, and reaction mechanism and outcomes5,11,13,15. For example, the distinct reactivity of MgR2 and RMgX has been discussed in detail14,16.

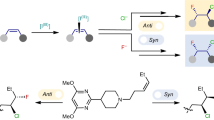

The diastereoselective addition of Grignard reagents to prochiral ketones13,17,18 has been studied extensively, including by Ashby4,11 and others19,20,21, and often involves coordination to proximal functional groups according to Cram’s model22,23 (e.g. alkoxy21,24,25,26,27 and amino28,29,30, Fig. 1A). Therefore, the stereochemical outcome of these reactions can differ in selectivity from other organometallic reagents (e.g. Cu, Al, Li)31,32,33,34. In the specific case of β-hydroxy ketones, the formation of an intermediate magnesium alkoxide can rigidify acyclic systems and impart further control of the diastereochemical outcome of reactions. Previous work from our groups demonstrated that the addition of Grignard reagents to ketofluorohydrins of general structure 1 provided a direct route to C4’-modified L-configured α- and β-nucleoside analogues (NAs, 2) (Fig. 1B)35. Our interest in this process derives from the significant role C4’-nucleoside modification plays in modulating the conformation (sugar pucker) of the furanose and consequently interactions with biological targets36,37,38. As a result, C4’-modified NAs play an important role as antiviral agents37,39,40,41, leading cancer treatments42, and core structural components of antisense oligonucleotides43,44,45. Examples include ALS-8112 (3), an anti-RSV agent, 4′-cyano-2′-deoxyguanosine (4), an anti-HBV agent, and islatravir (5), developed for the treatment of HIV. Despite the simplicity of our approach, this work was largely limited to the production of unnaturally configured L-NAs, which were produced as both α- and β-anomers, which are less suitable for supporting medicinal chemistry campaigns. To better understand the observed diastereoselectivity of these processes and access the complimentary suite of naturally configured D-NAs, we initiated a detailed study of this 1,2-additon reaction. Unexpectedly, we discovered a unique halide effect that controls the diastereoselectivity of reactions between Grignard reagents and β-hydroxy ketones. To the best of our knowledge, this halide effect has not been previously described. Here, we report the discovery of the halide effect, its impact on the stereochemical outcome of Grignard reactions, and its application in the rapid production of C4’-modified D-configured NAs (Fig. 1C)46.

A Examples of chelate-controlled Grignard additions. B Our previous synthesis of C4’-modified nucleosides. C This work: selective, chelate-controlled Grignard addition reactions leading to the synthesis of D-configured C4’-modified nucleoside analogues. D Examples of medicinally relevant C4’-modified nucleoside analogues. Blue boxes highlight the C4’-position. Blue colouring is used to highlight the halide atom in Grignard reagents and the alkyl group in dialkyl Grignard reagents.

Results

Considering the potential for multiple chelation modes in the Grignard reactions discussed above (Fig. 1B), we prepared the hydroxy ketones 7-947,48,49, with and without a Cl or F substituent and lacking the nucleobase function to better understand the influence of individual functional groups on diastereoselectivity. From a panel of organometallic reagents, we found that Grignard reagents generally gave the cleanest reaction profile. The addition of various organometallic reagents to the corresponding silyl ethers (e.g. 6, Table 1, entry 1) gave exclusively the 1,3-anti product 13. This result confirmed the importance of the β-hydroxy function for the formation of the desired 1,3-syn diol. Furthermore, while the reaction of the β-hydroxyketone 7 with MeMgCl in THF gave an ~1:1 mixture of diastereomeric diols 10a and 10b (entry 2), the equivalent reaction in non-coordinating CH2Cl2 improved selectivity for the syn diol 10a (entry 3), highlighting the importance of chelation24. Surprisingly, the use of MeMgBr led to a significant increase in syn diol 10a selectivity (~6:1 d.r.) that was also observed with MeMgI (entries 4 and 5), though in CH2Cl2 only (entry 6). To assess the role of the fluorine atom in these processes, we prepared the corresponding chlorohydrin 8 and carried out a similar suite of reactions (entries 8–10). Here, we observed a ~ 5-fold increase in diastereoselectivity for syn diol 11a on switching from MeMgCl to MeMgI. Finally, we examined the nonhalogenated hydroxy ketone 9 and found that the diastereoselectivity increased ~2.5-fold on switching from MeMgCl to MeMgI (entries 11 and 12), suggesting that the halide effect was perhaps more general.

