Abstract

Marginally twisted bilayer graphene with large Bernal stacked domains involves symmetry-breaking features with domain boundaries that exhibit topological edge states normally obscured by trivial bands. A vertical electric field can activate these edge states through inversion symmetry breaking and opening a bandgap around the edge state energy. However, harnessing pristine topological states at the Fermi level without violent electric or magnetic bias remains challenging, particularly above room temperature. Here, we demonstrate that thermal biasing can break the vertically stacked lattice symmetry of twisted bilayer graphene via the interatomic Seebeck effect, enabling thermoelectric imaging of topological edge states at tunable Fermi levels above room temperature. The high spatial resolution in the imaging is achieved through atomic-scale thermopower generation between a metallic tip and the sample, reflecting the local electronic band structure and its derivative features of twisted bilayer graphene at the Fermi level. Our findings suggest that thermal biasing provides a sensitive, non-destructive method for symmetry breaking and topological state imaging above room temperature, making it a practical and accessible approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Symmetry breaking in condensed matter systems is essential for understanding and designing diverse material properties, including magnetism, ferroelectricity, superconductivity, and topological features1,2. A notable example of symmetry breaking is the bandgap opening process in bilayer graphene with Bernal stacking3,4. Both single-layer and bilayer graphene naturally lack a bandgap, thus being classified as semimetals, which poses a challenge for developing switching devices (e.g., transistors) in the industry. However, by applying a vertical electric field, researchers have successfully induced a bandgap in bilayer graphene by breaking the AB lattice symmetry in the Bernal stacking5,6,7. This breakthrough has enabled the achievement of high on/off switching ratios, demonstrating the potential of manipulating the symmetry of materials for advanced electronic applications8,9.

When artificially stacking two single-layer graphene flakes, introducing a twist angle between the flakes forms twisted bilayer graphene (TBG) with periodic Bernal stacked domains (AB and BA)10. Various correlated states, such as superconductivity, Mott insulating states, and magnetic orders, have been observed in TBG at certain twist angles (e.g., magic angle of 1.1°)11,12,13,14,15, making it a promising candidate for emerging quantum devices14,16,17. In particular, electronic flat bands are achieved in TBG, which holds the potential for efficient thermoelectric power generation based on the heterostructure18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. Moreover, topologically protected helical edge states are present at the domain boundaries in the Bernal stacked TBG27,28,29,30,31. To exploit the topological states and flat bands for highly performing thermoelectric devices, appropriate bandgaps are required in TBG; thus, breaking the AB lattice symmetry of the Bernal stacked domains is a critical step for TBG-based topological thermoelectric devices.

While macroscopic features of the topological states and flat bands in TBG have been investigated through electric and thermoelectric transport studies within device geometries, their microscopic characteristics and roles in practical devices operating at room temperature remain largely unexplored. Previous attempts to study the topological states at a microscopic level using scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) have been reported32,33,34,35,36,37,38. However, these studies were conducted at low temperatures (T < 5 K) and required high electric and magnetic biases to break the AB lattice symmetry, which is not ideal for probing subtle topological states at the Fermi level and is impractical for electronic and thermoelectric device applications at room temperature.

A narrow bandgap is required to observe topological states at the Fermi level and to realize high thermoelectricity performance using the unique electronic states, surpassing the Mahan-Sofo limit39,40,41,42,43. In that research direction, various topological insulators with narrow bandgaps, including bismuth telluride (Bi2Te3)44,45,46,47, antimony telluride (Sb2Te3)48,49,50, bismuth selenide (Bi2Se3)45,51,52, and tin telluride (SnTe)53,54,55,56, have been investigated on the device scale. We note that such device scale studies are inadequate for precisely examining the thermopower from the local, topologically protected helical edge states in the above materials as well as TBG, requiring a way to probe local thermoelectric features from the edge states with a spatial resolution of 1 nm.

In this study, we report on the symmetry breaking and bandgap opening in TBG through vertical thermal biasing and the thermoelectric imaging of topologically protected helical edge states in TBG above room temperature (T > 320 K). Instead of using large external electric fields, the interatomic layer Seebeck effect across the Bernal stacked atomic layers and their interface with a metallic tip was used to break the AB lattice symmetry. Utilizing our scanning thermoelectric microscopy (SThEM) system, which enables atomic-scale mapping of thermopower based on the local electronic structures57,58,59,60, we could visualize domain boundaries and their role in the formation of topological states at the atomic scale in TBG. The SThEM images were interpreted using our first-principles and tight-binding calculations, incorporating numerous carbon atoms in the TBG system. This thermal biasing and thermoelectric imaging method provides a sensitive and non-destructive approach for symmetry manipulation and investigating locally present, pristine, and practical topological states at high temperatures.

