Abstract

The development of disordered Li dendrite and the adverse reaction between Li and electrolyte impede practical use of Li metal batteries (LMB). Herein, we propose quasi-two-dimensional fluorinated metal-organic framework carbon (q2D-FcMOF) that is utilized to construct artificial solid electrolyte interface (ASEI) to achieve robust interfacial protective double-layer. The outer organic layer provides ample space for Li deposition, while the inner inorganic LiF layer promotes conduction of Li+ and blocks electron transport. Metal clusters within the hybrid layer are uniformly dispersed, encouraging Li+ to cluster around metal active sites that are thermodynamically compatible with Li. Consequently, q2D-FcZ8@Li symmetrical batteries demonstrate an ultralong cycle life over 3600 h. When paried with commercial cathodes, the cells exhibite cyclability under conditions of high-loading, lean-electrolyte, even exposure to air for some time. This research suggests an effective method for fabricating ASEI using 2D quasi-ordered superstructure MOF NPs, which is expected to the development of LMB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

LMB are viewed as an alternative to commercial Li-ion batteries, particularly in the development of electric vehicles and portable electronic devices, owing to the Li anode’s high theoretical capacity (3860 mAh g–1) and low electrode potential (−3.04 V)1,2,3,4. The disparity between the electron energy gap of the electrolyte’s lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) and highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the Fermi level of the Li anode makes the electrolyte susceptible to reductive decomposition5,6,7. This process results in the formation of reduction products, which are deposited on the Li surface to create the solid electrolyte interface (SEI)8,9. However, SEI undergoes cracking and self-repair during Li plating/stripping, leading to the depletion of electrolyte and active Li, increased electrode impedance, and the formation of fresh Li-metal tips that become active sites10,11. These sites promote bifurcated growth of Li dendrites, which can damage the fragile and uneven SEI, causing short circuits and reduced coulomb efficiency12,13,14,15,16. Consequently, numerous promising approaches have been suggested to establish a robust and stable SEI that shields the anode from ongoing corrosive interactions with the electrolyte by controlling the SEI chemistry and Li morphology17,18,19,20,21.

The development of an ASEI at the Li/electrolyte interface can passivate the Li anode, enhancing its oxidation resistance and promoting storage stability22. LiF characterized by large band gap, low Li+ diffusion energy barrier, and high surface energy is notable for its ability to block electron penetration and expedite Li+ diffusion23,24,25,26,27. However, the precise regulation and clever construction for inducing a robust LiF-rich SEI remain challenging28,29. Metal-organic frameworks (MOF), significant in synthetic spatial networks, offer a versatile toolbox due to the diversity in linkers and metal nodes, allowing for varied applications30. MOFs possess an adjustable internal pore environment and high porosity, providing a substantial specific surface area31. Upon simple heat treatment, MOFs can transform into unique microporous carbon with well-defined metal clusters32. This pore structure facilitates organized ion channels, serving as ASEI components or as fillers in solid polymer electrolytes to enhance Li+ conductivity33. Nonetheless, these scattered particles often result in limited improvement in ionic conductivity due to the discontinuous Li+ channels created by isolated pores. The quasi-two-dimensional (q2D) superstructure of the MOF nanoarray can effectively resolve these issues. Compared with randomly stacked nanoparticles (NPs), regular q2D arrangements have advantages in terms of structure, including short charge diffusion distances, large contact areas of reactants, enhanced charge transfer between NP units, specific edge effects that can enhance chemical activity, ultrathin and unique molecular arrays, and infinitely ordered porous structures34,35. Moreover, the uniform size and shape of MOF NPs prevent the formation of coalesced surface covering linkers, which are suitable for use as fluorination carriers and in the construction of q2D superstructures36.

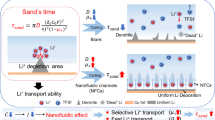

In this study, we proposed the creation of q2D ordered MOF NP superstructures using ice-templating of an aqueous colloidal solution, serving as the precursor for fluoridation. By subjecting MOF to mild fluorine gas treatment, chemically active fluorine can be introduced into the MOF structure. This process yields q2D-FcMOF, employed to establish robust and stable interfacial protective layer (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The versatility of the ice-templating method enables the fabrication of superstructures with a broad range of particle size distributions and various MOF combinations by altering metal nodes and coordination monomers. The precarious fluoride present on the q2D-FcMOF NPs irreversibly interact with Li to form uniform organometallic framework/inorganic LiF hybrid double-layer ASEI on the Li surface (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The organometallic frame layer is homogeneously dispersed in the matrix, demonstrating considerable lithiophilicity, a low work function and numerous deposition sites (Fig. 1a). This structure significantly reduces the Li nucleation barrier and near-surface Li+ consumption, facilitating the uniform formation and growth of Li nuclei. The neatly organized q2D superstructures network of MOF NPs offers ample space for Li dispersion, segmenting the bulk Li into smaller domains to lessen effective current density. This arrangement equalizes the distribution of the electric field and Li+ flux, preventing charge accumulation (Fig. 1b). Additionally, the hollow MOF structure mitigates the issue of Li infinite volume change. The inorganic layer, enriched with distributed LiF, prevents electron penetration through the SEI while facilitating rapid Li+ transfer; thus, harmonizing the kinetic behaviors of electrons and Li+. The LiF crystal phases formed through different nucleation do not completely fuse, leading to structural space defects. These minute defects facilitate lithium-ion transport37 (Supplementary Fig. 2). And the heterogeneous interface formed by organometallic framework/inorganic LiF can promote the conduction of Li+, each layer play distinct roles, working in harmony to achieve long-term cycle performance for a stable and durable LMB. As expected, the q2D-FcZ8@Li, demonstrating the highest Li adsorption energy, exhibits superior electrochemical performance compared to other q2D-FcMOF@Li. q2D-FcZ8@Li | |Cu shows ultrasmooth and dense Li deposition, sustaining over 500 cycles with an ultrahigh CE of 99.12%. The symmetrical q2D-FcZ8@Li presents a low overpotential of 44 mV and an exceptional cycling life of 3600 h. Paired with LiFePO4 (LFP) or LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 (NCM811) cathodes, the battery maintains excellent rate performance and longevity, even under high-loading and lean lectrolyte conditions. The protective double-layer ASEI on Li also positively influences air penetration prevention.

Results

Characterization of distinctive q2D configuration

q2D-cMOF self-assembles into uniform two-dimensional sheet morphologies (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Figs. 3, 4). MOF nanoparticles are tightly bound to each other through van der Waals forces. This structure effectively exposes surface of the nanocrystals, providing more channels for charge transport and adsorbing additional ion. Notably, crystal size of q2D-cZ8 is a regular dodecahedron with a particle size of about ~100 nm. Despite the diversity in coordination monomers and metal nodes, and the variability in particle size, the q2D-cMOF orderly self-assembles into sheet q2D structures under consistent freeze-drying conditions. The growth mechanism of q2D-MOF is characterized as the nanoparticle extrusion process driven by the ice template, which is elaborated on in the supporting information. TEM images confirmed the regular hexagonal structure of q2D-cZ8 under plane projection (Fig. 2b). Complete quadrilaterals, diamonds, and rectangles under the plane projection were observed for q2D-cZ67, q2D-cU66, and q2D-cNiMOF (Supplementary Fig. 5). High-resolution TEM images reveal nanocrystalline regions with distinct lattice fringes, corresponding with the distribution of elements (Supplementary Fig. 6). The morphology of q2D-FcMOF undergoes noticeable alterations due to corrosion by F2. The surface becomes rougher with folds emerging (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 7). The inherent regular structures of q2D-FcZ8 and q2D-FcZ67 are disrupted by fluoridation, leading to the etching of clear edges. The etched edges and corners exhibit high curvature, increasing the area available for contact with active substances. Nonetheless, q2D-FcMOF still retain the characteristics of the q2D and the inherent microscopic size of q2D-cZ8 and q2D-cZ67. TEM images of q2D-FcZ8 and q2D-FcU66 indicate an uneven distribution of particles, with layers being stacked upon each other (Supplementary Fig. 8). In high-resolution TEM images, distinct lattice fringes corresponding to the (110) and (101) crystal faces of ZnF2 are apparent. This suggests that q2D-FcZ8 is essentially heterojunction composite structure comprising ZnF2 and fluorinated carbon framework (Fig. 2d). Elemental analysis reveals uniform distribution of C, N, F, and Zn (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Table 1).

a SEM images of q2D-cZ8. b High-resolution TEM images of q2D-cZ8 (Scale bar of inset: 5 nm). c SEM images of q2D-FcZ8. d High-resolution TEM image of q2D-FcZ8. e STEM image with corresponding elemental mapping of q2D-FcZ8. f Nitrogen isotherms of q2D-FcZ8. g XRD patterns of q2D-FcZ8 and q2D-FcZ67. h Raman spectra of q2D-FcMOF. i FTIR spectra of q2D-FcMOF. j C1s XPS spectra of q2D-FcZ8. k F1s XPS spectra of q2D-FcZ8. l Normalized Zn K-edge XANES (with enlargement in the inset). m Fourier transforms of k3-weighted Zn K-edge EXAFS, n Wavelet transforms for Zn K-edge EXAFS signals of Zn foil, ZnO, q2D-cZ8 and q2D-FcZ8.