To assess whether the Schlenk equilibrium played a role in this process, the dialkyl magnesium reagent Me2Mg was also reacted with ketone 7, which gave a 1:1 mixture of diols (entry 7). This result prompted us to confirm that a MeMgX to Me2Mg equilibrium was not complicating the reactions presented in Table 1. To do so, we analysed each commercial Grignard reagent in CD2Cl2 by NMR spectroscopy at room temperature (see Supplementary Fig. 1) and at −58 °C (see Fig. 2) and found that (i) the reagents were distinguishable by carbon chemical shift, and (ii) the MeMgX reagents were free of Me2Mg at these temperatures. Additionally, we ensured that the observed halide effect was not due to unexpected aggregates of the Grignard reagents by executing reactions at concentrations shown to prevent the formation of aggregates4. Collectively, these results indicate that changes in diastereoselectivity can be attributed to the halide ‘X’ in MeMgX. Notably, the very few examples of halide effects on reactions of Grignard reagents include impact on regioselectivity50,51, yields52, and diastereoselectivity (in ethereal solvents)53,54,55. The most similar finding to that presented in Table 1 was a small increase in diastereoselectivity reported in a table of data describing the addition of MeMgBr vs MeMgCl to a 2′‑oxouridine derivative56. Beyond this observation and to the best of our knowledge, the halide effect on diastereoselective addition reactions of Grignard reagents has not been discussed or exploited in a unified way.

Having identified conditions for the selective formation of syn diol 10 (Table 1, entry 5), we turned to the more structurally complex ketofluorohydrin 14, which incorporates the unprotected nucleobase thymine. As summarised in Table 2, we observed a similar trend in diastereoselectivity, indicating that the nucleobase had minimal effect on the diastereochemical outcome of these reactions. For example, using MeMgCl in CH2Cl2 led to a 2.3:1 diastereomeric ratio favoring the syn diol 15 (entry 1), while MeMgI favoured the syn diol 15 with a 6:1 d.r. (entry 3). Again, the use of THF as the solvent or Me2Mg as the Grignard reagent led to a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers (entries 4 and 5).

Figure 3 summarises our efforts to explore the broader scope of this reaction and, more specifically, target 1,2-addition products that could be useful for the synthesis of C4’-modified nucleoside analogues57. As indicated, the trends identified above translated to the addition of alkyl Grignard reagents with the thymine derivative 14. Several additional nucleobases, including 5-iodouracil, pyrazole and a chloroiododeazadenine also proved compatible with this process. Notably, this process was also compatible with protected versions of the natural nucleobases adenine and guanine (e.g. 22 and 25). In the case of the uracil derivative, while the 1,3-syn selectivity mirrored the results with thymine (~4:1 d.r.), degradation of the starting material and/or product during the reaction limited the yield of 18 to 29%. While the magnitude of diastereoselectivity varied slightly based on the combination of alkyl group and nucleobase, the simple modification of solvent (CH2Cl2) and halide (I) on the Grignard reagent led to the preferred formation of the desired 1,3-syn diol in all cases, providing a collection of 11 distinct 1,2-addition products 15–25. In contrast, the diastereomeric ratio of products derived from the addition of alkenyl or alkynyl Grignard reagents was not improved by the use of the corresponding MgBr reagent, and the 1,3-syn-diols 26 and 27 were formed in near equal amounts to the corresponding 1,3-anti-diol.

It is notable that each of the reactions required an excess (typically 5–10 equivalents) of RMgI to ensure complete consumption of starting materials. In the case of thymine derivative 14, it is reasonable that the first two equivalents of Grignard reagent are consumed through the deprotonation of the thymine NH and hydroxyl functions. It is then expected that the reaction proceeds via a chelate structure (e.g. 28) and that the halide in this chelate structure plays a central role in determining the diastereoselectivity. To probe this hypothesis, we also examined the addition of 2 equivalents of MeMgI to thymine derivative 14, which proved insufficient to generate any of the 1,2-adduct 15 but should produce Mg chelate 28. We then examined the addition of RMgBr reagents and found that this simple modification was sufficient to enhance the diastereoselectivity. For example, addition of 2 equivalents of MeMgI to thymine derivative 14 followed by EtMgBr gave the 1,3-syn-diol 16 in improved diastereoselectivty over the use of EtMgBr alone. Likewise, addition of 2 equivalents of MeMgI followed by HC≡CMgBr gave the 1,3-syn-diol 29 as the major product.

