Abstract

Classic cadherins, specifically E-cadherin in most epithelial cells, are transmembrane adhesion receptors, whose intracellular region interacts with proteins, termed catenins, forming the cadherin-catenin complex (CCC). The cadherin ectodomain generates 2D adhesive clusters (E-clusters) through cooperative trans and cis interactions, while catenins anchor the E-clusters to the actin cytoskeleton. How these two types of interactions are coordinated in the formation of specialized cell-cell adhesions, adherens junctions (AJ), remains unclear. Here, we focus on the role of the actin-binding domain of α-catenin (αABD) by showing that the interaction of the αABD with actin generates actin-bound linear CCC oligomers (CCC/actin strands) incorporating up to six CCCs. This actin-driven CCC oligomerization, which is cadherin ectodomain independent, preferentially occurs along the actin cortex enriched with key basolateral proteins, myosin-1c, scribble, and DLG1. In cell-cell contacts, the CCC/actin strands integrate with the E-clusters giving rise to the composite oligomers, E/actin clusters. Targeted inactivation of strand formation by point mutations emphasizes the importance of this oligomerization process for blocking intercellular protrusive membrane activity and for coupling AJs with the actomyosin-derived tensional forces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adherens Junctions (AJs), evolutionarily the oldest type of cell-cell adhesions, establish strong but flexible contacts between cells1,2,3,4,5. This remarkable property that allows cells to stay connected during tissue morphogenesis is based on continuous disassembly and reassembly of numerous actin-bound adhesion clusters of classic cadherins (e.g., E-cadherin in epithelia). While the structures of cadherin adhesive (or trans) bonds in these clusters and the bonds connecting the clusters to actin filaments are known at atomic detail6,7,8,9, coordination of these two sets of interactions during cadherin cluster lifetime is far from being understood. Elucidation of cadherin clustering is critical for our understanding of the adhesion defects that are known to be associated with many human diseases10,11.

The structural unit of cadherin clusters is the cadherin-catenin complex (CCC), in which the intracellular region of cadherin interacts with two cytosolic proteins, p120-catenin and β-catenin, the latter of which interacts with the actin-binding protein, α-catenin. Cadherin clusters greatly reinforce the strength of an intrinsically weak cadherin adhesive trans bond12. The clusters can be self-assembled through cooperative trans and cis interactions of the cadherin extracellular region (ectodomain) without any contribution from cytosolic proteins6,13,14,15,16,17,18. However, the ectodomain-assembled clusters (designated as E-clusters below) are still too weak to maintain sufficient cell-cell adhesion strength19,20. The stability of E-clusters is upregulated by coupling them to the actin cytoskeleton through α-catenin that not only provides a structural framework for the clusters but also reinforces the cadherin trans bonds via coupling them to the actomyosin tensile forces3,18,21. It has also been shown that α-catenin binding to F-actin preferentially occurs in the vicinity of already bound α-catenin22,23. Such remarkable cooperative binding of α-catenin to actin was proposed to function as a complementary CCC clustering mechanism facilitating formation of E-clusters24. Whether this actin-based α-catenin clustering plays any role in AJs and if it does, how intracellular and extracellular clustering processes are coordinated remains unexplored.

A key actin-binding device of α-catenin is its C-terminal domain, termed here αABD (see Fig. 1 for detail). Cryo-EM modeling of αABD-actin interactions shows that once bound to actin, αABD also interacts with two neighboring αABD molecules, thereby forming an actin-bound linear αABD oligomer8,9,25. Combined with data obtained by point mutagenesis, this model shows that the actin-binding interface of αABD forms through an allosteric αABD rearrangement, the key feature of which is an unfolding of the αABD N-terminal helixes, H0 and H18,9,24,26. Optical trap experiments suggest a two-state catch bond model of αABD-actin interactions, according to which this αABD rearrangement is facilitated by a mechanical force that prevents refolding of H122,27,28. Taken together, structural and binding data suggest that cadherin trans dimerization results in an application of force that locks αABD in the strong actin binding state thereby activating the complementary CCC clustering pathway through actin-dependent αABD oligomerization. However, several observations made in cell culture appear inconsistent with the role of force and/or cadherin trans interactions in formation of the actin bound CCC clusters. For example, such clusters have been detected on the contact-free surface of the Drosophila cells16. Also, the actomyosin-dependent stretching of E-cadherin was observed outside of cell-cell contacts29. Furthermore, the anti-actomyosin drugs have not been shown to abolish AJs, but only to change their appearance30,31,32,33. These observations suggest that some CCC-actin bonds that facilitate CCC clustering may be formed in both an adhesion- and force-independent manner. The exact understanding the CCC-actin interactions, their role in cadherin clustering and contribution of force to this process requires new tools that directly monitor the specific actin binding states of CCC in living cells.

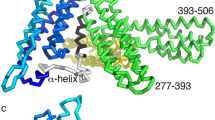

a Diagram of the α-catenin mutants used for cross-linking: GFP, N domain comprising of N1 and N2 subdomains, M domain comprising of M1, M2, and M3 subdomains, and actin-binding domain, αABD. The unstructured regions are shown as solid lines. The borders between domains are indicated by the numbers of corresponding residues. Cysteine substitutions, G805C (805), and K871C (871) are shown as yellow spheres. b Ribbon diagram of two neighboring actin-bound αABD (αABD-1 and αABD-2) according to PDB 6wvt. The cysteine substitutions are shown as in a. Note, that the G805C/K871C mutation creates an ideal pair for cross-linking. c Western blot of wt A431 cells (A431), and αCatKO-A431 cells expressing GFP-αCat (GFP-αC), GFP-αCat-C805/871 (GFP-αC805/871), and untagged αCat-C805/871 (αC805/871) probed for α-catenin (αCat) and for tubulin (tbl). Molecular weight markers (in kDa) are shown on the left. d Fluorescence microscopy of the αCatKO-A431 cells (αCatKO-A431) and the same cells stably expressing GFP-αCat and GFP-αCat-C805/871 stained for GFP (GFP, green), for F-actin (act, red), and for nuclei (DAPI, blue). The left micrographs show merged images (Scale bar, 20 μm). The representative cell-cell contact areas (in dashed boxes) are zoomed on the right (Scale bar, 10 μm). Note that αCatKO cells contact one another by numerous actin-rich protrusions, while α-catenin-expressing cells form actin-associated AJs. e Western blot of cells expressing GFP-αCat-C805/871 probed for GFP. Without cross-linking (Ctrl), the mutant migrates as a single band of ~120 kDa (M). Cross-linking (XL) results in formation of adducts (a1-a4). f A lysate of cross-linking cells (TL) was split into two parts and immunoprecipitated (IP) with E-cadherin mAb (Ecad) or without a first antibody (Ctrl). The precipitates were processed as in (e). g Cells expressing GFP-αCat-C805/871 (805/871) or its versions with a single substitution (805 or 871) were cross-linked and processed as in (e). h Cells expressing GFP-αCat-C805/871 mutant (GFP-805/871) or its untagged version (805/871) were cross-linked and analyzed as in (e) for α-catenin. Note that the difference in MW of a1 between tagged and untagged mutants is ~60 kDa, twice more that the difference (~30 kDa) between the monomers.

Here we track the Cryo-EM-determined αABD-actin interaction using a targeted cross-linking approach. Our results provide compelling evidence that this interaction generates short actin-bound CCC oligomers. Surprisingly, this actin-driven CCC oligomerization is independent of CCC oligomerization mediated by trans and cis interactions of the cadherin ectodomain, but both types of CCC oligomers appear to integrate with one another producing composite oligomers, which we refer to as E/actin clusters. Using point mutagenesis of the residue responsible for the actin-dependent αABD oligomerization, we also show that defects in this process dramatically change the overall architecture of cell-cell contacts, resulting in a general reduction in the stability of AJs, as well as in a reduction in their strength and tensional forces across the junctions.

Results

Identification of α-catenin oligomers in cells

To analyze the actin-bound CCC clusters, we applied targeted chemical cross-linking, a technique we have used previously to determine cadherin and nectin trans interactions34,35. Specifically, using a cryo-EM map of an actin-bound αABD (PDB entry 6wvt), we designed an αABD cysteine mutant, GFP-αCat-C805/871. Two cysteine substitutions in this mutant, G805C and K871C, were positioned within the H4/H5 loop and the αABD C-terminal extension, respectively (Fig. 1a, b). According to the cryo-EM map, the intramolecular distance between these residues in αABD is ~50 Å, whereas the intermolecular distance between the same residues from two adjacent actin-bound αABDs is only 9 Å (Fig. 1b). Because of this difference, the cell permeable sulfhydryl-reactive cross-linker, 1,4-bismaleimidobutane (BMB, about 10 Å in size), should preferentially cross-link adjacent actin-bound αABDs. Also, according to the cryo-EM, we do not anticipate these substitutions to critically influence the αABD-actin interactions because the mutated residues exhibit no direct contacts with F-actin. Specifically, G805, is shown to be disordered, while K871 is exposed on the surface opposite to the actin-binding interface. Furthermore, a point mutation, K871A, showed no effect on binding to F-actin24. In agreement with these observations, we detected no differences between the cell-cell contacts of A431 cells expressing the GFP-tagged intact α-catenin (GFP-αCat) or its cysteine mutant based on visual inspection or on some functional experiments (see below). The parental α-catenin-deficient A431 cells (αCatKO-A431 cells) interacted with one another using numerous filopodia-like interdigitating protrusions. Such type of interactions was not observed in cells expressing GFP-αCat or its cysteine mutant. Instead, they produced well-developed actin-associated AJs (Fig. 1c, d). Taken together, this data validates that the designed mutant is a reliable tool to study α-catenin-actin interactions. Though some minor distortions of the actin-binding interface cannot be completely ruled out without a high-resolution structure analysis, these appear to have little functional influence.

