Abstract

The practicality of memristor-based computation-in-memory (CIM) systems is limited by the specific hardware design and the manual parameters tuning process. Here, we introduce a software-hardware co-development approach to improve the flexibility and efficiency of the CIM system. The hardware component supports flexible dataflow, and facilitates various weight and input mappings. The software aspect enables automatic model placement and multiple efficient optimizations. The proposed optimization methods can enhance the robustness of model weights against hardware nonidealities during the training phase and automatically identify the optimal hardware parameters to suppress the impacts of analogue computing noise during the inference phase. Utilizing the full-stack system, we experimentally demonstrate six neural network models across four distinct tasks on the hardware automatically. With the help of optimization methods, we observe a 4.76% accuracy improvement for ResNet-32 during the training phase, and a 3.32% to 9.45% improvement across the six models during the on-chip inference phase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) technology, AI algorithm model parameters have exhibited explosive growth, creating very large hardware computing performance demands1,2. Conventional computing hardware based on the von Neumann architecture encounters a computing performance and energy efficiency ceiling due to the memory wall issue3. The computation-in-memory (CIM) architecture4,5,6,7,8, which stores the weight data locally and directly accomplishes the matrix-vector multiplication (MVM) with the memristor crossbar arrays, can enhance the computing performance and energy efficiency by orders. This attractive feature makes the memristor-based CIM architecture a revolutionary technology for future computing hardware systems9,10,11,12.

Recently, CIM functional demonstrations with memristor arrays have made remarkable progress, including pattern classification with a perceptron13 and convolution neural network14,15, voice recognition with long short-term memory (LSTM), image recovery with restricted Boltzmann machine16, and sparse coding17. These prototype demonstrations have experimentally verified the feasibility and advantage of CIM technology. However, to truly support practical and useful AI tasks, a CIM system should decouple with AI models, and can run various complex AI models with high accuracy. To date, there is a lack of a general methodology for such a practical system, leading to a deficiency in the practical application of CIM systems. The challenges towards this goal lie in two aspects: (1) The contradiction between the rigid memristor arrays and application flexibility requirement. Currently, AI models are increasingly complex and diverse, as shown in Fig. 1a. The size of each network layer varies and the connections between adjacent layers are complex. However, the size and arrangement of memristor arrays are fixed, which makes it difficult to adapt to the complex and rapidly changing AI models. (2) The accuracy loss caused by the nonideal effects of the hardware. Analogue computing with memristor arrays has many nonideal effects, including device variations, array voltage drops, analogue-digital conversion precision and so on. Existing studies have utilized specific hardware designs and manual parameter tuning methods to address these nonideal effects, but these optimizations are difficult to extend to a flexible CIM system due to its poor efficiency and transferability. These challenges lead to a very large gap (Fig. 1a) between the AI models and the CIM hardware, which severely blocks the transition of CIM technology from basic functional demonstrations to practical computing systems.

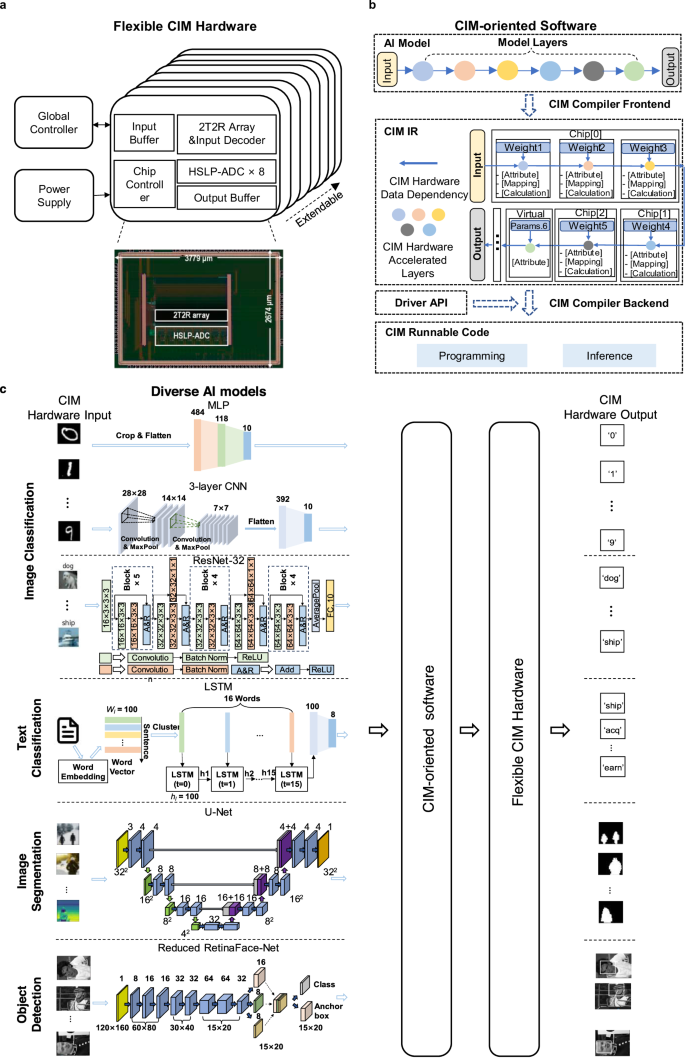

a Four AI tasks with different model topology structures. The best hardware parameters vary from model to model. Inappropriate parameters will lead to significant error which can severely reduce the on-chip inference accuracy. It is challenging to deploy various complex AI models on the CIM hardware and find the appropriate parameters, leading to a gap between the AI models and the CIM hardware. b The proposed CIM-oriented software framework with a loop compiler-hardware-optimizer for generating the hardware runnable codes and automatically finding the optimized tunable parameters. The compiler is used to generate runnable codes that can be directly executed on the hardware or simulator. The optimizer is used to optimize the weight and hardware parameters to be more robust against hardware nonidealities according to the built-in optimization method. c The flexible CIM hardware system with eight memristor chips, one FPGA module and one power supply PCB module on board.

To address these challenges, we propose a full-stack memristor-based CIM system employing a software-hardware co-development approach. Firstly, a CIM-oriented software framework (Fig. 1b) and a flexible hardware (Fig. 1c) are developed to tackle flexibility issues. The designed software, including a CIM compiler, an optimizer, and a chip simulator, can handle variable and complex AI models, effectively mapping them to memristor arrays with optimized spatial-temporal utilization rates. The flexible hardware, which incorporates multiple memristor chips, supports diverse AI model dataflows and offers flexible weight and input mapping. Secondly, to address the accuracy issues, we incorporate a variety of software-hardware co-optimization methods into the optimizer, applicable to both the training and deployment phases. During the offline training phase, we propose a post-deployment training method that autonomously refines model weights to enhance robustness against hardware nonidealities. During the model deployment phase, two optimization methods, namely single-stage automatic tuning and progressive two-stage search, are introduced to facilitate the automatic identification of optimal hardware parameters. These methods suppress the impacts of analogue computing noise, thereby enhancing the accuracy across various models. Finally, six representative AI models with typical topology structures applied to four AI tasks, including image classification, text classification, image segmentation, and object detection, are automatically demonstrated using the developed CIM hardware and software, achieving fully multiply-accumulate (MAC) operations on chips. Experimental results show that, for small-scale networks, including 2-layer multilayer perceptron18 (MLP), 3-layer convolution neural network19 (CNN), LSTM network20, U-Net21, and reduced RetinaFace-Net22, the proposed CIM software framework achieves notable improvements in on-chip inference accuracy by 5.40%, 9.12%, 4.99%, 9.45%, and 7.87% respectively. Furthermore, for medium-scale networks such as ResNet-3223, the CIM software framework enhances accuracy by 4.76% during the training phase and 3.32% during the on-chip inference phase. Even more significantly, for a large-scale network such as ResNet-5023, we also observe improvements of 38.76% and 3.39% in accuracy during the training and inference phase respectively, when using a chip simulator to evaluate our approach.