Results

We prepared various TBG rotational geometries in a single sample, with rotation angles ranging from 0° to 2°. This range was confirmed by Raman spectra (Supplementary Fig. S3). To maintain an atomically clean and flat surface for SThEM measurements, a graphite back gate electrode, a gate dielectric (a hexagonal boron nitride, h-BN, layer of 40 nm), and gold source/drain electrodes for the tunneling current channel were prepared using the stamp method61, avoiding additional electron-beam lithography. After the fabricated device was transferred inside the ultrahigh vacuum chamber of our SThEM, mild annealing at a temperature of T = 373 K was performed. This process did not alter the twist angle or the Bernal stacking order in the samples62.

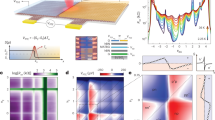

A schematic illustration of thermal biasing and thermoelectric imaging is shown in Fig. 1A. To generate the thermal bias and interlayer thermoelectric effect, and to conduct device characterization, a specially designed sample holder for the TBG was used. During SThEM experiments, the sample holder was heated to a specific temperature, while the platinum-coated metallic cantilever (tip) was maintained at T = 300 K. This creates a temperature gradient (ΔT = Tsample-Ttip) between the sample and tip. The position-dependent Seebeck coefficient and effective temperature drop at the interface between the tip and sample enable the mapping of thermoelectric voltage (or thermopower as referred to in our study), where electron and heat transport in a coherent way58. The thermoelectric voltage was measured using a high-impedance voltmeter connected between the tip and the sample.

A Experimental Setup of our UHV-SThEM, modified by the contact-mode AFM system (Scienta Omicron VT-SPM). The tip and sample are thermally decoupled in the system. The temperature gradient between the tip (Ttip) and sample (Tsample) induces thermoelectric voltages. The in-plane transport of the sample can be measured by the separately connected SMU (source-measure unit). B The measured thermoelectric voltage (ΔV)-temperature gradient (ΔT = Tsample-Ttip) curve of a TBG region with a twist angle of 1.1° above room temperature. The tip was maintained as Ttip = 300 K while the sample was heated. The positive slope yields a thermopower (Seebeck coefficient) of +8.94 μV/K, indicating slight p-type doping of the intrinsic TBG on a h-BN. C Schematic image for the possible stacking orders of TBG with a small twist angle. D Thermopower mapping image of TBG with an averaged twisted angle of 1.1° with a ∆T = 20 K. E, F Thermopower mapping images of TBG with a twisted angle of 0.3° and 0.07°, respectively. The different twist angles were obtained at different regions in a single TBG sample.

According to previous studies, a moderate temperature gradient (ΔT ≈ 30 K) created by heating the sample holder produces a uniform temperature distribution across the surface60. Thus, the resulting ΔV mapping reflects the local density of states and their derivatives (i.e., local Seebeck coefficient) at the Fermi level in SThEM experiments57. By adjusting the back gate voltage, thermopower measurements at various electron densities and Fermi levels can be mapped. The above method is critical for probing local topological edge states within a specific energy range near the Fermi level.

The average thermopower of the TBG sample as a function of ΔT is shown in Fig. 1B. A Seebeck coefficient of +8.94 μV/K is derived from the positive slope of the data points in Fig. 1B, indicating p-type characteristics of the TBG sample. It is important to note that the thermopower was calculated from the slope of the data points rather than the absolute values on the y-axis. The thermopower data in Fig. 1B includes an instrumental offset voltage inherent in our measurements59. This offset voltage (0.646 mV) was carefully estimated under a zero-temperature gradient (ΔT = 0 K) and subtracted from the subsequent thermopower data.

The TBG consists of three lattice configurations: AA, AB/BA, and saddle point (SP). A schematic of these symmetries is shown in Fig. 1C. It has been found that the Bernal stacking order (i.e., AB/BA) results in the lowest interlayer energy. Consequently, the TBG maximizes the Bernal stacking area, forming a triangular domain structure with alternating AB and BA stacking orders. This configuration is the most stable structure for small twist angles (<2°)63, as schematically depicted in Fig. 1C.

Figure 1D–F shows thermopower mappings of three representative areas of the TBG sample with different twist angles, obtained with a temperature gradient of ΔT = 20 K (Ttip = 300 K and Tsample = 320 K). Two critical features are noted in Fig. 1D–F. First, domain boundaries are clearly visible in the thermopower mappings at low twist angles (<1°), indicating that a bandgap has opened due to the AB/BA lattice symmetry breaking. It has been reported that the underneath substrate (the gate dielectric, h-BN) can also break the lattice symmetry with a certain rotation angle.

