Abstract

Light-induced phenomena in materials can exhibit exotic behavior that extends beyond equilibrium properties, offering new avenues for understanding and controlling electronic phases. So far, non-equilibrium phenomena in solids have been predominantly explored using femtosecond laser pulses, which generate transient, ultra-fast dynamics. Here, we investigate the steady non-equilibrium regime in graphene induced by a continuous-wave (CW) mid-infrared laser. Our transport measurements reveal signatures of a long-lived Floquet phase, where a non-equilibrium electronic population is stabilized by the interplay between coherent photoexcitation and incoherent phonon cooling. The observation of non-equilibrium steady states using CW lasers stimulates further investigations of low-temperature Floquet phenomena towards Floquet engineering of steady-state phases of matter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

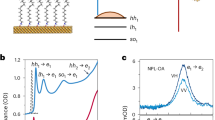

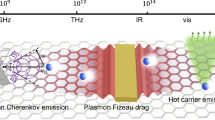

Since the inception of quantum theory, light-matter interaction has been a significant source of fascinating discoveries and innovative technologies. In the last few years, Floquet engineering, the use of light to control the properties of a material, emerged as a focus of intense research1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. This upsurge has been mainly driven by theoretical efforts4,5,10,11,12,13,14,15, with a few key experiments in the condensed matter realm, including the detection of Floquet-Bloch states through time- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy16,17,18,19, second harmonic generation20, as well as the observation of light-induced shifts of exciton resonances in WS221,22 and light-induced Hall effect in graphene20,23. These experiments predominantly explored the transient phenomena induced by ultrafast pulsed lasers, uncovering some of the physics predicted by the Floquet theory24. Other studies explored the continuous-wave (CW) regime by inducing discrete Andreev-Floquet bound states in Josephson junctions under CW microwave irradiation25,26. However, so far, solid-state experiments in the CW regime have not accessed the Floquet physics of delocalized Bloch states due to challenges related to population transfer effects and heating. In this work, we demonstrate that under intermediate intensity CW mid-infrared (mid-IR) irradiation (see Fig. 1a), the electronic population in graphene forms a non-equilibrium steady state with signatures of the underlying single-particle Floquet physics. In particular, the resulting electronic steady state relies on the Rabi-like Floquet gaps and a suppressed density of states (DOS) around electronic energies of half the photon energy \(\hslash \varOmega\) in graphene’s Floquet band structure (see Fig. 1b, c). Importantly, we demonstrate that photoinduced transport can be used as a probe of the emergent Floquet steady state in the system. Specifically, we report on signatures of these steady Floquet effects in the gate voltage dependence of the laser-induced longitudinal photoresponses of graphene samples at cryogenic temperatures ranging from 2.5 K to 50 K.

a Device layout with two contacts for longitudinal bias, VBias, and two contacts for measurements of the transverse voltage, Vy. The device has a square geometry with a 5-μm side and an indium tin oxide (ITO) top gate with an Al2O3 dielectric sublayer, for applying a gate voltage VGate. b Drive-modified Floquet bands of the graphene Dirac cone, which exhibits a Floquet gaps of size \(\Delta\) at the resonance energies \(\varepsilon=\pm \hslash \varOmega /2\), where \(\hslash\) is the reduced Planck constant and \(\Omega\) is the angular frequency of the laser. c Density of states of the Floquet bands calculated numerically for a circularly and linearly polarized laser of power density \(P=\) 3 mW/µm2. d Photo-induced change of source-drain current (\(\Delta {{\rm{I}}}\)) as a function of Fermi energy \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\) for circularly and linearly polarized laser irradiation, as measured at a constant source-drain voltage of 6 mV. \(\Delta {{\rm{I}}}\) is measured with a lock-in amplifier using a chopper modulation as a reference. The circles represent data points and the solid lines are obtained by adjacent point averaging. The dotted lines mark the \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\) values corresponding to \(\pm {{\hslash }}\varOmega /2\), with the related uncertainty indicated by the gray stripes. The uncertainty is attributed to the gate efficiency calibration and the detail is described in the Supplementary Information. The dips in \(\Delta {{\rm{I}}}\) at energies \(\pm {{\hslash }}\varOmega /2\) are much broader than the Floquet gap \(\varDelta\) (see c) and arise from the non-equilibrium steady-state distribution of electrons. The measurements were performed on sample A at a cryostat temperature of ~3.5 K, laser photon energy of 117 meV, and laser power density of 1.1 mW/µm2.

