Abstract

Enhancing selectivity towards specific products remains a pivotal challenge in energy catalysis. Herein, we present a strategy to refine selectivity via pathway optimization, exemplified by the rational design of catalysts for methanol steam reforming. Over traditional Pd/ZnO catalysts, the direct decomposition of key intermediates CH2O* into CO and H2 on PdZn alloys competes with the oxidation of CH2O* to CO2, leading to inferior selectivity in product distribution. To address this challenge, Cu is introduced to modify the catalytic dynamics, lowering the dissociation energy barrier of water to provide more active hydroxyl groups for the oxidation of CH2O*. Simultaneously, the CO desorption energy barrier on PdCu alloys is elevated, thereby hindering CH2O* decomposition. This dual functionality enhances both the selectivity and activity of the methanol steam reforming reaction. By modulating the activation patterns of key intermediate species, this approach provides new insights into catalyst design for improved reaction selectivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since Jöns Jakob Berzelius first introduced the concept of catalysis, this field has largely overlooked the aspect of selectivity due to the relatively straightforward nature of the involved reactions, which typically yields few byproducts1. However, the ability to direct reactions towards specific outcomes has become paramount as modern energy catalysis systems have grown with increasing complexity2. Designing catalysts capable of controlling the product distribution to enhance selectivity has thus emerged as a key focus3. This precision not only minimizes energy consumption but also reduces economic losses associated with product separation and purification1,4. Nevertheless, the essence of adjusting selectivity lies in manipulating the activation energy barriers of competing pathways at the kinetic level5, which requires a nuanced approach for the modification of the surface structures and electronic properties of the catalysts from first principles to favour the desired reaction intermediates and pathways. While highly challenging, tuning a catalyst’s selectivity not only depends on the alteration of its physical properties but also involves a deep dive into the mechanistic intricacies of the reactions.

The pervasive presence of water in virtually all industrially relevant gaseous catalytic reactions has necessitated a thorough examination of its complex and multifaceted role in influencing the reaction pathway, especially where water is considered an active participant in the reaction. The importance of relevant research is exemplified in a variety of catalytic processes, such as the water-gas shift reaction (WGS)6, hydrogen evolution reaction (HER)7, electrocatalytic nitrate reduction reaction8, and steam reforming reaction9,10. The above reactions are characterized by the adsorption and activation of water molecules on catalyst surfaces, with the dissociation step being critically important11. Consequently, achieving an atomic-level understanding of the water dissociation process and the ability to precisely control it have merged as key objectives12,13. Strategies employed include enhancing strong metal-support interactions (SMSI)14,15, improving electronic metal-support interactions (EMSI)14,15, leveraging size effects16, and alloying7. Additionally, the binding strength of intermediate species has a direct impact on the distribution profile of the products, thus playing a role just as crucial as the adsorption and activation of the reactants in the chemical kinetics of gas‒solid catalytic reactions. In this scenario, surface engineering to inhibit the desorption of key intermediate species as byproducts to support their participation in subsequent reaction networks has emerged as a straightforward and smart strategy for tuning the selectivity of catalytic reactions involving tandem mechanisms17,18,19.

The effectiveness of modifying the activation dynamics of the key intermediates and the adsorption strength of byproducts, with an aim to improve selectivity, is best illustrated by the application of this approach to modify the reaction pathway for producing hydrogen (H2) from methanol and water. Amid escalating environmental and energy challenges, methanol steam reforming (MSR) has gained prominence as an efficient clean energy technology and a reliable source of CO-depleted H2 for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs)20. During the MSR reaction, methanol undergoes sequential dehydrogenation to form formaldehyde (CH2O*). Investigations21,22 have pinpointed CH2O* as a critical intermediate in MSR, and its decomposition is a primary route for CO production, with the resulting CO further participating in the water-gas shift (WGS) reaction to form CO2 and H2. Alternatively, CH2O* can be oxidized by the hydroxyl group (OH*) from water dissociation to formate (HCOO*), which then breaks down into CO2 and H2. The balance between the direct decomposition and the oxidation of CH2O* is key to modulating the CO/CO2 selectivity, which is influenced by the strength of CO adsorption23, and the reaction energy difference between the above-mentioned reaction pathways and WGS process24. In this context, palladium-based catalysts emerge as promising candidates because the formation of PdZn alloys has shown the ability to weaken the Pd–CO bond23,25 and accelerate the activation of water to promote the conversion of methanol26,27. However, the effectiveness of these structures in reducing CO production remains a subject of debate21,28. Their weak interaction with CO also raises concerns regarding the effectiveness of tuning the selectivity, highlighting a need for ongoing research and optimization. In comparison, conventional copper-based catalysts, such as Cu/ZnO, rely on strong electronic interactions between Cu1+ species and ZnOx, which facilitate the formation of CuZn alloy‒ZnO active sites. These unique active sites play a crucial role in promoting essential reaction steps, including water dissociation and the dehydrogenation of methoxy (CH3O*), thereby significantly enhancing the MSR reaction efficiency26,29. This underscores the dominant role of Cu in the MSR process and points to the potential of bimetallic PdCu alloys. Such alloys could synergistically combine the benefits of Pd and Cu, optimizing the adsorption and activation of MSR reaction intermediates and further enhancing overall reaction performance.

Expanding upon this framework, our objective is to refine the MSR reaction pathways to minimize gaseous CO formation by modifying the activation dynamics of key intermediates and the adsorption strength of byproducts. As a demonstration, Cu is introduced to modify the alloy composition of Pd/ZnO catalysts. Detailed characterizations confirm the preferential formation of PdCu alloys over conventional PdZn alloys, resulting in significantly stronger adsorption of CO and an enhanced capability for activated water dissociation. Consequently, the reaction mechanism shifts from CH2O* decomposition to CH2O* oxidation over Cu-doped Pd/ZnO. As expected, the PdCu1/ZnO sample (with an optimal ratio of 1 wt% Pd and 1 wt% Cu) shows superior catalytic performance, with a 2.3-fold increase in catalytic activity at 200 °C and a 75% decrease in CO selectivity compared to those of the undoped Pd/ZnO catalyst. DFT calculations further elucidate the tuning of the reaction energy diagram over the PdCu alloy catalysts, favouring the selective production of CO2 and H2 over the unintended formation of CO. This strategic approach to designing catalysts with enhanced selectivity highlights a promising direction for future catalysis research.

