Abstract

Water oxidation is the key reaction in natural and artificial photosyntheses but is kinetically and thermodynamically sluggish. Extensive efforts have been made to develop artificial systems comparable to the natural system. However, constructing a molecular system based on ubiquitous metal ions with high performance in aqueous media similar to a natural system, remains challenging. In this study, inspired by nature, we successfully achieve highly efficient water oxidation in aqueous media. By electrochemical polymerisation of a pentanuclear iron complex bearing carbazole moieties, we successfully integrate two essential features of the natural system: catalytic centre composed of ubiquitous metal ions and charge transporting site. The resulting material catalyses water oxidation with a Faradaic efficiency of up to 99% in aqueous media. Our results provide a strategy to develop catalytic systems for water oxidation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The oxidation of water to dioxygen (2H2O → O2 + 4H+ + 4e−) is crucial for supplying the protons and electrons necessary for chemical energy production in natural and artificial photosyntheses1,2,3,4,5,6. In natural photosynthesis, water oxidation proceeds at an enzyme called photosystem II (PSII)7,8,9,10. The catalytic centre of PSII, namely, the oxygen-evolving complex (OEC), is composed of earth-abundant metal ions, Mn and Ca, and achieves the reaction efficiently in vivo (aqueous media)11,12,13. A natural water oxidation system contains the following three key elements: (i) the catalytic centre is composed of metal ions that are abundant on Earth, (ii) the reaction is performed in aqueous media, and (iii) its catalytic performance is high.

Inspired by this natural system, extensive efforts have been devoted to the development of artificial molecular catalysts for water oxidation14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Ruthenium complexes have been widely studied as artificial water oxidation catalysts from the fundamental understanding of reaction mechanism23,24,25 to the creation of catalytic systems towards the future application26,27,28, and several ruthenium-based complexes and systems have exhibited excellent catalytic activity even in aqueous media (zone I in Fig. 1a)16,17,29. However, ruthenium ions are not necessarily suitable for potential large-scale practical applications because of the limited supply and high cost of the element. In this context, special attention has recently been paid to the construction of catalysts using earth-abundant metal ions, such as Mn, Fe, Co, and Cu30,31. Iron is an ideal metal ion which can be incorporated into catalytic systems for water oxidation because it has the highest content among the transition metals in the Earth’s crust. Although several iron-complex-based catalysts operate in aqueous media (zone II in Fig. 1a)32,33,34 or exhibit high performance (zone III)35,36, the development of molecule-based catalytic system for water oxidation with high catalytic performance in water oxidation reactions in aqueous media (zone IV) remains a challenge.

In this study, we successfully developed a high-performance iron-complex-based catalytic system for water oxidation in aqueous media. A newly designed multinuclear iron complex was electrochemically polymerised to obtain a polymer-based material, and we demonstrated its higher electrocatalytic activity and stability for water oxidation in aqueous media (Fig. 1b) compared to existing iron-based catalysts. Additionally, we investigated the effect of the incorporation of charge-transport sites around the multinuclear catalytic centre in catalysis. This study offers a strategy for obtaining highly efficient artificial water-oxidation systems based on iron complexes that can operate in aqueous media.

Results and discussion

Our study began by extracting the key factors that make the natural enzyme (PSII) an excellent catalytic system for water oxidation. In PSII, water oxidation is catalysed by OEC. The OEC contains an Mn4O5Ca cluster as the catalytic centre, which is surrounded by amino acid residues. The Mn4O5Ca cluster efficiently oxidises water to dioxygen11,13,37,38, and the surrounding amino acid residues promote the transfer of charges required for water oxidation7,9,10,39. Consequently, highly efficient water oxidation under mild conditions was achieved in aqueous media. Based on these considerations, we anticipated that the following structural features of PSII are essential: a multinuclear metal complex as a catalytically active site and amino acid residues surrounding the catalytic centre as charge-transporting sites (Fig. 2a).

a Schematic representation of the natural water oxidation system. b Schematic of the artificial catalytic system developed in this study for water oxidation. c Strategy for obtaining our targeted catalytic systems. Electrochemical polymerisation of a pentanuclear iron complex bearing carbazole moieties (Fe5-PCz) can afford polymer-based catalytic material, which has multinuclear active sites surrounded by charge-transporting sites.

In this study, we designed a catalytic system for water oxidation (Fig. 2b). Our system is composed of multinuclear active sites surrounded by charge-transporting sites. We used a pentanuclear iron scaffold composed of five metal ions and six 3,5-bis(2-pyridyl)pyrazole (Hbpp) ligands ([Fe5(μ3-O)(bpp)6]3+, Fe5) as the active centre. Our previous study has demonstrated that Fe5 exhibits high efficiency in catalysing the water oxidation reaction35. Biscarbazoles, which can be formed by the electrochemical dimerisation of carbazoles40,41, were selected as charge-transporting sites. Our group demonstrated42,43,44 that the charge-transporting ability of biscarbazoles can be obtained even after their introduction into metal complexes. Therefore, by the electrochemical polymerisation of a pentanuclear iron complex bearing carbazole moieties (Fe5-PCz; Fig. 2c, left), the targeted catalytic system, which contains catalytic centres surrounded by charge-transporting sites, can be fabricated (Fig. 2c, right).

We synthesised Fe5-PCz, the precursor of our targeted catalytic system, according to Supplementary Fig. 1, as shown in the Supplementary Information (SI). Initially, we synthesised Br-Hbpp (2) via the bromination of Hbpp by modifying a previously reported procedure45 (yield: 94%), followed by benzyl protection of the amino group in the pyrazole ring to afford Br-bpp-Bn (3) (yield: 79%). Subsequently, we prepared PhCz-bpp-Bn (4) by reacting 4-(9H-carbazol-9-yl) phenylboronic acid pinacol ester (Cz-Ph-B(pin)) with 3 via Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling (yield: 90%). Finally, we synthesised the desired ligand, PhCz-Hbpp (5), by deprotecting the benzyl group of 4 (yield: 80%). All synthesised organic compounds were characterised using 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy. Compound 5 was then reacted with 3.0 eq. of Fe(ClO4)2·6H2O in the presence of aq. NaOH (1.0 M, 1.0 eq.) in N,N-dimethyl formamide (DMF) at 140 °C for 30 min in a microwave oven. The crude product was purified by alumina column chromatography and recrystallised from t-butyl methyl ether (t-BuOMe) and acetonitrile (MeCN) to yield the desired complex [Fe5(μ3-O)(PhCz-bpp)6](ClO4)3 (Fe5-PCz(ClO4)3) in 25% yield. The resulting complex was identified using electron spray ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-TOF-MS, Supplementary Fig. 2), UV–Vis absorption spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 3), elemental analysis, and single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

