Abstract

Current strategies to tailor the formation of nanoparticle clusters require specificity and directionality built into the surface functionalization of the nanoparticles by involved chemistries that can alter their properties. Here, we describe a non-disruptive approach to place nanomaterials of different shapes between nanosheets, i.e., nano-sandwiches, absent any pre-modification of the components. We demonstrate this with metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and silicon oxide (SiO2) nanoparticles sandwiched between graphene oxide (GO) nanosheets, MOF-GO and SiO2-GO, respectively. For the MOF-GO, the MOF shows significantly enhanced conductivity and retains its original crystallinity, even after one-year exposure to aqueous acid/base solutions, where the GO effectively encapsulates the MOF, shielding it from polar molecules and ions. The MOF-GOs are shown to effectively capture CO2 from a high-humidity flue gas while fully maintaining their crystallinities and porosities. Similar behavior is found for other MOFs, including water-sensitive HKUST-1 and MOF-5, promoting the use of MOFs in practical applications. The nanoparticle sandwich strategy provides opportunities for materials science in the design of nanoparticle clusters consisting of different materials and shapes with predetermined spatial arrangements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sandwiched constructs with layers of one material wrapping a second core material are found in many disciplines. For example, the magic-angle twisted tri-layered graphene leads to superconductivity1 and β-sandwich proteins can reliably carry out a variety of biological functions2. Given the property enhancements seen by sandwiching nanomaterials, here we probe whether similar property enhancements, e.g., conductivity and stability, can be achieved by sandwiching MOFs nanoparticles between GO nanosheets, i.e., MOF-GOs, that would be highly desired for electrocatalysis or as supercapacitors3. With more than 90,000 metal-organic frameworks having high surface areas, tunable porosities, and functionalities, applications including gas storage4,5,6, separation7,8,9,10,11,12, catalysis13,14,15,16,17,18,19, and sensing20,21,22 have emerged. However, the precise control of the co-assembly of these nanoscale building blocks without modification is difficult23,24,25,26, making the fabrication of MOF-GO nano-sandwiches challenging.

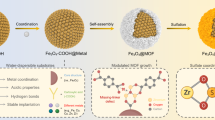

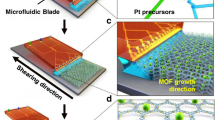

Here, we show a non-disruptive strategy for the co-assembly of nanoparticles to form nano-sandwiches without the need for the pre-modification of the building blocks, as schematically shown in Fig. 1a. A substrate is introduced to selectively bind one component (denoted F), leaving only the opposite side of the bound component F available for further assembly. The other component (denoted as C) selectively binds to F via specific or non-specific interactions, such as electrostatic interaction, dipole-dipole, π-stacking and hydrophobic interactions27. Components F and C can be sequentially introduced to achieve the selectivity, so that nano-sandwiches can be obtained exclusively after the removal of the substrate. To demonstrate our strategy, we select ice as the substrate because GO can selectively bind to the ice surface by specific attractive interactions28 and a confined environment can be achieved in the space between ice grains29,30 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Ice, of course, can be easily removed after the co-assembly. We term this process the confined freeze assembly. This strategy greatly facilitates the fabrication of nanostructured materials that are not limited by specific molecular pairing or recognition, and can also guide the development of other functional materials.

a Scheme of the fabrication process of nano-sandwiches by confined freeze assembly. b SEM images of the randomly assembled MOF-GO composites. c Ultramicrotomy of ZIF-8-GO for TEM study. d, e Electron tomography and SEM images of the ZIF-8-GO nano-sandwich. f Digital photographs of four MOF-GO nano-sandwiches to verify the generality of the strategy and potential for the upscaling. g Ordered nanoparticles with different degrees of assembly. Scale bar, 500 nm.

Results

Characterization of nano-sandwiches

Ultramicrotomy of ZIF-8-GO nano-sandwiches for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) study shows that nanoparticles of a typical MOF material, ZIF-8, can be assembled with GO nanosheets (Fig. 1c). To further consolidate the nanostructure of ZIF-8-GO nano-sandwiches, we used TEM for electron tomography (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Movie 1). The assembly of MOF nanoparticles with GO nanosheets into discrete MOF-GO nano-sandwiches was confirmed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 4), confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). In strong contrast, a random assembly without control yields the non-uniform aggregation of MOF and GO, in agreement with ref. 31. (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 4g). To verify the generality of this approach, four representative MOFs, i.e., acid-sensitive ZIF-8, alkali-sensitive UiO-66, water-sensitive HKUST-1 and MOF-5, were chosen for the construction of different types of MOF-GO sandwiches (Fig. 1f). In addition to MOF-GO sandwiches, SiO2-GO sandwiches were also produced, as verified with CLSM (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Note the uniform composite nanoparticles with different stacking degrees in an ABAB-type stacking pattern. The degree of stacking can be controlled by changing the dimensions of the imposed confinement volume by adjusting the concentration (Fig. 1g, Supplementary Fig. 7).

Confined freeze assembly of nano-sandwiches

As shown in Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Fig. 5, CLSM images of green FITC-labeled GO nanosheets and red MOF nanoparticles (UiO-66 stained with rhodamine B) are found to be randomly distributed before the assembly, while the green GO nanosheets are almost completely located on the ice interface after the assembly. We note that the orange dots on the ice interface indicate MOF-GO nano-sandwiches, confirming the sandwiching of MOF nanoparticles with GO nanosheets and further supporting that the assembly occurs specifically at the ice interface. To gain insights into the sandwiching process, the yield of ZIF-8-GO nano-sandwiches as a function of the molar ratios, \(\gamma\), between the GO nanosheets and MOF nanoparticles (NGO:NMOF) was analyzed. As shown in Fig. 2c, fixed molar concentrations of ZIF-8 nanoparticles were assembled with GO nanosheets of varying concentrations to have different \(\gamma\); and it shows that the yield increases as the \(\gamma\) increases from 0.5 to 2; while further increasing the concentration of GO nanosheets cannot further increase the yield, indicating that one MOF nanoparticle can be maximally covered by two GO nanosheets of comparable size. This is confirmed experimentally, where the NGO was fixed while the NMOF increased, as shown in the inset of Fig. 2c. The productivity (η) of MOF-GO nano-sandwiches is defined as the ratio of actual yield to theoretical maximum yield and is calculated as follows:

