Abstract

Micro and nanoparticles made from polymers, metals, ceramics, and lipids are crucial for biomedical devices, energy storage, and electronics. Traditional fabrication methods like grinding, milling, and emulsification result in monolithic shapes and heterogeneous sizes. To improve shape control, techniques such as photolithography, inkjet printing (IJP), and molding are employed. Water-soluble molds are particularly promising for materials with solvent incompatibility, thermolability, and poor mechanical properties. Among them, lipids are interesting for their use in biomedical applications, however, current fabrication methods limit lipid microparticles to monolithic spherical shapes. This study presents calcium-based water-soluble 3D micro molds fabricated using two-photon polymerization (TPP) for complex-shaped lipid microparticles. TPP-fabricated organogels are converted to hydrogels, loaded with calcium nitrate, and calcined into Ca-based materials. Lipids are infiltrated into PVA-coated Ca-based molds via IJP, and selective mold leaching in water creates lipid microparticles with 2 µm resolution. The lipid microparticles can encapsulate and release lipophilic and hydrophilic drugs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Micro and nanoparticles are essential components in various applications, including biomedical devices1,2, energy storage3,4, and electronic systems5. These particles have been fabricated from diverse materials, mainly polymers, metals, ceramics, and lipids. Micro and nanoparticles are mostly fabricated using conventional processes such as emulsification6, precipitation7, milling8, and nucleation growth9. However, these have limitations in size precision since they rely mostly on physical breaking and self-assembly, which results in polydisperse particles. Furthermore, they are not suitable for producing complex non-spherical shapes due to the high mechanical forces applied during the process, as well as surface tension in emulsification and crystallographic directionality in nucleation growth methods. Therefore alternative approaches have been employed to overcome these limitations, such as photolithography10, inkjet printing (IJP)11, molding1, soft lithography12, and microfluidics13. These technologies allow the precise control of size and shape by light exposure path control (photolithography), spatial material deposition control (IJP), and injection and stamping in predefined shapes (molding, soft lithography). However, materials must be compatible with these methods to fabricate complex-shaped micro and nanoparticles with high resolution, such as photopolymerizable resin for photolithography or moderate viscosity for IJP, thus limiting the variability of the materials.

Particles made of lipids find applications in various fields, including pharmaceutics14,15, cosmetics16, and food packaging17. Their application as drug delivery devices has opened up new possibilities for advanced drug delivery systems. Lipids can dissolve and encapsulate active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) that exhibit poor water solubility18 and can encapsulate and stabilize hydrolysis-sensitive APIs until the onset of release, such as mRNA lipid nanoparticles14. Furthermore, lipids can be used for sustained drug release over a prolonged time due to their inherent poor water permeability except phospholipids19. Most micro and nano lipid particles are spherical because they are fabricated through emulsification-evaporation, and microfluidics, by exploiting the hydrophobicity and amphiphilicity of the lipids15. However spherical lipid components have low interaction with biological barriers such as mucosal tissue and with cells20,21, and are limited in their release control22. Manufacturing lipid particles with complex shapes can provide better drug release control, but can also be used to provide additional functions such as external manipulation or interaction with biological barriers for advanced drug delivery.

Non-spherical lipid structures with millimeter resolution have been fabricated by IJP23,24, pneumatic extrusion methods25,26, and conventional molding27 for drug delivery implants and self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS) tablets. However, their dimension is on the millimeter scale and their designs are relatively simple 2D or 2.5D shapes such as cubes and cylinders. The main obstacles to the microfabrication of more complex-shaped lipid particles are the poor mechanical properties of lipids, their low melting temperature, and the compatibility of lipids with organic solvents, which makes it virtually impossible to produce such components by conventional manufacturing techniques.

3D molds with the desired negative geometry that can be infiltrated with materials of interest and that are soluble for selective removal afterward, enable the fabrication of complex shapes without altering the properties of the molded materials. Additive manufacturing such as pneumatic extrusion28,29, stereolithography (SLA)30,31, or two-photon polymerization (TPP)32 have been used to fabricate soluble molds. However, these methods typically involve mold dissolution via aprotic and non-polar organic solvents or the thermal degradation of the mold above 100 °C which is not compatible with lipids. Therefore, a water-soluble mold compatible with lipids is required for the fabrication of complex-shaped lipid particles. Kleger et al. developed a 3D water-soluble NaCl mold shaped by pneumatic extrusion33 and SLA followed by calcination34, but the resolution of the mold was limited to a hundred micrometers due to the manufacturing technologies and the use of NaCl particles with a diameter of 2 µm in the printing resin. In addition, the infiltration of materials into the mold using a syringe is not compatible with micro-sized molds. Water-soluble polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) molds with millimeter resolution have been fabricated by fused deposition modeling (FDM)35. Aabith et al. further enhanced the resolution of PVA mold down to tens of microns by direct ink-writing technology. Although the resolution of the mold goes down to microns, the complexity of the design is limited to simple 2.5 dimensions36.

TPP enables the fabrication of structures with complex geometries and resolutions down to a single micron37. Consequently, TPP has been utilized for printing soft materials38, ceramic composites39, and metals40 by incorporating micro or nanoparticles or ions into the photoresist. However, implementing active substances before photopolymerization requires extra effort to optimize the photoresist and printing conditions, such as uniform particle distribution and photoresist composition according to materials. To address these challenges, a method that infuses active substances into a photopolymerized organogel follows by calcination, enabling the printing of various materials has been developed41. However, this method was demonstrated using SLA, which is limited in resolution compared to TPP and results in different polymerization densities.

In this work, we developed calcium-based water-soluble 3D micro molds using TPP and used them as templates for the fabrication of complex-shaped lipid microparticles. The fabrication of the 3D soluble micro molds was achieved by TPP of a polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA)/dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) organogel, followed by solvent exchange to transform the organogel into a hydrogel loaded with a calcium nitrate solution, and then calcination to remove the polymeric components, resulting in water-soluble Ca-based materials. TPP allows the fabrication of complex shapes with a resolution of 1 µm. However, the polymer network fabricated with a photosensitive medium with a high concentration of photoinitiator by TPP is dense, making it challenging to infuse a sufficient amount of Ca precursor, which is necessary for retaining its shape after calcination. Here, we propose to use a DMSO-based photosensitive medium to manufacture a 3D organogel by TPP and apply the sparse infill exposure method to overcome this challenge. Afterward, the lipid is infiltrated into the micro mold by IJP to precisely fill the microcavity. Selective leaching of the soluble mold results in complex-shaped lipid microparticles. Both hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs and magnetic nanoparticles (MNP) have also been mixed with the lipid to manufacture lipid microparticles to demonstrate lipid microparticles’ potential in drug delivery application.