Results

Full-stack CIM system for diverse models

We develop a flexible and computationally efficient memristor-based CIM system, as shown in Fig. 1c. The hardware features flexible memristor chips and an extendable system design. The fabricated memristor chips contain functional circuit modules for flexibly accomplishing on-chip MAC with signed inputs and weights. The system adopts pluggable printed circuit boards (PCBs) to load memristor chips. In this way, the system can improve the memristor capacity by adding additional PCB modules without turning off the power (see Supplementary Note 1). In addition, the system contains one power supply module and one field-programmable gate array (FPGA, Xilinx, ZU3EG) with a hardcore CPU (ARM, Cortex™-A53) as the global controller, as shown in Fig. 2a. The FPGA with the hardcore CPU can flexibly control different data flows from one memristor chip to another. All AI models operations can be accomplished on the hardware system without using external assistance.

a Schematic of the system with eight memristor chips, one FPGA board as the global controller and one power supply module. Each memristor chip contains the functional modules such as an input buffer, a memristor array and its input decoder, an output buffer, an ADC, and an on-chip controller. Die microphotograph of the memristor chip with 144k cells. b The CIM IR with three types of parameters and two types of computing units for optimizing parameters and generating hardware runnable codes. c The schematic of six different AI models and the automatic deployment flow.

A microphotograph of the memristor-based CIM chip is shown in Fig. 2a. The chip contains a memristor array, signed input circuit (SIC), analogue-to-digital converter (ADC), on-chip buffer, on-chip controller, etc. Each memristor array contains 1152 × 128 1-transistor-1-memristor (1T1R) cells. Two 1T1R cells are grouped into one 2-transistor-2-memristor (2T2R) cell to represent one signed 4-bit weight value. The memristor cell adopts a TiN/TaOx/HfO2/TiN material stack. The cells exhibit excellent programming precision and retention time for both 3-bit single cell and 4-bit grouped cells (see Supplementary Note 2). The materials and fabrication process (see Methods) are compatible with the conventional complementary metal–oxide semiconductor (CMOS) processes. In addition, compared to a conventional binary input circuit, which only supports 0 and 1 as input, the designed SIC uses the same amount of voltage source to support signed input data (−1,0,1), increasing the hardware flexibility with almost no extra overhead. And the high-speed and low-power ADC, which uses 15 dynamic comparators to work simultaneously, improves the system’s throughput and reduces power consumption (see Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Note 4).

The complexity of AI models not only demands greater flexibility from hardware but also imposes higher requirements on software. Because the model deployment of analog computing systems introduces not only the labor burden challenges but also those of computing accuracy requirements. In this work, we introduce CIM-oriented software, as shown in Fig. 2b, which features a unified CIM-oriented intermediate representation (IR) (see Methods ‘CIM IR’ section). Base on the CIM IR, we further implement an end-to-end compiler, which support multiple AI model structures and hardware features (see Supplementary Note 5 and 6). Compared to prior CIM-oriented software framework studies24,25,26,27, which only consider the basic functional support that detects the CIM-friendly operations and deploys them on the CIM hardware, the proposed CIM IR further consider the hardware-related parameters representation. These parameters are tunable and exposed by the hardware, which aims at keeping the flexibility of the whole system and obtaining better performance. For example, in previous work16, to adapt to the diverse output dynamic range of different models, the chip operating conditions can be manually tuned according to the input data and model weight. Hence, to facilitate a more convenient and uniform representation of hardware-related and algorithm-related parameters, we categorize all parameters into three distinct types: algorithm parameters, mapping parameters and calculation parameters. Algorithm parameters refer to the models’ attributes, such as the operation’s type, and the stride, kernel size, and padding in convolution layer. Mapping parameters refer to the computation physical address in hardware and layer parameters in AI models. These parameters are determined by the compiler frontend with the mapping method (see Supplementary Note 5). Calculation parameters refer to hardware tunable parameters such as ADC integration time (IT), weight copy number (WCN), and input expansion mode (IEM), which are owned in our hardware. These different types of parameters are denoted as ‘Attribute,’ ‘Mapping,’ and ‘Calculation’ in Fig. 2b, providing a unified and comprehensive representation. There are two key advantages to model deployment using this unified CIM IR. Firstly, the unified representation bridges the gap of automatically converting high-level operations into low-level hardware implementations—a process that was previously handled manually in prior works12,16. Secondly, the unified representation enables automatic optimization with software, which substantially enhances the efficiency of parameter tuning. In addition, to easily deploy the AI models, we divide all AI model operations into two types: CIM-friendly operations and other operations. The CIM-friendly operations refer to convolution, MVM, transpose convolution, etc., which can be accelerated using memristor arrays. Other operations refer to pooling, linear rectification function, etc., which are computed on the FPGA in our system. In the IR of our software framework, we use the ‘Virtual’ to represent non-memristor computing units and place all of the CIM-unfriendly operations on it. For CIM-friendly operations, the compiler generates runnable codes that are executed on memristor arrays. For the other operations, the compiler generates codes, which are executed on the FPGA in our system. In the future, in a well-designed SoC chip, other operations can be computed using specific digital modules or an on-chip general processor module. The detailed deployment process can also be found in Supplementary Note 5.

Utilizing flexible hardware and general software, we have successfully implemented six different AI models with an automated deployment approach on a memristor-based computing system. The six AI models include a two-layer MLP, a three-layer CNN, and a ResNet-32 for image classification, a single-layer LSTM network for text classification, a U-Net for image segmentation task, and a reduced RetinaFace-Net for object detection (Fig. 2c). The chosen models are widely used in various typical AI applications, and contain the most common AI models operations. In addition, these models also include the basic model topology structures such as direct connections in MLP, skip connections in U-Net and ResNet-32, recurrent connections in the LSTM network, and gather connections in reduced RetinaFace-Net. The detailed neural network model parameters and performance are presented in the Supplementary Table S1. The processes of execution and mapping of above models can be found in Supplementary Note 7 and Supplementary Fig. S8. The model placement methods for CIM systems are also studied in previous work28, which can also be integrated in our software framework. These demonstrations illustrate that the developed CIM system, equipped with the proposed software framework, can manage a wide range of AI applications. This capability eliminates the need for manual efforts, thus enhancing the practicality of the CIM system.

Beyond its automatic deployment capability, our proposed software framework further incorporates three optimization methods to automatically mitigate the analog computing noise resulting from the analog system nonidealities16, thereby enhancing the on-chip accuracy. These three optimization methods are applicable to the two main stages of maintaining on-chip accuracy: the training stage and the deployment stage respectively.

Post-deployment training

For the training stage, we introduce the post-deployment training (PDT) method (Fig. 3a), which aims at automatically improving the robustness of model weights against the system nonidealities during training phase. The PDT method is proposed based on two observations. On the one hand, we find that the conventional offline training methods, such as hardware-aware training (HAT)29, relied on the precise computing models of the hardware inference process. And these precise models are not intuitive and easy-understanding for the algorithm designers who are not familiar with the hardware characteristics. Hence, current model training still relied on the experts who are familiar with both hardware and algorithm, which significantly limit the algorithm development.

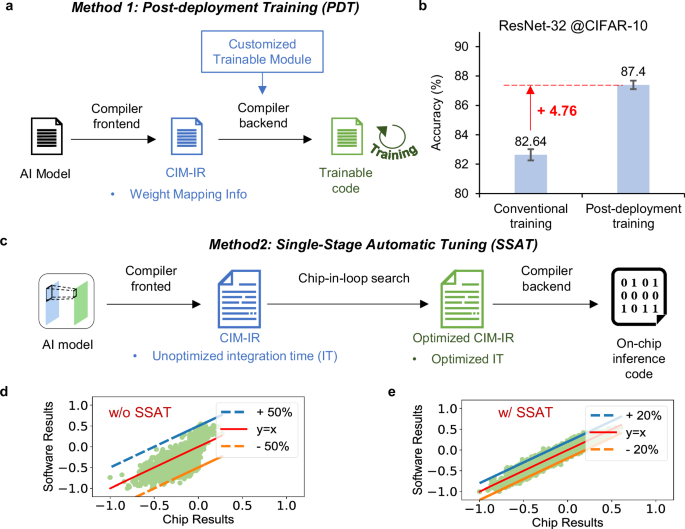

a The schematic of software work flow of post-deployment training. b Comparison of chip simulation accuracy between conventional training and post-deployment training. The error bar indicates the standard deviation derived from 10 repeated tests. c The software work flow of single-stage automatic tuning. d Comparison between pure software results and the fully on-chip MAC results without automatic parameter tuning. e Comparison between pure software results and the fully on-chip MAC results with automatic parameter tuning.