a, b CLSM images of the distribution of nanoparticles before and after the assembly. Inset, scale bar, 2 μm. MOF, red; GO, green; MOF-GO, orange; ice, gray. c Fixed concentrations of ZIF-8 nanoparticles were assembled with GO at different concentrations, and the inset showed fixed concentrations of GO were assembled with ZIF-8 at different concentrations. Each yield was averaged from 50 independent experiments. Error bars are the standard errors of the mean. d The relation between molar concentration of initial MOF and the yield of the nano-sandwiches per unit area on the ice surface. Each yield was averaged from 50 independent experiments. Error bars are the standard errors of the mean. e Free energy profile for the transfer of GO with the oxidation degree of 24% from the bulk water to the (100) crystal plane of ZIF-8. Characteristic snapshots of the system from MD trajectory are also shown. f The effect of oxidation degree of GO in equilibrium distance between the GO and the MOF surface and the dissociation energy. g Schematic diagram of the three-step assembly process of the MOF-GO nano-sandwiches. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8, \(\eta\) for MOF-GO nano-sandwiches ranges from ≈0.4 to 0.6 at cZIF-8 = 1.61 pM, cZIF-8 = 2.15 pM, or cGO = 3.21 pM. In strong contrast, the calculation predicts almost zero yield and productivity (Supplementary Note 1) if the GO nanosheets and MOF particles are assembled randomly, e.g., in the bulk solution. The high yield and productivity of GO-MOF nano-sandwiches shows that GO and MOFs can be precisely sandwiched by the confined freeze assembly strategy.

Please note that the yield of MOF-GO nano-sandwiches was nearly identical at cZIF-8 = 1.61 pM and cZIF-8 = 2.15 pM (Fig. 2c), indicating that there is a saturation in the yield independent of cGO or cMOF. We further investigated the relationship between cMOF and the yield of the MOF-GO nano-sandwiches for systems with different ice surface areas with \(\gamma\) = 2 (inset of Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 9). We found that the yield of MOF-GO nano-sandwiches gradually saturates with increasing cMOF for all systems. Figure 2d shows the yields of the MOF-GO nano-sandwiches per unit area of ice surface as a function of cMOF. Independent of the ice surface area, we found a one-to-one correspondence between the yield per unit area (A) and cMOF, further verifying that the MOF-GO nano-sandwiches are formed on the surface of ice crystals.

To gain molecular level insights into the mechanism underlying the formation of MOF-GO nano-sandwiches, we calculated the free energy profile (FEP) for the assembly of MOF nanoparticles with GO nanosheets of varying degrees of oxidation (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 10e, f). The (100) crystal plane of ZIF-8 is adopted here as a representative surface, since it is the primary exposed facet in solution32,33. For all three FEPs, as the distance between the MOF surface and the GO increases, the free energy first decreases and minima are observed from 3 to 6 Å, indicating that GO preferentially binds to the MOF surface independent of the degree of oxidation. The free energy then increases to a plateau, indicating that the assembly of GO nanosheets onto the ZIF-8 surface is thermodynamically favored and spontaneous. Similar trends can be observed for the ZIF-8 (110) (Supplementary Fig. 11a). The spontaneous assembly of MOF nanoparticles with GO nanosheets is further supported by classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (Supplementary Fig. 11b). When the GO nanosheet is initially placed ≈ 10.0 Å away from the MOF nanoparticle, it is gradually driven toward the surface of the MOF nanoparticle; and after ≈ 300 ns, the GO nanosheet is in close contact with the surface of the MOF nanoparticle.

The energy barrier of the GO moving from the MOF surface to the bulk water can be regarded as the dissociation energy between MOF and GO. Both the MOF and GO are neutral in our MD simulations, meaning that the interaction between GO and MOF is primarily driven by two factors: (1) electrostatic interactions due to the polarity of the GO and MOF surfaces; and (2) hydrophobic interactions between GO and MOF. A higher dissociation energy indicates stronger interactions between MOF and GO. As shown in Fig. 2f, the dissociation energy increases from 4.0 to 8.9 to 11.0 kcal mol-1 as the oxidation degree of GO increases from 24% to 36% to 48%. The higher the degree of oxidation, the more hydrophilic is the GO; however, the MOF-GO interactions become stronger, suggesting that the binding of MOF nanoparticles with GO nanosheets is driven by electrostatic interactions. As the degree of oxidation of GO increases, its polarity increases, increasing the electrostatic interaction. In addition, as the degree of oxidation of GO increases, GO has more oxidized functional groups that increases the equilibrium distance between the GO and the MOF. These simulations map onto the experimental results, i.e., the stability first increases and then decreases with increasing degree of oxidation (Supplementary Fig. 10, Supplementary Note 2), and the binding interaction and equilibrium distance between the GO and the MOF surface increase, while more defects are generated. At low degrees of GO oxidation, binding interactions dominate and the stability increases with increasing GO oxidation. In contrast, at a high degree of GO oxidation, there is an increase in defects, leading to a decrease in stability. In addition to defects, the equilibrium distance may be another reason for the decrease in the stability, as various polar molecules and ions may adsorb to the MOF surface with increasing the separation distance.

Indeed, not all nanoparticles follow the same electrostatic interaction mechanism. Specifically, the oxidized functional groups on GO are negatively charged, and if the outermost layer of the interface is also negatively charged, repulsive forces may prevent self-assembly. At this time, a suitable pH is required to adjust the charge for assembly (Supplementary Fig. 12). For SiO2, we calculated the charge distribution on its (111) facet, selected for its low surface energy and stability. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 12b, the outermost atomic layer consists of 36 Si and 72 O atoms, with a total Mulliken charge of +1.09 e. Given that the oxidized groups on the GO surface are predominantly negatively charged, the electrostatic interactions between the (111) facet of SiO2 and GO can facilitate the self-assembly of the nano-sandwich structure (Supplementary Fig. 7b). In addition, to understand the influence of GO sheet thickness on the assembly and stability, we fabricated five GO nanosheets with varying thicknesses, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 13. For conventionally obtained GO sheets with a thickness range of 0.8–1.8 nm, both the yield and the N2 uptake after acid treatment are high, indicating enhanced assembly efficiency and stability. This is likely due to the nanosheets’ ability to form close contact and effective encapsulation. In contrast, the ultrathin GO nanosheets (less than 0.7 nm) show poor structural integrity and lower stability. For thicker GO sheets (over 2 nm), increased rigidity and reduced flexibility prevent the close encapsulation, reducing the protective effect on MOFs and thus lowering stability (Supplementary Fig. 13). These findings underscore the critical role of GO thickness in achieving effective assembly and stability.

