Abstract

Unveiling the so far ambiguous mechanism of the significant dependence on the identity of alkali metal cation would prompt opportunities to solve the more than two orders of magnitude slowdown of hydrogen electrocatalytic kinetics in base relative to acid, which has hampered the effort to reduce the precious metal usage in fuel cells by using the hydroxide exchange membrane. Herein, we present atomic-scale evidences from ab-initio molecular dynamics simulation and in-situ surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy which show that it is the apparent discrepancies in the electric double-layer structures induced by differently sized cations that lead to largely different interfacial proton transfer barriers and therefore hydrogen electrocatalytic kinetics in base. Concretely, severe accumulation of larger cation in electric double-layer causes more discontinuous interfacial water distribution and H-bond network, thus rendering the proton transfer from bulk to interface more obstructed. Such notion is strikingly different from the previously envisioned impact of cation-intermediate interactions on the energetics of surface steps, providing a unique interfacial perspective for understanding the ubiquitous cation specificity in electrocatalysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen electrocatalysis, including hydrogen evolution and oxidation reactions (HER/HOR), is not only the fundamental process of water electrolysis and hydrogen fuel cells but also often serves as the model reaction to develop and verify the basic laws of electrocatalysis1,2,3,4,5. On platinum (Pt) that is one of the state-of-the-art catalysts for hydrogen electrocatalysis, it is widely known that the reaction kinetics of HER/HOR is several orders of magnitude slower in alkaline electrolyte than in acid environment, which has become the main bottleneck for the further development of relevant alkaline energy conversion and storage technologies6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Over the past decade, great strides of progress have been achieved in developing the material design principles or activity descriptors on the basis of tuning the composition and electronic structure of electrocatalysts to optimize the binding strength of reaction intermediates (e.g., the adsorbed hydrogen and hydroxyl), enabling an excellent understanding of the role of solid electrode material in affecting the alkaline HER/HOR kinetics13,14,15,16. By contrast, the exact roles of electrolyte properties in hydrogen electrocatalysis is much less understood currently17,18. In particular, a growing body of work has found that the alkaline HER/HOR kinetics on Pt is distinctly dependent on the identity of the alkali metal cation (AM+) in alkaline electrolyte, generally following the kinetic order of Li+ > Na+ > K+ > Cs+19,20,21. Such cation effect in reaction kinetics is not limited to HER/HOR but ubiquitous in plenty of critical electrocatalytic reactions, such as the oxygen evolution/reduction, CO2 reduction, alcohol oxidation and so on, thus having triggered a surge in research efforts recently22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Unfortunately, the physical origin of the cation-dependent electrocatalytic kinetics is yet elusive and contentious, even for the seemingly simple hydrogen electrocatalysis.

Hitherto, the understanding of the kinetic cation effect in alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis has primarily focused on the interactions of electrolyte cations with various reaction intermediates and/or electrode material and their effects on the energetics of surface reaction steps. For instance, Bandarenka et al. proposed that the AM+ close to the catalytic centers could weaken the binding strength of the adsorbed hydrogen (Had) intermediate19. However, several studies have shown that the acid HER/HOR activity over Pt was independent of the identity of AM+, implying that the cations should not affect the Had binding strength11,21. Therefore, more attention has been paid to the stabilization/destabilization interactions of AM+ on the adsorbed hydroxyl (OHad) intermediate and interfacial OH- species. Specifically, due to the different hydration energies of various AM+ cations, the interaction strength between electrolyte cations and OHad/OH- intermediates is enormously variable, and thus the identity of AM+ could notably control the kinetics of alkaline Volmer/Heyrovsky steps through regulating the dissociation/formation of reactive water21, the desorption/adsorption of OHad/OH-33,34, the transfer of OH- species in interfacial region35, or the number of surface OHad species that was envisioned to serve as the proton acceptors/donors36. In addition, Koper et al. ascribed the cation-specific alkaline hydrogen electrocatalytic kinetics to the interaction between the electrolyte cations and electrode surface and the resultant surface site blocking effect37,38. The weakly hydrated cations such as K+ interact more strongly with the electrode, thus pronouncedly accumulating near the surface to block the active site and inhibit the reaction kinetics.

On the other hand, the variation in interfacial environment with the identity of AM+ has been gradually realized to play a vital role in the kinetic cation effect in alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis39,40,41,42,43,44. Different from the very early studies by Frumkin45,46, which provided a phenomenological interpretation of the cation effects in electrochemistry from the perspective of the effect of the nature of cation on the kinetic overpotential at outer Helmholtz plane, Shao-Horn et al. recently attributed the cation-specific HER/HOR kinetics to the different reorganization energy of interfacial water, based on the fitting of electrochemical kinetic data with Marcus−Hush−Chidsey formalism39,47. Moreover, we have also demonstrated recently that under the alkaline hydrogen electrocatalytic conditions, the Na+ could crowd together in the electric double-layer (EDL) and then bring about the significant discontinuities of interfacial water molecules and H-bond network, eventually leaving the HER/HOR kinetics sluggish at high pH48. The subsequent study by Sun et al. further bolstered this insight49. However, the complete and clear atomistic pictures of the interfacial environments in alkaline electrolytes containing different AM+ cations and their quantitative correlation with the cation-specific kinetics are still lacking.

In this work, by integrating the ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulation with the in situ attenuated total reflection surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (ATR-SEIRAS), two techniques capable of gaining molecular-level information of the electrochemical interfaces, a comprehensive investigation involving multiple perspectives is conducted to uncover the exact origin of the kinetic cation effect in alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis over Pt. We have meticulously compared the EDL atomic structures at hydrogen electrocatalytic interfaces on Pt(111) electrode, the adsorption thermodynamics of key intermediates, and the free energy barriers of elementary processes in various AMOH (AM = Li+, Na+, and K+) electrolytes. It is found that the cation-specific HER/HOR kinetics cannot be interpreted from the perspective of the impact of AM+ identity on the energetics of surface reaction steps as traditionally considered, because the cation nature does not alter the hydrogen binding energy (HBE) and the trend of water dissociation free energy barrier (Li+ ≈ K+ > Na+) conflicts with the experimentally observed kinetic order of alkaline HER/HOR (Li+ > Na+ > K+); rather, it is a matter of proton transfer (PT) across the interfacial EDL. Specifically, the severe crowding of cation at a much negatively electrified interface renders the discontinuities of the water molecule distribution and H-bond network in EDL, which gradually intensify with the bare cation size increasing, thereby leading to greater inhibition of the PT from electrolyte bulk to interfacial reaction region and lowering of the hydrogen electrocatalytic kinetics, because the essence of hydrogen electrocatalysis is proved to be a PT process. The quantification of the PT barrier across the EDL, as well as the linear relationships between the theoretically statistical gap zone width and H-bond number and the experimentally measured exchange current density of alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis and proportion of H-bond-poor interfacial water, can provide compelling evidence for the notion that the apparent discrepancies in the EDL structures induced by differently sized cations and the resulting disparate interfacial PT barriers play a dominant role in the kinetic cation effect. This study not only sheds unique insights into understanding the ubiquitous cation effects in electrocatalysis but also stresses the importance of the structural and functional modulations of electrocatalytic interfaces for further improving the performance of electrochemical energy conversion and storage technologies.