On the other hand, we find that the conventional training process overlooks the errors caused by two common operations in the CIM computing process. This oversight means that the conventional training process does not fully account for the hardware inference flow. First, the digital-to-analog convertor (DAC) of CIM hardware is often with low-precision, so the input data often needs to be split according to the bit width of the DAC (See Supplementary Fig. S12a). After splitting, the output result corresponding to each batch of DAC input data will lead to a quantization error for the final accumulated result. However, conventional HAT flow often quantizes only once after the input and weight multiplication and accumulation for the sake of model training convenience. This approach neglects the multiple quantization errors caused by bit-slicing. Second, when the algorithms are designed with large-size weights, the compiler will split these weights into pieces to adopt to the memristor array size (see Supplementary Fig. S12b). The output results from different pieces are also subject to ADC quantization error before accumulation. This further increases the discrepancies between the conventional training flow and the hardware computing flow. These computing processes with CIM characteristics have also been reported in other studies29,30.

Based on the above two observations, we propose the PDT method. This method not only recovers inference accuracy by training the model with an automatically generated hardware-consistent inference flow but also decouples algorithm design from hardware characteristics. Specifically, we adopt two critical designs to achieve this. Firstly, we customize the bit-level gradient backpropagation process in the training flow to keep the computation process consistent with the hardware’s bit-slice computation process. Secondly, since we cannot restrict the weight size of the algorithm to always meet the requirements of the array size, we use a ‘deploy-first-train-later’ approach for model training. That is, we use our software tools to deploy the model on the hardware virtually, which can get the CIM-IR with weight mapping information. And then, with support of the proposed software framework, we can generate new trainable neural network codes, such as Pytorch31 codes, according to CIM-IR and customized trainable module. Thereby, we can train the newly generated network codes to perceive the error problem caused by bit slicing and weight splitting. Notably, the entire training process is facilitated by our automated software framework, which markedly enhances training efficiency. And the customized trainable module can be provided by the chip vendor, which is invisible to the algorithm designer. This approach allows algorithm designers to remain unaware of the hardware characteristics, thereby alleviating the training burden on algorithm designers. The detailed implementation of PDT can be found in Methods section ‘Post-deployment training’.

To verify the effectiveness of the above methods, we implement both the conventional training and the post-deployment training methods for ResNet-32 model in Pytorch framework. To keep the training process consistent, both training processes use the same training parameters, i.e., learning rate, batch size, number of training epochs, input and weight quantization precision, weight noise amplitude. The detailed training process is shown in Supplementary Fig. S13a. The results reveal a very similar trend in loss reduction between the conventional training method and the PDT method, which indicates that our proposed method does not introduce additional training complexity. After training, two sets of different network weights are obtained. We use these two sets of weights to perform inference on a chip simulator, which contains all non-idealities of the memristor chip, as shown in Fig. 3b. The experimental results show that the PDT method can improve the inference accuracy by 4.76% compared to the conventional training method, while preserving friendliness to algorithm designer. Furthermore, we also evaluate this method using a large-scale network such as ResNet-50 for CIFAR-10032 classification. The model structure is shown in Supplementary Fig. S22, which contains 23.65 M weight parameters. The training process and test results are shown in Supplementary Fig. 13b, which show that the PDT method can get a 38.76% accuracy improvement. The results suggest that as network depth increases, the accuracy degradation becomes more pronounced. The primary reason for this is that with a greater number of layers, errors resulting from quantization and other non-idealities can accumulate substantially, resulting in an unacceptable on-chip accuracy. This result further confirms that the aforementioned mismatched errors have a significant impact on the model accuracy, especially for the deep models, and it also validates the effectiveness and necessity of the PDT method.

Single-stage automatic tuning

For the deployment stage, it is essential to identify the best hardware tunable parameters to reduce the analog computing error for well-trained models. The accuracy loss due to analog computing noise varies across different models. Larger networks with more on-chip layers tend to be more susceptible to analog computing noise16. Additionally, the effectiveness of using varying amounts of hardware parameters to reduce the analog computing error also varies. Generally, increasing the number of tunable hardware parameters is helpful in reducing the analog computing error, albeit at a higher optimization cost. Accordingly, different networks may necessitate distinct optimization strategies. To meet the diverse optimization demands during deployment stage, we have integrated a variety of optimization strategies into our software framework. Specifically, we introduce two strategies: Single-Stage Automatic Tuning (SSAT) and Progressive Two-Stage Search (PTSS). SSAT is specifically designed for automatically optimizing a single tunable parameter when deploying small-scale networks, such as MLP, 3-layer CNN, LSTM, reduced Retinaface-Net, and U-Net in this work. PTSS is adapted for automatically optimizing multiple tunable parameters when deploying medium-scale and large-scale networks, like ResNet-32 and ResNet-50 in this work. Through a combination of on-chip experiments and simulation experiments, we validate the effectiveness of two distinct optimization strategies across networks of varying scales.

For a single parameter identifying, previous work16 determined the reasonableness of hardware parameters by comparing the hardware output results with software results of a subset of training dataset. The software results can be obtained by using the CPU to inference the model with floating-point format. Inspired by this, we can automatically complete this process through the proposed software framework as shown in Fig. 3c. We introduce the SSAT method for the automatically identifying the hardware parameter, which use the proposed CIM IR to represent the tunable hardware parameters and use the chip-in-loop (CIL) search method to automatically determine the optimal hardware parameters. For our hardware, the IT of ADC is the most critical hardware parameter, which can directly determine the hardware output. The inappropriate IT of ADC can result in considerable errors in the output digital signal, which leads to a significant accuracy loss on model accuracy. We conducted experiments on the convolutional layers of a 3-layer CNN and the RetinaFace-Net, adjusting the IT and observing the impact of the output results on final accuracy, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S9. The results indicate that for both networks, inappropriate ITs indeed result in over 50% loss in model accuracy. Hence, the SSAT method mainly focus on the carefully adjusting the IT to minimize the impact of analog computing noise on model accuracy. The key idea of SSAT is to use a compiler-hardware-optimizer to iteratively find the best hardware tunable parameters for each AI model. By tuning the IT value of each on-chip layer, we can get different hardware outputs of the chosen training dataset. And then we can get the mean square error (MSE) between the hardware results and the software results. In this study, we employ a greedy algorithm to search for the optimal IT, iteratively traversing the IT values within the specified range until the MSE ceases to decrease. The detailed search process can be seen in Methods section ‘Chip-in-loop search in SSAT’. We utilize the MVM results, which represent distinct hardware outcomes with consistent input and weights but different ITs, to illustrate the efficacy of the SSAT method, as depicted in Fig. 3d and e. These results demonstrate that the SSAT method can decrease the MSE by over 30%. Through minimizing the MSE of each layer, we can get the optimal IT value of all on-chip layers automatically, thereby improving the on-chip accuracy of each model.

Progressive two-stage search

For multiple parameters identifying, we can transform the parameters identifying problem into an optimization problem focused on minimizing the model final output error between the software and the hardware. Specifically, without considering any non-ideal factors, we can obtain the software output, Outideal. By adjusting multiple hardware parameters, we can obtain the inference result, Outhardware, from the hardware. By continuously tuning these parameters to make Outhardware as close as possible to Outideal, the overall accuracy of the hardware will approach that of the software, thereby improving the on-chip inference accuracy. Therefore, we can convert the entire parameter search process into an optimization problem as expressed in Eq. (1), which aims to minimize the mean squared error (MSE) between Outideal and Outhardware. Considering the multiple parameters of our hardware, we incorporate two additional parameters, which are WCN, and IEM. Both of these parameters are instrumental in reducing analog computing noise. The effects of these parameters on the hardware outputs are detailed in Supplementary Note 7 and illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S9 respectively. Hence, Outhardware is determined by the model parameters (Model), IT, WCN, and IEM, as shown in Eq. (2). Additionally, in order to implement this model within a single system, we want all the copied layer weights to fit within a single system (8 chips). Hence, we need to add the capacity constraint as shown in Eq. (3), where N is the number of network layers deployed on the chip.