The porous textures were measured by N2 isothermal adsorption to analyze the pore size and distribution (Supplementary Fig. 9). The specific surface area and pore size of the fluorinated products are greater than the precursors because F2 etched the carbon skeleton at the pore edge; thus, expanding the pore structure and providing an ordered channel for the transport of Li+ (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 10)38. The outward contraction of q2D structures during pyrolysis can prevent a decrease in microporosity and inhibit the collapse of the organic framework. The XRD patterns of q2D-cZ8 show a broad peak at ~22.5°, corresponding to the diffraction of the (002) lattice planes of low-graphitic carbon. Conversely, broad reflection peaks corresponding to related metal compounds can be clearly observed of q2D-cZ67 (CoO), q2D-cU66 (ZrO2), and q2D-NiMOF (Ni2S3) owing to the peak corresponding to high-intensity metal compounds masking the carbon peak of the lower graphitic carbon (Supplementary Fig. 11). The hyperactive fluorine atoms substitute for the heteroatom, and broad peak emerges for the corresponding fluorinated metal (ZnF2, CoF2, ZrF4, and NiF2), indicating that the fluorinated metal is dispersed in the amorphous carbon skeleton and effectively hybridized (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 12). Compared to Raman spectrum of q2D-cMOF (Supplementary Fig. 13) and q2D-FcMOF (Fig. 2h), the increase in the calculated ID/IG ratio and broadening of the G-band reveal that the chemical bond formed between the C and F atoms destroys the original arrangement and inherent aromaticity with increasing disorder39. The fluorine species are characterized by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. q2D-cMOF exhibited a significant signal at 1620 cm–1, corresponding to the characteristic peak of C = C bond on the aromatic ring (Supplementary Fig. 14). Fluorination does not completely demolish the aromatic conjugated structure, but more prominent peaks appeared at 1212 cm–1 and 1385 cm–1, corresponding to the peak attributed to the stretching vibration of covalent C-F bonds and -CF2 group (Fig. 2i).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) survey demonstrated that q2D-cMOF have similar concentrations of metal in the range of 7–12 at% (Supplementary Figs. 15, 16). The pronounced F signal indicates substantial F-doping, with the concentration of metal atoms decreasing to 4–7 at%. The characteristic metal peaks of the fluorinated products exhibit a significant shift towards higher binding energy, because the chemical environment of metal elements is altered by the transformation of M-C (M = Zn, Co, Zr, Ni) bonds into M-F, which possess higher binding energy (Supplementary Fig. 17, Tables 2–5)40,41,42,43,44. The presence of metal ions coordinated with F leads to stronger electron absorption effect. This strong M-F bond interaction facilitates charge transfer from the metal to the matrix, creating an electron-enriched environment around adjacent C. Such an environment can appropriately regulate the adsorption of Li on q2D-cMOF. The C1s spectrum displays an asymmetric peak (Fig. 2j and Supplementary Fig. 18, Table 6). The emergence of C-O is probably attributed to the slight oxidation of carbon materials. The appearance of peaks corresponding to various fluorine-containing groups in q2D-FcMOF indicates an effective reaction between q2D-cMOF and F2 along with the transformation of conjugated sp2 hybrid C atoms into sp3 hybrid C atoms that bonded with F atoms. The F1s spectrum of q2D-FcMOF can be deconvoluted into semi-ionic C-F bonds (688.0 eV), covalent C-F bonds (689.1 eV) and metal-F bonds, reflecting the hybrid coexistence of ionic, semi-ionic and covalent F bonds, respectively (Fig. 2k and Supplementary Fig. 19, Table 7). The N1s spectrum of q2D-cZ8, q2D-cZ67, and q2D-cNiMOF can be deconvoluted into peaks corresponding to pyridinic N (398.2 eV), pyrrolic N (399.5 eV), and graphitic N (401.0 eV)45. Pyridinic nitrogen contributes the predominant component, aligning with the structure of the organic monomer used in the MOF synthesis (Supplementary Fig. 20, Table 8).

X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (XAFS) is utilized to investigate structural and coordination morphology46. The k absorption edge of q2D-cZ8 and q2D-FcZ8 lies between Zn and ZnO, indicating a mixed valence state of Zn elements between 0 and +2. The valence of fluorinated q2D-FcZ8 appears higher (Fig. 2l). The extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) illustrates substantial changes in the coordination environment of Zn after extensive fluoridation (Fig. 2m). The peaks of q2D-cZ8 at 1.6 Å and 2.2 Å correspond to the coordination peaks of Zn-O and Zn-Zn. The peak of q2D-FcZ8 about 1.7 Å relates to the coordination peak of Zn-F, confirming successful fluorination47,48. Wavelet transform (WT) contour map peak of q2D-cZ8 around 7 Å corresponds to the Zn-Zn coordination bond (Fig. 2n). Meanwhile, the peak in the WT contour map of q2D-FcZ8 around 9 Å corresponds to the Zn-F bond, providing additional proof that gas-phase fluoridation alters the coordination properties of Zn49.