Based on the above experimental and MD simulation results, the formation mechanism of MOF-GO nano-sandwiches can be described as follows: the concentrations of GO nanosheets and MOF nanoparticles among ice crystal grains gradually increase during the confined freeze assembly. GO nanosheets first bind to the ice crystal surface by hydrogen bonding between the OH groups on the GO nanosheets and the oxygen atom on the ice surface34,35. Then, MOF nanoparticles bind to the GO surface by electrostatic interaction. As the assembly continues, the concentration of GO nanosheets further increases, and another GO nanosheet binds to the surface of the MOF-GO assemblies on the ice surface, forming MOF-GO nano-sandwiches, as schematically shown in the Fig. 2g and Supplementary Movie 2. The peculiarity of the assembly of MOF and GO among ice crystal grains by the confined freeze assembly strategy is that the ice surface can differentially adsorb GO nanosheets, due to the matching of the lattice parameters of the ice crystals with the arrangement of OH groups on the GO surface36. The concentrations of GO and MOF nanoparticles in the confined environment can be controlled, e.g., by tuning the assembly temperature and the initial concentration of nanoparticles (Supplementary Fig. 9). In addition, the diffusion of GO and MOF nanoparticles, as well as water among the ice grains is very slow at low temperatures, allowing effective control of the assembly process36. Consequently, undesired agglomerates of MOF nanoparticles and GO nanosheets among ice crystal grains can be effectively avoided (Supplementary Fig. 4), which is challenging in the bulk solution.

Molecular mechanism for improved stability

As a typical MOF material, ZIF-8 is composed of tetrahedrally-coordinated zinc ions connected by four 2-methylimidazolate linkers. ZIF-8 has great alkaline stability, while it is unstable in acidic environments37,38. The chemical stability of MOF-GO nano-sandwiches was tested using commonly accepted test conditions for MOFs39. The powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) pattern and N2 adsorption showed that the MOF in the MOF-GO nano-sandwiches retains its crystallinity and porous structure even after exposure to boiling water for over 7 days or incubated in acidic aqueous solution (pH = 2) for over one year at room temperature (Fig. 3a, b). Interestingly, freshly prepared ZIF-8-GO nano-sandwiches show a ≈ 13% increase in N2 adsorption compared to the unsandwiched ZIF-8 (Fig. 3b), possibly due to the formation of the mesopores at the interface of MOFs and GOs (Supplementary Fig. 14). Please note that physically mixed ZIF-8 and GO nanocomposites in bulk solutions are stable for less than 7 days in acidic environments (pH = 2) (Supplementary Fig. 4). Furthermore, the mechanical and thermal stabilities can also be significantly enhanced by the protection from GO armor (Supplementary Figs. 15–17).

a, b Powder X-ray diffraction experiments and N2 adsorption isotherm showed the stability of ZIF-8-GO nano-sandwiches after exposure to dilute hydrochloric acid (pH = 2) and boiling water. c Energy profiles associated with a linker vacancy formation reaction in bulk (black dashed line) and on (100) crystal surface (blue dashed line) between ZIF-8 with HCl/H2O. The reaction consists of two steps. In the first step (labeled I), a HCl molecule is adsorbed onto Zn cations and then breaks a Zn-N bond by donating a proton to the N of the ligand to form a dangling linker. In the subsequent step (labeled II), a water molecule attaches to Zn and attacks a second Zn-N bond to generate a protonated organic ligand. Molecular (atomic) densities of ZIF-8 (black line), water (blue line), GO (purple line), Cl- (green line), and H3O+ (red line) obtained from the MD simulation of ZIF-8 in solution without (d) and with (e) a GO nanosheet. Snapshots of the simulated system at t = 300 ns from MD simulation of ZIF-8 in solution without (f) and with (g) the GO nanosheet. h Optical image and inserted schematic of the two-electrode device. i Conductivity of ZIF-8-GO with different oxidation degrees. Each conductivity was averaged from 50 independent experiments. Error bars are the standard errors of the mean. j Conductivity of ZIF-8-GO nano-sandwiches after harsh treatment (pH = 2). Each conductivity was averaged from 50 independent experiments. Error bars are the standard errors of the mean. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further explore the molecular mechanism underlying the enhanced stability of MOF-GO nano-sandwiches, we performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations to investigate how a ZIF-8 crystal degrades. Previous studies have shown that ZIF-8 degrades in a two-step reaction to form a linker vacancy (LV) (Supplementary Fig. 18)33,40. In the first step (labeled I), an HCl or H2O molecule is adsorbed onto Zn cations, which subsequently causes a Zn-N bond to break by donating a proton to the N of the ligand to form a dangling linker (DL). In the next step (labeled II), a water molecule attaches to Zn and attacks a second Zn-N bond to generate a protonated organic ligand (HL). It is obvious that DLs emerge initially and that other defects form afterwards. The energy profiles related to LV formation in bulk ZIF-8 and on its surface for HCl and H2O are shown in Fig. 3c. In general, surfaces of MOF particles exhibit much higher reactivity than bulk structures because metal cations on the MOF surfaces have intrinsically lower coordination numbers than bulk structures. The DL formation in bulk and at the surface induced by H2O is endothermic, indicating that ZIF-8 is stable in the humid environment. When triggered by HCl, DL production in bulk ZIF-8 is exothermic, but the reaction is practically unachievable because of the high energy barrier (28.4 kcal mol-1). Please note that steps I and II of LV formation on the ZIF-8 surface are exothermic, and the energy barriers of 4.3 and 16.7 kcal mol-1, respectively, are much lower than that of the bulk. These calculations show that ZIF-8 is unstable in acidic environments and the degradation initiates from the external surfaces. In other words, protecting ZIF-8’s surface is essential for stabilizing ZIF-8.

We performed classical MD simulations to further explore the molecular level mechanism of GO nanosheets on stabilizing MOF nanoparticles. The densities of MOF (black line), water (blue line), GO (purple line), Cl- (green line), and H3O+ (red line) ions at ≈300 ns for the system without and with sandwiched by GO nanosheets obtained from our MD simulations (Fig. 3d, e). The MOF surface can directly interact with water molecules in the absence of GO nanosheet, indicating that the exposed MOF surface is easily attacked by polar molecules or ions. In contrast, in the presence of the GO nanosheet, the density profiles of MOF and water molecules (along with other ions) are separated from each other, showing that the GO layers can act as an ‘armor’ against water molecules, Cl- and H3O+ ions (Fig. 3f, g, Supplementary Fig. 19). Further DFT calculations reveal that the oxygenated groups of GO can block the reaction and stabilize the MOF even when acidic molecules enter the MOF-GO interface (Supplementary Fig. 20).

The reason for the sandwich structure, rather than a fully coated structure, is to ensure high stability while allowing gas molecules like CO2 and N2 to pass through, so there is a fraction of surface area that is not covered by GO. Please note that the exposed MOF external surface of the MOF-GO nano-sandwiches can be tuned by adjusting the size of the GO with respect to that of MOF. Experimental results showed that uncovered MOF surface degrades, but can eventually be stabilized when the uncovered area is small (Supplementary Fig. 21). We hypothesize that some protonated organic linkers are released when ZIF-8-GO degrades initiating from the uncovered area. These protonated organic linkers are enriched near the uncovered MOF surface (Supplementary Figs. 22, 23) to coordinate with metal ions on the surface of the exposed MOF (Supplementary Fig. 21), which can resist the further attack of polar molecules and ions, as suggested by our DFT calculations. Thus, the uncovered MOF surface can be stabilized. The GO armor and protonated organic linkers together ensure the high stability of MOF-GO nano-sandwiches, and the unsealed area ensures effective penetration of the target molecules (Supplementary Fig. 24).

