Abstract

The backpropagation method has enabled transformative uses of neural networks. Alternatively, for energy-based models, local learning methods involving only nearby neurons offer benefits in terms of decentralized training, and allow for the possibility of learning in computationally-constrained substrates. One class of local learning methods contrasts the desired, clamped behavior with spontaneous, free behavior. However, directly contrasting free and clamped behaviors requires explicit memory. Here, we introduce ‘Temporal Contrastive Learning’, an approach that uses integral feedback in each learning degree of freedom to provide a simple form of implicit non-equilibrium memory. During training, free and clamped behaviors are shown in a sawtooth-like protocol over time. When combined with integral feedback dynamics, these alternating temporal protocols generate an implicit memory necessary for comparing free and clamped behaviors, broadening the range of physical and biological systems capable of contrastive learning. Finally, we show that non-equilibrium dissipation improves learning quality and determine a Landauer-like energy cost of contrastive learning through physical dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The modern success of neural networks is underpinned by the backpropagation algorithm, which easily computes gradients of cost functions on GPUs1. Backpropagation is a ‘non-local’ operation, requiring a central processor to coordinate changes to a synapse that can depend on the state of neurons far away from the synapse. While powerful, such methods may not be available in physical or biological systems with strong constraints on computation and communication.

A distinct thread of learning theory has sought ‘local’ learning rules, such as the Hebbian rule (‘fire together, wire together’), where updates to a synapse are based only on the state of adjacent neurons (Fig. 1). Such local rules allow for, e.g. distributed neuromorphic computation2,3,4. Excitingly, local learning rules also open the possibility of endowing computationally-constrained physical systems with functionality through an in situ period of training, rather than by prior backpropagation-aided design on a computer5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. In these settings, sometimes as simple as chemical reactions within a cell or a mechanical material, there is no centralized control that would allow backpropagation to be a viable method of learning. Consequently, local rules allow for the intriguing possibility of autonomous ‘physical learning’5,14 — no computers or electronics needed — in a range of both natural and artificial systems of constrained complexity such as molecular and mechanical networks.

A Consider a neural network with neuron i firing at rate ηi(t) and synaptic weight wij between neurons i, j. B In Hebbian learning, the weights wij are changed as a function g of the synaptic current sij(t) ~ ηi(t)ηj(t). Here, we generalize the Hebbian framework to a model in which weights wij are changed based on the history of sij(t), i.e., based on \({u}_{ij}(t)=\int_{-\infty }^{t}K(t-{t}^{{\prime} }){s}_{ij}({t}^{{\prime} })d{t}^{{\prime} }\) where K is a memory kernel. We find that non-monotonic kernels K that arise in non-equilibrium systems encode memory that naturally enables contrastive learning through local rules.

In particular, a large class of local ‘contrastive learning’ algorithms (contrastive Hebbian learning22,23,24, Contrastive Divergence25, Equilibrium Propagation26) promise impressive results, but make requirements on the capabilities of a single synapse (or more generally, on learning degrees of freedom). While details differ, training weights generally are updated based on the difference between Hebbian-like rules applied during a ‘clamped’ state that roughly corresponds to desired behaviors and a ‘free’ state that corresponds to the spontaneous (and initially undesirable) behaviors of the system.

Therefore, a central obstacle for autonomous physical systems to exploit contrastive learning is that weight updates require a comparison between free and clamped states, but these states occur at different moments in time. Such a comparison requires memory at each synapse to store free and clamped state information in addition to global signals that switch between these free and clamped memory units and then retrieve information from them to perform weight updates27,28. These requirements make it difficult to see how contrastive learning can arise in natural physical and biological systems and demand additional complexity in engineered neuromorphic platforms.

Here, our primary contribution is to show how a ubiquitous process - integral feedback control - can allow for contrastive learning without the complexities of explicit memory of free and clamped states or switching between Hebbian and anti-Hebbian update modes. Further, in our method, computing the contrastive weight update signal and then performing the update of weights are not separate steps involving different kinds of hardware but are the same unified in situ operation. This approach to contrastive learning, which we call ‘Temporal Contrastive Learning through feedback control’, allows a wide range of physical and biological platforms without central processors to physically learn (i.e., autonomously learn) novel functions through contrastive learning methods.

First, we introduce a simple model of implicit memory in integral feedback-based update dynamics at synapses. Synaptic weights wij are effectively updated by \(\int_{-\infty }^{t}K(t-{t}^{{\prime} }){s}_{ij}({t}^{{\prime} })d{t}^{{\prime} }\), where K is a memory kernel. Updates of this form arise naturally due to integral feedback control29 of synaptic current sij, without the need for an explicit memory element.

Using a microscopically reversible model of the dissipative dynamics at each synapse, we are able to calculate an energy dissipation cost of contrastive learning. The dissipation can be interpreted as the cost of (implicitly) storing and erasing information about free and clamped states over repeated cycles of learning.

Finally, we propose how the non-equilibrium memory needed for contrastive learning arises naturally as a by-product of integral feedback control29,30,31 in many different physical systems. As a consequence, a wide range of physical and biological systems might have a latent ability to learn through contrastive schemes by exploiting feedback dynamics.

Background: Contrastive Learning

Contrastive Learning (CL) was introduced in the context of training Boltzmann machines32 and has been developed further in numerous works22,23,24,25,26.

While CL was originally introduced and subsequently developed for stochastic systems (such as Boltzmann machines)25,32,33, here we review the version of 22,26 for deterministic systems (such as Hopfield networks). CL applies in systems described by an energy function E (more accurately, a Lyapunov function). The system may be supplied with a boundary input and evolves towards a minimum of E, called ‘free state’. The system may also be supplied with a boundary desired output (in addition to the boundary input), driving the system towards a new energy minimum, called ‘clamped state’. Contrastive training requires updating weights as:

where ϵ is a learning rate and \({s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{free}}}}},{s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{clamped}}}}}\) are the synaptic currents at the free and clamped states, defined by \({s}_{ij}=-\frac{\partial E}{\partial {w}_{ij}}\). For example, for a neural network with a Hopfield-like energy function, we recover a conventional Hebbian rule with sij = ηiηj, where ηi is the firing rate of neuron i (Fig. 1B).

A key benefit of contrastive training is that it is a local rule; synaptic weight wij is only updated based on the state of neighboring neurons i, j. Hence, it has been proposed as biologically plausible34 and also plausible in physical systems9,14. However, a learning rule of this kind that compares two different states raises some challenges. Experiencing the two states and updating weights in sequence, i.e., \(\Delta {w}_{ij}=-\epsilon {s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{free}}}}}\), followed by \(\Delta {w}_{ij}=\epsilon {s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{clamped}}}}}\), will require a very small learning rate ϵ to avoid convergence problems since the difference \({s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{clamped}}}}}-{s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{free}}}}}\) can be much smaller than either of the two terms35. Further, this approach requires globally switching the system between Hebbian and anti-Hebbian learning rules. One natural option then is to store information about the free state synaptic currents \({s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{free}}}}}\) locally at each synapse during the free state - without making any weight updates - and then store information about the clamped state currents \({s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{clamped}}}}}\), again without making any weight updates, and then after a cycle of such states, update weights based on Eq. (1) using on the stored information. While this approach is natural when implementing such training on a computer, it imposes multiple requirements on the physical or biological system: (1) local memory units at each synapse that stores information about \({s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{free}}}}},{s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{clamped}}}}}\) before wij are updated, (2) a global signal informing the system whether the current state corresponds to free or clamped state (since the corresponding sij must be stored with signs, given the form of Eq. (1)). These requirements can limit the relevance of contrastive training to natural physical and biological systems, even if they can naturally update parameters through Hebbian-like rules5,8,11,13,23.