Results

Devices and photoconductive measurements

Our graphene devices were fabricated from large-area epitaxial graphene grown on SiC. The typical electron mobility of our material is about 5000 cm2/Vs for the carrier concentration range studied in this work. (Supplementary Fig. 7 shows an image of a cluster with 4 devices.) Each device was a 5 μm × 5 μm graphene square, with two source-drain contacts for the longitudinal electrical transport, two contacts to measure the transverse voltage, and a separate top gate electrode, as depicted in Fig. 1a. The top gate comprised a 90-nm-thick dielectric Al2O3 layer and a gate electrode of sputtered 110-nm-thick indium tin oxide (ITO). The properties of our epitaxial graphene, the details of the fabrication process, and the optical properties of the gate electrode are outlined in the Supplementary Information. Our laser operates with a photon energy of \(\hslash \varOmega=\,117\,{{\rm{meV}}}\), deliberately chosen to be below the optical phonon generation threshold in graphene (160-200 meV), in contrast to previous experiments that utilized photon energies above this threshold23. Importantly, this approach minimizes photo-induced phonon generation, guaranteeing acoustic phonons remain at low cryogenic temperatures and providing cooling channels for photoexcited electrons.

Overall, we measured three top-gated graphene devices on two different chips: samples A and B on the first chip, and sample C on the second chip. The devices were cooled in a closed-cycle optical cryostat with a base temperature of 2.5 K and were irradiated with a 10.6-μm-wavelength CW CO2 laser, providing up to 25 W of linearly polarized light. The laser polarization was controlled with a λ/4 plate. The radiation was delivered using high-power-withstanding molybdenum mirrors, and it was focused on the sample to a spot with a waist of about 50 μm using a ZnSe lens with a focal distance of 50.8 mm. The maximum power used to irradiate the sample was 16 W, yielding a power density P up to 2.6 mW/μm2 after considering energy attenuation in the cryostat window and in the top gate of the graphene devices. Further details of the experimental setup are described in the Supplementary Information.

We performed photoconductive measurements on the Floquet system by measuring the longitudinal current using a lock-in amplifier, with the reference signal to the lock-in provided by a chopper. The source-drain bias was \(6\) mV unless otherwise noted. The chopper modulated the laser beam with a frequency of around 23 Hz and a duty cycle of ~10%. This procedure provided a direct measurement of the photocurrent, denoted \(\Delta {{\rm{I}}}\) and defined as the difference in the source-drain current between the irradiated and equilibrium systems. To explore the doping dependence of the photocurrent, we also extracted the equilibrium Fermi energy, \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\), as a function of the applied gate voltage using the classical Hall effect at different gate voltages, as described in detail in the Supplementary Information.

The experimentally measured photocurrent \(\Delta {{\rm{I}}}\) (see Fig. 1d) exhibits dips as a function of \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\) near doping \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=\pm 1/2\hslash \varOmega\) close to the Floquet gaps for both circular and linear polarization of the laser beam. We note that due to the size of the sample chosen to optimize the coupling to the incident beam27, the circular polarization might be distorted by the proximity to metallic electrodes28 (see the Supplementary Information for details). Nonetheless, the photocurrent dips are robust to changes in polarization and are sensitive only to the electronic photoexcitation rate set by the laser power density and frequency. Importantly, the broadness of the dips, significantly exceeding the width of the Floquet gaps in the graphene density of states (see Fig. 1d), cannot be explained with single-particle Floquet physics and instead indicates strong non-equilibrium electronic population effects.