To better understand this unusual halide effect on diastereoselectivity, we conducted DFT calculations (Fig. 4). Considering that the nucleobase had little impact on diastereoselectivty, we used the simplified model system 30 in which the nucleobase is replaced by a methyl group for all calculations (Fig. 4A). As noted above, we hypothesised that deprotonation of the alcohol function in 30 would lead to a Mg chelate 31-X16. Due to the non-coordinating nature of the solvent CH2Cl2 and the tendency for Mg to be tetracoordinated in solution, the fluorine atom was also expected to serve as an additional Lewis donor58,59. In the appropriate conformation, (Re)-addition of a second equivalent of the Grignard reagent would yield anti-32. On the other hand, (Si)-addition would form the desired diastereoisomer syn-32. With chelate 31 in mind, we located the corresponding transition states (TSs) for the (Si) and (Re)-additions of MeMgCl, MeMgBr and MeMgI (Fig. 4B). Computationally, we can interpret d.r. as the difference of differences of energies (ΔΔG‡) for two competing diastereoisomeric TSs60. These energies were Boltzmann-averaged using the code developed by the Paton lab (see Supplementary Information, Section 1: computational details)61.

A Mechanistic hypothesis through chelate 31-X (X = Cl, Br, I). In (A) the alkyl group that is added is highlighted in blue as well as the faces of the prochiral ketone. B Calculated TSs for the Grignard addition of MeMgCl (left), MeMgBr (middle) and MeMgI (right). Bottom: (Si)-addition. Top: (Re)-addition. The presented energies, as ΔΔG‡(X) are relative to the lowest-energy (Si)-TS for each pair of diastereoisomers within the same halide (X = Cl, Br, I). C Calculated TSs for the addition of Me2Mg, (Si)-addition on the bottom, (Re)-addition on top. This value, close to zero (see SI for further details), implies that this reaction is not diastereoselective. D NBO analysis showing donor orbitals (top) and acceptor orbitals (bottom). NBOs are coloured red and blue to emphasise the different orbital phases. E Proposed chelate model. In B, C and E, atoms are coloured as hydrogen (white), carbon (grey), oxygen (red), fluorine (blue), magnesium (yellow), chlorine (green), bromine (brown), iodine (purple). NBO: Natural Bond Orbital, EDA: Energy Decomposition Analysis. Relative Gibbs free energies were calculated at the M06-2X(SMD=CH2Cl2)/def2-TZVPP//M06-2X/6-31 + G(d) level of theory, are Boltzmann-averaged, and are presented in kcal mol−1. The LANL2DZ basis set was used for iodine during the geometry optimisation step. Delocalisation energies were calculated at the M06-2X(SMD=CH2Cl2)/def2-TZVPP level of theory using the M06-2X/6-31 + G(d)/LANL2DZ optimised geometries and are presented in kcal mol−1. Only the lowest-energy conformers are shown.

Gratifyingly, the observed experimental trends highlighted in Tables 1 and 2 were reproduced through calculations, which show an increasing ΔΔG‡ throughout the halide series Cl→Br→I (ΔΔG‡(Cl)= 2.35 kcal mol−1 for TS-Cl-Si/Re, ΔΔG‡(Br) = 3.28 kcal mol−1 for TS-Br-Si/Re, and ΔΔG‡(I) = 4.30 kcal mol−1 for TS-I-Si/Re). Here, all (Si)-additions include a chair conformation of the dioxanone and are favoured over the corresponding twist-boat-TSs for the (Re)-additions. In addition, the heteroatom substituent adjacent to the carbonyl in the (Si) addition TSs has a Cornforth structure-conformation, in which the dipoles of the carbonyl group and the polar α-oxygen atom are opposed. On the other hand, the TSs for the (Re) attack adopt a polar Felkin-Anh conformation. When the α-substituent to the carbonyl is an ether, the Cornforth structures are favoured over a polar Felkin-Anh conformation—this has been calculated and reported by Cramer and Evans62. Throughout the (Si)-TS series, the Mg⋯F interaction further enforces a chair conformation and the Mg-F distance is 2.07 Å for each of TS-Cl-Si, TS-Br-Si and TS-I-Si (Fig. 4B). In contrast, in the (Re)-addition TSs, the Mg-F distances are longer and show more variation: TS-Cl-Re (2.37 Å), TS-Br-Re (2.10 Å) and TS-I-Re (2.17 Å). As an additional point of interest, the terminal methyl group in model system 30 is directed away from the reacting carbonyl in all TSs. This observation is consistent with experimental results, where the diastereoselectivity is not greatly influenced by the terminal group (nucleobase or i-Pr group).