Results and discussions

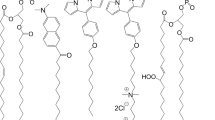

The fabrication of the water-soluble 3D micro mold starts with the 3D printing of a DMSO organogel by TPP using a photosensitive medium containing PEGDA and DMSO (Fig. 1a). DMSO has been chosen as a co-solvent for the medium because it has a lower volatility than other polar aprotic solvents and is miscible with both PEGDA and the photo-initiator. The low volatility of DMSO minimizes changes in the photosensitive medium properties during TPP due to solvent evaporation, since TPP operates in an open environment with a small amount (less than 100 μL) of photosensitive medium. The optimization of the TPP condition and photosensitive medium composition can be found in Supplementary Fig. S1. Organogel structures with both negative and positive resolutions down to 2 µm can be fabricated using TPP with a photosensitive medium (Supplementary Fig. S2). Throughout TPP, DMSO organogel microstructures with different designs of negative cavities (helix, scaffold) with openings have been successfully fabricated (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. S3).

a TPP fabrication of a dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)/ polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA) organogel (b) Transformation into a Ca2+ hydrogel by the development of the structure in DMSO and two steps solvent infusion in water and in calcium nitrate tetrahydrate precursor. c Calcination of a Ca2+ hydrogel under argon flow at 0.2 °C/min to form a Ca-based mold. d PVA coating of the Ca-based mold. e Infiltration of molten lipid-drug-magnetic nanoparticles (MNP) mixture into the water-soluble 3D micro mold by IJP of molten lipids into its opening. f Selective leaching of the mold in water at 20 °C and drying to obtain the complex-shaped lipid microstructure.

After printing, the DMSO organogel is immersed in DMSO to exchange unpolymerized PEGDA molecules with DMSO. During this process, DMSO penetrates the cross-linked walls to access the voids, dilutes the uncrosslinked PEGDA, and subsequently replaces it. Then a two step solvent infusion is performed to replace DMSO with water and then water with an aqueous solution of 5.07 M calcium nitrate tetrahydrate solution which transforms the DMSO organized into a hydrogel loaded with Ca2+ (Fig. 1b). This hydrogel converts into a Ca-based structure by calcination at 700°C. Rapid thermal decomposition during the calcination hinders uniform isotropic shrinkage, forming cracks and defects in the structure41. To minimize the risk of cracking during calcination, the process has been carried out with a temperature ramp of 0.2 °C/min under argon flow. The original 3D structure of DMSO organogel remained intact after calcination, except for a reduction in its volume regardless of its design (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. S4). The resulting Ca-based structure is soluble in water, but its high porosity makes it unsuitable to be used as a mold. To overcome this problem, a polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) layer was coated on the Ca-based structure to fill the pores with PVA by simply dipping it in a PVA solution (Fig. 1d). PVA has been selected as a coating material because it has a high solubility in water while it is insoluble in lipids, and forms uniform thin films on the hydrophilic surfaces42.

3D lipid microparticles are manufactured by infiltrating molten lipids into the water-soluble 3D micro mold by IJP (Fig. 1e). IJP allows a precise filling of the micro mold by printing nanoliters of molten lipid droplets into its opening of 100 µm in diameter, without depositing lipids on the surface of the mold, which might hinder the leaching process carried out afterward. In this research, we dispersed drugs (5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or Fenofibrate) and MNP into the molten lipid to use the 3D lipid microstructures as a drug delivery device for its potential application. Finally, a 3D lipid microparticle is obtained by dissolving the mold in water at 20 °C, followed by drying at 20 °C, as shown in Fig. 1f. To demonstrate the versatility of our technology, we fabricated 3D lipid structures with different designs and material compositions (with and without MNP) (Supplementary Fig. S5).

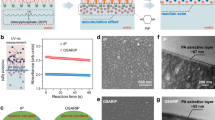

For ordinary TPP printing of polymers, the laser exposes the full volume of the 3D structure sequentially, polymerizing 100% of the 3D design, as shown in Fig. 2a. In 3D printing, such a full exposure is generally referred to as “solid interior fill or “solid fill”. However, when using a solid fill strategy, the fabricated hydrogels did not keep their original shape after calcination but instead crumbled into a white powder. The TGA of the Ca2+ loaded hydrogel made with the solid fill strategy (Fig. 2a) shows that the gel contained 4.7 wt% of Ca precursor, and retained 2.5 wt% of its original mass after calcination. This may be due to the high density of the polymerized part, resulting in a poor infusion of the Ca precursor in the polymer matrix.

a Optical images of 3D organogels built using solid fill and sparse infill strategies and the TGA profiles of the corresponding hydrogel infused with calcium nitrate precursor at 1 °C/min. b DSC profiles of hydrogel infused with calcium nitrate at 10 °C/min. c SEM images of calcined Ca2+ hydrogels prepared with photosensitive medium containing 35 vol% and 0 vol% DMSO, along with their TGA profiles. d Optical images of calcined hydrogels prepared with 0.93 M and 5.07 M calcium nitrate precursor and the relationship between Ca2+ concentration and its dimensions remaining after calcination (n = 3). e EDS analysis of the Ca-based mold. f XRD analysis of the Ca-based mold. Ref. ICSD #, reference pattern from Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (details in Experimental methods).

To infuse a large amount of calcium nitrate into the 3D hydrogel mold, another filling strategy was implemented during TPP fabrication, generally referred to as “sparse infill” in 3D printing. In this method, the laser exposes the contour of the 3D shape for shell fabrication and builds a homogeneously distributed scaffold inside the shell (Fig. 2a). This results in the interior of the 3D part being only partially filled (40 to 60% of the volume is filled). The calcium nitrate-infused hydrogel made with the sparse infill strategy kept its original 3D oraganogel shape after calcination. The TGA of the corresponding calcium nitrate-infused hydrogel (5.07 M Ca2+ concentration) (Fig. 2a) shows that the gel contained 19.2 wt% water and retained 16.1 wt% of its original mass after calcination. The sparse infill exposure method not only significantly decreases the TPP process time by 40–60% compared to the solid fill exposure strategy but also provides conditions for infusing a much larger volume of calcium nitrate solution into the hydrogel structure thanks to the interconnected voids inside the shell. Therefore, the sparse infill exposure method has been used for all TPP components fabricated in this research.