Theory of Floquet Steady States

Under CW illumination, the electronic population forms a non-equilibrium steady state distribution predominantly stabilized by electron-phonon scattering processes (see Fig. 2a). To understand the photo-assisted population dynamics, we focus on the low-energy band dispersion \({{{\rm{\varepsilon }}}}_{{{\bf{k}}}{{\rm{\alpha }}}}\) of graphene, which exhibits two Dirac cones with Fermi velocity \({{{\rm{v}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\) corresponding to the graphene \(K\) and \(K'\) valleys (see Fig. 2a). Here, \({{\bf{k}}}\) denotes the crystal momentum, and \(\alpha\) enumerates the energy bands. In our theoretical analysis, we focus on circular laser polarization for concreteness. We expect the longitudinal photocurrent to be qualitatively the same for linear polarization parallel to the current. The primary effect of a circularly polarized laser drive is the opening of dynamical gaps at the resonance energies \(\pm {{\hslash }}\varOmega /2\) with a size \(\varDelta\)1,3,29. An additional Haldane gap opens at the Dirac point1, but the gap is too small to be resolved for the power densities used in the experiment, and is therefore not shown in Fig. 2a. The dominant photoexcitation process corresponds to an excitation of the electron to a virtual state (arrow 1) through photon absorption followed by the phonon-emission process relaxing the electron to the conduction band (arrow 2). The electronic population excited by this process is subsequently spread across a small window of energies assisted by the emission of low-energy acoustic phonons (arrow 3) and can be subsequently relaxed through additional acoustic phonon emission processes (arrow 4) back into the valence band. Ultimately, in the steady state, the excited electronic occupation in the conduction band is set by the balance between phonon-assisted photo-excitations (arrows 1-3) and phonon-assisted cooling processes (arrow 4). In Fig. 2a and throughout our theoretical calculations, we include two phonon branches: a slow surface acoustic phonon branch with Rayleigh wave speed 1.3 km/s (arrows 2 and 3 in Fig. 2a) and a faster graphene acoustic phonon branch with speed 11 km/s (arrow 4 in Figure 2a)30. The surface acoustic phonon speed used in our simulations captures the order of magnitude of the Rayleigh wave speed of the SiC31. To find the steady state electronic population \({{{\rm{F}}}}_{{{\rm{k}}}{{\rm{\alpha }}}}\), we solved numerically the full Floquet-Boltzmann equation, which includes all the microscopic electron-phonon scatterings between Floquet-Bloch states in the laser-driven graphene (see Supplementary Information for details)32,33,34,35. The resulting steady state occupations at various electronic dopings are plotted in Fig. 2b–e, and the photocurrent is calculated from the steady state occupations using linear response theory in the weak source-drain bias regime. In our theory, we also account for charge puddles and a small, intensity-dependent lattice temperature difference between the driven and undriven systems. We estimate the conductivity in the presence of charge puddles using a phenomenological formula detailed in the Supplementary Information.

a Key scattering processes between the graphene K and K’ valleys facilitated by photons (arrow 1), surface acoustic phonons (arrows 2,3), and graphene acoustic phonons (arrow 4) that contribute to the steady state. b Steady state distribution (black solid curve) for \(P=\,\)1.9 mW/μm2 and equilibrium distribution (blue dashed curve) of electrons at doping \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=0\), where the longitudinal photoconductivity is enhanced relative to equilibrium. Here, \(\varepsilon\) denotes the quasienergy and \({{{\rm{F}}}}_{{{\bf{k}}}\alpha }\) denotes the electronic occupation. c Steady state distribution (black solid curve) of electrons at doping \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=0.35\,\hslash \varOmega\) and \(P=\) 0.8 mW/µm2, where the photoconductivity is suppressed relative to an equilibrium distribution expectation (blue dashed curve). d Same as (c) but for a larger power density \({P}=\,\)1.9 mW/µm2, where the steady state distribution exhibits additional electron density above the Floquet gap. e Steady state distribution (black solid curve) of electrons for \(P=\,\)1.9 mW/µm2 at doping \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=0.75\,\hslash \varOmega\), where the photoconductivity is approximately identical to that of an equilibrium distribution (blue dashed curve), with a slightly raised effective temperature due to multi-photon heating processes. The horizontal dotted lines in (b–e) mark\(\,\varepsilon\) values corresponding to \(\pm 1/2\hslash \varOmega\).

Remarkably, the steady state distributions denoted by black curves in Fig. 2b–e exhibit multiple step-like features associated with large \(|\partial {{{\rm{F}}}}_{{{\bf{k}}}{{\rm{\alpha }}}}/\partial {{{\rm{\varepsilon }}}}_{{{\bf{k}}}{{\rm{\alpha }}}}|\), resembling effective Fermi surfaces, which significantly affect transport. The electron-like effective Fermi surfaces (\(\partial {{{\rm{F}}}}_{{{\bf{k}}}{{\rm{\alpha }}}}/\partial {{{\rm{\varepsilon }}}}_{{{\bf{k}}}{{\rm{\alpha }}}} \, < \, 0\)) contribute to a longitudinal current parallel to the direction of an applied electric field, while hole-like effective Fermi surfaces (\(\partial {{{\rm{F}}}}_{{{\bf{k}}}{{\rm{\alpha }}}}/\partial {{{\rm{\varepsilon }}}}_{{{\bf{k}}}{{\rm{\alpha }}}}\, > \, 0\)) suppress the overall photocurrent by contributing current antiparallel to the applied field. This is in strict contrast to an equilibrium distribution, where a single Fermi surface appears in the electronic distribution (see blue dashed curves in Fig. 2b–e), and only electrons near the Fermi surface contribute to the longitudinal transport. The Fermi surfaces in the distribution predominantly arise from the scattering processes 1-4 sketched in Fig. 2a. Most notable is the non-equilibrium distribution for an electron-doped system \({0 \, < \, {{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}} < \hslash \varOmega /2\) (see Fig. 2c, d), where the equilibrium Fermi surface located at finite density of states (see blue dashed curve) is separated into three electron-like Fermi surfaces (see black solid curve) which are located near the dips of the density of states and therefore contribute very few electronic carriers. In particular, two electron-like Fermi surfaces are centered at the Floquet gaps, where electronic group velocities and density of states are reduced, and another is positioned at zero energy, where the density of states vanishes. The reduced concentration of electronic carriers gives rise to a suppressed conductivity in the driven system. This phenomenon persists for both weak and strong driving amplitudes, as shown in Fig. 2c and d, respectively. For doping above resonance \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}} \, > \, \hslash \varOmega /2\), processes 1–4 are Pauli-blocked, giving rise to an equilibrium-like distribution (see Fig. 2e).