In addition to the TSs discussed above, we also located TSs TS-Me-Si and TS-Me-Re, derived from the equivalent reaction with Me2Mg (Fig. 4C). For these two TSs a ΔΔG‡(Me) = 0.00 kcal mol−1 was calculated, which is consistent with a non-diastereoselective addition for the reaction of Me2Mg with both fluorohydrins 7 and 14 (Table 1, entry 7; and Table 2, entry 5).

Geometrically, the TSs TS-Cl-Si, TS-Br-Si and TS-I-Si show little structural difference. Each TS includes the aforementioned Mg-F interaction, a chair conformation in the dioxanone scaffold, and a bridging nucleophilic methyl group between the two magnesium atoms. Observing these TSs indicates that the magnesium atom from the intermediate chelate 31-X could be directing the (Si)-facial addition of the second equivalent of MeMgX. These observations suggest that the halide effect may not be the controlling feature of a TS but one of a ground-state conformation instead54. Notably, the halides in each of the (Si)-TSs are directed away from the reacting centre, indicating that the halide size is not a factor in diastereoselection.

To gain further insight we turned to Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis of the corresponding chelates, 31-Cl, 31-Br and 31-I (Fig. 4D). Herein we looked at the orbital delocalisation, from donor to acceptor, and their energies, with emphasis on the orbitals on the Mg atom as a Lewis acceptor (Fig. 4D, bottom row structures). As for the donor orbitals, particular attention was paid to the lone pairs on the F atom and the halides Cl, Br or I (Fig. 4D, top structures).

For 31-Cl and 31-Br, the Mg-F interaction results from an electron donation from a lone pair in the F atom to a non-bonding orbital in the Mg atom (n(F)→n*(Mg)). This electron donation is slightly stronger in 31-Br (19.1 kcal mol−1) than in 31-Cl (17.9 kcal mol−1). This electron donation may further restrict the conformation allowing the Mg atom to direct the second equivalent of MeMgBr more easily. Likewise, the Cl atom in both 31-Cl and the Br atom in 31-Br donate electron density from a lone-pair to the same empty orbital on the Mg atom (n(Cl)→n*(Mg), 67.1 kcal mol−1 and n(Br)→n*(Mg), 80.0 kcal mol−1). These n → n* donations suggest that the halides are more associating in chelates 31-Cl and 31-Br as it is known that the bonding strength of the Mg atom can have variable effects on diastereoselection21. The case is different for 31-I. Here, no donations from the iodine atom were found to the Mg non-bonding orbitals. However, the electron donation from the F atom ends up in the Mg-I anti-bonding orbital (n(F)→s*(Mg-I), 15.7 kcal mol−1). This suggests that in chelate 31-I, the iodine atom is more dissociated when compared to the bromine and chlorine counterparts, thus increasing the Lewis acidity on the Mg center, which would help direct the addition of an incoming nucleophile to the (Si)-face of the carbonyl. Furthermore, energy decomposition analysis (EDA)63 and Wiberg bond indices suggest that the interactions with the Mg atoms are predominantly electrostatic by nature. The conformation of the chelate serves as a template to favour the (Si) addition.

While magnesium chelation has been exploited to influence diastereoselectivity in Grignard reactions24, the effect of the halide in these intermediate chelates has not been thoroughly studied. Generally, a chelating magnesium is thought to lock the substrate in a conformation that biases the addition of a nucleophilic reagent to a particular face of the carbonyl24,64,65. Here, we propose that the chelating magnesium can take on a second role; the coordination to, and directing of, the next equivalent of Grignard reagent. In turn, the halide already bound to the chelating magnesium can influence the metal’s ability to act as this guiding centre.