Deposition-dissolution of q2D-FcMOF with lithium

Suspended droplets of q2D-FcMOF nanoparticles are cast onto Li to prepare q2D-FcMOF@Li. During solvent evaporation, the NPs assembled into a dense and uniform coating (Supplementary Fig. 21). To explore the interaction between Li+ and q2D-FcMOF, the chemical composition and structure of ASEI layer are determined by time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS)50. By comparing the TOF-SIMS of q2D-FcZ8@Li before and after 50 cycles, as sputtering time increases, the intensity of ZnF2, LiZn, C2HO, C2H, CF3, and CH groups in metal-organic framework outer layer gradually decreases. LiF and LiO groups in the inner inorganic layer gradually increase over time. Between 300 to 400 seconds, their intensities stabilize before eventually declining (Figs. 3a, b and Supplementary Fig. 22a). After 50 cycling, significant organic outer components like ZnF2, C2HO, C2H, CF3, and CH, along with inorganic components like LiF, are still observable, indicating the stability of the ASEI (Supplementary Figs. 22b, 23). XPS depth analysis of q2D-FcZ8@Li is conducted to scrutinize the composition of ASEI in detail (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 24a)51. Prior to Ar+ sputtering, signals of Li-F and Li-O bonds in Li1s, C = C, semi-ionic and covalent C-F bonds in C1s, Zn-F, semi-ionic and covalent C-F bonds in F1s, and Zn2p are predominantly observed, confirming q2D-FcZ8 effective reaction with Li. As sputtering progresses, component proportions vary with the depth of sputtering etching. Initially (3–9 min), prominent signs of C = C, C-F, and Zn-F bonds are key components of the outer layer. With increased sputtering depth (12–15 min), the strength of the C-F bond decreases, while Li-F content sharply rises, and Zn signals gradually fade, indicating that inorganic LiF becomes the key component of inner SEI layer. In the late sputtering phase (18 min), the emergence of Li0 signals suggests that Ar+ has nearly penetrated the SEI layer, exposing fresh Li metal. This trend implies that double-layer ASEI main structural components are outer organometallic frame layer and inner inorganic LiF layer with a stronger affinity for Li. Element compositions of q2D-FcZ8@Li after 50 cycles (1 mA cm–2 @ 1 mAh cm–2) are also analyzed (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 24b). Before Ar+ sputtering, q2D-FcZ8@Li mainly comprises Li2S, derived from slight electrolyte decomposition, with weak signals of Li-O and signals of Li-F, Zn, and C-F. As sputtering progresses, signals of LiF, Zn, and C quickly recover. The Li-F signal notably surpasses Li-O at the 9th min, and Zn is consistently present, indicating that the double-layer ASEI remains intact with excellent cyclic and structural stability. In contrast, traditional SEI layers, composed of disorganized distributions of Li-O, LiF, and Li2S, are observed at all depths, with oxygenated organic components produced by severe electrolyte decomposition, generating the inevitably huge consumption of active Li (Supplementary Fig. 25). The details of each peak are in Supplementary Tables 9–19. The results demonstrate that the organometallic frame/inorganic LiF hybrid double-layer ASEI uniformly adheres to the Li surface, enhancing mechanical strength of the SEI layer. The outer layer provides uniform Li nucleation sites, enabling smooth and reversible Li movement. The F-rich inner layer acts as an exceptional electronic insulator, creating a strong e-blocking environment that inhibits side reactions and Li dendrite formation, effectively preventing electrolyte decomposition. LiF is also a Li+ conductor52, which can regulate the flux, facilitating rapid Li+ transfer. The structural stability of q2D-FcZ8@Li is further demonstrated by comparing XRD and Raman results before and after 50 cycles (Supplementary Figs. 26 and 27). Li deposition morphology is significantly influenced by varying energy barriers during nucleation and transport (Fig. 3e). After 4 h deposition at 1 mA cm–2, bare Li exhibits coarse, unevenly distributed Li dendrites and island-like Li structures on the surface. Under identical deposition conditions, q2D-FcZ8@Li maintains a smooth, dendrite-free surface post-deposition. The cross-sectional analysis revealed that the loose, porous layer on bare Li surface is 31 μm thick. In contrast, for q2D-FcZ8@Li, a dense Li layer is observed, with the Li metal surface thickness increasing by 20 μm. This dense deposit layer closely aligns with the theoretical Li thickness of 19.3 μm53 and supports a surface capacity of 4 mAh cm−2. At higher current densities (3 mA cm–2 and 5 mA cm–2), the quantity and size of dendrites increase, showing moss-like Li deposits with uneven edges and exposing severely damaged structures and dead Li. The absence of obvious dendrite growth on q2D-FcZ8@Li surfaces suggests that hybrid double-layer ASEI effectively inhibits Li dendrite. Based on the foregone electrodeposition model, the process of Li deposition and the evolution of Li+ concentration are simulated using the finite element method (Fig. 3f). Severe concentration polarization and irreversible depletion of Li+ occur in the Li deposition simulation behavior at 8 mA cm–2 for 120 min. Large dendrite Li growth starts at nucleation sites due to the tip effect, and the spontaneously formed fragile SEI layer with poor Li+ conduction ability causes an uneven electric field. The increase in the local concentration of Li+ near the deposition site is significantly driven by the accumulated negative charge, generating the formation of dead Li and capacity loss54. In contrast, Li deposition appears flat deposited on q2D-FcZ8@Li. Since the diffusion coefficient of the double-layer ASEI is significantly greater than the traditional spontaneous SEI, Li+ can be rapidly conducted during continuous plating/stripping to avoid excessive local Li+ concentrations and maintain a uniform electric field at the interface, achieving uniform deposition of Li+.

a 3D rendering of the TOF-SIMS of the double-layer ASEI on the q2D-FcZ8@Li before cycling under Cs+ sputtering. b The strength of each group of TOF-SIMS of the double-layer ASEI on the q2D-FcZ8@Li before 50th cycling under Cs+ sputtering. XPS spectra at various depths of the SEI on the Li deposition: Zn2p, C1s, F1s, and Li1s spectra of q2D-FcZ8@Li (c) before cycling, (d) after 50th cycling. e SEM image of surface morphology for bare Li and q2D-FcZ8 at different deposition rates (Scale bar of inset: 30 μm, current density in Fig. 3e4 is 1 mA cm−2). f Li+ concentration profiles and Li metal deposition of the (f1, f2) bare Li and (f3, f4) q2D-FcZ8 by finite element method simulation.

To investigate the interaction between Li+ and q2D-FcMOF, we conducted 7Li solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (ssNMR) to assess the chemical environment of 2D-FcMOF with dissolved LiTFSI (Supplementary Fig. 28). Li chemical shift changes notably upon the introduction of q2D-FcMOF, with a pronounced charge transfer moving from -3.1 ppm in LiTFSI to 0.8 ppm in q2D-FcZ8@LiTFSI. This significant shift is attributed to a reduction in the local electron cloud density of Li+ caused by q2D-FcMOF. Ionic transport behavior is explored by assessing the diffusivities of Li+ and TFSI− using pulsed field gradient nuclear magnetic resonance (PFG-NMR) spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 29). q2D-FcZ8 exhibits the highest diffusivity for both Li+ and TFSI−, as ionic conductivity is proportional to ion concentration and diffusivity according to the Einstein relation (Supplementary Fig. 30). This effectively enhances the ion conduction efficiency of Li+. FTIR spectra of q2D-FcMOF@LiTFSI further support these findings. LiTFSI displays three characteristic peaks: 1635 cm−1 for Li-N, 1200 cm−1 for C-F, and 1053 cm−1 for O = S = O55. Upon the introduction of q2D-FcMOF, C-F and O = S = O peaks in LiTFSI shift significantly to lower wavelengths, indicating that q2D-FcMOF uniquely influence LiTFSI dissociation and enhance Li+ dissolution (Supplementary Fig. 31).

The Evans method is used to measure polarization in a symmetrical Li | |Li cell at voltage of 10 mV (Supplementary Fig. 32). q2D-FcZ8@Li achieving the highest value (0.52). This is attributed to interparticle spaces in the MOF coating and the excellent lithiophilicity of Zn. The electrochemical performances of the Li | |Cu half-cells are demonstrated in Fig. 4a. The overpotentials of the Li | |Cu, q2D-FcZ8@Li | |Cu, q2D-FcZ67@Li | |Cu, q2D-FcU66@Li | |Cu, q2D-FcNiMOF@Li | |Cu and CFx@Li | |Cu cells are 31, 10, 11, 13, 12, and 21 mV (Supplementary Fig. 33). q2D-FcZ8@Li has the lowest Li deposition barrier and achieves a coulombic efficiency (CE) of 99.12% after 500 cycles. The CE of q2D-FcZ67@Li, q2D-FcU66@Li, and q2D-FcNiMOF@Li decreased to less than 95.0% after 461, 305, and 381 cycles, while CFx@Li and bare Li decreased to less than 95.0% after 270 and 142 cycles, revealing that the inorganic LiF layer can control the growth of Li dendrites to some extent, but the influence of the metal site and q2D carbon skeleton is more remarkable. Variations in metal nodes significantly influence the activity of metal sites on Li+, thereby affecting electrochemical performance. q2D-FcZ8@Li showed the lowest polarization voltage (38 mV) during the 50th cycle (Fig. 4b). The voltage profiles of q2D-FcZ8@Li | |Cu and q2D-FcZ67@Li | |Cu remained nearly unchanged across different cycles (Supplementary Fig. 34). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) revealed a more stable and lower impedance interface of q2D-FcZ8@Li (Supplementary Fig. 35). In contrast to the precarious interface of bare Li, the interface charge transfer resistance (Rct) of q2D-FcZ8@Li | |Cu remain stable over 100 cycles. When the deposition rate and capacity increased to 2 mAh cm–2 at 2 mA cm–2, q2D-FcZ8@Li | |Cu demonstrated an average CE of 98.72 % after 400 cycles, markedly superior to bare Li (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Figs. 37a, b). At even higher rates of 2 mAh cm–2 at 4 mA cm–2, q2D-FcZ8@Li | |Cu maintained the longest cycles and highest average CE of 98.33%, whereas CE of bare Li dropped to 85.0% after merely 41 cycles (Supplementary Figs. 36, 37c, d). q2D-FcZ8@Li | |Cu shows excellent properties using a standard carbonate electrolyte (Fig. 4d), achieving high CE of 97.88% after 300 cycles, due to the insulating LiF intermediate layer, which significantly avoid the side reactions between Li and the carbonate electrolyte. This suggests that the robust, lithiophilic, high Li+ flux ASEI can uniformly adsorb Li+ on the surface.

a Coulombic efficiency and Li nucleation overpotentials of asymmetric Li | |Cu cell in ether electrolytes with a capacity of 1 mAh cm−2 at 1 mA cm−2. b Voltage profiles of 50th Li plating/stripping in Fig. 4a. Coulombic efficiency of asymmetric Li | |Cu cell in (c) ether electrolytes with a capacity of 2 mAh cm−2 at 2 mA cm−2 (d) carbonate electrolytes with a capacity of 1 mAh cm−2 at 1 mA cm−2. e Galvanostatic cycling voltage profiles in symmetric cells with a capacity of 1 mAh cm−2 at 1 mA cm−2. f Rate performance of symmetric cells with capacity of 1 mAh cm−2 at different current density. g The “dead Li” content after 200 cycles with a capacity of 1 mAh cm−2 at 1 mA cm−2 is determined via TGC measurements. h The activation energy (Ea) is fitted based on Arrhenius equation.