Single crystals of Fe5-PCz(ClO4)3 suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction measurements were obtained by vapor diffusion of t-BuOMe into an MeCN solution of Fe5-PCz(ClO4)3 in a refrigerator. The X-ray crystallographic data for the complex are shown in Fig. 3a, b, and Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 1. The asymmetric unit of the I-4/3 d crystal of Fe5-PCz(ClO4)3 is composed of one-third of the cationic penta-iron complex and one \({{{{\rm{ClO}}}}_{4}}^{-}\) anion (Supplementary Fig. 4). Fe5-PCz has quasi-D3 symmetry and consists of a triangular core wrapped by two [Fe(μ-PhCz-bpp)3] units (Fig. 3a, b). The two metal ions at the apical positions (Feapi) are hexacoordinates with a distorted octahedral geometry, whereas the three metal ions in the triangular core (Fetri) are pentacoordinates with a distorted trigonal bipyramidal geometry. The pentanuclear core structure of Fe5-PCz is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. The bond distances between Feapi and the coordinated nitrogen atoms of PhCz-bpp (L) ligands (d(Feapi–NL)), Fetri and the coordinated nitrogen atoms of L (d(Fetri–NL)), Fetri, and a µ-oxo bridging ligand (d(Fetri–Ooxo)) are 1.952(5)–1.999(6) Å, 2.101(5)‒2.110 (6) Å, and 1.873(4) Å, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). These values are not significantly different from those of the parent Fe5 values of 1.963(3)‒2.018(3) Å, 2.089(5)‒2.127 (6) Å, and 1.918(0) Å, respectively (Supplementary Table 2).

a ORTEP drawing of the structure of cationic moiety of Fe5-PCz(ClO4)3 with 30% probability (side view, left), schematic of Fe5-PCz highlighting the pentanuclear core structure and one out of six PhCz-bpp− ligands (middle), and schematic of Fe5-PCz highlighting the pentanuclear core structure and the carbazole moieties (right). b ORTEP drawing of the structure of cationic moiety of Fe5-PCz(ClO4)3 with 30% probability (top view). Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. O: red, C: grey, N: cyan, Fe: green. c Cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of 0.2 mM solutions of Fe5-PCz and Fe5 in γ-butyrolactone containing 0.1 M tetra-n-butylammonium perchlorate (TBAP) under Ar at a scan rate of 100 mVs−1. d Square wave voltammogram of Fe5-PCz in γ-butyrolactone containing 0.1 M TBAP under Ar at a scan rate of 50 mVs−1. Working electrode (WE): glassy carbon (GC), counter electrode (CE): Pt wire, reference electrode (RE): Ag/Ag+.

The redox behaviour of Fe5-PCz(ClO4)3 was investigated by electrochemical measurements in a γ-butyrolactone solution containing 0.1 M tetra-n-butylammonium perchlorate (TBAP). As shown in Fig. 3c, the complex exhibits one reversible reduction wave and two reversible oxidation waves at E1/2 = −0.39, 0.21, and 0.32 V (vs. ferrocene/ferrocenium (Fc/Fc+)), respectively. Moreover, in the square wave voltammetry (SWV) curve (Fig. 3d), an additional peak is observed at 0.75 V. These redox peaks were assigned to the sequential oxidation of iron ions in Fe5-PCz(ClO4)3 compared to its parent complex, Fe5 (Supplementary Table 3). These results demonstrated that the pentanuclear core moiety of Fe5-PCz exhibited a redox behaviour similar to that of Fe5.

Subsequently, electrochemical polymerisation of Fe5-PCz(ClO4)3 was performed in a dichloromethane solution of TBAP (0.1 M). In cyclic voltammograms (CVs) performed with repeated potential sweep between −0.13 and 0.82 V (vs. Fc/Fc+) (Fig. 4a), two peaks corresponding to one-electron oxidation processes are observed approximately at 0.2 and 0.3 V. Additionally, a peak indicative of the multi-electron transfer process was observed in the range of 0.7–0.8 V in the forward scan of cycle 1. The former peaks were attributed to the oxidation of the iron centres of Fe5-PCz (vide supra). The latter peak was assigned to the oxidation of the carbazole moieties to undergo its dimerisation reaction26. In the first reverse scan, an additional new redox peak was observed at ~0.5 V, indicating the formation of biscarbazole moieties41,43. Furthermore, in subsequent scans, the intensity of the peaks attributed to the oxidation of iron ions and biscarbazole moieties increased, supporting the growth of the polymer on the surface of the electrode. These results indicated that the carbazole moieties of Fe5-PCz dimerised under electrochemical conditions while maintaining the pentanuclear iron structure to form a polymer-based material (poly-Fe5-PCz). After the CV measurements, the SWV curve of poly-Fe5-PCz was obtained using a freshly prepared butyrolactone solution of TBAP (0.1 M). As shown in Fig. 4c, the redox potentials of poly-Fe5-PCz are almost identical to those of Fe5-PCz, demonstrating the electrochemical polymerisation of Fe5-PCz to poly-Fe5-PCz while maintaining its pentanuclear iron structure.

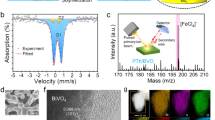

a CVs of a 0.2 mM solution of Fe5-PCz in dichloromethane containing 0.1 M TBAP under Ar at a scan of 100 mVs−1. WE: glassy carbon (GC); CE: Pt wire; RE: Ag/Ag+. CV scans are initiated from the open-circuit potential. b UV–Vis–NIR absorption spectra of ITO electrodes electrolysed at 1.17 V vs. Fc/Fc+ for 15–60 s in a 0.2 mM MeCN solution of Fe5-PCz containing 0.1 M TBAP. Photographs of the ITO electrodes after electrolysis (inset). c Square wave voltammograms of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC (red line) and Fe5-PCz (grey dotted line). Measurements were performed in γ-butyrolactone containing 0.1 M TBAP under Ar at a scan rate of 50 mVs−1. WE: GC, CE: Pt wire, RE: Ag/Ag+. d Fe L3-edge soft X-ray absorption spectra of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC (red line) and Fe5-PCz (grey dotted line).