Finally, with a collection of syn-diols made accessible using RMgI reagents, we demonstrated that these compounds could be readily converted into C4’-modified nucleoside analogues (Fig. 5). Notably, the sequence of reactions required to access these compounds requires only alkylation of the heterocycle66, an α-fluorination/aldol reaction35,67, addition of RMgI, and cyclization. Thus, this 4-step de novo synthesis of naturally or D-configured nucleoside analogues provides an incredibly convenient and diversifiable route to these high-value targets for medicinal chemists. As summarized in Fig. 5, several nucleoside analogues containing thymine, deazadenine, adenine, guanine, uracil and pyrazole bases were prepared through either base or Lewis-acid promoted annulative fluoride displacement35 reactions (33-42). Notably, using basic cyclization conditions with heat, the nitrile containing nucleoside analogue 36 underwent hydrolysis to give the corresponding carboxylic acid (not shown). Executing this reaction at room temperature, the desired nucleoside analogue 36 was produced in good yield. Importantly, all cyclization reactions yielded the β,D-nucleosides. The methyl and ethynyl chloroiododeazaadenine substrates were also cyclized to their corresponding nucleoside analogues using the previously reported Lewis acidic cyclization conditions (39 and 40)35. Likewise, the optimal conditions for cyclization of the adenine substrate involve use of the Lewis acid InCl3 in a mixture of DMSO-H2O. Cyclization of the guanine substrate was promoted by LiOH and heating in H2O. Notably, the yield of both the guanosine and adenosine analogues 41 and 42 reflects the yield of the cyclization and deprotection reactions.

Discussion

In conclusion, we describe a remarkable halide effect on the diastereoselectivity of 1,2-addition reactions to β-hydroxy ketones involving Grignard reagents. Through experimental and computational studies, we show that changing the halide tunes the electronic properties of the intermediate magnesium chelate and in turn its ability to direct the reaction with a second equivalent of Grignard reagent. This process now serves as a foundation for the rapid production of C4’-modified nucleosides with diversifiable positions at the nucleobase and C4’. We expect these results will inspire the synthesis of a wide range of nucleoside analogues and accelerate drug discovery efforts in this area.

Methods

Example of Grignard reaction: preparation of diol 16

To a cold, −78 °C, stirred solution of thymine ketofluorohydrin 14 (150 mg, 0.474 mmol, 1.0 eq) in CH2Cl2 (15.8 mL) under N2 was added EtMgI (0.79 mL, 3.0 M in diethyl ether, 2.37 mmol, 5.0 eq) slowly (along interior wall of flask). The resulting mixture was maintained at −78 °C and stirred for an additional 5 h. The reaction mixture was then quenched with a 1:1 mixture of saturated NH4Cl and MeOH solution (20 mL) and allowed to warm to room temperature. The mixture was then diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL) and the phases were separated. The aqueous phase was washed with CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL) and the organic phases were combined and washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting oil was purified by flash chromatography (EtOAc:hexanes 2:3) to afford diol 16 as a white solid (52 mg, 54%, 2.5:1).

Data availability

The experimental procedures, characterisation data and 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Seyferth, D. The Grignard reagents. Organometallics 28, 1598–1605 (2009).

Knochel, P. et al. Highly functionalized organomagnesium reagents prepared through halogen-metal exchange. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 4302–4320 (2003).

Hoffmann, R. W. The quest for chiral Grignard reagents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 32, 225–230 (2003).

Ashby, E. C. A detailed description of the mechanism of reaction of grignard reagents with ketones. Pure Appl. Chem. 52, 545–569 (1980).

Ashby, E. C. & Bowers, J. R. Organometallic reaction mechanisms. 17. Nature of alkyl transfer in reactions of Grignard reagents with ketones. Evidence for radical intermediates in the formation of 1,2-addition product involving tertiary and primary Grignard reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103, 2242–2250 (1981).

Legros, J. & Figadère, B. Grignard reagents and iron. Phys. Sci. Rev. 3, 1–27 (2017).

Zeng, X. & Cong, X. Chromium-catalyzed transformations with Grignard reagents-new opportunities for cross-coupling reactions. Org. Chem. Front. 2, 69–72 (2015).

Samineni, R., Eda, V., Rao, P., Sen, S. & Oruganti, S. Grignard reagents as niche bases in the synthesis of pharmaceutically relevant molecules. ChemistrySelect 7, 1–12 (2022).

Hoffmann, R. W. & Hölzer, B. Stereochemistry of the transmetalation of Grignard reagents to copper (I) and manganese (II). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 4204–4205 (2002).

Matsuzawa, S., Horiguchi, Y., Nakamura, E. & Kuwajima, I. Chlorosilane-accelerated conjugate addition of catalytic and stoichiometric organocopper reagents. Tetrahedron 45, 349–362 (1989).

Ashby, E. C., Laemmle, J. & Neumann, H. M. The mechanisms of Grignard reagent addition to ketones. Acc. Chem. Res. 7, 272–280 (1974).