Results and discussion

Cation-dependent EDL atomic structures at alkaline hydrogen electrocatalytic interfaces

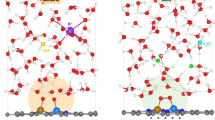

To mimic the Pt/AMOHaq (AM = Li+, Na+ and K+) interface under alkaline hydrogen electrocatalytic conditions, several AM+ cations were progressively inserted into the water layer to charge the Pt(111) electrode and construct the compact layer (Supplementary Data 1), with the omission of diffusion layer and co-ions; meanwhile, the adsorbed hydrogen species (Had) were also taken into account, which could also make a certain contribution to the electrode potential regulation (see Methods part and Supplementary Figs. 1–3 for details). Figure 1a–c shows the representative interfacial EDL atomic structures on the Pt(111) electrode in LiOH, NaOH, and KOH aqueous electrolytes under hydrogen evolution conditions, in which the introduction of four cations can drive the electrode potentials into the hydrogen evolution potential range. Due to the higher negative charge density on electrode surface under alkaline hydrogen evolution conditions, the AM+ cations significantly accumulate in the vicinity of the electrified interface with a layered distribution feature to construct the compact layer, accompanied by losing partial solvation shells, which can be seen from the AM-O radial distribution functions shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. The statistical concentration profiles of cations demonstrate that the closest ion planes (CIP) to the electrode surface for Li+, Na+ and K+ are situated in ~ 2.43 Å, ~2.85 Å and ~ 3.34 Å away from the electrode surface (Supplementary Fig. 5), respectively. Through different definitions and computation approaches29,50, the local cation concentrations around CIPs are estimated to be ~ 20–80 times higher than the electrolyte bulk concentration (1.0 mol/L) in the experiment, which conforms to the previous result of Bandarenka et al. based on the impedance spectroscopy measurements that the cation concentration at interfacial EDL appeared ∼ 80 times higher than the bulk value19,51, suggesting the validity of the simulated interface structures. More notably, the smaller cations are closer to the much negatively charged Pt electrode surface, which is due to the stronger electrostatic attraction interaction between them. This agrees well with a recent study by Tang et al.52 but contrasts with the traditional view, which believes that the cations with smaller bare size and larger charge density tends to be situated at a larger distance to the negatively charged electrode surface where they can maintain their hydration shell relatively intact30,53. Furthermore, such ion-size dependent CIP position can conform well the logic proposed by Havenith et al. and Salanne et al., which stated that the ions with smaller sizes prefer to approach the charged electrode surface more to compensate for their partial loss of hydration shell by utilizing the interaction inbetween54,55. However, it is noteworthy that the larger Na+ and K+ cations possess distinctly higher concentrations at the CIP compared to that of the smaller Li+ (Fig. 1a–c and Supplementary Fig. 5), which may be attributed to the lower hydratability of Na+ and K+ and the resultant weaker solvation volume repulsion effect in the lateral direction. Such AIMD-revealed discrepancy between the distribution characteristics of Li+, Na+, and K+ provides an unambiguous interfacial EDL picture at the atomic level for previous studies about the hydrogen electrocatalysis and CO2 reduction, in which the larger cations were often envisioned to be more concentrated at the interface and thereby significantly affected the reaction kinetics and selectivity28,37. The additional tests for Pt(111)/LiOHaq interfaces with different Li+ distribution structures (Supplementary Fig. 6) and the extended time-scale simulation of Pt(111)/KOHaq interface (Supplementary Fig. 7) can further validate the accuracy and reliability of the above results.

a–c Representative snapshots of the interfacial EDL structures at hydrogen evolution potentials for Pt(111)/LiOHaq, Pt(111)/NaOHaq and Pt(111)/KOHaq systems, respectively. The closest ion planes (CIP) to the electrode surface are labeled. d Concentration distribution profiles of water molecules along the surface normal direction. The black vertical dashed line represents the interfacial water layer closest to the electrode surface. The light gray horizontal dashed lines represent the bulk water concentration (0.056 mol cm−3). e Statistical distribution of the H-bond number along surface normal direction. The light green shaded areas represent the gap zones. Here the definition of H-bond is taken from previous work80,81. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Furthermore, the concentration distributions of water molecules along the surface normal direction at different Pt(111)/AMOHaq interfaces are analyzed and compared (Fig. 1d). The sharp water concentration peaks (marked by black vertical dashed line) at ~ 3.20 Å away from the electrode surface represent the interfacial water layer immediately adjacent to Pt(111) surface, in which the water molecules are in H-down configurations (Supplementary Fig. 8) and coordinate with the interfacial cations. Subsequently, all three interfaces display a gap zone (light green shading) in which the water concentration approaches to zero and beyond which the water concentration fluctuates around the bulk value (0.056 mol cm−3). Such gap zones of water can be attributed to the crowding of AM+ cations at the electrified interfaces and its manipulation for the water distribution through hydration interactions, as well as the ordered H-down orientation of interfacial water which can significantly reduce the ability of them to form H-bonds with others. More importantly, it can be seen that the width of the gap zone exhibits a salient dependence on the cation size, that is, increasing gradually with the cation size. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 9, the widths of gap zones are estimated to be 0.27 Å, 0.63 Å and 1.03 Å at Pt(111)/LiOHaq, Pt(111)/NaOHaq and Pt(111)/KOHaq interfaces, respectively, through integrating the water concentration distribution profiles. Predictably, the more severe depletion of water molecules and larger width of the gap zone induced by the crowding of larger cation in the EDL will give rise to the more terrible connectivity of the interfacial H-bond network. This can be unequivocally verified by the statistical distribution of the H-bond number along the surface normal direction (Fig. 1e), which demonstrates that the H-bond number in the gap zone (light green shading) is gradually diminished from Pt(111)/LiOHaq to Pt(111)/KOHaq interfaces. In addition, it is noteworthy that the AIMD-simulated Pt(111)/AMOHaq interfaces under alkaline HOR conditions also exhibit completely similar discrepancies of EDL atomic structure features (Supplementary Fig. 10) compared to that in the HER case. This suggests that the cation size dependence of interfacial water distribution and H-bond network connectivity is universal in the whole alkaline hydrogen electrocatalytic regime, because any HER/HOR potential in alkaline electrolyte is much lower than the potential of zero charge (PZC, ~ 1.1 V vs RHE) of Pt(111) electrode (Supplementary Fig. 11), thereby leading to the much negatively charged electrode surface and crowding of alkali metal cations in EDL. Further detailed investigations shown in Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13 indeed demonstrate that the AM+ shaped interfacial structures and their cation-dependence do not vary with a certain extent of change in the electrode potential. In addition, whether the explicit consideration of OH- anion in electrolyte would affect the above interfacial structure features has also been evaluated, and the results shown in Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15 clearly indicate the negligible effect. Consequently, it is conceivable that the gradually increasing discontinuity of the H-bond network in EDL with increasing the cation size will bring about the continuous lowering in reaction kinetics because the H-bond network at the interface provides the channels for proton transfer between the bulk solution and interfacial reaction region.