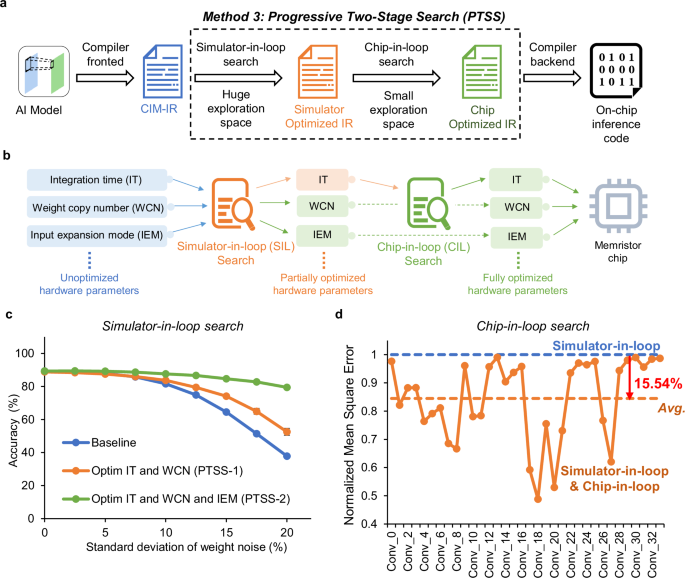

To solve the optimization problem, we introduce the progressive two-stage search (PTSS) method, which incorporates both simulator-in-loop (SIL) and chip-in-loop (CIL) search, as shown in Fig. 4a. Since the feasible solution space for the overall hardware parameters expands exponentially with the number of parameter types and the depth of the network, our objective in the SIL search stage is to identify the optimal hardware parameters within a vast search space. Specifically, we primarily use the genetic algorithm33 (GA) as the search algorithm and employ a chip simulator to approximate the hardware output. The GA is a very common and efficient method to solve multi-parameter optimization problems in a huge search space. The two critical processes of GA are representing ‘individual’ and getting ‘fitness’. In this work, we gather all hardware parameters corresponding to the on-chip layers together to represent the ‘individual’ in GA. And we use the MSE between the simulator results with tuned hardware parameters and the software results as the ‘fitness’ in GA. The optimization process of the GA is to minimize the MSE through tuning the hardware parameters of each on-chip layer. The detailed implementation of the SIL can be found in Methods section ‘Simulator-in-loop search in PTSS’. From this stage search, we can fix most of the optimized parameters among all hardware parameters, such as WCN and IEM in this work, as shown in Fig. 4b.

a The schematic of software work flow of progress two-stage search, involving simulator-in-loop search and chip-in-loop search. b The schematic diagram of the multiple parameters search process in this study. During the Simulator-in-loop (SIL) search, a majority of parameters can be fixed from a vast parameter space, including WCN and IEM in this study. However, due to discrepancies between the chip simulator and the actual hardware, some parameters must be refined during the Chip-in-loop (CIL) search, which is aimed at further reducing computing noise on the actual chip, such as IT in this work. c The trend of test set accuracy with the change in standard deviation of weight noise under three different optimization configurations: baseline, PTSS-1, and PTSS-2. d Comparison of the on-chip inference normalized mean square error for all layers in ResNet-32 using parameters searched with SIL search and parameters searched with both SIL search and CIL search.

To evaluate the effectiveness of SIL search, we conduct experiments on the ResNet-32 network using the SIL method, selecting 256 training samples as the model’s input to obtain the software output (see Supplementary Note 13). We use parameters optimized solely for IT as the baseline and observe improvements in model accuracy when multiple parameters are optimized. Our experiments focus on two scenarios: optimizing the IT and the WCN (PTSS-1), and simultaneously optimizing the IT, the WCN, and the IEM (PTSS-2). First, we observed the trend in MSE error changes during the GA’s iteration process in these two scenarios, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S14a. For PTSS-1, the GA is set with a population size of 100 and a maximum of 300 iterations. Since PTSS-2 involves more parameters, the population size is increased to 150, with a maximum of 500 iterations. As expected, the MSE decreases as the GA iterates. After optimization, we select the tuned hardware parameters corresponding to the lowest MSE during the optimization as the parameters for inference. We then perform inference using the chip simulator with CIFAR-10 test dataset. As depicted in Fig. 4c, the results demonstrate that an increased number of tunable parameters confer greater robustness against noise, consequently enhancing the accuracy of inference. Furthermore, we evaluate the SIL search using the large-scale network, ResNet-50. The optimization details are provided in the Methods section ‘Simulator-in-loop search in PTSS’. The experimental results are presented in Supplementary Fig. S14b, which also illustrate the effectiveness of SIL search on optimizing multiple parameters. Especially when the standard deviation of weight noise reaches 12% of the weight range, which is comparable to real chips noise, the inference accuracy can be improved by up to 3.39% relative to the baseline.

Through the SIL search, we have obtained hardware parameters that are more robustness against analog computing noise. Subsequently, we deploy the well-trained weights in the hardware and utilize the parameters derived from the SIL search to inference on chip. During on-chip measurement, we encounter two abnormal cases that could lead to accuracy loss, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. S15. In the first case, we find that the optimized parameters yield varying effects across different layers. As shown in the Supplementary Fig. S15a, for certain layers, optimized parameters do not necessarily reduce the MSE. We attribute this primarily to the simulator’s inability to fully simulate all the intricate details of system noise. To alleviate the burden of modeling, we add the same noise to the weights of each layer in the simulator. However, in reality, the write noise of weights and the read noise during on-chip calculation are not necessarily consistent across all layers due to the varied weight numbers, weight positions, and the programming accuracy. These factors result in some discrepancies between the parameters obtained from the simulator and the optimal parameters for the actual chip. In the second case, we discover that even with the same optimized parameters, the measured results on different systems can vary. As depicted in the example of Supplementary Fig. S15b, the same optimized parameters that reduced MSE compared to the ‘Baseline’ for System 1 actually increased the MSE for System 2. We think that this discrepancy arises from two main factors. First, there are differences between analog computing systems. Despite employing the same PCB design and power supply, variations in manufacturing can lead to differences in performance across systems. Second, there are variations between chips. Apart from the inherent fluctuations in analog computing, manufacturing deviations result in differences between chips. These variations, combined with the non-idealities of the analog computation array, collectively contribute to the distinct performances of the systems. However, these differences are not reflected in the simulator, and accurately modeling these non-idealities is highly complex and costly.

Hence, to further reduce the effect of differences between simulator and real systems, we introduce the second stage optimization method - CIL search, as shown in Fig. 4a. Due to the optimization conducted in the first stage of PTSS, we have already obtained reliable parameters that exhibit a relatively strong resistance to system noise within an extensive search space. Consequently, it is unnecessary to perform a comprehensive search for all parameters again. Building on the experience of CIL search in SSAT for single parameter, we have found that layer-by-layer adjustment on the target chips enhances adaptability. This adjustment involves tuning the parameters after weight deployment, aligning them more closely with the characteristics of the target system. This approach can mitigate the impact caused by the discrepancies between systems and chips. Therefore, in this stage, we also employ the CIL search method to further refine the parameters of each layer on chips after weight deployment. During this stage, we still primarily focus on adjusting the IT of each on-chip layers as shown in Fig. 4b. There are two reasons to choose IT as the on-chip search parameter. First, other parameters influence the choice of IT, and adjusting them would expand the search space, thereby increasing the on-chip search cost. Secondly, compared to other hardware parameters, IT has a more pronounced direct impact on chip results, making it a more efficient choice for enhancing on-chip accuracy. The detailed process of CIL search in PTSS can be found in Methods section ‘Chip-in-loop search in PTSS’.

Utilizing the CIL search method, we conduct experiments on chip. In these experiments, we set the search range to ±500 ns around the IT optimized in the first stage. For above-mentioned two abnormal cases, we obtain the on-chip results after CIL search, which are depicted in Supplementary Fig. S16. The experimental findings indicate that the on-chip search in the second stage achieves two significant improvements. Firstly, it further reduces the computing error of the parameters obtained from the simulator in actual on-chip measurements. Secondly, it overcomes the issue of parameter mismatch caused by discrepancies among different systems. This approach can maintain the analog computing noise of various systems at a relatively lower level. In addition to this, we also evaluate the impact of the CIL method on reducing the MSE for all on-chip layers of ResNet-32. The results are presented in Fig. 4d, where the vertical axis represents the normalized MSE, and the horizontal axis indicates the names of the on-chip layers of ResNet-32. The experimental results show that the CIL method can further reduce the MSE by 15.54% averagely compared to the SIL method. This enhancement in robustness against system noise and discrepancies underscores the effectiveness and necessity of the CIL optimization in PTSS.