Optically-controlled photoresponse

Having understood the interplay of the Floquet bands, steady state occupation, and photocurrent \(\Delta {{\rm{I}}}\), we now compare the theoretically calculated and experimentally measured value of \(\Delta {{\rm{I}}}\) and discuss the tunability of the photoresponse by the laser power. In Fig. 3a, we focus on the experimentally measured photocurrent dip at negative \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\) and plot the photocurrent for various laser power densities. In Fig. 3b, we show the theoretically calculated photocurrent for the same power densities. Let us discuss a few salient features captured by the theoretical model. A key feature is the broad width of the photocurrent dip, which we estimate by fitting the photocurrent to a Gaussian-like function detailed in the Methods section. The amplitude of the Gaussian \({a}_{0}\) quantifies the depth of the photocurrent dip, while the full width at half maximum (FWHM) quantifies its width. Notably, our theoretical prediction of the decrease in \({a}_{0}\) with the power density P, agrees with the experimental observation (see Fig. 3c), indicating a power dependence of the steady state distribution. The reduction of \({a}_{0}\) with \(P\) arises due to the increase of the photoexcited carrier density above the Floquet gap, which scales as \(\sim \!{P}^{1/2}\), effectively increasing the photocurrent (cf. the shift of the effective Fermi surface near \(\hslash \varOmega /2\) in Fig. 2c and d)29. The FWHM of the photocurrent dip observed in the experiment and predicted by the theory are both broader than the size of the Floquet gap, see Fig. 3d, indicating a Floquet-induced electronic population inversion in the steady state. We note that \(\Delta {{\rm{I}}} \, > \, 0\) for \(0 \, < \, {{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}} \, < \, {{\hslash }}\varOmega /2\) due to charge puddle and lattice heating effects (see the Supplementary Information for more details). Finally, we note that the horizontal offset in the theoretically calculated photocurrent shown in Fig. 3b relative to the experimental data in Fig. 3a may arise from changes in the total electronic carrier density in the sample during laser illumination, which were not accounted for in the experimental assignment of the chemical potential.

a Photo-induced change of source-drain current (\(\Delta {{\rm{I}}}\)) as a function of \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\) under irradiation at various peak power densities, as measured on sample C at a constant source-drain voltage of 6 mV and a cryostat temperature of 3.2 K. The photon energy is \(\hslash \varOmega=117\,{{\rm{meV}}}\). The laser beam is circularly polarized. The circles represent data points and the solid lines are the fitted curve by a Gaussian-like function described in the Methods. The dotted line marks the \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\) value corresponding to \(-{{\hslash }}\varOmega /2\), with the related uncertainty indicated by the gray stripes. b Theoretically predicted \(\varDelta I\) as calculated from the Floquet Boltzmann equation. The dotted line marks the \({E}_{F}\) value corresponding to \(-\hslash \varOmega /2\). c Depth \({a}_{0}\) of the photocurrent dip and associated error, as calculated from a Gaussian-like fit (see details in the Methods section). For both the theoretical and experimental data, \({a}_{0}\) decreases with the power density P for large P due to enhanced heating processes in the Floquet steady state. d Experimental and theoretical FWHM of the photocurrent dip and the Floquet gap size (red dotted line), \(\varDelta\), as a function of the power density. The FWHM exceeds \(\varDelta\), indicating the emergence of photoexcited electrons in the non-equilibrium Floquet steady state. The detailed error analysis of FWHM is described in the Supplementary Information. The uncertainty in the laser power density due to power fluctuation in (c) and (d) are estimated by the change in the laser power before and after each transport measurement.