Long-term cyclic stability and rate performance are assessed by Li | |Li symmetric cells (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 38). The symmetric cell with q2D-FcZ8@Li showed a low hysteretic voltage of 44 mV after 3600 h, indicating low and smooth polarization. Conversely, the hysteretic voltage of bare Li shows a trend of enlargement gradually, the hysteretic voltage increases reaching 88 mV after 800 h and the cell failure occurs after 1052 h. When the Li deposition capacity is raised to 2 mAh cm–2 at 10 mA cm–2 (Supplementary Fig. 39), the symmetric Li cell fails after 147 h. The rate performance of symmetric q2D-FcZ8@Li, q2D-FcZ67@Li, and bare Li is carried out under current densities ranging from 1 to 8 mA cm–2 with a capacity of 1 mAh cm–2 (Fig. 4f). q2D-FcZ8@Li presents inconspicuous hysteresis, with steady voltage polarization of 48, 98, 127, 191 mV at current densities of 1, 2, 4, 8 mA cm–2. When the current density returns to 1 mA cm–2, the hysteresis voltage reaches 53 mV. The symmetric q2D-FcZ67@Li also has the ability to cope with step changes in the rate current. In contrast, when the current density is returned to 1 mA cm–2, the bare Li has severe voltage polarization, and the polarization voltage increases by 36.13%. These results imply that the double-layer ASEI can improve the deposition behavior of Li+, which effectively disperses the current density in the battery. Adequate Li+ supplementation and continued transport activate the internal active site and prevent the intensification of polarization. To ascertain the distribution of “dead Li” and “SEI-Li+” during the long-term cycle, Li after 200 cycles is verified by titration gas chromatography (TGC) to assess the residue of active “reversible Li” (Fig. 4g)56. Compared to bare Li, q2D-FcZ8@Li and q2D-FcZ67@Li exhibite higher reversible capacities of 99.09% and 98.84%, and lower amounts of “dead Li” and “SEI-Li+.” This indicates that the double-layer ASEI effectively enhances active “reversible Li” in prolonged cycles and curbs side reactions. To assess the impact of the double-layer ASEI on charge transfer kinetics, symmetric bare Li, q2D-FcZ8@Li, and q2D-FcZ67@Li are evaluated using Tafel plots for exchange current density (Supplementary Fig. 40). q2D-FcZ8@Li displays an enhanced current density of 0.48 mA cm–2, which is 539.27% higher than bare Li, indicating sluggish kinetics in the latter. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) shows that q2D-FcZ8@Li and q2D-FcZ67@Li have higher current response values (Supplementary Fig. 41), reflecting improved electrochemical reaction kinetics with reduced Li nucleation barrier and low overpotential, while the high ionic conductivity accelerated Li+ transfer kinetics. The activation energy (Ea) for charge transport is calculated by fitting data to the Arrhenius equation57, based on electrochemical impedance spectra measured at various temperatures (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 42). Temperature-dependent EIS from 298.15 K to 338.15 K reveals that Ea values for q2D-FcZ8@Li and q2D-FcZ67@Li were 0.48 eV and 0.52 eV, respectively, lower than bare Li (0.58 eV), supporting the benefits of double-layer ASEI in stabilizing the Li/electrolyte interface and enhancing Li+ transport; thus, improving electrode stability and Li stripping/plating kinetics. To the best of our knowledge, the cycle stability and utilization rate of the q2D-FcZ8@Li anode are among the remarkable reported for Li anodes protected by various artificial layers (Supplementary Fig. 43, Supplementary Table 24).

To elucidate Li storage mechanism, Li | |q2D-FcZ8 is assembled to confirm whether q2D-FcMOF interacts with Li during cycling (Supplementary Fig. 44). When the voltage range is set to 0.5 to 3.0 V, the initial discharge of q2D-FcZ8 achieves specific capacity of 167.5 mAh g−1. During subsequent charge-discharge cycles, the specific capacity remains significantly lower than the first (~15 mAh g−1). Li reacts with q2D-FcZ8 to form LiF crystals during the first discharge cycle. Since LiF is highly resistant to electrochemical decomposition, requiring a decomposition voltage of 6.1V58, the capacity beyond the first cycle primarily arises from Li+ insertion into the MOF structure’s pores. This portion of the capacity is recyclable, as evidenced by the consistent specific discharge capacity after the second cycle. However, this capacity is notably low, suggesting it has minimal impact on the overall electrochemical process of q2D-FcZ8@Li. The Cyclic Voltammetry test results from Li | |q2D-Fc8@Li also supported our observations (Supplementary Fig. 45). Therefore, we propose that q2D-FcMOF reacts with Li+ on the surface only during the first cycle to form LiF, but this reaction is irreversible. It contributes to capacity only in the initial cycle. After the first cycle, q2D-FcZ8 is fully lithiated, with Li+ passing through the q2D-FcMOF passivation layer. The F in LiF remains unreacted with Li, and Li is deposited on the surface of anode. q2D-FcZ8 no longer has the capacity to store Li+. q2D-FcMOF serves solely as a passivation layer and does not participate in further electrochemical reactions.

Electrochemical performance of high-energy LMBs employing q2D-FcMOF

The q2D-FcMOF@Li is coupled with LFP cathode to assemble the LMB, evaluating its potential in full batteries (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 46). The q2D-FcZ8@Li | |LFP achieved excellent cycle performance with an initial capacity of 143.2 mAh g–1 at 1 C and maintains a capacity retention of 92.85% over 600 cycles with ultrahigh CE (99.71%). q2D-FcZ67@Li | |LFP cell provides an initial capacity of 140.8 mAh g−1 and maintains a capacity retention of 74.64% over 600 cycles with CE of 99.29%. In contrast, the specific capacity of Li | |LFP decreased to 100 mAh g–1 after 288 cycles (N/P = 5.19, E/C = 42 g Ah−1). Polarization comparisons of various electrodes at the 50th and 200th cycles (Supplementary Figs. 47, 48) show that q2D-FcZ8@Li | |LFP remains stable over long cycles, with minimal polarization increase, unlike Li | |LFP and CFx@Li | |LFP, which exhibit significant polarization increases after prolonged cycling. The practical application rate performance of q2D-FcZ8@Li | |LFP was demonstrated in Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 49, showing a high discharge capacity of 155.6 mAh g–1 at 0.1 C, and maintaining 115.7 mAh g–1 at a high rate of 5 C, with only a slight increase in voltage polarization (Supplementary Fig. 50). The Li | |LFP displayed a discharge capacity of 150.0 mAh g–1 at 0.1 C, but significantly decreased at 5 C (54.1 mAh g–1), aligning with the poor morphological evolution of Li deposition. In situ FTIR was utilized to monitor dynamic changes in electrolyte composition (Fig. 5c). As charging progressed, distinct double peaks emerged in 2300 ~ 2387 cm–1, associated with the -O - C = O group formed from electrolyte decomposition (Fig. 5d). The peak intensity eventually stabilized, indicating effective inhibition of electrolyte decomposition in subsequent electrochemical processes via the double-layer ASEI. CV curves are employed to confirm that SEI layer enhances the kinetics of Li+ transfer at the interface (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 51). Li | |LFP exhibits a pair of redox peaks corresponding to the Fe2+/Fe3+ redox couple. In comparison to bare Li, q2D-FcZ8@Li | |LFP displays a stronger redox peak and smaller voltage difference between the reduction peak and the oxidation peak (ΔV = 0.152 V). The galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT) is used to determine Li+ diffusion coefficients (DLi+) (Supplementary Fig. 52)59. Functional relationship between electrochemical DLi+ and voltage is calculated. DLi+ in q2D-FcZ8@Li | |LFP is greater than Li | |LFP, demonstrating that q2D-FcZ8@Li possesses better reaction kinetics and accelerates the diffusion of Li+.

a Long-term cycling performance of Li | |LFP at 1 C. b Rate performance of Li | |LFP. The in-situ FTIR spectra of the electrolyte of q2D-FcZ8@Li | |LFP (c) during the process of charge and discharge and (d) contour maps of the in-situ FTIR. e CV curves of Li | |LFP with a scan rate of 0.05 mV s−1. f Cycling performance of Li | |LFP at 1 C with high cathode mass loading and lean electrolyte. g Cycling performance of Li | |NCM811 at 0.5 C. h Li1s XPS spectra of air-exposed q2D-FcZ8@Li for different time periods. i The specific capacity of air-exposed q2D-FcZ8@Li and bare Li for different time periods. j EIS curves of symmetric cell of air-exposed q2D-FcZ8@Li and bare Li for different time periods, with enlargement in the inset.