Results

Structural characterizations

A series of PdCux/ZnO catalysts (subscripts x denotes the Cu content by weight percentage) were synthesized by incipient wetness impregnation and reduced in a 10%-H2/N2 mixture (100 mL min−1) at 300 °C for 2 h prior to use. For benchmarking purposes, a Cu/ZnO catalyst with a 1 wt% copper loading was also prepared using an identical procedure. Inductively coupled plasma‒optical emission spectrometry (ICP‒OES) analysis confirmed that the actual metal loading closely matched the designed values (Supplementary Table 1). The Brunauer‒Emmett‒Teller (BET) surface areas of the samples loaded with Pd and/or Cu only exhibited a slight decrease compared to those of the pure ZnO support (Supplementary Table 1).

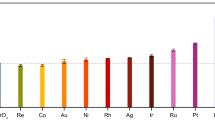

The characteristic peaks of ZnO were observed in the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of all samples (Supplementary Fig. 1). Detailed scanning in the 40°–45° range revealed the formation of alloys with distinct features (Fig. 1a). Specifically, Pd/ZnO exhibited a subtle broad peak at 41.4°, indicating the formation of PdZn alloys21,30,31. Moreover, for the Cu-incorporated Pd/ZnO catalysts, diffraction peaks were observed between 42.7° and 42.8°, indicating the formation of PdCu alloys32,33,34. In addition, CuZn alloys with a diffraction peak at 43.4° were detected for the Cu/ZnO catalyst35. Based on these data, the introduction of Cu facilitated the preferential formation of the PdCu alloys over PdCu/ZnO catalysts. The synthesis of these diverse alloys was further corroborated by high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping, which highlighted the (111) and (200) crystal planes of the PdZn alloys in the Pd/ZnO sample, with an average size of 3.5 nm (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2a). In contrast, the PdCu alloys were identified on the PdCu1/ZnO catalyst through element line-scan analysis, with an average size of 5.9 nm (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 2b), compared to 4.3 nm for PdCu0.5/ZnO and 6.0 nm for PdCu2/ZnO (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4).

X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) measurements play a crucial role in revealing the hyperfine structure of catalysts at the atomic scale36. The Pd K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra showed that the white line peaks of Pd/ZnO and PdCu1/ZnO differed from those of PdO but were well aligned with those of metallic Pd (Fig. 2a)37,38. Similarly, the Cu K-edge XANES data indicated that the Cu atoms in both the Cu/ZnO and PdCu1/ZnO samples predominantly existed in a metallic state (Supplementary Fig. 5)36. Further insights were gained from the Pd K-edge Fourier transform-extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT‒EXAFS) spectra in the R space; here, the first shell distance in Pd/ZnO (~2.50 Å) was slightly shorter than that in Pd foil (~2.54 Å), and this result is consistent with the formation of PdZn alloys (Fig. 2b). This deduction was reinforced by wavelet transform (WT) spectroscopy at the Pd K-edge, where the characteristic peak for Pd/ZnO (8.0 Å−1, 2.5 Å) differed in k value from that of Pd foil (8.7 Å−1, 2.5 Å) with the overlap of the Pd‒Zn scattering (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b)39. A similar variation in the k value was also observed for PdCu1/ZnO in WT spectroscopy at the Cu K-edge (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 6c); here, the maximum shifted to a higher k value (8.6 Å−1, 2.3 Å) compared with that of Cu foil (8.0 Å−1, 2.2 Å), and this result indicated the presence of Pd‒Cu scattering. Additionally, the first shell Pd–Pd bond distance for PdCu1/ZnO (~2.48 Å) was shorter than that in Pd foil (~2.54 Å) (Fig. 2b), while, the Cu–Cu bond length (2.34 Å), was longer than that of Cu foil (~2.24 Å) (Supplementary Fig. 7). These results collectively confirm the formation of PdCu alloys on PdCu1/ZnO.

Quasi-in situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (Quasi-in situ XPS) analysis provided further insight into the electronic states of Pd and Cu atoms in the alloy catalysts (Fig. 2d, e). The Pd species were confirmed to exist in their metallic state (Pd0), with binding energy values at 335.0 eV and 340.3 eV40,41, consistent with the XANES results. Furthermore, the Pd0 binding energies in the PdCux/ZnO catalysts exhibited a negative shift relative to the values reported for metallic Pd (335.6 eV and 340.9 eV)40,41. This shift can be attributed to electron transfer from Cu or Zn to Pd, driven by the higher electronegativity of Pd (2.20) compared to Cu (1.90) and Zn (1.65), resulting in electronic structure modifications in the PdCu and PdZn alloy catalysts. For Cu species, peaks at 932.6 eV and 952.4 eV corresponded to Cu0/Cu1+ (Fig. 2e)42,43. In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy of CO adsorption (in situ CO-DRIFTS) further confirmed the co-existence of Cu0 and Cuδ+ (0 < δ < 2) in the Cu-containing samples (Supplementary Fig. 8)9,44. Importantly, the proportion of Cu0 in PdCu/ZnO samples was significantly lower than in Cu/ZnO, suggesting altered electronic properties and interactions due to alloy formation. The temperature-programmed reduction with hydrogen (H2-TPR) profiles revealed a distinct reduction peak for PdCu1/ZnO, whereas, for Pd/ZnO and Cu/ZnO, a broad peak that could be decomposed into two components was observed (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Note 1, and Supplementary Table 2). This pattern indicated the absence of phase separation between the Pd and Cu species in the PdCu alloys, even following the oxidation treatment of PdCu1/ZnO prior to TPR analysis33. This conclusion was corroborated by HADDF-STEM and EDS analyses of O2-treated PdCu1/ZnO samples, which also confirmed the retention of phase homogeneity even after oxidation (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Reaction mechanism