Several measurements were performed to further characterise poly-Fe5-PCz. For the UV–Vis–NIR absorption spectroscopy measurement of poly-Fe5-PCz, a transparent electrode (ITO plate) as the working electrode (WE) was immersed into a 0.2 mM solution of Fe5-PCz(PF6)3 in an MeCN solution containing 0.1 M TBAP, and a constant potential (1.17 V vs. Fc/Fc+) was applied for 15–60 s. Subsequently, the UV–Vis–NIR absorption spectra of the obtained film (poly-Fe5-PCz@ITO) are measured (Fig. 4b). In all cases, bands centred at approximately 420 and 800 nm were observed, and their intensities gradually increased with increasing electrolysis time. The absorption peak at approximately 420 nm is attributed to the oxidised biscarbazole units, and the 800 nm bands can be attributed to the intervalence charge-transfer transitions of mixed-valence biscarbazole units in the case of Robin–Day class II systems or charge resonance in the case of Robin–Day class III systems30,46. This result supports the idea that the carbazole moieties of Fe5-PCz were dimerised by electrochemical oxidation to afford a polymer with a biscarbazole backbone.

Next, FTIR spectral analysis of poly-Fe5-PCz is performed (Supplementary Fig. 6). The IR absorption spectrum of the ITO electrode after polymerisation (poly-Fe5-PCz@ITO) exhibited several characteristic peaks of Fe5-PCz(ClO4)3. In addition, for poly-Fe5-PCz, a strong absorption band originating from \({{{{\rm{ClO}}}}_{4}}^{-}\) was observed at 1100 cm−1 47, which was included in the structure to compensate for the positive charge of the pentanuclear iron structure. Both spectra showed several common vibrational peaks, including pyrazole C=N vibration (1600 cm−1)48, pyridine ring stretching bands (1600–1350 cm−1), and pyridine C–H out-of-plane modes (800–750 cm−1)49. Moreover, a newly generated peak attributable to the vibrational bands of the C–H bonds of the biscarbazole ring is observed at 815 cm−1 in poly-Fe5-PCz (Supplementary Fig. 7)50. These results strongly supported the formation of a polymer with pentanuclear iron and biscarbazole moieties.

Furthermore, poly-Fe5-PCz formed on a glassy carbon (GC) electrode (poly-Fe5-PCz@GC; for details on the preparation of the film, see the SI) was analysed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements (Supplementary Figs. 8–11). The SEM and TEM images, and an XRD pattern of the polymer exhibits a flat amorphous structure, indicating the formation of a homogeneous film. In the EDX spectrum, a peak attributable to chlorine is detected alongside iron and nitrogen, implying the incorporation of \({{{{\rm{ClO}}}}_{4}}^{-}\) within the polymer. Finally, we conducted soft X-ray absorption spectrometry (SXAS) to obtain detailed information on the chemical state of poly-Fe5-PCz. It should be noted that SXAS spectra by the total electron yield (TEY) mode were measured for the analysis of the polymer because this method is sensitive to surface. As shown in Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 12, the Fe L3-edge SXAS spectrum of poly-Fe5-PCz is similar to that of Fe5-PCz, indicating that the pentanuclear structure of Fe5-PCz is successfully preserved in poly-Fe5-PCz. Collectively, the formation of the targeted polymer structure, which composed of pentanuclear iron complexes and biscarbazole moieties, in poly-Fe5-PCz was confirmed.

Subsequently, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed to examine the charge-transfer ability of poly-Fe5-PCz. Measurements were performed on a bare GC electrode, poly-Fe5-PCz@GC, and a GC electrode modified with a dispersion of the parent iron complex, Fe5, in an ion-conducting polymer, Nafion®, (Nafion-Fe5@GC, for details on the preparation of Nafion-Fe5@GC, see the “Methods” section) in a buffer solution at pH 9.0. Figure 5a shows the EIS spectra measured at a potential of 2.05 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE). The diameter of the semicircle in the Nyquist plot was the smallest for poly-Fe5-PCz@GC, followed by Nafion-Fe5@GC and bare GC. The charge-transfer resistance (RCT) values obtained by fitting the equivalent circuit are 63.1, 545.1, and 1911 Ω for poly-Fe5-PCz@GC, Nafion-Fe5@GC, and bare GC, respectively (Supplementary Table 4). The RCT value for poly-Fe5-PCz@GC was only 3.3% of that for bare GC and 11.6 % of that for Nafion-Fe5@GC. These results indicated that the conductivity of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC was higher than that of Nafion-Fe5@GC, which confirmed the importance of biscarbazole moieties as charge transporters.

a Nyquist plots of bare GC (black), Nafion-Fe5@GC (blue), and poly-Fe5-PCz@GC (red). Measurements are performed in 0.2 M borate buffer (pH = 9.0) under an Ar atmosphere. Applied potential: 2.05 V vs. RHE and measurement range: 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz. The equivalent circuit used to fit the data (inset). b CVs of, poly-Fe5-PCz@GC (red line) Nafion-Fe5@GC (blue line), and bare GC (black line) electrodes in 0.2 M borate buffer solutions (pH = 9.0). Measurements are performed under Ar at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1. c Charge–time plots of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC (red line), Nafion-Fe5@GC (blue line), and bare GC (black line) electrodes in 0.2 M borate buffer solutions (pH = 9.0) under an Ar atmosphere. Applied potential: 2.05 V vs. RHE. d Results of controlled potential electrolysis (CPE) of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC in 0.2 M borate buffer solutions (pH = 9.0) under an Ar atmosphere at various applied potentials. e Charge–time plots of the recyclability tests of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC. For each cycle, CPE is performed for 1 h at 2.05 V vs. RHE in 0.2 M borate buffer solutions (pH = 9.0) under an Ar atmosphere. f Results of recyclability tests for poly-Fe5-PCz@GC.