We interpret thermal biasing as the origin of the lattice symmetry breaking and the resulting bandgap opening (Fig. 1A). The vertical and parallel temperature distribution in the TBG sample can be understood as follows. When the tip contacts the heated sample, the significant difference in thermal conductivity between the in-plane and out-of-plane direction, originating from the layered geometry of graphene, causes a vertical temperature difference between graphene layers. However, the long phonon mean free path of graphene in the lateral direction maintains a uniform temperature over a large area in the TBG, resulting in simultaneous symmetry breaking in the AB and BA domains.

It is known that the sensitivity of SThEM measurements depends on variations in the density of states at the Fermi level, even in small bandgap cases57,58,60. If the bandgap had not opened or there were no thermal biasing (no temperature drop), the thermopower variation from the edge states at domain boundaries would be negligible, as shown in Supplementary Figs. S5 and S7. In no bandgap cases, the thermopower is dominated by numerous bulk states (i.e., trivial bilayer graphene bands), preventing the unique spatial variation of thermopower observed in Fig. 1D–F.

Second, the three lattice configurations–AA, AB/BA, and SP–are distinctly resolved in the thermopower mappings. SP regions are visible through the imaging of topological edge states. Additionally, the dark and bright areas in the thermopower mappings are inverted compared to the current mappings (Supplementary Fig. S6) and STM topography images of TBG samples34,64,65. For instance, the dark areas (circles) or regions with the most negative thermopower (see the color scale bar) indicate AA stacked regions in the thermopower mappings (Fig. 1D–F), which appear bright in previous STM images.

The opposite contrast can be understood by the physical origin of the thermopower mapping, which follows the formula58 for the Seebeck coefficient S: \(S=-\frac{1}{\left|e\right|T}\frac{\int N\left(E\right)\left(-\partial f/\partial E\right)(E-{E}_{F}){dE}}{\int N\left(E\right)\left(-\partial f/\partial E\right){dE}}\), where T is the temperature, N(E) is the local density of states at an energy of E, \(\partial f/\partial E\) is the energy derivative of the Fermi-Dirac distribution, and EF is the Fermi level. According to the above formula, a large local density of states with little variation makes a diminutive thermoelectric voltage (thermopower). Thus, AA stacked regions that appear as bright regions in STM images are observed as dark regions in Fig. 1D–F.

The twist angle was determined by estimating the moiré wavelength of the TBG in our study, using the formula: \(\lambda=\frac{a}{2\sin \frac{\Theta }{2}}\), where \(\lambda\) is moiré wavelength, \(\Theta\) is twist angle, and a is the lattice constant (2.46 Å). At a twist angle near the magic angle (1.1°), as shown in Fig. 1D, the bright regions (i.e., Bernal stacked and SP regions) form a hexagonal arrangement in the thermopower mapping.

While the Bernal stacked and SP regions appear merged at the magic angle twist in Fig. 1D, these regions are spatially resolved in the thermopower mappings of different areas of the TBG with smaller twist angles. Thermopower mapping images with twist angles of 0.3° and 0.07° are presented in Fig. 1E, F, respectively. At these smaller twist angles, the Bernal stacked regions exhibit a more positive thermopower than the AA-stacked region, owing to the band gap opening. The sharp DOS variation at the band edge near the Fermi level gives rise to the enhanced thermopower. Besides, the SP regions form a triangular network with a maximal thermopower (the brightest color) contributed by the topological edge states. A consistent feature across all three thermopower mappings (Fig. 1D–F) is that both the Bernal stacked and SP regions appear brighter than the AA regions.

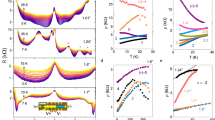

We conducted an intensive investigation of thermopower mapping of a TBG region at a twist angle of 0.28° under various back gate voltages (Vgate) and Fermi levels, as depicted in Fig. 2A–C. It has been reported that TBG exhibits diverse electronic phases corresponding to different twist angles and Fermi levels65,66,67. The SThEM images in Fig. 2A–C reveal several defects, which are naturally occurring impurities within the TBG sample. These defects were used as reference points to maintain consistent imaging of the same area across different gate voltages, which is a process that requires several hours for accurate SThEM measurements.

A–C Thermopower mapping images with Vgate of 0, 1.5, and 2.5 V, respectively. The nominal temperature difference between the sample and tip is ΔT = 20 K (Ttip = 300 K and Tsample = 320 K). The AB and BA stacking orders produce different contrasts from the underlying h-BN substrate, depending on Vgate. The TBG region is charge neutral at Vgate = 0 V in three mapping images. Three lines (red, blue, and black) are to exhibit the line profiles in ‘Fig. 3’.