To further examine the impact of cathode loading and electrolyte volume on cycle efficiency, cells are tested under conditions of high loading (~15 mg cm–2) with a low N/P ratio of 2.65 and lean electrolyte (E/C = 18 g Ah–1). q2D-FcZ8@Li | |LFP demonstrates 200 stable cycles, as depicted in Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 53, with capacity retention rates of 94.78%. Conversely, the capacity of bare Li decline rapidly after 88 cycles, with retention rate of only 5.26% after 100 cycles. When q2D-FcZ8@Li is paired with NCM811, q2D-FcZ8@Li | |NCM811 exhibites excellent electrochemical performance (Fig. 5g, Supplementary Fig. 54, N/P = 3.14, E/C = 26 g Ah−1). Over 150 cycles at 0.5 C, q2D-FcZ8@Li maintains initial capacity of 169.5 mAh g–1, capacity retention rate of 81.88%, and average CE of 99.17%.

Surface morphology of Li is analyzed using SEM paired with LFP and NCM811 after various cycle (Supplementary Fig. 55). After 20 cycles of Li | |LFP, numerous flat Li deposits formed on the surface, which is a characteristic shape of Li deposition in DOL/DME electrolyte. Due to irregular deposition and dissolution processes, a significant amount of loose Li also appeared. After 50 cycles, the amount of active flat Li decreased, with more loose Li becoming evident. After 200 cycles, the Li surface transformed into a porous and fluffy texture, with the absence of flat Li. This porous layer contains isolated “dead Li” and excess SEI, leading to low CE and increased internal resistance. After 20 cycles of the bare Li | |NCM811, numerous needle-like Li deposits appeared on the surface, which is a characteristic shape in ester electrolytes. After 100 cycles, the needle-like Li was no longer visible, with only irregularly distributed Li blocks observed. While under the protection of q2D-FcZ8, the Li surface remained smooth and dense, indicating a planar Li deposition process due to the organometallic framework/inorganic LiF protective layer.

Air stability of q2D-FcMOF protected lithium

The double-layer ASEI also contributes to preventing air penetration. Optical photographs presented in Supplementary Fig. 56 reveal the corrosion degree of q2D-FcZ8@Li and Li when exposed to air (average humidity ≈ 30.0%). XPS analysis illustrates that each peak of bare Li exposed to air underwent displacement and intensity changes to varying extents. Unprotected Li reacts with air to form LiOH, leading to a significant increase in oxygen and further reacting with N2 to form Li3N, while the composition of q2D-FcZ8@Li exhibits remarkable air stability (Fig. 5h and Supplementary Figs. 57–60, Tables 20–23). To thoroughly analyze oxidation process of q2D-FcZ8@Li, air stability is explored using in-situ XRD. Li surface remain unpolished. Supplementary Fig. 61 presents the results for bare Li and q2D-FcZ8@Li after 2 h of air exposure, with test conducted at 20 min intervals. After 2 h of exposure, alongside the Li diffraction peak (PDF No. 15-0401), a diffraction peak for LiOH (PDF No. 32-0564) emerged on the exposed bare Li, attributed to the reaction of H2O and O2 with Li in the environment. In contrast, q2D-FcZ8@Li remains unchanged. Both samples exhibit sharp diffraction peaks corresponding to Li. q2D-FcZ8@Li displays additional diffraction peaks for LiZn (PDF No. 03-0954), LiF (PDF No. 89-3610), and ZnF2 (PDF No. 01-0661). These peaks originate from the hybrid protective layer. The electrochemical properties of Li after air exposure are examined. Fig. 5i displays typical electrochemical stripping curves at 1 mA cm–2 for bare Li and q2D-FcZ8@Li. The initial specific capacity of bare Li was 3439.9 mAh g–1, which decreases to 2345.1 mAh g–1 after 1 h, indicating almost no electrochemical activity after 2 h. q2D-FcZ8@Li maintains an inherent specific capacity of 3274.3 mAh g–1 and a capacity retention rate of 91.69% after 2 h. The charge transfer resistance of q2D-FcZ8@Li increased from 79 to 223 Ω after 2 h of exposure to air, while bare Li increased from 113 to 2098 Ω (Fig. 5j). The symmetric Li is proposed in Supplementary Fig. 62, showing that bare Li-1h maintains cycle stability for only 231 h, q2D-FcZ8@Li-2h has cycle stably for 600 h. The capacity of Li-1h | |LFP significantly degraded, while q2D-FcZ8@Li-2h achieved stable 400 cycles with capacity retention rate of 85.51% (Supplementary Fig. 63). These results indicate that exposure to air generates abundant corrosion products, hindering electron and Li+ transport and reducing the capacity of Li. Unprotected Li is unable to effectively resist corrosion; thus, significantly increasing the risk of Li storage in an aerobic state, but the double-layer ASEI effectively serves as a barrier against air to prevent the reaction of active Li.

Adsorption energy and migration energy of q2D-FcMOF for lithium

To delve further into the remarkable Li plating/stripping cycle performance, DFT calculations are performed to determine adsorption energy and migration energy. The maximal adsorption energy exhibits by q2D-FcMOF at various adsorption sites is negative, suggesting thermodynamically favorable Li atom adsorption by q2D-FcMOF (Supplementary Fig. 64). Notably, q2D-FcZ8 (−10.29 eV) demonstrates the greatest adsorption energy, indicative of its high Li+ affinity. Building on prior research, it is hypothesized that greater Li adsorption energy correlates with improved LMB performance60. Differential charge density of q2D-FcMOF with adsorbed Li is calculated to elucidate the adsorption behavior (Fig. 6a, atomic coordinates are provided in the Source Data file). Before Li atom adsorption, the robust interaction between metal and fluorine atoms leads to charge transfer from metal to fluorine atoms or to the carbon framework linked to fluorine, creating an electron-rich environment. Subsequent to Li atom adsorption, noticeable charge transfer occurs among fluorine, metal, and Li atom on the carbon skeleton, confirming that the strategic incorporation of lithiophilic metal sites can furnish a potent adsorption center. This facilitates selective Li atom deposition at lithiophilic sites, effectively regulating local electron cloud distribution, and enhancing adsorption, nucleation, and growth of Li. The migration pathway and diffusion barrier of Li+ mirror the conduction capability within the double-layer ASEI61,62. The phase diagram of Li and Zn demonstrates excellent surface fusion between these two elements. Li-Zn alloy provide a relatively high Li+ diffusion coefficient, ensuring rapid charge transfer kinetics63, while the surface fusion of Li with Co, Zr and Ni is worse than Zn. The diffusion trajectory of Li+ on and perpendicular to the ASEI layer surface is computed to align with the actual diffusion path (Figs. 6b–e and Supplementary Figs. 65–70, atomic coordinates are provided in the Source Data file). Li+ migrates from one stable adsorption site on the surface to another, surmounting a diffusion energy barrier in the process. Among these, q2D-FcZ8 exhibits the lowest migration energy barrier in both surface and vertical directions. These findings indicate that q2D-FcZ8 significantly enhances Li+ migration. The combination of lower adsorption energy and a diminished diffusion barrier demonstrates q2D-FcZ8 ASEI pivotal role in establishing rapid and unobstructed Li+ channels. Consequently, both experimental and theoretical studies affirm that the design of an organometallic framework/inorganic LiF hybrid double-layer.ASEI is an efficacious approach to boosting the electrochemical performance of LMB.

Discussion

We demonstrate the development of q2D fluorinated MOF for the construction of ASEI results in a robust and stable interfacial protective double-layer on the Li surface. The inner layer composed of inorganic LiF effectively conducts Li+ and blocks electron transport, while the outer layer enriched with lithiophilic metal ion clusters provides ample and uniform nucleation sites. This arrangement leads to a distribution of Li+ around the metal active sites, further preventing the excessive growth of the SEI during long-term cycling. q2D-FcZ8 modified Li anode exhibits the highest Li adsorption energy, demonstrates superior electrochemical performance. q2D-FcZ8@Li | |Cu half-cell shows the lowest Li deposition barrier and achieves a CE of 99.12% after 500 cycles. The symmetrical q2D-FcZ8@Li battery maintains a cycle life exceeding 3600 h and displays low and stable polarization potential (44 mV). Furthermore, q2D-FcZ8@Li retains 99.09% of “reversible Li” after 200 cycles according to TGC analysis. q2D-FcZ8@Li | |LFP shows stable long-cycle and rate performance, with an initial capacity of 143.2 mAh g–1 and maintaining 600 stable cycles with a capacity retention rate of 90.12% and average CE of 99.71%. Additionally, q2D-FcZ8@Li positively impacts the protection of lithium against air corrosion. DFT calculations reveal that the lower adsorption energy and reduced diffusion barrier of q2D-FcZ8 ASEI are crucial in forming rapid transfer and unobstructed Li+ channels.