To further verify that the transport signatures observed in the experiment arise from photo-induced dynamics, we explore the experimentally measured photo-response for out-of-focus lasers, which reduce the irradiation power density by roughly a factor of three. Figure 4a demonstrates that the visibility of the photocurrent dip is significantly suppressed as the power density is reduced. This behavior, reproduced in theory (see Fig. 4b), reflects the suppressed probability of drive-induced photoexcitation processes under weak laser irradiation.

a Longitudinal photocurrent as a function of \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\) at a fixed source-drain voltage of 6 mV, with laser spot in focus and defocused. For all three curves, the laser power is ~3.6 W, corresponding to a peak power density of 0.6 mW/μm2 at focus. Under defocused irradiation, with the laser spot slightly moved to the side, the power density drops by ~3 times (gray curves). Circular polarization of 10.6 μm wavelength laser radiation. The cryostat temperature stabilized at ~3.4 K. b Theoretically calculated photocurrent for weak drives, exhibiting shallower dips near resonance as a function of decreasing driving power, in agreement with (a). c Temperature dependence of the longitudinal photocurrent as a function of \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\). The photocurrent decreases, and the dips at \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}=\,\pm \hslash \varOmega /2\) disappear at high temperatures. The laser beam is circularly polarized. d Theoretically calculated photocurrent for laser power density 1.4 mW/μm2, the photocurrent dip becomes less visible at higher temperatures. The dotted lines in (a–d) mark the \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\) value corresponding to \(\pm {{\hslash }}\varOmega /2\), where the related uncertainty is indicated by the gray stripes in (a) and (c).

Next, we explore the lattice temperature dependence of the electronic steady state and conductivity. Figure 4c and d, respectively, show the measured and the theoretically predicted \(\Delta {{\rm{I}}}\) as a function of \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}}\), for several values of the lattice temperature. At higher temperatures, the distribution of the photoexcited electrons spreads over larger energy support, relaxing the sharp energy-momentum bottlenecks in the steady state distribution (see processes 1-4 in Fig. 2a). As a result, the dips in \(\Delta {{\rm{I}}}\) become less pronounced, virtually disappearing around 20 K. The discrepancy of the temperature dependence around charge neutrality between the experimental and theoretical plots is attributed to the finite-temperature physics of the charge puddles, which could modify the relaxation time of electrons at different temperatures under weak source-drain bias36, which is not captured in the theory. The strong lattice temperature dependence of both the theoretically calculated and experimentally observed photocurrent, however, highlights the role of low phonon temperatures in stabilizing low-temperature electronic phenomena of Floquet effects in our system.

Discussion

The photoconductivity dip discussed above has been reproduced for other samples, which we present in the Supplementary Information. Different samples with different charge inhomogeneities showed similar widths of the photocurrent dip. This observation is consistent with the emergence of a Floquet steady state, which is predicted to be weakly sensitive to disorder. The positions of the dips in the electron and hole regions of the gate dependence are also slightly asymmetric, similar to particle-hole asymmetric results reported in McIver et al.23.

So far, we have not discussed the transverse photoconductivity of the system. Our transverse voltage measurements displayed a laser helicity-dependent component on the \(\mu{{\rm{V}}}\) scale, which amounts to a Hall conductivity of the order of \({{{\rm{\sigma }}}}_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{Hall}}}}\sim {10}^{-3}{e}^{2}/h\), see Supplementary Fig. 11. This range of values undershoots the prediction of \({{{\rm{\sigma }}}}_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{Hall}}}}\sim {e}^{2}/h\), from our theoretical model, which is mainly designed as a simple model for the longitudinal component of the photocurrent. We believe that a key reason for this discrepancy is the distortion of the circular polarization by the metallic contacts, leading to regions of the sample with nearly linear polarization28 (see Supplementary Information for details). In these regions, the Berry curvature can have large off-diagonal elements, reducing the photoresponse. Additionally, our theoretical calculation of the Hall voltage does not account for electron-electron interactions and charge puddles. Electron-electron scattering could suppress the Hall conductivity by raising the effective temperature of the steady-state electron-like Fermi surfaces (see Fig. 2b–e) near the resonant Floquet gaps33,35. Charge puddles could further suppress the Hall voltage by producing regions in the sample with low conductivity, which exhibit weak longitudinal source drain current and heavily suppressed local Hall voltage. More details of the transverse photoresponse measurements are provided in the Supplementary Information.

In summary, we have explored the transport properties of graphene driven by a CW mid-infrared laser. In such metallic systems, the Floquet dressing of single-particle bands by resonant periodic drives is intertwined with many-body effects, such as electron scattering and population dynamics. Notably, we demonstrate that the interplay between these processes at intermediate driving intensities and cryogenic temperatures facilitates the formation of low-entropy electronic steady states. These steady states emerge from a cascade of photo-assisted electron-phonon scattering events that effectively cool the photoexcited electrons to low entropy states.