Results

Temporal Contrastive learning using implicit memory

We investigate an alternative model of implicit non-equilibrium memory, Temporal Contrastive Learning (TCL) in a synapse (or any equivalent physical learning degree of freedom5). In our model, clamped or free states information is not stored anywhere explicitly; instead, non-equilibrium dynamics at each synapse results in changes to wij that are based on the difference between past and present states.

Consider a neural network driven to experiencing a temporal sequence of inputs (e.g., smoothly interpolating between free and clamped states according to a periodic temporal protocol) which induces a synaptic current sij(t) at synapse ij. For example, the Hebbian rule (‘fire together, wire together’) is based on a signal sij(t) = ηi(t)ηj(t) where ηi is the firing rate of neuron i36,37. The conventional Hebbian rule assumes an instantaneous update of weights with the current value of the synaptic signal,

where g is a system-dependent non-linear function36.

In contrast, we consider updates based on an implicit memory of recent history sij(t), with the memory encoded by convolution with a kernel \(K(t-{t}^{{\prime} })\). This kernel convolution arises through the underlying physical dynamics in diverse physical and biological systems to be discussed later; in this approach, there is no explicit storage of the value of the signal sij(t) at each point in time in specialized memory.

The memory kernel, together with the past signal, characterizes the response of each synapse to the history of signal values:

where the nonlinearity g may be system-dependent.

While most physical and biological systems have some form of memory, the most common memory is described by monotonic kernels, for example \(K(t-{t}^{{\prime} }) \sim {e}^{-(t-{t}^{{\prime} })/{\tau }_{K}}\). But a broad class of non-equilibrium systems exhibit memory with a non-monotonic kernel with both positive and negative lobes, for example \(K(t-{t}^{{\prime} }) \sim {e}^{-(t-{t}^{{\prime} })/{\tau }_{K}}f(t-{t}^{{\prime} })\), with \(f(t-{t}^{{\prime} })\) a polynomial31,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. Such kernels arise naturally in numerous physical systems, the prototypical example being integral feedback29 in analog circuits.

A key intuition for considering such an update rule can be seen in the response of the system to a step-function signal; when convolved with a non-monotonic kernel, the constant parts of the signal produce a vanishing output. However, at the transition from one signal value to another, the convolution produces a jump with a timescale inherent to the kernel (Fig. 2B). As such, the convolution in effect produces the finite-time derivative of the original signal.

A We consider a network whose weights wij are updated by a history of the synaptic current sij(t), i.e., by \({u}_{ij}(t)=\int_{-\infty }^{t}K(t-{t}^{{\prime} }){s}_{ij}({t}^{{\prime} })d{t}^{{\prime} }\) with a non-monotonic kernel K of timescale τK as shown. g(u) is a non-linear function of the type in Eq. (5). B Response of uij to a step change in sij shows that uij effectively computes a finite-timescale derivative of sij(t); uij responds to fast changes in sij but is insensitive to slow or constant values of sij(t). C Training protocol: Free and clamped states are seen in sequence, with the free state rapidly followed by the clamped state (fast timescale τf) and clamped boundary conditions slowly relaxing back to free (slow timescale τs). The rapid rise results in a large uij(t) whose integral reflects the desired contrastive signal; but the slow fall results in a small uij(t) whose impact on wij is negligible, given the nonlinearity g(uij(t)). Thus, over one sawtooth period, weights updates Δwij are proportional to the contrastive signal \({s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{clamped}}}}}-{s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{free}}}}}\).

Finally, g(u) in Eq. (4) can represent any non-linearity that suppresses small inputs u relative to larger u, e.g.,

This non-linearity allows for differentiation between fast and slow changes in synaptic signal.

The weight update of the system described thus far does not change in time, e.g., between clamped and free states; synapses are always updated with the same fixed local learning rule in Eq. (4).

The only time-dependence comes from training examples being presented in a time-dependent way. For simplicity, we consider a sawtooth-like training protocol, where input and output neurons ηi(t) alternate between free and clamped states over time (Fig. 2C). In this sawtooth protocol, the free-to-clamped change is fast (time τf) while the clamped-to-free relaxation is slow (time τs > τf); see Section S1 for further detail.

Such a time-dependent sawtooth presentation of training examples ηi(t) induces a sawtooth synaptic signal sij(t). We can compute the resulting change in weights Δwij, which is Eq. (4) integrated over one cycle of the sawtooth, assuming slow weight updates:

with ϵ a learning rate. As shown in Section S1, in the specific limit of protocols with τK ≪ τf ≪ τs:

Intuitively, the kernel K computes the approximate (finite) time derivative of sij(t); this is what requires the kernel timescale τK ≪ τf (Fig. S1). The rapid rise of the sawtooth from free to clamped states results in a large derivative that exceeds the threshold θg in g(u) and provides the necessary contrastive learning update. The slow relaxation from clamped to free has a small time-derivative that is below θg. The ability to distinguish free-to-clamped versus clamped-to-free transitions requires τf ≪ τs as shown in Section S1.

Consequently, the fast-slow sawtooth protocol allows systems with non-equilibrium memory kernels to naturally learn through contrastive rules by comparing free and clamped states over time. Note that our model here does not include an explicit memory module that stores the free and clamped state configurations but rather exploits the memory implicit in local feedback dynamics at each synapse.

Related work summary

Several works have proposed ways in which contrastive learning can be generated in natural and engineered systems, such as: utilizing explicit memory27,28; having two globally coordinated phases each with low learning rates46; having two copies of the system47,48,49; having two physically distinct kinds of signals15; or using continually-running oscillations in the learning rules16,24. All these methods require globally switching the system between two phases or exploit hardware-specific mechanisms. The closest to the TCL approach here is ‘continual EP’50, but it also requires globally switching between phases of learning. See Section S2 for a more in-depth review of these related works.

Our rule superficially resembles spike-timing dependent plasticity (STDP)42,51,52, in particular how our TCL weight update has a representation involving a non-monotonic kernel K. While STDP-inspired rules53,54,55 and other rules involving competing Hebbian updates with inhibitory neurons56,57 have shown great promise as local learning paradigms, they are adapted to settings where synapses are asymmetric and can distinguish differentials between the timings of pre- and post-synaptic neuronal activations. Our rule only involves signals at the same moment in time t and can only result in symmetric interactions wij. We are not aware of any direct relationship between work on STDP rules and the proposal here; see Section S2 for further detail.

Performance on MNIST

By coupling together a network of synapses with non-equilibrium memory kernels, we were able to train a neural network capable of classifying MNIST. In particular, we adapted the Equilibrium Propagation (EP) algorithm26, a contrastive learning-based method that ‘nudges’ the system’s state towards the desired state, rather than clamping it as is done in standard contrastive Hebbian learning (CHL)22. We used EP instead of CHL due to its better properties and its superior performance in practice58,59. EP makes weight updates of the form:

Normally the EP method requires storing the states \({s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{nudge}}}}}\) and \({s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{free}}}}}\) in memory, computing the difference and then updating weights wij; our proposed TCL method will accomplish the above EP weight update, without explicitly storing and retrieving those states.

In order to process MNIST digits, we utilize a network architecture with three types of symmetrically-coupled nodes. Each node carries internal state x and activation η = clip(x, 0, 1). Nodes belong either to a 784-node input layer (indexed by i), a 500-node hidden layer (indexed by h), or a 10-node output layer (indexed by o). Nodes are connected by synapses only between adjacent layers (i and h, h and o), with no skip- or lateral-layer couplings. The neural network dynamics minimize the energy:

where bn is the bias of node n, wnm is the weight of the synapse connecting nodes n and m, and the indices n, m run over the node indices of all layers i, h, o.