Methods

Materials

Zinc acetate dihydrate (Zn(CH3COO)2·2H2O, 99.0%), 2-methylimidazole (C4H6N2, 99.0%), cobalt acetate tetrahydrate (Co(CH3COO)2·4H2O, 99.0%), zirconium tetrachloride (ZrCl4, 99.5%), terephthalic acid (C8H6O4, 99.0%), 4,4’-bipyridine (C10H8N2, 99.0%), nickel sulfate hexahydrate (NiSO4·6H2O, 99.9%), N,N-dimethylformamide (C3H7NO, DMF, 99.8%), pyridine (C5H5N, 99.8%) was purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Ar gas (99.99%), N2 gas (99.99%), F2 gas (F2:N2 = 1:4) were purchased from Vista Technology Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). N-methylpyrrolidone (C5H9NO, NMP, 99.9%), lithium electrode, ferrous lithium phosphate (LiFePO4, LFP, 99.0%), nickel cobalt manganese oxide (LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2, NCM811, 99.0%), lithium nitrate (LiNO3, 99.0%) was purchased from Kelud Chemical Technology Co., LTD. (Shanghai, China). Fluorinated graphite (CFx, 99.0%) was purchased from Zhongshan Photoelectric Materials Co. Ltd (Shandong, China). Unless otherwise noted, all reagents and solvents were obtained from commercial sources and used directly without further purification.

Synthesis of ZIF-8

1.50 g Zn(CH3COO)2·2H2O was dissolved in 25 mL of deionized water and slowly added to 25 mL of deionized water containing 5.60 g 2-methylimidazole, stirred for 2 min, left at room temperature for 4 h, centrifuged and collected samples, washed the product with water several times, and ZIF-8 crystals were obtained after drying.

Synthesis of ZIF-67

1.70 g Co(CH3COO)2·4H2O was dissolved in 25 mL of deionized water and slowly added to 25 mL of deionized water containing 5.60 g 2-methylimidazole, stirred for 2 min, left at room temperature for 4 h, centrifuged and collected samples, washed the product with water several times, and ZIF-67 crystals were obtained after drying.

Synthesis of UIO-66

0.31 g ZrCl4 and 0.23 g terephthalic acid were dissolved in 70 mL DMF successively, stirred for 2 min, sealed in Teflon hydrothermal synthesis reactor (capacity: 100 mL) at 120 °C for 24 h, cooled to room temperature, centrifuged and collected samples. After washing the product with with water, DMF and ethanol for several times, UIO-66 crystals were obtained after drying.

Synthesis of Ni-MOF

1.56 g 4,4’-bipyridine and 2.62 g NiSO4·6H2O were dissolved in 50 mL water, then 5 mL pyridine was dropped under stirring conditions, and 25 mL anhydrous ethanol was added. After the solution was continuously stirred for 5 min, it was sealed in a Teflon hydrothermal synthesis reactor (capacity: 100 mL) and reacted at 100 °C for 24 h. After cooling to room temperature, the green solid product was centrifuged to collect, washed with the product water and ethanol several times, and Ni-MOF crystals were collected after drying.

Synthesis of q2D-Z8

Prepared 500 mg ZIF-8 was dispersed into 50 mL deionized water, and then 10 mg ml−1 colloidal solution was obtained after ultrasonic treatment for 5 min. Transfer 20 mL colloidal solution into 50 mL beaker, then cover the mouth of the cup with plastic wrap to prevent boiling liquid nitrogen from splashing into the cup, and maintain the same pressure of beaker with atmospheric pressure by piercing the hole. Slowly immersed in liquid nitrogen for 5 min, after the water in the beaker condenses into ice, transfer the cup to the freeze-drying machine immediately, and freeze dry for 24 h to allow the ice to fully sublimate. The condensation temperature was set at −70 °C and the pressure was about 5 Pa. After lyophilization, the flake products were collected and labeled q2D-Z8. The synthesis of quasi-two-dimensional ZIF-67, UIO-66 and Ni-MOF was prepared by the same ice template method as q2D-Z8. The products were labeled q2D-Z67, q2D-U66, and q2D-NiMOF.

Synthesis of q2D-cZ8

q2D-Z8 precursor was placed in a porcelain boat, then placed in a quartz tube. This tube was inserted into a tubular furnace in Ar atmosphere (flow rate of 300 sccm), heated to 600 °C at a rate of 5 °C min−1, maintained at a constant temperature of 600 °C for 120 min, and cooled naturally to room temperature. q2D-Z67, q2D-U66 and q2D-NiMOF were used as the precursor in the preparation process of q2D-cZ67, q2D-cU66 and q2D-cNiMOF, respectively. The carbonization temperature, carbonization time and heating rate were the same as q2D-cZ8 sample.

Synthesis of q2D-FcZ8

The fluorination equipment includes custom-made Monel reactor to protect against F2 corrosion, temperature control equipment to observe the real-time temperature of the reaction, two absorption towers to absorb the exhaust gas and avoid pollution to the environment, gas flow meter to control the flow rate of F2 or N2. The gas not involved in the reaction was discharged to the atmosphere through the first absorption tower containing Soda lime (CaO, 75 wt%, NaOH, 3 wt%, KOH, 1 wt%, H2O, 20 wt%, Aladdin Reagent (China) Co., Ltd.) and the second absorption tower containing activated carbon (XFNANO Materials Tech Co., Ltd.). The fluorination of q2D-cZ8 samples proceeded through a custom-made Monel reactor. Before using the equipment, to remove residual fluorine in the reactor and pipeline, nitrogen was employed to purge for 30 min. After the purge, sealed sample in the reactor, and pumped down to a near-vacuum state (0.04 Torr). Then the reactor was heated to 120 °C. When reaching the set temperature, the reactor was filled with a mixture of F2 and N2 by volume ratio 1:4 gas to atmospheric pressure and the fluorination reaction lasted for 1 h. The fluorinated samples produced were labeled q2D-FcZ8. At the end of the reaction, N2 gas flow was filled into the reactor and pipeline to push out the fluorine gas, and the product was cooled in N2 to the ambient temperature and removed from the reactor. q2D-cZ67, q2D-cU66 and q2D-cNiMOF were used as carbon precursors in the preparation process of q2D-FcZ67, q2D-FcU66 and q2D-FcNiMOF, respectively, and the fluorination temperature and fluorination time were the same as that of q2D-FcZ8.

Synthesis of q2D-FcZ8@Li

50 mg q2D-FcZ8 NPs were dispersed in 5 mL DME by ultrasonic treatment for 5 min, and stirred overnight to form a uniform suspension. Then, the suspension is uniformly dropped on the surface of the Li metal, and the double-layer ASEI is formed by the interaction of q2D-FcZ8 and Li on the hot plate at 120 °C. The non-reactive q2D-FcZ8 is washed with DME after 12 h, and the DME is dried on the hot plate at 60 °C to obtain the q2D-FcZ8@Li anode.

Materials characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) measurements were performed with TESCAN MIRA field emission scanning electron microscope. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), high-annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and element mapping analysis were conducted on TF30 electron microscope operating at 200 kV. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra in the range of 4000-500 cm−1 were measured using an infrared spectrophotometer (FT/IR-300E; JASCO Corporation). X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra were measured using an X-ray area detector (D/Max-25; Rigaku) under Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å, 40 kV, and 40 mA) with a scanning range of 10° to 90°. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was performed using a spectrometer (Thermo Scientific K-Alpha+) with an Al anode source operated at 15 kV to analyze the chemical composition of the materials. Raman spectra (HORIBA LabRAM HR Evolution) were recorded using a charge-coupled multichannel detector. Specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution were determined using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller and Barrett-Joyner-Halenda methods (ASAP 2460 3.01; Micromeritics) at 120 °C. The adsorption gas N2 was tested at 77 K. The Zn K-edge were acquired in fluorescence mode using a Si (111) double-crystal monochromator and a 21 Ge-element detector for fluorescent X-rays in Spring-8. The EXAFS raw data were then background-subtracted, normalized and Fourier transformed by the standard procedures with the IFEFFIT package. Ar ion sputtering was employed as the XPS depth profile analysis for 0 ~ 18 min, Li was deposited (capacity of 1 mAh cm−2) directly on the Li foil at a current density of 1 mA cm−2 after 50 cycles. The group types of SEI layer at different depths were analyzed by Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) under vacuum conditions using PHI nanoTOFII time-of-flight simulation instrument. Titration Gas Chromatography (TGC) was used to determine the amount of “dead Li0” in a battery after 200 cycles. Liquid-state Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy experiments were conducted on Agilent DD2-600. The Li signal of LiCl at 0 ppm was used as the reference of 7Li chemical shift. Solid-state NMR experiments were conducted on Bruker Avance III HD 400 (9.4 T) spectrometers using a 3.2 mm magic-angle spinning probes.