Enhanced stability and conductivity

The electrical conductivity of the material was tested using a simple two-contact method41 at room temperature. To reduce the contact resistance, gold electrodes were deposited on ZIF-8-GO wires tightly packed in grooves of an insulated SiO2 template and square copper grids were used as a shadow mask (Fig. 3h and Supplementary Fig. 25). The conductivity of GO varies greatly with the degree of oxidation, with lower oxidation GOs having fewer defects and higher conductivity. The conductivity of the reduced ZIF-8-GO nano-sandwiches is 5–6 orders of magnitude higher than that of ZIF-8 (Fig. 3i). The conductive reduced GO is tightly coupled with the abundant pores on the MOF surface, providing a large number of electron transfer channels. By adjusting the degree of oxidation, the electrical properties of the nano-sandwich can be tuned over a wide range, making it promising for use as a chemiresistive sensor, supercapacitor, or battery. In addition, chemical stability is a vital factor for electrochemical applications42. The ZIF-8-GO nano-sandwich still has stable electrical conductivity after treatment under harsh conditions (Fig. 3j).

Prior to evaluating the MOF-GO nano-sandwiches as potentials in wide-ranging applications involving gas storage, separation, catalysis, and chemical sensing, we assessed the chemical stability of three other representative MOF-GO nano-sandwiches, i.e., the alkali-sensitive UiO-66, water-sensitive HKUST-1 and MOF-5, in addition to the acid-sensitive ZIF-8, after being sandwiched with GO nanosheets, by monitoring the corresponding PXRD patterns. No loss of crystallinity of UiO-66-GO and HKUST-1-GO was observed during the exposure for over one year (Fig. 4a, b). The chemical stability of MOF-GO was supported by maintaining the N2 adsorption uptake capability and structural integrity by immersing the UiO-66-GO and HKUST-1-GO in acid/base or aqueous solutions over a year (Fig. 4d, e). Moreover, we evaluated the hydrolytic stability of MOF-5-GO via PXRD and gas-sorption measurements. The crystallinity and porosity of MOF-5-GO were maintained under 75% relative humidity (RH) for three months, revealing its high chemical stability (Fig. 4c, f). As a contrast, the pristine MOFs decomposed under the same harsh environment (Supplementary Figs. 26, 27). The above results confirmed that the MOF-GO nano-sandwiches can achieve simultaneously the stability in acid, alkali and water environments.

a–c Powder X-ray diffraction experiments and d–f N2 adsorption isotherm to designate the stability of MOF-GO nano-sandwiches after exposure to the harsh environment in which non-sandwiched MOFs are unstable. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

CO2 capture from simulated flue gases

Based on the great porosity and stability of the four representative MOF-GO nano-sandwiches, we investigated the feasibility of using this strategy to increase the stability of porous materials for the challenging application of CO2/N2 (15/85, v/v) separation under high-humidity conditions, to combat rising CO2 emissions in the global climate43. All four MOF-GO nano-sandwiches exhibited great separation performance for the efficient CO2 capture from the flue gas under high humidity (RH = 75%) (Fig. 5a–d, Supplementary Fig. 28a–d). Especially for the water-sensitive MOF-5 and HKUST-1, the stability of the armor-protected materials has been significantly improved. The tailor-made GO armor fully prevented the degradation in harsh environments during the CO2 separation; as a result, MOF-5-GO and HKUST-1-GO can effectively capture CO2 from the high-humidity gas flows, and there is no obvious performance loss even after 200 continuous separation cycles. Furthermore, during the CO2 capture from flue gases, there is usually a trace amount of acidic or alkaline molecules (NH3 or SO2, etc.), so we further investigated their CO2 separation under harsh conditions. ZIF-8 and UiO-66 caused structural damage under these harsh conditions. While ZIF-8-GO and UiO-66-GO nano-sandwiches can effectively capture CO2 from these simulated acidic or alkaline flue gases, there is no apparent degradation in performance after ten continuous separation cycles (Fig. 5e, f, Supplementary Fig. 29). High-resolution transmission electron microscopy images showed that the crystalline structures of the MOF-GO sandwiches were intact after the column breakthrough tests (Fig. 5g–j, Supplementary Fig. 30). In comparison, the unprotected MOF-5 and HKUST-1 showed structural damage under high humidity, and the performance was lost after 2 or 3 separation cycles (Supplementary Fig. 28g, h). Compared with other post-modification methods, our strategy can not only render the MOF materials with enduring stability even over a period of one year, but also exhibits significant superiority in preserving the inherent porosity of MOF nanoparticles under harsh conditions (Supplementary Fig. 31, Supplementary Tables 1, 2). As sandwiching the MOF nanoparticles with GOs is a universal strategy, enabling the MOFs nano-sandwiches to have extensive potential for the industrial applications of MOFs in harsh environments.

a–d Experimental column breakthrough curves for humid CO2/N2 separations. e ZIF-8 and ZIF-8-GO nano-sandwiches under humid CO2/N2 column breakthrough tests, both of which were treated with H2SO4 solution (pH = 2) for 12 h before each cycle. f UiO-66 and UiO-66-GO nano-sandwiches under humid CO2/N2 column breakthrough tests, both of which were treated with ammonia solution (pH = 12) for 12 h before each cycle. g–j TEM images of MOF and MOF-GO nano-sandwiches after cycles of CO2 separation under humid conditions (75% RH). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

In summary, we describe a self-guided approach to sandwich nanomaterials of different shapes between graphene oxide nanosheets without any surface modification of the nanomaterials to alter their properties. The sandwich structures can provide significant property enhancements, e.g., conductivity and stability, which are highly desirable for nanoparticles such as MOFs. Compared to the traditional full encapsulation strategy, the sandwich strategy can improve the properties of the nanoparticles while still effectively exploiting the advantages of the nanoparticles themselves. The sandwich strategy of nanoparticles opens up possibilities for materials science to design nanoparticle clusters of different materials and shapes with predetermined spatial arrangements.