Our findings suggest that, in graphene on SiC, these processes are dominated by the emission of surface acoustic phonons at the graphene-SiC interface, along with acoustic phonons in the graphene itself. Furthermore, the formation of these steady states is crucially dependent on the underlying single-particle Floquet physics, such as the presence of Floquet gaps in the single-particle spectrum and scattering into replica Floquet bands. We interpret the observed pronounced dip in longitudinal conductivity in our samples as evidence of Floquet steady states. The characteristics of this dip—its position, depth, and width as functions of doping—align closely with predictions from Floquet many-body theory. Our results indicate a promising approach to perform Floquet engineering in metallic systems for sustained operation, potentially leading to the creation of Floquet steady-state phases, such as drive-induced symmetry broken phases37, laser-induced flat bands35,38,39, and optically-controlled topological transport34,35.

Methods

Experiment

The CW source was a 10.6 μm-wavelength, air-cooled Synrad J48-2 CO2 laser, providing up to 25 W of linearly polarized light, modulated with a chopper (Scitec Instruments 300CD) with 27 Hz modulation frequency. The circular polarization of the laser radiation was controlled by a custom-made zero-order λ/4 plate, provided by Optogama UAB. For the delivery of the optical beam, we used molybdenum mid-IR high power mirrors.

The samples were cooled down to 2.5 K with a closed-cycle cryostat Oxford Instruments Optistat AC-V14. For optical access to our samples, we used a 2-mm thick ZnSe window. The beam delivery was done using an Edmund Optics cage focusing system mounted on a custom-made mechanical attachment to the cryostat. For beam focusing, we used a 50.8-mm focal distance, 1-inch diameter, ZnSe lens. Focusing and alignment of the mid-IR beam was controlled by a system of micrometers40. The estimation of the beam diameter at the lens focus is based on a Gaussian beam with our experimental parameters (18-19 mm laser beam waist before lens and 50.8 mm lens focal distance), and it yields ~35-38 μm. Experimentally, we were able to achieve focusing down to a 50 μm spot. This was confirmed during the fine alignment of the laser beam: the magnitude of \(\Delta {{\rm{I}}}\) was changing from the noise level to a maximum signal and then back to the noise level (about 10-12-times drop of signal magnitude) within 4-5 readout thimble divisions of in-plane alignment micrometers (e.g., within 40-50 μm distance). The maximum applied laser power in our experiments was 16 W, corresponding to a peak power density ~ 8 mW/μm2 for ~50 μm-diameter beam spot. Taking into account the transmission coefficients of the cryostat window and the gate electrode, we estimate the applied laser intensity as ~2.6 mW/μm2.

The measurements of photoinduced currents and voltages were performed using a home-made bias box, an HP 6177 C DC current/voltage source (for generation of gate voltages), a National Instruments BNC-2110 junction box, an Ametek 5110 lock-in amplifier, a DL Instruments 1211 current preamplifier, and a custom-made differential voltage preamplifier. The data collection system was controlled using a customized LabVIEW-based program.

The calibration of gate efficiencies of our samples (calibration of gate voltage in units of electron Fermi energy) was performed using a 9 Tesla Quantum Design Physical Property Measurement System at the NHMFL in Tallahassee, FL. The details about gate efficiency calibration are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Device fabrication

For the device fabrication we adapted the process developed by Yang et al.41. to electron-beam lithography (EBL)42 with additional lithography steps to deposit and pattern a top gate. The details of the device fabrication are provided in the Supplementary Information. The epitaxial graphene on SiC was purchased from Graphene Waves.

Fitting

We estimate the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the photocurrent dip by fitting the photocurrent to the function \(\Delta {{{\rm{I}}}}_{{{\rm{fit}}}}={a}_{0}\exp [-{ ({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{g}}}}-B )}^{2}/2{\sigma }^{2} ]+C{{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{g}}}}+D\), where \({a}_{0},B,\sigma,C\), and \(D\) are fitting parameters, and \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{g}}}}\) is the gate voltage. We extract the full width half maximum using the relation \({{\rm{FWHM}}}={{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}} (B+\sqrt{2 \, {\ln} \, 2}\sigma )-{{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}} (B-\sqrt{2\,{\ln}\, 2}\sigma )\), where \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}} ({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{g}}}} )=\hslash {{{\rm{\nu }}}}_{{{\rm{F}}}} \sqrt{\pi k ({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{g}}}}-{{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{d}}}} )}\). Here, \(k\) is estimated from Hall measurements, and \({{{\rm{V}}}}_{{{\rm{d}}}}\) is estimated to be the gate voltage at which \({{{\rm{\sigma }}}}_{{{\rm{xx}}}}\) is minimized (see the Supplementary Information).