Western blotting showed that treatment of the mutant expressing cells with a low concentration of BMB (40 μM) resulted in the formation of a ladder of high molecular weight adducts (Fig. 1e) whereby the lowest adduct in the ladder (a1 in Fig. 1e) exactly matched the size of the GFP-αCat-C805/871 dimer (~240 kDa). Other major adducts, a2 and a3, and occasionally observed a4 (all higher than 350 kDa) most likely incorporated three or more cross-linked α-catenin molecules. Because CCC-free α-catenin homodimers are known to form in the cytosol and can also interact with F-actin36,37, we verified that the adducts were derived from CCC by co-precipitating CCC using an anti-E-cadherin antibody from the lysates of cross-linked GFP-αCat-C805/871-expressing cells (Fig. 1f).

To exclude the possibility that the adducts were formed by cross-linking of the α-catenin mutant to irrelevant proteins, we constructed two additional mutants, GFP-αCat-C805 and GFP-αCat-C871, which harbored only G805C or only K871C substitutions (Fig. 1a). Only barely visible α-catenin adducts could be seen after cross-linking of the cells expressing either of these two mutants (Fig. 1g). This observation confirmed that the adducts were formed through cross-linking of adjacent α-catenin molecules via new cysteines, C805 and C871. In a parallel experiment, we introduced the G805C and K871C substitutions into untagged α-catenin (αCat-C805/871). The deletion of the GFP tag decreased the molecular weight of the mutant by ~30 kDa (from ~120 kDa to 90 kDa). As expected for its dimer organization, the molecular weight of the 240 kDa adduct, a1, was decreased by 60 kDa (Fig. 1h). The sizes of other adducts also decreased by more than 30 kDa confirming that they all were α-catenin oligomers. This experiment also verified that the GFP tag had no influence on the mutant cross-linking.

Actin filaments are required for α-catenin oligomerization

We next verified that the oligomers we detected required actin filaments for their formation. It was confirmed by a strong reduction of the adducts in cells treated with latrunculin B (LnB), which prevents actin polymerization (Fig. 2a). Some amounts of adducts remaining in the treated cells were apparently derived from CCC bound to LnB-resistant filaments as had been reported38. We then employed a gentle extraction of the cells with a Triton X100-containing cytoskeleton stabilization buffer in order to verify that the adducts were primarily generated from the actin-bound pool of GFP-αCat-C805/871. This approach is a widely accepted procedure to determine proteins interacting with the cytoskeleton39,40,41. The results showed that ~50% of GFP-αCat-C805/871 remained bound to the cytoskeleton after Triton X100 extraction (Fig. 2b). Cross-linking of the parallel cultures of control and extracted cells demonstrated that about 80% of the Triton X100-resistant pool of GFP-αCat-C805/871 was converted into the adducts. Of note, the amounts of the adducts generated in control and in extracted cells were nearly identical (Fig. 2b). The almost complete conversion of the Triton X100-resistant α-catenin into adducts demonstrates a remarkable efficiency of the actin-bound GFP-αCat-C805/871 cross-linking. It also validates that Triton X100 predominantly removes the actin-uncoupled pool of α-catenin. This phenomenon allowed us to analyze the size of this actin-free pool of α-catenin in AJs using time-lapse microscopy (Fig. 2c). The results showed that a two min-long extraction decreased the GFP-αCat-C805/871 fluorescence in AJs by ~60%, while outside of AJs it dropped to nearly background levels. Collectively, this data showed that our cross-linking approach generates oligomeric adducts predominantly, if not exclusively, from the actin-bound pool of α-catenin.

a The GFP-αCat-C805/871 cells were cross-linked in standard conditions (Ctrl) and after 30 min with 1 μM Latrunculin B (LnB) and processed as in Fig. 1e.b Left: Western blot probed for GFP of total lysates of GFP-αCat-C805/871 cells from control culture (Ctrl); from parallel culture after 5 min-long extraction with 1% Triton X100 (Trt); after cross-linking of the control culture (XL); and after cross-linking of the Triton X100 extracted culture (Trt+XL). Right: Quantification (based on six independent experiments) of the intensities of the GFP-αCat-C805/871 monomer (relative to that in control culture) and the GFP-αCat-C805/871 adduct, a1 (relative to that in nonextracted culture). The means +/- SD are indicated by bars. Note that Triton X100 extraction reduced to ~50% the level of monomers in the control cells and nearly completely in the cross-linked cells. But it only negligibly changed the level of the adduct. Statistical significance was calculated using a two tailed Student’s t-test: ns, non-significant; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. c Time-lapse microscopy of GFP-αCat-C805/871 cells during Triton X100 extraction. Left: The first (before extraction) and the last (after 1.5 min in Triton X100) frames from one of the obtained representative movies. Bar, 25 μM. Right: Kinetics of the GFP-αCat-C805/871 extraction obtained for AJs and for the spots outside (n = 3 taken from the same three independent movies). Data are representative as medians +/− SD.

Actin-bound pentameric array of CCC is a major product of αABD-actin interactions

The high molecular weights of the adducts we detected had precluded the exact assessment of their sizes and, therefore, the order of α-catenin oligomerization. In addition, high molecular weight proteins may exhibit low transfer efficiency in Western blotting that hinders their detection. To gain more insight into the adduct organization, we designed an approach allowing us to reduce the adduct molecular weight by cleaving the cross-linked αABD from the rest of the α-catenin. To this end, we incorporated a thrombin cleavage site (TCS) into the linker region between αABD and the M domain by changing the sequence LIAGQS (663-668) to LVPRGS (Fig. 3a). This change had no effect on AJ appearance (Fig. 3b) or the pattern of cross-linked adducts (Fig. 3c). Control experiments with anti-GFP immunoprecipitates obtained from cells expressing the new mutant (GFP-αCatTCS-C805/871) confirmed that thrombin cleaved the αABD (Fig. 3d). We then treated the mutant-expressing cells with thrombin after cross-linking and permeabilization with Triton X100 (Fig. 3e). Western blotting with an anti-αABD antibody showed that this procedure yielded a ladder of the cross-linked αABD consisting of four major bands at ~60, ~90, ~120, and ~150 kDa. These molecular weights exactly corresponded to those of the dimers, trimers, tetramers and pentamers of αABD. As expected, the monomeric form of αABD was hardly detectable in this experiment due to its removal during Triton X100 extraction (see above). Conspicuously, there was a nearly complete absence of the oligomers of an order of 6 or greater.

a Diagram of the α-catenin mutants (depicted as in Fig. 1a) used for αABD cleaving. The thrombin cleavage site (TCS) is indicated by the red box. b Fluorescence microscopy of GFP-αCatTCS-C805/871-expressing cells imaged for GFP (GFP, green) and for F-actin (act, red). A representative contact (in a dashed box) taken from the merged image (on the left, Scale bar, 25 μm) is magnified on the right (Scale bar, 12 μm). c Anti-GFP Western blot of cross-linked GFP-αCat-C805/871 (C805/871) and GFP-αCatTCS-C805/871 (T-C805/871) cells. d Anti-GFP (anti-GFP) or anti-αABD (anti-αABD) Western blotting of the anti-GFP immunoprecipitate of GFP-αCatTCS-C805/871. Before adding the SDS sample buffer, the equal portions of the precipitate were treated for 30 min with or without thrombin (+Thr or Ctrl, correspondingly). Thrombin cuts the mutant (marked as GFP-αCat) into two fragments, αABD and GFP-αN/M. e The cells expressing GFP-αCatTCS-C805/871 were permeabilized, treated with (+Thr) or without (Ctrl) thrombin as above, and separated by SDS-PAGE. Left: Western blots probed by anti-GFP (anti-GFP) or by anti-αABD (anti-αABD). Note, αABD staining showed four species, which MW (indicated in kDa on the right) corresponded to dimers, trimers, tetramers, and pentamers of αABD (2α, 3α, 4α, and 5α, correspondingly). Right: the Oligomer Intensity Index (OII, the ratio between the intensities of the oligomer “n” to “n-1”) was quantified for 3α, 4α, 5α, and 6α based on five independent experiments. The ranges of distribution of the OII are shown. f Western blotting of GFP-αCatTCS-C805/871 and GFP-TCS-αABD-C805/871 cells probed with anti-αABD. g Fluorescence microscopy of αCatKO-A431 cells expressing GFP-TCS-αABD-C805/871 stained for GFP (GFP, green) and for F-actin (act, red). The left micrograph shows a merged image (Scale bar, 25 μm). Separate staining of the representative region (in a dashed box) is zoomed on the right (Scale bar, 15 μm). h Western blotting of cells expressing GFP-αCatTCS-C805/871 (αCat) and GFP-TCS-αABD-C805/871 (αABD) after permeabilization and thrombin treatment (as in e). The ranges of OII for each of the adduct are shown on the right (n = 5).