Methods

Preparation of GOs of controllable sizes

The aqueous dispersion of GOs (purity > 95%, lateral size 0.1–3 μm) prepared by a modified Hummers method44 with a broad size distribution was purchased from Nanjing XFNANO Materials Tech Co., Ltd. The size-disperse GO dispersions were sorted into multiple different groups with specific size via fractional centrifugation. First, the GO dispersion was centrifuged at 1765.1 × g for 30 min at 10 °C using a centrifuge (GL-20-2), dividing the solution into supernatant and precipitate to remove carbon impurities. The supernatant was centrifuged again at 6283.2 × g for 10 min; then the supernatant obtained from the second round of centrifugation was successively centrifuged at 7013.6, 10812.6, 15109.4, 21333.1, and 28220.7 × g for 10 min. To measure the lateral size of GO nanosheets, the droplets of GO were dropped on the silicon wafer and air dried. The lateral size distributions of GO were obtained by counting more than 500 sheets for each sample on the AFM images (Supplementary Fig. 1). The supernatant fractionated at 28220.7 × g was centrifuged at 10812.6 × g for 10 min to collect the precipitates (Supplementary Fig. 2). If the size uniformity of the attained GO was not ideal, the above steps can be repeatedly performed to yield the uniform GO. Proper initial concentration of GO was more efficient for separation (e.g., 0.1 mg mL-1).

The above method was suitable for GO sheets with a size larger than 400 nm. For smaller sizes of GO (100 and 200 nm), we used Ultracel membranes with the 0.1-µm and 0.22-µm cutoff microfiltration membrane to filter commercial GOs, respectively. The obtained GO fraction was immersed in water and stored at 4 °C to prevent coalescence.

Preparation of MOF-GO nano-sandwiches

MOF (ZIF-8, purity > 95%) nanoparticles with different sizes were prepared by manipulating the amount of ligands and surfactants (Supplementary Fig. 1)45. MOFs and GOs were then assembled. The average size of GO sheets is ≈ 1.2 times that of MOF particles (Supplementary Fig. 1). Small droplets of GO and MOF (ZIF-8, UiO-66, HKUST-1 and MOF-5) dispersions (0.1 mg mL-1) were alternately dropped on a super-cold substrate (cooled in liquid nitrogen) from the height of 1.5 m, with a volume ratio of 9:1, for quenching to form small polycrystalline ice crystals, and then the ice crystals were annealed at a higher temperature (e.g., −20 °C) for 2 h. For batch preparation, solutions of GO nanosheets and MOF nanoparticles were quickly quenched to generate small polycrystalline ice crystals. Upon quenching at the temperature of liquid nitrogen, heterogeneous ice nucleation occurred and consequently to yield high amount of small ice crystals46. During the annealing process, the concentration of nanoparticles between the ice crystals increased with the growth of the ice grains. The moisture-sensitive MOFs were protected from exposure to water and air to the greatest extent possible prior to the confined freezing assembly. Afterward, the ice was removed and the MOF-GO nano-sandwiches were obtained by freeze-drying using a freeze dryer (LGJ-10E).

Preparation of GO and MOF-GO nano-sandwiches with different degrees of oxidation

Graphene oxides with different degrees of oxidation were all prepared based on the modified Hummers method44. With some variation in the dose of oxidant KMnO4 and the oxidation time in each preparation process, four GO samples with different oxidation degrees, as wide an oxygen range as possible, have been obtained and labeled as GO1-4, respectively. Graphene oxide contains various functional groups such as hydroxyl, carboxyl and epoxy group47. The size of the freshly prepared graphene oxide is not uniform, and the smaller size of graphene oxide has a higher oxidation degree48. Therefore, GOs of relatively uniform size were collected via fractional centrifugation to conduct subsequent experiments. The detailed preparation conditions are listed in Supplementary Table 3. MOF-GO nano-sandwiches with different oxidation degrees were prepared according to the MOF-GO nano-sandwich preparation method described above (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Preparation of MOF-GO nano-sandwiches with various GO sheet thickness

To understand the influence of GO sheet thickness on the assembly and stability, we fabricated five GO nanosheets with varying thicknesses, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 13. Based on the production of GO with different thicknesses49, we then sorted into similar sizes using prior temperature-controlled fractional centrifugation, as detailed in above preparation of GOs of controllable sizes. The AFM images in this figure clearly show the differences in thickness (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Preparation of pegylated GO nanosheets labeled with FITC

The suspension of GO nanosheets of uniform size (≈ 500 and 1000 nm) obtained by the above method was functionalized by forming covalent bonds with poly(ethylene glycol-amine) (PEG) to decrease aggregation. Then, PEG-GO nanosheets were covalently labeled with the amine-reactive dye fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) to indicate different assembly stages of MOF and GO50.

Preparation of UiO-66 stained with rhodamine B

The encapsulation of rhodamine B (RhB, ≥98.0%) was fabricated by a common in-fusion method, immersing UiO-66 (purity > 95%) powder (5 mg) into an RhB aqueous solution (5 ppm, 5 mL) at 37 °C for 24 h in a shaker. The product was then cooled to room temperature (25 °C), followed by ultrasonically washing with deionized water for three times and then filtration until the filtrate was colorless to make sure that the unencapsulated RhB was completely removed. Eventually, the product RhB-UiO-66 was dried under vacuum at 80 °C to generate a red powder.

Electron tomography of MOF-GO nano-sandwich

Sample preparation

We specify that the MOF-GO nano-sandwiches were dispersed in ethanol (purity ≥ 99.7%) at a concentration of 0.05 mg mL-1. This dispersion was then applied as a 5 µL drop onto an ultrathin (10 nm thickness) carbon film supported on a copper grid with 100 mesh (Beijing XXBR Technology Co., Ltd). The sample was air-dried in a clean room, allowing the MOF-GO nano-sandwiches to settle on top of the carbon film. Additionally, gold nanoparticles of ≈10 nm in diameter were incorporated as bead markers to facilitate alignment of the tilt series images at different angles, which is essential for accurate electron tomography reconstruction.

2D image collection

Imaging was performed using a Themis 300 transmission electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operating at 200 kV. This setup achieved a magnification of 22,500×, yielding a pixel size of 0.4493 Å per micrograph. Tilt series were recorded automatically from −70° to +63° in 1° increments by using the Ceta S camera, with the software Tomography (Thermo Fisher Scientific), maintaining a defocus of ≈ −3.0 µm, and the tilted images from −63° to +63° with 1° increments were used for reconstruction (shown in Supplementary Fig. 3). From the aligned series of images and Supplementary Movie 3, the MOF-GO nano-sandwich can be observed positioned between two layers of the GO sheets.

Electron tomography of MOF-GO nano-sandwich

To further analyze the structure, we performed an electron tomography reconstruction of the MOF-GO nano-sandwich using the Back Projection (BP) algorithm in IMOD. The resulting BP tomogram (provided as Supplementary Movie 4) and cross-sectional slices (Supplementary Fig. 3b) distinctly reveal the MOF encapsulated by the GO layers. Using the Amira software, we made a segment and enhanced the visualization to generate a detailed image of the GO sheets covering the MOF, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3c and Supplementary Movie 1.