Figure 2b shows the DSC profile of the sparse infill hydrogel infused with calcium nitrate solution (10 °C/min temp ramp followed by isothermal hold at 600 °C for 30 min under nitrogen flow). The positive heat flow from 30 °C followed by an endothermic peak at 88 °C and the mass loss in TGA until 100 °C, correspond to the water infused into the hydrogel that evaporates below 100 °C and dehydration of the calcium nitrate tetrahydrate43. From the TGA of the sparse infill hydrogel infused with calcium nitrate solution, the onset of mass loss is 230 °C, while the onset of mass loss of the hydrogel made with the solid fill strategy is 310 °C (Fig. 2a). This difference is related to the different amounts of calcium nitrate (which is an oxidizer) present in the structures that enhance the decomposition of PEGDA by oxidation which corresponds to the exothermic peak at 230 °C in DSC and is further supported by no mass loss at 230 °C in TGA of hydrogel without calcium nitrate (Supplementary Fig. S6). The exothermic peak at 313 °C corresponds to the decomposition of the PEGDA matrix by oxygen44 which is in agreement with the TGA of PEGDA hydrogel without calcium precursor infusion shows an onset of mass loss around 310 °C (Supplementary Fig. S6). The decomposition of the PEGDA matrix continues until 600 °C, which can be seen both from the TGA of the hydrogel with and without calcium precursor infusion caused by the rapid heating rate without isothermal hold. The endothermic peak at 512 °C corresponds to the melting of anhydrous calcium nitrate43. The exothermic peak at 538 °C is related to the transition of calcium nitrate into calcium oxide. Finally, the peak at 600 °C corresponds to the CaO-mediated exothermic decomposition of organic compound residues that remained after the incomplete and slow decomposition of PEGDA starting from a lower temperature.

When fabricating the organogel, a photosensitive medium with a lower DMSO concentration is beneficial for achieving sufficient polymerization density to form a polymer matrix by TPP, with 35 vol% DMSO being the upper limit (Supplementary Fig. S1). However, when the concentration of DMSO in the organogel decreases, the rate and amount of solvent exchange by infusion also decrease due to the higher reticulation of the obtained polymer network. Figure 2c shows the TGA of hydrogel components infused with calcium nitrate solution fabricated with 35 vol% and 0 vol% DMSO photosensitive medium. The hydrogel prepared from a 0 vol% DMSO photosensitive medium infused with 5.07 M Ca2+ precursor retained only 8 wt% of its original mass while the one prepared with 35 vol% DMSO infused with 5.07 M Ca2+ precursor retained 12.7 wt% after calcination. Although a higher degree of reticulation of the polymer network hinders the solvent infusion process, the calcined hydrogel prepared with 0 vol% DMSO photosensitive medium retained its original shape because of the precursor infused into the voids created by the sparse infill exposure method. However, it shrank to 58% of its initial dimension with large defects and cracks. In comparison, the same component prepared with 35 vol% DMSO shrank to 87% of its original dimensions without observable defects or cracks on its exterior by microscope (Fig. 2c). Therefore, a 35 vol% DMSO photosensitive medium has been used for all fabrication processes in this research to facilitate solvent infusion and to maintain the original shape and dimensions after calcination.

The shrinkage of the calcined calcium nitrate-infused hydrogel is influenced by the Ca2+ concentration of the precursor. Figure 2d shows that the dimension of the calcined hydrogel are linearly proportional to the Ca2+ concentration of its precursor. The hydrogel prepared with a 0.93 M Ca2+ precursor retained its original shape without observable cracks or defects by microsope on its exterior after calcination (Fig. 2d), with 22% shrinkage in its original dimensions, retaining 2.2 wt% of its original weight (Supplementary Fig. S7). Although hydrogel fabricated by sparse infill prepared with 0.93 M precursor retained a similar weight after calcination (2.2 wt%) with the solid hydrogel prepared with a 5.07 M precursor (2.5 wt%), it retained its original shape, while the solid hydrogel formed white powder instead. This is due to the interconnected distribution of the infused Ca precursor in the hydrogel, thanks to the interconnected voids created by sparse infill exposure, thus allowing isotropic shrinkage of the Ca-based mold without changing the dimensions of the organogel.

The energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping of the Ca-based structure obtained after calcination showed a homogeneous distribution of Ca, C, and O throughout its surface (Fig. 2e). The XRD analysis of this component (Fig. 2f) revealed that the infused calcium nitrate tetrahydrate was mainly converted to calcium carbonate (CaCO3) in aragonite (61 wt%) and calcite (28 wt%) forms (Supplementary Fig. S8) after calcination. The calcium carbonate is formed by the reaction between calcium oxide and carbon dioxide produced by the polymer decomposition. The prevalence of aragonite which is a high-pressure polymorph of calcium carbonate suggests that there was naturally generated internal pressure in the structure during calcination. Internal pressure may be caused by the material inside the voids of the scaffold filling the interior of the structure decompose faster than the one of the outer shell due to their different material densities. The remaining calcium content corresponds to calcium hydroxide (8 wt%) and calcium oxide (3 wt%). Calcium oxide is generated from the decomposition of calcium nitrate, and calcium hydroxide is formed by the reaction of calcium oxide with water molecules. EDS and XRD analysis revealed that the Ca-based structure formed after calcination is composed entirely of water-soluble materials.