Electrochemical measurements

All cells assembly takes place in an Ar-filled glove box (H2O < 0.01 ppm, O2 < 0.01 ppm). The electrodes were punched into disks with a diameter of 15 mm and the separators were punched into discs with a diameter of 19 mm for coin cell (CR2032) assembly. A 40 μm-thickness lithium sheets without surface oxide layers were directly applied as the anode. The average CE is obtained by dividing the sum CE of each cycle by the cycle number. Li | |Cu cells using 1 M LiTFSI DOL/DME (volume ratio: 1:1, 40 μL) with 2% LiNO3 or 1 M LiPF6 EC/DEC/DMC (volume ratio: 1:1:1, 40 μL) as electrolyte assemble the coin battery were measured at different current densities (1 ~ 4 mA cm−2). Li | |Li cells using 1 M LiTFSI DOL/DME (volume ratio: 1:1, 40 μL) with 2% LiNO3 as electrolyte assemble coin battery were measured at different current densities (1 ~ 10 mA cm−2). LFP, super P and PVDF are mixed with a mass ratio of 8:1:1, dispersed in NMP to form a homogenous slurry, which was then cast on an Al foil and vacuum dried at 80 °C for 12 h. Li | |LFP cells using 1 M LiTFSI DOL/DME (volume ratio: 1:1) with 2% LiNO3 as the electrolyte were cycling at different specific currents (1 C = 170 mA g−1) and in the voltage range of 2.5 to 4.2 V (vs. Li/Li+). NCM811, super P and PVDF are mixed with a mass ratio of 96:2:2, dispersed in NMP to form a homogenous slurry, which was then cast on an Al foil and vacuum dried at 80 °C for 12 h. Li | |NCM811 using 1 M LiPF6 EC/DEC/DMC (volume ratio: 1:1:1) as the electrolyte were cycling at different specific currents (1 C = 188 mA g−1) and in the voltage range of 3.0 to 4.3 V (vs. Li/Li+). Before the full cell cycling tests, all cells proceeded with a five-cycle formation at 0.05 C for pre-activation. Li+ transference number (tLi+) was estimated using a Li | |Li symmetric cell by Evans method, which is evaluated by potentiostatic polarization and ElS technique. The initial current (I0) and final steady-state current (Iss) were obtained by a constant polarization potential (V, 10 mV). The data acquisition was fixed at the rate of 5000 point/sec in the beginning stage in order to record the I0 more precisely. An AC impedance test (20 kHz to 1 Hz, 10 mV) was performed to obtain the initial interfacial resistance (Rint0) and the steady-state interfacial resistance (Rinss). Cells were cycled in a thermostat at room temperature (25 °C). The tLi+ can be calculated by the equation:

Density functional theory calculations

Calculation of adsorption energy and transition state of lithium were performed within the framework of the density functional theory (DFT) as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Software Package (VASP 5.3.5) code within the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) generalized gradient approximation and the projected augmented wave (PAW) methodS1-S3. The cutoff energy for the plane-wave basis set was set to 400 eV. Monkhorst-Pack (MP) grids was used to sample the Brillouin zone of the surface unit cell for the optimization of FcMOF and the structure of FcMOF after adsorption of Li atomsS4. The FcMOF model was optimized with 3 × 3 × 3 Monkhorst-Pack grid. The convergence criterion for the electronic self-consistent iteration and force was set to 10−5 eV and 0.01 eV/Å, respectivelyS5. Define the adsorption energy of lithium atom as:

where Epre is the energy before the material adsorbed lithium atom, Etotal is the system energy after the material adsorbed lithium atoms, ELi is the energy of an isolated Li atom, and n is the number of adsorbed Li atoms. Based on the adsorption energy calculation formula, when E < 0 indicates successful adsorption.

Simulation of lithium-ion distribution

The concentration evolution of Li+ during charge and discharge and the deposition behavior of Li metal are very complicated. In this chapter, a simplified model is carried out by COMSOL Multiphysics 5.5. The electrochemical deposition process of Li metal was simulated by current distribution model. The Nernst-Planck equation is used to describe the mass transfer and charge conservation of active Li+ in the electrolyte. The mass transfer of ions is considered, including diffusion due to concentration gradient and electromigration due to electricity. A square area of 20.0 × 20.0 μm2 was established as the study area, and the current density was set to 8 mA cm−2. Three Li metal deposition sites are set uniform on the surface of Li metal, and the deposition sites are set as columnar bulges. Assume that the ionic diffusion coefficients of Li+ and anion in the electrolyte are 5 × 10−7 cm2 s−1 and 2 × 10−6 cm2 s−1, respectivelyS6. For the unmodified Li electrode, a spontaneous SEI layer with a thickness of 0.5 μm is introduced, and for q2D-FcMOF@Li, a double-layer structure of 0.5 μm and 4.5 μm is introduced in place of the SEI layer, and the initial concentration of Li+ is set to 1 mol L−1.

Growth mechanism of q2D-MOF via freeze-drying

First, MOF NPs is dispersed in deionized water. Under the condition of rapid vaporization of liquid nitrogen, the growing polycrystalline ice gradually repels MOF NPs into the liquid phase. Due to the nucleation sites of the ice are dispersed and the presence of extremely thin spaces at the interface between ice and water creates a capillary effect. Driven by the pressure difference, MOF NPs is absorbed into the channel between adjacent ice crystals, resulting in abundant MOF NPs dispersed in the liquid phase between the ice sheets. The channel between the ice crystals shrinks as the ice template continues to grow and MOF NPs is confined to the channel between the ice crystals. In the final stage, the size of the channel is only comparable to MOF NPs, and the shape of the aggregated MOF NPs is limited by the shape of the channel, forming the shape of the ice sheet is a two-dimensional gap. After the MOF NPs was removed from the ice template under the condition of freeze-drying, the MOF NPs was extruded with each other, and finally the form of MOF NPS with quasi-two-dimensional ordered superstructure was obtained.

Data availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Manthiram, A., Yu, X. & Wang, S. Lithium battery chemistries enabled by solid-state electrolytes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 1 (2017).

Zeng, X. et al. Commercialization of lithium battery technologies for electric vehicles. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1900161 (2019).

Cao, D. et al. Lithium dendrite in all-solid-state batteries: growth mechanisms, suppression strategies, and characterizations. Matter 3, 57 (2020).

Ji, X. et al. Solid‐state electrolyte design for lithium dendrite suppression. Adv. Mater. 32, 2002741 (2020).

Goodenough, J. B. & Kim, Y. Challenges for rechargeable Li batteries. Chem. Mater. 22, 587 (2010).

Raj, V. et al. Direct correlation between void formation and lithium dendrite growth in solid-state electrolytes with interlayers. Nat. Mater. 21, 1050 (2022).

Han, K. et al. A 2D ultrathin nanopatterned interlayer to suppress lithium dendrite growth in high-energy lithium‐metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 34, 2203992 (2022).

Cheng, X. et al. Toward safe lithium metal anode in rechargeable batteries: a review. Chem. Rev. 117, 10403 (2017).

Wan, H. et al. Critical interphase overpotential as a lithium dendrite-suppression criterion for all-solid-state lithium battery design. Nat. Energy 8, 473 (2023).

Zhai, P. et al. Interface engineering for lithium metal anodes in liquid electrolyte. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001257 (2020).

Adenusi, H. et al. Lithium batteries and the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI)-progress and outlook. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2203307 (2023).

Wan, M. et al. Mechanical rolling formation of interpenetrated lithium metal/lithium tin alloy foil for ultrahigh-rate battery anode. Nat. Commun. 11, 829 (2020).