Encouraged by these results, we investigated the electrocatalytic activity of poly-Fe5-PCz in water oxidation. We performed CV measurements on the poly-Fe5-PCz@GC, Nafion-Fe5@GC, and bare GC electrodes in a buffer solution at pH 9.0 (Fig. 5b). In the CV curve of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC, an irreversible current was observed at approximately 1.80 V (vs. RHE), indicating that poly-Fe5-PCz exhibited catalytic activity for water oxidation. The intensity of the catalytic current of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC is larger than that observed for Nafion-Fe5@GC (Fig. 5b, red line), indicating a significant enhancement in the catalytic activity of our system after the incorporation of charge-transporting sites around the catalytic centre. Controlled potential electrolysis (CPE) of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC was performed to quantify the products of catalytic reaction (Supplementary Fig. 13). After the electrolysis of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC at 2.05 V (vs. RHE), 6.51 C of charge is passed, generating 16.6 µmol of O2 as the major product (the gas produced is detected by gas chromatography, Fig. 5c, and Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Table 5). The maximum Faradaic efficiency was determined to be 98.6%, based on a four-electron process. This high Faradaic efficiency is found to be well maintained even when the applied potentials for the CPE experiments are decreased (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Table 6). Moreover, a high Faradaic efficiency of 99 % was achieved at 1.85 V (vs. RHE). The stability of the system was confirmed via long-term electrolysis. During 4 h of electrolysis at 2.05 V (vs. RHE), the current is passed continuously (Supplementary Fig. 15), generating O2 with a Faradaic efficiency of 97.1% (Supplementary Table 7). Furthermore, the coating of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC by Nafion could increase the mechanical strength of the material, resulting in the stable formation of O2 more than 12 h (Supplementary Figs. 16, 17 and Supplementary Table 8). In addition, we confirmed that poly-Fe5-PCz@GC maintained its catalytic activity up to five times during the recycling experiments (Fig. 5e, f, Supplementary Fig. 18, and Supplementary Table 9). Isotope-labelling experiments using 18O-labelled water, H218O (97 %) were performed by applying 2.05 V (vs. RHE) for 1 h, and gaseous phase was analysed using GC–MS. The result of the experiment verifies the formation of 18O2 as the major product (Supplementary Fig. 19). Moreover, the ratio of 18O2 to 18O16O was in good agreement with theoretical values (Exp. 18O2:18O16O = 100:6.61, theor. 18O2:18O16O = 100:6.1). Therefore, the origin of the oxygen atoms in the evolved dioxygen was confirmed to be water in the catalysis mediated by poly-Fe5-PCz. These results demonstrated that poly-Fe5-PCz@GC is a robust electrocatalyst for water oxidation and can operate in aqueous media. Notably, the catalytic activity is almost completely suppressed under identical experimental conditions when Nafion-Fe5@GC is used (Fig. 5c, blue). Note that the polymer without Fe5 moieties also cannot catalyse water oxidation efficiently (Supplementary Figs. 20, 21 and Supplementary Table 10). These results, together with the EIS data, demonstrate that the interplay between the pentanuclear iron catalytic centres and charge-transporting biscarbazole sites enhances the catalytic activity for electrochemical water oxidation in aqueous media.

Subsequently, we conducted several experiments to confirm the stability of poly-Fe5-PCz. First, we performed CPE experiments and UV–Vis absorption spectroscopy to confirm no dissolution of catalytically active species to solution phase from the polymer material on the surface of the electrode during electrolysis. The analysis of the buffer solution used for the CPE of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC revealed that no dissolution of catalytically active species occurs during the electrolysis, and the heterogeneous material on the surface of the electrode is catalytically active (Supplementary Figs. 22, 23 and Supplementary Table 11). Second, SXAS and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) of poly-Fe5-PCz after the catalysis were measured. Supplementary Fig. 24 shows the Fe L2,3-edge SXAS spectrum of poly-Fe5-PCz before and after the catalysis. These two spectra are in good agreement with each other, suggesting that the oxidation states and chemical environments of the iron centres are retained even after the electrolysis. Therefore, these results clearly demonstrate that the pentanuclear iron structure is preserved during the catalysis. We also measured the SXAS of Fe2O3 and confirmed no transformation of poly-Fe5-PCz to Fe2O3. In XPS spectra of poly-Fe5-PCz before and after the catalysis (Supplementary Fig. 25), the peaks corresponding to Fe 2p3/2 and Fe 2p1/2 remained unchanged. This result also demonstrates the retention of the pentanuclear iron structure during the catalysis. Finally, we have investigated the catalytic activity of Fe2O3 under identical conditions (Fe2O3@GC in a borate buffer solution under Ar atmosphere. Applied potential: 2.05 V vs. RHE). As a result, it was confirmed that catalytic activity of Fe2O3 is substantially lower than those of poly-Fe5-PCz (Supplementary Fig. 26 and Supplementary Table 12). These results clearly demonstrate that the catalytically active species in our system is not Fe2O3 but pentanuclear iron complex, and this pentanuclear structure is sufficiently stable during the catalysis. Note that the possible reaction mechanism for water oxidation mediated by poly-Fe5-PCz probably proceed via four-step one-electron oxidation of the pentanuclear iron core followed by the insertion of a water molecule, as suggested by UV–Vis spectroelectrochemical measurements (Supplementary Figs. 27 and 28).

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of our system, the turnover number (TON) and turnover frequency (TOF) were calculated as follows: first, the surface concentration of the catalytically active sites in poly-Fe5-PCz@GC is calculated using Eq. (1)51.

where Ip, n, F, Γ, A, R, T, and v represent the peak current, number of electrons, Faraday’s constant, surface concentration, surface area, gas constant, absolute temperature, and scan rate, respectively.

CV measurements of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC were performed by varying the scan rates in the range of 30‒70 mV s−1. The peak current corresponding to the oxidation of the iron centre is plotted against scan rates (Supplementary Fig. 29), and the concentration of active species on the surface is estimated to be 1.41 × 10−10 mol cm−2. ICP-MS measurements of the polymer supported that a comparable amount of iron ions is contained in the polymer (Supplementary Table 13). Additionally, the TON and TOF values were determined using Eqs. (2) and (3), where 10.4 × 10−6 mol is the molar amount of evolved dioxygen detected in the CPE experiment, Γ is the surface concentration of the catalytically active sites, A is the surface area of the WE, and t is the electrolysis time (for details, see the SI (P. S40‒S42)).

The maximum TON value of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC for water oxidation reached 1.27 × 105 (4 h), which corresponds to a TOF value of 26.8 ± 1.2 s−1.

Finally, we compared the performance of our catalytic system, poly-Fe5-PCz@GC, with that of other iron-complex-based catalytic systems for water oxidation in aqueous media52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60. Figure 6a shows that the TON value of our system is the highest among the relevant systems, suggesting its high stability. Furthermore, the TOF of the proposed system is the highest class (Fig. 6b). Notably, the TOF value is the highest among those of the relevant systems (Fe1–Fe5 in Fig. 6c), where the TOF values were determined based on the results of CPE and not CV. This result clearly demonstrates the excellent performance of our system in terms of reaction rate. Collectively, our study developed an iron-complex-based catalytic system for water oxidation, which can operate in aqueous media with high stability and reaction rate.

Comparison of a turnover number and b turnover frequency values of our system with other iron-complex-based catalytic systems for water oxidation which can operate in aqueous media. Filled circles indicate TOF values determined by CPE, blank circles and square denote TOF values determined by CV, and a dotted circle denotes a TOF values determined by foot-of-the-wave analysis (FOWA). c Structures of our catalysts and relevant iron-complex-based catalysts52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60. Poly-Fe5-PCz and Fe1–Fe6: heterogeneous systems. Fe7–Fe9: homogeneous systems. Details are shown in Supplementary Fig. 30, and Supplementary Tables 14 and 15.