The structural integrity of the alloy phase under reaction conditions is crucial for elucidating the reaction mechanism. As shown in Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 10, in situ X-ray diffraction (in situ XRD) analysis confirmed that the PdCu alloy phase in the PdCu1/ZnO sample remained stable under a CH3OH + H2O (500/1000 ppm) atmosphere at 250 °C. Similarly, under the MSR conditions, in situ Raman spectroscopy revealed the stability of both PdZn and PdCu alloys. Notably, no Pd-O bond vibration peak at 639 cm−1 was observed45,46, further affirming the absence of Pd oxidation under reaction conditions (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12). Furthermore, the near-surface valence states of metals in the PdCu1/ZnO catalyst were examined using near-ambient pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (NAP-XPS) under H2O or CH3OH atmospheres at 300 °C (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. 13). Under humid conditions, the binding energy of Pd species in PdCu1/ZnO increased by 0.2 eV compared to those under H2 or CH3OH atmospheres (Fig. 3b). Simultaneously, the binding energy of Cu species increased by 0.4–0.5 eV (Fig. 3c). These changes in binding energy are ascribed to the activation of water molecules on the surface of PdCu alloys. Electron transfer from Pd and Cu species to H2O resulted in the formation of partially oxidized species, Pdδ+ and Cuδ+ (0 < δ < 2).

a In situ XRD patterns of the PdCu1/ZnO catalyst exposed to H2 (350 °C) and CH3OH + H2O (250 °C). NAP-XPS b Pd 3d and c Cu 2p spectra of the PdCu1/ZnO catalyst exposed to H2, H2O, and CH3OH at 300 °C. In situ Raman spectra of d Pd/ZnO and e PdCu1/ZnO during activation with 3.2% H2O balanced with N2 at different temperatures; f temporal change in the Raman peak area (639 cm−1). In situ DRIFTS-MS of g Pd/ZnO and h PdCu1/ZnO with increasing temperature from 50 °C to 300 °C at a ramping rate of 3 °C min−1 in CH3OH + H2O + N2. i Peak area of HCOO* (2867 cm−1) in (g, h) and H2 MS signal during the in situ DRIFTS experiments.

The adsorption strength of the byproduct CO plays a crucial role in the product selectivity of the MSR reaction47, which was investigated through temperature-programmed desorption of carbon monoxide (CO-TPD) experiments (Supplementary Fig. 14). The desorption temperature of CO from PdCu alloys over PdCu1/ZnO (11 °C) was significantly greater than that of the CO desorption from Pd/ZnO at 4 °C and from Cu/ZnO at 8 °C. These results indicated that the binding strength of CO on the PdCu alloys was relatively strong.

On the other hand, the dissociation of water was crucial in the MSR process since the OH* generated actively participated in the transformation of CH2O* to HCOO*9. Next, in situ Raman spectroscopy was employed to assess the water dissociation capabilities of the Pd/ZnO and PdCu1/ZnO catalysts (Fig. 3d, e). The initial Raman spectrum of Pd/ZnO at 25 °C exhibited four peaks (Fig. 3d). The three peaks at 325 cm−1, 431 cm−1, and 573 cm−1 were assigned to different optical modes of ZnO48,49, while the faint peak at 639 cm−1 was attributed to the vibrational mode of Pd-O bond45,46, likely formed due to the partial oxidation of Pd in air. Upon the introduction of water, this Pd-O peak significantly increased and was further intensified with increasing temperature; these results indicated that water could act as an oxidant to transform the metallic Pd to PdOx (0 < x < 1). The same experiment was carried out on PdCu1/ZnO (Fig. 3e), where a notably stronger Pd-O peak was observed compared to that of Pd/ZnO at the same temperature (Fig. 3f). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 15, formation of PdOx was accompanied by the appearance of OH* (3651 cm−1, 3672 cm−1, 3708 cm−1, and 3744 cm−1)42,50,51, corroborating the occurrence of the effective water dissociation. Apparently, the formation of PdCu alloys enhanced the water dissociation ability, which could facilitate the conversion of CH2O* to HCOO*. The enhanced redox capabilities of the PdCu1/ZnO catalyst were subsequently confirmed through temperature-programmed oxidation with oxygen (O2-TPO) experiments, which showed lower oxidation temperatures of the metal species than those in Pd/ZnO (Supplementary Fig. 16).

To assess how the addition of Cu modifies the reaction pathways in MSR, in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy-mass spectrometry (in situ DRIFTS-MS) studies were first conducted to elucidate the reaction mechanism over Pd/ZnO. As depicted in Fig. 3g and Supplementary Table 3, the surface methoxy species (CH3O*; 2814 cm−1 and 2931 cm−1)18 resulting from methanol dehydrogenation were observed when the Pd/ZnO catalyst was exposed to a CH3OH/H2O/N2 mixture at 50 °C. As the temperature increased to 300 °C, the intensity of the CH3O* peak decreased due to conversion depletion and temperature-dependent desorption and then eventually began to increase again due to increased generation rates of CH3O* at high temperatures. Moreover, the formation of the formate species (HCOO*)18 and CO was confirmed by the appearance of peaks at 2867 cm−1 and 2202 cm−1 42 on the Pd/ZnO catalyst at 50 °C and 110 °C, respectively. By integrating the area of the peak at 2867 cm−1, the temporal change in HCOO* closely followed the trend of the H2 MS signal (Fig. 3i), with both HCOO* and H2 starting to increase at 170 °C. These results indicated that HCOO* acted as a crucial intermediate in the generation of H2 via the MSR reaction on Pd/ZnO. However, the evolution of the HCOO* peak area did not mirror the behaviour of the gaseous CO product, indicating the existence of two distinct transformation pathways for CH3O* on the Pd/ZnO catalyst: one leading to HCOO* and subsequently to H2 and the other possibly leading directly to CO.

During the MSR process on the PdCu1/ZnO catalyst, the formation of CH3O* species and HCOO* were evident (Fig. 3h). Notably, the peak intensity of the HCOO* species (2867 cm−1) significantly increased at 140 °C and increased with increasing temperature. This increase in the HCOO* signal strength on PdCu1/ZnO correlated with a substantial increase in H2 production at 140 °C (Fig. 3i), revealing the pivotal role of HCOO* as the key intermediate for H2 production during the MSR reaction. Notably, gaseous CO was absent on the PdCu1/ZnO catalyst throughout this process. Furthermore, in situ DRIFTS-MS analysis revealed a more pronounced presence of HCOO* than on Pd/ZnO, accompanied by a higher yield of H2 and negligible formation of gaseous CO. This observation was in alignment with the anticipated performance of PdCu1/ZnO from the above CO-TPD and in situ Raman experiment results. The significant contribution of HCOO* to H2 production was also corroborated by in situ DRIFTS-MS measurements conducted over ZnO and Cu/ZnO (Supplementary Figs. 17 and 18 and Supplementary Note 2).