Walker, F. W. & Ashby, E. C. Composition of Grignard compounds. VI. Nature of association in tetrahydrofuran and diethyl ether solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 91, 3845–3850 (1969).

Mowat, J., Kang, B., Fonovic, B., Dudding, T. & Britton, R. Inverse temperature dependence in the diastereoselective addition of Grignard reagents to a tetrahydrofurfural. Org. Lett. 11, 2057–2060 (2009).

Parris, G. E. & Ashby, E. C. The composition of grignard compounds. vii. the composition of methyl- and tert-butylmagnesium halides and their dialkylmagnesium analogs in diethyl ether and tetrahydrofuran as inferred from nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 93, 1206–1213 (1971).

Peltzer, R. M., Gauss, J., Eisenstein, O. & Cascella, M. The Grignard reaction – unraveling a chemical puzzle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.9b11829 (2020).

French, W. & Wright, G. F. The significance of halide in Grignard reagents. Can. J. Chem. 42, 2474–2479 (1964).

Carreira, E. M. & Bois, J. Du. (+)-Zaragoza acid c: synthesis and related studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 8106–8125 (1995).

Nicolaou, K. C., Claremon, D. A. & Barnette, W. E. Total synthesis of (±)-Zoapatanol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102, 6611–6612 (1980).

Roberts, J. T. Assymetric Synthesis Using Grignard Reagents. in Handbook of Grignard Reagents (eds. Silverman, G. S. & Akita, P. E.) 557–575 (CRC Press, 1996).

Bartolo, N. D., Read, J. A., Valentín, E. M. & Woerpel, K. A. Reactions of allylmagnesium reagents with carbonyl compounds and compounds with C═N double bonds: their diastereoselectivities generally cannot be analyzed using the Felkin–Anh and chelation-control models. Chem. Rev. 120, 1513–1619 (2020).

Mulzer, J., Pietschmann, C., Buschmann, J. & Luger, P. Diastereoselective Grignard additions to O-protected polyhydroxylated ketones: a reaction controlled by groundstate conformation. J. Org. Chem. 62, 3938–3943 (1997).

Cram, D. J. & Elhafez, F. A. A. Studies in stereochemistry. X. the rule of “steric control of asymmetric induction” in the syntheses of acyclic systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 74, 5828–5835 (1952).

Cram, D. J. & Kopecky, K. R. Studies in stereochemistry. XXX. Models for steric control of asymmetric induction 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 81, 2748–2755 (1959).

Keck, G. E., Andrus, M. B. & Romer, D. R. A useful new enantiomerically pure synthon from malic acid: chelation-controlled activation as a route to regioselectivity. J. Org. Chem. 56, 417–420 (1991).

Trost, B. M. et al. Dinuclear asymmetric Zn aldol additions: formal asymmetric synthesis of fostriecin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 3666–3667 (2005).

Ais, V. D. et al. A convergent approach toward the C1-C11 subunit of phoslactomycins and formal synthesis of phoslactomycin b. Org. Lett. 11, 935–938 (2009).

Bai, X. & Eliel, E. L. Addition of Organometallic Reagents to Acyloxathianes. Diastereoselectivity and Mechanistic Consideration. J. Org. Chem. 57, 5166–5172 (1992).

Righi, G., Pietrantonio, S. & Bonini, C. Stereocontrolled ‘one pot’ organometallic addition-ring opening reaction of α,β-aziridine aldehydes. A new entry to syn 1,2-amino alcohols. Tetrahedron 57, 10039–10046 (2001).

Deng, W. & Overman, L. E. Enantioselective total synthesis of either enantiomer of the antifungal antibiotic preussin (L-657, 398) from (S)-Phenylalanine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 11241–11250 (1994).

Liang, X., Lee, C. J., Zhao, J., Toone, E. J. & Zhou, P. Synthesis, structure, and antibiotic activity of aryl-substituted LpxC inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 56, 6954–6966 (2013).

Takahashi, S. & Nakata, T. Total synthesis of an antitumor agent, mucocin, based on the ‘chiron approach’. J. Org. Chem. 67, 5739–5752 (2002).

Bailey, W. F., Reed, D. P., Clark, D. R. & Kapur, G. N. Grignard reactions of 4-substituted-2-keto-1,3-dioxanes: highly diastereoselective additions controlled by a remote alkyl group. Org. Lett. 3, 1865–1867 (2001).