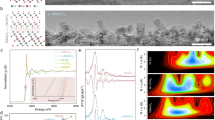

Unexpected water dissociation barrier trend at the cation-crowded interface

As already stated, numerous studies have attributed the cation-specific alkaline HER/HOR kinetics to the difference in the interaction strength of various cations with OHad/OH- species, which was envisioned to affect the energetics of the water dissociation/formation in Volmer/Heyrovsky steps or the transfer of OHad/OH- species between interface and bulk. To validate these opinions, we consider the Volmer step involving the cleavage of the H-OH bond of interfacial water in alkaline HER for simplicity and perform the slow-growth simulations to directly observe the detailed processes along water dissociation at various Pt(111)/AMOHaq interfaces and meanwhile obtain the free energy barriers (ΔG‡) of Volmer reactions. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 16, each interfacial water molecule closest to the electrode surface has been served as the dissociative reactant to form Had, and the collective variable (CV) is defined as the length of the O-H bond of the interface water molecule that points toward the electrode surface (Supplementary Fig. 17). The representative slow-growth simulations for alkaline Volmer steps at various Pt(111)/AMOHaq interfaces show that at all three interfaces, the water dissociation reaches the transition state (TS) as the O-H bond length increases to ~ 1.45 Å (Supplementary Figs. 18–20). As depicted in Fig. 2a, it is surprising that the ΔG‡ values of the Volmer reactions of reactive water molecules at different Pt(111)/AMOHaq interfaces are holistically in the sequence of \({\Delta {{\rm{G}}}}_{{{\rm{NaOH}}}}^{{{\ddagger}} }\) > \({\Delta {{\rm{G}}}}_{{{\rm{LiOH}}}}^{{{\ddagger}} }\) ≈ \({\Delta {{\rm{G}}}}_{{{\rm{KOH}}}}^{{{\ddagger}} }\). Such unexcepted tendency can be further confirmed by the vibrational density of states (VDOS) analyses of interfacial water molecules in Pt(111)/AMOHaq systems. Figure 2b clearly shows that the vibrational frequency of the computational O-H stretching band of interfacial water molecules in Pt(111)/NaOHaq system (~ 3278 cm−1) is much higher than that in Pt(111)/LiOHaq and Pt(111)/KOHaq systems (~ 3200 cm−1), indicating the higher O-H bond strength for the water molecules at Pt(111)/NaOHaq interface and thus corresponding to the higher water dissociation barrier. These above simulated results obviously contradict the traditional view in numerous previous literature which stated that the water dissociation kinetics should gradually increase with the hydration capacity of AM+ cation56,57, but can be well understood when considering the cation-specific EDL structures.

a The calculated free energy barrier ΔG‡ of the O-H bond cleavage for the interfacial water molecules closest to the electrode surface in various Pt(111)/AMOHaq systems. The constant potential correction has been performed (Supplementary Table 1). Error bars are obtained from the standard deviation of three independent slow-growth simulations. b The computational VDOS (gray jagged lines) of interfacial water molecules that are immediately next to the electrode surface. The green and orange curves are the Gaussian fittings of H-O-H bending (δHOH) and O-H stretching (υO-H) vibration spectra, respectively. c Statistical proportions of interfacial water molecules coordinated to different numbers of alkali cations. The insets are the corresponding schematic diagrams of the coordination structures of interfacial water molecules. d Average cation coordination number of interfacial water (\({{\mbox{CN}}}_{{{\mbox{H}}}_{2}{\mbox{O}}{-{\mbox{AM}}}^{+}}\)), and the alkali cation hydration energy (\({\Delta {\mbox{H}}}_{{{\mbox{AM}}}^{+}}\)) which was derived from a previous study by Strmcnik et al.32. The shadings only represent the figure background. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As mentioned above, the concentrations of K+ and Na+ at CIPs are fairly higher than that of Li+ under alkaline hydrogen electrocatalytic conditions. This implies that the water molecules next to the surface in Pt(111)/KOHaq and Pt(111)/NaOHaq systems may receive the coordination and polarization interactions from multiple surrounding AM+ cations, which is also expected to effectively facilitate the breakage of the O-H bond of the water molecule, although the polarization capacity of an individual K+/Na+ is lower. To support this envision, the statistical proportions of various interfacial water molecules with different cation coordination numbers (\({{{\rm{CN}}}}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}{-{{\rm{AM}}}}^{+}}\)) are extracted. As illustrated in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 21, the highly coordinated water (such as 2AM+-coordinated water and even 3AM+-coordinated water) gradually appears from Li+ to K+, which demonstrates that the interfacial water molecules can indeed be polarized by multiple larger and weakly hydrated cations simultaneously. Especially at Pt(111)/KOHaq interface, the 2AM+-coordinated water dominates, compared to the Pt(111)/LiOHaq and Pt(111)/NaOHaq systems in which the 1AM+-coordinated water is dominant, thus corresponding to a much higher average value of \({{{\rm{CN}}}}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}{-{{\rm{AM}}}}^{+}}\) (Fig. 2d). More importantly, when presenting the ΔG‡ alongside the corresponding \({{{\rm{CN}}}}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}{-{{\rm{AM}}}}^{+}}\) and statistical proportion for each interfacial water reactant (Supplementary Table 2), it is apparent that the relatively low ΔG‡ values for O-H bond cleavage are mainly derived from the interfacial water molecules with dominant statistical proportion and relatively high \({{{\rm{CN}}}}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}{-{{\rm{AM}}}}^{+}}\), that is, the 1AM+-coordinated water molecules at Pt(111)/LiOHaq and Pt(111)/NaOHaq interfaces while the 2AM+-coordinated water at Pt(111)/KOHaq interface. Based on this, one can realize that the calculated lower water dissociation barrier at Pt(111)/LiOHaq and Pt(111)/KOHaq interfaces can be attributed to the outstanding hydration/polarization capacity of individual Li+ and the multiple polarization effect of K+, respectively. Instead, at Pt(111)/NaOHaq interface, neither the hydration/polarization strength of Na+ nor the average \({{{\rm{CN}}}}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}{-{{\rm{AM}}}}^{+}}\) of the water molecule is notable, thereby leading to the higher water dissociation barrier. In other words, when the microenvironment of water molecules (described by the \({{{\rm{CN}}}}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}{-{{\rm{AM}}}}^{+}}\)) at Pt(111)/LiOHaq and Pt(111)/NaOHaq interfaces are not far apart, the ΔG‡ of O-H bond cleavage is mainly controlled by the strength of cation-water interaction, whereas at Pt(111)/KOHaq interface where the microenvironment of interfacial water is greatly distinct, the ΔG‡ no longer depends solely on the cation identity, emphasizing the substantial difference between interface chemistry and bulk chemistry. Notably, all these simulated results are inconsistent with the experimentally observed alkaline HER/HOR kinetics tendency (Li+ > Na+ > K+), suggesting that the kinetic cation effect of alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis cannot be simply attributed to the assumed influence of cation nature on the energetics of Volmer/Heyrovsky reactions. On the other hand, it is worth emphasizing that the high proportion of highly coordinated water molecules also implies the tight linkage and mutual entanglement between the individual (H2O)n ∙ AM+ clusters at interface (marked by the black dashed circles in Supplementary Fig. 21). This will obviously lead to a significant increase in the interfacial rigidity, thus offering a perspicuous atomistic picture and interpretation for the experimentally derived reorganization energy trend (K+ > Na+ > Li+) reported by Huang et al.39.