An interesting feature of the detected adduct ladder was that the oligomers corresponding to tetramers and pentamers consistently showed approximately the same intensities. We therefore assessed the relative abundance of each αABD oligomer. Based on four independent experiments, we determined an Oligomer Intensity Index (OII) - the ratio between the intensity of the oligomer n to that of n-1. It showed that the OII for trimers and tetramers varied between the values of 0.4 to 0.5 (Fig. 3e), while the OII for pentamers was much higher, ranging between 0.8 to 1.0. The index dropped to ~0.2 for the hexamers. Such а nonlinear OII distribution can be interpreted as F-actin-generating oligomers comprised of two to six CCCs, among which the pentamer is the most dominant species. One of the explanations for the low amounts of hexamers and the absence of higher-order oligomers was that their formation is hindered by structural constraints of interactions between the helical actin with a flat membrane. Another possibility was that the high-order oligomers were undetected simply because of their large size. To test the latter, we constructed mutant GFP-TCS-αABD, consisting of GFP, TCS, and a truncated form of αABD (residues 673-906, see Fig. 3a, f) lacking a part of its N-terminal H0 helix8,9,23,26. It has been shown that such truncated αABD is a strong actin binder that produces numerous short-lived actin-associated clusters (obviously with no membrane-imposed structural limitations) in A431 cells9,24,26. Immunofluorescence microscopy of the αCatKO-A431 cells expressing GFP-TCS-αABD confirmed that the mutant associated with the actin cortex (Fig. 3g). Cross-linking and thrombin treatment of these cells produced αABD oligomers of up to order 8 ( ~ 240 kDa). The OII of all species varied in range of 0.45 to 0.55 (Fig. 3h). Thus, in complete agreement with the Cryo-EM structural model, the isolated αABD forms a large variety of actin-bound oligomers without a preference for the particular size.

α-Catenin oligomerization is adhesion- and force-independent

Aforementioned results showed that α-catenin binding to F-actin generates linear oligomers of CCC, which we refer to as CCC/actin strands. We then asked if this process requires cadherin trans interactions. To answer this question, we cultured cells in low calcium media that prevents cadherin trans interactions34,42. Surprisingly, this manipulation neither decreased the levels of the adducts (Fig. 4a, lane LowCa), nor changed the adducts’ pattern found after thrombin cleavage (Fig. 4b). Alternatively, we used the adhesion-blocking antibody SHE78-7 to abolish E-cadherin trans interactions. Lane SHE in Fig. 4a shows that this antibody also had no effects on α-catenin oligomerization. LnB added for 20 min prior to cross-linking was sufficient to greatly reduce the amount of α-catenin oligomers detected both in low calcium media and in the presence of SHE78-7 antibody (Fig. 4a, lanes LowCa+LnB and SHE+LnB). The oligomers reappeared 15 min after LnB washout (Fig. 4a, lane LowCa-postLnB). These observations provide strong evidence that cadherin trans interactions are not required for CCC/actin strand formation.

a Western blot (probed for GFP, marked as in Fig. 1e) of GFP-αCat-C805/871-expressing cells cross-linked after culturing in standard media (Ctrl), in low calcium media for 3 h (LowCa), in presence of function blocking E-cadherin antibody (SHE), in low calcium media or with SHE antibody in combination with LnB (LowCa+LnB, SHE+LnB), and as in lane LowCa+LnB but 15 min after LnB removal (LowCa-postLnB). b Western blot of GFP-αCatTCS-C805/871 cells cultured in control (Ctrl) or low calcium media (LowCa). The cells were processed with thrombin as in Fig. 3e. c Projections of all x-y optical slices of wt A431 cells stained before permeabilization for E-cadherin ectodomain (Ecad, red) and after permeabilization for F-actin (actin, green). Bar, 20 µm. The zoomed area (dashed box) of a single optical z slice passed through a middle of the cells is presented at the bottom. Bar, 10 µm. The area shown by the arrow is further magnified in the insets. The optical z-cross-sections along the dashed lines are shown on the right. Bar, 10 µm. Note clear co-localization between surface-exposed E-cadherin and F-actin. d Projections of all x-y slices of GFP-αCat-C805/871 cells stained for GFP (GFP, green) and for F-actin (actin, red). Only green channel is shown. Bar, 20 µm. The areas in dashed boxes are zoomed and shown in individual staining on the bottom. The arrows mark some of numerous actin-enriched AJs. Bar, 10 µm. e Western blot probed for GFP of GFP-αCatC805/871-expressing cells cross-linked after culturing in standard media (Ctrl), with Y-27632 (Y), blebbistatin (Bleb), CK666 in combination with Y-27632 (Y + CK) or blebbistatin (Bleb+CK). f, g The parallel cultures of cells shown in (d) were stained for GFP and for vinculin or FBLIM1. f Quantification of peak intensities of vinculin and FBLIM1 in AJs (n = 15). The means +/- SD are indicated by bars. Statistical significance was calculated using a two tailed Student’s t-test. ****P < 0.0001. g Vinculin and FBLIM1 staining of the cells used for quantifications present in (f). Only isolated cell-cell contacts are shown. Bar, 10 μm.

To visualize CCC clustering on the cell plasma membrane in low calcium media, we stained the non-permeabilized cells for E-cadherin ectodomain and then, after their permeabilization, for F-actin. High resolution confocal microscopy of these cells clearly showed numerous tiny E-cadherin clusters aligned with actin filaments (Fig. 4c). These clusters were especially abundant on the actin-rich plasma membrane protrusions (see insets in Fig. 4c). A parallel staining of these non-permeabilized cells for β-catenin produced only weak, apparently non-specific staining (Supplementary Fig. 1), confirming that the cells were non-permeable for the antibodies and that the detected E-cadherin clusters were localized to the plasma membrane. While clearly insufficient to determine the exact architecture of the adhesion-incompetent CCC clusters, our imaging data, in combination with cross-linking experiments, confirms that αABD-actin interactions organize CCC into the CCC/actin strands independently of cadherin trans interactions. The abundance of CCC oligomers in low calcium media was also consistent with our previous reports showing that calcium removal triggers an immediate remodeling of cadherin strand-swap dimers from trans to cis organization21,34,42.

To exclude the possibility that formation of the CCC/actin strands in low calcium media was not a specific feature of A431 cells, we used another epithelial cell line, DLD1. In contrast to epidermal A431 cells, which form punctate AJs associated with the radial actin bundles24, colon carcinoma DLD1 cells form linear AJs, known as “zonula adherens”, associated with the prominent circumferential actomyosin bundles43. Such architecture of cell-cell contacts is typical for polarized epithelia in cell culture or in tissues. As shown in previous experiments, this cell-cell contact architecture was completely lost in the α-catenin-deficient variant of these cells, DLD-αCatKO (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Re-expression of GFP-tagged α-catenin or its C805/871 version in these cells completely rescued their cell-cell contact organization validating that our α-catenin cysteine mutant is fully functional. Cross-linking experiments with these cells also confirmed that a loss of adhesion in low calcium media had no effect on the α-catenin cross-linking (Supplementary Fig. S2b).

Our observation that the interactions of CCC with actin filaments are adhesion-independent suggests that the tensional stress on E-cadherin adhesions is not required for αABD binding to actin. To further validate this point, we treated the cells with the potent anti-actomyosin drugs, Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor, Y-27632, or the myosin II inhibitor, blebbistatin (10 μM and 20 μM, correspondingly, for 1 hour prior to cross-linking). In order to remove the forces caused by the ARP2/3-facilitated actin flow44,45, we also tested combinations of these drugs with an ARP2/3 inhibitor, CK666 (100 μM). In accordance with previous studies30,31,32,33,46, the drugs’ applications resulted in a dramatic rearrangement of AJs, from their typical radial appearance in control cells to less organized and dispersed in the treated cells. However, the drugs were unable to abolish AJ association with the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 4d, see also below). Correspondingly, neither of these drugs nor their combinations with CK666 were able to change α-catenin oligomerization in our cross-linking assay (Fig. 4e). To confirm that the drugs did release the tensional stress from the AJs, the blebbistatin-treated cells were stained for two AJ-associated proteins, vinculin and FBLIM1 (also known as LIM domain protein, migfilin). Both of these proteins employ force-activated recruitment into AJs either through binding to α-catenin [reviewed in 1, 5] or to mechanically strained F-actin47,48,49, correspondingly. Thus, these two proteins provide a readout for force across two different structural layers of AJs. The staining demonstrated that blebbistatin alone was sufficient to almost completely remove both proteins from AJs, confirming that our treatments abolished the tension applied to AJs (Fig. 4f, g). Collectively, our results showed that αABD generates the actin-bound CCC/actin strands independently of both actomyosin tension and trans-interactions of cadherin ectodomains.