Observation of the confined freeze assembly process

Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) images of the distribution of reactants were applied to indicate pre- and post-assembly. Imaging was conducted at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 568 nm using CLSM (Olympus FV1000). Because the distance between the lens (Linkam LTS420) and the sample in the cryostage exceeded the focal length of the inverted fluorescence microscope, a thermostatic device was constructed by injecting liquid nitrogen into a copper chamber that was insulated with a foam layer. The glass slide containing the frozen droplet was attached to the bottom of the device and observed using a laser confocal microscope. The sample temperature was regulated between -40 and −20 °C by adjusting the thickness of the thermal insulation layer.

Small droplets of 90% v/v FITC-PEG-GO aqueous solutions and 10% v/v ethanol solutions of RhB-UiO-66 were alternately dropped in liquid nitrogen-cooled slides from a height of 1.5 m to generate small ice crystals. This sample was then transferred to the thermostatic device to observe the distribution of FITC-PEG-GO and RhB-UiO-66 prior to assembly using a confocal laser scanning microscope. In addition, the droplets quenched in liquid nitrogen were annealed at −20 °C for 45 min in a cryostage (Linkam LTS420). The same process was carried out to examine the sample after assembly.

Yield calculation of ZIF-8-GO materials

Extra GOs were discarded in water by three times of centrifugations at 1081.3 × g for 10 min in a centrifuge. Uncoated ZIF-8 was multiply rinsed in dilute hydrochloric acid (pH = 2) and then filtered out using microfiltration membrane. The yield of newly obtained ZIF-8-GO nano-sandwiches was then calculated.

Estimation of MOF and GO molar concentrations

Molar concentrations of MOF (ZIF-8) dispersions were estimated from their mass concentrations and the molar mass of MOFs. First, the molecular weight of ZIF-8 of different sizes was estimated based on a previously well-accepted structural model of ZIF-8; that is, the structural formula C1344H672N672Zn192 with the molecular weight of 38787.072 g mol-1 and the size of 61.964 Å in each direction for ZIF-8 cubic cell51. Therefore, the molar mass of ZIF-8 nanoparticle of unit volume MZIF-8,V was calculated as MZIF-8,V = M[ZIF-8 model]/V[ZIF-8 model]. Here, M[ZIF-8 model] and V[ZIF-8 model] are the molar mass and volume (in nm3) of C1344H672N672Zn192, respectively. As revealed by the SEM imaging, the shape of the ZIF-8 with the size of 500 nm was nearly spherical. The average molar mass of ZIF-8 with a certain average size MZIF-8,D was then calculated using MZIF-8,D = 4π/3 × (D/2)3 x MZIF-8,V. D is the average dimension of ZIF-8 measured from SEM images (Supplementary Fig. 1). Based on the average molar mass, the molar concentration of ZIF-8 aqueous dispersion with a known mass concentration was estimated.

AFM nanoindentation test

The AFM (MFP-3D-SA, Asylum) was used to determine Young’s moduli of the materials using an antimony doped Si (RTESPA-525) with the spring constant at 200 N m−1. Particles were indented at a constant force. Standard deviations were calculated from 100 indentation experiments. The modulus values at depths below 50 nm can be disregarded because the large scatter in this regime is caused by imperfect indenter tip-to-sample surface contact52. Therefore, only indentations deeper than 50 nm are considered. Force-displacement curves were analyzed via Hertzian mechanics. Representative force curves are presented in Supplementary Fig. 15.

CO2/N2 breakthrough experiments

Breakthrough experiments for CO2/N2 separation under humid conditions were performed in a home-built apparatus at 298 K, 1 bar, and 75% RH. All samples were crushed and granulated after compression at 3 MPa, and the samples were sieved to obtain small particles with a size of 40–60 mesh. The samples were activated under high vacuum (10−6 bar) for 6 h at 393 K (ZIF-8-GO, UiO-66-GO, HKUST-1-GO) or 473 K (MOF-5-GO). The activated particles of ZIF-8-GO (0.63 g), UiO-66-GO (0.71 g), MOF-5-GO (0.73 g), or HKUST-1-GO (0.67 g) were placed in a stainless-steel column (inner dimensions 4 mm × 75 mm). Before the test, the column was purged with Ar gas at a flow rate of 100 mL min-1 for 1 h at 353 K. Then, the experiments for the separation of CO2/N2 (15/85, v/v) mixtures under 75% RH were carried out at a flow rate of 10 mL min-1 (298 K, 1.01 bar). The eluted gases were monitored by gas chromatography with a thermal conductivity detector (Agilent-490 Micro GC). For experiments with 100 cycles or more, the separation data was collected every 5 or 10 cycles. Prior to each cycle experiment, the column was regenerated by flowing Ar gas through it at a rate of 100 mL min-1 for 30 min at room temperature.

Characterization

Digital photographs were taken with a Nikon eclipse LVDIA-N microscope equipped with a CCD (DS-Ri2). PXRD data were recorded in the angular range of 3 to 50° (2θ) at a scanning speed of 5° min-1 by using an X-ray diffractometer (PANalytical, Netherlands), and the wavelength of the Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54056 Å). Morphologies images were examined at 5 kV using a field-emission SEM instrument of Hitachi S-4800. HRTEM images and corresponding EDX spectral mapping were taken at the acceleration voltage of 200 kV on a JEM-2100F electron microscope. Ultra-thin cutting slice of ZIF-8-GO was prepared to record the HRTEM images. The size distribution of nanoparticles was measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS, Zetasizer nano ZS) to evaluate the mean particle size before and after modification. ZIF-8-GO powder (≈ 10 mg) was pre-embedded with resin for 24 h to form composites. From this composite, thin ZIF-8-GO slices of 20–50 nm thickness were cut by a diamond knife equipped Leica EM Ultramicrotome (Leica EM UC7). The thin slices were then transferred to a copper grid for HRTEM observation. UV-vis spectra were measured with a UV-2800S spectrometer. AFM (Multimode 8, Bruker) was used to investigate the morphology and size of GOs. Water or ethanol was removed by freeze-drying (LGJ-10E). The electrical conductivity of MOF-GO nano-sandwiches was tested by two-point probe station (4200A-SCS). The GO was fractionated by centrifugation. The GO dispersion was centrifuged on a centrifuge (GL-20-2). Specific surface areas of the tested samples were determined using N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms at 77 K (Quantachrome NOVA-3000 system) with the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method. CO2 sorption isotherms at 298 K (Quantachrome, Nova2000e) for pristine and modified HKUST-1 before and after water treatment for 7 days. Prior to the measurement, samples were activated under the corresponding MOF activation conditions.