On-chip inference demonstrations

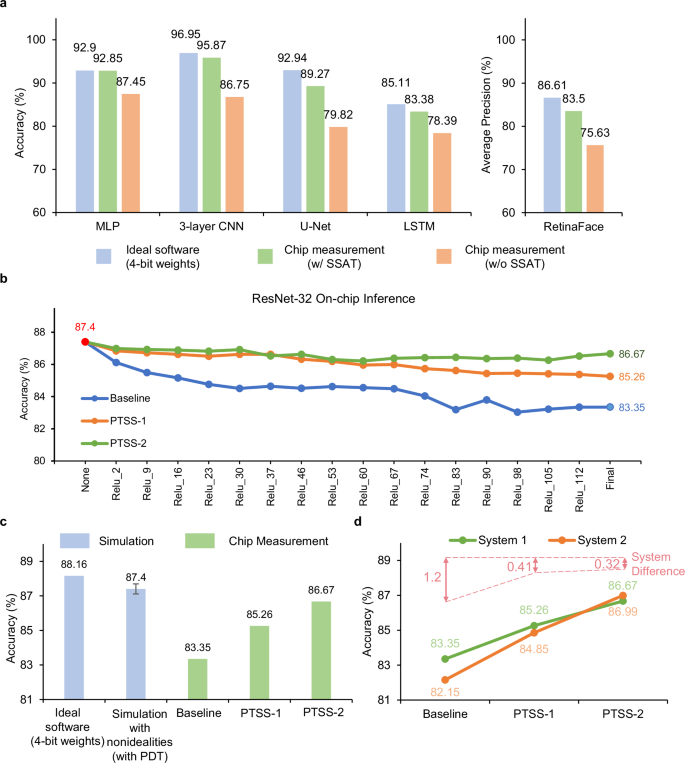

Finally, we utilize the flexible CIM hardware and full-stack software framework to automatically implement on-chip inference for all models in Fig. 2c. The training process and used datasets of all demonstrated models can be found in Supplementary Note 12. Applying the SSAT optimization method, we optimize five small-scale models, including MLP, 3-layer CNN, LSTM, reduced Retinaface-Net, and U-Net. The automatic optimized IT of ADC for each model is detailed in Supplementary Table S2. We conduct a comparison among three experimental sets: software results with 4-bit weights (Ideal software (4-bit weights)), chip measurement with SSAT, and chip measurement without SSAT. The configuration in the case of chip measurement without SSAT set the IT of last on-chip layer to 100 ns for each model, aligning with the default value of the system in this study. The experimental outcomes in Fig. 5a reveal that, through the utilization of the automatically tunning method, the classification accuracy of the 3-layer CNN model reached 95.87%, which is only 1.08% lower than the 4-bit software results. The average accuracy across all demonstrated small-scale models is 1.93% lower than the 4-bit software results. Additionally, the optimized on-chip inference accuracy demonstrates improvements of 5.40%, 9.12%, 4.99%, 9.45%, and 7.87% for the MLP, CNN, LSTM, U-Net, and reduced RetinaFace-Net, respectively, in comparison to the chip measurement without SSAT.

Through the SSAT optimization method, we have been able to significantly improve the on-chip accuracy in multiple small-scale AI models and effectively improve the efficiency of model deployment. For larger neural network models with more layers on chip, the analog computing noise accumulates layer by layer. In such cases, the simple and efficient method of tuning the IT becomes insufficient, leading to a significant reduction in final accuracy. As shown in Fig. 5b, we deploy the ResNet-32 network with 33 convolutional layers and 1 fully connected layer on the memristor chips to recognize the CIFAR-1032 dataset, which comprises 10,000 test images. The model structure and mapping locations on chips are shown in Supplementary Fig. S11. Although we conduct PDT method during the model training phase and optimize the IT during deployment phase using the SSAT method, the on-chip inference accuracy is still 4.05% lower than the software simulation accuracy with 4-bit weight (decreasing from 87.4% to 83.35%), which is unacceptable.

To maintain the on-chip inference accuracy for deep models, we employ the proposed PTSS method to conduct on-chip measurement experiments with the ResNet-32 model within the developed memristor-based system. We perform on-chip inference experiments for three scenarios: optimization of IT using SSAT (Baseline), optimization of IT and WCN using PTSS (PTSS-1), and simultaneous optimization of IT, WCN, and IEM using PTSS (PTSS-2). The experimental results are illustrated in Fig. 5b. The results demonstrate that, with the increasing number of optimization parameters, the on-chip accuracy at each node has been significantly improved, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed optimization strategies. In the case of parameter optimization involving only the increase in WCN, the on-chip measurement accuracy is improved by 1.91%. When both WCN and IEM are all involved, the accuracy is further enhanced by 1.41%, as shown in Fig. 5c.

a Comparison of the accuracy between software results with 4-bit weights, on-chip results with SSAT, and the on-chip results without SSAT of various AI models. b CIFAR−10 classification accuracy at different model layers. From left to right, each data point represents a block of model layers inferenced on chip. The layers on the x-axis are the ReLU layers in the model, which are renamed by our software tool. The accuracy at a layer is evaluated by using the on-chip results from that layer as inputs to the remaining layers that are simulated in software with non-idealities. Three curves compare the test-set inference accuracy between the optimizing integration time only (Baseline), optimizing the integration time and weight copy number (PTSS-1), and optimizing the integration time, weight copy number, and input expansion mode (PTSS-2). c Comparison of software results with 4-bit weights, simulated results with 4-bit weights including all non-idealities, and on-chip results with optimizations under three configurations: Baseline, PTSS-1, and PTSS-2. The error bar indicates the standard deviation derived from 10 repeated tests. d Comparison of on-chip inference results under different systems with optimizations of Baseline, PTSS-1, and PTSS-2.

Furthermore, we also note a significant reduction in the discrepancies of on-chip accuracy across different systems when employing the PTSS method. As depicted in Fig. 5d, using the same CIFAR-10 test dataset, we conduct experiments on two separate systems. The experimental results suggest that the PTSS method effectively improves the on-chip accuracy and mitigates the impact of system discrepancies on accuracy. Consequently, both systems exhibit considerable enhancements in accuracy as the number of optimization parameters increases, achieving up to 3.32% and 4.84% improvements on model accuracy for system 1 and system 2, respectively. Furthermore, despite system discrepancies, the PTSS method ensures minimal variation in on-chip inference accuracy across different systems, significantly reducing the accuracy discrepancy by up to 0.88% (from 1.2% to 0.32%). The experimental results illustrate that the PTSS method effectively reduces the effects of fluctuating model accuracy resulting from system discrepancies, thereby enhancing the consistency of AI models inferencing across different analog computing systems.

Discussion

In this study, we have demonstrated the feasibility of our memristor-based CIM system through the automatic execution of six typical AI models. This system encompasses both an end-to-end software framework and hardware design, effectively catering to the inference requirements of diverse AI tasks. Remarkably, the full-stack system exhibits state-of-the-art flexibility in dealing with diverse AI models and maintaining the on-chip inference accuracy, when compared to the latest reported works in the field. Our software framework enables the seamless execution of the entire processing pipeline, encompassing model parsing, model deployment, on-chip inferencing, and automatic optimization of CIM hardware performance, all without the need for manual intervention. What’s more, we have showcased six typical AI models that encompass the most prevalent deep learning operations and model topology structures. The experimental results underscore the strong generality of our CIM-oriented software framework for a wide range of existing AI tasks, delivering significant enhancements in accuracy. Furthermore, the on-chip experiments demonstrate that our proposed software-hardware co-optimization method can effectively alleviate the impact of system discrepancies on model accuracy. Compared to the prior studies, our work demonstrates a significant advancement, particularly in the realms of automatic transformation during algorithm training, the optimization of parameters within the software automation framework, and the enhancement of model diversity in hardware validation (see Supplementary Tables S8 and S9). Importantly, this framework does not impose strict constraints on device type and can be deployed not only on memristor-based systems but also on other CIM systems. This full-stack system introduces an innovative approach to promote the wider adoption of CIM systems, facilitating research and demonstrations in this field for a broader audience.