No other CCC proteins are needed for αABD to produce CCC/actin strands

To determine whether other known activities of CCC in addition to αABD-actin binding are needed to generate CCC/actin strands, we used a fusion protein EcΔ-GFP-α506C805/871. This chimera contains E-cadherin extracellular and transmembrane domains and an α-catenin region (aa 506-906) encompassing the M3 domain, a linker, and αABD (Fig. 5a). As demonstrated previously50, this chimera produced actin-associated AJs in αCatKO-A431 cells (Fig. 5b). Our cross-linking assay also showed that this chimera, similar to the full-length α-catenin, formed actin-bound oligomers in both the control and in low calcium cultures (Fig. 5c). To test the role of trans E-clustering, we constructed a mutant, c/t-EcΔ-GFP-α506C805/871, which lacked both known trans dimer interfaces of E-cadherin (for X-dimers and strand-swap dimers) as well as its cis dimer interface (Fig. 5a). As expected, this mutant was unable to rescue cell-cell adhesion of the αCatKO-A431 cells or to produce AJs (Fig. 5d). Despite this, the cross-linking assay showed that both chimeras, the control and the adhesion-incompetent, generated approximately the same levels of the actin-based oligomers (Fig. 5f).

a Schematic representation of the E-cadherin-α-catenin chimera, EcΔ-GFP-α506C805/871, which consists of an intact N-terminal portion of E-cadherin (its ectodomain and transmembrane domains) fused through GFP with a C-terminal portion of α-catenin starting from M3 subdomain. Another chimera, c/t-EcΔ-GFP-α506C805/871, is the same as above but incorporates point mutations (listed on the bottom) inactivating all known inter-ectodomain interactions: one cis and two trans, strand swapped and X dimerization. b Projections of all x-y optical slices of αCatKO-A431 cells expressing EcΔ-GFP-α506C805/871 stained for GFP (GFP, green) and for F-actin (actin, red). Only green channel is shown for low magnification. Bar, 10 µm. The dashed box area is zoomed on the bottom and shown as separate staining. Note that the chimera forms AJs associated with the actin cytoskeleton. Bar, 10 µm. c Western blot probed for GFP of cells shown in (b) and collected from control culture (Ctrl) and from cross-linked cultures in standard media (XL-HighCa) or in low calcium media for 3 h (XL-LowCa). d Projections of all x-y slices of c/t-EcΔ-GFP-α506C805/871 cells stained for GFP (GFP, green) and for F-actin (actin, red). Only green channel is shown for low magnification. Bar, 10 µm. The dashed boxed areas are presented in both colors. Projections of five optical z slices encompassing the apical membrane marked by yellow box (#1) are zoomed on the right. Only a single optical slice passing through a ventral cell membrane (marked by a white box, #2) is shown on the bottom. Bars, 10 µm. Note that the apical ruffles, invadopodia-like structures (Inp), and cell-cell contacting protrusions (Prtr) are especially enriched with the chimera. e The line scan performed along the dashed line shown in (d). Note that no specific actin enrichment is observed in places rich for the chimera clusters. f Western blot probed for GFP of cells expressing EcΔ-GFP-α506C805/871 (Ec506) and its adhesion-incompetent mutant (c/t-Ec506), which were obtained from control cultures (Ctrl) and after cross-linking (XL).

Confocal microscopy showed that the adhesion-incompetent chimera c/t-EcΔ-GFP-α506C805/871 formed numerous actin-associated clusters, which likely consists of the oligomers detected by the cross-linking assay. The clusters were especially abundant along the ruffles of the apical cell membrane (see zoomed area of the apical membrane in Fig. 5d) as well as on two types of actin-rich structures formed on the ventral cell membrane. One such structure was invadopodia (or their precursors), which are widespread in tumor cells51. The second type of structure was the membrane protrusions along the cell edges, most often those that contact the neighboring cells. The intensity profile along the cell ventral membrane showed that these two structures exhibited about fivefold more GFP fluorescence than the surrounding cell membrane. By contrast, the level of F-actin at these sites was close to that in other areas of the ventral cell membrane (Fig. 5e). The latter observation suggested that the clustering of the adhesion-incompetent chimera was driven by αABD oligomerization on the actin cortex associated with specific membrane protrusions.

CCC/actin strands are generated on myosin-1c rich actin cortex

Our previous experiments had been unable to detect clustering of the E-cadherin mutant WK-EcGFP21,52, which, similar to c/t-EcΔ-GFP-α506C805/871, bears K14E and W2A point mutations that abolish both X and strand-swap trans dimerization (see21 for details). Our findings prompted us to reinvestigate this issue because the high fluorescence of the non-clustered pool of this mutant could impede the detection of small clusters by widefield microscopy, used previously. Indeed, despite a strong overall cytosolic and membranous fluorescence of the WK-EcGFP-expressing cells (Fig. 6a, All Z-slices), confocal and deconvolution images of their apical and ventral plasma membranes did show that the mutant formed clusters. The clusters were concentrated along the same membrane domains as the clusters of the adhesion-incompetent chimera, c/t-EcΔ-GFP-α506C805/871, at ruffles, invadopodia, and membrane protrusions in cell-cell contact areas (Fig. 6a, b). The plasma membrane localization of these clusters was confirmed by the staining of non-permeabilized cells using E-cadherin ectodomain mAb, HECD1 (Supplementary Fig. 3).

a Representative image of Ec/PcKO-A431 cells expressing WK-EcGFP stained for GFP (green) and for F-actin (red). Left: projections of all optical z slices show a broad localization of the mutant obscuring its plasma membrane organization. Bar, 10 µm. Right: a single optical z slice of the ventral membrane of the left image. A white dashed box of the left image is deconvolved and zoomed in the second row (z-slice of ventral membrane, deconvolved). Projection of five z slices (spanning 1 µm of the apical cell region) of a yellow box shown on upper image is zoomed on the bottom. Bars, 5 µm. Note that WK-EcGFP is enriched in the apical raffles, invadopodia (yellow arrow), and cell-cell contacting protrusions (white arrow). b The line scan performed along the dashed line shown in (a) shows the mutant in invadopodia (Inp) and in protrusion (Prtr). c WK-EcGFP cells were imaged for GFP (GFP, green) and myosin-1c (myo1c, red). Only an optical z slice with ventral membrane is shown. Bar, 10 μm. The boxed area is zoomed on the bottom. Bar, 5 μm. The optical XZ cross section along the dashed line is shown in (e). d Projections of all z slices of the EcGFP-expressing Ec/PcKO-A431 cells stained for GFP (green) and myosin 1c (red). Bar, 15 μm. The boxed area is zoomed on the bottom and presented as all z projections (All z slices) or only as a slice of ventral membrane (Z-slice of ventral membrane). Bar, 10 μm. f The line scan of GFP (green) and myosin-1c (red) fluorescence along the dashed lines shown in (c) and (d) (A.U., arbitrary units). Note that myosin-1c co-localizes with WK-EcGFP but is separated from EcGFP in AJs. g Average Pearson’s correlation coefficient between GFP and myoin-1c at cell-cell contacts in WK-EcGFP- and EcGFP-expressing cells. Correlations were calculated from single z slices of 15 areas (from 5 representative images) of the ventral membrane. The means +/- SD are indicated by bars. A two tailed Student’s t-test was used. ****P < 0.0001.

The next question, therefore, was whether any actin-associated protein specifically marked the actin cortex of the membrane protrusions that recruited WK-EcGFP. To identify possible candidates, we compared published WK-EcGFP and EcGFP proteomes52. Despite their high similarities, the proteome of WK-EcGFP showed some increase of myosin-1c, which, in fact, became its most abundant actin-binding protein. Therefore, we stained WK-EcGFP-expressing cells for myosin-1c. Remarkably, confocal microscopy showed that myosin-1c was concentrated in the same membrane compartments as WK-EcGFP clusters (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 4). Furthermore, close inspection and intensity profiles of cell-cell contact protrusions of these cells indicated significant colocalization of both proteins in these regions (Fig. 6c, f). Both proteins were also concentrated in the apical membrane ruffles (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Similar association with myosin-1c was detected in the c/t-EcΔ-GFP-α506C805/871 expressing cells (Supplementary Fig. 4b). A very different relationship was found between myosin-1c and the intact E-cadherin. As in other epithelial cells53, EcGFP-expressing A431 cells exhibited myosin-1c in the basolateral cortex (Fig. 6d, e). However, the AJs, while located in the same basolateral domain, showed only slight or even no increase of myosin-1c staining compared to nearby areas (Fig. 6d, f). The differences in relationship between myosin-1c with functional and adhesion-incompetent CCC was clearly reflected by PCC: its average value was relatively high (0.72) for WK-EcGFP, but only 0.36 for EcGFP (Fig. 6g). These results suggest that the trans cadherin interactions triggered segregation of CCC from the myosin-1c rich actin filaments.