Data availability

Relevant data supporting the key findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. All raw data generated during the current study are available from corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

Computer code generated during the current study is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14847973.

References

Oka, T. & Aoki, H. Photovoltaic Hall effect in graphene. Phys. Rev. B https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.79.169901 (2009).

Lindner, N. H., Refael, G. & Galitski, V. Floquet topological insulator in semiconductor quantum wells. Nat. Phys. 7, 490–495 (2011).

Kitagawa, T., Oka, T., Brataas, A., Fu, L. & Demler, E. Transport properties of nonequilibrium systems under the application of light: Photoinduced quantum Hall insulators without Landau levels. Phys. Rev. B https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.84.235108 (2011).

Oka, T. & Kitamura, S. Floquet engineering of quantum materials. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 10, 387–408 (2019).

Rudner, M. S. & Lindner, N. H. Band structure engineering and non-equilibrium dynamics in Floquet topological insulators. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 229–244 (2020).

Perez-Piskunow, P. M., Usaj, G., Balseiro, C. A. & Foa Torres, L. E. F. Floquet chiral edge states in graphene. Phys. Rev. B https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.89.121401 (2014).

Jotzu, G. et al. Experimental realization of the topological Haldane model with ultracold fermions. Nature 515, 237 (2014).

Seetharam, K., Titum, P., Kolodrubetz, M. & Refael, G. Absence of thermalization in finite isolated interacting Floquet systems. Phys. Rev. B https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.97.014311 (2018).

de la Torre, A. et al. Colloquium: Nonthermal pathways to ultrafast control in quantum materials. Rev. Modern Phys. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.93.041002 (2021).

Kundu, A., Fertig, H. A. & Seradjeh, B. Effective theory of Floquet topological transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 236803 (2014).

Foa Torres, L. E. F., Perez-Piskunow, P. M., Balseiro, C. A. & Usaj, G. Multiterminal conductance of a Floquet topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 266801 (2014).

Dehghani, H., Oka, T. & Mitra, A. Out-of-equilibrium electrons and the Hall conductance of a Floquet topological insulator. Phys. Rev. B https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.91.155422 (2015).

Rudner, M. S. & Song, J. C. W. Self-induced Berry flux and spontaneous non-equilibrium magnetism. Nat. Phys. 15, 1017–1021 (2019).

Bajpai, U., Ku, M. J. H. & Nikolic, B. K. Robustness of quantized transport through edge states of finite length: Imaging current density in Floquet topological versus quantum spin and anomalous Hall insulators. Phys. Rev. Res. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevResearch.2.033438 (2020).

Sato, S. A. et al. Microscopic theory for the light-induced anomalous Hall effect in graphene. Phys. Rev. B https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.99.214302 (2019).

Wang, Y. H., Steinberg, H., Jarillo-Herrero, P. & Gedik, N. Observation of Floquet-Bloch States on the Surface of a Topological Insulator. Science 342, 453–457 (2013).

Zhou, S. H. et al. Pseudospin-selective Floquet band engineering in black phosphorus. Nature 614, 75–80 (2023).

Mahmood, F. et al. Selective scattering between Floquet-Bloch and Volkov states in a topological insulator. Nat. Phys. 12, 306–310 (2016).

Merboldt, M. et al. Observation of Floquet states in graphene. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.12791 (2024).

Shan, J. et al. Giant modulation of optical nonlinearity by Floquet engineering. NATURE 600, 235–239 (2021).

Kobayashi, Y. et al. Floquet engineering of strongly driven excitons in monolayer tungsten disulfide. Nat. Phys. 19, 171–176 (2023).

Sie, E. J. et al. Valley-selective optical Stark effect in monolayer WS2. Nat. Mater. 14, 290–294 (2015).

McIver, J. W. et al. Light-induced anomalous Hall effect in graphene. Nat. Phys. 16, 38–41 (2020).

Ito, S. et al. Build-up and dephasing of Floquet-Bloch bands on subcycle timescales. NATURE 616, 696–701 (2023).

Park, S. et al. Steady Floquet-Andreev states in graphene Josephson junctions. Nature 603, 421–426 (2022).

Haxell, D. Z. et al. Microwave-induced conductance replicas in hybrid Josephson junctions without Floquet-Andreev states. Nat. Commun. 14, 6798 (2023).

Kominami, M., Pozar, D. & Schaubert, D. Dipole and slot elements and arrays on semi-infinite substrates. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 33, 600–607 (1985).