We represent each 784-pixel grayscale MNIST image as a vector \({v}^{{{{\rm{image}}}}}={\{{v}_{i}^{{{{\rm{image}}}}}\}}_{i=0,\ldots,783}\). For each MNIST digit vimage, we hold the states of the 784 input nodes at constant values over time, \({x}_{i}(t)={v}_{i}^{{{{\rm{image}}}}}\). For inference, we allow the hidden- and output-layer activations to adjust in response to the fixed input nodes, minimizing Eq. (9). Once a steady-state is reached, the network prediction is given by looking at the states of the 10 output nodes, \({\{{x}_{o}\}}_{o=0,\ldots,9}\), and interpreting the index of the maximally activated output node as the input image label.

During inference, the network minimizes an energy function which does not vary in time, subject to the constraint that \({x}_{i}(t)={v}_{i}^{{{{\rm{image}}}}}\). During training, the same constraint \({x}_{i}(t)={v}_{i}^{{{{\rm{image}}}}}\) applies, but our network instead is subjected to a time-varying energy function:

Here, vlabel is the one-hot encoding vector for the corresponding label of the MNIST digit. The time-dependent training protocol β(t) is the asymmetric sawtooth function which smoothly interpolates between 0 and a maximal value βmax < 1. One portion of the sawtooth is characterized by the fast timescale τf, and the other portion by the slow timescale τs. We assume that both these timescales are quasi-static compared to any system-internal energy relaxation timescales60. This restriction to adiabatic protocols is a potential limitation to contrastive methods in general; details depend on the system and some works present viable workarounds25,61.

Each time the training protocol β(t) completes a cycle, the network weights are updated according to Eq. (6), with ηnηm as the necessary synaptic current snm. After completing multiple sawtooth cycles, we switch the inputs xi to a new MNIST image and repeat the training process of manipulating the xo through the time-varying energy function F(x; t). See Section S4 for further detail, including specifications of K and g for Eq. (6).

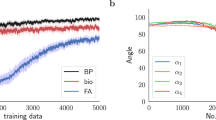

We find that, after training for 35 epochs, our classification error drops to 0, and we achieve an accuracy of 95% on our holdout test dataset (Fig. 3B). Our results demonstrate the feasibility of performing contrastive learning in neural networks without requiring explicit memory storage, but leave open the question of limitations on our approach. We consider performance limitations at the level of a single synapse in the following sections.

A We train a neural network with three types of neurons: input, hidden, and output. During training time, neurons in the input layer are set to internal states xi based on input MNIST digits (gray curves). But output neuron states xo are modulated between being nudged to the desired output (i.e., correct image label) and being free in a sawtooth-like protocol (red curves). Synaptic weights are updated using a memory kernel with timescale τK = . 1; length of one free-clamped cycle τf + τs = 1, τf = . 1. See Section S4 for protocol details. B Average train classification error as a function of epochs of training (gray curve). Each epoch involves a pass through the 10000 MNIST entries in the training set, where for each MNIST entry, network weights are updated based on a single cycle of the sawtooth protocol. Test error (dashed black curve) is computed on 2000 entries in a test set.

Speed-accuracy tradeoff

The learning model proposed here relies on breaking the symmetry between free and clamped using timescales in a sawtooth protocol (Fig. 2C). The expectation is that our proposal for approximating the difference between free and clamped states works best when this symmetry-breaking is large; i.e. in the limit of slow protocols.

We systematically investigated such speed-accuracy trade-offs inherent to the temporal strategy proposed here. First, we fix synaptic parameters θg, τK and protocol parameters (τs, τf) and consider protocols of varying amplitude A = sclamped − sfree (Fig. 4A). The protocol we use can be written in the form:

with \(\overline{{s}_{ij}}\) the average of the clamped and free states. We fix the kernel K to be of the form \(K(t-{t}^{{\prime} }) \sim {e}^{-(t-{t}^{{\prime} })/{\tau }_{K}}f(t-{t}^{{\prime} })\), with the exact expression for the polynomial f given in Section S5.

A The sawtooth training protocol sij(t) with amplitude A approximates contrastive learning in specific regimes of protocol timescales (τs, τf) relative to nonlinearity threshold θg and synaptic memory kernel timescale τK. B The weight update Δwij is proportional to the signal amplitude sclamped − sfree as desired within a range of amplitudes (regime ii) for given timescales. C Learning range (defined in (B) as the dynamic range Amax/Amin for which the sawtooth protocol approximates contrastive Hebbian learning) plotted against τs/τf. Signal timescales (τs, τf) place a limit on maximal learning range which increases with increasing τs/τf. Protocols with higher τf/τK approach this limit.

We compute Δwij for these protocols and plot against amplitude A in Fig. 4B. A line with zero intercept and slope 1 indicates a perfect contrastive Hebbian update. We see that the contrastive Hebbian update is approximated for a regime of amplitudes Amin < A < Amax, where Amin, Amax are set by the requirement that θg separates the rate of change in the fast and slow sections of the protocol (Fig. 4B).

We determined this dynamic range Amax/Amin for protocols of different timescales τs, τf, keeping the kernel fixed but always choosing a threshold θg which provides an optimal dynamic range for the synapse output, given a maximal amplitude magnitude (see Section S1). Choosing θg this way, we find the following trade-off equation,

that is, the slower the speed of the down ramp, the larger the range of amplitudes over which contrastive learning is approximated (Fig. 4C).

Finally, we also need τK ≪ τf; intuitively, the kernel \(K(t-{t}^{{\prime} })\) is a derivative operator but on a finite timescale τK; thus the fast ramp must last longer than this timescale so that uij(t) can reflect the derivative of sij(t). As τf → τK, the contrastive Hebbian approximation breaks down (see Section S1). By setting τf/τK to be just large enough to capture the derivative of sij(t), we find that the central trade-off to be made is between having a longer τs and a larger dynamic range Amax/Amin (Fig. 4C).

Energy dissipation cost of non-equilibrium learning

Our mechanism is fundamentally predicated on memory as encoded by the non-monotonic kernel \(K(t-{t}^{{\prime} })\). At a fundamental level, such memory can be linked to non-equilibrium dynamics to provide a Landauer-like principle for learning31,62. Briefly, we will show here that learning accuracy is reduced if the kernel has non-zero area \(I=\int_{0}^{\infty }K(t)dt\); we then show, based on prior work31,63, that reducing the area of kernels to zero requires increasingly large amounts of energy dissipation. In other words, to perform increasingly accurate inference, systems need to consume more energy (e.g. electrical energy in neuromorphic systems, ATP or other chemical fuel in molecular systems), which is then dissipated as heat.

We first consider the problem at the phenomenological level of kernels K with non-zero integrated area \(I=\int_{0}^{\infty }K(t)dt\) (Fig. 5A, Section S6). In the limit of small I and τK, and large τs, the weight update Δw to a synapse experiencing a current sij(t) reduces to:

where τf is the fast timescale of the protocol. See Section S6 for further detail. Hence, the response of the synapse with a non-zero area deviates from the ideal contrastive update rule by the addition of an offset proportional to the average signal value (Fig. 5B).

A Memory kernels with nonzero area (\(I=\int_{0}^{\infty }Kdt\)) are sensitive to the time-average synaptic current \(\overline{{s}_{ij}}\). B For protocols with kernels with nonzero area, Δwij is no longer proportional to sclamped − sfree within the range of performance but instead has a constant offset. Offset is the y-intercept of the line of best fit for the linear portion of the weight update curve. C Offset from contrastive learning (defined in (B)) for protocols of varying τf, τs, evaluated for a fixed memory kernel of timescale τK and non-zero area. Offset is positively correlated with τf, with overall longer protocols (high τf + τs) offset the most. Here the average signal value \(\overline{{s}_{ij}}\) = 25; offset is normalized by \(\overline{{s}_{ij}}\).

Indeed, when we fix integrated kernel area and mean signal value, we find that increasing protocol lengths (both τf and τs, due to finite τK) result in a larger offset, and hence further deviations from the ideal contrastive update (Fig. 5C). This constraint is in contrast to the metric used for assessing performance of kernels with zero integrated area, where we found that longer protocols enabled learning over a wider dynamic range of amplitudes. This result suggests that optimal protocols will be set through a balance between the desire to minimize the offset created by non-zero kernel area, and the desire to maximize the dynamic range of feasible contrastive learning.