Takahashi, S. & Kuzuhara, H. Simple syntheses of L-fucopyranose and fucosidase inhibitors utilizing the highly stereoselective methylation of an arabinofuranoside 5-urose derivative. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1, 607–612 (1997).

Kim, K. S. et al. Stereoselective addition of phenyls ulfonylmeihides and methylmagnesium halides to pentodialdo-1.4-furanoses. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 10, 911–915 (1991).

Meanwell, M. et al. A short de novo synthesis of nucleoside analogs. Science 369, 725–730 (2020).

Malek-Adamian, E. et al. Adjusting the structure of 2′-modified nucleosides and oligonucleotides via C4′-α-F or C4′-α-OMe substitution: synthesis and conformational analysis. J. Org. Chem. 83, 9839–9849 (2018).

Yates, M. K. & Seley-Radtke, K. L. The evolution of antiviral nucleoside analogues: a review for chemists and non-chemists. Part II: complex modifications to the nucleoside scaffold. Antivir. Res 162, 5–21 (2019).

Nikam, R. R., Harikrishna, S. & Gore, K. R. Synthesis, structural, and conformational analysis of 4′-C-Alkyl-2′-O-ethyl-uridine modified nucleosides. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 924–932 (2021).

Kirby, K. A. et al. Effects of substitutions at the 4’ and 2 positions on the bioactivity of 4’-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2’-deoxyadenosine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 6254–6264 (2013).

McLaughlin, M. et al. Enantioselective synthesis of 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine (EFdA) via enzymatic desymmetrization. Org. Lett. 19, 926–929 (2017).

Wang, G. et al. Synthesis and anti-HCV activities of 4′-Fluoro-2′-Substituted uridine triphosphates and nucleotide prodrugs: discovery of 4′-fluoro-2′- C-methyluridine 5′-phosphoramidate prodrug (AL-335) for the treatment of hepatitis C infection. J. Med. Chem. 62, 4555–4570 (2019).

Guinan, M., Benckendorff, C., Smith, M. & Miller, G. J. Recent advances in the chemical synthesis and evaluation of anticancer nucleoside analogues. Molecules 25, 2050 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. 4′-C-trifluoromethyl modified oligodeoxynucleotides: synthesis, biochemical studies, and cellular uptake properties. Org. Biomol. Chem. 17, 5550–5560 (2019).

Liboska, R. et al. 4′-Alkoxy oligodeoxynucleotides: a novel class of RNA mimics. Org. Biomol. Chem. 9, 8261–8267 (2011).

Wang, G., Middleton, P. J., Lin, C. & Pietrzkowski, Z. Biophysical and biochemical properties of oligodeoxynucleotides containing 4′-C- and 5′-C-substituted thymidines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 9, 885–890 (1999).

We note that while this work was in revision, a closely related process was reported by Meanwell in this journal, Nuligonda, T. et al. An enantioselective and modular platform for C4ʹ-modified nucleoside analogue synthesis enabled by intramolecular trans-acetalizations. Nat. Commun. 15, 7080 (2024).

Bergeron-Brlek, M., Teoh, T. & Britton, R. A tandem organocatalytic α-chlorination-aldol reaction that proceeds with dynamic kinetic resolution: a powerful tool for carbohydrate synthesis. Org. Lett. 15, 3554–3557 (2013).

Suri, J. T., Ramachary, D. B. & Barbas, C. F. Mimicking dihydroxy acetone phosphate-utilizing aldolases through organocatalysis: a facile route to carbohydrates and aminosugars. Org. Lett. 7, 1383–1385 (2005).

Meanwell, M. et al. Diversity-oriented synthesis of glycomimetics. Commun. Chem. 4, 1–9 (2021).

Crotti, S., Bertolini, F., Di Bussolo, V. & Pineschi, M. Regioselective copper-catalyzed alkylation of [2.2.2]-acylnitroso cycloadducts: remarkable effect of the halide of Grignard reagents. Org. Lett. 12, 1828–1830 (2010).

Kobayashi, Y., Nakata, K. & Ainai, T. New reagent system for attaining high regio- and stereoselectivities in allylic displacement of 4-cyclopentene-1,3-diol monoacetate with aryl- and alkenylmagnesium bromides. Org. Lett. 7, 183–186 (2005).

Li, S., Miao, B., Yuan, W. & Ma, S. Carbometalation-carboxylation of 2,3-allenols with carbon dioxide: a dramatic effect of halide anion. Org. Lett. 15, 977–979 (2013).