Methods

Experimental platform

We built a prototype CIM system with eight fabricated memristor chips, a Xilinx Zynq UltraScale+ MPSoC ZU3EG field-programmable gate array (FPGA) with 4 ARM CPUs (Cortex™-A53), and a power supply module. The power supply PCB includes power modules, such as current-source digital-to-analogue converters, and linear regulators, which provide the supply voltage and various operating voltages for the memristor chips. The FPGA board is mainly used to control the whole system, including data exchange and controller signal transmission. Each memristor chip contains 144k memristor cells that can represent 72k signed 4-bit weights. Two chips are loaded on one PCB. The connection between PCB modules adopts the High-speed ground plane connector - QTH-060-07-L-D-A, which provides up to 480 pins to transmit signals between the two nearest PCB modules. The I/O protocol between the memristor chip and FPGA is customed. And the data bandwidth between the chip and FPGA is 80 megabits per second. The on-chip input and output buffers are 1024 bits and 32 bits respectively. The detailed appearance of the whole system and its measured hardware performance can be found in the Supplementary Fig. S18 and Supplementary Note 8 respectively.

The memristor device adopts a TiN/TaOx/HfO2/TiN stack structure, which is sandwiched between the fourth metal and the top metal in the chip. The CMOS circuits are fabricated with standard 130 nm technology, and each memristor device is fabricated after completing the CMOS fabrication. Each array has 1152 rows and 128 columns. All cells in the same row share one BL for applying the voltage as input and all cells in the same column share one SL for collecting current as MAC output. Each array has 8 analogue-to-digital convertors, and the detailed information about the ADC can be found in Supplementary Note 3 and 4.

The ARM CPU on the FPGA runs a Linux operating system that provides an environment for compiling programs and controlling the data flow for inferencing. It can also complete additional necessary functions that cannot be calculated using the memristor chips, such as the activation function, during model inferencing. The CIM compiler compiles the model description files (using Open Neural Network Exchange (ONNX) (https://onnx.ai/) in this article) into the executable files that can directly call the analogue control and computing interfaces (hardware driver program). The analogue control and computing interfaces can directly change some specific register values on the FPGA through the PYNQ framework (https://github.com/Xilinx/PYNQ). These specific register values correspond to the control signals of the memristor chips. The compiled files in the operating system can be modified and checked according to the optimization methods. This allows users to program codes on the system for various model inferencing without the help of other external computing systems. For all the demonstrated models, the energy consumptions of data communications between chips are also evaluated, which can be found in Supplementary Note 9.

CIM IR

Intermediate Representation (IR) serves as a crucial component that enables algorithms to be deployed onto hardware platforms efficiently for AI tasks. Depending on its operation stage in the compilation process, IR can be categorized into two types: high-level IR and low-level IR. High-level IR provides a computation abstraction of algorithmic tasks, focusing on the computational flow rather than specific hardware implementations. In contrast, low-level IR offers an abstraction of the implementation details of hardware computing, emphasizing hardware-specific aspects. Currently, some existing high-level IRs34,35,36 are primarily designed for traditional digital computing platforms and lack considerations for CIM characteristics. As a result, the transition from high-level IR to low-level IR often lacks the essential information needed for hardware computing, such as weight addresses and tunable parameters specific to CIM hardware. This inefficiency can hinder the smooth completion of the compilation process. What’s more, in the previous work16, the inference process for different network tasks at CIM system primarily involves tightly coupling network algorithms with low-level hardware computing function codes. Virtually every network’s inference process requires manually reconstructing the network structure by calling underlying hardware computing functions. This labor-intensive approach limits the efficiency and flexibility of algorithms demonstrating on a CIM system.

Hence, our work introduces a CIM-oriented high-level IR design, namely CIM-IR, to bridge this gap by incorporating CIM-specific information into existing high-level IRs that describe computational graphs. This integration aims to make the entire algorithm compilation process more seamless and natural. The primary implementation approach involves introducing a YAML-based37 data format to store algorithm, mapping, and calculation parameters. To ensure compatibility with various hardware designs, we employ mixins programming technique38 in python to maintain the versatility of the software tool. This approach enables us to define various calculation and mapping information based on different hardware characteristics and consolidate all these definitions into a unified IR. By employing mixins techniques, we empower the compilation frontend tool to adapt and generate CIM-oriented IR with specific CIM features. Detailed definitions of the IR for the hardware system proposed in this work can be found in Supplementary Note 5.

This IR design offers two significant advantages for CIM system deployment. Firstly, by unifying IR definitions, the algorithm compilation and deployment process are streamlined. This facilitation allows for the reuse of software transformation modules across different algorithms and CIM systems, thereby reducing development costs. Secondly, the inclusion of CIM-related characteristics in the IR enables the software framework to be aware of CIM system features. This awareness simplifies the design of optimization methods tailored to CIM systems during the training and deployment process. Utilizing this IR, CIM-oriented deployment becomes significantly more straightforward and convenient.

Chip-in-loop search in SSAT

The optimization method, used in the optimizer module, is a crucial part of the software framework for global optimizations. It is mainly used to improve the system accuracy. In this article, we propose an intuitive but effective optimization method as an example that aims to demonstrate the capability of software framework. We use this method to optimize the hardware parameters layer by layer for each model.

In this study, we implement an automated procedure to adjust the IT of the ADC, with the goal of minimizing the MSE between the software-generated results and the on-chip outcomes. This adjustment is achieved through the compiler, which can invoke the driver API to apply the specified value to the hardware. For the process of the proposed optimization method, there are three main steps, which are shown in Algorithm 1.

First, we initialize a count variable named count to 0. When the variable value is larger than threshold value, the optimization process is terminated or jumps to next CIM-friendly layer. Then, the model description and hardware initial configurations are input into the CIM compiler to generate runnable codes for performing fully on-chip MAC.

Second, we add the current hardware configuration into a configuration set. The configuration set records all the configurations during the optimization. Then, we use the prepared subset of the training dataset to calculate the current CIM-friendly layer and obtain the on-chip results with the initial hardware parameters. The on-chip results are compared with the prepared software results, and we obtain the MSE. The MSE is recorded with the corresponding configuration. If the current MSE is larger than the latest one or the absolute difference between the current MSE and the latest one is smaller than alpha multiplied by the latest MSE value, the variable count is increased by 1; otherwise, its count is replaced by 0.

Third, if the count is larger than the threshold value, the algorithm stops to optimize current layer and continues to optimize the next CIM-friendly layer. If not, the algorithm continues and adjusts the hardware parameters gradually for the current layer, for example, adding 100 ns to the ADC IT value in this work. The algorithm is terminated when all CIM-friendly layers are optimized. The hardware parameters of each CIM-friendly layer corresponding to the recorded lowest MSE are output for inferencing all test data.

During iterations, we primarily determined the adjustment step in the algorithm based on hardware constraints. The on-chip clock from the FPGA for the ADC is 10 MHz, thus setting the minimum adjustable period at 100 ns. Hence, we fine-tune the IT from the minimum of 100 ns to the maximum of 6300 ns, with increments of 100 ns. And the maximum value (6300 ns) is determined by the verification time of programming a single device. Since both the read-out of device programming and the array computations utilize the same set of ADCs, and the current during array computations is significantly higher than during the read-out of programming a single device, it is necessary to use an IT for confirming the state of a single device that is greater than the IT used during computations. In this study, 6300 ns represent the required IT for read-out of programming a single device. Hence, we set 6300 ns as the maximum value during adjustment. During each iteration, we increased the IT by 100 ns and terminated the iteration when reaching the maximum value or meeting the other stop requirements. What’s more, we also study the impacts of two hyperparameters (alpha and threshold) on optimized performances, the detailed information can be found in Supplementary Note 10.