The porosity of the mold can be controlled by adjusting the scaffold fill density using the sparse infill method, which is regulated by scaffold spacing and scaffold wall thickness (Supplementary Table S2). We fabricated cuboid organogels with dimensions of 1000 × 1000 × 500 µm at different scaffold fill densities (22%, 47%, 73%) (Fig. 3a). After transferring the organogels into Ca-based structures by solvent exchange with 5.07 M Ca2+ precursor and calcination, the volume and weight of the cuboids were measured to calculate the porosity of each structure. Structures with a higher scaffold fill density exhibited higher porosity because the scaffold structure reduced the available volume for the infused Ca precursor. The porosity of the solid-filled structure after calcination, with dimensions of 1000 µm × 1000 µm × 5 µm infused with 5.07 M Ca2+ precursor (32%), is lower than that of the structure fabricated using the sparse infill method (39% porosity at a 22% scaffold fill density) while there is more shrinkage in dimension (73% of original volume) than the structure fabricated by sparse infill method (87%). Therefore, the increase in porosity can be attributed to the shrinkage difference between the void and scaffold regions, which is likely caused by variations in Ca2+ concentration between these parts. The porosity of the structure had a significant impact on leaching time; the higher the porosity of the Ca mold, the shorter the leaching time as shown in Fig. 3a. However, a higher scaffold filing density results in longer total TPP writing time with a 20% increase when the filling density is increased by 25%.

a Effect of the scaffold fill density in the organogel structure on the porosity of the Ca-based structure and their leaching time (n = 3) and optical images of different scaffold fill densities. b Ca-based mold before PVA coating. c Ca-based mold after PVA coating. d Lipid microparticle encapsulating MNPs. e Helix lipid microparticles with varying dimensions, featuring helical body diameters of ranging from 10 to 0.5 µm. f Enlarged images of helical lipid microparticles with diameters of 1 µm and 0.5 µm, showing imperfections due to insufficient fabrication resolution.

The external morphologies of the Ca-based mold before and after the PVA coating were observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The Ca-based mold retained its original 3D shape without cracks and defects larger than 10 µm in its exterior (Fig. 3b) (Other designs are shown in Supplementary Fig. S9). SEM images at higher magnification of the mold surface indicate that the surface is highly porous with interconnected cracks of width narrower than 1 µm. The clusters of particles on the surface may have been generated by the residual calcium precursor on the hydrogel surface. However, after PVA coating, the number of cracks and defects decreased on the exterior surface according to SEM image (Fig. 3c) with PVA filling the pores, resulting in a smoother surface without cracks or pores. Filling the bare Ca-based mold required 1550 lipid droplets as the printed lipid permeated into the pores of the bare mold, while the PVA-coated mold required 420 droplets only. This result indicates that the PVA coating effectively improved the structural integrity and its impermeability to lipids.

Figure 3d shows SEM images of a lipid structure fabricated through lipid infiltration and mold leaching using a water-soluble 3D micro mold. The complex design of the cavity inside the original mold design was unchanged by solvent exchange, calcination and PVA coating. SEM images of lipid microparticles with other designs are shown in Supplementary Fig. S10. The SEM images at higher magnification of their surface shows pores and wrinkles with clusters of aggregated MNPs. Careful handling of lipid microparticles is required due to their poor mechanical properties.

To evaluate the resolution limits of the developed technology, helix-shaped lipid microparticles with varying dimensions were fabricated with a 25× magnification objective. These microparticles featured helical body diameters (representing the width of the helix lines) of 10, 6, 4, 2, 1, and 0.5 µm. The microstructures were fabricated on a plate with 100 µm thickness to facilitate easy handling of the samples. Using the developed method, we successfully fabricated microstructures with helical body diameters down to 2 µm (Fig. 3e). However, lipid microparticles with 1 µm and 0.5 µm diameters failed to obtain the helical form (Fig. 3f). This limitation is attributed to the resolution constraints of the TPP system, as the process was conducted using a 25× magnification objective resulting in a voxel size of 0.5 µm in the x-y plane and 2 µm in the z-direction. The resolution of the structure can be further improved by using higher objectives for TPP.

Figure 4a depicts the in vitro accelerated degradation of a helix lipid microparticle immersed in a 30 mg/ml lipase solution at 37 °C. The structure degrades starting from its exterior surface over time and is completely degraded after 8 min, leaving traces of MNPs that were encapsulated inside the lipid. In comparison, helix lipid microparticles with the same dimensions and material composition didn’t show degradation under optical observation in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37 °C over 3 days (Supplementary Fig. S11).

a In vitro accelerated degradation of the lipid microparticle: Optical images of the lipid microparticle immersed in lipase solution at 37 °C over time. b Drug loading efficiency of 5-FU encapsulated in helical lipid microparticles prepared at different leaching temperatures. c In vitro drug release profile of the helix lipid microparticle immersed in PBS at 37 °C (n = 3). d Magnetic hysteresis curve of 30 helix lipid microparticles e Time-lapse images of the magnetic manipulation of a helix lipid microparticle by a rotating magnetic field and the velocity of the lipid microparticles under different rotating magnetic field frequencies (n = 3). f Time-lapse images of the magnetic manipulation of a cubic scaffold lipid microparticles by a magnetic gradient.

Evaluating the drug loading efficiency of the fabricated lipid microparticles is important to apply them in drug delivery applications. Selective leaching of the soluble mold is a pivotal step in optimizing drug loading efficiency. Initially, the lipid microparticle contacts water through the mold opening, gradually increasing its exposure as the mold degrades, leading to unwanted drug release into the leaching medium. Figure 4b shows the drug loading efficiency of 5-FU (hydrophilic drug) encapsulated into helix lipid microparticles exposed to different temperatures during leaching. The microparticle prepared at 20 °C exhibited the highest drug loading efficiency with 83% remaining in the structure after leaching, followed by 72% for the one prepared at 2 °C, and 52% for the one prepared at 37 °C. This trend is attributed to the inverse relationship between dissolution time and temperature, while the drug release rate is directly proportional to temperature. Therefore, finding the optimal temperature is essential to minimize drug loss during the leaching process.

Figure 4c shows the in vitro drug release profile of 5-FU and fenofibrate encapsulated in lipid microparticles immersed in PBS at 37°C. After an initial burst release on day 1, a continuous release is observed at a decreasing rate until day 21 for both 5-FU and fenofibrate. 72.1% of the loaded 5-FU has been released for 21 days while 24.5% of fenofibrate has been released during the same period. 5-FU particles are dispersed in an undissolved state (Supplementary Fig. S12) within the lipid matrix because it is a hydrophilic drug with a water solubility of 12.2 mg/mL45. Its release is primarily governed by diffusion through water-infiltrated pores that are either inherently present or formed due to the dissolution of the drug particles over time. This mechanism results in a relatively fast release rate for 5-FU. In contrast, fenofibrate is soluble in the lipid matrix (Supplementary Fig. S12) because it is a lipophilic drug with very low water solubility (0.3 µg/mL) and a high solubility in lipids (100 mg/mL)46. Its release occurs by diffusion through the lipid matrix or by degradation of lipid, which leads to a slower release rate compared to 5-FU. The use of lipid components allows the encapsulation and release of poorly water-soluble drugs. This cannot be achieved by biodegradable polymers but is possible with lipids because they can dissolve poorly water-soluble drugs. This can increase the applicability of drug delivery devices to a diverse range of drugs since many advanced newly developed drugs are poorly water-soluble47,48.