Despite the common challenge of detecting the intermediate formaldehyde species (CH2O*) in MSR via in situ DRIFTS, the IR signature of dioxymethylene species (CH2OO(H)*, arising from the reaction between CH2O* and OH*52,53) was identified at 2912 cm−1 for the ZnO, Cu/ZnO, and Pd/ZnO samples. Conversely, this species was absent over the reactive sample, PdCu1/ZnO, indicating the promoted activity of CH2OO(H)* over PdCu alloys (Supplementary Figs. 17–19 and Fig. 3g, h). Based on these findings, two primary reaction pathways were elucidated from in situ DRIFTS-MS experiments: (1) CH3OH → CH3O* → CH2O* → CH2OO(H)* → HCOO* → CO2 + H2 (the main pathway) and (2) CH3OH → CH3O* → CH2O* → CO + H2 (a secondary pathway). The summary of MSR reaction pathways derived from in situ DRIFTS-MS serves as a foundational framework for guiding subsequent density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The two pathways compete with each other on the Pd/ZnO catalyst. In contrast, the formation of PdCu alloys altered this dynamic, steering the PdCu1/ZnO catalyst to favour the principal reaction pathway, thereby revealing a marked shift in the reaction mechanism attributed to synergistic effects within the bimetallic alloy system.

Catalytic performance

To corroborate the catalytic efficiency predicted by the preceding mechanistic studies, the performances of the PdCux/ZnO catalysts in the MSR reaction were evaluated from 175 °C to 300 °C. At 275 °C, both the Pd/ZnO and PdCu1/ZnO catalysts exhibited notable catalytic activity for MSR, achieving a methanol conversion of approximately 90% (Supplementary Fig. 20). However, at temperatures below 275 °C, the introduction of Cu notably enhanced the activity of Pd/ZnO. Specifically, at 200 °C, the methanol conversion over PdCu1/ZnO was 18.7%, representing a 2.3-fold increase over Pd/ZnO (Fig. 4a). This enhancement by the incorporation of Cu was more pronounced in terms of the space-time yield (STY) of H2 (Supplementary Fig. 21). Among the catalysts evaluated, PdCu1/ZnO showed the highest STY of H2 (10.1 μmol gcat−1 s−1 at 200 °C), and this value was 2.3 and 7.2 times greater than those of Pd/ZnO and Cu/ZnO, respectively (Fig. 4b). As expected, the CO selectivity of the PdCu/ZnO catalysts was drastically lower than that of Pd/ZnO (Supplementary Fig. 22). For instance, at 200 °C, the CO selectivity of Pd/ZnO was 50.2%, while that of PdCu1/ZnO plummeted to 12.6% (Fig. 4a). The excellent catalytic performance of the PdCu/ZnO catalysts in the MSR process aligned with the deductions from the CO-TPD, in situ Raman, and in situ DRIFTS experiments. When benchmarked against previously reported catalysts (Supplementary Table 4), PdCu1/ZnO demonstrated competitive catalytic activity for MSR, although stability improvements remain necessary (Supplementary Fig. 23). Essentially, the formation of PdCu alloys facilitated the primary reaction pathway conducive to hydrogen production and effectively suppressed the secondary reaction pathway that led to CO formation. Kinetic tests conducted under controlled conditions further validated this behaviour. The apparent activation energies (Ea), derived using the Arrhenius equation (Supplementary Fig. 24), revealed that Pd/ZnO exhibited the highest Ea (79 kJ mol−1), while the incorporation of Cu significantly reduced the activation energy, affirming the enhanced MSR activity of PdCu alloys over PdZn alloys.

In the context of the MSR process, methanol decomposition (MD) and water-gas shift (WGS) reactions are pivotal sub-reactions for CO generation and its subsequent consumption24, respectively. To explore the roles of these reactions in influencing CO dynamics, comparative studies were conducted on the catalytic activities of Cu/ZnO, Pd/ZnO, and PdCu1/ZnO for both the MD and WGS processes. During the MD reaction (Supplementary Fig. 25), from 200 °C to 325 °C, the CO yield from Pd/ZnO significantly exceeded that from PdCu1/ZnO. This disparity indicated a greater propensity of Pd/ZnO for facilitating the decomposition of methanol into CO. Conversely, Cu/ZnO consistently demonstrated low CO yields at temperatures below 250 °C, indicating that Cu species effectively suppress methanol decomposition. These findings explain the significantly reduced CO selectivity observed for PdCu/ZnO catalysts at temperatures below 250 °C (Supplementary Fig. 22). Conversely, when examining the WGS reaction (Supplementary Fig. 26a, b), all catalysts demonstrated comparable CO conversion and similar yields of H2 and CO2, confirming the equivalent efficacy of Cu/ZnO, Pd/ZnO, and PdCu1/ZnO in catalysing the WGS reaction. Based on these findings, the diminished CO selectivity observed with PdCu1/ZnO could be primarily attributed to the suppression of the CO generation during the initial methanol decomposition phase rather than an enhanced consumption of CO in the latter water-gas shift stage.