We now relate the kernel area to learning accuracy to provide a Landauer-like62 relationship between energy dissipation and contrastive learning. To understand this fundamental energy requirement, we consider a microscopic model of reversible non-equilibrium feedback. Such models have been previously studied to understand the fundamental energy cost of molecular signal processing during bacterial chemotaxis31,64. In brief, non-monotonic memory kernels K require breaking detailed balance and thus dissipation; further, reducing the area I to zero requires increasingly large amounts of dissipation.

As shown in Refs. 31,64, the simplest way to model a non-monotonic kernel with a fully reversible non-equilibrium statistical model is to use a Markov chain shaped like a ladder network (Section S8, Fig. S2). The dynamics of the Markov chain are governed by the master equation:

Here rab are the rate constants for transitions from state a to b, and pa is the occupancy of state a. We consider a simple Markov chain network arranged as a grid with two rows (see Fig. 6A for a schematic, and Section S8 for the fully specified network). The dynamics of the network are mainly controlled by two parameters: sij and γ. As in Ref. 64, the rates (\({r}_{up}^{i},{r}_{down}^{i}\)) on the vertical (red) transitions are driven by synaptic current sij. These rates vary based on horizontal position such that circulation along vertical edges is an increasing function of sij; see Section S8 for the functional form of this coupling. Quick changes in sij shift the occupancy \(\overrightarrow{p}\), which then settles back into a steady state. Thus through sij the network is perturbed by an external signal. On the other hand, the parameter γ controls the intrinsic circulation within the network by controlling the ratio of clockwise (rcw) to counterclockwise (rccw) horizontal transition rates:

Then uij is taken to be the occupancies ∑ipi over all nodes i along one rail of the ladder (Fig. 6A). The parameter γ is particularly key in quantifying the breaking of detailed balance. When γ → 0, i.e., when this network is driven out of equilibrium, the microscopic dynamics of this Markov chain model provide a memory kernel K suited for contrastive learning. In particular, the response of the Markov chain to a small step function perturbation in sij (i.e., to vertical rate constants) results in \({u}_{ij}(t)=\int_{-\infty }^{t}K(t-{t}^{{\prime} }){s}_{ij}({t}^{{\prime} })d{t}^{{\prime} }\) with a memory kernel \(K(t-{t}^{{\prime} })\) much as needed for Fig. 2B. The form of K can then be extracted from uij by taking its derivative and normalizing.

A A thermodynamically reversible Markov state model of physical systems with non-monotonic kernel K. Nodes represent states connected by transitions with rate constants as shown; the ratio of rate constants \({r}_{up}^{m}\) and \({r}_{down}^{m}\) is set by synaptic current sij(t) (the input). The output uij is defined as the resulting total occupancy of purple states; uij is used to update weight wij. g is a threshold nonlinearity as in Fig. 4A. The ratio of products of clockwise to counterclockwise rate constants, γ, quantifies detailed balance breaking and determines energy dissipation σ. B Energy dissipation σ versus error in contrastive learning rule for different choices of rate constants in (A). Error of contrastive learning is quantified by the normalized offset from ideal contrastive weight update; Δwij is the weight update \(\int_{0}^{t}\,g(u({t}^{{\prime} }))d{t}^{{\prime} }\), A is the signal amplitude \({s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{clamped}}}}}-{s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{free}}}}}\), and \(\bar{{s}_{ij}}\) is the average signal value \(({s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{clamped}}}}}+{s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{free}}}}})/2\) for a sawtooth signal (see Fig. 5B). Bounded region indicates greater dissipation is required for lower offset and better contrastive learning performance.

In the Markov chain context, we can rigorously compute energy dissipation \(\sigma={\sum }_{i\ > \ j}({r}_{ij}{p}_{j}-{r}_{ji}{p}_{i})\ln (\frac{{r}_{ij}{p}_{j}}{{r}_{ji}{p}_{i}})\).

For the particular ladder network studied here, dissipation takes the following form (in units of kT):

where σv is dissipation along vertical connections, and the node occupations pi (excluding corners, which are accounted for by σv) are indexed in counterclockwise order. The dissipation is a decreasing function of γ ∈ [0, 1]. This dissipation (at steady state), is zero if γ = 1 (i.e., detailed balance is preserved) and non-zero otherwise. Markov chains with no dissipation produce monotonic memory kernels which do not capture the finite time derivative of the signal.

However, for a finite amount of non-equilibrium drive γ, the generated kernel will generally have both a positive and negative lobe and have lower but non-zero integrated area I, leading to imperfect implementation of the contrastive learning rule, offset as a result of non-zero area. Larger dissipation of the underlying Markov chain, e.g., by decreasing γ → 0, will lower the learning offset and cause the kernel convolution to approach an exact finite time derivative. Figure 6B shows the increased dissipation required to reach lower offset.

In summary, Landauer’s principle62 relates the fundamental energy cost of computation to the erasure of information inherent in most computations. Our work here provides a similar rational for why a physical system learning from the environment must similarly dissipate energy - contrastive learning fundamentally requires comparing states seen across time. Hence such learning necessarily requires temporarily storing information about those states and erasing that information upon making weight updates. While the actual energy dissipation can vary depending on implementation details in a real system, our kernel-based memory model allows for calculating this dissipation cost associated with learning in a reversible statistical physics model.

Realizing memory kernels through integral feedback

We have established that contrastive learning can arise naturally as a consequence of non-equilibrium memory as captured by a non-monotonic memory kernel K. Here, we argue that the needed memory kernels K in turn arise naturally as a consequence of integral feedback control in a wide class of physical systems. Hence many simple physical and biological systems can be easily modified and manipulated to undergo contrastive learning.

Integral feedback control30,65,66,67 is a broad homeostatic mechanism that adjusts the output of a system based on measuring the integral of error (i.e., deviation from a fixed point). For example, consider a variable u that must be held fixed at a set point u0 despite perturbations from a signal s. Integral feedback achieves such control by up- or down-regulating u based on the integrated error signal u − u0 over time,

Here, we rely on a well-known failing of this mechanism30,31 - if s(t) changes rapidly (e.g., a step function), the integral feedback will take a time τK to restore homeostasis; in this time, u(t) will rise transiently and then fall back to u0 as shown in Fig. 2B. The general solution of Eqs. (17), (18) is of the form of a driven damped oscillator driven by the time derivative of s(t)29,30. The kernel K(t) can be written as the solution for forcing s(t) = δ(t). In the overdamped regime kτu ≪ τm, the kernel is of the form \(K(t)={e}^{-bt}\left(\,{\mbox{cosh}}(\omega t)-\frac{b}{\omega }{\mbox{sinh}}\,(\omega t)\right)\Theta (t)\), where \(b=\frac{1}{2{\tau }_{u}},\,\omega=\sqrt{\frac{k}{{\tau }_{u}{\tau }_{m}}-\frac{1}{4{\tau }_{u}^{2}}}\), Θ is a unit step function, and we have chosen u0 = 0. This form of K(t) is a non-monotonic function with both a positive and negative lobe, which returns to the set point u0 = 0 after a perturbation. Hence simple integral feedback can create memory kernels of the type required by this work. We propose a large class of physical systems capable of Hebbian learning can be promoted to contrastive learning by a layer of integral feedback as shown Fig. 7A.