Furthermore, within our software framework, a well-designed simulator can serve as a substitute for the actual chip, providing the optimizer with faster and more universally applicable feedback for small-scale networks. This simulator can also be used to optimize the various tunable hardware parameters. Ideally, the compilation process could occur on any host machine, and the resulting compiled code could be executed on the target hardware, demanding a high degree of compiler portability. Incorporating a simulator for optimization can enhance this portability. We conduct two experiments to validate the effectiveness of the simulator-based method, and the results suggest that this approach yields commendable accuracy, with only a slight reduction compared to chip-based optimization. More detailed information regarding simulator-based methodology can be found in Supplementary Note 11.

Algorithm 1 | Chip-in-loop search in SSAT

1: Input: Model Description; Hardware initial configurations; Software Results on a subset of training dataset; Threshold (>=0); alpha.

2: Initialize the parameter: count = 0

3: Run the CIM compiler and obtain the runnable codes

4: for (layer in all CIM-friendly layers) do

5: while count <Threshold do

6: Add current config into configuration set configs

7: Perform fully MAC on hardware with the given training dataset. And obtain the chip or simulator results

8: Calculate the mean square error: Ecur of chip results and software results and record it

9: if (current Ecur >= last Ecur) or (|last Ecur – current Ecur|<= last Ecur × alpha) then

10: count = count + 1

11: else

12: count = 0

13: end if

14: Extend the ADC integration time by 100 nanoseconds., record current configuration: Config and run the CIM compiler.

15: end while

16: end for

17: Output: The lowest Ecur hardware configuration of each layer in all Configs: Configbest.

Post deployment training

Compared to conventional training, post-deployment training can capture more hardware inference characteristics, thereby better maintaining on-chip inference accuracy. First, we map the input neural network on chip based on the structure of the neural network and the size of the memristor array. We obtain the CIM-IR through the compiler frontend tool. The IR mainly includes information about weight splitting. Then, using the information from the IR and our customized trainable modules, we can generate new training Pytorch codes with the compiler backend tool. This weight split information enables the newly generated code to be aware of the quantization errors resulting from computations on different arrays. The trainable modules are designed to align with the actual hardware computing process. Utilizing the Pytorch framework, we have extended the original convolution and fully connected classes, customizing the forward propagation process to enable bit-level inference perception. Furthermore, we have implemented the backward propagation process for the customized components, allowing for model training leveraging Pytorch’s automatic differentiation functionality. The detailed pseudocodes are shown in Supplementary Fig. S24. Additionally, we offer a comprehensive software tools that converts Pytorch source codes into hardware-aware trainable codes, allowing algorithm designers to remain unaware about these hardware-related details.

We train the ResNet-32 and ResNet-50 using the standard CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 dataset respectively, and the training parameters can be seen in Supplementary Table S3. To fairly compare with the conventional training method, we train the two models with same configurations, including the training epochs, learning rate, batch size, and gradient optimizer. To efficiently train the network with low-precision and noisy weight, we adopt three stages, which are 90 epochs floating-point training, 60 epochs quantization training, and 60 epochs quantization with noise training, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S13a. It can be observed that the PDT method can reduce the loss as the same with the conventional method. In addition, the PDT method can improve inference accuracy by 4.76% and 38.76% compared to the conventional training method for ResNet-32 and ResNet-50 respectively, demonstrating its effectiveness.

Simulator-in-loop search in PTSS

The schematic of implementation of SIL search with GA in Supplementary Fig. S23. Initially, we introduce the GA to solve the aforementioned optimization problem. GA has a significant advantage in solving black-box optimization problems with large parameter search spaces and are widely used in optimizers of various AI compilers39,40. In this work, we adopt an open-sourced library (https://scikit-opt.github.io/) when implementing GA. When using this method to solve the problem, there are mainly two considerations: the representation of individuals in the GA and the way to obtain the fitness value. For the ‘individual’ representations in GA, the tunable parameters in this work can all be expressed as integers, hence we use the integer representations in GA. Specifically, the IT can be represented as an integer, such as m, which means m × 100 ns. The IEM can be represented as binary value (0,1). ‘0’ represents fully unroll mode and ‘1’ represents bit-slice unroll mode. Hence, we can combine the integers of the variable parameters (IT, WCN, IEM) of each layer according to the sequence of network layers. The resulting integer set can then serve as a single individual in the GA, as shown in Eq. (4).

The numbers represent the positional relationship of the network layers. By the position information of the parameters in the list, we can determine which layer and which parameter of the network the parameter corresponds to. For obtaining the fitness value, we mainly utilize the software framework proposed in this paper. It allows the new parameter combinations updated by the algorithm in each iteration to be recompiled into new CIM-IR. The new CIM-IR is then passed through the compiler backend to generate code that can run in a simulation environment. Using this generated code and a portion of the training dataset, we can obtain the output result under the current parameter combination. Finally, we use the MSE between this output result and the ideal result as the final fitness value, guiding the GA’s search by minimizing the MSE error. In this process, we use a simulator as the inference environment for the algorithm instead of real hardware, mainly considering the inference speed of large volumes of data. Simulators are more flexible than real systems and can leverage the faster computation acceleration of GPUs for large-scale inference, thus speeding up the search process and reducing the time for parameter optimization.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the method on large AI model, we conducted experiments using the above-mentioned ResNet-50 model in a chip simulator. The experiment involved using 256 training images as the model’s input and to obtain the ideal output. We used the parameters obtained by optimizing only the IT as the baseline and observed the improvement in model performance when multiple parameters were optimized. We conducted simulation experiments focusing on three scenarios: optimizing only the IT (Baseline), optimizing the IT and weight replication number (PTSS-1), and optimizing the IT, weight replication number, and bit expansion method simultaneously (PTSS-2). Firstly, we observed the trend of MSE error over the iteration process of the GA under these three scenarios, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S14b left. The GA parameters for PTSS-1 were set to a population size of 150 and a maximum number of iterations of 300. For PTSS-2, which involves more parameters, the population size was set to 150 and the maximum number of iterations to 550. As expected, the optimization results showed that the MSE error of the output indeed decreased with each iteration of the algorithm. After optimization, we used the layer parameters corresponding to the lowest MSE during the optimization process as the hardware parameters for inference and performed inference on 10,000 test images using the chip simulator, with the results presented in Supplementary Fig. S14b right. As the number of optimized parameters increases, the model’s capabilities to surpass noise also gradually improves, indicating the effectiveness of the GA-based simulator-in-the-loop optimization method. This optimization can significantly enhance the inference accuracy.

Chip-in-loop search in PTSS

The chip-in-the-loop search in progress two-stage search is shown in Algorithm 2. Through the simulator-in-the-loop search, we obtain the optimized hardware parameters. Subsequently, we utilize these parameters along with model information to generate hardware-executable codes via the compiler. This process is similar to the single-stage search method (SSAT) for small-scale networks. Following this, we employ these codes to obtain hardware results from a selected training dataset on the chips and calculate the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the software and hardware results. This allows us to identify the optimal IT that corresponds to the minimum MSE. Unlike the on-chip search for small-scale networks in SSAT, since a relatively suitable IT has already been found during the SIL search (‘SIL-optimal IT(SIT)’ in Algorithm 2), there is no need to start from the minimum value. Instead, we only need to search in the vicinity of the IT optimized by the SIL search. We control the search space through a threshold (‘Threshold’ in Algorithm 2). In this work, we set the threshold as 500 ns for ResNet-32. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. S16, the on-chip search effectively mitigates the impact of differences between various layers within the same system and across different systems of the same layer. In addition, as shown in Fig. 4d, the on-chip experiments indicate that the second-stage method can further reduce the MSE by 15.54% on average for all on-chip layers of ResNet-32 compared to that with only simulator-in-the-loop optimization.

Algorithm 2 | Chip-in-loop search in PTSS

1: Input: Model File; Hardware initial configurations; Software Results on a subset of training dataset; Threshold (>=0); SIL-optimal IT(SIT)

2: Run the CIM compiler and obtain the runnable codes

3: Get the IT search range: (SIT - Threshold, SIT + Threshold)

3: for (layer in all on-chip layers) do

4: for (IT in IT search range) do

5: Use IT to get hardware runnable codes

6: Perform fully MAC on hardware with the given training dataset. And obtain the chip results

7: Calculate the mean square error: Ecur of chip results and software results and record it.