Biagioni, P., Huang, J., Duò, L., Finazzi, M. & Hecht, B. Cross resonant optical antenna. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 256801 (2009).

Calvo, H. L., Pastawski, H. M., Roche, S. & Foa Torres, L. E. F. Tuning laser-induced band gaps in graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3597412 (2011).

Cong, X. et al. Probing the acoustic phonon dispersion and sound velocity of graphene by Raman spectroscopy. CARBON 149, 19–24 (2019).

Nordhagen, E., Sveinsson, H. & Malthe-Sorenssen, A. Diffusion-Driven Frictional Aging in Silicon Carbide. Tribol. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11249-023-01762-z (2023).

Seetharam, K. I., Bardyn, C. E., Lindner, N. H., Rudner, M. S. & Refael, G. Controlled population of Floquet-Bloch states via coupling to bose and Fermi baths. Phys. Rev. X https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.5.041050 (2015).

Seetharam, K., Bardyn, C., Lindner, N., Rudner, M. & Refael, G. Steady states of interacting Floquet insulators. Phys. Rev. B https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.99.014307 (2019).

Esin, I., Rudner, M., Refael, G. & Lindner, N. Quantized transport and steady states of Floquet topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.97.245401 (2018).

Yang, C., Esin, I., Lewandowski, C. & Refael, G. Optical control of slow topological electrons in Moire systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 026901 (2023).

Li, Q., Hwang, E. & Das Sarma, S. Disorder-induced temperature-dependent transport in graphene: Puddles, impurities, activation, and diffusion. Phys. Rev. B https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.84.115442 (2011).

Esin, I., Gupta, G., Berg, E., Rudner, M. & Lindner, N. Electronic Floquet gyro-liquid crystal. Nat. Commun. 12, 5299 (2021).

Katz, O., Refael, G. & Lindner, N. Optically induced flat bands in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.102.155123 (2020).

Li, Y., Fertig, H. & Seradjeh, B. Floquet-engineered topological flat bands in irradiated twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Res. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevResearch.2.043275 (2020).

Kalugin, N. G. et al. Photoelectric polarization-sensitive broadband photoresponse from interface junction states in graphene. 2d Mater. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1583/4/1/015002 (2017).

Yang, Y. F. et al. Low carrier density epitaxial graphene devices on SiC. Small 11, 90–95 (2015).

El Fatimy, A. et al. Epitaxial graphene quantum dots for high-performance terahertz bolometers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 335–338 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from NSF (projects DMR CMP #2104755, DMR CMP #2104770, and OSI #2329006), ANID FondeCyT (Chile) through grant number 1211038, and the Institute for Quantum Information and Matter, an NSF Physics Frontiers Center (PHY-2317110). C.Y. gratefully acknowledges support from the DOE NNSA Stewardship Science Graduate Fellowship program, which is provided under cooperative Agreement No. DE-NA0003960. G.R. and I.E. are grateful to the AFOSR MURI program, under agreement number FA9550-22-1-0339, as well as the Simons Foundation. Part of this work was done at the Aspen Center for Physics, which is supported by the NSF grant PHY-1607611. F.N. gratefully acknowledges support from the Carlsberg Foundation, grant CF22-0727. C.L. was supported by start-up funds from Florida State University and the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. The National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (NHMFL) is supported by the National Science Foundation through NSF/DMR-1644779, NSF/DMR-2128556 and the State of Florida. L. E. F. F. T. acknowledges partial support from the EU Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie-Sklodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 873028 (HYDROTRONICS Project), and of The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics and the Simons Foundation. The authors thank Dr. Michael Jackson, Dr. Yanfei Yang, Eli Adler, DaVonne Henry, Amjad Alqahtani, and Thy Le for helpful discussions, Taylor Terrones, Michael Chavez, and Leon Der for help with our experimental setup, and Dr. David Graf for help with experiments at NHMFL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.G.K., L.E.F.F.T., and P.B. planned the project. Device fabrication was performed by Y.L. Optical systems were designed by N.G.K., A.V.S., G.G., J.H., P.B., Y.L., and were assembled and tested by N.G.K, A.V.S., G.G., and J.H. with the help of machine shops of NMT, GU, and NHMFL. Measurements were made by Y.L., P.B., A.V.S., and N.G.K. L.E.F.F.T. carried out theoretical calculations of the Floquet density of states. C.Y. carried out the steady-state Floquet simulations ]\sed by G.R., F.N., C.L., and I.E. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and the manuscript preparation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Yang, C., Gaertner, G. et al. Signatures of Floquet electronic steady states in graphene under continuous-wave mid-infrared irradiation. Nat Commun 16, 2057 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57335-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57335-2