The transfer curve of the TBG device (used for all the SThEM measurements in this study) demonstrates both electron- and hole-driven currents with a charge neutrality point observed around a Vgate = 0 V (Supplementary Fig. S4). This indicates that the intrinsic Fermi level resides within the bandgap and intersects the topological edge states activated by thermal biasing at zero gate bias. Thus, the local thermopower near the domain boundary is expected to be dominated by the topological edge states at the Fermi level in the TBG, as depicted in Fig. 2A. To further explore the roles of bulk states versus topological edge states in local thermopower generation, we conducted the same measurements at different Vgate values, illustrated in Fig. 2B (Vgate = 1.5 V) and 2C (Vgate = 2.5 V).

The thermopower mapping in TBG exhibits consistent features across different gate voltages, including dark AA stacked regions and bright triangular Bernal stacked regions, with the topological edge states specifically in the SP regions. The slight variation in domain contrast between AB and BA Bernal stacked regions in Fig. 2B can be attributed to the h-BN substrate-induced strain. This substrate effect affects the AB and BA domain contrast, which is less pronounced at Vgate = 2.5 V (where the Fermi level is raised due to an increase in bulk state electrons within the TBG), as observed in Fig. 2C. In the high gate bias, AA stacked regions exhibit reduced dark contrast and display a six-fold star-shaped pattern indicative of local states.

A striking feature in Fig. 2C is the double-ridge structure exhibited by the SP regions in thermopower mapping at Vgate = 2.5 V, reminiscent of the topological edge states observed by STM at low temperatures. Two key features can be highlighted: (1) the mapping of topological edge state is achieved at Tsample = 320 K, demonstrating the robustness of these topological states under thermal biasing conditions, and (2) unlike STM measurements, the observation of the double-ridge structure in thermopower mapping under thermal biasing requires addition gating or increased electron accumulation in TBG.

We conducted theoretical studies on TBG using a combination of tight-binding and first-principles calculations to elucidate the unique thermopower generation from topological edge states. Our calculations confirmed the presence of bandgap (25 meV) and nontrivial topological edge states in TBG under an external electric field, which is consistent with previous findings (Fig. 3A, B). The bandgap (25 meV) of TBG could be theoretically estimated to explain the measured Seebeck coefficients shown in Fig. 3C, D. A smaller bandgap cannot produce the experimentally obtained Seebeck coefficient of TBG in the SThEM.

A Schematic image of bilayer graphene boundary with topologically protected helical edge states. The different valley Chern numbers in the AB and BA stacking regions lead to the topological edge states for K (red arrows) and K’ (blue arrows) valleys, as shown in the real space. B Band structure of bilayer graphene with a vertical electric field. The topological edge states at K and K’ valley with a bandgap Δ are shown in the reciprocal space. The Fermi level is marked with a black dashed line. C Calculated local charge density and thermopower. The position at 0 nm is set to be the saddle point. The AB and BA stacked regions are the left and right sides of the domain. D Matching the measured local thermopower with different Vgate values (thicker curves) along the colored line in ‘Fig. 2’, with the theoretical results (thinner curves). The AB and BA regions’ asymmetry, originating from the h-BN substrate, is not considered in the calculation.

In TBG, different valley Chern numbers emerge in the two Bernal stacking orders (AB and BA) when inversion symmetry is broken68. This variation in valley Chern number gives rise to the topologically protected helical edge states at domain boundaries, illustrated in Fig. 3A. Based on atomic geometry and electronic states, we theoretically determined microscopic thermopower and electronic density of states, presented in Fig. 3C, D. Further details regarding the calculations are provided in the Methods and Supplementary Materials.

Given that measurements were done at Tsample = 320 K, we used the Fermi-Dirac distribution function to assess the contribution of topological edge states within a specific energy window at Vgate = 0 V. This energy window typically spans approximately four times the thermal energy (~100 meV in this case) with the distribution function. In the upper panel of Fig. 3C, the electronic density of states of edge states at Vgate = 0 V is displayed along a vertical line intersecting the edge, shown as a red line in Fig. 2A. Notably, the full width at half maximum of the heightened electronic density region near the domain boundary (or SP region) measures 12 nm, revealing a double-ridge structure consistent with observations from low-temperature STM studies.