MD simulations

We employed ZIF-8 (100) and (110) surface models. The periodic model system has a unit cell of 50.6 Å × 50.6 Å in the lateral (x-y) dimensions, and 131.2 Å in the z dimension. DREIDING force field was found to perform well in describing the bulk modulus and linear thermal expansion coefficients of several well-studied MOFs53. In this work, ZIF-8 was described by the DREIDING force field.

A total of 3000 water molecules were placed on top of the ZIF-8 surface. A GO nanosheet with lateral dimensions of 39.1 Å × 35.4 Å was immersed in water molecules. The molecular structure of GO primarily consists of hydroxyl and epoxy groups, which are randomly distributed on both sides of the carbon plane. All carbon atoms on the edge of the sheet are decorated by carboxyl groups. Water molecules were described using the TIP3P model, and GO nanosheets were described using the OPLS force field54. The cross interactions among water, ZIF-8 and GO were calculated by using the Lorentz-Berthelot rule. Periodic boundary conditions were applied in the x-, y-, and z-directions, in which the z-direction is perpendicular to the surface. The NVT ensemble with temperature controlled at 300 K by Nosé-Hoover algorithm was employed. A time constant for temperature coupling of 0.1 ps was employed in the MD simulations. Long range Coulombic interactions were calculated using the Particle-Particle-Particle-Mesh (PPPM) algorithm55. The leap-frog algorithm for integrating Newton’s equations of motion with a time step of 2 fs was selected in the MD simulations. All the classical molecular dynamics simulations were performed using the large-scale atomic molecular massively parallel simulator (LAMMPS) package56. The COLVAR module57 implemented in LAMMPS was utilized to calculate the potential energy of mean force (PMF).

Umbrella sampling (US) method58 was employed to calculate PMF, i.e., the free energy profile of a GO nanosheet moving from the bulk to the ZIF-8 surface. A restoring force in the Z axis is applied to each atom in the GO nanosheet. MD simulations were performed for 10 ns for each window. Data from the last 8 ns were collected and analyzed by the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) to obtain the PMF59.

First-principles calculations

Generalized gradient approximation exchange-correlation functional PBE60 was employed in conjunction with Grimme’s empirical dispersion corrections in DFT calculations61. Double-ζ polarization Gaussian basis set62 was used together with a plane-wave representation truncated at 800 Ry. Goedecker-Teter-Hutter (GTH) pseudopotentials63 were used to model core electrons. The climbing image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method64 was used to locate reaction pathways and their associated transition states. Periodic boundary conditions were exploited in all three directions. All first-principles calculations were carried out using the CP2K program65.

Unit cell structures of ZIF-8 were constructed from XRD crystal structures in the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD)37. Geometry optimization on the structure was performed with its lattice parameters and ionic positions fully relaxed. The optimized unit cell structure was then used to construct bulk and surface models. Here, the (100) surface was used to represent the typical external surface of ZIF-8 due to its relatively high stability against attack from acid gases33. A slab model was utilized to simulate the (100) plane with a vacuum layer of ≈ 15 Å to avoid interactions between periodic image slabs. There are four possible terminations on the ZIF-8 (100) surface, and the one with the lowest surface energy was selected33. Specifically, the Zn atoms in the top layer of the slab model are 3-coordinated. However, due to the highly humid conditions in the experimental environment, the unsaturated Zn atoms were saturated with water molecules.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Park, J. M., Cao, Y., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Jarillo-Herrero, P. Tunable strongly coupled superconductivity in magic-angle twisted trilayer graphene. Nature 590, 249–255 (2021).

Baranova, E. et al. SbsB structure and lattice reconstruction unveil Ca2+ triggered S-layer assembly. Nature 487, 119–122 (2012).

Jahan, M., Bao, Q. & Loh, K. P. Electrocatalytically active graphene-porphyrin MOF composite for oxygen reduction reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 6707–6713 (2012).

Eddaoudi, M. et al. Systematic design of pore size and functionality in isoreticular MOFs and their application in methane storage. Science 295, 469–472 (2002).

Mason, J. A. et al. Methane storage in flexible metal-organic frameworks with intrinsic thermal management. Nature 527, 357–361 (2015).

Chen, Z. et al. Balancing volumetric and gravimetric uptake in highly porous materials for clean energy. Science 368, 297–303 (2020).

Li, J. R., Kuppler, R. J. & Zhou, H. C. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1477–1504 (2009).

Bloch, E. D. et al. Hydrocarbon separations in a metal-organic framework with open iron(II) coordination sites. Science 335, 1606–1610 (2012).

Li, L. B. et al. Ethane/ethylene separation in a metal-organic framework with iron-peroxo sites. Science 362, 443–446 (2018).

Gu, C. et al. Design and control of gas diffusion process in a nanoporous soft crystal. Science 363, 387–391 (2019).

Liao, P.-Q., Huang, N.-Y., Zhang, W.-X., Zhang, J.-P. & Chen, X.-M. Controlling guest conformation for efficient purification of butadiene. Science 356, 1193–1196 (2017).

Zeng, H. et al. Orthogonal-array dynamic molecular sieving of propylene/propane mixtures. Nature 595, 542–548 (2021).

Lee, J. et al. Metal-organic framework materials as catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1450–1459 (2009).

Zhang, T. & Lin, W. Metal-organic frameworks for artificial photosynthesis and photocatalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 5982–5993 (2014).

Zhao, M. et al. Metal-organic frameworks as selectivity regulators for hydrogenation reactions. Nature 539, 76–80 (2016).

Shen, K. et al. Ordered macro-microporous metal-organic framework single crystals. Science 359, 206–210 (2018).

Trickett, C. A. et al. Identification of the strong Bronsted acid site in a metal-organic framework solid acid catalyst. Nat. Chem. 11, 170–176 (2019).

Stanley, P. M., Haimerl, J., Shustova, N. B., Fischer, R. A. & Warnan, J. Merging molecular catalysts and metal-organic frameworks for photocatalytic fuel production. Nat. Chem. 14, 1342–1356 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. A robust titanium isophthalate metal-organic framework for visible-light photocatalytic CO2 methanation. Chem 6, 3409–3427 (2020).

Tu, M. et al. Direct X-ray and electron-beam lithography of halogenated zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Nat. Mater. 20, 93–99 (2021).

Jiang, H.-L., Tatsu, Y., Lu, Z.-H. & Xu, Q. Non-, micro-, and mesoporous metal-organic framework isomers: Reversible transformation, fluorescence sensing, and large molecule separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5586–5587 (2010).

Hu, Z., Deibert, B. J. & Li, J. Luminescent metal-organic frameworks for chemical sensing and explosive detection. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 5815–5840 (2014).

Choueiri, R. M. et al. Surface patterning of nanoparticles with polymer patches. Nature 538, 79–83 (2016).

Gröschel, A. H. et al. Guided hierarchical co-assembly of soft patchy nanoparticles. Nature 503, 247–251 (2013).