In conclusion, we have succeeded in developing a high-performance iron-complex-based catalytic system for water oxidation which operates in aqueous media. The key to our success was the development of a polymer-based catalytic system, poly-Fe5-PCz, which satisfied the following two key elements of the natural enzyme PSII: (i) the multinuclear catalytic centre and (ii) the charge-transporting moieties surrounding the catalytic centre. poly-Fe5-PCz was fabricated on an electrode by the electrochemical polymerisation of the precursor complex, Fe5-PCz. The material was fully characterised using CV, UV–Vis–NIR absorption spectroscopy, IR spectroscopy, SEM, EDX, and SXAS. The electrocatalytic activity of poly-Fe5-PCz for the water oxidation reaction was analysed using various electrochemical experiments, including EIS, CV, and CPE, and this material was confirmed to catalyse the water oxidation reaction with higher catalytic activity than its parent complex, Fe5, in aqueous media. Furthermore, poly-Fe5-PCz exhibited TON and TOF values for water oxidation of 1.27 × 105 (4 h) and 26.8 ± 1.2 s−1, respectively. These values were the highest class among those reported for other iron-complex-based catalytic systems in aqueous media. This study provides a new strategy for obtaining high-performance catalytic systems for water oxidation based on ubiquitous metal ions.

Methods

Synthesis of the pentanuclear iron complex

Synthesis of Br-Hbpp (2)

To a solution of 3,5-bis(2-pyridyl)pyrazole (1) (888 mg, 4.0 mmol) in CHCl3 (40 mL), a solution of bromine (0.6 mL, 12.0 mmol) in aq. Na2CO3 (1 M, 40 mL) as added at 0–5 °C and stirred for 30 min at 0–5 °C. Subsequently, aq. NaOH (1 M) was added until decolourisation occurred, and the organic phase was separated. The aqueous phase was extracted using CHCl3 (3 × 30 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and filtered. The mixture was concentrated and washed with hexane to obtain the target compound Br-Hbpp (2) as cream yellow solid (1.13 g, 94%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) = 8.75 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 8.17–8.08 (m, J = 7.8 Hz, 4H), 7.45 (dd, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) = 149.3, 137.0, 123.4, 121.8, and 90.4.

Synthesis of Br-bpp-Bn (3)

Br-Hbpp (2) (700 mg, 2.3 mmol) and NaH (380 mg, 9.5 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous DMF (15 mL) under an Ar atmosphere. The mixture was heated at 120 °C until the colour turned red. Benzylbromide (BrBn) (0.6 mL, 4.8 mmol) was added to the above reaction mixture and heated at 120 °C for 16 h. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was neutralised using aq. HCl (0.2 M), followed by addition of water (10 mL). The products were extracted with diethyl ether (3 × 20 mL) and the combined organic layers were washed with brine (50 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and filtered. The mixture was concentrated to afford crude oil, which was purified by silica gel column chromatography (eluent: EtOAc/hexane = 1/5) to yield Br-bpp-Bn (3) as a light-yellow powder (720 mg, 79%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) = 8.77 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 8.01 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.78–7.73 (m, 2H), 7.61 (d, J = 7.9, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.27–7.34 (m, 2H), 7.16–7.14 (m, 3H), 6.98–7.01 (m, 2H), 5.77 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) = 151.3, 149.7, 149.6, 148.0, 147.6, 141.0, 136.7, 136.5, 136.3, 128.3, 127.5, 127.4, 125.7, 123.5, 122.8, 93.4, and 55.2. Elemental analysis calculated (%) for Br-bpp-Bn, C20H15N4Br: C, 61.39; H, 3.86; N, 14.32. Found: C, 61.51; H, 3.74; N, 14.33.

Synthesis of PhCz-bpp-Bn (4)

In a Schlenk flask, Br-bpp-Bn (3) (200 mg, 0.51 mmol), 4-(9H-carbazol-9-yl) phenylboronic acid pinacol ester (230 mg, 0.62 mmol), and Cs2CO3 (500 mg, 1.53 mmol) were dissolved in dehydrated toluene (15 mL). Nitrogen was bubbled into the mixture for 10 min, followed by the addition of Pd(dppf)Cl2·CH2Cl2 (20.8 mg, 5 mol%). The mixture was heated at 100 °C for 3 h under Ar atmosphere. After cooling to room temperature, the undissolved materials were removed by filtration using Celite and washed with CHCl3. The mixture was concentrated, and the obtained oil was purified by silica gel column chromatography (eluent: EtOAc/acetone/hexane 1/1/5) to obtain PhCz-bpp-Bn (4) as light-yellow oil (254 mg, 90.1%). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ (ppm) = 8.76 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 8.66 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (dd, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.67–7.63 (m, 1H), 7.50–7.54 (m, 2H), 7.39–7.41 (m, 8H), 7.23–7.38 (m, 2H), 7.17–7.22 (m, 5H), 7.15 (dd, J = 7.6, 2.2 Hz, 2H), 6.97 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.78 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) = 152.5, 149.8, 149.7, 148.5, 148.1, 140.7, 140.6, 137.2, 136.1, 132.2, 132.1, 128.4, 127.6, 127,4 126.5, 125.9, 123.4, 123.3, 123.0, 122.4, 120.5, 120.3, 119.9, and 109.8. Elemental analysis calculated (%) for PhCz-bpp-Bn, C38H27N5B: C, 82.44; H, 4.92; N, 12.65. Found: C, 82.67; H, 4.70; N, 12.51.

Synthesis of PhCz-Hbpp (5)

A solution of Cz-Ph-bpp-Bn (4) (254 mg, 0.46 mmol) and NaOtBu (442 mg, 4.6 mmol) was heated in dehydrated DMSO (10 mL) at 50 °C for 30 min under oxygen bubbling. The reaction was quenched using aq. HCl (0.2 M), followed by the addition of water (10 mL). The products were extracted with CHCl3 (3 × 20 mL), and the combined organic layers were washed with water (2 × 50 mL) and brine (50 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and filtered. The mixture was concentrated, and the resulting powder was washed with diethyl ether to obtain the target compound PhCz-Hbpp 5 as pale yellow powder (173 mg, 80.4%). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ (ppm) = 8.65 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 8.18 (d, J = 8.0, Hz, 2H), 7.62 (m, 6H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.46 (td, J = 7.6, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 7.30–7.35 (m, 4H), 7.21 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) = 150.1, 149.6, 140.7, 137.0, 132.8, 132.3, 126.0, 123.5, 122.7, 121.7, 120.4, 120.1, and 109.7. Elemental analysis calculated (%) for PhCz-Hbpp, C31H21N5: C, 80.32; H, 4.57; N, 15.11. Found: C, 80.31; H, 4.57; N, 15.11.