A Synaptic current sij in synapse ij impacts a variable uij(t) which is under integral feedback control. That is, the deviation of uij(t) from a setpoint u0 is integrated over time and fed back to uij, causing uij(t) to return to u0 after transient perturbations due changes in sij(t). We can achieve contrastive learning by updating synaptic weights wij using uij(t), as opposed to Hebbian learning by updating wij based on sij(t). B Mechanical or vascular networks can undergo Hebbian learning if flow or strain produce molecular species (blue hexagon uij) that drive downstream processes that modify radii or stiffnesses of network edges. But if those blue molecules are negatively autoregulated (through the green species as shown), these networks can achieve contrastive learning. C Molecular interaction networks can undergo Hebbian learning if the concentrations of dimers sij, formed through mass-action kinetics, drives expression of linker molecules lij (here, purple-green rectangles) that mediate binding interactions between monomers i, j. But if transcriptionally active dimers uij additionally stimulate regulatory molecules (black circle) which inhibit uij, then levels of linker molecules lij will provide interactions learned through contrastive rules. D Stresses in networks of viscoelastic mechanical elements (dashpots connected in series to springs) reflect the time-derivatives of strains due to relaxation in dashpots. These stresses can be used to generate contrastive updates of spring stiffnesses. E Nanofluidic memristor networks can undergo Hebbian updates by changing memristor conductance in response to current flow. However, if capacitors are added as shown, voltage changes sij across a memristor results in a transient current uij; conductance changes due to these currents uij result in contrastive learning.

Learning in mechano-chemical systems

Numerous examples of biological networks release chemical signals in response to mechanical deformations sij; e.g., due to shear flow forces in Physarum polycephalum68,69,70 or strain in cytoskeletal networks71,72. If the chemical signals then locally modify the elastic moduli or conductances of the network, these systems can be viewed as naturally undergoing Hebbian learning.

Our proposal suggests that these systems can perform contrastive learning if the chemical signal is integral feedback regulated (Fig. 7B). For example, if the molecule released by the mechanical deformation is under negative autoregulation, then that molecule’s concentration uij(t) is effectively the time derivative of the mechanical forcing of the network, \({\dot{s}}_{ij}(t)\). A simple model for negative autoregulation is:

Here, u is the level of activated molecules (e.g., phosphorylated form); we assume that phosphorylation is driven with rate ka by the strain molecule s. However, excess levels of u relative to a baseline u0 leads to build up of another molecular form m (e.g., methylated molecules in the case of chemotaxis29,73). If we assume that m then deactivates (or dephosphorylates as in chemotaxis) u with rate ki, we obtain an control loop as long as u remains above a small saturating threshold us. These dynamics provide integral feedback control over u74, and allow for computing the time-derivative of strain s.

Therefore, altering the radius in flow networks or stiffness in elastic networks based on uij(t) will now lead to contrastive learning. The same mechano-chemical principles can also be exploited in engineered systems such as DNA-coupled hydrogels75; in these systems, DNA-based molecular circuits76,77,78,79 can implement the needed integral feedback while interfacing with mechanical properties of the hydrogel. Such chemical feedback could be valuable to incorporate into a range of existing metamaterials with information processing behaviors18,80.

Learning in molecular systems

Molecular systems can learn in a Hebbian way through ‘stay together, glue together’ rules, analogous to the ‘fire together, wire together’ maxim for associative memory in neural networks6,7,8,9,10,81. In the example shown in Fig. 7C, temporal correlations between molecular species i and j would result in an increased concentration of linker molecules lij that will enhances the effective interaction between i and j. This mechanism exploits dimeric transcription factors82,83; an alternative proposal8 involves proximity-based ligation84 as used in DNA microscopy85.

We can promote these Hebbian-capable systems to contrastive learning-capable systems by including a negative feedback loop. In this scheme, monomers i,j form dimers sij ∝ cicj dictated by mass-action kinetics, as in Hebbian molecular learning6,8. We now assume that these dimers can form a transcriptionally active component uij by binding an activating signal (e.g. shown as a circle in Fig. 7C).

Here, molecular learning6,8 takes place as follows: monomers i,j form a compound dimer uij whose concentration is dictated by mass-action kinetics sij ∝ cicj; these uij drive the transcription of a linker molecule lij that mediates Hebbian-learned interactions between i and j. To achieve Temporal Contrastive Learning, we now additionally allow activated dimers uij to produce a regulating signal mij which deactivates or degrades uij during training time82,86. At test time, the resulting interaction network for monomers i,j, mediated by linker levels lij, will reflect interactions learned through contrastive rules.

This scheme can be quantitatively written as:

where ka and ki are rates of production and degradation, us is a small saturating threshold for degradation, u0 is a baseline for the production of m, and g is a transcription-related nonlinearity for the production of linkers l.

Learning in viscoelastic materials

Mechanical materials with some degree of plasticity have frequently been exploited in demonstrating how memory formation and Hebbian learning can arise in simple settings, e.g. with foams11,87, glues18, and gels88. In this setting, stress slowly softens the moduli of highly strained bonds, thereby lowering the energy of desired material configurations in response to a strain signal sij(t).

We add a simple twist to this Hebbian framework in order to make such systems capable of contrastive learning; we add a viscoelastic element with a faster timescale of relaxation compared to the timescale of bond softening. In reduced-order modeling of viscoelastic materials, a common motif is that of a viscous dashpot connected to an elastic spring in series, also known as a Maxwell material unit. Such units obey the following simple equation:

where u is the stress in the unit, s is the strain in the unit, k is the Hookean modulus of the spring and γ is the Newtonian viscosity. In this simple model, a Maxwell unit experiences integral feedback; sharp jumps in the strain sij(t) lead to stresses uij(t) across the edge which initially also jump, but then relax as the viscous dashpot relieves the stress. As such, the stress in each edge of the network naturally computes an approximate measurement of the time derivative of strain the edge experiences, \({\dot{s}}_{ij}(t)\). We can see this cleanly by solving for the case where \(s(t)=\dot{s}t\) with \(\dot{s}\) constant, in which case \(u(t)=\gamma \dot{s}(1-{e}^{-\frac{k}{\gamma }t})\), in which case \(u\propto \dot{s}\) after a relaxation time \(\frac{\gamma }{k}\).

We consider a network of such units (Fig. 7D), experiencing strains sij(t) across each edge. If the springs in this network naturally adapt their moduli kij on a slow timescale in response to the stresses they experience, they would naturally implement Hebbian learning rules. With the introduction of viscoelasticity through the dashpots, the system is now capable of contrastive updates. Note that, in contrast to the solution from idealized Eqs. (17), (18), the material moduli kij are involved both as learning degrees of freedom and as elements of the integral feedback control.

Learning in nanofluidic systems

An emerging platform for neuromorphic computing involves nanofluidic memristor networks (Fig. 7E) driven by voltage sources89,90,91,92. Each memristic element naturally displays Hebbian behavior; as voltage drops across the memristor, ions are recruited which modify the conductance of the element. In this Hebbian picture, the voltage drop across a network element plays the role of the synaptic current sij.

Here, we make a simple modification to allow for contrastive learning, where each element in the network is composed not of a single memristor but of a capacitor and memristor connected in series. If voltage drops are established across a compound capacitor memristor element, then voltage initially drives a current across the memristor. However, this initial spike in current is suppressed on the timescale of the charging capacitor. To see this, note that as in the viscoelastic system (Eq. (24)), each unit has dynamics of the form:

where here u is the current in the unit, s is the voltage across the unit, R is the resistance and C is the capacitance. For the case where \(\dot{s}\) is constant, \(u(t)=C\dot{s}(1-{e}^{-\frac{t}{RC}})\), in which case \(u(t)\propto \dot{s}\) after a relaxation time RC.

Therefore, due to the feedback control from the capacitor, the voltage that the memristor develops is \(u\approx \dot{s}\). This simple modification therefore naturally allows for nanofluidic systems which update network conductances contrastively.

Discussion

Backpropagation is a powerful way of training neural networks using GPUs. Training based on local rules – where synaptic connections are updated based on states of neighboring neurons – offer the possibility of distributed training in physical and biological systems through naturally occurring processes. However, one powerful local learning framework, contrastive learning, seemingly requires several complexities; naively, contrastive learning requires a memory of ‘free’ and ‘clamped’ states seen over time and/or requires the learning system to be globally switched between Hebbian and anti-Hebbian learning modes over time. Here, we showed that such complexities are alleviated by exploiting non-equilibrium memory implicit in the integral feedback update dynamics at each synapse that is found in many physical and biological systems.