Theoretical considerations of the reaction mechanism

Based on the intermediates detected through in situ DRIFTS9,22, density functional theory calculations were utilized to elucidate the energy barriers of crucial reaction steps within the MSR reaction (both the main and side pathways) on PdZn (111) and PdCu (111) (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Table 5); these represented the two active surfaces of Pd/ZnO and PdCu1/ZnO, respectively (Fig. 5a, b, Supplementary Figs. 27–30, and Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). The reaction energy diagrams for the main pathway are presented in Fig. 5a, highlighting the dehydrogenation of CH3OH*, the subsequent dehydrogenation of CH3O* to CH2O*, the dissociation of adsorbed water, and the dehydrogenation of HCOO* as key reaction steps with relatively high energy barriers. Besides the above three steps, the energy barrier for the dissociation of H2O* into OH* and H* via TS-4 was exceptionally high, which was 1.00 eV for PdZn (111) and reduced to 0.93 eV for PdCu (111), indicating that PdCu alloys possessed an enhanced capability for water dissociation; this result corroborated the in situ Raman results. Furthermore, on the PdCu alloy surfaces, the activation barriers for the dehydrogenation of CH3OH* to CH3O* via TS-1, CH3O* to CH2O* via TS-2, and HCOO* to CO2* via TS-9 were significantly lower (0.56 eV, 0.59 eV, and 0.53 eV, respectively) than those on the PdZn alloys (0.92 eV, 0.79 eV, and 1.01 eV, respectively). This reduction in activation barriers highlighted the propensity of the PdCu1/ZnO catalyst to facilitate the primary MSR pathway, contributing to its heightened activity.

DFT-calculated Gibbs free energy profiles of the PdZn (111) and PdCu (111) alloys for the a main pathway and b side pathway of the MSR reaction. The Gibbs free energy values were calculated using a temperature of 200 °C. The asterisk indicates the adsorption state, and ‘TS’ denotes the transition state. The reaction snapshots are shown with Pd, Cu, C, H, and O in green, orange, grey, white, and red, respectively.

The side reaction pathway predominantly involves the stepwise dehydrogenation of CH2O* and is a process generally acknowledged in previous studies as crucial for CO generation21,54; this pathway was also examined (Fig. 5b). Remarkably, on PdCu (111), the energy barrier for converting CO* to gaseous CO was calculated to be substantially greater at 0.83 eV than at 0.21 eV on PdZn (111). This significant increase in the desorption energy barrier for CO* on PdCu alloys indicated effective suppression of gaseous CO production on the PdCu1/ZnO catalyst; this result was in agreement with observations from the CO-TPD experiments. This series of DFT analyses provided a molecular-scale understanding of the catalytic superiority of PdCu alloys in the MSR process, emphasizing their role in promoting the main reaction pathway while simultaneously mitigating side-reaction CO generation.

To elucidate the relationship between the electronic structure of the catalysts and their CO selectivity, the d-band centres (εd) of PdCu and PdZn on the surface of the catalysts were determined through analysis of their d-orbital projected density of states (PDOS) (Supplementary Figs. 31–33, Supplementary Note 4, and Supplementary Table 8). Evidently, the εd value for PdCu in the PdCu1/ZnO catalyst (−1.52 eV) was found to be closer to the Fermi level than that of PdZn in the Pd/ZnO catalyst (−4.26 eV). This observation indicated that the PdCu alloys exhibited a higher binding strength for CO, which was consistent with the higher CO desorption energy barrier over the PdCu alloy surfaces.

Integrating insights from the in situ DRIFTS experiments and DFT calculations, the reaction pathways operating over PdZn (111) and PdCu (111) alloys are delineated in Fig. 6a, b. During the MSR reaction, the PdCu alloys reduced the energy barrier for water dissociation, thereby promoting the primary reaction pathway while simultaneously increasing the energy barrier for the desorption of CO*; this effectively suppressed the secondary reaction pathway. This dual effect of the PdCu alloys demonstrated their significant role in dictating the overall reaction dynamics and product selectivity in the MSR processes.

Optimizing product selectivity within complex chemical reactions represents a formidable yet difficult challenge in catalysis. We introduce a strategy aimed at refining the reaction pathways to tune the selectivity of a catalyst, primarily through the modification of the bimetallic alloy components. In catalytic reactions with well-established mechanisms, key steps that influence reaction kinetics can be identified, such as the competing oxidation of CH2O* and its decomposition in MSR. By adjusting the bimetallic alloy composition, the activation patterns of this key intermediate can be modulated, thereby influencing the selectivity towards the desired products. Specifically, PdCux/ZnO alloy catalysts were meticulously engineered and subsequently employed in the process of methanol steam reforming for H2 production.

The initial step in our investigation involved the utilization of established analytical techniques, such as in situ XRD, HAADF-STEM, XAFS, and quasi-in situ XPS, to verify the formation of the stable alloy structures on the Pd/ZnO and PdCu/ZnO catalysts. These characterizations collectively confirmed the presence of the PdCu alloys in the PdCu/ZnO catalysts, which contrasted with the PdZn alloys identified in the Pd/ZnO catalyst. Additionally, H2-TPR experiments indicated the excellent stability of the PdCu alloy structure with high resistance to phase separation by oxidation. Subsequent CO-TPD experiments provided evidence of the weakened desorption of CO* as a gaseous product on the PdCu alloys compared to the original PdZn alloys on undoped Pd/ZnO. Moreover, NAP-XPS and in situ Raman spectroscopy revealed that water acted as an oxidant to facilitate the oxidation of metallic Pd, resulting in the formation of OH* and H*. This OH* generation process was notably accentuated in the PdCu alloy systems.

The mechanism of H2 production via MSR across different alloy catalysts was investigated by in situ DRIFTS, which identified two distinct reaction pathways as reported21,22. In both scenarios, CH3OH first underwent successive dehydrogenation steps to yield CH3O* and subsequently CH2O* species. The following reaction steps significantly varied and were influenced by the underlying alloy structures. Within the primary pathway, CH2O* reacted with OH* species from active water dissociation to form HCOO*; upon decomposition, HCOO* yielded CO2 and H2. Conversely, the side pathway involved the direct decomposition of CH2O* to generate CO and H2. Consequently, the refinement of selectivity in the MSR reaction depended on the adjustment of the reaction energies to preferentially promote water dissociation, thereby readily supplying OH* species for the conversion of CH2O* to HCOO* via the main pathway. Simultaneously, an alternative strategy involved the suppression of byproduct CO release from the alloy surface, effectively restricting the side reaction pathway. This dual approach aims to channel the reaction towards the desired production of hydrogen and CO2 while minimizing the formation of undesired CO.