EDL origin of the kinetic cation effect in alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis

Beyond the TS of O-H bond breakage, the PT through the Grotthuss mechanism from the distant water molecule to the interfacial OH- product seems inclined to occur, as depicted in Fig. 3a, b and Supplementary Figs. 18–20, rather than the direct migration of OH- product itself from interface to bulk region as traditionally considered. This unequivocally indicates that the essence of hydrogen electrocatalysis is a PT process, mainly including two steps in series: the PT between the electrode surface and the adjacent interfacial species such as the aforementioned O-H bond breakage process, and the PT between the interfacial species and bulk region through the H-bond network in EDL. Therefore, it can be realized that the abundance and connectivity of the H-bond network in the EDL and the smoothness of PT it controls undoubtedly play decisive roles in the reaction kinetics. From this perspective, the experimentally observed dependence of alkaline HER/HOR kinetics on the identity of AM+, namely in the order of Li+ > Na+ > K+, can be well explained. Concretely, as illustrated in the simulated EDL structures (Fig. 1) and the corresponding schematic diagrams (Fig. 3c, d), the crowding of larger AM+ cations at the electrified interface can bring about the wider gap zone of interfacial water and then the more terrible connectivity of H-bond network in EDL, which would significantly impede the PT from bulk to interface and eventually renders more sluggish HER/HOR kinetics. Excitingly, Fig. 3e shows that both the theoretically statistical H-bond number within the gap zone and the experimentally measured exchange current density (j0) of alkaline HER/HOR on Pt exhibit a linear relationship with the width of the gap zone, providing certain support to the above proposal, that is, the cation effect in alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis should be a matter of the PT kinetics across the interfacial EDL. Combined with our previous study48, it is worth mentioning that the kinetic pH and cation effects in hydrogen electrocatalysis can be uniformly understood from this perspective, further highlighting the broad and key roles of interface structure and property in electrocatalysis.

a, b Representative atomic structures of the whole interface (upper panel) and close-up (lower panel) of the transition state (TS) and final state (FS’) in the Volmer reaction at Pt(111)/LiOHaq interface. c, d Schematic diagrams of the EDL structures at Pt(111)/LiOHaq and Pt(111)/KOHaq interfaces and the proton transfer from bulk to interface through the H-bond network. e Experimental exchange current density (j0) of alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis and theoretical H-bond number within gap zone plotted against the width of gap zone. The j0 values are from a recent study by Huang et al.39. The shadings only represent the figure background. f The calculated HBE values at various Pt(111)/AMOHaq interfaces. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Furthermore, the HBE at various Pt(111)/AMOHaq interfaces are calculated (Supplementary Fig. 22) to evaluate the impact of the identity of cation on the adsorption strength of Had intermediate, because this has also been considered as a possible contributor to the cation effect in previous studies19. Figure 3f shows that the HBE values at all three interfaces are almost identical, differing from each other within only 7 meV, indicating the negligible impact of the identity of cation on the Had binding strength and agreeing well with the recent spectroscopic and cyclic voltammogram measurements11,58,59. This definitely demonstrates that the kinetic cation effect in alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis cannot be ascribed to the difference in the interaction between cation and Had intermediate. In addition, the recently reported OHad factor does not appear to be associated with the cation effect over the Pt(111) electrode either, because both previous studies and our simulations (Supplementary Fig. 23) showed that there should be no OHad species on Pt(111) surface under alkaline HER/HOR conditions9,21,59. However, it is worth highlighting that, the interfacial perspective proposed in this work can be applied well even for the polycrystalline/stepped Pt electrodes on which there may exist OHad species under alkaline HER/HOR conditions16,36 because we have revealed that the surface OHad species could play a role in improving the H-bond network connectivity and PT in EDL and then the reaction kinetics48,60. Such universality of the cation-dependent proton transfer related to the interfacial EDL structures in understanding the similar cation effects on a wide range of electrode systems with and without OHad further proves its key role in determining the reaction kinetics.

Quantifying the PT kinetics across the interfacial EDL

To further unequivocally substantiate the above proposal regarding the interfacial origin of the cation effect in alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis, we have directly simulated the PT across the interfacial EDL through the Grotthuss mechanism and quantified its kinetic barrier through systematic AIMD simulations integrated with the enhanced sampling method. Figure 4a–c and Supplementary Figs. 24–26 show the simulated PT paths across the EDL at various Pt(111)/AMOHaq interfaces, including both the paths with and without an already connected H-bond network. The CV is defined as the square root of the summation of O-H distances connecting the PT path from bulk water molecule to interfacial water molecule, and the vertical transfer distances (d⊥) of almost all PT pathways are higher than 3.5 Å (Supplementary Fig. 27), indicating that the simulated PT does cross the interfacial EDL.

a–c Several PT paths across the EDL (labeled from #1 to #5) for the slow-growth simulations at various Pt(111)/AMOHaq interfaces. d Free energy profile (red solid line) along the collective variable (CV) in a representative slow-growth simulation of the PT at Pt(111)/LiOHaq interface and the corresponding close-up of the initial state (IS), PT transition state (TS), O-H bond cleavage transition state (TS’) and final state (FS). The blue data points in the lower panel represent the free energy values after constant potential correction. e Free energy barrier ΔG‡ of the PT across the interfacial EDL in various Pt(111)/AMOHaq systems. Error bars are obtained from the standard deviation of two independent slow-growth simulations. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Figure 4d and Supplementary Figs. 28–30 show the representative simulations of PT across the interfacial EDL and the corresponding close-up of local atomic structures of several key intermediate states. It is apparent that the whole PT simulations at all three Pt(111)/AMOHaq interfaces involve three sub-processes: (i) the proton transfer from bulk water molecule towards the interfacial water molecule with the formation of hydronium next to electrode surface (IS → TS), in which the transition state (TS) is determined when the length of newly-generated O-H bond in hydronium shorten to ~ 1.15 Å; (ii) the cleavage of O-H bond of interfacial hydronium to form Had (TS → TS’); (iii) the reorganization of interfacial water molecule orientation after the O-H bond breaking (TS’ → FS). Notably, as depicted in the lower panel of Fig. 4d, the proton transfer across the EDL from bulk water molecule towards interfacial water molecule dominantly contributes to the free energy barrier along the whole simulation, implying that the PT across the interfacial EDL indeed plays a decisive role in determining the alkaline hydrogen electrocatalytic kinetics. Furthermore, Fig. 4e clearly shows that the ΔG‡ value of PT across the interfacial EDL not only is higher than that of O-H bond cleavage of water (Fig. 2a) but also increases with the cation size in the order of Li+ < Na+ < K+, which provides compelling evidence to support the key proposal, that is, the origin of kinetic cation effect in alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis should be contributed to the distinct discrepancies in the EDL structures induced by differently sized cations and the resultant difficulty of PT across the EDL. Although the kinetic barrier values shown in Fig. 4e are calculated from merely one snapshot, more simulations of PT across the EDL for the entire AIMD trajectory at Pt(111)/KOHaq interface can clearly confirm the accuracy of the above results and the reliability of the conclusions (Supplementary Fig. 31).