Our Temporal Contrastive Learning approach offers several conceptual and practical advantages. In comparison to backpropagation, it provides a learning algorithm in hardware where no central processor is available. In comparison to other local learning algorithms, which may still require some digital components, our approach offers several advantages. To start, TCL does more with less. A single analog operation — Hebbian weight update based on an integral feedback-controlled synaptic current — effectively stores memory of free and clamped states, retrieves that information, computes the difference, and updates synaptic weights. No explicit memory element is needed. Further, since integral feedback occurs naturally in a range of systems29,86 and we exploit a failure mode inherent to integral feedback, our approach can be seen as an example of the non-modular ‘hardware is the software’ philosophy93 that provides more robust and compact solutions.

Our framework has several limitations quantified by speed-accuracy and speed-energy tradeoffs derived here, in addition to the general concerns about adiabatic protocols in contrastive methods25,60. The time costs in our scheme (e.g. those shown in Fig. 4) are inherently larger compared to other Equilibrium Propagation-like methods which use explicit memory and global signals to switch between wake and sleep, thereby avoiding slow ramping protocols. Slower training protocols in systems with higher energy dissipation lead to better approximations of true gradient descent on the loss function. However, we note that not performing true gradient descent is known to provide inductive biases with generalization benefits in other contexts94,95; we leave such an exploration to future work.

Darwinian evolution is the most powerful framework we know that drives matter to acquire function by experiencing examples of such function over its history96; however, Darwinian evolution requires self-replication. Recent years have explored ‘physical learning’5 as an alternative (albeit less powerful) way for matter to acquire functionality without self-replication. For example, in one molecular version6,7, recently realized at the nanoscale8, molecules with Hebbian-learned interactions can perform complex pattern recognition on concentrations of hundreds of molecular species, deploying different molecular self-assembly on the nanoscale. Similar Hebbian-like rules have allowed physical training of mechanical systems11,18,97 for specific functionality. This current work shows that natural physical systems can exploit more powerful learning frameworks that require both Hebbian and anti-Hebbian training13,14 by exploiting integral feedback control. Since integral feedback is relatively ubiquitous and achieved with relatively simple processes, the work raises the possibility that sophisticated non-Darwinian learning processes could be hiding in plain sight in biological systems. In this spirit, it is key to point out that other ideas for contrastive learning have been proposed recently15,16. Further, the contrastive framework is only one potential approach to learning through local rules plausible in physical systems; the feasibility of other local frameworks57,98,99 in physical systems remain to be explored.

By introducing a reversible statistical physics model for the memory needed by contrastive learning, we provided a fundamental statistical physics perspective on the dissipation cost of learning. While specific implementations will dissipate due to system-specific inefficiencies, our work points at an unavoidable reason for dissipation in the spirit of Landauer62. Our analysis of dissipation here only focuses on the contrastive aspect of contrastive learning. Developing reversible models for other aspects of the learning process, as has been done for inference and computation extensively31,62,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107, can shed light on fundamental dissipation requirements for learning in both natural and engineered realms.

Methods

Temporal Contrastive Learning weight updates

In Temporal Contrastive Learning, we update weights following Eq. (6):

with ϵ the learning rate. The temporal forcing from the synaptic current sij(t) is assumed to be an asymmetric sawtooth wave: a fast transition from the free value \({s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{free}}}}}\) to the clamped value \({s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{clamped}}}}}\) occurring over a timescale τf, and then a slow relaxation from clamped back to free over a timescale τs:

where \(A={s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{clamped}}}}}-{s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{free}}}}}\) and \(\overline{{s}_{ij}}=\frac{1}{2}({s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{clamped}}}}}+{s}_{ij}^{{{{\rm{free}}}}})\).

The nonlinearity g is 0 below a threshold magnitude θg and linear elsewhere:

The kernel K varies in exact functional form, but has a characteristic timescale τK.

We show in Section S1 that our weight update Eq. (6) approximates an ideal contrastive rule:

if the following conditions are met:

-

1.

\(I=\int_{0}^{\infty }K(t)dt=0\);

-

2.

τK ≪ τf ≪ τs.

We specify more exact numerical details of weight update computations in Section S9.

Training neural networks with Temporal Contrastive Learning

We use our Temporal Contrastive Learning framework in a neural network model for MNIST recognition. Details of the network architecture are available in Section S4. Each node of the network is described by a state x. During inference, the dynamics of the network minimizes:

where bi is the bias of node i, wij is the weight of the synapse connecting nodes i and j, and the indices i, j run over the node indices of all layers (input, hidden, and output). η(x) is an activation function clip(x, 0, 1). During training of the network, the network minimizes:

Here, \({v}_{o}^{{{{\rm{label}}}}}\) is the one-hot encoding of the desired MNIST output class, and the xo are the states of the 10 neurons in the output layer. β is a clamping parameter which varies in time as a sawtooth function.

As β varies, the synaptic current sij = η(xi)η(xj) changes as the network minimizes energy. These changes inform the updates of weights wij according to Eq. (6), with a layer-dependent nonlinearity g and a sinusoidal kernel K. Further details of training and inference protocols are provided in Section S4.

Data availability

The data generated in this study may be found in the following figshare database: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25057793.

Code availability

Code for training neural networks to perform MNIST recognition can be found at https://github.com/falkma/ContrastiveMemory-Exp. Code for understanding tradeoffs between protocol time and dissipation can be found at https://github.com/atstrupp/ContrastiveMemory-SynapseAnalysis.

References

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems25 (2012).

Grollier, J. et al. Neuromorphic spintronics. Nat. Electron. 3, 360–370 (2020).

Burr, G. W. et al. Neuromorphic computing using non-volatile memory. Adv. Phys.: X 2, 89–124 (2017).

Shastri, B. J. et al. Photonics for artificial intelligence and neuromorphic computing. Nat. Photonics 15, 102–114 (2021).

Stern, M. & Murugan, A. Learning without neurons in physical systems. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 14, 417–441 (2023).

Murugan, A., Zeravcic, Z., Brenner, M. P. & Leibler, S. Multifarious assembly mixtures: Systems allowing retrieval of diverse stored structures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 112, 54–59 (2015).

Zhong, W., Schwab, D. J. & Murugan, A. Associative pattern recognition through macro-molecular self-assembly. J. Stat. Phys. 167, 806–826 (2017).

Evans, C. G., O’Brien, J., Winfree, E. & Murugan, A. Pattern recognition in the nucleation kinetics of non-equilibrium self-assembly. Nature 625, 500–507 (2024).

Poole, W. et al. Chemical boltzmann machines. In DNA Computing and Molecular Programming: 23rd International Conference, DNA 23, Austin, TX, USA, September 24–28, 2017, Proceedings 23, 210–231 (Springer, 2017).

Poole, W., Ouldridge, T. E. & Gopalkrishnan, M. Autonomous learning of generative models with chemical reaction network ensembles. J. R. Soc. Interface 22, 20240373 (2025).

Pashine, N., Hexner, D., Liu, A. J. & Nagel, S. R. Directed aging, memory, and nature’s greed. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax4215 (2019).

Stern, M., Pinson, M. B. & Murugan, A. Continual learning of multiple memories in mechanical networks. Phys. Rev. X 10, 031044 (2020).

Stern, M., Arinze, C., Perez, L., Palmer, S. E. & Murugan, A. Supervised learning through physical changes in a mechanical system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 14843–14850 (2020).

Stern, M., Hexner, D., Rocks, J. W. & Liu, A. J. Supervised learning in physical networks: From machine learning to learning machines. Phys. Rev. X 11, 021045 (2021).