The myosin-1c rich actin cortex is formed independently to CCC

CCC binding to actin filaments could be involved in formation of the intercellular protrusions enriched with myosin-1c. Alternatively, the interdigitated protrusions we observed in the α-catenin-deficient cells (see Fig. 1d) could also recruit myosin-1c independently to CCC. To explore this issue, we determined localization of myosin-1c in the αCatKO-A431 cells. Our data clearly shows that the protrusions interconnecting these cells (see Fig. 1) are enriched for myosin-1c (Fig. 7a). This observation suggests an attractive possibility that some CCC-independent processes within intercellular contacts generate a specialized actin cortex able to recruit a specific set of actin-binding proteins including myosin-1c and CCC-incorporated α-catenin. Since both CCC and myosin-1c are known to reside at the basolateral membrane of epithelial cells, we tested whether two key basolateral signaling proteins, DLG1 and scribble43,53, were also targeting the same protrusions. We verified this by immunostaining, which clearly showed that these two proteins were strongly enriched in the intercellular structures of αCatKO cells (Fig. 7b).

a Confocal fluorescence microscopy of the αCatKO-A431 cells stained for myosin-1c (myo1c, green) and F-actin (act, red). Projections of all optical z slices are shown. The left micrographs show merged images. A representative group of cells (in a dashed box) taken from the merged image is magnified on the right (Scale bar, 10 μm). b The αCatKO-A431 cells were stained for F-actin (act, red) in combination with staining for basolateral proteins, DLG1 (dlg1, green) or scribble (scrib, green) or for myosin-1c and DLG1. The stained cells are presented as in (a). Note that the protrusions located at the cell-cell contacts (some of which are indicated by arrows) recruit the basolateral markers.

Next, we tested whether the intercellular protrusions of WK-EcGFP-expressing Ec/PcKO-A431 cells, which recruit both myosin-1c and the WK-EcGFP mutant, also showed the basolateral characteristics. Double staining of these cells did show that WK-EcGFP and both scribble and DLG1, were located at these structures (Supplementary Fig. 5). Identification of the key basolateral polarity proteins in the intercellular protrusions in both αCatKO-A431 cells and Ec/PcKO-A431 cells expressing WK-EcGFP strongly suggest that these protrusions are in fact the undeveloped basolateral compartment of these cells. The mechanisms generating this compartment in the cells deficient for functional CCC and the mechanisms of preferential binding of CCC to this compartment are important subjects for further research.

Actin-dependent αABD oligomers contribute to general organization of AJs

The experiments presented above unequivocally showed that α-catenin generates short actin-bound CCC oligomers, CCC/actin strands. To address the role of αABD oligomerization in AJs, we compared αCatKO-A431 cells expressing two GFP-αCat-C805/871 mutants (Fig. 8a). The first one, GFP-αCatI792A-C805/871, incorporates a point mutation, I792A, which affects the most critical area of the αABD-actin interface. This mutation had been shown to dramatically reduce α-catenin binding to F-actin9,24,26. Consistent with this data, the I792A α-catenin mutant was unable to rescue AJs in αCatKO cells (Fig. 8b). Like the parental αCat-A431 cells, the cells expressing this mutant interacted with one another by numerous actin-rich protrusions. Some level of recruitment of the mutant into these protrusions could be caused by two factors: by its residual actin-binding activity and/or by trans/cis interactions of cadherin ectodomain. In complete agreement with the role of actin in CCC oligomerization, our cross-linking assay showed that this mutant generated only a negligible amount of adducts (Fig. 8c).

a Diagram of αABD mutants (depicted as in Fig. 1a) of α-catenin. b Fluorescence microscopy (projections of all optical slices) of the cells (the mutant names are on the left) stained for GFP (green) and F-actin (red). The left micrographs show merged images (Scale bar, 20 μm). The separate staining of the representative contacts (in dashed boxes) is zoomed on the right (Scale bar, 10 μm). c Western blotting probed for GFP of cells with GFP-αCat-C805/971 (αCatC), GFP-αCatV870S-C805/871 (V870S), and GFP-αCatI792A-C805/871 (I792A) without (Ctrl) or after cross-linking (XL). Right: Quantification (based on 8 experiments) of the adduct, a1 intensities relative to it in GFP-αCat-C805/871 normalized to the monomers. The means +/- SD are indicated by bars. d Time-lapse microscopy (at 10 s temporal resolution) of the cells expressing α-catenin mutants (abbreviated as in c). Isolated frames of the movies (Supplementary Movies 1, 2) are shown in the top row. The representative line scans along the white lines of 10 consecutive frames (spanning 1.5 min) were combined and differently colorized (color code is on the bottom). Right: Fluorescence intensity of AJs (the value of brightest pixel after background subtraction, the means +/- SD, n = 12 taken from two independent movies). e Dispase-based assay of cells expressing GFP-αCat-C805/971 (αCatC), GFP-αCatV870S-C805/871 (V870S), and GFP-αCatI792A-C805/871 (I792A). Left: Representative images showing the cell sheets detached from the dishes before and after mechanical stress (shaking). Right: Quantification (n = 4) of the size (in pixels) of the sheets before shaking (top) and the number of fragments obtained after shaking (bottom). The cells expressing GFP-αCat (αCat) and GFP-αCatV870A (V870A) are also shown in the graphs. Data are presented as mean values +/- SD. f Left: Vinculin and FBLIM1 staining of the representative cell-cell contacts (abbreviations as in e). Bar, 10 μm. Right: Quantification of peak mean intensities +/- SD of vinculin and FBLIM1 in AJs (15 AJs for each cell line were determined). Statistical significance was calculated using a two tailed Student’s t-test: ns, non-significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

The second mutant, αCatV870S-C805/871, contains a polar serine residue substituted for a hydrophobic residue V870, which should prevent αABD oligomerization by disrupting the key hydrophobic “knot” interconnecting two neighboring actin-bound αABDs8,9,25. Indeed, cross-linking the cells expressing this mutant showed that the V870S mutation reduced the amount of αABD oligomers to about 30% (Fig. 8c). The residual cross-linking was apparently caused by E-cadherin cis-interactions, which could still facilitate the attachment of the V870S mutant to the neighboring sites of F-actin. Examination of the cells expressing V870S mutant strongly supported this point of view. In a stark contrast to I792A mutant, the cells expressing the V870S mutant produced a high number of AJs, which were clearly aligned with actin filaments (Fig. 8b). However, the AJs in these cells were dispersed along the numerous actin-rich cell-cell contact protrusions. This “protrusion-rich” type of cell-cell contacts was similar to that found in αCatKO-A431 cells as opposed to the contacts between the cells expressing the intact α-catenin (Fig. 8b). This specific defect in the organization of cell-cell contacts was fully replicated using another V870 mutant, GFP-αCatV870A, in which V870 was replaced with Ala (Supplementary Fig. 6a). The lack of cysteine substitutions in this mutant validated that they had no impact on the observed cell-cell contact defects caused by αCatV870S-C805/871. Furthermore, our previous actin binding experiments showed that the V870A point mutation had little if any effect on the αABD-actin interactions24. Thus, unique and identical cell-cell contact defects in cells expressing both V870 α-catenin mutants were most likely induced by their failure to produce αABD oligomers.

For a more detailed analyses of AJs in cells expressing V870 mutants, we compared these cells with the control cells (cells expressing GFP-αCat or its cysteine C805/871 version) using time-lapse microscopy taken with 10 s temporary resolution (Fig. 8d and Supplementary Movies 1–4). Quantification of the fluorescence intensities showed that compared to the control cells, the fluorescence intensities of AJs in the V870 mutant cells dropped by ~50%. It also showed that AJs of the mutant cells were significantly less stable. To demonstrate this, we generated line scans of the representative cell-cell contacts from the movies (Fig. 8d and Supplementary Fig. 6b). They showed that the AJs of control cells remained stationary for 1-2 minutes. By contrast, the AJs of the V870 mutant cells changed their position and appearance even between two consecutive frames.

To further characterize the functional effect of V870 mutations, we probed whether they affect the intercellular adhesion tested by epithelial sheet (dispase) assay (Fig. 8e and Supplementary Fig. 6c). As expected, the confluent monolayer of the control cells detached from the substrate by dispase treatment contracted due to the contractile forces within the epithelial sheet. This contraction, determined by quantification of the sheet areas, was significantly less pronounced in cells expressing both V870 mutants and was completely blocked in the case of cells with the I792A mutant. The cells expressing the V870 mutants also exhibited reduced cell-cell adhesion strength as revealed by an increased number of fragments generated by mechanical stress applied to the lifted sheets. Again, the same manipulations yielded a much higher number of fragments in the case of the cells with the I792A mutant (Fig. 8e). This confirmed that the V870 mutations reduce but do not completely abolish both the strength of the adhesion and the junctional tensile forces. To validate the latest point, we stained the cells for FBLIM1 and vinculin (Fig. 8f and Supplementary Fig. 6a). As noted above, the recruitment of FBLIM1 and vinculin into AJs reflects the forces applied to the AJ-associated F-actin and to CCC, correspondingly. Surprisingly, the staining and quantification of the fluorescent signals showed that the recruitment of vinculin into AJs was severely affected (by ~50%), while the recruitment of FBLIM1 was nearly the same as in control cells. Neither of these proteins were detected in cell-cell contacts of cells expressing the I792A mutant of α-catenin. Taken together, our characterization of the cells expressing V870 mutants revealed that actin-dependent α-catenin oligomerization contributes to the strength of cell-cell adhesion and to the balance of forces applied to the different structural compartments of AJs.