The magnetic hysteresis curve of 30 helix lipid microparticles with the encapsulated iron oxide MNPs indicates that it has superparamagnetic properties (Fig. 4d). The helical structure enables the manipulation of the lipid microparticle in a liquid environment under low Reynolds number conditions by rotation along its longitudinal axis in a corkscrew motion49. Therefore, helix lipid microparticles can be externally manipulated in a liquid by exposing them to an external rotating magnetic field (ERMF). By controlling the direction and frequency of the ERMF, the helix lipid microparticle can be guided in locomotion in PBS, as depicted in Fig. 4e. The locomotion of helix lipid microparticles can be found in Supplementary Movie 1. Its velocity increased linearly with the increase in ERMF frequency, reaching a maximum velocity of 92 µm/s at 3 Hz frequency, followed by a huge decrease at higher frequency (Fig. 4e. The decrease in velocity is caused by the unsynchronized physical rotation with the ERM field due to insufficient magnetization, a phenomenon known as step-out frequencies50. Non-helix shape lipid microparticles such as cubic scaffolds can be manipulated by magnetic gradient as shown in Fig. 4f (Supplementary Movie 2)

Discussion

In this study, we developed a fabrication process for complex-shaped lipid microparticles with a resolution of 2 µm using water-soluble 3D micro molds. The water-soluble micro molds were fabricated through TPP with solvent exchange, followed by calcination and PVA coating. Lipid infiltration was then achieved via IJP, followed by leaching. Our method has several advantages over the state of the art of previous water-soluble molds which were fabricated using salt particle-loaded ink by SLA34 and PVA micro molds by direct ink writing36. The main advantage of our approach compared to salt particle-loaded inks is its resolution down to 2 µm, whereas salt particle-loaded inks have a resolution of a few hundred micrometers. This difference is due to the intrinsic size of submicron salt particles, leading to light scattering and absorption caused by dispersed microparticles, while our approach uses a particle-free photoresist. Also, our method can be applied to both SLA and TPP, whereas the salt ink method can only be applied to SLA due to the high concentration of particles (65 wt%), which is a further drawback in the quest for high resolution. Furthermore, our method can be used for further miniaturization after photopolymerization by controlling the calcium precursor concentration, unlike salt-loaded inks whose shrinkage is predetermined by the dimension of the photopolymerized structure. Finally, our method does not involve surfactants or any complex photoresist preparation processes to reduce viscosity and improve the dispersion of salt microparticles in the photoresist. It uses a simple polymer, organic solvent, and photoinitiator mixture. The one downside of our Ca-PVA approach is that it may not be compatible with the fabrication of materials that can damage the PVA coating, such as molten metals at high temperatures. Compared to the state of art of PVA micro mold, our approach overcame the resolution limit of PVA micro-molds which is constrained to tens of microns due to the physical diameter of the direct ink printer nozzle, to the single-micron range by using TPP. Furthermore, our approach enables the fabrication of complex-shaped 3D structures, such as helices and overhangs, which are not easily achievable with direct ink writing technology.

The sparse infill method allowed large amounts of calcium nitrate solution to infuse into the structure, overcoming the poor solvent infusion caused by the high degree of reticulation of polymer networks created by TPP. After calcination, the structures shrank to 50%-90% of their original dimensions, depending on the calcium precursor concentration, allowing further miniaturization of the mold after printing. TGA, DSC, and EDS analyses confirmed that the Ca-based mold is fully water soluble.

A PVA coating was applied to the Ca-based mold to fill the pores and prevent lipid permeation. Selective leaching of the mold with water left only the lipid microparticles. The leaching step reduced the encapsulation efficiency of the cargo inside the microparticles and limited fabrication with fast-dissolving SEDDS lipid materials. The leaching time can be reduced by increasing the porosity, which is achieved by increasing the scaffold fill density of the structure. However, this comes with a trade-off, as higher scaffold fill density results in longer total TPP writing time. Future studies should focus on optimizing the pH and temperature of the leaching medium to address these limitations. The resolution and miniaturization of the lipid microparticles can be further enhanced by designing small features down to 1 µm by using higher objectives with smaller voxel volume with a tradeoff with printing speed. However, the difficulty in handling the mold and the lipid microparticles needs to be addressed beforehand. For scalable mass production and to reduce the fabrication cost, TPP can be replaced by other more economical fabrication tools such as SLA while keeping the resolution of 10–50 µm which is much lower than the state of the art of current water-soluble molds. Furthermore, by controlling the shrinkage of the mold through adjustments in calcium precursor concentration as shown in Fig. 2d, the resolution of mold prepared by SLA can be improved below its fabrication limit to match that of TPP.

The developed water-soluble mold is compatible with lipids during the leaching step without erosion and shape change of the lipids by the solvent. It also eliminates the physical disassembly process for the removal of the mold which prevents the stress-induced fracture in mechanically fragile lipids. Furthermore, shape complexity and 2 µm resolution inherited from the TPP expand the design and precision limitation of previous lipid fabrication processes.

Drug-incorporated lipid microparticles released both water-soluble and poorly water-soluble drugs over a prolonged period. Furthermore, by incorporating MNPs into the lipid structures and shaping them as helix, these lipid microparticles can be manipulated magnetically in vitro. These features open up the possibility of our technology for targeted drug delivery as its future application. Future studies are crucial to establish the capability of drug-loaded lipid microparticles for in vitro and in vivo drug delivery, paving the way for their application in targeted drug delivery systems.

The developed technology to fabricate Ca-based water-soluble molds may enable more technological opportunities beyond what is shown in this study. The technology can be extended to molding various materials that are insoluble or slowly soluble in water, such as biodegradable polymers or molten metal. This allows their fabrication into complex-shaped objects without the defect-vulnerable interfaces often created by other manufacturing technologies such as binder jetting or fused deposition modeling since utilize powder-based or layered deposition processes that can lead to weak spots and inconsistencies in the final product51,52. Complex-shaped lipid microparticles have the potential to be applied to various fields in addition to drug delivery applications. For example, in bioresorbable electronics, complex-shaped lipid microparticles may serve as substrates for electronic components, improving mechanical properties by being designed in specific shapes like serpentine or honeycomb structures while possessing high biocompatibility and biodegradability compared to synthetic biodegradable polymers.