However, the thermopower mapping with Vgate = 0 V in the simulation shows a maximum at the domain boundary (x = 0) without exhibiting the double-ridge structure, as depicted in the lower panel in Fig. 3C. Apart from the domain boundary, the Seebeck coefficient becomes featureless due to the constant electronic states at the Fermi level within the domain. The experimental thermopower result with Vgate = 0 V in Fig. 3D (thick red curve) corresponds well with the simulated thermopower curves (thin red curve) with a bandgap of 25 meV also shown in the lower panel in Fig. 3C. Additional experimental thermopower line profiles and theoretical simulation results with different gate voltages are present in Fig. 3D. As Vgate increases, electron accumulation in TBG also increases, leading to a more negative thermopower (indicating more n-type characteristics), which is consistent with experimental findings.

The thermopower difference between AB and BA stacking order regions is 60 μV with Vgate = 1.5 V, which varies with gate bias. In our theoretical calculation, we did not account for the effect of the h-BN substrate to reproduce the asymmetry observed in Fig. 3D. This substrate-induced asymmetry diminishes at an elevated Vgate = 2.5 V, where the SP regions or the domain boundaries exhibit a double-ridge structure.

Our theoretical simulations accurately reproduce the double-ridge feature with increased electron accumulation for thermopower generation at the elevated Vgate (black curves in Fig. 3D). This thermopower pattern at Vgate = 2.5 V is similar to the double-ridge structure observed in the local density of states at Vgate = 0 V shown in the upper panel in Fig. 3C. Hence, the topological edge states contribute distinctly to the local density of states and thermopower characteristics under varying conditions in our SThEM measurements.

The nominal temperature difference between the tip and TBG (ΔT = 20 K), as set in the experiment, does not fully account for the relationship between the thermopower (left-side y-axis values) and the calculated Seebeck coefficients (right-side y-axis values) in Fig. 3D. The actual temperature drop between the tip and TBG, obtained by the left- and right-side y-axis values) could be estimated to be 5 K instead of 20 K. Similar discrepancies in temperature scales have been noted in former SThEM studies. It can be understood by additional temperature drops within the tip and between the two TBG atomic layers.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the use of thermal bias to induce symmetry breaking and open a bandgap in Bernal stacked TBG and mapped local thermopower generation from the topological edge states in TBG above room temperature. We have observed distinct gate-dependent thermopower features, contrasting with previous low-temperature studies based on STM. The extensive presence of carbon atoms in AB/BA domains and their boundaries have been considered in our combined tight-binding and first-principles calculations, which accurately simulate the local thermopower characteristics.

Methods

Sample preparation for SThEM measurement

The device was fabricated using a stamp method (tear and stack)61. Graphene and hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) were initially exfoliated onto a SiO2/Si substrate. The stamp was constructed from a polycarbonate (PC) film and polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) layered on a glass slide. After the h-BN (thickness: 40 nm) was picked up with the stamp, van der Waals forces were employed to pick up the graphite intended for the back gate. Subsequently, the h-BN designated for the dielectric was picked up, and half of the monolayer graphene was torn and lifted. The remaining graphene flake on the Si substrate was then rotated by 1.1° before being picked up. The resulting stack with PC was transferred onto a new SiO2/Si substrate.

The gold electrode with a thickness of 155 nm was transferred onto the twisted bilayer graphene for the electrical transport experiment and to ensure a clean surface, following procedures69,70. After the sample was transferred to an ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) chamber, the twisted bilayer graphene sample was annealed at a mild temperature (~100 °C) to prevent the recovery of Bernal stacking order and alteration of the twisted angle62.

SThEM measurement

The scanning thermoelectric microscopy (SThEM) experiments were performed using a Scienta Omicron VT-SPM system operating at a base pressure of 10−11 torr. The system’s STM preamplifier was modified to incorporate a high-impedance electrometer (Keithley 6517B). Platinum-coated metallic cantilevers were used for all measurements, with the metallic tip kept at ambient temperature. To establish a nominal temperature gradient at the tip-sample interface, the TBG sample was heated with a PBN resistive heater.

The thermoelectric voltage generated due to the temperature gradient was measured using a high-impedance electrometer in contact-AFM mode, employing a constant force feedback loop. Both surface height variations and thermoelectric voltage mappings were acquired simultaneously during the scanning process. The applied contact force ranged from 10−9 to 10−11 N, ensuring negligible thermal coupling between the tip and the sample. This setup guaranteed a constant temperature difference at the tip-sample interface throughout the scanning procedure.

SThEM simulation

First-principles simulations of SThEM were calculated in three steps. First, the density functional theory (DFT) calculations in primitive unit cells of bilayer graphene with different stacking order. Eleven structures, including SP, were calculated, where the structures were interpolated from AB and BA. Next, the model Hamiltonians, which describe the domain wall between AB and BA, were constructed using effective Hamiltonians obtained from the DFT calculations. The domain wall structure was taken as a periodic 1D line defect with the wavelength adopted from the experiment. Finally, the Seebeck coefficient as a function of the virtual tip position was evaluated from the electronic structure of the domain wall.

The DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) with projector-augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials71,72. The exchange-correlation energy was evaluated using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional with the DFT-D4 dispersion correction to capture interlayer interaction73,74. The kinetic energy cutoff was 1200 eV, and the k-points sampling was done on 30 × 30 × 1, Γ-centered mesh. All atoms in the AB and BA structures were relaxed until the maximum Hellman-Feynman force was less than 0.01 eV/Å. Intermediate atomic structures, including SP, were obtained by linearly interpolating the coordinates of atoms. The vacuum lengths of more than 16 Å were employed to prevent spurious interaction between bilayer graphenes. An effective Hamiltonian was obtained for each structure by projecting the Kohn–Sham Hamiltonian onto four pz-like maximally localized Wannier functions (MLWFs) using the Wannier90 code75.

The domain wall model was constructed by connecting the effective Hamiltonians of the local structures. The interaction between two MLWFs in different local structures was modeled by the interaction strength of the middle structure. The unit cell shape was taken to be a 1D strip containing two domain walls with periodic boundary conditions, resulting in alternating AB and BA regions without spurious open boundaries. The model consists of a 29.6 nm AB region, a 7.39 nm domain wall region, a 29.6 nm BA region, and another 7.39 nm domain wall region. This size corresponds to a moiré wavelength of 73.9 nm, equivalent to a stacking angle of 0.19°. The chemical potential of each layer was modified to simulate a uniform electric field of 0.05 mV/Å without screening, as thermal biasing is expected to cover multiple unit cells. The electronic structure was calculated using exact diagonalization.

The tip-sample Seebeck coefficient S was calculated using the Landauer formula with the Tersoff-Hamann approximation as follows58.

Here, T is the temperature, N(E) is the local density of states at an energy of E, \(\partial f/\partial E\) is the energy derivative of the Fermi-Dirac distribution, and EF is the Fermi level. Since the system is effectively one-dimensional, 1 × 3201 × 1 Γ-centered mesh k-points sampling was used to calculate N(E). For the Brillouin zone integration, the optimized tetrahedron method was employed76.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary information

References

Du, L. et al. Engineering symmetry breaking in 2D layered materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 193–206 (2021).

Ideue, T. & Iwasa, Y. Symmetry breaking and nonlinear Electric transport in van der Waals nanostructures. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 12, 201–223 (2021).

Ohta, T., Bostwick, A., Seyller, T., Horn, K. & Rotenberg, E. Controlling the electronic structure of bilayer graphene. Science 313, 951–954 (2006).

Zhou, S. Y. et al. Substrate-induced bandgap opening in epitaxial graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 770–775 (2007).

Castro, E. V. et al. Biased bilayer graphene: semiconductor with a gap tunable by the electric field effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 216802 (2007).

Oostinga, J. B., Heersche, H. B., Liu, X., Morpurgo, A. F. & Vandersypen, L. M. Gate-induced insulating state in bilayer graphene devices. Nat. Mater. 7, 151–157 (2008).

Zhang, Y. et al. Direct observation of a widely tunable bandgap in bilayer graphene. Nature 459, 820–823 (2009).

Jang, H., Kim, H., Kim, G., Cho, S. & Yang, H. 2D amorphous solids for sub-nanometer scale devices. Nano Converg. 11, 46 (2024).

Cho, W. et al. Singular hall response from a correlated ferromagnetic flat nodal‐line semimetal. Adv. Mater. 36, 2402040 (2024).

Andrei, E. Y. & MacDonald, A. H. Graphene bilayers with a twist. Nat. Mater. 19, 1265–1275 (2020).

Cao, Y. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 43–50 (2018).

Po, H. C., Zou, L., Vishwanath, A. & Senthil, T. Origin of Mott Insulating Behavior and Superconductivity in Twisted Bilayer Graphene. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031089 (2018).

Saito, Y., Ge, J., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Young, A. F. Independent superconductors and correlated insulators in twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 16, 926–930 (2020).

Gonzalez-Arraga, L. A., Lado, J. L., Guinea, F. & San-Jose, P. Electrically controllable magnetism in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 107201 (2017).

Lu, X. et al. Superconductors, orbital magnets and correlated states in magic-angle bilayer graphene. Nature 574, 653–657 (2019).

Yu, Y. et al. Tunable angle-dependent electrochemistry at twisted bilayer graphene with moire flat bands. Nat. Chem. 14, 267–273 (2022).