In situ SEIRAS verification of the cation-dependent discontinuity of interfacial water in EDL

To experimentally verify the cation-dependent discontinuity of the H-bond network in the simulated EDL, the electrochemical in situ SEIRAS technology is employed to obtain the vibration responses of interfacial water molecules in different alkaline electrolytes during HER/HOR. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 32, the prepared Pt thin-film working electrode can exhibit typical cyclic voltammogram features of polycrystalline Pt surfaces, and the HER rate does decrease in the order LiOH > NaOH > KOH as reported in the current literature. Figure 5a–c shows the in situ SEIRAS spectra of interfacial water measured at potentials from 0.20 V to -0.05 V vs RHE in 0.1 M LiOH, NaOH, and KOH electrolytes, respectively. These spectra are given in the form of difference spectra, taking the spectrum recorded at the potential of 0.90 V as a reference, because 0.90 V is close to the PZC of Pt electrode (~ 1.0 V vs RHE) at pH = 13 and thus is the watershed of the spectra recorded in a wide potential range from 1.10 V to − 0.05 V (Supplementary Fig. 33). It is clear that the O-H stretching peaks in various electrolytes display a broad and symmetric shape, which is the typical feature in alkaline media and consistent with numerous previous studies11,39.

a–c In situ SEIRAS spectra recorded at potentials from 0.20 V to − 0.05 V for a Pt electrode in Ar-saturated solutions of 0.1 M LiOH, NaOH, and KOH, respectively. d Deconvolutions of the O-H stretching peaks at 0 V in various alkaline solutions. e Proportions of the HB-poor H2O derived from the SEIRAS. f Average proportion of HB-poor H2O and experimental j0 of alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis plotted against the simulated width of gap zone. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the proportions of HB-poor H2O at various potentials. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Furthermore, as depicted in Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 34, the O-H stretching peaks have been deconvoluted into three distinct components through Gaussian fitting, which are marked by pink, cyan, and gray shadings, respectively. To precisely determine the assignment of these experimental peaks, the theoretical VDOS of interfacial water molecules within three representative regions at different distances from the electrode surface are analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 35)48, that is, the first layer of water molecules immediately next to the electrode surface that not only coordinates with plentiful AM+ cations but also interacts with the much negatively charged Pt surface (denoted as AM.H2O(Pt)), the H-bond-poor interfacial water molecules within the gap zone that possess the dangling OH groups due to the AM+-induced disruption of H-bond network (denoted as HB-poor H2O), and the H-bond-rich interfacial water molecules that are above the gap zone and with relatively intact H-bond structure similar to that of bulk water (denoted as HB-rich H2O), respectively. It is distinct that at all Pt(111)/AMOHaq interfaces, the O-H stretching frequencies of AM.H2O(Pt), HB-poor H2O and HB-rich H2O exhibit a similar change trend, that is, first a blueshift and then a redshift, suggesting that the low-, high- and medium-wavenumber components in the experimental spectra are associated with AM.H2O(Pt), HB-poor H2O and HB-rich H2O, respectively. Such assignment differs from several previous studies39,61,62, especially those by Li et al.40,42,63, in which the component with the highest wavenumber was usually assigned to the cation-bonded first layer of water molecules according to the classical H-bonding rule given that they have the weakest H-bond interactions. However, it is worth noting that in addition to traditionally considering the effect of H-bond interaction strength on the O-H stretching frequency of water, the water molecules at electrochemical interfaces, especially those adjacent to the electrode surface, will also be severely polarized by the accumulated cations through coordination interaction as well as by the much negatively charged Pt surface, which is expected to greatly weaken the water O-H bonds and thus reduce the O-H stretching frequency. In this regard, a recent study by Song et al. has confirmed the polarization-induced weakening of the O-H bonds of water molecules near the Pt surface by both the cation-water interaction and the catalyst surface under hydrogen evolution conditions using the surface-specific in situ Raman spectroscopy and eventually assigned the subpeak with the lowest wavenumber of ~ 3000–3200 cm−1 to the interfacial water molecules near the Pt surface64, which agrees well with our assignment above. Moreover, the fairly low wavenumber (3200–3300 cm−1) of the O-H stretching mode of interfacial water next to the much negatively charged Au(111) electrode surface has also been reported by Cheng et al.65, further supporting the assignment of the lowest wavenumber component to the first layer of water molecules at the electrified interface. Notably, the notable consistency between the computational VDOS trends in all three electrolyte systems (Supplementary Fig. 35b–d) can also verify the rationality of the spectra signal assignment for water molecules at complex electrochemical interfaces. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 36, the proportions of HB-poor H2O derived from both SEIRAS and VDOS are the largest in KOH electrolyte followed by NaOH and LiOH, demonstrating that the magnitude of gap zone and the discontinuity of H-bond network in EDL are indeed severely dependent on the cation size and follow the order of KOH > NaOH > LiOH, which is completely consistent with the above AIMD simulation results. More importantly, Fig. 5f shows that the average proportions of HB-poor H2O obtained from electrochemical in situ spectroscopy as well as the experimental j0 values exhibit a distinct linear relationship with the simulated width of the gap zone, unequivocally substantiating that it is the cation-dependent H-bond network discontinuity and PT smoothness in interfacial EDL that play a decisive role in the kinetic cation effect in alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis.

In summary, we have presented a comprehensive study from multiple perspectives, with a view to seeking out the exact origin of the kinetic cation effect in alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis over Pt at the atomic level, through integrating the AIMD simulation and in situ SEIRAS technology. The systematic AIMD simulations for various Pt(111)/AMOHaq interfaces containing Li+, Na+, and K+ under alkaline HER/HOR conditions distinctly demonstrate that the interfacial EDL structures and PT barrier are strongly dependent on the identities of AM+ cations, which provides an explicit interpretation for the cation-specific alkaline HER/HOR kinetics observed experimentally. Concretely, the accumulation of larger cations in EDL is inclined to bring about poorer connectivity of interfacial water distribution and H-bond network, which severely hinders the PT from bulk solution to interfacial reaction region across the EDL and eventually renders sluggish alkaline HER/HOR kinetics, because the essence of hydrogen electrocatalysis is the PT process. In contrast, it is found that the cation effect of alkaline HER/HOR over Pt cannot be explained from the perspective of the impact of AM+ nature on the energetics of surface reaction steps. The findings in this study shape a unique and significant interfacial mechanism on the molecular scale for understanding the root of the huge impact of the identity of alkali metal cation on the kinetics of alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis and even other proton-coupled electron transfer reactions, which hopefully opens up potential avenues for tuning the electrocatalytic performances through the structural and functional modulation of interfaces.