Discussion

It is largely accepted that direct binding of α-catenin to F-actin through αABD plays at least two essential roles in cell-cell adhesion. The first one is stabilization of cadherin clusters that is needed to upregulate avidity of the adhesive AJ interface19,20,54,55. The second one is sensing the actomyosin contraction forces that regulate AJ maturation, in particular, the recruitment of vinculin56,57,58,59,60. In addition, αABD binding to actin has been proposed to play a third critical role in driving cadherin clustering24. This idea was suggested by a remarkable cooperativity of αABD binding to actin, the mechanism of which has been partially explained by the cryo-EM modeling. It shows that the αABD residue, Val870, integrates into the actin-binding interface of αABD attached to the neighboring site on the filament8,9,25. Such interactions between contiguous αABDs results in αABD oligomerization along the filaments. To demonstrate this process in cells, we engineered an α-catenin mutant, GFP-αCat-C805/871, enabling specific detection of such linear αABD oligomers using a targeted cross-linking approach. Experiments with two types of cells, A431 and DLD1, expressing the designed mutant, clearly show that αABD binding to actin does result in αABD oligomerization as suggested by the cryo-EM blueprint. The resulting oligomers consist of up to 6 α-catenin molecules, with the most abundant oligomeric species being a pentamer. Since α-catenin of the oligomers is incorporated into CCC, this oligomerization should place CCC along the filaments forming actin-bound linear arrays, which we define as CCC/actin strands.

Unexpectedly, our results show that formation of the CCC/actin strands in both A431 and DLD1 cells is adhesion-independent. Accordingly, low calcium media or a cadherin function-blocking antibody produces no effects on the strand formation. The strands generated by the E-cadherin-α-catenin chimera are also unchanged upon inactivation of both trans and cis binding sites of the chimera ectodomain. Such non-adhesive CCC/actin strands are detected by confocal microscopy as small actin-associated clusters in low calcium media or in cells expressing adhesion incompetent mutants of E-cadherin (WK-EcGFP) or E-cadherin-α-catenin chimera (c/t-EcΔ-GFP-α506C805/871). These non-adhesive strands might correspond to the previously described cadherin cis oligomers observed by various fluorescence techniques on the contact-free membrane16,61,62. In contrast to the fluorescence techniques, which identify cadherin oligomers with no structural details, the targeted cross-linking approach elucidates their specific supramolecular organization.

The non-adhesive CCC/actin strands of both, the c/t-EcΔ-GFP-α506C805/871 chimera and the WK-EcGFP mutant (expressed in α-catenin- and E/P-cadherin-deficient cells, correspondingly) are preferentially formed on the membrane protrusions, such as ruffles, invadopodia, and cell-cell contact protrusions with diverse morphology. The latter structures exhibit some common features with a heterogeneous group of actin-rich intercellular protrusions called tunneling nanotubes [reviewed in ref. 63]. We also found that such protrusions are the major cell-cell contacting structures in the α-catenin-deficient A431cells, suggesting that they are CCC-independent. The buildup of CCC/actin strands on these structures, where they should be in rapid equilibrium with monomeric CCC, explains a large body of data identifying cell protrusions as key sites for AJ formation64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71. The entrapment of CCC in cell-cell contacts by cadherin trans interactions1,2,13,14,15,72 has been considered a key mechanism of CCC targeting into the contacts. Our experiments, which show formation of the adhesion incompetent CCC/actin strands on the membrane protrusions interconnecting the cells, suggest that αABD binding to actin could be a complementary mechanism delivering E-cadherin into the cell-cell contacts.

To understand the mechanisms of CCC targeting the intercellular protrusions, we focused on their protein composition. We show that these protrusions in the α-catenin-deficient cells recruit myosin-1c, a member of the class I myosin superfamily. These proteins are known for their role in specific arrangement of actin filaments in both cell protrusions and basolateral domains of epithelial cells53,73. Accordingly, we found that the cell-cell contact protrusions in αCatKO-A431 cells are also enriched with, at least, two critical basolateral signaling proteins, scribble and DLG1. Such “basolateral” composition of the cell-cell protrusions in cells lacking functional CCC suggests an attractive hypothesis that they are generated in response to CCC-independent intercellular signaling events. While the mechanisms underlying the specific recruitment of CCC into these protrusions remain to be studied, it is tempting to speculate that some of the basolateral signaling events within these structures contribute to the specific organization of their actin cortex that, in turn, makes these protrusions an efficient producer of the CCC/actin strands. According to the two-state catch bond hypothesis, tension across the αABD-actin bonds promotes their switch from the initial weak to the strong oligomeric state22,28. However, we found that CCC/actin strand formation is independent from forces caused by myosin II motor activity or by Arp2/3-based actin polymerization by observing that the drugs inhibiting these proteins are unable to reduce CCC/actin strand formation. Nevertheless, it is impossible to exclude that the transition from weak to strong actin-binding states of αABD in the protrusions is mediated by forces alternative to those generated by myosin II. An alternative explanation for the CCC/actin strand formation in the protrusions is suggested by another in vitro binding study8, which shows that tension across actin filaments also can enhance αABD binding. It is possible, therefore, that myosin-1c (likely in combination with other motor proteins) located in the protrusions stretches the actin cortex thereby promoting αABD binding to actin and its concomitant oligomerization. Finally, the αABD conformational change, including unfolding of the αABD N-terminal helixes, H0 and H1, may be regulated in the protrusions by specific yet unidentified signaling events.

While a general contribution of the F-actin-dependent αABD oligomerization to AJ formation has been proposed in several studies23,28, here we directly show the role this process plays in cell-cell adhesion. We find that point mutations, V870S and V870A, of the V870 residue, which hydrophobicity is critical for the αABD oligomerization, dramatically affect cell-cell contacts of A431 cells. One of the most notable and specific features of the cells expressing these two mutants is that they, despite forming AJs, exhibit numerous cell-cell contact protrusions conspicuously similar to those in A431-αCatKO cells or in cells expressing adhesion-incompetent α-catenin or E-cadherin mutants. This observation suggests that CCC/actin strands in AJs are indispensable for inactivation of the membrane protrusive activity in cell-cell contacts.

The AJs in V870 mutant cells located along these intercellular protrusions are much more unstable than in control cells and show only weak recruitment of vinculin. The latter observation suggests that α-catenin V870 mutants experience a load below 5 pN that was shown to be necessary for unfurling the vinculin binding site74. Accordingly, the cells’ sheets lifted from the substrates by dispase show a much lower level of contraction than that of the intact α-catenin-expressing cells. Despite the significant defects, the AJs of V870 mutant cells are still able to recruit another force-dependent AJ protein, FBLIM1. In contrast to vinculin, FBLIM1, like other members of LIM-domain proteins, binds to the strained actin filaments47,48,49,75. While additional studies are clearly required to fully understand the role of CCC/actin strands in AJs, our experiments show that they directly or indirectly regulate a tensile force across the AJs.

The CCC/actin strands formed by αABD-actin interactions and E-clusters formed by the trans/cis interactions of cadherin ectodomain are fully compatible since the inter-protomer distance in the strands (~6 nm) is close to that (~7 nm) in E-clusters7,8,9. A long linker connecting αABD to the preceding M domain apparently provides additional structural flexibility allowing CCC/actin pentamers to comply with E-clusters. The most likely scenario therefore is that in cell-cell contacts the CCC/actin strands integrate into E-clusters forming composite oligomers, which we refer to as E/actin CCC clusters (Fig. 9). Importantly, the incorporation of just one CCC/actin strand into the E-cluster, which itself is too unstable to play a role in adhesion19, should increase its overall binding energy thereby increasing its adhesive capacity. A possibility for an intermix of actin-bound and actin-uncoupled CCC in AJs has been shown by efficient incorporation of the tail-deleted E-cadherin mutant into the AJs built by endogenous E-cadherin15. Incomplete saturation of AJs with CCC/actin strands is also suggested by the observation reported here that ~50% of E-cadherin in AJs is soluble in Triton X100 buffers. Altogether, it appears that AJs at each given moment consist of numerous E-clusters incorporating various numbers of CCC/actin strands. Such organization corresponds well with the immuno-EM images of cadherin clusters formed between the cells and the cadherin-coated substrate20. Many of those clusters have been observed as straight lines of three to six gold nanoparticles (~6 nm each) that perfectly fit the characteristics of CCC strands. More complex clusters could arise from a growth of these strands through E-clustering and from the addition of new CCC/actin strands.

a Structural representation of an isolated CCC. Left: The side view of CCC. It displays the cadherin extracellular region (ectodomain), depicted by five ellipsoids corresponding to cadherin extracellular domains, plasma membrane region (PM), and intracellular cadherin tail in complex with catenins (cadherin tail+catenins). Two CCC domains playing critical roles in adhesion are specified: (i) The amino-terminal domain (EC1). Its key adhesion interface residue, W2, is indicated by red dot; (ii) the actin-binding domain of α-catenin, αABD, and the flexible linker separating it from the rest of CCC (αABD+ linker, both shown in red). Right: A vertical projection of the cadherin ectodomain and αABD bound to actin. The ectodomain is depicted as an arrow, its pointed end corresponds to the EC1 domain. The red dot represents the W2 residue. b Types of inter-CCC interactions. Three types of interactions between CCCs have been identified: two modes of interactions are known for the ectodomain, cis-binding (cis) and trans-binding (trans, the ectodomains colored in gray and green belong to two adjacent cells). Note that trans-interacting ectodomains are perpendicular to each other. Inside the cells CCCs interact in cis through αABD-actin interactions (αABD-actin). c Types of CCC oligomers. The inter-CCC interactions spontaneously produce two types of oligomers: (i) At sites of cell-cell contacts, cis and trans interactions of the ectodomain form E-clusters (reviewed in refs. 2,3,72). (ii) Predominantly at cell protrusions, the αABD-actin interactions generate CCC/actin strands (this study). d Intermix of two oligomers. Both oligomerization processes could be intermixed forming a composite CCC oligomer (E/actin cluster). The size of the E/actin clusters is apparently variable and could incorporate different number of CCC/actin strands.