Yin, J. et al. Selectively enhanced photocurrent generation in twisted bilayer graphene with van Hove singularity. Nat. Commun. 7, 10699 (2016).

Mahapatra, P. S., Sarkar, K., Krishnamurthy, H. R., Mukerjee, S. & Ghosh, A. Seebeck coefficient of a single van der Waals junction in twisted bilayer graphene. Nano Lett. 17, 6822–6827 (2017).

Paul, A. K. et al. Interaction-driven giant thermopower in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 18, 691–698 (2022).

Ghawri, B. et al. Breakdown of semiclassical description of thermoelectricity in near-magic angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Commun. 13, 1522 (2022).

Ghawri, B. et al. Non-Boltzmann thermoelectric transport in minimally twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 109, 045436 (2024).

Mahapatra, P. S. et al. Misorientation-controlled cross-plane thermoelectricity in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 226802 (2020).

Mahapatra, P. S. et al. Quantum hall interferometry in triangular domains of marginally twisted bilayer graphene. Nano Lett. 22, 5708–5714 (2022).

Kumar, N., Chaudhuri, A., Arya, V., Bakli, C. & Bera, C. Significantly reduced thermal conductivity and enhanced thermoelectric performance of twisted bilayer graphene. J. Appl. Phys. 134, 044301 (2023).

Kommini, A. & Aksamija, Z. Very high thermoelectric power factor near magic angle in twisted bilayer graphene. 2D Mater. 8, 045022 (2021).

Merino, R. L. et al. Evidence of heavy fermion physics in the thermoelectric transport of magic angle twisted bilayer graphene. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.11749 (2024).

Yoo, H. et al. Atomic and electronic reconstruction at the van der Waals interface in twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Mater. 18, 448–453 (2019).

Kazmierczak, N. P. et al. Strain fields in twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Mater. 20, 956–963 (2021).

Xu, S. G. et al. Giant oscillations in a triangular network of one-dimensional states in marginally twisted graphene. Nat. Commun. 10, 4008 (2019).

San-Jose, P. & Prada, E. Helical networks in twisted bilayer graphene under interlayer bias. Phys. Rev. B 88, 121408 (2013).

Efimkin, D. K. & MacDonald, A. H. Helical network model for twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 98, 035404 (2018).

Kerelsky, A. et al. Maximized electron interactions at the magic angle in twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 572, 95–100 (2019).

Jiang, Y. et al. Charge order and broken rotational symmetry in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 573, 91–95 (2019).

Xie, Y. et al. Spectroscopic signatures of many-body correlations in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 572, 101–105 (2019).

Choi, Y. et al. Electronic correlations in twisted bilayer graphene near the magic angle. Nat. Phys. 15, 1174–1180 (2019).

Oh, M. et al. Evidence for unconventional superconductivity in twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 600, 240–245 (2021).

Ju, L. et al. Topological valley transport at bilayer graphene domain walls. Nature 520, 650–655 (2015).

Zheng, Q. et al. Tunable sample-wide electronic kagome lattice in low-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 076803 (2022).

Ding, S., Chen, X., Xu, Y. & Duan, W. The best thermoelectrics revisited in the quantum limit. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 189 (2023).

Takahashi, R. & Murakami, S. Thermoelectric transport in topological insulators. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 27, 124005 (2012).

Xu, Y., Gan, Z. & Zhang, S. C. Enhanced thermoelectric performance and anomalous seebeck effects in topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 226801 (2014).

Müchler, L., Casper, F., Yan, B., Chadov, S. & Felser, C. Topological insulators and thermoelectric materials. Phys. Status Solidi RPL 7, 91–100 (2012).

Ivanov, Y. V., Burkov, A. T. & Pshenay‐Severin, D. A. Thermoelectric properties of topological insulators. Phys. Status Solidi B 255, 1800020 (2018).

Goyal, V., Teweldebrhan, D. & Balandin, A. A. Mechanically-exfoliated stacks of thin films of Bi2Te3 topological insulators with enhanced thermoelectric performance. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 133117 (2010).

Ghaemi, P., Mong, R. S. & Moore, J. E. In-plane transport and enhanced thermoelectric performance in thin films of the topological insulators Bi2Te3 and Bi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 166603 (2010).

Liang, J., Cheng, L., Zhang, J., Liu, H. & Zhang, Z. Maximizing the thermoelectric performance of topological insulator Bi2Te3 films in the few-quintuple layer regime. Nanoscale 8, 8855–8862 (2016).

Heremans, J. P., Cava, R. J. & Samarth, N. Tetradymites as thermoelectrics and topological insulators. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17049 (2017).