From the characterizations, both the inhibition of CO* desorption and the enhancement of water dissociation were achieved on the PdCu alloys formed through the incorporation of Cu into the Pd/ZnO catalysts. These modifications led to a marked preference for the continued oxidation of the key intermediate CH2O* over its direct decomposition into CO on the PdCu1/ZnO catalyst. Specifically, this catalyst exhibited a 2.3-fold increase in activity and a 75% reduction in CO selectivity at 200 °C compared to those of the conventional Pd/ZnO catalyst. Finally, further validation through theoretical calculations, including DFT and PDOS, corroborated these findings. In comparison to the PdZn alloys, the PdCu alloys displayed a decreased energy barrier for water dissociation and an increased energy barrier for CO* desorption. As a result, the PdCu alloys demonstrated an enhanced ability to dissociate water, thereby facilitating the production of OH*, which actively participated in the transformation of CH2O* to HCOO*. Additionally, the enhanced desorption energy barrier for CO* on the PdCu alloys contributed to the suppression of gaseous CO formation, effectively decreasing CO selectivity. These insights clearly help determine the structure-property relationship, highlighting the strategic role of adjusting the alloy composition in optimizing the catalytic performance and selectivity of the MSR reaction. As research progresses, catalyst design is evolving from traditional methods that focus primarily on tweaking preparation parameters to new approaches that draw insights from delving into the reaction mechanisms within well-established pathways. Re-examining and interpreting ‘old’ data through this new lens provides new opportunities to enhance catalytic performance. This shift emphasizes a more informed construction of catalysts, promising improvements in efficiency and effectiveness based on a solid foundation of mechanistic insights.

Discussion

In summary, in situ characterization studies confirmed the established MSR reaction mechanism over conventional Pd/ZnO catalysts, beginning with the progressive dehydrogenation of CH3OH to form CH2O*. This intermediate CH2O* then interacted with the OH* species generated from water dissociation to produce HCOO*. The decomposition of the HCOO* intermediate subsequently yielded H2 and CO2. A competitive reaction pathway involving the direct decomposition of CH2O* led to the undesirable production of CO. Building on the above-mentioned, Cu was incorporated into Pd/ZnO to form stable PdCu alloys to steer the reaction kinetics towards the favourable oxidation of CH2O*; these alloys have been shown to be effective in enhancing the dissociation of water and inhibiting the desorption of CO. During the MSR reaction, the optimally engineered PdCu1/ZnO exhibited a 2.3-fold increase in the catalytic activity at 200 °C with a remarkably 75% decrease in the CO selectivity with respect to the conventional Pd/ZnO catalyst. Theoretical calculations revealed that the introduction of PdCu alloys successfully reduced the energy barrier for the key reaction steps in the main pathway, including the dissociation of water and the conversion of CH2O* to HCOO*, while simultaneously enhancing the energy barrier for the desorption of CO* as a byproduct in the side pathway. These changes significantly contributed to the enhanced activity and selectivity of the PdCu1/ZnO catalyst. The findings from this study illustrate the impact of fine-tuning the selectivity of catalytic reactions by identifying and optimizing key reaction steps, providing a case study on how to refine the catalyst structure to direct the reaction mechanism towards the desirable distribution of products.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

The following reagents were used without further purification: palladium (II) nitrate dihydrate (Pd(NO3)2·2H2O, 40% Pd basis, Sigma‒Aldrich), copper (II) nitrate trihydrate (Cu(NO3)2·3H2O, AR, 99–102%, SCR), nitric acid (HNO3, GR, 65–68%, SCR), hydrochloric acid (HCl, GR, 36-38%, SCR), absolute ethanol (C2H6O, 99.9%, Innochem), and methanol (CH3OH (MeOH), GC, ≥99.9%, Innochem). Zinc oxide (ZnO) was purchased from Liuzhou Jinlu Nanometre Material Co., Ltd.

Catalyst preparation

PdCux/ZnO (x = 0, 0.5, 1, and 2, representing the weight percent content of copper) catalysts were prepared by the incipient wetness impregnation method. First, the Pd(NO3)2·2H2O and Cu(NO3)2·3H2O precursors were weighed according to the metal loading and dissolved together in 3 mL of deionized water. Once fully dissolved, the precursor solution was added dropwise to 3 g of finely ground ZnO powder. Subsequently, the mixture was left to stand for 6 h at room temperature before being dried at 110 °C for 12 h. Finally, the dried product was calcined in a muffle furnace at 350 °C for 4 h at a heating rate of 2 °C min−1. In this series of PdCux/ZnO catalysts, the Pd content was set at 1 wt%. For comparison, a Cu/ZnO catalyst with a 1 wt% copper content was prepared by following the same procedure.

Catalytic evaluations

The methanol steam reforming (MSR) reaction measurements were conducted in a continuous plug flow fixed-bed reactor with a 5 mm inner diameter at atmospheric pressure. Before each test, 100 mg of the catalyst with a 40–60 mesh was pretreated under 10% H2/N2 (100 mL min−1) at 300 °C for 2 h. An aqueous methanol solution with a specific water/methanol molar ratio of 1.5 was injected into the heated chamber by a syringe pump (8 μL min−1, WHSV of MeOH = 2.3 h−1). Then, N2 (120 mL min−1) was introduced to carry methanol steam into the catalyst bed, and the products were analysed online by gas chromatography (GC, Agilent 8890) equipped with one TCD and two flame ionization detectors (FIDs). The methanol conversion, the carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide selectivity, and the space-time yield (STY) of H2 were calculated using the following equations:

where [X]in and [X]out (ppm) are the gas fractions of X in the inlet and outlet gases, respectively; Fout (mL min−1) is the total gas flow rate at the outlet; and Wcat (g) is the catalyst mass.

The reaction equipment and detection apparatus used for methanol decomposition (MD) and water-gas shift (WGS) were the same as those used for the MSR reaction. In the MD reaction, the reaction gas consisted of only methanol (34,000 ppm, WHSV of MeOH = 3.3 h−1) and N2 (120 mL min−1). On the other hand, in the WGS reaction, CO (5000 ppm) and evaporated H2O (33,000 ppm), balanced with N2, were used (WHSV = 74,000 mL g−1 h−1). The CO conversion of the WGS reaction was calculated using the following equation:

where [CO]in and [CO]out (ppm) are the concentrations of CO in the inlet gas and in the outlet gas, respectively.