Synthesis of Fe5-PCz(ClO4)3 (6)

To a solution of PhCz-Hbpp (5) (36 mg, 0.078 mmol) in deoxygenated DMF (2 mL) in a microwave tube, aq. NaOH (1 M) (0.09 mL, 0.090 mmol) and Fe(ClO4)2 (84 mg, 0.23 mmol) were added. The mixture was heated at 140 °C for 30 min in microwave. After the completion of reaction, the undissolved residue was removed via filtration. The filtrate was precipitated in sat. aq. NaClO4 to yield a brown precipitate, which was collected via filtration and washed with water and diethyl ether. The obtained precipitate was dissolved in MeCN and purified by column chromatography (alumina, activated ~75 μm (~200 mesh), eluent: MeOH/CHCl3 1/30). Recrystallisation from tert-butyl methyl ether (MTBE)/MeCN gave Fe5-PCz(ClO4)3 (6) as a deep-red crystal (18.0 mg, yield 40.7%). MS (ESI): m/z calculated for C186H120N30OFe5 ([M+]) 1023.5693 was 1023.6913. Elemental analysis calculated (%) for Fe5-PCz·(H2O)2·(MTBE)5, C211H184Cl3Fe5N30O20: C, 65.90; H, 4.82; N, 10.93. Found: C, 65.79; H, 4.94; N, 11.02.

Synthesis of Fe5(ClO4)3

Fe5(ClO4)3 was synthesised according to a previously described procedure35 with some modifications. NaOH aq. (0.1 M, 1.8 mL) was added to a solution of 3,5-bis(2-pyridyl)pyrazole (0.72 mmol, 160 mg) in methanol (6 mL). Subsequently, FeSO4·7H2O (0.60 mmol, 168 mg) was added to the reaction mixture and stirred at room temperature for a few minutes. The reaction mixture was filtered to remove the undissolved residues, and a few drops of saturated aqueous NaClO4 solution were added to the filtrate. The precipitate obtained was washed with water and diethyl ether. Recrystallisation from diethyl ether/acetonitrile afforded a deep-red solid (137 mg, yield 72%). Elemental analysis calculated for Fe5(ClO4)3 3H2O: C78H60Cl3Fe5N24O16: C, 47.43; H, 3.06; N, 17.02%. Found: C, 47.55; H 2.88; N 17.02.

Preparation of polymer electrode

Preparation of poly-Fe5-PCz@GC

The poly-Fe5-PCz@GC modified GC plate (0.8 × 0.6 cm) was prepared using CV. Measurements were performed in a 0.19 mM solution of 6 in a dichloromethane solution containing TBAP (0.1 M) under Ar at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1. WE: GC plate; counter electrode (CE): Pt wire; reference electrode (RE): Ag/Ag+. CV scans were performed in the range of −0.14 to 0.82 V (vs. Fc/Fc+), 10 cycles and used as the working electrode.

Preparation of poly-Fe5-PCz@ITO for UV–Vis–NIR

The ITO electrode was immersed in a sat. Na2CO3 in MeOH and sonicated for 10 min. Prior to washing, the ITO electrode was washed with water and MeCN and dried in air. Compound 6 was precipitated in sat. aq. NaPF6 to obtain a brown precipitate, which was collected by filtration and washed with water and diethyl ether to obtain Fe5-PCz(PF6)3. The poly-Fe5-PCz@ITO-modified ITO plate (1.0 × 3.0 cm) was prepared by CPE. Measurements were performed in a 0.20 mM solution of Fe5-PCz(PF6)3 in a MeCN solution containing TBAP (0.1 M) under Ar at 1.17 V (vs. Fc/Fc+). WE: ITO plate; CE: Pt wire; RE: Ag/Ag+.

Preparation of poly-Fe5-PCz@ITO for FTIR

The poly-Fe5-PCz@ITO-modified ITO plate (1.0 × 2.0 cm) was prepared by CPE. Measurements were performed using 0.19 mM Fe5-PCz(ClO4)3 in a 0.1 M TBAP-dichloromethane solution electrolysed at 0.99 V (vs. Fc/Fc+). WE: modified ITO plate; CE: Pt wire; RE: Ag/Ag+.

Electrochemical studies

Electrochemical methods

Either a GC disc (ф = 0.3 cm, S = 0.07 cm2) or a GC plate (GCp; 25 mm × 0.8 mm × 0.18 mm) were used as the WE. The surface area of GCp dipped in the electrochemical solution was 1 cm2. A Pt wire was used as the CE, and Ag/Ag+ (TBAP/MeCN 0.1 M) Ag/AgCl (NaCl 3.0 M) was used as the RE. For the bulk electrolysis experiments, Ag/AgCl (NaCl 3.0 M) was used as the RE and a Pt mesh was used as the CE. In aqueous media, borate buffer solutions with ionic strengths (I) of 0.2 M. When required, the pH was adjusted using small amounts of an aqueous 1 M HCl solution. The RHE values reported in this study have been calculated using the formula: RHE = E + 0.059 pH + E0 (Ag/AgCl), where E is the working potential and E0 (Ag/AgCl) = 0.222 V at 25 °C. The overpotentials reported in this study were calculated using the formula E(overpotential) = RHE − 1.23 V. All potentials reported in the organic solvents were converted to ferrocene/ferrocenium (Fc/Fc+).

Preparation of Nafion-Fe5@GC

The Fe5-modified GC plate (Nafion-Fe5@GC) was prepared using the drop-casting method; 10 μL of Nafion dispersion in MeOH (0.05 wt%) was dropped on both sides of the GC plate and dried in an oven (120 °C) for a few minutes. Subsequently, 10 μL of 0.15 mM MeCN solution of Fe5(ClO4)3 was dropped on both sides of Nafion-coated GC plate and dried in an oven.

Electrochemical impedance spectrometry

The poly-Fe5-PCz modified GC plate (poly-Fe5-PCz@GC) was prepared using the same method as that used for the CPE experiments. For electrochemical impedance spectrometry, 0.2 M borate buffer solutions (pH = 9.0) were bubbled with Ar for 30 min before measurements. The electrochemical impedance spectra were recorded at a bias potential of 2.05 V (vs. RHE) in the measurement range of 0.1 Hz–100 kHz. The recorded data are fitted to the equivalent circuit, as shown in Fig. 5a (inset).

Controlled potential electrolysis

The poly-Fe5-PCz modified both sides of the GC plate was prepared using the CV technique (potential range: from −0.14 to 0.82 V vs. Fc/Fc+, 10 cycles) and used as the WE. The WE, CE, and RE were placed in an H-shaped two-compartment cell. Prior to the experiments, 0.2 M borate buffer solution (pH = 9.0) was bubbled with Ar for 30 min, and electrolysis was performed for 1 h. The evolved O2 was quantified using gas chromatography.