Methods

Computational models and details

To mimic the Pt/AMOHaq (alkali metal cation, AM+ = Li+, Na+, K+) interfaces, we placed 60 water molecules above a Pt(111) slab, which is four-layer 4×4 orthogonal and has a surface area of 1.10 nm2; then, we inserted several AM+ cations at ~ 3-4 Å away from the electrode surface (Supplementary Fig. 1). Given the relatively high AMOH electrolyte concentrations (0.1 M or 1.0 M) in actual experiments and the much negatively charged state of Pt electrode surface under hydrogen electrocatalytic conditions, the Gouy-Chapman diffusion layer is properly omitted in the model. In addition, the co-ions are also not considered, because there should be almost no co-ions around the Helmholtz plane, and we have proved that the co-ions in the bulk electrolyte did not affect the interfacial structure and reaction process (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15). The electrode potential vs the reversible hydrogen electrode (URHE) of each Pt(111)/AMOHaq system is driven to the potential range of hydrogen electrocatalysis through varying the number of inserted AM+ cation, and calculated according to the equation URHE = USHE + 0.059×pH = (Φ−ΦSHE)/e + 0.059×pH, in which Φ is the work function of Pt(111)/AMOHaq interface calculated as the energy difference between the vacuum level (Evac) and Fermi level (EF)66,67, ΦSHE is the work function of standard hydrogen electrode (SHE, 4.44 V)68,69, and e is the electron charge. In the calculation of Φ, the Evac is extracted from the planar-averaged electrostatic potential profile, corresponding to the value when the planar-averaged electron density of the interface decays to 10−5 e- Å−317,66. For the HER interfaces, four cations needed to be introduced, and the URHE values of Li+, Na+, and K+ systems were calculated as approximately − 0.63 V, − 0.32 V and − 0.50 V when pH = 14 with standard deviations of 0.35 V, 0.34 V, and 0.36 V, respectively; for the HOR interfaces, three cations were required and the URHE were 0.24 V, 0.17 V and 0.33 V with standard deviations of 0.21 V, 0.35 V, and 0.40 V, respectively. Certainly, several constant potential schemes and codes have been developed recently, which can be integrated in the near future for more accurate potential control and electrochemical simulations70,71,72,73. In addition, to model the surface adsorption state of the Pt electrode under reaction conditions, we have also considered the hydrogen adsorbates (Had). According to previous experimental results74,75, the Had coverage of 0.63 monolayers (ML, defined per surface Pt atom) and 0.25 ML were used for HER and HOR cases, respectively.

The plane-wave pseudopotential code Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) was used to carry out the AIMD simulations76,77. The exchange-correlation energies were evaluated by the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional under the framework of generalized gradient approximation (GGA)78. We set the cutoff energy as 400 eV for the wave function expansion and used the First order Methfessel-Paxton scheme with a smearing width of 0.2 eV. The semi-empirical D3 dispersion correction scheme of Grimme was employed to consider the van der Waals interaction79. Spin polarization was not included in all simulations. A time step of 1.0 fs, which has been proved to be exactly suitable for the simulations of aqueous solution (Supplementary Fig. 37), and the individual gamma point of the Brillouin zone without symmetry were used. The temperature was maintained at 298 K by the Nose-Hoover thermostat within the canonical ensemble (NVT). AIMD simulations were run for 15–25 ps to ensure sufficient equilibration, with the final 10 ps used for statistical analysis. The definition of H-bond was in line with the previous work80,81, namely the inter-oxygen distance between two water molecules is less than 3.5 Å, and simultaneously the angle between the O-O axis and one of O-H bonds is less than 30°.

To simulate the dissociation process of an interfacial water molecule (H2O + e- → *H + OH-), the slow-growth approach was employed82, in which the collective variable (CV) was easily defined as the O-H bond length (dO-H) of the interface water molecule and an increment of 0.0008 Å/fs was set. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 38, the rationality of such a simple CV has also been proved by comparing with another commonly used CV, namely the difference between O-H and H-Pt distances (dO-H – dH-Pt). In addition, the evaluation tests have also been performed to verify the rationality of 0.0008 Å/fs increment (Supplementary Fig. 39). For each reaction process, three independent slow-growth simulations have been performed for error analysis. Due to that the slow-growth simulations were carried out under the constant-charge condition, the correction procedure proposed by Chan and Nørskov has been used to approach the constant-potential scenario83,84.

Electrochemical measurements

A PARSTAT electrochemical workstation (VersaSTAT 3 F) and a three-electrode configuration were utilized for all electrochemical and spectroscopic measurements at room temperature. The mercury oxide (Hg/HgO) electrode and Pt foil were used as the reference electrode and counter electrode, respectively. The Pt thin film working electrode was prepared by a typical two-step deposition method, involving the chemical deposition of an Au thin film on a hemispheric Si prism (diameter of 2 cm) followed by the galvanostatic electrodeposition of a Pt thin film on the Au substrate48,85. The detailed procedures are shown in Supplementary Note 1 in the Supplementary Information. The calibration of the Hg/HgO electrode to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) was performed in the high purity H2-saturated 0.1 M AMOH electrolytes, with Pt wire and carbon rod as the working and counter electrodes; the linear sweep voltammetry was conducted at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1, and the potential corresponding to the zero-current point was determined as the thermodynamic potential for the hydrogen electrode reactions, which were − 0.921 V in LiOH and − 0.926 V in NaOH and KOH. Accordingly, all potentials were converted to the RHE scale based on the equation ERHE = EHg/HgO + 0.921 (or 0.926) V. Before electrochemical and spectroscopic tests, the prepared Pt thin film working electrode was firstly cycled in Ar-saturated 0.1 M AMOH electrolyte (pH = 13 ± 0.1) between 0.02 V and 1.2 V at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1 for two cycles to get a clean surface; then, the cyclic voltammetry curve was recorded from 0 V to 1.2 V at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1, and the HER activity test was also conducted at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1, without iR-correction. The electrolytes are freshly prepared prior to the electrochemical test.

In situ SEIRAS experiments

The BRUKER INVENIO-R FTIR spectrometer, which is equipped with a mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detector cooled with liquid nitrogen, was used to perform the spectroscopic measurements. To obtain the SEIRAS spectra, we first kept the Pt thin film electrode at 1.2 V for 10 s. Subsequently, the electrode potential was swept linearly from 1.2 V to − 0.05 V at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1, during which the spectra were recorded using the rapid-scan mode of OPUS software. Unpolarized infrared radiation from an Elema source was focused on the interface at a 60° incident angle, and the reflected radiation was detected. When stepping the working electrode potential, the real-time spectra were collected, with a resolution of 8 cm−1, and each spectrum derived from 44 scans. The same Pt surface was used for measurements in different 0.1 M AMOH solutions to ensure a similar surface enhancement effect. The 0.9 V vs RHE was taken as the reference.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files or from the corresponding authors upon request. All raw data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Seh, Z. W. et al. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: Insights into materials design. Science 355, eaad4998 (2017).

Stamenkovic, V. R., Strmcnik, D., Lopes, P. P. & Markovic, N. M. Energy and fuels from electrochemical interfaces. Nat. Mater. 16, 57–69 (2017).

Erdey-Gruz, T. & Volmer, M. The theory of hydrogen overvoltage. Z. Phys. Chem. 150, 203 (1930).

Trasatti, S. Work function, electronegativity, and electrochemical behaviour of metals: III. Electrolytic hydrogen evolution in acid solutions. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial ElectroChem. 39, 163–184 (1972).