Computational methods

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)55,56. The core and valence electrons were represented by the projector augmented wave (PAW) method with a cut-off energy of 400 eV57,58. DFT calculations were also performed with the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) as described by Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE). During the geometry optimization, forces converged below 0.05 eV Å−1, and the self-consistent field (SCF) convergence energy was 10−6 Ha. For each model, the bottom two atomic layers were fixed, while the top two atomic layers were allowed to relax. A 15 Å vacuum along the z direction was applied to prevent unexpected interactions between the periodically repeated images. Due to the large number of atoms (over 140 atoms) in the slab models, the Brillouin zone was sampled by the Monkhorst–Pack method with a 1 × 1 × 1 k-point grid. The dimer method59,60,61 combined with the climbing image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) approach62,63 was used to search for the transition states. The Gibbs free energy for each state was calculated by the following equation:

where G(T) is the Gibbs free energy at temperature T, EDFT is the DFT energy and Gcorrect(T) is the thermal correction to the Gibbs free energy. ZPE, S, and ΔU0→T are the zero-point energy, entropy, and internal energy changes induced by temperature, respectively. The Gcorrect(T) was calculated using the VASPKIT tool64.

The surface energy is calculated according to the following formula:

where Eslab and Ebulk represents the total energy of the slab and bulk model, respectively. N is the multiple of the surface model relative to the bulk model. ‘A’ represents the surface area of the slab model, and the factor of 2 in the denominator accounts for the presence of two surfaces in the slab: one at the bottom and one at the top.

More detailed experimental characterizations and reaction kinetic studies are described in the Supplementary Information.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper, supplementary information files, and source data files. All raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zaera, F. Designing sites in heterogeneous catalysis: Are we reaching selectivities competitive with those of homogeneous catalysts? Chem. Rev. 122, 8594–8757 (2022).

Nørskov, J. K., Bligaard, T., Rossmeisl, J. & Christensen, C. H. Towards the computational design of solid catalysts. Nat. Chem. 1, 37–46 (2009).

Schlögl, R. Heterogeneous catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 3465–3520 (2015).

Scott, S. L. A matter of life(time) and death. ACS Catal. 8, 8597–8599 (2018).

Zaera, F. Regio-, stereo-, and enantioselectivity in hydrocarbon conversion on metal surfaces. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 1152–1160 (2009).

Xu, M. et al. Insights into interfacial synergistic catalysis over Ni@TiO2–x catalyst toward water–gas shift reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 11241–11251 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Manipulating the water dissociation electrocatalytic sites of bimetallic nickel-based alloys for highly efficient alkaline hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202202518 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. Boosting electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to ammonia via promoting water dissociation. ACS Catal. 13, 10846–10854 (2023).

Li, D. et al. Induced activation of the commercial Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst for the steam reforming of methanol. Nat. Catal. 5, 99–108 (2022).

Meng, H. et al. A strong bimetal-support interaction in ethanol steam reforming. Nat. Commun. 14, 3189 (2023).

Guan, H. et al. Dipole coupling accelerated H2O dissociation by magnesium-based intermetallic catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202400119 (2024).

Carrasco, J. et al. In situ and theoretical studies for the dissociation of water on an active Ni/CeO2 catalyst: importance of strong metal–support interactions for the cleavage of O–H bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 3917–3921 (2015).

Hundt, P. M., Jiang, B., van Reijzen, M. E., Guo, H. & Beck, R. D. Vibrationally promoted dissociation of water on Ni(111). Science 344, 504–507 (2014).

Campbell, C. T. Catalyst-support interactions: electronic perturbations. Nat. Chem. 4, 597–598 (2012).

Xu, M. et al. Renaissance of strong metal–support interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 2290–2307 (2024).

Hu, Q. et al. Subnanometric Ru clusters with upshifted D band center improve performance for alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 13, 3958 (2022).

Kattel, S. et al. CO2 hydrogenation over oxide-supported PtCo catalysts: the role of the oxide support in determining the product selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 7968–7973 (2016).

Kattel, S., Yan, B., Yang, Y., Chen, J. G. & Liu, P. Optimizing binding energies of key intermediates for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over oxide-supported copper. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12440–12450 (2016).

Luo, W. & Asthagiri, A. Density functional theory study of methanol steam reforming on Co(0001) and Co(111) surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 15274–15285 (2014).

Steele, B. C. H. & Heinzel, A. Materials for fuel-cell technologies. Nature 414, 345–352 (2001).

Iwasa, N., Masuda, S., Ogawa, N. & Takezawa, N. Steam reforming of methanol over Pd/ZnO: effect of the formation of PdZn alloys upon the reaction. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 125, 145–157 (1995).

Meng, H. et al. Designing Cu0−Cu+ dual sites for improved C−H bond fracture towards methanol steam reforming. Nat. Commun. 14, 7980 (2023).

Halevi, B. et al. Catalytic reactivity of face centered cubic PdZnα for the steam reforming of methanol. J. Catal. 291, 44–54 (2012).

Chen, L. et al. Insights into the mechanism of methanol steam reforming tandem reaction over CeO2 supported single-site catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 12074–12081 (2021).

Hyman, M. P., Lebarbier, V. M., Wang, Y., Datye, A. K. & Vohs, J. M. A comparison of the reactivity of Pd supported on ZnO(10\(\bar{1}\)0) and ZnO(0001). J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 7251–7259 (2009).

Rameshan, C. et al. Hydrogen production by methanol steam reforming on copper boosted by zinc-assisted water activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 3002–3006 (2012).

Rameshan, C. et al. Subsurface-controlled CO2 selectivity of PdZn near-surface alloys in H2 generation by methanol steam reforming. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 3224–3227 (2010).

Jeroro, E. & Vohs, J. M. Zn modification of the reactivity of Pd(111) toward methanol and formaldehyde. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 10199–10207 (2008).

Wang, A. et al. Dissecting ZnOX/Cu interfacial self-encapsulation and methanol-induced strong metal-support interaction of the highly active alloyed CuZn and ZnO for methanol steam reforming. Fuel 357, 129840 (2024).

Liu, L. et al. ZnAl2O4 spinel-supported PdZnβ catalyst with parts per million Pd for methanol steam reforming. ACS Catal 12, 2714–2721 (2022).