Anisetti, V. R., Scellier, B. & Schwarz, J. M. Learning by non-interfering feedback chemical signaling in physical networks. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 023024 (2023).

Anisetti, V. R., Kandala, A., Scellier, B. & Schwarz, J. Frequency propagation: multimechanism learning in nonlinear physical networks. Neural Comput. 36, 596–620 (2024).

Patil, V. P., Ho, I. & Prakash, M. Self-learning mechanical circuits. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.08711 (2023).

Arinze, C., Stern, M., Nagel, S. R. & Murugan, A. Learning to self-fold at a bifurcation. Phys. Rev. E 107, 025001 (2023).

Altman, L. E., Stern, M., Liu, A. J. & Durian, D. J. Experimental demonstration of coupled learning in elastic networks. Phys. Rev. Appl. 22, 024053 (2024).

Behera, A. K., Rao, M., Sastry, S. & Vaikuntanathan, S. Enhanced associative memory, classification, and learning with active dynamics. Phys. Rev. X 13, 041043 (2023).

Wang, Q., Wanjura, C. C. & Marquardt, F. Training coupled phase oscillators as a neuromorphic platform using equilibrium propagation. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.08579 (2024).

Movellan, J. R. Contrastive hebbian learning in the continuous hopfield model. In Connectionist models, 10–17 (Elsevier, 1991).

Xie, X. & Seung, H. S. Equivalence of backpropagation and contrastive hebbian learning in a layered network. Neural Comput. 15, 441–454 (2003).

Baldi, P. & Pineda, F. Contrastive learning and neural oscillations. Neural Comput. 3, 526–545 (1991).

Hinton, G. E. Training products of experts by minimizing contrastive divergence. Neural Comput. 14, 1771–1800 (2002).

Scellier, B. & Bengio, Y. Equilibrium propagation: Bridging the gap between energy-based models and backpropagation. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 11, 24 (2017).

Yi, S.-i, Kendall, J. D., Williams, R. S. & Kumar, S. Activity-difference training of deep neural networks using memristor crossbars. Nat. Electron. 6, 45–51 (2023).

Laydevant, J., Marković, D. & Grollier, J. Training an ising machine with equilibrium propagation. Nat. Commun. 15, 3671 (2024).

Doyle, J. C., Francis, B. A. & Tannenbaum, A. R. Feedback control theory (Courier Corporation, 2013).

Yi, T.-M., Huang, Y., Simon, M. I. & Doyle, J. Robust perfect adaptation in bacterial chemotaxis through integral feedback control. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 97, 4649–4653 (2000).

Lan, G., Sartori, P., Neumann, S., Sourjik, V. & Tu, Y. The energy–speed–accuracy trade-off in sensory adaptation. Nat. Phys. 8, 422–428 (2012).

Ackley, D. H., Hinton, G. E. & Sejnowski, T. J. A learning algorithm for boltzmann machines. Cogn. Sci. 9, 147–169 (1985).

Agoritsas, E., Catania, G., Decelle, A. & Seoane, B. Explaining the effects of non-convergent mcmc in the training of energy-based models. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 322–336 (PMLR, 2023).

Honey, C. J., Newman, E. L. & Schapiro, A. C. Switching between internal and external modes: A multiscale learning principle. Netw. Neurosci. 1, 339–356 (2017).

Behera, L., Kumar, S. & Patnaik, A. On adaptive learning rate that guarantees convergence in feedforward networks. IEEE Trans. neural Netw. 17, 1116–1125 (2006).

Gerstner, W. & Kistler, W. M. Mathematical formulations of hebbian learning. Biol. Cybern. 87, 404–415 (2002).

Löwel, S. & Singer, W. Selection of intrinsic horizontal connections in the visual cortex by correlated neuronal activity. Science 255, 209–212 (1992).

Tu, Y., Shimizu, T. S. & Berg, H. C. Modeling the chemotactic response of escherichia coli to time-varying stimuli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 105, 14855–14860 (2008).

Tu, Y. Quantitative modeling of bacterial chemotaxis: signal amplification and accurate adaptation. Annu. Rev. biophysics 42, 337–359 (2013).

Becker, N. B., Mugler, A. & Ten Wolde, P. R. Optimal prediction by cellular signaling networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 258103 (2015).

Tjalma, A. J. et al. Trade-offs between cost and information in cellular prediction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 120, e2303078120 (2023).

Xie, X. & Seung, H. S. Spike-based learning rules and stabilization of persistent neural activity. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 12, 199–205 (1999).

Rivière, M. & Meroz, Y. Plants sum and subtract stimuli over different timescales. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 120, e2306655120 (2023).

Celani, A. & Vergassola, M. Bacterial strategies for chemotaxis response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 107, 1391–1396 (2010).

Mattingly, H., Kamino, K., Machta, B. & Emonet, T. Escherichia coli chemotaxis is information limited. Nat. Phys. 17, 1426–1431 (2021).

Williams, E., Bredenberg, C. & Lajoie, G. Flexible phase dynamics for bio-plausible contrastive learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 37042–37065 (PMLR, 2023).

Dillavou, S., Stern, M., Liu, A. J. & Durian, D. J. Demonstration of decentralized physics-driven learning. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 014040 (2022).

Dillavou, S. et al. Machine learning without a processor: emergent learning in a nonlinear analog network. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2319718121 (2024).

Wycoff, J. F., Dillavou, S., Stern, M., Liu, A. J. & Durian, D. J. Desynchronous learning in a physics-driven learning network. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 144903 (2022).

Ernoult, M., Grollier, J., Querlioz, D., Bengio, Y. & Scellier, B. Equilibrium propagation with continual weight updates. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.04168 (2020).

Bi, G.-q & Poo, M.-m Synaptic modification by correlated activity: Hebb’s postulate revisited. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 139–166 (2001).

Bengio, Y., Mesnard, T., Fischer, A., Zhang, S. & Wu, Y. Stdp-compatible approximation of backpropagation in an energy-based model. Neural Comput. 29, 555–577 (2017).

Martin, E. et al. Eqspike: spike-driven equilibrium propagation for neuromorphic implementations. Iscience 24, 102222 (2021).

Burkitt, A. N., Meffin, H. & Grayden, D. B. Spike-timing-dependent plasticity: the relationship to rate-based learning for models with weight dynamics determined by a stable fixed point. Neural Comput. 16, 885–940 (2004).

Moraitis, T., Sebastian, A. & Eleftheriou, E. Optimality of short-term synaptic plasticity in modelling certain dynamic environments. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.06808 (2020).

Krotov, D. & Hopfield, J. J. Unsupervised learning by competing hidden units. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 7723–7731 (2019).

Journé, A., Rodriguez, H. G., Guo, Q. & Moraitis, T. Hebbian deep learning without feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.11883 (2022).

Scellier, B., Ernoult, M., Kendall, J. & Kumar, S. Energy-based learning algorithms for analog computing: a comparative study. Ad. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 36, 52705–52731 (2024).

Laborieux, A. & Zenke, F. Holomorphic equilibrium propagation computes exact gradients through finite size oscillations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 12950–12963 (2022).

Albash, T. & Lidar, D. A. Adiabatic quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015002 (2018).

Stern, M., Dillavou, S., Miskin, M. Z., Durian, D. J. & Liu, A. J. Physical learning beyond the quasistatic limit. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, L022037 (2022).

Bennett, C. H. Notes on landauer’s principle, reversible computation, and maxwell’s demon. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. Part B: Stud. Hist. Philos. Mod. Phys. 34, 501–510 (2003).

Tu, Y. The nonequilibrium mechanism for ultrasensitivity in a biological switch: Sensing by maxwell’s demons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 105, 11737–11741 (2008).

Murugan, A. & Vaikuntanathan, S. Topologically protected modes in non-equilibrium stochastic systems. Nat. Commun. 8, 13881 (2017).