Huang, J., Li, P. & Chen, S. L. Quantitative understanding of the sluggish kinetics of hydrogen reactions in alkaline media based on a microscopic Hamiltonian model for the Volmer step. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 17325–17334 (2019).

Sheng, W., Gasteiger, H. A. & Shao-Horn, Y. Hydrogen oxidation and evolution reaction kinetics on platinum: acid vs alkaline electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, B1529–B1536 (2010).

Durst, J. et al. New insights into the electrochemical hydrogen oxidation and evolution reaction mechanism. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 2255–2260 (2014).

Sheng, W. et al. Correlating hydrogen oxidation and evolution activity on platinum at different pH with measured hydrogen binding energy. Nat. Commun. 6, 5848 (2015).

Ledezma-Yanez, I. et al. Interfacial water reorganization as a pH-dependent descriptor of the hydrogen evolution rate on platinum electrodes. Nat. Energy 2, 17031 (2017).

Cheng, T., Wang, L., Merinov, B. V. & Goddard, W. A. III Explanation of dramatic pH-dependence of hydrogen binding on noble metal electrode: Greatly weakened water adsorption at high pH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7787–7790 (2018).

Zhu, S., Qin, X., Yao, Y. & Shao, M. pH-dependent hydrogen and water binding energies on platinum surfaces as directly probed through surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 8748–8754 (2020).

Lamoureux, P. S., Singh, A. R. & Chan, K. pH effects on hydrogen evolution and oxidation over Pt(111): insights from first-principles. ACS Catal. 9, 6194–6201 (2019).

Strmcnik, D. et al. Improving the hydrogen oxidation reaction rate by promotion of hydroxyl adsorption. Nat. Chem. 5, 300–306 (2013).

Zheng, Y., Jiao, Y., Jaroniec, M. & Qiao, S. Z. Advancing the electrochemistry of the hydrogen-evolution reaction through combining experiment and theory. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 52–65 (2015).

Strmcnik, D., Lopes, P. P., Genorio, B., Stamenkovic, V. R. & Markovic, N. M. Design principles for hydrogen evolution reaction catalyst materials. Nano Energy 29, 29–36 (2016).

McCrum, I. T. & Koper, M. T. The role of adsorbed hydroxide in hydrogen evolution reaction kinetics on modified platinum. Nat. Energy 5, 891–899 (2020).

Li, P., Jiao, Y., Huang, J. & Chen, S. L. Electric double layer effects in electrocatalysis: Insights from ab initio simulation and hierarchical continuum modeling. JACS Au 3, 2640–2659 (2023).

Sebastián-Pascual, P., Shao-Horn, Y. & Escudero-Escribano, M. Toward understanding the role of the electric double layer structure and electrolyte effects on well-defined interfaces for electrocatalysis. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 32, 100918 (2022).

Xue, S. et al. Influence of alkali metal cations on the hydrogen evolution reaction activity of Pt, Ir, Au, and Ag electrodes in alkaline electrolytes. ChemElectroChem 5, 2326–2329 (2018).

Ringe, S. Cation effects on electrocatalytic reduction processes at the example of the hydrogen evolution reaction. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 39, 101268 (2023).

Bender, J. T. et al. Understanding cation effects on the hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 657–665 (2023).

Kumeda, T., Laverdure, L., Honkala, K. & Melander, M. M. Cations determine the mechanism and selectivity of alkaline oxygen reduction reaction on Pt(111). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202312841 (2023).

Huang, J., Li, M., Eslamibidgoli, M. J. & Eikerling, M. Cation overcrowding effect on the oxygen evolution reaction. JACS Au 1, 1752–1765 (2021).

Rao, R. R. et al. pH- and cation-dependent water oxidation on rutile RuO2(110). J. Phys. Chem. C 125, 8195–8207 (2021).

Malkani, A. S. et al. Understanding the electric and nonelectric field components of the cation effect on the electrochemical CO reduction reaction. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd2569 (2020).

Ye, C., Dattila, F., Chen, X., López, N. & Koper, M. T. Influence of cations on HCOOH and CO formation during CO2 reduction on a PdMLPt(111) electrode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 19601–19610 (2023).

Qin, X. P., Hansen, H. A., Honkala, K. & Melander, M. M. Cation-induced changes in the inner- and outer-sphere mechanisms of electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. Nat. Commun. 14, 7607 (2023).

Resasco, J. et al. Promoter effects of alkali metal cations on the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 11277–11287 (2017).

Le, J. B., Chen, A., Kuang, Y. & Cheng, J. Molecular understanding of cation effects on double layer and its significance to CO-CO dimerization. Natl. Sci. Rev. 10, nwad105 (2023).

Ringe, S. et al. Understanding cation effects in electrochemical CO2 reduction. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 3001–3014 (2019).

Malkani, A. S., Anibal, J. & Xu, B. Cation effect on interfacial CO2 concentration in the electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction. ACS Catal. 10, 14871–14876 (2020).

Strmcnik, D. et al. The role of non-covalent interactions in electrocatalytic fuel-cell reactions on platinum. Nat. Chem. 1, 466–472 (2009).

Liu, E. et al. Unifying the hydrogen evolution and oxidation reactions kinetics in base by identifying the catalytic roles of hydroxyl-water-cation adducts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 3232–3239 (2019).

Jiao, L., Liu, E., Mukerjee, S. & Jia, Q. In situ identification of non-specific adsorption of alkali metal cations on Pt surfaces and their catalytic roles in alkaline solutions. ACS Catal. 10, 11099–11109 (2020).

Jiang, Y. et al. Inside solid-liquid interfaces: understanding the influence of the electrical double layer on alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 293, 120220 (2021).

Shah, A. H. et al. The role of alkali metal cations and platinum-surface hydroxyl in the alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Catal. 5, 923–933 (2022).

Monteiro, M. C., Goyal, A., Moerland, P. & Koper, M. T. Understanding cation trends for hydrogen evolution on platinum and gold electrodes in alkaline media. ACS Catal. 11, 14328–14335 (2021).

Goyal, A. & Koper, M. T. The interrelated effect of cations and electrolyte pH on the hydrogen evolution reaction on gold electrodes in alkaline media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 13452–13462 (2021).

Huang, B. et al. Cation- and pH-dependent hydrogen evolution and oxidation reaction kinetics. JACS Au 1, 1674–1687 (2021).

You, X. et al. Exploring the cation regulation mechanism for interfacial water involved in the hydrogen evolution reaction by in situ Raman spectroscopy. Nano Micro Lett. 16, 53 (2024).

Khani, H., Puente Santiago, A. R. & He, T. An interfacial view of cation effects on electrocatalysis systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202306103 (2023).

Wang, Y. H. et al. In situ Raman spectroscopy reveals the structure and dissociation of interfacial water. Nature 600, 81–85 (2021).

Waegele, M. M., Gunathunge, C. M., Li, J. & Li, X. How cations affect the electric double layer and the rates and selectivity of electrocatalytic processes. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 160902 (2019).

Rebollar, L. et al. Beyond adsorption” descriptors in hydrogen electrocatalysis. ACS Catal. 10, 14747–14762 (2020).

Frumkin, A. N. Wasserstoffuberspannung und Struktur der Doppelschicht. Z. Phys. Chem. 164, 121–133 (1993).