8: end for

9: Get the IT corresponding to the lowest Ecur and record it.

10: end for

11: Output: The IT set corresponding to lowest Ecur of all on-chip layers

Data availability

The datasets for image classification and text classification are publicly available32,41,42. The datasets for image segmentation and object detection are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14818995. Source data are provided with this paper. Other data that support the findings of this study are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14823197. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The software framework codes in this article, including compiler, optimizer, simulator, and trainable modules are available at https://github.com/Tsinghua-LEMON-Lab/OpenCIMTC / (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14823197).

References

Schwartz, R., Dodge, J., Smith, N. A. & Etzioni, O. Green AI. Commun. ACM 63, 54–63 (2020).

Stoica I. et al. A Berkeley View of Systems Challenges for AI. https://www2.eecs.berkeley.edu/Pubs/TechRpts/2017/EECS-2017-159.html (2017).

Horowitz M. 1.1 computing’s energy problem (and what we can do about it). In: 2014 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference Digest of Technical Papers (ISSCC) (ed. Laura, C. F.) 10–14 (IEEE, 2014).

Chi, P. et al. Prime: a novel processing-in-memory architecture for neural network computation in reram-based main memory. ACM SIGARCH Computer Architecture News 44, 27–39 (2016).

Li, W. et al. Timely: pushing data movements and interfaces in pim accelerators towards local and in time domain. In: Proceedings of the 47th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA) (ed. O’Conner, L.) 832–845 (IEEE, 2020).

Shafiee, A. et al. ISAAC: a convolutional neural network accelerator with in-situ analog arithmetic in crossbars. ACM SIGARCH Computer Architecture News 44, 14–26 (2016).

Yang, T.-H. et al. Sparse ReRAM engine: joint exploration of activation and weight sparsity in compressed neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 46th International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA) (ed. Srilatha (Bobbie), M.) 236–249 (IEEE, 2019).

Jia, H. et al. Scalable and programmable neural network inference accelerator based on in-memory computing. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 57, 198–211 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Edge learning using a fully integrated neuro-inspired memristor chip. Science 381, 1205–1211 (2023).

Lin, Y. et al. Uncertainty quantification via a memristor Bayesian deep neural network for risk-sensitive reinforcement learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 714–723 (2023).

Ambrogio, S. et al. An analog-AI chip for energy-efficient speech recognition and transcription. Nature 620, 768–775 (2023).

Le Gallo, M. et al. A 64-core mixed-signal in-memory compute chip based on phase-change memory for deep neural network inference. Nat. Electron. 6, 680–693 (2023).

Yao, P. et al. Face classification using electronic synapses. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–8 (2017).

Joshi, V. et al. Accurate deep neural network inference using computational phase-change memory. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–13 (2020).

Yao, P. et al. Fully hardware-implemented memristor convolutional neural network. Nature 577, 641–646 (2020).

Wan, W. et al. A compute-in-memory chip based on resistive random-access memory. Nature 608, 504–512 (2022).

Sheridan, P. M. et al. Sparse coding with memristor networks. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 784–789 (2017).

Rosenblatt, F. Principles of Neurodynamics. Perceptrons and the Theory of Brain Mechanisms. (Cornell Aeronautical Lab Inc, Buffalo NY, 1961).

LeCun, Y. & Bengio, Y. Convolutional networks for images, speech, and time series. Handb. Brain Theory Neural Netw 3361, 1995 (1995).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer. P. & Brox, T. U-net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) (ed. Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W. M. & Frangi, F. A.) 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

Deng, J., Guo, J., Ververas, E., Kotsia, I. & Zafeiriou, S. Retinaface: single-shot multi-level face localisation in the wild. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (ed. O’Conner, L.) 5202–5210 (IEEE, 2020).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (ed. O’Conner, L.) 770–778 (IEEE, 2016).

Ankit, A. et al. PUMA: a programmable ultra-efficient memristor-based accelerator for machine learning inference. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems (ASPLOS) (ed. Papagiannopoulou, D.) 715–731 (ACM, 2019).

Drebes, A. et al. TC-CIM: empowering tensor comprehensions for computing-in-memory. In: 2020 10th International Workshop on Polyhedral Compilation Techniques (IMPACT) (eds Clauss, P. & Iooss, G.) (2020).

Siemieniuk, A. et al. OCC: an automated end-to-end machine learning optimizing compiler for computing-in-memory. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits Systems (ed. Atienza, D.) Vol. 6, 1674–1686 (2021).

Sun, X. et al. XJapa. PIMCOMP: A Universal Compilation Framework for Crossbar-based PIM DNN Accelerators. In: Proceedings of the 60th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC) (IEEE, 2023).

Zhou, C. et al. ML-HW Co-Design of Noise-Robust TinyML Models and Always-On Analog Compute-in-Memory Edge Accelerator. IEEE Micro 42, 76–87 (2022).

Rasch, M. J. et al. Hardware-aware training for large-scale and diverse deep learning inference workloads using in-memory computing-based accelerators. Nat. Commun. 14, 5282 (2023).

Le Gallo, M. et al. Using the IBM analog in-memory hardware acceleration kit for neural network training and inference. APL Mach. Learn. 1, 041102 (2023).

Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: an imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In: Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS) (ed. Garnett, R.) 8026–8037 (Curran Associates Inc., 2019).

Krizhevsky, A. & Hinton, G. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/learning-features-2009-TR.pdf (2009).

Man, K.-F., Tang, K.-S. & Kwong, S. Genetic algorithms: concepts and applications [in engineering design]. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 43, 519–534 (1996).

Chen, T. et al. TVM: an automated end-to-end optimizing compiler for deep learning. In: Proceedings of 13th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI) (eds Arpaci-Dusseau, A. & Voelker, G.) 579–594 (USENIX Association, 2018).

Vasilache, N. et al. Tensor comprehensions: framework-agnostic high-performance machine learning abstractions. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/1802.04730 (2018).

Feng, S. et al. TensorIR: An Abstraction for Automatic Tensorized Program Optimization. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems (ASPLOS) (eds Aamodt, T. M., Jerger, N. E. & Swift, M.) 804–817 (ACM, 2023).

Ben-Kiki, O. et al. Yaml ain’t markup language (yaml™) version 1.2. https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/s3fs-public/imported/YAML%201.2%20Spec.pdf (2009).

Esterbrook, C. Using mix-ins with python. Linux Journal 2001(84es), 7-es (2001).

Cummins, C. et al. Compilergym: robust, performant compiler optimization environments for ai research. In: Proceedings of 2022 IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Code Generation and Optimization (CGO) (eds. Lee, J. W., Hack, S. & Shpeisman, T.) 92–105 (IEEE, 2022).

Sun, H. et al. Minimizing communication conflicts in network-on-chip based processing-in-memory architecture. In: Proceedings of 2023 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE) (ed. Vatajelu, I.) (IEEE, 2023).

LeCun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y. & Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 86, 2278–2324 (1998).

Rousseau, F., Kiagias, E. & Vazirgiannis, M. Text categorization as a graph classification problem. In: Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (eds. Zong, C. & Strube, M.) 1702–1712 (ACL, 2015).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by the STI 2030 – Major Projects (2021ZD0201205) (H.W.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China the NSFC 62025111 (H.W.), 62422405 (P.Y.), 92164302 (D.W.), the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (H.W.), and the Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Integrated Circuits.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.Y. proposed the idea, and conducted the measurements and model training; Z.W., Z.H., and S.D. designed the hardware system; Q.L., P.Y., and D.W. designed the memristor chip; R.Y. and T.G. developed the software framework; R.Y., Z.W., Z.H., Q.Q., J.Z., and Q.Z. contributed to the data analysis; B.G., J.T., and H.W. supervised the whole project; R.Y. and B.G. wrote the manuscript and all authors contributed to the manuscript editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, R., Wang, Z., Liu, Q. et al. A full-stack memristor-based computation-in-memory system with software-hardware co-development. Nat Commun 16, 2123 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57183-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57183-0

This article is cited by

-

Biomimetic Synapses Based on Halide Perovskites for Neuromorphic Vision Computing: Materials, Devices, and Applications

Nano-Micro Letters (2026)

-

Multisensory Neuromorphic Devices: From Physics to Integration

Nano-Micro Letters (2026)