Aoki, S. K. et al. A universal biomolecular integral feedback controller for robust perfect adaptation. Nature 570, 533–537 (2019).

Nemenman, I. Information theory and adaptation. Quant. Biol.: Mol. Cell. Syst. 73, 73–91 (2012).

Shimizu, T. S., Tu, Y. & Berg, H. C. A modular gradient-sensing network for chemotaxis in escherichia coli revealed by responses to time-varying stimuli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 6, 382 (2010).

Marbach, S., Ziethen, N., Bastin, L., Bäuerle, F. K. & Alim, K. Vein fate determined by flow-based but time-delayed integration of network architecture. Elife 12, e78100 (2023).

Kramar, M. & Alim, K. Encoding memory in tube diameter hierarchy of living flow network. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2007815118 (2021).

Alim, K., Andrew, N., Pringle, A. & Brenner, M. P. Mechanism of signal propagation in physarum polycephalum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 114, 5136–5141 (2017).

Cavanaugh, K. E., Staddon, M. F., Munro, E., Banerjee, S. & Gardel, M. L. Rhoa mediates epithelial cell shape changes via mechanosensitive endocytosis. Dev. Cell 52, 152–166 (2020).

Cavanaugh, K. E., Staddon, M. F., Banerjee, S. & Gardel, M. L. Adaptive viscoelasticity of epithelial cell junctions: from models to methods. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 63, 86–94 (2020).

Barkai, N. & Leibler, S. Robustness in simple biochemical networks. Nature 387, 913–917 (1997).

Qian, Y. & Del Vecchio, D. Realizing ‘integral control’ in living cells: how to overcome leaky integration due to dilution? J. R. Soc. Interface 15, 20170902 (2018).

Cangialosi, A. et al. Dna sequence–directed shape change of photopatterned hydrogels via high-degree swelling. Science 357, 1126–1130 (2017).

Scalise, D. & Schulman, R. Controlling matter at the molecular scale with dna circuits. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 21, 469–493 (2019).

Schaffter, S. W. & Schulman, R. Building in vitro transcriptional regulatory networks by successively integrating multiple functional circuit modules. Nat. Chem. 11, 829–838 (2019).

Fern, J. et al. Dna strand-displacement timer circuits. ACS Synth. Biol. 6, 190–193 (2017).

Fern, J. & Schulman, R. Design and characterization of dna strand-displacement circuits in serum-supplemented cell medium. ACS Synth. Biol. 6, 1774–1783 (2017).

Kwakernaak, L. J. & van Hecke, M. Counting and sequential information processing in mechanical metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 268204 (2023).

Owen, J. A., Osmanović, D. & Mirny, L. Design principles of 3d epigenetic memory systems. Science 382, eadg3053 (2023).

Zhu, R., del Rio-Salgado, J. M., Garcia-Ojalvo, J. & Elowitz, M. B. Synthetic multistability in mammalian cells. Science 375, eabg9765 (2022).

Parres-Gold, J., Levine, M., Emert, B., Stuart, A. & Elowitz, M. Principles of computation by competitive protein dimerization networks. bioRxiv 2023–10 (2023).

Moerman, P. G., Fang, H., Videbæk, T. E., Rogers, W. B. & Schulman, R. A simple method to alter the binding specificity of DNA-coated colloids that crystallize. Soft Matter 19, 8779–8789 (2023).

Weinstein, J. A., Regev, A. & Zhang, F. Dna microscopy: optics-free spatio-genetic imaging by a stand-alone chemical reaction. Cell 178, 229–241 (2019).

Alon, U.An introduction to systems biology: design principles of biological circuits (CRC press, 2019).

Hexner, D., Pashine, N., Liu, A. J. & Nagel, S. R. Effect of directed aging on nonlinear elasticity and memory formation in a material. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 043231 (2020).

Scheff, D. R. et al. Actin filament alignment causes mechanical hysteresis in cross-linked networks. Soft Matter 17, 5499–5507 (2021).

Robin, P., Kavokine, N. & Bocquet, L. Modeling of emergent memory and voltage spiking in ionic transport through angstrom-scale slits. Science 373, 687–691 (2021).

Robin, P. et al. Long-term memory and synapse-like dynamics in two-dimensional nanofluidic channels. Science 379, 161–167 (2023).

Xiong, T. et al. Neuromorphic functions with a polyelectrolyte-confined fluidic memristor. Science 379, 156–161 (2023).

Kamsma, T., Boon, W., ter Rele, T., Spitoni, C. & van Roij, R. Iontronic neuromorphic signaling with conical microfluidic memristors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 268401 (2023).

Laydevant, J., Wright, L. G., Wang, T. & McMahon, P. L. The hardware is the software. Neuron (2023).

Hardt, M., Recht, B. & Singer, Y. Train faster, generalize better: Stability of stochastic gradient descent. In International conference on machine learning, 1225–1234 (PMLR, 2016).

Feng, Y. & Tu, Y. The inverse variance–flatness relation in stochastic gradient descent is critical for finding flat minima. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2015617118 (2021).

Watson, R. A. & Szathmáry, E. How can evolution learn? Trends Ecol. evolution 31, 147–157 (2016).

Falk, M. J. et al. Learning to learn by using nonequilibrium training protocols for adaptable materials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 120, e2219558120 (2023).

Hinton, G. The forward-forward algorithm: Some preliminary investigations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.13345 (2022).

Lopez-Pastor, V. & Marquardt, F. Self-learning machines based on hamiltonian echo backpropagation. Phys. Rev. X 13, 031020 (2023).

Ouldridge, T. E., Govern, C. C. & ten Wolde, P. R. Thermodynamics of computational copying in biochemical systems. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021004 (2017).

Lang, A. H., Fisher, C. K., Mora, T. & Mehta, P. Thermodynamics of statistical inference by cells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 148103 (2014).

Murugan, A., Huse, D. A. & Leibler, S. Discriminatory proofreading regimes in nonequilibrium systems. Phys. Rev. X 4, 021016 (2014).

Ehrich, J., Still, S. & Sivak, D. A. Energetic cost of feedback control. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 023080 (2023).

Still, S., Sivak, D. A., Bell, A. J. & Crooks, G. E. Thermodynamics of prediction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 120604 (2012).

Bryant, S. J. & Machta, B. B. Physical constraints in intracellular signaling: the cost of sending a bit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 068401 (2023).

McGrath, T., Jones, N. S., Ten Wolde, P. R. & Ouldridge, T. E. Biochemical machines for the interconversion of mutual information and work. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 028101 (2017).

ten Wolde, P. R., Becker, N. B., Ouldridge, T. E. & Mugler, A. Fundamental limits to cellular sensing. J. Stat. Phys. 162, 1395–1424 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lauren Altman, Marjolein Dijkstra, Sam Dillavou, Douglas Durian, Andrea Liu, Marc Miskin, Krishna Shrinivas, Menachem Stern, and Erik Winfree for discussion. AM acknowledges support from the NSF through DMR-2239801 and by NIGMS of the NIH under award number R35GM151211. MJF is supported by the Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellowship, a Schmidt Sciences program. This work was supported by the NSF Center for Living Systems (NSF grant no. 2317138) and by the University of Chicago’s Research Computing Center. This work was performed in part at the Aspen Center for Physics, which is supported by National Science Foundation grant PHY-2210452.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MJF, AM, ATS conceived the study, developed methodology, and wrote the original draft. MJF, ATS developed software and performed investigation. MJF, BS, ATS provided formal analysis. MJF, AM supervised and acquired funding. All authors contributed to review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Timoleon Moraitis, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Falk, M.J., Strupp, A.T., Scellier, B. et al. Temporal Contrastive Learning through implicit non-equilibrium memory. Nat Commun 16, 2163 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57043-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57043-x

This article is cited by

-

Quantum equilibrium propagation for efficient training of quantum systems based on Onsager reciprocity

Nature Communications (2025)