Krauskopf, T. et al. Diffusion limitation of lithium metal and Li-Mg alloy anodes on LLZO type solid electrolytes as a function of temperature and pressure. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1902568 (2019).

Lin, Y. X. et al. Connecting the irreversible capacity loss in Li-ion batteries with the electronic insulating properties of solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) components. J. Power Sources 309, 221 (2016).

Mo, F. et al. Inside or outside: origin of lithium dendrite formation of all solid‐state electrolytes. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1902123 (2019).

Lu, Y., Tu, Z. & Archer, L. A. Stable lithium electrodeposition in liquid and nanoporous solid electrolyte. Nat. Mater. 13, 961 (2014).

Gao, Y. et al. Polymer-inorganic solid-electrolyte interphase for stable lithium metal batteries under lean electrolyte conditions. Nat. Mater. 18, 384 (2019).

Chen, H. et al. Creating new battery configuration associated with the functions of primary and rechargeable lithium metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2003746 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Highly stable lithium metal batteries enabled by regulating the solvation of lithium ions in nonaqueous electrolytes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 5301 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Self-assembled monolayers direct a LiF-rich interphase toward long-life lithium metal batteries. Science 375, 739 (2022).

Ju, Z. et al. Biomacromolecules enabled dendrite-free lithium metal battery and its origin revealed by cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Commun. 11, 488 (2020).

Cui, C. et al. A highly reversible, dendrite‐free lithium metal anode enabled by a lithium‐fluoride‐enriched interphase. Adv. Mater. 32, 1906427 (2020).

Jamaluddin, A. et al. Fluorinated graphene as a dual-functional anode to achieve dendrite-free and high-performance lithium metal batteries. Carbon 197, 141 (2022).

Gan, H. et al. Coupling a 3D lithophilic skeleton with a fluorine-enriched interface to enable stable lithium metal anode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 37162 (2021).

Xia, S. et al. Highly stable and ultrahigh-rate Li metal anode enabled by fluorinated carbon fibers. Small 17, 2006002 (2020).

Xiao, J. et al. Ultra‐high fluorine enhanced homogeneous nucleation of lithium metal on stepped carbon nanosheets with abundant edge sites. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 12 (2022).

Senthil, C. et al. Robust, ultrasmooth fluorinated lithium metal interphase feasible via lithiophilic graphene quantum dots for dendrite-less batteries. Small 18, 2200919 (2022).

Chen, T. et al. Ultra-low concentration electrolyte enabling LiF‐rich SEI and dense plating/stripping processes for lithium metal batteries. Adv. Sci. 9, 2203216 (2022).

Shadike, Z. et al. Identification of LiH and nanocrystalline LiF in the solid-electrolyte interphase of lithium metal anodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 549 (2021).

James, S. Metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 32, 276 (2003).

Zhou, H., Long, J. & Yaghi, O. Introduction to metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 112, 673 (2012).

Mao, Y. et al. Foldable interpenetrated metal-organic frameworks/carbon nanotubes thin film for lithium-sulfur batteries. Nat. Commun. 8, 14628 (2017).

Chiochan, P. et al. A metal organic framework derived solid electrolyte for lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001285 (2020).

Kodama, K. et al. Magnetic superstructure in the two-dimensional quantum antiferromagnet SrCu2(BO3)2. Science 298, 395 (2002).

Aubert, T. et al. Two-dimensional superstructures of silica cages. Adv. Mater. 32, 1908362 (2020).

Avci, C. et al. Self-assembly of polyhedral metal-organic framework particles into three-dimensional ordered superstructures. Nat. Chem. 10, 78 (2018).

Modak, P. & Modak, B. Electronic structure investigation of intrinsic and extrinsic defects in LiF. Comput. Mater. Sci. 202, 110977 (2022).

Chen, C. et al. Highly conductive, lightweight, low-tortuosity carbon frameworks as ultrathick 3D current collectors. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1700595 (2017).

Ferrari, A. C. et al. Raman spectrum of graphene and graphene layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 187401 (2006).

Gu, X. et al. Fluorination of ZIF-67 framework templated Prussian blue analogue nano-box for efficient electrochemical oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 403, 126371 (2021).

Xu, X. et al. Fluorinated Ni-O-C heterogeneous catalyst for efficient urea-assisted hydrogen production. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2303986 (2023).

Shrestha, N. K. et al. Electrochemically assisted self-assembling of ZnF2-ZnO nanospheres: formation of hierarchical thin porous films. ECS Electrochem. Lett. 3, E1 (2014).

Zhang, N. et al. Partially fluorinated UiO-66-NH2 (Zr): Positive effect of the fluorine moiety on the adsorption capacity for environmental pollutants of metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Eng. J. 448, 137467 (2022).

Kong, L. et al. Defective nano-structure regulating C–F bond for lithium/fluorinated carbon batteries with dual high-performance. Nano Energy 104, 107905 (2022).

Sun, L. et al. Interface‐Structure‐Modulated CuF2/CFx Composites for High‐Performance Lithium Primary Batteries. Energy Environ. Mater 6, e12323 (2023).

Rehr, J. & Albers, R. Theoretical approaches to X-ray absorption fine structure. Rev. Mod. Phys. 72, 621 (2000).

Ren, F. et al. Formation of Zn-ZnO core-shell nanoclusters by Zn/F sequential ion implantation. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 39, 488 (2006).

Zhu, W. et al. Enhanced CO2 electroreduction on neighboring Zn/Co monomers by electronic effect. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 12664 (2020).

Zhu, J. et al. EXAFS study of 20GaF3-15InF3-20CdF2-15ZnF2-20PbF2-10SnF2 glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 354, 1182 (2008).

Yu, P. et al. Co nanoislands rooted on Co-N-C nanosheets as efficient oxygen electrocatalyst for Zn-air batteries. Adv. Mater. 31, 1901666 (2019).

Ma, C., Xu, F. & Song, T. Dual-layered interfacial evolution of lithium metal anode: SEI analysis via TOF-SIMS technology. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 14, 20197 (2022).

Wang, M. et al. Tailoring lithium deposition via an SEI-functionalized membrane derived from LiF decorated layered carbon structure. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1802912 (2019).

Berg, E. J. et al. Rechargeable batteries: grasping for the limits of chemistry. J. Electrochem. Soc. 162, A2468 (2015).

An, J. et al. Self‐expanding ion‐transport channels on anodes for fast‐charging lithium‐ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 134, e202113313 (2022).

Cui, Y. et al. Improved performance using a plasticized polymer electrolyte for quasi-solid state dye-sensitized solar cells. Electrochim. Acta 74, 194–200 (2012).

Yu, W. et al. Degradation and speciation of Li salts during XPS analysis for battery research. ACS Energy Lett 7, 3270 (2022).

Xiang, Y. et al. Quantitatively analyzing the failure processes of rechargeable Li metal batteries. Sci. Adv. 7, 3423 (2021).

Sun, Z. et al. Oxygen-free cell formation process obtaining LiF protected electrodes for improved stability in lithium-oxygen batteries. Energy Storage Mater 23, 670–677 (2019).

Yuan, X. et al. Ultrafast deposition of faceted lithium polyhedra by outpacing SEI formation. Nature 620, 86–91 (2023).

Tian, D. et al. MoN supported on graphene as a bifunctional interlayer for advanced Li‐S batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1901940 (2019).

Ma, T. et al. Optimize lithium deposition at low temperature by weakly solvating power solvent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 134, 202207927 (2022).

Gao, Y. et al. Low-temperature and high-rate-charging lithium metal batteries enabled by an electrochemically active monolayer-regulated interface. Nat. Energy 5, 534 (2020).

Pelton, A. D. The Li-Zn (lithium-zinc) system. J. Phase Equilibria 12, 42–45 (1991).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by National Key R&D Program of China (no. 2023YFC2411901), the State Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 52130303), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 51973152, 51973119, 52103093, and 52173078), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52327802).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.K. and W.F. designed this study. L.K. carried out the characterization and all the electrochemical measurements. C.P., Z.Z., J.X. and Y.Z. helped in the gas phase fluorination of quasi-two-dimensional MOF materials. L.K. and Y.L. wrote the manuscript with contributions from other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Peiyuan Guan, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kong, L., Li, Y., Peng, C. et al. Achieving burst Li+ channels via quasi-two-dimensional fluorinated metal-organic framework modulating functionalized interface. Nat Commun 16, 1885 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57106-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57106-z

This article is cited by

-

A Critical Review on Sorption-Induced Deformation in Nanoporous Materials: Experiments, Theories and Simulations

Acta Mechanica Solida Sinica (2026)