Isotope-labelling experiment

The 18O-labelling experiment was performed in a He-filled glove box. H218O (97%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. The poly-Fe5-PCz@GC modified GC plate (poly-Fe5-PCz@GC) was prepared using CV technique (0–1.0 V vs. Fc/Fc+, 15 cycles) and used as the WE. Pt wire and Ag/Ag+ were used as the CE and RE, respectively. The WE, CE, and RE were placed in a non-compartment cell. The buffer solution was prepared as follows: 1 mL of 0.2 M borate buffer was dried in vacuum. The resulting solid was transferred to a glove box and completely dissolved in H218O.

Electrolysis was performed for 1 h at 2.05 V (vs. RHE) in a borate buffer solution. The evolved O2 was then analysed using a Shimadzu GCMS-QP2020 (Rt®-Msieve 5 A (30 m, 0.53 mm ID, 50 μm df) He carrier gas, 40 °C).

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information files. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for the structure reported in this study has been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number 2326587 for Fe5-PCz(ClO4)3. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Meyer, T. J. Chemical approaches to artificial photosynthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 22, 163–170 (1989).

Lewis, N. S. & Nocera, D. G. Powering the planet: chemical challenges in solar energy utilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 15729–15735 (2006).

Berardi, S. et al. Molecular artificial photosynthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 7501–7519 (2014).

Zhang, B. & Sun, L. Artificial photosynthesis opportunities and challenges of molecular catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 2216–2264 (2019).

Ye, S. et al. Water oxidation catalysts for artificial photosynthesis. Adv. Mater. 31, 1902069–1902102 (2019).

Zhang, J. Z. & Reisner, E. Advancing photosystem II photoelectrochemistry for semi-artificial photosynthesis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 4, 6–21 (2020).

Ferreira, K. N., Iverson, T. M., Maghlaoui, K., Barber, J. & Iwata, S. Architecture of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving center. Science 303, 1831–1838 (2004).

McEvoy, J. P. & Brudvig, G. W. Water-splitting chemistry of photosystem II. Chem. Rev. 106, 4455–4483 (2006).

Umena, Y., Kawakami, K., Shen, J.-R. & Kamiya, N. Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 Å. Nature 473, 55–60 (2011).

Suga, M. et al. Light-induced structural changes and the site of O=O bond formation in PSII caught by XFEL. Nature 543, 131–135 (2017).

Dismukes, G. C. et al. Development of bioinspired Mn4O4− cubane water oxidation catalysts: lessons from photosynthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 1935–1943 (2009).

Suga, M. et al. An oxyl/oxo mechanism for oxygen–oxygen coupling in PSII revealed by an X-ray free-electron laser. Science 366, 334–338 (2019).

Bhowmick, A. et al. Structural evidence for intermediates during O2 formation in photosystem II. Nature 617, 629–636 (2023).

Blakemore, J. D., Crabtree, R. H. & Brudvig, G. W. Molecular catalysts for water oxidation. Chem. Rev. 115, 12974–13005 (2015).

Gersten, S. W., Samuels, G. J. & Meyer, T. J. Catalytic oxidation of water by an oxo-bridged ruthenium dimer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104, 4029–4030 (1982).

Duan, L. et al. A molecular ruthenium catalyst with water-oxidation activity comparable to that of photosystem II. Nat. Chem. 4, 418–423 (2012).

Noll, N., Krause, A. M., Beuerle, F. & Würthner, F. Enzyme-like water preorganization in a synthetic molecular cleft for homogeneous water oxidation catalysis. Nat. Catal. 5, 867–877 (2022).

Thomsen, J. M. et al. Electrochemical activation of Cp* iridium complexes for electrode-driven water-oxidation catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 13826–13834 (2014).

Ruan, G., Ghosh, P., Fridman, N. & Maayan, G. A di-copper-peptoid in a noninnocent borate buffer as a fast electrocatalyst for homogeneous water oxidation with low overpotential. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 10614–10623 (2021).

Wang, D. & Groves, J. T. Efficient water oxidation catalyzed by homogeneous cationic cobalt porphyrins with critical roles for the buffer base. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 15579–15584 (2013).

Li, X. et al. Identifying intermediates in electrocatalytic water oxidation with a manganese corrole complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 14613–14621 (2021).

Wang, D., Ghirlanda, G. & Allen, J. P. Water oxidation by a nickel–glycine catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 10198–10201 (2014).

Matheu, R., Ertem, M. Z., G.-Suriñach, C., Sala, X. & Llobet, A. Seven coordinated molecular ruthenium–water oxidation catalysts: a coordination chemistry journey. Chem. Rev. 119, 3453–3471 (2019).

Zhang, B. & Sun, L. Ru-bda: unique molecular water-oxidation catalysts with distortion induced open site and negatively charged ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 5565–5580 (2019).

Nguyen, Q. H., Ta, Q. T. H. & Tran, N. The mechanisms and topologies of Ru-based water oxidation catalysts: a comprehensive review. Ceram. Int. 49, 4030–4045 (2023).

Li, F. et al. Highly efficient oxidation of water by a molecular catalyst immobilized on carbon nanotubes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 12276–12279 (2014).

Hoque, M. A. et al. Water oxidation electrocatalysis using ruthenium coordination oligomers adsorbed on multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Nat. Chem. 12, 1060–1066 (2020).

Badiei, Y. M. et al. Single-site molecular ruthenium(II) water-oxidation catalysts grafted into a polymer-modified surface for improved stability and efficiency. ChemElectroChem 10, e202300028 (2023).

Matheu, R. et al. Intramolecular proton transfer boosts water oxidation catalyzed by a Ru complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 10786–10795 (2015).

Zhang, X.-P. et al. Transition metal-mediated O–O bond formation and activation in chemistry and biology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 4804–4811 (2021).

Kondo, M., Tatewaki, H. & Masaoka, S. Design of molecular water oxidation catalysts with earth-abundant metal ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 6790–6831 (2021).

Ellis, W. C., McDaniel, N. D., Bernhard, S. & Collins, T. J. Fast water oxidation using iron. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 10990–10991 (2010).

Fillol, J. L. et al. Efficient water oxidation catalysts based on readily available iron coordination complexes. Nat. Chem. 3, 807–813 (2011).

Codolà, Z. et al. Design of iron coordination complexes as highly active homogenous water oxidation catalysts by deuteration of oxidation-sensitive sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 323–333 (2019).

Okamura, M. et al. A pentanuclear iron catalyst designed for water oxidation. Nature 530, 465–468 (2016).