Qiu, Y. et al. Construction of Pd–Zn dual sites to enhance the performance for ethanol electro-oxidation reaction. Nat. Commun. 12, 5273 (2021).

Jiang, X., Koizumi, N., Guo, X. & Song, C. Bimetallic Pd–Cu catalysts for selective CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 170-171, 173–185 (2015).

Azenha, C. S. R., Mateos-Pedrero, C., Queirós, S., Concepción, P. & Mendes, A. Innovative ZrO2-supported CuPd catalysts for the selective production of hydrogen from methanol steam reforming. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 203, 400–407 (2017).

Nie, X. et al. Mechanistic understanding of alloy effect and water promotion for Pd–Cu bimetallic catalysts in CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. ACS Catal. 8, 4873–4892 (2018).

Song, J.-M., Shen, Y.-L. & Chuang, H.-Y. Sedimentation of Cu-rich intermetallics in liquid lead-free solders. J. Mater. Res. 22, 3432–3439 (2007).

Zhao, H. et al. The role of Cu1–O3 species in single-atom Cu/ZrO2 catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation. Nat. Catal. 5, 818–831 (2022).

Pei, G. X. et al. Performance of Cu-alloyed Pd single-atom catalyst for semihydrogenation of acetylene under simulated front-end conditions. ACS Catal. 7, 1491–1500 (2017).

Guo, M. et al. Highly selective activation of C–H bond and inhibition of C–C bond cleavage by tuning strong oxidative Pd sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 11110–11120 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Anchoring Pt-doped PdO nanoparticles on γ-Al2O3 with highly dispersed La sites to create a methane oxidation catalyst. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 324, 122259 (2023).

Yang, N. et al. Synthesis of ultrathin PdCu alloy nanosheets used as a highly efficient electrocatalyst for formic acid oxidation. Adv. Mater. 29, 1700769 (2017).

Hu, T. et al. Shape-control of super-branched Pd-Cu alloys with enhanced electrocatalytic performance for ethylene glycol oxidation. Chem. Commun. 54, 13363–13366 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Exploring the ternary interactions in Cu-ZnO-ZrO2 catalysts for efficient CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Nat. Commun. 10, 1166 (2019).

Hu, B. et al. Hydrogen spillover enabled active Cu sites for methanol synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation over Pd doped CuZn catalysts. J. Catal. 359, 17–26 (2018).

Li, D. D. et al. Gallium-promoted strong metal-support interaction over a supported Cu/ZnO catalyst for methanol steam reforming. ACS Catal. 14, 9511–9520 (2024).

Baylet, A. et al. In situ Raman and in situ XRD analysis of PdO reduction and Pd0 oxidation supported on γ-Al2O3 catalyst under different atmospheres. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 4607–4613 (2011).

Wang, Y. et al. Palladium nanoparticles anchored on silanol nests of zeolite showed superior stability for methane combustion. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 356, 124221 (2024).

Hu, J. et al. Selectivity control in CO2 hydrogenation to one-carbon products. Chem 10, 1084–1117 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. In situ spectroscopic characterization and theoretical calculations identify partially reduced ZnO1-x/Cu interfaces for methanol synthesis from CO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 61, e202202330 (2022).

Šćepanović, M., Grujić-Brojčin, M., Vojisavljević, K., Bernik, S. & Srećković, T. Raman study of structural disorder in ZnO nanopowders. J. Raman Spectrosc. 41, 914–921 (2010).

Jacobs, G. & Davis, B. H. In situ DRIFTS investigation of the steam reforming of methanol over Pt/ceria. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 285, 43–49 (2005).

Ma, K. et al. Achieving efficient and robust catalytic reforming on dual-sites of Cu species. Chem. Sci. 10, 2578–2584 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. Identification of a facile pathway for dioxymethylene conversion to formate catalyzed by surface hydroxyl on TiO2-based catalyst. ACS Catal. 10, 9706–9715 (2020).

Lavalley, J.-C., Lamotte, J., Busca, G. & Lorenzelli, V. Fourier transform i.r. evidence of the formation of dioxymethylene species from formaldehyde adsorption on anatase and thoria. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 14, 1006–1007 (1985).

Lin, L. et al. Low-temperature hydrogen production from water and methanol using Pt/α-MoC catalysts. Nature 544, 80–83 (2017).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Henkelman, G. & Jónsson, H. A dimer method for finding saddle points on high dimensional potential surfaces using only first derivatives. J. Chem. Phys 111, 7010–7022 (1999).

Heyden, A., Bell, A. T. & Keil, F. J. Efficient methods for finding transition states in chemical reactions: comparison of improved dimer method and partitioned rational function optimization method. J. Chem. Phys. 123, 224101 (2005).

Kästner, J. & Sherwood, P. Superlinearly converging dimer method for transition state search. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 014106 (2008).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Henkelman, G. & Jónsson, H. Improved tangent estimate in the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths and saddle points. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9978–9985 (2000).

Wang, V., Xu, N., Liu, J.-C., Tang, G. & Geng, W.-T. VASPKIT: a user-friendly interface facilitating high-throughput computing and analysis using VASP code. Comput. Phys. Commun. 267, 108033 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Programme of China (2022YFC3704400; G.X.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22106172 and U20B6004; Z.L. and Y. Yu, respectively), and the project of eco-environmental technology for carbon neutrality (RCEES-TDZ-2021-2 and RCEES-TDZ-2021-6; Y. Yu and G.X., respectively). The authors are thankful for the support of the SSRF (Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility) during the XAFS measurements at the beamline of BL14W1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Z., G.X., Y. Yu., J.S.F., and H.H. designed the study. M.Z. carried out most of the experiments, conducted the data analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript. Z.L. performed the DFT theoretical calculations. Y.A. and Y.Z. assisted with the catalyst preparation. D.L. assisted with the catalytic evaluations. Z.L. and D.L. helped with the catalyst characterizations. Y. Yan, G.X., Y. Yu, J.S.F., and H.H. supervised the entire project and revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, M., Liu, Z., Yan, Y. et al. Optimizing selectivity via steering dominant reaction mechanisms in steam reforming of methanol for hydrogen production. Nat Commun 16, 1943 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57274-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57274-y