In summary, our findings show that cadherin clusters that provide strength and plasticity to AJs75,76 synergistically integrate two independent CCC oligomerization processes. The first generates actin bound CCC/actin strands. They preferentially form within cell-cell contacts that might be mediated by signaling mechanisms also involved in the initiation of the basolateral cell membrane. The second type of oligomers, 2D E-clusters, are generated in the cell-cell contacts through trans and cis interactions of the cadherin ectodomain (reviewed in refs. 1,2,3,72). Our results suggest that the clusters formed by the integration of CCC/actin strands with E-clusters locally suppress membrane protrusive activities and generate a tensile force involved in AJ maturation. These results open avenues for future research to investigate the signaling and structural events associated with AJ formation and their defects in various human diseases.

Methods

Plasmids

The plasmids (all in pRcCMV) encoding GFP-tagged human αE-catenin (denoted GFP-αCat), as well as GFP-tagged human E-cadherin (EcGFP) and its mutant WK-EcGFP, in which its trans binding interface is inactivated by two point mutations, W2A and K14E, have been reported24,52. The E-cadherin-α-catenin chimera EcΔ-GFP-α506 was also previously described50. PCR-based mutagenesis or gBlock replacements of these plasmids (pRcCMV-WK-EcGFP and pRcCMV-GFP-αCat) was used for constructing all other mutants described here. The sequences of the used primers and gBlocks are provided in the Source File. The general maps of all mutants are presented in Figs. 1, 3, and 8. All plasmid inserts were verified by sequencing.

Cell culture and transfection

The DLD1, A431 cells were originally obtained from ATCC (CCL-221, CRL-1555, correspondingly) and had been routinely used in the lab. The E-cadherin/P-cadherin-deficient, Ec/PcKO-A431 cells expressing EcGFP and WK-EcGFP (at identical expression levels, see ref. 52), and α-catenin deficient αCatKO-A431 cells have been previously described43,52. The DLD-αCatKO cells were obtained from DLD1 cells using the protocol described for αCatKO-A431 cells52. Other cells were obtained using stable transfection with the corresponding plasmids of the Ec/PcKO-A431, αCatKO-A431 or DLD-αCatKO cells as indicated. The cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the company protocol. After selection of the Geneticin-resistant cells (0.5 mg/ml), the cells were sorted for transgene expression by FACS, and only moderate-expressing cells were used. At least three clones were selected for each construct, and all were tested in most of the assays. The levels and sizes of the recombinant proteins in the obtained clones were analyzed by Western blotting. All clones of cells expressing a particular transgene exhibited the same phenotype. Representative data for one of three clones is presented. The Dispase assay was performed as described in ref. 77. In brief, confluent cultures of cells grown on 5 cm dishes were incubated with 2.4 U/ml Dispase II (Sigma, D4693) in DMEM at 37°C, for 30 min. Cells lifted from the substrate as an intact cell sheet were imaged and then the sheets were submitted to mechanical stress on a shaker at 60 rpm. For measuring the sheet area and counting the sheet fragments, the ImageJ tools (“cell count” and “Polygon selection”) were used.

For the Ca2+-switch assay, cells were cultivated in a low Ca2+ medium (20 µM Ca2+) for the indicated time. The drugs were added for 60 min at the following concentrations: Latrunculin B (1 μM), Y-27632 (10 μM), blebbistatin (20 μM), CK666 (100 μM).

Cross-linking, SDS-PAGE, immunoprecipitation, and thrombin cleavage

For cross-linking, 2 day-old confluent cultures grown in 24-well tissue culture dishes were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 0.5 mM CaCl2 (PBS-C) and cross-linked by incubation for 5 min on ice with ice-cold PBS containing 40 μM of cysteine-specific cross-linker BMB (ThermoFisher). The reaction was stopped by washing the cells with PBS with dithiothreitol (1 mM). The cells were then lysed in SDS sample buffer and the adducts were analyzed by Western blotting as previously described78. In brief, the total lysates were separated on precast 3–8% Tris-acetate gels (Invitrogen), which are ideal for the separation of large MW proteins.

The coimmunoprecipitation assays have been performed as described previously78. In brief, confluent A431 cells expressing recombinant proteins grown on 10 cm plates were extracted with 1.5 ml of IP-buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM AEBSF, 2 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100). The insoluble material was removed by centrifugation and the lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation either by subsequent incubations with anti-Ecad antibody SHE78-7 (4 μg/ml) and protein A-beads or by incubation with GFP-trap beads (Chromotek). After incubation, the beads were washed four times in IP-buffer, boiled in 30 μl of SDS-sample buffer, and loaded on SDS-PAGE gels. For non-crosslinked samples the precast 4-15% Tris-Glycine Bio-Rad gels were used. Restriction grade thrombin cleavage kit (Novagen, 69671-3) was used for thrombin cleavage as indicated by manufactory protocol using thrombin dilution 1:250 and 30 min incubation time at RT in the provided thrombin cleavage buffer. For cell extraction (or permeabilization before thrombin cleavage), the 1% triton X100 in the cytoskeleton preservation buffer (100 mM PIPES, pH 6.9; 1 mM MgCl2; 1 mM EGTA) was used.

Chemiluminescence was detected via the Azure C300 Chemiluminescent Imager (Azure Biosystems, Dublin, CA) and band intensities were analyzed using ImageJ software (rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Oligomer intensity index (OII) was calculated as a ratio between the intensities of a band corresponding to the oligomer of order “n” to that of “n-1”. Only bands of unsaturated intensities loaded on the same gel were used in the evaluation of the Western blot data. In all cases the figures present Western blots without any modifications of their original contrast/intensities. All presented Western blot results were reproduced in ate least five independent experiments. A molecular weight protein marker (10–460 kDa); HiMark #LC5699, Invitrogen that include 31, 41, 55, 71, 117, 171, 238, 268 and 460 (all in kDa) were used for MW analyzes of the cross-linked adducts in Tris-Acetate gels A High Range marker (Cell Signaling 12949) that includes 43, 52, 72, 95, 140, 175, 250, 315 kDa were loaded with the conventional samples on Tris-Glycine gels.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

For immunofluorescence, cells were grown for 2 days on glass coverslips or imaging glass-bottom dishes (P35G-1.5; MatTek) and were fixed with 3% formaldehyde (5 min) and then permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100, as described previously75,76. Wide-field images (Figs. 1d, 2a, 3b, g, 4g) were taken using an Eclipse 80i Nikon microscope (Plan Apo 100 × /1.40 objective lens) and a digital camera (CoolSNAP EZ; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). The confocal images were taken using a Nikon AXR laser scanning microscope equipped with a Plan Apo 60 x ×/1.45 objective lens. Immediately before imaging, the dishes were filled with 90% glycerol. The images were then processed using Nikon’s NIS-Elements software. Results of each immunostaining was independently reproduced not less than four times and images taken from different experiments were used for quantifications.

For immunostaining the following antibodies were used: mouse anti-E-cadherin mAb clones SHE78-7 and HECD1 (Takara, M126 and M106), mouse anti-vinculin (Sigma, V9264) or anti-DLG1 (BD Biosciences, 610874), chicken anti-GFP (Novus, NB100-1614), rabbit anti-FBLIM1 (Novus, NBP2-57310), anti-β-catenin (Invitrogen, PA5-16762), anti-myosin 1c, anti-α-catenin, and anti-scribble (Abcam, ab194828, ab51032, ab36708), anti-αABD (Cell Signaling, 36611). In all cases the antibodies were used at 1:100 dilution of the manufacturing stock solution. Specificity of all listed antibodies, except anti-GFP, was tested by a combination of Western blotting and specific CRISPR/Cas9 KO. All secondary antibodies were produced in Donkey (1:100, Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories). Alexa-Fluor-555–phalloidin and Latrunculin B were purchased from Invitrogen.