Methods

Fabrication of water-soluble 3D micro molds

The PEGDA/DMSO-based photosensitive medium was prepared by mixing 65 vol% of PEGDA (Mn = 575), 35 vol% of DMSO, and 50 mg/ml of Irgacure-369 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The photosensitive medium was drop-cast on a silicon substrate and placed into the TPP tool (Photonic Professional GT; Nanoscribe GmbH, Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen, Germany). TPP was carried out with a laser power of 150 mW using a 10x and 25x magnification objective lenses in direct contact with the medium (most printing has been done with the 10x objective unless otherwise stated). Sparse infill and solid fill methods for the 3D structure exposure were programmed by Describe software (Photonic Professional GT; Nanoscribe GmbH, Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen, Germany) (Detailed parameters are shown in Supplementary Table S1). After printing, the 3D organogel was immersed in 80°C DMSO for 24 hours, 80°C water for 12 hours, and finally in a 5 M calcium nitrate tetrahydrate solution for 24 hours for solvent infusion. Calcination was performed under 20 mbar argon flow in a tubular furnace (Tube furnaces; Carbolite Gero GmbH, Neuhausen, GER) with a 0.2 °C/min temperature ramp to 700 °C and a 3 °C/min temperature ramp during the cooling phase. For the PVA coating, PVA (Mw 31,000–50,000; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in deionized water at a concentration of 20 mg/ml. A 2 µL of the PVA solution was drop-casted on the top of the Ca-based structure using a micropipette. This allowed to fully immerse the Ca-based structure in the PVA solution. The water evaporated within 5 minutes after drop casting and the structure was further dried over 12 h before infiltration. The mold is handled using precision tweezers on a silicon substrate and observed under an optical microscope to rotate and align the holes in the desired direction. Translation of the mold is achieved by moving the silicon substrate.

Infiltration of molten lipid by IJP

The lipid was prepared by mixing a lipid mixture consisting of mono-, di-, and triglycerides esters of fatty acids with a low hydroxide ratio (Suppocire CM; Gattefosse SAS, Lyon, France) with Fe3O4 MNPs (100 nm lipid coated; Chemicell GmbH, Berlin, GER) with a concentration of 5 wt% and with drugs: 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 5 mg/ml or Fenofibrate 50 mg/ml (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 50 °C for 20 min using a vortex mixer and 15 min by ultrasound sonication. The prepared lipid mixture was inkjet printed by an automatic inkjet printer (JetlabII; MicroFab Technologies, Inc., Plano, TX, USA). The temperature of the lipid-MNP mixture reservoir, connection tube, and print head was maintained at 65, 70, and 50 °C, respectively, during printing.

Selective leaching of the mold and drying

The lipid-infiltrated mold was immersed in distilled water (pH 5.3) at different temperatures (2 °C, 20 °C, and 37 °C) under 200 rpm orbital shaking. Depending on the temperature, the time required for total dissolution of the mold varied: 48 h at 2 °C, 8 h at 20 °C, and 5 hours at 37 °C. After, the lipid microparticles were retrieved from the water, and dried overnight at 20 °C.

Dimension measurement

The reference to the dimension after calcination corresponds to the dimension of the calcium ion-infused hydrogel. The side length of the structure has been measured by an optical microscope and compared to the same side length after calcination. The shrinkage value was calculated assuming isotropic shrinkage in all directions, using the three-squared ratio of the side lengths

TGA

TGA (TGA 4000; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) was performed under a 20 ml/min synthetic air (20% oxygen, 80% nitrogen) flow environment. The samples were heated with an isothermal hold for 1 min at 30 °C, followed by a temperature increase to 700 °C with a ramp rate of 1 °C/min. 30 molds were loaded into crucibles right after they were taken out from the calcium precursor which resulted in the average starting mass of 7.5 ± 0.3 mg.

DSC

DSC (DSC 8000, Perkin Elmer; Waltham, MA, USA) was performed under a 20 ml/min nitrogen flow environment. The samples were heated with an isothermal hold for 1 min at 30 °C followed by a temperature increase to 600 °C with a ramp rate of 10 °C/min and an isothermal hold for 10 min at 600 °C. 10 molds were loaded into crucibles right after they were taken out from the calcium precursor which resulted in the average starting mass of 2.4 ± 0.2 mg.

XRD

XRD samples are prepared by grinding Ca-based microstructures into powder to fill the amorphous zero-background sample holders with dimensions of 10 × 10 × 0.1 mm. XRD measurements were conducted using Bruker D8 Discover (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) in Bragg Brentano mode. The equipment was equipped with a Johansson Kalpha1 monochromator and a LynxEye 1D detector. Experimental patterns were compared to references from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database53.

Porosity measurement and leaching time measurement

1000 × 1000 × 500 µm cuboids with varying scaffold spacing and scaffold wall thicknesses were fabricated for different scaffold fill densities (Supplementary Table S2). For the material density (shell part), cuboid structures with dimensions of 1000 µm × 1000 µm × 5 µm, matching the thickness of the shell part in the sparse infill method, using the solid fill method have been fabricated. The cuboids underwent the same solvent exchange and calcination process to convert them to Ca-based cuboids. The volume of the cuboids was calculated through optical microscope measurements, and their mass was measured. The porosity of the cuboids was determined using Eq. (1), where density refers to the mean density of the various calcium-based materials, calculated from XRD analysis results.

To measure the leaching time of the cuboids, they were immersed in water at 20 °C under 200 rpm orbital shaking, and the time for complete dissolution under optical observation was measured.

SEM and EDS

Samples are observed by SEM (SEM merlin; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at an acceleration voltage of 4 kV. The samples are fixed on Si substrate by carbon tape or PVA (only for PVA-coated mold). EDS was performed by the same instrument by using the EDS detector (X-Max 50 mm2 detector; Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK), with an applied voltage of 6 kV.

In vitro degradation of lipid microparticles

A lipase solution has been prepared by dissolving 30 mg/ml (Lipase from porcine pancreas; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in deionized water. The lipid microparticles were immersed in 2 ml of lipase solution and PBS at 37 °C and its optical image was observed over time.