Liu, X. et al. Complex silica composite nanomaterials templated with DNA origami. Nature 559, 593–598 (2018).

Flauraud, V. et al. Nanoscale topographical control of capillary assembly of nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 73–80 (2016).

Ausserwöger, H. et al. Non-specificity as the sticky problem in therapeutic antibody development. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 844–861 (2022).

Geng, H. et al. Graphene oxide restricts growth and recrystallization of ice crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 997–1001 (2017).

Wu, S. et al. Ion-specific ice recrystallization provides a facile approach for the fabrication of porous materials. Nat. Commun. 8, 15154 (2017).

Fan, Q. et al. Precise control over kinetics of molecular assembly: Production of particles with tunable sizes and crystalline forms. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 15141–15146 (2020).

Jayaramulu, K. et al. Graphene-based metal-organic framework hybrids for applications in catalysis, environmental, and energy technologies. Chem. Rev. 122, 17241–17338 (2022).

Pang, S. H., Han, C., Sholl, D. S., Jones, C. W. & Lively, R. P. Facet-specific stability of ZIF-8 in the presence of acid gases dissolved in aqueous solutions. Chem. Mater. 28, 6960–6967 (2016).

Han, C., Zhang, C., Tymińska, N., Schmidt, J. R. & Sholl, D. S. Insights into the stability of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks in humid acidic environments from first-principles calculations. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 4339–4348 (2018).

Zheng, Y., Zheng, S., Xue, H. & Pang, H. Metal-organic frameworks/graphene-based materials: preparations and applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1804950 (2018).

Gerrard, N., Gattinoni, C., McBride, F., Michaelides, A. & Hodgson, A. Strain relief during ice growth on a hexagonal template. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8599–8607 (2019).

Holz, M., Heil, S. R. & Sacco, A. Temperature-dependent self-diffusion coefficients of water and six selected molecular liquids for calibration in accurate 1H NMR PFG measurements. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2, 4740–4742 (2000).

Park, K. S. et al. Exceptional chemical and thermal stability of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 10186–10191 (2006).

Howarth, A. J. et al. Chemical, thermal and mechanical stabilities of metal-organic frameworks. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 1–15 (2016).

Kalmutzki, M. J., Diercks, C. S. & Yaghi, O. M. Metal-organic frameworks for water harvesting from air. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704304 (2018).

Zhang, C., Han, C., Sholl, D. S. & Schmidt, J. R. Computational characterization of defects in metal-organic frameworks: spontaneous and water-induced point defects in ZIF-8. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 459–464 (2016).

Xie, L. S., Skorupskii, G. & Dincă, M. Electrically conductive metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 120, 8536–8580 (2020).

Zhang, G. et al. Recent advances in the development of electronically and ionically conductive metal-organic frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 439, 213915 (2021).

Lin, J. B. et al. A scalable metal-organic framework as a durable physisorbent for carbon dioxide capture. Science 374, 1464–1469 (2021).

Hummers, W. S. & Offeman, R. E. Preparation of graphitic oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80, 1339–1339 (1958).

Pan, Y. et al. Tuning the crystal morphology and size of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 in aqueous solution by surfactants. CrystEngComm 13, 6937–6940 (2011).

Koop, T., Luo, B. P., Tsias, A. & Peter, T. Water activity as the determinant for homogeneous ice nucleation in aqueous solutions. Nature 406, 611–614 (2000).

Ruoff, R. Calling all chemists. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 10–11 (2008).

Bai, G. Y., Gao, D., Liu, Z., Zhou, X. & Wang, J. J. Probing the critical nucleus size for ice formation with graphene oxide nanosheets. Nature 576, 437–441 (2019).

Park, J. et al. A study of the correlation between the oxidation degree and thickness of graphene oxides. Carbon 189, 579–585 (2022).

Vila, M. et al. Cell uptake survey of pegylated nanographene oxide. Nanotechnology 23, 465103 (2012).

Sun, X., Keywanlu, M. & Tayebee, R. Experimental and molecular dynamics simulation study on the delivery of some common drugs by ZIF‐67, ZIF‐90, and ZIF‐8 zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 35, e6377 (2021).

Tan, J. C., Bennett, T. D. & Cheetham, A. K. Chemical structure, network topology, and porosity effects on the mechanical properties of Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 9938–9943 (2010).

Boyd, P. G., Moosavi, S. M., Witman, M. & Smit, B. Force-field prediction of materials properties in metal-organic frameworks. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 357–363 (2017).

Jorgensen, W. L., Maxwell, D. S. & TiradoRives, J. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225–11236 (1996).

Hockney, R. W. & Eastwood, J. W. Computer Simulation Using Particles (Taylor & Francis, 1988).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS-a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Fiorin, G., Klein, M. L. & Hénin, J. Using collective variables to drive molecular dynamics simulations. Mol. Phys. 111, 3345–3362 (2013).

Kaestner, J. Umbrella sampling. Wires Comput. Mol. Sci. 1, 932–942 (2011).

Hub, J. S., de Groot, B. L. & van der Spoel, D. g_wham-A free weighted histogram analysis implementation including robust error and autocorrelation estimates. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 6, 3713–3720 (2010).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1997).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

VandeVondele, J. & Hutter, J. Gaussian basis sets for accurate calculations on molecular systems in gas and condensed phases. J. Chem. Phys. 127, 114105 (2007).

Krack, M. Pseudopotentials for H to Kr optimized for gradient-corrected exchange-correlation functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 114, 145–152 (2005).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jonsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Kuehne, T. D. et al. CP2K: An electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package - Quickstep: Efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 194103 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants T2293760, T2293762 and 51925307 to J.W.; grant 22173011 to C.Z.; grant 22090062 to J.Li.); National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant 2021YFA1500700 to C.Z.); Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, CAS (grant ZDBS-LY-SLH031 to J.W.); U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231 within the Adaptive Interfacial Assemblies Towards Structuring Liquids program (KCTR16) to T.P.R.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. conceived the project. J.Liu, J.Li, L.L., C.Z., W.-H.F., T.P.R., and J.W. cosupervised the project. Y.L. designed the experiments and analyzed the data. Y.-G.F. and C.Z. conducted molecular dynamics simulations and DFT calculations. Y.C. performed humid gas breakthrough tests and analyzed all the breakthrough data. Y.L. and H.X. carried out the electron tomography with the help from B.G. Y.L. and J.M. performed the TEM images and analyzed the results. Y.L., Y.-G.F., Y.C., J.Li, L.L., C.Z., T.P.R., and J.W. cowrote the manuscript, and all authors have commented on and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, Y., Fang, YG., Chen, Y. et al. Sandwiching of MOF nanoparticles between graphene oxide nanosheets among ice grains. Nat Commun 16, 3397 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56949-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56949-w