Hinsche, N. F. et al. Impact of the topological surface state on the thermoelectric transport in Sb2Te3 thin films. ACS Nano 9, 4406–4411 (2015).

Zastrow, S. et al. Thermoelectric transport and Hall measurements of low defect Sb2Te3 thin films grown by atomic layer deposition. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 28, 035010 (2013).

Wang, X. Y. et al. Thermoelectric performance of Sb2Te3-based alloys is improved by introducing PN junctions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 10, 23277–23284 (2018).

Hor, Y. S. et al. p-type Bi2Se3 for topological insulator and low-temperature thermoelectric applications. Phys. Rev. B 79, 195208 (2009).

Sun, G. L. et al. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of nanostructured topological insulator Bi2Se3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 053102 (2015).

Ishida, A. et al. Electrical and thermoelectrical properties of SnTe-based films and superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 122106 (2009).

Yarmohammadi, M. & Mirabbaszadeh, K. Enhancement of the anisotropic thermoelectric power factor of topological crystalline insulator SnTe and related alloys via external perturbations. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 25573–25585 (2019).

Xu, S. Y. et al. Observation of a topological crystalline insulator phase and topological phase transition in Pb1-xSnxTe. Nat. Commun. 3, 1192 (2012).

Dong, B. et al. New two-dimensional phase of tin chalcogenides: Candidates for high-performance thermoelectric materials. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 013405 (2019).

Cho, S. et al. Thermoelectric imaging of structural disorder in epitaxial graphene. Nat. Mater. 12, 913–918 (2013).

Lee, E.-S., Cho, S., Lyeo, H.-K. & Kim, Y.-H. Seebeck effect at the atomic scale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 136601 (2014).

Zhao, M. et al. Coherent thermoelectric power from graphene quantum dots. Nano Lett. 19, 61–68 (2019).

Kim, D. et al. Atomic-scale thermopower in charge density wave states. Nat. Commun. 13, 4516 (2022).

Kim, K. et al. van der Waals heterostructures with high accuracy rotational alignment. Nano Lett. 16, 1989–1995 (2016).

de Jong, T. A. et al. Imaging moire deformation and dynamics in twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Commun. 13, 70 (2022).

Nam, N. N. T. & Koshino, M. Lattice relaxation and energy band modulation in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 96, 075311 (2017).

Wong, D. et al. Cascade of electronic transitions in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 582, 198–202 (2020).

Nuckolls, K. P. et al. Strongly correlated Chern insulators in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 588, 610–615 (2020).

Nuckolls, K. P. & Yazdani, A. A microscopic perspective on moiré materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 460–480 (2024).

Kim, D. et al. Phase engineering of 2D materials. Chem. Rev. 123, 11230–11268 (2023).

Zhang, F., MacDonald, A. H. & Mele, E. J. Valley Chern numbers and boundary modes in gapped bilayer graphene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 10546–10551 (2013).

He, D. et al. Two-dimensional quasi-freestanding molecular crystals for high-performance organic field-effect transistors. Nat. Commun. 5, 5162 (2014).

Ni, J. et al. Lithography-free and high-efficiency preparation of black phosphorous devices by direct evaporation through shadow mask. Nanotechnology 33, 225201 (2022).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Caldeweyher, E. et al. A generally applicable atomic-charge dependent London dispersion correction. J. Chem. Phys. 150, 154122 (2019).

Pizzi, G. et al. Wannier90 as a community code: new features and applications. J. Phys. Cond. Matt. 32, 165902 (2020).

Kawamura, M., Gohda, Y. & Tsuneyuki, S. Improved tetrahedron method for the Brillouin-zone integration applicable to response functions. Phys. Rev. B 89, 094515 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Samsung Research Funding & Incubation Center of Samsung Electronics under project no. SRFC-MA1701-52, the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) under Grant No. RS-2024-00340377, RS-2023-00256050, and NRF-2021M3H4A1A03054856. D.K. was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2023-00243160). Y.-H.K., J.S., and S.B. were supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (2019M3D1A1078302) and the Grand Challenge 30 program from the College of Natural Sciences, KAIST. M.Z. was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12204351).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.-H.K., M.Z., and H.Y. conceived and directed the project. D.K. and J.S. designed the model. S.Y., W.C., and S.Z. fabricated the samples and conducted the experiments. J.S., S.B., and Y.-H.K. conducted the theoretical analysis. D.K., J.S., Y.-H.K., and H.Y. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, D., Seo, J., Yer, S. et al. Thermal biasing for lattice symmetry breaking and topological edge state imaging. Nat Commun 16, 1879 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57194-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57194-x

This article is cited by

-

Van der Waals materials for energy-efficient electronic devices

Nature Reviews Materials (2026)