In vitro drug loading efficiency measurement

Drug-loaded lipid microparticles were completely dissolved in 100 µL of DMSO by incubating at 37 °C and 30 rpm for 24 h. After incubation, the absorbance of the DMSO was measured using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (NanoDrop™ 2000c Spectrophotometers; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to determine the drug concentration. The drug loading efficiency was calculated using Eq. (2),

where Cl refers to the drug concentration in DMSO, Vl is the volume of DMSO (100 µL), n is the number of immersed lipid microparticles (10), Cp is the drug concentration in the lipid mixture, and Vp is the volume of the lipid particles (estimated by a 90% shrinkage of their original design).

In vitro drug release measurement

Lipid microparticles were placed in a 2 mL micro-centrifuge tube containing 100 µL of PBS and incubated at 37 °C on a 30 rpm orbital shaker. A 2 µL aliquot of the supernatant was withdrawn, and its UV absorbance was measured at each measurement point using PBS as a blank with a UV–vis spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000C). After each measurement, the tubes were refilled with fresh PBS. This method allows the measurement of the main absorption peaks of the two drugs used in this study (5-FU: 265 nm, Fenofibrate: 290 nm). At each measurement point, the concentration of each drug present in the supernatant was obtained using a previously established calibration curve.

Magnetic hysteresis curve measurement

The magnetic hysteresis of 30 lipid microparticles was measured in a −20 to 20k Oe magnetic field using a SQUID magnetometer (Quantum Design MPMS system; Quantum Design GmbH, Pfungstadt, GER) at room temperature.

In vitro magnetic manipulation

A single helix lipid microparticle was put in a glass dish filled with PBS solution. For electromagnetic actuation, the lipid microparticle in the PBS solution was manipulated under an external ERMF with 30 mT intensity with in-plane rotation generated by the magnetic actuation system (Minimag; Magnebotix, Zurich, Switzerland). Cubic scaffold lipid microparticle was immersed in the same condition and manipulated with a magnetic gradient with an intensity of 2000 mT/cm. Time-lapse images were obtained using an optical microscope at 14 fps to track the position of the lipid microparticles.

Statistical analysis

Data collected by at least three independent experiments are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. All data with a repetition number has been obtained from the particles/molds fabricated from the different batches.

Data availability

All data that support the key findings in this study are available within the main text and the Supplementary Information file. Source data are provided with this paper. Any additional requests for information are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

McHugh, K. J. et al. Fabrication of fillable microparticles and other complex 3D microstructures. Science 357, 1138–1142 (2017).

Vargason, A. M., Anselmo, A. C. & Mitragotri, S. The evolution of commercial drug delivery technologies. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 951–967 (2021).

Kim, Y. et al. Ultrahigh‐porosity MgO microparticles for heat‐energy storage. Adv. Mater. 35, 2204775 (2023).

Chang, Y. et al. Application of hard ceramic materials B4C in energy storage: Design B4C@ C core-shell nanoparticles as electrodes for flexible all-solid-state micro-supercapacitors with ultrahigh cyclability. Nano Energy 75, 104947 (2020).

Hwang, H. & Jeong, U. Microparticle‐Based Soft Electronic Devices: Toward One‐Particle/One‐Pixel. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1901810 (2020).

Trotta, M., Debernardi, F. & Caputo, O. Preparation of solid lipid nanoparticles by a solvent emulsification–diffusion technique. Int. J. Pharm. 257, 153–160 (2003).

Fessi, H., Puisieux, F., Devissaguet, J. P., Ammoury, N. & Benita, S. Nanocapsule formation by interfacial polymer deposition following solvent displacement. Int. J. Pharm. 55, R1–R4 (1989).

Gorrasi, G. & Sorrentino, A. Mechanical milling as a technology to produce structural and functional bio-nanocomposites. Green. Chem. 17, 2610–2625 (2015).

Martins, M. A., Santos, C., Almeida, M. M. & Costa, M. E. V. Hydroxyapatite micro-and nanoparticles: nucleation and growth mechanisms in the presence of citrate species. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 318, 210–216 (2008).

Kronenfeld, J. M., Rother, L., Saccone, M. A., Dulay, M. T. & DeSimone, J. M. Roll-to-roll, high-resolution 3D printing of shape-specific particles. Nature 627, 306–312 (2024).

Lee, B. K. et al. Fabrication of drug-loaded polymer microparticles with arbitrary geometries using a piezoelectric inkjet printing system. Int. J. Pharm. 427, 305–310 (2012).

Guan, J., Ferrell, N., Lee, L. J. & Hansford, D. J. Fabrication of polymeric microparticles for drug delivery by soft lithography. Biomaterials 27, 4034–4041 (2006).

Li, W. et al. Microfluidic fabrication of microparticles for biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 5646–5683 (2018).

Hou, X., Zaks, T., Langer, R. & Dong, Y. Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 1078–1094 (2021).

Xu, L. et al. Lipid nanoparticles for drug delivery. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2, 2100109 (2022).

Puglia, C. & Bonina, F. Lipid nanoparticles as novel delivery systems for cosmetics and dermal pharmaceuticals. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 9, 429–441 (2012).

Weiss, J. et al. Solid lipid nanoparticles as delivery systems for bioactive food components. Food Biophys. 3, 146–154 (2008).

Bunjes, H. Lipid nanoparticles for the delivery of poorly water-soluble drugs. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 62, 1637–1645 (2010).

Almeida, A. J. & Souto, E. Solid lipid nanoparticles as a drug delivery system for peptides and proteins. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 59, 478–490 (2007).

Jindal, A. B. The effect of particle shape on cellular interaction and drug delivery applications of micro-and nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 532, 450–465 (2017).

Yang, Y., Nie, D., Liu, Y., Yu, M. & Gan, Y. Advances in particle shape engineering for improved drug delivery. Drug Discov. Today 24, 575–583 (2019).

Champion, J. A., Katare, Y. K. & Mitragotri, S. Particle shape: a new design parameter for micro-and nanoscale drug delivery carriers. J. Controlled Rel. 121, 3–9 (2007).

Kyobula, M. et al. 3D inkjet printing of tablets exploiting bespoke complex geometries for controlled and tuneable drug release. J. Controlled Rel. 261, 207–215 (2017).

Içten, E. et al. Dropwise additive manufacturing of pharmaceutical products for amorphous and self emulsifying drug delivery systems. Int. J. Pharm. 524, 424–432 (2017).

Johannesson, J., Khan, J., Hubert, M., Teleki, A. & Bergström, C. A. 3D-printing of solid lipid tablets from emulsion gels. Int. J. Pharm. 597, 120304 (2021).