Live-cell imaging

The live cell imaging experiments were performed essentially as described previously15,76 using a halogen light source. In brief, cells were imaged (in IP-buffer, Fig. 2e, or in L-15 media with 10% FBS, Fig. 8 and Supplementary Fig. 6) by an Eclipse Ti-E microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) at RT or 37°C controlled with Nikon’s NIS-Elements software. The microscope was equipped with an incubator chamber, a CoolSNAP HQ2 camera (Photometrics) and a Plan Apo VC 100 x /1.40 lens. The 2 × 2 binning mode was used in all live-imaging experiments. At this microscope setting, the pixel size was 128 nm. All images were saved as Tiff files and processed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Data processing, statistics and reproducibility

All images were processed and analyzed using Nikon’s NIS-Elements ver. 5.02. For line scan analysis, the Element’s in-built line profile function was used to draw a 1pix wide line across the junctions. For peak intensity measurement, the highest intensity on the Y-axis was recorded. A minimum of 15 independent junctions were scanned from five different images. For Pearson’s correlation quantification, the images were processed with limited background reduction and denoising function of NIS-Element 5.02 and then Element’s Pearson function was used to measure the correlation between green and red fluorescence of the selected cell-cell contact areas (10 × 10 μm) of the confocal images. Representative 15 areas taken from 5 images taken from at least two independent experiments were analyzed. The charts and error bars were plotted using GraphPad Prism version 10.2.0. Statistical significance was analyzed for all figures using student’s two-tailed t test for two groups. Asterisks are used to denote significance, which value is indicated in the figure legends. A p value that was less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All imaging and cross-linking experiments were performed at least four times and were reproducible in all cases. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. The Investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data necessary for a full evaluation of the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary files. The reagents, experimental details, confocal raw imaging data are available from the corresponding author if the reasons for the request are provided. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Mège, R. M. & Ishiyama, N. Integration of cadherin adhesion and cytoskeleton at adherens junctions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 9, a028738 (2017).

Honig, B. & Shapiro, L. Adhesion potein structure, molecular affinities, and principles of cell-cell recognition. Cell 181, 520–535 (2020).

Troyanovsky, S. M. Adherens junction: the ensemble of specialized cadherin clusters. Trends Cell Biol. 33, 374–387 (2023).

Miller, P. W., Clarke, D. N., Weis, W. I., Lowe, C. J. & Nelson, W. J. The evolutionary origin of epithelial cell-cell adhesion mechanisms. Curr. Top Membr. 72, 267–311 (2013).

Yap, A. S., Duszyc, K. & Viasnoff, V. Mechanosensing and mechanotransduction at cell-cell junctions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 10, a028761 (2018).

Harrison, O. J. et al. The extracellular architecture of adherens junctions revealed by crystal structures of type I cadherins. Structure 19, 244–256 (2011).

Boggon, T. J. et al. C-cadherin ectodomain structure and implications for cell adhesion mechanisms. Science 296, 1308–1313 (2002).

Mei, L. et al. Molecular mechanism for direct actin force-sensing by α-catenin. Elife 9, e62514 (2020).

Xu, X. P. et al. Structural basis of αE-catenin-F-actin catch bond behavior. Elife 9, e60878 (2020).

Sisto, M., Ribatti, D. & Lisi, S. Cadherin signaling in cancer and autoimmune diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 13358 (2021).

Lin, W. H., Cooper, L. M. & Anastasiadis, P. Z. Cadherins and catenins in cancer: connecting cancer pathways and tumor microenvironment. Front Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 1137013 (2023).

Yap, A. S., Brieher, W. M., Pruschy, M. & Gumbiner, B. M. Lateral clustering of the adhesive ectodomain: a fundamental determinant of cadherin function. Curr. Biol. 7, 308–315 (1997).

Wu, Y. et al. Cooperativity between trans and cis interactions in cadherin-mediated junction formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 17592–17597 (2010).

Wu, Y., Vendome, J., Shapiro, L., Ben-Shaul, A. & Honig, B. Transforming binding affinities from three dimensions to two with application to cadherin clustering. Nature 475, 510–513 (2011).

Hong, S., Troyanovsky, R. B. & Troyanovsky, S. M. Spontaneous assembly and active disassembly balance adherens junction homeostasis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 3528–3533 (2010).

Chandran, R., Kale, G., Philippe, J. M., Lecuit, T. & Mayor, S. Distinct actin-dependent nanoscale assemblies underlie the dynamic and hierarchical organization of E-cadherin. Curr. Biol. 31, 1726–1736.e4 (2021).

Thompson, C. J., Vu, V. H., Leckband, D. E. & Schwartz, D. K. Cadherin cis and trans interactions are mutually cooperative. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2019845118 (2021).

Nagendra, K. et al. Push-pull mechanics of E-cadherin ectodomains in biomimetic adhesions. Biophys. J. 122, 3506–3515 (2023).

Hong, S., Troyanovsky, R. B. & Troyanovsky, S. M. Binding to F-actin guides cadherin cluster assembly, stability, and movement. J. Cell Biol. 201, 131–143 (2013).

Strale, P. O. et al. The formation of ordered nanoclusters controls cadherin anchoring to actin and cell-cell contact fluidity. J. Cell Biol. 210, 333–346 (2015).

Hong, S., Troyanovsky, R. B. & Troyanovsky, S. M. Cadherin exits the junction by switching its adhesive bond. J. Cell Biol. 192, 1073–1083 (2011).

Buckley, C. D. et al. Cell adhesion. The minimal cadherin-catenin complex binds to actin filaments under force. Science 346, 1254211 (2014).

Hansen, S. D. et al. αE-catenin actin-binding domain alters actin filament conformation and regulates binding of nucleation and disassembly factors. Mol. Biol. Cell. 24, 3710–3720 (2013).

Chen, C. S. et al. α-Catenin-mediated cadherin clustering couples cadherin and actin dynamics. J. Cell Biol. 210, 647–661 (2015).

Rangarajan, E. S., Smith, E. W. & Izard, T. The nematode α-catenin ortholog, HMP1, has an extended α-helix when bound to actin filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 299, 102817 (2023).

Ishiyama, N. et al. Force-dependent allostery of the α-catenin actin-binding domain controls adherens junction dynamics and functions. Nat. Commun. 9, 5121 (2018).

Arbore, C. et al. α-catenin switches between a slip and an asymmetric catch bond with F-actin to cooperatively regulate cell junction fluidity. Nat. Commun. 13, 1146 (2022).

Wang, A., Dunn, A. R. & Weis, W. I. Mechanism of the cadherin-catenin F-actin catch bond interaction. Elife 11, e80130 (2022).

Borghi, N. et al. E-cadherin is under constitutive actomyosin-generated tension that is increased at cell-cell contacts upon externally applied stretch. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 12568–12573 (2012).

Krendel, M. et al. Myosin-dependent contractile activity of the actin cytoskeleton modulates the spatial organization of cell-cell contacts in cultured epitheliocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 9666–9670 (1999).

Sahai, E. & Marshall, C. J. ROCK and Dia have opposing effects on adherens junctions downstream of Rho. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 408–415 (2002).

Ivanov, A. I., Hunt, D., Utech, M., Nusrat, A. & Parkos, C. A. Differential roles for actin polymerization and a myosin II motor in assembly of the epithelial apical junctional complex. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16, 2636–2650 (2005).

Shewan, A. M. et al. Myosin 2 is a key Rho kinase target necessary for the local concentration of E-cadherin at cell-cell contacts. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16, 4531–4542 (2005).

Troyanovsky, R. B., Sokolov, E. & Troyanovsky, S. M. Adhesive and lateral E-cadherin dimers are mediated by the same interface. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 7965–7972 (2003).

Harrison, O. J. et al. Nectin ectodomain structures reveal a canonical adhesive interface. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 906–915 (2012).

Benjamin, J. M. et al. AlphaE-catenin regulates actin dynamics independently of cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 189, 339–352 (2010).

Wood, M. N. et al. α-Catenin homodimers are recruited to phosphoinositide-activated membranes to promote adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 216, 3767–3783 (2017).

Tang, V. W. & Brieher, W. M. α-actinin-4/FSGS1 is required for Arp2/3-dependent actin assembly at the adherens junction. J. Cell Biol. 196, 115–130 (2012).

Gilbert, M. & Fulton, A. The specificity and stability of the triton-extracted cytoskeletal framework of gerbil fibroma cells. J. Cell Sci. 73, 335–415 (1985).

Penman, S. et al. The three-dimensional structural networks of cytoplasm and nucleus: function in cells and tissue. Modem. Cell Biol. 2, 385–415 (1983).

Laur, O. Y., Klingelhöfer, J., Troyanovsky, R. B. & Troyanovsky, S. M. Both the dimerization and immunochemical properties of E-cadherin EC1 domain depend on Trp(156) residue. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 400, 141–147 (2002).

Klingelhöfer, J., Laur, O. Y., Troyanovsky, R. B. & Troyanovsky, S. M. Dynamic interplay between adhesive and lateral E-cadherin dimers. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 7449–7458 (2002).