Praneeth, V. K. K. et al. Pentanuclear iron catalysts for water oxidation: substituents provide two routes to control onset potentials. Chem. Sci. 10, 4628–4639 (2019).

Meyer, T. J., Huynh, M. H. V. & Thorp, H. H. The possible role of proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) in water oxidation by photosystem II. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 5284–5304 (2007).

Suga, M. et al. Native structure of photosystem II at 1.95 Å resolution viewed by femtosecond X-ray pulses. Nature 517, 99–103 (2015).

Barber, J. Photosynthetic energy conversion: natural and artificial. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 185–196 (2009).

Karon, K. & Lapkowski, M. Carbazole electrochemistry: a short review. J. Sol. State Electrochem. 19, 2601–2610 (2015).

Kortekaas, L., Lancia, F., Steen, J. D. & Browne, W. R. Reversible charge trapping in bis-carbazole-diimide redox polymers with complete luminescence quenching enabling nondestructive read-out by resonance Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 14688–14702 (2017).

Iwami, H., Okamura, M., Kondo, M. & Masaoka, S. Electrochemical polymerization provides a function-integrated system for water oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 5965–5969 (2021).

Iwami, H., Kondo, M. & Masaoka, S. Fabrication of a function-integrated water oxidation catalyst through the electrochemical polymerization of ruthenium complexes. ChemElectroChem 9, 52–58 (2022).

Li, S., Iwami, H., Kondo, M. & Masaoka, S. Electrochemical polymerization of a carbazole-tethered cobalt phthalocyanine for electrocatalytic water oxidation. ChemNanoMat 8, e202200028 (2022).

Zhang, W., Liu, J., Jin, K. & Sun, L. Synthesis of some new 4-substituted-3,5-bis(2-pyridyl)-1H-pyrazole. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 43, 1669–1672 (2006).

Hsiao, S. H. & Lin, S. W. Electrochemical synthesis of electrochromic polycarbazole films from N-phenyl-3,6-bis(N-carbazolyl)carbazoles. Polym. Chem. 7, 198–211 (2016).

Chen, Y., Zhang, Y. & Zhao, L. ATR-FTIR spectroscopic studies on aqueous LiClO4, NaClO4, and Mg(ClO4)2 solutions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 6, 537–542 (2003).

Chithambarathanu, T., Umayorubaghan, V. & Krishnakumar, V. Vibrational analysis of some pyrazole derivatives. Indian J. Pure Appl. Phys. 41, 844–848 (2003).

Katritzky, A. R. & Phil, D. The infrared spectra of heteroaromatic compounds. Q. Rev. Chem. Soc. 13, 353–373 (1959).

Gu, C. et al. Controlled synthesis of conjugated microporous polymer films: versatile platforms for highly sensitive and label-free chemo- and biosensing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 4850–4855 (2014).

Bard, A. J. & Faulkner, L. R. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications 2nd edn (Wiley, Inc. Press, 2000).

Xie, L. et al. Enzyme-inspired iron porphyrins for improved electrocatalytic oxygen reduction and evolution reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 7576–7581 (2021).

Al-Zuraiji, S. M., Benkó, T., Frey, K., Kerner, Z. & Pap, J. S. Electrodeposition of Fe-complexes on oxide surfaces for efficient OER catalysis. Catalysts 11, 577 (2021).

Sinha, W., Mahammed, A., Fridman, N. & Gross, Z. Water oxidation catalysis by mono- and binuclear iron corroles. ACS Catal. 10, 3764–3772 (2020).

Al-Zuraiji, S. M. et al. An iron(III) complex with pincer ligand–catalytic water oxidation through controllable ligand exchange. Reactions 1, 16–36 (2020).

Al-Zuraiji, S. M. et al. Utilization of hydrophobic ligands for water-insoluble Fe(II) water oxidation catalysts – immobilization and characterization. J. Catal. 381, 615–625 (2020).

Wurster, B., Grumelli, D., Hotger, D., Gutzler, R. & Kern, K. Driving the oxygen evolution reaction by nonlinear cooperativity in bimetallic coordination catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 3623–3626 (2016).

Wang, Z.-Q., Wang, Z.-C., Zhan, S. & Ye, J.-S. A water-soluble iron electrocatalyst for water oxidation with high TOF. Appl. Catal. A 490, 128–132 (2015).

Zhang, H.-T., Su, X.-J., Xie, F., Liao, R.-Z. & Zhang, M.-T. Iron-catalyzed water oxidation: O–O bond formation via intramolecular oxo–oxo interaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 12467–12474 (2021).

Pattanayak, S. et al. Electrochemical formation of FeV(O) and mechanism of its reaction with water during O–O bond formation. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 3414–3424 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by KAKENHI grants [Grant Nos. 20K21209, 22K21348, 23H04903 (Green Catalysis Science), and 24H00464 (S.M.); 19H05777, 20H02754, 22K19086, 23H04628, and 24H02212 (Chemical Structure Reprogramming (SReP)) (M.K.); 24K23075 (K.K.); 20K15955 and 22K06525 (Y.S.); 23H02043 and 22H04507 (T.K.); and 22H05145 (H.K.)] from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. This study was supported by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) PRESTO [Grant No. JPMJPR20A4 (M.K.)] and JST CREST [Grant No. JPMJCR20B6 (S.M.)] and JST FOREST [Grant No. JPMJFR221S (M.K.) and JPMJFR223I (T.K.)]. Funding was received from the Izumi Science and Technology Foundation (M.K.), Mazda Foundation (M.K.), and Yazaki Memorial Foundation for Science and Technology (M.K.). K.K. is grateful for the Research Fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists (Grant No. 21J11068). Soft X-ray absorption measurements were performed at the Photon Factory BL-7A with the approval of the Photon Factory Program Advisory Committee (Proposal No. 2022G113) and at NanoTerasu BL07U. ICP-MS measurements were performed at Materials Analysis Division, Open Facility Center, Institute of Science Tokyo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M., H.I., M.K., and S.M. conceived the study. T.M. and H.I. performed all synthesis and characterisation experiments. Y.S. supported the synthesis. H.K., Y.H., and D.A. performed the SXAS. T.M. and K.K. performed all the electrochemical experiments. K.K. performed spectroelectrochemical measurements. T.K. performed XPS measurements. T.U. and S.K. performed SEM and EDX measurements. T.M., T.K., M.K., and S.M. analysed the data and co-wrote the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsuzaki, T., Kosugi, K., Iwami, H. et al. Iron-complex-based catalytic system for high-performance water oxidation in aqueous media. Nat Commun 16, 2145 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57169-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57169-y