Fuji, K., Tanaka, K., Ahn, M. & Mizuchi, M. Diastereoselectivity in addition of methylmagnesium halide to benzoylformate of chiral 1,1’-binaphthalene-2,2’-diol. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 42, 957–959 (1994).

Bartolo, N. D. et al. Diastereoselective additions of allylmagnesium reagents to α-substituted ketones when stereochemical models cannot be used. J. Org. Chem. 86, 7203–7217 (2021).

Giuliano, R. M. & Villani, F. J. Stereoselectivity of addition of organometallic reagents to pentodialdo-1,4-furanoses: synthesis of 1-axenose and d-evermicose from a common intermediate. J. Org. Chem. 60, 202–211 (1995).

Chung, J. Y. L. et al. Kilogram-scale synthesis of 2′- C-Methyl- arabino-uridine from uridine via dynamic selective dipivaloylation. Org. Process Res. Dev. 26, 698–709 (2022).

Maddaford, A. et al. Synthesis of enantiomerically pure 4-substituted riboses. Synlett 20, 3149–3154 (2007).

Mori, T. & Kato, S. Analytical RISM-MP2 free energy gradient method: application to the Schlenk equilibrium of Grignard reagent. Chem. Phys. Lett. 437, 159–163 (2007).

Tuulmets, A., Pällin, V., Tammiku-Taul, J., Burk, P. & Raie, K. Solvent effects in the Grignard reaction with alkynes. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 15, 701–705 (2002).

Peng, Q., Duarte, F. & Paton, R. S. Computing organic stereoselectivity-from concepts to quantitative calculations and predictions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 6093–6107 (2016).

Luchini, G., Alegre-Requena, J. V., Funes-Ardoiz, I., Paton, R. S. & Pollice, R. GoodVibes: automated thermochemistry for heterogeneous computational chemistry data. F1000Research 9, 291 (2020).

Cee, V. J., Cramer, C. J. & Evans, D. A. Theoretical investigation of enolborane addition to α-heteroatom- substituted aldehydes. Relevance of the Cornforth and polar Felkin-Anh models for asymmetric induction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 2920–2930 (2006).

Bickelhaupt, F. M. & Baerends, E. J. Kohn-Sham density functional theory: predicting and understanding chemistry. Rev. Comput. Chem. 15, 1–18 (2000).

Yadav, J. S., Swamy, T., Subba Reddy, B. V. & Ravinder, V. Stereoselective synthesis of C19-C27 fragment of bryostatin 11. Tetrahedron Lett. 55, 4054–4056 (2014).

Cleator, E., McCusker, C. F., Steltzer, F. & Ley, S. V. Grignard additions to 2-uloses: synthesis of stereochemically pure tertiary alcohols. Tetrahedron Lett. 45, 3077–3080 (2004).

Huxley, C. et al. Efficient protocol for the preparation of α-heteroaryl acetaldehydes. Can. J. Chem. 1–4 https://doi.org/10.1139/cjc-2022-0275 (2023).

Davison, E. K. et al. Practical and concise synthesis of nucleoside analogs. Nat. Protoc. 17, 2008–2024 (2022).

Acknowledgements

R.B. acknowledges support from the Canadian Glycomics Network (Strategic Initiatives Grant CD-81), the Consortium de Recherche Biopharmaceutique (CQDM Quantum Leap Grant), Merck & Co., Inc., and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada (Discovery Grant, RGPIN-2019-064680). We also acknowledge the Digital Research Alliance of Canada for access to the Cedar cluster. J.B.-F. acknowledges DGTIC-UNAM for access to the supercomputer Miztli and to Mrs. Citlalit Martínez-Soto for local IT maintenance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M. developed the methods, G.M., G.C.-G., T.M., M.N, Y.P., C.H., A.K. and S.S. performed the experiments, G.C.-G. and J.B.-F. carried out the computational studies, L.C.-C. and R.B. were responsible for project administration, R.B. and G.M. conceptualised the research, L.C.-C. and R.B. supervised the execution of experiments, and G.M., G.C.-G. and R.B. wrote the original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Wenquan Yu and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muir, G., Caballero-García, G., Muilu, T. et al. Unmasking the halide effect in diastereoselective Grignard reactions applied to C4´ modified nucleoside synthesis. Nat Commun 16, 1679 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56895-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56895-7