Vithani, K. et al. A proof of concept for 3D printing of solid lipid-based formulations of poorly water-soluble drugs to control formulation dispersion kinetics. Pharm. Res. 36, 1–13 (2019).

Kreye, F. et al. Controlled release implants based on cast lipid blends. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 43, 78–83 (2011).

Davoodi, E., Montazerian, H., Khademhosseini, A. & Toyserkani, E. Sacrificial 3D printing of shrinkable silicone elastomers for enhanced feature resolution in flexible tissue scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 117, 261–272 (2020).

Mohanty, S. et al. Fabrication of scalable and structured tissue engineering scaffolds using water dissolvable sacrificial 3D printed moulds. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 55, 569–578 (2015).

Deng, S., Wu, J., Dickey, M. D., Zhao, Q. & Xie, T. Rapid open‐air digital light 3D printing of thermoplastic polymer. Adv. Mater. 31, 1903970 (2019).

Rafalko, C., Stovall, B. J., Zimudzi, T. & Hickner, M. A. Tunable Stereolithography Photopolymerization Resin for Molding Water-Soluble Cavities. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 5, 10097–10104 (2023).

Sanchis‐Gual, R. et al. 3D printed template‐assisted casting of biocompatible polyvinyl alcohol‐based soft microswimmers with tunable stability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2212952 (2023).

Kleger, N., Cihova, M., Masania, K., Studart, A. R. & Löffler, J. F. 3D printing of salt as a template for magnesium with structured porosity. Adv. Mater. 31, 1903783 (2019).

Kleger, N. et al. Light‐based printing of leachable salt molds for facile shaping of complex structures. Adv. Mater. 34, 2203878 (2022).

Wick-Joliat, R., Tschamper, M., Kontic, R. & Penner, D. Water-soluble sacrificial 3D printed molds for fast prototyping in ceramic injection molding. Addit. Manuf. 48, 102408 (2021).

Aabith, S. et al. 3D direct-write printing of water soluble micromoulds for high-resolution rapid prototyping. Addit. Manuf. 58, 103019 (2022).

Jaiswal, A. et al. Two decades of two-photon lithography: Materials science perspective for additive manufacturing of 2D/3D nano-microstructures. Iscience 26, 106374 (2023).

Xu, H. et al. 3D nanofabricated soft microrobots with super-compliant picoforce springs as onboard sensors and actuators. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 494–503 (2024).

Käpylä, E., Turunen, S., Pelto, J., Viitanen, J. & Kellomäki, M. Investigation of the optimal processing parameters for picosecond laser-induced microfabrication of a polymer–ceramic hybrid material. J. Micromech. Microeng. 21, 065033 (2011).

Zhou, X., Liu, X. & Gu, Z. Photoresist Development for 3D Printing of Conductive Microstructures via Two‐Photon Polymerization. Adv. Mater. 36, 2409326 (2024).

Saccone, M. A., Gallivan, R. A., Narita, K., Yee, D. W. & Greer, J. R. Additive manufacturing of micro-architected metals via hydrogel infusion. Nature 612, 685–690 (2022).

Aslam, M., Kalyar, M. A. & Raza, Z. A. Polyvinyl alcohol: A review of research status and use of polyvinyl alcohol based nanocomposites. Polym. Eng. Sci. 58, 2119–2132 (2018).

Zhao, A., Xiong, B., Han, Y. & Tong, H. Thermal decomposition paths of calcium nitrate tetrahydrate and calcium nitrite. Thermochim. Acta 714, 179264 (2022).

Park, J., Bertsch, A., Martin‐Olmos, C. & Brugger, J. Nanoliter Liquid Packaging in a Bioresorbable Microsystem by Additive Manufacturing and its Application as a Controlled Drug Delivery Device. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2302385 (2023).

Enna, S. & Bylund, D. B. xPharm: the comprehensive pharmacology reference (Elseveir Masson, 2008).

Ming-Thau, S., Ching-Min, Y. & Sokoloski, T. D. Characterization and dissolution of fenofibrate solid dispersion systems. Int. J. Pharm. 103, 137–146 (1994).

Benet, L. Z., Broccatelli, F. & Oprea, T. I. BDDCS applied to over 900 drugs. AAPS J. 13, 519–547 (2011).

Benet, L. Z. The role of BCS (biopharmaceutics classification system) and BDDCS (biopharmaceutics drug disposition classification system) in drug development. J. Pharm. Sci. 102, 34–42 (2013).

Nelson, B. J., Kaliakatsos, I. K. & Abbott, J. J. Microrobots for minimally invasive medicine. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 12, 55–85 (2010).

Mahoney, A. W., Nelson, N. D., Peyer, K. E., Nelson, B. J. & Abbott, J. J. Behavior of rotating magnetic microrobots above the step-out frequency with application to control of multi-microrobot systems. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 144101 (2014).

Ziaee, M. & Crane, N. B. Binder jetting: A review of process, materials, and methods. Addit. Manuf. 28, 781–801 (2019).

Baechle-Clayton, M., Loos, E., Taheri, M. & Taheri, H. Failures and flaws in fused deposition modeling (FDM) additively manufactured polymers and composites. J. Compos. Sci. 6, 202 (2022).

Bergerhoff, G. & Brown, I. Crystallographic Databases (International Union of Crystallography, Chester, 1987).

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Project “MEMS 4.0”, ERC-2016-ADG, grant agreement No. 742685). The authors thank Pascal Alexander Schouwink from EPFL XRD SAP for the XRD measurements, LQM EPFL for the magnetic hysteresis curve measurements. Authors are thankful for the David Sargent and Enea Masina from Magnebotix for performing magnetic manipulation experiment of lipid microparticles.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P. and A.B. conceived and designed experiments for fabricating water-dissolvable molds for lipid fabrication. J.P. and A.B. performed printing of organogel J.P. performed fabrication, and characterization of the mold and lipid microstructure. J.P. wrote the first manuscript, A.B. and J.B revised the manuscript. J.B. coordinated and supervised the research. All authors contributed to discussions regarding the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Haifeng Xu and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, J., Brugger, J. & Bertsch, A. Additive manufacturing of water-soluble 3D micro molds for complex-shaped lipid microparticles. Nat Commun 16, 1734 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56984-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56984-7

This article is cited by

-

Fabrication of self-emulsifying lipid microstructure by stiffness-tunable mold for drug delivery applications

Microsystems & Nanoengineering (2025)