Frumkin, A. N. Influence of cation adsorption on the kinetics of electrode processes. Trans. Faraday Soc. 55, 156–167 (1959).

Huang, B. et al. Cation-dependent interfacial structures and kinetics for outer-sphere electron-transfer reactions. J. Phys. Chem. C 125, 4397–4411 (2021).

Li, P. et al. Hydrogen bond network connectivity in the electric double layer dominates the kinetic pH effect in hydrogen electrocatalysis on Pt. Nat. Catal. 5, 900–911 (2022).

Li, X. Y. et al. Mechanism of cations suppressing proton diffusion kinetics for electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218669 (2023).

Zhang, C., Hutter, J. & Sprik, M. Coupling of surface chemistry and electric double layer at TiO2 electrochemical interfaces. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 3871–3876 (2019).

Garlyyev, B., Xue, S., Watzele, S., Scieszka, D. & Bandarenka, A. S. Influence of the nature of the alkali metal cations on the electrical double-layer capacitance of model Pt(111) and Au(111) electrodes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 1927–1930 (2018).

Tang, B. et al. Tuning hydrogen bond network connectivity in the electric double layer with cations. Chem. Sci. 15, 7111–7120 (2024).

Pan, B., Wang, Y. & Li, Y. Understanding and leveraging the effect of cations in the electrical double layer for electrochemical CO2 reduction. Chem Catal. 2, 1267–1276 (2022).

Alfarano, S. R. et al. Stripping away ion hydration shells in electrical double-layer formation: Water networks matter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2108568118 (2021).

Serva, A., Scalfi, L., Rotenberg, B. & Salanne, M. Effect of the metallicity on the capacitance of gold–aqueous sodium chloride interfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 044703 (2021).

Danilovic, N. et al. The effect of noncovalent interactions on the HOR, ORR, and HER on Ru, Ir, and Ru0.50Ir0.50 metal surfaces in alkaline environments. Electrocatalysis 3, 221–229 (2012).

Subbaraman, R. et al. Enhancing hydrogen evolution activity in water splitting by tailoring Li+-Ni(OH)2-Pt interfaces. Science 334, 1256–1260 (2011).

Intikhab, S., Snyder, J. D. & Tang, M. H. Adsorbed hydroxide does not participate in the Volmer step of alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis. ACS Catal. 7, 8314–8319 (2017).

Stoffelsma, C. et al. Promotion of the oxidation of carbon monoxide at stepped platinum single-crystal electrodes in alkaline media by lithium and beryllium cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 16127–16133 (2010).

Su, L. et al. Electric-double-layer origin of the kinetic pH effect of hydrogen electrocatalysis revealed by a universal hydroxide adsorption-dependent inflection-point behavior. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 12051–12058 (2023).

Shen, L. F. et al. Interfacial structure of water as a new descriptor of the hydrogen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22397–22402 (2020).

Zhao, K. et al. Enhancing hydrogen oxidation and evolution kinetics by tuning the interfacial hydrogen-bonding environment on functionalized platinum surfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202207197 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Revealing the role of interfacial water and key intermediates at ruthenium surfaces in the alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 14, 5289 (2023).

Cheong, D. S. et al. Double activation of water splitting by strong cation–water interaction. J. Phys. Chem. C 127, 20718–20726 (2023).

Li, C. Y. et al. In situ probing electrified interfacial water structures at atomically flat surfaces. Nat. Mater. 18, 697–701 (2019).

Li, P., Liu, Y. & Chen, S. Microscopic EDL structures and charge-potential relation on stepped platinum surface: insights from the ab initio molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 104701 (2022).

Li, P. et al. Revealing the role of double-layer microenvironments in pH-dependent oxygen reduction activity over metal-nitrogen-carbon catalysts. Nat. Commun. 14, 6936 (2023).

Trasatti, S. The absolute electrode potential: an explanatory note (recommendations 1986). Pure Appl. Chem. 58, 955–966 (1986).

Le, J., Iannuzzi, M., Cuesta, A. & Cheng, J. Determining potentials of zero charge of metal electrodes versus the standard hydrogen electrode from density-functional-theory-based molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 016801 (2017).

Zhao, X. & Liu, Y. Origin of selective production of hydrogen peroxide by electrochemical oxygen reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 9423–9428 (2021).

Bai, X. et al. Dynamic stability of copper single-atom catalysts under working conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 17140–17148 (2022).

Yu, S., Levell, Z., Jiang, Z., Zhao, X. & Liu, Y. What is the rate-limiting step of oxygen reduction reaction on Fe-N-C catalysts? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 25352–25356 (2023).

Xia, Z. & Xiao, H. Grand canonical ensemble modeling of electrochemical interfaces made simple. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 5168–5175 (2023).

Marković, N. M. & Ross, P. N. Jr Surface science studies of model fuel cell electrocatalysts. Surf. Sci. Rep. 45, 117–229 (2002).

Marković, N. M., Gasteiger, H. A. & Ross, P. N. Oxygen reduction on platinum low-index single-crystal surfaces in alkaline solution: rotating ring disk Pt(hkl) studies. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 6715–6721 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B 46, 6671–6687 (1992).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Luzar, A. & Chandler, D. Hydrogen-bond kinetics in liquid water. Nature 379, 55–57 (1996).

Luzar, A. & Chandler, D. Effect of environment on hydrogen bond dynamics in liquid water. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 928–931 (1996).

Oberhofer, H., Dellago, C. & Geissler, P. L. Biased sampling of nonequilibrium trajectories: can fast switching simulations outperform conventional free energy calculation methods? J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 6902–6915 (2005).

Chan, K. & Nørskov, J. K. Electrochemical barriers made simple. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 2663–2668 (2015).

Chan, K. & Nørskov, J. K. Potential dependence of electrochemical barriers from ab initio calculations. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 1686–1690 (2016).

Li, Q. X., Huo, S. J., Ma, M., Cai, W. B. & Osawa, M. Ubiquitous strategy for probing ATR surface-enhanced infrared absorption at platinum group metal-electrolyte interfaces. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 7900–7906 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2023YFA1509004), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22332004, 22202156, 22472122, 22272122 and 21832004) and the Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 2024AFB571). The authors also acknowledge the supports of the Wuhan Supercomputing Center, the Supercomputing Center of Wuhan University and the Large-Scale Instruments and Equipment Sharing Foundation of Wuhan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C. supervised the project. P.L. and S.C. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. P.L. performed the AIMD simulations. Y.-L.J., P.L., and Y.M. performed the electrochemical and spectroscopic measurements. Y.-Z.J. participated in part of the analysis of the AIMD simulations. P.L. and S.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, P., Jiang, YL., Men, Y. et al. Kinetic cation effect in alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis and double layer proton transfer. Nat Commun 16, 1844 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56966-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56966-9

This article is cited by

-

Synergistic cation-facet effects boost alkaline hydrogen evolution kinetics on stepped Pt surfaces

Communications Chemistry (2026)

-

Dynamic water network reconfiguration via oxyphilic V dopants enables industrial-current-density alkaline hydrogen evolution

Science China Chemistry (2026)

-

An optimized two-step electrodeposition procedure for producing 90Y from 90Sr

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2025)